Abstract

Evidence-informed guideline development methods underpinned by systematic reviews ensure that guidelines are transparently developed, free from overt bias, and based on the best available evidence. Only recently has the nutrition field begun using these methods to develop public health nutrition guidelines. Given the importance of following an evidence-informed approach and recent advances in related methods, this study sought to describe the methods used to synthesize evidence, rate evidence quality, grade recommendations, and manage conflicts of interest (COIs) in national food-based dietary guidelines (FBDGs). The Food and Agriculture Organization’s FBDGs database was searched to identify the latest versions of FBDGs published from 2010 onward. Relevant data from 32 FBDGs were extracted, and the findings are presented narratively. This study shows that despite advances in evidence-informed methods for developing dietary guidelines, there are variations and deficiencies in methods used to review evidence, rate evidence quality, and grade recommendations. Dietary guidelines should follow systematic and transparent methods and be informed by the best available evidence, while considering important contextual factors and managing conflicts of interest.

Keywords: evidence-based nutrition, evidence-informed guideline development, food-based dietary guidelines, public health nutrition, systematic review, GRADE

INTRODUCTION

Evidence-informed health guidelines are founded on rigorously conducted systematic reviews, which follow transparent processes to identify, evaluate, and synthesize relevant available research on specific questions.1 Increasingly, these guidelines rate the quality of the evidence and grade the strength of recommendations using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.2,3 GRADE provides a systematic and transparent framework for moving from evidence to recommendations.2 These approaches are part of the internationally recognized standards and methods for guideline development that aim to ensure guidelines are transparently developed, free from overt bias, meet a public health need, and are based on a comprehensive assessment of the best available evidence.4,5

Evidence-informed guideline development methods are used extensively for the development of clinical guidelines.4–7 In the nutrition field, use of these methods to develop public health nutrition guidelines, such as food-based dietary guidelines, has been more recent. In the early 1990s the view that “people eat foods and not nutrients” led nutrition scientists and policymakers to develop food-based guidelines in addition to nutrient-based recommendations. These guidelines are translations of quantitative nutrient references, standards, and goals into understandable messages about food choices and eating behaviors.8 They also provide an evidence base for public food, nutrition, health, and agricultural policies and for programs that aim to foster healthy eating habits and lifestyles.9 The key scientific considerations for food-based dietary guidelines were developed by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and World Health Organization (WHO) in 1995.8 These considerations include identifying evidence for the relationships between food, nutrients, and health8 and gathering evidence from empirical studies10 and statistical modeling11 on relationships between dietary patterns and health.

Although the fundamental scientific principles in the FAO/WHO approaches to developing food-based dietary guidelines remain important, much progress has been made since the early to mid-2000s in adopting more explicit and evidence-informed methods for the development of these guidelines.1,12–15 For example, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL) conducts systematic reviews that provide evidence to inform their guidelines.16 The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Nutrition Guidance Expert Advisory Group (NUGAG) also uses evidence-informed methods as the basis for their guidelines.4,17

However, despite advances in use of evidence-informed methods, inconsistencies among guideline developers still exist. The meaning of “evidence” for policymakers and scientists is also often discrepant.18 Furthermore, implementation of evidence-informed methods for dietary guideline development in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) may be lagging behind, likely due to resource limitations and lack of capacity. These organizational factors are well recognized barriers to using evidence in policymaking.18

Given the importance of evidence-informed methods for developing dietary guidelines and advances in methods for preparing systematic reviews, rating evidence, and grading recommendations, there is a need to assess the methods used to develop food-based dietary guidelines for generally healthy populations. Tools to assess methodological rigor and transparency of guideline development, such as the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE II) Instrument19 and the iCAHE Guideline Quality Checklist,20 are available. These tools consist of multiple domains covering numerous methodological components. This study seeks to describe certain methodological components in dietary guideline development—namely, the methods used to conduct the evidence review process, rating the quality of evidence, grading the strength of recommendations, and managing conflicts of interest in recent national food-based dietary guidelines for healthy populations. It does not seek to assess other types of dietary recommendations such as references for nutrient intakes (eg, dietary reference intakes [DRIs] or dietary reference values [DRVs]). These types of recommendations may require different assessment approaches because they are based on combinations of various data types, such as data on maintenance of body stores and/or function, along with a safety factor, experimental and/or observational human studies, and in vitro and animal studies, to generate knowledge about mechanisms and/or dosages and to derive upper tolerable intake levels where studies on humans are insufficient.

METHODS

Identification and selection of food-based dietary guidelines

The FAO’s food-based dietary guidelines database9 was hand-searched for relevant guidelines added before January 14, 2016. Since the 1992 International Conference on Nutrition, the FAO and WHO have invited governments and official research organizations to submit new and revised versions of their guidelines to the FAO database. Submitted guidelines are republished with the permission of the owners.9,21 This database was searched because it is the most comprehensive database the authors know of and food-based dietary guidelines are not typically indexed in traditional scientific databases.

Guidelines in the FAO food-based dietary guidelines database were included in this study if they 1) were published in 2010 or later; 2) fit the WHO definition of a guideline (ie, “any document that contains a recommendation for clinical health practice or public health policy”4); and 3) were a food-based dietary guideline, defined as translations of quantitative nutrient requirements into simple, understandable messages for generally healthy populations about diets for promoting overall health, and may include guidance on food groups, beverages, key nutrients, dietary patterns (quantities, proportions, frequencies), food portions, and physical activity.21 Guidelines published in any language were included; however, non-English language guidelines with documents that could not be copied into Google translate were excluded. Supplementary documents, referenced in included guidelines, that described guideline development methods were also included. The latest available version of a guideline was included.

