Abstract

Context

Accumulation of brain iron is linked to aging and protein-misfolding neurodegenerative diseases. High iron intake may influence important brain health outcomes in later life.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review was to examine evidence from animal and human studies of the effects of high iron intake or peripheral iron status on adult cognition, brain aging, and neurodegeneration.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, Scopus, CAB Abstracts, the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, and OpenGrey databases were searched.

Study Selection

Studies investigating the effect of elevated iron intake at all postnatal life stages in mammalian models and humans on measures of adult brain health were included.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted and evaluated by two authors independently, with discrepancies resolved by discussion. Neurodegenerative disease diagnosis and/or behavioral/cognitive, biochemical, and brain morphologic findings were used to study the effects of iron intake or peripheral iron status on brain health. Risk of bias was assessed for animal and human studies. PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews were followed.

Results

Thirty-four preclinical and 14 clinical studies were identified from database searches. Thirty-three preclinical studies provided evidence supporting an adverse effect of nutritionally relevant high iron intake in neonates on brain-health-related outcomes in adults. Human studies varied considerably in design, quality, and findings; none investigated the effects of high iron intake in neonates/infants.

Conclusions

Human studies are needed to verify whether dietary iron intake levels used in neonates/infants to prevent iron deficiency have effects on brain aging and neurodegenerative disease outcomes.

Keywords: brain aging, iron nutrition, iron supplementation, protein-misfolding neurodegenerative diseases

INTRODUCTION

Iron proteins have key roles in normal brain function and the processes of brain development, including neurogenesis, myelination, synaptic development, and energy and neurotransmitter metabolism.1–3 The large amount of iron required to perform these functions is acquired from blood, mainly during periods of rapid brain growth.4 In adult life, iron uptake by the brain still occurs, though at levels significantly lower than those during development.5 Iron levels in the brain can be altered by peripheral iron levels and iron nutrition. Effects of iron nutrition on the brain have been studied extensively in iron deficiency, the leading nutrient deficiency worldwide.6 Iron deficiency during both development and adulthood results in diverse effects on neural function.7–9 In contrast, the effects of high peripheral iron status on the brain are poorly understood. The widespread use of iron-fortified foods, such as milk replacers, other beverages, and solid foods, as well as iron supplements has decreased the prevalence of deficiency in all age groups in many populations. However, iron-augmented diets also have the potential to increase iron intake above levels needed to prevent deficiency.10

Brain aging and protein-misfolding neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis share some common mechanisms.11 Older age is the greatest risk factor for the accumulation of misfolded proteins that typifies the earliest stages of Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease.12 Therefore, Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease may represent pathologic extensions of normal processes of brain aging. Protein misfolding, protein accumulation, and neurodegeneration are also core features of Huntington disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.13,14 Accumulation of iron in the brain occurs with human aging, and iron levels correlate with cognitive function.15,16 Iron accumulation in the brain also occurs with Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.17–20 Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis most commonly manifest as sporadic diseases.11 They are modeled in mice by mimicking the less-common genetic forms of the human disease and/or by using toxicants.21–23 Huntington disease is caused by a single gene, and several genetic mouse models exist.24

There is evidence from human and animal studies that iron dysregulation is one factor that contributes to the neurodegeneration associated with Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, Huntington disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.25 In health, iron homeostatic mechanisms maintain not only appropriate iron absorption and tissue levels but also cellular and subcellular location and molecular associations. Dysregulation of these processes results in increased production of reactive oxygen species, resulting in molecular damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cell death.26 Despite evidence of a contributory role of iron in brain aging and neurodegeneration, the role of elevated iron intake as a modifier of these processes is poorly understood.15–20 Given the increasing life expectancy and the resulting increased prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases,11 it is particularly important to understand the effects of high iron intake at various life stages on brain aging.

Recommended Dietary Allowances for iron have been developed to prevent iron deficiency, and upper limits were established to avoid short-term adverse effects.27 Possible effects of long-term iron intake above the Recommended Dietary Allowance on cognition, brain aging, and neurodegenerative processes are not understood. Furthermore, there is evidence that some populations are iron replete and have elevated iron stores.28 The aim of this study was to use the methods of systematic review to investigate the effects of high iron intake or high peripheral iron status on adult cognition and outcomes of protein-misfolding neurodegenerative diseases in both animal models and humans. The findings support a role of high iron intake as a negative modifier of brain health in adults. They also highlight gaps in understanding both the mechanisms involved and the translatability of findings in animal models to humans.

METHODS

Review protocol

The systematic review was undertaken in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.29 A checklist ensuring adherence to PRISMA guidelines is shown in Table S1 in the Supporting Information online. A written protocol was not used.

Information sources

The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE, Scopus, CAB Abstracts, the Cochrane Central Register of Clinical Trials, and OpenGrey. A computerized literature search was conducted to identify studies that had been published up to June 28, 2016. Search strategies are shown in Appendix S1 in the Supporting Information online.

Study eligibility criteria

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria and research questions were developed using the PICOS (population, intervention, comparators, outcome, study design) model. Included were studies investigating the effect of elevated iron intake at all postnatal life stages in mammalian models and humans on measures of adult brain health. Neurologic status in animal models is evaluated using a number of outcomes that include cognitive testing; biochemical measurement of markers linked to neurodegeneration, such as brain iron accumulation, neurotransmitter levels, and oxidative stress markers; and brain morphometry. Therefore, animal studies with diverse outcome measures were included. Human studies included were those that estimated former or current levels of iron intake or peripheral measures of iron status and their effect on brain iron, cognition, and/or the onset of neurodegenerative disease in adults. Details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICOS criteria for inclusion and exclusion of studies

| Category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Participants |

|

|

| Intervention |

|

|

| Comparator |

|

None |

| Outcomes |

|

Animal and human studies: outcomes measured in preadults |

| Study design |

|

Meta-analyses, reviews, gray literature, short communications, abstracts, and case reports |

Assessment of risk of publication bias in preclinical studies

Comparing the number of studies reporting negative findings in the unpublished versus the published literature is one way to assess publication bias. Risk of publication bias was assessed by one author (S.A.). The Society for Neuroscience’s online database is a collection of abstracts presented at annual meetings; the years 2007–2015 were searched. Relevant abstracts were evaluated for the presence of positive or negative findings but were not included as part of the review. Permission was obtained from the Society for Neuroscience to access this private database.

