Abstract

Background

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces the risk of TB among people living with HIV (PLWH). With ART scale-up in sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade, incidence of TB among PLWH engaged in HIV care is predicted to decline.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of routine clinical data from 168,330 PLWH receiving care at 35 facilities in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda during 2003–2012, participating in the East African region of the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA). Temporal trends in facility-based annual TB incidence rates (per 100,000 person-years (PYs)) among PLWH and country-specific standardized TB incidence ratios (SIRs) using annual population-level TB incidence data from the World Health Organization (WHO) were computed between 2007 and 2012. We examined patient- and facility-level factors associated with incident TB using multivariable Cox models.

Results

Overall, TB incidence rates among PLWH in care declined 5-fold between 2007 and 2012 from 5,960 to 985 per 100,000 PYs [p=0.0003] (Kenya: 7,552 to 1,115 [p=0.0007]; Tanzania: 7,153 to 635 [p=0.0025]; Uganda: 3,204 to 242 [p=0.018]). SIRs significantly decreased in the three countries, indicating a narrowing gap between incidence rates among PLWH and the general population. We observed lower hazards of incident TB among PLWH on ART and/or IPT and receiving care in facilities offering TB treatment on-site.

Conclusions

Annual TB incidence rates among PLWH significantly declined during ART scale-up but remained higher than the general population. Increasing access to ART and IPT and co-location of HIV and TB treatment may further reduce TB incidence among PLWH.

Keywords: TB incidence rates, Tuberculosis, TB/HIV, HIV, ART, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is the most common opportunistic infection among persons living with HIV (PLWH) and the leading cause of death in PLWH globally1. Between 1990 and 2000, HIV-associated TB drove increasing TB incidence trends in sub-Saharan Africa2, while rates stabilized or declined elsewhere3. In 2000, Jones et al. found that antiretroviral therapy (ART) was highly effective in reducing the risk of TB disease among a US-based cohort4. Subsequently, eight PLWH cohorts from diverse settings, including sub-Saharan Africa4–13, reported an average decline of 67% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 61–73%) in the risk of TB associated with ART over an average two year follow–up14,15. Meanwhile, ART coverage among all PLWH increased rapidly in sub-Saharan Africa since 2005 from single digits to 39% in 201416. Mathematical models have since shown declining HIV-associated TB over the past decade in sub-Saharan Africa17,18. These models included expanding ART coverage along with TB notification rates and baseline CD4 counts of PLWH as parameters. A few empirical studies have found declining case notification rates coinciding with ART scale up19,20. In addition, a recent study in Kenya found that during 2007–2012, estimated tuberculosis incidence declined by 28–44% among PLWH–including those who are engaged and not engaged in HIV care–concurrent with an increase in antiretroviral therapy uptake21. To date, no study has examined temporal trends in facility-based annual TB incidence rates among PLWH engaged in HIV care over a period of rapid ART scale up in sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, while a number of patient factors associated with incident TB disease among PLWH have been described4,6–8,22–26, there is little data on the potential influence of facility-level factors, such as type and location of the facility, availability and co-location of integrated TB/HIV services.

We utilized clinical data collected from 2003 to 2012 within the East African region of the International epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) to determine temporal trends in facility-based annual TB incidence rates among PLWH in HIV care at predominantly public health facilities serving urban and semi-urban population and to assess patient- and facility-level factors associated with incident TB.

Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective study utilizing data collected during routine clinical encounters from the East Africa IeDEA Cohort. The study period varied by country: January 2003 to December 2012 in Kenya and Uganda and January 2006 to December 2012 in Tanzania. This study was approved by the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital/Moi University Institutional Research and Ethics Committee, Mbarara University of Science & Technology Institutional Review Committee (MUST-IRC), Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), St. Raphael of St. Francis Hospital Institutional Review Ethics Committee, Makerere University School Medicine Research & Ethics Committee (MUSOMREC), The United Republic of Tanzania Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute for Medical Research, Kenya Medical Research Institute/National Ethics Review Committee (ERC). Written consent was waived by the IRBs due to the transmission of only de-identified data disseminated from the Regional Data Coordinating Center (RDC).

Study Setting

Eight programs representing 35 health facilities contributed data for analysis27.

Study Population

PLWH who were ≥18 years of age, ART-naïve, and TB disease free at HIV care enrollment were included. PLWH with TB at enrollment or who initiated anti-TB treatment within 60 days of enrollment (25,300 patients) were excluded as possible prevalent cases.

Data Collection and Management

Data were collected using clinic-specific standard data collection forms and entered into patient-level databases locally. Prospective data quality controls to optimize accuracy and reduce missing data were incorporated into all data collection systems using methods for reconciliation of errors and retrieval of missing information from clinicians and primary records. At every site, periodic audits were conducted by the East African IeDEA Regional Data Center (RDC) (Indiana University and Moi University) to identify errors, review data collection/ entry procedures and investigate missing data. Data from all sites were harmonized at the RDC. Facility-level data were collected using an IeDEA facility survey28.

Analysis

The outcome of interest was the first incident TB diagnosis, defined as first documentation of anti-tuberculosis medications within the patient record at least 2 months after enrollment into HIV care. Subsequent TB episodes were not included. TB diagnosis and subsequent initiation of treatment was largely based on clinical evaluation and smear microscopy during the period of this analysis.

Annual crude TB incidence rates (per 100,000 person years (PY)) were estimated stratified by ART status (pre-ART or on ART), and age group (18–19, 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, 50+ years of age). We restricted the period of the trend analysis to 2007–2012 as estimates for the years prior to 2007 were unstable due to limited person time on follow-up. Time-updated ART status was used to account for different levels of risk during the pre-ART and ART phase. The annual crude TB incidence rates were divided by annual TB incidence rates (per 100,000 population per year) for the general population estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO), to derive country-specific standardized TB incidence ratios (SIRs) for PLWH enrolled in HIV care at study sites29. SIRs represent the relative likelihood that HIV patients in care would develop TB disease as compared to the general population in the same country in a given year. To assess temporal trends in crude incidence rates and SIRs, linear regression was used30.

