Abstract

Neurodegenerative disorders and type 2 diabetes are global epidemics compromising the quality of life of millions worldwide, with profound social and economic implications. Despite the significant differences in pathology – much of which are poorly understood – these diseases are commonly characterized by the presence of cross-β amyloid fibrils as well as the loss of neuronal or pancreatic β-cells. In this review, we document research progress on the molecular and mesoscopic self-assembly of amyloid-beta, alpha synuclein, human islet amyloid polypeptide and prions, the peptides and proteins associated with Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, type 2 diabetes and prions diseases. In addition, we discuss the toxicities of these amyloid proteins based on their self-assembly as well as their interactions with membranes, metal ions, small molecules and engineered nanoparticles. Through this presentation we show the remarkable similarities and differences in the structural transitions of the amyloid proteins through primary and secondary nucleation, the common evolution from disordered monomers to alpha-helices and then to β-sheets when the proteins encounter the cell membrane, and, the consensus (with a few exceptions) that off-pathway oligomers, rather than amyloid fibrils, are the toxic species regardless of the pathogenic protein sequence or physicochemical properties. In addition, we highlight the crucial role of molecular self-assembly in eliciting the biological and pathological consequences of the amyloid proteins within the context of their cellular environments and their spreading between cells and organs. Exploiting such structure-function-toxicity relationship may prove pivotal for the detection and mitigation of amyloid diseases.

Keywords: amyloid, oligomer, self-assembly, neurodegenerative disorders, Aβ, IAPP, α-synuclein, prion, theranostics

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Molecular self-assembly is an ubiquitous phenomenon across all living systems: from the polymerization of tubulins and actins into microtubules and actin filaments, to the organization of lipids, transmembrane/peripheral proteins and ion channels into cell membranes, to the assembly of DNA and histones into chromatin fibers and solenoids, and to the aggregation of peptides and proteins intra- or extracellularly evolving from functional monomers to toxic oligomers, amyloid fibrils and plaques. Fundamental to these processes are interactions between the molecular constituents of the assemblies, as well as interactions between the molecular constituents and their associated chaperones, ligands, ions, molecular complexes and organizations, driven by kinetic and thermodynamic processes to elicit desirable biological functions or malfunctions and diseases.

In this review, we attempt to draw parallels from the atomic and mesoscopic structures of five major classes of amyloid proteins in self-assembly, namely, amyloid-beta (Aβ), tau, alpha-synuclein (αS), prions, and human islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP), as well as the biological and pathological endpoints these assemblies elicit in host systems (Fig. 1). The amyloid aggregation of these peptides has been implicated in Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, prion diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus, or generically referred to as neurodegenerative disorders and T2D that debilitate hundreds of millions of people worldwide. In vitro, such peptides/proteins fibrillate on the timescales of tens of minutes for IAPP to days for Aβ and αS, characterized by a sigmoidal kinetic curve consisting of a lag phase, an elongation phase, and a saturation phase.1 The lag phase is where nucleation is initiated through protein misfolding and where intrinsic seeds and/or oligomers are formed, the elongation phase corresponds to the addition of monomers to growing protofilaments, while the saturation phase is where protofilaments associate through self-assembly to render amyloid fibrils. In addition to primary nucleation, secondary nucleation through the combination of both monomeric and aggregated species is also feasible.2, 3 It has been suggested that the amyloid state is perhaps available to any polypeptide chain4–9 and represents the energetically most favorable state even compared to native proteins.1 In vivo, however, the development of amyloids and plaques in the brain or pancreatic islets often takes decades, or ~10,000 times longer. Such drastic differences in fibrillization may originate from the crowded hierarchical cellular environments, where amyloid proteins are synthesized and then translocate and spread through inter- and intra-molecular assembly, chaperoned by proteins (e.g. insulin for IAPP) or modulated by pH and ionic strength. Accordingly, while the main purpose of this review is to highlight the structure-function-toxicity triangle of a selected few amyloid proteins, another goal of this presentation is to draw the readers’ attention from focusing exclusively on amyloid proteins to the environments of the culprits at large, which undoubtedly also contribute to the pathologies of the amyloid diseases. Such perspective may prove beneficial to the development of mitigation strategies and theranostics against amyloidogenesis that has become increasingly perilous to modern society.

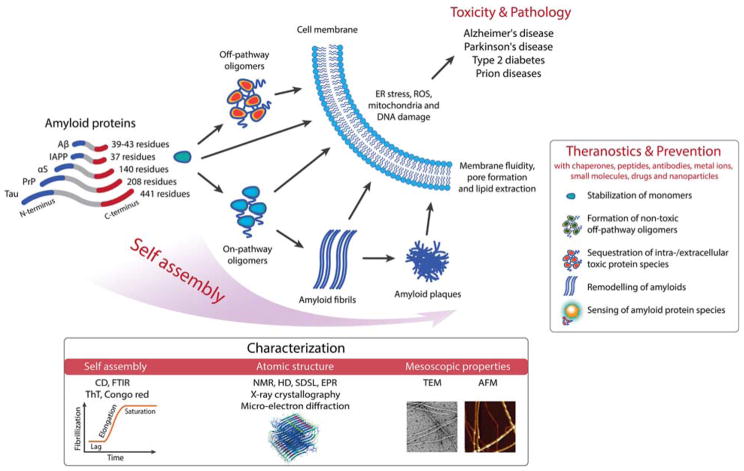

Figure 1.

Scope of the present review, highlighting protein self-assembly, its biological and pathological implications, theranostics and prevention. Aβ: amyloid-beta; IAPP: islet amyloid polypeptide; αS: alpha-synuclein; PrP: prion protein; CD: circular dichroism spectroscopy; FTIR: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; ThT: thioflavin T assay; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance; HD: hydrogen-deuterium exchange; SDSL: site directed spin labelling; EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; AFM: atomic force microscopy. ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

In terms of content, this review consists of 6 sections: section 1 offers an introduction to protein self-assembly and amyloid diseases; sections 2–5 review the structure, function and toxicity characteristics of Aβ, tau, IAPP, αS and prions, loosely following their increasing numbers of amino acids (residues); section 6 provides a summary. Aβ and tau, despite their great contrast in chain length, both contribute to the AD pathology and hence are presented together. Although Aβ is slightly longer than IAPP in chain length, Aβ is the most studied of all amyloid proteins10 and is therefore discussed in the early section of this review.

2. Aβ, tau and Alzheimer’s disease

The hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the accumulation of toxic aggregates that impair synaptic function and induce cognitive decline. The first reported occurrence of cognitive disorder linked to AD was in 1907 by Alzheimer, who observed two types of abnormality in a brain autopsy that he attributed to be the cause of an unusual type of dementia.11 The discovery of neuritic plaques (or miliary foci) and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) was immediately linked to the dystrophic neuronal process, and later Aβ fibrils12, 13 and hyperphosphorylated tau tangles14 were isolated and characterized (and proposed to cause dementia). Characterizations of the monomeric forms of the molecules found in these neurotoxic deposits have led to greater understanding of the pathways leading to AD, with a particular focus on the structure-function relationship between aggregates and neurotoxicity. However, almost all drugs tested thus far in clinical trials have failed or shown limited impact on AD.

Tau is a neuronal protein associated with microtubules and may regulate neuron morphology. There are six main tau isoforms in the brain and central nervous system (CNS). The longest human isoform has 441 residues with a high proportion of phosphorylable residues (serine and threonine) and a low proportion of hydrophobic amino acids. Tau protein in solution is considered an intrinsically disorder protein (IDP) and behaves as a random coil,15 although modifications by phosphorylation may lead to an increase in α-helix or β-sheet regions. Aggregation of totally or partially disordered proteins is associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, including AD.16 However, the molecular mechanism of aggregation and the structure of the aggregated form remain controversial. Tau is mainly an axonal protein but in AD and other tauopathies it is also present at dendritic spines and may play a toxic role. The tau hypothesis of AD considers that excessive phosphorylation of tau protein can result in the self-assembly of tangles of paired helical filaments (PHFs) and straight filaments which are involved in the pathogenesis of AD and other tauopathies. These neurofibrillary tangles are insoluble structures that impair axonal transport and lead to cell death. The molecular structures of PHFs and tau protein are not well defined.

NMR data17 have revealed that 343 of the 441 amino acids in tau are disordered with six segments of the sequence displaying propensity to form β-strands, three segments showing poly-Pro helices and two segments with a transient α-helix structure. In particular, aggregation of tau is believed to be strongly associated with two short residue sequences:18–21 the first in the third repeat fragment (R3, i.e. VQIVYKPVDLSKVTSKCGSLGNIHHK) of the microtubule binding domain of tau, VQIVYK, or the mutant VQIINK, in the second repeat fragment. The aggregation of the R3 fragment has been extensively studied in the presence of polyanions, such as heparin, pointing at the formation of fibrillar structures with similar features as those assembled from the pristine tau protein.22 In the absence of heparin, however, the same R3 fragment has been shown to self-assemble into giant amyloid ribbons of remarkable aspect ratios.23

The tau protein is a highly dynamic structure. An NMR study of a peptide derived from tau showed that phosphorylation stabilized the α-helix structure,24 suggesting a possible higher content of α-helices in hyperphosphorylated tau in PHFs. Tau protein can form dimers, oligomers and larger aggregates and fibrils. However, in this review we focus on the Aβ peptide rather than tau aggregates, as greater structural details are available for the former.

