Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies show that maternal diabetes predisposes offspring to cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. However, the precise mechanisms for the underlying penetrance and disease predisposition remain poorly understood. We examined whether hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha, in combination with exposure to a diabetic intrauterine environment, influences the function and molecular structure of the adult offspring heart.

Methods and results

In a mouse model, we demonstrated that haploinsufficient (Hif1a+/−) offspring from a diabetic pregnancy developed left ventricle dysfunction at 12 weeks of age, as manifested by decreased fractional shortening and structural remodeling of the myocardium. Transcriptional profiling by RNA-seq revealed significant transcriptome changes in the left ventricle of diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− offspring associated with development, metabolism, apoptosis, and blood vessel physiology. In contrast, both wild type and Hif1a+/− offspring from diabetic pregnancies showed changes in immune system processes and inflammatory responses. Immunohistochemical analyses demonstrated that the combination of haploinsufficiency of Hif1a and exposure to maternal diabetes resulted in impaired macrophage infiltration, increased levels of advanced glycation end products, and changes in vascular homeostasis in the adult offspring heart.

Conclusions

Together our findings provide evidence that a global reduction in Hif1a gene dosage increases predisposition of the offspring exposed to maternal diabetes to cardiac dysfunction, and also underscore Hif1a as a critical factor in the fetal programming of adult cardiovascular disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12933-018-0713-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fetal programming, Maternal diabetes, Hif1a haploinsufficiency, Echocardiography, Heart remodelling

Background

Parallel to the increasing global incidence of diabetes, the prevalence of diabetes in women of childbearing age is steadily rising. Diabetic pregnancy has been associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes for the mother as well as the offspring compared to non-diabetic pregnancy [1–4]. Congenital heart defects are the most common malformations observed in offspring of diabetic pregnancies, with an eightfold increase compared to non-diabetic pregnancies [5]. Similar risks for cardiac malformation have been reported for pre-gestational type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus [5]. Since type 1 and type 2 diabetes have different etiologies, these results indicate that the adverse effects on heart development are induced by pathological processes shared by both types of diabetes, such as hyperglycemia, hypoxia, oxidative stress, and abnormal maternal/fetal fuel metabolism.

In addition to the direct teratogenicity of maternal diabetes, the intrauterine and early postnatal environment can influence the cardiovascular and metabolic health of offspring later in life. This phenomenon is termed fetal or developmental programming [6]. The offspring of a diabetic pregnancy show differences in metabolic, cardiovascular and inflammatory variables compared to the offspring of non-diabetic mothers [7–9]. However, the precise mechanisms for the underlying penetrance and disease predisposition remain poorly understood.

Hypoxia plays an important role in all diabetic complications [10–12], including the complications associated with diabetic pregnancy [2, 13–15]. The main regulator of responses to a hypoxic environment is hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 consists of two subunits, HIF-1α, which is an O2-labile subunit, and HIF-1β, which is constitutively expressed [16]. HIF-1α is also important for normal embryonic development since mice with a homozygous deletion of the Hif1a gene die due to cardiac malformations and vascular defects [17]. Hif1a heterozygous mutants (Hif1a+/−) normally survive past embryonic development; however, Hif1a+/− mice demonstrate impaired responses when challenged with hypoxic conditions after birth [18–20]. Cardiac myocyte-specific Hif1a deletion causes reductions in contractility, vascularization, and also alters the expression of multiple genes in the heart during normoxia [21]. HIF-1α is destabilized by hyperglycemia leading to the loss of cellular adaptation to low oxygen in diabetes [10, 22]. Previously, we showed that decreased levels of Hif1a in combination with a diabetic environment were associated with increased susceptibility to diabetic embryopathy [23]. We found a decreased number of embryos per litter and increased incidence of heart malformations, particularly atrioventricular septal defects and reduced myocardial mass in diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− mice compared to wild type (Wt) littermates. To extend our previous study on the effects of global heterozygous deletion of Hif1a and maternal diabetes exposure on heart development in embryos [23], we analysed the heart of the adult offspring in the same experimental paradigm. We examined the relationship between a partial deficiency of HIF-1α and an intrauterine exposure to maternal diabetes in the fetal programming of the heart.

Research design and methods

Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Molecular Genetics and performed in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health publication, 8th edition, updated 2011). Diabetes was induced in female inbred FVB mouse strain (Wt, strain code 207, Charles River), aged 7–9 weeks, by 2 intraperitoneal injections of 100 mg/kg body weight of streptozotocin (STZ; Sigma) within a 1-week interval, as described [23]. Blood glucose levels were measured in animals by glucometer (COUNTOUR TS, Bayer); blood glucose levels maintained above 13.9 mmol/L are classified as diabetic. The dams were set up for mating no earlier than 7 days after the last injection. Average blood glucose level of STZ-induced female Wt before mating was 18.54 ± 1.08 mmol/L. This experimental design ensured that the development of the embryos proceeded in the intrauterine environment of maternal diabetes. Only diabetic Wt females were mated to Hif1a+/− males with the Hif1atm1jhu null allele [17] on an FVB background to generate Hif1a+/− and Wt (Hif1a+/+) offspring (n = 11 litters of non-diabetic pregnancy, n = 10 litters of diabetic pregnancy). Hif1a+/− mice show a partial loss of HIF-1α protein expression levels [18, 20]. Mice were kept under standard experimental conditions with constant temperature (23–24 °C) and fed on soy-free feed (LASvendi, Germany). The females were housed individually during the gestation period and the litter size was recorded. All dams were pregnant for the first time. Offspring of Wt female× Hif1a+/– male mating were genotyped by PCR [23].