We fitted adjusted Cox proportional-hazard models to 138,394 (82% of 168,330) PLWH with available data on all patient and facility variables, including imputed CD4 cell count and WHO stage to examine the temporal trend in TB incidence after adjusting for patient- and facility-level factors. Patient-level factors considered in adjusted analyses were age at enrollment, sex, enrollment year, WHO stage and CD4 cell count at enrollment, time-dependent ART use, history of TB disease prior to enrollment and use of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) at any time during HIV care. Facility-level factors included type of population served (rural, semi-urban, urban), facility type (public, private/other), availability of anti-TB treatment on-site, availability of routine TB screening based on a symptom check list, and availability of IPT at the HIV clinic. We also assessed criteria for Cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) eligibility against 2006 WHO guidelines31 (eligibility criteria of CD4 cell counts either <350 or <500 cells/µL as fully consistent; CD4 counts <200 cells/µL or WHO stage III or IV as partially consistent).

Age and year of enrollment were treated as continuous variables. All other factors were treated as categorical variables. Records were censored at the date of the event or the last clinic visit for individuals identified as dead, lost to follow-up (LTFU), or transferred out. LTFU was defined as no visits for 6 months (for patients on ART) and 12 months (for pre-ART patients) without documentation of death or transfer. Patient- and facility-level factors that were significant at α=0.20 level in unadjusted analyses were included into the adjusted model. In the adjusted model, statistical significance was determined at the α=0.05 level. History of TB disease prior to enrollment was not available for the Tanzanian clinics and thus excluded from the adjusted model. We used robust standard errors to account for within-individual correlation resulting from treating ART as a time-dependent variable.

To examine the robustness of findings, we compared results including PLWH with imputed values for CD4 cell count and WHO stage at enrollment with results excluding them. Additionally, we ran country-specific models to examine whether observed associations in the multi-country model was driven by a single country. Statistical analyses were conducted in Stata version 10.0 (College station, TX).

Multiple imputation techniques were used to impute CD4 cell count for 23% and WHO stage for 12% of patients with missing data at enrollment based on a country-specific algorithm adapted from Yiannoutsos and colleagues32 using WHO stage at enrollment if available to impute CD4 cell count and CD4 cell count if available to impute WHO stage as well as age group, sex, and time from enrollment to ART start for ART patients for both measures.

Results

Patient and clinic characteristics

Overall, 168,330 adult PLWH enrolled in HIV care between 2003 and 2012 with a median follow-up time of 44.0 months (interquartile range (IQR): 20.3–67.9) (Table 1). The majority was female (69%) with a median age of 34 (IQR: 28–42). Median CD4 cell count at enrollment was 283 cell/µL (IQR: 135–457 cells/µL) with little variability across countries. Approximately one-third of patients were enrolled with a WHO stage of III/IV disease. The proportion of patients with documented history of TB at enrollment ranged from 0.3% in Uganda to 5% in Kenya. IPT use was significantly higher in Kenya (19%) when compared to Tanzania and Uganda (<1%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients enrolling in HIV care in 35 facilities participating in IeDEA-East Africa, 2003–2012

| Kenya | Tanzania | Uganda | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 111556 | 13392 | 43382 | 168330 |

| Age at enrollment | ||||

| Median, IQR | 34.5 (28.2–42.2) | 35.3 (29.5–42.5) | 33.3 (38.0–40.1) | 34.3 (28.2–41.5) |

| Missing | 355 | 2 | 22 | 379 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 77953 (69.9) | 9635 (71.9) | 28303 (65.2) | 115891 (68.6) |

| Male | 33603 (30.1) | 3757 (28.1) | 15079 (34.8) | 52439 (31.2) |

| Enrollment year | ||||

| 2003 | 1256 (1.1) | NA | 2693 (6.2) | 3949 (2.3) |

| 2004 | 4574 (4.1) | NA | 1. 5322 (12.3) | 2. 9896 (5.9) |

| 2005 | 9488 (8.5) | NA | 3. 8038 (18.5) | 4. 17526 (10.4) |

| 2006 | 14297 (12.8) | 1949 (14.6) | 5. 5795 (13.4) | 6. 22041 (13.1) |

| 2007 | 16358 (14.7) | 2696 (20.1) | 7. 3981 (9.2) | 8. 23035 (13.7) |

| 2008 | 14386 (12.9) | 2810 (21.0) | 9. 4535 (10.5) | 10. 21731 (12.9) |

| 2009 | 16366 (14.7) | 1864 (13.9) | 11. 4195 (9.7) | 12. 22425 (13.3) |

| 2010 | 15233 (13.7) | 1706 (12.7) | 13. 5106 (11.8) | 14. 22045 (13.1) |

| 2011 | 13465 (12.1) | 1482 (11.1) | 15. 2918 (6.7) | 16. 17865 (10.6) |

| 2012 | 6133 (5.5) | 885 (6.6) | 17. 799 (1.8) | 18. 7817 (4.6) |

| Follow-up time (months) | 19. | 20. | ||

| Median, IQR | 42.1 (20.3–67.2) | 44.6 (21.9–59.9) | 21. 50 (19.9–71.3) | 22. 44 (20.3–67.9) |

| Pre-ART | 31.2 (12.0–56.8) | 29.3 (11.1–49.9) | 37.2 (12.0–62.4) | 32.6 (12.0–58.6) |

