Abstract

Background

Prevention of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) in the young remains a largely unsolved public health problem and sports activity is an established trigger. Although the presence of standard cardiovascular risk factors in the young can link to future morbidity and mortality in adulthood, the potential contribution of these risk factors to SCA in the young has not been evaluated.

Methods

We prospectively ascertained subjects who experienced SCA between the ages of 5 and 34 years in the Portland, Oregon, USA metropolitan area (2002–2015, catchment population ≈1 million). We assessed the circumstances, resuscitation outcomes, and clinical profile of subjects who had SCA by a detailed evaluation of emergency response records, lifetime clinical records, and autopsy examinations. We specifically evaluated the association of standard cardiovascular risk factors and SCA, and sports as a trigger for SCA in the young.

Results

Of 3775 SCAs in all age groups, 186 (5%) occurred in the young (Mean age 25.9 ± 6.8, 67% male). In SCA in the young, overall prevalence was low (29%), and 26 (14%) were associated with sports as a trigger. The remainder (n=160) occurred in other settings categorized as non-sports. Sports-related SCAs accounted for 39% of SCAs in patients aged ≤18, 13% of SCAs in patients aged 19 to 25, and 7% of SCAs in patients aged 25 to 34. Sports-related SCA cases were more likely to present with shockable rhythms, and survival from cardiac arrest was 2.5-fold higher in sports-related vs. non-sports SCA (28% vs. 11%; p=0.05). Overall, the most common SCA-related conditions were sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (31%), coronary artery disease (22%), and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (14%). There was an unexpectedly high overall prevalence of established cardiovascular risk factors (obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking) with ≥1 risk factor in 58% of SCA cases.

Conclusions

Sports was a trigger of SCA in a minority of cases, and, in most patients, SCA occurred without warning symptoms. Standard cardiovascular risk factors were found in over half of patients, suggesting the potential role of public health approaches that screen for cardiovascular risk factors at earlier ages.

Keywords: death, sudden, cardiac, epidemiology, heart arrest, population, prevention & control, risk factors, sports

INTRODUCTION

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is a sudden and unexpected condition in which patients collapse because of the loss of the pulse.1 Despite the widespread deployment of rapid emergency medical services, the mortality rate exceeds 90%, with > 300 000 US lives lost from this condition annually.2 The risk of SCA increases with age, and, as a result, a relatively small proportion occurs in younger subjects (5–34 years of age).3 However, considering the years of potential life lost, SCA in younger individuals is a major public health problem and a devastating event from a societal perspective.4

Prediction and prevention of this condition remains an unsolved challenge because of multiple knowledge gaps. Even in this younger age group, there is a broad spectrum of etiologies.5–9 There is increased recognition that established cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity and hypertension at a young age, lead to increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in older years.10, 11 However, there is little information on how these risk factors may potentially be linked to SCA at a younger age. Out of a need to obtain sufficient numbers of young subjects to analyze, most published studies of SCA in the young were performed by combining cases from disparate population subgroups, resulting in a lack of multi-year studies in single, large communities.

Sports activity is an established trigger of SCA,6 although the absolute number of sports-related SCA cases is likely to be low.12–15 Some existing community-based studies have provided useful information regarding burden and resuscitation outcomes,16, 17 but with limited findings that can improve prediction and prevention of SCA in the young. Access to prospective comprehensive community-wide evaluations would be most useful, but the significant lack of such investigations is explained by the difficulty of prospectively ascertaining adequate numbers of cases, over a sufficient number of years. We conducted a prospective, population-based analysis of SCA in the young over a time period of 14 years, in a single large US community. Our goals were to evaluate the potential role of standard cardiovascular risk factors while also assessing community burden, the role of sports, and the prevalence of SCA warning signs in the young.

METHODS

The authors declare that all supporting data are available within the article.

Case ascertainment

Out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) cases of all ages (2002 – 2015) were identified from the Oregon SUDS (Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study), an ongoing community-based study of SCA in the Portland, Oregon metropolitan area. Oregon SUDS identifies cases of SCA in the community through collaboration with the region’s 2-tiered Emergency Medical Services (EMS) system, the state Medical Examiner’s office, and regional hospitals. Methods for this study have been published previously.3, 18, 19

Definition and Adjudication of SCA

All available medical records are obtained for each potential case of SCA, including the EMS prehospital care report, Medical Examiner’s report, autopsy if available, death certificates from Oregon state vital statistics records, and complete medical records from the region’s hospital systems, including pre-SCA clinical history. Potential cases included deceased subjects and survivors of cardiac arrest, as well. We perform a detailed adjudication for determination of SCA, defined as a sudden, unexpected pulseless condition of likely cardiac origin (if witnessed)2; or if unwitnessed, a sudden unexpected death in an individual seen in normal health within 24 hours of arrest. Approximately one-quarter of initially-identified cases were excluded in the adjudication process because of a non-cardiac etiology for cardiac arrest such as trauma, drug overdose, diabetic coma, or chronic terminal illness (e.g., on home oxygen, or malignancy not in remission). We have previously shown that this prospective, comprehensive method of ascertaining SCA is significantly more specific and complete than a retrospective review that is limited to death certificate data.3 This study was approved by the institutional review boards of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Oregon Health and Science University, and all participating hospital systems, and subjects provided informed consent as directed by these boards.

