Abstract

The 14-3-3 proteins are a family of proteins that are highly expressed in the brain and particularly enriched at synapses. Evidence accumulated in the last two decades has implicated 14-3-3 proteins as an important regulator of synaptic transmission and plasticity. Here, we will review previous and more recent research that has helped us understand the roles of 14-3-3 proteins at glutamatergic synapses. A key challenge for the future is to delineate the 14-3-3-dependent molecular pathways involved in regulating synaptic functions.

1. Introduction

14-3-3 refers to a family of homologous proteins that consist of seven genetic loci or isoforms (β, γ, ε, η, σ, ζ, and τ) in vertebrates. The name 14-3-3 was given based on the fraction number and migration position on DEAE-cellulose chromatography and subsequent starch-gel electrophoresis during its initial biochemical purification process [1]. 14-3-3 proteins exist as homo- or heterodimers, in which each 14-3-3 monomer shares a similar helical structure and forms a conserved concave amphipathic groove that binds to target proteins via specific phosphoserine/phosphothreonine-containing motifs [2–7]. Through protein-protein interactions, 14-3-3 functions by altering the conformation, stability, subcellular localization, or activity of its binding partners. To date, 14-3-3 proteins have been shown to interact with hundreds of proteins and are implicated in the regulation of a multitude of cellular processes [8, 9].

14-3-3 proteins are highly expressed in the brain, comprising ~1% of its total soluble proteins. Thus, it comes to no surprise that 14-3-3 proteins are involved in a variety of neuronal processes, such as neurite outgrowth, neural differentiation, migration and survival, ion channel regulation, receptor trafficking, and neurotransmitter release [10–12]. In addition, 14-3-3 proteins are genetically linked to several neurological disorders, including neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseases), neurodevelopmental diseases (e.g., Lissencephaly), and neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) [13–15], thus making them a potential therapeutic target [16, 17]. In recent years, a number of small molecule 14-3-3 modulators have been discovered that could be used to either stabilize or inhibit 14-3-3 protein-protein interactions [18, 19]. However, as 14-3-3 proteins are involved in diverse cellular processes, it is highly desirable to further characterize and develop compounds that have enhanced isoform specificity as well as can selectively modulate the 14-3-3 interaction with a critical target in a particular pathway.

14-3-3 proteins are generally found in the cytoplasmic compartment of eukaryotic cells. In mature neurons, however, certain 14-3-3 isoforms are particularly enriched at synapses, suggesting their potential involvement in synaptic transmissions [20, 21]. Indeed, evidence accumulated in the last two decades reveals that 14-3-3 is an important modulator of synaptic neurotransmissions and plasticity. In this review, we will discuss the functional role of 14-3-3 proteins in the regulation of glutamatergic synapses.

2. Functions of 14-3-3 at the Presynaptic Site

Early evidence that 14-3-3 might regulate synaptic transmission and plasticity came from genetic and functional studies of the fruit fly Drosophila. The gene leonardo encodes 14-3-3ζ, one of the two Drosophila 14-3-3 homologs that is abundantly and preferentially expressed in mushroom body neurons. Mutant leo alleles with reduced 14-3-3ζ proteins exhibit significant deficits in olfactory learning and memory, suggesting a functional role of 14-3-3 in these processes [22]. A subsequent study further determined that the 14-3-3ζ protein progressively accumulates to the synaptic boutons during maturation of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ), where it colocalizes with the synaptic vesicles containing the neurotransmitter glutamate [23]. Based on electrophysiological analyses, Leonardo mutants show impaired presynaptic functions at NMJ, including reduced endogenous excitatory junctional currents (EJCs), impaired transmission fidelity, and loss of long-term augmentation and posttetanic potentiation (PTP). The evoked transmission deficit in leo is more severe under lower external Ca2+ concentration, suggesting a possible defect in Ca2+-dependent presynaptic transmission in the absence of 14-3-3ζ proteins.

