Abstract

Brain injuries affect a large patient population with major physical and emotional suffering for patients and their relatives and at a significant cost to the society. Effective diagnostic and therapeutic options available for brain injuries are limited by the complex brain injury pathology involving blood brain barrier (BBB). Brain injuries, including ischemic stroke and brain trauma, initiate BBB opening for a short period of time which is followed by a second re-opening for an extended time. The leaky BBB and/or the alterations in the receptor expression on BBB may provide opportunities for therapeutic delivery via nanoparticles (NPs). The approaches for therapeutic interventions via NP delivery are aimed at salvaging the pericontusional/penumbra area for possible neuroprotection and neurovascular unit preservation. The focus of this progress report is to provide a survey of NP strategies employed in cerebral ischemia and brain trauma and finally provide insights for improved NP-based diagnostic/treatment approaches.

Keywords: cerebral ischemia, traumatic brain injury, nanoparticles, blood brain barrier, therapeutic nanoparticle delivery

1. Introduction

Diagnosis and treatment of acquired brain injuries remains a considerable challenge, particularly, after stroke and traumatic brain injury (TBI).[1–5] Brain injuries affect a large patient population, with major physical and emotional suffering for patients and their relatives and at a significant cost to the society.[6–9] These injuries may not only lead to substantial tissue damage with irreversible functional loss, they also lead to disruption of the intricate neural circuits and connections involved in cognitive, sensor-motor functions.[10,11] The complex pathology that ensues after brain injury limits effective diagnostic and therapeutic options available.[11] Moreover, access to the brain is typically regulated by the blood-brain barrier (BBB) thus presenting a formidable obstacle for small and macromolecular therapeutics to enter the brain.[12] Therefore, diagnosis/treatment via systemic administration or local delivery of drugs is largely inefficient.[13] Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of nanotechnologies for brain injury applications are tremendous and may eventually offer the novel clinical opportunities to address current limitations.

This progress report aims to summarize the recent research on systemic delivery of nanoparticles for brain injury via blood-brain barrier. TBI and the ischemic stroke injury share common pathological progression; therefore, it is appropriate to compare recent advances in nanoparticle applications for each of these injuries.

2. Brain injury: Pathology and blood brain barrier breakdown

Stroke results from insufficient oxygen reaching cells of the brain due to arterial occlusion (ischemic stroke, IS, or arterial hemorrhagic stroke, HS). In the US about 800,000 strokes occur annually with IS accounting for 87% of the stroke cases.[14] IS or cerebral ischemia is most often due to a severe reduction in cerebral blood flow (CBF) stemming from cardiac arrest and/or hypotension of the cerebral and extra-cerebral vessels. Alternatively, thrombus formation caused by plaque build-up and damage to the endothelium allows platelets aggregation which ultimately leads to activation of the coagulation cascade. Finally, the blood flow through the extracranial and intracranial systems is reduced and collateral circulation maintains the functions. The occluded blood vessel(s) leads to a volume of tissue that is functionally impaired but structurally intact surrounding the ischemic core.[15–17] The tissue surrounding the ischemic core (ischemic penumbra) is potentially recoverable brain tissue. The severe reduction in CBF leads to deprivations in oxygen and glucose delivery and hence metabolic imbalance and hypoxia thus leading to the build-up of potentially toxic substances.[18]

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is damage to the brain that occurs as a result of a traumatic event such as falls and traffic accidents,[19] with over one million people visiting emergency rooms in the US each year because of TBI.[6] TBI accounts for an estimated 235,000 hospitalizations annually in the US, with 80,000 of these cases resulting in lasting disability.[6],[20] Common pathological consequences of TBI include hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, contusion, and diffuse axonal injury.[21] After TBI, the shearing forces generated by head trauma imparts mechanical damage to endothelial cells may lead to acute BBB permeability and extravasation of plasma protein and red blood cells.[10,22,23] The microvessel disruption rapidly activates the coagulation cascade forming intravascular thrombi in capillaries of the peri-contusional area.[22,24] Moreover, platelet and leukocyte-platelet aggregates have been observed within pial and parenchymal venules after injury. Consequently, a substantial decline in the CBF develops in pericontusional brain tissue.[10,21] This post-traumatic intravascular coagulation resembles the no-reflow phenomenon observed after cerebral ischemia.[22,24] Ischemia is regarded as one of the most important mechanisms underlying secondary brain damage post-TBI, about 90% of TBI patients who die display ischemia on pathological tissue examination.[25]

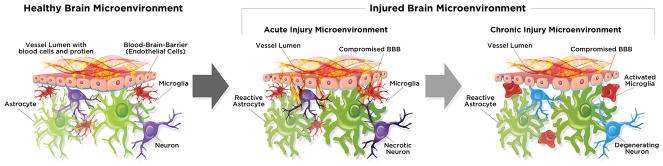

Ischemic injury induces reduction in oxygen accessibility and ceases molecular shuttling of electron in oxidative phosphorylation which leads to decline in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. Ionic gradient failure results due to energy depletion in the neuronal cells through interruption of the ATP-dependent Na+/K+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase activity. When ionic balance is disrupted, cations in the extracellular fluid (e.g. Na+) accumulate inside the cells finally leading to cytotoxic edema.[26,27] Moreover, Na+ uptake causes extensive plasma membrane depolarization and eventually bringing additional Ca2+ into the cell[26]. Influx of Ca2+ stimulates the release of neurotransmitters such as glutamate or dopamine into the synapse, leads to neurotoxic shock and ensuing neuronal cell death and development of an ischemic core.[18] Consequently, calcium homeostasis in the central nervous system (CNS) is disrupted leading to generation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a host of catalytic enzymes that damage proteins and DNA.[18,26] In the ischemic core, the neurons die through these necrotic processes and release cytotoxic elements into the interstitial space which then penetrate adjacent neurons[18]. Furthermore, cerebral ischemia is accompanied by widespread release of inflammatory cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.[18,27,28] Collectively, these neurochemical events contribute to lipid peroxidation and disruption of the BBB.[18,27,28] Figure 1 outlines the changes in the brain microenvironment after brain injury.

Figure 1.

Microenvironment of a healthy and injured brain: pathological changes after brain injury. Healthy brain microenvironment consists of an intact BBB with healthy astrocytes, microglia and neurons. Brain injured microenvironment may shift to an altered state that evolves over time and may include compromised BBB, reactive astrocyte, activated microglia and necrotic/degenerating neurons.

The BBB is one of the most vital component of a physiological normal brain creating a restrictive barrier between the CNS and the rest of the body.[19] The BBB performs the major function as physical and transport barrier to monitor the influx of substances from blood via paracellular/transcellular diffusion and/or transport proteins.[29] Ischemic stroke and brain trauma initiates BBB opening for a short period of time (minutes to hours), which is followed by a second re-opening for an extended time (hours to days).[10,16,26,30,31] The reperfusion of the ischemic region (restitution of the blood supply) is vital to reduce brain injury, but this event can also lead to reperfusion injury contributing to the latter BBB reopening. The BBB dysfunction is mainly associated with dysregulation of tight junction proteins.[10,30] Tight junction protein complexes situated between endothelial cells control BBB permeability by limiting paracellular diffusion; key tight junction proteins include junctional adhesion molecules, occludin, claudins and membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like proteins (ZO-1,-2,-3).[32] Oxidative stress due to ROS and free radical production after brain injury (cerebral ischemia/trauma) alter the critical organization of tight junctions proteins at the BBB resulting in increased paracellular leakage.[10,33] Additionally, astrocytes influence the BBB disruption after brain injury by mechanisms such as opening of paracellular channels, physical disruption of astrocyte-endothelial junctions and digestion of BBB matrix proteins.[34,35]

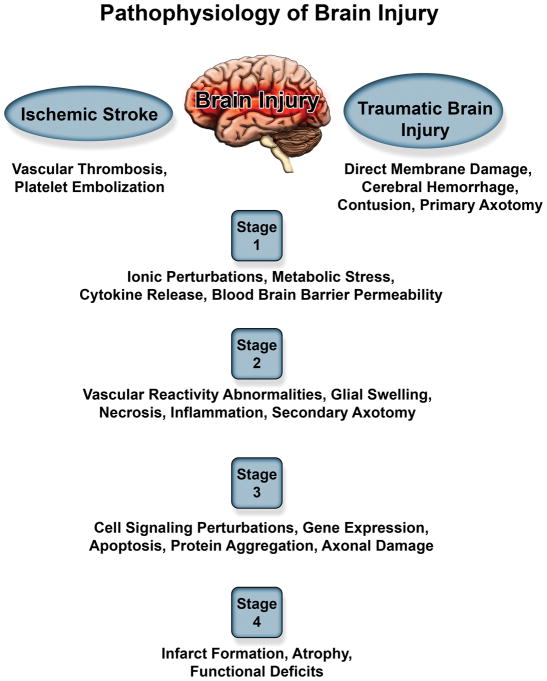

Although cerebral ischemic and traumatic brain injuries arise from very different initial insults, both lead to a diverse spectrum of injury pathologies. Focal/blunt head trauma causes primary membrane damage to neural cells, white matter, and vasculature resulting in secondary injury. On the other hand, severe ischemia leads to metabolic stress, ionic metabolism, complex biomolecular cascading events culminating in neuronal loss. (Figure 2) illustrates the differences/similarities in the pathogenesis of these two brain injuries and highlights the various stages to potentially develop therapeutic strategies to combat ischemia.

