ABSTRACT

The histidine kinase CheA plays a central role in signal integration, conversion, and amplification in the bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction pathway. The kinase activity is regulated in chemotaxis signaling complexes formed via the interactions among CheA's regulatory domain (P5), the coupling protein CheW, and transmembrane chemoreceptors. Despite recent advancements in the understanding of the architecture of the signaling complex, the molecular mechanism underlying this regulation remains elusive. An interdomain linker that connects the catalytic (P4) and regulatory domains of CheA may mediate regulatory signals from the P5-CheW-receptor interactions to the catalytic domain. To investigate whether this interdomain linker is capable of both activating and inhibiting CheA, we performed in vivo screens to search for P4-P5 linker mutations that result in different CheA autokinase activities. Several CheA variants were identified with kinase activities ranging from 30% to 670% of the activity of wild-type CheA. All of these CheA variants were defective in receptor-mediated kinase activation, indicating that the natural receptor-mediated signal transmission pathway was simultaneously affected by these mutations. The altered P4-P5 linkers were sufficient for making significant changes in the kinase activity even in the absence of the P5 domain. Therefore, the interdomain linker is an active module that has the ability to impose regulatory effects on the catalytic activity of the P4 domain. These results suggest that chemoreceptors may manipulate the conformation of the P4-P5 linker to achieve CheA regulation in the platform of the signaling complex.

IMPORTANCE The molecular mechanism underlying kinase regulation in bacterial chemotaxis signaling complexes formed by the regulatory domain of the histidine kinase CheA, the coupling protein CheW, and chemoreceptors is still unknown. We isolated and characterized mutations in the interdomain linker that connects the catalytic and regulatory domains of CheA and found that the linker mutations resulted in different CheA autokinase activities in the absence and presence of the regulatory domain as well as a defect in receptor-mediated kinase activation. These results demonstrate that the interdomain linker is an active module that has the ability to impose regulatory effects on CheA activity. Chemoreceptors may manipulate the conformation of this interdomain linker to achieve CheA regulation in the platform of the signaling complex.

KEYWORDS: bacterial chemotaxis, histidine kinase, interdomain linker, kinase regulation

INTRODUCTION

Histidine kinases are common sensors and transducers in signal transduction pathways that mediate adaptive responses in bacteria and fungi, including nutrient acquisition, metabolism, virulence, and cell development (1). Absent from high eukaryotic organisms, they are potential targets for novel antibiotics and fungicides (2, 3). A histidine kinase named CheA is used in the bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction pathway that enables motile bacteria to sense and respond to chemical changes in their environment (4, 5). It plays a central role in signal integration, conversion, and amplification. Working with several other chemotaxis proteins, CheA and its cognate response regulator, CheY, constitute a simple signal transduction system that has been extensively studied for decades and that has become a paradigm for understanding cell signaling in general. Growing evidence indicates that bacterial chemotaxis is essential for the infection process of some pathogens (6–8).

The biased movement of a bacterium toward favorable and away from unfavorable conditions is achieved by the regulation of CheA's kinase activity in chemotaxis signaling complexes that also comprise transmembrane chemoreceptors (also known as methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins [MCPs]) and the coupling protein CheW. The receptor trimers of dimers pack to form hexagonal arrays in the inner membrane (9). Diverse periplasmic domains from different receptors are responsible for signal detection. The state of ligand occupancy is communicated through the membrane, across HAMP (histidine kinase, adenylyl cyclases, MCPs, and phosphatases) domains, and along highly conserved cytoplasmic domains, where the sensory signals are integrated to control the common signal convertor, CheA (5). The apo or repellent-bound receptors activate CheA, while the attractant-bound receptors suppress CheA autophosphorylation (10). Phosphorylated CheA rapidly transfers the phosphoryl group to CheY. The phospho-CheY is able to interact with flagellar motors, resulting in the reversal of the rotation of flagella (default counterclockwise rotation to clockwise rotation) and cell tumbling. Because the net direction of the movement of a bacterium depends upon the frequency of these tumbling events, CheA couples sensory information to the swimming behavior of the bacterium.

