Abstract

There is a spectacular variability in trichome types and densities and trichome metabolites across species, but the functional implications of this variability in protection from atmospheric oxidative stresses remain poorly understood. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the possible protective role of glandular and non-glandular trichomes against ozone stress. We investigated the interspecific variation in types and density of trichomes and how these traits were associated with elevated O3 impacts on visible leaf damage, net assimilation rate, stomatal conductance, chlorophyll fluorescence and emissions of lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway products in 24 species with widely varying trichome characteristics and taxonomy. Both peltate and capitate glandular trichomes played a critical role in reducing leaf ozone uptake, but no impact of non-glandular trichomes was observed. Across species, the visible ozone damage varied 10.1-fold, reduction in net assimilation 3.3-fold and release of LOX compounds 14.4-fold, and species with lower glandular trichome density were more sensitive to ozone stress and more vulnerable to ozone damage compared to species with high glandular trichome density. These results demonstrate that leaf surface glandular trichomes constitute a major factor in reducing ozone toxicity and function as a chemical barrier which neutralizes the ozone before it enters the leaf.

Keywords: glandular trichomes, leaf damage, LOX products, ozone stress, ozone uptake, photosynthesis, PTR-TOF-MS

Introduction

Average global ozone (O3) concentration has approximately doubled during the 20th century and is expected to increase further (Vingarzan, 2004; Fowler et al., 2008; Logan et al., 2012; Hartmann et al., 2013; Oltmans et al., 2013). Currently, the ambient O3 concentration in the northern hemisphere is around 20-45 nmol mol-1 and it occasionally reaches 120 nmol mol-1 or more (Fowler et al., 2008; Lai et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2016). Numerous studies have revealed that elevated O3 negatively impacts plant growth and development and decreases forest productivity and crop yields as well as plant biodiversity (Ainsworth et al., 2012; Leisner & Ainsworth, 2012; Wilkinson et al., 2012; Fares et al., 2013). It is well-established that some plant species are more tolerant to elevated O3 concentrations than others, but the complexity of underlying mechanisms that lead to enhanced O3 tolerance is not fully understood (Flowers et al., 2007; Ainsworth et al., 2012; Li et al., 2016; Ainsworth, 2017; Feng et al., 2017).

Plant response to O3 is a complex process involving several biological levels from molecular to organ and whole plant responses. O3 enters plants mainly through the stomata, and once inside the leaf, it reacts with organic molecules in the apoplast leading to direct formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well as induction of endogenous formation of ROS that can collectively lead to the onset of cell damage and programmed cell death when the O3 concentration exceeds critical levels (Wohlgemuth et al., 2002; Pasqualini et al., 2003; Beauchamp et al., 2005; Fiscus et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2011; Ainsworth, 2017; Li et al., 2017; Kanagendran et al., 2017). Generally, progressive and irreversible reductions in photosynthetic activity occur upon acute O3 exposure, and direct injury to leaf cells in O3-exposed leaves is also associated with the release of ubiquitous stress-induced volatiles such as volatile products of lipoxygenase (LOX) reactions comprising of various C6 aldehydes and alcohols (Heiden et al., 1999; Beauchamp et al., 2005; Loreto & Schnitzler, 2010; Li et al., 2017). Reductions in the quantum yield of primary photochemistry in the dark-adapted state and emissions of LOX and other volatile organic compounds (VOC) are widely used characteristics to assess plant response to O3 stress (Nussbaum et al., 2001; Beauchamp et al., 2005; Bussotti et al., 2011; Chutteang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017).

O3 sensitivity varies across species and depends on several species-specific biochemical, physiological and morphological traits (Li et al., 2016). Regarding the physiological and biochemical traits, differences in O3 sensitivity have been related to inherent differences in stomatal conductance and to the leaf antioxidant capacity (Brosché et al., 2010; Fares et al., 2013). Very few studies have been conducted to understand to which extent morphological traits such as trichome morphology and density or differences in exposed mesophyll cell surface or other structural traits such as leaf mass per unit area, leaf nitrogen content and life form may affect interspecific variation in O3 sensitivity when exposed to acute rather than chronic low to moderate level O3 (Franzaring et al., 1999; Prozherina et al., 2003; Hayes et al., 2007; Li et al., 2016).

The leaf surface is covered by glandular and/or non-glandular trichomes in many species. Non-glandular trichomes, which are not able to produce or secrete phytochemicals, serve to increase herbivore resistance by interfering mechanically with herbivore movement and/or feeding (Eisner et al., 1998; Corsi & Bottega, 1999; Kennedy, 2003). In addition, by increasing surface reflectance they contribute to reduced solar radiation interception and thus, to enhanced resistance to low water availabilities and photoinhibition stress (Ehleringer, 1981, 1982; Cescatti & Niinemets, 2004; Hallik et al., 2017). However, due to increasing surface area, non-glandular trichomes could potentially participate in chemical reactions on leaf surface as well, e.g. in O3 adsorption, but little is known of relationships between non-glandular trichome density and species O3 resistance. However, given that non-glandular trichomes are covered by a wax layer that consists of saturated hydrocarbons that have low reactivity with O3 (Corsi & Bottega, 1999), it might also be that the effect of non-glandular trichomes in leaf O3 resistance is minor despite greater surface area.

Glandular trichomes, which store and secrete various secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, monoterpenes or sesquiterpene lactones, are widely distributed on leaf surfaces and may contribute significantly to defense against diverse biotic and environmental challenges (Ehleringer et al., 1976; Huci et al., 1982; Rieseberg et al., 1987; Wagner, 1991; Fahn & Shimony, 1996; Kostina et al., 2001; Heinrich et al., 2002; Amme et al., 2005; Paoletti et al., 2007; Peiffer et al., 2009; Agati et al., 2012; Jud et al., 2016; Lihavainen et al., 2017; Thitz et al., 2017). Two major types of glandular trichomes, peltate and capitate, have been discerned. There are various types of capitate trichomes varying in stalk and head size, and although the basic morphology of peltate trichomes varies less, these is still a significant variation in the shapes and sizes of peltate trichomes as well (Ascensão et al., 1995; Ascensão & Pais, 1998; Baran et al., 2010; Glas et al., 2012). Capitate trichomes are specialized to produce and store a large amount of diterpenes and a wide array of non-volatile or poorly volatile compounds such as defensive proteins, acylated sugars and esters that are directly exuded onto trichome surface (Sallaud et al., 2012; Jud et al., 2016). Their primary function is thought to repel pests. Peltate glandular trichomes, on the other hand, mostly produce and store biogenic volatile or semi-volatile organic compounds related to plant abiotic or biotic stress induced responses (Corsi & Bottega, 1999; Gang et al., 2001; Wagner et al., 2004). Recently, Jud et al. (2016) showed that semi-volatile organic compounds such as various diterpenoids exuded by the glandular trichomes of Nicotiana tabacum act as an efficient chemical protection shield against stomatal O3 uptake by reacting with and thereby depleting O3 at the leaf surface. However, the shape and size of glandular trichomes as well as the metabolites stored vary greatly across plant species, and the generality of this finding is currently unclear. Although several studies have demonstrated the important protective role of trichomes in O3 stress resistance in a given species (Huci et al., 1982; Prozherina et al., 2003; Paoletti et al., 2007; Riikonen et al., 2010), their potential role in O3 resistance across different plant species, in particular under acute exposure, has not been investigated to date.

Considering leaf surface reactions, it is important to distinguish between O3 exposure, O3 uptake by leaf and uptake through the stomata to accurately characterize the thresholds for acute responses. However, this is not fully possible until we discern the extent of O3 neutralization at the leaf surface (Jud et al., 2016) and determine the extent to which leaf internal O3 concentrations can build up (Moldau & Bichele, 2002; Niinemets et al., 2014). To fill the gap in understanding the role of trichomes in defense against O3 stress, we examined interspecific variation in O3 sensitivity in 24 species with varying densities of non-glandular and glandular trichomes on the leaf surface. The main hypotheses tested were (1) leaves with a high density of glandular trichomes have higher rates of non-stomatal O3 uptake, resulting in greater O3 resistance as evidenced by less negative effects on their physiology at the given O3 exposure concentration; (2) non-glandular trichomes have no significant protective role under O3 exposure; (3) peltate glandular trichomes have a major impact on non-stomatal O3 uptake. We demonstrate a broad relationship between O3 resistance and glandular trichome density across a highly diverse set of species, suggesting that glandular trichomes do serve as an important antioxidative barrier. To our knowledge, this is the first study to provide information on how non-glandular and glandular trichomes can contribute to plant ability to cope with increased O3 levels and maintain physiological homeostasis under atmospheric oxidative stress.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Twenty three herbaceous species, selected for their wide range of trichome characteristics (trichome density, glandular vs. non-glandular, capitate vs. peltate) were chosen for this study (Anchusa officinalis L., Arctium tomentosum Mill, Carduus crispus L., Cucumis sativus L. cv. Libelle F1, Cucurbita pepo L., Erigeron acer L., Erigeron canadensis L., Erodium cicutarium L., Geranium palustre L., Geranium pratense L., Geranium robertianum L., Lavandula angustifolia Mill, Mentha × piperita L., Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. W38, Ocimum basilicum L., Phaseolus vulgaris L. cv. Saxa, Rosmarinus officinalis L., Salvia officinalis L., Silene latifolia Poir, Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Pontica, Tussilago farfara L., Urtica dioica L. and Verbascum thapsus L.). In addition, although woody species generally exhibit greater tolerance to O3 than herbaceous species, we chose a single woody species, Betula pendula Roth, was included. Plants of C. sativus, N. tabacum, O. basilicum, P. vulgaris, S. lycopersicum and V. thapsus were grown from seed (seed sources: C. sativus: Seston Seemned OÜ, Estonia; N. tabacum: gift of I. Bichele, University of Tartu; O. basilicum and S. lycopersicum: SC Agrosel SRL, Romania; P. vulgaris: Dalema UAB, Vilnius, Lithuania; the seed of V. thapsus were collected in the field in Tartu, Estonia). After germination, seedlings were replanted in 2 L plastic pots containing a commercial potting mix (Kekkilä Group, Vantaa, Finland) and maintained in a plant room with light intensity at plant level of 400 μmol m-2 s-1 (HPI-T Plus 400 W metal halide lamps, Philips) during 12 h photoperiod. The day/night temperatures were maintained at 24/20 °C and daytime humidity at 60%. Seedlings of B. pendula, and plants of G. palustre, G. pratense and U. dioica were collected from the campus of the Estonian University of Life Sciences (EULS), Tartu, Estonia (58°23' N, 27°05' E, elevation 40 m), the plants of E. acer, E. canadensis, E. cicutarium and S. latifolia from Ihaste, Tartu (58°21' N, 26°46' E, elevation 41 m), and plants of G. robertianum from Pühajärve, Estonia (58°03' N, 26°28' E, elevation 131 m). The plants were replanted in 2 L plastic pots containing the same potting mix, and maintained on the roof of the plant biology lab building at the campus of EULS and were exposed to full sunlight under ambient conditions. All plants were fertilized once in two weeks with Biolan NPK (N of 100 mg L-1, P of 30 mg L-1, and K of 200 mg L-1) complex fertilizer with microelements (Biolan Oy, Kekkilä Group, Vantaa, Finland) and they were watered every day to maintain optimal growth conditions.