Figure 2.

Summary of pathophysiology of ischemic stroke and traumatic brain injury demonstrating overlapping pathology between the two injuries.

Conclusively, a better understanding of the brain injury pathology and the BBB permeability is instrumental for developing improved therapeutic interventions. The BBB dysfunction (initial and late opening) enables blood-borne substances that are normally restricted, such as proteins, red blood cells to enter the brain parenchyma. The leaky BBB and/or the alterations in the receptor expression on BBB may provide opportunities for therapeutic delivery via nanoparticles (NPs). The strategies for therapeutic interventions via NP delivery are aimed at salvaging the pericontusional/penumbra area for possible neuroprotection and neurovascular unit preservation. Specifically, nanoparticle-based applications have been extensively explored in the cerebral ischemia field, as compared to brain trauma research with minimal NP exploration. The focus of this progress report is to provide a survey of previous NP studies used to address brain injury. Particularly, discussing the NP strategies administered via systemic injection employed following different injury pathologies and finally provide insights for improved NP-based diagnostic/treatment approaches.

3. Factors that influence nanoparticle brain delivery across the BBB

Nanoparticles (NPs) as defined for pharmaceutical purposes are solid colloidal particles ranging from 1 and 1000 nm in size[36–38] and are utilized for various biomedical applications due to their pharmacological attributes.[39,40] Their small size and mobility enable NPs to access a wide range of tissues and cells for both extracellular and intracellular delivery. Administration of NPs through the microcirculation is a viable approach for facilitating drug delivery to the brain, since the diameter of the smallest capillaries is approximately 5–6 μm.[41] NPs can be used to deliver hydrophilic/hydrophobic drugs, proteins, vaccines, biological macromolecules, gene delivery, etc.[42] Engineered NPs have the potential to revolutionize the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases due to their unique function and structural organization.[43,44] Over two-dozen NPs systems have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinic to either treat or diagnose diseases with additional formulations in clinical trials.[45,46] One advantage of nanomaterials is the potential interaction with biological systems at a molecular and supra-molecular level. Such interactions may be tailored to induce desired physiological responses in cells while reducing undesirable systemic side effects.[47]

For a NP delivery system to achieve the desired benefits, the residence time in the bloodstream must be long enough for the NP to reach or recognize its site of action. However, the major obstacle to the realization of this goal is NP clearance from the bloodstream where previous studies report only 1–5% of injected NPs may actually reach their intended target site.[48,49] The main NP clearance mechanisms are the same as the body’s removal of foreign material from the bloodstream. These coordinated mechanisms include opsonization, renal clearance, and sequestration in the mononuclear phagocytic system (MPS), previously known as the reticuloendothelial system. Phagocytic recognition and clearance is dependent on initial particle opsonization and as such recent research has focused on developing methods to effectively slow this process resulting in increased blood circulation half-life.[50] Key NP parameters identified to help evade clearance mechanisms include surface modification, size, charge and shape.[48] Quantitative associations between such NP properties (size, surface charge, and surface coating) and biodistribution parameters have been studied in the recent years using physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models.[51–53] PBPK models may enable improved experimental data interpretation in the rational designs of NPs and may potentially predict in vivo absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of NPs prior to experimental studies [51–53] Furthermore, we note that recent reviews have addressed the complex response of the MPS and NP clearance[48,54] that are only briefly mentioned in the sections below.

3.1 Composition

Nanoparticles can be synthesized using various materials and protocols where the parameters of which are trailered to design the desired NPs. Most essential characteristics for drug delivery considerations are size, payload encapsulation efficiency, zeta potential and payload release characteristics.[39,41,55,56] The ideal properties of NPs for brain drug delivery are not only to be nontoxic, biodegradable and biocompatible, but also have physical stability in blood with prolonged blood circulation and ability to cross BBB.[57–60] Different NPs used for brain injury applications include polymeric NPs (liposomes, dendrimers, chitosan), lipid NPs, inorganic NPs (silica, metals) and hybrid NPs.

Polymeric NPs made up of a polymeric core or shell can be formulated to potentially penetrate the BBB, encapsulate various drug formulations, and facilitate targeted delivery. Thus it is not surprising that polymeric NPs are the most popular nano-platforms for neurological diseases.[39] Polymeric NP formulations include sphingomyelin and phosphatidylcholine (liposomes),[38] chitosan, dendrimers, polylactides (PLA), polyglycolides (PGA), poly(lactide-co-glycolides (PLGA),[61] and polycyanoacrylates. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved biodegradable PLGA for clinical applications and liposomes for brain delivery.[45] The most common preparation methods include solvent evaporation,[62,63] polymerization methods[62,63] and solvent diffusion such as single- and double-emulsion methods.[64,65] Polymeric NPs can be used for controlled release of bioactive agents (such as PLGA, PLA, polycyanoacrylates[38,66,67]) and can also be used for improving drug solubility, stability with enhanced efficacy and reduced toxicity (such as dendrimers[59] and chitosan[68]). Moreover, polymeric NPs such as liposomes can be developed for liposome-triggering modalities such as thermal and/or photo sensitive platforms.[69],[70,71],[72–75]

Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) or lipid NPs are stable lipid-based nanocarriers with a solid hydrophobic lipid core for drug encapsulation. These NPs are made with biocompatible lipids such as triglycerides and fatty acids. The most common methods for SLNs include high pressure homogenization at elevated or low temperatures, microemulsion, solvent emulsification-evaporation or –diffusion.[76] They can be fabricated to have enhanced drug entrapment efficiency compared to other NPs and ability to provide a continuous release of drug over weeks[59]. Furthermore, these NPs can be conjugated with targeting moieties on their surface in effort to enhance brain specificity and limit MPS uptake.[59,77]

Inorganic NPs such as ceramic NPs are composed of silica, alumina, metals, and carbon based NPs.[42] Silica NPs can be synthesized using calcium phosphate with a hollow core for physical entrapment of the payload[42]. Moreover, silica core NPs coated with a thin gold shell have been used to produce different shapes such as nanosized spheres, shells and rods.[42] These NPs can be varied in size and surface composition to escape clearance via MPS.[42] Magnetic NPs based on iron oxide have been used as contrast agents for MRI. The surface of the iron oxide NPs can be coated with silica or conjugated with PEG for diagnostic applications.[42,78,79] Carbon based NPs such as nanotubes and fullerenes have recently been gaining attention.[80–82] These NPs are popular as drug carriers due to their small size, cage-like architecture and ability for surface functionalization.[83,84]

In the recent years, novel integrated hybrid NPs have been developed including lipid-polymer hybrid NPs (LPN) and organic-inorganic hybrid NPs. The core-shell structure of LNPs result in high structural integrity, shelf-life and controlled drug release[85–87]. Furthermore, organic-inorganic NPs are known to have diminished initial drug burst and have tunable surface chemistry[88,89]. Examples of organic-inorganic hybrid NPs include iron oxide coated with chitosan hybrid NP,[89]siloxane hybrid NP,[90–92] copolymers [93] and dendrimers[88].

3.2 Surface modification

Surface modification of NPs is one key parameter used to escape clearance mechanisms, particularly opsonization. Seminal studies demonstrated masking of NPs from opsonization by conjugating the hydrophilic polymer polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto NP surface.[94–96] PEG substantially reduces nonspecific interactions with proteins through its hydrophilicity and steric repulsion effects, which results in reduced opsonization.[97] For example, Lu et. al., demonstrated markedly prolonged blood circulation of PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin compared to native liposomes. Specifically, the elimination half-time of regular and PEGylated liposomes were ~26 and ~46 h, respectively, thus nearly doubled by simply PEGylating the NP surface.[95] Similarly, Sadzuka et. al., observed prolonged plasma circulation of liposomes and increase of drug accumulation in the tumor by employing PEGylated liposomes.[98] Therefore, PEGylation dramatically influence the NP delivery to improve NP circulation half-life.