2.1 Role of APP and production of Aβ

Aβ peptides are produced by an intrinsic cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) that is an integral membrane protein encoded on chromosome 21 by the APP gene.25 It is accepted that patients with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) overexpress APP and develop AD-like senile plaques in their brain.26, 27 Yet, the physiological function of APP remains uncertain, mostly because APP is part of a gene family with overlapping function (e.g. producing the amyloid precursor-like proteins APLP1 and APLP2) and is subject to various post-expression modifications.28 Still, only APP generates the Aβ fragment. APP modulates critical features in brain development since APP knock-out mice are viable but exhibit reduced body weight and brain mass29 with increased brain levels of copper,30 cholesterol and sphingolipid.31 Interestingly, reintroducing the APP ectodomain, which is produced by cleavage of the membrane-anchored APP, improved cognitive function and synaptic density32, 33 and acted as an apoptosis modulator through caspases activations.34 The intracellular C-terminal domain also has a functional role in sorting APP and, in particular, the highly conserved YENPTY cytoplasmic sequence is prone to interaction with other proteins, such as X11 and Fe65, which are postulated to regulate APP internalization.35

The location and sequence of the proteolytic cleavage of APP are critical to AD. APP is primarily translocated to the cell surface (short residence time) where α-secretase and then γ-secretase produce APPsα, p3 and AICD fragments, which are not amyloidogenic. However, when APP is relocated through endocytosis (rapid turnover due to the YENPTY sequence) into endosomes containing the β-secretase (also called BACE1) and the γ-secretase, then APPsβ, the toxic Aβ peptides and AICD fragments are produced (Fig. 2). BACE1 is an aspartyl protease that has optimum efficiency at pH 4.5.36 Interestingly, acid pH can promote greater aggregation rate of Aβ peptides37 due to the protonation state of the three histidines (His6, His13 and His14), and also attenuate lysosomal degradation of Aβ peptides.38 Furthermore, if APP is relocated to the trans Golgi network instead of the ER, BACE1 can produce N-truncated Aβ peptides which are prone to rapid pyroglutamylation.39 These species have been characterized as highly toxic40 and found in intracellular, extracellular and vascular Aβ deposits in AD brain tissue,41 while unmodified peptides are primarily located in endosomal compartments and are eventually exocytosed into the extracellular space.

Figure 2.

(a) Non-amyloidogenic pathway triggered by the location of APP at the plasma membrane interface; and (b) Amyloidogenic pathway induced through APP endocytosis into endosomal vesicles containing the protease BACE1. Aβ peptides are then prone to aggregation and can be either secreted extracellularly or remain in the intracellular space to target other organelles, such as mitochondria, or be degraded by proteases such as cathepsin B.

It is noteworthy that intracellular pools of Aβ peptides are pointed as the most toxic species causing the death of neurons.42, 43 The physiological function of these Aβ peptides, usually 39–43 residues in length, is unconfirmed. However, during excitatory neuronal activity, an increase in excretion of Aβ peptides is observed44 with the effect of downregulating excitatory synaptic transmission.45 Thus, Aβ peptides are an important modulator of memory, since inhibition of peptide production impairs learning.46 Aβ(1–40) is the most abundant Aβ isoform found in its soluble form in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid and brain interstitial fluid47 but is also a major component in amyloid plaques. Interestingly, the level of the fast-aggregating isoform Aβ(1–42) is a biomarker for detecting amyloid pathologic changes in the brain and cerebral vessels48 and, moreover, the relative Aβ(1–42)/Aβ(1–40) ratio is markedly increased in AD.49 Overall, both the concentration and location of Aβ peptides are critical for brain function, thereby complicating therapeutic strategies against AD.

2.2 Atomic structures of Aβ40 & Aβ42, post-modifications and amyloid fibrils

Aβ peptides vary in length due to the multiple cleavage sites recognized by the secretases, but the most abundant species are Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42), whose sequences are shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, Aβ peptides can be degraded by proteases such as insulin degrading enzymes,50 neprilysin51 and cathepsin B,52 which render the fragments non-amyloidogenic. Aβ peptides can be subject to post-translational modifications including pyroglutamate formation (Glu3, 11 and 22),53 phosphorylation (Ser8 and 26),54 dityrosine formation (Tyr10)55 and oxidation (Met35)56 (see Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Aβ peptide sequence (CINEMA color code), potential post-modification sites and physicochemical properties; and (b) Intramolecular interactions stabilizing the typical hairpin β-sheet structure. Red and orange dashes: molecular contacts. Blue dashes: side-chain packing. Green: hydrophobic residues. Black: salt bridge. Adapted from reference 57. Copyright Nature Publishing Group.

The Aβ peptide primary sequence exhibits two stretches of hydrophobic residues (17–21 and 32 until C-terminus), which are predicted to adopt a β-sheet conformation.57 Two turn regions are also predicted between residues His6 and Ser8, and between Asp23 and Asn27. Finally, the hydrophilic patches between Asp1 and Lys16 and between Glu22 and Lys28 have either β-sheet or α-helical propensity.58, 59

A missing piece in the AD puzzle is the secondary structures of Aβ peptides immediately after cleavage by the γ-secretase. Firstly, β-CTF is likely to remain structured after cleavage by BACE1, at least up to the transmembrane α-helical segment that contains part of Aβ sequence (Ala28 until C-terminus). Secondly, cleavage by the γ-secretase occurs at intra-membrane and Aβ peptides have a demonstrated affinity for lipid membranes. Thus immediate trafficking is unclear: do Aβ peptides remain in, on or away from the membrane interface? Since lipid membranes modulate the aggregation kinetics,60 this step could play a critical role in subsequent trafficking and AD pathology.

Several Aβ peptide structures have been compiled in the past two decades,61 with a consensus that an unstructured to β-sheet transition first occurs followed by a seeded aggregation process to form oligomeric structures that eventually proceeds to mature amyloid fibrils of 70–120 Å in diameter and an indeterminate length according to electron microscopy.62 Determination of the initial structure of Aβ peptides in native conditions is challenging since the rapid self-aggregation rate accompanied by poor solubility prevents the application of high-resolution techniques such as solution NMR. Nevertheless, several structures of the monomeric peptides have been determined in either organic solvents (dimethylsulfoxide, hexafluoroisopropanol, trifluoroethanol), aqueous solution or detergent micelles (sodium dodecyl sulfate or SDS). In general, Aβ peptides adopted helical conformations with unstructured termini and various turn regions in organic solvents,63–65 aqueous buffer66 and in membrane mimetic detergent micelles.67, 68 Interestingly, most structural studies show that physiological pH,69 low salt concentration70 and higher temperature71 could heavily modulate the peptide conformational transition to β-sheet structure and thereby promoting rapid self-aggregation. The α-helical conformation is proposed as a transient on-pathway intermediate during the complex amyloid fibril formation.72 Indeed, the multistep kinetics of amyloid assembly comprise a lag phase, during which little or no fibril material is formed, followed by an exponential growth of β-sheet-rich aggregates that propagate into amyloid fibrils.1 Increasing evidence suggests that the native partly helical intermediates form the early nucleation seeds during the lag phase.73 The intramolecular interactions stabilizing the β-sheet structure are shown in Fig. 3. In both Aβ isoforms, the turn conformation is stabilized by hydrophobic interactions and by a salt bridge between Asp23 and Lys28. Many side chain contacts are observed, in particular between Phe19 and Ile32, Leu34 and Val36, and between pairs Gln15 - Val36 and His13 -Val40.57,74

Phosphorylation of Aβ peptides, however, does not modify their primary unstructured conformation but leads to a 5-fold reduction in the lag phase due to a faster transition to β-sheet structures, more efficient nucleation and a greater number of oligomeric seeds.75 N-truncated and/or pyroglutamate-modified Aβ peptides form β-sheet structures76 with faster aggregation kinetics than the corresponding full-length peptides, which suggests they could be potential seeding species for aggregate formation. More dramatically, the pyroglutamate-modified Aβ peptides also inhibit the full-length peptide fibrillogenesis and lead to a greater content of small oligomeric species77 that have been demonstrated as the most toxic species.

2.3 Aβ aggregation kinetics and amyloid fibril formation

Knowledge of Aβ aggregation kinetics and mechanisms has been acquired mainly through in vitro studies using synthetic peptides. The kinetics of fibril formation depends on several intrinsic and extrinsic factors. The primary sequence of the peptide modulates the propensity to aggregate into mature fibrils. Post-modifications promote faster aggregation kinetics, as does the Aβ(1–42) sequence compared to the shorter Aβ(1–40) peptide. Extrinsic factors, such as interaction with lipid membranes, can have either a slowing or accelerating effect, rendering determination of a generic model nontrivial.

The lag phase is a period of slow self-aggregation and structural change, likely from helical to β-sheet structures, and characterized by a combination of multiple nucleation and elongation phases2,78, 79 leading to a large number of oligomeric species. Primary nucleation is a fast process (milliseconds) producing the first seeds that are elongated further into fibrils by the addition of monomers. The formation of new aggregates is thought to be dominated by a second nucleation phase where existing fibrils are fragmented to expose new seeds either co-aggregating or recruiting monomers. Interestingly, changes in the primary nucleation rate do not affect the elongation phase while secondary nucleation and fragmentation modify the lag and elongation phases.80 The difference in aggregation rate between the amyloid peptide species, however, may be related to their primary nucleation rate. In fact, Aβ(1–40) monomers, in comparison to Aβ(1–42), exhibit a slower nucleation rate inducing (or caused by) a shift towards nucleation on the fibril surface rather than accumulation of small oligomeric species.79 These fibril-catalyzed secondary nucleation and elongation processes could be a critical difference in relation to the trafficking and toxicity of the Aβ peptide variants.81 Notably, measuring the kinetics of aggregation is challenged by the difficulty in sample preparation,81 especially with regard to starting an experiment without any preformed seeds or a controlled amount of seeds.

