Abstract

Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) is a species of the Rosaceae that was originated in Central Asia, from where it entered Europe through Armenia. The release of an increasing number of new cultivars from different breeding programs is resulting in an important renewal of plant material worldwide. Although most traditional apricot cultivars in Europe are self-compatible, the use of self-incompatible cultivars as parental genotypes for breeding purposes is leading to the introduction of a number of new cultivars that behave as self-incompatible. As a consequence, there is an increasing need to interplant those new cultivars with cross-compatible cultivars to ensure fruit set in commercial orchards. However, the pollination requirements of many of these new cultivars are unknown. In this work, we analyze the pollination requirements of a group of 92 apricot cultivars, including traditional and newly-released cultivars from different breeding programs and countries. Self-compatibility was established by the observation of pollen tube behavior in self-pollinated flowers under the microscope. Incompatibility relationships between cultivars were established by the identification of S-alleles by PCR analysis. The self-(in)compatibility of 68 cultivars and the S-RNase genotype of 74 cultivars are reported herein for the first time. Approximately half of the cultivars (47) behaved as self-compatible and the other 45 as self-incompatible. Identification of S-alleles in self-incompatible cultivars allowed allocating them in 11 incompatibility groups, six of them reported here for the first time. The determination of pollination requirements and the incompatibility relationships between cultivars is highly valuable for the appropriate selection of apricot cultivars in commercial orchards and of parental genotypes in breeding programs. The approach described can be transferred to other woody perennial crops with similar problems.

Keywords: Prunus armeniaca, self-incompatibility, S-alleles, S-genotype, ovary, pollen tube, pollination, style

Introduction

Apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) is considered as one of the most delicious temperate fruits (Faust et al., 1998). Apricot is a species of the Rosaceae, one of the most economically important plant families in temperate regions worldwide (Dirlewanger et al., 2004). Although the Latin name of apricot (armeniaca) and later its scientific name (P. armeniaca) could wrongly suggest an origin from Armenia, apricot was indeed originated in Central Asia, where the first orchards of apricot were described 406-250 BC (Janick, 2005), whereas Armenia was the route by which apricot first entered Europe. Apricot was already mentioned as Mela armeniaca by Roman authors around 50 A.D., which could indicate its introduction in the Roman empire during the first century (Faust et al., 1998). The English name apricot (apricock in the old spelling) derives from the Arabic and Greek term al-praecox that means “early fruit” (Faust et al., 1998; Janick, 2005). Traditionally, apricot cultivars have been classified in six main groups depending on the geographical origin: Dzhungar-Zailij, East Chinese, European Iranian-Caucasian, Middle-Asian, and North Chinese (Layne et al., 1996).

Apricot cultivars from the Central Asian, the Dzhungar-Zailij, and the Iranian-Caucasian groups are mostly self-incompatible. However, cultivars from the European group, which is the least variable and the most recent, are mainly self-compatible and include most of the commercial cultivars (Mehlenbacher et al., 1991; Hormaza et al., 2007). In the Rosaceae, the incompatibility mechanism to reduce self-fertilization and promote outcrossing is based on cell-cell recognition that is determined genetically by a gametophytic self-incompatibility System (GSI). This mechanism acts through the inhibition of pollen tube growth in the style (de Nettancourt, 2001) and is controlled by a multiallelic locus named S, encoding two linked genes that determine the pistil and pollen genotypes (Charlesworth et al., 2005). A ribonuclease (S-RNase), which is a glycoprotein secreted in the style mucilage, determines the allele specificity of the style (Tao et al., 1997) whereas an F-box protein (SFB) specifically expressed in pollen determines pollen allele specificity (Ushijima et al., 2003).

The introduction of an increasing number of new apricot cultivars from different breeding programs is resulting in an important renewal of plant material worldwide (Zhebentyayeva et al., 2012). Thus, the initial classification of six ecogeographical groups is becoming increasingly complex, since many of the new cultivars are derived from crosses between genotypes of different ecogeographical groups (Faust et al., 1998; Halász et al., 2007). Moreover, although most traditional apricot cultivars in Europe are self-compatible (Burgos et al., 1997), the use of self-incompatible cultivars developed in North America as parental genotypes in several breeding programs, with the objective of incorporating resistance to sharka (Hormaza et al., 2007; Zhebentyayeva et al., 2012), is leading to the introduction of new self-incompatible cultivars. As a consequence, there is an increasing need to interplant those new cultivars with cross-compatible cultivars to ensure fruit set in commercial orchards. However, the pollination requirements of many of these new cultivars are unknown.

The pollination requirements of a cultivar can be established by carrying out controlled pollinations in the field and recording the percentage of fruit set. Final fruit set in apricot is usually established during the first 4 weeks following pollination (Rodrigo et al., 2009; Julian et al., 2010). However, incompatibility can be determined more accurately under a fluorescence microscope by the observation of pollen tube growth through the style in self- and cross-pollinated flowers in squash preparations of pistils after staining with aniline blue (Burgos et al., 1993; Rodrigo and Herrero, 1996, 2002; Julian et al., 2010). In self-incompatible genotypes and incompatible crosses, pollen tube growth is arrested in the style and, therefore, fertilization of the ovules is prevented since no pollen tubes reach the ovary. However, in self-compatible genotypes and compatible crosses, pollen tubes can grow along the style and reach the ovary, where fertilization of some of the two ovules can take place. This histochemical approach allows the identification of pollination failure from diverse environmental factors that can affect fruit set under field conditions (Guerra and Rodrigo, 2015).

In addition, advances in the study of the molecular determinants of self-incompatibility have allowed developing tools to analyze the allelic composition of the self-incompatibility locus. Thus, the identification of the S-RNase gene in apricot (Romero et al., 2004; Sutherland et al., 2004) allowed developing an S-allele genotyping PCR strategy, similar to those developed for cherry or almond (Sutherland et al., 2004). To date, 33 S-alleles (S1 to S20, S22 to S30, S52, S53, Sv, and Sx), including one allele for self-compatibility (Sc), have been identified in apricot (Halász et al., 2005; Vilanova et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008; Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017; Murathan et al., 2017), although additional alleles have been included in the NCBI database and not yet published. These studies allowed the determination of different apricot S-genotypes from different countries (Halász et al., 2010; Kodad et al., 2013a,b; Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017) that are included in, up to now, 17 incompatibility groups (Szabó and Nyéki, 1991; Egea and Burgos, 1996; Halász et al., 2010; Lachkar et al., 2013).

Due to the increasing release of a high number of apricot cultivars in the last years with unknown self-incompatibility genotypes, in this work we analyze the pollination requirements of a group of 92 apricot cultivars, including traditional and new cultivars released from different breeding programs. Self-compatibility was established by the observation of pollen tube behavior under the microscope following self-pollination. Incompatibility relationships between cultivars were established by the identification of S-alleles by PCR analysis. The results obtained allowed assigning each cultivar to its corresponding incompatibility group.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Leaf and flower samples from 92 apricot cultivars, including traditional cultivars from different origins and new cultivars from different breeding programs (Table 1), were collected from diverse collections for pollination experiments and S-RNase genotyping.

Table 1.

