Abstract

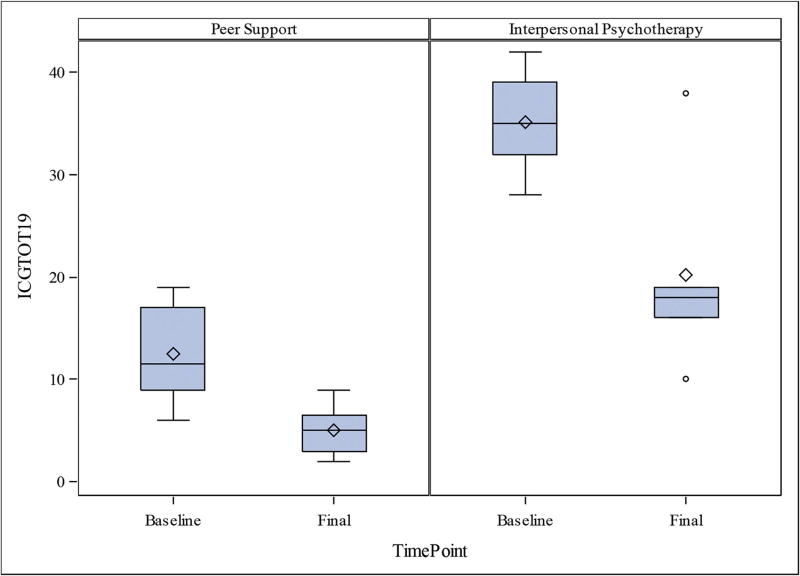

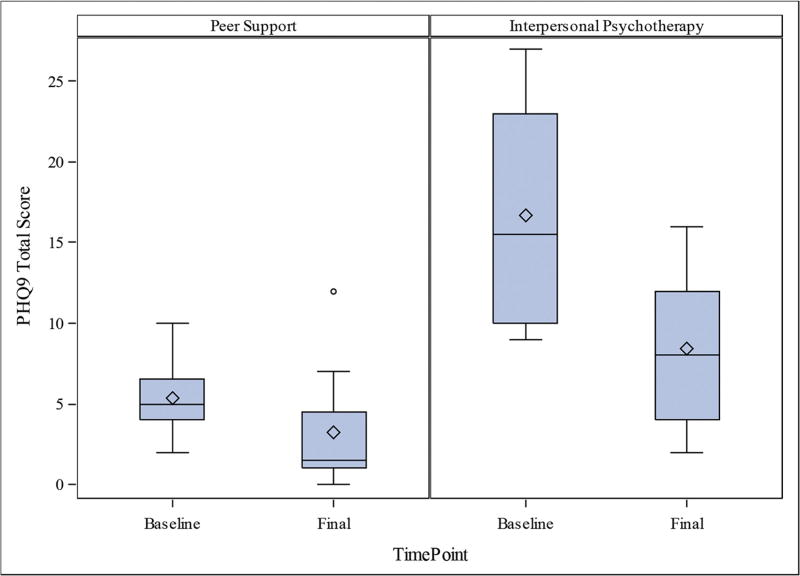

This feasibility and acceptance pilot study for preventing complications of bereavement within the first year post loss recruited 20 adult grievers within 9 months of becoming bereft and assigned consenting subjects to peer supporters trained by a non-profit bereavement support organization for weekly or bi-weekly telephone-based peer support until month 13 post-loss. Subjects who met DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder or showed an Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) score exceeding 19, 6 months or more post loss, were assigned to 12 to 16 weeks of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) with an experienced therapist. Eight and six subjects completed the protocol assigned to peer support and IPT, respectively, with pre/post Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scores of 5.38 (2.45) versus 3.25 (4.13) (p = 0.266) and 16.67 (7.17) versus 8.40 (5.73) (p =0.063); and pre/post ICG scores of 12.50 (4.72) versus 5.00 (2.51) (p = 0.016) and 35.17 (5.12) versus 8.4 (5.73) (p = 0.063). Implications of this two-tiered model of early intervention for preventing complications of grief are discussed.

