Abstract

Purpose

Surface microtopography offers a promising approach for infection control. The goal of this study was to provide evidence that micropatterned surfaces significantly reduce the potential risk of medical device-associated infections.

Methodology

Micropatterned and smooth surfaces were challenged in vitro against the colonization and transference of two representative bacterial pathogens – Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. A percutaneous rat model was used to assess the effectiveness of the micropattern against device-associated S. aureus infections. After the percutaneous insertion of silicone rods into (healthy or immunocompromised) rats, their backs were inoculated with S. aureus. The bacterial burdens were determined in tissues under the rods and in the spleens.

Results

The micropatterns reduced adherence by S. aureus (92.3 and 90.5 % reduction for flat and cylindrical surfaces, respectively), while P. aeruginosa colonization was limited by 99.9 % (flat) and 95.5 % (cylindrical). The micropatterned surfaces restricted transference by 95.1 % for S. aureus and 94.9 % for P. aeruginosa, compared to smooth surfaces. Rats with micropatterned devices had substantially fewer S. aureus in subcutaneous tissues (91 %) and spleens (88 %) compared to those with smooth ones. In a follow-up study, immunocompromised rats with micropatterned devices had significantly lower bacterial burdens on devices (99.5 and 99.9 % reduction on external and internal segments, respectively), as well as in subcutaneous tissues (97.8 %) and spleens (90.7 %) compared to those with smooth devices.

Conclusion

Micropatterned surfaces exhibited significantly reduced colonization and transference in vitro, as well as lower bacterial burdens in animal models. These results indicate that introducing this micropattern onto surfaces has high potential to reduce medical device-associated infections.

Keywords: micropatterns, infections, medical devices, hospital-acquired infections

Introduction

Indwelling of medical devices is associated with high risk of infection, given the abundance of bacterial flora on human skin and the risk of contamination from other sources [1–4]. In a study at a Pakistani paediatric intensive care unit, the incidence of device-associated infections reached a staggering 2.1 % [5]. Device-associated infections may lead to device removal and replacement, thus resulting in prolonged hospital stays, excessive medical costs, and higher morbidity and mortality [6, 7]. It was estimated that in the United States alone a total of 82 000 deaths annually were caused by device-associated infections, with direct costs of $18 billion, an economic impact on a par with those of other major diseases such as breast cancer ($16.5 billion in 2010) [7]. The fact that many of the pathogens responsible for these infections are multi-drug-resistant, or even panresistant, has become particularly problematic, with few treatment options being available [8, 9].

Healthcare workers and the industry are seeking safe and effective means to prevent device-associated infections. Hospitals and regulatory agencies periodically publish evidence-based guidelines for healthcare personnel to improve practice and reduce infection risks for patients [5, 10]. For instance, hospital preventative measures for catheter-indwelling patients, such as improved care, hand hygiene and direct observation during the insertion procedure, greatly reduced infection rates [11]. The medical device industry currently relies heavily on the use of antiseptics, antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents [12–14]. Due to emerging drug resistance and declining efficacy, these compounds are often used with higher doses and in combination, e.g. chlorhexidine and silver sulfadiazine [15–17]. The efficacy of these antimicrobial agents on medical devices was controversial in various clinical trial results, with some results supporting [16, 18] use and others contradicting this [15, 19, 20]. Antimicrobial agents can be very potent against sensitive micro-organisms, but also are associated with problems such as toxicity, decreased efficacy over time and emerging resistance [21–23]. The recent emergence of numerous multi-drug-resistant (MDR) pathogens is challenging the efficacy of antibiotics and other antimicrobial chemicals against infections.

