Highlights

-

•

Breastfeeding significantly affects IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters.

-

•

The distribution of ADC0 values becomes more heterogeneous after breastfeeding.

-

•

Care needs to be taken in interpreting DWI data in lactating breasts.

Abbreviations: PABC, pregnancy-associated breast cancer; NCCN, national comprehensive cancer network; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; IVIM, intravoxel incoherent motion; T2WI, T2-weighted images; T1WI, T1-weighted images; ROI, regions of interest; K, kurtosis; MD, mean diffusion; DCE-MRI, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI

Keywords: Diffusion-weighted imaging, Intravoxel incoherent motion, Kurtosis, Lactation, Breast

Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the effect of breastfeeding on IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion MRI in the breast.

Materials and methods

An IRB approved prospective study enrolled seventeen volunteers (12 in lactation and 5 with post-weaning, range 31–43 years; mean 35.4 years). IVIM (fIVIM and D*) and non-Gaussian diffusion (ADC0 and K) parameters using 16 b values, plus synthetic apparent diffusion coefficients (sADCs) from 2 key b values (b = 200 and 1500 s/mm2) were calculated using regions of interest. ADC0 maps of the whole breast were generated and their contrast patterns were evaluated by two independent readers using retroareolar and segmental semi-quantitative scores. To compare the diffusion and IVIM parameters, Wilcoxon signed rank tests were used between pre- and post-breastfeeding and Mann-Whitney tests were used between post-weaning and pre- or post-breastfeeding.

Results

ADC0 and sADC values significantly decreased post-breastfeeding (1.90 vs. 1.72 × 10−3 mm2/s, P < 0.001 and 1.39 vs. 1.25 × 10−3 mm2/s, P < 0.001) while K values significantly increased (0.33 vs. 0.44, P < 0.05). fIVIM values significantly increased after breastfeeding (1.97 vs. 2.97%, P < 0.01). No significant difference was found in D* values. There was significant heterogeneity in ADC0 maps post-breastfeeding, both in retroareolar and segmental scores (P < 0.0001 and =0.0001).

Conclusion

IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters significantly changed between pre- and post-breastfeeding status, and care needs to be taken in interpreting diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) data in lactating breasts.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers occurring in pregnant and lactating women. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) usually presents at an advanced stage and has a poor prognosis [1]. The incidence of PABC may be increasing because of the increase in mean childbearing age in developed countries [2]. When this diagnosis is made in pregnancy, it can cause great psychosocial stress in these women [3]. The use of gadolinium contrast agents is standard for assessing breast cancer, however, small amounts of contrast agents may be excreted in breast milk [4]. Concerns have arisen based on recent findings of gadolinium deposits in the brain [5]. An increased risk of skin disease, stillbirth, or neonatal death in infants exposed to gadolinium contrast at any time during pregnancy has been documented [6]. Besides contrast-enhanced breast MRI during lactation is challenging due to increased enhancement in normal breast parenchyma that can mimic breast lesions [7].

The number of women undergoing breast MRI screening is expected to increase, as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) clinical practice guidelines recommend BRCA carriers (who have a high risk of developing breast cancer at a younger age) or women with a strong family history of breast cancer undergo an annual MRI exam or mammogram screening beginning at age 25 [8]. Breast awareness and clinical breast examinations every 6 months are recommended for these women; however, no clear evidence exists regarding mammography or breast MRI as a proper screening modality during lactation [9].

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), which requires no contrast agents, quantifies the Brownian motion of water molecules in vivo. Many studies have shown the utility of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) as a marker to distinguish between malignant and benign breast lesions [10]. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), which can extract perfusion-related information from DWI and non-Gaussian DWI, has further been applied to the detection and characterization of malignant and benign breast lesions [11,12] and their correlation with prognostic factors [13,14]. Synthetic ADC has been also introduced to encompass both Gaussian and non-Gaussian diffusion effects within clinically acceptable time [14,15]. The composition of milk produced depends on the overall duration of lactation; however, little is known about the effects of lactation and the changes after breastfeeding on diffusion biomarkers [[16], [17], [18]] and there are no data on the optimal timing to have a MRI scan of lactating breasts to date. Our aim was to investigate the changes in IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters in lactating breasts pre- and post-breastfeeding, and to define the most suitable time for performing breast diffusion MRI in lactating women.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants’ characteristics

This prospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all the healthy volunteers. Inclusion criteria were lactating and post-weaning women. Exclusion criteria were women with previous breast surgery, known breast tumors, or contraindications to MRI. Thus, twelve lactating women and 5 women 2–10 months post-weaning (31–43 years; mean 35.4 years) were enrolled in the study between December 2015 and March 2017.