Echocardiography

The echocardiographic evaluation of the geometrical and functional parameters of the left ventricle (LV) was performed using the GE Vivid 7 Dimension (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Horten, Norway) with a 12 MHz linear matrix probe M12L. The 12-week-old animals were anesthetized by the inhalation of 2% isoflurane (Aerrane, Baxter) and their rectal temperature was maintained between 36.5 and 37.5 °C by a heated table throughout the measurements. The 1-week old offspring were measured without anesthesia. The following diastolic and systolic dimensions of the LV were measured: the posterior and anterior wall thickness, and cavity diameter (LVDD and LVDS). From these dimensions, the functional parameter, fractional shortening (FS) was derived by the following formula:

RNA-sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the LV of the hearts of 12-week-old mice. The quality of the isolated RNA was analyzed using Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent) and a functional test was performed by reverse transcription (RT) and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) using oligodT primers for RT and PCR amplification of a 996-bp product of the Hprt1 gene. 3′-seq libraries from 3 LVs per group (n = 3 samples from mice from multiple litters/group) were prepared and next-generation sequencing was performed on an Illumina NextSeq sequencer (NextSeq500) using a mode enabling the determination of uni-directional 75 bases and indices, following manufacturer’s instructions at the Genomics Core Facility (EMBL Heidelberg, Germany). The number of reads (minimum, 32 million; maximum, 73 million) was filtered out by TrimmomaticPE version 0.36 [24]. Ribosomal RNA and mitochondrial reads were filtered out by Sortmerna (version 2.1b [25]) using default parameters. RNAseq reads were mapped to the mouse genome using STAR (version 2.5.2b [26]) version GRCm38 primary assembly and annotation version M8. Count table was generated by python script htseq-count (version 0.6.1p1, [27]) with parameter “–m union”. The raw RNAseq data were deposited at GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) #GSE109633. DESeq2 (v. 1.15.51, [28]) default parameters were used to normalize data and compare the different groups. We selected differentially expressed genes based on an adjusted P value < 0.1. Functional classification was done using DAVID Functional Annotation tool (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/). For the Venn diagram, a 30% change threshold was applied in each group compared to unexposed Wt. Mammalian phenotype ontology enrichment analysis of MGI (http://www.informatics.jax.org) was used. Enrichment analysis was performed using g:GOST Gene Group Functional Profiling; g:Profiler (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/). Manual literature search and Harmonizome database [29] were used to identify direct HIF-1 targets and predicted HIF-1 target genes, respectively.

Reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was isolated from the LV of the hearts of offspring at 12 weeks of age (n = 8 samples/group). Following reverse transcription (RT), quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with the initial AmpliTaq activation at 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 30 s, as described [19]. The Hprt1 gene was selected as the best reference gene for our analyses from a panel of 12 control genes (TATAA Biocenter AB, Sweden). The relative expression of a target gene was calculated, based on qPCR efficiencies and the quantification cycle (Cq) difference (Δ) of an experimental sample versus control. Primers were designed using Primer Blast tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). Primers were selected according to the following parameters: length between 18 and 24 bases, melting temperature (Tm) between 58° and 60 °C, G+C content between 40 and 60% (optimal 50%) and efficiency above 80%. Primer sequences are presented in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Western blot assays

The LV from the diabetic and non-diabetic hearts were lysed with protease and phosphatase inhibitors to prevent protein degradation and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. 50 µg of total protein lysates per lane were resolved using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% dry milk and incubated overnight with anti-CX43 antibody at 1:6000 (C6219, Sigma), anti-pCX43 at 1:1000 (3511, Cell Signaling), and anti-TNFR2 at 1:1000 (sc-7862, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After incubation with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary IgG (Sigma), the blots were developed using the SuperSignal™ West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (#34095; Thermo Scientific, MI, USA). Chemiluminescent signals were captured using an Biorad Chemidoc MP Imager and analyzed by ImageJ software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html). Ponceau S staining was used as the loading control.

Morphological and immunohistochemical analyses

The scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of 12-week-old mouse hearts were produced as described [30]. Paraffin Sections (8 μm) were stained with Periodic acid–Schiff [PAS; staining of advanced glycation end products (AGEs); 395B, Sigma], Picrosirius Red (collagen staining, 24901-250, Polysciences), TUNEL (#1684795, Roche), anti-PECAM-1 1:50 (Ab28364, Abcam), and anti-VEGFA 1:50 (sc-7269, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Vibratome Sections (100 μm) were stained with anti-F4/80 1:500 (MCA497R, Biorad). The nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342. The sections were assessed under a Nikon Eclipse 50i and Nikon Eclipse E400 microscopes, Leica MZFLIII stereomicroscope, and Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope, with NIS-elements or ZEN lite programs. The number of F4/80+ cells were specifically counted in the LV area in the field of view (2–5 Z-stacks/5 areas of the LV/1 vibratome section/4 individuals/group). TUNEL+ cells were counted in three consecutive transversal paraffin sections of the heart/4 individuals/group, as described [23]. Picrosirius Red+, PAS+ and PECAM-1+ areas were quantified as a percentage of the LV area in the field of view using Image J software. VEGFA expression was determined specifically in the wall of blood vessels of the LV as a percentage of vessel area using Image J software (three consecutive transversal sections of the heart/4 individuals/group).

Statistics

We used two-way ANOVA to compare differences among experimental groups with genotype and experimental condition (diabetes or no diabetes exposure) as the two categories. When a significant interaction was detected, the differences between subgroups were further analysed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison and t tests; significance assigned at the P < 0.05 level (GraphPad Prism 7).

Results

Exposure to maternal diabetes and Hif1a deficiency alter heart function in offspring