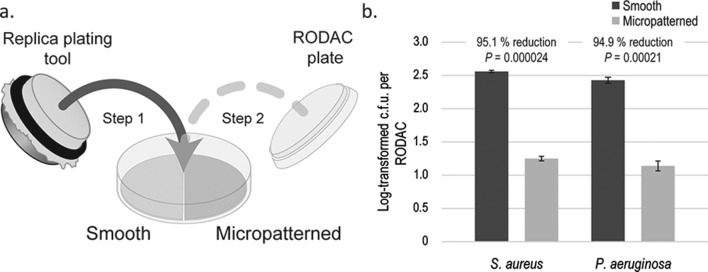

The Sharklet micropattern offers a novel approach to restricting device-associated infections safely and effectively. The Sharklet micropattern, inspired by the microtopography on shark skin, is a diamond-shaped repeating pattern of seven features (Fig. 1). Sharklet micropatterns can be incorporated onto the surfaces of a variety of medical devices during the manufacturing process. In this study, the width of the features is 2 µm, a the spacing between them is also 2 µm and the lengths range from 4 to 16 µm, in increments of 4 µm (Fig. 1). This micropattern is effective against biofouling and microbial attachment [24–26]. Percutaneous medical devices, including blood and skin access devices, surgical drains and the drivelines of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), are widely used in healthcare. Here we present new in vitro and in vivo data supporting the use of this micropattern to prevent infections associated with percutaneous medical devices.

Fig. 1.

Microscopic images of smooth and micropatterned surfaces. A confocal laser microscope (Olympus LEXT OLS4000) was used to examine the surface topography of the silicone surfaces. Each repeating micropattern comprises seven features. The micropattern is composed of features with a depth of 3 µm, a feature width of 2 µm and inter-feature spacing of 2 µm. Scale bar, 20 µm.

Methods

Strains and reagents

Two representative microbial species were selected for in vitro studies based on the following two criteria: (1) they are among the most commonly found and hazardous pathogens responsible for hospital-associated infections in percutaneous devices [27]; (2) they represent both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

S. aureus (ATCC6538) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC10197) were used in colonization assays. S. aureus (ATCC6538) and P. aeruginosa (ATCC15442) were used in transference experiments. Bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (Hardy Diagnostics) or TSB with agar (TSA) (Hardy Diagnostics), unless otherwise stated. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (HyClone, Fisher Scientific) was used during the rinsing and resuspension of bacterial pellets. Dey–Engley broth (Sigma-Aldrich) with protease K (Sigma-Aldrich) was used during sample processing in the rat study. Replicate organism detection and counting (RODAC) (BD Diagnostics) plates were used to survey bacterial transference from contaminated test surfaces.

Colonization assays

Flat or cylindrical silicone surfaces (smooth or micropatterned) were placed onto 100 mm Petri dishes and sterilized. They were then immersed in 25 ml 1×107 colony-forming units per millilitre (c.f.u. ml−1) S. aureus or P. aeruginosa. Plates were incubated statically at 37 °C for 1 h (exception: 4 h for P. aeruginosa colonization tests on rods). Unattached micro-organisms were rinsed away by three washes with 25 ml PBS and rocking at ~80 r.p.m. for 10 s on a horizontal rocker. After air drying, coupons (Φ8 mm for flat surfaces, Φ4 mm for cylindrical samples) were punched out by biopsy punches (Integra) and then each one was placed into a 15 ml conical tube containing 2 ml Dey–Engley broth. The tubes were vortexed at maximum speed for 30 s, sonicated for 2 min and vortexed again for 30 s. Bacterial resuspensions were serial-diluted up to 104-fold and 50 µl of each dilution was pipetted onto TSA plates. The plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and then the colonies were counted. For each surface, at least three independent experiments were performed, with each experiment containing three smooth and three micropatterned samples.

Transference assays

This test was performed using a similar method to that described in [28]. Briefly, half-circles of smooth and micropatterned acrylic films (FLEXcon, Spencer, MA, USA) were adhered to Petri dishes and sterilized via 15 min UV radiation. Approximately 5 (±4)×105 c.f.u. ml−1 log-phase bacteria (S. aureus or P. aeruginosa) were used for inoculation. Sterile velveteen cloths (#1) (Bel-Art Products, Wayne, NJ, USA) were soaked in this inoculum and then each was stamped by a sterile dry velveteen cloth (#2). ‘Inoculated’ cloth #2 was then used to press onto a Petri dish containing two half-circles (smooth and micropatterned, see Fig. 3a), with the purpose of inoculating the same amounts of bacteria onto two test acrylic surfaces. The effectiveness of micropatterns in reducing transference off contaminated test surfaces was then evaluated using RODAC plates. The inocula concentrations were determined by dilution plating. RODAC and inoculum plates were incubated at 37 °C overnight and then the colonies were counted. This assay was performed independently three times.