Risk of bias

The quality of the included papers was assessed at the study level. For animal studies, 7 indicators of quality adapted from the National Research Council’s Institute for Laboratory Animal Research were used30,31: (1) random allocation of treatment, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding, (4) stated inclusion/exclusion criteria, (5) test animal details, (6) every animal accounted for, and (7) conflict of interest statement and funding source. Human cohort and case–control studies were analyzed using tools from the Critical Appraisal Skills Program, while cross-sectional studies were assessed using tools modified from those recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.32 The criteria were assessed independently by two reviewers (S.A. and J.H.F.); discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

Study characteristics and data were extracted and evaluated by two authors independently (S.A. and J.H.F.), with discrepancies resolved by discussion. Meta-analysis was not possible because of the heterogeneous nature of the studies and the varied outcomes. Papers were grouped into 4 themes: preclinical studies of the effect of high iron intake on outcomes related to behavior and brain aging (Table 2)33–51; preclinical studies of the effect of high iron intake on outcomes related to neurodegenerative disease (Table 3)52–66; human nutrition studies assessing the association between iron intake and brain outcomes (Table 4)67–72; and human studies assessing the association between peripheral iron status and brain outcomes (Table 5).73–80 Qualitative synthesis of the included studies was completed within and across the 4 themes. All findings reported in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5 are statistically significant unless otherwise stated.

Table 2.

Preclinical studies evaluating the effect of high iron intake on outcomes related to behavior and brain aging

| Reference | Sex/strain/species | Iron form and dosage rangea | Age at iron supplementation and at outcome measurement | Bias assessmentb | Major effects of iron supplementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fredriksson et al. (1999)41 | Male NMRI mice | Ferrous succinate; 3.7–37 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Supplementation produced deficits in spontaneous activity and spatial learning. Iron levels in basal ganglia were increased 22%–58%. No effect on frontal cortical iron |

| Fredriksson et al. (2000)42 | Male NMRI mice | Ferrous succinate; 7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation on days 3–5 and 10–12 resulted in (1) deficits in spontaneous activity and spatial learning and (2) a 26%–48% increase in basal ganglia iron |

| Isacc et al. (2006)43 | Male C57 BL/6 mice | Ferrous succinate; 7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron-supplemented mice had decreases in brain phosphatidyl choline and sphingomyelin levels |

| de Lima et al. (2005)49 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation of iron on days 12–14 (1) impaired object recognition by ≈36% and (2) increased oxidative stress in hippocampus and substantia nigra |

| Miwa et al. (2011)51 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation increased expression of the apoptosis markers prostate apoptosis response-4 and caspase-3 protein at 3 mo but decreased expression at 24 mo |

| Fernandez et al. (2011)39 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron supplementation induced mild astrocytosis in hippocampus at 3 mo and in striatum and substantia nigra at 24 mo |

| Schroder et al. (2001)46 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 2.5–30.0 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation resulted in (1) dose-dependent deficits in radial arm maze learning and (2) a 46%–92% increase in substantia nigra iron content |

| Figueiredo et al. (2016)40 | Male Wistar rats | Carbonyl iron; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, Ld, U, L, U, L | Iron supplementation (1) impaired emotionally motivated behavior and recognition memory and (2) increased hippocampal protein ubiquitination |

| Dornelles et al. (2010)38 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation changed expression of mRNA encoding genes involved in iron homeostasis in an age- and brain-region-specific manner |

| de Lima et al. (2005)35 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, Ld, U, L, U, Lc | Monoamine oxidase inhibition protected against behavioral effects of iron supplementation |

| Budni et al. (2007)34 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Monoamine oxidase inhibition decreased iron supplementation–induced oxidative stress in substantia nigra and hippocampus |

| de Lima et al. (2008)37 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, Ld, U, L, U, Lc | Type 4–specific phosphodiesterase inhibition protected against cognitive effects of iron supplementation |

| de Lima et al. (2007)36 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron chelation with desferoxamine protected against behavioral effects of iron supplementation |

| Rech et al. (2010)45 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | No significant effect of neonatal iron supplementation on motor activity or novel object recognition |

| Fagherazzi et al. (2012)50 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous carbonyl; 10 mg/kg |

|

L, U, Ld, U, L, U, Lc | Cannabidiol protected against deleterious effects of neonatal iron supplementation |

| da Silva et al. (2014)47 | Male Wistar rats | Iron carbonyl; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, L | Cannabidiol normalized cortical caspase-3, synaptophysin, and mitochondrial fission dynamin-1-like protein |

| Perez et al. (2010)44 | Male Wistar rats | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation impaired long-term object recognition (≈28%) and decreased striatal acetylcholinesterase activity (≈27%) |

| Silva et al. (2012)48 | Male Wistar rats | Iron carbonyl; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, Ld, U, L, U, Lc | Supplementation decreased object recognition memory (≈29%). Iron-induced changes in histone acetylation in hippocampus were rescued with butyrate |

| Lavich et al. (2015)33 | Male Wistar rats | Iron carbonyl; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, Ld, U, L, U, L | Supplementation decreased novel object recognition (≈32%) and impaired mitochondrial dynamics. Effects of iron were rescued with the antioxidant sulforaphane |

Abbreviations: H, high risk of bias; L, low risk of bias; U, unclear risk of bias.

aIron was delivered by gavage.

bLeft to right: random allocation of treatment, concealment of allocation, blinding, inclusion/exclusion criteria, test animal details, every animal accounted for, and conflicts of interest and funding sources reported.

cOnly funding information was reported.

dOnly behavioral studies were blinded.

Table 3.