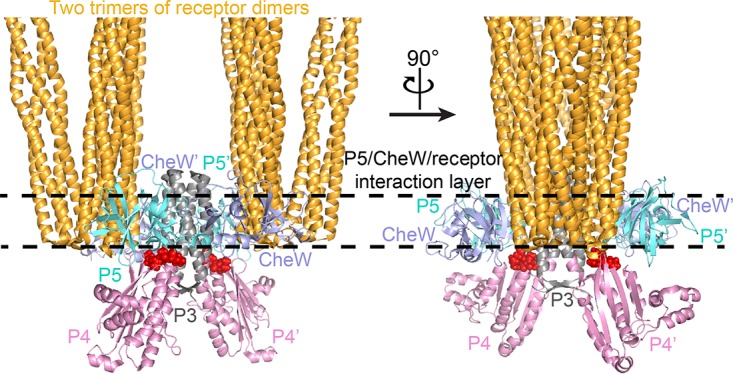

CheA is a dimeric protein with five structural and functional domains: the histidine-containing phosphotransfer domain (P1), the CheY/CheB binding domain (P2), the dimerization domain (P3), the ATP binding/catalytic domain (P4), and the regulatory domain (P5). Two short interdomain linkers connect the P3, P4, and P5 domains, forming a kinase core that is able to phosphorylate a liberated P1 domain in vitro and that supports chemotaxis in vivo when supplied with the P1 domain in trans (11). The structure of the kinase core has been determined (12), and great progress has recently been made in understanding the architecture of the core signaling complex (13–16). The minimal functional unit of the core complex comprises 1 CheA dimer, 2 CheW monomers, and 2 receptor trimers of dimers (17). The CheA dimer binds to two CheW molecules through its two P5 domains (18). In the dimeric CheA-CheW complex, each P5-CheW pair bridges two neighboring receptor trimers of dimers through interactions of the P5 domain and CheW with one receptor dimer in each of the two trimers of dimers (Fig. 1). The four-helix bundle formed by the dimerization of the two P3 domains is positioned between the two receptor trimers of dimers, parallel to their long axes. The two P4 domains of the CheA dimer are positioned below the P5-CheW-receptor interaction layer (Fig. 1) (13, 14, 16). The functional significance of this structural model has been revealed by several recent studies that focus on the protein-protein contacts in this layer (19–23).

FIG 1.

Structural model of core signaling complex. Two trimers of receptor dimers, a CheA kinase core dimer, and two CheW monomers assemble into the minimal unit of receptor signaling (12–18). The P4-P5 linkers are shown in red and in space-filling representation.

Despite advancement in the understanding of the overall architecture of the core complex, a central question remains unanswered: how is the activity of CheA regulated in the signaling complex? Specifically, given the lack of domain-domain interactions among the P3, P4, and P5 domains in the structural model, how can the interactions of the regulatory P5 domain with CheW and chemoreceptors lead to changes in the activity of the catalytic P4 domain? What is responsible for relaying the signal at the P5-CheW-receptor interfaces to the P4 domain? The current structure of the signaling complex does not provide structural details for these questions, presumably due to low resolution. Neither dissociation/association of the signaling complexes nor substantial structural changes were observed in the studies of the signaling complexes that were placed/locked in different signaling states (24–26). Signals are transmitted through receptors by subtle structural and/or dynamical changes (5, 27–32). Since the P4-P5 linker connects the P4 and P5 domains of CheA, it is likely that the structural/dynamic changes in the P5-CheW-receptor interaction layer (19, 20, 22) may affect the conformation of this linker, thereby causing changes in the structure and activity of the P4 domain. The functional importance of this interdomain linker has been revealed by the result that single-amino-acid substitutions in the linker abolished receptor-controlled CheA activation (33). Since the core activity of chemotaxis signaling complexes is the activation of CheA, if this interdomain linker is a key element that enables CheA to adopt different conformations and exhibit different activities as directed by the receptors, some specific changes in this linker should shift CheA toward activating conformations even in the absence of receptor input. Alternatively, other variations in this linker should decrease kinase activity, as some mutant chemoreceptors were found to inhibit CheA activity (34).

To investigate the potential regulatory role of the P4-P5 linker of CheA, we screened the randomized linker mutants in an effort to isolate mutations in the linker that result in different autokinase activities. We identified several CheA variants whose kinase activities ranged from 30% to 670% of the activity of wild-type CheA. All of these CheA variants were defective in receptor-mediated CheA activation, indicating that the natural receptor-mediated signal transmission pathway was simultaneously broken by these mutations. Moreover, the altered P4-P5 linkers were sufficient for making significant changes in the kinase activity even in the absence of the P5 domain. Therefore, this interdomain linker is an active module that has the ability to impose regulatory effects on the activity of the P4 domain. These results suggest that chemoreceptors may manipulate the conformation of the P4-P5 linker to achieve CheA regulation in the platform of the signaling complex.