3.3 Size

Small molecules (< 1kDa) such as free drug and contrast agents are removed from blood circulation via renal clearance by glomerular filtration into the urine. Glomerular filtration is dictated largely by a molecular size with a cut-off for compounds smaller than 5–6 nm.[99] For systemic delivery, the upper size limit of NPs size is about 5–8 μm dictated by the smallest diameter of lung micro-capillaries.[100] Larger particles carry the risk of clogging the vessels inducing embolism.[100] Generally, for brain delivery NPs ranging from 20 – 100 nm are used for leveraging minimal clearance NPs.[96,101,102] Studies have shown a clear inverse correlation between NP size and BBB penetration.[103,104] We previously reported NP delivery to the brain via the transiently breached BBB due to focal brain trauma. The study demonstrated the ability of smaller NPs (20, 40 nm) for prolonged access to the injured brain compared to larger NPs (100, 500 nm).[104] To this end, for systemic brain delivery, the NP size plays an important role for enabling prolonged blood circulation and access to the brain.

3.4 Charge

Another key parameter to consider for systemic delivery of NPs is the surface charge, which influences clearance and stability in circulation. Here one must consider the impact blood proteins and cells have on the stability of NPs in vivo. For example, in vitro studies limited to NPs suspended in saline or deionized water require a high zeta potential of more than 30 mV (either positive or negative) to maintain the stability and prevent aggregation. [105,106] Yet, systemically delivered positively charged NPs in vivo readily form aggregates with the negatively charged serum proteins and often cause embolism(s) in the lung capillaries.[100] Generally, negative NPs (~ − 40 mV) exhibit strong MPS uptake and positive NPs (~ + 40 mV) induce serum protein aggregation.[96,107] NPs with neutral charge (within +/− 10 mV) exhibit the least MPS interaction and the longest circulation in vivo.[96,107] Specifically, for brain delivery studies have shown that highly positive NPs (~ + 45 mV) cause immediate toxicity with BBB disruption.[108] On the other hand, neutral and moderately negative NPs did not show toxic effect and can be utilized for brain delivery.[108]

3.5 Shape

The morphology and shape of the NPs also contributes significantly to cellular uptake, transport and biodistribution.[109] The shape of NPs is significant in cellular uptake and internalization pathway.[110] Round shape/spherical NPs are the most common due to their ease of synthesis and fast rate of endocytosis while other shapes (rod, cube, disk) have gained attention for their advantage in cellular internalization and efficiency of drug loading.[111] For example, NPs with disc or rod or spherical shape of size 150–200 nm, display enhanced cellular uptake and internalization in cells via clathrin-mediated endocytosis.[112] In contrast to NPs larger than 200 nm are preferentially taken up via macropinocytosis or phagocytic pathway.[112] However, it is noted that at some level, both mechanisms could happen simultaneously.[112] Furthermore, shape-induced NP enhancement of vascular targeting in the brain via receptor mediated delivery was confirmed by Kolhar and group. [113] Specifically, the rod shaped polystyrene NPs decorated with an anti-transferrin receptor antibody showed 7-fold increase in brain accumulation compared to NPs with spherical shape with the same surface chemistry.[113] Regional distribution of NPs within the brain following systemic injection has also been linked with NP shape. Chaturbedy et al demonstrated the preferred regional localization of iron oxide NPs with various shapes (sphere, biconcave, spindle, and nanotube) across the cerebral cortex and cerebellum in vivo.[114] In addition, in vitro study on C6 glioma cells demonstrated subcellular localization of iron oxide NPs varied substantially with different geometries. Specifically, NPs of biconcave shape mostly accumulated in nuclei of brain cells while the nanotube NPs accumulated in the cytoplasm or periphery of the nucleus. This concept may be useful to design for targeting specific subcellular location (nuclei vs cytoplasm) in the field of molecular imaging or drug delivery.

The shape of the nanoparticles may be easily manipulated or controlled through either ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom up’ fabrication methods. ‘Bottom-up’ methods generate nanoparticles from molecular species while the ‘top-down’ methods apply external force on bulk material to control the size of shape of NPs.[115] ‘Bottom-up’ methods facilitate emulsion polymerization (oil-water, water-oil-water)[66] and self-assembly,[116] by which targeting moieties can be easily conjugated to the surface of the structures.[109] Most commonly, NPs fabrication using the ‘bottom-up’ strategies produce round or spherical shape of NPs due to limitation in entropy and thermodynamic energy.[117] ‘Top-down’ techniques may be employed to produce monodisperse, non-spherical NPs. For example, the unique technique of PRINT (Particle Replication In Non-Wetting Template) a soft lithography with template of perfluoropolyethers (PFPE) can be used to produce designated sizes and shapes.[115]

Taken together, systemically delivered NPs eventually will be cleared through renal clearance, phagocytosis or by the MPS (either by the liver and/or the spleen uptake). The studies outlined above and summarized in (Table 1) describe strategies aimed at slowing this process by escaping different clearance mechanisms leading to prolonged blood circulation and delivery to the brain.

Table 1.

Summary of factors affecting the biodistribution and pharmacokinetics of nanoparticles for systemic delivery (Optimal NP size for brain delivery pertains to injured brain)

| Factors | Parameter | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Surface modification | PEGylation | Optimal for prolonged circulation[95],[98] |

| Size | 70–200 nm | Optimal for prolonged circulation[96,101,102,195] |

| 20–100 nm | Optimal for brain delivery[101,102,104,196] | |

| > 300 nm | Prone to splenic uptake[107] | |

| ~ 5 nm | Prone to renal clearance[99] | |

| Charge | Neutral | Reduced MPS uptake and optimal for brain delivery[96,107],[108] |

| Positive | Agglomeration[96,107] | |

| Negative | MPS uptake[96,107] | |

| Shape | Spherical | Easy to prepare[111] |

| Ab coated rod | Increased brain accumulation[113] |

PEG (polyethylene glycol), MPS (mononuclear phagocytic system), Ab (antibody)

4. Strategies for brain delivery of nanoparticles - Mechanisms of delivery via systemic administration

The blood brain barrier (BBB) is comprised of brain capillary endothelial cells (BCEC) and other cell types such as neuronal cells, pericytes, and astrocytes.[118] The tight junctions among BCECs play significant roles in maintaining homeostasis by preventing unregulated transport into/out of the brain.[33] BBB provides about one of the largest surface area (~ 20 m2) between the periphery and CNS, thereby generating a key access route for most endogenous and drug delivery molecules.[118] In addition, foreign molecules are also transported from brain to blood via efflux mechanism to mitigate toxicity and maintain homeostasis in the brain.[119] Therefore, NP delivery to the brain at large needs to consider strategies to first cross the BBB to enhance the NP delivery to the brain. Such strategies may be broadly classified into passive and active delivery approaches.

Passive delivery of NPs in the brain predominately relies on the functional state of the BBB. Particular pathological events such as inflammation or hypoxia (typically due to tumor, infarct, and/or trauma) has previously been shown to disrupt the normally tightly regulated BBB to produce leaky blood vessels.[120] Such permeable blood vessels provide an opportunity for the systemically circulating NPs extravasate and spontaneously accumulate in the interstitial space.[104,120–122] In tumor literature particularly, such passive NP delivery is known as enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, where NPs enter the tumor interstitial space and are retained due to compromised lymphatic filtration.[120] Analogous to tumor microenvironments, a dysfunctional BBB occurs after brain injury or neuroinflammation diseases can lead to opening of the tight junctions resulting in a leaky vasculature.[10,102] The NPs may accumulate in the brain parenchyma due to increased paracellular permeability through the leaky vasculature.[59,102] However, the BBB permeability is transient and the timing of the NP delivery needs to be fine-tuned to take advantage of these changes in the membrane permeability.[104] For example, our group has demonstrated a critical time window (~ 13 h) for NP delivery after brain injury in pre-clinical rodent moderate/severe TBI models.[104] NPs passively accumulate within the injury penumbra and the amount of NPs accumulation depends on temporal resolution of the BBB permeability post trauma.[104]