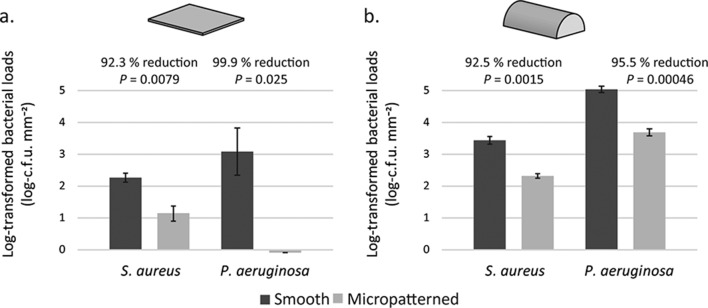

Fig. 3.

The micropattern reduces the risk of transference. (a) Smooth and micropatterned half-circles were adhered into the same Petri dish. A microbiology replica-plating tool stamped a sterile velveteen cloth onto a second contaminated velveteen cloth. Petri dishes containing test surfaces were then stamped by this replica plating device. After air drying, the plates were used to determine the c.f.u.s that were transferred from the contaminated sample surfaces. RODAC plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C and then the colonies were counted. (b) Test results from three independent experiments.

Percutaneous device rat study

This study was conducted at PreClinical Research Services, Inc. (PCRS), Ft Collins, CO, USA. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Jackson Laboratories) were used to study device-associated infections. The rats were 69 days old on the day of device implantation.

For rats receiving no chemotherapy treatment (n=48), the in-life phase began on day −3 with clinical observations and ended with final necropsies on day 3 (n=24, 12 with smooth and 12 with micropatterned devices) and day 6 (n=24, 12 with smooth and 12 with micropatterned devices). The data presented in this study were combined from the day 3 and day 6 results because (1) there is no statistical difference between the data for the two days; (2) the combination increased the statistical power substantially. In a separate study, the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide was used to compromise innate immunity (n=24), with the animals being sacrificed on day 2 (n=12 for each device type, smooth or micropatterned). Cyclophosphamide was administered twice (150 mg kg−1 on day −4 and 100 mg kg−1 on day 0) and the in-life phase ended with final necropsies on day 2 due to concerns about the rapidly declining health of the animals. The devices were surgically implanted on day 0. The technique that was used to implant a 20 mm silicone rod (micropatterned and smooth) transcutaneously into the back of each rat’s neck was modified from those described in the previously published literature [29]. Approximately 15 mm of each 20 mm device was implanted and anchored into the skin with pre-positioned suture material at the discretion of the surgeon. Carprofen (5 mg kg−1 SC) was administered for post-operative analgesia and each rat was monitored while recovering from anaesthesia. The animals were then placed in clean cages and monitored intermittently during full recovery from anaesthesia. Each rat remained singly housed after device implantation to avoid cage mates dislodging or removing each other’s device implants during normal rodent social behaviours.

On day 0, each of the device exit sites was inoculated with 50 µl sterile PBS or PBS containing 250 c.f.u. (untreated) or 1×104 c.f.u. (cyclophosphamide-treated) of S. aureus ATCC6538. After inoculation, the animals were returned to their individual cages and monitored.