Keywords: Bereavement, grief, peer support, interspersonal psychotherapy, complicated grief

Grieving the loss of another emotionally important human being is a universal phenomenon that the majority of grievers manage to cope with adequately over time using traditional psychosocial supports from family, friends, and religious or spiritual advisors. Grievers without an adequate support system, or who have other predisposing risk factors such as pre-existing depression or anxiety disorders, or who sustain multiple losses can develop complications resulting from the grieving process such as bereavement-related major depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and complicated grief (sometimes called prolonged grief disorder, and now called persistent complex bereavement disorder [PCBD] in section II of DSM-51). (Note: For this communication we will consider these terms to be roughly equivalent and interchangeable.) The modern view of grieving, as described by Shear et al., has two stages: acute and integrated.2 In acute grief, emotions such as disbelief, sadness, crying, pining, anxiety, sleep disturbance, and preoccupation with images of the deceased dominate the griever’s mental life and can cause a temporary suspension of usual capabilities and activities in work or school performance, or even parenting. Grievers are frequently known to have changes in social rhythms, to be more socially isolative, and to neglect their own health. Grief symptoms are “center stage” in acute grief and exclude most other thoughts. In contrast, in the integrated stage of grieving, the predominantly painful or negative affects evolve into a permanent background state of awareness and are no longer “center stage” as proportionally more time and energy is devoted to restorative activities. This evolution from acute to integrated grieving generally occurs over a 6-month period after loss on average. In the integrative stage of grief, predominantly negative effects are gradually replaced by more positive or bittersweet ones. Simply put, those who remain “stuck” in some aspect of acute grief after 6 to 12 months have elapsed since their loss are said to suffer from PCBD.

The symptoms of PCBD can lead to debilitating morbidity in up to 10% of grievers, can persist for years or even decades, and are often treatment-resistant to traditional psychotherapy approaches. Prigerson et al. showed that PCBD symptoms can also be debilitating in the absence of a depressive component, although the two commonly coexist.3 Pharmacotherapy can reduce depressive or anxious symptoms in the course of grieving, but medications cannot help a struggling griever with the personalized meaning of their loss.4–7 A recently completed four-site randomized controlled trial comparing a new psychotherapy specifically designed for PCBD with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram and their combination showed that citalopram conferred no added benefit.8

Treatment interventions to the present have been designed to reduce symptoms of PCBD after it has developed. Treatment modalities that have shown at lease some efficacy include structured writing assignments,9 interpersonal psychotherapy,10 complicated grief therapy,11,12 and cognitive behavioral therapy approaches delivered face to face or via the Internet,13,14 all of which rely on professional intervention at some level. All of these studies required grieving individuals to meet severity criteria for PCBD symptoms for inclusion.

Preventing PCBD would allay suffering for the subset of grievers destined to develop it but, as yet, there is no consensus on which risk factors are most important for identifying that subgroup a priori for preventative intervention. Providing a general intervention for all grievers using professional services toward a goal of preventing complications of grief would be cost-prohibitive and may not be necessary for the majority of grievers who will adjust overtime with the general support of family, friends, and religious/spiritual advisors. We explored whether a telephone intervention providing education and additional targeted support from trained volunteer peer supporters could be a cost-effective intervention to prevent complications of major depressive disorder or PCBD within the first year post-loss. During the first 6 months of grieving, it is customary in grief-related research not to attribute much weight to grief severity rating scale scores because they often fluctuate as the acute grieving process evolves. Perhaps it is precisely during this time period that complications of grief might best be prevented with the correct supportive intervention(s).

In this communication, we report on a pilot two-tiered intervention aimed at preventing two potential complications of grieving (major depression and PCBD) using peer supporters trained by the Good Grief Center (GGC) in Pittsburgh as a practical and cost-effective model that provides early intervention without being overly burdensome while providing more intensive intervention using professional psychotherapists when and if severity criteria are met for subsyndromal PCBD or major depression within the first 9 months post loss.

GGC volunteers are adults who are supervised by an experienced professional social worker after providing them with 10 hours of training classes focused on common and complicated manifestations of grieving, active listening techniques, and empathic responses to case scenarios.

METHODS

In this pilot study we enlisted GGC trained volunteers to provide peer support for our recruited subjects who were recruited from primary care practices with already established relationships from prior studies at the University of Pittsburgh, word of mouth, or clinician referrals. Our intent was to test the feasibility and acceptance of recruiting and retaining subjects for this protocol within the first 9 months post loss that would allow at least 16 weeks of intervention (a potential full course of interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT]) prior to the 13-month post-loss endpoint; we chose this endpoint to avoid potential coincidental anniversary reactions at 12 months post loss when final ratings would be obtained, while remaining essentially within the 1-year mark for intervention. Consenting subjects were assigned to a peer supporter who contacted them by telephone every 1 to 2 weeks throughout.