The elongation phase is due to the addition of oligomers/monomers onto protofibrils (Fig. 4) or association of protofibrils, in competition with fragmentation of the protofibrils. It is often typified by the half time of the aggregation reaction where the monomers and protofibrils are near equimolar. However, intrinsic and extrinsic factors modulate the stability of the oligomeric species and can template seeds thereby shifting the kinetic rate towards primary nucleation with a faster aggregation rate. The stationary phase represents a steady state where the monomer concentration has reached an equilibrium value and the fibrils are the prevalent species. Notably, AFM studies show that fibrils of different amyloid-forming peptides with diverse macroscopic structures/polymorphism (i.e., ribbon-like versus nanotube-like packing) have a similar Young’s modulus; and thus all Aβ peptides are anticipated to exhibit similar mechanical strength.82

Figure 4.

Aβ aggregation pathways from monomer to fibril formation and toxic outcomes.

Intrinsic and extrinsic factors also play a critical role in the modulation of the lag and elongation phases by changing the concentration of free monomer in solution and/or acting as seeding interfaces. The molecular factors influencing the aggregation kinetic of Aβ peptides are various and difficult to assign to a particular microscopic event (primary versus secondary nucleation, fragmentation, etc.), although some properties are more straightforward to correlate, for instance, the effect of pH as electrostatic interactions mediate either attraction or repulsion of the monomers.78

2.4 Mesoscopic structures of Aβ amyloid fibrils

An original molecular model of Aβ(1–40) fibrils83 based on solid-state NMR data shows the first ~10 residues as structurally disordered while residues 12–24 and 30–40 adopt β-strand conformations and form parallel β-sheets through intermolecular hydrogen bonding. A bend at residues 25–29 brings the two β-sheets in contact through sidechain-sidechain interactions. The cross-β motif common to all amyloid fibrils is a double-layered structure, with in-register parallel β-sheets.83 However, several studies have shown that Aβ peptides form polymorphic fibrils that depend on growth conditions and various oligomeric aggregates. Thus it is unlikely that amyloid fibrils formed in vitro resemble those in the brain. Tycko and co-workers84 seeded fibril growth from brain extract and used solid-state NMR and electron microscopy to gain structural details of the Aβ fibrils. Using tissue from two AD patients they found a single Aβ40 fibril structure for each patient emphasizing the critical role of the seeding process. The molecular structure for Aβ40 fibrils from one patient (Fig. 5) revealed differences from in vitro fibrils. The authors proposed that fibrils may spread from a single nucleation site and that structural variations may correlate with variations in AD.

Figure 5.

Aβ40 structural polymorphism depending on experimental conditions. Rendered from PDB 1BA4, 1AML, 2MVX and 2MJ4.

In comparison with Aβ40, Aβ42 is more neurotoxic and their differences in behaviour may be due to intrinsic differences in structure. An atomic resolution structure of a single form of Aβ42 amyloid fibrils has been derived from high field magic angle spinning NMR spectra.85 The structure shows a dimer of Aβ42 molecules, each containing four β-strands in an S-shaped amyloid fold (Fig. 6). The dimer is arranged to form two hydrophobic cores, capped by a salt bridge at the end with a hydrophilic outer surface. The monomer interface within the dimer shows contacts between M35 of one molecule and L17 and Q15 of the second. Intermolecular constraints show that the amyloid fibrils are parallel in-register. Interestingly, Ishii and co-workers obtained a similar S-shape arrangement (Fig. 6) using ultra-fast spinning solid-state NMR techniques.86 Although knowing atomic details of the fibril may be useful for drug design, nevertheless, the oligomer species are generally accepted as the toxic species.87

Figure 6.

Two recent solid-state NMR Aβ42 fibril structures identifying different assemblies by (left) Griffin and co-workers (PDB: 5kk3)85 and (right) Ishii and co-workers (2MXU).86 High similarity is apparent with the β-sheet domain (purple ribbons) and the unstructured strand (gray ribbons) forming an S-shape. The hydrophobic surfaces are based on Kyte-Doolittle scale (red: hydrophobic, white: neutral, blue: hydrophilic).

2.5 Extrinsic factors modulating Aβ structure, aggregation kinetic and toxicity

2.5.1 Aβ-metal interactions

The role of transition metals in AD is highly debated and a recent literature search using meta-analysis and systemic review methodologies identified a widespread misconception that iron and, to a lesser degree, zinc and copper levels are increased in AD brain.88 Metals were primarily thought to be accumulated in AD brain tissue due to positive staining but quantitative analysis failed to confirm a significant increase,89 and more recent studies have confirmed the artefacts in quantitation due to tissue fixation prior to analysis.90 Qualitative ex vivo and in vitro studies have demonstrated that Aβ peptides recruit iron, zinc and copper with high affinity91 and, more dramatically, induce a redox complex with oxidative stress properties92 that may be related to the toxicity of Aβ peptides and which has been widely accepted as a potential toxic mechanism in AD.93 Two binding sites were identified: the Met35 mediating the Fenton reaction through the electron donor sulfide group;94 and the N-terminal region forming a chelating domain95 of Asp1, His6, His13 and His14, which undergoes a major structural rearrangement during the redox cycle of ROS production.96 Interestingly, in vitro experiments have also shown that metal binding noticeably extends the lag time by stabilizing oligomeric and amorphous aggregates,97 which may explain the poor in vivo detection of the peptide amyloids. Aβ-copper complexes have also been shown to promote lipid peroxidation, in particular within the polyunsaturated chains of membrane lipids, which is another potential toxic mechanism due to neuronal membrane disruption.98

2.5.2 Aβ-membrane interactions

The role of lipids in AD was first suggested by Alzheimer when he discovered adipose inclusions and alterations of lipid composition in brain tissue.11 Several classes of lipids have been investigated for their specific interactions with Aβ peptides, such as cholesterol, gangliosides or anionic phospholipids.99 The lipid membrane interface itself is proposed to be a heterogeneous nucleation site, which modulates Aβ peptide folding kinetics and pathways by reducing the seeding mechanism to a two-dimensional system.100, 101 To date, there is a consensus that lipid bilayer plays a role in Aβ aggregation and may be involved in neurotoxicity. Different model membranes influence the structure and size of Aβ fibrils based on the charge and hydrophobicity of the membrane.60, 102 Membrane-attached oligomers of Aβ40 displayed a β-turn, flanked by two β-sheet regions or an anti-parallel beta-hairpin conformation by Raman spectroscopy and solid-state NMR.103 In contrast to the mature, less-toxic Aβ fibrils, the membrane-attached oligomer appeared to form a β-barrel or ‘porin’-like structure (also refer to Fig. 15b in section 4 for αS), which may account for a mechanism for Aβ toxicity.

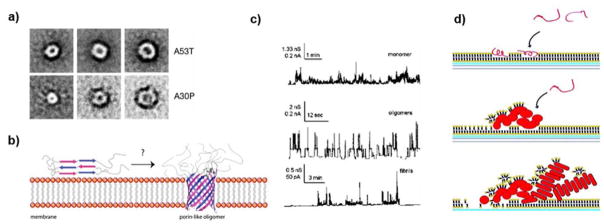

Figure 15.

Proposed mechanisms of membrane damage induced by αS aggregation. (a) Projection averages of annular oligomers formed by αS mutants A53T and A30P.271 (b) αS oligomer spans the membrane in a porin-like fashion to induce toxicity.284 (c) Oligomers but not monomers or fibrils induced frequent channel formation in planar lipid bilayers formed from diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine dissolved in n-decane in 1 M KCl, at a bias of +100 mV.297 (d) (Top panel) Monomeric αS adsorbed to a lipid bilayer. (Middle panel) Aggregation of αS monomers causes membrane thinning and lipid extraction. (Lower panel) Further incubation results in assembly of mature αS fibrils and disassembly of the lipid membrane.298 Copyright Nature Publishing Group, Portland Press and The American Chemical Society.