Following those studies in Drosophila NMJs, the involvement of 14-3-3 proteins in the presynaptic site of glutamatergic synapses was further investigated in the vertebrate nervous system. One potential mechanism is thought to be mediated by 14-3-3 binding to RIM1α, an active zone protein that is essential for presynaptic short- and long-term plasticity [24, 25]. Early biochemical studies have provided the first evidence that 14-3-3 binds to RIM1α through its N terminal domain, raising the possibility that 14-3-3 regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic plasticity through the regulation of RIM1α [26]. A later study further confirmed this protein-protein interaction and identified that PKA phosphorylation of serine-413 at RIM1α (pSer413) is critical for 14-3-3 binding [27]. Moreover, electrophysiological assays in cultured cerebellar neurons suggested that recruitment of 14-3-3 to RIM1α at pSer413 is required for a presynaptic form of long-term potentiation (LTP) at granule cell and Purkinje cell synapses in the mouse cerebellum [27–29]. However, apparently contradictory evidence came from later efforts to examine the involvement of 14-3-3 and RIM1α interaction in presynaptic long-term plasticity using in vivo animal models. In one of these studies, a line of knock-in mice was generated to substitute RIM1α serine-413 with alanine (S413A), thereby abolishing RIM1α phosphorylation at S413 and 14-3-3 binding. Surprisingly, electrophysiological examination of the RIM1α S413A knock-in mice failed to detect a significant defect in presynaptic LTP, either at parallel fiber or mossy fiber synapses [30]. In agreement with this finding, an acute in vivo rescue experiment showed that deficits of mossy fiber LTP in RIM1α−/− mice can be rescued by expression of the phosphorylation site-deficient mutant of RIM1α (S413A) [31]. Thus, it remains unclear whether 14-3-3 binding to S413 phosphorylated RIM1α plays a significant role in the regulation of presynaptic long-term plasticity.

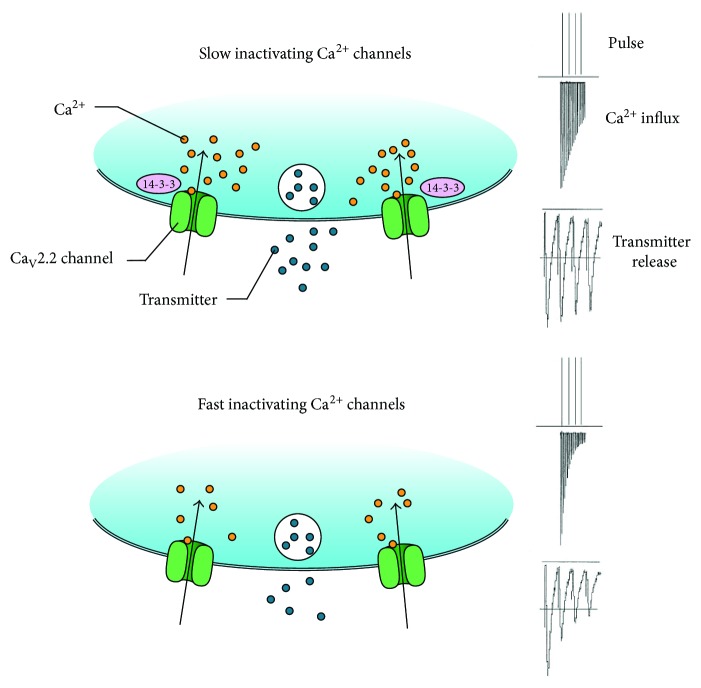

A better-understood action of 14-3-3 at the presynaptic site is its role as the modulator of ion channels [32, 33], which include voltage-gated calcium (Ca2+) channels that play a central role in neurotransmitter release by mediating Ca2+ influx at nerve terminals [34]. In particular, CaV2.2 channels undergo cumulative inactivation after a brief, repetitive depolarization, thus markedly impacting the fidelity of synaptic transmission and short-term synaptic plasticity [35, 36]. 14-3-3 modulates inactivation properties of CaV2.2 channels through its direct binding to the channel pore-forming α1B subunit. In cultured rat hippocampal neurons, inhibition of 14-3-3 proteins in presynaptic neurons augments short-term depression, likely through promoting the closed-state inactivation of CaV2.2 channels (Figure 1) [37]. As 14-3-3 binding can be regulated by specific phosphorylation of the α1B subunit, this regulatory protein complex may provide a potential mechanism for phosphorylation-dependent regulation of short-term synaptic plasticity.

Figure 1.