In the case of N. tabacum and V. thapsus that had leafed petioles making it difficult to achieve a good seal upon enclosure of the leaf to the gas-exchange chamber, we removed the part of the lamina attached to the base of the leaf, while avoiding cutting through first- and second-order veins. In order to minimize the influence of leaf damage on volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions, at least two days were allowed for recovery before conducting measurements. According to previous measurements, the effect of lamina wounding is short-living with the bulk of the stress volatiles released within first 5-10 min after wounding (Portillo-Estrada et al., 2015). We also did not observe any subsequent induction of stress volatiles and volatile isoprenoids after wounding, and leaf photosynthesis measurements with clip-on type gas-exchange system (Walz GFS-3000, Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) demonstrated that the wounding also did not alter foliage photosynthesis rate and stomatal conductance at 48 h since wounding stress (data not shown).

The leaves of A. officinalis, A. tomentosum, C. crispus, and T. farfara were collected from the campus of the EULS and leaves of C. pepo, L. angustifolia, M. × piperita, R. officinalis and S. officinalis were collected from the gardens of Tartu city. All plants sampled had developed in open areas exposed to full sunlight. Early in the morning, high light exposed terminal shoots with multiple leaves were excised with a sharp razor blade under water and immediately transported to the laboratory. Once in the laboratory, the cut ends of the shoots were recut under water and a representative leaf was selected for measurements. All measurements were conducted with fully-expanded non-senescent leaves.

Gas-exchange system for photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, volatile organic compound and ozone concentration measurements

We used a custom-built gas-exchange system with a temperature-controlled 1.2 L glass chamber described in detail by Copolovici & Niinemets (2010) to fumigate leaves with O3 and to measure leaf gas exchange characteristics (net photosynthesis and stomatal conductance) and VOC. The ambient air was drawn from outside, passed through a 10 L buffer volume, purified by an O3 trap and a charcoal filter, humidified by a custom-made humidifier to standard air humidity of 60% and then passed at a flow rate of 1.6 L min-1 to the glass chamber. The air entering or leaving the chamber was analyzed alternately, with an electronic valve switching between incoming (reference) and outgoing (measurement) air streams. To mix the chamber air and to minimize leaf boundary layer resistance, a fan was mounted inside the chamber. The leaf temperature was maintained at 25 °C, ambient CO2 concentration at 400 µmol mol-1 and light intensity at the leaf surface was 1000 µmol m-2 s-1 during the experiment.

An infra-red dual-channel gas analyzer (CIRAS II, PP-Systems, Amesbury, MA, USA) operated in absolute mode was used to measure CO2 and H2O concentrations, a proton transfer reaction-time of flight-mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS, Ionicon Analytik GmbH, Innsbruck, Austria) to determine VOC concentration and a UV-photometric O3 sensor (Model 49i, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) to measure O3 concentrations. All instruments were operated continuously and CO2 and H2O concentrations and all PTR-TOF-MS signals were recorded every 10 s and the range of O3 concentrations was recorded for every 15 min interval. Reference measurements (incoming air) were conducted every 10-15 min.

Ozone fumigation treatments

Ozone exposure treatments were carried out using O3 concentrations that constituted a moderately severe stress leading to visible leaf damage but not resulting in leaf death during more than 20 hours following the experimental treatment. After the leaves were enclosed in the chamber, continuous measurements of photosynthetic characteristics and trace gas exchange were begun immediately. O3 fumigation was started after stabilization of net photosynthesis and VOC emissions, typically 20-30 min after leaf enclosure. O3 was generated in a quartz glass reaction chamber (Stable Ozone Generator, Ultra-Violet Products Ltd, Cambridge, UK) under UV light (λ=185 nm) and monitored by a UV-photometric O3 sensor (Model 49i, Thermo Scientific, Massachusetts, USA). The O3 enriched air from the reaction chamber was mixed with the air stream entering the leaf chamber. The leaf was fumigated with a step-wise increase in O3 concentration as follows: 100 ± 5 nmol mol-1 of O3 for 30 min, followed by 200 ± 10 nmol mol-1 for 30 min, and so on progressively, increasing O3 concentration by 100 nmol mol-1 in half-hour steps until the final maximum O3 concentration that lead to a sharp decrease in net assimilation rate and stomatal conductance was reached. This final O3 concentration varied by plant species. Due to logistic difficulties, PTR-TOF-MS measurements could be carried out in six species with different glandular trichome density (C. sativus, N. tabacum, O. basilicum, P. vulgaris, S. lycopersicum and V. thapsus). In order to further investigate the effect of O3 concentration rather than O3 uptake on volatile LOX product emissions, we applied the same O3 stress with a step-wise increase from 100 to 500 nmol mol-1 for these six species. In all cases, the duration of exposures at each O3 concentration was 30 min and the stability of O3 concentration within the leaf chamber was ± 5-10% of the target. The gas-exchange characteristics and trace gas-exchange were also continuously monitored for 21 h after each of the treatments. The treated leaves were then harvested and their area (S) and the quantitative degree of damage visible as necrotic or chlorotic lesions were estimated using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Operation of the PTR-TOF-MS and online monitoring of the kinetics of volatile release

The main advantages of PTR-TOF-MS are simultaneous detection of all masses rather than predetermined masses, and higher sensitivity, higher mass resolution as well as improved accuracy over the traditional quadrupole PTR (PTR-QMS); this allows quantification of a larger number of organic compounds at trace levels in real time (Jordan et al., 2009; Graus et al., 2010). The PTR-TOF-MS was operated according to the method described in detail in Graus et al. (2010), Brilli et al. (2011) and Portillo-Estrada et al. (2015). The drift tube voltage was kept at 600 V at 2.3 mbar drift pressure and 60°C temperature, corresponding to an E/N ≈ 130 Td in H3O+ reagent ion mode. The PTR-TOF-MS system was calibrated with a calibration standard mixture containing key volatiles from different compound families (Ionimed Analytic GmbH, Austria). The data acquisition software TofDaq (Tofwerk AG, Switzerland) was used to acquire the raw data and the data were further post-processed by PTR-MS Viewer software (PTR-MS Viewer v3.1, Tofwerk AG, Switzerland) (Jordan et al., 2009; Portillo-Estrada et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017).

The total amount of lipoxygenase pathway products (LOX products) emission presented in this study is the sum of the dominant compounds with mass signals m/z 81.070 [hexenal (fragment)], m/z 83.085 [hexenol + hexanal(fragments)], m/z 85.101 [hexanol (fragment)], m/z 99.080 [(Z)-3-hexenal + (E)-3-hexenal (main)], m/z 101.096 [(Z)-3-hexenol + (E)-3 hexenol + (E)-2-hexenol + hexanal (main)] (Brilli et al., 2011; Portillo-Estrada et al., 2015; Li et al., 2017).

Chlorophyll fluorescence measurements

To visualize the distribution of photosynthetic electron transport activity of leaves before and after the O3 treatment, a portable Imaging-PAM chlorophyll fluorometer with ImagingWin software (Imag-MIN/B, Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany) was used. The Mini version of the Imaging-PAM M-series has a measurement window area of 24×32 mm and uses a CCD camera (640×480 pixel) for fluorescence imaging and 12 high-power LED lamps to provide actinic light and high-intensity light flashes. After the leaf was fixed in the leaf holder of the Imaging PAM, and dark-adapted for 30 min at 25°C, the minimum fluorescence yield (F0) was measured, the maximum dark-adapted fluorescence yield (Fm) was then determined by illuminating the leaves with a 500 ms pulse of saturating irradiance of 2700 µmol quanta m-2 s-1. The spatially-averaged maximum dark-adapted quantum yield of PSII, Fv/Fm was calculated as (Fm-F0)/Fm.

Scanning electron microscopy and analyses of density and morphology trichomes

To quantify the trichome characteristics, a Zeiss EVO LS15 Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM, Carl Zeiss AG, Jena, Germany) was used. A fresh leaf adjacent to the leaf used for O3 fumigation was mounted on brass stubs. The samples were viewed and images taken with the ESEM at an acceleration voltage of 15 kV under the low vacuum mode. Images acquired from ESEM were analyzed with the ImageJ software. Trichome density was estimated from the middle zones of both leaf surfaces (adaxial and abaxial) avoiding major veins. Three to ten areas of view were selected for measurements, and all trichomes were counted within 1 mm2 areas. The type of glandular trichomes - peltate or capitate - was identified from ESEM images as suggested by Ascensão et al. (1995), Ascensão & Pais (1998), Ko et al. (2007) and Baran et al. (2010), and averages were calculated for all fields of view for the given leaf on both upper and lower surface.

Empty chamber corrections

The background volatile samples were measured from the empty chamber before the plant measurements to correct for possible emission of volatiles adsorbed previously on gas-exchange system components. Although such corrections were minor (≤1%), they were included in the calculations for consistency (Niinemets et al., 2011). O3 destruction due to surface reactions (“uptake”) by the empty chamber ( nmol mol-1) was measured before the plant measurements and calculated as:

| Eqn 1 |

where is the O3 concentration at the chamber inlet and that at the chamber outlet. The values obtained were subsequently used to correct all measurements of leaf O3 uptake. Overall, this correction was minor, less than 5% of total O3 uptake when leaves were enclosed in the chamber.

Calculations of photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, trace gas emission rates and ozone uptake

Net assimilation rate (An) and stomatal conductance (gs) per leaf area were calculated according to von Caemmerer & Farquhar (1981).

Volatile emissions rates (ϕx, nmol m-2 s-1) were calculated as

| Eqn 2 |

where F is the flow rate through the chamber (1.19×10-3 mol s-1), and S is the leaf area enclosed in the chamber (m2), Co(X) is the concentration (nmol mol-1) of the target VOC (compound X) measured at the chamber outlet and Ci(X) of that measured at the chamber inlet, Cc(X) is the correction to account for the possible release of the given compound released from the gas-exchange system components (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Li et al., 2017).

The total amount of target VOC emitted over a certain time (ΦX) (nmol m-2) was integrated as:

| Eqn 3 |

where tPS and tPE are the start and end times of the target VOC emission release, Δt is the measurement time interval (10 s), and ϕX is the emission rate of the target VOC measured over this time interval (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Li et al., 2017). The total emission values correspond to the whole experiment, from elicitation to 21 h since the end of the experiment.