Procedures

IPT15 was delivered by face-to-face visits or by telephone according to subject preference. Subjects already assigned to a peer supporter could also elect to continue with their peer supporter contacts simultaneously while receiving IPT. All IPT therapists had at least 4 years of experience delivering IPT. Subjects received weekly IPT if they 1) met DSM-V criteria for major depression at baseline or any time during the study (Patient Health Questionnaire [PHQ-9]16 scores were also obtained to quantify depressive symptoms) or 2) if their Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG) score17 reached 20 or higher after 6 or more months post loss. Subjects who met DSM-V criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) at baseline, or who scored 20 or higher on the ICG (used as the threshold for subsyndromal PCBD) 6 months or more post loss were not assigned to a peer supporter at any time as we felt it was unethical to assign them to a nonprofessional—rather, they were enrolled directly in IPT with a trained therapist.

The primary outcome of this pilot study was to test the feasibility of recruiting and retaining recently bereft subjects for protocol completion. A secondary outcome, despite the small sample size, was to track the extent to which either intervention (peer support and/or IPT) succeeded in preventing or successfully treating major depression (defined as no longer meeting DSM-V criteria for MDD or PCBD as indicated by a grief severity score on the ICG of less than 30 (the minimum score that defines PCBD in this protocol). The inclusion criteria for this pilot study were: a minimum age of 18 years, the death of someone emotionally close within the prior 9 months, and an ongoing relationship with a primary care physician (PCP). Subjects were excluded if they met criteria for a psychotic disorder, were deemed to have a serious addiction to alcohol or drugs, or if they could not speak adequate English or hear adequately over the telephone. The University of Pittsburgh institutional review board approved the protocol for enrolling 20 subjects in this pilot study.

We chose to make this protocol two-tiered to allow assignment to peer supporters for all except those in need of a higher level of care, who would then receive professional psychotherapy. This strategy also provided an easily acceptable back-up strategy for nonprofessional peer supporters. We chose IPT as a good fit for this pilot study as “unresolved grief” is one of the four core foci of intervention in IPT that has also showed modest efficacy even for treating PCBD itself in a randomized controlled trial comparing IPT with complicated grief therapy (28% versus 64% reduction in ICG scores, respectively).10 Furthermore, the goal of this pilot study was to prevent PCBD—we did not seek to treat PCBD once it has already developed. Supervision was provided for the IPT psychotherapists on a weekly basis and for peer supporters on a monthly basis by the Principal Investigator (MM).

Patient Evaluation

All subjects were evaluated over the telephone by an independent rater who, after obtaining consent to screen, completed a brief psychiatric history and administered standardized rating scales for measuring grief severity (ICG) and depression severity (PHQ-9) ratings. Subjects who met admission criteria were then offered consent for study participation. Subjects were recruited for a screening interview over the telephone by asking them to participate in a study approved by their PCP to track the health effects of grieving. This rationale for participation was easier to accept by potential subjects who did not feel they necessarily needed help with their grief at that moment. Independent raters also obtained monthly ratings of mood (PHQ-9 and DSM-V criteria for MDD) and grief intensity (ICG scores).

Consenting subjects agreed to be assigned to a peer supporter for telephone contact every 1 to 2 weeks for supportive “check-in-calls”. As this protocol was designed to prevent complications of grieving, we anticipated that some subjects would be coping with their loss without untoward distress at the time of recruitment but that a phone call every 2 weeks would be adequate for following their grieving progress to ascertain whether they developed subsequent complications without being seen as too burdensome. Peer supporters were trained to offer empathic listening during check-in calls; to encourage compliance with scheduled medical follow-up visits, medication regimens, good nutrition, appropriate exercise (cleared with the primary care physician or PCP); and to take advantage of social supports available to them.