Country of origin, number of pistils examined, percentage of pistils with pollen tubes halfway the style, at the base of the style, and reaching the ovule, percentage of style traveled by the longest pollen tube, mean number of pollen tubes at the base of the style, and self-incompatibility (SI) or self-compatibility (SC) of 92 apricot cultivars analyzed in this work.

| Cultivar | Country of origin | Number of pistils examined | Pistils (%) with pollen tubes | Percentage of style traveled by the longest pollen tube | Mean number of pollen tubes at the base of the style | SI/SC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halfway the style | At the base of the style | Reaching the ovule | ||||||

| AC1 | USA | 13 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 82 | 0 | SI |

| ASF0401 | France | 17 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | SI |

| ASF0402 | France | 24 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | SI |

| Avirine (Bergarouge) | France | 13 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 0 | SI |

| CA-26 (Almater) | Spain | 20 | 100 | 5 | 5 | 70 | 0 | SI |

| Colorado | Spain | 30 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 0 | SI |

| Cooper Cot | USA | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | SI |

| Durobar (Almadulce) | Spain | 23 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 67 | 0 | SI |

| Farely | France | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0 | SI |

| Feria Cot | France | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 78 | 0 | SI |

| Flash Cot | USA | 10 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 54 | 0 | SI |

| Flodea | Spain | 11 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 0 | SI |

| Goldbar | USA | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 0 | SI |

| Goldrich | USA | 72 | 94 | 3 | 3 | 69 | 0 | SI |

| Goldstrike 01a | USA | 40 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 0 | SI |

| Goldstrike 02a | USA | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 0 | SI |

| Harcot | Canada | 44 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 0 | SI |

| Hargrand | Canada | 49 | 100 | 14 | 14 | 77 | 0 | SI |

| Henderson | USA | 47 | 91 | 15 | 9 | 75 | 0 | SI |

| Holly Cot | France | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 0 | SI |

| JNP | Spain | 20 | 100 | 5 | 5 | 75 | 0 | SI |

| Lilly Cot | USA | 47 | 96 | 2 | 0 | 67 | 0 | SI |

| Magic Cot | USA | 30 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | SI |

| Maya Cot | France | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 0 | SI |

| Medaga | France | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 71 | 0 | SI |

| Megatea | Spain | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 62 | 0 | SI |

| Moniqui | Spain | 18 | 100 | 6 | 0 | 79 | 0 | SI |

| Monster Cot | USA | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 0 | SI |

| Muñoz | Spain | 21 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 72 | 0 | SI |

| Orangered | USA | 10 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 64 | 0 | SI |

| Pandora | Greece | 23 | 100 | 4 | 0 | 75 | 0 | SI |

| Peñaflor 01a | Spain | 29 | 100 | 7 | 7 | 71 | 0 | SI |

| Perle Cot | USA | 28 | 93 | 4 | 0 | 72 | 0 | SI |

| Pinkcot | France | 34 | 97 | 9 | 0 | 83 | 0 | SI |

| Priabel | France | 10 | 90 | 10 | 0 | 81 | 0 | SI |

| Robada | USA | 25 | 96 | 0 | 0 | 63 | 0 | SI |

| Spring Blush | France | 40 | 83 | 3 | 3 | 55 | 0 | SI |

| Stark Early Orange | USA | 51 | 98 | 33 | 16 | 87 | 0 | SI |

| Stella | USA | 13 | 100 | 23 | 15 | 85 | 0 | SI |

| Sun Glo | USA | 64 | 100 | 2 | 0 | 71 | 0 | SI |

| Sunny Cot | USA | 10 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 65 | 0 | SI |

| Sweet Cot | USA | 20 | 95 | 0 | 0 | 66 | 0 | SI |

| Vanilla Cot | USA | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 79 | 0 | SI |

| Veecot | Canada | 29 | 100 | 3 | 3 | 74 | 0 | SI |

| Wonder Cot | USA | 37 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 69 | 0 | SI |

| AC2 | USA | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2.2 | SC |

| Aprix 20 | Spain | 15 | 100 | 73 | 53 | 100 | 1.4 | SC |

| Aprix 33 | Spain | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.1 | SC |

| Aprix 9 | Spain | 14 | 100 | 86 | 64 | 100 | 2.1 | SC |

| ASF0404 (Apriqueen) | France | 22 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Berdejo | Spain | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.9 | SC |

| Bergecot | France | 20 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 2.5 | SC |

| Canino | Spain | 29 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 2.0 | SC |

| Charisma | South Africa | 23 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Corbato | Spain | 60 | 100 | 98 | 93 | 100 | 3.2 | SC |

| Delice Cot | France | 15 | 100 | 87 | 53 | 100 | 1.1 | SC |

| Faralia | France | 11 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Farbaly | France | 22 | 100 | 86 | 77 | 100 | 2.0 | SC |

| Farbela | France | 6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.8 | SC |

| Farclo | France | 9 | 100 | 100 | 89 | 100 | 1.4 | SC |

| Fardao | France | 9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 4.1 | SC |

| Farfia | France | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Farhial | France | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Farius | France | 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Farlis | France | 22 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Fartoli | France | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Flopria | Spain | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Golden Sweet | USA | 21 | 100 | 95 | 95 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Lady Cot | France | 26 | 100 | 77 | 77 | 100 | 2.3 | SC |

| Lorna | USA | 17 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Luizet | France | 10 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 100 | 1 | SC |

| Medflo | France | 8 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.9 | SC |

| Mediabel | France | 12 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.2 | SC |

| Mediva | France | 9 | 100 | 89 | 89 | 100 | 2.3 | SC |

| Mirlo Anaranjado | Spain | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2.1 | SC |

| Mirlo Blanco | Spain | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Mitger | Spain | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2.4 | SC |

| Palsteyn | South Africa | 30 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Paviot | France | 12 | 100 | 91 | 91 | 100 | 1.2 | SC |

| Peñaflor 02a | Spain | 6 | 100 | 83.3 | 66.6 | 100 | 1.4 | SC |

| Pepito del Rubio | Spain | 12 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 2.2 | SC |

| Playa Cot | France | 10 | 100 | 100 | 70 | 100 | 1.7 | SC |

| Pricia | France | 9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Primidi | France | 9 | 89 | 78 | 78 | 100 | 2 | SC |

| Rouge Cot | France | 10 | 100 | 90 | 70 | 100 | 1.55 | SC |

| Rubista | France | 19 | 95 | 89 | 89 | 100 | 1.7 | SC |

| Sandy Cot | France | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 2.3 | SC |

| Soledane | France | 21 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Swired | Switzerland | 9 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 100 | 1.8 | SC |

| Tadeo | Spain | 36 | 100 | 97 | 97 | 100 | 2.4 | SC |

| Tom Cot | USA | 10 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 3 | SC |

| Victor 1 | 14 | 100 | 93 | 93 | 100 | 2.1 | SC | |

Diverse origin.

Pollination experiments

To explore self-(in)compatibility, self-pollinations of the 92 apricot cultivars were carried out in the laboratory. Pollen tube growth was observed in self-pollinated flowers under the microscope (Table 1). As control, a group of flowers of each cultivar were cross-pollinated with pollen from “Canino” or “Katy,” which are considered as universal pollinizers for apricot (Zuriaga et al., 2013).