On study termination (day 3 or day 6 for untreated animals, and day 2 for cyclophosphamide-treated rats), euthanasia was performed by CO2 inhalation per PCRS standard operating procedures (SOPs), and in accordance with accepted American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) guidelines [30]. Following euthanasia, a photograph was taken of each rat with the implanted device. During device explantation, care was taken not to disrupt the tissue surrounding the implanted rod. For each rat, a sample of the underlying muscle tissue that was previously in contact with the most rostral edge of the silicone rod was harvested using the previously cleaned metal forceps and scalpel blade, and placed in a pre-weighed tube for processing. Spleens were also harvested and placed into pre-weighed tubes. In the group of cyclophosphamide-treated rats, implanted rods were also harvested and cut into external and internal segments, and these were then placed into 15 ml conical tubes containing 2 ml Dey–Engley broth with 15 mg ml−1 protease K (Sigma Aldrich). All of the sample tubes underwent serial dilutions up to 103-fold. One millilitre of each dilution was plated onto a TSA plate, which was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.

Statistical analyses

We analysed the results from the colonization and transference assays from three independent experiments, each with three replicates of smooth and micropatterned samples. The bacterial c.f.u. counts were converted to log cell densities (LD), log reductions (LR) were calculated by subtracting the mean LD for the test group from the mean LD for the control group and percentage reductions (PR) were calculated by PR=1–10−LR. One-sided one-sample Student t-tests assessed the mean LR. In the rat study without cyclophosphamide treatment, the LDs were analysed using a two-way ANOVA with factors for day and treatment group. Tukey’s follow-up tests were then performed to maintain a family-wise error rate of 5 % for each of the four samples separately. In the rat study with cyclophosphamide treatment, one-sided one-sample Student t-tests were performed on the LRs.

Results

Micropatterned surfaces restrict bacterial colonization on flat and cylindrical surfaces

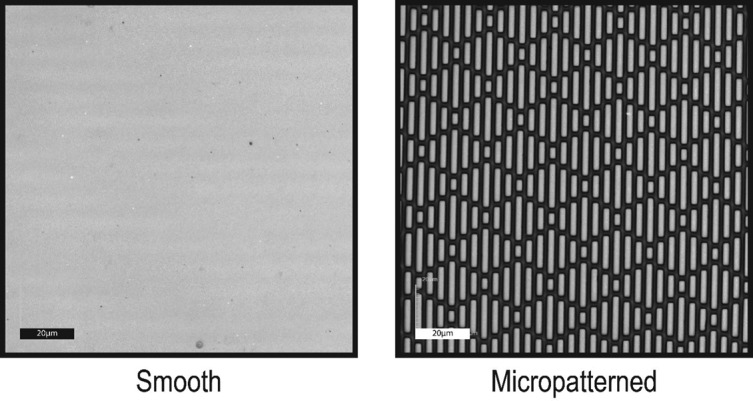

Inhibition of microbial colonization by the micropattern was evaluated in vitro in two geometries – flat and cylindrical, mimicking different device shapes. Compared to the smooth control, flat micropatterned surfaces substantially reduced the colonization of the tested micro-organisms. Specifically there was a 92.3 % reduction for S. aureus (P<0.01, n=3) and a 99.9 % reduction for P. aeruginosa (P<0.05, n=3) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

The micropattern limits surface contamination by microbial pathogens. Flat (a) or cylindrical (b) silicone surfaces (smooth in black and micropatterned in grey) were immersed in micro-organisms (S. aureus and P. aeruginosa), followed by the rinsing away of unattached cells. Attached cells were then eluted off silicone surfaces and enumerated by dilution plating. Colony-forming units (c.f.u.) were counted, log-transformed and normalized by surface areas as the y-axis.

Smooth and micropatterned silicone rods, mimicking the external surface of tubes, were also tested to evaluate the impact of curved geometry on microbial colonization. The colonization of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa was significantly (P<0.05, n=3) reduced, by 90.5 and 95.5 %, respectively, on micropatterned compared to smooth rod surfaces (Fig. 2b).

Micropatterned surfaces reduce the transference of bacteria

To further examine the mechanism of device-associated infections, micropatterned and smooth surfaces were contaminated with bacteria and assessed for bacterial transference off contaminated surfaces onto RODAC sampling plates. Micropatterned surfaces significantly restricted S. aureus and P. aeruginosa transference, by 95.1 % (P<0.001, n=3) and 94.9 % (P<0.001, n=3), respectively, compared to smooth surfaces (Fig. 3).