| ART | 46.7 (25.0–69.6) | 48.8 (29.5–62.1) | 56 (27.2–74.5) | 49 (25.7–70.3) |

| CD4+ cells/µL at enrollment | ||||

| Median, IQR | 280 (137–457) | 261 (115–410) | 297 (138–475) | 283 (135–457) |

| 0–99 | 20437 (18.3) | 2880 (21.5) | 7541 (17.4) | 30858 (18.3) |

| 100–199 | 21068 (18.9) | 2652 (19.8) | 7269 (16.8) | 30989 (18.4) |

| 200–350 | 25758 (23.1) | 2859 (21.4) | 10051 (23.2) | 38668 (23.0) |

| 351–500 | 22884 (20.5) | 3186 (23.8) | 9800 (22.6) | 35870 (21.3) |

| > 500 | 21297 (19.1) | 1809 (13.5) | 8716 (20.1) | 31822 (18.9) |

| Missing | 112 | 6 | 5 | 123 |

| WHO stage at enrollment | ||||

| Stage 1 | 54836 (49.2) | 3869 (28.9) | 11511 (26.5) | 70216 (41.7) |

| Stage 2 | 23925 (21.5) | 4854 (36.2) | 16342 (37.7) | 45121 (26.8) |

| Stage 3 | 28523 (25.6) | 3340 (24.9) | 10886 (25.1) | 42749 (25.4) |

| Stage 4 | 4192 (3.8) | 1329 (9.9) | 4642 (10.7) | 10163 (6.0) |

| Missing | 80 | 0 (0.0) | 1 | 81 |

| Use of ART | ||||

| Yes | 66612 (59.7) | 6450 (48.2) | 19390 (44.7) | 92452 (54.9) |

| No | 44944 (40.3) | 6942 (51.8) | 23992 (55.3) | 75878 (45.1) |

| 2003 | 419 (33.4) | - | 436 (16.2) | 855 (21.7) |

| 2004 | 2363 (42.6) | - | 1403 (20.1) | 3766 (30.1) |

| 2005 | 6976 (50.0) | - | 4432 (35.3) | 11408 (43.0) |

| 2006 | 12790 (51.1) | 786 (40.3) | 5468 (39.0) | 19044 (46.4) |

| 2007 | 17943 (50.3) | 1767 (46.5) | 7084 (49.7) | 26794 (49.9) |

| 2008 | 22629 (53.6) | 2511 (49.2) | 8616 (54.3) | 33756 (53.4) |

| 2009 | 29710 (59.6) | 2848 (57.3) | 9845 (58.2) | 42403 (59.1) |

| 2010 | 36326 (65.6) | 3082 (62.8) | 11250 (59.5) | 50658 (63.9) |

| 2011 | 41759 (72.0) | 3106 (64.6) | 12117 (67.0) | 56982 (70.4) |

| 2012 | 38979 (78.1) | 3102 (72.6) | 5740 (75.4) | 47821 (77.4) |

| Use of Isoniazid preventive therapy | ||||

| Yes | 21436 (19.2) | 52 (0.4) | 216 (0.5) | 21704 (12.9) |

| No | 90120 (80.8) | 12740 (99.6) | 20278 (99.5) | 123138 (87.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 600 | 22888 | 23488 |

| History of TB | ||||

| Yes | 5308 (4.8) | NA | 118 (0.3) | 5426 (3.2) |

| No | 106248 (95.2) | NA | 6281 (99.7) | 112529 (96.8) |

| Missing | 0 | 13392 | 36983 | 50375 |

The proportion of PLWH initiating ART in any given year increased from 22% in 2003 to 77% in 2012. In Kenya, 60% of enrolled patients had initiated ART during the observation period compared to 48% in Tanzania and 45% in Uganda. 57% of patients were LTFU while in pre-ART care and 26% following ART initiation; 6% were known to have died.

Patients received care in 35 health facilities (27 in Kenya, three in Tanzania, five in Uganda). Most facilities served urban and semi-urban populations (Table 2). 89% were public-sector facilities, 63% offered anti-TB treatment on-site, and 91% reported routine symptom-based TB screening. On-site IPT availability was variable across countries; Kenya reported availability in 70%, Uganda in 20%, and Tanzania in no facilities. Consistency with WHO CPT guidelines was reported at 33%, 67%, and 60% of the facilities in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, respectively.

Table 2.

Clinic characteristics of IeDEA-East Africa health facilities, 2009

| Kenya | Tanzania | Uganda | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of health facilities | 27 | 3 | 5 | 35 |

| Population served by facility | ||||

| Urban only | 8 (30) | 2 (67) | 4 (80) | 14 (40) |

| Rural only | 5 (19) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (14) |

| Semi-urban only | 10 (37) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (29) |

| Urban and semi-urban | 4 (15) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 5 (14) |

| Rural and semi-urban | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 1 (3) |

| Facility type | ||||

| Public | 24 (89) | 3 (100) | 4 (80) | 31 (89) |

| Private/other | 3 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 4 (11) |

| Availability of TB treatment within facility | ||||

| Yes | 18 (67) | 1 (33) | 3 (60) | 22 (63) |

| No | 9 (33) | 2 (67) | 2 (40) | 13 (37) |

| Routine TB screening at the HIV clinic | ||||

| Yes | 25 (93) | 2 (67) | 5 (100) | 32 (91) |

| No | 2 (7) | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) |

| Availability of Isoniazid preventive therapy at the HIV clinic | ||||

| Yes | 19 (70) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) | 20 (57) |

| No | 8 (30) | 3 (100) | 4 (80) | 15 (43) |

| Consistency with WHO guidelines forCotrimoxazole among PLWH | ||||

| Fully consistent | 9 (33) | 2 (67) | 3 (60) | 14 (40) |

| Partially consistent | 18 (67) | 1 (33) | 2 (40) | 21 (60) |

Overall and temporal trends in TB incidence

Between 2003 and 2012, 12,967 incident cases of TB were identified, 5,471 during pre-ART and 7,496 during ART period (Table 3).The overall 10-year crude TB incidence rate was 3,986 per 100,000 PY. Higher rates were reported in PLWH from Kenyan and Ugandan sites (4,056 and 4,138 per 100,000 PY, respectively) compared to Tanzania (2,321 per 100,000 PY). In Uganda, TB incidence rates were highest among patients 18–19 years old and steadily declined with age. Across the three countries, the lowest TB incidence rates were found among the 50+ age group.

Table 3.

Crude TB incidence rates and standardized incidence ratios among HIV positive individuals enrolling in HIV care in IeDEA-East Africa health facilities, January 2003–December 2012

| Kenya | Tanzania | Uganda | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 111556 | 13392 | 43382 | 168330 |