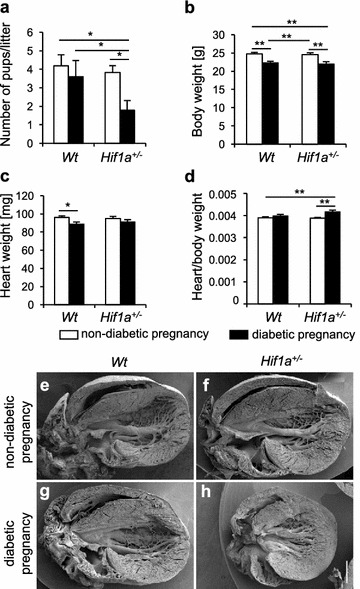

In our previous study, deletion of Hif1a+/− in combination with maternal diabetes was shown to lead to an increased incidence of congenital cardiac defects [23]. Consistent with the previous study, we found the number of liveborn Hif1a+/− offspring from a diabetic pregnancy (n = 10 litters) significantly decreased compared to the number of Wt littermates from a diabetic pregnancy or the number of offspring from a non-diabetic pregnancy (n = 11 litters; Fig. 1a). To minimize the potential influence of maternal genotype, Hif1a+/− offspring were generated by mating Wt females with Hif1a+/− males. Body weight was decreased in both Wt and Hif1a+/− offspring exposed to maternal diabetes, whereas the heart weight was lower in Wt mice at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 1b, c). The heart to body weight ratio, an index of cardiac enlargement, was significantly increased as a result of the combined effect of Hif1a mutation and fetal exposure to maternal diabetes (Fig. 1d). The gross morphology of the hearts revealed no differences in the structure of chambers or valves (Fig. 1e–h). Interestingly, the heart of diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− offspring had a globular shape with less elongated and more globular ventricles compared to the hearts in others groups of adult offspring. The globular shape of the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− heart was indicated by the ratio of the left–right axis (width) and the apical-basal axis (length) of the heart (mean ratio = 1.03) compared to the normal shaped hearts of unexposed Wt and Hif1a+/−, and diabetes-exposed Wt (mean ratio = 1.38, 1.39, and 1.38, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Adverse effects of maternal diabetes exposure and Hif1a mutation on the survival, and heart weight of the offspring. Average number of surviving Hif1a+/− pups per litter from diabetic pregnancy at P7 compared to non-diabetic pregnancy (a). The body weight (b), heart weight (c), and heart/body ratio (d) in all groups of 12-week-old Wt and Hif1a+/− mice from non-diabetic and diabetic pregnancies. The values are mean ± SEM (a n = 11 litters of non-diabetic pregnancy, n = 10 litters of diabetic pregnancy; b–d n = 20 Wt from non-diabetic pregnancy, n = 15 Wt from diabetic pregnancy, n = 15 for Hif1a+/− from non-diabetic pregnancy, n = 10 Hif1a+/− from diabetic pregnancy). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: diabetes effect (number of pups/litter, P = 0.0391; body weight, P < 0.0001; heart weight, P = 0.0124; heart/body weight, P = 0.0003); and interaction between genotype and diabetes (heart/body weight, P = 0.0362). *Significant differences by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. e–h Representative scanning electron micrographs (SEM) of the posterior half of the 12-week-old mouse heart

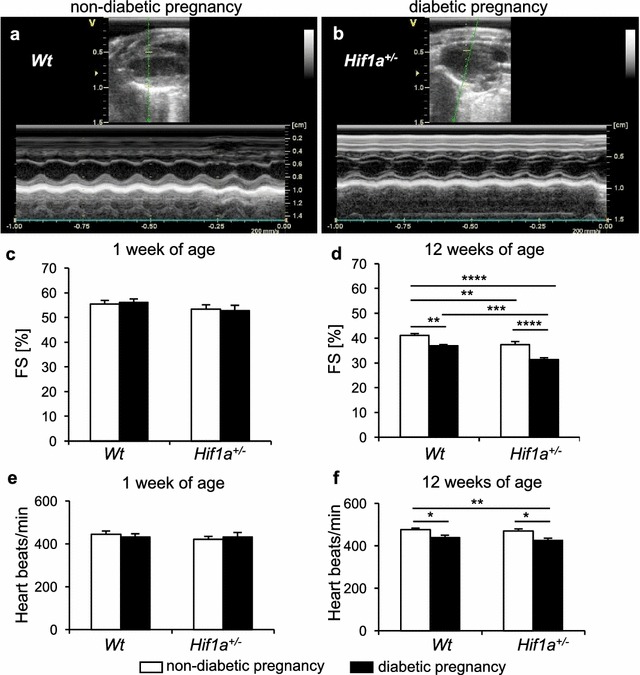

Echocardiographic analyses of the LV function in 1- and 12-week-old offspring disclosed a significant decrease in fractional shortening (FS) in diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− compared to diabetes-exposed Wt (P < 0.001), and unexposed Wt or Hif1a+/− controls (P < 0.0001) at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 2a–d, Additional file 2: Table S2). These changes were associated with Hif1a+/− genotype and with diabetes exposure, predominantly as a result of a larger systolic diameter of the LV of diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− mice (Additional file 2: Table S2). Both males and females were similarly affected in LV echocardiographic parameters (Additional file 2: Table S2), therefore, we used only males for our subsequent analyses. Both diabetes-exposed Wt and Hif1a+/− males had a lower heart rate at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 2e, f), which may indicate changes in cardiovascular autonomic regulation [31].

Fig. 2.

The combination of Hif1a haploinsufficiency and maternal diabetes exposure alters echocardiographic parameters of the offspring. Representative M-mode recordings of LV structures in long axes view in a Wt males from non-diabetic pregnancy and b Hif1a+/− males from diabetic pregnancy. c, d The echocardiographic evaluation of LV systolic function, fractional shortening (FS), in the 1- and 12-week-old male offspring. e, f The heart rate in Wt and Hif1a+/− males from both diabetic and non-diabetic pregnancies at 1 and 12 weeks of age. The values are mean ± SEM (1-week-old: n = 20 Wt from non-diabetic pregnancy; n = 14 Wt from diabetic pregnancy; n = 17 Hif1a+/− from non-diabetic pregnancy; n = 9 Hif1a+/− from diabetic pregnancy; 12-week-old: n = 20 Wt from non-diabetic pregnancy; n = 15 Wt from diabetic pregnancy and Hif1a+/− from non-diabetic pregnancy; n = 10 Hif1a+/− from diabetic pregnancy). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: genotype effect (FS% P < 0.001); and diabetes effect (FS% P < 0.0001; heart rate, P < 0.0001). *Significant differences by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001

