Abstract

Objective

Wound monocyte-derived macrophage plasticity controls the initiation and resolution of inflammation that are critical for proper healing, however, in diabetes, the resolution of inflammation fails to occur. In diabetic wounds, the kinetics of blood-monocyte recruitment and the mechanisms that control in vivo monocyte/macrophage differentiation remain unknown.

Approach and Results

Here, we characterized the kinetics and function of Ly6CHi[Lin− (CD3−CD19−NK1.1−Ter-119−)Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin− (CD3−CD19−NK1.1−Ter-119−)Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophage subsets in normal and diabetic wounds. Using flow-sorted tdTomato-labeled Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages, we show Ly6CHi cells transition to a Ly6CLo- phenotype in normal wounds, whereas in diabetic wounds, there is a late, second influx of Ly6CHi cells that fail transition to Ly6CLo. The second wave of Ly6CHi cells in diabetic wounds corresponded to a spike in MCP-1 and selective administration of anti-MCP-1 reversed the second Ly6CHi influx and improved wound healing. To examine the in vivo phenotype of wound monocyte/macrophages, RNA-seq-based transcriptome profiling was performed on flow-sorted Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] cells from normal and diabetic wounds. Gene transcriptome profiling of diabetic wound Ly6CHi cells demonstrated differences in pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes compared to controls.

Conclusions

Collectively, these data identify kinetic and functional differences in diabetic wound monocyte/macrophages and demonstrate that selective targeting of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages is a viable therapeutic strategy for inflammation in diabetic wounds.

Keywords: Inflammation, Gene Expression and Regulation, Diabetes/Type II, Animal Models of Human Disease

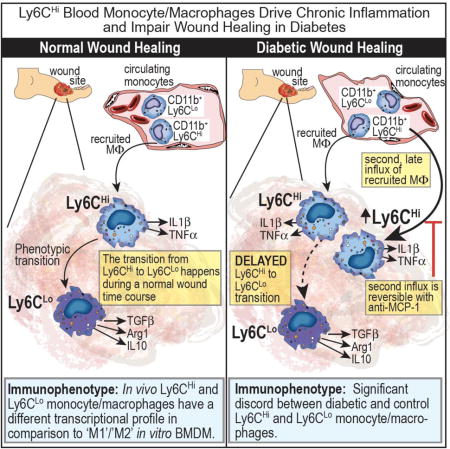

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Impaired wound healing in diabetes is presently the leading cause of lower extremity amputation in the United States and costs the healthcare system over $19 billion dollars annually. Importantly, amputation is associated with a 50% mortality rate at 5-years, a survival rate worse than most cancers 1, 2. Impaired wound healing in diabetes is multifactorial due to a combination of peripheral artery disease (PAD), peripheral neuropathy, inflammation and altered immune cell function 3. PAD is present in over half of patients with diabetic wounds and contributes significantly to impaired healing 4. Persistent, uncoordinated inflammation is a hallmark of chronic non-healing wounds in diabetes 5. Our lab and others have found increased inflammatory macrophages in diabetic wounds, when anti-inflammatory macrophages should predominate to help drive tissue repair, however the mechanisms that sustain the inflammatory macrophage phenotype in diabetic wounds has not been identified 5-12.

The recruitment of circulating blood monocytes to the site of tissue injury plays a critical role in tissue repair through the coordination of inflammation. The precise timing of both the initiation and resolution of inflammation is essential for restoring tissue integrity. The first phase of the inflammatory response is destructive to the tissue and promotes clearance of invading pathogens, while the second phase is a resolution phase where tissue repair ensues 13, 14. For this reason, inflammation is an adaptive process that is necessary to maintain tissue homeostasis 15-17. In the absence of precise programmed inflammation, pathologic non-healing ensues 6, 10, 18-20.

Infiltrating blood monocyte-derived macrophages (monocyte/macrophages) are critical for the initial inflammatory phase of wound healing and play a key role in the orchestration of subsequent phases 13, 21-23. Blood monocytes originate from macrophage-dendritic cell precursors in the bone marrow and ultimately differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) in the tissues 22, 24, 25. Given the shared origin between these more differentiated cell progeny, there has been considerable debate regarding the definitions of these separate cell populations since they retain many of the same surface markers and display overlapping functions 26. In addition, these definitions are further complicated by the recent discovery of “resident” macrophages (CD11b+/F4/80+) which populate the tissues prior to birth and persist through self-replication 27. While there is some literature on the role of resident macrophages and DCs in wound healing, there is growing evidence that infiltrating monocyte/macrophages provide the mandatory drive for acute inflammation and subsequently orchestrate the process of repair 10, 14, 21, 22, 28-33. Despite this evidence of the importance of recruited blood monocyte/macrophages, due to lack of consensus definitions and the recent realization that many of the markers previously used to define recruited monocyte/macrophages actually label resident macrophages, few studies have directly examined the in vivo characteristics of the true recruited monocyte/macrophage population. Amongst blood monocytes, specific identifiable subsets with distinct effector functions have now been identified 34, 35. For instance, Ly6CHi(Gr1HiCCR2+CX3CR1Lo) have been shown to promote inflammation, while Ly6CLo(Gr1LoCCR2−CX3CR1Hi) monocytes are more regenerative 13, 21-23, 30-32, 34, 36. Human correlates for these cells are well described and consist of CD14+CD16− and CD14−CD16+ monocytes matched with Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo murine monocytes, respectively 13, 34, 37, 38.

Although many in vitro studies using monocyte/macrophages have demonstrated high plasticity, little is known regarding wound in vivo cell plasticity 26. Unfortunately the majority of wound healing literature to date, has relied on in vitro definitions of ‘M1’ and ‘M2’ macrophages, making the application to in vivo studies purely speculative 7. While significant strides have been made in recognizing the contribution of blood monocyte-derived macrophages to tissue repair, it remains challenging to study monocyte/macrophage polarity/plasticity in vivo due to a lack of consensus on nomenclature, cell-marker definitions, and debate over effector-cell origin 7, 26. Hence, a careful evaluation of infiltrating monocyte/macrophage subsets in wound granulation tissue is necessary to effectively compare monocyte/macrophage plasticity in both normal and diabetic tissue.

In order to first define the kinetics of blood monocyte/macrophage subsets in normal and diabetic wound healing, we evaluated Ly6CHi[Lin-(CD3−CD19−NK1.1−Ter-119−)Ly6G−CD11b+] (CD11b+Ly6CHi) and Ly6CLo[Lin− (CD3−CD19−NK1.1−Ter-119−)Ly6G−CD11b+] (CD11b+Ly6CLo) cell influx into murine wound granulation tissue over time and performed RNA-seq based transcriptome profiling of sorted Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo cells from both diabetic and non-diabetic murine wounds. We found that during normal healing, CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages are present within 48 hours of injury and rapidly transition to CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages. Interestingly, in diabetic wounds, there is a second influx of Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages during the reparative phase that persists in the tissue and using adoptive transfer of flow-sorted tdTomato-labeled CD11b+Ly6CHi cells, we found that the Ly6CHi to Ly6CLo phenotype transition is delayed in diabetic wounds. Further, the RNA-seq data from wound monocyte/macrophages was compared to established in vitro macrophage definitions, in order to determine the relevance of this traditional nomenclature to in vivo monocyte/macrophages. Our findings suggest that in normal wounds, CD11b+ Ly6CHi infiltrating monocyte/macrophages correlate well with the classical in vitro M1[LPS,IFNγ] macrophage definition, in terms of both inflammatory mediator production and consensus gene transcriptome analysis. Additionally, we demonstrate that CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages from diabetic wounds differ significantly in their expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes when compared to wild type controls. Finally, we identify that selective modulation of the second CD11b+Ly6CHi cell influx in diabetic wounds improves wound healing without the adverse effect of global monocyte depletion. These findings extend mechanistic insight into the dynamic functions of monocyte-derived macrophages during both normal and diabetic tissue repair.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Details for major experimental resources can be found in supplement table I.

Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained in breeding pairs at the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory and Animal Medicine (ULAM). Male offspring were maintained on a standard normal rodent diet (ND) (13.5% kcal saturated fat, 28.5% protein, 58% carbohydrate; Lab Diet) or standard high fat diet (HFD) (60% kcal saturated fat, 20% protein, 20% carbohydrate; Research Diets,Inc.) for 12 weeks to induce the diet-induced obese (DIO) model of type 2 diabetes (T2D) as previously described39. Only male C57BL/6 mice develop obesity/glucose intolerance on HFD, thus females cannot be used as a model of obesity/insulin resistance39. mT/mG mice (Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Number of mice used per experiment can be found in the figure legend of each corresponding experiment. All animals underwent procedures at 20–32 weeks of age with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approval.

Wound Model

Mice were anesthetized, dorsal fur was removed with Veet™ hair removal cream, and the skin was cleaned with sterile water. Full-thickness 4mm punch biopsies were used to create wounds on the mid-back as described previously12.

Assessment of Wound Healing

Wound healing was monitored daily using digital photography with an 8mp iPad camera as previously described10. Wound areas were calculated using an internal scale and NIH ImageJ software. Images were evaluated by two independent observers.

Wound Cell Isolation

Wounds were harvested with a 6mm punch biopsy to afford a 1–2 mm margin. Wounds were chopped, digested with Liberase TL (Sigma-Aldrich; Cat. 5401020001)/DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich; Cat. 9003-98-9) and plunged through a 100μm nylon filter to yield a single cell suspension.

Ex Vivo Stimulation

Wound cell isolates were plated in teflon wells and stimulated with LPS (100 ng/mL). After 1 hour, GolgiStop™(BD Biosciences; Cat. 51-2092KZ; 1:2,000 dilution) was added and cells were prepared for surface staining.

Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACs)

Wounds were digested as described above. Single cell suspensions were incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled anti-CD3, anti-CD19, and anti-Ly6G (Biolegend) followed by anti-flourescein isothiocyanate microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec; Cat. 130-042-401, 130-049-601). Flow through was incubated with anti-CD11b microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec; Cat. 130-049-601) to isolate non-neutrophil, non-T cell, non-B cell, CD11b+ cells.

Flow Cytometry/Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACs)

For surface staining, wound cell isolates were collected either directly from wounds or after ex vivo stimulation. Peripheral blood was collected and following red cell lysis and Ficoll separation, cells were processed for surface staining. Cells were stained with a Fixable LIVE/DEAD viability dye (Molecular Probes by Life Technologies; Ref. L34959; 1:1,000 dilution). FcR-receptors were then blocked with anti-CD16/32 (BioXCell, Cat. CUS-HB-197, 1:200 dilution) for 10 minutes. Monoclonal antibodies for surface staining included: Anti-CD3 (Biolegend, Cat. 100304, 1:400 dilution), Anti-CD19 (Biolegend, Cat. 115504, 1:400 dilution), Anti-Ter-119 (Biolegend, Cat. 116204, 1:400 dilution), Anti-NK1.1 (Cat. 108704, 1:400 dilution), Anti-Ly6G (Biolegend, Cat. 127604, 1:400 dilution), Anti-CD11b (Biolegend, Cat. 101230, 1:400 dilution), Anti-Ly6C (Biolegend, Cat. 128035, 1:400 dilution) and Anti-F4/80 (Biolegend, Cat. 123121, 1:400 dilution). Following surface staining, cells were washed twice, and biotinylated antibodies were labeled with streptavidin-fluorophore (Biolegend, Cat. 405208, 1:1,000 dilution). Next, cells were either washed and acquired for surface-only flow cytometry, or were fixed with 2% formaldehyde and then washed/permeablized with BD perm/wash buffer (BD Biosciences, Ref. 00-8333-56) for intracellular flow cytometry. After permeablization, intracellular stains included: anti-IL1β-Pro-PE Cy7 (eBioscience, Ref. 25-7114-82, 1:200 dilution) and anti-TNFα-APC (Biolegend, Cat. 506308, 1:200 dilution). Samples were acquired on a 3-Laser Novocyte Flow Cytometer (Acea Biosciences) or FACs sorted on a FACsAria III Flow Sorter. FACs sorting was performed with FACsDiva Software (BD Biosciences), analysis was performed using FlowJo software version 10.0 (Tree Star), and data was compiled using Prism software (GraphPad). All populations were routinely back-gated to verify gating and purity. CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages were sorted for RNA-sequencing and adoptive transfer experiments.

RNA-Sequencing

Two biological replicates from ND and HFD mice were surface stained and sorted by FACs into CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo populations. RNA isolation was performed using a miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen) with DNAse digestion. Due to low RNA yields, library construction was performed using the Clontech SMARTer Pico Kit (Mountain View, CA). Resulting reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic and mapped using HiSAT240, 41. Read counts were performed using the feature-counts option from the subRead package followed by the elimination of low reads, normalization and differential gene expression using edgeR42, 43. For comparison to in vitro macrophages, an M1[IFNγ] dataset from transcriptome data by Piccolo et al. and a M1[LPS,IFNγ] and M2[IL-4] dataset by Jha et al. were used44, 45. All reads were mapped to the mm10 genome. Differential expression was performed on mapped reads using the taqwise dispersion algorithm in edgeR43, 46.

Adoptive Transfer

Blood leukocytes from mT/mG mice were passed through a Ficoll gradient and the buffy coat was collected. The mononuclear cell suspension was washed in Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) buffer, labeled with anti-CD3-Biotin, anti-CD19-Biotin, anti-NK1.1-Biotin antibodies (Biolegend), and ultimately, anti-biotin micro-magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). The cells were then passed through a MACS sorting column for negative selection. Cells were then surface stained and FACS sorted (as described) to obtain a pure Ly6CHi population. Approximately 24 hours after wounding, ~106 tdtomato+ Ly6CHi blood monocytes were injected via tail vein into Control and DIO mice. Wounds and peripheral blood were then collected on day 4 post-injury for flow analysis.

MCP-1 Assay

Wound cells were analyzed for MCP-1 levels using DuoSt ELISA kit (R&D Systems; Cat. SMJE00) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA extraction was performed with Trizol using the manufacturer instructions. Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using iScript™(Biorad). qPCR was performed with 2X Taqman PCR mix using the 7500 Real-Time PCR system. Primers for MCP-1 were purchased from Applied Biosciences. Fold expression was calculated by normalizing to control 18s ribosomal RNA using (2ΔCt) analysis. All samples were assayed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software version 6.0 was used to analyze the data. Data is presented as the mean +/- the standard error of the mean(SEM). Data was first analyzed for normal distribution and then statistical significance between multiple groups was determined using one-way analysis of variance followed by Newman-Keuls post hoc test. For all other single group comparisons if data passed normality test, we used two-tailed Student's t-test. Otherwise data were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U-test. All data are representative of at least two independent experiments. A P-value of less than or equal to 0.05 was significant.