The rate of O3 uptake by the leaf (ϕLO3, nmol m-2 s-1) was calculated as:

| Eqn 4 |

where Cin and Cout are the O3 concentrations in the air entering and exiting the leaf chamber (nmol mol-1). We calculated Cin and Cout as the average value over the given time interval due to the fluctuations of O3 concentration produced by the ozone generator and manual adjustment of Cin to account for changes in O3 uptake during the exposure.

The rate of O3 uptake by stomata (ϕGO3, nmol m-2 s-1) was determined by:

| Eqn 5 |

where is intercellular O3 concentration (nmol mol-1), and 2.03 is the ratio of water vapor to O3 diffusivities (Li et al., 2017). Given that is typically small compared with Cout, and it cannot be estimated from these measurements, it was assumed to be zero (Laisk et al., 1989; but see Moldau & Bichele, 2002). To be consistent with the Cout calculations, stomatal conductance (gs) was also determined as the average value over the same time interval.

The total amount of leaf and stomatal O3 uptake (ΦY, where Y stands either for leaf, LO3, or for stomatal, GO3, O3 uptake) over the given exposure period (O3 dose) was integrated as:

| Eqn 6 |

where tS and tE are the start and end times of O3 exposure, Δt is the time interval of the O3 exposure, and ϕY is either the mean rate of ϕLO3 or the mean rate of ϕGO3 measured during this time interval (Beauchamp et al., 2005). Ultimately, the total amount of non-stomatal O3 uptake (ΦNGO3), i.e. presumably O3 uptake by the leaf surface was determined by:

| Eqn 7 |

where ΦLO3 is the total measured amount of O3 uptake by the whole leaf and ΦGO3 is the calculated O3 uptake through the stomata. We note that chemical quenching of O3 in chamber air by volatiles in the leaf chamber or by volatiles on the leaf surface is also possible and is incorporated in the value of ΦNGO3.

Quantitative characterization of the protective role of glandular trichomes against O3 stress

To further characterize the functional role of glandular trichomes in ameliorating changes in leaf physiological characteristics and LOX product emission under O3 stress, the plant response per unit O3 taken up by the leaf (γ, O3 uptake weighted response) was calculated as:

| Eqn 8 |

where Z represents the percentage decrease of An, gs and Fv/Fm or the total amount or maximum rate of LOX products emitted over a certain time (Eqn 3). Analogously, the plant response per unit O3 taken up by stomata was also calculated for each of these traits.

Data analysis

All O3 fumigation treatments were conducted in three to five replications (n=3-5) with different plants in each species. Linear- and non-linear regressions were used to analyze the effects of O3 on foliage traits and relationships between leaf trichome density and physiological traits. All relationships were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Trichome morphology, distribution and density

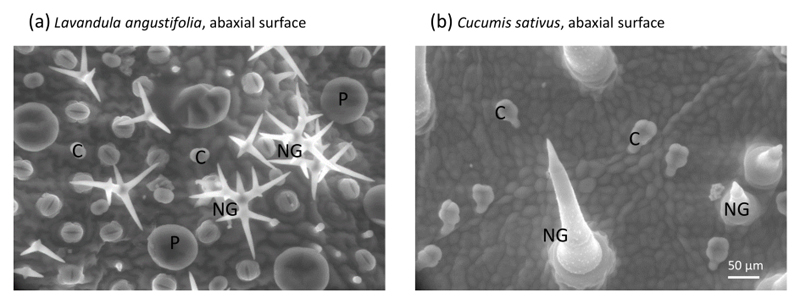

Non-glandular and glandular trichomes were both present on the leaf surfaces of the 24 studied species (Fig. 1). The density of non-glandular trichomes varied 250-fold across species (Table 1). Two types of glandular trichomes (peltate and capitate) were identified (Fig. 1). Capitate glandular trichomes were present in all species, but peltate glandular trichomes were found only in 12 species belonging to the family Lamiaceae (L. angustifolia, M. × piperita, O. basilicum, R. officinalis and S. officinalis) and Geraniaceae (E. cicutarium, G. pratense and G. robertianum) and in B. pendula, E. canadensis, S. latifolia and U. dioica (Table 1). The density of capitate glandular trichomes varied from 1 mm-2 in C. pepo to 90 mm-2 in R. officinalis, and peltate glandular trichome density varied from 5.9 mm-2 in G. robertianum to 60 mm-2 in R. officinalis (Table 1). No significant correlation between glandular and non-glandular trichome density was found in the species with only capitate trichomes and with both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Environmental scanning electron microscope (ESEM) micrographs of (a) non-glandular (NG) and peltate (P) and capitate (C) glandular trichomes on the lower surface of Lavandula angustifolia and (b) lower surface of Cucumis sativus containing non-glandular (NG) and glandular capitate trichomes (C). Scale bars on the bottom right.

Table 1.

Mean ± SE densities (number mm-2) of non-glandular (NGT), peltate (PGT) and capitate (CGT) glandular trichomes in the 24 plant species investigated.

| Species | Family | NGT (number mm-2) | CGT (number mm-2) | PGT (number mm-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anchusa officinalis | Boraginaceae | 6.8 ± 0.9 | 12.9 ± 3.5 | |

| Arctium tomentosum | Asteraceae | 30.1 ± 1.1 | 60.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Betula pendula | Betulaceae | 20.1 ± 1.3 | 10.02 ± 0.41 | 60.2 ± 1.5 |

| Carduus crispus | Asteraceae | 30.1 ± 1.1 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | |

| Cucumis sativus | Cucurbitaceae | 15.036 ± 0.021 | 28.1 ± 0.8 | |

| Cucurbita pepo | Cucurbitaceae | 50.1 ± 2.0 | 1.0274 ± 0.0011 | |

| Erigeron acer | Asteraceae | 26.4 ± 3.2 | 9.32 ± 0.09 | |

| Erigeron canadensis | Asteraceae | 15.2 ± 2.3 | 19 ± 5 | 7.8 ± 2.2 |

| Erodium cicutarium | Geraniaceae | 9.3 ±1.3 | 20.9 ± 2.0 | 6.3 ±2.4 |

| Geranium palustre | Geraniaceae | 17 ± 10 | 33 ± 16 | |

| Geranium pratense | Geraniaceae | 20 ± 7 | 58 ± 10 | 6.35 ± 0.35 |

| Geranium robertianum | Geraniaceae | 8.13 ± 0.20 | 15.6 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 2.1 |

| Lavandula angustifolia | Lamiaceae | 65.3 ± 1.5 | 65.2 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 1.2 |

| Mentha × piperita | Lamiaceae | 21.0 ± 1.3 | 37.1 ± 1.1 | 50.2 ± 1.7 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | Solanaceae | 5.172 ± 0.011 | 70.2 ± 1.2 | |

| Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | 1.034 ± 0.011 | 1.215 ± 0.021 | 9.13 ± 0.05 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris | Fabaceae | 2.041 ± 0.007 | 10.132 ± 0.012 | |

| Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | 250.3 ± 2.2 | 90.4 ± 2.7 | 60.3 ± 2.0 |

| Salvia officinalis | Lamiaceae | 70.2 ± 1.2 | 10.114 ± 0.012 | 45.2 ± 1.1 |

| Silene latifolia | Caryophyllaceae | 15.1 ± 3.3 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 8.3 ± 1.3 |

| Solanum lycopersicum | Solanaceae | 1.243 ± 0.021 | 9.035 ± 0.022 | |

| Tussilago farfara | Asteraceae | 3.053 ± 0.011 | 37.3 ± 0.9 | |

| Urtica dioica | Urticaceae | 93 ± 40 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 29 ± 12 |

