Abstract

Objectives

Out-of-hours (OOH) primary care services are a key element of community care at the end of life, yet there have been no previous attempts to describe the scope of this activity. We aimed to establish the proportion of Oxfordshire patients who were seen by the OOH service within the last 30 days of life, whether they were documented in a palliative phase of care and the demographic and clinical features of these groups.

Design

Population-based study linking a database of patient contacts with OOH primary care with the register of all deaths within Oxfordshire (600 000 population) during 13 months.

Setting

Oxfordshire.

Participants

Between 1 December 2014 and 30 November 2015 there were 102 877 OOH contacts made by 67 943 patients with the OOH service.

Main outcome measures

Proportion of patients dying in the Oxfordshire population who were seen by the OOH service within the last 30 days of life. Demographic and clinical features of these contacts.

Results

29.5% of all population deaths were seen by the OOH service in the last 30 days of life. Among the 1530 patients seen, patients whose palliative phase was documented (n=577, 36.4%) were slightly younger (median age=83.5 vs 85.2 years, P<0.001) and were seen closer to death (median days to death=2 vs 8, P<0.001). More were assessed at home (59.8% vs 51.9%, P<0.001) and less were admitted to hospital (2.7% vs 18.0%, P<0.001).

Conclusions

OOH services see around one-third of all patients who die in a population. Most patients at the end of life are not documented as palliative by OOH services and are less likely to receive ongoing care at home.

Keywords: primary care, palliative care, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to use data linkage with death records to describe the true population at the end of life who contact the out-of-hours (OOH) service.

The study highlights both the importance of the OOH primary care service in end of life care and the significant limitations of medical records studies which have used clinical coding of palliative care as a proxy for end of life contacts.

Our understanding of the proportion of these deaths which were palliative and the causes of death relied on the accuracy of clinical coding.

Our study focused on a single area of the UK due to restriction in access to OOH provider medical records.

Introduction

The provision of primary care services outside core contracted hours is fundamental to the operation of the National Health Service (NHS).1 In 2013–2014, out-of-hours (OOH) general practitioner (GP) services in England handled approximately 5.8 million cases, 3.3 million of which were face-to-face consultations, including 800 000 home visits.2 For the majority of patients, OOH primary care is provided by a clinician who does not know them, often with limited access to their medical record.3

In January 2015, the top research priority identified by the palliative and end of life care priority setting partnership was the provision of palliative care outside of working hours to help patients stay in their place of choice by managing crises.4 Given that the majority of people in the UK with terminal illness do not wish to die in a hospital,5 OOH primary care services must be viewed as an integral part of end of life care provision.

Our current understanding of the true extent of end of life care provided by the OOH service is limited. OOH services do not routinely receive feedback on patient deaths following contact with the service. We previously analysed an OOH service database6 and learnt that patients whose needs were coded as palliative contacted the OOH service predominantly during weekend daytime periods, and that over a third had multiple contacts with the service. However, the study was limited because we were not able to identify all patients who had died and had contacted the service, thus underestimating the true proportion of patients with end of life care needs.

In order to understand how OOH care can best be provided at the end of life, we need to understand the true extent of this workload and whether there are differences between patients who appear to be recognised as palliative by clinicians and those who are not. This study used data linkage to identify people who died in Oxfordshire over the course of a year who had contact with the OOH services in the 30 days before death and the clinical care that they received from the OOH service.

Methods

The Oxfordshire OOH service provides care to a population of over 600 000 people from 18:30 hours to 08:00 hours on weekdays and 24 hour cover on weekends and bank holidays. Access to the service is via the NHS 111 telephone advice line, where trained call handlers use the NHS pathways algorithm to direct patients to the most appropriate service for their needs. Patients directed by 111 to the OOH service will receive an initial telephone consultation with an OOH clinician, which may then lead to a base visit (patient comes to the OOH surgery to be seen), home visit or the case being passed to another care provider (such as ‘hospital at home’). Patients can also be booked directly by 111 to an OOH base visit.

A database of all patient contacts with the Oxfordshire OOH service over 1 year from 1 December 2014 to 30 November 2015 was created from the OOH Electronic Record System used by clinicians (Adastra).