Results

CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages rapidly accumulate after skin injury and transition to CD11b+Ly6CLo macrophages

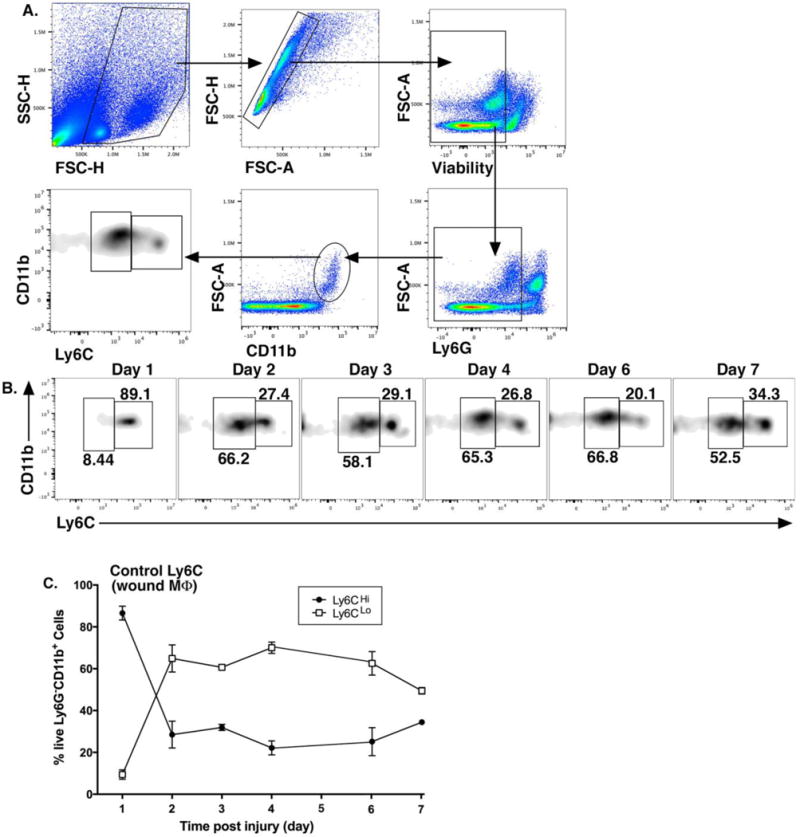

Monocyte/macrophages are highly plastic in their roles in acute inflammation, and hence, possess dichotomous roles in both tissue destruction and tissue repair following injury 23, 32. Given the opposing effector functions of distinct cell subsets, a high degree of regulation is necessary for proper repair of injured tissue19. Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests infiltrating monocyte/macrophages contribute significantly to inflammatory conditions, including diabetes, due to an imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory monocyte/macrophages 8, 10, 12, 23, 30. While this is widely accepted, the kinetics of myeloid subset influx in wound healing over time has remained elusive. Since the kinetics of recruited monocyte/macrophage subsets Ly6CHi(Gr1HiCCR2+CX3CR1Lo) and Ly6CLo(Gr1LoCCR2−CX3CR1Hi) following injury in normal wounds has not been well-defined, wounds from C57BL/6 mice were collected daily post-injury and processed for flow cytometry. Our outlined gating strategy removed doublets, non-viable cells, and neutrophils (Ly6G−), selecting CD11b+ cells. Proportions of CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo cells were determined as shown in the density plot (w. 1A). There is a clearly identifiable CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo population at each time point in the wounds, consistent with data from other organs (Fig. 1B) 23. The relative proportions of the CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo cells in wounds change over time. For the first 24–48 hours there is a four-fold predominance in CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages in the wounds (~80:20 at 24 hours), however, eventually the CD11b+Ly6CLo cohort dominates around 48-hours (Fig. 1C). In order to confirm our focus on infiltrating monocyte/macrophages and not resident macrophages (CD11b+/F4/80+), we examined resident tissue macrophages in our wound granulation tissue and found that they were a small percentage of cells that did not influence our CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in wounds (Supplemental Fig. I). In addition to the changes in myeloid cell subsets in wounds over time, these findings demonstrate the ability to track and compare two independent monocyte/macrophage populations in wounds.

Figure 1. Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages rapidly accumulate during the first 24–48 hours following injury and then transition to Ly6CLo[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells.

Wounds were created using a 4mm punch biopsy on the back of male C57BL/6 mice. Wounds were harvested daily for 7 days post-injury and analyzed by flow cytometry. (A) Gating strategy to select single, live, Ly6G−, CD11b+ cells and stratify by Ly6CHi vs. Ly6CLo. (B) Representative flow plots of Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells on post-injury days 1-7. (C) Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells plotted as a percentage of CD11b+ cells (n =32 mice; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments.) All data are expressed as the mean +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM).

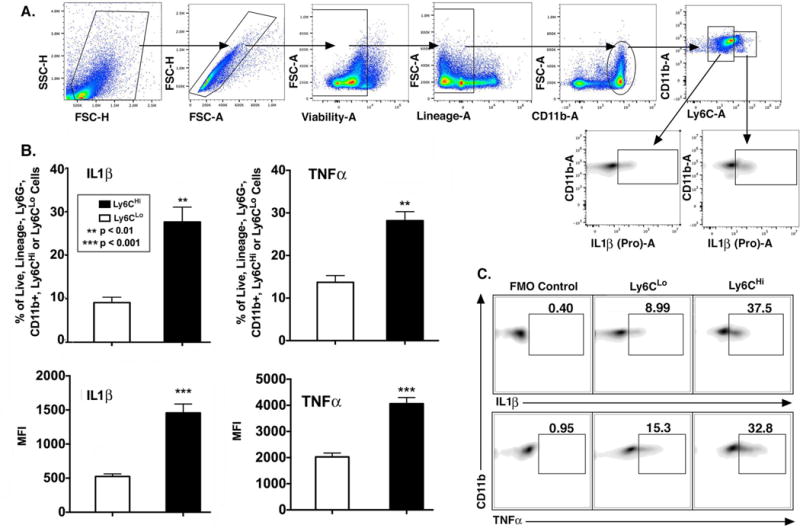

Wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages reveal distinct inflammatory profiles

It has been previously shown in other tissues that Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages display an inflammatory phenotype. To evaluate if CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages in wounds are pro-inflammatory with respect to their CD11b+Ly6CLo counterparts, wounds were collected on day 2 post-injury. Following ex vivo stimulation, wounds were analyzed by flow cytometry after gating out doublets, non-viable cells, lineage cells [CD3,CD19,NK1.1,Ter-119]−, and neutrophils [Ly6G]−. The resultant population was then selected for CD11b+ cells and then Ly6CHi or Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages (Fig. 2A). Selectively, percentages and MFI of TNFα and IL1β-producing cells were calculated from the Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo populations (Fig. 2B). An FMO control was used to verify accuracy of gate placement (Fig. 2C). Significantly more CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages were pro-inflammatory when compared to CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages. Specifically, CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages had 27.7% positive cells for IL1β and 28.5% positive cells for TNFα; compared to 9.1% and 13.7% in CD11b+Ly6CLo cells, respectively. Comparably, the MFI of IL1β and TNFα were 1457 and 4060 in CD11b+Ly6CHi vs. 524 and 2025 in CD11b+Ly6CLo cells, respectively. Based on this data, these two monocyte/macrophage subsets display different phenotypes in wounds with respect to inflammation. Interestingly, when we examined CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo wound cells for TGFβ, an ‘M2-like’ cytokine involved in tissue repair, we found that CD11b+Ly6CLo cells produced significantly more TGFβ compared to wound CD11b+Ly6CHi cells (Supplemental Fig. II). These findings suggest that Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo subsets play distinctly different roles in tissue repair and quantification of their proportions may be useful in pathologic settings for prognostication and to identify therapeutic targets.

Figure 2. Wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages display distinct inflammatory profiles.

Wounds from C57BL/6 mice were collected on post-injury day 2 for cell isolation, ex vivo stimulation, and intra-cellular staining for flow cytometry. (A) Gating strategy to select single, live, lineage− [CD3,CD19,NK1.1,Ter-119] −, Ly6G−, CD11b+, Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo cells. (B) Top panels: Percentage (%) of Ly6CHi vs. Ly6CLo cells staining positive for IL1β and TNFα. Bottom panels: MFI of IL1β and TNFα in the Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo gate (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 10 mice; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments.) (C) Representative density plots of Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo cells stratified for IL1β and TNFα with FMO control. All data are expressed as mean +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM).