Twelve lactating women were scanned twice, before and after breastfeeding. They suckled the babies at both breasts after the first MR scan and then underwent the second MR scan. Five post-weaning women underwent a single MR scan. The participants’ information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

| No. | age | Pre scan | Post scan | Post weaning | Parity | Infants’ age (Month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | 8 | |

| 2 | 36 | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | 11 | |

| 3 | 35 | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 34 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | 2 | |

| 5 | 35 | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | 2 | |

| 6 | 32 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | 7 | |

| 7 | 37 | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | 6 | |

| 8 | 36 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | 2 | |

| 9 | 34 | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | 13 | |

| 10 | 37 | ✓ | ✓ | 4 | 2 | |

| 11 | 31 | ✓ | ✓ | 1 | 3 | |

| 12 | 36 | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | 2 | |

| 13 | 34 | (10) | 2 | 12 | ||

| 14 | 34 | (4) | 2 | 10 | ||

| 15 | 43 | (7) | 1 | 11 | ||

| 16 | 33 | (2) | 1 | 5 | ||

| 17 | 42 | (8) | 1 | 10 |

Number in parentheses indicates the months after complete weaning.

Pre or post scan indicates the scan pre-breastfeeding or post-breastfeeding.

2.2. MRI acquisitions

Breast MRI was performed using a 3 T system (MAGNETOM Prisma fit, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a dedicated 18-channel breast array coil. Bilateral fat-suppressed axial T2-weighted images (T2WI) (repetition time/echo time 5500 ms/70 ms, flip angle 140°, Turbo Factor 20, field of view 330 × 330 mm2, matrix 336 × 448, slice thickness 3 mm, acquisition time 1.5 min) were obtained.

Bilateral axial T1-weighted images (T1WI) (repetition time/echo time 4.95 ms/2.46 ms, flip angle 15°, field of view 330 × 330 mm2, matrix 398 × 480, slice thickness 1.5 mm, acquisition time 2 min) were acquired. Monopolar DW images in the axial plane were then obtained as trace images using single shot EPI (prototype sequence) with spectral attenuated inversion recovery (SPAIR) for fat suppression along three orthogonal axes; 16 b values of 0, 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, 70, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, 1000, 1500, 2000, 2500 s/mm2, scan time of 3 min 51 s; repetition time/echo time 4700 ms/56 ms; flip angle 90°, field of view 180 × 330 mm2, matrix 90 × 166, and 3.0 mm slice thickness).

2.3. Regions of interest

The DW image slice containing the largest amount of fibroglandular tissue was selected and regions of interest (ROI) were manually drawn by radiologist A, with 9 years’ experience in breast MRI. The ROI was placed to contain whole normal breast parenchyma observed on the selected DW image, under the morphologic guidance of T1WI and T2WI to avoid inclusion of fatty tissue.

2.4. Data processing

The signals were processed in two steps: first, we estimated the diffusion component, Fdiff, using the kurtosis diffusion model corrected for noise bias [11]; then, we estimated the perfusion component, Fperf, against the residual signal, after the diffusion component was removed:

| M(b) = [S(b)2 + NCF]1/2 | (1) |

| S(b) = fIVIMFperf + (1−fIVIM) Fdiff | (2) |

where M(b) is the overall measured signal obtained from trace-weighted images, fIVIM is the volume fraction of incoherently flowing blood in the tissue, and NCF is the noise correction factor (estimated at 1130 in our system) [11].

The signal attenuation curve, M(b), against the b values between 200 and 2500 s/mm2 was fitted using the kurtosis diffusion model to estimate ADC0 (virtual ADC at very low b values) and K (kurtosis) (Eqs. (1)–(3));

| Fdiff = exp [−bADC0 + (bADC0)2K/6] | (3) |

Then the diffusion component was subtracted from the signal and the remaining signal for b values <200 s/mm2 was fitted using the IVIM model to obtain estimates of the flowing blood fraction, fIVIM, and pseudo-diffusion coefficient, D*;

| fIVIMFperf = S(b) − (1−fIVIM) Fdiff | (4) |

| Fperf = exp (−b D*) | (5) |

Synthetic ADC, encompassing both Gaussian and non-Gaussian effects [15], was calculated as:

| sADC = ln [Sn(Lb)/Sn(Hb)]/(Hb − Lb) | (6) |

where Lb is the low key b value and Hb is the high key b value ([Lb, Hb] = [200,1500]) as defined previously [15].