| Verbascum thapsus | Scrophulariaceae | 10.217 ± 0.042 | 47.03 ± 0.07 |

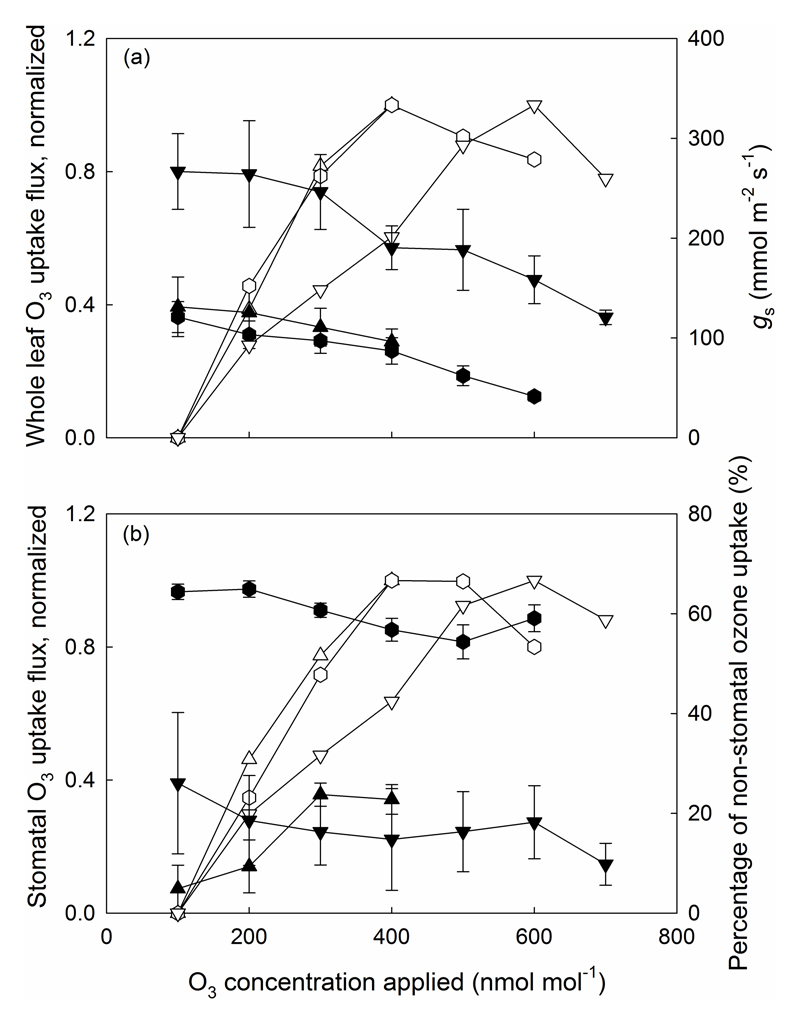

Kinetics of O3 uptake flux and stomatal conductance with rising O3 concentration

During stepwise increases in O3 in all species, stomatal conductance (gs) declined with increasing O3 exposure (filled symbols, Fig. 2a for representative responses in P. vulgaris, N. tabacum and S. lycopersicum). Relative to the values prior to low-level O3 fumigation (100 nmol mol-1), stomatal conductance (gs) decreased by 27% in P. vulgaris, 66% in N. tabacum and 55% in S. lycopersicum in response to higher-level O3 exposure treatment (400-700 nmol mol-1). Despite of sharp decreases in gs, O3 uptake by the leaf (ϕLO3) increased in all three species (Fig. 2a) although the continuing decrease in gs at high O3 concentration eventually caused O3 uptake to level off and then decline in N. tabacum and S. lycopersicum. In P. vulgaris, the percentage of non-stomatal O3 uptake increased with rising O3 concentration (Fig. 2b). The changes in total O3 uptake and stomatal conductance (gs) during O3 fumigation in N. tabacum and S. lycopersicum were generally similar to P. vulgaris up to O3 concentration of 400 nmol mol-1. However, when O3 concentration was raised to 600 or 700 nmol mol-1 O3 uptake by the leaf (ϕLO3) and stomata (ϕGO3) started to decrease because of the lower stomatal conductance (Fig. 2). The percentage of non-stomatal O3 uptake (i.e., O3 removal at the leaf surface) in leaves of N. tabacum and S. lycopersicum declined somewhat over the course of the experiment as O3 concentrations increased (Fig. 2b). These responses were analogous in other species studied (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Ozone uptake flux by the entire leaf (ϕLO3) (a) and via the stomata (ϕGO3) (b) normalized to the uptake fluxes at applied O3 concentration of 100 nmol mol-1, stomatal conductance (gs; a) and percentage of O3 uptake by leaf surface (%; b) in relation to applied O3 concentration in P. vulgaris (upward pointed triangles), N. tabacum (hexagons) and S. lycopersicum (downward pointed triangles). Open and filled symbols in (a) correspond to whole leaf normalized O3 uptake flux (ϕLO3) and stomatal conductance (gs), and open and filled symbols in (b) to stomatal O3 uptake flux (ϕGO3) and percentage of O3 uptake by leaf surface (%), respectively. Error bars indicate ± SE.

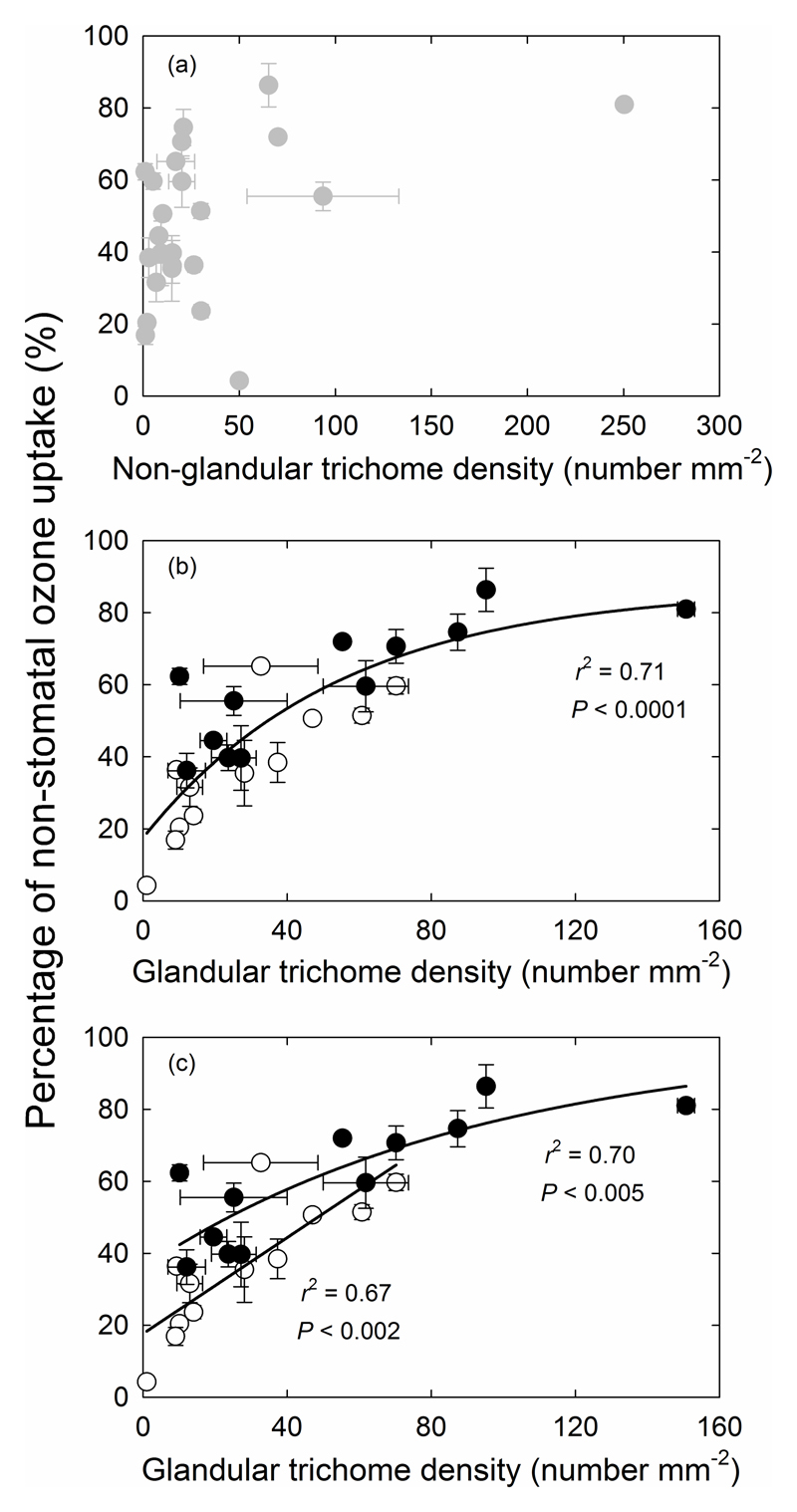

The relationships between non-stomatal O3 uptake and trichome types and density

There was no correlation between non-glandular trichome density and the percentage of non-stomatal O3 uptake (Fig. 3a), and we also found no correlation between the size (length and width) of non-glandular trichomes with the amount of non-stomatal O3 uptake (data not shown). In contrast, the glandular trichome density was strongly correlated with the percentage of non-stomatal O3 uptake (P < 0.0001; Fig. 3b). The correlations were even stronger when species with capitate glandular trichomes only and species with both peltate and capitate type glandular trichomes were examined separately although the latter group had overall greater non-stomatal O3 uptake (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Relationships between the percentage of non-stomatal ozone uptake and non-glandular trichome density (a), between the percentage of non-stomatal ozone uptake and glandular trichome density (b), and percentage of non-stomatal ozone uptake and glandular trichome density in species with capitate or both capitate and peltate trichomes (c). In (b) and (c), open symbols represent species with only capitate glandular trichomes and filled symbols species with both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes. The data in (b) were fitted by a non-linear regression (y=17.5+69.3(1-0.982x)) and in (c) by a linear regression, y=0.667x+17.7, for species with capitate glandular trichomes and by a non-linear regression, y=35.9+63.4(1-0.989x), for species with capitate and peltate glandular trichomes.