14-3-3 regulates presynaptic short-term plasticity by modulating CaV2.2 channel properties. 14-3-3 binding reduces cumulative inactivation of CaV2.2 channels and sustains Ca2+ influx and neurotransmitter release (a). Inhibition of 14-3-3 accelerates CaV2.2 channel inactivation and enhances short-term synaptic depression (b).

3. Functions of 14-3-3 at the Postsynaptic Site

The role of 14-3-3 at the postsynaptic site emerged more recently from the studies of various 14-3-3 mouse models. One of them, the 14-3-3 functional knockout (FKO) mice, was generated by transgenic expression of difopein (dimeric fourteen-three-three peptide inhibitor) that antagonizes the binding of 14-3-3 proteins to their endogenous partners in an isoform-independent manner, thereby disrupting 14-3-3 functions [38–41]. Transgene expression is driven by the neuronal-specific Thy-1 promoter which produces variable expression patterns in the brains of different founder lines, making it possible to assess the behavioral and synaptic alterations associated with expression of the 14-3-3 inhibitor in certain brain regions [42, 43]. Inhibition of 14-3-3 proteins in the hippocampus impairs associative learning and memory behaviors and suppresses long-term potentiation (LTP) at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses of the 14-3-3 FKO mice [41]. Through comparative analyses of two different founder lines with distinct transgene expression patterns in the subregions of the hippocampus, it was further determined that postsynaptic inhibition of 14-3-3 proteins may contribute to the impairments in LTP and cognitive behaviors. These observations thus revealed a postsynaptic function for 14-3-3 proteins in regulating long-term synaptic plasticity in mouse hippocampus.

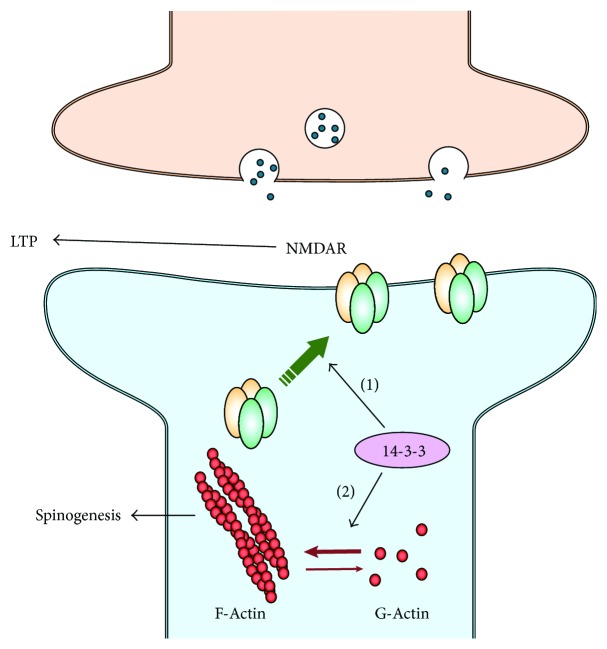

What might be the molecular targets of 14-3-3 proteins at the postsynaptic site of hippocampal synapses? In the 14-3-3 FKO mice, there is a significant reduction of the NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic currents in CA1 pyramidal neurons which express the 14-3-3 inhibitor. Consistently, the level of NMDA receptors (NMDARs), particularly GluN1 and GluN2A subunits, is selectively reduced in the postsynaptic density (PSD) fraction of 14-3-3 FKO mice that exhibit deficits in cognitive behaviors and hippocampal LTP [41]. Considering the critical role that NMDARs play in mediating LTP at hippocampal CA3-CA1 synapses [44], 14-3-3 proteins likely exert their effects on postsynaptic sites through the regulation of NMDA receptors, either directly or indirectly (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

14-3-3 regulates NMDA receptors and actin dynamics at postsynaptic sites. (1) 14-3-3 proteins facilitate targeting of NMDARs to the postsynaptic density, thereby regulating long-term potentiation; (2) 14-3-3 proteins might promote spinogenesis by facilitating F-actin formation.