Although passive delivery may facilitate the transport of NPs through BBB, poor distribution of NPs in the brain remains a challenge.[123] Thus, active transport such as adsorptive-mediated and receptor-mediated transcytosis has been commonly explored in effort to enhance selective targeting and reach intracellular compartment after delivery. The adsorptive-mediated transcytosis mechanism is based on NP surface functionalization (conferring a positive charge) allowing electrostatic interaction with the BBB luminal surface (negatively charged).[59] One strategy is to synthesize the NPs composed of positively charged constituents such as cationic cholesteryl hydrochloride.[59] An alternative strategy is to functionalize the NP’s surface with cationic biomolecule such as cell-penetrating peptides (TAT peptide) and cationic proteins (albumin).[124] For example, Lu et. al generated cationic albumin-conjugated PEGylated NPs for gene therapy of gliomas and NPs successfully crossed the BBB and arrived at the endothelial cytoplasm, which then in turn induced apoptosis and delayed in tumor growth.[124] Caution should be noted for this strategy as research has shown that vesicular transport is actively down-regulated due to nonspecific exposure to cationic molecules thereby potentially inducing damage to the BBB.[108]

More recent strategies for NP delivery across BBB is receptor-mediated transcytosis which is based on the presence of specific receptors on the luminal surface of cells.[59,119,125,126] Specifically, NP delivery is facilitated by displaying high affinity ligands on the NP surface to overexpressed BCEC receptors (i.e., transferrin (Tf) receptor,[127] low-density lipoprotein receptor,[128] insulin receptor,[126] or leptin receptor[129]) or common pathogenic targets (see review[130]). Upon ligand/receptor engagement, a clathrin-coated vesicle (diameter of 120 nm) forms from the plasma membrane initiating endocytosis.[131] The vesicle(s) then moved through BCEC cytoplasm and transported to the abluminal side of the cell.[131] The last step consists of exocytosis of said vesicle(s) at the abluminal side of the brain capillary endothelium.[132] Particularly, for BBB targeting the Tf receptor expressed on hepatocytes and endothelial cells of the BBB is of one the most extensively studied.[59,125,126] Wiley et al used gold NPs conjugated with Tf to probe receptor-mediated transcytosis mechanism via the transferrin receptor.[127] The study reported that accumulation of NPs in the brain parenchyma was directly dependent on the NP surface Tf concentration implying the tuning possibility of NPs avidity to the target receptors. However, caution should also be exercised when choosing the high affinity ligands for specific receptor, which strong bonding is not always efficient. For example, Cabezon et al reported anti-Tf antibody (8D3) enabled the transport of gold NPs (size of 20nm) via Tf-receptor mediated and independent clathrin-receptor pathway.[133] Results showed that although large amount of the NPs entered the BCECs, a small fraction of the NPs did not reach the brain parenchyma due to strong interaction between Tf receptor and anti-Tf antibody. Therefore, decreasing the affinity between antibody and receptor by utilizing low-affinity antibody[134] or single antibody fragment[135] might serve as a better strategy to complete the transcytosis of NPs.

Another receptor-mediated transcytosis mechanism is via lipoprotein receptors that are known to be highly expressed on endothelial brain microvessels and specifically recognize apolipoprotein E (apoE).[59,125,126] Strategies to exploit this target have been reported by functionalizing the NPs with surfactants. Coating of NPs with surfactants such as polysorbate 80[136], Pluronic P85[137], and poloxamer 188 are known to preferentially adsorb apoE and display ability to cross the BBB via lipoprotein receptors.[125,126,138–140] For example, studies[141,142] used poly(butylcyanoacrylate) (PBCA) NPs loaded with drugs and coated with polysorbate 80 and showed significantly higher concentration of the drug in the brain. The PBCA NPs did not induce nonspecific BBB disruption but occurred due to apoE adsorption to facilitate BBB crossing.[142]

Elucidating the transport mechanism is important in design and development of NPs for maximum efficiency of delivery to the target location. Passive and active mechanisms have been used for NP delivery to the brain across the BBB. Passive delivery of NPs via the leaky vasculature results in accumulation of large amount of NPs at the enhanced permeability region, however these pathway also might induce non-specific targeting.[123] Active delivery of NPs occurs via receptor-mediated transcytosis (such as transferrin and lipoprotein receptor) that relies on ligand-receptor affinity. Endogenous ligands, antibodies, peptides, and surfactants have been utilized in delivery of NPs across BBB to induce specific site targeting and reduce systemic side effects.[143]

5. Nanoparticles for drug delivery after the brain injury – NP transport though leaky BBB and BBB permeable NPs

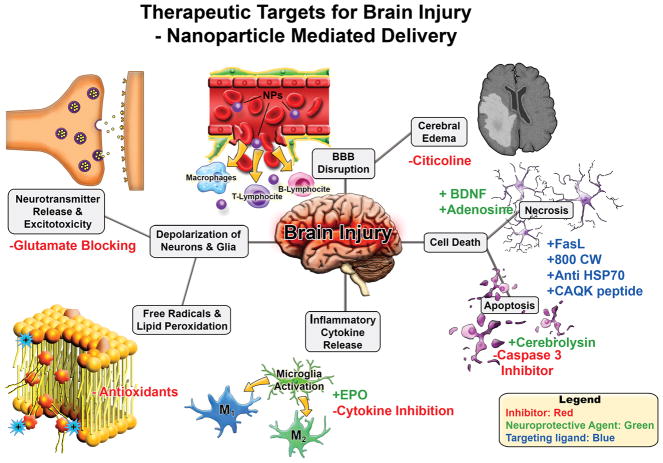

As previously described in the section above, systemic delivery of NPs to the CNS has numerous barriers to overcome for the delivery to the intact CNS. However, neural injury, particularly brain injury assaults such as stroke and TBI, provide a unique window of BBB disruption that NP delivery may be able to exploit to enhance passive delivery to injury penumbra. In this section, we highlight studies that exploit passive or active delivery mechanisms following brain injury to achieve drug delivery of various therapeutic molecules, summarized in (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Therapeutic targets for brain injury for nanoparticle mediated drug delivery. Brain injury leads to a cascade of secondary damage events (denoted in grey boxes). These secondary injuries are potential targets for therapeutics where NP delivery may be useful. Potential interventions strategies are highlighted with red/green/blue font where inhibitors/blocking agents are in red, neuroprotective agents via pathway modulation in green, and targeting ligands in blue.

5.1 Passive delivery

Brain injury may lead to increased BBB permeability possibly due to disruption of tight junctions mediated by injury induced signaling milieu.[10] Under such conditions, the passage of normally impermeable molecules including NPs increases across the BBB.[59] Several groups have exploited this transient BBB disruption acutely after brain injury to administer therapeutics such as erythropoietin, neurotransmitters and antioxidants via NPs.[122,144–146] This section highlights recent studies in this space, which is summarized in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of various nanoparticles for passive delivery for ischemic stroke and brain trauma applications

| Platform | NP size (nm) | NP zeta (mv) | Disease model | Animal model | Injection | Conclusion | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEGylated ceria NPs | ~18 nm | - | MCAO | Rats | i.v. | Reduced infarct volumes and cell death, 6h post-injury. | [175] |

| Platinum NPs | 2–3 nm | - | MACO | Mice | i.v. | Attenuated neurological brain damage with neuroprotective effects and reduction of MMP9 activity. | [176] |

| Rutin encapsulated chitosan NPs | 100 nm | ~30mV | MCAO | Rats | i.v. or i.n. | Neurobehavioural activity and reduced infarct volume and neuronal death. | [178] |

| PEGylated hydrophilic carbon cluster (PEG-HCC) | 50 nm | - | TBI - Mild (CCI) | Rats | i.v. | Improved CBF normalized oxidative radical profile (NO levels). | [171] |

| Nanodrug with TEG vitamin E with cy5 fluorescent tracer. | ~100 nm | - | TBI - CCI | Mice | i.v or i.p. | Behavior study showed significance for OFT (ambulatory) after i.v. injection as compared to saline group and not in i.p. | [122] |

| Cerium oxide NPs | 10 nm | - | TBI - FPI | Rats | i.v. | Reduction in macromolecular oxidative damage Improvements in cognitive function. | [172] |

| Oxygen reactive polymer | 8 nm | - | TBI - CCI | Mice | i.v | Reduced neurodegeneration, astrogliosis and activated microglia. | [173] |

| Mucoadhesie nanoemulsion with thymoquinine | ~100 nm | −13mV | MCAO | Rats | i.n. or i.v. | Improved neurobehavioral activity (locomotor and grip strength). | [180] |

| Liposomes encapsulated with asialo-erythropoietin (aEPO) | 129 nm | 0.29 mV | MCAO | Rats | i.v | Reduction in infarct volume and apoptotic cells; improvement in motor activity. | [144] |

| Cilostazol (CLZ) encapsulated NPs | 80 nm | - | MCAO | Mice | i.v | Attenuation of neurological deficits | [197] |

| PLGA NPs with thyroid hormone, glutathione coating | 326 nm | −1.7 mV | MCAO | Mice | i.v | 58% and 75% decrease in tissue infarction and brain edema, respectively. | [198] |

| Squalenoyl adenosine NPs | ~150 nm | −20.6 mV | MCAO | Mice | i.v. | Significant reduction in infarct volume, neurological deficit score. | [159] |

| PLGA NPs encapsulated with cerebrolysin | 250–330 nm | −13 mV | TBI - Stab wound | Rats | i.v. | Thwarts the edema formation at longer time points compared to bolus injection. | [67] |

| Gold NPs | 20 nm | - | MCAO | Rats | i.v. | Reduction in neurological deficits and infarct volume, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effect. | [199] |

| Liposome encapsulated hemoglobin | 230 nm | - | MCAO | Rats Monkey | i.v. | Significant reduction in brain edema/infarction. | [200–202] |