Estimation of this synthetic ADC requires only two key b values, and can be obtained with almost the same scanning time as standard ADC with two b values (e.g. b = 0, 1000 s/mm2).

This process was performed on ROIs using the nonlinear subspace trust region fitting algorithm built into commercial software (Matlab®, Mathworks, Natick MA, USA). Pixel-based ADC0 maps were generated.

2.5. Image analysis

To evaluate the heterogeneous pattern of ADC0 values in lactating breasts, the contrast changes observed extending from the nipple to the posterior breast direction (retroareolar score) and along the segments in any quadrants of the breast (segmental score) characteristic of lactating breasts was scored. The contrast in the nipple-to-posterior-breast direction indicates the difference in ADC0 values from anterior to posterior. The contrast with segmental pattern indicates the difference of ADC0 values of a cone or triangular area with its apex pointing at the nipple and other remaining area of the breast. (segmental distribution is defined in BI-RADS [19]).

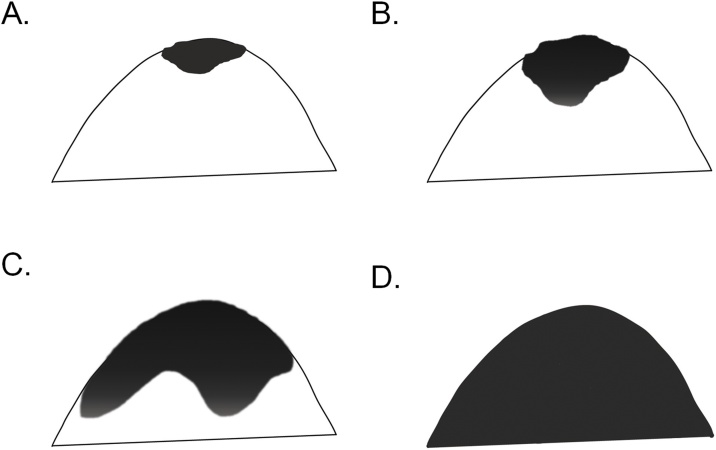

1) The contrast in the nipple-to-posterior-breast direction (retroareolar score) uses a semi-quantitative score of 0–3 (Table 2, Fig. 1): The percentage of the area involved by high ADC0 is scored 3 for <20%; 2 for <50%; 1 for >50%; and 0 for almost 100% homogeneity with no contrasting areas.

Table 2.

Retroareolar score using a semiquantitative scale (0–3).

| 3 | High ADC0 area in the anterior breast involves <20% of the entire breast; prominent contrast between high ADC0 area in anterior breast and low ADC0 area in posterior breast |

| 2 | High ADC0 area in the anterior breast involves <50% of entire breast; marked contrast between high ADC0 area in anterior breast and low ADC0 area in posterior breast |

| 1 | High ADC0 area in the anterior breast involves >50% of entire breast; modest contrast is noted between the high-ADC0 area in the anterior breast and low ADC0 area in the posterior breast |

| 0 | High ADC0 area involves almost the entire breast; almost no contrast |

Fig. 1.

Schema of retroareolar score using a semi-quantitative scale (0–3).

(A) 3, (B) 2, (C) 1, (D) 0.

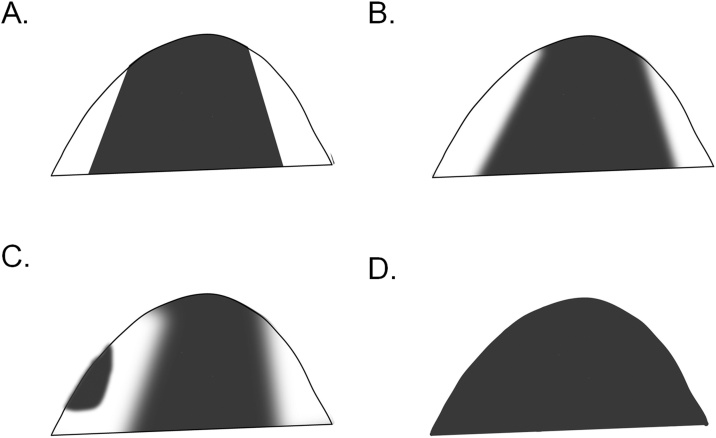

2) The contrast among the segments (segmental score) is scored semi-quantitatively from 0 to 3 (Table 3, Fig. 2). A score of 3 is given if the contrast of ADC0 values of a cone or triangular area with its apex pointing at the nipple and other remaining area of the breast is prominent. A score of 2 is given if it is marked; a score of 1 implies a modest degree of contrast; 0 implies no contrast.

Table 3.