Guidelines were excluded if they 1) focused solely on a special population or health condition, such as subpopulations with nutrient deficiencies or noncommunicable diseases; 2) were “stand-alone” nutrient reference guidelines that are not part of the national food-based dietary guidelines (eg, Swiss Salt Strategy); or 3) were published only as a food guide without a substantial body of text (eg, in a food-pyramid, plate, or similarly designed pictorial or graphic representations).

Data extraction and analysis

General information about the guidelines was extracted—for example, the date of publication and country or region for which the guideline was developed. Drawing from available tools to assess methodological rigor and transparency of guideline development,19,20 the following information was also extracted: (1) type of evidence reviewed for the guideline, (2) methods used to review the evidence for the guideline, (3) methods used to formulate and grade the strength of the recommendations, (4) methods for disclosing and managing conflicts of interest (COIs) during guideline development, and (5) disclosure of funding sources for guideline development.

The type of evidence reviewed was categorized as (i) other countries’ national dietary guidelines, (ii) country’s own current or previous dietary guidelines, (iii) existing systematic reviews, (iv) existing reports from authoritative organizations, (iii) other types of evidence reviews (eg, umbrella reviews, traditional reviews), (iv) systematic reviews specifically commissioned for the guideline, (v) individual experimental studies, (vi) individual observational studies, or (vii) dietary reference intake documents.

The methods used to review the evidence included methods to (i) define the question (eg, through focus groups), (ii) search for evidence (eg, databases searched), (iii) extract data (eg, double coding), (iv) assess the risk of bias of the included individual studies or reviews (eg, AMSTAR,22 RoBIS23), (v) synthesize the evidence (eg, meta-analysis), and (vi) rate the overall quality of the evidence, which takes into account the risk of bias assessment of included studies, as well as issues such as precision and directness (eg, GRADE, levels of evidence).24

Grading recommendations involves making judgments about the strength of a recommendation25 (eg, strong vs weak), taking into account the overall quality of evidence available, as well as factors such as benefits and harms and resource implications. Methods used were classified as (i) consensus methods (eg, Delphi approach, expert working groups), (ii) structured consensus methods (eg, GRADE), or (iii) quantitative methods (eg, Bayesian analyses).

Data were analyzed with Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics. Numbers and proportions of food-based dietary guidelines reporting specific methods are presented narratively and in tables.

RESULTS

Search results

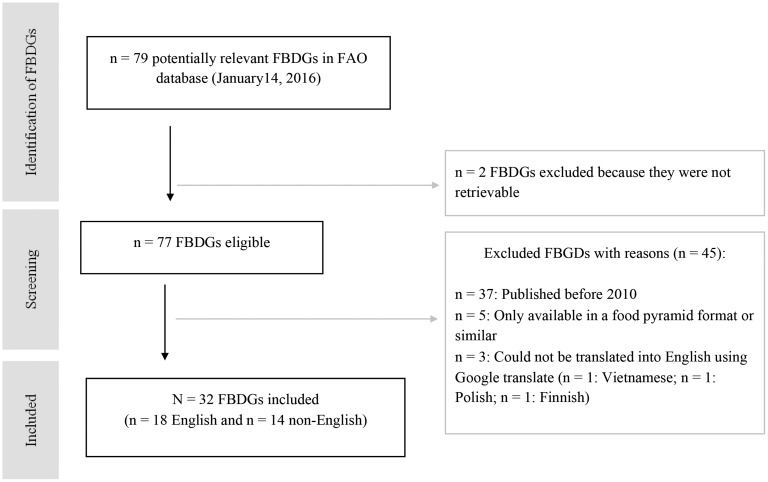

At the time of the hand-search, the FAO database9 contained food-based dietary guidelines from 79 countries across 6 regions. Two of these guidelines could not be retrieved (Mongolia and Nepal). Of the remaining 77 guidelines, some were excluded because they were published before 2010 (n = 37), were only available in a food guide format (n = 5), or were published in another language and could not be translated into English through Google translate (n = 3) (Table 1). Thus, 32 guidelines were included in the analysis, 18 in English and 14 in other languages (Figure 1). Additional documents related to guideline development methods were identified for the following countries’ guidelines: Australia,15 Canada,26 Chile,27 Costa Rica,28 Denmark,13 Germany,29 Guatemala,30 Ireland,31 Norway,32 Sweden,33 Switzerland,34 and the United States.14 The Belize guideline document referred to following methods in FAO’s report on developing food-based dietary guidelines for the English-speaking Caribbean.21

Table 1.

List of excluded food-based dietary guidelines and reasons for exclusion

| Country or region | Publication date | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | 2008 | Publication date <2010 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 2013 | Food pyramid Format |

| Austria | 2010 | Food pyramid format |

| Bahamas | 2002 | Publication date <2010 |

| Barbados | 2009 | Publication date <2010 |

| Belgium | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2004 | Publication date <2010 |

| China | 2007 | Publication date <2010 |

| Croatia | 2002 | Publication date <2010 |

| Cuba | 2009 | Publication date <2010 |

| Cyprus | 2007 | Publication date <2010 |

| Dominica | 2007 | Publication date <2010 |

| Dominican Republic | 2009 | Publication date <2010 |

| Estonia | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Fiji | 2009 | Publication date <2010 |

| Finland | 2014 | Cannot translate |

| Georgia | 2005 | Publication date <2010 |

| Greece | 1999 | Publication date <2010 |

| Grenada | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Guyana | 2004 | Publication date <2010 |

| Hungary | 2004 | Publication date <2010 |

| Iran | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Israel | 2008 | Publication date <2010 |

| Italy | 2003 | Publication date <2010 |

| Japan | 2005 | Publication date <2010 |

| Latvia | 2008 | Publication date <2010 |

| Malta | 1986 | Publication date <2010 |

| Mongolia | – | Could not be retrieved |

| Namibia | 2000 | Publication date <2010 |

| Nepal | – | Could not be retrieved |

| Nigeria | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Oman | 2009 | Publication date <2010 |