NP (nanoparticles), PEG (polyethylene glycol), MCAO (transient-middle cerebral artery occlusion), TBI (traumatic brain injury), CCI (controlled cortical impact), FPI (fluid percussion injury), i.v. (intravenous), i.n. (intranasal), i.p. (intraperitoneal), MMP (matrix metallopeptidase), CBF (cerebral blood flow), TEG (tetra ethylene glycol), NO (nitrate radical), OFT (open field test), PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

5.1.1 Erythropoeitin (EPO) therapy

Previous studies with stroke aimed to enhance local delivery of erythropoietin (EPO) after neural injury; EPO is a molecule that has shown to have neuroprotective, anti-apoptotic, neurogenic, and angiogenic properties.[147–150] Previous studies cited optimal brain injury protection with elevated EPO doses beyond what is capable for systemic administration without causing adverse side effects.[151,152] Therefore, Ishii and colleagues fabricated liposome-based NPs encapsulating EPO derivatives (AsialoEP, AEPO) for intravenous injection immediately after inducing a transient stroke, middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rats.[144] This passive NP delivery of AEPO reduced infarct lesion and improved motor function compared to blank liposomes and free AEPO 24 hrs post-injection.[144] A similar study of EPO NP delivery was completed using PLGA NPs encapsulating the EPO derivative, recombinant EPO (rEPO). [153] Here, the NPs were intraperitoneally injected 1h after inducing hypoxic-ischemia in rat model. [153] NP delivery showed significant reduction in infarct volume compared to bolus injection and reduced functional deficits (21 days post-injury) with a low dose of rEPO NPs compared to free rEPO.[153] Taken together, NP delivery of EPO derivatives injected closely after injury was effective at reduced drug dosage compared to bolus not only because of the improved the blood circulation time due to drug encapsulation but also due to increased NP accumulation (passively) near the injury region. Moreover, the NP treatment was successful not only at acute time point but showed long-term functional improvements.

5.1.2 Neurotransmitter delivery

Both cerebral ischemic and brain trauma injuries initiate neuronal tissue damage by injury-induced release of endogenous neurotransmitters, including adenosine, acetylcholine and glutamate.[154–156] Adenosine, a potent neuromodulator,[156] is also a well-recognized neuroprotective molecule.[157,158] For therapeutic intervention, systemic administration of adenosine is inefficient due to its hydrophilicity, fast metabolization and rapid clearance from the bloodstream.[157–159] To overcome these limitations, Gaudin et al. fabricated nanoassemblies composed of covalently linked lipid (squalenylacetic acid) and adenosine (~120 nm).[159] Intravenous injection of these NPs either before ischemia or 2h post-ischemia after transient MCAO showed significant improvement of neurologic deficit score and reduced infarct volume compared to control groups including free drug.[159] Additionally, acknowledging that adenosine is a potent vasodilator, the study investigated the effect reperfusion by using a permanent MCAO model.[159] Adenosine NP injection 2h after permanent MCAO, not only displayed improved neurologic deficit score, but also significant reduction in infarct volume as compared to free drug. Collectively, drug delivery via NPs demonstrate improved efficacy for systemic administration with significantly improved neuroprotective effect when compared to free drug.

5.1.3 Phospholipid precursor: citicoline

Citicoline is a drug known to increase phospholipid synthesis and inhibit phospholipid degradation, restores ATPase activity and aids in the reformation of the cell wall integrity, thereby reducing secondary injuries.[146,160],[161] Although this drug is commercially available in many countries, it has not been shown to be efficacious in treating stroke and TBI in clinical trials in the US.[146,160,162] Pre-clinical rodent studies indicated that bioavailability of this drug maybe an issue and has been overlooked in the clinical studies.[162] Subsequently, researchers recently explored NP encapsulation of citicoline to improve the drug bioavailability.[146,162,163] Specifically, a liposome formulation systemically injected following focal ischemia in rats (two doses at 0 and 3h after reperfusion) significantly reduced infarction compared to same dose regime of free citicoline.[146] Interestingly, the liposome formulation also incorporated GM1 ganglioside, known to suppress complement-dependent phagocytosis of liposome, resulting in prolonged circulation time and improved brain uptake via compromised BBB compared to free citicoline (~23% versus less than 2%).[146] In summary, the liposomal formulation with GM1 ganglioside to encapsulate citicoline significantly improved the brain uptake of the drug via passive accumulation and shows potential for future clinical trials.

5.1.4 Peptidergic drug delivery: cerebrolysin

Cerebrolysin, a peptide preparation is a peptidergic drug[164] that reportedly activates neurotrophic factors, improves neuronal oxygen utilization and decreases free oxygen radical concentration.[165–167] Clinical studies have shown cerebrolysin to improve neurological outcomes in patients with acute focal ischemic stroke[165] and cognitive function in mild TBI patients;[167] however, limitations such as short half-life, poor stability and high doses required for efficacy endures.[67] Recent study used PLGA NPs (~300 nm) encapsulated with cerebrolysin for intravenous administration following a stab wound injury model. A bolus injection of free cerebrolysin reduced edema and BBB breakdown when the drug was given 30 min to 1 h post-TBI compared to untreated group.[67] In contrast to the bolus group, all NP groups administered up to 4 h post-injury showed significant reduction in edema and BBB breakdown compared to untreated group.[67]

5.1.5 Antioxidant delivery

After brain injury, excitotoxicity exacerbates metabolic failure and necrosis and also enhances the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).[25,168–170] Over production of these species leads damage of critical lipids, proteins and nucleic acids ultimately resulting in cell/tissue death. Oxidative stress after brain injury also increases the permeability of BBB via peroxidation of membrane polyunsaturated fatty acids and/or depletion of endogenous antioxidants.[19,168,170] A select few antioxidants have shown efficacy in preclinical animal models of brain injury with minimal effect in clinical trials.[25] One of the shortcomings noted in the clinical trials was the short shelf-life of antioxidants due to oxidation.[25] Encapsulation within NPs is one approach to improve capacity for radical annihilation,[171] shelf-life, bioavailability and also circumvent potentially adverse side effects of the antioxidants.[122,171–181] Micelles composed of tetraethylene glycol (TEG) bound to alpha-tocopherol (vitamin E) and ibuprofen was intravenously delivered to mice after TBI (closed head injury). Alpha-tocopherol is a lipid-soluble antioxidant and ibuprofen is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) candidate to mitigate the effects of inflammation after TBI.[122] Injecting the NPs immediately after injury (intravenous or intraperitoneal administration) resulted in NP accumulation near the injury region 36h post-injection.[122] Only the groups that received intravenous administration displayed improvement in functional behavioral assessments compared to the control group.

A new wave of antioxidant therapies utilizes material properties of the NP to serve as the antioxidant such as active polymers, carbon clusters and cerium oxides. These NP act as antioxidants by exhibiting free radical scavenging activity, decreasing ROS and RNS concentration.[182] For example, NPs composed of the oxygen reactive polymer (ORP; 8 nm) were synthesized via copolymerizing polyethylene glycol methacrylate with thioether containing monomer 2-(methylthio)ethyl methacrylate and the amine reactive monomer methacrylic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester. This ORP based NP may act as a ROS sponge to reduce ROS production after trauma.[173] ORP delivered within 15 mins post TBI showed reduced neurodegeneration at 24h post-injury in a pre-clinical mouse model.[173] Moreover, treatment with ORP reduced astrogliosis and activated microglia 7days post-TBI compared to untreated group. Additionally, passive accumulation of smaller size NPs have demonstrated prolonged access to the brain,[104] ORPs owing to their small size (8 nm) were able to successfully accumulate in the brain when injected 3h post-TBI (controlled cortical impact, CCI model). Similar active agents such as PEGylated hydrophilic carbon clusters (PEG-HCCs) have also been investigate to serve as antioxidants to detoxify radicals.[171] Here, HCCs are 30 to 40 nm long and 2 to 3 nm wide; when PEGylated, the PEG-HCCs have an estimated hydrodynamic diameter of 50 nm. A single dose of PEG-HCC was injected 80 mins post controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury and hypotension. PEG-HCC NP delivery improved the relative cerebral blood flow and normalized the oxidative radical profile compared to the vehicle group. However, there were no assessment to confirm the behavioral/functional improvements in the rat models.[171] Another materials-based antioxidant strategy employed cerium oxide NPs.[172,174,175] Two different groups have evaluated these NPs with starkly different treatment regimes following a rodent model of brain injury. One study injected a single low dose of cerium oxide NPs without any effect on cognitive deficits after injury.[174] However, a second study administered five high dose injections over 48 hours post injury and observed restoration of the endogenous antioxidants to near normal levels and reduction in macromolecular oxidative damage and improvements in cognitive function.[172] However, there was no toxicity study performed for multiple injections at high dose, which may potentially limit the translation to clinical study.