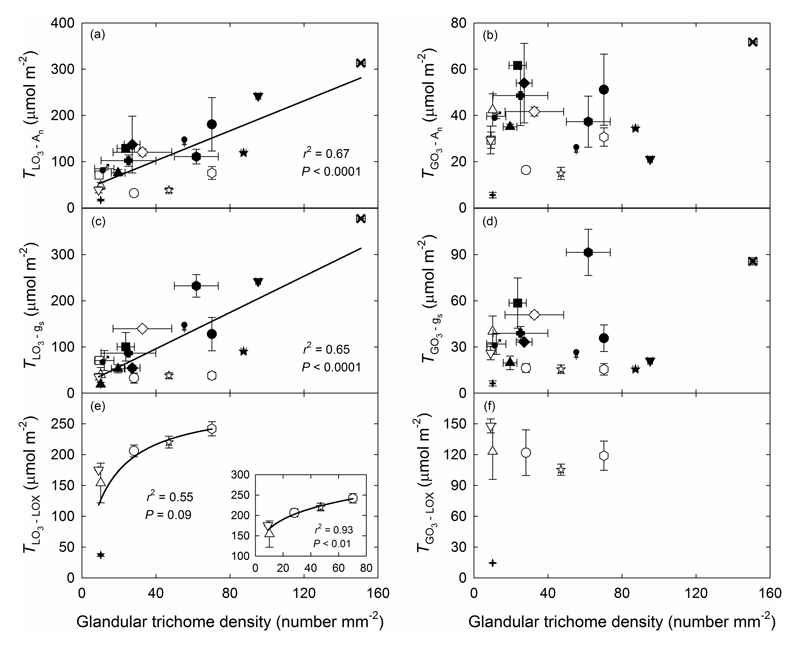

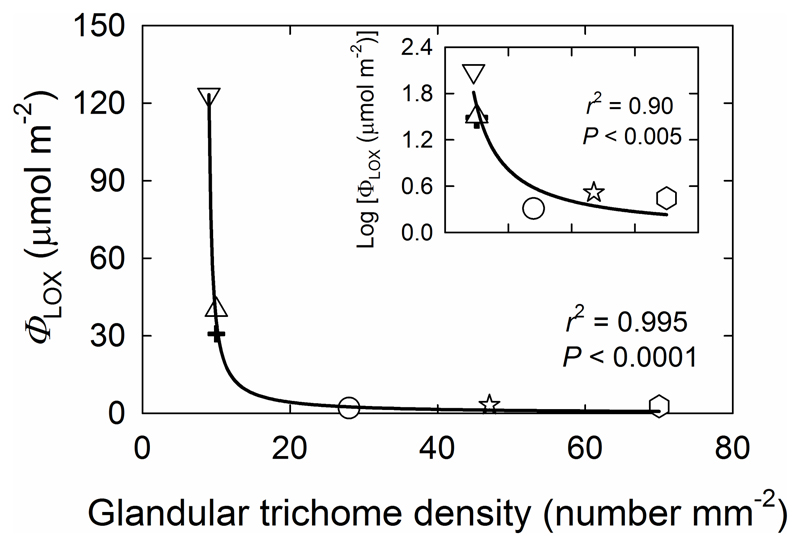

The glandular trichome density showed highly significant correlations with the threshold of total leaf O3 uptake that induced a sharp decrease in net assimilation rate and stomatal conductance (P < 0.0001; Fig. 4a,c), but it was not correlated with the threshold of total stomatal O3 uptake (Fig. 4b,d). In the case of induction of volatile LOX product emissions, glandular trichome density showed a non-significant correlation (P = 0.09) with the threshold of total leaf O3 uptake for all species pooled (Fig. 4e), but a significant correlation (P < 0.01) in the case of species with only capitate glandular trichomes (inset in Fig. 4e), and no significant correlation with the threshold of total stomatal O3 uptake (Fig. 4f). However, a significant negative relationship (P < 0.0001) between the total amount of volatile LOX pathway products released and glandular trichome density was observed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Correlations of average glandular trichome density with average physiological thresholds of O3 uptake by leaf (a, c, e) and stomata (b, d, f). The O3 uptake thresholds were defined as uptake values inducing a significant decrease of net assimilation rate (TLO3-An for leaf, and TGO3-An for stomatal uptake) and stomatal conductance (TLO3-gs, and TGO3-gs), and emissions of volatile products of the lipoxygenase pathway (LOX products, also called green leaf volatiles) (TLO3-LOX and TGO3-LOX). In (e), the inset does not include O. basilicum that had both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes. The data were fitted by linear or non-linear regressions (y=37.6+1.62x for (a); y=17.9+1.96x for (c), y=22.5x/(1+0.0788x) for (e, main panel) and y=108.1x0.188 for (e, inset)). B. pendula (filled circles, ●), C. sativus (open circles, ○), E. acer (open squares, □), E. canadensis (filled squares, ■), E. cicutarium (filled diamonds, ◆), G. palustre (open diamonds, ◇), G. pratense (filled hexagons, ⬢), G. robertianum (filled upward pointing triangles, ▲), L. angustifolia (filled downward pointing triangles, ▼), M. × piperita (filled stars, ★), N. tabacum (open hexagons, ⬡), O. basilicum (filled plus symbols, +), P. vulgaris (open upward pointing triangls, △), R. officinalis (filled crosses, ✖), S. officinalis (filled Venus symbols,  ), S. latifolia (filled Mars symbols,

), S. latifolia (filled Mars symbols,  ), S. lycopersicum (open downward pointing triangls, ▽), U. dioica (filled Christian crosses, ✚), V. thapsus (open stars, ☆). In all cases, open symbols represent species with only capitate glandular trichomes and filled symbols species with both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes. Error bars indicate ± SE.

), S. lycopersicum (open downward pointing triangls, ▽), U. dioica (filled Christian crosses, ✚), V. thapsus (open stars, ☆). In all cases, open symbols represent species with only capitate glandular trichomes and filled symbols species with both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes. Error bars indicate ± SE.

Fig. 5.

Total LOX product emissions (ΦLOX) over 21 hours following O3 exposure in relation to glandular trichome density for six species with different density of glandular trichomes. The y axis is Log10-transformed in the inset. In all cases, O3 concentration was increased in a stepwise fashion in 30 minute intervals, 100 nmol mol-1 increments, from 100 to 500 nmol mol-1. The data were fitted by a non-linear regression (y=-5.79/(1-0.116x) for the main panel, and y=16.8 * 106 /(1+ 10.3 * 105 x) for the inset). Symbols are as defined in Fig. 4.

Changes in physiological characteristics and LOX product emissions in response to O3 exposure in relation to glandular trichome density

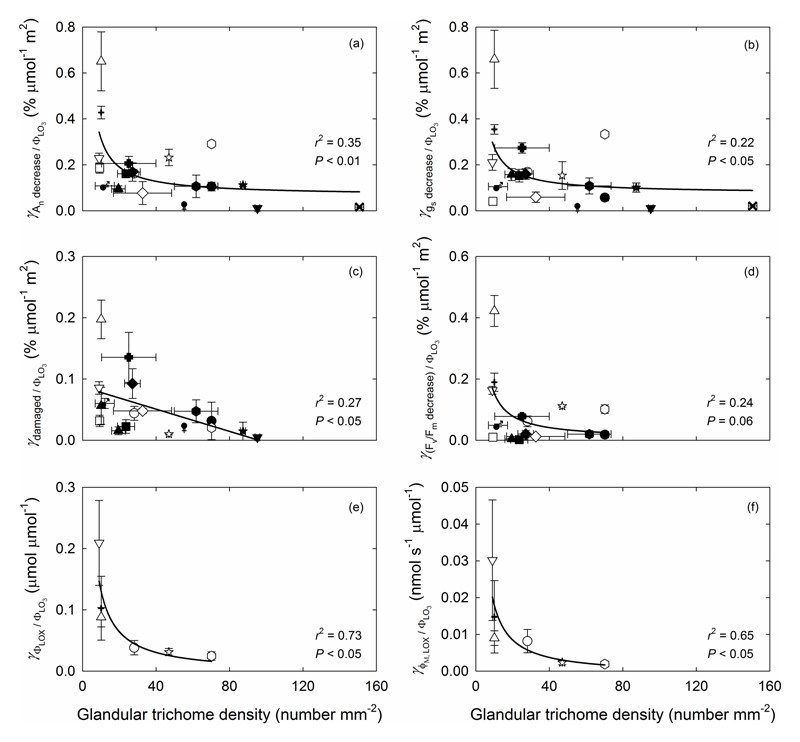

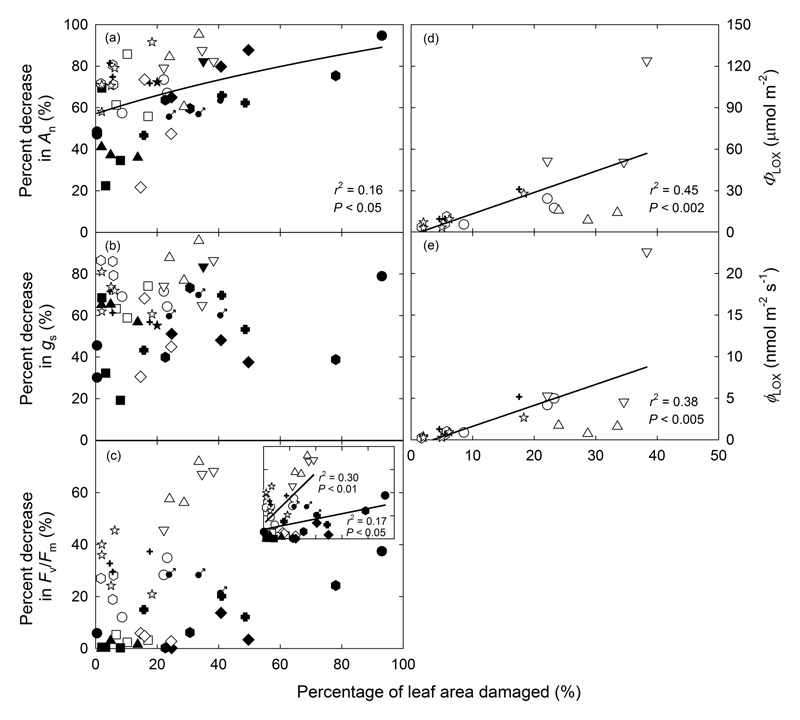

Both net assimilation rate (An) and stomatal conductance (gs) were significantly decreased after O3 exposure compared to the rates prior to O3 fumigation. O3-induced relative reductions in An and gs were strongly determined by glandular trichome density (P < 0.05; Fig. 6a,b). Visible leaf injury was also less in species with greater glandular trichome density at the same amount of leaf O3 uptake (P < 0.05; Fig. 6c). There was overall reduction of Fv/Fm per ppb O3 taken up by the leaf (O3 uptake weighted Fv/Fm, Eq. 8), but the correlation with glandular trichome density was not significant (Fig. 6d). Additionally, no significant correlations were observed between glandular trichome density and relative reduction in stomatal uptake weighted An, gs, Fv/Fm and visible leaf injury (Fig. S2a-d). However, glandular trichome density was negatively correlated with O3 uptake weighted total LOX product emission and maximum LOX product emission rate, regardless of whether the calculations were based on O3 taken up by the entire leaf (P < 0.05; Fig. 6e,f) or by stomata (P=0.05 and P=0.06, Fig. S2e,f), and the data were best fitted by nonlinear regressions (Fig. 6e,f and Fig. S2e,f). Across all treatments, visible leaf damage assessed at the end of the O3 exposure was a good indicator of reductions in foliage physiological characteristics and elicitation of LOX volatiles, except for reductions in stomatal conductance (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

(a) The percentage decrease in net assimilation rate (γAn decreased / ΦLO3), (b) the percentage decrease in stomatal conductance (γgs decreased / ΦLO3), (c) the percentage of leaf area visibly damaged (γ damaged / ΦLO3), (d) the percentage decrease in the dark-adapted maximum quantum efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm) (γ(Fv/Fm decreased / ΦLO3), (e) the induction of total amount of LOX product emission (γΦLOX / ΦLO3) and (f) the maximum rate of induced LOX product emission (γϕM, LOX / ΦLO3) per unit leaf O3 uptake (Eq. 8) in relation to glandular trichome density. As in Fig. 5, the total LOX product emission is the sum of LOX products released since the induction until termination of the experiment at 21 h after the stop of O3 exposure. Leaf damage after O3 fumigation was assessed as the presence of necrotic and/or chlorotic lesions on leaf surface. The data were fitted by linear or non-linear regressions (y=0.0662+(2.49/x) for (a); y=0.0755+(2.01/x) for (b); y=0.0871-0.000912x for (c); y=-0.00371+(1.50/x) for (d); y=-0.00332+(1.35/x) for (e) and y=-0.00112+(0.19/x)for (f)). Symbols as defined in Fig. 4. Error bars indicate ± SE.

Fig. 7.

Relative decreases in net assimilation rate (a) and stomatal conductance (b) and maximum dark-adapted quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) (c), and total emission of LOX products (d) and maximum emission rate of LOX products (e) in O3-exposed leaves in relation to the percentage of leaf area visibly damaged. The data were fitted by linear or non-linear regressions (y=-14.3+0.71.4(1+0.0188x)-0.366 for (a); y=1.54x-1.99 for (d) and y=0.252x-0.899 for (e)). The Data in the inset of (c) were fitted by linear regressions separately for species with only capitate trichomes (y=12.8+1.110x, open symbols) and with both capitate and peltate glandular trichomes (y=8.09+0.227x, filled symbols). Symbols as in Fig. 4.