| Poland | 2010 | Could not be translated |

| Portugal | 2003 | Publication date <2010 |

| Republic of Korea | 2010 | Food pyramid format |

| Romania | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Saint Vincent and the Grenadines | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Santa Lucia | 2010 | Food pyramid format |

| Seychelles | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Slovenia | 2015 | Food pyramid format |

| Spain | 2008 | Publication date <2010 |

| Thailand | 1998 | Publication date <2010 |

| Turkey | 2006 | Publication date <2010 |

| Uruguay | 2005 | Publication date <2010 |

| Venezuela | 1991 | Publication date <2010 |

| Vietnam | 2011 | Could not be translated |

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the selection process of food-based dietary guidelines. Abbreviations: FAO, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; FBDGs, food-based dietary guidelines.

Description of included guidelines

Of the 32 included food-based dietary guidelines, 2 were from countries in Africa, 7 from countries in Asia and the Pacific, 10 from countries in Europe, 11 from countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, and 2 from countries in North America (Table 2).27,35–65 Included guidelines were published between 2010 and 2015. The most recent guidelines were from Benin, Jamaica, New Zealand, Paraguay, Sweden, and the United States. The guidelines from Malaysia and Saint Kitts and Nevis were the earliest in this dataset, published in 2010.

Table 2.

List of included food-based dietary guidelines

| Country | Title of guideline | Publication date |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | ||

| Benin35 | Benin’s Dietary Guidelines | 2015 |

| South Africa36 | Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africans | 2013 |

| Asia and the Pacific | ||

| Australia37 | Australian Dietary Guidelines | 2013 |

| Bangladesh38 | Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh | 2014 |

| India39 | Dietary Guidelines for Indians | 2011 |

| Malaysia40 | Malaysian Dietary Guidelines | 2010 |

| New Zealand41 | New Zealand Food and Nutrition Guidelines | 2015 |

| Philippines42 | 2012 Nutritional Guidelines for Filipinos | 2012 |

| Sri Lanka43 | Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Sri Lankans | 2011 |

| Europe | ||

| Denmark44 | The Official Dietary Guidelines | 2013 |

| Germany45 | Ten Guidelines for Wholesome Eating and Drinking from the German Nutrition Society | 2013 |

| Iceland46 | Dietary and Nutrition Guidelines | 2014 |

| Ireland47 | Your Guide to Healthy Eating Using the Food Pyramid | 2011 |

| Macedonia48 | Dietary Guidelines for the Population in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia | 2014 |

| Netherlands49 | Guidelines for Healthy Dietary Choices | 2011 |

| Norway50 | Norwegian Guidelines on Diet, Nutrition, and Physical Activity 2014 | 2014 |

| Sweden51 | Find Your Way to Eat Greener, Not Too Much and Be Active | 2015 |

| Switzerland52 | 6th Nutrition Report (full report not available in English) | 2012 |

| United Kingdom53 | The Balance of Good Health/The Eat Well Plate | 2013 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | ||

| Belize54 | Food-based Dietary Guidelines for Belize | 2012 |

| Brazil65 | Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population 2014 | 2014 |

| Chile55 | Dietary guidelines for the Chilean population, Ministry of Health 2013 | 2013 |

| Costa Rica56 | Dietary Guidelines for Costa Rica | 2011 |

| El Salvador57 | Dietary Guidelines for Salvadorian families | 2012 |

| Guatemala58 | Dietary Guidelines for Guatemala: Recommendations for Healthy Eating | 2012 |

| Honduras59 | Dietary Guidelines for Honduras. Tips for Healthy Eating | 2013 |

| Jamaica60 | Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Jamaica: Healthy Eating—Active Living | 2015 |

| Panama61 | Dietary Guidelines for Panama | 2013 |

| Paraguay62 | Dietary Guidelines for Paraguay | 2015 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis63 | Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for St Kitts and Nevis | 2010 |

| North America | ||

| Canada26 | Eating Well with Canada’s Food Guide—A Resource for Educators and Communicators | 2007 |

| United States64 | Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2015–2020, 8th edition | 2015 |

Type of evidence used to inform the guidelines

Most of the included guidelines were updates of the country’s own previously published guidelines (n = 23/32). Seventy-five percent were based primarily on existing scientific reports from authoritative bodies (n = 24/32), and more than half (n = 18/32) were based on other countries’ national dietary guidelines (Table 3). Major reports that have contributed to numerous countries’ guidelines (eg, Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, Malaysia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, and others) include the 2004 WHO/FAO Joint Report on Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases and the World Cancer Research Fund Report on Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer.66,67 Ten of the 32 guidelines were based on existing systematic reviews (Australia, Canada, Chile, India, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, and United States). Only the guidelines for Australia, Germany, and the United States commissioned systematic reviews to inform their guidelines. Some guidelines were based on multiple types of evidence. For example, the guidelines for Canada, Chile, New Zealand, and Sweden were based on other country’s guidelines, the previous version of their own guidelines, reports from authoritative institutions, and existing systematic reviews. For the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or reports were used for 45% of the research questions, and reviews were commissioned to address the remaining questions.64

Table 3.

Type of evidence used to inform the food-based dietary guidelines (n = 32)

| Evidence used to inform FBDGsa | No. (%) | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Previous version of own guidelines | 23 (71.9) | Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Ireland, Macedonia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Panama, Paraguay, Sri Lanka, Philippines, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States |

| Other countries’ national guidelines | 18 (56.3) | Bangladesh, Belize, Canada, Chile, Costa Rica, Denmark, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Iceland, Ireland, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland |

| Existing reports by authoritative bodies | 24 (75) | Australia, Belize, Benin, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Ireland, Jamaica, Macedonia, Malaysia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Saint Kitts and Nevis, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, |

| Previously published systematic reviews | 10 (31.3) | Australia, Canada, Chile, India, New Zealand, Norway, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States |

| Systematic review conducted specifically for guideline | 4 (12.5) | Australia, Germany, USA, United Kingdom |

| Other types of evidence reviews (eg, umbrella reviews, traditional reviews, overviews) | 8 (25) | South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, United Kingdom, Brazil, Chile, Guatemala |

Abbreviation: FBDG, food-based dietary guideline.