Pollen was extracted from flowers collected at the balloon stage. For this purpose, the anthers were removed and dried at laboratory temperature during 24 h. After that, pollen grains were sieved by using a fine mesh (0.26 mm) and used immediately or frozen at −20°C until further use. Pistils were obtained from flowers collected 1 day before anthesis, at balloon stage. After the removing of petals, sepals and stamens, the pistils were maintained on wet florist foam at laboratory temperature (Rodrigo and Herrero, 1996). For each self- and cross-pollination, a group of 20–25 flowers were hand pollinated with the help of a paintbrush 24 h after emasculation. After 72 h, they were fixed in ethanol (95%)/acetic acid (3:1, v/v) during 24 h, and conserved at 4°C in 75% ethanol (Williams et al., 1999). When observations of pollen tube growth were not clear, each cross was repeated every year during the flowering period up to 4 years. In order to evaluate pollen viability, after hand pollination, pollen from each cultivar was scattered on a solidified pollen germination medium (Hormaza et al., 1996). After 24 h, preparations were observed under the microscope. Pollen grains were considered viable when the length of the growing pollen tubes was higher than the pollen grain diameter.

For histochemical preparations, the pistils were washed three times for 1 h with distilled water and left in 5% sodium sulphite at 4°C for 24 h. Then, to soften the tissues, they were autoclaved at 1 kg/cm2 during 10 min in sodium sulphite (Jefferies and Belcher, 1974). To stain callose, the softened pistils, were stained with 0.1% (v/v) aniline blue in 0.1 N K3PO4 (Linskens and Esser, 1957). The observation of pollen tube behavior along the style was performed by a Leica DM2500 microscope (Cambridge, UK) with UV epifluorescence using 340–380 bandpass and 425 longpass filters. The percentage of style traveled by the longest pollen tube and the mean number of pollen tubes at the base of the style were recorded on at least 10 pistils in each cross. Cultivars were considered as self-incompatible when pollen tube growth was arrested in the style in most pistils from self-pollinated flowers, and as self-compatible when more than half of the pistils displayed at least one pollen tube reaching the base of the style.

DNA extraction

For the identification of S-alleles, young leaves were collected in spring. Genomic DNA from 92 cultivars (Table 2) was isolated following the protocol described by Hormaza (2002) and using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). NanoDrop™ ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Bio-Science, Budapest, Hungary) was used to measure DNA concentrations to analyze the quantity and quality of DNA.

Table 2.

Incompatibility group (I.G.) and S-RNase genotype of 92 apricot cultivars analyzed in this study and 30 additional cultivars analyzed in previous studies.

| I.G. | S-RNase genotype | Cultivars analyzed in this study | Cultivars analyzed in previous studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | S1S2 | AC1x | ||

| Hargrand | 2, 5, 14 | |||

| Katy | 13, 14 | |||

| Goldrich | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 13, 14 | |||

| Castleton | 14 | |||

| Farmingdale | 9 | |||

| Giovanniello | 9 | |||

| Lambertin-1 | 2, 14 | |||

| II | S8S9 | Pinkcotx | ||

| Perle Cotx | ||||

| Ceglédi óriás | 5, 8 | |||

| Cologlu | 12 | |||

| Kadioglu | 12 | |||

| Ligeti óriás | 5, 8 | |||

| Seftalioglu | 12 | |||

| Szegedi M. | 14 | |||

| III | S2S6 | ASF0401x | ||

| Avirine (Bergarouge)x | ||||

| Moniqui | 2, 6, 14 | |||

| Iri Bitirgen | 12 | |||

| V | S2S8 | Holly Cotx | ||

| Sweet Cotx | ||||

| Alyanak | 12 | |||

| Ziraat Okulu | 12 | |||

| VIII | S6S9 | Orangeredw | 14 | |

| ASF0402x | ||||

| Wonder Cotx | ||||

| Stark Early Orangew | 14 | |||

| Feria Cotx | ||||

| Sunny Cotx | ||||

| JNPx | ||||

| Cataloglu | 12 | |||

| Ozal | 12 | |||

| Soganci | 12 | |||

| XVIIIz | S1S3 | Cooper Cotx | ||

| Perfection | 1 | |||

| XIXz | S2S3 | Mayacotx | ||

| Sun Glo | 2, 3, 4, 6 | |||

| XXz | S2S9 | Magic Cotx | ||

| Goldstrike 02v,x | ||||

| Hasanbey | 12 | |||

| XXIz | S3S8 | Spring Blushx | ||

| Lilly Cotx | ||||

| Kayseri P.A | 12 | |||

| XXIIz | S3S9 | Durobar (Almadulce)x | ||

| Hendersonw | 14 | |||

| Flodeax | ||||

| Akcadag Günay | 12 | |||

| XXIIIz | S7S9 | Goldbarx | ||

| Kurukabuk | 12 | |||

| S2 | Pandorax | |||

| Veecot | ||||

| Muñozx | ||||

| Peñaflor 01v, x | ||||

| Hardgrand | ||||

| Goldrich | ||||

| Búlida | 9 | |||

| Lornay | 9 | |||

| Perla | 9 | |||

| S3 | Coloradoy | |||

| Ninfa | 9 | |||

| S4 | Harcot | |||

| S6 | Stella | |||

| S8 | Vanilla Cotx | |||

| Robadax | ||||

| Katy | 7 | |||

| Krimskyi Medunec | 5 | |||

| S9 | Flash Cotx | |||

| Goldstrike 01v,x | ||||

| CA-26 (Almater) x | ||||

| Farelyx | ||||

| Medagax | ||||

| Megateax | ||||

| Monster Cotx | ||||

| Priabelx | ||||

| Self-compatible cultivars | S2Sc | Berdejox | ||

| Canino | 3, 10, 13 | |||

| Paviotx | ||||

| Pepito del Rubio | 2, 3 | |||

| Peñaflor 02v,x | ||||

| Bergecotx | ||||

| Medivax | ||||

| Primidix | ||||

| Sandy Cotx | ||||

| S3Sc | Priciax | |||

| Rubistax | ||||

| S6Sc | Aprix 20x | |||

| Aprix 9x | ||||

| Faraliax | ||||

| Farlisx | ||||

| Medflox | ||||

| Mediabelx | ||||

| S7Sc | Charismax | |||

| S9Sc | AC2x | |||

| Flopriax | ||||

| Tom Cotx | ||||

| Sc | Soledanex | |||

| ASF0404 (Apriqueen)x | ||||

| Mirlo Blanco | 11 | |||

| Mitger | ||||

| Tadeo | ||||

| Corbatoy | ||||

| Aprix 33x | ||||

| Delice Cotx | ||||

| Farbalyx | ||||

| Farbelax | ||||

| Farclox | ||||

| Fardaox | ||||

| Farfiax | ||||

| Farhialx | ||||

| Fariusx | ||||

| Fartolix | ||||

| Lady Cotx | ||||

| Mirlo Anaranjado | ||||

| Luizetx | ||||

| Playa Cotx | ||||

| Swiredx | ||||

| Rouge Cotx | ||||

| S1S2 | Lornax,y | |||

| Palsteynx,y | ||||

| S2S9 | Victor 1x | |||

| S3 | Golden Sweetx |

(1) Egea and Burgos (1996); (2) Burgos et al. (1998); (3) Alburquerque et al. (2002); (4) Sutherland et al. (2004); (5) Halász et al. (2005); (6) Vilanova et al. (2005); (7) Chen et al. (2006); (8) Halász et al. (2007); (9) Donoso et al. (2009); (10) Raz et al. (2009); (11) Egea et al. (2010); (12) Halász et al. (2010); (13) Zuriaga et al. (2013); (14) Muñoz-Sanz et al. (2017).