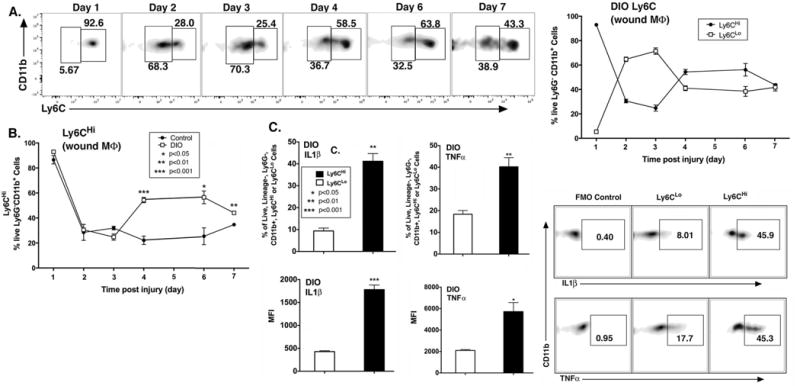

Diabetic wounds demonstrate a second, late influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages

Given the differences in inflammatory cytokine production between Ly6C monocyte/macrophage subsets in normal wounds, we hypothesized that excess CD11b+Ly6CHi cells and decreased CD11b+Ly6CLo cells could contribute to the pathologic inflammation seen in diabetes10, 19. To address this, a physiologic murine model of T2D (diet-induced obese [DIO];60% saturated fat diet) was used. The DIO model was used as opposed to other models of T2D due to its lack of alterations in the innate immune system 47-49. Similar to normal control mice (Fig. 1B/C), the DIO wounds demonstrated an early influx of CD11b+ Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages that transitioned to CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophage dominance around 48 hours. However, in the DIO wounds, there was a second influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages between days 3 and 4 post-injury that persisted until day 7 (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, when comparing percentages of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages post-injury between control and DIO mice, at day 4, CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages represented 22.2% in control mice and 54.3% in DIO mice (Fig. 3B). There were no changes in overall CD11b+ wound cell numbers or F4/80+ resident macrophages between the DIO and control groups, suggesting that the proportional shift in Ly6C populations drives inflammation in the tissue (Supplemental Figs. III, IV). Additionally, while there is an increase in the proportion of CD11b+ Ly6CHi cells in DIO wounds, there is a reciprocal decrease in the percentages of CD11b+ Ly6CLo cells in DIO wounds compared with controls (Supplemental Fig. V). The predominance of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages in DIO wounds at late time points is consistent with previously published data demonstrating increased inflammatory macrophages in diabetic wounds 8, 10, 12. To evaluate if the second influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages retain their pro-inflammatory phenotype in late DIO wounds, we performed intra-cellular flow cytometry for TNFα and IL1β. CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages were 41.2% and 40.2% positive for IL1β and TNFα, while CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages were 9.4% and 18.4% positive, respectively. In parallel, the MFI of IL1β and TNFα in the Ly6CHi gate was significantly increased compared to the Ly6CLo gate (Fig. 3C). In order to compare changes in wound Ly6C populations with changes in CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in peripheral blood, we analyzed blood CD11b+Ly6CHi cell proportions in injured and uninjured mice, as well as in control and DIO mice (Supplemental Fig. VI). Interestingly, similar to what was demonstrated by Swirski et al., we found that there is an increase in peripheral blood CD11b+Ly6CHi cells following injury.50 Further, when we looked at differences in peripheral blood CD11b+Ly6CHi cells between wounded control and DIO mice, there were significantly less CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in DIO peripheral blood at day 4 post injury. This suggests that these blood cells may be rapidly recruited to the site of injury in DIO mice and result in an inverse relationship in CD11b+Ly6CHi cell numbers in peripheral blood and wound tissue. Taken together, these findings suggest that the increased inflammatory phenotype seen in diabetic wounds is secondary to increased CD11b+Ly6CHi blood monocyte/macrophages and decreased CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages at late time points following injury.

Figure 3. Diabetic wounds demonstrate a second, late influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages.

C57BL/6 mice were fed high fat (HFD) chow (60%kCal) for 12–16 weeks to induce obesity and insulin resistance/glucose intolerance in the diet-induced obese model (DIO) of physiologic type 2 diabetes. Wounds were collected on post-injury days 1–7 for flow cytometry. (A) Representative density plots of DIO Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] and DIO Ly6CLo[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells on post-injury days 1-7. Gating strategy was identical to Figure 1. DIO Ly6CHi[Live, Ly6G−,CD11b+] and DIO Ly6CLo[Live, Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells plotted as a percentage of CD11b+ cells (n = 32 mice; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments.) (B) Direct comparison of control and DIO Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells over time following injury. (*P < 0.05,**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 4 mice/group/time point; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 2 experiments.) (C) DIO wounds were collected on post-injury day 2 for cell isolation, ex vivo stimulation, and intra-cellular staining for flow cytometry. Representative density plots of DIO Ly6CHi and Ly6CLo [Lin−, Ly6G−,CD11b+] cells as gated in Figure 2, stratified for IL1β and TNFα. Top panels: % of DIO CD11b+Ly6CHi vs. DIO CD11b+Ly6CLo cells staining positive for IL1β and TNFα. Bottom panels: MFI of IL1β and TNFα in the DIO CD11b+Ly6CHi and DIO CD11b+Ly6CLo gate (*P <0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; n = 5 mice/group; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 2 experiments.)

Diabetic wound CD11b+Ly6CHi cells display an impaired transition to the CD11b+Ly6CLo phenotype

CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages have been shown in other tissues to mature to a less inflammatory CD11b+Ly6CLo phenotype 31, 51, however in wound tissue and particularly diabetic wounds, this has not been evaluated. Hence, another potential mechanism of CD11b+Ly6CHi predominance in DIO wounds may be a failure of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages to differentiate to the less inflammatory CD11b+Ly6CLo cells. To confirm that CD11b+Ly6CHi cells are recruited to the wound from peripheral blood and to evaluate their progression in wounds from a CD11b+Ly6CHi to a CD11b+Ly6CLo phenotype, we performed a series of adoptive transfer experiments. Specifically, control and DIO mice were wounded at time zero and ~ 24 hours later underwent adoptive transfer with 106 CD11b+Ly6CHi blood monocytes harvested from mT/mG mice (Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J). Wounds were harvested on day 4 (gating strategy identical to Fig. 2A) and flow analysis was performed on the samples by first selecting tdTomato+[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] cells and then stratifying by Ly6C to identify the adoptively transferred CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages (Fig. 4A). Adoptively transferred tdTomato+ CD11b+Ly6CHi cells were detectable in the wounds of both control and DIO mice after 3 days. Further, as previously described 31, 51, adoptively transferred CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages make a transition to a CD11b+Ly6CLo phenotype, however, this transition appears to be impaired in DIO wounds. Importantly, we observed an approximate 70:30 proportion of Ly6CHi to Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages in DIO mice compared to an approximate 50:50 proportion in control mice (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these findings suggest that the pro-inflammatory CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophage predominance in DIO wounds is related to both an increased recruitment and impaired differentiation of CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in a diabetic setting.

Figure 4. Diabetic wound CD11b+Ly6CHi cells demonstrate delayed transition to a CD11b+Ly6CLo phenotype.

(A) Schematic of adoptive transfer experiment in which 106 tdTomato-expressing Ly6CHi[Lin−, Ly6G−, CD11b+] peripheral blood cells were injected via tail vein into control and DIO mice 24 hours after wounding. Control and DIO wounds were harvested on day 4 (3 days post-adoptive transfer) and single cell suspensions were processed for flow cytometry. Representative density plots of adoptively transferred control and DIO wounds gated for tdTomato+[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] cells and then stratifying by Ly6C designation. (B) Control and DIO wounds were harvested on day 4 (3 days post-adoptive transfer) and single cell suspensions were processed for flow cytometry. Relative percentages of adoptively transferred Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+tdTomato+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+tdTomato+] monocyte/macrophages (*P < 0.05; n = 6 wounds per group, repeated 1X). All data are expressed as the mean +/− the standard error.