Cholesterol is proposed to be related to AD pathology although cholesterol stabilizes phospholipid bilayers against Aβ.104 Lipid ‘rafts’ or domains in the membrane enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids could modulate Aβ production, aggregation and toxicity.105 Sanders and co-workers106 showed that the C99 segment of APP bound to cholesterol and proposed that APP might act as a cholesterol sensor critical for the trafficking of APP to cholesterol-rich membrane domains. Cholesterol increases the thickness of phospholipid bilayers and may influence the proteolytic processing of APP and proportion of Aβ40 to Aβ42 produced. Lipid membranes are also susceptible to oxidative stress, as mentioned above as a mechanism for neurodegeneration in AD.98

2.6 Aβ toxicity and Alzheimer’s disease

The physiological markers of AD are progressive cognitive decline, synaptic loss, presence of extracellular β-amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles ultimately leading to neuronal cell death and a massive brain cell mass loss. To date, there is no drug that can prevent AD neurodegeneration probably because many pathways are activated during the uncontrolled production of Aβ peptides, although several candidates are in ongoing clinical trials. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that Aβ peptides accumulate at synapses, thereby disrupting the whole neuronal network.107 More specifically, complex interactions between Aβ peptides and both synaptic ion channels and mitochondria alter their physiological activities. Aβ peptides and, more particularly, the oligomers of Aβ have affinity for the glutamate108 and acetylcholine109 receptors, mediating the influx/efflux rate of critical mediators such as calcium ions. Aβ-mediated deregulation of these receptors – particularly NMDAR and AMPAR – has been linked to the impairment of plasticity and degeneration of synapses during AD.110

The observation that Aβ oligomers are able to co-localize within mitochondria has exposed another potential neurotoxic pathway.111 Aβ oligomers are able to alter the function of proteins involved in the mitochondrial fusion/fission process, which causes their fragmentation leading to the loss of neuron viability.112 Moreover, accumulation of Aβ peptides in synaptic mitochondria has been shown to decrease mitochondrial respiration and key respiratory enzyme activity, elevate oxidative stress, compromise calcium-handling capacity, and trigger apoptotic signals.113, 114 Finally, intracellular accumulation of Aβ peptides drastically reduces the lysosomal efficiency in removing damaged organelles and unfolded proteins, such as tau.115 Better understanding of the cell biology of the downstream effects of Aβ oligomers may uncover potential therapeutic targets for the prevention of AD.

2.7 Mitigation strategies and theranostics

With increased knowledge of the mechanism of fibril formation from the cleavage of APP to the kinetic modulation by extrinsic factors, several strategies to mitigate AD have emerged. Stabilizing the monomeric form of Aβ peptides is a direct strategy to limit the formation of oligomeric species. Peptides that specifically interact with the pro-aggregating domains have been developed, as recently shown with a cyclopeptide, to inhibit Aβ amyloidogenesis.116 Antibody-based immunotherapy is another strategy to mitigate AD. For instance, a promising candidate, aducanumab, has shown high selectively against aggregated Aβ, induced significant reduction of insoluble and insoluble Aβ population and slowed clinical decline; although the outcome of ongoing Phase 3 clinical trials are needed to confirm these promising observations 117. The affinity of Aβ peptides for transition metals was seen as another area for potential development of AD therapeutics, but so far chelators, such as D-penicillamine, have not produced any clinical improvement.118

After drugs (e.g. bapineuzumab and solanezumab) which seek to lower existing Aβ loads had failed, increasing attention was paid to BACE drugs that interfere with the process that creates Aβ. However, Merck recently closed its trial for the BACE inhibitor, verubecestat, in mild-to-moderate AD after concluding that the drug had little chance of success.119 A particular focus has been to decrease the production of apparently toxic Aβ peptides by inhibiting BACE1 activity.120 For instance, the cholesterol-rich endosomal environment, which promotes selective processing of APP by BACE1, has been pursued as a target using a membrane-anchored BACE1 transition-state inhibitor linked to a sterol moiety to generate highly effective BACE1 inhibitors.121 Treatment with BACE inhibitor IV, which does not change the APP concentration level, was shown to prevent mitochondrial abnormalities caused by Aβ.122 Reducing the activation of caspases, such as caspase 3, can improve neuronal growth and decrease abnormal tau species, which may be an interesting therapeutic pathway for the treatment of AD.123

Since the approval of memantine in 2003, no new AD drug candidate has passed the FDA approval, with an alarming failure rate of 99.6%, the highest in all serious disease research programs.124 A growing strategy in integrating therapeutics and personalized diagnostics has recently emerged as a promising route. Based on nanomedicine, small molecules – necessary to overcome prerequisite to cross the brain blood barrier – have been developed to label and simultaneously inhibit oligomerization of Aβ peptides.125 The term theranostic has thus been coined to characterize these new inhibitor-biomarkers, many based on scaffolds of fluorescent probes such as ThT, to detect fibril formation in vivo and alter their accumulation.126 These new strategies have been made possible by improved understanding of the assembly mechanism of Aβ at the molecular level, which will continue to guide rational drug design against AD.

3. IAPP and type 2 diabetes

3.1 Function of IAPP

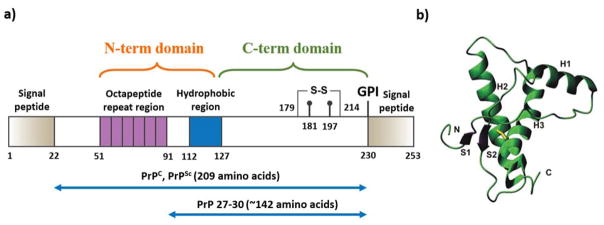

Human islet amyloid polypeptide (IAPP, a.k.a amylin) is a 37-residue peptide hormone co-secreted with insulin from pancreatic β-cell islets. The IAPP physiology has been recently reviewed by Westermark et al.127 Briefly, the peptide is synthesized from a 67-residue precursor peptide, proIAPP, by proteolysis and posttranslational modifications, such as the C-terminal amidation and a disulfide bond formation between residues 2 and 7 (Fig. 7a).128, 129 Both IAPP and insulin are regulated by similar factors with a common regulatory promoter motif.130 Before secreting to the circulation, IAPP is stored together with insulin inside the β-cell granules at high concentrations. IAPP functions as a synergistic partner of insulin to control the blood glucose level by slowing down gastric emptying, inhibiting digestive secretion, and promoting satiety.131, 132 IAPP is also known to play a role in bone metabolism along with calcitonin and calcitonin gene-related peptides.133

Figure 7.

Structural studies of IAPP. (a) The primary structure of IAPP peptide. Solution NMR structures of IAPP monomers stabilized by SDS micelle at (b) pH 4.2 (PDB: 2KB8) and (c) pH 7.3 (PDB: 2L86). (d) Solution NMR structure of IAPP whose aggregation is reduced at pH 5.3, 4 °C, and 100 μM in concentration (PDB: 5MGQ). Residues 1–19 are colored purple and His18 is in sticks. The overall U-shaped IAPP fibril models are derived from experimental constraints by (e) solid-state NMR134 and (f) X-ray crystallography of short peptides.135 In panels (e) and (f), two peptides in the fibril cross-section are shown in sticks viewed along the fibril axis. (g) EPR constraints were applied to reconstruct the fibril model of disulfide reduced IAPP. The sub-panels A and B correspond to views along and perpendicular to the fibril axis, and sub-panels C and D are the accordingly reconstructed fibril models with two different views perpendicular to the fibril axis.136 Copyright The American Chemical Society, John Wiley & Sons, and The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

A hallmark of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the formation of IAPP-enriched amyloid plaques found in the pancreas of patients. Insulin resistance in T2D leads to increased production of insulin and also IAPP by β-cells because of their shared synthesis and secretion pathways. Since IAPP is one of the most amyloidogenic peptides known, over-production of IAPP in β-cells promotes the accumulation of toxic aggregates. Other studies also suggested that insufficient process of proIAPP and accumulation of intermediately processed peptides might promote the formation of amyloid fibrils, but the detailed molecular mechanisms remain unclear. The disease progression is marked by β-cell death and loss of β-cell functions, resulting in insulin deficiency and diabetic dependence on external insulin sources.

3.2 Atomic structures of IAPP and IAPP amyloid fibrils

Structural characterization of IAPP monomers is extremely challenging due to the high aggregation propensity of the peptide. By reducing IAPP aggregation with detergent micelles, solution NMR studies have been used to study the structure of IAPP monomers.137–139 It has been shown that SDS micelles stabilize IAPP in a highly helical form (Fig. 7b–d). At low pH, the peptide assumes an extended alpha-helix. At neutral pH, the peptide has been found to form a kinked helix around residue H18. Such structural difference is likely due to the electrostatic interaction of the protonated His18 at low pH with the anionic SDS. Combing low pH, low temperature, and low peptide concentrations to hinder IAPP aggregation in solution, an NMR study has recently revealed that the N-terminus of IAPP remains alpha-helical while the C-terminus is unstructured, which are consistent with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of isolated IAPP monomers.140

The fibril aggregates of IAPPs share the same characteristic cross-beta structures of known fibrils.141 Although the atomic structure of full-length IAPP amyloid fibrils is not available, several model structures have been proposed based on various experimental methods. Using constraints derived from solid-state NMR, Tycko et al. proposed a U-shaped fibrils model where residues 8–17 and 26–37 form two beta-sheets (Fig. 7e).134 Based on X-ray microcrystallography structures of two short peptides, Eisenberg et al. reconstructed a similar fibril model with main differences in the side-chain packing (Fig. 7f).135 Recently, EPR studies of disulfide-reduced IAPP led to a different fibril model (Fig. 7g), where the peptide still adopts a U-shape with two strands separated by a longer distance.136 The two strands in a single peptide have to be staggered with respect to each other to have the appropriated inter β-sheet packing and distances.