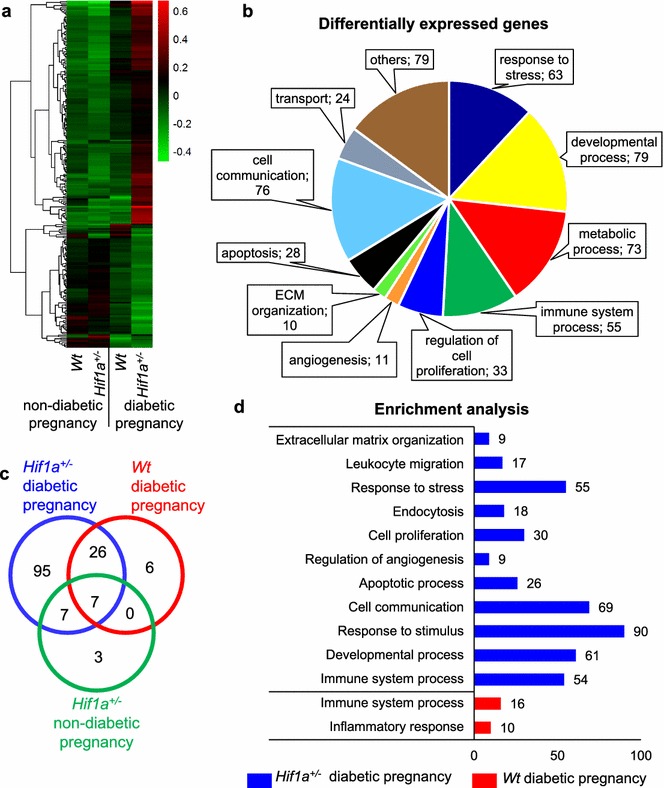

Differential global expression profiles in the LV of the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− and Wt offspring

To map out the mechanisms underlying impaired cardiac function mediated by the exposure to maternal diabetes, we analyzed the expression profiles of the LV from the hearts of offspring using RNA deep sequencing (RNAseq). The expression profiles visualized in a heat map indicate major changes in the Hif1a+/− offspring from diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 3a) with categories of genes relevant to metabolic processes, cell communication, apoptosis, immune system, and developmental processes (Fig. 3b, Additional file 3: Table S3). We focused on differentially expressed genes showing ≥ 30% change in any of the groups compared to Wt from non-diabetic pregnancy, representing 144 differentially expressed genes; the majority of changes (95 genes) were identified only in the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− hearts (Fig. 3c, Additional file 4: Table S4, Additional file 5: Table S5). Of 135 differentially expressed genes in diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− hearts, 53% of these genes were direct or predicted HIF-1 target genes (Additional file 6: Table S6, Additional file 7: Table S7). Enrichment analysis revealed changes in immune system processes and inflammatory response in both Wt and Hif1a+/− offspring from diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 3d, Additional file 8: Table S8). However, the Hif1a+/− offspring from a diabetic pregnancy showed additional changes in multiple categories of biological processes associated with development, response to stress, apoptosis, cell proliferation and communication, and angiogenesis. Mammalian phenotype ontology enrichment analysis revealed significant changes in genes predominantly associated with homeostasis and metabolism phenotype (63 genes, P = 6.93 × 10−4), immune system phenotype (60 genes, P = 2.74 × 10−7), and abnormal innate immunity (25 genes, P = 3.93 × 10−10, Additional file 9: Table S9). Additionally, 17 genes were associated with abnormal blood vessel physiology (P = 5.85 × 10−6) and vascular smooth muscle physiology (9 genes, P = 2.573 × 10−3). We validated RNAseq data by RT-qPCR for a selected set of genes (Additional file 10: Figure S1).

Fig. 3.

Maternal diabetes and Hif1a mutation affect the transcriptome of the LV of Hif1a+/− offspring. The global gene expression profile of LVs isolated from the hearts of 12-week-old Wt and Hif1a+/− mice from diabetic or non-diabetic pregnancy (n = 3 LVs from mice of different litters per group) was determined by RNA sequencing. a Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes in all groups are presented as a heat map and dendrogram. b Classification of differentially expressed genes affected by Hif1a+/− mutation and exposure to maternal diabetes by functional annotation tool DAVID. Values represent number of genes per each category. c Venn diagram shows the number and proportion of differentially (up- and down-regulated) expressed genes with ≥ 30% change in Hif1a+/− and Wt from diabetic pregnancy and Hif1a+/− from non-diabetic pregnancy vs. Wt from non-diabetic pregnancy. d Enrichment analysis using g:Profiler; values represent number of genes per each biological process category

Cardiac structural remodelling in the diabetes-exposed offspring

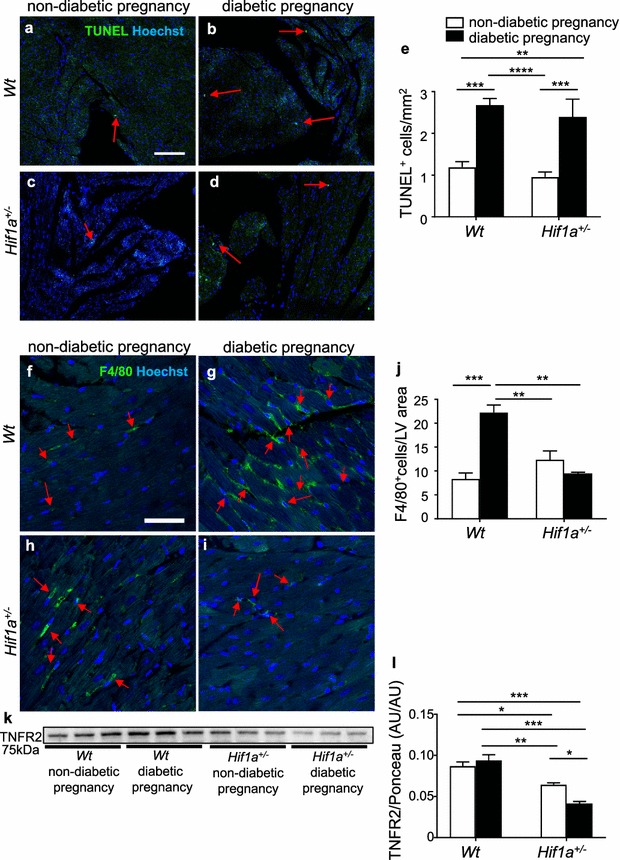

Impaired LV function may be associated with myocardial remodelling, including increased cell death. We assessed the number of apoptotic cells in the LV (Fig. 4a–e), right ventricle (RV), and septum (Additional file 11: Figure S2). We found increased apoptosis in the RV and LV myocardium, and in the septum of both Hif1a+/− and Wt diabetes-exposed offspring.