| Number of incident TB cases | ||||

| All | 9149 | 396 | 3422 | 12967 |

| Pre-ART | 3430 | 136 | 1905 | 5471 |

| ART | 5719 | 260 | 1517 | 7496 |

| Person months of follow up | ||||

| All | 225554 | 17064 | 82690 | 325308 |

| Pre-ART | 84218 | 5957 | 37248 | 127424 |

| ART | 141335 | 11107 | 45442 | 197883 |

| TB incidence (per 100,000 pys) | ||||

| All | 4056 | 2321 | 4138 | 3986 |

| ART status | ||||

| Pre-ART | 4073 | 2283 | 5114 | 4294 |

| ART | 4046 | 2341 | 3338 | 3788 |

| Age group | ||||

| 18–19 | 4089 | 0 | 5658 | 4285 |

| 20–29 | 4167 | 2124 | 4514 | 4166 |

| 30–39 | 4178 | 2193 | 4372 | 4118 |

| 40–49 | 3865 | 2396 | 3574 | 3703 |

| 50+ | 3824 | 2010 | 3213 | 3585 |

| Calendar yeara | ||||

| 2003 | 46568 | - | 27332 | 36666 |

| 2004 | 20686 | - | 7721 | 12601 |

| 2005 | 13708 | - | 25820 | 19787 |

| 2006 | 9263 | 8711 | 10775 | 9888 |

|

| ||||

| 2007 | 7552 | 7153 | 3204 | 5960 |

| 2008 | 5242 | 4878 | 3041 | 4604 |

| 2009 | 5124 | 2749 | 3234 | 4475 |

| 2010 | 3758 | 2090 | 2407 | 3332 |

| 2011 | 2950 | 1348 | 1208 | 2367 |

| 2012 | 1115 | 635 | 242 | 981 |

| Standardized TB incidence ratioab | ||||

| 2003 | 133.4 | - | 78.1 | - |

| 2004 | 57.9 | - | 23.7 | - |

| 2005 | 38.2 | - | 84.9 | - |

| 2006 | 26.1 | 43.6 | 38.1 | - |

|

| ||||

| 2007 | 21.8 | 53.4 | 12.2 | - |

| 2008 | 15.8 | 28.9 | 12.5 | - |

| 2009 | 16.4 | 17.8 | 14.3 | - |

| 2010 | 12.6 | 13.2 | 11.5 | - |

| 2011 | 10.2 | 8.4 | 5.3 | - |

| 2012 | 4.1 | 3.1 | 1.4 | - |

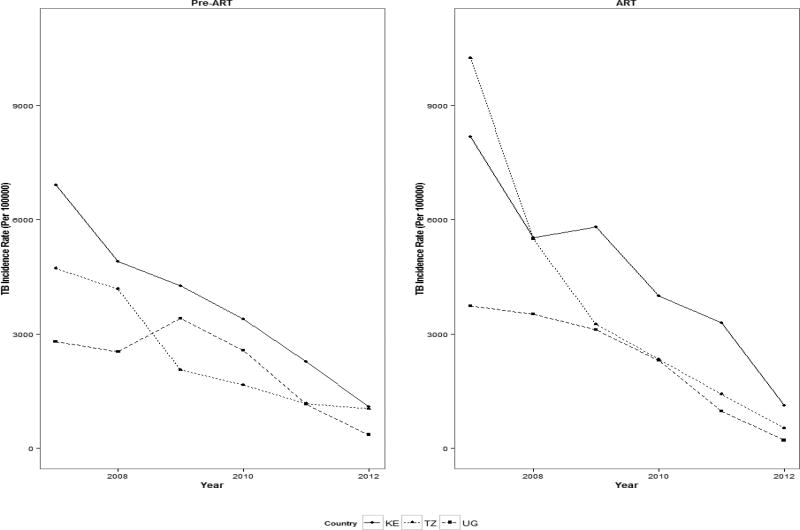

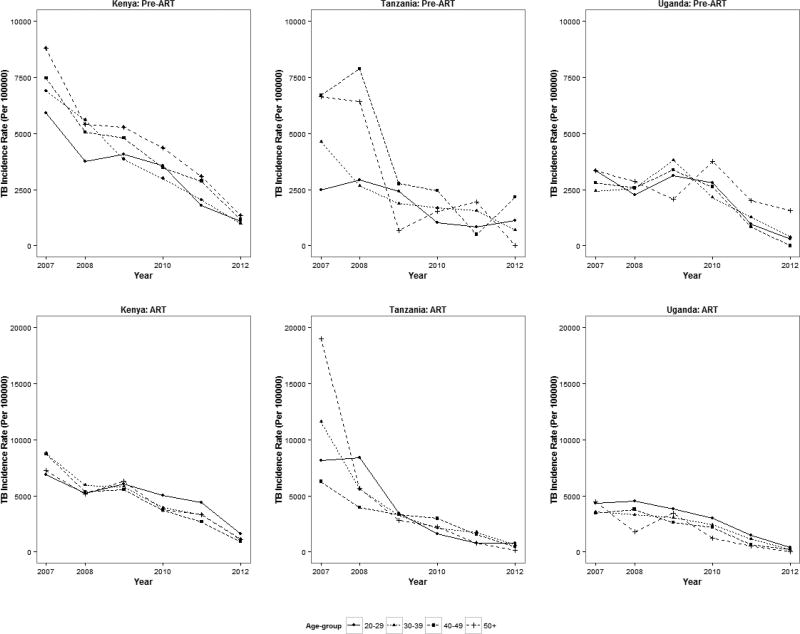

Crude TB incidence rates declined from 5,960 to 981 per 100,000 PY between 2007 and 2012 (coef.=−1,889; p=0.0003) (Table 3). The reduction in incidence was seen in all three countries (Kenya: from 7,552 to 1,115 [coef.= −2,067; p=0.0007]; Tanzania: 7,153 to 635 [coef.= −1,253; p=0.0025]; Uganda: 3,204 to 242 [coef.= −2,017; p=0.018]) (Figure 1, Table 3). The declining trends were evident across pre-ART (coef.= −1,487; p=0.0002) and ART patients (coef.= −3,290; p=0.0004) as well as across all age groups, except the 18–19 age group for Uganda (Figure2).

Figure 1.

Trends in crude TB incidence rates among HIV-positive individuals enrolling in HIV care in 35 facilities participating in IeDEA-East Africa, January 2007-December 2012*

Figure 2.

Trends in crude TB incidence rates among HIV-positive individuals enrolling in HIV care in 35 facilities participating in IeDEA-East Africa, by age group and by ART status, January 2007-December 2012*

TB incidence among PLWH compared to the general population

Standardized TB incidence ratios (SIR) showed similar trends from 2007 to 2012 (Kenya: 21.8 to 4.1 [p=0.0019]; Tanzania: 53.4 to 3.1 [p=0.0022]; Uganda: 12.2 to 1.4 [p=0.0404]), indicating substantial decreases in TB incidence among PLWH engaged in HIV care relative to the general population (Table 3). Despite this decrease over the study period, enrolled PLWH continued to have a 1.4–4.1 times higher TB incidence than the general population.