Segmental score using a semiquantitative scale (0–3).

| 3 | Prominent contrast between low- and high-ADC0 areas |

| 2 | Marked contrast between low- and high-ADC0 areas; the border is indistinct, with homogeneous distribution of low-ADC0 areas |

| 1 | Slight contrast between low- and high-ADC0 areas; low-ADC0 areas are slightly heterogeneous and are admixed with some high-ADC0 areas |

| 0 | High-ADC0 area involves almost the entire breast; almost no contrast |

Fig. 2.

Schema of segmental score using a semi-quantitative scale (0–3).

(A) 3, (B) 2, (C) 1, (D) 0.

Two radiologists (reader B and reader C; 8 and 19 years’ experience in breast MRI, respectively) evaluated the two sets of features on ADC0 maps for each case.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Wilcoxon signed rank tests (paired samples) were used for the comparison of the diffusion and IVIM parameters between pre- and post-breastfeeding. Mann-Whitney (independent samples) tests were used for the comparison of diffusion and IVIM parameters between breasts in the post-weaning period and pre- or post-breastfeeding. Bonferroni’s correction was performed to account for multiple comparisons.

Retroareolar and segmental scores were analyzed using Wilcoxon signed rank tests, and the interobserver variability of radiologists B and C was evaluated using interrater agreement (k). Agreement was defined as almost perfect (0.8–1.0), substantial (0.6–0.8) and moderate (0.4–0.6). P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All the statistical analysis was performed using commercial statistical software (Medcalc® version 11.3.2.0, Medcalc software, Mariakerke, Belgium).

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of diffusion and IVIM parameters

ROI size (median values and interquartile ranges) were 22.9 (15.2–30.9) cm2, 16.8 (11.4–27.6) cm2 in lactating women pre- and post-breastfeeding, and 8.1 (3.7–10.9) cm2 in women post-weaning, respectively.

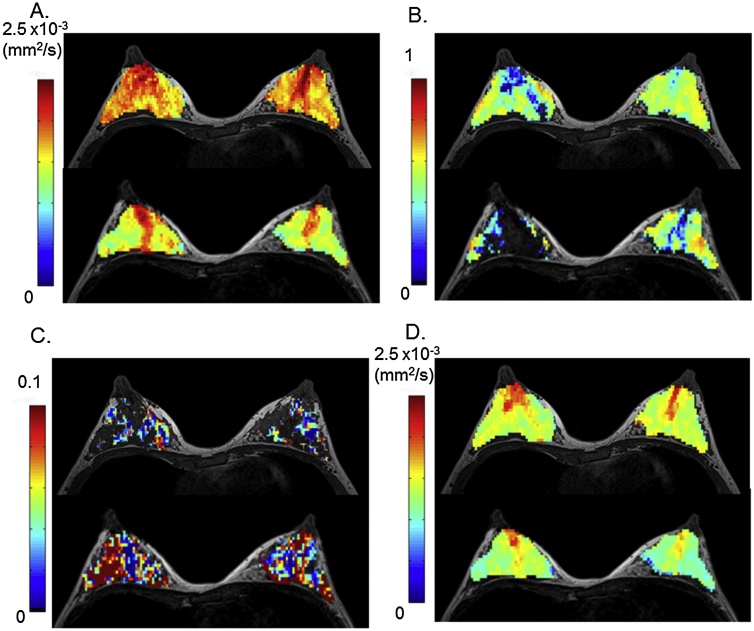

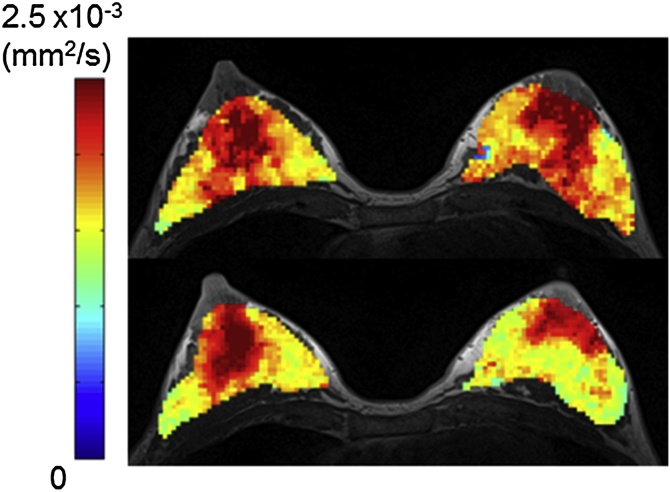

Representative non-Gaussian diffusion and IVIM parametric maps of a lactating breast are shown in Fig. 3. The volume of the breast decreases, and the distribution of ADC0, sADC and K values becomes more heterogeneous after breastfeeding. ADC0 and sADC values decrease in the whole breast except the retroareolar region (Fig. 3A, D). The increase of fIVIM values after breastfeeding was marked, as shown by the increase in red pixels in Fig. 3C.