Diverse origin.

S9 and S17 have been considered the same allele.

S-RNase genotypes first reported in this study.

Cultivars in which S-RNase genotype reported herein differs from that reported in other studies.

Incompatibility groups first reported in this study.

S-RNase allele identification by PCR analysis

Amplification reactions for the first intron region of the S-RNase gene were carried out with the combination of the fluorescently labeled forward primer SRc-F (5′-CTCGCTTTCCTTGTTCTTGC-3′) with the reverse primer SRc-R (5′-GGCCATTGTTGCACAAATTG-3′; Romero et al., 2004; Vilanova et al., 2005). PCR amplifications were carried out in 15 μl reaction volumes, containing 10x NH4 Reaction Buffer, 25 mM Cl2Mg, 2.5 mM of each dNTP, 10 μM of each primer, 100 ng of genomic DNA and 0.5 U of BioTaq™ DNA polymerase (Bioline, London, UK). The temperature profile used had an initial step of 3 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 55°C and 3 min at 72°C, and a final step of 5 min at 72°C.

The sizes of the products obtained by PCR were analyzed in a CEQ™ 8000 capillary electrophoresis DNA analysis system (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA) and compared and classified according to Vilanova et al. (2005) and Kodad et al. (2013b). Primers Pru-C2 (5′-CTTTGGCCAAGTAATTATTCAAACC-3′) and Pru-C4R (5′-GGATGTGGTACGATTGAAGCG-3′) were used for the amplification of the second intron region as recommended by Vilanova et al. (2005), but with the addition of 10 cycles and using 55°C of annealing temperature as indicated by Sonneveld et al. (2003). Amplified fragments of the second intron were separated on 1% (w/v) agarose gels and DNA bands were visualized using the nucleic acid stain SYBR Green (Thermo).

Sequencing of genomic PCR products

Two PCR fragments of 420 and 430 bp obtained by the automatic sequencer were isolated using the NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel). Cloning was performed using CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo) and by electroporation in E. coli Single-Use JM109 Competent Cells (Promega). The search for similarities in the sequences of the NCBI database was performed with BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST, version 2.2.10). The 420 bp fragment resulted in a fragment of 414 bp after one sequencing reaction whereas the initial 430 bp fragment resulted in a fragment of 421 bp after two sequencing reactions.

Results

Pollination experiments

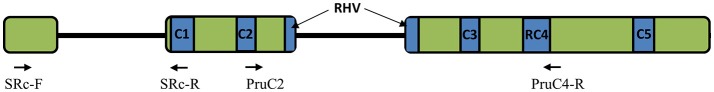

Self-compatibility of 92 apricot cultivars was established by the observation of pollen tube behavior in pistils under the microscope after self-pollinations (Table 1). Germinated pollen grains were observed in the stigma (Figure 1A) in all the pollinations performed. The establishment of self-incompatibility or self-compatibility could be carried out for all the cultivars. Approximately half of the cultivars (47) behaved as self-compatible, displaying most pistils with pollen tubes growing along the style (Figure 1B) and at least one pollen tube reaching the base of the style (Figure 1C). On the other hand, in 45 cultivars pollen tubes arrested their growth in the style (Figure 1D) and no pollen tubes reached the base of the style in most of the pistils. Consequently, these cultivars were considered as self-incompatible. As expected, in all cross-pollinations pistils displayed pollen tubes at the base of the style. Between one and four pollen tubes at the base of the style were observed in self-compatible cultivars.

Figure 1.

Pollen tube growth in self-pollinated apricot flowers. (A) Pollen grains germinating at the stigma surface. (B) Pollen tubes growing along the style. (C) Pollen tubes reaching the base of the style. (D) Pollen tube arrested in the style. Scale bars, 100 μm.

S-RNase allele PCR analysis

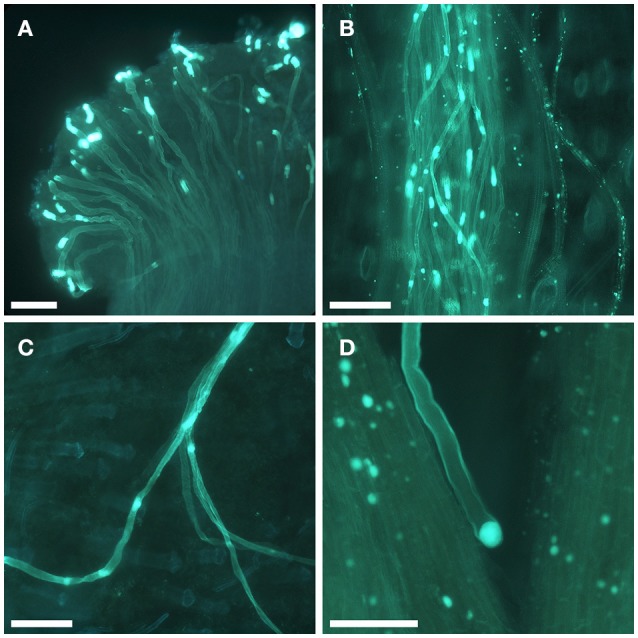

To confirm the results obtained in the pollination experiments, PCR analyses using specific primers from conserved regions of the apricot S-RNase locus were used to identify the S-RNase alleles of 92 apricot cultivars (Table 2). The information reported herein has been compiled with the S-RNase genotype of 30 additional cultivars previously determined showing the compatibility relationships among all the cultivars whose S-RNase genotype is known (Table 2). Cultivars have been allocated according their S-RNase alleles in 11 incompatibility groups, six of them reported here for the first time. Some cultivars with previously reported S-genotypes were initially used to confirm the size of S-RNase alleles previously identified using the primer pairs SRc-F and SRc-R (Vilanova et al., 2005) that amplify the first intron of the apricot S-RNase and allowed identifying the S-RNase alleles of the rest of the cultivars analyzed (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gene structure of the P. armeniaca RNase gene. Genomic sequence of the S4 allele showing the exons in green square, the primers used for the identification of S-alleles and the five conserved regions (C1, C2, C2, C3, RC4, and C5), and one hypervariable region (RHV) in blue square.

Two alleles, S1 and S7, could not be distinguished with the primers SRc-F/SRc-R, since these alleles showed similar fragment sizes in the first intron (Table 3). Thus, the PruC2/PruC4R primer combination designed from P. avium S-RNase-cDNA sequences (Tao et al., 1999) was additionally used to amplify the second intron. The alleles Sc and S8 had also similar fragment sizes in the first intron, and, in this case, the self-compatibility or self-incompatibility observed in the pollination experiments was used to distinguish between both alleles in each cultivar. A fragment of 420 or 430 bp was detected in some of the cultivars. These band sizes are close to the S6 allele, which has been reported as 424 bp (Kodad et al., 2013b) or 423 bp (Halász et al., 2010). To elucidate if the 430 bp and 420 bp bands obtained by an automatic sequencer correspond to new or pre-existing alleles, both fragments were cloned and sequenced, resulting in fragments of 421 and 414 bp, respectively.

Table 3.