The micropattern limits in vivo bacterial burdens

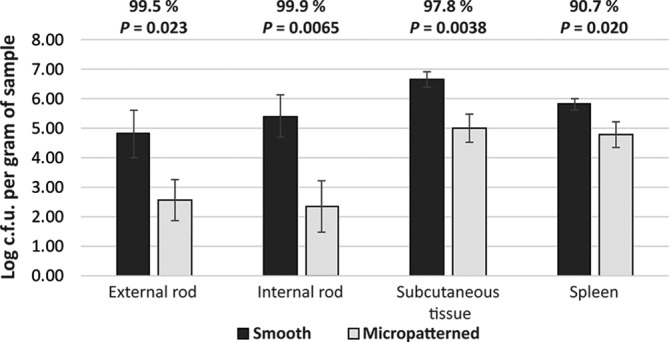

With the micropattern restricting surface adherence and transference off contaminated surfaces, we sought to evaluate whether the micropattern reduces the infection risk in vivo. Here we used a previously described rodent infection model with percutaneous devices [31]. Silicone rods (smooth or micropatterned) were each implanted percutaneously into the back of a rat, followed by S. aureus inoculation on exposed rod surfaces. Rats with micropatterned rods had significantly lower bacterial loads, with 91 % (P<0.05, n=24) and 88 % (P<0.05, n=24) reductions in subcutaneous tissues and spleens, respectively, compared to those with smooth devices (Table 1). In the following trial, rats were treated with the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide to suppress innate immunity. The effect of cyclophosphamide was confirmed as white blood cells were depleted in animals receiving the drug (Table S1, available in the online Supplementary Material). Incorporation of micropatterns dramatically reduced the bacterial burdens in subcutaneous tissues (98 % reduction, P<0.01, n=12) and spleen samples (91 % reduction, P<0.05, n=12) (Fig. 4). In addition, in the study of cyclophosphamide-treated rats, we also evaluated bacterial colonization on implanted devices. Bacterial colonization on external and internal segments was reduced by 99.5 % (P<0.05, n=12) and 99.9 % (P<0.001, n=12) respectively, on micropatterned compared to smooth devices (Fig. 4).

Table 1. The micropattern minimized bacterial burdens in a percutaneous rat infection model.

| Tissue | Device | Mean±sd (log c.f.u. per gram of tissue) | Percentage reduction | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous tissue | Smooth | 4.47±1.46 | 91 % | 0.025 |

| Micropatterned | 3.41±2.13 | |||

| Spleen | Smooth | 3.19±1.03 | 88 % | 0.012 |

| Micropatterned | 2.26±1.65 |

Fig. 4.

Micropatterned surfaces restricted bacterial colonization on devices and lowered bacterial burdens in the tissues of animals treated with cyclophosphamide. Devices were explanted and cut into external and internal segments, which were then processed in Dey–Engley broth and plated onto TSA. Tissue samples were homogenized in PBS and plated onto TSA. The plates were incubated overnight and then the colonies were counted.

Discussion

The in vitro results in this study demonstrate that the Sharklet micropattern, a non-toxic surface microtopography, reduced the colonization of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa bacterial pathogens effectively (Fig. 2). Micropatterned devices also minimized the risk of pathogen transference from contaminated surfaces (Fig. 3). However, modelling medical device-associated infections in vitro is often challenging. Only specific microbial mechanisms contributing to device-related infections can be evaluated in vitro [32–34]. In vitro models were used in this study to specifically isolate the microbial colonization and transference mechanisms. These microbial mechanisms were significantly inhibited on micropatterned compared to smooth surfaces. The application of surface micropatterns therefore has high potential to revolutionize infection control on medical devices such as percutaneous devices. However, the complexities of medical device implantation, including innate immunity engagement, can only be evaluated with in vivo models.

