Abstract

Objective

In this report, we aim to describe the epidemiology of extended-spectrum cephalosporin–resistant (ESC-R) and carbapenem-resistant (CR) Enterobacteriaceae infections in children.

Methods

ESC-R and CR Enterobacteriaceae isolates from normally sterile sites of patients aged <22 years from 4 freestanding pediatric medical centers were collected along with the associated clinical data.

Results

The overall frequencies of ESC-R and CR isolates according to hospital over the 4-year study period ranged from 0.7% to 2.8%. Rates of ESC-R or CR Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae varied according to hospital and ranged from 0.75 to 3.41 resistant isolates per 100 isolates (P < .001 for any differences). E coli accounted for 272 (77%) of the resistant isolates; however, a higher rate of resistance was observed in K pneumoniae isolates (1.78 vs 1.27 resistant isolates per 100 same-species isolates, respectively; P = .005). One-third of the infections caused by ESC-R or CR E coli were community-associated. In contrast, infections caused by ESC-R or CR K pneumoniae were more likely than those caused by resistant E coli to be healthcare- or hospital-associated and to occur in patients with an indwelling device (P ≤ .003 for any differences, multivariable logistic regression). Nonsusceptibility to 3 common non–β-lactam agents (ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) occurred in 23% of the ESC-R isolates. The sequence type 131–associated fumC/fimH-type 40-30 was the most prevalent sequence type among all resistant E coli isolates (30%), and the clonal group 258–associated allele tonB79 was the most prevalent allele among all resistant K pneumoniae isolates (10%).

Conclusions

The epidemiology of ESC-R and CR Enterobacteriaceae varied according to hospital and species (E coli vs K pneumoniae). Both community and hospital settings should be considered in future research addressing pediatric ESC-R Enterobacteriaceae infection.

Keywords: Enterobacteriaceae, pediatrics, resistance

INTRODUCTION

Emerging antibiotic resistance has become a serious threat to global public health. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin–resistant (ESC-R) and carbapenem-resistant (CR) Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae are a specific growing concern because of the continual increase in rates of resistance, the rapid emergence of new resistance mechanisms, and the limited pipeline of new antibacterial agents [1, 2]. These types of resistance are often plasmid mediated and thus “transmissible.” Therefore, important public health implications exist, and enhanced infection-prevention strategies are required to prevent spread.

The rates of ESC-R and CR E coli and K pneumoniae have been increasing in North America over the past 2 decades [3–5]. Most studies have focused on bacterial isolates from adults; pediatric observations have been limited. A recent US surveillance study of susceptibility patterns among pediatric E coli, K pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis isolates from approximately 300 laboratories found increasing resistance to third-generation cephalosporins between 1999 and 2011 [6]; however, the study was not designed to characterize associated clinical and molecular features.

In this report, we aim to describe the rates of ESC-R (including extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)– and AmpC β-lactamase–producing organisms) and CR Enterobacteriaceae in patients from 4 US tertiary-care pediatric centers and to describe the epidemiological, microbiological, and molecular characteristics of the most prevalent species, E coli and K pneumoniae.

METHODS

Setting and Institutional Review

This prospective surveillance study involved 4 freestanding US children’s hospitals, referred to here as West, Midwest 1, Midwest 2, and East. Hospital characteristics, including number of beds and patient volumes (as of fiscal year 2012), are summarized in Table 1. The institutional review board at each hospital approved the study protocol.

Table 1.

Hospital Demographics, Microbiology Methods Used by Hospitals to Identify Targeted Organisms, and Frequency of Confirmed ESC-R Enterobacteriaceae According to Hospital During the Study Period

| Variable | West | Midwest 1 | Midwest 2 | East |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital demographics (fiscal year 2012) (n) | ||||

| Hospital beds | 278 | 390 | 258 | 489 |

| Hospitalizations per year | 14498 | 13649 | 15656 | 31668 |

| Outpatient clinic visits per year | 290671 | 370321 | 236575 | 947117 |

| Emergency department visits per year | 32810 | 61268 | 44967 | 93035 |

| Microbiology methods | ||||

| Automated laboratory system for bacterial identification | Vitek 2a | Vitek 2a | Phoenixb and Vitek 2a (2009–2011), Vitek 2a and MALDI-TOFc (2012) | Vitek 2a |

| Method for susceptibility testing | Vitek 2,a Kirby-Bauer disk diffusiond | Vitek 2a | Phoenixb (2009–2010), Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion (2011) | Vitek 2ae |

| 2010 CLSI breakpoints for third-generation cephalosporins implemented | February 2010 | Not implemented | February 2011 | May 2010 |

| 2011 CLSI breakpoints for carbapenems implemented | February 2011 | Not implemented | June 2011 | February 2012 |

| Frequencies of ESC-R/CR isolates confirmed by coordinating center | ||||

| No. of ESC-R/CR isolates/total no. of isolates (%) | 122/4340 (2.8) |

83/8273 (1.0) |

53/2948 (1.8) |

93/14016 (0.7) |

| No. of ESC-R/CR E coli isolates/total no. of E coli isolates (%) |

96/3021 (3.2) |

74/6668 (1.1) |

34/2163 (1.6) |

68/9947 (0.7) |

| No. of ESC-R/CR K pneumoniae isolates/total no. of K pneumoniae isolates (%) | 16/374 (4.3) |

5/582 (0.9) |

12/327 (3.7) |

19/1686 (1.1) |

| No. of ESC-R/CR K oxytoca isolates/total no. of K oxytoca isolates (%) | 3/219 (1.4) |

3/152 (2.0) |

3/77 (3.9) |

3/299 (1) |

| No. of ESC-R/CR P. mirabilis isolates/total no. of P mirabilis isolates (%) | 3/178 (1.7) |