Preclinical studies evaluating the effect of high iron intake on outcomes related to neurodegenerative disease

| Reference | Sex/strain/species/ disease modeled | Iron form and dosagea | Age(s) at supplementation and at outcome measurement | Bias assessmentb | Major effects of iron supplementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fredriksson et al. (2001)62 | Male C57BL/6 mice; PD | Ferrous succinate; 7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron supplementation increased basal ganglia iron by 72%. Supplementation and adult neurotoxic MPTP treatment potentiated the depletion of basal ganglia dopamine |

| Fredriksson et al. (2003)60 | Male C57BL/6 mice; PD | Ferrous succinate; 2.5–7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Iron supplementation increased basal ganglia iron up to 102%. N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist MK801 with L-DOPA partly rescued motor effects of iron supplementation |

| Fredriksson & Archer (2003)52 | Male NMRI and C57BL/6 mice; PD | Ferrous succinate; 2.5–37 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, U, U, Lc | Iron supplementation increased basal ganglia iron by 58% and decreased motor activities. MPTP potentiated effects of neonatal iron supplementation |

| Kaur et al. (2007)63 | Male C57BL/6 × D2 mice; PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron supplementation decreased striatal dopamine by up to ≈44%, decreased dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra by up to ≈29%, and enhanced the neurotoxic effects of MPTP |

| Peng et al. (2007)65 | Male C57BL/6 mice; PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Iron supplementation decreased dopaminergic cells at 24 mo by ≈25%; the herbicide paraquat potentiated this effect; a superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetic provided some protection |

| Archer & Fredriksson (2007)54 | Male C57/BL6 mice; PD | Ferrous succinate; 7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Iron supplementation increased basal ganglia iron by ≈67%. Neuroleptic agents modulated behavioral effects of iron |

| Fredriksson & Archer (2006)61 | Male C57/BL6 mice; PD | Ferrous succinate; 7.5 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Neuroleptic agent haloperidol modulated the behavioral effects of iron supplementation |

| Wang et al. (2014)53 | Male Sprague-Dawley rats; PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron supplementation reduced motor activity and decreased striatal dopamine by ≈38%. Inhibition of sirtuin 2 provided some protection |

| Peng et al. (2010)64 | Male mutant α-synuclein mice (C57BL/ 6 strain); PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Interaction between mutant α-synuclein and iron + paraquat combination treatment promoted loss of dopaminergic neurons |

| Dal-Pizzol et al. (2001)58 | Male Wistar rats; PD | Ferrous succinate; 7.5–15 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, H | Neonatal iron supplementation increased substantia nigra lipid peroxidation by ≈48%–66% |

| Chen et al. (2015)57 | Male/female Sprague-Dawley rats; PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, L | Iron supplementation decreased motor activity, striatal dopamine (≈35%), and substantia nigra glutathione (≈40%) and increased nigral lipid peroxidation (≈100%) |

| Billings et al. (2016)56 | Male α-synuclein transgenic mice (C57BL/6 strain); PD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, L, U, Lc | Iron supplementation promoted loss of dopaminergic neurons in wild-type mice by ≈30% but not in mutant α-synuclein transgenic mice |

| Fernandez et al. (2010)59 | Male AβPP/PS1 transgenic mice; AD | Ferrous succinate; 10 mg/kg |

|

U, U, U, U, U, U, L | Iron supplementation increased astrocytosis in the cerebral cortex of transgenic and wild-type mice. No effect of iron on amyloid plaques |

| Berggren et al. (2015)55 | Female R6/2 mice (B6/CBA stain); HD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg for neonates, 500 mg/kg for adults |

|

Ld, U, Le, U, L, U, Lc | Neonatal iron supplementation increased the oxidative stress marker oxidized glutathione (32%–53%) and neuronal atrophy (13%–15%) in HD but not in wild-type brains. There was no effect of iron supplementation during adult life |

| Berggren et al. (2016)66 | Female YAC128 HD mice (FVB strain); HD | Iron carbonyl; 120 mg/kg for neonates, 500 mg/kg for adults |

|

Ld, U, Ue, U, L, U, L | Neonatal iron supplementation promoted striatal neuronal atrophy in HD mice (19%) but not in wild-type littermates. There was no effect of iron supplementation during adult life |

Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; H, high risk of bias; HD, Huntington disease; L, low risk of bias; L-DOPA, L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine; MPTP, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine; PD, Parkinson disease; U, unclear risk of bias.

aIron was delivered by gavage to neonates and in feed to adults.

bLeft to right: random allocation of treatment, concealment of allocation, blinding, inclusion/exclusion criteria, test animal details, every animal accounted for, and conflicts of interest and funding sources reported.

cOnly funding information was reported.

dWhole litters were randomized to receive iron supplementation.

eOnly histopathology studies were blinded.

Table 4.

Human nutrition studies assessing the association between iron intake and brain outcomes

| Reference | Study design | Population | Evaluation of dietary iron and outcomes | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al. (1999)72 | Case–control | 103 newly diagnosed PD patients and 156 controls; WA, USA | In-person interview about diet, covering most of adult life. Risk of PD | Iron intake was not related to increased PD risk |

| Powers et al. (2003)71 | Case–control | 250 newly diagnosed PD patients and 388 age- and sex-matched controls; WA, USA | In-person interview about diet, covering most of adult life. OR for risk of development of PD for each quartile of dietary factor | Subjects in highest quartile of iron intake had increased risk of PD compared with those in lowest quartile (OR 1.7) |

| Powers et al. (2009)70 | Case–control | 420 patients (median age 69 y) and 560 age-, sex-, and ethnicity-matched controls (median age, 71 y); USA | In-person interview about diet, covering most of adult life. Logistic regression used to determine OR for the development of PD for each level of dietary factor | Men in highest quartile of iron intake had increased risk of PD compared with those in lowest quartile (OR 1.82) |

| Logroscino et al. (2008)69 | Cohort | 47 406 men and 46 947 women, all health professionals; USA | FFQ every 4 y of study. Outcome of PD as determined by neurologist | Increased intake of nonheme iron but not total iron is a risk for PD (relative risk = 1.27 and 1.1, respectively) |

| Hernandez Mdel et al. (2015)68 | Cohort | 1063 healthy, older, community-dwelling men and women, mean age 73 y; UK | Self-reported food questionnaire validated in older adults. Brain iron deposits determined by MRI in brainstem, white matter, thalamus, basal ganglia, and cortex. Blood iron markers ferritin and transferrin determined | Iron intake did not correlate with blood or brain iron measurements. Brain iron deposits did not correlate with blood iron measurements |

| Hagemeier et al. (2015)67 | Cohort | 190 healthy men and women, mean age 43 y, USA | Historic (3 y) nutritional questionnaire assessing consumption of iron, calcium, vegetables, dairy, and red meat. Brain iron determined by MRI in basal ganglia, thalamus, and substantia nigra | Trend toward increased brain iron with iron supplementation (P = 0.075). Effects were dependent on sex |

Abbreviations: FFQ, food frequency questionnaire; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OR, odds ratio; PD, Parkinson disease.