Mortality data for Oxfordshire (population 600 000) over 13 months (1 December 2014 to 31 December 2015, to capture patients who died within 30 days of contact with the OOH service) was obtained via NHS Digital/Office of National Statistics, with Section 251 approval from the Confidentiality Advisory Group. This was linked by NHS number with Oxfordshire OOH service care records and was used to identify people who had contact with the OOH service in the 30 days prior to death. All patient identifiers were removed on entry to the database and data destruction was completed in accordance with NHS Digital requirements. Any contact without an NHS number was removed from the database, as repeat visits could not be assessed, as were those with a duplicate case ID. Contacts that were seen after death were also removed. Demographic data consisted of age, sex and Index of Multiple Deprivation score (available for 79% of contacts).7 Service data included final contact type, outcome, date, clinical codes assigned and prescriptions issued. Mortality data included the date of death and all assigned ICD-108 causes of death. All assigned causes of death were included in the analysis in recognition of the fact that the most important or relevant cause of death may not be the first one listed on the certificate and therefore including only one cause would introduce significant bias.

Timings of calls were classified as evening 18:30–23:59 hours, overnight 00:00–07:59 hours and daytime (ie, weekends and bank holidays) 08:00–18:29 hours. The number of days difference between contact and death was calculated using calendar days beginning at midnight. Weekend period was classified as 18:30 hours Friday until 08:00 hours Monday.

Those who died were also classified according to whether they had been documented by the service as palliative or not. We defined palliative patients as those who, at any contact with the OOH service in the study period, had been assigned a clinical code specific to palliative care, been referred to a hospice as a result of an OOH contact or been prescribed an appropriate subcutaneous medication. The clinical codes specific to palliative care were: ZV57C [V]Palliative care, 1Z0 Terminal illness, and 8BA2 Terminal Care.

Appropriate subcutaneous medications were defined as medications as specified in the British National Formulary as being suitable for continuous subcutaneous infusion in palliative care. These included medications used for bowel colic and excessive respiratory secretions, confusion and restlessness, convulsions, nausea and vomiting and/or pain control.9 This group was compared with all other patients who died within 30 days of contact. Further details regarding coding are supplied as supplementary information.

Validation

In order to validate the clinical codes applied by the OOH clinicians, we estimated, based on previous coding validity studies,10 that analysis of 230 records would be required to establish the coding validity with a confidence level of 90% and 5% margin of error. A random selection of 230 records was obtained using SPSS, and the clinical code was compared by two authors (SG, HH) to the conclusion drawn by the clinician in the medical notes. The positive predictive value (PPV) of the clinical code for medical diagnosis or conclusion was 92.6%.

Statistical analysis

Demographic details and details concerning the cause of death were compared at a patient level, so that each patient was only considered once in the analysis. By contrast, the OOH contact and outcome were compared at an OOH contact level. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS V.22. T tests were used when comparing means, z tests when comparing proportions and Mann-Witney U test when comparing medians. Logistic regression was performed to test associations for binary outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in this study.

Results

Between 1 December 2014 and 30 November 2015, 67 943 patients made 102 877 contacts, with the Oxfordshire OOH service. In the 13-month period between 1 December 2014 and 31 December 2015, 5193 people died in Oxfordshire. Of the people who died, 1530 (29.5%) had contact with the OOH service in the 30 days prior to their death. These patients made 2661 contacts with the OOH service in 30 days prior to their death, accounting for 2.57% of all contacts to the service over the 12-month study period. A further 791 contacts (with 752 patients) occurred after death, equating to 14.5% of all deaths and 0.76% of all contacts to the service. Contacts after death were excluded from further analyses.