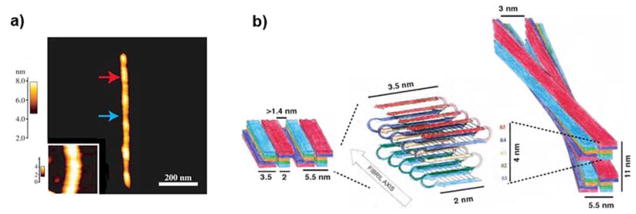

3.3 Mesoscopic structure of IAPP amyloids

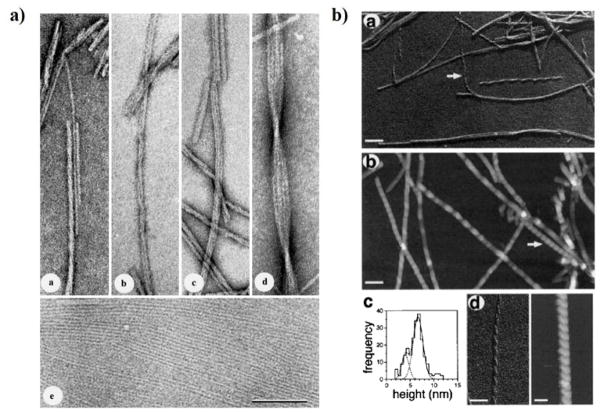

The morphology of IAPP amyloid fibril has been studied by both TEM and AFM.142, 143 IAPP fibrils at the mesoscopic scale displayed significant structural polymorphism, including ribbon-like, sheet-like and helical fibril morphologies (Fig. 8). The ribbons and sheets were formed by lateral association of 5-nm wide protofibrils (Fig. 8a). Most of the fibrils were found in left-handed coil morphology with cross-over periodicities of either ~25 nm or ~50 nm (Fig. 8b). Based on these observations, Goldsbury et al. proposed that the building block of IAPP fibrils is the 5 nm protofibril which can either self-assemble laterally into ribbon-like or sheet-like arrays or coiled fibrils.143 The atomic models of IAPP fibrils are consistent with these TEM and AFM observations.

Figure 8.

Morphology of IAPP amyloid fibrils. (a) Lateral association of ribbon-like IAPP protofibrils revealed by TEM of freeze-dried tungsten-shadowed samples. Subpanels a–d depict ribbons assembled by lateral association of 1 to 4 protofibrils. Ribbons with multiple protofibrils often crossed over in a left-handed sense at moderately regular intervals. Subpanel e corresponds to lateral assembly of protofibrils into single-layered, sheet-like arrays. Scale bar: 100 nm. (b) IAPP fibrils with coiled morphologies.142, 143 Subpanels a and b denote coiled fibrils visualized by TEM and AFM, respectively. Arrows point to a left-handed fibril with a 25 nm cross-over periodicity. Longer periodicities of approximately 50 nm can also be seen in both subpanels. Subpanel c shows the AFM height distribution, and d compares the 25 nm periodicity fibril in TEM and AFM. Scale bars: 100 nm in subpanels a, b; and 50 nm in d. Copyright Elsevier.

3.4 IAPP toxicity and type 2 diabetes

Mounting studies suggest that IAPP aggregation and the related toxicity are associated with T2D. IAPP variants from diabetes-prone primates and cats form amyloid aggregates readily in vitro, while those from diabetes-free rodents and pigs feature significantly lower aggregation propensities.144 A naturally-occurring polymorphic S20G mutation renders IAPP more aggregation prone;145 and an Asian subpopulation carrying this mutation is subjected to early onset of T2D.146 IAPP aggregated rapidly upon transplanting human islets into nude mice, and the aggregation process occurred before the recurrence of hyperglycermia and was correlated with β-cell death.147, 148 Transgenic mice expressing human IAPP variant started to develop diabetes.149 Moreover, as with other amyloid proteins,150, 151 IAPP amyloid aggregates are toxic to pancreatic islet cells.152 Therefore, amyloid aggregation of IAPP is related to β-cell death in T2D.153

3.4.1 Oligomers vs amyloids

Amyloid aggregation is a nucleation process, featuring a characteristic all-or-none sigmoidal kinetics. The final mature amyloid fibrils have been found relatively inert and have no significant cell toxicity. In contrast, freshly dissolved IAPP have been found to be highly toxic to islet cells and also cause membrane instability in vitro,154 where the small and soluble aggregation intermediates of IAPP are expected to accumulate before the rapid fibril growth. IAPP oligomers have also been found to disrupt cell coupling, induce apoptosis, and impair insulin secretion in isolated human islets.155 Additional evidence include transgenic mice studies,149, 156 where amyloid deposits were not always observed under optical microscopy in animals starting to show diabetic symptoms, and there was a lack of autocorrelation between beta cell loss and amyloid deposits in these models.157 In addition, inhibition of the formation of insoluble IAPP aggregates but not oligomers by either small molecules158 or proteins159 did not reduce the cytotoxicity. Hence, these results among many others led to the toxic oligomer hypothesis in T2D.160, 161

As the aggregation intermediate species, IAPP oligomers are not well-defined and are extremely challenging to characterize due to their transient and heterogeneous nature. Many in vitro studies support the accumulation of helical intermediates populated along the aggregation pathway.162–164 It has been suggested that the N-terminal helixes of soluble IAPPs (Fig. 7d) are amphiphilic and hydrophobic interactions drive the helix association, which in turn increases the local concentration of the C-terminus containing the amyloidogenic sequence 20–29.165 Both discrete molecular simulations (DMD) of IAPP dimers140 and X-ray crystallography study of IAPP fused to a maltose-binding protein164 supported this scenario. On the other hand, ion mobility mass spectroscopy (IM-MS) combined with MD simulations pointed to a different model of early intermediate states with beta-hairpin dimers.166 The difference is possibly due to the enhanced sampling method - replica exchange167 - used in the MD study, which reduced the free energy barrier of the helix unfolding in the N-terminus. Further experimental and computational studies are necessary to fully understand the structure and dynamics of IAPP oligomers in order to identify the toxic species and the molecular mechanism of IAPP toxicity.

3.4.2 The endogenous inhibition of IAPP aggregation

IAPP is highly aggregation prone and readily forms amyloid fibrils in vitro at μM concentrations within hours.168 However, before its secretion to the bloodstream IAPP is stored inside β-cell granules at mM concentrations for hours without apparent formation of toxic aggregates in healthy individuals.169 Therefore, the physiological environment inside β-cell granules natively inhibits the formation of toxic IAPP aggregates while disruption to the native inhibition environment may lead to amyloid aggregation of IAPP, causing β-cell death.

Islet β-cell granules have a distinct cellular environment.170 First, the pH value inside the granules is 5.5, which is below the physiological pH of 7.4. Second, β-cell granules have one of the highest concentrations of Zn2+ ions in the entire human body. The high concentration of zinc in β-cell granules, maintained by a β-cell-specific zinc transporter — ZnT8,171 is believed to be important for the efficient storage of insulin in β-cell granules: zinc coordinates the formation of insulin hexamers, which form insulin crystals as the dense core of β-cell granules.172 Third, beside IAPP peptides β-cell granules also have other molecules in large quantities, including insulin and proinsulin C-peptide. Insulin is co-secreted with IAPP by β-cells at a ratio of ~100:1 in healthy individuals, and such a high insulin-to-IAPP ratio is reduced to ~20:1 in T2D patients.173 The C-peptide is a part of the proinsulin sequence connecting A- and B-chains of insulin. Protease-processing of proinsulin results into mature insulin and C-peptide with an equal molar concentration inside β-cell granules.

Low pH

Inhibition of IAPP aggregation at low pH has been observed in vitro. At low pH, an increase in the lag time and a decrease in the growth rate of IAPP fibrillization was observed.174, 175 The electrostatic repulsion between IAPPs with protonated histidine18 (His18) is responsible for inhibiting the self-association of IAPP at low pH,176 supported by DMD simulations of IAPP dimerization with and without protonation of His18.177 However, since the pH value inside β-cell granules is close to the isoelectric point of His18174, 178 and a significant portion of IAPP is still unprotonated, interactions of IAPP with other granule components are necessary for natively inhibiting the peptide amyloid aggregation at high concentrations.

Insulin

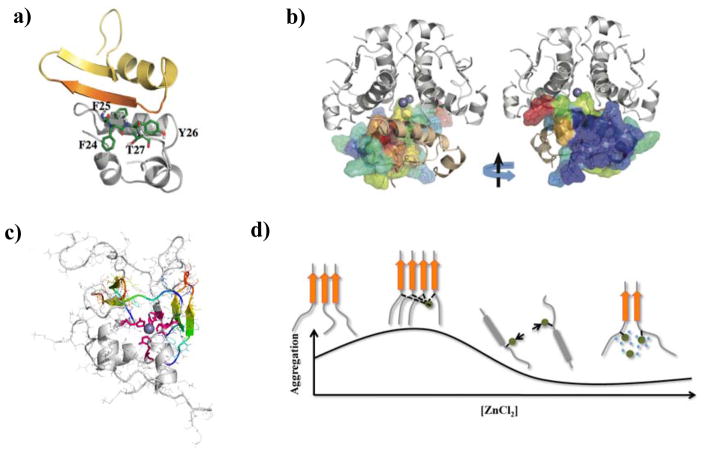

In vitro experiments have revealed that insulin is a potent IAPP aggregation inhibitor, which can significantly slow down aggregation at sub-stoichiometry concentrations.180 Several studies, including peptide mapping,181 IMS-MS combined with MD simulations,182 and DMD studies140 suggested that the B-chain of insulin can bind IAPP. Computational studies with atomistic DMD simulations showed that both insulin monomers and dimers (but not the zinc-bound hexamer as the IAPP-binding interface is buried) could bind IAPP monomer and inhibit IAPP self-association by competing with the amyloidogenic regions important for aggregation, subsequently preventing amyloid aggregation (Fig. 9a,b). The preferred binding of insulin with the amyloidogenic region in the beta-strand conformation (Fig. 9a) suggests that insulin can also cap the fibril growth, consistently with the observed sub-stoichiometric inhibition of IAPP aggregation by insulin. Comparing to high zinc concentrations where insulin is insoluble in the crystal form,183 zinc-deficiency due to loss-of-function mutations of ZnT8 shifts the insulin oligomer/crystallization equilibrium toward soluble monomers and dimers, which can efficiently inhibit IAPP aggregation and reduce T2D risk in the subpopulation carrying these mutations.184 However, since IAPP is found almost exclusively in the soluble halo fraction of β-cell granules while insulin is mostly insoluble in the core, the balance of other granule components such as Zn2+ and/or C-peptide co-localized with IAPP appears crucial for maintaining the native state of IAPP.