RESULTS

Isolation of linker mutations.

Oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis was used to randomize the coding region of the P4-P5 linker (amino acid sequence Pro506-Leu507-Thr508-Leu509) in plasmid pPA113, whose CheA expression was tightly controlled by sodium salicylate (35). Mutagenized plasmids were used to transform Escherichia coli K-12 strain RP9540, whose chromosomal cheA and four major MCP chemoreceptor genes (tsr, tar, trg, and tap) were deleted. In the absence of these receptors, the colony size of this strain in semisolid agar can indicate the kinase activity of CheA expressed by a plasmid (35). At a low expression level, receptor-uncoupled CheA is insufficient to maintain a level of phospho-CheY that enables the reversal of flagellar rotation. Thus, the cells of strain RP9540 have little ability to migrate when inoculated into semisolid agar. However, at a sufficiently high expression level, basal CheA autophosphorylation activity is able to generate enough phospho-CheY to cause episodes of clockwise flagellar rotation, resulting in a larger swarm size (Fig. 2). Therefore, to isolate hyperactive cheA mutants, we chose a low sodium salicylate concentration (0.4 μM), at which we expected that their high kinase activities would be able to supply sufficient phospho-CheY to overcome the defect of flagellar switching (at least partially). In contrast, a high inducer concentration (5 μM) was used to screen inactive cheA mutants. At this concentration, wild-type CheA expressed by pPA113 rendered strain RP9540 with improved swarming ability (Fig. 2), while strain RP9540 carrying an inactive cheA mutant would show poorer swarming ability.

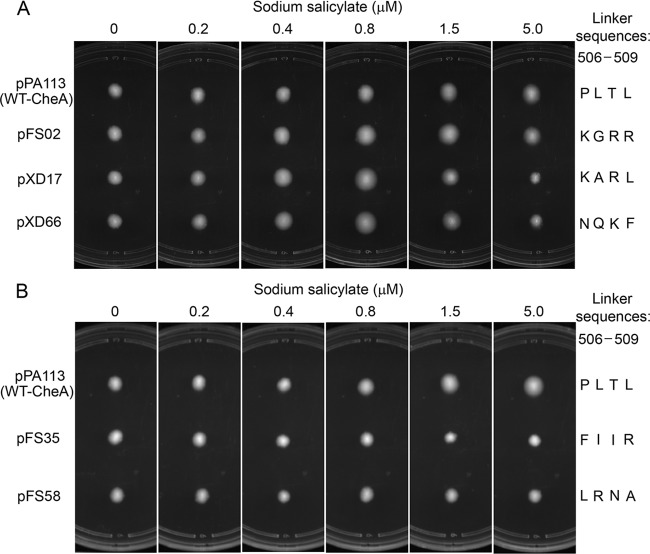

FIG 2.

In vivo tests of the kinase activities of five representative CheA P4-P5 interdomain linker mutants. Mutant plasmids expressing hyperactive (A) and inactive (B) mutant CheA proteins were tested over a range of inducer concentrations for the ability to produce changes in the swarm size of strain RP9540 in semisolid agar.

In semisolid agar, cells that tumble at intermediate frequencies spread faster than do cells that fail to tumble or that tumble incessantly (36). To verify the in vivo activities of the mutant CheA proteins identified at one specific expression level, the swarming abilities of strain RP9540 supported by these mutant plasmids were further tested over a range of inducer concentrations. The kinase activity of a CheA variant can be reflected by the change in the colony size of strain RP9540 as the CheA expression level increases (35): a hyperactive cheA mutant causes an increase in the swarm size followed by a decrease at high expression levels in RP9540; the lower inducer concentration at which the swarm size peaks, the higher activity the mutant CheA protein has. In contrast, an inactive cheA mutant produces no or a smaller increase in the swarm size, and the swarm is always smaller than that produced by wild-type CheA at the same expression level. The sequences of the conspicuous mutant plasmids were identified by DNA sequencing.