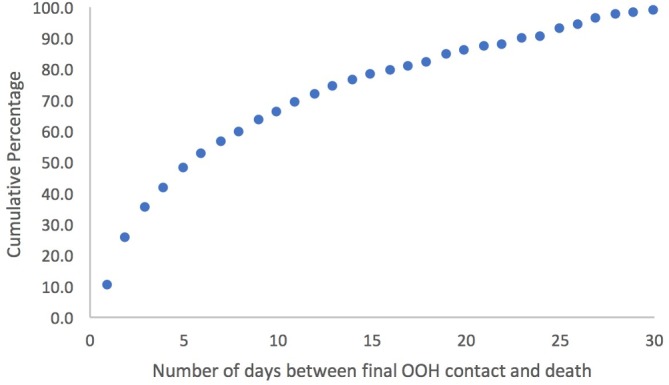

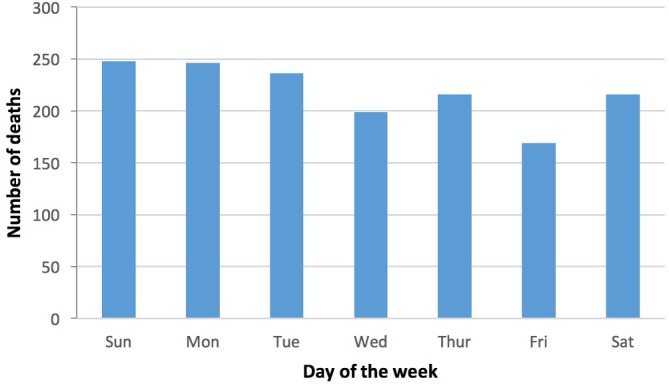

Of those patients who had contact with the OOH service in 30 days prior to death, 381 (24.9%) made a contact in the last day of life (figure 1). There was a median of 5 (IQR 1.75–13) days between final OOH contact and death and the median number of contacts with the OOH service in the 30 days prior to death was 1 (IQR 1–2). A similar proportion of deaths occurred on each day of the week (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Number of days between final out-of-hours (OOH) contact and death expressed as cumulative percentage.

Figure 2.

Number of deaths occurring on each day of the week.

Tables 1 and 2 compare patients and patient contact features of those who died within 30 days of death with those who were alive at 30 days after initial OOH consultation. Patients who died were older, less deprived and more likely to be male. Patient contacts were more frequently in their own home and more likely to have their care escalated to an alternative provider (hospital, hospice, community care provider).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients contacting the service within 30 days of death compared with all other patients

| Patients within 30 days of death (n=1530) | Patients not within 30 days of death (n=66 413) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 84.9 (77.0–90.6) years | 33.3 (12.2–59.2) years |

| Male (percentage, 95% CI) | 44.3% (41.8 to 46.8) | 41.6% (41.2 to 42.0) |

| IMD* score (mean, SD) | 12.00 (9.30) | 13.13 (9.67) |

*Index of multiple deprivation.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patient contacts with the service within 30 days of death compared with all other contacts

| Contacts within 30 days of death (n=2661) | Contacts not within 30 days of death (n=100 216) | |

| Contact type (percentage (95% CI)) | ||

| Home visit | 55.8% (53.9 to 57.7) | 9.7% (9.5 to 9.9) |

| Base assessment | 4.2% (3.4 to 5.0) | 55.8% (55.5 to 56.1) |

| Telephone contact only | 39.9% (38.0 to 41.8) | 34.3% (34.0 to 34.6) |

| Time of contact (percentage (95% CI)) | ||

| Overnight 00:00–07:59 hours | 22.6% (21.0 to 24.2) | 15.5% (15.3 to 15.7) |

| Evening 18:30–23:59 hours | 29.4% (27.7 to 31.1) | 37.8% (37.5 to 38.1) |

| Daytime 08:00–18:29 hours | 48.0% (46.1 to 49.9) | 46.7% (46.4 to 47.0) |

| Outcome of the contact (percentage (95% CI)) | ||

| Acute admission (hospital, emergency department, ambulatory care unit) | 10.5% (9.3 to 11.7) | 7.43% (7.3 to 3.6) |

| Admission to hospice | 0.4% (0.1 to 0.6) | 0.03% (0.03 to 0.03) |

| Community input (hospital at home, community nursing, social services, minor injury unit, mental health team) | 7.4% (6.4 to 8.4) | 1.2% (1.1 to 1.3) |

| Did not attend/unable to contact/left before treatment | 0.3% (0.1 to 0.6) | 1.4% (1.3 to 1.5) |