Diabetic wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo cells reveal distinct transcriptome profiles

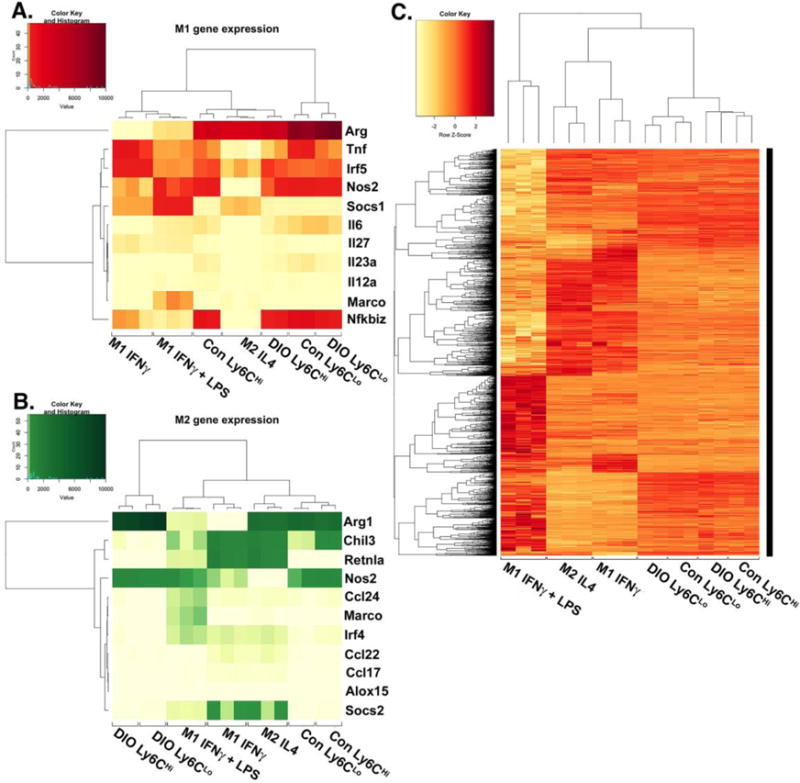

Literature examining the hyper-inflammatory state of diabetic wounds has drawn loose comparisons between in vivo wound monocyte/macrophages and classical or alternative in vitro macrophages 5, 8-10. While this can be helpful for descriptive purposes, it is hindered by inconsistencies in nomenclature and a degree of overlap in in vivo wound monocyte/macrophage subsets that do not fit discrete in vitro definitions 7, 21. Further, to our knowledge, the comparison of diabetic and control wound monocyte/macrophages with in vitro M1[LPS/IFNγ], M1[IFNγ] or M2[IL-4] macrophages has not been examined using whole transcriptome profiling. Since the gene expression profiles of in vivo Ly6CHi[Lin-Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophage populations in wounds are unknown due to the lack of transcriptome data, we first sought to evaluate by RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq), if in vivo infiltrating Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages from DIO and normal wounds correlate with traditional definitions of in vitro M1[LPS,IFNγ] or M2[IL-4] macrophages 7. Single cell suspensions from control and DIO wounds (2 biologic replicates/group; 4 mice/replicate) were washed, surface stained and FACS sorted into Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] populations. RNA samples were then run by the University of Michigan DNA Sequencing Core. Given that there is dissention in the literature regarding the definitions of in vitro macrophages, we utilized the International Congress of Immunology Guidelines (2013) to select gene transcripts for comparison with our wound cells7. Specifically, we generated a heatmap looking at our wound transcriptome data and compared that directly with publically available M1[IFNγ], M1[LPS,IFNγ] and M2[IL-4] transcriptome data44, 45. We first focused on M1 consensus genes: Arg1, Socs1, Nos2, Marco, Il27, Il23a, Il12a, Il6, Nfkbiz, Tnf, and Irf5 (Fig. 5A). Focusing on this specific set of important M1genes, it is clear that there is a resemblance between in vivo CD11b+Ly6CHi wound monocyte/macrophages and M1[LPS/IFNγ] in vitro macrophages. Further, when we focused on M2 consensus genes: Arg1, Chil3, Retnla, Nos2, Ccl24, Marco, Irf4, Ccl22, Ccl17, Alox15 and Socs2 we found that the genes shared by both subsets, including Arg1 and Nos2, were most strongly expressed by in vivo Ly6C wound monocyte/macrophages (Fig. 5B). Many of the genes that were distinct to the M2 subset were not highly expressed by any in vivo subset. Since Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages represent more of a hybrid picture between in vitro “M1” and “M2” macrophages, it is possible that the use of traditional in vitro macrophage characterization for this cell population in wound healing is not practical, as has been previously suggested21. These findings are highly relevant as they will allow for more accurate immunophenotyping of wound monocyte/macrophages and identify new avenues for therapy. To test the similarity of in vivo monocyte subsets isolated from wounds to traditional in vitro macrophages, we compared the entire transcriptome from each data set (Fig 5C). Figure 5C shows the Pearson correlation for all differentially expressed genes. These data confirm the analysis performed in Figure 5A/B and further demonstrate that the in vivo subsets display a distinct profile in comparison to in vitro macrophages.

Figure 5. Diabetic wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages display distinct transcriptome profiles.

Wounds from normal and high fat diet (HFD)-fed, diet-induced obese (DIO) C57BL/6 mice were collected on post-injury day 3 for cell isolation, surface staining, and FACs to isolate Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages for RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq). RNA samples were processed by the NIH-funded, University of Michigan DNA sequencing core. Reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic and mapped using HiSAT2. Read counts were performed using the featureCounts option from the subRead package followed by the elimination of low reads and normalization using edgeR. For comparison to in vitro generated macrophages, M1[IFNγ], M1[LPS,IFNγ] and M2[IL-4] datasets were used from publically available transcriptome data generated by Piccolo et al44. (A) A heatmap of normalized reads obtained from edgeR for an internationally recognized panel of consensus genes for in vitro generated M1 macrophages. Wound Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages were compared to the M1[IFNγ], M1[LPS,IFNγ], and M2[IL-4] transcriptomes. (B) A heatmap of normalized reads obtained from edgeR for an internationally recognized panel of consensus genes for in vitro generated M2 macrophages. Wound Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages were compared to the M1[IFNγ], M1[LPS,IFNγ], and M2[IL-4] transcriptome. (C) Clustered Pearson correlation of the entire transcriptome of in vivo DIO and control Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages and in vitro M1[IFNγ], M1[LPS,IFNγ], and M2[IL-4] macrophages (n = 8 mice per group; 4 wounds per mouse were pooled to obtain a single biological replicate given low RNA volumes. Two biological replicates per group were examined.)

Since diabetic wounds demonstrate increased recruitment of infiltrating Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] pro-inflammatory monocyte/macrophages, we examined whether diabetic CD11b+Ly6CHi wound cells differ in transcriptome from control wound CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages. Using edgeR analysis and hierarchical clustering, we found a significant discord between CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages from control and diabetic wounds. Many of these genes are important in inflammation and collagen formation and are thus, important for wound healing (Supplemental Table II). Taken together, these findings suggest that increased inflammation in diabetic wounds is the result of both an additional late influx of pro-inflammatory CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages as well as altered phenotypes of these monocyte/macrophages in the diabetic environment.