Table 5.

Human studies assessing the association between peripheral iron status and brain outcomes

| Reference | Study type | Population | Peripheral iron measures and brain outcome(s) | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al. (2008)79 | Cross-sectional | 2000 men and women, >65 y, rural areas; China |

|

Plasma iron was not correlated with cognitive scores |

| Lam et al. (2008)80 | Cross-sectional | 1451 men and women, all ambulatory, mean age 75 y; USA |

|

Low and high (men) or high (women) plasma iron associated with poorer performance in a battery of cognitive tests |

| Milward et al. (2010)77 | Cohort | 800 community-dwelling adults, >60 y; Australia |

|

No relationships found between iron measures and cognitive scores |

| Schiepers et al. (2010)78 | Cohort | 818 adults, 50–70 y (mean age 60 y); Netherlands |

|

Peripheral iron measures were not associated with cognitive outcomes |

| Umur et al. (2011)75 | Cross-sectional | 87 nursing home residents, >65 y, both sexes, no neurologic diagnoses; Turkey |

|

Mild CI was associated with significantly higher serum iron (98%), ferritin (58%), and transferrin saturation (107%) |

| Mueller et al. (2012)76 | Case–control | 19 controls, 11 cases of stable mild CI, 7 cases of progressive CI, and 19 cases of early dementia; mean age ≈78 y; USA |

|

Ratio of serum copper to nonheme iron increased during the progression from mild CI to Alzheimer disease. No change in nonheme iron |

| Andreeva et al. (2013)74 | Cohort | 4959 men and women, 35–60 y; France |

|

Lower serum ferritin was associated with better outcomes of some cognitive measures in pre- and perimenopausal women |

| Blasco et al. (2014)73 | Cross-sectional | 23 obese and 20 nonobese individuals, both sexes, mean age ≈49 y; Spain | Regional liver and brain iron measured by MRI R2* relaxation | Obese individuals had significantly increased regional liver and brain iron load |

Abbreviations: CI, cognitive impairment; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

RESULTS

Description of the included studies

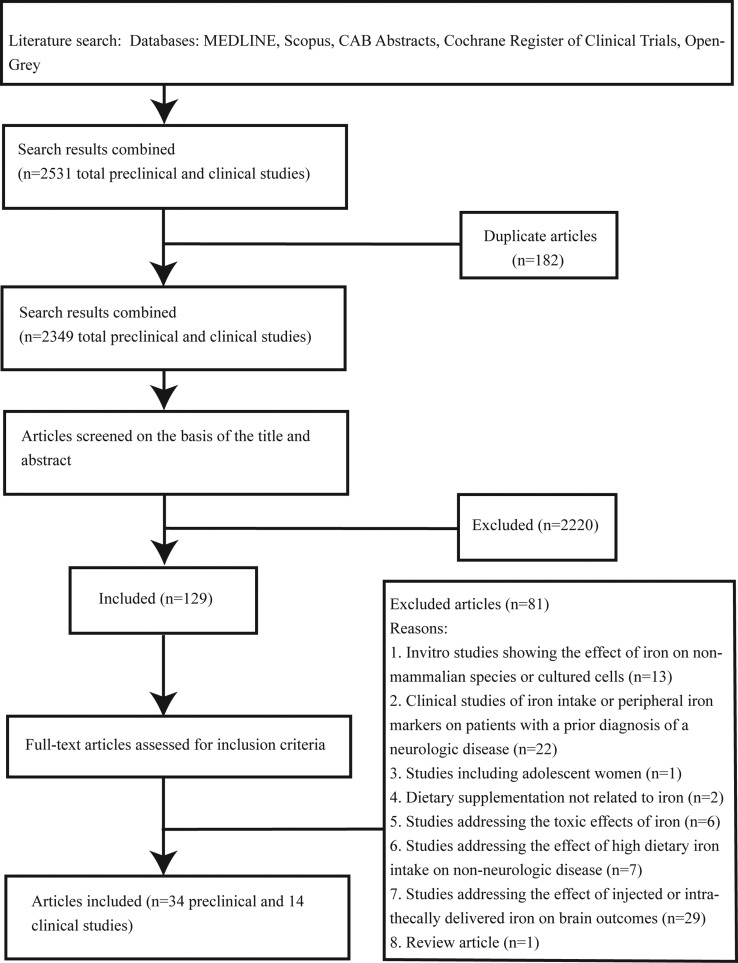

A PRISMA flow chart showing papers included and excluded at each step is shown in (Figure 1). A total of 2531 potentially relevant articles were identified. After screening titles and abstracts, 129 papers were identified for full-text evaluation. After reviewing, 81 papers were excluded. Of the 48 included papers, 34 described preclinical studies. Nineteen of these focused primarily on behavioral and age-related outcomes (Table 2), and 15 focused on outcomes related to neurodegenerative processes (Table 3). Fourteen studies were conducted in humans: 6 assessed associations between iron nutrition and brain outcomes (Table 4), and 8 assessed associations between peripheral iron status and brain outcomes (Table 5).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search process.

Assessment of risk of publication bias

After searching meeting abstracts from 9 years of the Society for Neuroscience’s database, 5 studies were found that addressed the role of elevated nutritional iron intake in neurodegenerative processes, all in animal models. All 5 abstracts described adverse effects of elevated iron intake on brain outcomes.

Assessment of risk of bias in the included studies

Assessments of preclinical studies are presented in Tables 2 and 3. Assessments of clinical studies are presented in Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6.

Risk-of-bias assessment for human studies assessing associations between iron nutrition and brain outcomes

| Reference | Was the research question focused? | Were appropriate methods used? | Was case or cohort recruitment acceptable? | Was control recruitment acceptable? | Did iron intake estimates minimize bias? | Were outcomes measured to minimize bias? | Were confounding factors accounted for? | Was subject follow-up complete? | Are the key results precise? | Are the results believable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson et al (1999)72 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | No | Yes |

| Powers et al (2003)71 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Powers et al (2009)70 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Logroscino et al (2008)69 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hernandez Mdel et al (2015)68 | Yes | Noa | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hagemeier et al (2015)67 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable for study.

aThe timing and the period of dietary intake analysis were not optimal. Unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 7.