Categories not mutually exclusive.

Methods used to conduct the evidence review process for the guidelines

Two of the 32 included guidelines specified the methods used to define the questions for the evidence review (Australia and United States)—namely, working groups developed and refined the research questions (Table 4).

Table 4.

Methods reported to conduct the evidence reviews in the included food based dietary guidelines (n = 32)

| FBDGs reporting methods to: | Proportion (%) | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| Define the question | 3/32 (9.4) | |

| Guidelines working groups develop and refine research questions for the guideline | 2/3 | Australia, USA |

| Identify and search for evidence | 4/32 (12.5) | |

| Listed databases searched | 2/4 | Australia, Norway |

| Stated searching electronic databases without specifying which | 2/4 | Germany, USA |

| Scanned reference lists of included studies and reviews | 1/4 | USA |

| Listed the years searched | 3/4 | Australia (2002–2009), Norway (January 2000 to December 2010), USA (varies for each question) |

| Searched for unpublished data | 1/4 | Norway |

| Unpublished data were not considered | 2/4 | Germany, USA |

| Extract data | 2/32 (6.3) | |

| NEL methodology; dual coding | 1/2 | USA |

| WCRF report methodology | 1/2 | Norway |

| Assess risk of bias of included studies | 3/32 (9.4) | |

| NHMRC levels of evidence | 1/3 | Australia |

| NEL Bias Assessment Tool for primary studies; AMSTAR for systematic reviews identified in the literature search | 1/3 | USA |

| WHO Levels of Evidence (1–5) | 1/3 | Germany |

| Rate overall quality of the evidence | 5/32 (15.6) | |

| NHMRC grading system | 1/5 | Australia |

| Technical advisory group discussion | 1/5 | New Zealand |

| WHO levels of evidence | 1/5 | Germany |

| WCRF classification | 1/5 | Norway |

| NEL grading rubric | 1/5 | USA |

| Synthesize evidence | 2/32 (6.3) | |

| Qualitative synthesis | 1/2 | USA |

| WCRF methods/matrices | 1/2 | Norway |

Abbreviations: AMSTAR: Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews; FBDG, food-based dietary guideline; NEL, Nutrition Evidence Library; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; WCRF, World Cancer Research Fund; WHO, World Health Organization.

Only 13% (n = 4/32) of guidelines described the methods used to identify the evidence, which included database searching (n = 4/4; Australia, Norway, Germany, United States) and scanning reference lists of included studies (n = 1/4; United States). Three guidelines reported the years searched: the latest date searched was 2009 for the Australian guidelines and 2010 for the Norwegian guidelines, whereas the latest date searched for the US guidelines varied for each research question. Unpublished data were sought for the Norwegian guidelines, and those from the United States and Germany did not consider unpublished data.

Two of 32 included dietary guidelines reported the methods used to extract data. The United States used the NEL methodology and dual coding,16 and Norway used the World Cancer Research Fund methodology.32

Three of the 32 guidelines reported methods used to assess the risk of bias of the included individual studies or reviews (Australia, Germany, and United States) (Table 4). The US guidelines used AMSTAR to assess the risk of bias of included systematic reviews and the NEL Bias Assessment Tool for individual studies.16,22 German guidelines used the WHO levels of evidence, and the Australian guidelines used the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) levels of evidence hierarchy (eg, randomized controlled trials rated higher than cohort studies) to assess risk of bias of individual studies.

Five guidelines described methods to rate the overall quality of the evidence. These included the NHMRC body of evidence grading system (Australia), WHO levels of evidence (Germany), World Cancer Research Fund classification (Norway), NEL grading rubric (United States), and a discussion of the technical advisory group (New Zealand). Some of these methods are reported in the guideline documents as methods to assess the risk of bias of included studies, as well as to rate the overall quality of the evidence (eg, NHMRC). This is because they follow a 2-step system where first, the evidence level is assigned to each included study based on the study design, and second, the overall quality of the studies that provide the evidence base for a recommendation is rated, based on the assigned levels and sometimes on other considerations such as precision and generalizability. Many of these methods were described as methods used to grade the strength of recommendations in the included guidelines and supplementary guideline documents.

Only the US and Norwegian guidelines specified methods used to synthesize the evidence. For the US guidelines, a qualitative synthesis of the evidence was carried out to identify “key trends” for each systematic review question.64 In the Norwegian guideline, matrices of evidence based on World Cancer Research Fund methodology were used to synthesize the evidence.

Most guidelines (n = 27) did not describe any of the steps required for reviewing the evidence—namely, defining the research question, identifying and searching for evidence, extracting data, evaluating the quality of the evidence, and synthesizing the evidence. The US guideline was the only one that specified all of these steps. Guidelines that commissioned systematic reviews provided more details about the methods used to review the evidence. The South African guidelines were based on a series of technical papers, and only 2 of these followed systematic processes to review the evidence and were thus not classified as having reported all of the review steps.

Methods used to formulate and grade the strength of recommendations in the guideline

In almost all of the guidelines (n = 28), the recommendations were formulated through a consensus process by the working groups or committees established to develop the guidelines. Seven guidelines also reported conducting stakeholder consultations or workshops with experts and health professionals to discuss the wording of the recommendations (Bangladesh, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Honduras, Malaysia, and Sweden). Four guidelines did not report how recommendations were formulated (El Salvador, Panama, Paraguay, and Switzerland). No guidelines used quantitative approaches.