With this screening procedure, we found that many mutations in the P4-P5 linker altered CheA kinase activity. Based on their in vivo performance, five representatives were chosen from the isolated mutations, and their in vivo tests are shown in Fig. 2. In terms of spreading ability, strain RP9540 carrying pPA113 that expressed wild-type CheA outperformed the same strain carrying mutant plasmid pFS58 or pFS35 over the tested inducer concentrations (Fig. 2B). Thus, these two mutant CheA proteins (denoted CheA-FS58 and CheA-FS35, whose P4-P5 linker sequences are Leu506-Arg507-Asn508-Ala509 and Phe506-Ile507-Ile508-Arg509, respectively) are less active than wild-type CheA. In contrast, the swarm size of strain RP9540 carrying pFS02 reached its maximum at ∼1.5 μM sodium salicylate (Fig. 2A), indicating that this mutant CheA protein (CheA-FS02, whose P4-P5 linker sequence is Lys506-Gly507-Arg508-Arg509) is more active than wild-type CheA. Strain RP9540 showed the most enhanced spreading ability when it carried mutant plasmid pXD66 or pXD17, whose swarm size peaked at ∼0.8 μM sodium salicylate (Fig. 2A). Thus, the mutant CheA proteins (CheA-XD66 and CheA-XD17, whose P4-P5 linker sequences are Asn506-Gln507-Lys508-Phe509 and Lys506-Ala507-Arg508-Leu509, respectively) expressed by these two plasmids are even more active than CheA-FS02.

In vitro activities of the linker mutants.

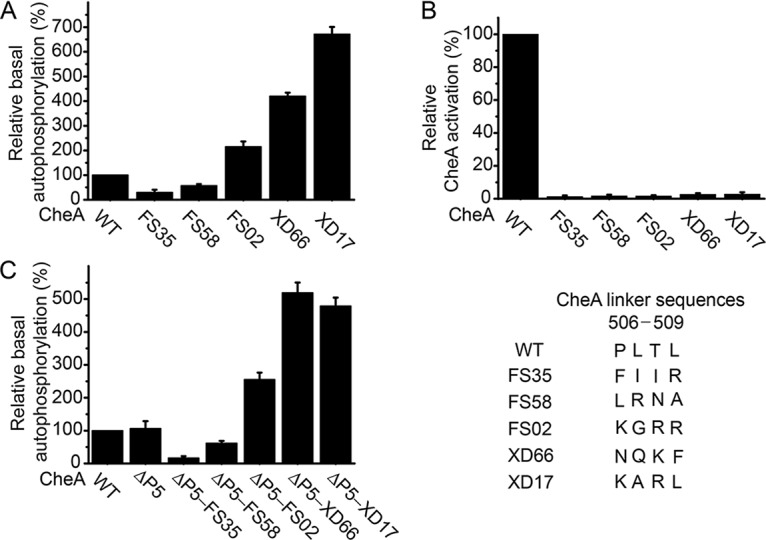

To investigate the effects of these mutations on CheA activity in vitro, we purified these mutant CheA proteins and assayed their autophosphorylation activities. Consistent with the in vivo results, the kinase activities of the mutant CheA proteins CheA-FS35, CheA-FS58, CheA-FS02, CheA-XD66, and CheA-XD17 were 30%, 57%, 220%, 420%, and 670% of the activity of wild-type CheA, respectively (Fig. 3A; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). These results demonstrate that changing the sequence of the P4-P5 linker can impose regulatory effects on the kinase activity of CheA. To evaluate their activation in signaling complexes, these CheA proteins were mixed with CheW- and Tsr-containing membranes. The structure of the signaling complex shows that the P4-P5 linker is not involved in the interactions of CheA with CheW and the receptor (13–16). Indeed, these CheA variants were still be able to form stable ternary complexes with CheW and E. coli chemoreceptor Tsr (Fig. S1). However, all of them were activation defective in vitro (Fig. 3B) and failed to support chemotaxis in vivo (Fig. S2), indicating that the natural receptor-mediated CheA activation pathway was affected by the mutations in the P4-P5 linker. For the hyperactive mutants, the activating influence and the accompanying activation defect by the same mutations suggest that the mutational activation uses the same pathway as the receptor-mediated CheA activation. This contrasts with some previously reported CheA variants. Several single-amino-acid substitutions identified in the P4 domain (the Cys substitution at residue Arg497 of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium CheA [37] and the Leu and Ser substitutions at residue Pro337 of E. coli CheA [38]) resulted in >2.5-fold increases in CheA kinase activity but did not block receptor control, suggesting that the activating effects of these mutations on kinase activity arose independently of the mechanism responsible for receptor-mediated activation. We also notice that the Val substitution at residue Ala622 of the P5 domain of E. coli CheA exhibited an increased kinase activity and activation defect, but its inability to undergo receptor-mediated activation was largely due to its CheW-binding defect (35).