NMDARs are heterotetramers composed of two obligatory GluN1 subunits and two regulatory subunits derived from GluN (GluN2A-2D) and GluN3 subunits [45, 46]. 14-3-3 is known to promote surface expression of NMDA receptors in cerebellar neurons through its interaction with PKB-phosphorylated GluN2C subunits [47]. A more recent study also showed that inhibiting endogenous 14-3-3 proteins using difopein greatly attenuate GluN2C surface expression in cultured hippocampal neurons [48]. However, it remains to be determined whether 14-3-3 proteins directly interact with other subunits of NMDAR and have similar effects on their surface expression. Alternatively, 14-3-3 might indirectly regulate the PSD level of NMDARs by modulating other critical steps of NMDAR synaptic trafficking, such as dendritic transport and synaptic localization [45, 49]. Therefore, further studies are needed to better understand the exact mechanism underlying 14-3-3 proteins' regulation of NMDA receptors. Interestingly, the synaptic level of certain 14-3-3 isoforms is reduced in GluN1 knockdown mice, but not by subchronic administration of an NMDAR antagonist in wild-type mice [50]. It raises a possibility that a reciprocal regulation between 14-3-3 and NMDARs may take place at the postsynaptic site.

14-3-3 proteins also modulate other glutamate receptors at the postsynaptic membrane. For example, 14-3-3 interacts with GluK2a, a subunit of the kainate receptor (KAR) that mediates postsynaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal excitability [51]. 14-3-3 binding slows desensitization kinetics of GluK2a-containing KARs. In 14-3-3 FKO mice, expression of the 14-3-3 inhibitor in CA3 neurons leads to a faster decay of KAR-EPSCs at hippocampal mossy fiber-CA3 synapses [52]. This study provides another potential mechanism by which 14-3-3 proteins regulate synaptic functions at the postsynaptic site.

In addition to modulating the level and biophysical properties of postsynaptic glutamate receptors, 14-3-3 functions by regulating synaptogenesis. In the 14-3-3 FKO mice, there is a reduction of both dendritic complexity and spine density in the cortical and hippocampal neurons where the 14-3-3 inhibitor is extensively expressed [53]. A similar reduction in dendritic spine density was observed in 14-3-3ζ-deficient mice in BALB/c background [54, 55]. On the contrary, overexpressing 14-3-3ζ in rat hippocampal neurons significantly increases spine density [56]. Collectively, studies on these animal models provide in vivo evidence for a significant role of 14-3-3 proteins in promoting the formation and maturation of dendritic spines.

While the molecular mechanism for 14-3-3 dependent regulation of synaptogenesis remains elusive, several in vitro studies have proposed 14-3-3 proteins as important regulators of cytoskeleton and actin dynamics, which are critical for controlling the shape, organization, and maintenance of dendritic spines in postsynaptic neurons [57, 58]. Earlier studies showed that 14-3-3ζ regulates actin dynamics through its direct interaction with phosphorylated cofilin (p-cofilin) [57]. Cofilin is a major actin depolymerizing factor. Reduction of p-cofilin enhances the activity of cofilin, promotes the turnover of actin filaments, and consequently destabilizes dendritic spines [55, 56]. Moreover, a different group identified cofilin and its regulatory kinase LIM-kinase 1 (LIMK1) as binding partners of 14-3-3ζ and suggested that interactions with the C-terminal region of 14-3-3ζ inhibit the binding of cofilin to F-actin [59]. However, a direct interaction between 14-3-3 and cofilin/p-cofilin was challenged by a later study, in which Sudnitsyna et al. demonstrated that 14-3-3 only weakly interacts with cofilin, and they suggested that 14-3-3 proteins most likely regulate actin dynamics through other regulatory kinases such as LIMK1 or slingshot 1 L phosphatase (SSH) [60]. In fact, 14-3-3ζ has been shown to directly bind with phosphorylated SSH and lower its ability to bind F-actin [58].

More recently, Toyo-oka et al. showed that 14-3-3ε and 14-3-3ζ bind to δ-catenin and potentially regulate actin dynamics through δ-catenin [11, 61]. Catenin activates the Rho family of GTPase that results in the phosphorylation and activation of LIMK1. Loss of 14-3-3 proteins results in stabilization of δ-catenin through the ubiquitin-proteasome system, thereby decreasing LIMK1 activity and reducing p-cofilin level. Therefore, it is possible that 14-3-3 proteins may promote F-actin formation and spinogenesis by interacting with multiple elements in the regulatory pathways of the actin polymerization/depolymerization cycles (Figure 2).