S-alleles identified or/and sequenced in Prunus armeniaca.

| Alleles | Gen bank accession | Sequence | Fragment 1st intron | Fragment 2nd intron | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | EF491872/DQ386735 | Partial CDS, 1st intron | 355a,e | 2800c | Halász et al., 2007 |

| S1 | AY587561 | CDS, 1st and 2nd intron | 408a,e | 2260b,e | Romero et al., 2004 |

| S2 | AY587562 | CDS, 1st and 2nd intron | 334a,e | 990b | Romero et al., 2004 |

| S3 | 274a,e | ~450b,e | Vilanova et al., 2005 | ||

| S4 | AY587564 | CDS, 1st and 2nd intron | 249a,e | 247b,e | Romero et al., 2004 |

| S5 | 375a | 1400b | Vilanova et al., 2005 | ||

| S6/S52 | KF951503 (S52) | CDS, 1st and 2nd intron | 421a,e | 1386b,e | Unpublished |

| S7 | 408a,e | 900b,e | Vilanova et al., 2005 | ||

| S8 | AY884212 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 355a,e | 691b | Feng et al., 2006; Halász et al., 2007 |

| S9 | AY864826 | Partial CDS | 414a,e | 749b,e | Feng et al., 2006 |

| S10 | AY846872 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 583d | Feng et al., 2006 | |

| S11 | DQ868316 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 464d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S12 | DQ870628 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 360d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S13 | DQ870629 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 401d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S14 | DQ870630 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 492d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S15 | DQ870631 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 469d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S16 | DQ870632 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 481d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S17 | DQ870633 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 487d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S18 | DQ870634 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 1337d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S19 | EF133689 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 546d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S20 | EF160078 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 1934d | Zhang et al., 2008 | |

| S22 | HM053569 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 550d | Unpublished | |

| S23 | EU037262 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 505d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S24 | EU037263 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 168d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S25 | EU037264 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 583d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S26 | EU037265 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 289d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S27 | EU836683 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 230d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S28 | EU836684 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 948d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S29 | EF185300 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 285d | Wu et al., 2009 | |

| S30 | EF185301 | Partial CDS, 2nd Intron | 956d | Wu et al., 2009 |

Amplified using SRc-(F/R).

Amplified using Pru-C2 and Pru-C4R.

Amplified using Pru-C2 and Pru-C3R.

Amplified using other primers.

Our results.

The 421 bp fragment showed a 99% identity with the S52 present in the NCBI database. This allele was initially included in the NCBI database and unpublished but, recently, it has been reported in some Turkish apricot cultivars (Murathan et al., 2017). Since the S6 allele had not been previously sequenced, the S52 allele could indeed correspond to the S6 allele. The S6 allele could also be identified with the primers Pru-C2/Pru-C4, showing a PCR-fragment of around 1400 bp (1386 bp) that included the second intron; a 1386 bp fragment was also amplified in the S52 allele with the same primer combination strongly suggesting that S6 and S52 could be the same allele. Thus, in this work, the 421 bp fragment was assigned to the S6 allele.

The sequence of the 414 bp fragment showed high sequence similarity to S-alleles from other Prunus species, but not to any S-allele of Prunus armeniaca present in NCBI databases. The second intron of this allele was amplified with the primers Pru-C2/Pru-C4, showing a PCR-fragment of around 700 bp. Its cloning, sequencing and alignment revealed a 99% identity with the S9 allele [AY853594 (Feng et al., 2006)] and, consequently, the 414 bp fragment was assigned to the S9 allele.

The 45 self-incompatible cultivars were grouped in incompatibility groups according to their S genotypes following the numbering proposed by Halász et al. (2010) and Lachkar et al. (2013). While 26 of the cultivars analyzed were assigned to 11 different incompatibility groups, 19 cultivars were not assigned since only one S-RNase allele was detected (Table 2). S2 was the most frequent allele, appearing in 22 cultivars, followed by Sc (21), S9 (19), S6 (16), S3 (10), S8 (6), and S1 (4), while S7 was the least frequent allele found in only two cultivars.

Discussion

Self-pollination of the 92 apricot cultivars analyzed in this work and observation of pollen tubes under the microscope showed that 47 behaved as self-compatible and 45 as self-incompatible. The self-(in)compatibility of 68 cultivars is reported herein for the first time. The results in the remaining 23 cultivars have been compared with previous reports in which self-(in)compatibility was determined by the evaluation of the percentage of fruit set after self-pollinations in the field (Egea and Burgos, 1996; Rodrigo and Herrero, 1996; Burgos et al., 1997; Egea et al., 2010; Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017) or by the observation of pollen tube growth in pistils after self- and cross-pollinations (Egea and Burgos, 1996; Rodrigo and Herrero, 1996; Egea et al., 2010; Milatovic et al., 2013a,b). Thus, results herein agree with previous reports for “Canino,” “Corbato,” “Luizet,” “Mirlo Blanco,” “Mirlo Anaranjado,” “Mitger,” “Palsteyn,” “Paviot,” “Pepito del Rubio,” “Tadeo,” and “Tom Cot” as self-compatible, and also for “Bergarouge,” “Goldrich,” “Goldstrike,” “Harcot,” “Hargrand,” “Moniqui,” “Orangered,” “Pinkcot,” “Robada,” “Stark Early Orange,” “Stella,” “Sun Glo,” and “Veecot” as self-incompatible.

Approximately half of the cultivars analyzed (49%) were self-incompatible, a very high percentage compared to the situation some years ago when most European cultivars were self-compatible (Mehlenbacher et al., 1991), including the most traditional cultivars (Burgos et al., 1997). The other half (51%) were self-compatible. Due to this dramatic increase in the number of self-incompatible apricot cultivars, knowing their pollination requirements is necessary in order to choose compatible pollinizers in designing new commercial orchards as well as in selecting parental genotypes in apricot breeding programs.

The first case of cross-incompatibility of apricot cultivars in the European group was reported in the early 1990s in the Spanish cultivar Moniqui (Egea et al., 1991). The first incompatibility group in apricot, which consisted of three North American cultivars, was established several years later based on microscopic observations (Egea and Burgos, 1996), and, later, a more extensive study with 123 apricot cultivars, reported self-incompatibility in 42 cultivars (Burgos et al., 1997). Afterward the S-RNase proteins of seven S-alleles (S1–S7) and one allele associated with self-compatibility (Sc) were identified; the proteins were separated by non-equilibrium pH gradient electrofocusing (NEpHGE) in a gel that was later stained for ribonuclease activity (Alburquerque et al., 2002). The identification of the gene involved in GSI allowed S-allele identification by PCR analysis (Romero et al., 2004). In this first study, three S-alleles were sequenced (S1, S2, and S4) (Romero et al., 2004). In a later study, S-allele genotyping using the SRc-F and SRc-R primers, which have also been used in our study and amplify the first intron, identified four self-incompatibility alleles (S3, S5, S6, and S7) and one allele for self-compatibility (Sc) (Vilanova et al., 2005). Nine additional S-alleles (S8–S16) were identified by Halász et al. (2005) in 23 apricot accessions, mostly from Hungary. These last 13 alleles (S3, S5–S16) were only identified by PCR analysis. From then on, several studies have identified additional S-alleles by sequencing [S9 and S10 (Feng et al., 2006); S11–S20 (Zhang et al., 2008); S23–S30 (Wu et al., 2009)], but some of them have only been included in the NCBI database and not yet published. Some unpublished alleles such as S52 (Murathan et al., 2017)/S6 (our results) and S22 (Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017), have already been associated to several cultivars. Most of these studies have been performed in apricot cultivars from different origins like China, Turkey, Hungary, or Spain and, in some cases, the use of different primers or just the inaccuracy of band identification in a gel or even analyzed by an automatic fragment analyzing system can result in misidentification and the appearance of numerous homologies (Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017). For example, differences in reported fragment size can be found in the S2 [334 bp herein; 327 bp in Vilanova et al. (2005); 332 bp in Kodad et al. (2013b)] or Sc [358 bp herein; 353 bp in Vilanova et al. (2005); 355 bp in Kodad et al. (2013b)] alleles in addition to the S6 allele mentioned above. Moreover, many of the S-alleles, such as S10–S30 alleles, in which the first intron is still unknown, have only been partially sequenced.