Adjusted analysis of temporal trends in TB incidence

In the adjusted analysis, more recent year was associated with a lower hazard of TB disease. Other lower hazards of TB were increasing age, enrollment CD4 cell count between 100 – 199 cells/µL and > 350 cells/µL (vs. <100 cells µL), use of ART and IPT and receiving care at facilities with both HIV and anti-TB treatment available on-site. Factors associated with higher hazards of TB included male gender and WHO stage II, III and IV (vs. WHO stage I) at enrollment; receiving care in public health facilities (vs. private facilities), facilities not exclusively serving an urban population (vs. urban population only), and facilities with routine symptom-based TB screening (Table 4).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for patient and facility-level factors associated with incident TB among patients enrolling in HIV care in IeDEA-East Africa health facilities, 2003–2012 (n=138,394)

| HR | 95% CI | P-value | aHRb | 95% CI | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at enrollment | 1.004 | (1.002–1.006) | <0.001 | 0.996 | (0.994–0.998) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 1.447 | (1.394–1.504) | <0.001 | 1.314 | (1.263–1.368) | <0.001 | |

| Female | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Enrollment Year | 0.924 | (0.916–0.933) | <0.001 | 0.948 | (0.938–0.958) | <0.001 | |

| CD4+ cells/µL at enrollment | |||||||

| Patient-level factors | 0–99 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| 100–199 | 0.824 | (0.781–0.869) | <0.001 | 0.911 | (0.862–0.963) | 0.001 | |

| 200–350 | 0.806 | (0.765–0.849) | <0.001 | 0.981 | (0.925–1.040) | 0.515 | |

| 351–500 | 0.662 | (0.625–0.701) | <0.001 | 0.837 | (0.779–0.899) | <0.001 | |

| 500+ | 0.440 | (0.411–0.471) | <0.001 | 0.594 | (0.547–0.645) | <0.001 | |

| WHO stage at enrollment | |||||||

| Stage 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Stage 2 | 1.495 | (1.425–1.568) | <0.001 | 1.412 | (1.343–1.484) | <0.001 | |

| Stage 3 | 2.348 | (2.245–2.456) | <0.001 | 2.097 | (1.992–2.207) | <0.001 | |

| Stage 4 | 2.598 | (2.403–2.809) | <0.001 | 2.240 | (2.054–2.442) | <0.001 | |

| Use of ART | |||||||

| Yes | 1.168 | (1.123–1.214) | <0.001 | 0.843 | (0.798–0.891) | <0.001 | |

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Use of Isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) | |||||||

| Yes | 0.716 | (0.684–0.750) | <0.001 | 0.767 | (0.728–0.809) | <0.001 | |

| No | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| History of TBa | 1.622 | (1.504–1.750) | <0.001 | ||||

| Facility type | |||||||

| Public clinic | 1.502 | (1.312–1.719) | <0.001 | 1.392 | (1.196–1.619) | <0.001 | |

| Private clinic | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Population served | |||||||

| Facility-level factors | Urban | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Urban and semi-urban | 0.822 | (0.791–0.854) | <0.001 | 0.956 | (0.913–0.999) | 0.049 | |

| Rural and semi-urban | 0.719 | (0.663–0.780) | <0.001 | 0.788 | (0.723–0.859) | 0.000 | |

| Availability of TB treatment within facility | 0.808 | (0.778–0.839) | <0.001 | 0.932 | (0.878–0.989) | 0.021 | |

| Routine TB screening at the HIV clinic | 1.364 | (1.119–1.663) | 0.002 | 1.260 | (1.026–1.542) | 0.027 | |

| Availability of IPT at the HIV clinic | 0.889 | (0.853–0.927) | <0.001 | 1.042 | (0.868–1.243) | 0.678 | |

| Consistency with WHO guidelines for Cotrimoxazole among PLWH | 1.116 | (1.071–1.162) | <0.001 | 0.894 | (0.781–1.024) | 0.106 | |

| Country | Kenya | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Tanzania | 0.508 | (0.458–0.564) | <0.001 | 0.480 | (0.407–0.565) | 0.000 | |

| Uganda | 1.501 | (1.435–1.569) | <0.001 | 1.176 | (1.030–1.343) | 0.016 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; aHR, adjusted hazard ratio;

Model includes only Kenya and Uganda, as Tanzania did not report this variable.

In sensitivity analyses excluding observations with imputed values for CD4 cell count and WHO stage, we found higher TB incidence among those with missing CD4 cell count and/or WHO stage values. Those with missing values had an overall incidence rate of 4,477 per 100,000 pys compared to those without missing values that had an overall incidence rate of 3,868 per 100,000 pys. This is likely due to the fact that they were less likely to be on ART (35.9% vs. 62.5%) and on IPT (7.9% vs. 17.7%). Model results excluding imputed values for CD4 cell count and WHO stage, however, yielded consistent results with those using imputed data with minor variation in point estimates and p-values, which indicated no significantly differences in factors associated with incident TB between the two groups. Additionally, we ran country-specific models and found that more recent enrollment year was associated with lower hazard ratio for TB in all models. While we found broad consistency in the direction of association with patient and facility level factors with incident TB, we found important differences in a few variables. At the individual level, IPT use was significantly associated with decreased risk of TB in Kenya, was not associated in Tanzania and associated with increased risk in Uganda. Paradoxically, at the facility level, availability of IPT at the HIV clinic was significantly associated with a higher risk of TB in Kenya, while the opposite was true in Uganda. In Tanzania the variable dropped out of the model due to collinearity. Finally, public clinic was associated with lower risk of incident TB in Kenya while it was associated with higher risk of incident TB in Uganda.

Discussion

Among 168,330 PLWH receiving HIV care at 35 clinics in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, we found a 5-fold decline in TB disease incidence from 2007 to 2012 the period of ART scale-up in which ART coverage among all PLWH increased from 14%, 9%, 11% to 46%, 29%, 32% in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, respectively33. The significant declining trend, moreover, was still present after adjustment for confounding in the multivariate model. The magnitude of the decline was greater than modeling estimates of HIV-associated TB incidence17,18. The WHO Global TB Report of 2014, for example, found 66%, 110% and 82% decline in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, respectively, between 2004 and 201317. These estimates, however, are for all PLWH regardless of whether or not they are engaged in HIV care. A study in peri-urban township in South Africa, on the other hand found 1.7 fold decrease in case notification among PLWH on ART between 2004 and 2008—a larger decline than modeling studies19. Accounting for the shorter observation period of that study compared to our study, the magnitude of decline observed in our facilities was still higher.