| GP follow-up | 38.2% (36.3 to 40.0) | 36.8% (36.5 to 37.1) |

| No follow-up | 38.3% (36.3 to 40.0) | 49.3% (49.0 to 49.6) |

| Other | 5.1% (4.3 to 5.9) | 3.8% (3.7 to 4.0) |

For those patients who died within 30 days the most commonly assigned clinical codes were palliative (27.3% of all codes assigned), advice (8.8%), medication requests (7.1%), lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) (5.5%) or urinary tract infection (UTI) (4.2%) codes. By comparison, ear, nose and throat disorder (13.5%), UTI (6.0%), musculoskeletal disease (MSK) (5.3%), upper respiratory tract infection (4.9%) and medication requests (4.2%) were the the most common codes in those alive at 30 days after index assessment (see online supplementary tables 1 and 2)

bmjopen-2017-020244supp001.pdf (231.9KB, pdf)

Acute events were the cause of death in 25% of patients. The the most common codes were types of cancer (45.6%) followed by cardiac disease (34.8%), LRTI (25.2%), dementia (23.9%), age-related debility and other respiratory disease (both 15.2%) (see table 3 for full list).

Table 3.

All assigned causes of death by documented palliative/not and total

| Documented as palliative | Not documented as palliative | Total | ||||

| Frequency | Percentage of patients | Frequency | Percentage of patients | Frequency | Percentage of patients | |

| Malignancy | 394 | 70.7 | 304 | 31.2 | 698 | 45.6 |

| Cardiac disease excluding myocardial infarction | 137 | 24.6 | 396 | 40.7 | 533 | 34.8 |

| Acute lower respiratory infection | 87 | 15.6 | 298 | 30.6 | 385 | 25.2 |

| Dementia | 121 | 21.7 | 244 | 25.1 | 365 | 23.9 |

| Age-related physical debility | 96 | 17.2 | 136 | 14.0 | 232 | 15.2 |

| Respiratory disease | 57 | 10.2 | 175 | 18.0 | 232 | 15.2 |

| Stroke (haemorrhage or infarction) | 56 | 10.1 | 124 | 12.7 | 180 | 11.8 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 20 | 3.6 | 128 | 13.2 | 148 | 9.7 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus without complications | 39 | 7.0 | 105 | 10.8 | 144 | 9.4 |

| Hypertension | 37 | 6.6 | 104 | 10.7 | 141 | 9.2 |

| Kidney disease | 40 | 7.2 | 99 | 10.2 | 139 | 9.1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 21 | 3.8 | 51 | 5.2 | 72 | 4.7 |

| Neurological disease | 21 | 3.8 | 44 | 4.5 | 65 | 4.2 |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 | 1.1 | 53 | 5.4 | 59 | 3.9 |

| Rheumatological disease | 20 | 3.6 | 39 | 4.0 | 59 | 3.9 |

| Other | 13 | 2.3 | 40 | 4.1 | 53 | 3.5 |

| Complication of procedure/surgery | 14 | 2.5 | 32 | 3.3 | 46 | 3.0 |

| Sepsis | 8 | 1.4 | 37 | 3.8 | 45 | 2.9 |

| Endocrinological disease | 6 | 1.1 | 35 | 3.6 | 41 | 2.7 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 12 | 2.2 | 28 | 2.9 | 40 | 2.6 |

| Acute kidney failure | 6 | 1.1 | 34 | 3.5 | 40 | 2.6 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 8 | 1.4 | 31 | 3.2 | 39 | 2.5 |

| Fracture | 14 | 2.5 | 25 | 2.6 | 39 | 2.5 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 6 | 1.1 | 24 | 2.5 | 30 | 2.0 |

| Infection (excluding LRTI and UTI) | 4 | 0.7 | 25 | 2.6 | 29 | 1.9 |

| Psychiatric | 6 | 1.1 | 14 | 1.4 | 20 | 1.3 |

| Non-malignant haematological | 4 | 0.7 | 12 | 1.2 | 16 | 1.0 |

| Traumatic | 2 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.6 | 8 | 0.5 |

| Fall | 2 | 0.4 | 2 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.3 |

| Drug related | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.3 |

Comparison between palliative patients and patients dying within 30 days not documented as palliative

Patients who had contact with the OOH service in the 30 days prior to death were categorised into those who had been documented by the service as palliative (any palliative code assigned to record, hospice referral or appropriate subcutaneous medication prescribed at any time), and those who had not.