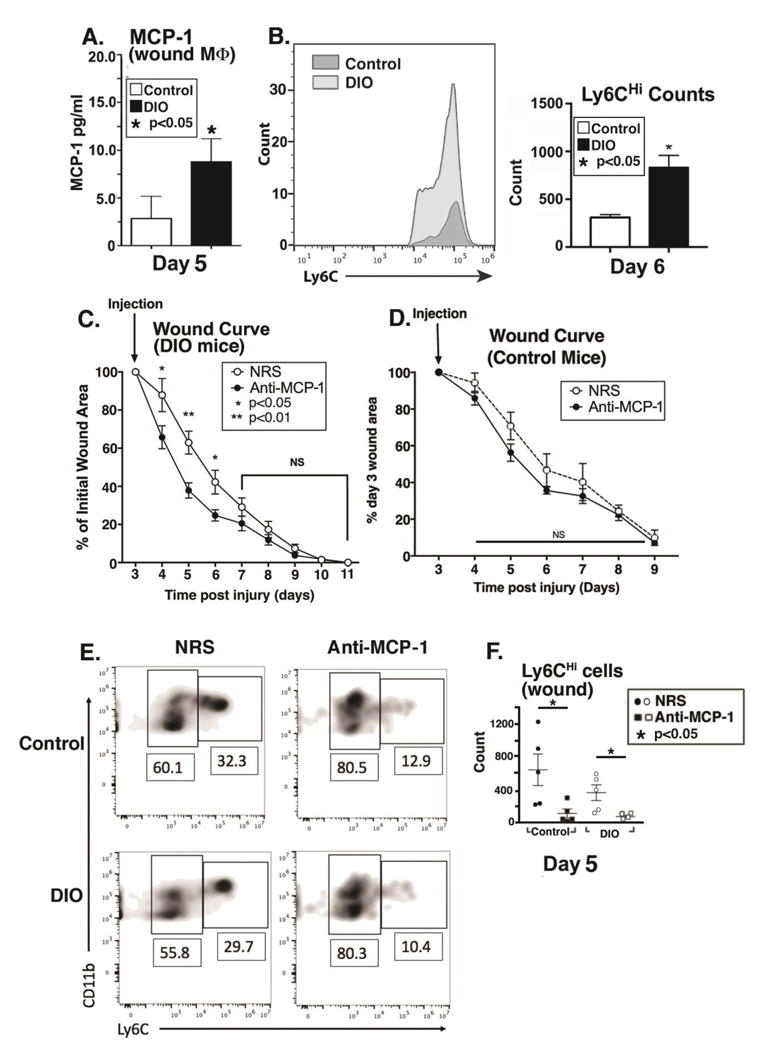

Timed treatment of diabetic mice with Anti-MCP-1 antibody post-injury restores normal healing

To examine the mechanism responsible for increased CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages in diabetic wounds, we first identified chemotactic factors that may drive increased recruitment of monocytes from peripheral blood. MCP-1(CCL2) is the ligand to the monocyte chemokine receptor CCR2 and is necessary for recruitment of blood monocytes to inflamed tissues 21, 34. Hence, we measured levels of MCP-1 in control and DIO wound cells at a time point during the second CD11b+Ly6CHi influx in diabetic wounds. When we examined CD3+ lymphocytes, CD19+ B cells, Ly6G+ neutrophils, CD4+ T cells, CD11b− [CD3,CD19,NK1.1,Ly6G]− cells, and CD11b+[CD3,CD19,NK1.1,Ly6G]− myeloid cells from wounds we found that MCP-1 levels were significantly increased in DIO wound CD11b+[CD3,CD19,NK1.1,Ly6G]− cells (wound macrophages as previously defined by our group and others) compared to controls on day 5 following injury (Fig. 6A, Supplemental Fig. VII)10, 12, 52, 53. This increase in DIO wound MCP-1 at day 5 is accompanied by increased CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophage counts in DIO wounds at day 6 (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Timed treatment of diabetic mice with anti-MCP-1 antibody post-injury restores normal healing.

(A) The ligand for the blood monocyte CCR2 receptor, MCP-1, was examined in wound macrophages isolated by magnetic cell sorting CD11b+[CD3−CD19−NK1.1−Ly6G−] from DIO and control mice on day 5. Protein levels of MCP-1 as determined by ELISA in control and DIO wound cells on day 5 post-injury. (*P < 0.05; n= 5 mice/group; data is representative of 2 independent experiments). (B) Control and DIO wounds were harvested on day 6 and single cell suspensions were processed for flow cytometry. Ly6CHi[Live,Ly6G−,CD11b+] monocyte/macrophage counts (as gated in Figure 1) are shown. (*P < 0.05; n= 5 mice/group; repeated 1X). (C) DIO mice were wounded with a 4 mm punch biopsy and wound healing was monitored daily using an 8mp iPad camera, internal scale, and NIH ImageJ software. At day 3 post-injury, mice underwent intra-peritoneal injection with either normal rabbit serum (NRS) or purified rabbit anti-mouse MCP-1 antibody (anti-MCP-1) and wound healing was monitored until wound closure. Wound curves were generated as percent of initial wound area. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; n = 10 wounds per group). (D) Control mice were wounded with a 4 mm punch biopsy and wound healing was monitored daily using an 8mp iPad camera, internal scale, and NIH ImageJ software. At day 3 post-injury, mice underwent intra-peritoneal injection with either normal rabbit serum (NRS) or purified rabbit anti-mouse MCP-1 antibody (anti-MCP-1) and wound healing was monitored until wound closure. Wound curves were generated as percent of initial wound area. (n = 10 wounds per group). (E/F) DIO mice were wounded with a 4 mm punch biopsy and on day 3 post-injury, mice underwent intra-peritoneal injection with either normal rabbit serum (NRS) or purified rabbit anti-mouse MCP-1 antibody (anti-MCP-1). Wounds were harvested on day 5 and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gating was identical to that shown in Figure 2. DIO Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and DIO Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] wound cells from NRS and anti-MCP-1 injected. (*P < 0.05; n =25 mice; tissues of 2 wounds per mouse were pooled for a single biological replicate. Data is representative of 2 independent experiments.) All data are expressed as mean +/− the standard error of the mean (SEM).

Prior work in murine models of diabetes has demonstrated impaired wound healing secondary to increased inflammation8, 10, 12. Given that we found a potential mechanism for increased inflammation in diabetic wounds through the excessive recruitment and retention of CD11b+Ly6CHi inflammatory monocyte/macrophages, we hypothesized that selective, timed depletion of MCP-1 could improve wound healing by blocking the second influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi inflammatory monocytes/macrophages. DIO and control mice were wounded and on post-injury day 3 (24 hours prior to the observed second wave of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages), injected with either normal rabbit serum (NRS) or purified rabbit anti-mouse MCP-1 antibody (anti-MCP-1) and wound healing was monitored. Anti-MCP-1 injected DIO mice demonstrated significantly improved wound healing compared to NRS-injected controls (Fig 6C). As expected, in control mice, anti-MCP-1 injection did not significantly alter wound healing, although there was a trend towards impaired healing in the anti-MCP-1 injected mice (Fig 6D). This is similar to other studies demonstrating that impairing monocyte recruitment in normal wound healing is detrimental to healing21. Further, when wounds were harvested two days following anti-MCP-1 injection, there was a clear reduction in the CD11b+Ly6CHi cells, suggesting that the improved wound healing seen in the DIO mice following anti-MCP-1 injection correlates with reduced CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte/macrophages (Fig. 6E/F). Additionally, when we examined the blood, there was a trend towards decreased CD11b+Ly6CHi cells and increased CD11b+Ly6CLo cells in both the normal and DIO blood following anti-MCP-1 injection (Supplemental Fig. VIII). These findings suggest that careful and time-dependent antibody-mediated control of monocyte/macrophage influx following injury may represent a novel therapeutic target for impaired diabetic wound healing.