Pharmacotherapy and Triage for Higher Levels of Care by Subject PCPs

Peer supporters instructed subjects to consult with their PCP if a subject mentioned that they thought they were overusing alcohol or other drugs. PCPs were notified of their patient’s participation in the study and both subject and PCP understood that although no psychotropic medications were provided by the protocol, PCPs were free to use their discretion in prescribing as they saw fit and that the protocol would merely track their use. Subjects already taking psychotropic medications were not asked to make any changes but were asked, if possible, to continue the same doses throughout the study to keep this variable constant and thus avoid a potential confound in the interpretation of study results. It was also made clear that subjects were depending upon their PCP to triage their care appropriately if it was determined, in the PCP’s judgment, that a higher level of care was required including emergency care for suicidal ideation. The decision to rely on PCPs for safety assessment on a 24/7 basis was made, in part, as subjects were recruited from a wide geographic area of several counties. Offsite psychiatric consultation was offered by protocol psychiatrists to any subject’s PCP who requested it.

Monthly ratings of mood and grief severity were obtained by independent raters over the telephone until the study endpoint at 13 months post-loss.

RESULTS

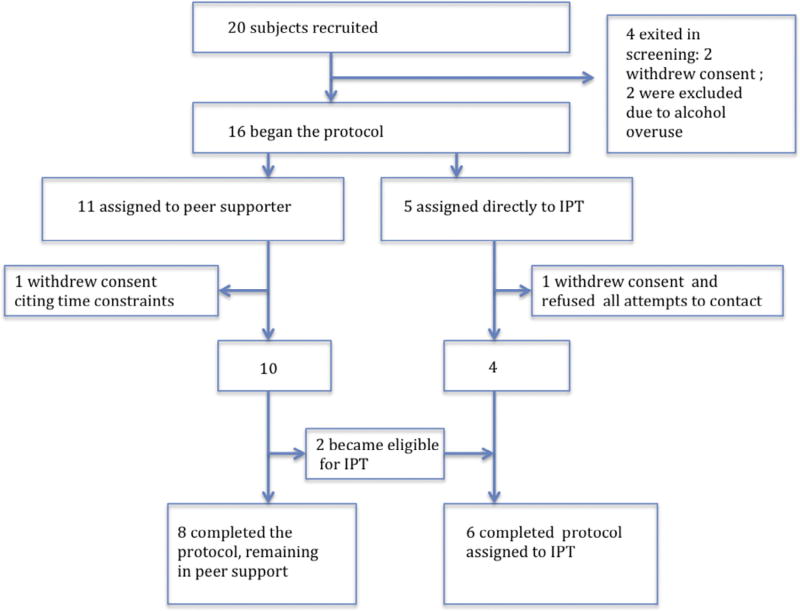

Figure 1 shows the flow of the recruited subjects approved by the institutional review board and their beginning and final status at the protocol endpoint.

Figure 1.

Flow of the recruited subjects approved for the study.

Two subjects dropped out in screening (one was no longer interested, and one could not commit the time); two were terminated because of heavy alcohol abuse judged as likely to interfere with participation (one was later diagnosed with metastatic cancer [mesothelioma] and died within 2 months); of 11 subjects assigned to peer support, one dropped out after one session (unable to commit the time) and 10 completed the study (2 became eligible for and transitioned to IPT and 8 remained with their peer supporter); of the 7 subjects assigned to IPT throughout the study, one dropped out after three sessions of IPT regarding the death of her husband by suicide without stating a reason and refused all attempts to contact her further and 6 completed the protocol in the IPT cell. Two subjects became eligible for IPT during the course of the study after having been originally assigned to a peer supporter: One met criteria for MDD and one scored above 20 on the ICG in the window between 6 months post loss and the study endpoint at 13 months post loss (as per protocol). Both subjects elected to discontinue meeting with their peer supporter while receiving IPT with the stated reason that they wanted to reduce their overall time commitment within the study.

Table 1 shows the demographic data and the proportion of completer subjects who were taking antidepressants throughout the study as well as baseline and 13-month post-loss (study endpoint) comparisons of rating scale scores. Two of the six subjects assigned to IPT elected to come in for face-to-face visits and four were treated via telephone visits. All peer support sessions and all baseline and monthly ratings of mood and grief severity were obtained by telephone contact by design.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| All (N = 14) | Peer Support (N = 8) | Interpersonal Psychotherapy (N = 6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) [n if sample is reduced] | ||

| Age, years | 70.40 (12.22) | 67.18 (13.84) | 74.68 (9.04) |

| No. Female | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| No. Male | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| No. Black | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| No. White | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| Mean education, years | 14.57 (2.79) | 15.00 (2.67) | 14.00 (3.10) |