Findings from this large multi-country study demonstrate significant decreases in annual TB incidence coinciding with decade-long scale-up of ART services, mirroring studies of single cohorts examining the ART effectiveness in reducing TB incidence4–13. We found declining TB incidence in pre-ART as well as ART patients. The decline in pre-ART care could partially be explained by reduced transmission of TB both in the community and in the facility as a result of ART scale up, despite predictions of low effect34. IPT scale-up among PLWH may also contribute17. We found a 33% protective effect of IPT against incident TB. Finally, the decline may in part be an artifact of the very high incidence of TB among PLWH engaged in care in Kenya in 2004 and Uganda in 2005. These rates may be a function of either the early effects of HIV epidemic on increased progression to TB disease in those infected or of active case finding in HIV centers or both. A similar phenomenon was observed in Peru during its initial years of active TB control35.

We also found that the SIRs decreased significantly, suggesting that the gap between TB incidence among PLWH in care and the general population narrowed over the study period. Despite previous recognition that general economic development with improved nutrition decreases TB incidence36,37, the substantial decline in SIRs suggest that scale-up of HIV care contributed additional benefit in reduction of TB disease in PLWH in care as past studies have shown19,21. Yuen, et al., for example found estimated TB incidence rates in Kenya among HIV-negative people reduced approximately at half the rate of HIV-positive people (11%–26% vs. 28%–44% decline between 2007 and 2012)21. In our study, in spite of the greater decline in PLWH in care, TB incidence among them remained 1.4–4.1 times higher than in the general population at the end of the study period in all three countries. This finding is anticipated; ART does not return patients, particularly those with a very low CD4 count, to a pre-HIV infection immune status26,34,38.

Consistent with previous studies, use of ART and IPT were associated with a reduced incidence of TB4,6–9,13,22,24. As previously described, female gender39 as well as higher CD4 cell count and lower enrollment WHO stage were associated with lower hazard of TB22,23. While other studies and our unadjusted models found that increasing age was associated with a higher hazard of TB13,24, once we adjusted for immunosuppression measures at enrollmentthis finding was reversed. In post-hoc analyses we found that older PLWH had longer time on ART than younger PLWH, which may explain this finding as longer time on ART have been shown to reduce risk of TB6.

We also found important facility-level factors associated with incident TB. PLWH receiving care at public-sector facilities and in facilities serving only urban populations were more likely to have incident TB. The urban setting has been linked to higher rates of incident TB in prior studies, plausibly mediated by high population density and crowded living conditions36. PLWH receiving care at health facilities providing anti-TB treatment on-site were less likely to have incident TB. Integration of HIV and TB programs has been associated with high cure and treatment completion rates40,41. Our study has found it may also reduce incident TB among PLWH engaged in care, presumably by reducing TB transmission in the community by reducing treatment delays. While IPT was significantly associated with reduced risk of incident TB, availability of IPT at the HIV clinic was not associated with reduction in incident TB. This may be explained by availability of IPT not always translating to patients actually receiving the treatment, a probability in Kenya where 80% of health facilities reported IPT availability but only 20% of patients had documentation that they received it.

Our study has some limitations. We had a substantial amount of missing data, most notably enrollment CD4 cell count and WHO stage. We used multiple imputation techniques to address CD4 data incompleteness in our analyses. However, if these data were not missing at random, the results based on the imputed data could be biased42.

While the proportion of patients LTFU in our study was comparable to other studies43–45, attrition bias is possible if the likelihood of LTFU were associated with incident TB Nevertheless, we do not believe the significant decline in TB incidence found can be explained by greater LTFU by patients with incident TB, as rates of LTFU in our study population also declined over the study period from 58% to 19%.

Additionally, we had missing observations resulting in models for incident TB using only 82% of the total study population. However, as demographic and clinical characteristics of PLWH included in and excluded from the models were very similar to each other (data not shown), it is unlikely that model results are seriously biased.

Incident TB was defined as the first documented initiation of anti-TB treatment. Use of anti-TB treatment initiation to define incident TB lends itself to misclassification biases in both directions. Diagnostic challenges remain especially in PLWH where smear negative and extrapulmonary TB are common; some patients are not diagnosed due to these limitations and therefore not treated while other patients are “overtreated” due to clinician fear of missing TB.

SIRs standardized the TB incidence rates of PLWH engaged in HIV care to the annual TB incidence rates (per 100,000 population per year) for the general population estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO). Our study population, however, was PLWH engaged in care predominantly in public health facilities serving urban and peri-urban areas. As TB incidence is likely higher in urban areas, SIRs in this study could therefore be inflated.

Another possible limitation relates to the fact that facility-level factors were assessed in a 2009 survey and were assumed to be unchanged through the study period. It is likely that clinic practices for TB treatment within facility, routine TB screening at HIV clinic, availability of IPT at HIV clinic and consistency with WHO guidelines for CPT among PLWH changed over time so that 2009 practices may not be representative of earlier or later practices. Such misclassifications would attenuate associations between health facility-level factors and incident TB.

Additionally, it is important to note that while the majority of health facilities were public health facilities which are the backbone of the national HIV response in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda, they were not selected to be representative of the health facilities delivering HIV care in these countries. The vast majority of the health facilities (77%) and patients (66%) came from 3 regions in Kenya which represented 7% (38979/548,588) of the reported number of adults receiving ART in Kenya in 201246.

Finally, there may be important country-level differences in factors associated with incident TB that we were not able to fully explore in this analysis. Our sensitivity analyses, for example, showed that IPT use at individual level was associated with higher risk of TB in Uganda. We believe, however, that this is an artifact of poor data quality for that variable in Uganda (53% missing).

Our study also has important strengths. With data on nearly 170,000 PLWH with 13,000 incident TB cases from 35 HIV care clinics in three countries with heterogeneous HIV epidemics, this study during early, rapid ART scale up is the largest assessment of HIV-related TB incidence in this region. Six years of observation for the temporal trend analysis allowed for examination of TB incidence over a critical period of scale-up of HIV treatment in East Africa. Use of data routinely collected across countries increased the generalizability of study findings. Finally, we examined health facility-level factors associated with TB incidence that have not been previously examined.