Correlations among O3 uptake and leaf damage and with emissions of LOX products

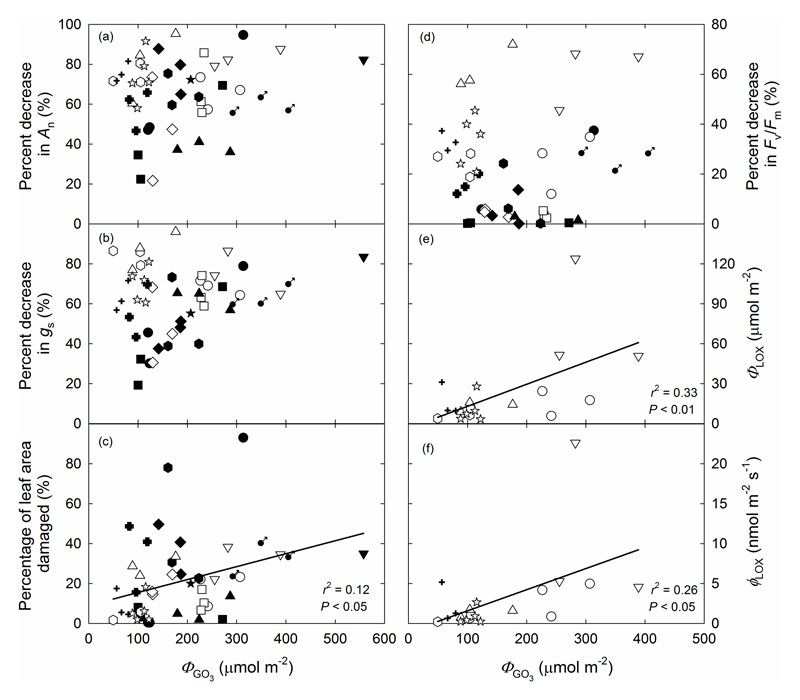

To estimate O3 damage across different species, we compared the correlations of modification in leaf physiological traits and leaf damage with O3 uptake by the whole leaf (ΦLO3), stomatal O3 uptake (ΦGO3) and non-stomatal O3 uptake (ΦNGO3). ΦLO3 was not correlated with the percentage of decrease in An, gs and Fv/Fm, but a significant positive correlation (P < 0.0005) with the percentage of visibly damaged leaf area was observed (Fig. S3a-d). Furthermore, ΦLO3 was also positively correlated with the total LOX product emission and maximum LOX product emission rate (P < 0.05; Fig. S3e,f). Apart from the protective role of glandular trichomes against O3 stress, the O3 dose ultimately entering into the leaf is crucial in understanding the magnitude of reductions in photosynthesis, appearance of visible lesions, and emission of LOX products. ΦGO3 was strongly correlated with the amount of visible leaf damage (P < 0.05; Fig. 8c), but there was no correlation between ΦGO3 and the percent decrease in An, gs or Fv/Fm (Fig. 8a,b,d). Furthermore, a positive non-linear relationship was found between ΦGO3 and both the total LOX product emission and maximum LOX product emission rate across the species (P < 0.05; Fig. 8e,f).

Fig. 8.

The total amount of O3 uptake by stomata (ΦGO3) in relation to the percentage decrease of net assimilation rate (a) and stomatal conductance (b), percentage leaf area visibly damaged (c) and percentage decrease of maximum dark-adapted chlorophyll fluorescence yield (Fv/Fm) (d), the total LOX product emission (e) and maximum emission rate of LOX products (f) from O3-exposed leaves. In (c), (e) and (f), the data were fitted by linear regressions (y=9.03+0.0648x; y=0.166x-3.58 and y=0.0265x-1.06). Symbols as in Fig. 4.

ΦNGO3 was not correlated with the percentage decrease in An, gs and Fv/Fm, and total amount of visible leaf damage and LOX product emissions (Fig. S4). Finally, the percentage of non-stomatal O3 uptake showed highly significant correlation with the percentage decrease in Fv/Fm (P < 0.005) but it was correlated with the percentage decrease in An and gs, amount of visible leaf damage and LOX product emissions (Fig. S5).

Discussion

Variation in trichome types and density across species

Non-glandular and glandular trichomes were found on the surfaces of all studied leaves. Specifically, two types of glandular trichomes on the surface were identified: peltate and capitate (Fig. 1). All species had capitate trichomes whereas peltate trichomes were observed only on the surface of 12 species. This agrees with previous observations by Glas et al. (2012), demonstrating more frequent occurrence of capitate glandular trichomes. According to past reports available for some of the species studied here, peltate and capitate trichome densities vary between 1-140 mm-2 (Wilkens et al., 1996; Ranger & Hower, 2001; Valkama et al., 2004; Kapoor et al., 2007; Lihavainen et al., 2017; Thitz et al., 2017). Correspondingly, the species studied here fell in the same range.

As outlined in the introduction, glandular and non-glandular trichomes play different roles in plant defense. Non-glandular trichomes are linked to mechanical defense against biotic and environmental stressors, while glandular trichomes produce metabolites for the alleviation of those stressors (Levin, 1973; Lihavainen et al., 2017). Glandular and non-glandular trichome density was not correlated suggesting that various selection pressures have occurred independently.

Glandular trichomes affect stomatal O3 uptake and increase the threshold of acute O3 responses

Stomata exert a strong control over leaf interior O3 concentrations and thus, play a major role in protecting leaves from O3 stress (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Li et al., 2017). Likewise, in this study, the step-wise increases in O3 concentration induced simultaneous stomatal closure (Fig. 2). In addition, data on non-stomatal O3 uptake (ΦNGO3) during the exposure revealed that O3 was significantly destroyed by leaf surface reactions. Factors that reduce O3 concentrations at leaf surface will reduce O3 entry into the leaf interior through the stomata and lower the effective O3 dose received by the plant. In our study, capitate and peltate glandular trichomes were both related to ΦNGO3 (Fig 3), whereas peltate glandular trichomes were more strongly related to reduced stomatal O3 uptake than capitate glandular trichomes, but surprisingly, non-glandular trichomes did not affect at all leaf O3 uptake.

Across species, a wide variety of metabolites are stored and exuded by glandular trichomes at the leaf surface (Rieseberg et al., 1987; Wagner, 1991; Fahn & Shimony, 1996; Heinrich et al., 2002; Amme et al., 2005; Peiffer et al., 2009; Agati et al., 2012; Jud et al., 2016; Lihavainen et al., 2017). It has been suggested that unsaturated semi-volatile compounds destroy O3 before it enters the leaf (Jud et al., 2016). Furthermore, high glandular trichome density is often associated with the presence of high concentrations of more volatile terpenoids, but also other non-volatile defense compounds such as acylated sugars and proteins (Gang et al., 2001; Amme et al., 2005). As different types of trichomes may have vastly different composition of secreted compounds (e.g. Fahn & Shimony, 1996; Heinrich et al., 2002; Amme et al., 2005; Kant et al., 2009; Jud et al., 2016), such differences among capitate and peltate glandular trichomes might reflect differences in the chemical reactivity with O3 of main chemical constituents synthesized in different trichomes. Peltate glandular trichomes are a major site of semi-volatile compound production and contain a much larger oil sac into which these compounds are secreted (e.g. Fahn, 1979; Gang et al., 2001; Amme et al., 2005). Nevertheless, tobacco lacks peltate trichomes, but in this species, the degree of non-stomatal O3 uptake also correlates strongly with the density of capitate trichomes and their exudates, indicating that capitate trichomes also contribute strongly to surface reactions with O3 (Jud et al., 2016). In fact, Jud et al. (2016) suggested that diterpenes exuded from tobacco trichomes were responsible for O3 quenching.

Non-glandular trichomes can form a dense indumentum on leaf surface that serve as a mechanical barrier against herbivores and pathogens (Eisner et al., 1998; Corsi & Bottega, 1999; Kennedy, 2003), but their role in antioxidative responses is less clear. Several species in our study had a massive amount of non-glandular trichomes (Table 1), but we found no correlation between the density of non-glandular trichomes with the amount of non-stomatal O3 uptake in the present study (Fig. 3a). This likely reflects the circumstance that non-glandular trichomes possess no secretory structures and are covered by a wax layer that consists of long-chained saturated oxygenated and non-oxygenated hydrocarbons (Corsi & Bottega, 1999) that have very low reactivity with O3.

O3 dose ultimately entering the plant interior is known to determine the amount of visible leaf damage, but in the case of mild O3 uptake not exceeding a certain O3 threshold, neither damage to the leaf biochemical apparatus nor induction of VOC emission have been observed (Nussbaum et al., 2001; Beauchamp et al., 2005; Velikova et al., 2005; Niinemets, 2010). In our study, we found a stronger relationship between glandular trichome density and the threshold for acute responses caused by O3 taken up by leaf than with that taken up through stomata (Fig. 4), indicating that trichome density promotes O3 tolerance of plants. However, once O3 enters the leaf, all species had similar threshold values regardless of trichome density. Moreover, the total emission of volatile LOX products was related to glandular trichome density under the same stepwise increase of O3 concentration and duration of fumigation (Fig. 5). By combining the correlations between glandular trichome density and non-stomatal O3 uptake, we have further demonstrated that glandular trichomes directly reduce O3 concentration at the leaf surface and thus indirectly reduce stomatal O3 uptake. While previously this has been shown for tobacco (Jud et al., 2016), our results extend this observation to a highly diverse set of plants with a large variability in trichome types, densities and likely also with exudates with highly diverse chemical nature. These results further confirm the previous suggestions that the plants’ acute responses are determined directly by O3 dose taken up by stomata (ΦGO3) (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Jud et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017), but also emphasize that these responses are importantly modified by glandular trichome density.

Effects of elevated O3 concentration on foliage photosynthetic characteristic and LOX product emission

Effects of elevated O3 concentration on plant growth, development, biodiversity, forest productivity and crop yields have been studied extensively in the last 30 years (Feng & Kobayashi, 2009; Ainsworth et al., 2012; Leisner & Ainsworth, 2012; Wilkinson et al., 2012; Fares et al., 2013; Ainsworth, 2017). The stepwise increase in O3 concentrations in this study caused reductions in net assimilation rates (An), stomatal conductance (gs) and Fv/Fm and induced formation and emission of LOX products, in agreement with previous reports for single species exposed to a given O3 concentration (Beauchamp et al., 2005; Chutteang et al., 2016; Li et al., 2017). We observed that there was a stronger relationship between the density of glandular trichomes and the absolute response per unit of O3 taken up by the whole leaf (i.e., through both surface reactions and via the stomata) than per unit of O3 taken up through the stomata (Fig. 6, S2), suggesting that trichomes provide protection against O3 damage on leaf surface. Furthermore, the evidence that visible leaf damage across species correlates more strongly with stomatal O3 uptake than with whole leaf O3 uptake (Fig. 8, S3) suggests that plant injuries are more strongly linked to the uptake of O3 through stomatal pores. These relationships clearly show that glandular trichomes directly reduce stomatal O3 uptake by depleting O3 at the leaf surface and thus indirectly alleviate O3 damage.