Risk-of-bias assessment for human studies assessing associations between peripheral iron status and brain outcomes

| Reference | Was the research question focused? | Were appropriate methods used? | Was case or cohort recruitment acceptable? | Was control recruitment acceptable? | Was iron status estimated to minimize bias? | Were outcomes measured to minimize bias? | Were confounding factors accounted for? | Was subject follow-up complete? | Are the key results precise? | Are the results believable? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gao et al (2008)79 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Lam et al (2008)80 | Yes | Yes | Ua | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Milward et al (2010)77 | Yes | Ub | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schiepers et al (2010)78 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Umur et al (2011)75 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes |

| Mueller et al (2012)76 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Noc |

| Andreeva et al (2013)74 | Yes | Ub | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Blasco et al (2014)73 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Nod |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable for study; U, unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria.

aInclusion and exclusion criteria unclear.

bLack of controls to measure cognition at baseline.

cSmall group sizes (n = 18–19).

dSmall group sizes (n = 20–23).

Preclinical studies of the effect of high iron intake on behavior, brain aging, or neurodegeneration in neonates or adults

Fifteen studies used a mouse model and 19 a rat model. Five of the studies assessed the effect of elevated iron intake in genetic models of adult-onset neurodegenerative disease,55,56,59,64,66 while the remainder studied aging or neurodegenerative processes in wild-type animals. All studies assessed the effect of elevated neonatal iron intake. Levels of daily iron supplementation ranged from 2.5 to 120 mg/kg over a period of 3 to 8 days. All studies except one45 provided evidence of adverse effects of increased neonatal iron intake on neurologic outcomes. Many of the studies assessed behavioral outcomes only. Sixteen studies evaluated motor outcomes such as open-field and/or rota-rod endurance. Of these, 13 found altered motor behaviors,41–43,46,52–57,60–62 and 3 did not.33,45,66 Results from memory-based tests such as novel object recognition and/or radial-arm maze were presented in 13 studies.33,35–37,40–42,44–46,48–50

Brain regional biochemical analyses in the 34 preclinical studies most frequently investigated oxidative stress, neurochemical markers, or iron levels. Markers of brain oxidative stress, including malondialdehyde and protein carbonyls, were increased in 9 studies34,49,55–58,63–65; the 1 study that assessed glutathione levels found no change.66 Six studies assessed the effects of neonatal iron intake on brain neurochemistry outcomes. Three of these studies reported decreased striatal dopamine in adult animals,53,57,63 while 2 found no effect on dopamine.60,62 One study demonstrated decreased striatal acetylcholinesterase activity,44 and another found no effect on striatal serotonin.57 Ten studies reported increased brain iron after neonatal supplementation.41,42,46,52,54,56,60–63 Iron levels were elevated in the substantia nigra in 3 of 3 studies, in the basal ganglia in 6 of 7 studies, and in the cerebral cortex in 1 of 8 studies. Two studies found no effect of neonatal iron supplementation on iron levels in the striatum and cortex.55,66 Six studies used quantitative pathology to evaluate morphometric changes in the brain; these demonstrated significantly decreased neuronal numbers or neuronal cell body atrophy in specific brain regions.55,56,63–66 Overall, significant adverse effects of neonatal iron intake on morphologic or biochemical outcomes in specific brain regions were found in the substantia nigra (11 of 11 studies), the basal ganglia (16 of 18 studies), the hippocampus (11 of 12 studies), and the cerebral cortex (6 of 13 studies). Two studies, in addition to assessing the effects of increased iron intake in neonates, also evaluated the effect of elevated iron intake in adult life; no effects in young adult or aged wild-type and Huntington disease mice were found.55,66

Human studies assessing the correlation between iron nutrition or iron status markers and brain outcomes

Fourteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria in assessing the potential correlation between iron nutrition or peripheral markers of iron nutrition and brain-related outcomes. Six studies had the primary purpose of examining the association between estimates of iron intake and brain iron accumulation or risk of Parkinson disease.67–72 Of these, 2 cohort studies looked for associations between iron intake and brain iron deposits. One was a large study in the United Kingdom that failed to find a correlation between recent iron intake and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measures of brain iron deposition in healthy older individuals.68 Another smaller study in the United States in middle-aged individuals demonstrated a trend (P = 0.075) toward increased MRI-measured brain iron with iron supplementation.67 Four studies investigated possible associations between iron intake and Parkinson disease.69–72 Three of these had a case–control design and recruited study subjects from the state of Washington, USA. The initial smaller study did not find an association between iron intake over most of adult life and the risk of Parkinson disease.72 Two subsequent larger studies provided some evidence of an association between increased iron intake and risk of Parkinson disease.70,71 The fourth study had a cohort design and was very large (94 353 subjects).69 The authors concluded that increased nonheme iron intake is a risk factor for Parkinson disease, especially when ascorbate deficiency is present.

Eight studies had the primary purpose of determining the presence of associations between peripheral iron status and cognitive or other brain outcomes.73–80 Four of these had a cross-sectional design.73,75,79,80 Three of these reported significant associations of iron levels with brain outcomes.73,75,80 One large study of 1451 older individuals in the United States reported that high plasma iron levels correlated with poorer cognitive outcomes in both men and women.80

A much smaller study of 87 nursing home residents in Turkey reported that high serum iron, ferritin, and transferrin saturation were correlated with mild cognitive impairment.75 Another small Spanish study of 23 obese and 20 nonobese middle-aged individuals found that MRI-measured brain and liver iron was elevated in obese individuals.73 One study of 2000 elderly individuals from rural areas of China reported no correlation between plasma iron and cognitive scores.79 Three studies used a cohort design.74,77,78 A study of 800 older adults in Australia found no correlation between serum iron, transferrin saturation, or ferritin levels and cognitive outcomes.77 One French study of 4959 middle-aged individuals reported associations between lower serum ferritin and better cognitive outcomes, but only in pre- and perimenopausal women.74 A Netherlands-based study of 818 middle-aged and older individuals found no evidence of an association between peripheral measures of iron and cognitive performance.78 Finally, a case–control study of 37 older individuals in the United States found that serum nonheme iron did not increase during the progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease.76

DISCUSSION

This systematic review examined evidence from animal and human studies that investigated whether high iron intake or markers of iron status correlated with cognitive decline or the onset/progression of neurodegenerative disease. Almost all the animal studies assessed the effects of elevated iron intake in neonatal life on outcomes in early to late adult life. These studies overwhelmingly demonstrated adverse effects of high neonatal iron intake on diverse behavioral, brain morphologic, and biochemical outcomes. In striking contrast, none of the human studies assessed the effects of high iron intake in early life on adult cognitive or brain iron outcomes.