1/362 (0.3) |

0/118 (0) |

3/1357 (0.2) |

| No. of CR Enterobacter isolates/total no. of Enterobacter isolates (%) | 4/365 (1.1) |

0/302 (0) |

4/141 (2.8) |

0/447 (0) |

| No. of CR Citrobacter isolates/total no. of Citrobacter isolates (%) | 0/105 (0) |

0/143 (0) |

0/59 (0) |

0/178 (0) |

| No. of CR S marcescens isolates/total no. of S marcescens isolates (%) | 0/78 (0) |

0/64 (0) |

0/63 (0) |

0/102 (0) |

Abbreviations: CLSI, Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; CR, carbapenem-resistant; ESC-R, extended-spectrum cephalosporin–resistant; MALDI-TOF, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight.

aVitek 2 with the advanced expert system (bioMérieux).

bBD Phoenix automated microbiology system (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

cMALDI-TOF (Biotyper, Bruker Corporation, Billerica, MA).

dKirby-Bauer disk diffusion was the only method used from April 2011 through September 2012. At other times, it was used when results generated from the Vitek II were discordant with the values and/or interpretations from the updated laboratory information system.

eThe advanced expert system was used for Vitek minimum inhibitory concentration interpretation through May 2010. After May 2010, the laboratory information system was used to interpret minimum inhibitory concentrations obtained by the Vitek system.

Subjects and Study Isolates

Candidate ESC-R or CR Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered from urine or another normally sterile site during routine clinical care of hospitalized or outpatient children <22 years of age were collected between October 1, 2009, and September 30, 2013. Candidate ESC-R Enterobacteriaceae included E coli, K pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and P mirabilis nonsusceptible (resistant or intermediate) to aztreonam, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or cefepime. Candidate CR Enterobacteriaceae included the aforementioned species and Citrobacter, Enterobacter, and Serratia spp. nonsusceptible to imipenem, meropenem, or ertapenem. Each hospital used its standard clinical microbiological methods for species identification and susceptibility testing to identify candidate study isolates. The methods used and implementation of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoint updates are listed according to hospital in Table 1. Isolates were archived at −70°C and shipped to the coordinating center quarterly.

Coordinating Center Methods for Confirmation and Characterization of Study Isolates

Overview

After arrival from participating laboratories, all candidate resistant isolates were characterized further at the coordinating center using the methods described below to confirm strain purity, species, and antibiotic-susceptibility profile, as previously described [7]. In addition, the resistance phenotype, resistance determinants, and sequence type were determined for the E coli and K pneumoniae isolates.

Identification

Study isolates were identified to the species level using the Vitek card for identification of Gram-negative organisms (GN ID card [bioMérieux]).

Antibiotic-Susceptibility Testing

Antibiotic susceptibility was determined by the disk-diffusion method. All isolates were tested for their susceptibility to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, cefazolin, cefuroxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim. The CLSI cephalosporin breakpoints recommended in 2010 [8] and the carbapenem breakpoints recommended in 2011 [9] were applied to all candidate resistant isolates to confirm resistance.

Phenotypic Characterization of ESC-R and CR Isolates

Characterizations of the class A ESBL and class C AmpC phenotypes were performed on E coli, K pneumoniae, K oxytoca, and P mirabilis isolates nonsusceptible to third-generation cephalosporins, as previously described [7]. The ESBL phenotype was characterized using paired-disk diffusion and E-tests [10, 11]. The AmpC phenotype was identified with E-test strips (bioMérieux) containing cefotetan with and without cloxacillin [12, 13]. Carbapenem resistance was also confirmed in those isolates identified as nonsusceptible to meropenem using the disk-diffusion method. For these isolates, meropenem disk diffusion was repeated, imipenem disk diffusion was performed (using 2011 CLSI breakpoints), and an ertapenem E-test was performed (using 2012 CLSI breakpoints) [9, 14]. Confirmed nonsusceptibility to carbapenems was defined as nonsusceptibility to any 1 of the 3 carbapenem agents, except in the case of P mirabilis, for which nonsusceptibility to imipenem alone was insufficient. Control strains included CLSI-recommended type strains E coli ATCC 25922 and K pneumoniae ATCC 700603, and 2 laboratory-characterized strains, an E coli strain containing blaCMY-2 and a K pneumoniae strain containing blaKPC [10].

Resistance Genotyping

Study isolates were tested by polymerase chain reaction using primer sets for genes that encode common extended-spectrum cephalosporinases, including class A CTX-M and extended-spectrum TEM and SHV, class C CMY, DHA, and FOX (Supplementary Table 1) [11, 15–17]. Because narrow-spectrum blaSHV-type ampicillinases are ubiquitous chromosomal traits in K pneumoniae, all isolates from this species were screened for the presence of extended-spectrum blaSHV variants (typically associated with IS26 insertion elements) using a combination of primers, as previously described [11, 18]. Isolates that exhibited phenotypic resistance to carbapenems were tested with primers for bla genes that encode class A (KPC), class B (IMP, VIM, and NDM), and class D (OXA-48/181–like) carbapenemases [19]. All amplicons were sequenced, and the assembly and alignment of nucleotide sequences were performed to identify all bla determinants to the variant level (eg, CTX-M-15 vs CTX-M-14), as previously described [11]. Given the high prevalence of narrow-spectrum TEM among Enterobacteriaceae, the sequencing of TEM amplicons was carried out only in ESC-R strains with no other ESC-R determinants detected.