None of the guidelines graded the strength of recommendations, either through consensus or through a structured consensus process such as GRADE.25 Some guidelines reported grading the recommendations, but they were generally referring to methods used to rate the overall quality of the evidence base (described in the section above). For example, the German Dietary guidelines report using the WHO levels of evidence for study designs, together with considerations such as effect size, context, and generalizability, to grade the strength of their recommendations into convincing, probable, or possible.29 The Norwegian dietary guidelines32 reported using World Cancer Research Fund methods to grade strength of recommendations; however, these methods rate the evidence into 4 categories—namely, convincing causality, probable causality, unlikely causality, or limited information to determine causality, based only on the type and quality of the evidence available.

Methods for disclosing and managing conflicts of interest and disclosed funding sources

Three of the 32 guidelines reported having a policy for dealing with COIs (Australia, United Kingdom, and United States). These same guidelines and the Canadian guidelines reported on the COIs of working members in the guideline document or in supporting methodological papers (Table 5).

Table 5.

Reporting of conflict of interest statements and funding sources in included food-based dietary guidelines (n = 32)

| FBDG methods | No. (%) | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| COI policy stated | 3 (9.4) | Australia, United Kingdom, USA |

| COI reported in FBDG or supporting documents | 4 (12.5) | Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, USA |

| FBDG funding sources declared | 10 (31.3) | Australia, Bangladesh, Chile, Germany, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, South Africa, Switzerland |

Abbreviations: COI, conflict of interest; FBDG, food-based dietary guideline.

Ten dietary guidelines reported the funding sources for preparing the guideline (Table 5). All of these countries received funding from a governmental body (eg, Ministry of Health), from national professional associations, or from international governmental agencies (eg, FAO or the Pan American Health Organization).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main findings

Food-based dietary guidelines establish a basis for public food and nutrition, health, and agricultural policies and for nutrition education programs to promote healthy eating and lifestyles in the general population.68 They should be informed by all available current best evidence that has been transparently and objectively identified, appraised, and synthesized, as well as by other important factors to consider when moving from evidence to decisions, such as resource implications, values and preferences, feasibility, equity, and health benefits, harms and burden.69 This study showed inconsistencies and limitations in certain methods used to develop national food-based dietary guidelines when considering current methods for evidence-informed guideline development.1,4 The majority of included guidelines were updates of previous guidelines, used existing scientific reports from authoritative bodies, and were based on other countries’ national dietary guidelines. Few guidelines were based on systematic reviews, and only 3 countries commissioned systematic reviews specifically for the guidelines. Very few dietary guidelines reported methods for systematically reviewing available research evidence.1 Most countries used a consensus-based approach to formulate the recommendations, and none graded the strength of recommendations. Ten countries disclosed their funding sources for developing the guidelines, all of which were governmental bodies, professional associations, or international agencies. Very few guidelines had explicit COI policies and statements from guideline panel members.

Potential reasons for findings and implications for practice

Most of the dietary guidelines reviewed do not fully align with current methods for evidence-informed guideline development.24,25,70–83 The issue of disparate definitions of what is regarded as evidence was also seen in included guidelines, with documents citing indirect or secondary documents as evidence (eg, previous versions of guidelines) without an assessment of the certainty of this evidence in most guidelines. Organizations such as WHO and the Australian Health and Medical Research Council recognize that methods for development of clinical practice guidelines may not be directly applicable to the development of public health guidelines, including food-based dietary guidelines.84 These organizations are working with researchers to modify their handbooks for guideline development to include evidence-based guidance on how to evaluate observational studies and other types of evidence that might be included. The WHO is currently developing a manual for the preparation of food-based dietary guidelines that will be more aligned with the WHO handbook for guideline development4 (personal communication on May 9, 2016 between C.E.N. and H.H.Vorster, Centre of Excellence for Nutrition, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa).

Structured consensus methods, such as GRADE, that rate the evidence base and grade the strength of recommendations reduce bias in developing guidelines.85 They provide a formal and transparent approach to rate the overall quality of the supporting evidence and grade the strength of recommendations by considering the certainty of the evidence, as well as other important factors.73,78 However, these methods may not be directly applicable to the types of studies included in food-based dietary guidelines, and GRADE has working groups focused on GRADE for public health, modeling studies, or environmental exposure studies.86 Other examples of structured consensus approaches include the NEL grading rubric and the NHMRC levels and grades. The lack of resources and capacity in low-resource settings may present challenges to fully implementing these structured consensus approaches, but capacity development and guideline adaptation methods could help to overcome some of these challenges.87,88

Some unique issues must be considered when preparing nutrition systematic reviews that form the evidence base for guidelines.12,89 These include the need to consider baseline exposure to certain nutrients, uncertainties assessing dose–response relationships, and the multiple and interrelated biological functions of a nutrient.12 Although these issues may impose challenges on the process, recently published nutrition systematic reviews have demonstrated the potential of the methodology to evolve to meet the requirements of these more complex reviews.90–92

Preparing systematic reviews can be costly and time-consuming, and even if up-to-date and relevant systematic reviews are available, their risk of bias should still be assessed before they are used for guideline development. Advances in the automation of some systematic review steps could make the process of updating or producing new reviews more efficient.93 It is understandable that evidence-informed methods were not followed for dietary guideline development in LMICs because these countries often face challenges related to multiple competing burdens, limited time, capacity, funding, and human resources.

To address challenges in conducting nutrition systematic reviews and implementing evidence-informed guideline development methods, it may be necessary for guideline groups to prioritize certain required steps over others and use a simplified, practical, yet rigorous process.5 In these cases, guideline developers should be explicit about their chosen method and which steps they are going to prioritize and why. For example, rather than conducting a full search for evidence, a guideline development group may conduct a modified search to update an existing review used in a guideline.