Five hundred and fifty seven patients (36.4%) were documented as palliative, and had 1310 contacts with the OOH service in the 30 days prior to death. By contrast, 973 patients (63.6%) were not documented as palliative, accounting for 1351 contacts.

Patients documented as palliative were younger than those not documented (median 83.5 years (IQR 74.1–89.6) vs 85.2 years (IQR 78.3–91.1) (P<0.001, z=4.45), an association which was maintained after adjusting for sex and deprivation in multivariable logistic regression (OR 0.98, P<0.001, 95% CI 0.97 to 0.99).

There were clear differences in the patterns of service use, depending on documentation of palliative phase of care. Patients documented as palliative were seen more frequently in 30 days prior to death (median 3 contacts, IQR 2–4 vs median 2 contacts, IQR 1–3, z=−12.813, P<0.001), and their final contact with the service was closer to the point of death (median number of days between final contact and death (IQR 1–6), days vs 8 (IQR 3–17) days, z=−15.335 (P<0.001), with 42.2% (vs 15.1%) being seen on the day of death or day prior to death.

Patients documented as palliative presented less frequently at the weekend (67.2% vs 70.4%; z=−1.79, P=0.037), and more frequently overnight (27% vs 18.3%, z=5.391, P<0.001). They were more likely to be assessed at a home visit (59.8% vs 51.9%; z=4.094, P<0.001) and less likely to be managed solely through telephone contact (43.2% vs 36.6%, z=−3.508, P=0.002).

The two groups of patients differed in the outcomes of contacts with the OOH service. Patients documented as palliative were less likely to be admitted to hospital following their assessment (2.7% vs 18.0% respectively, z=−8.091, P<0.001), but more likely to be referred for community input (12.7% vs 2.3%, z=10.221, P<0.001) or require no further follow-up (40.8% vs 35.7%, z=2.7, P=0.0035) (table 4).

Table 4.

Outcomes of contacts with patients documented palliative vs those not documented palliative

| Outcome of contact | Documented as palliative | Not documented as palliative | ||

| Frequency | Percentage of contacts | Frequency | Percentage of contacts | |

| Acute admission (hospital, A&E, EMU) | 35 | 2.7% | 243 | 18.0% |

| Admission to hospice | 10 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Community input (H@H, comm nursing, SS, MIU) | 166 | 12.7% | 31 | 2.3% |

| Unable to contact | 2 | 0.2% | 7 | 0.5% |

| General practitioner follow-up | 493 | 37.6% | 522 | 38.6% |

| No follow-up | 534 | 40.8% | 482 | 35.7% |

| Other (OP clinic, passed to another provider) | 68 | 5.2% | 63 | 4.7% |

| Outcome missing | 2 | 0.2% | 3 | 0.2% |

| Total | 1310 | 100.0% | 1351 | 100.0% |

EMU, Emergency Multidsciplinary Unit; SS, social services; MIU, Minor Injuries Unit; OP, Out-patient.

In addition to palliative codes, the most common clinical codes assigned in those patients documented as palliative were medication related (7.4%), advice (6.35%), LRTI (2.8%), nausea and vomiting (2.0%) and catheter care (1.6%). In those patients not documented as palliative, a wider range of clinical codes were applied, the the most common were advice (10.8%), LRTI (8.4%), UTI (6.9%), medication related (6.2%) and shortness of breath (4.2%) (see online supplementary tables 3 and 4).

Causes of death in both groups are detailed in table 3. The highest proportion of deaths was due to malignancy in the group documented as palliative (70.7%); over twice that in those not documented as palliative (31.2%). There were similar proportions of patients with dementia as cause of death. Conversely, infections, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, gastroenterological and endocrinological diseases were over twice as frequently assigned to patients in the group not documented as palliative. Causes of death which would be considered acute events (acute kidney injury, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, fracture, fall, trauma, stroke and sepsis) were applied to 18.1% of patients documented as palliative and 29.3% of those not documented as palliative.