Fig. 3.

Diffusion and IVIM MRI parametric maps before (upper row) and after (lower row) breastfeeding.

32-year-old lactating volunteer with a 7-month-old baby. The upper row images were scanned pre-breastfeeding, and the lower row images were scanned post-breastfeeding. Axial diffusion and IVIM MRI maps were overlaid on T1-weighted images.

(A) ADC0 map: There is a marked decrease in ADC0 values, sparing the retroareolar region. The retroareolar score increased from 1.5 (pre-breastfeeding) to 2 (post-breastfeeding) for the right breast, and from 2.5 (pre-breastfeeding) to 3 (post-breastfeeding) for the left breast. The segmental score increased from 0.5 (pre-breastfeeding) to 2 (post-breastfeeding) for the right breast, and from 0.5 (pre-breastfeeding) to 2.5 (post-breastfeeding) for the left breast.

(B) K map: A decrease in K values is remarkable in the central parts of the right breast post-breastfeeding.

(C) fIVIM map: An increase in fIVIM values is observed in both breasts post-breastfeeding.

(D) sADC map: sADC values decrease in both breasts post-breastfeeding.

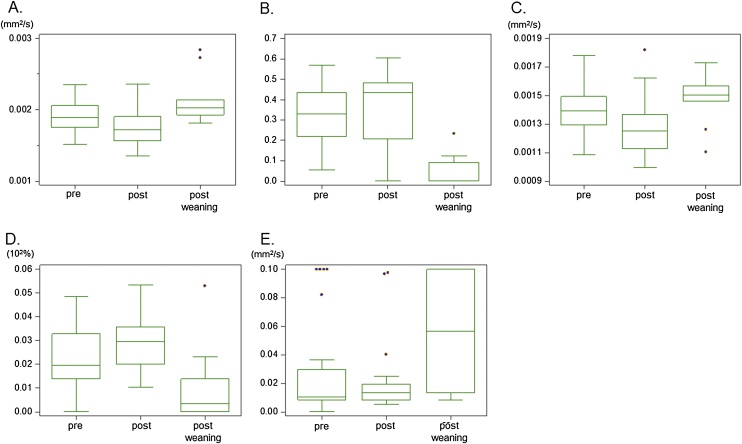

The values of diffusion and IVIM parameters in pre- and post-breastfeeding and post-weaning subjects are summarized in Table 4, Table 5 and Fig. 4.

Table 4.

Diffusion and IVIM values in lactating women.

| Lactating women (two scans; 24 breasts) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre breastfeeding | Post breastfeeding | Change (%) | P Value | |

| ADC0 (10−3 mm2/s) | 1.90 (1.78–2.05) | 1.72 (1.58–1.90) | -8.0 (-11.8– -5.3) | <0.001 |

| K | 0.33 (0.22–0.43) | 0.44 (0.22–0.48) | 19.7 (3.4–42.0) | <0.05 |

| sADC (10−3mm2/s) | 1.39 (1.30–1.49) | 1.25 (1.13–1.37) | -8.0 (-12.4– -5.4) | <0.001 |

| fIVIM (%) | 1.97 (1.41–3.25) | 2.97 (2.04–3.55) | 53.6 (1.9–128.6) | <0.01 |

| D* (10−3 mm2/s) | 10.6 (8.53–26.5) | 13.4 (8.34–19.6) | -1.8 (-37.9–48.6) | 1.00 |

Median values and interquartile ranges are provided. P values are Bonferroni corrected.

Change is the percentage change (%) of parameter values between pre- and post-breastfeeding.

Table 5.

Diffusion and IVIM values in post-weaning women.

| Women post-weaning (one scan; 10 breasts) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| P Valuea | P Valueb | ||

| ADC0 (10−3 mm2/s) | 2.03 (1.93–2.14) | 0.15 | 0.005 |

| K | 0.00 (0.00–0.07) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| sADC (10−3mm2/s) | 1.51 (1.47–1.57) | 0.31 | <0.05 |

| fIVIM (%) | 0.33 (0.00–1.22) | 0.05 | <0.01 |

| D* (10−3 mm2/s) | 56.9 (13.5–100) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Median values and interquartile ranges are provided. P values are Bonferroni corrected.