4. Conclusion

The glutamatergic synapses mediate the majority of excitatory neurotransmission in the mammalian brain. Regulation of the property and connectivity of glutamatergic synapses represents a major mechanism for activity-dependent modification of synaptic strength and is critical for higher brain functions. 14-3-3 proteins have emerged as one of the important modulators at these synapses. It is particularly interesting that 14-3-3 binding and function are generally regulated by phosphorylation, which is a well-established molecular process underlying synaptic plasticity. Thus, 14-3-3 can potentially integrate multiple signaling pathways and plays a significant role in dynamic modification of glutamatergic synapses. As demonstrated by recent animal models, 14-3-3 deficiencies in rodent brain often result in the onset of abnormal behaviors, which might correspond to symptoms of neurological disorders.

Abbreviations

- NMJ:

Neuromuscular junction

- EJCs:

Excitatory junctional currents

- EPSCs:

Excitatory postsynaptic currents

- PTP:

Posttetanic potentiation

- LTP:

Long-term potentiation

- difopein:

Dimeric fourteen-three-three peptide inhibitor

- FKO:

Functional knockout

- PSD:

Postsynaptic density

- LIMK:

LIM kinases

- SSH:

Slingshot.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Moore B. W., Carlson E. C. F. D. Physiological and Biochemical Aspects of Nervous Integration. New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1967. Specific acidic proteins of the nervous system; pp. 343–359. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao B., Smerdon S. J., Jones D. H., et al. Structure of a 14-3-3 protein and implications for coordination of multiple signalling pathways. Nature. 1995;376(6536):188–191. doi: 10.1038/376188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rittinger K., Budman J., Xu J., et al. Structural analysis of 14-3-3 phosphopeptide complexes identifies a dual role for the nuclear export signal of 14-3-3 in ligand binding. Molecular Cell. 1999;4(2):153–166. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muslin A. J., Tanner J. W., Allen P. M., Shaw A. S. Interaction of 14-3-3 with signaling proteins is mediated by the recognition of phosphoserine. Cell. 1996;84(6):889–897. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mhawech P. 14-3-3 proteins - an update. Cell Research. 2005;15(4):228–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenreichova A., Klima M., Boura E. Crystal structures of a yeast 14-3-3 protein from Lachancea thermotolerans in the unliganded form and bound to a human lipid kinase PI4KB-derived peptide reveal high evolutionary conservation. Acta Crystallographica Section F Structural Biology Communications. 2016;72(11):799–803. doi: 10.1107/S2053230X16015053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu D., Bienkowska J., Petosa C., Collier R. J., Fu H., Liddington R. Crystal structure of the zeta isoform of the 14-3-3 protein. Nature. 1995;376(6536):191–194. doi: 10.1038/376191a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aitken A. 14-3-3 proteins on the MAP. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 1995;20(3):95–97. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)88971-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu H., Subramanian R. R., Masters S. C. 14-3-3 proteins: structure, function, and regulation. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2000;40(1):617–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marzinke M. A., Mavencamp T., Duratinsky J., Clagett-Dame M. 14-3-3ε and NAV2 interact to regulate neurite outgrowth and axon elongation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2013;540(1-2):94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyo-oka K., Wachi T., Hunt R. F., et al. 14-3-3ε and ζ regulate neurogenesis and differentiation of neuronal progenitor cells in the developing brain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(36):12168–12181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2513-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg D., Holzmann C., Riess O. 14-3-3 proteins in the nervous system. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003;4(9):752–762. doi: 10.1038/nrn1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slone S. R., Lavalley N., McFerrin M., Wang B., Yacoubian T. A. Increased 14-3-3 phosphorylation observed in Parkinson’s disease reduces neuroprotective potential of 14-3-3 proteins. Neurobiology of Disease. 2015;79:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmitz M., Ebert E., Stoeck K., et al. Validation of 14-3-3 protein as a marker in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease diagnostic. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53(4):2189–2199. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foote M., Zhou Y. 14-3-3 proteins in neurological disorders. International Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2012;3(2):152–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao J., Meyerkord C. L., Du Y., Khuri F. R., Fu H. 14-3-3 proteins as potential therapeutic targets. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2011;22(7):705–712. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan A., Ottmann C., Fournier A. E. 14-3-3 adaptor protein-protein interactions as therapeutic targets for CNS diseases. Pharmacological Research. 2017;125(Part B):114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottmann C. Small-molecule modulators of 14-3-3 protein-protein interactions. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. 2013;21(14):4058–4062. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevers L. M., de Vries R. M. J. M., Doveston R. G., Milroy L. G., Brunsveld L., Ottmann C. Structural interface between LRRK2 and 14-3-3 protein. Biochemical Journal. 