From the 92 cultivars analyzed herein, 74 have been reported for the first time. Two alleles could be identified in most cultivars. However, a single allele was identified in 19 self-incompatible cultivars that may be due to inefficient PCR amplification of the S-RNase allele, in which the PCR primers may have a preferential amplification of the detected allele or caused by mismatching of PCR primers. Alternatively, the similar size of two alleles that show overlapping PCR fragments could make their identification difficult. Thus, the identification of additional S-RNase alleles in these genotypes requires more work focused on characterizing the S-locus. In 22 self-compatible cultivars, the identification of a unique allele could also be due to homozygosis of the self-compatible allele (Sc). Higher S-allele frequencies in the cultivars analyzed correspond to alleles S2, Sc, and S9 (19–22%). The allele Sc is associated with self-compatibility, and the alleles S2 and S9 are present in different cultivars resistant to sharka from USA (“Goldrich,” “Henderson,” “Orangered,” and “Sun Glo”) and Canada (“Hargrand” and “Veecot”), which have been used as parental genotypes in different breeding programs (Hormaza et al., 2007; Zhebentyayeva et al., 2012). On the other hand, the allele S7 is the least frequent and is present in only two cultivars: “Charisma” from South Africa, and “Goldbar” from USA.

Results herein, while confirmed the S-RNase genotype of 16 cultivars reported in previous studies, showed differences in the S-RNase genotype of “Corbato,” “Colorado,” “Lorna,” and “Palsteyn” reported previously (Burgos et al., 1998; Alburquerque et al., 2002; Vilanova et al., 2005; Donoso et al., 2009; Raz et al., 2009; Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017). To clarify their S-genotype, it would be necessary to identify their S-alleles in additional samples of the same cultivars. In this sense, sequencing can reveal the differences between a band fragment of an initial size, such as in our case, in which the initial fragment of 420 and 430 bp resulted in a S-allele of 414 bp (S9) and 421 bp (S6) respectively, after sequencing. Moreover, the sequence of the S6 (fragment of 421 bp) could reveal its similarity to S52 that has been recently assigned to Turkish apricot cultivars (Murathan et al., 2017).

The self-incompatibility identification has allowed allocating the cultivars to their corresponding incompatibility groups. This information, compiled with those reported in previous studies, has allowed describing six new incompatibility groups (XVIII–XXIII). Thus, self-incompatible cultivars within the same incompatibility group have the same S-genotype and are genetically incompatible with each other. On the other hand, cultivars with at least one different S-allele are placed in different incompatibility groups and are inter-compatible.

Although self-incompatibility was observed in nearly half of the cultivars analyzed herein, self-compatibility was still found in a good number of apricot cultivars. Self-compatibility has been related to particular S-alleles in different self-incompatible Prunus species, as almond (Fernández i Martí et al., 2014; Company et al., 2015), Japanese apricot (Ushijima et al., 2003), peach (Tao et al., 2006; Hanada et al., 2014), sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.) (Yamane et al., 2003), and sweet cherry (Wunsch and Hormaza, 2004; Marchese et al., 2007; Cachi and Wünsch, 2014). The breakdown of the incompatibility system has been reported in these Prunus species affecting the function of S-locus in the stylar S-determinant (S-RNase) and in the pollen S-determinant (F-box protein, SFB). It has also been related to mutations outside the S-locus (Hegedus et al., 2012; Company et al., 2015). In apricot, self-compatibility has been related with the insertion of a 358-bp fragment in the S-haplotype-specific F-box (SFB) gene. This insertion has been reported in self-compatible Spanish (Vilanova et al., 2006) and Hungarian (Halász et al., 2007) cultivars and, since they only differ in two nucleotides in the intron region, a common origin for them has been suggested (Halász et al., 2007). Moreover, a detailed study on the S8 allele, a very common allele in Hungarian cultivars, suggests that Sc could derive from the S8 allele (Halász et al., 2007). Thus, the insertion of 358-bp in the SFB gene is only present in the Sc haplotype and both alleles can only be distinguished by primers designed based on the SFB sequence such as the degenerate primers AprSFB-F1/R (Halász et al., 2007) or, as in our case, by pollination experiments.

The microscopy observations herein revealed self-compatibility in “Lorna” and “Palsteyn,” cultivars with the S1S2 genotype, “Victor 1” with the genotype S2S9, and “Golden Sweet” with the allele S3, but the Sc allele was not reported. A different mutation that is not linked to the S-locus has also been related to self-compatibility with a loss of pollen S-activity (Vilanova et al., 2006) and it has recently been associated with the M-locus (Zuriaga et al., 2013; Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017). Due to its limited distribution, it has been suggested that the M-locus would be in a very early stage of dispersion (Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017). Interestingly, the Sc allele is generally found in cultivars with the m-haplotype suggesting that this could be the result of a relaxed constrain for self-compatible selection (Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017). A similar S-genotype is also found in self-compatible “Katy,” in which the compatibility was associated to the M-locus (Zuriaga et al., 2013). A further analysis could reveal if self-compatibility in “Lorna,” “Palsteyn,” “Victor 1,” and “Golden Sweet” is also related to the M-locus.

Studies on S-allele identification can also provide information on the genetic diversity of the species. Thus, Chinese cultivars are mostly self-incompatible with a higher number of S-alleles (Zhang et al., 2008) compared with the limited number of S-alleles found in Western countries (Halász et al., 2007). A study on genetic diversity using AFLP markers showed a decreasing genetic diversity of apricot cultivars from the former USSR to Southern Europe (Hagen et al., 2002; Halász et al., 2007), which is coherent with the Asian origin of the species. However, although most traditional European cultivars are self-compatible (Burgos et al., 1997), due to breeding and crosses with Asian cultivars, the number of self-incompatibility cultivars is recently increasing in Western countries (Muñoz-Sanz et al., 2017; Murathan et al., 2017) and our study confirms this trend. Moreover, our results also show six new incompatibility groups in addition to the initial 17 incompatibility groups described so far.

Thus, the results obtained in this work using pollen tube growth observation in self-pollinated pistils, has allowed establishing the self-compatibility or self-incompatibility of 92 cultivars, including traditional and the main current cultivars as well as new cultivars from different breeding programs. S-RNase allele identification has allowed the allocation of a number of cultivars to their corresponding incompatibility groups, determining the incompatibility relationships between cultivars. The combination of these two complementary approaches results in valuable information for the appropriate selection of cultivars in commercial orchards and for the selection of parental genotypes in apricot breeding programs and a similar approach could be used in other woody perennial crops.