Overall, delivery of NPs using antioxidant drugs such as vitamin E or artificial antioxidants such as cerium oxide have exhibited effective therapeutic benefit in animal models via passive delivery. However, these NPs must be used with precaution to achieve desired therapeutic benefit versus any deleterious pro-oxidant effects.

5.2 Active targeted delivery

As describe above, NPs may be delivered to the brain tissue via transient dysfunction in the BBB after brain injury. However, the retention of these NPs may be enhanced by more active delivery approach such as decorating the NP surface with targeting moieties (e.g., antibodies, peptides, etc.). The section below highlights recent studies that employ active targeting NPs to treat neural injury (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of various nanoparticle for active delivery for ischemic stroke and brain trauma applications

| Platform | NP size (nm) | NP zeta (mv) | Disease model | Animal model | Injection | Conclusion | REF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic bovine serum albumin conjugated with tanshinine IIA PEGylated NPs | 118 nm | −19 mV | MCAO | Rats | i.v | Neuroprotective effects and increased accumulation in the brain with reduction in the ischemic area and inflammatory responses. | [203] |

| PEGylated lipid nps encapsulated with 3-n-butylpthalide and conjugated with Fas ligand antibody | ~60 nm | - | MCAO | Mice | i.v. | Improvement in brain injury and neurological deficits. | [77] |

| PLGA NPs with/without 800cw coating | ~200 nm | ~ −39 mV | TBI - Cryo-lesion | Mice | i.v | NPs with 800CW displayed preferential binding to intracellular proteins of cells that have lost membrane integrity. | [185] |

| Anti-HSP72 with stealth PEG immunoliposome imaging probe with citicoline | ~100 nm | - | MCAO | Rats | i.v | 30% smaller lesion volume. | [183] |

| Silica coated SPOINS used to label (EPCs) with/without magnetic field (0.3 t) | ~120 nm | −37 mV | MCAO | Mice | i.v. | Improved neurobehavioral outcome, microvessel density and VEGF expression; reduced brain atrophic volume. | [78] |

| Liposome with T7 and SHp peptide encapsulated with ZL006 | ~96 nm | −3.2 mV | MCAO | Rats | i.v | Reduced infarct area, neurlogical score and apoptosis. | [189] |

| PLGA NPs chlorotoxin, Lexiscan, NEP1 | 150 nm | −22 to −25 mV | MCAo | Mice | i.v | Reduction in infarct volume, improved survival and neurological outcomes (behavior test). | [204] |

| PLGA NPs coated with PX with BDNF encapsulation | ~ 170 nm | - | TBI - Closed head injury Weight drop | Mice | i.v. | Significantly increased BDNF delivery and improved neurological and cognitive deficits. | [191] |

| Polysorbate 80 PBCA NP HRP or EGFP | ~ 150 nm | - | FPI TBI | Rats | i.v. | HRP or EGFP delivered via PBCA NPs cross BBB and distributed near injury region. | [136] |

| PBCA NPs polysorbate 80 coated and Puerarin | ~200 nm | −7.7 mV | MCAO | Rats and Mice | i.v. | Greater drug concentration and decreased neurological deficit scored, reduced infarct volume. | [140] |

| Chitosan nanospheres conjugated with PEG with/without OX26 monoclonal antibody | ~200 nm | MCAO | Mice | i.v. | OX26 conjugated NPs could penetrate the brain whereas the OX26-free NPs could not – however this study did not show any quantitative data/statistics to validate the claim. | [205] | |

| Porous silicon NPs (PSiNPs) conjugated with targeting peptide (CAQK) loaded with siRNA against GFP | ~20 nm | - | TBI - Penetrating brain injury | Mice | i.v. | Higher accumulation with 70% silencing of GFP expression. | [184] |

| Targeted peptide from RVG, porous silicon NPs graphine oxide (GO) coating with siRNA | 170 nm | 22.2 mV | TBI - Penetrating brain injury | Mice | i.v.. | Increased (2.5 fold) delivery of siRNA via GO coated NPs compared to non coating NPs | [206] |

NP (nanoparticles), PEG (polyethylene glycol), MCAO (transient-middle cerebral artery occlusion), TBI (traumatic brain injury), CCI (controlled cortical impact), FPI (fluid percussion injury), i.v. (intravenous), PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid), BDNF (brain derived neurotrophic factor), PX (poloxamer 188), PBCA (polybutylcyanoacrylate), HRP (horse radish peroxidase), EGFP (enhanced green fluorescent protein), EPCs (endothelial progenitor cells), RVG (rabies virus glycoprotein), GFP (green fluorescent protein)

5.2.1 Target discovery and applications

The epitope/ligand selection as the basis of the targeting strategy is critical for the specificity of the NP system. Biomarkers that target the injury core or penumbra[59,77] such as cyanine dyes and Fas-ligand have been used for active NP targeting. Alternatively, novel biomarkers may be isolated using extensive proteomic study[183] or phage display biopanning[184]. For example, cyanine dyes such as IRDye 800CW reportedly target necrotic cells, since these dyes preferentially bind to intracellular proteins of cells that lack membrane integrity.[185] Cruz and group explored the targeting of PEGylated poly(lactic-co- glycolic acid) (PLGA) NPs with IRDye 800CW coating to neural injury in a cryolesion model. At acute time points there was no significant difference between the targeted and non-targeted NP groups. However, at 48 h post-injection the study reported significant increase in targeted NP accumulation/retention within the injury penumbra compared to non-targeted NPs.[185] Fas ligand (FasL) is known to play a key role in apoptosis and the persistent elevation of the ligand in ischemic damaged brain regions, makes the FasL antibody a potential candidate for targeted delivery strategy.[186] Therefore, PEGylated lipid NPs with FasL antibody conjugated to the surface and encapsulated with a neuroprotective drug (3-n-Butylphthalide) were evaluated in an ischemia stroke model.[77] The NP accumulation in the ischemic region with significant suppression in neurovascular damage in targeted NP groups compared to untargeted NP group.[77] Although the study reports improvements in neurological deficits at 24 h post injection, the improvement was only significant with respect to the vehicle group but not when compared to the untargeted NPs group.[77]

Proteomic and immunohistological study was utilized by Agulla et. al. to select the optimal biomarker to target the peri-infarct region of cerebral ischemia.[183] They isolated a protein, HSP70 that was specifically expressed at the per-infarct tissue. Anti-HSP70 antibody was developed and then conjugated to the surface of a liposomal NP loaded with citicoline (final diameter ~100 nm). The targeted NP resulted in significantly greater accumulation in the ipsilateral injury region compared to untargeted NPs. Moreover, 7 days post-injection, the targeted NP lead to a reduced lesion volume compared to the untargeted group.[183] Phage display method was used to isolate CAQK peptide to target injured brain tissue and was conjugated with NPs (CAQK-NPs).[184] The CAQK-NPs were then employed to deliver siRNA to silence green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene. Both significant levels of targeted NPs and silencing of the GFP gene occurred compared to the control group within the injury penumbra.

Largely, the studies show that although the untargeted NPs passively accumulate in the brain region at acute time points, the active targeting NPs display significantly higher (increased) retention in the injured brain tissue.