| Grieving the death of: | |||

| Parent | 6 | 5 | 1 |

| Spouse | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| Child | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nephew | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| No. Sessions | 7.31 (4.52) [n = 13] {Min = 1, Max = 16} | 5.71 (3.50) [n = 7] {Min = 1, Max = 10} | 9.17 (5.15) {Min = 1,Max = 16} |

| No. Suicidal Ideation | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| PHQ-9 total baseline | 10.21 (7.53) | 5.38 (2.45)a | 16.67 (7.17)a |

| PHQ-9 total final | 5.23 (5.26) [n = 13] | 3.25 (4.13) | 8.40 (5.73) [n = 5] |

| ICG score baseline | 22.21 (12.55) | 12.50 (4.72)b | 35.17 (5.12)a |

| ICG score final | 10.85 (10.00) [n = −13] | 5.00 (2.51) | 8.4 (5.73) [n = 5] |

| On antidepressant | 6 | 2 | 4 |

Notes: Pre/post comparisons of PHQ-9 and ICG scores were made using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; ICG: Inventory of Complicated Grief.

There is a significant difference between baseline and final ICG scores (p = 0.016) in the peer support group.

There is no significant difference between baseline and final PHQ-9 scores (p = 0.266) in the peer support group, the IPT group (p = 0.063), or in the baseline and final PHQ-9 score in the IPT group (p = 0.063).

Figures 2 and 3 show the boxplots of ICG and PHQ-9 changes from baseline to endpoint with mean and modal points for comparison.

Figure 2.

Boxplot comparing ICG total score at baseline and at final time point. For the boxplots: the bars are min and max and top and bottom of the box are 75 and 25 percentile, the line within the box is the median, the diamond the mean and the circles are outliers.

Figure 3.

Boxplot comparing PHQ-9 total score at baseline and at final time point. For the boxplots: the bars are min and max and top and bottom of the box are 75 and 25 percentile, the line within the box is the median, the diamond the mean and the circles are outliers.

DISCUSSION

We achieved our primary outcome for this pilot proof-of-concept study by showing that recently bereft subjects could be recruited and retained for up to 13 months post loss. We demonstrated the feasibility of assigning grievers to trained peer supporters for weekly or biweekly telephone check-ins for supportive contact, as well as assignment to a course of IPT with a professional therapist if severity criteria were met.

Two of the 20 subjects approved for the study were excluded in screening and two subjects withdrew their consent in screening; all four of these subjects were excluded from the analysis. Of the 16 subjects who actually began the protocol, one each from the peer support group and IPT groups withdrew consent for a retention rate of 14 of 16 (87.5%) of those who actually began the protocol.

Regarding our secondary outcome, no subject in either group developed syndromal PCBD (a score of 30 or higher on the ICG) at study endpoint, indicating that the use of both peer support and IPT may have offered protection in this small sample against developing PCBD. This pilot study was not powered and did not detect a significant difference in pre/post PHQ-9 or ICG scores except for the change in ICG scores in the peer support group. These findings, however, support our hypothesis that early intervention with assignment to peer support along with professional therapist back-up may prevent the development of complications of grief such as MDD or PCBD.

A satisfaction survey was obtained from subjects regarding their participation in the study using a 0–4 Likert17 rating scale with additional space for written comments; these were generally very positive with all five questions rated as 3 or 4 (satisfied or highly satisfied) regarding the helpfulness of the caller, the information provided about understanding the grieving process, the frequency of check-in calls, the additional monthly telephone calls for rating scales by independent raters, and their overall experience participating in the study. There were a few complaints about timing and availability of calls by peer supporters as well as more details of how they felt helped by individual peer support callers in general and accolades about particular peer supporters as being warm, kind and good listeners.

In a prior study by Shear et al., IPT did show an ability to successfully treat 28% of subjects who were already diagnosed with PCBD (although a higher percentage [64%] of subjects responded to complicated grief therapy).10 It is therefore not surprising that IPT was effective in preventing PCBD in this sample as unresolved grief is one of the four standard foci in IPT.

Complicated grief therapy is designed to treat PCBD when it is already established—although, by the time it is diagnosed, several years or even decades may have passed since the actual loss, making the grief a chronic condition at that point. Our study was limited to grievers whose loss occurred within the prior 9 months such that the intended effect of study participation would be to prevent acute grief from evolving into a chronic state of PCBD with early intervention.