Source of patient demographics and arrest circumstances

Patient demographics and circumstances of arrest were obtained from the narrative written by EMS personnel on pre-hospital care reports, and from Medical Examiner reports or medical records. We recorded the location and setting of the arrest, the individual’s activity before arrest, warning symptoms before arrest, and resuscitation details, characterized using the Utstein template.20 Information regarding symptoms was obtained from the EMS pre-hospital care report, and other reports if available. If no information regarding pre-arrest symptoms was available, it was treated as missing. Response time was defined as the time between 911 call and EMS arrival at the patient’s side. Outcome of arrest was obtained from the EMS report and Medical Examiner report, hospital records, Oregon State death certificates and the national Social Security Death Index.

Definition of sports activity

Sports activity was defined as an organized team sport or individual athletic activity. SCA events occurring during or within 1 hour after sports activity were categorized as “sports-related SCA”. All other SCA cases were categorized as “non-sports SCA”.

Detailed review of clinical history

Diagnosis of lifetime cardiac disease was based on the review of patient’s medical record and autopsy if available, echocardiographic and angiographic reports, and the analysis of ECG recordings. For patients aged 21 to 34, body mass index (BMI) was the weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared, with obesity defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. For patients aged 5 to 20, sex-specific BMI-for-age charts were used21 to categorize underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity. Diabetes mellitus was defined as a chart history of diabetes mellitus or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents; hyperlipidemia was defined by chart history or use of lipid-lowering medications; hypertension and smoking were defined by chart history. If the chart history was deemed complete, patients were treated as having no history of a cardiovascular risk factor if it was not mentioned. If chart history was inadequate to determine presence or absence, risk factor data was treated as missing.

Assignment of presumptive etiology of SCA

Assignment of etiology of SCA was based on complete autopsy findings, medical workup before arrest, or post-arrest work-up among survivors. For the subset of SCA cases with autopsy (65% of patients who were deceased), we reviewed the autopsy report for evidence of recent or old infarction, coronary evaluation and quantification of stenosis, heart weight, and cardiac conditions including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), aortic stenosis, myocarditis, congenital heart disease, and coronary anomalies. A diagnosis of HCM was assigned after review of the entire autopsy and findings of the medical workup. Echocardiographic left ventricle (LV) wall thickness ≥15mm in diastole with asymmetric septal hypertrophy and without a secondary cause such as aortic stenosis or hypertension was used to diagnose HCM. On autopsy, significant unexplained left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) ≥16 mm with histological evidence of HCM (i.e. myocardial disarray), or characteristic asymmetric LVH was required for HCM diagnosis. Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (SADS) was assigned to cases with no identified cause of SCA despite autopsy or complete medical work-up.22 As with overall cases, any autopsied SCA case with a non-arrhythmic cause of death was excluded (e.g., cardiac tamponade, pulmonary embolism) or if toxicology findings revealed illicit drug use.

ECG Analysis

An archived resting 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) closest prior but unrelated to cardiac arrest, when available, was obtained for the cases; for SCA survivors without prior ECG, recordings obtained at a time remote from the arrest and index hospitalization were also included. Each ECG was systematically reviewed in detail by a clinical cardiac electrophysiologist. Abnormal ECG findings were recorded, and included sinus tachycardia >100bpm; T-wave inversions in 2 adjacent leads other than aVR, aVL, III, and V1 (not including V2 to V3 in children and adolescents); prolonged QTc-interval >460 ms for males and >470 ms for females; left and right atrial abnormalities (defined as deep negative terminal portion of the P wave in V1 or prominent early portion of the P-wave in inferior leads); LVH by Cornell voltage or Sokolow-Lyon criteria; frontal QRS axis < −30° or >100°; delayed QRS transition zone (R-wave amplitude <S-wave amplitude in lead V4); intraventricular conduction delays (QRS duration ≥120ms with or without bundle-branch blocks); pathological Q-waves; and >1 premature ventricular contraction in the recorded ECG.

Statistical analysis

Comparisons of sports-related SCAs and non-sports SCAs were made by using independent samples t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Analyses were performed by using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). All tests were 2-tailed, with p<0.05 used to indicate significance.

RESULTS

Demographics, Presentation and Survival Outcomes

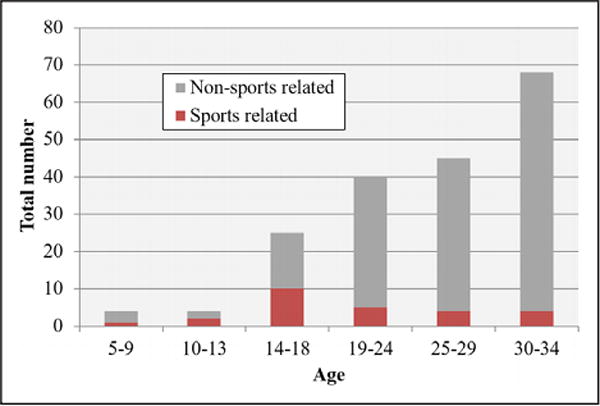

Of 3775 cardiac arrests in all age groups, 186 (5%, 95% confidence interval, 4.2%–5.6%) occurred in the young. Of the latter, 26 (14%; 95% confidence interval, 9%–19%) were associated with sports and the remainder (n=160, 86%, 95% confidence interval, 81%–91%) occurred in non-sport settings. Sports-related SCA accounted for 39% of the patients who were 10 to 18 years of age and 13% of the patients who were 19 to 24 years of age, whereas among patients ≥25 years of age, sports-related SCA made up 7% of total SCAs (Figure 1), and, in both groups, a clear male dominance was observed (81% vs. 65% male; p=0.12; Table 1). No single sport was predominantly responsible for SCA during sports activity (Table 1). The prevalence of SCA without warning symptoms was high in both groups (71%), with only 33% and 28% experiencing pre-arrest symptoms in sports vs. non-sport SCA, respectively (P=0.61, Table 2). In both the sports-related and non-sports groups, angina was the most common symptom, observed in just under half of each group. Of the 7 sport-related SCAs with pre-arrest symptoms, 3 patients experienced angina, 2 palpitations, 1 dizziness only, and 1 abdominal pain. Of the 30 non-sports-related SCAs with symptoms, 14 patients experienced angina, 2 palpitations, 3 dizziness only, and 11 other symptoms (including stomach/abdominal pain or nausea, fatigue, or headache).