There is substantial evidence that early-life environmental factors, including nutrition, influence brain development, which may then impact susceptibility to brain aging or neurodegenerative processes in later life.81 Since brain iron accumulation is linked to aging and neurodegenerative processes, it is important to understand the effects of high iron intake at various life stages on the human brain. Preclinical studies evaluated the effects of neonatal iron intake on outcomes related to behavior and aging processes (Table 2) and on neurodegenerative processes in wild-type and genetically modified animals (Table 3). None of the studies fulfilled all the methodological criteria for quality. Although the strength of many studies was weakened by underreporting of methodological details, all but 1 preclinical study45 (Table 2) provided evidence that elevated iron intake in early life adversely affects cognition in adult rodents. Although outcomes in early adult life were studied most frequently, iron supplementation did increase brain regional iron levels, a marker of brain aging.15,16 Studies focused on neurodegenerative disease outcomes (Table 3) also provide evidence that neonatal iron supplementation promotes age-dependent progressive neurodegeneration in the substantia nigra, the main area of brain degeneration in Parkinson disease.53,57,63–65 Preclinical studies investigating interactions between neonatal iron nutrition and gene mutations causing neurodegeneration showed evidence of synergism between iron intake and genetic disease factors, although the number of studies was small.55,64,66 These findings suggest that individuals with gene mutations causing protein-misfolding neurodegenerative diseases may have increased susceptibility to the adverse effects of high iron intake in early life.

Exactly how the effects of neonatal iron intake in mice translate to humans is unclear. The form and the dose of iron supplementation are key factors affecting the interpretation of preclinical studies. Soluble ferrous succinate and insoluble iron carbonyl were used in the included preclinical studies; both forms are used for human supplementation. There was considerable variation in the daily dose of iron used in the neonatal iron supplementation studies. The highest dose of 120 mg/kg was used only with iron carbonyl, which has less bioavailability than ferrous salts.82 This highest level of supplementation in mice is estimated to result in an approximate 40-fold increase over the iron present in natural milk. Human infants fed iron-fortified formula have an iron intake level of up to 14 mg/d, which is also about 40-fold the intake level of breastfed infants.41,63,83–85 Therefore, when translating iron dose on a milligram-per-kilogram (mg/kg) basis from rodents to humans, the highest levels of supplementation used in the preclinical studies appear relevant to human nutrition.

All of the included human studies assessed the effect of adult-life iron intake or iron status on brain outcomes. These studies varied considerably in design, size, and outcomes measures. Study qualities were generally good (Tables 6 and 7). However, not surprisingly, results varied widely (Tables 4 and 5). Several of the human studies used Parkinson disease as their outcome, which is not surprising, given the evidence of an association between substantia nigra iron accumulation and Parkinson disease.86 The most complete iron nutrition study, based on the large number of subjects, the prospective study design, and the repeated food questionnaire analysis performed every 4 years, was that of Logroscino et al.69 (Table 4). These authors concluded that increased nonheme iron intake is a risk for Parkinson disease, especially when concurrent ascorbate deficiency is present. The literature searches conducted for the present review, however, did not identify any preclinical studies evaluating the effect of high iron intake in adult life on Parkinson disease outcomes in animal models. Preclinical studies that use varied outcomes would inform the need for additional human adult iron-nutrition studies assessing the risk for Parkinson disease development. Most studies evaluating the effects of peripheral iron status found evidence to support an association with poorer outcomes (Table 5). A weakness of the studies investigating blood iron status is that comprehensive measures of peripheral iron status were frequently not used. Furthermore, although some studies accounted for confounding factors, many did not account for the presence of inflammatory disease, which influences iron status.87,88

CONCLUSION

When the results of animal studies are combined, there is moderately strong evidence that nutritionally relevant levels of high iron intake during early postnatal life have adverse effects on the adult brain. Future preclinical studies could focus on improving the understanding of how high neonatal iron intake impacts the brain in adult life. Thus far, human studies of the effects of high iron intake on cognition and risk of disease do not strengthen these preclinical findings because they have investigated the effects of iron intake only in adult life. There are significant challenges, such as cost and time, when conducting prospective studies to examine the effects of early-life high iron intake on adult cognition and brain aging processes. Retrospective studies are also challenging because of the potential for recall bias. Nevertheless, the need for human studies in this area is supported by the preclinical findings reported in the literature. Human studies should assess factors besides nutrition that influence iron status, such as physiologic blood loss, gene polymorphisms, and the presence of inflammatory disease processes to better determine the role of iron nutrition on the outcomes investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Paul Troxell at the Society for Neuroscience for access to the abstract database and Jenny Garcia, University of Wyoming Coe Library, for guidance with the database searches.

Author contributions. K.L.B. and E.M. completed an initial literature search and analysis which defined the focus of the review. J.H.F. and S.A. designed the final searches, screened the papers for inclusion, extracted and summarized data, and completed methodological assessments. All authors contributed to writing and reviewing the manuscript and read and approved the submitted version.

Funding/support. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH RO1 NS079450).

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Supporting Information

The following Supporting Information is available through the online version of this article at the publisher’s website.