Sequence-Based Strain Typing

To identify the pandemic-associated clonal strain types known as sequence type 131 (ST131) and clonal group 258 (CG258) among all resistant E coli and K pneumoniae isolates, respectively, polymerase chain reaction and sequencing were carried out using previously described primers for fumC and fimH for E coli or primers for tonB for K pneumoniae, as previously described [11, 20, 21]. We defined 4 fumC/fimH types (40-30, 40-22, 40–41, and 40-27) that were associated previously with strains of the globally disseminated multidrug-resistant ST131 clone [22, 23] as ST131-associated sequence types and defined K pneumoniae isolates with tonB allele 79 as likely CG258 strains [24].

Hospital-Level Data

For each study year, the hospitals provided the total number of Enterobacteriaceae isolates recovered from urine or other normally sterile sites by species (or by genus for Enterobacter and Citrobacter isolates). Isolates from hospitalized or outpatient children were included. For these denominator data, repeat isolates from a given patient were excluded if recovered within 15 days of a previous isolate. The 15-day cut point was chosen in an effort to identify isolates that represented a new infection episode. Patients were allowed to contribute same-species isolates from the same hospitalization as long as they were contributed at least 15 days apart.

Clinical Data

Demographic and clinical data were collected from the medical records using a standardized case report form. Data on complex chronic conditions expected to last at least 12 months and require frequent or specialty medical care were collected and categorized using the strategy developed by Feudtner et al [25] using International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision diagnosis codes. In addition, we added a urologic category that included neurogenic bladder and vesicoureteral reflux. Patients were characterized as likely having a urinary tract infection (UTI) if the culture was considered clinically significant (ie, met standard microbiology laboratory criteria for susceptibility testing) [26] and/or the patient had symptoms of a UTI (presence of fever, abdominal/flank pain, vomiting, change in color or odor of urine, change in continence pattern, hematuria, dysuria, or frequency/urgency).

Epidemiologic Definitions

Community-associated infection was defined as positive culture results obtained in an outpatient setting or ≤48 hours after hospital admission from an otherwise healthy patient without hospitalization in the previous year; healthcare-associated infection was defined as positive culture results obtained in an outpatient setting or ≤48 hours after hospital admission from a patient who had been hospitalized in the previous year and/or had a complex chronic condition (as described above); and hospital-associated infection was defined as positive culture results obtained >48 hours after hospital admission or ≤48 hours after hospital discharge from a patient without signs or symptoms of infection at the time of admission.

Statistical Analyses

Counts and rates of ESC-R and CR Enterobacteriaceae isolates overall, and of E coli and K pneumoniae specifically, were summarized according to hospital and year. We calculated resistance rates by dividing the number of resistant isolates by the total number of same-species isolates according to species, year, and hospital. Distributions of resistance phenotypes, molecular resistance determinants, and sequence-based strain types (only for E coli and K pneumoniae) were summarized by counts and proportions. Linear regression models were used to assess changes in rates over time and differences in average rates according to hospital or species. To compare the categorical demographic and clinical variables between species, we used the χ2 test and applied a Mantel-Haenszel approach with stratification according to hospital when the sample size was sufficiently large at each hospital.

To assess the association between various risk factors and the recovery of E coli versus K pneumoniae, we first identified a priori a list of potential risk factors, which included indwelling devices (none vs Foley or central venous catheter vs other), onset of infection (community-asssociated vs healthcare-associated vs hospital-associated), underlying conditions (urologic condition, neuromuscular condition, malignancy, and other conditions), immunosuppression, hospital, and sex. Neuromuscular and urologic conditions were chosen for inclusion in the model given their high frequency in our data set, and malignancy was chosen given its association with infection overall. For the analyses, end-stage renal disease was removed from the original urologic category and recategorized as “other” because of the difference in pathophysiology from that of other urologic conditions. We next applied a logistic regression tree approach [27] to identify which candidate variables best discriminated the 2 resistant species (Supplementary Figure 1). The variables indwelling device, onset of infection, underlying conditions, and sex provided the best discrimination between species. A multivariable logistic regression analysis was then used to examine all risk factors together. Because of overlap between the indwelling-device and onset-of-infection variables (nearly no subjects with community-acquired infection had an indwelling device), we constructed a new categorical variable by combining the indwelling-device and infection-onset categories. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.1 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Frequencies and Rates of ESC-R/CR Enterobacteriaceae According to Hospital and Over Time

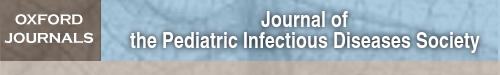

In total, 416 isolates were submitted by participating hospitals and evaluated by the coordinating center; 351 (84%) of these isolates met study criteria as ESC-R or CR. The 351 confirmed resistant isolates included 122 (35%) from West, 83 (24%) from Midwest 1, 53 (15%) from Midwest 2, and 93 (26%) from East (Table 1). The overall frequencies of ESC-R and CR isolates according to hospital over the 4-year study period ranged from 0.7% to 2.8%, and the frequencies observed across E coli, K pneumoniae, and K oxytoca species were similar to the overall frequencies. In contrast, the frequencies of ESC-R P mirabilis and CR Enterobacter spp. seemed to be lower, and no CR Citrobacter spp. or Serratia marcescens isolates were identified. Although the overall rate of ESC-R isolates did not change over time (data not shown), the 4-year average rate of resistance among E coli and K pneumoniae isolates (combined) according to hospital ranged from 0.75 to 3.41 ESC-R or CR isolates per 100 isolates (Figure 1A); the results of all between-hospital rate comparisons were statistically significant (P < .05) except the comparison between the 2 hospitals that had the lowest rates, East and Midwest 1. Although E coli accounted for the majority of ESC-R isolates across hospitals (77%), the 4-year average rate of resistance was higher among K pneumoniae isolates (1.78 vs 1.27 ESC-R or CR isolates per 100 isolates; P = .005) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Rates of extended-spectrum cephalosporin–resistant (ESC-R) E coli and K pneumoniae isolates over time according to hospital with the 2 species combined (A), according to species with the hospitals combined (B), and according to phenotype (extended-spectrum β-lactamase [ESBL] and AmpC) with the 2 species combined (C). The denominator is all isolates of the same species recovered from urine or another normally sterile site.