Translational pre-clinical in vivo trials further validated the capacity of micropatterned devices to limit device-associated infections. After being introduced to the external exposed ends of devices placed in the backs of rats, S. aureus was allowed to translocate and establish infection in subcutaneous tissues for several days before rat euthanasia. This was intended to mimic clinical scenarios where devices pass through the skin into deeper tissues. Rats with micropatterned devices had significantly lower S. aureus loads in subcutaneous tissues and spleens compared to those with smooth devices (Table 1).

The superiority of micropatterned surfaces was further confirmed in animals with depleted innate immunity, the first line of defence against infections, by a chemotherapy agent, cyclophosphamide. Cyclophosphamide is a common therapeutic agent that eliminates innate immune cells, including neutrophils and monocytes, effectively [35]. The micropatterned devices still showed significantly lower bacterial burdens compared to control devices in the absence of innate immune effector cells (Fig. 4). In this set of in vivo experiments, the bacterial colonization on implanted rods was also evaluated to determine whether colonization prevention is important. Both external and internal segments of implanted rods were evaluated for bacterial colonization, which was substantially reduced in rats with micropatterned devices (Fig. 4). Therefore, micropatterning is likely one of the most critical factors for inhibiting device-associated bacterial translocation.

The micropattern represents a paradigm shift as an approach to microbial control and infection prevention [24, 36]. Microbial attachment and translocation are critical factors potentiating device-associated infections [37–40]. The bioinspired micropatterned surface provides a device interface that controls bacterial colonization and transference through an ordered arrangement of microscopic features [25]. The physical arrangement enhances the hydrophobicity of the device surface such that the bacteria attachment energy is insufficient for adherence and/or colonization [25]. Adherence prevention and translocation restriction have been demonstrated here, and are believed to contribute significantly to restricting the risk of device-associated infections. Importantly, this infection control was achieved without the aid of antimicrobial agents. Further, the results from this study are consistent with previous in vitro studies of other potential micropatterned medical device products, which showed the efficacy of the micropattern against bacterial adherence and translocation on medical polymeric materials [28, 41–43].

The results in this study demonstrate that micropattern technology offers an effective means to fight against medical device-associated infections. However, the effectiveness of the micropattern technology was only tested in vitro and in animal models using laboratory methods. It has not yet been tested clinically in human patients, and therefore has not been proven to perform effectively in a clinical setting. Future human clinical trials are needed to further validate the effectiveness of this micropattern technology. The interaction of micropatterns with the human body will also need to be better understood to demonstrate their biocompatibility when used as percutaneous devices in humans.

Funding information

Funding for the project was provided in part through the US National Institutes of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant 1 R43 HD085616-01A1.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bryce C. Stevenson, MiKayla M. Henry, Beverly Smith and Jaclyn Strom for fabricating and imaging micropatterned samples. We also thank Mark Spiecker for his support in research development, and Bill Sullivan and Dave Constantine at FLEXcon for providing test materials.

Conflicts of interest

B. X., M. R. M., E. T. P., S. T. R. and E. E. M. are employees of Sharklet Technologies, Inc, while R. M. M. is a former employee. A. B. B. is a paid consultant of Sharklet Technologies, Inc. L. R. and D. H. M. are employees of PreClinical Research Services, Inc.

Ethical statement

The study design and the use of animals in the animal studies were reviewed and approved by the PCRS IACUC (Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee) for compliance with regulations prior to study initiation. The animal welfare, housing and research procedures for this study were conducted in compliance with all federal animal welfare laws, policies and regulations, including the USDA Animal Welfare Act and Animal Welfare Regulations, CFR title 9, chapter 1, subchapter A, parts 1, 2 and 3 (USDA Animal Welfare Act), the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, Public Health Service National Institutes of Health (PHS-NIH) Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for Euthanasia.

Supplementary Data

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AVMA, American Veterinary Medical Association; LD, log cell densities; LR, log reductions; LVADs, left ventricular assist devices; MDR, multiple drug-resistant; PCRS, PreClinical Reseasrch Services, Inc.; PR, percent reductions; RODAC, replicateorganism detection and counting; TSB, tryptic soy broth.