Appendix S1 Online search strategies for preclinical and clinical studies

Table S1 Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews or meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement

References

- 1. Wu LL, Zhang L, Shao J et al. Effect of perinatal iron deficiency on myelination and associated behaviors in rat pups. Behav Brain Res. 2008;188:263–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brunette KE, Tran PV, Wobken JD et al. Gestational and neonatal iron deficiency alters apical dendrite structure of CA1 pyramidal neurons in adult rat hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 2010;32:238–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Daubner SC, Le T, Wang S. Tyrosine hydroxylase and regulation of dopamine synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;508:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holmes-Hampton GP, Chakrabarti M, Cockrell AL et al. Changing iron content of the mouse brain during development. Metallomics. 2012;4:761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen JH, Shahnavas S, Singh N et al. Stable iron isotope tracing reveals significant brain iron uptake in adult rats. Metallomics. 2013;5:167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baltussen R, Knai C, Sharan M. Iron fortification and iron supplementation are cost-effective interventions to reduce iron deficiency in four subregions of the world. J Nutr. 2004;134:2678–2684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray-Kolb LE, Beard JL. Iron treatment normalizes cognitive functioning in young women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Scott SP, Murray-Kolb LE. Iron status is associated with performance on executive functioning tasks in nonanemic young women. J Nutr. 2016;146:30–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lozoff B, Beard J, Connor J et al. Long-lasting neural and behavioral effects of iron deficiency in infancy. Nutr Rev. 2006;64(5 pt 2):S34–S43; discussion S72–S91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003–2006. J Nutr. 2011;141:261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardiman O, Doherty CP, eds. Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Clinical Guide. London, UK: Springer; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thal DR, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Neurodegeneration in normal brain aging and disease. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004:pe26 doi:10.1126/sageke. 2004.23.pe26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO et al. Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain. Science. 1997;277:1990–1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guerrero EN, Wang H, Mitra J et al. TDP-43/FUS in motor neuron disease: complexity and challenges. Prog Neurobiol. 2016;145–146:78–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hallgren B, Sourander P. The effect of age on the non-haemin iron in the human brain. J Neurochem. 1958;3:41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ghadery C, Pirpamer L, Hofer E et al. R2* mapping for brain iron: associations with cognition in normal aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raven EP, Lu PH, Tishler TA et al. Increased iron levels and decreased tissue integrity in hippocampus of Alzheimer's disease detected in vivo with magnetic resonance imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37:127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. He N, Ling H, Ding B et al. Region-specific disturbed iron distribution in early idiopathic Parkinson's disease measured by quantitative susceptibility mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4407–4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rosas HD, Chen YI, Doros G et al. Alterations in brain transition metals in Huntington disease: an evolving and intricate story. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:887–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ignjatovic A, Stevic Z, Lavrnic S et al. Brain iron MRI: a biomarker for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;38:1472–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Elder GA, Gama Sosa MA, De Gasperi R. Transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010;77:69–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duty S, Jenner P. Animal models of Parkinson's disease: a source of novel treatments and clues to the cause of the disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:1357–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Philips T, Rothstein JD. Rodent models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2015;69:5.67.1–5.67.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferrante RJ. Mouse models of Huntington's disease and methodological considerations for therapeutic trials. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:506–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li K, Reichmann H. Role of iron in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2016;123:389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nunez MT, Urrutia P, Mena N et al. Iron toxicity in neurodegeneration. Biometals. 2012;25:761–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fleming DJ, Jacques PF, Tucker KL et al. Iron status of the free-living, elderly Framingham Heart Study cohort: an iron-replete population with a high prevalence of elevated iron stores. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Institute for Laboratory Animal Research, National Research Council. Guidance for the Description of Animal Research in Animal Research in Scientific Publications. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Krauth D, Woodruff TJ, Bero L. Instruments for assessing risk of bias and other methodological criteria of published animal studies: a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121:985–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lavich IC, de Freitas BS, Kist LW et al. Sulforaphane rescues memory dysfunction and synaptic and mitochondrial alterations induced by brain iron accumulation. Neuroscience. 2015;301:542–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Budni P, de Lima MN, Polydoro M et al. Antioxidant effects of selegiline in oxidative stress induced by iron neonatal treatment in rats. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:965–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. de Lima MN, Laranja DC, Caldana F et al. Selegiline protects against recognition memory impairment induced by neonatal iron treatment. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. de Lima MN, Presti-Torres J, Caldana F et al. Desferoxamine reverses neonatal iron-induced recognition memory impairment in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;570:111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. de Lima MN, Presti-Torres J, Garcia VA et al. Amelioration of recognition memory impairment associated with iron loading or aging by the type 4-specific phosphodiesterase inhibitor rolipram in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:788–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dornelles AS, Garcia VA, de Lima MN et al. mRNA expression of proteins involved in iron homeostasis in brain regions is altered by age and by iron overloading in the neonatal period. Neurochem Res. 2010;35:564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fernandez LL, de Lima MN, Scalco F et al. Early post-natal iron administration induces astroglial response in the brain of adult and aged rats. Neurotox Res. 2011;20:193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Figueiredo LS, de Freitas BS, Garcia VA et al. Iron loading selectively increases hippocampal levels of ubiquitinated proteins and impairs hippocampus-dependent memory. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:6228–6239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fredriksson A, Schroder N, Eriksson P et al. Neonatal iron exposure induces neurobehavioural dysfunctions in adult mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1999;159:25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fredriksson A, Schroder N, Eriksson P et al. Maze learning and motor activity deficits in adult mice induced by iron exposure during a critical postnatal period. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Isaac G, Fredriksson A, Danielsson R et al. Brain lipid composition in postnatal iron-induced motor behavior alterations following chronic neuroleptic administration in mice. FEBS J. 2006;273:2232–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Perez VP, de Lima MN, da Silva RS et al. Iron leads to memory impairment that is associated with a decrease in acetylcholinesterase pathways. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2010;7:15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rech RL, de Lima MN, Dornelles A et al. Reversal of age-associated memory impairment by rosuvastatin in rats. Exp Gerontol. 2010;45:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schroder N, Fredriksson A, Vianna MR et al. Memory deficits in adult rats following postnatal iron administration. Behav Brain Res. 2001;124:77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. da Silva VK, de Freitas BS, da Silva Dornelles A et al. Cannabidiol normalizes caspase 3, synaptophysin, and mitochondrial fission protein DNM1L expression levels in rats with brain iron overload: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:222–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Silva PF, Garcia VA, Dornelles AS et al. Memory impairment induced by brain iron overload is accompanied by reduced H3K9 acetylation and ameliorated by sodium butyrate. Neuroscience. 