Figure 9.

Effects of β-cell granule components on IAPP aggregation. (a) A representative IAPP-insulin complex from DMD simulations,140 where the amyloidogenic residues of IAPP (residues 22–29) are shown in orange. The residues in the B-chain of insulin important for binding IAPP are highlighted in stick representation. (b) The residues of an insulin monomer are colored according to IAPP binding frequencies in the structure of an insulin hexamer. The view with an 180° rotation is also presented. The residues with strong IAPP-binding are located at the insulin monomer–monomer interface. (c) A representative IAPP tetramer with His18 (highlighted as sticks in pink) coordinated by a Zn2+ (blue sphere) from DMD simulations.179 The amyloidogenic sequences from each IAPP monomer are highlighted in rainbow colors. (d) A mechanistic scheme demonstrating the dependence of IAPP aggregation on relative zinc concentration. Copyright The American Chemical Society and Elsevier.

Zinc

In an early study by Steiner and co-workers where ZnCl2 was added to ~250 μM IAPP solution, aggregation promotion was observed.185 This promotion effect leveled off till ~1 mM zinc ion was added, but no data at higher salt concentrations was reported. In later experimental studies, IAPP aggregation inhibition was observed at low zinc concentrations (5 and 10 μM, but relatively high zinc/IAPP stoichiometry), followed by a partial recovery of aggregation at very high stoichiometry (~50–100).186, 187 A “two-site binding” model, where a high affinity binding with His18 stabilized non-aggregating oligomers but an unknown weaker secondary binding promoted amyloid fibril formation, was proposed.187 However, this model cannot account for aggregation-promotion at low ion/protein stoichiometry185 (e.g., in the case of 10 μM of IAPP there was a single data point with increased aggregation at ~25 μM of zinc.186). Combining DMD simulations with experimental characterizations179, Govindan et al. developed an alternative model that was consistent with the experimentally-observed concentration-dependent effect of zinc on IAPP aggregation. At low zinc/IAPP stoichiometry, the IAPP oligomers cross-linked by zinc were aggregation-prone due to high local peptide concentrations (Fig. 9c). As ion/protein stoichiometry increased, each IAPP tended to bind only one zinc ion at His18. The electrostatic repulsion between the bound zinc ions (+2e) inhibited IAPP aggregation, similarly to the low pH condition where IAPP aggregation was inhibited by protonated His18 (+1e).176 With zinc concentration kept increasing, the screening effect due to high salt concentrations reduced electrostatic repulsion, and allowed for the aggregation to recover (Fig. 9d).186, 187

C-peptide

Without zinc binding, C-peptide is disordered in water and weakly helical in trifluoroethanol (TFE) solution.188 The peptide contains five acidic amino acids. Alanine scan coupled with MS experiments suggest that all these acidic amino acids bind zinc ions and the binding is 1:1 in stoichiometry.189 It has been found that zinc-binding may induce structural changes.190 It was hypothesized that multiple negatively charged acidic amino acids in C-peptide allow the binding with multiple IAPP peptides, locally increase IAPP concentration and subsequently promote IAPP aggregation. Upon binding zinc, C-peptide adopts specific secondary and tertiary structures with reduced net charges, which might bind and stabilize IAPP peptides in the aggregation incompetent state. In addition, other granule molecules including proIAPP191 and proInsulin may also contribute to the native inhibition of IAPP aggregation and cytotoxicity in beta-cells and are subject to future investigations.

3.4.3 IAPP-membrane interactions

It has been proposed that IAPP exerts cytotoxicity by membrane disruption.154, 192, 193 The positively charged IAPP can bind anionic cell membranes and lipid micelles, and the peptide conformational and aggregation propensity change upon binding also depending on the membrane curvature.192 Binding of IAPP with small micelles was found to stabilize the peptide in helical conformation (Fig. 7), while absorption of IAPP on flat membrane accelerated the peptide aggregation.194 Using a lipophilic Laurdan dye for examining MIN6 cell membranes upon exposure to freshly dissolved IAPP as well as mature amyloid fibrils, Pilkington et al. found that all species, especially fresh IAPP, enhanced membrane fluidity and caused losses in cell viability.195 The cell generation of ROS, however, was the most pronounced with mature amyloid fibrils. This study suggested a correlation of cytotoxicity with changes in membrane fluidity rather than ROS production.

The exact mechanism by which IAPP oligomers disrupt the cell membrane is under active investigation. Pore formation by amyloid peptides has been suggested to be important for membrane disruption.196–198 The amyloid pore model is strongly supported by single channel recordings of IAPP on planar membranes.196, 199, 200 A detergent-like mechanism has also been advocated, where the mosaic-like opening and closing of transient defects within the membrane (also see Fig. 15d in section 4 for αS) was supported by AFM studies showing large-scale defects in the lipid bilayer upon prolonged exposure to IAPP.201 However, the strong correlation between fibril formation and membrane disruption by this mechanism202 is inconsistent with the toxic oligomer hypothesis. Recently, biophysical measurements in conjunction with cytotoxicity studies showed that nonamyloidogenic rat IAPP is as effective as IAPP at disrupting standard anionic model membranes under conditions where rat IAPP did not induce cellular toxicity, suggesting that there is no direct relationship between disruption of model membranes and induction of cellular toxicity.203 Therefore, the connection between IAPP cytotoxicity and membrane disruption remains inconclusive.

3.5 Mitigation strategies and theranostics

As with other amyloid diseases,204–206 inhibition of IAPP aggregation is an attractive therapeutic strategy to prevent β-cell death207 and halt the progression of diabetic conditions in T2D. Various approaches have been explored to reduce aggregation-induced IAPP cytotoxicity, through the use of peptides, peptide-mimetics,208–211 small molecules212–223, and nanoparticles (NPs)224–226. Non-amyloidogenic sequence variants of IAPP including rat IAPP227 have been found to inhibit the fibril formation of human IAPP,208, 209 and the inhibition efficacies can be improved by synthesizing peptide mimetics with conformational restraints.210, 211 Targeting the early helical intermediate states of IAPP aggregation162–164, small molecule peptidomimetics212, 213 have been designed to mimic helixes that complementarily bind to the N-terminal helix of IAPP. Another attractive set of amyloid aggregation inhibitors are small-molecule polyphenols221 such as epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG),228 curcumin,219, 220 and resveratrol,229 which inhibit aggregation and reduce the related cytotoxicity of IAPP230 as well as other proteins and peptides such as Aβ.231 These polyphenols have the advantage of being naturally occurring, and are non-toxic at moderate concentrations. Despite well-known therapeutic benefits of small molecules,232 however, pharmacological applications of these polyphenols are limited due to some common issues, such as their poor water solubility.233

Several studies have examined the anti-amyloid mechanisms of small molecules and NPs. For example, IMS-MS experiments showed that EGCG exerted an inhibitory effect on IAPP aggregation through direct binding of EGCG to the peptide215 and alternating the aggregation pathways.228 Using simulations of the amyloidogenic segment of IAPP, resveratrol was found to bind and prevent the lateral growth of the fibril-like β-sheets.235 In another work, resveratrol was found to bind weakly to IAPP and reduce inter-peptide contacts.236 A recent computational study showed that resveratrol altered the structure of an IAPP pentamer,237 which was modelled by the amyloid fibril structure derived from solid-state NMR.134 By modelling the effects of polyphenols like resveratrol and curcumin on the initial self-association and aggregation of IAPP in DMD simulation,234 Nedumpully-Govindan et al. showed that these polyphenols inhibited IAPP aggregation by promoting “off-pathway” oligomers with the hydrophobic polyphenols forming the core (Fig. 10a). The peptides were stabilized in the aggregation-incompetent helix-rich state by burying their hydrophobic residues inside the core and exposing the hydrophilic residues. Graphene oxide nanosheets displayed strong inhibition effects on IAPP aggregation and associated cytotoxicity because strong binding affinity rendered the peptides to bind with the nanosheets rather than between themselves.225 OH-terminated polyamyloidoamine (PAMAM-OH) dendrimers inhibited IAPP aggregation and cytotoxicity, where the polymeric NPs encapsulated and stabilized monomeric IAPP in their hydrophobic interior (Fig. 10b).224 In general, these inhibitors all reduced the population of the oligomeric species, thereby reducing IAPP toxicity.

Figure 10.