Fig. 4.

Maternal diabetes exposure increases apoptosis and Hif1a+/− mutation alters macrophage infiltration in the LV myocardium of the 12-week old offspring. a–d Representative images of TUNEL staining (green) with Hoechst stained cell nuclei (blue) in adult myocardium (arrows indicate TUNEL+ cells). Scale bar = 100 µm. e Quantification of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells per mm2 of the LV myocardium. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4 individuals/3 sections/group). f–i Representative confocal images of immunohistochemical staining of macrophage marker F4/80 (green) with Hoechst stained cell nuclei (blue) in adult myocardium (arrows indicate F4/80+ cells). Scale bar = 50 µm. j Quantification of F4/80+ cells per area in the field of view in LV myocardium. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 1 section/2–5 z-stacks/4 individuals/group). k, l Representative Western blot and quantification of TNFR2 expression in the LV myocardium. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA indicating interaction between genotype and diabetes (F4/80, P = 0.0002; TUNEL, P = 0.016; TNFR2, P = 0.0133) genotype effect (F4/80, P = 0.0159); diabetes effect (F4/80, P = 0.0042) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. TNFR2 tumor necrosis factor receptor type II, AU arbitrary units

Since macrophages play a key role in myocardial injury repair and remodelling [32], we analysed the recruitment of macrophages. In contrast to increased apoptosis in both diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− and Wt, the number of F4/80+ infiltrating macrophages was significantly increased only in the LV of the diabetes-exposed Wt heart (Fig. 4f–j). Correspondingly to decreased macrophage infiltration, we found a significantly reduced level of TNFR2 in the LV of diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− mice (Fig. 4k, l). TNFR2 is a cardio-protective mediator of TNFα signalling and its deletion results in reduced macrophage infiltration [33, 34].

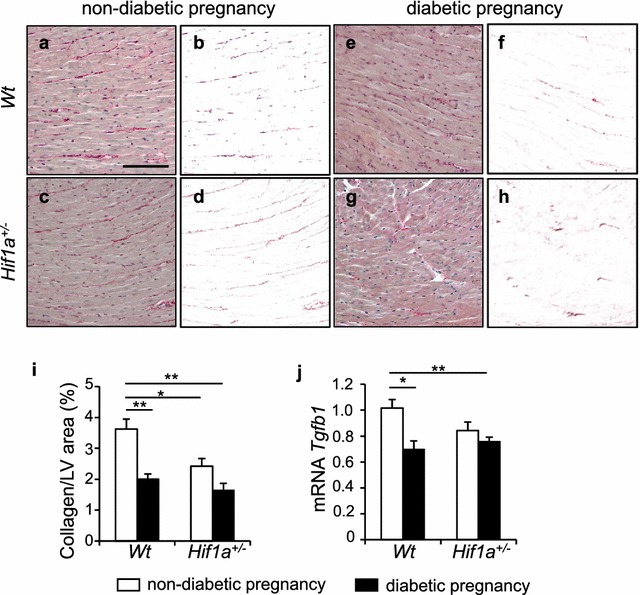

The composition of the myocardial extracellular matrix (ECM) influences cardiac structure and hemodynamic functions. Our RNAseq analysis indicated transcriptional changes in genes encoding ECM structural proteins and ECM regulators. The major component of the ECM is collagen, predominantly collagen type I [35]. Surprisingly, we found decreased collagen deposition in both diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− and Wt and in unexposed Hif1a+/− LVs when compared to Wt (Fig. 5a–i). Increased collagen deposition and pro-fibrogenic processes have been linked to the activation of transforming growth factor ß (TGF-ß) signalling in the heart [36]. The expression pattern of Tgfb1 mRNA, which is the most prevalent isoform of TGF-ß, was similar to the deposition pattern of collagen (Fig. 5j).

Fig. 5.

Remodeling of extracellular matrix in the offspring heart is induced by the exposure to maternal diabetes. Representative images of picrosirius red staining of collagen in the LV myocardium and delineated collagen+ area in the myocardium using Adobe Photoshop (a–h). Scale bar = 100 µm. i Relative quantification of staining determined as a percentage of collagen+ areas per tissue area of the LV myocardium in the field of view by ImageJ. The values are means ± SEM (n = 4). j Relative mRNA expression levels of Tgfb1 in the LV myocardium by RT-qPCR, the values are mean ± SEM (n = 8/group). Data are normalized to Hprt1 mRNA of control gene. Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: genotype effect (tissue collagen, P = 0.0089); diabetes effect (tissue collagen, P = 0.0007; Tgfb1, P = 0.0079) followed by t tests, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Tgfb1 Transforming growth factor beta 1

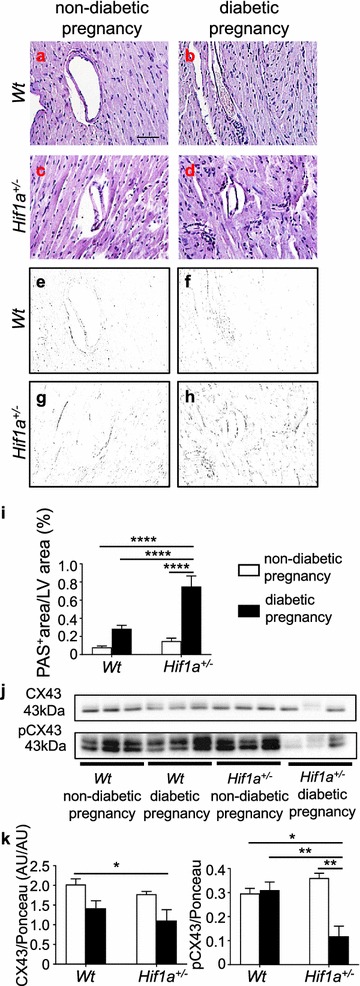

To further assess the effect of tissue-exposure to hyperglycemia, we analyzed the accumulation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) in the heart. The diabetic environment increases the production of AGEs, which comprise adverse non-enzymatic tissue modifications of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [37]. Interestingly, we detected a significant increase of AGEs in the LV of the Hif1a+/− offspring of a diabetic pregnancy (Fig. 6a–i). AGEs have been implicated in the development of cardiac dysfunction by altering properties of the extracellular matrix. Therefore, the increased production of AGEs in the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− heart may represent an increased risk for vascular and myocardial damage in association with impaired contractility, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.