Discussion

Infiltrating peripheral blood monocyte/macrophages are necessary for the maintenance of tissue homeostasis post-injury 11, 15. Monocyte/macrophages are highly plastic in their roles in acute inflammation, and hence, possess dichotomous roles in both tissue destruction and tissue repair following injury 23, 32. Given the opposing effector functions of distinct subsets, a high degree of regulation of these cells is necessary for proper repair of injured tissue19. Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence that suggests infiltrating monocyte/macrophages contribute significantly to inflammatory conditions, including diabetes, due to an imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cells 8, 10, 12, 23, 30. While this is widely accepted, the kinetics of myeloid cell subset influx in wound healing over time has remained elusive. Further, the definitions of these cell populations remain elusive, with many previous in vivo cell characterizations based on the inclusion of “resident macrophages” (CD11b+/F4/80+) 22, 26, 34. These resident macrophages arise from a separate non-hematopoietic cell lineage, are present at birth and self-renew in the tissues, making them fundamentally distinct from the blood-derived infiltrating monocyte/macrophages that are recruited to tissues following injury 27, 31. Thus, there is little existing literature that examines the phenotype and role of these infiltrating monocyte/macrophages following injury. Hence, we chose a model of wound healing in which we would collect granulation tissue (arguably devoid of resident macrophages; Supplemental Figure I) and our definition Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] and Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] as infiltrating monocyte/macrophages based on previous work that classified these cells with a similar definition 23, 35, 52, 54, 55.

Herein, we have described the influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages in wound healing in physiologic and diabetic conditions, and have found mechanisms for increased inflammation in diabetic wound healing secondary to an increased influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi cells and a delay in their maturation to CD11b+Ly6CLo cells. Interestingly, we found an increased number of circulating CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes in control wounded mice and when comparing control and DIO wounded mice, there were less circulating CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in DIO mice while there were more CD11b+Ly6CHi cells in DIO wounds - suggesting a yin-yang phenomenon in monocyte recruitment in diabetes. While this could represent a poor mobilization of splenic and bone marrow derived monocytes in diabetic mice, it has been demonstrated previously that in the setting of intact CCR2-MCP1 signaling, there is robust mobilization of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes from bone marrow and spleen following injury50, 56. Additional mechanisms of increased inflammation in diabetic wounds were demonstrated herein using RNA-based transcriptome profiling, where we found that the transcriptome of diabetic wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo monocyte/macrophages differs from control cells with respect to pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic gene expression. Importantly, these transcriptome-based studies identify an accurate way to immunophenotype monocyte/macrophages in the wound and may provide a benchmark for response to therapy. Additionally, we have found that a selective, timed injection of anti-MCP-1 antibody resulted in improved wound healing in diabetic mice; suggesting at least a partial amelioration of the impaired wound healing phenotype.

Previous studies have drawn loose comparisons between in vivo wound monocyte/macrophages and classical or alternative in vitro macrophages 5, 8-10. Since it is not clear that in vivo wound monocyte/macrophage subsets fit discrete in vitro definitions 7, 21, we performed a full transcriptome analysis of both diabetic and control wound monocyte/macrophages. Using RNA-seq we found that the transcriptome of Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages extracted from normal wounds do resemble in vitro M1[LPS,IFNγ] macrophages. Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] monocyte/macrophages, however, do not resemble M2 in vitro macrophages. Taken together with our RNA-seq data, this suggests that Ly6C is important in immunophenotyping wound monocyte/macrophages. These findings are highly relevant as they will allow for accurate immunophenotyping and promote caution in drawing comparisons between in vivo wound monocyte/macrophages and traditional in vitro macrophages.

While this manuscript addresses important issues with regards to the fundamental biology of blood monocyte influx and its relation to wound phenotypes, there are some limitations. First, wound monocyte/macrophages are inextricably related to wound dendritic cells and they are tedious to define with traditional flow cytometry 22. Thus, it is conceivable that some of our findings are related to wound dendritic cells, however, given the homogenous character of our RNA-seq data between biological replicates, this is unlikely to be relevant. Next, while our RNA-seq comparison of Ly6CHi[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] cells with M1[LPS,IFNγ] data revealed a close resemblance, there are still many differentially expressed genes, which cautions that a direct comparison is still somewhat unreliable except in the confines of comparing consensus genes. Further, while our Ly6CLo[Lin−Ly6G−CD11b+] RNA-seq data did not show resemblance to the M2[IL-4] transcriptome, our findings of increased TGFβ in CD11b+Ly6CLo cells is consistent with previously published reports by Olingy et al. which found that CD11b+Ly6CLo cells are predisposed to form CD206+ repair macrophages in wound tissues 57. Finally, with regard to our translational finding that blocking the MCP-1/CCR2 axis improves late wound healing in diabetes, previous work by Willenborg et al. suggests that this leukocyte recruitment mechanism is essential for normal wound healing 21. We agree with this and feel that our findings complement this study, as we found that the timing of MCP-1/CCR2 blockade is important, since initial inflammation is critical for proper wound healing.

Our findings herein are both novel and timely, as recent literature has highlighted the importance of blood monocyte/macrophage heterogeneity in health and disease 35, 58. Additional questions remain as to whether blood monocyte chemotaxis modulation or control of monocyte/macrophage phenotype transition will be effective in treating inflammatory conditions. With new research focused on monocyte/macrophage heterogeneity in wounds, it is foreseeable that an improved understanding of chronic inflammatory conditions will lead to new, desperately needed therapeutics.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Blood CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes profoundly influence both normal and pathologic wound healing.

In normal wounds, CD11b+Ly6CHi cells are the predominant subset early post-injury, followed by a transition to a CD11b+Ly6CLo -dominant phenotype; however, in diabetic wounds there was a second influx of recruited CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes, that corresponded with increased tissue MCP-1.

Adoptive transfer of fluorescent tdTomato-labeled CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes demonstrated that diabetic CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes have a delayed phenotypic switch to CD11b+Ly6CLo cells.

Based on transcriptome profiling of flow-sorted wound CD11b+Ly6CHi and CD11b+Ly6CLo cells, we found that CD11b+Ly6CHi monocyte-macrophages from diabetic wounds differ significantly in their expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic genes.

Timed administration of anti-MCP-1 antibody prevents the second influx of CD11b+Ly6CHi monocytes and reverses impaired diabetic wound healing.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Robin G. Kunkel, Research Associate in the Pathology Department, University of Michigan, for her artistic work.