Figure 1. Sports-related SCA as a proportion of total SCA in different age groups.

Overall, 86% of SCA in age <35 years occurred in a nonsports setting. SCA indicates sudden cardiac arrest.

Table 1.

SCAs at Age 5 to 34 Years, Overall and Comparing SCAs Triggered by Sports-Related Activities Versus Non-Sports-Related Activities

| Overall (n=186) |

Sports- Related Activity (n=26) |

Non-Sports- Related Activity (n=160) |

P Value (Sports vs Nonsports) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 25.9±6.8 | 20.5±6.8 | 26.7±6.5 | <0.001 |

| Age, y | <0.001 | |||

| 5 – 18 | 33 (18) | 13 (50) | 20 (13) | |

| 19 – 24 | 40 (22) | 5 (19) | 35 (22) | |

| 25 – 34 | 113 (61) | 3 (31) | 105 (66) | |

| Male | 125 (67) | 21 (81) | 104 (65) | 0.12 |

| Race/ethnicity* | 0.30 | |||

| White | 131 (74) | 21 (84) | 110 (73) | |

| Black | 20 (11) | 3 (12) | 17 (11) | |

| Other | 25 (14) | 1 (4) | 24 (16) | |

| Sports type | ||||

| Baseball | 1 (4) | |||

| Basketball | 3 (12) | |||

| Biking | 3 (12) | |||

| Football | 1 (4) | |||

| Gym activity | 4 (15) | |||

| Hiking | 1 (4) | |||

| Horseback riding | 1 (4) | |||

| Rock climbing | 1 (4) | |||

| Running | 4 (15) | |||

| Skiing | 2 (8) | |||

| Soccer | 4 (15) | |||

| Swimming | 1 (4) | |||

| Timing of SCA, n (%) | ||||

| During sports | 24 (92) | |||

| Within 1 h following sports | 2 (8) | |||

Values indicate n (%), unless otherwise indicated. SCA indicates sudden cardiac arrest.

Race/ethnicity was missing for 1 sports-related and 9 other SCAs.

Table 2.

Arrest Circumstances and Symptoms Before SCA for SCAs at Age 5 to 34 Years

| Overall (n=186)* |

Sports- Related Activity (n=26) |

Non-Sports- Related Activity (n=160) |

P value (Sports vs Nonsports) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrest location | ||||

| Home | 121 (65) | 1 (4) | 120 (75) | <0.001 |

| Public | 52 (28) | 25 (96) | 27 (17) | |

| Care facility | 6 (3) | 0 | 6 (4) | |

| Other | 7 (4) | 0 | 7 (4) | |

| Witnessed | 88 (47) | 24 (92) | 64 (40) | <0.001 |

| Prearrest symptoms (within 4 wk) | 37 (29) | 7 (33) | 30 (28) | 0.61 |

| Missing | 57 | 5 | 52 | |

| Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation | ||||

| Overall | 62 (33) | 11 (42) | 51 (32) | 0.37 |

| Among witnessed | 33 (38) | 9 (38) | 24 (38) | 0.99 |

| Response time, min, mean±SD | 7.5±4.2 | 9.6±6.8 | 7.1±3.4 | 0.16 |

| Missing | 78 | 9 | 69 | |

| Response time categories, min | ||||

| 0<4 | 11 (10) | 2 (12) | 9 (10) | 0.50 |

| 4<8 | 58 (54) | 7 (41) | 51 (56) | |

| ≥8 | 39 (36) | 8 (47) | 31 (34) | |

| Resuscitation attempted† | 126 (82) | 21 (100) | 105 (79) | 0.01 |

| Missing | 32 | 5 | 27 | |

| Return of spontaneous circulation | 49 (26) | 10 (38) | 39 (25) | 0.15 |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Survival to hospital discharge | 25 (14) | 7 (28) | 18 (11) | 0.05 |

| Missing | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

Values indicate n (%) unless otherwise stated. Comparisons are shown between SCA triggered by sports-related activity and non-sports-related activities. CPR indicates cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and SCA, sudden cardiac arrest.

Percentages are based on the total number of cases with nonmissing data.

Information regarding whether resuscitation was attempted (yes/no) was available for 154 cases; those missing resuscitation attempted status (n=32) had inadequate data to determine whether resuscitation was or was not attempted.