FIG 3.

Effects of mutations in the P4-P5 interdomain linker on the kinase activity of CheA (standard deviation [SD], n = 3) (A), receptor-mediated CheA activation (SD, n = 3) (B), and the kinase activity of the CheA-ΔP5 construct (SD, n = 3) (C). WT, wild type.

Effect of linker mutations in the absence of the P5 domain.

To further explore the functional importance of the P4-P5 linker, we created a CheA-ΔP5 construct that contained the first 4 domains (P1 to P4) of CheA and the P4-P5 linker at the C terminus and replaced its P4-P5 linker with the identified mutant linkers. Unexpectedly, the altered P4-P5 linkers in the context of the CheA-ΔP5 construct made changes in kinase activity similar to those in full-length CheA. The activities of the CheA-ΔP5 mutants CheA-ΔP5-FS35, CheA-ΔP5-FS58, CheA-ΔP5-FS02, CheA-ΔP5-XD66, and CheA-ΔP5-XD17, which each contained the corresponding mutant P4-P5 linker, were 16%, 58%, 240%, 490%, and 450% of the activity of the wild-type CheA-ΔP5, respectively (Fig. 3C and Table S2). Thus, the altered P4-P5 linkers are sufficient for making significant changes in kinase activity even in the absence of the P5 domain. Independence from the P5 domain to affect the kinase activity of CheA indicates that the interdomain linker plays an active role in changing the catalytic ability of the P4 domain and suggests that the interdomain linker is located downstream of the P5-CheW-receptor interaction layer in the signaling pathway.

DISCUSSION

The small free energies provided by the binding of small ligands (such as serine, aspartate, nickel ions, etc.) in chemoreceptors could only drive low-energy transitions. Several studies have suggested that the signal-induced structural/dynamic changes are subtle ones (25, 26, 29). The dynamics of the P4-P5 linker have been previously revealed in the crystal structures of the kinase core (12) and the P4P5-CheW complex (18). Its flexibility is required to reconstruct the structural model of the signaling complexes (14) and has been studied by molecular dynamics simulations (33). Given its functional role revealed in this study, this interdomain linker seems to be a reasonable candidate that is able to take over the subtle structural changes detected in the operational modules of receptor (5, 27–32) and the P5-CheW-receptor interfaces (19, 20, 22). In other words, depending on their signaling states, two receptor trimers of dimers may use the signaling complex as a structural platform to manipulate the conformation of two P4-P5 linkers in a CheA dimer, thereby allosterically regulating the activity of the P4 domain. These linker mutations may affect CheA activity by shifting the conformation of CheA either toward the receptor-activated conformation (for the hyperactive mutants) or toward the receptor-suppressed conformation (for the inactive mutants) in signaling complexes. Structural studies of these CheA mutants may reveal the conformational differences that cause changes in CheA activity and provide mechanistic insight into CheA regulation and receptor signaling.

Despite our efforts to find a highly activated CheA mutant, the maximal unstimulated kinase activities of the mutant proteins were about 7-fold higher than that of the wild type, a level that falls considerably short of the activity of receptor-activated CheA (17). Since the residues of the P4-P5 linker are conserved (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), the linker sequences among CheA proteins from different bacterial species do not provide clues about activating/deactivating mutations in the linker. The new linker sequences we isolated in this study reveal the functional role of the P4-P5 linker, but they lack a common pattern, thus preventing us from assessing the possible role of the residues in the linker. More studies about the structural role of this linker or its potential interaction partner are anticipated to instruct mutations that lead to more activated CheA. It is also possible that the reason for failing to isolate a fully activated CheA mutant lies in the P4-P5 linker itself. CheA, CheW, and chemoreceptor form ultrastable signaling complexes (21, 39) stabilized by multiple protein-protein interactions (Fig. 1). In this context, CheA may be mechanically switched to some specific conformation, outputting the corresponding activity. However, given the high flexibility of the P4-P5 linker, a free CheA could adopt multiple conformational states (12, 18, 33). The mutations in this short flexible linker may not be able to lock free CheA to its fully activated state, only shifting the conformational equilibrium toward the fully activated conformation. Thus, the flexibility of this linker may lead to the failure to isolate a mutant whose activity is close to that of receptor-activated CheA. On the other hand, the failure to obtain a CheA P4-P5 linker mutant as active as receptor-activated CheA implies that CheA regulation is a complex process that involves more determinants. For example, we have previously shown that besides the P4-P5 linker, CheA activation requires further support from the P3-P4 interdomain linker (33). Also, more studies have found that motions of the P4 domain that result from rotations about the P3-P4 and P4-P5 linkers are correlated with the kinase state in signaling complexes (16, 26). These two linkers may facilitate bond breakage and formation that lead to different P4 conformations/dynamics in signaling complexes. Thus, higher activity may require additional changes in the P3-P4 linker. The investigation of a cooperative regulation of CheA by the two interdomain linkers is under way.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of CheA P4-P5 linker mutations.