Fig. 6.

The amount of AGEs is increased whereas the activity of gap junction CX43 is reduced in the heart of diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− offspring. Representative images of PAS staining of advanced glycation end products (AGE; a–d). Scale bar = 50 µm. e–h Delineated PAS+ area in the myocardium by Adobe Photoshop. i Quantification of PAS staining determined as a percentage of positive area in the field of view by ImageJ. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). Representative Western blots and quantification of both CX43 and its phosphorylated isoform pCX43 in the LV myocardium of the offspring (j, k). The values are mean ± SEM (n = 3). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: diabetes effect (CX43, P = 0.0088) and interaction between genotype and diabetes (AGEs, P = 0.0013; pCX43, P = 0.0030) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. CX43 connexin 43, PAS periodic acid-shiff, AU arbitrary units

The remodelling of gap junctions and changes in the expression of connexin 43 (CX43) have been associated with a diseased myocardium [38]. CX43 is a key mediator of cardiomyocyte protection during hypoxia [39] and CX43 expression in hypoxia is regulated by HIF-1α [40]. Additionally, the expression and proportion of the phosphorylated and dephosphorylated forms of CX43 are altered in diabetic conditions [41]. In our study, the relative abundance of CX43 protein was reduced in the LV of Hif1a+/− offspring from a diabetic pregnancy compared to the offspring from a non-diabetic pregnancy (Fig. 6j, k). CX43 phosphorylated at serine 368 (pCX43) was significantly reduced in the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− offspring compared to other groups. Phosphorylation of CX43 is important for the functionality of this protein in gap junctions [42] and reduced levels of phosphorylated CX43 have been shown to correlate with worsened heart function in the heart failure model [43].Thus, decreased levels of phosphorylated CX43 in the heart may negatively influence the myocardial function of Hif1a+/− mice from diabetic pregnancies.

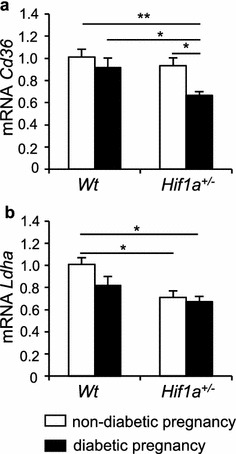

Changes in genes encoding molecules important for cardiac metabolism

Alterations in myocardial substrate selection and utilization in energy metabolism play a role in the development of cardiac pathologies [44]. Our RNAseq analyses showed large changes in the expression of genes associated with metabolic processes. In keeping with this, we investigated two HIF-1 target genes, Cd36 [45] and Ldha, gene encoding lactate dehydrogenase A [46]. CD36 is a multifunctional receptor mediating the uptake of lipoproteins and lipoprotein-derived fatty acid (FA) by cardiomyocytes [47]. LDHA catalyzes the terminal step of anaerobic glycolysis, which is the conversion of pyruvate to lactate. We found decreased Cd36 mRNA in the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− offspring compared to other groups (Fig. 7a). Ldha expression was significantly decreased in both diabetes-exposed and non-exposed Hif1a+/− hearts (Fig. 7b). Altogether, our data suggest metabolic cardiac remodelling associated with Hif1a deficiency and maternal diabetes exposure.

Fig. 7.

Hif1a mutation and maternal diabetes exposure alter the expression of metabolic genes in the LV myocardium. Relative mRNA expression levels of Cd36 (a) and Ldha (b) in the LV myocardium of 12-week-old offspring by RT-qPCR, the values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). Data are normalized to Hprt1 mRNA of control gene. Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: genotype effect (Cd36 mRNA, P = 0.0118; Ldha, P = 0.0034); and diabetes effect (Cd36 mRNA, P = 0.0061) with post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

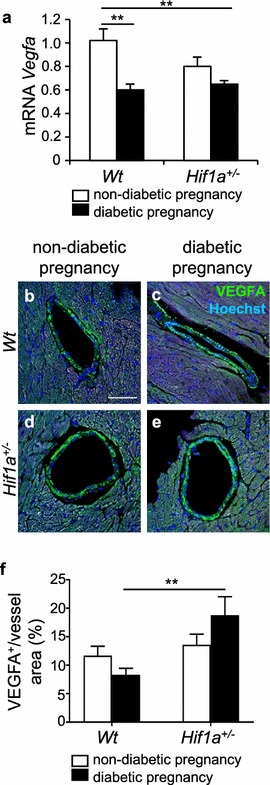

Combination of diabetes pregnancy and Hif1a deficiency alters vascular homeostasis in the myocardium

Because maternal diabetes has been associated with an increased risk for the development of cardiovascular abnormalities in offspring [7], we specifically analyzed the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegfa), a key HIF-1 target gene. The expression of Vegfa mRNA was decreased in the LV of both Hif1a+/− and Wt offspring of diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 8a). Using PECAM-1, an endothelial marker, we did not detect any significant changes, indicating comparable microvasculature in the LV of all offspring groups (Additional file 12: Figure S3). Using immunohistochemistry, we evaluated VEGFA expression in the large blood vessels of the LV myocardium. In contrast to the levels of Vegfa mRNA in the LV, VEGFA expression in the blood vessel wall was significantly higher in diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/− than in Wt hearts (Fig. 8b–f). This surprising finding indicates that Vegfa expression is regulated differently in the myocardium and blood vessel wall. In agreement with our results, a similar expression profile of Vegfa was reported in the myocardium and macrovascular tissues of diabetic patients [48]. Thus, our data provide evidence of differential regulation of Vegfa in cardiac tissue and coronary macrovasculature of the diabetes-exposed Hif1a+/−.