Inhibition of IAPP aggregation. (a) Left: High-throughput dynamic light scattering measurement of IAPP size distributions with and without resveratrol (2:1 ligand/IAPP ratio). Right: Distribution of IAPP aggregates of different molecular weights with and without resveratrol in silico. Stable IAPP/resveratrol oligomer has the resveratrol molecules forming a nano-sized core and IAPP peptides a corona, which prevents aggregation.234 (b) Left: a typical IAPP dimer in DMD simulations. Right: Binding to a PAMAM-OH dendrimer (spheres) inhibits self-association of the amyloidogenic sequences (yellow region) between two IAPP peptides.224 The peptides are shown in cartoon representation with rainbow color from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). Copyright Nature Publishing Group and John Wiley & Sons.

4. Alpha-synuclein and Parkinson’s disease

4.1 Function of alpha-synuclein

Alpha synuclein (αS) is a 140-residue small protein highly concentrated in presynaptic terminals,238 making up as much as 1% of all proteins in the cytosol of brain cells. Small traces of αS are also found in the heart, gut,239 muscles and other tissues, reminiscent of the confounding bodily distributions of Aβ and IAPP beyond their purported origins. In the intra-neuronal space, αS assumes an equilibrium between an unfolded monomeric conformation and a membrane-bound state that is rich in alpha helices.240 The precise physiological role of αS is unclear, but is relevant to the modulation of neurotransmitter dopamine release, ER/Golgi trafficking, and synaptic vesicles.241 The membrane-bound αS influences lipid packing and induces vesicle clustering through physical and physicochemical interactions, while αS in the multimeric form has been shown to promote SNARE complex assembly during synaptic exocytosis.240

Aggregated αS mediates dopaminergic neurotoxicity in vivo.244 However, the precise mechanisms by which αS lends toxicity to host cells remain unclear. Pathologically, αS is a major component of Lewy bodies and neurites, the intracellular protein aggregates first identified by Spillantini et al. in 1997 (Fig. 11)242 and hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease (PD), Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Compared with the ambiguous pathology of αS, the neuritic pathology of β and γ synuclein homologs does not appear widespread, and both neuroprotective and neurotoxic potentials of β synuclein have been reported.245

Figure 11.

(a) (Large image) Pigmented nerve cells containing αS-positive Lewy body (thin arrows) and Lewy neurites (thick arrow).242 Small image: a pigmented nerve cell with two αS-positive Lewy bodies. Scale bar: 8 μm. (b) Hypothesized αS toxicity and spread of pathology in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD). UPS: Ubiquitin proteasome system.243 Copyright Nature Publishing Group.

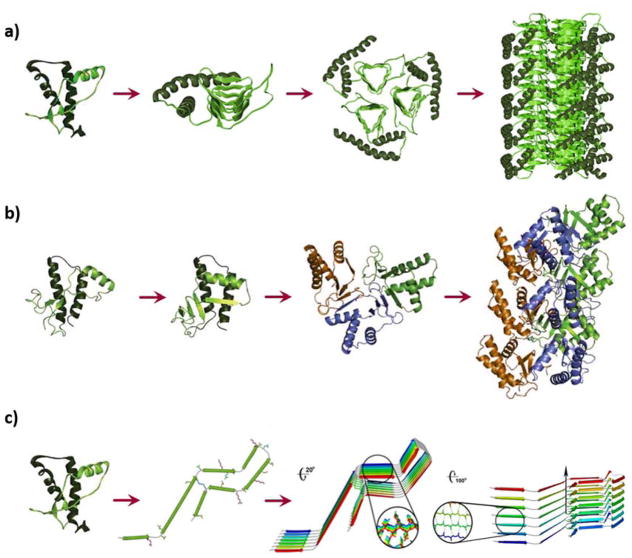

4.2 Atomic structures of alpha-synuclein and alpha-synuclein amyloid fibrils

The sequence of αS is encoded by the SNCA gene and can be divided into three distinct domains: a) the amphipathic N-terminal domain (1–60), which contains consensus KTKEGV repeats and has alpha-helical propensity, b) the central domain (61–95) or the non-amyloid-beta component (NAC) that is highly hydrophobic and amyloidogenic, and c) the acidic C-terminal domain (96–140) which contains negatively charged and proline residues to afford protein flexibility but no apparent structural propensity.246 High resolution ion-mobility mass spectroscopy has revealed that HPLC-purified αS is autoproteolytic, giving rise to a number of small molecular weight fragments upon incubation. In particular, the fragment of residues 72–140 contains majority of the NAC region and aggregates faster than full-length αS.247 These autoproteolytic products may serve as intermediates or cofactors in the aggregation of αS in vivo.

The atomic structures of fragmental and full-length αS in the fibrillar form have been elucidated over the past decade (Fig. 12). Using quenched HD exchange Vilar et al. identified five β-strands within the fibril core comprising residues 35–96 and with solid-state NMR spectroscopy the presence of β-sheet secondary structure within the fibril core of residues 30–110.241 This study has further detailed the mesoscopic features of αS fibrils, as we will visit in the next sub-section.

Figure 12.

Landmark studies concerning the structures of αS fragments with respect to its full 140 residues consisting of N terminus, NAC and C terminus.248 The researcher teams are chronicled on the left while the employed techniques are abbreviated on the right. EPR: electron paramagnetic resonance; ssNMR: solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance; HD: hydrogen-deuterium exchange; SDSL: site directed spin labelling. Copyright Nature Publishing Group.

Based on micro-electron diffraction Rodriguez et al. revealed small crystal structures of the toxic NAC core (68–78, or NACore) and the preNAC segment (47–56) of αS, at spatial resolution of 1.4 Å (Fig. 13a).248 The NACore strands stacked in-register into β-sheets. The sheets were paired, forming steric-zipper protofilaments as observed for other types of amyloidogenic proteins. Notably, each pair of the sheets contained two water molecules, and each was associated with a threonine side chain within the interface. X-ray fiber diffraction patterns further revealed a similarity of the NACore to full-length αS fibrils.248

Figure 13.

(a) Top and side views of the structures of NACore (orange; residues 68–78, sequence also see Fig. 12) and PreNAC segments (blue; residues 47–56, sequence also see Fig. 12). The A53T mutation in PreNAC is shown in black.248 (b–e) Three-dimensional structure of a full αS fibril. (b) A central monomer from residues 44 to 96 looking down the fibril axis showing the Greek-key motif of the fibril core. (c) Stacked monomers showing the sidechain alignment between each monomer down the fibril axis. (d) Residues 25 to 105 of 8 monomers displaying the β-sheet alignment of each monomer in the fibril and the Greek-key topology of the core. (e) Overlaid ten lowest energy structures, showing sidechain positions within the core. Residues 51–57 are indicated in red with side chains removed.249 Copyright Nature Publishing Group.

In a more recent study, Tuttle et al. established the atomic structure of full-length αS fibrils based on 68 spectra, using 2D and 3D ssNMR.249 The fibrils were collected from cell culture and shown to adopt a β-serpentine arrangement (Fig. 13b–e). The fold exhibited hydrogen bonds in register along the fibril axis, orthogonal to the hydrogen bond geometry in a standard Greek-key motif unseen for other fibrils (Fig. 13d).249 The innermost β-sheet contained amyloidogenic residues 71–82, while the sidechains in the core were tightly packed (Fig. 13e). Compact residues facilitated a close backbone-backbone interaction: A69–G93 bridged the distal loops of the Greek key, and G47–A78 rendered a stable intermolecular salt bridge between E46 and K80. Hydrophobic sidechain packing among I88, A91 and F94 established the innermost portion of the Greek key. Residues 55–62 were disordered, consistent with that reported by Comellas et al.250 Collectively, the steric zippers, glutamine ladder and intermolecular salt bridge contributed to the structural complexity and stability of the fibril. However, it remains uncertain whether such atomic structure reflects that of αS fibrils extracted directly from PD patients.

4.3 Mesoscopic structure of alpha-synuclein amyloids

The morphology of αS fibrils has been examined with AFM251–253 and cryoelectron microscopy.241 A hierarchical assembly model (HAM) was proposed by Inonescu-Zanetti et al.254 to describe the architecture of immunoglobulin light-chain protein SMA fibrils assembled from smaller subspecies and has shown general applicability to the nanoscale assemblies of Aβ, αS and IAPP as well as SH3 domain, lysozyme, SMA, β2-microglobulin and beta-lactoglobulin.142, 251, 252, 255–260 Alternatively, a new packing model was proposed by Sweers et al.,261 in attempt to reconcile the morphological and mechanical data observed for two distinct fibril species of E46K, a mutant of αS. Nonetheless, according to the HAM, protofilaments are established by the nucleated polymerization kinetic model, in which the protofilaments elongate by the addition of monomeric, partially folded intermediates to their growing ends. The protofilaments then interact with each other to form protofibrils, each consisting of twisted 2–3 protofilaments, and two protofibrils entwine to form mature fibrils and, eventually, plaques. The driving force for such stepwise assembly is both electrostatic and hydrophobic.254

The HAM model predicts the occurrence of periodicity for protofilaments and fibrils, which assume twisted morphologies. Such periodicity is driven by a balance between mechanical forces dominated by the protofilament elasticity and electrostatic forces due to the distribution of hydrophobic regions and charge along the protofilament backbone,253 as well as by the inherent chirality of constituting amino acids and β-sheets/helices of the fibrils. The average heights of αS protofilaments and fibrils were 3.8 nm and 6.5 nm, respectively, while the periodicity of αS fibrils ranged from 100~150 nm as determined by AFM (Fig. 14a).253 These parameters are consistent with immunoelectron microscopy of filaments extracted from the brains of patients with DLB and multiple system atrophy,262 and agree with high-resolution cryoelectron microscopy where twisted protofilament of ~2×3.5 nm in boundaries and 120 ±10 nm in periodicity were observed leading to the proposal of a folded αS fibril model (Fig. 14b).241 The cross-section of individual αS monomers in the fold was trapezoid instead of circular, resulting in a two-fold increase in moment of inertia (Sweers 2012).263 Though not substantiated, such non-circular packing of monomers could also hold true for other β-sheet folded proteins.261, 263 In addition, curly αS fibrils prepared by filtration-like steps during aggregation possessed a persistence length of 170 nm, while straight αS fibrils from unperturbed aggregation displayed persistence lengths of up to 140 μm.264

Figure 14.