Given that glandular trichomes play multiple role in defence, the questions is whether the protection provided by glandular trichomes is directly driven by selection for greater oxidative stress resistance or whether it is primarily coincidential and reflects adaptation to other abiotic and biotic stresses. While the selection for atmospheric pollutant resistance was likely of minor significance in the past, human-driven pollution clearly increases the significance of selection for traits protecting against pollution and thus, the variation in glandular trichome density can importantly alter the fitness of given species in multispecies stands where different species exhibit differences in glandular trichome density. The fact that trichome number is not fixed at the time of leaf emergence and that trichome distribution changes with leaf position also implies that protection by glandular trichomes is a highly adaptive trait (Maffei et al., 1989; Prozhertina et al., 2003; Deschamps et al., 2006; Jud et al., 2016). Thus, the severity of abiotic and biotic stresses during leaf development can importantly alter leaf vulnerability to stress such as O3 during their lifetime (Jud et al., 2016), and further studies should examine whether long-term increases in atmospheric O3 concentration alter trichome density and the capacity for protection against atmospheric oxidants.

Although different species exhibited different O3 tolerance, O3-induced leaf damage occurred in all species (Fig. 7). The reductions in An and Fv/Fm and the induction of LOX product emissions were associated with O3-induced leaf damage across different species (Fig. 7). Such interspecific relationships have not been well studied, but finding uniform correlations across species suggests that the damage, once induced, alters foliage physiological characteristics similarly in all species. In previous studies, quantitative within-species relationships among LOX product emission and the severity of abiotic (Copolovici et al., 2012; Copolovici & Niinemets, 2016; Li et al., 2017) and biotic stresses (Niinemets et al., 2013) have been observed. The interspecific correlations with the degree of damage observed in our study provide also encouraging evidence that not only modifications in foliage photosynthetic characteristics, but also LOX product emissions can provide a quantitative measure to estimate the deleterious effects of O3 across species.

Conclusions

Our study provides conclusive evidence that glandular trichomes play a protective role against O3 stress, and that this protection is associated with the type and density of glandular trichomes across a highly diverse set of species. A stepwise increase in O3 concentration during fumigation led to severe visible leaf injury, and reductions in maximum quantum yield of PSII, leaf net assimilation rate and stomatal conductance, and increase in emissions of volatile products of lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway. We demonstrated that the presence of both peltate and capitate glandular trichomes are strongly related to reduced stomatal O3 uptake. Because glandular trichomes reduce O3 concentrations surrounding the open stomata on leaf surface, the O3 dose threshold triggering acute responses increased with increasing glandular trichome density. In addition, absolute differences in leaf damage and LOX product emissions caused by leaf O3 uptake were strongly linked to glandular trichome density. In summary, our study demonstrates that species with low glandular trichome density were more sensitive to O3 stress compared to species with high trichome density, suggesting that leaf trichominess might importantly drive species dispersal in polluted environments. Further work is needed to gaining an insight into the distribution of species with different level of glandular trichome density in different communities and to understanding how various types of glandular trichomes containing different organic compounds affect plant O3 resistance.

Supplementary Material

Summary Statement.

Glandular and non-glandular trichomes are widely distributed on leaf surfaces, but the role of different trichome types and trichome density in protection from atmospheric oxidative stress is poorly understood. This study analyzed ozone stress resistance of photosynthesis and induction of stress volatiles in 24 species with widely varying trichome characteristics and taxonomy, and demonstrated that the presence of glandular trichomes strongly reduced stomatal ozone uptake and ozone-dependent damage. This highlights a key role of glandular trichomes in maintenance and physiological homeostasis under atmospheric oxidative stress.

Acknowledgments

We thank Märt Rahi for the help with SEM analyses. This work was supported by grants from the European Research Council (advanced grant 322603, SIP-VOL+), the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence EcolChange), and the Estonian Ministry of Science and Education (institutional grant IUT-8-3) and personal investigator grant PUT 1473. This manuscript greatly benefited from the comments of two anonymous reviewers and the Handling Editor, Lisa Ainsworth.

Footnotes

ORCID:

Shuai Li: 0000-0003-2545-7763

Arooran Kanagendran: 0000-0002-4302-1536

Ülo Niinemets: 0000-0002-3078-2192

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agati G, Azzarello E, Pollastri S, Tattini M. Flavonoids as antioxidants in plants: location and functional significance. Plant Science. 2012;196:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA. Understanding and improving global crop response to ozone pollution. The Plant Journal. 2017;90:886–897. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Yendrek CR, Sitch S, Collins WJ, Emberson LD. The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2012;63:637–661. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amme S, Rutten T, Melzer M, Sonsmann G, Vissers JPC, Schlesier B, Mock H-P. A proteome approach defines protective functions of tobacco leaf trichomes. Proteomics. 2005;5:2508–2518. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ascensão L, Marques N, Pais MS. Glandular trichomes on vegetative and reproductive organs of Leonotis leonurus (Lamiaceae) Annals of Botany. 1995;75:619–626. [Google Scholar]

- Ascensão L, Pais MS. The leaf capitate trichomes of Leonotis leonurus: histochemistry, ultrastructure and secretion. Annals of Botany. 1998;81:263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Baran P, Özdemir C, Aktaş K. Structural investigation of the glandular trichomes of Salvia argentea . Biologia. 2010;65:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Beauchamp J, Wisthaler A, Hansel A, Kleist E, Miebach M, Niinemets Ü, et al. Wildt J. Ozone induced emissions of biogenic VOC from tobacco: relationships between ozone uptake and emission of LOX products. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2005;28:1334–1343. [Google Scholar]

- Brilli F, Ruuskanen TM, Schnitzhofer R, Müller M, Breitenlechner M, Bittner V, et al. Hansel A. Detection of plant volatiles after leaf wounding and darkening by Proton Transfer Reaction “Time-of-Flight” Mass Spectrometry (PTR-TOF) PLoS One. 2011;6:e20419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosché M, Merilo E, Mayer F, Pechter P, Puzõrjova I, Brader G, Kangasjärvi J, Kollist H. Natural variation in ozone sensitivity among Arabidopsis thaliana accessions and its relation to stomatal conductance. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2010;33:914–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussotti F, Desotgiu R, Cascio C, Pollastrini M, Gravano E, Gerosa G, et al. Strasser RJ. Ozone stress in woody plants assessed with chlorophyll a fluorescence. A critical reassessment of exiting data. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2011;73:19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cescatti A, Niinemets Ü. Sunlight capture. Leaf to landscape. In: Smith WK, Vogelmann TC, Chritchley C, editors. Photosynthetic adaptation. Chloroplast to landscape. Springer Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 2004. pp. 42–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cho K, Tiwari S, Agrawal SB, Torres NL, Agrawal M, Sarkar A, et al. Rakwal R. Tropospheric ozone and plants: absorption, responses, and consequence. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 2011;212:61–111. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8453-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chutteang C, Booker FL, Na-Ngern P, Burton A, Aoki M, Burkey KO. Biochemical and physiological processes associated with the differential ozone response in ozone-tolerant and sensitive soybean genotypes. Plant Biology. 2016;18:28–36. doi: 10.1111/plb.12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copolovici L, Kännaste A, Pazouki L, Niinemets Ü. Emissions of green leaf volatiles and terpenoids from Solanum lycopersicum are quantitatively related to the severity of cold and heat shock treatments. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2012;169:664–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copolovici L, Niinemets Ü. Flooding induced emissions of volatile signaling compounds in three tree species with differing waterlogging tolerance. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2010;33:1582–1594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copolovici L, Niinemets Ü. Environmental impacts on plant volatile emission. In: Blande J, Glinwood R, editors. Deciphering chemical language of plant communication. Springer International Publishing; Berlin, Germany: 2016. pp. 35–59. [Google Scholar]

- Corsi G, Bottega S. Glandular hairs of Salvia officinalis: new data on morphology, localization and histochemistry in relation to function. Annals of Botany. 1999;84:657–664. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps C, Gang D, Dudareva N, Simon JE. Developmental regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in leaves and glandular trichomes of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) International Journal of Plant Sciences. 2006;167:447–454. [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J. Leaf absorptances of Mohave and Sonoran desert plants. Oecologia. 1981;49:366–370. doi: 10.1007/BF00347600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J. The influence of water stress and temperature on leaf pubescence development in Encelia farinosa . American Journal of Botany. 1982;69:670–675. [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J, Björkman O, Mooney HA. Leaf pubescence: effects on absorptance and photosynthesis in a desert shrub. Science. 1976;192:376–377. doi: 10.1126/science.192.4237.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisner T, Eisner M, Hoebeke ER. When defense backfires: detrimental effect of a plant’s protective trichomes on an insect beneficial to the plant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:4410–4414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A. Secretory Tissues in Plants. Academic Press; London, UK: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A, Shimony C. Glandular trichomes of Fagonia L. (Zygophyllaceae) species: structure, development and secreted materials. Annals of Botany. 1996;77:25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fares A, Vargas R, Detto M, Goldstein AH, Karlik J, Paoletti E, Vitale M. Tropospheric ozone reduces carbon assimilation in trees: estimates from analysis of continuous flux measurements. Global Change Biology. 2013;19:2427–2443. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Kobayashi K. Assessing the impacts of current and future concentrations of surface ozone on crop yield with meta-analysis. Atmospheric Environment. 2009;43:1510–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Büker P, Pleijel H, Emberson L, Karlsson PE, Uddling J. A unifying explanation for variation in ozone sensitivity among woody plants. Global Change Biology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/gcb.13824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscus EL, Booker FL, Burkey KO. Crop responses to ozone: uptake, models of action, carbon assimilation and partitioning. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2005;28:997–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Flowers MD, Fiscus EL, Burkey KO, Booker FL, Dubois J-JB. Photosynthesis, chlorophyll fluorescence, and yield of snap bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) genotypes differing in sensitivity to ozone. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2007;61:190–198. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler D, Amann M, Anderson R, Ashmore M, Cox P, Depledge M, et al. Stevenson D. Ground-level ozone in the 21st century: future trends, impacts and policy implications. The Royal Society; London, UK: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Franzaring J, Dueck TA, Tonneijck AEG. Can plant traits be used to explain differences in ozone sensitivity between native European species? In: Fuhrer J, Achermann B, editors. Critical levels for ozone-level II. Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape; Bern, Switzerland: 1999. pp. 271–274. [Google Scholar]