One supplementary table is available with the online Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Zierer A, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, Guthrie TJ, Ewald GA, et al. Late-onset driveline infections: the Achilles' heel of prolonged left ventricular assist device support. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:515–520. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Salgado CD, Chinnes L, Paczesny TH, Cantey JR. Increased rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection associated with use of a needleless mechanical valve device at a long-term acute care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28:684–688. doi: 10.1086/516800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Safdar N, Maki DG. Risk of catheter-related bloodstream infection with peripherally inserted central venous catheters used in hospitalized patients. Chest. 2005;128:489–495. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Renz N, Haupenthal J, Schuetz MA, Trampuz A. Hematogenous vertebral osteomyelitis associated with intravascular device-associated infections - a retrospective cohort study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;88:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haque A, Ahmed SA, Rafique Z, Abbas Q, Jurair H, et al. Device-associated infections in a paediatric intensive care unit in Pakistan. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95:98–100. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leuck AM. Left ventricular assist device driveline infections: recent advances and future goals. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:2151–2157. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.11.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Jayan G, Patwardhan D, Phillips KS. Antimicrobial and anti-biofilm medical devices: public health and regulatory science challenges. In: Zhang Z, Victoria E, editors. Antimicrobial Coatings and Modifications on Medical Devices. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2017. pp. 37–65. (editors) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan ID, Basu A, Kiran S, Trivedi S, Pandit P, et al. Device-associated healthcare-associated infections (DA-HAI) and the caveat of multiresistance in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Med J Armed Forces India. 2016;73:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tafin-Kampé K, Kamsu-Foguem B. Acute osteomyelitis due to Staphylococcus aureus in children: what is the status of treatment today? Pediatr Infect Dis. 2013;5:122–126. doi: 10.1016/j.pid.2013.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger P, Garland J, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:e162–e193. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galiczewski JM, Shurpin KM. An intervention to improve the catheter associated urinary tract infection rate in a medical intensive care unit: direct observation of catheter insertion procedure. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;40:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Casey AL, Mermel LA, Nightingale P, Elliott TS. Antimicrobial central venous catheters in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:763–776. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaali P, Strömberg E, Aune RE, Czél G, Momcilovic D, et al. Antimicrobial properties of Ag+ loaded zeolite polyester polyurethane and silicone rubber and long-term properties after exposure to in-vitro ageing. Polym Degrad Stab. 2010;95:1456–1465. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.06.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber DJ, Anderson D, Rutala WA. The role of the surface environment in healthcare-associated infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:338–344. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283630f04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darouiche RO. Prevention of infections associated with vascular catheters. Int J Artif Organs. 2008;31:810–819. doi: 10.1177/039139880803100909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Darouiche RO, Raad II, Heard SO, Thornby JI, Wenker OC, et al. A comparison of two antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Timsit JF, Dubois Y, Minet C, Bonadona A, Lugosi M, et al. New materials and devices for preventing catheter-related infections. Ann Intensive Care. 2011;1:34. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilbert RE, Mok Q, Dwan K, Harron K, Moitt T, et al. Impregnated central venous catheters for prevention of bloodstream infection in children (the CATCH trial): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2016;387:1732–1742. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00340-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnell SA, Gubbins PO, Anaissie EJ. Do antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters prevent catheter-related bloodstream infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:65–72. doi: 10.1086/375227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickard R, Lam T, MacLennan G, Starr K, Kilonzo M, et al. Antimicrobial catheters for reduction of symptomatic urinary tract infection in adults requiring short-term catheterisation in hospital: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2012;380:1927–1935. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Antibiotic/antimicrobial resistance. 2017. www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/ Available from.

- 22.Teleflex Chlorag+ard® Technology. 2017. www.teleflex.com/usa/product-areas/vascular-access/vascular-access-catheters/central-access/long-term-central-venous-catheters/chloragard-technology/?language_id=1 Available from.