5.2.2 Targeting receptor-mediated transcytosis

Another popular approach for NP delivery is to exploit receptor-mediated transcytosis via NP decorated with corresponding peptides and antibodies to mediate BBB permeability. For example, immunoliposomes have been conjugated with BBB permeable peptides such as T7 to specifically bind to the transferrin receptor (TfR) and mediate the transport of nanocarriers across the BBB.[187,188] Taking this approach a step further, Zhao and group conjugated the T7 peptide with stroke homing peptide (SHp) on the surface of a liposome that encapsulated the neuroprotectant ZL006 for delivery after focal cerebral ischemia.[189] The authors reported efficient transport across BBB with reduced infarct area and neuronal apoptosis compared to native non-targeting liposomes encapsulated with ZL006. Furthermore, PEG coated chitosan NPs were conjugated with TfR monoclonal antibody to achieve NP permeability across BBB.[190] The NPs were loaded with a specific caspase-3 inhibitor and were administered after focal ischemia.[190] The NPs were intravenously delivered 2 h pre- or post- ischemia, and there was significant improvement due to active targeting NPs compared to untargeted NPs at 24 h post-ischemia.[190] These studies demonstrate the ability of active NP delivery via receptor-mediated transcytosis to promote higher retention post-injection compared to non-targeted NPs at extended time period.

NP coating with surfactants such as poloxamer 188, and Tween 80 on the NPs play a crucial role in drug delivery across the BBB via interaction with lipoprotein receptor on the BBB surface. In a recent study by Khalin and group PLGA NPs were used to deliver BDNF (NP-BDNF) after closed head injury in mice.[191] The NP-BDNF was also conjugated with poloxamer 188 (PX) (NP-BDNF-PX) for enhanced BBB penetration.[191] NP-BDNF-PX treatment showed significantly increased BDNF levels in the injured brain tissue as compared to other groups with/without PX/NPs. Moreover, this treatment showed significant improvements of neurological and memory deficits at day 7 post-injury compared to the control groups.[191] Therefore, surfactant coating on NPs showed improved NP delivery to the brain due to active delivery via BBB penetration. Tween coating on chitosan conjugated NIPAAM (N-isopropylacrylamide) NPs with encapsulated riluzole was investigated in a recent study.[192] These NPs were intraperitoneal injected 1h after MCAO, showed significant reduction in infarct size with reduction in immunological parameters at lower drug concentration after 24h post MCAO.[192] However, a control group without Tween 80 NP was not included and therefore the contribution of the Tween 80 coating on BBB permeability is difficult to interpret. Studies have also shown success in using a small molecule drug called Lexiscan as BBB modulator.[193,194] Particularly for NP delivery to stroke, Liang et. al. used PLGA NPs for a novel approach by combine traditional targeting delivery (via cholotoxin to target MMP-2) with an autocatalysis mechanism (via Lexiscan encapsulation).[193] After successful targeting of the NPs via cholotoxin the NPs would release Lexiscan which transiently enhances BBB permeability to allow additional NPs to enter. Study demonstrated that at 3 days post MCAO, the targeting NPs significantly increased accumulation compared to NPs without lexiscan/chlorotoxin.[193]

Overall, active targeting of NPs has demonstrated to improve retention of NPs at the injury region after brain injury using injury specific biomarkers. Moreover, NPs with BBB permeable ligands have shown to delivery enhanced amount of NPs at acute time points after injury. Coating the NPs with surfactants has also proven to be critical for BBB permeability after brain injury.

6. Neurotoxicity

Although the use of NPs therapeutics for brain injury represents a major innovative pharmacological strategy, valid concerns about NP toxicity remain.[46,59] Little is known about the behavior of NPs and their interactions with the human brain. Clinical and animal studies investigating the toxic effects of NPs on CNS are limited. Recent in vivo toxicity studies of NPs in animal models have indicated toxicity for some NPs (such as quantum dots and carbon nanotubes) but reported limited negative effects for others (such as silica coated magnetic NPs, liposomes, and iron oxides).[46,59] Neurotoxicity of NPs can occur not only due to the NP core structure but also because their surface functionalization (peptides/antibodies for active delivery) that can alter the biological response.[46,59] Although surface functionalization using surfactants/peptides can assist in NP delivery via BBB permeability, but in doing so may increase the risk to induce non-specific permeability of toxic substances.[46,59] Also, neurotoxicity may arise from NPs functionalized with cationized proteins.[46,59] Nevertheless, some NPs have passed rigorous toxicity testing for regulatory approvals and have been successfully used in the clinic.[46,59] Further investigation of the influence of the composition, size, and surface properties of NP for safe NP applications will aid in translation from preclinical to clinical applications.

7. Conclusion

Brain injury via cerebral ischemia and brain trauma involves a dynamic pathophysiology that comprises a range of processes including BBB dysfunction, excitotoxicity, ionic imbalance, ROS generation, inflammation and neuronal death. An understanding of the mechanism(s) underlying the regulation of the diseased brain is essential for development of NP based platforms. The transient BBB opening may provide an opportunity for NP strategies for clinical interventions. Successful pharmacotherapy of free drugs was limited to achieve effective concentration in the brain, which was overcome by encapsulating the drug in NP systems. Specifically, NP encapsulation of antioxidants and neurotransmitters have been utilized for improved neurological and functional outcome via passive diffusion for brain injury. Passive accumulation of artificial antioxidant NPs was also advantageous as therapeutics for brain injury. Additional approach for NP delivery for brain injury is active targeting by decorating the NPs with injury specific targeting peptides/antibodies/dyes. Strategies for enhanced NP delivery to the brain after injury stems from our current understanding of the BBB dysfunction, which is related to higher expression of specific receptors in the endothelial cells from brain capillaries. NPs can be engineered to enhance the transport of NPs though BBB by using certain ligands or surfactants on the surface of the NPs. However, a better understanding of mechanisms such as endocytosis-mediated, transcytosis-mediated, efflux-mediated NP uptake across the BBB is warranted. Such understanding of the precise NP drug delivery NP approaches will provide a breakthrough for effective brain injury treatment. Although pre-clinical studies have demonstrated the benefits of NPs for drug encapsulation, to the best of our knowledge, there is no NP formulation being currently tested in clinical trials for stroke or brain trauma. To potentially move the research to clinical settings, the neurotoxicity and the safety issues must be considered. Taken together, efficient non-invasive and brain directed therapies for brain injury can be achieved by the advancement in the NP platforms that exploits the BBB changes in concert with promising therapeutic and or imaging agents.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Amanda Witten and Cat Braithwaite for artistic rendering of the figures and the following funding sources: NSF CBET (1454282; SES), NIH NICHD (1DP2HD084067; SES), and Flinn Foundation (1976; VDK and SES).

Biographies

Dr. Sarah E. Stabenfeldt: Dr. Sarah Stabenfeldt is an Associate Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering. Sarah received her B.S. in Biomedical Engineering from Saint Louis University and her Ph.D. in Bioengineering from Georgia Institute of Technology followed by a NIH post-doctoral fellowship at Emory/Georgia Tech. Sarah leads her research team in developing regenerative medicine strategies for acute neural injury.

Dr. Vikram D. Kodibagkar: Dr. Vikram Kodibagkar is an Associate Professor at Arizona State University’s School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering. Dr. Kodibagkar received a M.Sc. in Physics from the Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai and a Ph.D in Physics from Washington University, St. Louis. Following his doctorate, he was recruited to the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center as faculty. His research interests include developing techniques for fast Magnetic Resonance Imaging of tissue hypoxia and metabolites, engineering novel MRI/optical imaging probes, and theranostics for cancer and traumatic brain injury.