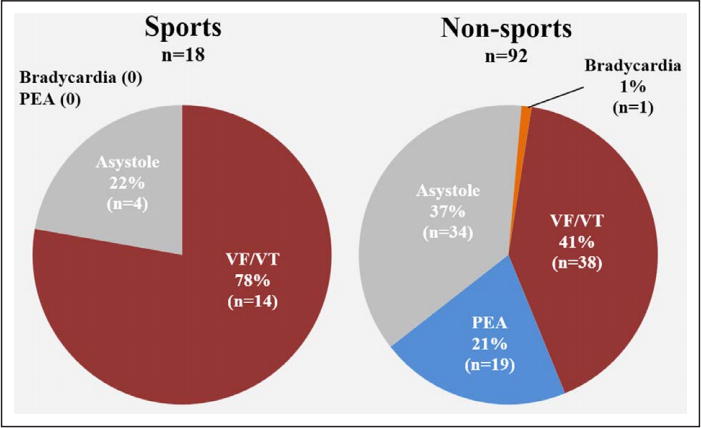

Among the subjects for whom detailed emergency medical response information was available (n=154), resuscitation was attempted in 82%, and overall survival to hospital discharge was 14% (Table 2). Sports-related SCA was significantly more likely to be witnessed (92% vs. 40%). Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed in fewer than half of all cases (42% of sports-related SCA and 32% in non-sports SCA). Resuscitation by EMS personnel was attempted in all of the sports-related SCA cases, and in 79% of the non-sports SCA cases. Sports-related SCA cases were more likely to have favorable resuscitation characteristics (e.g. higher proportion presenting with ventricular fibrillation/pulseless ventricular tachycardia [VF/VT], 78% vs. 41%; p=0.02, Figure 2). Eventually this resulted in higher survival to hospital discharge from SCA in the sports-related SCA than in non-sports SCA cases (28% vs. 11%, p=0.05, Table 2).

Figure 2. Initial rhythm recorded during presentation with sudden cardiac arrest.

Shockable rhythm (VF/VT) was significantly more common among sports-related than non-sports SCAs. Among the subset of 21 sports-related and 105 nonsports-related cases with resuscitation attempted in the field, 18 sports-related and 92 nonsports-related cases had initial rhythm available from ECG recordings in the field or from EMS reports. PEA indicates pulseless electrical activity; SCA, sudden cardiac arrest; VF, ventricular fibrillation; and VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Presumptive Etiology of SCA

Of the 186 cases, detailed clinical evaluation data or autopsy information was available to make a presumptive diagnosis associated with SCA in 133 (72%), as shown in Table 3. Overall, sudden arrhythmic death syndrome (31%), coronary artery disease (CAD) (22%), and HCM (14%) were the most common SCA diagnosis in this 5- to 34-year-old population. Patients with SCA who were >25 years of age were somewhat more likely to have HCM than patients who were 25 to 34 years of age (22% vs. 10%; p=0.07). The proportion of CAD was lower in patients > 25, than in those 25 to 34 years of age (12% versus 27%, P=0.05). Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome was not significantly different by age (39% vs. 26%, respectively, P=0.17).

Table 3.

Presumptive Etiology of SCA Among 133 SCA Cases With Autopsy or Clinical Workup Available

| All Cases (n=133) All Ages |

Ages 5–24 Years (n=49) | Ages 25–34 Years (n=84) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sports-Related Activity (n = 14) |

Non-Sports- Related Activity (n = 35) |

Sports-Related Activity (n = 7) |

Non-Sports- Related Activity (n = 77) |

||

| Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome | 41 (31) | 5 (36) | 14 (40) | 1 (14) | 21 (27) |

| Coronary artery disease | 29 (22) | 1 (7) | 4 (14) | 2 (29) | 21 (27) |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 19 (14) | 7 (50)* | 4 (11)* | 0 | 8 (10) |

| Isolated left ventricular hypertrophy | 9 (7) | 0 | 2 (6) | 0 | 7 (9) |

| Congenital heart disease | 5 (4) | 1 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (14) | 2 (3) |

| Coronary anomaly | 4 (3) | 0 | 3 (9) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Long QT syndrome | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 |

| Acute myocarditis | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (14)† | 0 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy‡ | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (5) |

| Heart failure | 4 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (5) |

| Cardiomyopathy not otherwise specified | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (4) |

| Valvular heart disease | 3 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (4) |

| Idiopathic myocardial fibrosis | 3 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | 1 (14) | 1 (1) |

| Right ventricular dysplasia | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14)† | 0 |

The table includes 133 subjects (108 with autopsy plus 25 without autopsy but with adequate clinical workup to determine cause of arrest). Five sports-related and 48 non-sports-related SCAs had insufficient information to assign a diagnosis. Values displayed are n (%). SCA indicates sudden cardiac arrest.

P=0.007.

P=0.08. All other P values >0.10. P values from Fisher exact test.

One of the 4 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy had postpartum dilated cardiomyopathy with heart failure.

In age-stratified analyses, HCM was the presumptive cause of SCA in 50% (7/14) of sports-related SCAs occurring before 25 years of age, and in 11% (4/35) of nonsports SCAs in this age group (p=0.007) (Table 3). No such difference was seen in the age 25–34 age group, and no other significant differences were observed.

When we compared presumptive cause of SCA by obesity (Table 4), sudden arrhythmic death syndrome was marginally less common in the obese group than in the nonobese group (23% versus 41%; P=0.08), whereas CAD (34% versus 14%; P=0.01) and isolated LVH (17% versus 1%; P=0.002) were significantly more common.

Table 4.