Experience gleaned from participation with the Good Grief Center in Pittsburgh taught us that many grievers will admit that the grieving process is novel for them and they call or visit stating they don’t understand what is happening to them and ask whether their grieving is normal or not. The results of this study support the concept that simply assigning a trained peer supporter to engage grievers regularly during the first year of their loss to provide empathic listening, education about common aspects of grieving, and gentle encouragement to take care of their own health needs may turn out to be a highly effective approach to preventing PCBD. This deserves more study with a larger sample.

The two-tiered design is also one that is parsimonious by design, only offering professional treatment to those who need it and peer support for everyone else. Engaging PCPs is critical—the PCP offers participation for their patients and informs them of the study purpose, and we can enlist their help to ascertain the need for any psychotropic medication as well as collaborating with them to take responsibility for triage to any higher level of needed care. This provided another safety net for subjects in this protocol. This two-tiered approach may also be a model that could be utilized for providing bereavement support for subjects in a wide geographic area solely by telephone or secure video-link contact that could be offered from a hub to a much larger geographic region. Onsite psychiatric consultation from a consulting psychiatrist expert in treating bereavement-related complications would also be ideal, as was in place for PCPs in this protocol (although no such requests were made during this study).

We acknowledge but make no attribution to the effect of psychotropic medication in this study other than to say that all subjects kept their doses of antidepressant medication constant throughout the study, as requested. Obviously, combined treatment with psychotropic medication may be needed in addition to peer support or IPT, particularly for those with prior histories of MDD or PCBD regarding prior deaths.

Lastly, it should be acknowledged that recruitment and retainment of subjects for a clinical program modeled after this protocol will undoubtedly be less successful outside of a research setting unless considerable effort is expended to create and maintain an organizational infrastructure. It is not feasible or desirable to train and recruit peer supporters for every griever, anticipating that only 30% on average will develop MDD or PCBD. The most practical implementation of a program such as this may be to let individuals self identify their need for help with grieving by advertising its availability or to rely on PCP referrals.

Highlights.

This manuscript illustrates that grieving individuals can be recruited, assigned, and retained in a peer support model intended to prevent complications of grieving in the first year post-loss.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution to this project from the Good Grief Center Peer Supporters with Dianna Hardy (GGC coordinator), Mary McShea (study coordinator); independent evaluators: Kelley Wood and Alexis Hoyt; IPT therapists: Mike Lockovich, Terry Means, and Kevin Rico; and statistical assistance from Amy Begley and Jun Zhang.

Footnotes

NOTICE WARNING CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS

The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgement, fullfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. No further reproduction and distribution of this copy is permitted by transmission or any other means.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Fifth. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ZiSook S, Shear K. Grief and bereavement: what psychiatrists need to know. World Psychiatry. 2009;8:67–74. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00217.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prigerson H, Frank E, Kasl S, et al. Complicated grief and bereavement-related depression as distinct disorders: preliminary empirical validation in elderly bereaved spouses. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:22–30. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynolds CF, Miller MD, Pasternak RE, et al. Treatment of bereavement-related major depressive episodes in later life: a controlled study of acute and continuation treatment with nortriptyline and interpersonal psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:202–208. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Pedrelli P, et al. Bupropion sustained release for bereavement: results of an open trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;62:227–230. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zygmont M, Prigerson HG, Houck PR, et al. A post hoc comparison of paroxetine and nortriptyline for symptoms of traumatic grief. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:241–245. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasternak RE, Reynolds CF, Schlernitzauer M, et al. Acute open-trial nortriptyline therapy of bereavement-related depression in late life. J Clin Psychiatry. 1991;52:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shear MK, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Simon NM, et al. Optimizing treatment of complicated grief: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:685–694. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peri T, Hasson-Ohayon I, Garber S, et al. Narrative reconstruction therapy. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016;7:30687. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.30687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, et al. Treatment of complicated grief: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2601–2608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.21.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doering BK, Eisma MC. Treatment for complicated grief: state of the science and ways forward. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29:286–291. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wetherell JL. Complicated grief therapy as a new treatment approach. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14:159–166. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.2/jwetherell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litz BT, Schorr Y, Delaney E. A randomized controlled trial of an Internet-based therapist-assisted indicated preventive intervention for prolonged grief disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2004;61:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissman MM, Markowitz JC, Klerman GL. Comprehensive Guide to Interpersonal Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Basic Books; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995;59:65–79. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Likert R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140:1–55. [Google Scholar]