QuikChange mutagenesis reactions were used to randomize the coding region of CheA's P4-P5 linker (residues 506 to 509) in plasmid pPA113 (35), using the degenerate primer 5′-CGATCCGCATTTTACTGNNKNNKNNKNNKGCCATCCTCGACG-3′ and its complement. Strain RP9540 (35) was transformed with the mutagenized plasmid pool and plated directly into semisolid tryptone agar (10 g/liter tryptone, 5 g/liter NaCl, and 0.27% agar) that had not yet solidified (∼42°C) and that contained 0.4 μM (for hyperactive cheA mutation screen) or 5 μM (for inactive cheA mutation screen) sodium salicylate and 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 18 h.

In hyperactive cheA mutation selection, ∼105 colonies in total were plated directly into semisolid tryptone agar, and the largest 5% of the colonies were selected. The ∼5,000 colonies were restreaked, retested in semisolid agar, and compared with those grown from strain RP9540 that expressed wild-type CheA. Ninety-three candidates that showed consistently better spreading abilities than strain RP9540 that expressed wild-type CheA were further verified in semisolid agar containing various concentrations of sodium salicylate. Finally, 16 colonies were chosen to be sequenced. Fourteen of these 16 mutant CheA proteins exhibited 125% to 220% of the kinase activity of wild-type CheA, and CheA-FS02 was chosen as a representative. Two mutant CheA proteins (CheA-XD66 and CheA-XD17) showed >4 times higher kinase activities than wild-type CheA.

In inactive cheA mutation selection, ∼2 × 104 colonies in total were plated directly into semisolid tryptone agar, and the smallest 5% of the colonies were selected. The ∼1,000 colonies were restreaked, retested in semisolid agar, and compared with those grown from strain RP9540 that expressed wild-type CheA. Seventeen candidates that showed consistently poorer spreading abilities than strain RP9540 that expressed wild-type CheA were further verified in semisolid agar containing various concentrations of sodium salicylate. Finally, 7 colonies were chosen to be sequenced. Except for one isolate that carried nonsense mutations in the linker, the remaining 6 isolates expressed mutant CheA proteins that showed 30% to 60% of the kinase activity of wild-type CheA, and CheA-FS35 and CheA-FS58 were chosen as two representatives.

Protein preparation.

CheA variants (40), CheW (41), and CheY (42) were expressed in strain RP3098 (34) and purified following published protocols; Tsr-containing membranes were prepared as previously described (10).

In vitro reconstitution of signaling complexes.

The assembly of stable signaling complexes with CheA variants, CheW, and transmembrane chemoreceptor Tsr was assayed using a protocol similar to that developed by the Falke laboratory (39). In the presence or absence of 2 μM CheW, 5 μM Tsr and 2 μM CheA variants were mixed in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 100 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10% glycerol) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 180,000 × g for 15 min, and pellets were washed twice by resuspending in a 10-fold excess of buffer A and repelleting. After the final wash, pellets were resuspended in the original volume of buffer A. Samples were then subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

ATPase assay.

The receptor-unstimulated autophosphorylation rates of CheA variants were determined using the ATPase assay described by Ninfa et al. (43).

CheA activation assay.

CheA activation by Tsr-containing membranes was performed and quantified as previously described (10).

In vivo receptor-mediated activation.