Author contributions

JR, JH, and MH: conceived the study; SH, JL, JR, JH, and MH: designed the experiments and wrote the paper; SH and JL performed the microscope observations, the PCR analysis, and analyzed the data; SH and JL contributed equally to this work.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erica Fadón, Reyes López, and Yolanda Verdún for technical assistance. We gratefully acknowledge AFRUCCAS for providing plant material used in this study.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (MEIC) - European Regional Development Fund, European Union (AGL2012-40239, AGL2013-43732-R, AGL2016-77267-R, and AGL2015-74071-JIN); Instituto Nacional de Investigación Agraria (RFP2015-00015-00, RTA2014-00085-00; RTA2017-00003-00); Gobierno de Aragón - European Social Fund, European Union (Grupo Consolidado A12_17R) and Agroseguro S.A.

References

- Alburquerque N., Egea J., Perez-Tornero O., Burgos L. (2002). Genotyping apricot cultivars for self-(in)compatibility by means of RNases associated with S alleles. Plant Breed. 121, 343–347. 10.1046/j.1439-0523.2002.725292.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos L., Berenguer T., Egea J. (1993). Self- and cross-compatibility among apricot cultivars. Hortscience 28, 148–150. [Google Scholar]

- Burgos L., Egea J., Guerriero R., Viti R., Monteleone P., Audergon J. M. (1997). The self-compatibility trait of the main apricot cultivars and new selections from breeding programmes. J. Hortic. Sci. 72, 147–154. 10.1080/14620316.1997.11515501 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burgos L., Pérez-Tornero O., Ballester J., Olmos E. (1998). Detection and inheritance of stylar ribonucleases associated with incompatibility alleles in apricot. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11, 153–158. 10.1007/s004970050133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cachi A. M., Wünsch A. (2014). Characterization of self-compatibility in sweet cherry varieties by crossing experiments and molecular genetic analysis. Tree Genet. Genomes 10, 1205–1212. 10.1007/s11295-014-0754-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D., Vekemans X., Castric V., Glémin S. (2005). Plant self-incompatibility systems: a molecular evolutionary perspective. New Phytol. 168, 61–69. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01443.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Wu Y., Chen M., He T., Feng J., Liang Q., et al. (2006). Inheritance and correlation of self-compatibility and other yield components in the apricot hybrid F1 populations. Euphytica 150, 69–74. 10.1007/s10681-006-9094-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Company R. S. I., Kodad O., Martí A. F. I., Alonso J. M. (2015). Mutations conferring self-compatibility in Prunus species: From deletions and insertions to epigenetic alterations. Sci. Hortic. 192, 125–131. 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.05.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Nettancourt D. (2001). Incompatibility and Incongruity in Wild and Cultivated Plants. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer-Verlang. [Google Scholar]

- Dirlewanger E., Graziano E., Joobeur T., Garriga-Calderé F., Cosson P., Howad W., et al. (2004). Comparative mapping and marker-assisted selection in Rosaceae fruit crops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 9891–9896. 10.1073/pnas.0307937101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoso J. M., Aros D., Meneses C., Infante R. (2009). Identification of S-alleles associated with self-incompatibility in apricots (Prunus armeniaca L.) using molecular markers. J. Food Agric. Environ. 7, 270–273. [Google Scholar]

- Egea J., Burgos L. (1996). Detecting cross-incompatibility of three North American apricot cultivars and establishing the first incompatibility group in apricot. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 121, 1002–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Egea J., Efigenio García J., Egea L., Berenguer T. (1991). Self-incompatibility in apricot cultivars. Acta Hortic. 293, 285–294. 10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.293.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egea J., Rubio M., Campoy J. A., Dicenta F., Ortega E., Nortes M. D., et al. (2010). “Mirlo Blanco”, “Mirlo Anaranjado”, and “Mirlo Rojo”: three new very early-season apricots for the fresh market. Hortscience 45, 1893–1894. [Google Scholar]

- Faust M., Surányi D., Nyujtó F. (1998). Origin and Dissemination of Apricot. Hortic. Rev. 22, 225–266. 10.1002/9780470650738.ch6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J., Chen X., Wu Y., Liu W., Liang Q., Zhang L. (2006). Detection and transcript expression of S-RNase gene associated with self-incompatibility in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 215–221. 10.1007/s11033-006-0011-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández i Martí A., Gradziel T. M., Socias i Company R. (2014). Methylation of the Sf locus in almond is associated with S-RNase loss of function. Plant Mol. Biol. 86, 681–689. 10.1007/s11103-014-0258-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra M. E., Rodrigo J. (2015). Japanese plum pollination: a review. Sci. Hortic. 197, 674–686. 10.1016/j.scienta.2015.10.032 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen L., Khadari B., Lambert P., Audergon J. M. (2002). Genetic diversity in apricot revealed by AFLP markers: species and cultivar comparisons. Theor. Appl. Genet. 105, 298–305. 10.1007/s00122-002-0910-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halász J., Hegedüs A., Hermán R., Stefanovits-Bányai É., Pedryc A. (2005). New self-incompatibility alleles in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) revealed by stylar ribonuclease assay and S-PCR analysis. Euphytica 145, 57–66. 10.1007/s10681-005-0205-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Halász J., Pedryc A., Ercisli S., Yilmaz K. U., Hegedus A. (2010). S-genotyping supports the genetic relationships between Turkish and Hungarian apricot germplasm. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. 135, 410–417. [Google Scholar]

- Halász J., Pedryc A., Hegedus A. (2007). Origin and dissemination of the pollen-part mutated SC haplotype which confers self-compatibility in apricot (Prunus armeniaca). New Phytol. 176, 792–803. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanada T., Watari A., Kibe T., Yamane H., Wünsch A., Gradziel T. M., et al. (2014). Two novel self-compatible S haplotypes in peach (Prunus persica). J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 83, 203–213. 10.2503/jjshs1.CH-099 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegedus A., Lénárt J., Halász J. (2012). Sexual incompatibility in Rosaceae fruit tree species: molecular interactions and evolutionary dynamics. Biol. Plant. 56, 201–209. 10.1007/s10535-012-0077-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hormaza J. I. (2002). Molecular characterization and similarity relationships among apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) genotypes using simple sequence repeats. Theor. Appl. Genet. 104, 321–328. 10.1007/s001220100684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormaza J. I., Pinney K., Polito V. S. (1996). Correlation in the tolerance to ozone between sporophytes and male gametophytes of several fruit and nut tree species (Rosaceae). Sex. Plant Reprod. 9, 44–48. 10.1007/BF00230365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hormaza J., Yamane H., Rodrigo J. (2007). Apricot, in Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants. V. 4, Fruit and Nuts, ed Kole C. (Berlin; Heidelberg; New York, NY: Springer; ), 171–185. [Google Scholar]