- Gang DR, Wang J, Dudareva N, Nam KH, Simon JE, Lewinsohn E, Pichersky E. An investigation of the storage and biosynthesis of phenylpropenes in sweet basil. Plant Physiology. 2001;125:539–555. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zhu B, Xiao H, Kang H, Hou X, Shao P. A case study of surface ozone source apportionment during a high concentration episode, under frequent shifting wind conditions over the Yangtze River Delta, China. Science of the Total Environment. 2016;544:853–863. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glas JJ, Schimmel BCJ, Alba JM, Escobar-Bravo R, Schuurink RC, Kant MR. Plant glandular trichomes as targets for breeding or engineering of resistance to herbivores. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012;13:17077–17103. doi: 10.3390/ijms131217077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graus M, Müller M, Hansel A. High resolution PTR-TOF: quantification and formula confirmation of VOC in real time. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2010;21:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallik L, Kazantsev T, Kuusk A, Galmés J, Tomás M, Niinemets Ü. Generality of relationships between leaf pigment contents and spectral vegetation indices in Mallorca (Spain) Regional Environmental Change. 2017;17:2097–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann DL, Klein Tank AMG, Rusticucci M, Alexander LV, Brönnimann S, Charabi YAR, et al. Zhai P. Observations: Atmosphere and Surface. In: Stocker TF, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen SK, Boschung J, et al.Midgley PM, editors. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes F, Jones MLM, Mills G, Ashmore M. Meta-analysis of the relative sensitivity of semi-natural vegetation species to ozone. Environmental Pollution. 2007;146:754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiden AC, Hoffmann T, Kahl J, Kley D, Klockow D, Langebartels C, et al. Wildt J. Emission of volatile organic compounds from ozone-exposed plants. Ecological Applications. 1999;9:1160–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich G, Pfeifhofer HW, Stabentheiner E, Sawidis T. Glandular hairs of Sigesbeckia jorullensis Kunth (Asteraceae): morphology, histochemistry and composition of essential oil. Annals of Botany. 2002;89:459–469. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huci P, Beversdorf WD, McKersie BD. Relationship of leaf parameters with genetic ozone insensitivity in selected Phaseolus vulgaris cultivars. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1982;60:2187–2191. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan A, Haidacher S, Hanel G, Hartungen E, Märk L, Seehauser H, et al. Märk TD. A high resolution and high sensitivity proton-transfer-reaction time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PTR-TOF-MS) International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2009;286:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Jud W, Fischer L, Canaval E, Wohlfahrt G, Tissier A, Hansel A. Plant surface reactions: an opportunistic ozone defence mechanism impacting atmospheric chemistry. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics. 2016;16:277–292. [Google Scholar]

- Kanagendran A, Pazouki L, Li S, Liu B, Kännaste A, Niinemets Ü. Stress volatile emissions upon acute ozone exposure scale with foliage surface ozone uptake in ozone-resistant Nicotiana tabacum ‘Wisconsin’. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2017 doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kant MR, Bleeker PM, Van Wijk M, Schuurink RC, Haring MA. Plant volatiles in defence. In: Van Loon LC, editor. Advances in botanical research (volume 51. plant Innate Immunity) Academic press; VT, USA: 2009. pp. 613–666. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor R, Chaudhary V, Bhatnagar AK. Effects of arbuscular mycorrhiza and phosphorus application on artemisinin concentration in Artemisia annua L. Mycorrhiza. 2007;17:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s00572-007-0135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy GG. Tomato, pests, parasitoids, and predators: tritrophic interactions involving the genus Lycopersicon. Annual Review of Entomology. 2003;48:51–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko KN, Lee KW, Lee SE, Kim ES. Development and ultrastructure of glandular trichomes in pelargonium x fragrans ‘mabel grey’ (geraniaceae) Journal of Plant Biology. 2007;50:362–368. [Google Scholar]

- Kostina E, Wulff A, Julkunen-Tiitto R. Growth, structure, stomatal responses and secondary metabolites of birch seedlings (Betula pendula) under elevated UV-B radiation in the field. Trees. 2001;15:483–491. [Google Scholar]

- Lai T-L, Talbot R, Mao H. An investigating of two highest ozone episodes during the last decade in New England. Atmosphere. 2012;3:59–86. [Google Scholar]

- Laisk A, Kull O, Moldau H. Ozone concentration in leaf intercellular air spaces is close to zero. Plant Physiology. 1989;90:1163–1167. doi: 10.1104/pp.90.3.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leisner CP, Ainsworth EA. Quantifying the effects of ozone on plant reproductive growth and development. Global Change Biology. 2012;18:606–616. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. The role of trichomes in plant defense. Quarterly Review of Biology. 1973;48:3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Calatayud V, Gao F, Uddling J, Feng Z. Differences in ozone sensitivity among woody species are related to leaf morphology and antioxidant levels. Tree Physiology. 2016;36:1105–1116. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpw042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Harley PC, Niinemets Ü. Ozone-induced foliar damage and release of stress volatiles is highly dependent on stomatal openness and priming by low-level ozone exposure in Phaseolus vulgaris. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2017;40:1984–2003. doi: 10.1111/pce.13003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lihavainen J, Ahonen V, Keski-Saari S, Sõber A, Oksanen E, Keinänen M. Low vapor pressure deficit reduces glandular trichomes density and modifies the chemical composition of cuticular waxes in silver birch leaves. Tree Physiology. 2017;37:1166–1181. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpx045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan JA, Staehelin J, Megretskaia IA, Cammas J-P, Thouret V, Claude H, et al. Derwent R. Changes in ozone over Europe: analysis of ozone measurements from sondes, regular aircraft (MOZAIC) and alpine surface sites. Journal of Geophysical Research. 2012;117 D09301. [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Schnitzler J-P. Abiotic stresses and induced BVOCs. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei M, Chialva F, Sacco T. Glandular trichomes and essential oil in developing peppermint leaves. New Phytologist. 1989;111:707–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1989.tb02366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldau H, Bichele I. Plasmalemma protection by the apoplast as assessed from above-zero ozone concentrations in leaf intercellular air spaces. Planta. 2002;214:484–487. doi: 10.1007/s00425-001-0678-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü. Mild versus severe stress and BVOCs: thresholds, priming and consequences. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Fares S, Harley P, Jardine KJ. Bidirectional exchange of biogenic volatiles with vegetation: emission sources, reactions, breakdown and deposition. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2014;37:1790–1809. doi: 10.1111/pce.12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Kännaste A, Copolovici L. Quantitative patterns between plant volatile emissions induced by biotic stresses and the degree of damage. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2013;4:262. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü, Kuhn U, Harley PC, Staudt M, Arneth A, Cescatti A, et al. Peñuelas J. Estimations of isoprenoid emission capacity from enclosure studies: measurements, data processing, quality and standardized measurement protocols. Biogeosciences. 2011;8:2209–2246. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum S, Geissmann M, Eggenberg P, Strasser RJ, Fuhrer J. Ozone sensitivity in herbaceous species as assessed by direct and modulated chlorophyll fluorescence techniques. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2001;158:757–766. [Google Scholar]

- Oltmans SJ, Lefohn AS, Shadwick D, Harris JM, Scheel HE, Galbally I, et al. Kawasato T. Recent tropospheric ozone changes- a pattern dominated by slow or no growth. Atmospheric Environment. 2013;67:331–351. [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti E, Seufert G, Della Rocca G, Thomsen H. Photosynthetic responses to elevated CO2 and O3 in Quercus ilex leaves at a natural CO2 spring. Environmental Pollution. 2007;147:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualini S, Piccioni C, Reale L, Ederli L, Della Torre G, Ferranti F. Ozone-induced cell death in tobacco cultivar Bel W3 plant. The role of programmed cell death in lesion formation. Plant Physiology. 2003;133:1122–1134. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peiffer M, Tooker JF, Luthe DS, Felton GW. Plants on early alert: glandular trichomes as sensors for insect herbivores. New Phytologist. 2009;184:644–656. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo-Estrada M, Kazantsev T, Talts E, Tosens T, Niinemets Ü. Emission timetable and quantitative patterns of wound-induced volatiles across different leaf damage treatments in aspen (Populus tremula) Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2015;41:1105–1117. doi: 10.1007/s10886-015-0646-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prozherina N, Freiwald V, Rousi M, Oksanen E. Interactive effect of springtime frost and elevated ozone on early growth, foliar injuries and leaf structure of birch (Betula pendula) New Phytologist. 2003;159:623–636. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranger CM, Hower AA. Glandular morphology from a perennial alfalfa clone resistant to the potato leafhopper. Crop Science. 2001;41:1427–1434. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Soltis DE, Arnold D. Variation and localization of flavonoid aglycones in Helianthus annuus (Compositae) American Journal of Botany. 1987;74:224–233. [Google Scholar]

- Riikonen J, Percy KE, Kivimäenpää M, Kubiske ME, Nelson ND, Vapaavuori E, Karnosky DF. Leaf size and surface characteristics of Betula papyrifera expose to elevated CO2 and O3. Environmental Pollution. 2010;158:1029–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallaud C, Giacalone C, Töpfer R, Goepfert S, Bakaher N, Rösti S, Tissier A. Characterization of two genes for the biosynthesis of the labdane diterpene Z-abienol in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) glandular trichomes. Plant Journal. 2012;72:1–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thitz P, Possen BJHM, Oksanen E, Mehtätalo L, Virjamo V, Vapaavuori E. Production of glandular trichomes responds to water stress and temperature in silver birch (Betula pendula) leaves. Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 2017;47:1075–1081. [Google Scholar]

- Valkama E, Salminen J-P, Koricheva J, Pihlaja K. Changes in leaf trichomes and epicuticular flavonoids during leaf development in three birch taxa. Annals of Botany. 2004;94:233–242. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velikova V, Tsonev T, Pinelli P, Alessio GA, Loreto F. Localized ozone fumigation system for studying ozone effects on photosynthesis, respiration, electron transport rate and isoprene emission in field-grown Mediterranean oak species. Tree Physiology. 2005;25:1523–1532. doi: 10.1093/treephys/25.12.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vingarzan R. A review of surface ozone background levels and trends. Atmospheric Environment. 2004;38:3431–3442. [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta. 1981;153:376–387. doi: 10.1007/BF00384257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ. Secreting glandular trichomes: more than just hairs. Plant Physiology. 1991;96:675–679. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Wang E, Shepherd RW. New approaches for studying and exploiting an old protuberance, the plant trichomes. Annals of Botany. 2004;93:3–11. doi: 10.1093/aob/mch011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth H, Mittelstrass K, Kschieschan S, Bender J, Weigel H-J, Overmyer K, et al. Langebartels C. Activation of an oxidative burst is a general feature of sensitive plants exposed to the air pollutant ozone. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2002;25:717–726. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens RT, Shea GO, Halbreich S, Stamp NE. Resource availability and the trichome defenses of tomato plants. Oecologia. 1996;106:181–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00328597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S, Mills G, Illidge R, Davies WJ. How is ozone pollution reducing our food supply? Journal of Experimental Botany. 2012;63:527–536. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Calatayud V, Jiang L, Manning WJ, Hayes F, Tian Y, Feng Z. Assessing the effects of ambient ozone in China on snap bean genotypes by using ethylenediurea (EDU) Environmental Pollution. 2015;205:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2015.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.