In conclusion, we found a significant decline in TB incidence among patients in HIV care in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda between 2007 and 2012 coincident with the rapid scale up of HIV treatment across the region. SIRs significantly decreased during in all three countries, indicating that the TB incident rate gap among PLWH in HIV care and that of the general population narrowed. These findings are encouraging, as efforts continue to improve access to and early initiation of ART, IPT and TB/HIV care integration. Future studies must examine this causal impact of ART scale-up on reduction of TB incidence and mortality among PLWH. Minimizing TB remains of critical importance for continued and sustained success in reduction of morbidity and mortality in East Africa.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all patients and staff at the health facilities included in this analysis and to the staff at the data centers in the IeDEA East Africa Region. These programs include: the Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare program (AMPATH), Eldoret Kenya; the Family AIDS Care and Education Service program (FACES), Kisumu, Kenya; Infectious Disease Institute (IDI), Kampala Uganda; the Masaka Regional Hospital HIV Clinic, Masaka Uganda; the Mbarara Immune Suppression Syndrome Clinic, Mbarara Uganda; three Tanzanian Ministry of Health sites (Morogoro Regional Hospital, Morogoro; Ocean Road Cancer Institute, Dar el Salaam, and Tumbi Regional Hospital, Kibaha); finally three sites in the mother to-child HIV transmission-Plus Initiative in (Nyanza Provincial Hospital, Kisumu Kenya, St. Francis / St. Raphael Hospital, Nsambya, Uganda, and Mulago Hospital, Kampala Uganda.

East Africa IeDEA Research Working Group:

Lameck Diero-AMPATH,

Elizabeth Bukusi-FACES,

Andrew Kambugu-IDI,

John Ssali-Masaka,

Mwebesa Bosco Bwana-Mbarara,

G.R. Somi-NACP

Rita Lyamuya-Morogoro,

Emanuel Lugina-ORCI,

Kapella Ngonyani-TUMBI,

Juliana Otieno-Nyanza Provincial Hospital,

Pius Okong-St. Francis / St. Raphael Hospital,

Deo Wabaire- Mulago Hospital,

East Africa IeDEA Participating Institutions

Academic Model Providing Access to Healthcare program (AMPATH), Eldoret Kenya;

the Family AIDS Care and Education Service program (FACES), Kisumu, Kenya;

Infectious Disease Institute (IDI), Kampala Uganda;

Masaka Regional Hospital HIV Clinic, Masaka Uganda;

Mbarara Immune Suppression Syndrome Clinic, Mbarara Uganda;

Morogoro Regional Hospital, Morogoro; Tanzania

Ocean Road Cancer Institute, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Tumbi Regional Hospital, Kibaha; Tanzania

Nyanza Provincial Hospital, Kisumu Kenya,

St. Francis / St. Raphael Hospital, Nsambya, Uganda,

Mulago Hospital, Kampala Uganda

The IeDEA East Africa Consortium is funded by the following institutes: the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), grant number U01AI069911-01. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.”

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None to declare

Contributor Information

Suzue Saito, ICAP at Columbia University, New York, New York, USA.

Philani Mpofu, Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Indianapolis, USA.

E. Jane Carter, Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA; School of Medicine, Moi University, Eldoret, Kenya.

Lameck Diero, Academic Model Providing Access to Health Care (AMPATH), Eldoret, Kenya.

Kara K. Wools-Kaloustian, Indiana University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Indianapolis, USA

Constantin T. Yiannoutsos, Indiana University Fairbanks School of Public Health, Department of Biostatistics, Indianapolis, USA

Beverly S. Musick, Indiana University School of Medicine, Department of Biostatistics, Indianapolis, USA

Simon Tsiouris, Current: Ridgewood Infectious Diseases, P.A., Ridgewood NJ; Previous: Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, School of Medicine and Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University Medical Center.

Geoffrey R. Somi, National AIDS Control Programme (NACP), Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania

John Ssali, Masaka Regional Referral Hospital, Masaka, Uganda.

Denis Nash, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Program at the CUNY School of Public Health, New York, New York, USA.

Batya Elul, Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University; ICAP at Columbia University, New York, New York, USA.

References

- 1.Getahun H, Gunneberg C, Granich R, Nunn P. HIV infection-associated tuberculosis: the epidemiology and the response. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010 May 15;50(Suppl 3):S201–207. doi: 10.1086/651492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corbett EL, Marston B, Churchyard GJ, De Cock KM. Tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities, challenges, and change in the era of antiretroviral treatment. Lancet. 2006 Mar 18;367(9514):926–937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Global tuberculosis control: surveillance, planning financing. 2005 http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/2005/download_centre/en/

- 4.Jones JL, Hanson DL, Dworkin MS, DeCock KM. Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIVDG. HIV-associated tuberculosis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. The Adult/Adolescent Spectrum of HIV Disease Group. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2000 Nov;4(11):1026–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawn SD, Badri M, Wood R. Tuberculosis among HIV-infected patients receiving HAART: long term incidence and risk factors in a South African cohort. Aids. 2005 Dec 2;19(18):2109–2116. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000194808.20035.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawn SD, Myer L, Edwards D, Bekker LG, Wood R. Short-term and long-term risk of tuberculosis associated with CD4 cell recovery during antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. Aids. 2009 Aug 24;23(13):1717–1725. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardi E, Antonucci G, Vanacore P, et al. Impact of combination antiretroviral therapy on the risk of tuberculosis among persons with HIV infection. Aids. 2000 Sep 8;14(13):1985–1991. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200009080-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Santoro-Lopes G, de Pinho AM, Harrison LH, Schechter M. Reduced risk of tuberculosis among Brazilian patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2002 Feb 15;34(4):543–546. doi: 10.1086/338641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golub JE, Saraceni V, Cavalcante SC, et al. The impact of antiretroviral therapy and isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence in HIV-infected patients in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Aids. 2007 Jul 11;21(11):1441–1448. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328216f441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda A, Morgan M, Jamal L, et al. Impact of antiretroviral therapy on the incidence of tuberculosis: the Brazilian experience, 1995–2001. PloS one. 2007;2(9):e826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muga R, Ferreros I, Langohr K, et al. Changes in the incidence of tuberculosis in a cohort of HIV-seroconverters before and after the introduction of HAART. Aids. 2007 Nov 30;21(18):2521–2527. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f1c933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreno S, Jarrin I, Iribarren JA, et al. Incidence and risk factors for tuberculosis in HIV-positive subjects by HAART status. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2008 Dec;12(12):1393–1400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golub JE, Pronyk P, Mohapi L, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy, HAART and tuberculosis risk in HIV-infected adults in South Africa: a prospective cohort. Aids. 2009 Mar 13;23(5):631–636. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328327964f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawn SD, Wood R, De Cock KM, Kranzer K, Lewis JJ, Churchyard GJ. Antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in the prevention of HIV-associated tuberculosis in settings with limited health-care resources. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2010 Jul;10(7):489–498. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70078-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lawn SD, Harries AD, Williams BG, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the control of HIV-associated tuberculosis. Will ART do it? The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011 May;15(5):571–581. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. The Gap Report 2014. 2014 http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