Discussion

OOH GP services provide end of life care to almost a third of people who die in a population, frequently very close to death. This places OOH GP services at the forefront of end of life care provision. Patients at the end of life are more likely to contact the service overnight, likely in part due to the reduction in availability of other services at these times. Death administration contributes significantly to the workload of the OOH service, being required for 14.5% of all deaths. Just 0.4% of all contacts occurring within the 30 days prior to death result in a hospice admission.

Only 36.4% of patients contacting the service at the end of life were documented as palliative, hence studies relying on clinical coding of patient contacts as palliative will significantly under-report the burden on the service. A large number of contacts in the 30 days prior to death result in a home visit irrespective of documentation of a palliative phase of care, reflecting significant frailty within this patient group. Patients not documented as palliative had a much higher rate of acute hospital admission, suggesting that initial management strategy is based on addressing an acute presenting illness syndrome with hospital-based care in this group.

The only study which has used a similar methodology to explore OOH service use at the end of life reported a similarly high proportion (25%) of deceased patients contacting a Norwegian OOH service in the 4 weeks before death, with a much higher proportion (37%) referred to hospital at their OOH contact.11

Strengths and limitations

This is the first study to accurately report the proportion of patients who die shortly after contact with OOH primary care by linking UK OOH records with mortality data. However, there are several limitations to our analysis. Our study is based on the English NHS, and we cannot comment on whether our results would extrapolate to other models of out of hours healthcare provision. By excluding deaths of patients living outside Oxfordshire we may have underestimated demands on the service. Our analysis was also limited to contacts within 30 days of death; however, the majority of contacts were within 7 days of death, suggesting that this has not significantly limited our conclusions.

In order to explore whether the service recognised the patient contact as palliative, we relied on OOH clinicians assigning a palliative code to the patients record or documenting an action only relevant to palliative care (prescribing subcutaneous medication or hospice referral). Since no other studies have attempted this form of classification, we could not use a validated approach. It is likely that some patients who were recognised by the service as needing end of life care may have been misclassified in this analysis. However, the PPV of the clinical code for medical diagnosis or conclusion was higher than the average PPV found in a systematic review of studies using primary care medical records.10 Similarly, we relied on the accuracy of cause of death as recorded by either the regular GP or hospital clinician. It is possible that acute events could be under-reported in death certificates if active malignancy is present.

Implications

The OOH service is making a significant contribution to end of life care. Despite a majority of patients with terminal illness wishing to die at home, only a minority currently achieve this.5 Enabling good deaths in the community is therefore a key component of OOH primary care provision. There is scope for debate on how best to provide a service to this patient group. One component of this must be improving planning and communication from the in hours GP to avoid OOH demands, and another might be the creation of dedicated palliative teams, operating in the OOH period. However, both of these measures will only support the third of patients at the end of life who are documented as palliative, and additional measures are needed to ensure that the OOH service is fit for managing all patients at the end of life, in terms of recognition of end of life, staff skill mix and resources.

Two-thirds of patients who died within 30 days of OOH contact were not documented as being in a palliative phase of care. There will be patients for whom an acute life-threatening syndrome has led to an OOH contact. The percentage of deaths which were due to acute events was 25% overall, in line with national estimates,12 and relatively higher in the group not documented as palliative (29.3%). In addition, clinicians may recognise patients to be at the end of life, but choose to use more immediately relevant clinical codes for the contact or be reluctant to use palliative codes for patients who do not have cancer. Furthermore, there may be patients at the end of life where it is simply not recognised in the setting of multiple morbidity and frailty.

A greater number of acute, gastrointestinal, infection and cardiac codes were applied to patients who were not documented as palliative. Gastrointestinal conditions in particular have been highlighted previously as challenging to diagnose in prehospital urgent care settings.13 14 Evolving OOH care services to include a greater range of point of care (POC) blood and imaging diagnostics and tailored risk scores could offer clinicians support in triaging and managing these difficult presentations.