Presumptive Etiology of SCA Among 121 Cases, by Obesity

| Obese, BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (n=47) |

Nonobese, BMI <30 kg/m2 (n=74) |

P Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome | 11 (23) | 30 (41) | 0.08 |

| Coronary artery disease | 16 (34) | 10 (14) | 0.01 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 (11) | 14 (19) | 0.31 |

| Isolated left ventricular hypertrophy | 8 (17) | 1 (1) | 0.002 |

| Congenital heart disease | 0 | 2 (3) | 0.52 |

| Coronary anomaly | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 0.64 |

| Long QT syndrome | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.56 |

| Acute myocarditis | 0 | 2 (3) | 0.52 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy† | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1.0 |

| Heart failure | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1 (2) | 0 | 0.39 |

| Restrictive cardiomyopathy | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

| Mitral valve prolapse | 0 | 3 (4) | 0.28 |

| Valvular heart disease | 0 | 2 (3) | 0.52 |

| Idiopathic myocardial fibrosis | 0 | 3 (4) | 0.28 |

| Right ventricular dysplasia | 0 | 1 (1) | 1.0 |

The table includes 121 of 133 subjects with autopsy or adequate clinical workup to determine cause of arrest who also had body mass index available. For patients aged 21 to 34 years, body mass index was the weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared, with obesity defined as body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. For patients aged 5 to 20 years, sex-specific body mass index-for-age charts were used21 to categorize underweight, normal weight, overweight, and obesity. Values are n (%).

P values from Fisher exact test.

One of the 4 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy had postpartum dilated cardiomyopathy with heart failure.

Comparisons of overall cardiovascular risk profile

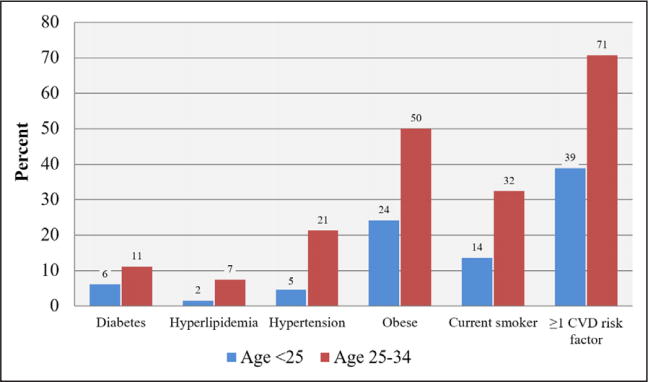

Overall, clinical history or work-up at the time of arrest was available in 174 (94%) of SCA cases. Overweight (BMI, 25–29.9 kg/m2) was observed in 22% of these patients, and 40% were obese, including 22% with a BMI between 30 and 39.9 kg/m2 and 18% who met criteria for extreme obesity, with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2. In this young population, there was a relatively high prevalence of diabetes mellitus (9.2%), hypertension (14.9%), and history of smoking (25%). The majority (58%) of SCA cases had ≥1 established cardiovascular risk factors (obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or smoking). When stratified by age (<25 vs. 25–34), cardiovascular risk factors were more common in the older age group, with significantly higher prevalence of hypertension, overweight or obesity, and smoking in the age 25 to 34 age group (Figure 3). CAD was determined as an etiology in 29 cases following autopsy or medical work-up post-arrest; however, only 3 of these 29 cases had medically-recognized CAD before arrest. Obesity was significantly more prevalent in cases with CAD as an etiology (62% of CAD SCAs were obese vs. 35% of non-CAD cases, P=0.01). The other cardiovascular risk factors were not significantly different between cases with CAD and a non-CAD etiology. Medication data were available for approximately two-thirds of patients with medical records, and were used to corroborate risk factor data (e.g., 73% of patients with diabetes mellitus had documented use of antidiabetic medications in medical charts). Laboratory values were available for only a small proportion of patients (eg, cholesterol, hemoglobin A1c, and brain natriuretic peptide were available for ≤9 of the total 186 patients), but when available, were consistent with risk factors noted in charts (eg, all 4 of 16 diabetic patients with hemoglobin A1c available were in the diabetic range; only 1 of 158 nondiabetic patients had hemoglobin A1c available, and it was normal.)

Figure 3. Prevalence of established cardiovascular risk factors in young subjects who experienced SCA.

Information regarding cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors was available for 174 patients with SCA, whereas BMI was available for 136 patients. Total CVD risk factors (diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, obesity) were calculated among the latter subset. BMI indicates body mass index; and SCA, sudden cardiac arrest.

ECG Findings

Twenty-three (12%) of the SCA cases had an ECG available for analysis (mean age 25±7 years, 57% female), 14 (61%) of these were recorded before arrest. Eighteen (78%) of the 23 ECGs were abnormal. Only 2 (9%) ECGs were completely normal, and an additional 3 ECGs had sinus tachycardia as the only abnormality. The most common ECG abnormalities observed were sinus tachycardia (39%), abnormal T-wave inversions (30%), prolonged QT-interval (26%), left/right atrial abnormality (22%), LVH (17%), abnormal frontal QRS axis (17%), delayed QRS-transition zone in precordial leads (13%), pathological Q-waves (13%), intraventricular conduction delays (9%), and multiple premature ventricular contractions (9%). Cardiac conditions responsible for SCA in the 23 patients with ECGs available at any time were long-QT syndrome (n=3), cardiomyopathies (n=4), congenital heart disease (n=3), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (n=3) and coronary artery disease (n=3); in 5 cases an underlying cause of SCA could not be determined in 5 cases. However, in 9 (64%) of 14 cases with ECG recorded before arrest, cardiac disease had not been diagnosed before SCA.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the association of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in SCA in the young from a single large US community, over multiple years. Five percent of all SCA cases affected the young (5–34 years of age), and only 14% of SCA cases in the young occurred during sports activity. The vast majority of SCA cases in the young (71%) occurred without prior warning symptoms. Sports-related SCA cases were more likely to present with shockable rhythms, and to survive their cardiac arrests. Of the multiple sports settings where patients presented, there was no single predominant sporting activity associated with SCA. The overall prevalence of established cardiovascular risk factors in these SCA cases in the young were significantly higher than previously anticipated, 58% with at least 1 risk factor and 39% prevalence of obesity.