- Janick J. (2005). The origins of fruits, fruit growing, and fruit breeding. Plant Breed. Rev. 25, 255–321. 10.1002/9780470650301.ch8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies C. J., Belcher A. R. (1974). A fluorescent brightener used for pollen tube identification in vivo. Stain Technol. 49, 199–202. 10.3109/10520297409116977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julian C., Herrero M., Rodrigo J. (2010). Flower bud differentiation and development in fruiting and non-fruiting shoots in relation to fruit set in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Trees 24, 833–841. 10.1007/s00468-010-0453-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodad O., Halász J., Hegedus A., Messaoudi Z., Pedryc A., Socias i Company R. (2013a). Self-(in)compatibility and fruit set in 19 local Moroccan apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) genotypes. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 88, 457–461. 10.1080/14620316.2013.11512991 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kodad O., Hegedus A., Socias i Company R., Halász J. (2013b). Self-(in)compatibility genotypes of Moroccan apricots indicate differences and similarities in the crop history of European and North African apricot germplasm. BMC Plant Biol. 13:196. 10.1186/1471-2229-13-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachkar A., Fattouch S., Ghazouani T., Halász J., Pedryc A., Hegedüs A., et al. (2013). Identification of self-(in)compatibility S-alleles and new cross-incompatibility groups in Tunisian apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) cultivars. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 88, 497–501. 10.1080/14620316.2013.11512997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Layne R. E. C., Bailey C., Hough L. F. (1996). Apricots, in Fruit breeding, Volume I: Tree and Tropical Fruits, eds Janick J., Moore J. N. (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.), 79–111. [Google Scholar]

- Linskens H., Esser K. (1957). Uber eine spezifische anfarbung der pollenschlauche im griffel und die zahl der kallosepfropfen nach selbstung und fremdung. Naturwiss 44, 16 10.1007/BF00629340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese A., Bosković R. I., Caruso T., Raimondo A., Cutuli M., Tobutt K. R. (2007). A new self-compatibility haplotype in the sweet cherry “Kronio”, S5′, attributable to a pollen-part mutation in the SFB gene. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 4347–4356. 10.1093/jxb/erm322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlenbacher S. A., Cociu V., Hough F. L. (1991). Apricots (Prunus). Acta Hortic. 290, 65–110. 10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.290.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D., Nikolic D., Fotiriü-Akšic M., Radovic A. (2013a). Testing of self-(in)compatibility in apricot cultivars using fluorescence microscopy. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 12, 103–113. 10.1080/14620316.2007.11512215 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milatovic D., Nikolic D., Krska B. (2013b). Testing of self-(in)compatibility in apricot cultivars from European breeding programmes. Hortic. Sci. 2, 65–71. 10.17221/219/2012-HORTSCI [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Sanz J. V., Zuriaga E., López I., Badenes M. L., Romero C. (2017). Self-(in)compatibility in apricot germplasm is controlled by two major loci, S and M. BMC Plant Biol. 17:82 10.1186/s12870-017-1027-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murathan Z. T., Kafkas S., Asma B. M., Topçu H. (2017). S allele identification and genetic diversity analysis of apricot cultivars. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 92, 251–260. 10.1080/14620316.2016.1255568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raz A., Stern R. A., Bercovich D., Goldway M. (2009). SFB-based S-haplotyping of apricot (Prunus armeniaca) with DHPLC. Plant Breed. 128, 707–711. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2008.01613.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo J., Herrero M. (1996). Evaluation of pollination as the cause of erratic fruit set in apricot 'Moniqui'. J. Hortic. Sci. 71, 801–805. 10.1080/14620316.1996.11515461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo J., Herrero M. (2002). The onset of fruiting in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 76, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo J., Herrero M., Hormaza J. I. (2009). Pistil traits and flower fate in apricot (Prunus armeniaca). Ann. Appl. Biol. 154, 365–375. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2008.00305.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero C., Vilanova S., Burgos L., Martínez-Calvo J., Vicente M., Llácer G., et al. (2004). Analysis of the S-locus structure in Prunus armeniaca L. Identification of S-haplotype specific S-RNase and F-box genes. Plant Mol. Biol. 56, 145–157. 10.1007/s11103-004-2651-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonneveld T., Tobutt K. R., Robbins T. P. (2003). Allele-specific PCR detection of sweet cherry self-incompatibility (S) alleles S1 to S16 using consensus and allele-specific primers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 1059–1070. 10.1007/s00122-003-1274-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland B. G., Robbins T. P., Tobutt K. R. (2004). Primers amplifying a range of Prunus S-alleles. Plant Breed. 123, 582–584. 10.1111/j.1439-0523.2004.01016.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó Z., Nyéki J. (1991). Blossoming, fructification and combination of apricot varieties. Acta Hortic. 293, 295–302. 10.17660/ActaHortic.1991.293.34 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R., Watari A., Hanada T., Habu T., Yaegaki H., Yamaguchi M., et al. (2006). Self-compatible peach (Prunus persica) has mutant versions of the S haplotypes found in self-incompatible Prunus species. Plant Mol. Biol. 63, 109–123. 10.1007/s11103-006-9076-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R., Yamane H., Sassa H., Mori H., Gradziel T. M., Dandekar A. M., et al. (1997). Identification of stylar RNases associated with gametophytic self-incompatibility in almond (Prunus dulcis). Plant Cell Physiol. 38, 304–311. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R., Yamane H., Sugiura A., Murayama H., Sassa H., Mori H. (1999). Molecular typing of S-alleles through identification, characterization and cDNA cloning for S-RNases in sweet cherry. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 124, 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima K., Sassa H., Dandekar A. M., Gradziel T. M., Tao R., Hirano H. (2003). Structural and transcriptional analysis of the self-incompatibility locus of almond: Identification of a pollen-expressed F-Box Gene with haplotype-specific polymorphism. Plant Cell 15, 771–781. 10.1105/tpc.009290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova S., Badenes M. L., Burgos L., Martínez-Calvo J., Llácer G., Romero C. (2006). Self-compatibility of two apricot selections is associated with two pollen-part mutations of different nature. Plant Physiol. 142, 629–641. 10.1104/pp.106.083865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilanova S., Romero C., Llacer G., Badenes M. L., Burgos L. (2005). Identification of self-(in)compatibility alleles in apricot by PCR and sequence analysis. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 130, 893–898. [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. H., Friedman W. E., Arnold M. L. (1999). Developmental selection within the angiosperm style: using gamete DNA to visualize interspecific pollen competition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9201–9206. 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Gu C., Zhang S. L., Zhang S. J., Wu H. Q., Heng W. (2009). Identification of S-haplotype-specific S-RNase and SFB alleles in native Chinese apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 84, 645–652. 10.1080/14620316.2009.11512580 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wunsch A., Hormaza J. I. (2004). Genetic and molecular analysis in Cristobalina sweet cherry, a spontaneous self-compatible mutant. Sex. Plant Reprod. 17, 203–210. 10.1007/s00497-004-0234-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H., Ikeda K., Hauck N. R., Iezzoni A. F., Tao R. (2003). Self-incompatibility (S) locus region of the mutated S6-haplotype of sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) contains a functional pollen S allele and a non-functional pistil S allele. J. Exp. Bot. 54, 2431–2437. 10.1093/jxb/erg271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Chen X., Chen X., Zhang C., Liu X., Ci Z., et al. (2008). Identification of self-incompatibility (S-) genotypes of Chinese apricot cultivars. Euphytica 160, 241–248. 10.1007/s10681-007-9544-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhebentyayeva T., Ledbetter C., Burgos L., Llacer G. (2012). Apricot, in Fruit Breeding, eds Badenes M. L., Byrne D. (Boston, MA: Springer; ), 415–458. [Google Scholar]

- Zuriaga E., Muñoz-Sanz J. V., Molina L., Gisbert A. D., Badenes M. L., Romero C. (2013). An S-locus independent pollen factor confers self-compatibility in “Katy” apricot. PLoS ONE 8:e53947. 10.1371/journal.pone.0053947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]