Fig. 8.

Changes in the expression of Vegfa in the heart of the diabetes-exposed offspring. Relative mRNA levels of Vegfa in the LV myocardium of the heart of 12-week-old offspring by RT-qPCR (a), the values are mean ± SEM (n = 8). Data are normalized to Hprt1 mRNA of control gene. b–e Representative confocal images of immunohistochemical staining of VEGFA (green) in the wall of coronary vessels in the LV myocardium of the 12-week-old offspring, Hoechst stained cell nuclei (blue). Scale bar = 50 µm. f A relative quantification of VEGFA in the blood vessels is determined as a percentage of VEGFA+ area per blood vessel area. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: diabetes effect (Vegfa mRNA, P = 0.0003) and interaction between genotype and diabetes (VEGFA in blood vessels, P = 0.0382) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered a molecular mechanism for the underlying penetrance and disease predisposition in the offspring associated with exposure to maternal diabetes. The combination of Hif1a insufficiency and exposure to diabetes in utero leads to the accelerated development of cardiac LV dysfunction. RNAseq analysis showed changes in the global expression profile of the LV of Hif1a+/− heart, indicating transcriptional reprogramming as a consequence of exposure to maternal diabetes. This reprogramming was associated with major changes in HIF-1 regulated pathways, as 53% of identified differentially expressed genes were direct and predicted HIF-1 targets. Thus, the combination of maternal diabetes and Hif1a haploinsufficiency results in significant metabolic, structural, and functional changes in the LV myocardium of the offspring.

Both human and animal studies have shown that exposure to diabetes in utero increases cardiovascular risk factors in the offspring [5, 7, 8, 49]. In agreement with these reports, our study showed that exposure to maternal diabetes during the fetal and perinatal period compromised cardiovascular function of the adult offspring, as indicated by smaller fractional shortening. For the first time to our knowledge, the current study demonstrated that Hif1a haploinsufficiency significantly worsens the cardiac function of the diabetes-exposed offspring. Additionally, we identified an unknown gene-environment interaction between a genetic deficiency in Hif1a and maternal diabetes that affects the size and shape of the heart of the Hif1a+/− offspring. The globular cardiac shape has been observed in children with fetal growth restriction and associated with systolic dysfunction as a result of the intrauterine chronic hypoxia-induced changes in cardiac development [50].

Maternal diabetes negatively affects embryonic development and growth, and compromises placental function [5, 13, 51]. Although here we focused on the heart of the adult offspring, due to the global nature of the Hif1a deletion, we cannot exclude the contribution of placental dysfunction to the programmed outcome phenotype. HIF signalling, in particular, plays an important role in the development and functions of the placenta, and hypoxia-induced placental pathologies have been associated with fetal programming [15, 52–54].

Our genome-scale transcriptome analyses clearly identified a set of pathophysiological processes affected by the maternal diabetes exposure and Hif1a+/− genotype in the LV of offspring. Specifically, we found changes predominantly in metabolic processes, alterations in the innate and adaptive immune responses, apoptosis, and changes in genes associated with developmental processes. In contrast, the Wt offspring from diabetic pregnancies show only significant enrichment of genes involved in immune system processes and inflammatory responses. Clinical studies imply that women with gestational diabetes are at a higher risk of cardiovascular diseases in association with inflammatory dysregulation [3, 4, 55, 56]. Correspondingly, we found an increased number of infiltrating F4/80+ macrophages in the LV of Wt, but not in Hif1a+/− offspring of diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 4). Altered macrophage migration in the Hif1a+/− myocardium is consistent with a recent finding that HIF-1α has an essential role in macrophage inflammatory responses in other physiological settings [32]. The observed increase in TUNEL staining suggests that reduced macrophage recruitment to Hif1a+/− hearts may lead to decreased phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, which may negatively affect the maintenance of tissue integrity and lead to impaired heart function [32].

Beside apoptosis, interstitial fibrosis is another important process of cardiac ventricular remodeling, contributing to both systolic and diastolic contractile dysfunction. Collagen secretion is stimulated by TGF-ß1 within the heart [57]. Although increased cardiac fibrosis is a hallmark of structural remodelling in response to a diabetic environment [58], we paradoxically found decreased collagen deposition along with decreased expression of Tgfb1 in both Hif1a+/− and Wt diabetes-exposed LV at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 5). Diminished collagen deposition was also detected in the hearts of Hif1a+/− offspring from a non-diabetic pregnancy (Fig. 5). HIF-1 regulates multiple steps in collagen biogenesis and HIF-1α knockdown results in reduced collagen deposition [59]. Consistent with this finding, Hif1a haploinsufficiency may affect collagen levels in the heart of Hif1a+/− mice. Similarly, the diabetic environment destabilizes HIF-1α and alters HIF-1 regulation [10, 22] that may affect collagen metabolism in the heart of offspring, resulting in the reduction of collagen fibrils. However, investigating the link between in utero exposure to maternal diabetes and cardiovascular outcomes in offspring is complicated by the multitude of factors that may be present at different time points. Moreover, fibrotic responses are affected by age and duration of disease, when the decreased levels of collagen may represent an intermediate stage of cardiac remodelling associated with degradation of the extracellular collagen matrix [60]. Thus, disturbance in the synthetic and degradative aspects of collagen metabolism results in profound structural and functional abnormalities of the heart. A loss of collagen fibrils is associated with LV remodelling during volume overload and with ECM remodelling in dilated cardiomyopathy [61]. Decreased collagen expression has been reported in children with failing single ventricle congenital heart disease [62]. Although, based on our current data, we cannot determine whether reduced collagen content represents adverse ECM remodelling that predisposes to cardiac dysfunction, our results clearly indicate that the exposure to maternal diabetes and Hif1a haploinsufficiency significantly affect ECM structure and composition compared with a normal myocardium.