Change is the percentage change (%) of parameter values between pre- and post-breastfeeding.

indicates comparison with pre-breastfeeding in lactating breasts (Table 4).

indicates comparison with post-breastfeeding in lactating breasts (Table 4).

Fig. 4.

Box-and-whisker plots of the diffusion and IVIM parameters in pre-breastfeeding, post-breastfeeding, and post-weaning.

(A) ADC0 (B) K (C) sADC (D) fIVIM (E) D* values.

ADC0 and sADC significantly decreased, and K and fIVIM significantly increased after breastfeeding. K in post-weaning was significantly lower than that in pre-breastfeeding breasts. Significant changes in ADC0, K, sADC, and fIVIM values were found between post-breastfeeding breasts and post-weaning breasts. Please see Table 4, Table 5 for statistical data.

Significantly lower ADC0 and sADC values were observed after breastfeeding (P < 0.001, and 0.001, respectively) while K values significantly increased (P < 0.05). Significant increases in fIVIM values were observed after breastfeeding (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in D* values between pre- and post-breastfeeding.

ADC0 and sADC values tended to be higher in post-weaning breasts compared with the lactation period, and their difference reached significance when comparing post-weaning breasts with post-breastfeeding (ADC0: P = 0.005, sADC: P < 0.05, respectively). Significantly lower K was found in post-weaning breasts, both in comparison with pre- and post-breastfeeding (P < 0.001 and <0.001, respectively). Lower fIVIM values tended to be observed in post-weaning breasts compared with lactating breasts pre- or post-breastfeeding, with a significant difference when comparing post-breastfeeding and post-weaning breasts (P < 0.01).

3.2. Comparison of the contrast along nipple-to-posterior-breast direction (retroareolar score) and segmental pattern (segmental score) between pre- and post-breastfeeding

A high correlation between radiologists B and C (weighted κ was 0.87 for retroareolar score and 0.89 for segmental score) was observed; hence, both scores were averaged for the analysis.

Examples of ADC0 maps of pre- and post-breastfeeding breasts as well as their corresponding scores are shown in Fig. 3A and Fig. 5. Both cases indicate the increase in retroareolar and segmental scores, suggesting that the distribution of ADC0 values in lactating breasts becomes more heterogeneous post-breastfeeding. The ADC0 map in one patient in lactation is shown in Appendix Figure. Clear contrast of ADC0 values between the lesion and normal breast parenchyma is remarkable.

Fig. 5.

Example of ADC0 map of breasts pre- and post-breastfeeding.

36-year-old lactating volunteer with a 2-month-old baby. Axial ADC0 maps were overlaid on T1-weighted images. The upper row image was acquired pre-breastfeeding, and the lower row image was acquired post-breastfeeding. The retroareolar score increased from 1.5 (pre-breastfeeding) to 2 (post-breastfeeding) for both breasts. The segmental score increased from 2 (pre-breastfeeding) to 3 (post-breastfeeding) for both breasts.

The median and interquartile range of the retroareolar scores significantly increased from 1.0 (0.0–1.5) pre-breastfeeding to 2.0 (1.0–2.0) post-breastfeeding (P < 0.0001). A significant increase in segmental scores was also observed from 0.5 (0.0–1.13) pre-breastfeeding to 2.0 (1.0–3.0) post-breastfeeding (P = 0.0001).

4. Discussion

Changes in IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters of lactating breasts among pre- and post-breastfeeding and post-weaning were investigated both in quantitative and semi-quantitative manners in this study. We have shown that both ADC0 and sADC values decrease approximately 8% in post- compared with pre-breastfeeding.

In addition, the evaluation of ADC0 distribution using scores obtained from both retroareolar and segmental scores indicate that the distribution of ADC0 values become more inhomogeneous along both anterior-posterior and inner-outer directions. This also means that ADC0 values in some specified areas of the breasts (posterior breast, or a cone or triangular area with its apex pointing at the nipple) post-breastfeeding tend to be lower than the mean ADC0 value of the whole breast. Thus, the above results suggest that pre-breastfeeding status is optimal for breast DW images, to obtain good contrast of ADC values between cancer and normal breast parenchyma, allowing higher and more homogeneous ADC values in normal breast parenchyma, and a better contrast between breast parenchyma and lesions.

ADC0 and sADC values in lactating breasts were lower than those found in post-weaning breasts (2–10 months after the complete cessation of breastfeeding), probably due to the presence of low-diffusion protein or fat in the milk. Conversely, Nissan et al. have reported higher MD (mean diffusion, which is similar to ADC) values in lactating breasts (1.68 ± 0.11 × 10−3 mm2/s) compared with post-weaning breasts (1.58 ± 0.14 × 10−3 mm2/s) [17]. There are large standard deviations between them and our study suggests that the period of post-weaning or pre-/post-breastfeeding status during lactation has a significant effect on ADC values.