2017;474(7):1273–1287. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20161078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin H., Rostas J., Patel Y., Aitken A. Subcellular localisation of 14-3-3 isoforms in rat brain using specific antibodies. Journal of Neurochemistry. 1994;63(6):2259–2265. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63062259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baxter H. C., Liu W. G., Forster J. L., Aitken A., Fraser J. R. Immunolocalisation of 14-3-3 isoforms in normal and scrapie-infected murine brain. Neuroscience. 2002;109(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00492-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoulakis E. M. C., Davis R. L. Olfactory learning deficits in mutants for leonardo, a Drosophila gene encoding a 14-3-3 protein. Neuron. 1996;17(5):931–944. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80224-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broadie K., Rushton E., Skoulakis E. M. C., Davis R. L. Leonardo, a Drosophila 14-3-3 protein involved in learning, regulates presynaptic function. Neuron. 1997;19(2):391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Südhof T. C. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27(1):509–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittelstaedt T., Alvarez-Baron E., Schoch S. RIM proteins and their role in synapse function. Biological Chemistry. 2010;391(6):599–606. doi: 10.1515/BC.2010.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun L., Bittner M. A., Holz R. W. Rim, a component of the presynaptic active zone and modulator of exocytosis, binds 14-3-3 through its N terminus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(40):38301–38309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212801200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simsek-Duran F., Linden D. J., Lonart G. Adapter protein 14-3-3 is required for a presynaptic form of LTP in the cerebellum. Nature Neuroscience. 2004;7(12):1296–1298. doi: 10.1038/nn1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden D. J., Ahn S. Activation of presynaptic cAMP-dependent protein kinase is required for induction of cerebellar long-term potentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1999;19(23):10221–10227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-23-10221.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lonart G., Schoch S., Kaeser P. S., Larkin C. J., Südhof T. C., Linden D. J. Phosphorylation of RIM1α by PKA triggers presynaptic long-term potentiation at cerebellar parallel fiber synapses. Cell. 2003;115(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00727-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaeser P. S., Kwon H.-B., Blundell J., et al. RIM1α phosphorylation at serine-413 by protein kinase A is not required for presynaptic long-term plasticity or learning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(38):14680–14685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806679105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Calakos N. Acute in vivo genetic rescue demonstrates that phosphorylation of RIM1α serine 413 is not required for mossy fiber long-term potentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(7):2542–2546. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4285-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou Y., Schopperle W. M., Murrey H., et al. A dynamically regulated 14-3-3, slob, and slowpoke potassium channel complex in Drosophila presynaptic nerve terminals. Neuron. 1999;22(4):809–818. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80739-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Kelly I., Butler M. H., Zilberberg N., Goldstein S. A. N. Forward transport. 14-3-3 binding overcomes retention in endoplasmic reticulum by dibasic signals. Cell. 2002;111(4):577–588. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)01040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Béguin P., Mahalakshmi R. N., Nagashima K., et al. Nuclear sequestration of beta-subunits by rad and rem is controlled by 14-3-3 and calmodulin and reveals a novel mechanism for Ca2+ channel regulation. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;355(1):34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patil P. G., Brody D. L., Yue D. T. Preferential closed-state inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Neuron. 1998;20(5):1027–1038. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forsythe I. D., Tsujimoto T., Barnes-Davies M., Cuttle M. F., Takahashi T. Inactivation of presynaptic calcium current contributes to synaptic depression at a fast central synapse. Neuron. 1998;20(4):797–807. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Y., Wu Y., Zhou Y. Modulation of inactivation properties of CaV2.2 channels by 14-3-3 proteins. Neuron. 2006;51(6):755–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang B., Yang H., Liu Y. C., et al. Isolation of high-affinity peptide antagonists of 14-3-3 proteins by phage display. Biochemistry. 1999;38(38):12499–12504. doi: 10.1021/bi991353h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masters S. C., Fu H. 14-3-3 proteins mediate an essential anti-apoptotic signal. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(48):45193–45200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cao W., Yang X., Zhou J., et al. Targeting 14-3-3 protein, difopein induces apoptosis of human glioma cells and suppresses tumor growth in mice. Apoptosis. 