Clinical Factors Associated With ESC-R or CR E coli Versus K pneumoniae

The median age of the study subjects with ESC-R or CR E coli or K pneumoniae was 5 years (range, 0.1–21.7 years), and 231 (72%) were female (Table 2). Urine was the source for 280 (88%) isolates, and 278 (99%) of these isolates met criteria for likely UTI.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Information of Patients With ESC-R E coli versus K pneumoniae

| Patient Data | Total (n = 320) | E coli Isolates (n = 268) | K pneumoniae Isolates (n = 48) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 5 (0.1–21.7) (1.1–11.7) | 5 (0.1–20.6) (1.2–11.2) | 5 (0.1–21.7) (1.0–14) | .87 |

| Female sex | 231 (72) | 202 (75) | 27 (56) | .006 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 45 (15) | 41 (16) | 3 (7) | .28 |

| Race | .54 | |||

| White | 180 (59) | 151 (59) | 28 (65) | — |

| Black | 48 (16) | 41 (16) | 7 (16) | — |

| Asian | 60 (20) | 51 (20) | 8 (19) | — |

| Native American | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | — |

| Pacific Islander | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | — |

| >1 race | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Site of culture | .001 | |||

| Urine | 280 (88) | 244 (91) | 34 (71) | — |

| Blood | 27 (8) | 14 (5) | 11 (23) | — |

| Peritoneal fluid | 6 (2) | 4 (2) | 2 (4) | — |

| Bone | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | — |

| Surgical wound | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | — |

| Cerebrospinal fluid | 1 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| Onset | <.001 | |||

| Community-associated | 91 (28) | 89 (33) | 2 (4) | — |

| Healthcare-associated | 171 (54) | 145 (54) | 24 (50) | — |

| Hospital-associated | 58 (18) | 34 (13) | 22 (46) | — |

| Hospitalized (in last year) | 149 (47) | 112 (42) | 34 (71) | <.001 |

| Underlying medical condition | 210 (66) | 164 (61) | 43 (90) | <.001 |

| Medical condition categorya | ||||

| Neuromuscularb | 63 (20) | 46 (17) | 16 (33) | .03 |

| Urologicc | 117 (37) | 96 (36) | 19 (40) | .59 |

| Malignancy | 25 (8) | 16 (6) | 9 (19) | .003 |

| Other | 106 (33) | 81 (30) | 21 (44) | .09 |

| History of transplantation | 30 (9) | 22 (8) | 7 (15) | .04 |

| Immunosuppressants (in last year)d | 62 (19) | 43 (16) | 17 (35) | .002 |

| Indwelling device at time of infection | 125 (39) | 79 (29) | 43 (91) | <.001 |

| Device typea | ||||

| Central venous catheter | 60 (19) | 32 (12) | 26 (54) | <.001 |

| Foley catheter | 18 (6) | 12 (4) | 6 (13) | .04 |

| Other device | 89 (28) | 57 (21) | 29 (60) | <.001 |

Patients with both extended-spectrum cephalosporin–resistant (ESC-R) E coli and K pneumoniae identified in their first isolate (n = 4) are included in the total column but excluded from the E coli and K pneumoniae columns. Missing data are not represented or in calculations of percentages. Differences between species were evaluated using a Mantel-Haenszel approach with stratification according to hospital when the sample size was sufficiently large at each hospital. Continuous variables are reported as median (range) (interquartile range); dichotomous variables are reported as number (percentage).

aThese variables are not mutually exclusive.

bDiagnoses included in the neuromuscular category were brain and spinal cord malformations, central nervous system degeneration and disease, infantile cerebral palsy, and epilepsy.

cDiagnoses included in the urologic category were congenital urologic abnormality, neurogenic bladder, and vesicoureteral reflux.

dImmunosuppressants included antineoplastic agents, high-dose glucocorticoids (2 mg/kg for >2 weeks), tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, calcineurin inhibitors, and mycophenolate mofetil.

Subjects with ESC-R or CR K pneumoniae infection were more likely than those with ESC-R or CR E coli infection to be male (n = 21 [44%] vs 66 [25%], respectively; P = .006) and have a bloodstream infection (n = 11 [23%] vs 14 [5%], respectively; P = .001). Compared to E coli infections, K pneumoniae infections were more likely to be hospital-associated (n = 22 [46%] vs 34 [13%], respectively) and less likely to be community-associated (n = 2 [4%] vs 90 [33%], respectively) (P < .001)(Table 2); accordingly, patients with K pneumoniae infection were more likely to have an underlying medical condition (43 [90%] vs 163 [61%], respectively), an indwelling device (n = 43 [90%] vs 79 [29%], respectively), and a previous hospitalization (n = 34 [71%] vs 112 [42%], respectively) (P < .001 for all comparisons). In multivariable logistic regression, the presence of a device (eg, Foley or central venous catheter) in conjunction with onset of infection (healthcare- or hospital-associated onset vs community-associated onset) were strongly associated with K pneumoniae (P ≤ .003 for any differences) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Results From Multivariable Analyses of Factors Associated With Resistant K pneumoniae Infection Versus Resistant E coli Infection

| Variable (N = 316) | OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Interaction variable: device according to onset | ||