Sah et al. reported significantly lower ADC values in lesions compared with those in lactating breasts [18], and this trend is in accordance with the comparison from our previous results [11] (mean and CI values of ADC0 of 1.05 [0.94–1.17] × 10−3 mm2/s in malignant lesions, which are relatively lower than ADC0 values of 1.90 [1.78–2.05] × 10−3 mm2/s in pre-, 1.72 [1.58–1.90] × 10−3 mm2/s in post-breastfeeding in this study). Furthermore, the ADC0 values pre-breastfeeding in this study tended to be slightly lower than those in normal breast tissue (1.97 [1.87–2.07] x 10−3 mm2/s), and the ADC0 values post-breastfeeding were comparable even to those in benign lesions (1.73 [1.51–1.94] x 10−3 mm2/s) in our previous investigation [11]. Lower ADC0 value in invasive ductal carcinoma was also found compared to normal breast parenchyma (Appendix Figure), however, the smaller malignant lesions might exhibit artificially higher ADC values and more challenging to detect, due to possible partial volume effects with surrounding normal tissues associated with a high ADC value, particular in pre-breastfeeding.

Parametric maps of non-Gaussian diffusion and IVIM might provide some clues to understand the physiological process during lactation, as shown in Fig. 3. The central area of the right breast post-breastfeeding shows K = 0, which might suggest the presence of retained milk post-breastfeeding. Decreased ADC0 and sADC as well as increased IVIM fractions are observed in the breasts, suggesting some dynamic change during lactation, such as milk passing from the alveoli to the nipple through the breastfeeding process [20].

IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters further changed post-breastfeeding. The areas with lower ADC0 and sADC values post-breastfeeding showed segmental distribution, which might reflect the changes in active breast lobules. Higher IVIM values post-breastfeeding might result from milk flow in ducts, as milk production is stimulated by breastfeeding and progresses from alveoli to the nipple [20].

The change in the retroareolar scores between pre- and post-breastfeeding indicates that high ADC0 values near the nipple remained and even became prominent after breastfeeding. High ADC0 and low K values around the nipple could suggest the retention of milk, and there might be “functional” lactiferous sinuses, even though an ultrasound study concluded that anatomically suggested lactiferous sinuses [21] were not observed with ultrasound [22]. Our results again suggest that IVIM and diffusion MRI might be performed in lactating women ideally pre-breastfeeding when ADC values are higher and more homogeneous, allowing a better contrast between breast parenchyma and lesions.

The limitation of our study includes a small sample size. The influence of lactation status on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) images has not been investigated. More evidence as to the appropriate time to scan lactating breasts with MRI is needed to provide optimum contrast between breast lesions and normal tissue for cancer diagnosis in lactating patients. Topographical changes in DWI contrast and the difference of ROI size between pre and post breastfeeding and post-weaning women might have some effect on IVIM and diffusion parameters. IVIM and diffusion parameters might also depend on the hormonal status (e.g. menstrual period), however, this relationship has not been investigated in our study. Partridge et al. found the relatively small coefficients of variations of ADC values in normal breast tissue during the menstrual cycle [23], while the effect of hormonal status on IVIM parameters has remained unknown.

In conclusion, changes in IVIM and non-Gaussian diffusion parameters were significant between pre- and post-breastfeeding status, and care needs to be taken in interpreting DWI data in lactating breasts; DWI acquisition in pre-breastfeeding status may be preferable due to good contrast between breast lesions and normal breast parenchyma.

Conflict of interest

All the authors below declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Yuta Urushibata and Mr. Hirokazu Kawaguchi from Siemens Healthcare K.K. for the excellent and knowledgeable support. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Thorsten Feiweier from Siemens Healthcare for providing the prototype sequence used in this work. The authors would like to thank Dr. Libby Cone for excellent proofreading, and the reviewers for the constructive and helpful comments. This work was supported by Hakubi Project of Kyoto University and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP15K19786.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejro.2018.01.003.

Contributor Information

Mami Iima, Email: mamiiima@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Masako Kataoka, Email: makok@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Rena Sakaguchi, Email: rena@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Shotaro Kanao, Email: kanaos@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Natsuko Onishi, Email: natsucom@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Makiko Kawai, Email: hiraima@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Katsutoshi Murata, Email: katsutoshi.murata@siemens-healthineers.com.