Adapting high-quality guidelines developed in one country to another setting is another efficient approach to guideline development. High-quality, evidence-informed guidelines can be developed using fewer resources if they are based on recent guidelines that have closely followed evidence-informed methods, such as the most recent dietary guidelines from Australia and the United States. Often, LMICs use or adapt existing guidelines from high-income countries.14,37,64 However, before adaptation, the quality of guidelines should first be assessed using tools such as AGREE II.19 In addition, because of differing geographical locations and ethnic backgrounds of the population, countries must consider cultural, social, and intake diversities in their guideline development and adaptation because these substantially influence population diets.94,95 For example, the Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population address the cultural and social dimensions of food choices, food preparation, and modes of eating, tailored to the Brazilian culture.65

Disclosing COIs and funding sources for guideline development is essential because these may result in potential biases that influence the recommendations in the guidelines.96,97 Financial COIs could include stocks or shares, paid employment, or research grants, and nonfinancial conflicts could include leadership or close involvement with an advocacy group that stands to gain from the opinion of guideline advisory members.6 Even if COIs in guideline development are stated, methods of managing these conflicts can often reduce, but not eliminate, the risk of bias.70 Conflicts of interest should be dealt with in a fair, judicious, and transparent manner.98 Ideally, the chair and majority of members of the guideline development group should have no conflicts of interest. Some guideline developers limit or prohibit potential COIs altogether.4 Guideline groups should decide beforehand the extent to which members with COIs would be able to participate in guideline development.4 For similar reasons, funding sources for guideline development and for any systematic reviews used to inform guidelines should be clearly stated.

Strengths and limitations

The source of food-based dietary guidelines used was reliable, and additional supporting documents related to guideline development were also searched for, which reduces the chance that relevant information was missed. Data were extracted, drawing on domains in well-established tools that assess methodological rigor and transparency of guideline development methods.19,20 However, because most of these tools were developed for clinical practice guidelines, there may be other important domains for the assessment of public health guideline development methods that were not captured. This study relied on information reported in the guidelines and accompanying documents, and some methods for guideline development may not have been adequately documented. Google translate was used for guidelines not published in English, which may have led to missing or misinterpreting some of the information. Lastly, the authors did not access all types of evidence cited in guidelines, such as existing scientific reports from authoritative bodies or other countries’ national dietary guidelines, to assess the original research evidence on which they are based. Thus, the documents included in this study may not provide all of the detailed information on types of evidence used in the guidelines.

CONCLUSION

Because dietary guidelines are intended to assist stakeholders in making informed nutrition and health decisions, governments and official research organizations should implement efficient, explicit, and reproducible guideline methods that balance rigor and pragmatism. Despite advances in evidence-informed methods for developing dietary guidelines, there are still inconsistencies in methods for evidence review, rating evidence quality, and grading recommendations. For dietary guidelines aiming to foster healthy eating and that underpin public nutrition and agricultural policies, development methods should be systematic, transparent, efficient, and informed by the best available evidence and pertinent contextual factors, while managing conflicts of interest and working toward stakeholder participation in guideline development. In resource-constrained settings, such as LMICs, it may be more challenging to implement these methods. However, adaptation of other high-quality guidelines for these settings could be a feasible option.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Taryn Young and Dr Tamara Kredo for their input into the protocol for this research.

Author contributions. P.B. and S.D. are co–first authors. P.B. searched for the guidelines and documents, extracted and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. S.D. contributed to the development of the protocol, extracted and analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. C.E.N. contributed to the development of the protocol, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. L.B. contributed to the development of the protocol, data extraction and analysis, and drafting of the manuscript.

Financial support. The authors did not receive a specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors for this research. C.E.N. and S.D. are partly supported by the Effective Health Care Research Consortium. This Consortium is funded by UK aid from the UK Government for the benefit of developing countries (Grant: 5242). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect UK government policy.

Declaration of interest. The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