(A) AFM image showing a periodicity of 100–150 nm along an αS protofibril. The peak (red arrow) to trough (blue arrow) differs by ~1 nm in height. (Inset) A section of a protofilament with an average height of 3.8 nm.253 (B) Proposed fold of an αS fibril. A monomeric αS within a protofilament (center). Incorporation of protofilaments into a straight or twisted fibril is illustrated in the left and right panel, respectively.241 Copyright Cell Press and National Academy of Sciences.

4.4 Alpha-synuclein toxicity and Parkinson’s

4.4.1 Oligomers vs amyloids

Natively unfolded αS undergoes a transition to partially folded intermediates prior to fibril formation.265 Such partially folded conformations are favored by mutations266 or changes in pH, ionic strength and temperature and are thought to be critical intermediates in the transition to amyloid fibrils.253 Clearly, such dynamic transition has an important bearing on αS toxicity, as evidenced by a body of literature focused on the complex roles of αS oligomers and amyloids.

The aggregation of αS follows a nucleation polymerization pathway involving prefibrillar species of remarkable conformational plasticity,267 both transient and stable. Specifically, it is postulated that αS aggregation takes place in the cytoplasma or in association with the cellular membrane. In the cytosol, soluble monomers interact to form unstable dimers, which develop into oligomers and, subsequently, fibrils.268 The current understanding concerning αS toxicity follows the narrative of the “toxic oligomer hypothesis”,251 in that the oligomeric species are more toxic than the fibrillar form,251, 269–272 as similarly proposed for Aβ273–279 and IAPP.280 However, due to the different structural characteristics and aggregation rates, different cellular environments, as well as prion-like cell to cell spreading and crosstalk of proteins of different origins and pathologies, this generalization remains putative.281, 282

In an early in vitro study, Conway et al. compared the rates of disappearance of monomeric αS and appearance of fibrillar αS for wide-type and two mutant proteins A53T and A30P.251 The differences between the trends suggested the occurrence of nonfibrillar αS oligomers. Using sedimentation and gel filtration chromatography, the researchers identified spheres (range of heights: 2–6 nm), chains of spheres (protofibrils), and rings/annulars (heights: ~4 nm) from fibrils (~8 nm in diameter) by AFM. For a comprehensive account of αS oligomers and their in vitro preparation protocols, readers may refer to a recent review by van Diggelen et al.283

Using attenuated total reflection-Fourier-transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy Celej et al. revealed that isolated αS oligomers adopted an antiparallel β-sheet structure, whereas fibrils assumed a parallel arrangement.284 Notably, antiparallel β-sheet structures have also been reported for the oligomeric structures of Aβ, β2-microglobulin and human prion peptide PrP82–146.284 Such contrasting features in secondary structure between the oligomers and fibrils entail differences in conformational change, affinity and mode of interaction when binding with the cell membrane, further compounded by the differences in aspect ratio and surface hydrophobicity between the two species. The toxicities of αS oligomers and amyloid protein oligomers in general have been postulated as an inherent property.285 Unlike amyloid fibrils, the oligomers share similar structural properties273, 286 and possess higher portions of random coils and helical structures. Consequently, the exposed hydrophobic surfaces of the oligomers could mediate interactions with intracellular proteins to trigger aberrant cellular pathways.

Celej et al. found that purified αS oligomers spheroidal and polydisperse (10–60 nm), while αS fibrils were unbranched of 6–10 nm in diameter and micrometers long when examined under electron microscopy.287 These isolated oligomers were on-pathway intermediates sharing the same structural motif with other prefibrillar oligomers and possessing no canonical cross-β fibril structure.284 Curiously, the αS oligomers were recognized by A11 antibody, which also targeted the oligomeric but not monomeric or fibrillar forms of Aβ, prions, and IAPP.273, 288

While it remains debatable whether αS oligomers are intermediates in the process of amyloid formation, or precursors to fibrils, or byproducts of fibril elongation, or associated with a pathway of aggregation different from the standard amyloid fibrillization,269 there is little ambiguity that αS oligomers are toxic, as validated by in vitro and animal models.272, 273, 289, 290

4.4.2 Alpha-synuclein-membrane interactions

Towards understanding the origin of amyloid protein toxicity, much research over the past two decades has been focused on the interactions of the proteins as well as their aggregation products with cell membranes, model lipid vesicles, or lipid rafts. This focus is especially justified for αS considering its strong functional association with synaptic vesicles and its cell-to-cell spreading.291 From a biophysical standpoint such interactions may be understood as a manifestation of the structural attributes of αS (sequence, charge and hydrophobicity), as well as the changing properties of αS from soluble and disordered monomers to soluble and less random oligomers, and to waxy and highly ordered fibrils and plaques.

Research concerning protein-membrane interaction should take into consideration of two convoluting aspects: protein aggregation modulated by a model lipid bilayer or cell membrane, and membrane integrity perturbed by protein aggregation. Numerous studies have confirmed that lipid membranes can speed up the process of protein fibrillization due to the amphiphilicity of both interactants.292, 293 Specifically, the N-terminal region of αS, containing 7 amphiphilic imperfect repeats each of 11-residues, can initiate electrostatic interaction with anionic lipid head groups. The NAC region of the protein can establish hydrophobic interaction with lipid fatty acyl tails to promote membrane partitioning.294 Upon membrane exposure, the protein concentration at the membrane surface is abruptly increased due to the 3D to 2D transition. Consequently, protein conformational entropy is reduced to favor aggregation.294, 295 Specifically, the rate of αS primary nucleation was enhanced by three orders of magnitude when exposed to small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs, 20~100 nm in diameter) of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycerol-3-phospho-L-serine (DMPS).296

Upon adsorption onto lipid membranes, monomeric amyloid proteins adopt an α helical state, followed by a conversion to β-sheet rich oligomers and amyloid fibrils modulated by the curvature and charge of the membranes, presence of metal ions, peptide to lipid ratio, and ganglioside clusters, cholesterols and lipid rafts.299 αS assumes a fully extended α helical state coming into contact with larger vesicles, likely representative of the protein conformation in vivo.300, 301 In contrast, smaller vesicles with greater curvatures and smaller surface areas are associated with proteins in bent α helices or antiparallel helix-turn-helix conformation to maximize protein-membrane binding.293

A high peptide/lipid ratio favors protein crowding on the membrane surface to induce nucleation.302 Binding of αS (isoelectric point of 4.74)303 with membranes is elevated with increased acidic phospholipid content.304–306 αS oligomers also show propensity for the liquid disordered phase of anionic vesicles.307 The exact mechanism of αS association with lipid rafts is unclear, but is linked to the high lipid packing density of anionic head groups in the rafts. Such specific binding between αS and lipid rafts may be essential to both the normal cellular function of αS and its role in PD pathology.299

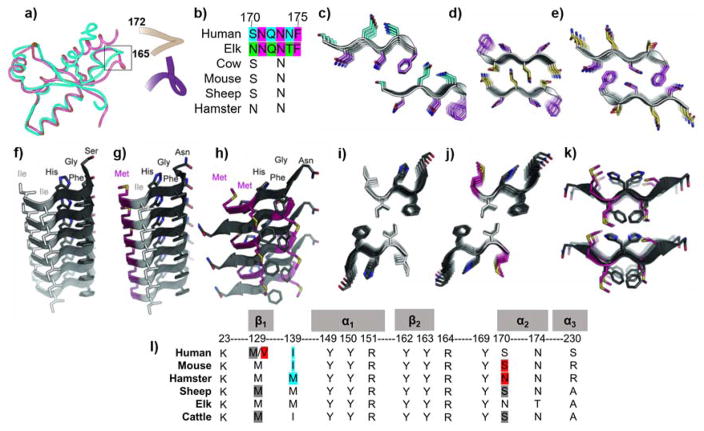

Elevated levels of metal ions have been found in the substantia nigra of PD patients.308 Addition of metal cations of Cu2+, Fe3+ or Co3+ induced secondary structure in αS and accelerated protein aggregation in vitro,265 through metal ion-mediated amyloid protein-membrane interaction. Although Ca2+ (of ~300 μM) in the ER serves to facilitate protein folding, addition of Ca2+ and other heavy meal ions to monomeric αS rapidly produced annular oligomers,309 while divalent metal ions also enabled the clustering of αS on the surfaces of anionic 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho(1′-rac-glycerol)/phosphatidylcholine bilayers.306 It is possible that metal cations enabled the interaction of the likely charged C-terminus of αS and membranes through charge neutralization. Such strong metal-hosting capacity of amyloid proteins has been utilized in entirely different contexts from amyloidogenesis, such as purification of wastewater and in vitro iron fortification using functional β-lactolglobulin amyloids.310–312