| No device, community-associated acquisition | Reference | — |

| No device, healthcare-associated acquisition | 3.1 (0.33–29.6) | .3 |

| No device, hospital-associated acquisition | — | — |

| Other device, community-associated acquisition | — | — |

| Other device, healthcare-associated acquisition | 26.3 (2.9–236.5) | .003 |

| Other device, hospital-associated acquisition | 36.2 (3.3–396.2) | .003 |

| CVC or Foley catheter, community-associated acquisition | — | — |

| CVC or Foley catheter, healthcare-associated acquisition | 46.7 (5.4–400.7) | <.001 |

| CVC or Foley catheter, hospital-associated acquisition | 75.7 (9.0–636.1) | <.001 |

| Neuromuscular condition | 2.1 (0.8–5.1) | .11 |

| Other underlying conditiona | 0.7 (0.3–1.4) | .27 |

| Sex | 1.6 (0.81–3.4) | .17 |

Because of interaction between the device and onset-of-infection variables, a new categorical variable was created. The addition of urologic and malignant conditions or hospital did not improve the model significantly. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CVC, central venous catheter; OR, odds ratio.

aAny underlying condition other than a neuromuscular, urologic, or malignant condition.

E coli and K pneumoniae Resistance Phenotypes and Determinants

The distribution of resistance phenotypes and determinants did not vary significantly according to hospital (data not shown). The class A ESBL resistance phenotype was present in 179 (66%) and 33 (65%) of the ESC-R E coli and K pneumoniae isolates respectively, whereas the class C AmpC phenotype was identified in 87 (32%) and 6 (12%) of these isolates, respectively, and carbapenem resistance was identified in 1 (<1%) and 9 (17%) of these isolates, respectively (Table 4). Six (2%) resistant isolates exhibited overlapping ESBL and AmpC phenotypic characteristics, whereas 3 (1%) other isolates did not exhibit any of the characteristic ESC-R or CR phenotypes described, despite nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone or ceftazidime (Table 4). The average yearly rate of the ESBL phenotype among all E coli and K pneumoniae isolates combined was higher than that of the AmpC phenotype (0.87 vs 0.40 per 100 isolates, respectively; P = .004). Although the rate of AmpC phenotype detection did not change significantly over time (P = .16), there was a statistically significant increase in the rate of ESBL phenotype detection (P = .03) (Figure 1C).

Table 4.

E coli and K pneumoniae Resistance Phenotypes and Determinants

| Phenotype or Determinant | Total (n = 324) (n [%]) | E coli Isolates (n = 272) (n [%]) | K pneumoniae Isolates (n = 52) (n [%]) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance phenotypea | <.001 | |||

| ESBL | 212 (65) | 179 (66) | 33 (63) | — |

| AmpC | 93 (29) | 87 (32) | 6 (12) | — |

| Carbapenem resistant | 10 (3) | 1 (0) | 9 (17) | — |

| ESBL and AmpC | 6 (2) | 4 (1) | 2 (4) | — |

| Undetermined | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 2 (4) | — |

| ESBL determinantsb in isolates with ESBL phenotype | 212 | 179 | 33 | — |

| CTX-M-15 | 115 (54) | 105 (59) | 10 (30) | .004 |

| CTX-M others | 71 (33) | 65 (36) | 6 (18) | .05 |

| ESBL SHV | 12 (6) | 3 (2) | 9 (27) | <.001 |

| ESBL TEM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| No ESBL determinant identified | 18 (8) | 7 (4) | 11 (33) | <.001 |

| AmpC determinantsb in isolates with AmpC phenotype | 93 | 87 | 6 | — |

| CMY-2 | 78 (84) | 76 (87) | 2 (33) | <.001 |

| DHA | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (17) | .001 |

| FOX | 4 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (33) | .003 |

| No AmpC determinant identified | 11 (12) | 10 (11) | 1 (17) | .42 |

| CRE determinantsb in isolates with carbapenem resistance | 10 | 1 | 9 | — |

| KPC | 5 (50) | 1 (100) | 4 (44) | .32 |

| IMP | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | .74 |

| VIM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| NDM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| OXA-48 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | — |

| No CRE determinant identified | 4 (40) | 0 (0) | 4 (44) | .41 |

| Other antibiotic susceptibilities | ||||

| Nonsusceptible to TMP/SMX | 213 (66) | 174 (64) | 39 (75) | .07 |

| Nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin | 177 (55) | 151 (56) | 26 (50) | .60 |

| Nonsusceptible to gentamicin | 137 (42) | 105 (39) | 32 (62) | .002 |

| Nonsusceptible to TMP/SMX and ciprofloxacin | 141 (44) | 116 (43) | 25 (48) | .32 |

| Nonsusceptible to all 3 drugs | 75 (23) | 58 (21) | 17 (33) | .05 |

Differences between species were evaluated using a Mantel-Haenszel approach with stratification according to hospital when the sample size was sufficiently large at each hospital (true for all comparisons except carbapenem resistance). Abbreviations: CRE, carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae; ESBL, extended-spectrum β-lactamase; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

aCopresence of AmpC and ESBL phenotypes was identified in 4 E coli isolates (1 with novel CMY, 1 with CTX-M-15, 1 with CTX-M-14/CMY-2, and 1 with CTX-M-15/DHA-1) and 2 K pneumoniae isolates (1 with CMY-2 and 1 with CTX-M-14/DHA-1). In addition, 3 isolates did not meet criteria for any of the phenotypes listed: 1 E coli isolate (no determinant identified) and 2 K pneumoniae isolates (1 with CTX-M-15/SHV-76 and 1 with SHV-75).

bWill total >100% because a patient could have >1 determinant identified.