2012;200:42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. de Lima MN, Polydoro M, Laranja DC et al. Recognition memory impairment and brain oxidative stress induced by postnatal iron administration. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:2521–2528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fagherazzi EV, Garcia VA, Maurmann N et al. Memory-rescuing effects of cannabidiol in an animal model of cognitive impairment relevant to neurodegenerative disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berlin). 2012;219:1133–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miwa CP, de Lima MN, Scalco F et al. Neonatal iron treatment increases apoptotic markers in hippocampal and cortical areas of adult rats. Neurotox Res. 2011;19:527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Fredriksson A, Schroder N, Archer T. Neurobehavioural deficits following postnatal iron overload: I spontaneous motor activity. Neurotox Res. 2003;5:53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Wang X, Wang M, Yang L et al. Inhibition of Sirtuin 2 exerts neuroprotection in aging rats with increased neonatal iron intake. Neural Regen Res. 2014;9:1917–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Archer T, Fredriksson A. Functional consequences of iron overload in catecholaminergic interactions: the Youdim factor. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:1625–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Berggren KL, Chen J, Fox J et al. Neonatal iron supplementation potentiates oxidative stress, energetic dysfunction and neurodegeneration in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington's disease. Redox Biol. 2015;4:363–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Billings JL, Hare DJ, Nurjono M et al. Effects of neonatal iron feeding and chronic clioquinol administration on the parkinsonian human a53t transgenic mouse. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7:360–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chen H, Wang X, Wang M et al. Behavioral and neurochemical deficits in aging rats with increased neonatal iron intake: Silibinin's neuroprotection by maintaining redox balance. Front Aging Neurosci. 2015;7:206 doi:10.3389/fnagi.2015.00206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dal-Pizzol F, Klamt F, Frota ML Jr et al. Neonatal iron exposure induces oxidative stress in adult Wistar rat. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2001;130:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fernandez LL, Carmona M, Portero-Otin M et al. Effects of increased iron intake during the neonatal period on the brain of adult AβPP/PS1 transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1069–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fredriksson A, Archer T. Effect of postnatal iron administration on MPTP-induced behavioral deficits and neurotoxicity: behavioral enhancement by L-Dopa-MK-801 co-administration. Behav Brain Res. 2003;139:31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fredriksson A, Archer T. Subchronic administration of haloperidol influences the functional deficits of postnatal iron administration in mice. Neurotox Res. 2006;9:305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fredriksson A, Schroder N, Eriksson P et al. Neonatal iron potentiates adult MPTP-induced neurodegenerative and functional deficits. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2001;7:97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kaur D, Peng J, Chinta SJ et al. Increased murine neonatal iron intake results in Parkinson-like neurodegeneration with age. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28:907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peng J, Oo ML, Andersen JK. Synergistic effects of environmental risk factors and gene mutations in Parkinson's disease accelerate age-related neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Peng J, Peng L, Stevenson FF et al. Iron and paraquat as synergistic environmental risk factors in sporadic Parkinson's disease accelerate age-related neurodegeneration. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6914–6922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Berggren KL, Lu Z, Fox JA et al. Neonatal iron supplementation induces striatal atrophy in female YAC128 Huntington's disease nice. J Huntingtons Dis. 2016;5:53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hagemeier J, Tong O, Dwyer MG et al. Effects of diet on brain iron levels among healthy individuals: an MRI pilot study. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1678–1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hernandez Mdel C, Allan J, Glatz A et al. Exploratory analysis of dietary intake and brain iron accumulation detected using magnetic resonance imaging in older individuals: the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. J Nutr, Health Aging. 2015;19:64–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Logroscino G, Gao X, Chen H et al. Dietary iron intake and risk of Parkinson's disease. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1381–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Powers KM, Smith-Weller T, Franklin GM et al. Dietary fats, cholesterol and iron as risk factors for Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2009;15:47–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Powers KM, Smith-Weller T, Franklin GM et al. Parkinson's disease risks associated with dietary iron, manganese, and other nutrient intakes. Neurology. 2003;60:1761–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Anderson C, Checkoway H, Franklin GM et al. Dietary factors in Parkinson's disease: the role of food groups and specific foods. Mov Disord. 1999;14:21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Blasco G, Puig J, Daunis IEJ et al. Brain iron overload, insulin resistance, and cognitive performance in obese subjects: a preliminary MRI case-control study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3076–3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Andreeva VA, Galan P, Arnaud J et al. Midlife iron status is inversely associated with subsequent cognitive performance, particularly in perimenopausal women. J Nutr. 2013;143:1974–1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Umur EE, Oktenli C, Celik S et al. Increased iron and oxidative stress are separately related to cognitive decline in elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011;11:504–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mueller C, Schrag M, Crofton A et al. Altered serum iron and copper homeostasis predicts cognitive decline in mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Milward EA, Bruce DG, Knuiman MW et al. A cross-sectional community study of serum iron measures and cognitive status in older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;20:617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schiepers OJ, van Boxtel MP, de Groot RH et al. Serum iron parameters, HFE C282Y genotype, and cognitive performance in older adults: results from the FACIT study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:1312–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Gao S, Jin Y, Unverzagt FW et al. Trace element levels and cognitive function in rural elderly Chinese. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:635–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lam PK, Kritz-Silverstein D, Barrett Connor E et al. Plasma trace elements and cognitive function in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:22–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Modgil S, Lahiri DK, Sharma VL et al. Role of early life exposure and environment on neurodegeneration: implications on brain disorders. Transl Neurodegener. 2014;3:9 doi:10.1186/2047-9158-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Devasthali SD, Gordeuk VR, Brittenham GM et al. Bioavailability of carbonyl iron: a randomized, double-blind study. Eur J Haematol. 1991;46:272–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Dewey KG, Finley DA, Lonnerdal B. Breast milk volume and composition during late lactation (7–20 months). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1984;3:713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Dewey KG, Lonnerdal B. Milk and nutrient intake of breast-fed infants from 1 to 6 months: relation to growth and fatness. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1983;2:497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lonnerdal B. Effects of milk and milk components on calcium, magnesium, and trace element absorption during infancy. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:643–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Ayton S, Lei P. Nigral iron elevation is an invariable feature of Parkinson's disease and is a sufficient cause of neurodegeneration. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:581256 doi:10.1155/2014/581256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Wang W, Knovich MA, Coffman LG et al. Serum ferritin: past, present and future. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:760–769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Nemeth E, Ganz T. Anemia of inflammation. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28:671–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.