2010;15(2):230–241. doi: 10.1007/s10495-009-0437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qiao H., Foote M., Graham K., Wu Y., Zhou Y. 14-3-3 proteins are required for hippocampal long-term potentiation and associative learning and memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(14):4801–4808. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4393-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asrican B., Augustine G. J., Berglund K., et al. Next-generation transgenic mice for optogenetic analysis of neural circuits. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feng G., Mellor R. H., Bernstein M., et al. Imaging neuronal subsets in transgenic mice expressing multiple spectral variants of GFP. Neuron. 2000;28(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsien J. Z., Huerta P. T., Tonegawa S. The essential role of hippocampal CA1 NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic plasticity in spatial memory. Cell. 1996;87(7):1327–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81827-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lau C. G., Zukin R. S. NMDA receptor trafficking in synaptic plasticity and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2007;8(6):413–426. doi: 10.1038/nrn2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Q., Sheng M. NMDA receptors in nervous system diseases. Neuropharmacology. 2013;74:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen B.-S., Roche K. W. Growth factor-dependent trafficking of cerebellar NMDA receptors via protein kinase B/Akt phosphorylation of NR2C. Neuron. 2009;62(4):471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chung C., Wu W.-H., Chen B.-S. Identification of novel 14-3-3 residues that are critical for isoform-specific interaction with GluN2C to regulate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor trafficking. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2015;290(38):23188–23200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.648436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groc L., Choquet D. AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptor trafficking: multiple roads for reaching and leaving the synapse. Cell and Tissue Research. 2006;326(2):423–438. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0254-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ramsey A. J., Milenkovic M., Oliveira A. F., et al. Impaired NMDA receptor transmission alters striatal synapses and DISC1 protein in an age-dependent manner. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(14):5795–5800. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012621108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Contractor A., Swanson G., Heinemann S. F. Kainate receptors are involved in short- and long-term plasticity at mossy fiber synapses in the hippocampus. Neuron. 2001;29(1):209–216. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00191-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun C., Qiao H., Zhou Q., et al. Modulation of GluK2a subunit-containing kainate receptors by 14-3-3 proteins. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(34):24676–24690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.462069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foote M., Qiao H., Graham K., Wu Y., Zhou Y. Inhibition of 14-3-3 proteins leads to schizophrenia-related behavioral phenotypes and synaptic defects in mice. Biological Psychiatry. 2015;78(6):386–395. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu X., Jaehne E. J., Greenberg Z., et al. 14-3-3ζ deficient mice in the BALB/c background display behavioural and anatomical defects associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Scientific Reports. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1038/srep12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jaehne E. J., Ramshaw H., Xu X., et al. In-vivo administration of clozapine affects behaviour but does not reverse dendritic spine deficits in the 14-3-3ζ KO mouse model of schizophrenia-like disorders. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2015;138:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Angrand P.-O., Segura I., Völkel P., et al. Transgenic mouse proteomics identifies new 14-3-3-associated proteins involved in cytoskeletal rearrangements and cell signaling. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 2006;5(12):2211–2227. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600147-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gohla A., Bokoch G. M. 14-3-3 regulates actin dynamics by stabilizing phosphorylated cofilin. Current Biology. 2002;12(19):1704–1710. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01184-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soosairajah J., Maiti S., Wiggan O.'. N., et al. Interplay between components of a novel LIM kinase-slingshot phosphatase complex regulates cofilin. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(3):473–486. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birkenfeld J., Betz H., Roth D. Identification of cofilin and LIM-domain-containing protein kinase 1 as novel interaction partners of 14-3-3 zeta. The Biochemical Journal. 2003;369(1):45–54. doi: 10.1042/bj20021152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sudnitsyna M. V., Seit-Nebi A. S., Gusev N. B. Cofilin weakly interacts with 14-3-3 and therefore can only indirectly participate in regulation of cell motility by small heat shock protein HspB6 (Hsp20) Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2012;521(1-2):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cornell B., Toyo-Oka K. 14-3-3 proteins in brain development: neurogenesis, neuronal migration and neuromorphogenesis. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 2017;10:p. 318. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]