- 23.Lodise TP, Mckinnon PS. Burden of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: focus on clinical and economic outcomes. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1001–1012. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.7.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chung KK, Schumacher JF, Sampson EM, Burne RA, Antonelli PJ, et al. Impact of engineered surface microtopography on biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus. Biointerphases. 2007;2:89–94. doi: 10.1116/1.2751405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Decker JT, Kirschner CM, Long CJ, Finlay JA, Callow ME, et al. Engineered antifouling microtopographies: an energetic model that predicts cell attachment. Langmuir. 2013;29:13023–13030. doi: 10.1021/la402952u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher JF, Carman ML, Estes TG, Feinberg AW, Wilson LH, et al. Engineered antifouling microtopographies - effect of feature size, geometry, and roughness on settlement of zoospores of the green alga Ulva. Biofouling. 2007;23:55–62. doi: 10.1080/08927010601136957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choi L, Choudhri AF, Pillarisetty VG, Sampath LA, Caraos L, et al. Development of an infection-resistant LVAD driveline: a novel approach to the prevention of device-related infections. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/S1053-2498(99)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann EE, Manna D, Mettetal MR, May RM, Dannemiller EM, et al. Surface micropattern limits bacterial contamination. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3:28. doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.von Bayern MP, Arrecubieta C, Oz S, Akashi H, Cedeiras M, et al. Development of a murine ventricular assist device transcutaneous drive-line model. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:812–814. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steven Leary WU, Anthony R, Cartner S, Corey D, Grandin T, et al. AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. 2013 ed. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toba FA, Akashi H, Arrecubieta C, Lowy FD. Role of biofilm in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis ventricular assist device driveline infections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:1259–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cotter JJ, Maguire P, Soberon F, Daniels S, O'Gara JP, et al. Disinfection of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms using a remote non-thermal gas plasma. J Hosp Infect. 2011;78:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drescher K, Shen Y, Bassler BL, Stone HA. Biofilm streamers cause catastrophic disruption of flow with consequences for environmental and medical systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:4345–4350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300321110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coenye T, Nelis HJ. In vitro and in vivo model systems to study microbial biofilm formation. J Microbiol Methods. 2010;83:89–105. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiseman AC. Immunosuppressive medications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:332–343. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08570814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carman ML, Estes TG, Feinberg AW, Schumacher JF, Wilkerson W, et al. Engineered antifouling microtopographies–correlating wettability with cell attachment. Biofouling. 2006;22:11–21. doi: 10.1080/08927010500484854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams GJ, Stickler DJ. Some observations on the migration of Proteus mirabilis and other urinary tract pathogens over foley catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:443–445. doi: 10.1086/529551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harkes G, Dankert J, Feijen J. Bacterial migration along solid surfaces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1500–1505. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1500-1505.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Darouiche RO, Safar H, Raad II. In vitro efficacy of antimicrobial-coated bladder catheters in inhibiting bacterial migration along catheter surface. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1109–1112. doi: 10.1086/516523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darouiche RO. Device-associated infections: a macroproblem that starts with microadherence. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1567–1572. doi: 10.1086/323130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.May RM, Magin CM, Mann EE, Drinker MC, Fraser JC, et al. An engineered micropattern to reduce bacterial colonization, platelet adhesion and fibrin sheath formation for improved biocompatibility of central venous catheters. Clin Transl Med. 2015;4:9. doi: 10.1186/s40169-015-0050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.May RM, Hoffman MG, Sogo MJ, Parker AE, O'Toole GA, et al. Micro-patterned surfaces reduce bacterial colonization and biofilm formation in vitro: potential for enhancing endotracheal tube designs. Clin Transl Med. 2014;3:8. doi: 10.1186/2001-1326-3-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy ST, Chung KK, Mcdaniel CJ, Darouiche RO, Landman J, et al. Micropatterned surfaces for reducing the risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection: an in vitro study on the effect of sharklet micropatterned surfaces to inhibit bacterial colonization and migration of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. J Endourol. 2011;25:1547–1552. doi: 10.1089/end.2010.0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.