- 17.WHO. Global Tuberculosis Report. 2014:15–16. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/91355/1/9789241564656_eng.pdf.

- 18.Murray CJ, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014 Sep 13;384(9947):1005–1070. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60844-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middelkoop K, Wood R, Bekker LG. The impact of antiretroviral treatment programs on tuberculosis notification rates. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011 Dec;15(12):1714. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0545. author reply 1714–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zachariah R, Bemelmans M, Akesson A, et al. Reduced tuberculosis case notification associated with scaling up antiretroviral treatment in rural Malawi. The international journal of tuberculosis and lung disease : the official journal of the International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2011 Jul;15(7):933–937. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuen CM, Weyenga HO, Kim AA, et al. Comparison of trends in tuberculosis incidence among adults living with HIV and adults without HIV--Kenya, 1998–2012. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e99880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badri M, Wilson D, Wood R. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on incidence of tuberculosis in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet. 2002 Jun 15;359(9323):2059–2064. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08904-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antonucci G, Girardi E, Raviglione MC, Ippolito G. Risk factors for tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons. A prospective cohort study. The Gruppo Italiano di Studio Tubercolosi e AIDS (GISTA) JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995 Jul 12;274(2):143–148. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grant AD, Charalambous S, Fielding KL, et al. Effect of routine isoniazid preventive therapy on tuberculosis incidence among HIV-infected men in South Africa: a novel randomized incremental recruitment study. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005 Jun 8;293(22):2719–2725. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.22.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grimwade K, Sturm AW, Nunn AJ, Mbatha D, Zungu D, Gilks CF. Effectiveness of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis on mortality in adults with tuberculosis in rural South Africa. Aids. 2005 Jan 28;19(2):163–168. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta A, Wood R, Kaplan R, Bekker LG, Lawn SD. Tuberculosis incidence rates during 8 years of follow-up of an antiretroviral treatment cohort in South Africa: comparison with rates in the community. PloS one. 2012;7(3):e34156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger M, Ekouevi DK, Williams C, et al. Cohort Profile: the international epidemiological databases to evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) in sub-Saharan Africa. International journal of epidemiology. 2012 Oct;41(5):1256–1264. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Africa I-E. [Accessed 8/31/2014];Site Assessment Questionnaires. 2014 https://www.iedea-ea.org/joomla/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&id=74:site-assessment-questionnaires&Itemid=62&layout=default, 2014.

- 29.WHO. [Accessed 6/10/2014];Global Health Observatory Data Repository: Cases: Incidence Data by Country (all years) 2013 http://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.57040ALL?lang=en. 2014.

- 30.Parkin PBaDM. Statistical methods for registries. In: Jensen DMP OM, MacLennan R, Muir CS, Skeet RG, editors. Cancer Registration: Principles and Methods. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 1991. p. 141. [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Guidelines on co-trimoxazole prophylaxis for HIV-related infections among children, adolescents and adults: recommendations for a public health approach. 2006:19–20. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/plhiv/ctx/en/

- 32.Yiannoutsos CT, An MW, Frangakis CE, et al. Sampling-based approaches to improve estimation of mortality among patient dropouts: experience from a large PEPFAR-funded program in Western Kenya. PloS one. 2008;3(12):e3843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bank W. Antiretroviral Therapy Coverage (% of people living with HIV) 2015 http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.HIV.ARTC.ZS.

- 34.Lawn SD, Kranzer K, Wood R. Antiretroviral therapy for control of the HIV-associated tuberculosis epidemic in resource-limited settings. Clinics in chest medicine. 2009 Dec;30(4):685–699. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez PG, Watt CJ, Alarcon E, et al. The dynamics of tuberculosis in response to 10 years of intensive control effort in Peru. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2001 Aug 15;184(4):473–478. doi: 10.1086/322777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Williams BG, Dye C, Raviglione M. Drivers of tuberculosis epidemics: the role of risk factors and social determinants. Social science & medicine. 2009 Jun;68(12):2240–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lonnroth K, Williams BG, Cegielski P, Dye C. A consistent log-linear relationship between tuberculosis incidence and body mass index. International journal of epidemiology. 2010 Feb;39(1):149–155. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Rie A, Westreich D, Sanne I. Tuberculosis in patients receiving antiretroviral treatment: incidence, risk factors, and prevention strategies. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2011 Apr;56(4):349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f9fb39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lienhardt C, Bennett S, Del Prete G, et al. Investigation of environmental and host-related risk factors for tuberculosis in Africa. I. Methodological aspects of a combined design. American journal of epidemiology. 2002 Jun 1;155(11):1066–1073. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.11.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gandhi NR, Moll AP, Lalloo U, et al. Successful integration of tuberculosis and HIV treatment in rural South Africa: the Sizonq'oba study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2009 Jan 1;50(1):37–43. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818ce6c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coetzee D, Hilderbrand K, Goemaere E, Matthys F, Boelaert M. Integrating tuberculosis and HIV care in the primary care setting in South Africa. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2004 Jun;9(6):A11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison PD. Multiple Imputation for Missing Data:A cautionary tale1999. Sociology Department, University of Pennsylvania; [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larson BA, Brennan A, McNamara L, et al. Early loss to follow up after enrolment in pre-ART care at a large public clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2010 Jun;15(Suppl 1):43–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS medicine. 2007 Oct 16;4(10):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health : TM & IH. 2010 Jun;15(Suppl 1):1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. 2013 http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en_1.pdf.