Reviews of deaths are standard practice in acute trusts and are viewed as integral to learning and service improvement and in hours GPs are routinely informed of deaths of patients in their care. However, there is no routine mechanism to feedback to clinicians working in OOH services when deaths occur after contact. This deprives clinicians of the opportunity for valuable reflection and learning and services of the opportunity for improvement.15 It is particularly relevant in light of the recent Care Quality Commission call16 to end missed opportunities to learn from patient deaths. Following the Mazars report,17 there is an increased focus on more robust systems to learn from deaths of patients following contact with NHS trust services. This study may help OOH services prioritise deaths for mortality review to maximise learning.

Conclusion

The contribution of OOH primary care services to patients at the end of life has previously been under-researched and underestimated. This study demonstrates that almost a third of people who die have contact with an OOH service in the preceding 30 days. Further work to understand how OOH primary care can best meet the needs of patients at the end of life is required.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of Dr Ian Neale, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, with interpretation of our findings.

Footnotes

Contributors: GH and DL conceived the study. RF developed the protocol, gained study permissions and developed the databases. RB, DL and GH analysed the data. HH and SG validated the dataset. RB and GH drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to interpretation of results and critical revision of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Oxfordshire Health Services Research Committee (grant number 1176). GH holds an NIHR-funded Academic Clinical Lectureship, RF and RB were supported by NIHR Academic Clinical fellowships. DL was supported by the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health or the NHS.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study had Research Ethics approval (REC number 15/SC/0754) and Confidentiality Advisory Group approval (15/CAG/0211).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No further data are available.

References

- 1. Baker M, Thomas M, Mawby R. The future of GP out of hours care. 2014. http://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/~/media/Files/Policy/A-Z-policy/RCGP-The-Future-of-GP-Out-of-Hours-Care-2015.ashx

- 2. National Audit Office. Out of hours GP services in England (National Audit Office, London). 2014. http://www.nao.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Out-of-hours-GP-services-in-England1.pdf

- 3. Colin-Thomé D, Field S. General practice out-of-hours services: project to consider and assess current arrangements. 2010. http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/@ps/documents/digitalasset/dh_111893.pdf

- 4. Curie M. Palliative and end of life care Priority Setting Partnership. (PeolcPSP). 2015. https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/research/PeolcPSP_Final_Report.pdf

- 5. Higginson I. Priorities and preferences for end of life care in England, Wales and Scotland. London: National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher RF, Lasserson D, Hayward G. Out-of-hours primary care use at the end of life: a descriptive study. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e654–e660. 10.3399/bjgp16X686137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Communities and Local Government. The English indices of deprivation 2010: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research: World Health Organization, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Joint Formulary Committee. British national formulary. 74th edn London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khan NF, Harrison SE, Rose PW. Validity of diagnostic coding within the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:128–36. 10.3399/bjgp10X483562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kristoffersen JE. Out-of-hours primary care and the patients who die. A survey of deaths after contact with a suburban primary care out-of-hours service. Scand J Prim Health Care 2000;18:139–42. 10.1080/028134300453322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. National End of Life Care Intelligence Network. Predicting death: estimating the proportion of deaths that are unexpected. http://www.endoflifecare-intelligence.org.uk/resources/publications/predicting_death

- 13. Hayward GN, Vincent C, Lasserson DS. Predicting clinical deterioration after initial assessment in out-of-hours primary care: a retrospective service evaluation. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e78–e85. 10.3399/bjgp16X687961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rørtveit S, Meland E, Hunskaar S. Changes of triage by GPs during the course of prehospital emergency situations in a Norwegian rural community. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:89 10.1186/1757-7241-21-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hart JT, Humphreys C. Be your own coroner: an audit of 500 consecutive deaths in a general practice. Br Med J 1987;294:871–4. 10.1136/bmj.294.6576.871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Care Quality Commission. Learning, candour and accountability A review of the way NHS trusts review and investigate the deaths of patients in England. 2016. http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20161213-learning-candour-accountability-full-report.pdf

- 17. Independent review of deaths of people with a Learning Disability or Mental Health problem in contact with Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust April 2011 to March 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/south/wp-content/uploads/sites/6/2015/12/mazars-rep.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020244supp001.pdf (231.9KB, pdf)