An earlier study from France reported that only 6% of sports-related SCA occurred in young competitive athletes between the ages of 15 and 35 years.13, 18 The present study extended these observations to all young individuals that suffered SCA in a large community. We report that the relatively small proportion of sports-related SCA (14%) was dwarfed by SCA (86%) in non-sports settings. This is in accordance with a previous nationwide study of young SCA in Denmark that reported a small proportion of sudden deaths in the young (11%) occurring during exercise or organized sports activity.9 However, other retrospective studies have reported a higher prevalence of sports as a trigger of SCA (24%–33%).6–8 Although sports remain an important trigger of SCA and were not able to differentiate between competitive versus non-competitive athletes. However, even among competitive athletes, 40% of SCAs occur at rest.23 While sports remains an important trigger of SCA, our findings suggest that an equal emphasis is required on SCA prediction and prevention in non-sports settings.

Several recent studies have described the underlying pathology of SCA in the young in different age groups and populations, with a relatively similar distribution of primary ventricular arrhythmia syndromes, coronary disease, HCM, and LVH as observed in the overall Oregon SUDS population.5, 6, 23–25 However, the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors SCA in the young has significant clinical and public health implications. At least 58% of overall SCA cases had an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease such as diabetes mellitus, hyerptension, and obesity. In fact, 61% of patients were obese or overweight and 18% met criteria for extreme obesity, with a BMI ≥40 kg/m2. There was a sizeable subgroup with coronary disease and LVH, especially among the patients who were obese. In contrast, cases with primary ventricular arrhythmia syndromes or HCM, constituted a smaller proportion of cases.

The Bogalusa Heart Study has provided important information linking cardiovascular risk factors at early ages to future cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. In 204 subjects age 2 to 39 years of age who had suffered unnatural deaths largely from trauma, postmortem findings of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis correlated with the presence of cardiovascular risk factors.10 Being overweight and obese is associated with various risk factors even among young children.11 Our findings suggest the potential important contribution of classical cardiovascular risk factors to SCA occurrence at younger ages. Published autopsy studies indicate that 6–10% of all sudden deaths in the <35 age group have LVH on postmortem examination with an otherwise normal heart and no identifiable etiologies for sudden cardiac death.5, 9 The association between LVH and sudden cardiac death has long been acknowledged in adults but has not been well characterized in children and youth.26 Especially with the rising prevalence of childhood obesity and hypertension,27, 28 an emphasis on early preventive interventions that lower cardiovascular risk factors may make a significant impact on the burden of SCA in the young. Furthermore, our subgroup analysis of the obese SCA cases (Table 4) showed that both CAD and LVH were significantly more common in comparison with the nonobese cases. These observations confirm the relative importance of a comprehensive approach to SCA prevention in the young.29 Our finding that at least subtle ECG abnormalities could be detected in the majority of SCA in the young is intriguing in the context of SCA prevention, but also may be partly influenced by selection bias.

The relatively low proportion of young SCA cases in the young (5 to 34 years of age) with warning signs (29%) is a disturbing finding, especially in comparison with middle-aged subjects where at least 50% of the patients experience warning signs before cardiac arrest.30 It is possible that these important age-related differences are attributable to differences in etiology and substrate of SCA. For example, young patients are more likely to have SCA as a manifestation of conditions such as sudden arrhythmic death syndrome or HCM, and older patients have a higher likelihood of coronary disease as an important component. This would suggest that SCA screening questionnaires reliant on symptoms alone may not be effective for risk stratification in young patients. However, among ages 1–18, the Danish national database has reported a higher prevalence of warning symptoms before SCA, in the range of 50%.31

Our findings of higher survival following SCA in sports than in nonsports settings (28% vs 11%) is consistent with published studies,19 and is likely to be explained by a higher prevalence of factors favorable to successful resuscitation. Sports-related SCA was significantly more likely to be witnessed, and resuscitation was attempted in all cases. Sports-related SCA cases were more likely to have favorable characteristics likely coinciding with less down time before the 911 call was made. Specifically, the proportion of patients presenting with shockable rhythm were nearly twice as high in sports-related vs. non-sports SCA. However, given the relatively high proportion of witnessed cases, the overall rates of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in both subgroups (42% in sports-related SCA and 32% in non-sports SCA) would be considered disappointingly low. Although many of these cases may have occurred before the current era, before the now well-established role of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the resuscitation armamentarium, ongoing education and enhanced awareness of the benefits of bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the young is warranted.

Limitations

SCA cases were ascertained prospectively, but, as expected for community-based studies, analysis of clinical data could only be performed from the information that was available. Because SCA occurred without warning in the majority (71%) of young subjects, not all had the same level of evaluation by healthcare providers before their SCA event, especially in the context of possible heart disease. In this study, we did not have access to consistently reported family history of premature CAD or sudden cardiac death, and therefore could not evaluate its importance for SCA in the young. Fortunately, information from previous medical records, or SCA setting or detailed autopsy, was available for the majority of subjects (clinical history and/or detailed clinical evaluation/autopsy in 94%). In addition, our definition of sports-related SCA was based on the objective of identifying the prevalence of sports activity as a trigger of SCA, and is not synonymous with SCA in athletes. It is likely that some individuals included in the non-sports SCA group could have been athletes who were sedentary at the time of their SCA; in addition, some individuals in the sports-related SCA group may not have been accustomed to habitual exercise.