In ESC-R E coli isolates, the blaCTX-M-15 resistance determinant was present in 105 (59%) of the isolates with an ESBL phenotype, and blaCMY-2 was present in 76 (87%) of the isolates with an AmpC phenotype. In contrast, in ESC-R K pneumoniae isolates, the blaCTX-M-15 resistance determinant was present in 10 (30%) of the isolates with an ESBL phenotype, and blaCMY-2 was present in 2 (33%) of the isolates with an AmpC phenotype (Table 4). Among the 10 CR isolates, 5 (50%) carried blaKPC (4 K pneumoniae and 1 E coli isolate) and 1 (10%) carried blaIMP (K pneumoniae). The remaining 4 isolates (40%, all K pneumoniae) did not have a carbapenemase determinant identified, although 2 of them had blaCTX-M-15 identified, and 1 of them had an extended-spectrum SHV.

Resistance to common representatives of non–β-lactam agents such as ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole occurred frequently in ESC-R/CR isolates (Table 4). Resistance to first-line oral agents, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and ciprofloxacin, occurred in 141 (44%) isolates overall. E coli and K pneumoniae resistance patterns were not statistically different except in the case of gentamicin, for which resistance was more frequent in ESC-R K pneumoniae isolates than in ESC-R E coli isolates (n = 32 [62%] vs 105 [39%], respectively; P = .002).

Sequence Typing of ESC-R and CR E coli and K pneumoniae Isolates

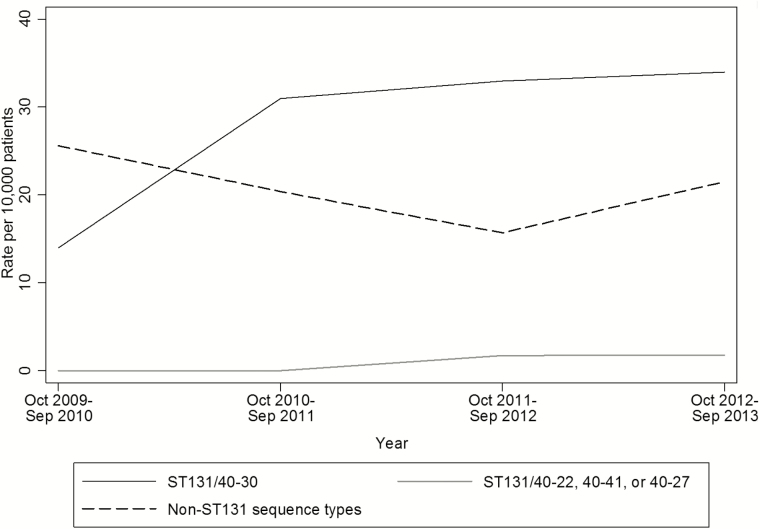

Sequence typing of E coli isolates revealed considerable clonal diversity (99 fumC/fimH sequence types were represented); the distribution of fumC/fimH sequence types did not vary significantly according to hospital (data not shown). ST131-associated fumC/fimH type 40-30 was the most common E coli profile, which accounted for 82 (30%) of the resistant E coli isolates. Other ST131-associated types, 40-22, 40–41, and 40-27, were less common; each of them represented 1% to 2.6% of ESC-R E coli isolates overall. Other relatively frequent non-ST131 types identified included 37-27, 26-5, 35-27, 11–54, and 26-26, each of which accounted for 5 to 10 (2%–4%) E coli isolates. Sequence typing of K pneumoniae isolates using tonB revealed 27 alleles overall; CG258-associated tonB allele 79 was the most common, accounting for 5 (10%) K pneumoniae isolates. Other relatively common alleles included tonB4, tonB7, tonB12, tonB16, and tonB39, each of which accounted for 4 (7.7%) isolates. The distribution of tonB alleles did not vary significantly according to hospital (data not shown).

Last, we evaluated the rate of recovery of E coli type 40-30 with blaCTX-M-15 over time. Overall, 62 (23%) of the ESC-R E coli isolates were blaCTX-M-15 type 40-30, ranging from 11% in the first year of the study to 24% to 29% during years 2 through 4. The rates of type 40-30 with blaCTX-M-15 among all E coli isolates followed similar patterns and were not statistically different over time (Figure 2) (P = .21). The rates of E coli type 40-30 blaCTX-M-15 isolates according to hospital over the 4-year study period ranged from 0.9 to 6.3 isolates per 1000 E coli isolates (P < .05 for comparisons between West, Midwest 1, and East and Midwest 2 and East).

Figure 2.

Rates of sequence type 131 (ST131)-associated fumC/fimH type 40-30, ST131-associated types 40-41, 40-22, and 40-27, and non–ST131-associated sequence types among CTX-M-15–positive E coli isolates. The denominator is all E coli isolates recovered from urine or another normally sterile site.

DISCUSSION

We performed a prospective multicenter 4-year study of ESC-R and CR Enterobacteriaceae infections in pediatric patients. Rates of resistant infections did not change significantly over the 4 years of the study, but they varied significantly according to hospital. E coli accounted for a majority of the resistant isolates (the fumC/fimH type 40-30 subclone of the E coli ST131 group was the most prevalent single-strain type detected), but K pneumoniae isolates were found to have a higher rate of resistance. Although one-third of infections caused by ESC-R or CR E coli were community-associated, infections caused by ESC-R or CR K pneumoniae were more likely to be acquired in the hospital by patients with an indwelling device. It should be noted that nonsusceptibility to 3 common non–β-lactam agents (ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) occurred in almost one-quarter of the ESC-R isolates, which indicates that therapeutic options for both enteral and parenteral treatment are quite limited for a relatively large proportion of these organisms. The multidrug resistance features of the ST131 E coli isolates that were dominant in our collection—encompassing fluoroquinolones, gentamicin, and/or TMP/trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole—are highly characteristic of the now well-described ST131 subclades H30-R and H30-Rx [28].