References

- 1.Dash PK, Zhao J, Hergenroeder G, Moore AN. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:100. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SJ, Moon GJ, Bang OY. J Stroke. 2013;15:27. doi: 10.5853/jos.2013.15.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanekar SG, Zacharia T, Roller R. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2012;198:63. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saenger AK, Christenson RH. Clin Chem. 2010;56:21. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.133801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKay RJ. Veterinary Clinics of North America - Equine Practice. 2004;20:199. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langlois JA, Rutland-Brown W, Wald MM. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200609000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maas AIR, Stocchetti N, Bullock R. The Lancet Neurology. 2008;7:728. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O’Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom AT, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y, Assoc AH. Circulation. 2007;115:E69. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feigin VL, Barker-Collo S, Krishnamurthi R, Theadom A, Starkey N. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2010;24:485. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shlosberg D, Benifla M, Kaufer D, Friedman A. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:393. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wieloch T, Nikolich K. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2006;16:258. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Boer AG, Gaillard PJ. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:323. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silva GA. Surgical Neurology. 2005;63:301. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiff L, Hadker N, Weiser S, Rausch C. Mol Diagn Ther. 2012;16:79. doi: 10.2165/11631580-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hartmann A, Yatsu F, Kuschinsky W. Cerebral Ischemia and Basic Mechanisms. Springer Science & Business Media; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.AMES A, Wright RL, Kowada M, Thurston JM, Majno G. Am J Pathol. 1968;52:437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox DPM. Brain. 2000;123:847. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson BJ, Ronaldson PT. Adv Pharmacol. 2014;71:165. doi: 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alves JL. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2013;92:141. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hergenroeder GW, Redell JB, Moore AN, Dash PK. Mol Diagn Ther. 2008;12:345. doi: 10.1007/BF03256301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner C, Engelhard K. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99:4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alves JL. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2013;92:141. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baldwin SA, Fugaccia I, Brown DR, Brown LV, Scheff SW. Journal of neurosurgery. 1996;85:476. doi: 10.3171/jns.1996.85.3.0476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chodobski A, Zink BJ, Szmydynger-Chodobska J. Transl Stroke Res. 2011;2:492. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0125-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weber J, Slemmer J, Shacka J, Sweeney M. CMC. 2008;15:404. doi: 10.2174/092986708783497337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macdonald RL, Stoodley M. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1998;38:1. doi: 10.2176/nmc.38.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bramlett HM, Dietrich WD. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:133. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000111614.19196.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang J, Yang W, Xie H, Song Y, Li Y, Wang L. Regen Med Res. 2014;2:3. doi: 10.1186/2050-490X-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price L, Wilson C, Grant G. Blood–Brain Barrier Pathophysiology Following Traumatic Brain Injury. CRC Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandoval KE, Witt KA. Neurobiology of Disease. 2008;32:200. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang ZG, Xue D, Preston E, Karbalai H, Buchan AM. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26:298. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu W-Y, Wang Z-B, Zhang L-C, Wei X, Li L. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18:609. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pardridge WM. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:556. doi: 10.3109/13550289909021285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Swanson RA. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:137. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000044631.80210.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karve IP, Taylor JM, Crack PJ. 2015:1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Jong WH, Borm PJA. IJN. 2008;3:133. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kreuter J. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2007;331:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mudshinge SR, Deore AB, Patil S, Bhalgat CM. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2011;19:129. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanwar JR, Sun X, Punj V, Sriramoju B, Mohan RR, Zhou S-F, Chauhan A, Kanwar RK. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2012;8:399. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh R, Lillard JW., Jr Experimental and Molecular Pathology. 2009;86:215. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hans ML, Lowman AM. Current Opinion in Solid State and Materials Science. 2002;6:319. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gadhvi V, Brijesh K, Gupta A, Roopchandani K, Patel N. Research Journal of Pharmacy and Technology. 2013;6:454. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petros RA, DeSimone JM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:615. doi: 10.1038/nrd2591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi J, Votruba AR, Farokhzad OC, Langer R. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3223. doi: 10.1021/nl102184c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anselmo AC, Mitragotri S. Bioengineering & Translational Medicine. 2016;1:10. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gilmore JL, Yi X, Quan L, Kabanov AV. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2008;3:83. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9099-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gustafson HH, Holt-Casper D, Grainger DW, Ghandehari H. Nano Today. 2015;10:487. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y-N, Poon W, Tavares AJ, McGilvray ID, Chan WCW. J Control Release. 2016;240:332. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2016.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.OWENS D, III, PEPPAS N. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2006;307:93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li M, Zou P, Tyner K, Lee S. The AAPS Journal. 2016:1. doi: 10.1208/s12248-016-0010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li M, Al-Jamal KT, Kostarelos K, Reineke J. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6303. doi: 10.1021/nn1018818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang RSH, Chang LW, Yang C-S, Lin P. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology. 2010;10:8482. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2010.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Polo E, Collado M, Pelaz B, del Pino P. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2397. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mohanraj VJ, Chen Y. Trop J Pharm Res. 2006;5:561. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parveen S, Misra R, Sahoo SK. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2012;8:147. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Agarwal A, Lariya N, Saraogi G, Dubey N, Agrawal H, Agrawal GP. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:917. doi: 10.2174/138161209787582057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.De Jong WH, Borm PJA. IJN. 2008;3:133. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Masserini M. ISRN Biochem. 2013;2013:1. doi: 10.1155/2013/238428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parveen S, Misra R, Sahoo SK. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2012;8:147. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lv L, Jiang Y, Liu X, Wang B, Lv W, Zhao Y, Shi H, Hu Q, Xin H, Xu Q, Gu Z. Mol Pharmaceutics. 2016;13:3506. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumari A, Yadav SK, Yadav SC. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2010;75:1. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soppimath KS, Aminabhavi TM, Kulkarni AR, Rudzinski WE. Journal of Controlled Release. 2001;70:1. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(00)00339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCall RL, Sirianni RW. JoVE. 2013:1. doi: 10.3791/51015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen-Sela E, Teitlboim S, Chorny M, Koroukhov N, Danenberg HD, Gao J, Golomb G. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:1452. doi: 10.1002/jps.21527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dutta D, Salifu M, Sirianni RW, Stabenfeldt SE. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2016;104:688. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ruozi B, Belletti D, Sharma HS, Sharma A, Muresanu DF, Mössler H, Forni F, Vandelli MA, Tosi G. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;52:899. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeng Z. IJN. 2011:765. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Puri A, Loomis K, Smith B, Lee J-H, Yavlovich A, Heldman E, Blumenthal R. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2009;26:523. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v26.i6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schnyder A, Huwyler J. Neurotherapeutics. 2005;2:99. doi: 10.1602/neurorx.2.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Béduneau A, Saulnier P, Benoit J-P. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4947. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Levchenko TS, Rammohan R, Lukyanov AN, Whiteman KR, Torchilin VP. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2002;240:95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(02)00129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1066:29. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gabizon AA. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 1995;16:285. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2020.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Johnsson M, Edwards K. Biophysical Journal. 2003;85:3839. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74798-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.MuÈller RH, MaÈder K, Gohla S. European journal of pharmaceutics and …. 2000 doi: 10.1016/S0939-6411(00)00087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lu Y-M, Huang J-Y, Wang H, Lou X-F, Liao M-H, Hong L-J, Tao R-R, Ahmed MM, Shan C-L, Wang X-L, Fukunaga K, Du Y-Z, Han F. Biomaterials. 2014;35:530. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.09.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li Q, Tang G, Xue S, He X, Miao P, Li Y, Wang J, Xiong L, Wang Y, Zhang C, Yang G-Y. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4982. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bulte JWM, Kraitchman DL. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:484. doi: 10.1002/nbm.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Liu Z, Winters M, Holodniy M, Dai H. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2023. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang Y, Wang B, Meng X, Sun G, Gao C. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:414. doi: 10.1007/s10439-010-0151-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Karchemski F, Zucker D, Barenholz Y, Regev O. Journal of Controlled Release. 2012;160:339. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hughes GA. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2005;1:22. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liang F, Chen B. CMC. 2010;17:10. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hadinoto K, Sundaresan A, Cheow WS. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2013;85:427. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mandal B, Bhattacharjee H, Mittal N, Sah H, Balabathula P, Thoma LA, Wood GC. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine. 2013;9:474. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhang L, Chan JM, Gu FX, Rhee J-W, Wang AZ, Radovic-Moreno AF, Alexis F, Langer R, Farokhzad OC. ACS Nano. 2008;2:1696. doi: 10.1021/nn800275r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shen M, Shi X. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1596. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00072h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Di Martino A, Guselnikova OA, Trusova ME, Postnikov PS, Sedlarik V. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2017;526:380. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gulaka PK, Rastogi U, McKay MA, Wang X, Mason RP, Kodibagkar VD. NMR Biomed. 2011;24:1226. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Menon JU, Gulaka PK, McKay MA, Geethanath S, Liu L, Kodibagkar VD. Theranostics. 2013;2:1199. doi: 10.7150/thno.4812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Addington CP, Cusick A, Shankar RV, Agarwal S, Stabenfeldt SE, Kodibagkar VD. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016;44:816. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1514-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Du J, Chen Y. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2004;43:5084. doi: 10.1002/anie.200454244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Torchilin VP, Omelyanenko VG, Papisov MI, Bogdanov AA, Trubetskoy VS, Herron JN, Gentry CA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1195:11. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lu W-L, Qi X-R, Zhang Q, Li R-Y, Wang G-L, Zhang R-J, Wei S-L. J Pharmacol Sci. 2004;95:381. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fpj04001x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ernsting MJ, Murakami M, Roy A, Li S-D. Journal of Controlled Release. 2013;172:782. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Scott MD, Murad KL. Curr Pharm Des. 1998;4:423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sadzuka Y, Hirotsu S, Hirota S. Cancer Lett. 1998;127:99. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(98)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Choi HS, Liu W, Misra P, Tanaka E, Zimmer JP, Ipe BI, Bawendi MG, Frangioni JV. Nature Biotechnology. 2007;25:1165. doi: 10.1038/nbt1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nicolay K, Strijkers G, Grull H. Gd-Containing Nanoparticles as MRI Contrast Agents. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]