Conclusions

These findings have implications for public health policy and prevention approaches to reduce SCA in the young and improve outcomes at the community level. SCA occurred in the absence of warning symptoms in the vast majority of young patients, and sports were a trigger for SCA in a small minority of cases. There was an unexpected high prevalence of standard cardiovascular risk factors in the young, all of which are amenable to primordial prevention. Although more research is needed, this study highlights the importance of prevention efforts that extend beyond pre-participation athletic screening and could be applied to routine preventive visits for children and young adults. Screening and management of conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia could have a significant beneficial impact on SCA in the young.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

What is new?

In this population-based study of out-of-hospital sudden cardiac arrest from a single large US community followed for 13 years, 5% of cases occurred among young residents age 5 to 34 years of age.

Among the young, there was an unexpectedly high prevalence of classical cardiovascular risk factors (obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking) with ≥1 risk factor observed in 58%, obesity being the most common.

Less than one-third had warning symptoms before their lethal event, and sports activity was a trigger in only 14% of young cases.

What are the clinical implications?

Standard cardiovascular risk factors, especially obesity, may play a larger role in sudden cardiac arrest among the young than previously recognized.

Efforts to reduce cardiovascular risk in the young are known to translate into reduction of adult cardiovascular disease burden, but these findings suggest that the benefit could extend to sudden cardiac arrest in younger age groups.

Because the majority of cases did not experience warning symptoms, significantly more work is needed to improve the sudden cardiac arrest risk stratification process in the younger population.

Acknowledgments

The authors remain indebted to all study subjects, emergency providers, and community partners whocontinue to make the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study possible. This study is dedicated to the memory of Kirpal S. Chugh MD (1932–2017).

Sources of Funding:

This study was funded, in part, by National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant R01 HL126938 to Dr Chugh. Dr Chugh holds the Pauline and Harold Price Chair in Cardiac Electrophysiology at Cedars-Sinai, Los Angeles.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Evanado A, Kehr E, Al Samara M, Mariani R, Gunson K, Jui J. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: Clinical and research implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;51:213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishman GI, Chugh SS, Dimarco JP, Albert CM, Anderson ME, Bonow RO, Buxton AE, Chen PS, Estes M, Jouven X, Kwong R, Lathrop DA, Mascette AM, Nerbonne JM, O'Rourke B, Page RL, Roden DM, Rosenbaum DS, Sotoodehnia N, Trayanova NA, Zheng ZJ. Sudden cardiac death prediction and prevention: Report from a national heart, lung, and blood institute and heart rhythm society workshop. Circulation. 2010;122:2335–2348. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.976092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, Stecker EC, John BT, Thompson B, Ilias N, Vickers C, Dogra V, Daya M, Kron J, Zheng ZJ, Mensah G, McAnulty J. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: Multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate-based review in a large u.S. Community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stecker EC, Reinier K, Marijon E, Narayanan K, Teodorescu C, Uy-Evanado A, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Public health burden of sudden cardiac death in the united states. Circulation. Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2014;7:212–217. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.001034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Margey R, Roy A, Tobin S, O'Keane CJ, McGorrian C, Morris V, Jennings S, Galvin J. Sudden cardiac death in 14- to 35-year olds in ireland from 2005 to 2007: A retrospective registry. Europace. 2011;13:1411–1418. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer L, Stubbs B, Fahrenbruch C, Maeda C, Harmon K, Eisenberg M, Drezner J. Incidence, causes, and survival trends from cardiovascular-related sudden cardiac arrest in children and young adults 0 to 35 years of age: A 30-year review. Circulation. 2012;126:1363–1372. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.076810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pilmer CM, Kirsh JA, Hildebrandt D, Krahn AD, Gow RM. Sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents between 1 and 19 years of age. Heart rhythm. 2014;11:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pilmer CM, Porter B, Kirsh JA, Hicks AL, Gledhill N, Jamnik V, Faught BE, Hildebrandt D, McCartney N, Gow RM, Goodman J, Krahn AD. Scope and nature of sudden cardiac death before age 40 in ontario: A report from the cardiac death advisory committee of the office of the chief coroner. Heart rhythm. 2013;10:517–523. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winkel BG, Holst AG, Theilade J, Kristensen IB, Thomsen JL, Ottesen GL, Bundgaard H, Svendsen JH, Haunso S, Tfelt-Hansen J. Nationwide study of sudden cardiac death in persons aged 1–35 years. Eur heart J. 2011;32:983–990. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berenson GS, Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Newman WP, 3rd, Tracy RE, Wattigney WA. Association between multiple cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in children and young adults. The bogalusa heart study. New Eng J Med. 1998;338:1650–1656. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199806043382302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman DS, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: The bogalusa heart study. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1175–1182. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, Lee IM, Hennekens CH, Manson JE. Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. New Eng J Med. 2000;343:1355–1361. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marijon E, Tafflet M, Celermajer DS, Dumas F, Perier MC, Mustafic H, Toussaint JF, Desnos M, Rieu M, Benameur N, Le Heuzey JY, Empana JP, Jouven X. Sports-related sudden death in the general population. Circulation. 2011;124:672–681. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.008979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts WO, Stovitz SD. Incidence of sudden cardiac death in minnesota high school athletes 1993–2012 screened with a standardized pre-participation evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1298–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Risgaard B, Winkel BG, Jabbari R, Glinge C, Ingemann-Hansen O, Thomsen JL, Ottesen GL, Haunso S, Holst AG, Tfelt-Hansen J. Sports-related sudden cardiac death in a competitive and a noncompetitive athlete population aged 12 to 49 years: Data from an unselected nationwide study in denmark. Heart rhythm. 2014;11:1673–1681. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins DL, Everson-Stewart S, Sears GK, Daya M, Osmond MH, Warden CR, Berg RA Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium I. Epidemiology and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in children: The resuscitation outcomes consortium epistry-cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2009;119:1484–1491. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moler FW, Donaldson AE, Meert K, Brilli RJ, Nadkarni V, Shaffner DH, Schleien CL, Clark RS, Dalton HJ, Statler K, Tieves KS, Hackbarth R, Pretzlaff R, van der Jagt EW, Pineda J, Hernan L, Dean JM Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research N. Multicenter cohort study of out-of-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:141–149. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fa3c17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Balaji S, Uy-Evanado A, Vickers C, Mariani R, Gunson K, Jui J. Population-based analysis of sudden death in children: The oregon sudden unexpected death study. Heart rhythm. 2009;6:1618–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marijon E, Uy-Evanado A, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Narayanan K, Jouven X, Gunson K, Jui J, Chugh SS. Sudden cardiac arrest during sports activity in middle age. Circulation. 2015;131:1384–1391. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs I, Nadkarni V, Bahr J, Berg RA, Billi JE, Bossaert L, Cassan P, Coovadia A, D'Este K, Finn J, Halperin H, Handley A, Herlitz J, Hickey R, Idris A, Kloeck W, Larkin GL, Mancini ME, Mason P, Mears G, Monsieurs K, Montgomery W, Morley P, Nichol G, Nolan J, Okada K, Perlman J, Shuster M, Steen PA, Sterz F, Tibballs J, Timerman S, Truitt T, Zideman D International Liaison Committee on R, American Heart A, European Resuscitation C, Australian Resuscitation C, New Zealand Resuscitation C, Heart, Stroke Foundation of C, InterAmerican Heart F, Resuscitation Councils of Southern A, Arrest ITFoC, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation O. Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: Update and simplification of the utstein templates for resuscitation registries: A statement for healthcare professionals from a task force of the international liaison committee on resuscitation (american heart association, european resuscitation council, australian resuscitation council, new zealand resuscitation council, heart and stroke foundation of canada, interamerican heart foundation, resuscitation councils of southern africa) Circulation. 2004;110:3385–3397. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147236.85306.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Body mass index-for-age percentiles (2 to 20 years: boys; 2 to 20 years: girls). Developed by the national center for health statistics, in collaboration with the national center for chronic disease prevention and health promotion. 2000 Http://www.Cdc.Gov/growthcharts.