The chemotactic abilities of RP9535 (ΔcheA1643) cells carrying mutant pPA113 plasmids were tested on tryptone soft agar, according to the protocol developed by the Parkinson laboratory (35).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. S. Parkinson (University of Utah) for providing strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31400649 and 31670792), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant BK20140477), a Natural Science Research Grant from the Department of Education of Jiangsu Province (grant 14KJB180026), and the Talent Support Program of Yangzhou University (to X.W.) and National Institutes of Health grant GM59544 (to F.W.D.).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00052-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krell T, Lacal J, Busch A, Silva-Jiménez H, Guazzaroni ME, Ramos JL. 2010. Bacterial sensor kinases: diversity in the recognition of environmental signals. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:539–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurosu M, Begari E. 2010. Bacterial protein kinase inhibitors. Drug Dev Res 71:168–187. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bem AE, Velikova N, Pellicer MT, Baarlen Pv Marina A, Wells JM. 2015. Bacterial histidine kinases as novel antibacterial drug targets. ACS Chem Biol 10:213–224. doi: 10.1021/cb5007135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wadhams GH, Armitage JP. 2004. Making sense of it all: bacterial chemotaxis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:1024–1037. doi: 10.1038/nrm1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ, Parkinson JS. 2008. Bacterial chemoreceptors: high-performance signaling in networked arrays. Trends Biochem Sci 33:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Josenhans C, Suerbaum S. 2002. The role of motility as a virulence factor in bacteria. Int J Med Microbiol 291:605–614. doi: 10.1078/1438-4221-00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler SM, Camilli A. 2005. Going against the grain: chemotaxis and infection in Vibrio cholerae. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:611–620. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lertsethtakarn P, Ottemann KM, Hendrixson DR. 2011. Motility and chemotaxis in Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu Rev Microbiol 65:389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briegel A, Ortega DR, Tocheva EI, Wuichet K, Li Z, Chen S, Müller A, Iancu CV, Murphy GE, Dobro MJ, Zhulin IB, Jensen GJ. 2009. Universal architecture of bacterial chemoreceptor arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:17181–17186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905181106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borkovich KA, Kaplan N, Hess JF, Simon MI. 1989. Transmembrane signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis involves ligand-dependent activation of phosphate group transfer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:1208–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garzón A, Parkinson JS. 1996. Chemotactic signaling by the P1 phosphorylation domain liberated from the CheA histidine kinase of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 178:6752–6758. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6752-6758.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilwes AM, Alex LA, Crane BR, Simon MI. 1999. Structure of CheA, a signal-transducing histidine kinase. Cell 96:131–141. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briegel A, Li X, Bilwes AM, Hughes KT, Jensen GJ, Crane BR. 2012. Bacterial chemoreceptor arrays are hexagonally packed trimers of receptor dimers networked by rings of kinase and coupling proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:3766–3771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115719109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Hu B, Morado DR, Jani S, Manson MD, Margolin W. 2012. Molecular architecture of chemoreceptor arrays revealed by cryoelectron tomography of Escherichia coli minicells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:E1481–E1488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200781109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Fleetwood AD, Bayas C, Bilwes AM, Ortega DR, Falke JJ, Zhulin IB, Crane BR. 2013. The 3.2 Å resolution structure of a receptor: CheA:CheW signaling complex defines overlapping binding sites and key residue interactions within bacterial chemosensory arrays. Biochemistry 52:3852–3865. doi: 10.1021/bi400383e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassidy CK, Himes BA, Alvarez FJ, Ma J, Zhao G, Perilla JR, Schulten K, Zhang P. 2015. CryoEM and computer simulations reveal a novel kinase conformational switch in bacterial chemotaxis signaling. Elife 4:e08419. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li M, Hazelbauer GL. 2011. Core unit of chemotaxis signaling complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:9390–9395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104824108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park SY, Borbat PP, Gonzalez-Bonet G, Bhatnagar J, Pollard AM, Freed JH, Bilwes AM, Crane BR. 2006. Reconstruction of the chemotaxis receptor-kinase assembly. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13:400–407. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piasta KN, Ulliman CJ, Slivka PF, Crane BR, Falke JJ. 2013. Defining a key receptor-CheA kinase contact and elucidating its function in the membrane-bound bacterial chemosensory array: a disulfide mapping and mutagenesis Study. Biochemistry 52:3866–3880. doi: 10.1021/bi400385c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natale AM, Duplantis JL, Piasta KN, Falke JJ. 2013. Structure, function, and on-off switching of a core unit contact between CheA kinase and CheW adaptor protein in the bacterial chemosensory array: a disulfide mapping and mutagenesis study. Biochemistry 52:7753–7765. doi: 10.1021/bi401159k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piasta KN, Falke JJ. 2014. Increasing and decreasing the ultrastability of bacterial chemotaxis core signaling complexes by modifying protein-protein contacts. Biochemistry 53:5592–5600. doi: 10.1021/bi500849p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedetta A, Parkinson JS, Studdert CA. 2014. Signalling-dependent interactions between the kinase-coupling protein CheW and chemoreceptors in living cells. Mol Microbiol 93:1144–1155. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piñas GE, Frank V, Vaknin A, Parkinson JS. 2016. The source of high signal cooperativity in bacterial chemosensory arrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113:3335–3340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600216113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gegner JA, Graham DR, Roth AF, Dahlquist FW. 1992. Assembly of an MCP receptor, CheW, and kinase CheA complex in the bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction pathway. Cell 70:975–982. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90247-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Briegel A, Beeby M, Thanbichler M, Jensen GJ. 2011. Activated chemoreceptor arrays remain intact and hexagonally packed. Mol Microbiol 82:748–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07854.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Briegel A, Ames P, Gumbart JC, Oikonomou CM, Parkinson JS, Jensen GJ. 2013. The mobility of two kinase domains in the Escherichia coli chemoreceptor array varies with signalling state. Mol Microbiol 89:831–841. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkinson JS, Hazelbauer GL, Falke JJ. 2015. Signaling and sensory adaptation in Escherichia coli chemoreceptors: 2015 update. Trends Microbiol 23:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falke JJ, Piasta KN. 2014. Architecture and signal transduction mechanism of the bacterial chemosensory array: progress, controversies, and challenges. Curr Opin Struct Biol 29:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Falke JJ, Erbse AH. 2009. The piston rises again. Structure 17:1149–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parkinson JS. 2010. Signaling mechanisms of HAMP domains in chemoreceptors and sensor kinases. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:101–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swain KE, Gonzalez MA, Falke JJ. 2009. Engineered socket study of signaling through a four-helix bundle: evidence for a yin-yang mechanism in the kinase control module of the aspartate receptor. Biochemistry 48:9266–9277. doi: 10.1021/bi901020d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortega DR, Yang C, Ames P, Baudry J, Parkinson JS, Zhulin IB. 2013. A phenylalanine rotameric switch for signal-state control in bacterial chemoreceptors. Nat Commun 4:2881. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Wu C, Vu A, Shea JE, Dahlquist FW. 2012. Computational and experimental analyses reveal the essential roles of interdomain linkers in the biological function of chemotaxis histidine kinase CheA. J Am Chem Soc 134:16107–16110. doi: 10.1021/ja3056694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ames P, Parkinson JS. 1994. Constitutively signaling fragments of Tsr, the Escherichia coli serine chemoreceptor. J Bacteriol 176:6340–6348. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.20.6340-6348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao J, Parkinson JS. 2006. Mutational analysis of the chemoreceptor-coupling domain of the Escherichia coli chemotaxis signaling kinase CheA. J Bacteriol 188:3299–3307. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3299-3307.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wolfe AJ, Berg HC. 1989. Migration of bacteria in semisolid agar. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 86:6973–6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller AS, Kohout SC, Gilman KA, Falke JJ. 2006. CheA kinase of bacterial chemotaxis: chemical mapping of four essential docking sites. Biochemistry 45:8699–8711. doi: 10.1021/bi060580y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tawa P, Stewart RC. 1994. Mutational activation of CheA, the protein kinase in the chemotaxis system of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 176:4210–4218. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.14.4210-4218.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erbse AH, Falke JJ. 2009. The core signaling proteins of bacterial chemotaxis assemble to form an ultrastable complex. Biochemistry 48:6975–6987. doi: 10.1021/bi900641c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stock A, Chen T, Welsh D, Stock J. 1988. CheA protein, a central regulator of bacterial chemotaxis, belongs to a family of proteins that control gene expression in response to changing environmental conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 85:1403–1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gegner JA, Dahlquist FW. 1991. Signal transduction in bacteria: CheW forms a reversible complex with the protein kinase CheA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 88:750–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowry DF, Roth AF, Rupert PB, Dahlquist FW, Moy FJ, Domaille PJ, Matsumura P. 1994. Signal transduction in chemotaxis: a propagating conformation change upon phosphorylation of CheY. J Biol Chem 269:26358–26362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ninfa EG, Stock A, Mowbray S, Stock J. 1991. Reconstitution of the bacterial chemotaxis signal transduction system from purified components. J Biol Chem 266:9764–9770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.