We found that the rates of ESC-R/CR Enterobacteriaceae varied among the hospitals. Differential use of automated systems for antibiotic-susceptibility testing and variation in the timing of new CLSI breakpoint implementation might explain some of the observed differences. Automated systems have been shown to have lower sensitivities and specificities for identifying extended-spectrum cephalosporin and carbapenem resistance than other methods of susceptibility testing [29–31]. Lower sensitivities might partly be a result of the fact that automated systems sometimes lack the dilutions necessary to classify isolates as susceptible with newly revised breakpoints [31], which is important to consider given the widespread use of automated systems for susceptibility testing in community laboratories [30, 32]. It is also possible, however, that observed differences are a result of regional epidemiology. A recent study found regional variation in third-generation cephalosporin resistance and ESBL phenotypes among Enterobacteriaceae isolates from US children between 1999 and 2011 [33].

In our study, K pneumoniae had higher rates of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporin and carbapenem than E coli. K pneumoniae has been associated with ESBL-type resistance in diverse pediatric settings [34, 35]. The E coli and K pneumoniae isolates in our study differed in other ways. Most ESC-R or CR E coli isolates were cultured from urine specimens obtained from girls (consistent with the epidemiology of UTI in general), and one-third of them met criteria for community acquisition. In contrast, ESC-R or CR K pneumoniae were almost as likely to be cultured from boys as girls and were associated more commonly with healthcare or hospital acquisition. In multivariable analyses, the presence of an indwelling device and healthcare or hospital acquisition distinguished resistant K pneumoniae infections from resistant E coli infections. Other studies revealed the importance of resistant K pneumoniae in hospital-acquired infections in children (including bloodstream infections) and infections that occur in patients with an underlying health issue [34, 36].

E coli ST131 and K pneumoniae CG258 are important epidemic clones that spread ESBL and carbapenem resistance globally [37–39]. Although we identified only 5 isolates consistent with K pneumoniae CG258, among ESC-R or CR E coli isolates, the fumC/fimH profile 40-30, which represents the H30-Rx clone of ST131 [23], was the most common type, accounting for 30% of all resistant E coli isolates. Similarly, 40-30 strains that carryied blaCTX-M-15 accounted for approximately one-quarter of all resistant E coli isolates. Although the rate of 40-30 strains that carryied blaCTX-M-15 seemed to increase early in the study, no statistically significant increase was found over the course of the study. Logan et al [33] found an increase in ESBL-phenotype E coli in US pediatric patients between 1999 and 2011, consistent with the timing of worldwide emergence of E coli ST131 carrying blaCTX-M-15 [23, 40]. Other pediatric studies have provided corroborating evidence of this strain’s rapid emergence in the early to mid-2000s [22]. Although it is possible that ESBL-producing E coli ST131 continued to increase during our study and that the magnitude of the increase was not adequately large or geographically uniform enough for us to detect, our data cannot rule out a plateau in its spread.

This study was limited by its relatively short study period, which might have been preceded by the period of most rapid emergence of ESC-R Enterobacteriaceae. In addition, it is possible that the observed differences in rates of resistance were merely a result of differences in case findings according to hospital. In addition, the isolates were collected from 4 tertiary care pediatric hospitals that used different laboratory methods; thus, our findings might not be generalizable to all pediatric settings or adult populations.

There were also limitations to our molecular typing methods. Our panel of resistance determinants did not include other resistance mechanisms, such as blaACT/MIR, that were detected recently in pediatric isolates [41]. In addition, phenotypic resistance might have been a result of mechanisms that we did not interrogate (eg, efflux pumps, porin alterations) or even novel determinants. In addition, because we used 2-locus and 1-locus genotyping methodologies rather than gold-standard 7-locus multilocus sequence typing to identify pandemic-associated clonal lineages of E coli and K pneumoniae, respectively, there is a possibility of strain misclassification; on the basis of published findings that validated the use of the 2-locus E coli scheme [21] and the specificity of tonB79 for the KPC-associated CG258-tonB79 cluster [42, 43], we are confident that our typing scheme provided a reasonable estimate of the contribution of emerging clones to pediatric multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. In this study, we did not perform high-resolution genotyping of fumC40/fimH30 or tonB79 alleles to distinguish between known subclades of ST131 [37] or CG258 [44], for which regional prevalence can vary.

In this prospective multicenter 4-year study of ESC-R and CR Enterobacteriaceae infection in pediatric patients, we found that rates of resistance varied significantly according to hospital but did not change appreciably over the study period. We also found that one-third of ESC-R E coli infections were community acquired, whereas infections caused by ESC-R K pneumoniae were more likely than those caused by E coli to be associated with indwelling devices and healthcare- or hospital-associated acquisition. The community and hospital settings need to be considered in future research and in control measures that address pediatric ESC-R Enterobacteriaceae.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Journal of The Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society online.

Supplementary Material

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Megan Fesinmeyer, PhD, for her assistance in guiding the statistical analysis and Patricia Sellenriek, MBA, for her assistance with the study. We also thank the clinical laboratory staff and research coordinators at each hospital for their assistance in collecting bacterial isolates and clinical data.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease at the National Institutes of Health (grant R01AI083413). The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential conflicts of interest. S. J. W. and J. N. have received grant salary support from the Pfizer Medical Education Committee and the Joint Commission as a site principal investigator to study the role of administrative data in antimicrobial stewardship. S. J. W. is party to a patent for a rapid molecular test to inform antibiotic selection in the treatment of UTI caused by E coli but, to date, has received no stock options or any royalties for this technology. T. Z. has received research funding from Merck and Cubist and is a consultant for Merck. All other authors: no reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Kollef MH, Golan Y, Micek ST, Shorr AF, Restrepo MI. Appraising contemporary strategies to combat multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections—proceedings and data from the Gram-negative resistance summit. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53Suppl 2:S33–55; quiz S6–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013 Accessed March 14, 2014.