- 22.Behr ER, Dalageorgou C, Christiansen M, Syrris P, Hughes S, Tome Esteban MT, Rowland E, Jeffery S, McKenna WJ. Sudden arrhythmic death syndrome: Familial evaluation identifies inheritable heart disease in the majority of families. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:1670–1680. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Robertus JL, Dhutia H, Steriotis AK, Tome M, Mellor G, Merghani A, Malhotra A, Behr E, Sharma S, Sheppard MN. Etiology of sudden death in sports: Insights from a united kingdom regional registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2108–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bagnall RD, Weintraub RG, Ingles J, Duflou J, Yeates L, Lam L, Davis AM, Thompson T, Connell V, Wallace J, Naylor C, Crawford J, Love DR, Hallam L, White J, Lawrence C, Lynch M, Morgan N, James P, du Sart D, Puranik R, Langlois N, Vohra J, Winship I, Atherton J, McGaughran J, Skinner JR, Semsarian C. A prospective study of sudden cardiac death among children and young adults. New Eng J Med. 2016;374:2441–2452. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harmon KG, Asif IM, Maleszewski JJ, Owens DS, Prutkin JM, Salerno JC, Zigman ML, Ellenbogen R, Rao AL, Ackerman MJ, Drezner JA. Incidence, cause, and comparative frequency of sudden cardiac death in national collegiate athletic association athletes: A decade in review. Circulation. 2015;132:10–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.015431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chugh SS. Approach to unexplained sudden death in the young: Proactive during life and prospective at death. Europace. 2011;13:1364–1365. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ebbeling CB, Pawlak DB, Ludwig DS. Childhood obesity: Public-health crisis, common sense cure. Lancet. 2002;360:473–482. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09678-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorof J, Daniels S. Obesity hypertension in children: A problem of epidemic proportions. Hypertension. 2002;40:441–447. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000032940.33466.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aro AL, Chugh SS. Prevention of sudden cardiac death in children and young adults. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2017 Jun;45:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marijon E, Uy-Evanado A, Dumas F, Karam N, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, Narayanan K, Gunson K, Jui J, Jouven X, Chugh SS. Warning symptoms are associated with survival from sudden cardiac arrest. Ann intern med. 2016;164:23–29. doi: 10.7326/M14-2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winkel BG, Risgaard B, Sadjadieh G, Bundgaard H, Haunso S, Tfelt-Hansen J. Sudden cardiac death in children (1–18 years): Symptoms and causes of death in a nationwide setting. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:868–875. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]