Funding Source: This work was supported by NIH DK-102357, NIH-T32 HL076123 and the Wolfe Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Reiber GE, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ, del Aguila M, Smith DG, Lavery LA, Boulton AJ. Causal pathways for incident lower-extremity ulcers in patients with diabetes from two settings. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:157–62. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faglia E, Favales F, Morabito A. New ulceration, new major amputation, and survival rates in diabetic subjects hospitalized for foot ulceration from 1990 to 1993: a 6.5-year follow-up. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:78–83. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dinh T, Tecilazich F, Kafanas A, Doupis J, Gnardellis C, Leal E, Tellechea A, Pradhan L, Lyons TE, Giurini JM, Veves A. Mechanisms involved in the development and healing of diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes. 2012;61:2937–47. doi: 10.2337/db12-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannel WB. Risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes in different arterial territories. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1994;1:333–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boniakowski AE, Kimball AS, Jacobs BN, Kunkel SL, Gallagher KA. Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in Normal and Diabetic Wound Healing. J Immunol. 2017;199:17–24. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, Fisher EA, Gilroy DW, Goerdt S, Gordon S, Hamilton JA, Ivashkiv LB, Lawrence T, Locati M, Mantovani A, Martinez FO, Mege JL, Mosser DM, Natoli G, Saeij JP, Schultze JL, Shirey KA, Sica A, Suttles J, Udalova I, van Ginderachter JA, Vogel SN, Wynn TA. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mirza RE, Fang MM, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Blocking interleukin-1beta induces a healing-associated wound macrophage phenotype and improves healing in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:2579–87. doi: 10.2337/db12-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, Peter H, Hainzl A, Schatz S, Qi Y, Schlecht A, Weiss JM, Wlaschek M, Sunderkotter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:985–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI44490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher KA, Joshi A, Carson WF, Schaller M, Allen R, Mukerjee S, Kittan N, Feldman EL, Henke PK, Hogaboam C, Burant CF, Kunkel SL. Epigenetic changes in bone marrow progenitor cells influence the inflammatory phenotype and alter wound healing in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:1420–30. doi: 10.2337/db14-0872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A, Biswas SK, Galdiero MR, Sica A, Locati M. Macrophage plasticity and polarization in tissue repair and remodelling. J Pathol. 2013;229:176–85. doi: 10.1002/path.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimball AS, Joshi AD, Boniakowski AE, Schaller M, Chung J, Allen R, Bermick J, Carson WFt, Henke PK, Maillard I, Kunkel SL, Gallagher KA. Notch Regulates Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in Diabetic Wound Healing. Front Immunol. 2017;8:635. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Italiani P, Boraschi D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in Tissue Repair, Regeneration, and Fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44:450–62. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medzhitov R. Origin and physiological roles of inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:428–35. doi: 10.1038/nature07201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toulon A, Breton L, Taylor KR, Tenenhaus M, Bhavsar D, Lanigan C, Rudolph R, Jameson J, Havran WL. A role for human skin-resident T cells in wound healing. J Exp Med. 2009;206:743–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivollier A, He J, Kole A, Valatas V, Kelsall BL. Inflammation switches the differentiation program of Ly6Chi monocytes from antiinflammatory macrophages to inflammatory dendritic cells in the colon. J Exp Med. 2012;209:139–55. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–52. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mirza R, Koh TJ. Dysregulation of monocyte/macrophage phenotype in wounds of diabetic mice. Cytokine. 2011;56:256–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna S, Biswas S, Shang Y, Collard E, Azad A, Kauh C, Bhasker V, Gordillo GM, Sen CK, Roy S. Macrophage dysfunction impairs resolution of inflammation in the wounds of diabetic mice. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Willenborg S, Lucas T, van Loo G, Knipper JA, Krieg T, Haase I, Brachvogel B, Hammerschmidt M, Nagy A, Ferrara N, Pasparakis M, Eming SA. CCR2 recruits an inflammatory macrophage subpopulation critical for angiogenesis in tissue repair. Blood. 2012;120:613–25. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-403386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Auffray C, Sieweke MH, Geissmann F. Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:669–92. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahrendorf M, Swirski FK, Aikawa E, Stangenberg L, Wurdinger T, Figueiredo JL, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. The healing myocardium sequentially mobilizes two monocyte subsets with divergent and complementary functions. J Exp Med. 2007;204:3037–47. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Furth R, Cohn ZA. The origin and kinetics of mononuclear phagocytes. J Exp Med. 1968;128:415–35. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor PR, Gordon S. Monocyte heterogeneity and innate immunity. Immunity. 2003;19:2–4. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00178-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, Prinz M, Wu B, Jacobsen SE, Pollard JW, Frampton J, Liu KJ, Geissmann F. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serbina NV, Salazar-Mather TP, Biron CA, Kuziel WA, Pamer EG. TNF/iNOS-producing dendritic cells mediate innate immune defense against bacterial infection. Immunity. 2003;19:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00171-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zigmond E, Varol C, Farache J, Elmaliah E, Satpathy AT, Friedlander G, Mack M, Shpigel N, Boneca IG, Murphy KM, Shakhar G, Halpern Z, Jung S. Ly6C hi monocytes in the inflamed colon give rise to proinflammatory effector cells and migratory antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 2012;37:1076–90. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yona S, Kim KW, Wolf Y, Mildner A, Varol D, Breker M, Strauss-Ayali D, Viukov S, Guilliams M, Misharin A, Hume DA, Perlman H, Malissen B, Zelzer E, Jung S. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dal-Secco D, Wang J, Zeng Z, Kolaczkowska E, Wong CH, Petri B, Ransohoff RM, Charo IF, Jenne CN, Kubes P. A dynamic spectrum of monocytes arising from the in situ reprogramming of CCR2+ monocytes at a site of sterile injury. J Exp Med. 2015;212:447–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.20141539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferris ST, Zakharov PN, Wan X, Calderon B, Artyomov MN, Unanue ER, Carrero JA. The islet-resident macrophage is in an inflammatory state and senses microbial products in blood. J Exp Med. 2017 doi: 10.1084/jem.20170074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ, Swirski FK. Monocytes: protagonists of infarct inflammation and repair after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2010;121:2437–45. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.916346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauvau G, Chorro L, Spaulding E, Soudja SM. Inflammatory monocyte effector mechanisms. Cell Immunol. 2014;291:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong KL, Tai JJ, Wong WC, Han H, Sem X, Yeap WH, Kourilsky P, Wong SC. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2011;118:e16–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surwit RS, Kuhn CM, Cochrane C, McCubbin JA, Feinglos MN. Diet-induced type II diabetes in C57BL/6J mice. Diabetes. 1988;37:1163–7. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.9.1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:923–30. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piccolo V, Curina A, Genua M, Ghisletti S, Simonatto M, Sabo A, Amati B, Ostuni R, Natoli G. Opposing macrophage polarization programs show extensive epigenomic and transcriptional cross-talk. Nat Immunol. 2017;18:530–540. doi: 10.1038/ni.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A, Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Chmielewski K, Stewart KM, Ashall J, Everts B, Pearce EJ, Driggers EM, Artyomov MN. Network integration of parallel metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 2015;42:419–30. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Differential expression analysis of multifactor RNA-Seq experiments with respect to biological variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–97. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dixit VD, Schaffer EM, Pyle RS, Collins GD, Sakthivel SK, Palaniappan R, Lillard JW, Jr, Taub DD. Ghrelin inhibits leptin- and activation-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression by human monocytes and T cells. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:57–66. doi: 10.1172/JCI21134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam QL, Lu L. Role of leptin in immunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chin CY, Monack DM, Nathan S. Delayed activation of host innate immune pathways in streptozotocin-induced diabetic hosts leads to more severe disease during infection with Burkholderia pseudomallei. Immunology. 2012;135:312–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M, Etzrodt M, Wildgruber M, Cortez-Retamozo V, Panizzi P, Figueiredo JL, Kohler RH, Chudnovskiy A, Waterman P, Aikawa E, Mempel TR, Libby P, Weissleder R, Pittet MJ. Identification of splenic reservoir monocytes and their deployment to inflammatory sites. Science. 2009;325:612–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1175202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Varol C, Vallon-Eberhard A, Elinav E, Aychek T, Shapira Y, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Hardt WD, Shakhar G, Jung S. Intestinal lamina propria dendritic cell subsets have different origin and functions. Immunity. 2009;31:502–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimball AS, Joshi A, Carson WFt, Boniakowski AE, Schaller M, Allen R, Bermick J, Davis FM, Henke PK, Burant CF, Kunkel SL, Gallagher KA. The Histone Methyltransferase MLL1 Directs Macrophage-Mediated Inflammation in Wound Healing and Is Altered in a Murine Model of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2017;66:2459–2471. doi: 10.2337/db17-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mirza RE, Fang MM, Weinheimer-Haus EM, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Sustained inflammasome activity in macrophages impairs wound healing in type 2 diabetic humans and mice. Diabetes. 2014;63:1103–14. doi: 10.2337/db13-0927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dunay IR, Damatta RA, Fux B, Presti R, Greco S, Colonna M, Sibley LD. Gr1(+) inflammatory monocytes are required for mucosal resistance to the pathogen Toxoplasma gondii. Immunity. 2008;29:306–17. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rose S, Misharin A, Perlman H. A novel Ly6C/Ly6G-based strategy to analyze the mouse splenic myeloid compartment. Cytometry A. 2012;81:343–50. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:902–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olingy CE, San Emeterio CL, Ogle ME, Krieger JR, Bruce AC, Pfau DD, Jordan BT, Peirce SM, Botchwey EA. Non-classical monocytes are biased progenitors of wound healing macrophages during soft tissue injury. Sci Rep. 2017;7:447. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cipolletta C, Ryan KE, Hanna EV, Trimble ER. Activation of peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes occurs in diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:2779–86. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.