- 3. Braykov NP, Eber MR, Klein EY, Morgan DJ, Laxminarayan R. Trends in resistance to carbapenems and third-generation cephalosporins among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States, 1999–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Denisuik AJ, Lagace-Wiens PR, Pitout JD, et al. Molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-, AmpC beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from Canadian hospitals over a 5 year period: CANWARD 2007–11. J Antimicrob Chemother 2013; 68Suppl 1:i57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Logan LK, Renschler JP, Gandra S, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Children, United States, 1999–2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2015; 21:2014–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Logan LK, Braykov NP, Weinstein RA, Laxminarayan R, CDC Epicenters Prevention Program Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children: trends in the United States, 1999–2011. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2014; 3:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zerr DM, Miles-Jay A, Kronman MP, et al. Previous antibiotic exposure increases risk of infection with extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase- and AmpC-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:4237–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 20th informational supplement M100-S20. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 21st informational supplement M100-S21. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Qin X, Zerr DM, Weissman SJ, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of broad-spectrum beta-lactam resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: a children’s hospital experience. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2008; 52:3909–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zerr DM, Qin X, Oron AP, et al. Pediatric infection and intestinal carriage due to extended-spectrum-cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:3997–4004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingram PR, Inglis TJ, Vanzetti TR, Henderson BA, Harnett GB, Murray RJ. Comparison of methods for AmpC beta-lactamase detection in Enterobacteriaceae. J Med Microbiol 2011; 60:715–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Japoni-Nejad A, Ghaznavi-Rad E, van Belkum A. Characterization of plasmid-mediated AmpC and carbapenemases among Iranain nosocomial isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae using phenotyping and genotyping methods. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 2014; 5:333–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 22nd informational supplement M100-S22. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Barroso H, Freitas-Vieira A, Lito LM, et al. Survey of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases at a Portuguese hospital: TEM-10 as the endemic enzyme. J Antimicrob Chemother 2000; 45:611–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Batchelor M, Hopkins K, Threlfall EJ, et al. bla(CTX-M) genes in clinical Salmonella isolates recovered from humans in England and Wales from 1992 to 2003. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:1319–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pérez-Pérez FJ, Hanson ND. Detection of plasmid-mediated AmpC beta-lactamase genes in clinical isolates by using multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:2153–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yan JJ, Wu SM, Tsai SH, et al. Prevalence of SHV-12 among clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases and identification of a novel AmpC enzyme (CMY-8) in southern Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44:1438–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17:1791–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43:4178–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Weissman SJ, Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, et al. High-resolution two-locus clonal typing of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 2012; 78:1353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weissman SJ, Adler A, Qin X, Zerr DM. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance among Escherichia coli at a US academic children’s hospital is clonal at the sequence type level for CTX-M-15, but not for CMY-2. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2013; 41:414–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, et al. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:919–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen L, Mathema B, Chavda KD, DeLeo FR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol 2014; 22:686–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics 2000; 106:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garcia LS. Clinical Microbiology Procedures Handbook. 3rd ed Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman JH. Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference and Prediction. 2nd ed New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Johnson TJ, Danzeisen JL, Youmans B, et al. Separate F-type plasmids have shaped the evolution of the H30 subclone of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. mSphere 2016; 1:pii: e00121–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garrec H, Drieux-Rouzet L, Golmard JL, et al. Comparison of nine phenotypic methods for detection of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production by Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:1048–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steward CD, Mohammed JM, Swenson JM, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of carbapenems: multicenter validity testing and accuracy levels of five antimicrobial test methods for detecting resistance in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doern CD, Dunne WM, Jr, Burnham CA. Detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) production in non-Klebsiella pneumoniae Enterobacteriaceae isolates by use of the Phoenix, Vitek 2, and disk diffusion methods. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49:1143–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thibodeau E, Duncan R, Snydman DR, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a statewide survey of detection in Massachusetts hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012; 33:954–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Logan LK, Braykov NP, Weinstein RA, Laxminarayan R. Extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in children: trends in the United States, 1999–2011. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc 2014; 3:320–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zaoutis TE, Goyal M, Chu JH, et al. Risk factors for and outcomes of bloodstream infection caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species in children. Pediatrics 2005; 115:942–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dayan N, Dabbah H, Weissman I, et al. Urinary tract infections caused by community-acquired extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing and nonproducing bacteria: a comparative study. J Pediatr 2013; 163:1417–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Folgori L, Livadiotti S, Carletti M, et al. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of multidrug-resistant, Gram-negative bloodstream infections in a European tertiary pediatric hospital during a 12-month period. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2014; 33:929–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M, et al. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014; 111:5694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kitchel B, Rasheed JK, Patel JB, et al. Molecular epidemiology of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates in the United States: clonal expansion of multilocus sequence type 258. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:3365–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, et al. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:785–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V, et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61:273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Logan LK, Hujer AM, Marshall SH, et al. Analysis of beta-lactamase resistance determinants in Enterobacteriaceae from Chicago children: a multicenter survey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60:3462–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wyres KL, Gorrie C, Edwards DJ, et al. Extensive capsule locus variation and large-scale genomic recombination within the Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal group 258. Genome Biol Evol 2015; 7:1267–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen L, Chavda KD, Mediavilla JR, et al. Multiplex real-time PCR for detection of an epidemic KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 clone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:3444–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen L, Mathema B, Pitout JD, DeLeo FR, Kreiswirth BN. Epidemic Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 is a hybrid strain. mBio 2014; 5:e01355–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.