References

- 1. Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0. London: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available at: www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed January 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guyatt G, Oxman A, Schunemann HJ et al. , GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:380–382.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guyatt G, Oxman A, Akl EA et al. , GRADE guidelines 1: Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. WHO Handbook for Guideline Development. Geneva, Swizerland: WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schunemann HJ, Wiercioch W, Etxeandia I et al. , Guidelines 2.0: systematic development of a comprehensive checklist for a successful guideline enterprise. CMAJ. 2014;186:E123–E142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qaseem A, Snow V, Owens DK et al. , The development of clinical practice guidelines and guidance statements of the American College of Physicians: summary of methods. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:194–199.http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Raval AD, Thakker D, Negi H et al. , Association between statins and clinical outcomes among men with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:151–162.http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2015.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Food and Agriculture Organization, World Health Organization. Preparation and Use of Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Geneva, Switzerland: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. http://www.fao.org/nutrition/education/food-dietary-guidelines/home/en/. Accessed August 4, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10. United States Department of Agriculture. A Series of Systematic Reviews on the Relationship Between Dietary Patterns and Health Outcomes. Alexandria, VA: United States Department of Agriculture, Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, Evidence Analysis Library Division; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Government, Department of Health and Aging, National Health and Medical Research Council. A Modelling System to Inform the Revision of the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lichtenstein AH, Yetley EA, Lau J.. Application of systematic review methodology to the field of nutrition. J Nutr. 2008;138:2297–2306.http://dx.doi.org/10.3945/jn.108.097154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nordic Co-operation. Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2012. Integrating nutrition and physical activity. Copenhagen, Denmark: Nordic Council of Ministers; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 14. 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Scientific Report for the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee: Advisory Report to the Secretary of Human Health and Human Services and the Secretary of Agriculture. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Health and Medical Research Council. A Review of Evidence to Address Targeted Questions to Inform the Revision of the Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Obbagy JE, Blum-Kemelor DM, Essery EV et al. , Nutrition Evidence Library: methodology used to identify topics and develop systematic review questions for the birth-to-24-mo population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:692S–696S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee K, Fang J.. Historical Dictionary of the World Health Organization, 2nd ed.Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oliver K, Innvar S, Lorenc T et al. , A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:2.http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP et al. , AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:E839–E842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grimmer K, Dizon JM, Milanese S et al. , Efficient clinical evaluation of guideline quality: development and testing of a new tool. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:63..http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. A Manual from the English-Speaking Caribbean—Developing Food-Based Dietary Guidelines. Santiago, Chile: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA et al. , Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10.http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Whiting P, Savovic J, Higgins JP et al. , ROBIS: A new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;69:225–234.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 1. Guidelines for guidelines. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 9. Grading evidence and recommendations. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katamay SW, Esslinger KA, Vigneault M et al. , Eating well with Canada’s Food Guide (2007): development of the food intake pattern. Nutr Rev. 2007;65:155–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Olivares S, Zacarías I, González C et al. , Development and validation process of food-based dietary guidelines for the Chilean population [Proceso de formulación y validación de las guías alimentarias para la población chilena]. Rev Chil Nutr. 2013;40:262–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Intersectoral Commission on Dietary Guidelines for Costa Rica [Comisión Intersectorial de Guías Alimentarias para Costa Rica]. Updated Technical Guidelines for the Development of the Dietary Guidelines for Costa Ricans [Actualización de lineamientos técnicos para la elaboración de las Guías Alimentarias de la población costarricense]. San José, Costa Rica: Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 29. The German Nutrition Society [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung]. Evidence-Based DGE Guidelines Chronic Disease Prevention: Representation of the General Methodological Method [Evidenzbasierte DGE-Leitlinien zur Prävention chronischer Krankheiten: Darstellung der allgemeinen methodischen Vorgehensweise]. Bonn, Germany: German Nutrition Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance. Updated Process—Dietary Guidelines for Guatemala [Proceso de actualización de las Guías Alimentarias para Guatemala]. Guatemala City, Guatemala: Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Food Safety Authority of Ireland. Scientific Recommendations for Healthy Eating Guidelines in Ireland. Dublin: Food Safety Authority of Ireland; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32. National Food Council. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Public Health Promotion and Prevention of Chronic Diseases—Methodology and Scientific Evidence. Oslo, Norway: Norwegian Directorate of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Konde AB, Bjerselius R, Haglund L et al. , Swedish Dietary Guidelines—Risk and Benefit Management Report. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish National Food Agency; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Federal Office of Public Health and Swiss Society of Nutrition. Swiss Nutrition Policy 2013–2016—Based on the Main Findings of the 6th Swiss Nutrition Report. Bern, Switzerland: Federal Office of Public Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Regional Institute of Public Health in Quidah and Francophone Africa Research Group on the Double Burden of Malnutrition. Benin’s Dietary Guidelines [Guide alimentaire du Benin]. Cotonou, Benin: Francophone Africa Research Group on the Double Burden of Malnutrition; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vorster HH, Badham JB, Venter CS.. An introduction to the revised food-based dietary guidelines for South Africa. S Afr J Clin Nutr. 2013;26:S1–S164. [Google Scholar]