Kaori Togashi, Email: ktogashi@kuhp.kyoto-u.ac.jp.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Vashi R., Hooley R., Butler R., Geisel J., Philpotts L. Breast imaging of the pregnant and lactating patient: imaging modalities and pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013;200(2):321–328. doi: 10.2214/ajr.12.9814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keyser E.A., Staat B.C., Fausett M.B., Shields A.D. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Rev. Obstetrics and Gynecol. 2012;5(2):94–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard-Anderson J., Ganz P.A., Bower J.E., Stanton A.L. Quality of life fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012;104(5):386–405. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rofsky N.M., Weinreb J.C., Litt A.W. Quantitative analysis of gadopentetate dimeglumine excreted in breast milk. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 1993;3(1):131–132. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald R.J., McDonald J.S., Kallmes D.F., Jentoft M.E., Murray D.L., Thielen K.R., Williamson E.E., Eckel L.J. Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2015;275(3):772–782. doi: 10.1148/radiol.15150025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ray J.G., Vermeulen M.J., Bharatha A., Montanera W.J., Park A.L. Association between MRI exposure during pregnancy and fetal and childhood outcomes. JAMA. 2016;316(9):952–961. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talele A.C., Slanetz P.J., Edmister W.B., Yeh E.D., Kopans D.B. The lactating breast: MRI findings and literature review. Breast J. 2003;9(3):237–240. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2003.09322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.N.C.C. Network . 2017. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis Version 1.2017-June 2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmichael H., Matsen C., Freer P., Kohlmann W., Stein M., Buys S.S., Colonna S. Breast cancer screening of pregnant and breastfeeding women with BRCA mutations. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2017;162(2):225–230. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4122-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Partridge S.C., Nissan N., Rahbar H., Kitsch A.E., Sigmund E.E. Diffusion-weighted breast MRI: clinical applications and emerging techniques. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2017;45(2):337–355. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iima M., Yano K., Kataoka M., Umehana M., Murata K., Kanao S., Togashi K., Le Bihan D. Quantitative non-Gaussian diffusion and intravoxel incoherent motion magnetic resonance imaging: differentiation of malignant and benign breast lesions. Invest. Radiol. 2015;50(4):205–211. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu C., Liang C., Liu Z., Zhang S., Huang B. Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) in evaluation of breast lesions: comparison with conventional DWI. Eur. J. Radiol. 2013;82(12):e782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho G.Y., Moy L., Kim S.G., Baete S.H., Moccaldi M., Babb J.S., Sodickson D.K., Sigmund E.E. Evaluation of breast cancer using intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) histogram analysis: comparison with malignant status histological subtype, and molecular prognostic factors. Eur. Radiol. 2016;26(8):2547–2558. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iima M., Kataoka M., Kanao S., Onishi N., Kawai M., Ohashi A., Sakaguchi R., Toi M., Togashi K. Intravoxel incoherent motion and quantitative non-Gaussian diffusion MR imaging: evaluation of the diagnostic and prognostic value of several markers of malignant and benign breast lesions. Radiology. 2017 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162853. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iima M., Le Bihan D. Clinical intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion MR imaging: past present, and future. Radiology. 2016;278(1):13–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015150244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nissan N., Furman-Haran E., Shapiro-Feinberg M., Grobgeld D., Degani H. Diffusion-tensor MR imaging of the breast: hormonal regulation. Radiology. 2014;271(3):672–680. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nissan N., Furman-Haran E., Shapiro-Feinberg M., Grobgeld D., Degani H. Monitoring in-vivo the mammary gland microstructure during morphogenesis from lactation to post-weaning using diffusion tensor MRI. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2017;22(3):193–202. doi: 10.1007/s10911-017-9383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sah R.G., Agarwal K., Sharma U., Parshad R., Seenu V., Jagannathan N.R. Characterization of malignant breast tissue of breast cancer patients and the normal breast tissue of healthy lactating women volunteers using diffusion MRI and in vivo 1H MR spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2015;41(1):169–174. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Orsi C.J., Sickles E.A., Mendelson E.B., Morris E.A. American College of Radiology; Reston, VA: 2013. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geddes D.T. Inside the lactating breast: the latest anatomy research. J. Midwifery Women’s Health. 2007;52(6):556–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper A.P. Longman Orme, Greene Brown and Longman; London, UK: 1840. Anatomy of the Breast. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsay D.T., Kent J.C., Hartmann R.A., Hartman P.E. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. J. Anat. 2005;206(6):525–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2005.00417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Partridge S.C., McKinnon G.C., Henry R.G., Hylton N.M. Menstrual cycle variation of apparent diffusion coefficients measured in the normal breast using MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2001;14(4):433–438. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.