- 37. National Health and Medical Research Council, Department of Health and Ageing. Australian Dietary Guidelines. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Nahar Q, Choudhury S, Faruque MO et al. , Dietary Guidelines for Bangladesh. Dhaka: Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (BIRDEM; ); 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39. National Institute of Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines for Indians—a Manual. Hyderabad, India: Indian Council of Medical Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition. Malaysian Dietary Guidelines. Putrajaya: Ministry of Health Malaysia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 41. New Zealand Ministry of Health. New Zealand Food and Nutrition Guidelines. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Food and Nutrition Research Institute of the Department of Science and Technology (FNRI-DOST). 2012 Nutritional Guidelines for Filipinos [Mga Gabay sa Wastong Nutrisyon Para sa Pilipino]. Taguig City, Philippines: National Nutrition Council; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nutrition Division of the Ministry of Health. Food Based Dietary Guidelines for Sri Lankans .Colombo, Sri Lanka: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries. The Official Dietary Guidelines [De officielle kostråd]. Glostrup, Denmark: Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45. The German Nutrition Society [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ernährung]. 10 Guidelines of the German Nutrition Society (DGE) for a Wholesome Diet [Vollwertig essen und trinken nach den 10 Regeln der DGE]. Bonn, Germany: German Nutrition Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Directorate of Health, Icelandic Nutrition Council. Dietary and Nutrient Guidelines [Ráðleggingar um mataræði og næringarefni]. Reykjavík, Iceland: Directorate of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Department of Health. Your Guide to Healthy Eating Using the Food Pyramid .Dublin, Ireland: Department of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Institute of Public Health of the Republic of Macedonia. Dietary Guidelines for the Population in The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia [Водич за исхрана на населението во Република Македонија]. Skopje, Macedonia: Institute of Public Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 49. The Netherlands Nutrition Centre [Stichting Voedingscentrum Nederland]. Guidelines for Healthy Dietary Choices [Richtlijnen voedselkeuze]. The Hague: Netherlands Nutrition Centre; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Helsedirektoratet. Norwegian Guidelines on Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity [Anbefalinger om kosthold, ernæring og fysisk aktivitet]. Oslo, Norway: Directorate of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Swedish National Food Agency [Livsmedelsverket]. Find Your Way to Eat Greener, Not Too Much and Be Active!. Uppsala, Sweden: Swedish National Food Agency; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Federal Office of Public Health. Sixth Nutrition Report [Sechster Schweizerischer Ernährungsbericht]. Bern, Switzerland: Federal Office of Public Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Public Health England. Your Guide to the Eatwell Plate—Helping you Eat a Healthier Diet. London: Public Health England; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ministry of Health Belize. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Belize. Belmopan, Belize: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Olivares S, Zacarías I, González C.. Dietary Guidelines for the Chilean Population [Guías alimentarias para la población chilena]. Santiago, Chile: Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Intersectoral Commission for Dietary Guidelines [Comision Intersectorial de Guias Alimentarias]. Dietary Guidelines for Costa Rica [Guias Alimentarias para Costa Rica]. San Jose, Costa Rica: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ministry of Health El Salvador Nutrition Unit. Dietary Guidelines for Salvadorian Families [Guías alimentarias para las familias salvadoreñas]. San Salvador, El Salvador: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance. Dietary Guidelines for Guatemala. Recommendations for Healthy Eating [Guías alimentarias para Guatemala. Recomendaciones para una alimentación saludable]. Guatemala City, Guatemala: Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 59. National Food Security Programme of the Ministry of Health. Dietary Guidelines for Honduras—Tips for Healthy Eating [Guías alimentarias de Honduras. Consejos para una alimentación sana]. Tegucigalpa, Honduras: Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Nutrition Unit in the Ministry of Health. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for Jamaica: Healthy Eating—Active Living. Kingston, Jamaica: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Interinstitutional Technical Commission for Panama dietary guidelines [Comision Tecnica Interinstitucional para las Guias Alimentarias de Panama]. Dietary Guidelineas for Panama [Guias Alimentarias para Panama]. Panama City, Panama: Ministry of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62. National Institute of Food and Nutrition. Dietary Guidelines of Paraguay. Asunción, Paraguay: National Institute of Food and Nutrition; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Health Promotion Unit. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for St. Kitts and Nevis. Basseterre, St. Kitts: Ministry of Health, Social Services, Community Development, Culture and Gender Affairs; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 64. US Department of Agriculture and US Department of Health and Human Services. 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ministry of Health Brazil and Center for Epidemiological Research in Nutrition and Health of the University of São Paulo (NUPENS/USP). Dietary Guidelines for the Brazilian Population [Guia alimentar para a população brasileira 2014]. Brasília, Brazil: Ministry of Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66. World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases; Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation .Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 67. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC: American Institute for Cancer Research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Food and Agriculture Organization, World Health Organization. FAO/WHO Technical Consultation on National Food-Based Dietary Guidelines, Cairo, Egypt, 6–9 December 2004. Cairo, Egypt: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Regional Office for the Near East, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Andrews J, Guyatt G, Oxman AD et al. , GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: the significance and presentation of recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:719–725.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Boyd EA, Bero LA.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 4. Managing conflicts of interests. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Edejer TT. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 11. Incorporating considerations of cost-effectiveness, affordability and resource implications. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Fretheim A, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 5. Group processes. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fretheim A, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 15. Disseminating and implementing guidelines. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fretheim A, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 3. Group composition and consultation process. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4: 15.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 7. Deciding what evidence to include. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 2. Priority setting. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 12. Incorporating considerations of equity. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 14. Reporting guidelines. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 16. Evaluation. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Oxman AD, Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 8. Synthesis and presentation of evidence. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 10. Integrating values and consumer involvement. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Schünemann HJ, Fretheim A, Oxman AD.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 13. Applicability, transferability and adaptation. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Fretheim A.. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 6. Determining which outcomes are important. Health Res Policy Sys. 2006;4:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. NHMRC Synthesis and Translation of Research Evidence (SToRE) Advisory Group 2014-16 2015. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about/nhmrc-committees/nhmrc-synthesis-and-translation-research-evidence-store-advisory-group-2014-1. Accessed August 7, 2017.

- 85. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE et al. , GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926.http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. GRADE. The GRADE Working Group. http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/. Accessed November 22, 2017.

- 87. English M, Opiyo N.. Getting to grips with GRADE-perspective from a low-income setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:708–710.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Fervers B, Burgers JS, Voellinger R et al. , Guideline adaptation: an approach to enhance efficiency in guideline development and improve utilisation. BMJ Qual Safety. 2011;20:228–236.http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.043257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Raval AD, Thakker D, Negi H et al. , Association between statins and clinical outcomes among men with prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016; 19:151–162http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/pcan.2015.58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jordan H, Matthan N, Chung M et al. , Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on arrhythmogenic mechanisms in animal and isolated organ/cell culture studies. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004; 92:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Cranney A, Horsley T, O'Donnell S et al. , Effectiveness and safety of vitamin D in relation to bone health. Evid Report/Technol Assess. 2007; 158:1–235. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Balk E, Chung M, Chew P et al. , Effects of soy on health outcomes. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 126. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2005.

- 93. Tsafnat G, Glasziou P, Choong MK et al. , Systematic review automation technologies. Syst Rev. 2014; 3:74..http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-3-74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Smitasiri S, Uauy R.. Beyond recommendations: implementing food-based dietary guidelines for healthier populations. Food Nutr Bull. 2007;28 (1 suppl):S141–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. ADAPTE Collaboration. Guideline Adaptation: A Resouce Toolkit. Version 2.0.2009. http://www.g-i-n.net. Accessed August 13, 2017.

- 96. Campsall P, Colizza K, Straus S et al. , Financial relationships between organizations that produce clinical practice guidelines and the biomedical industry: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002029.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Norris SL, Holmer HK, Ogden LA et al. , Conflict of interest disclosures for clinical practice guidelines in the national guideline clearinghouse. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47343.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Schunemann HJ, Al-Ansary LA, Forland F et al. , Guidelines International Network: principles for disclosure of interests and management of conflicts in guidelines. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:548–553.http://dx.doi.org/10.7326/M14-1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]