Another mechanism implicated in the pathophysiology of the diabetic environment is enhanced production of AGEs. In the heart, protein glycation reactions alter the physiological properties of extracellular matrix proteins and cause intracellular changes in vascular and myocardial tissue [37]. As such, AGEs represent a cardiovascular risk factor in the development of macro- and microvascular complications in diabetic patients [63]. The increased levels of these pro-oxidant diabetogenic products correlate with increased oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in diabetic animals as well as in their progeny [64]. We found a significant accumulation of AGEs in the LV of Hif1a+/− offspring from a diabetic pregnancy (Fig. 6). These results provide new insights into the role of HIF-1α haploinsufficiency in susceptibility to enhanced accumulation of AGEs due to maternal diabetes exposure. Given that (i) HIF-1 regulates glucose metabolism and glycolysis to minimize oxidative stress [16], (ii) diabetic Hif1a+/− mice compared to diabetic Wt have increased serum glucose and AGEs [65], and impaired glucose homeostasis [66], it is tempting to speculate that deficiency in HIF-1 regulation during embryonic development results in increased AGEs in the cardiac tissue of Hif1a+/− offspring due to systemic changes in glucose metabolism and oxidative stress in the maternal diabetes environment. To clarify this question raised by our model, detailed analyses of the levels of tissue AGE modifications during embryonic and early postnatal development are now needed.

Besides structural remodelling, we identified changes in the expression of genes associated with metabolic processes that may contribute to impaired cardiac performance and increase the risk of developing heart disease in the offspring from diabetic pregnancy. Alterations in myocardial energy substrate are predominantly represented by changes in the ratio of fatty acid oxidation and glucose oxidation and have been associated with the development of cardiac pathologies [44]. During perinatal cardiac development, the heart undergoes a switch in energy substrate preference from glucose in the fetal period to FAs. In the diabetic environment, the fetal heart is exposed to abnormal levels of substrates that may remodel cardiac metabolism of the offspring. We found significantly decreased expression of gene encoding the fatty acid translocase, Cd36, in the heart of Hif1a+/− offspring from a diabetic pregnancy compared to other groups (Fig. 7). Decreased myocardial levels of CD36 have been found detrimental, even in the absence of elevated circulating FAs, and to contribute to cardiac dysfunction [67]. The decreased Cd36 expression observed in the hearts of Hif1a+/− offspring of diabetic pregnancies is consistent with a previous report that Cd36 expression is regulated by HIF-1 [45]. Expression of another direct HIF-1 target, the glycolytic gene Ldha [68], was significantly reduced in the LV by Hif1a haploinsufficiency (Fig. 7). Since optimal bioenergetics are an important prerequisite for contractile efficiency, any abnormalities resulting in decreased energy production, energy transfer and energy utilization may compromise cardiac function.

To further investigate changes in angiogenesis, indicated by our RNAseq, we analysed the expression of VEGFA in the heart of the offspring. We detected a decrease in cardiac Vegfa mRNA in the LV of both Hif1a+/− and Wt offspring from diabetic pregnancies (Fig. 8). Indeed, several reports have demonstrated that the expression of Vegfa mRNA and protein are decreased in the myocardium of diabetic, insulin-resistant animals, and in diabetic patients, and have been associated with vascular abnormalities in the diabetic heart and with diabetic cardiomyopathy [69, 70]. Cardiomyocyte-specific Vegfa deletion demonstrates that cardiac myocytes are a major source of VEGFA in the heart and that the development and maintenance of coronary macrovasculature are compensated by non-cardiomyocyte Vegfa expression [71]. This phenotype also implies a different signalling mechanism for vasculogenesis/angiogenesis in the myocardium and in the coronary vasculature. In line with these data, we detected a different Vegfa expression pattern in the cardiac tissue and in the wall of large coronary vessels. VEGFA levels in the coronary vessels were increased by the combination of Hif1a haploinsufficiency and diabetes exposure. A similar expression profile with reduced Vegfa levels in the cardiac tissue and increased Vegfa expression in macrovascular tissues was reported in diabetic patients [48]. Thus, these paradoxical changes in the expression of Vegfa suggest that local regulatory factors differ between the myocardium and blood vessels. It is conceivable that pathophysiological conditions, such as diabetes or hypoxia, alter the regulation of Vegfa expression in the coronary macrovasculature and myocardium.

Conclusions

In a mouse model of maternal diabetes exposure, HIF-1α heterozygous loss-of-function was associated with impaired cardiac function and structural reprogramming of the heart of offspring, including decreased macrophage migration, increased accumulation of AGEs, and altered Vegfa expression. Since the HIF-1 system is compromised in the diabetic environment, a failure to adequately express and activate HIF-1α regulation provide a molecular mechanism that may contribute to the cardiac dysfunction seen in the offspring. Furthermore, the frequencies of single-nucleotide polymorphisms of the human HIF1A gene, which are associated with reduced HIF-1 activity, were significantly increased in patients with ischemic heart disease presentation [72]. Taken together, our results are compelling evidence of the role of HIF-1α-controlled pathways in increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases in the offspring of diabetic mothers.

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Basal left ventricular echocardiographic parameters, heart rate, and body weight of the offspring.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Bioinformatics classification of differentially expressed genes.

Additional file 4: Table S4. List of genes in Venn diagram in Fig. 3.

Additional file 5: Table S5. List of differentially expressed genes with fold change ≥ 30%.

Additional file 6: Table S6. The list of HIF-1 signaling target genes.

Additional file 7: Table S7. The list of the references for genes linked to HIF-1 signalling by manual literature search.

Additional file 8: Table S8. Bioinformatics enrichment analysis using gProfiler: g:GOST Gene Group Functional Profiling tool.

Additional file 9: Table S9. Bioinformatics mammalian phenotype ontology enrichment analysis using MouseMine Analysis Tools.

Additional file 10: Figure S1. RNAseq data validation by RT-qPCR. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 3/group for RNA-Seq, n = 8/group for RT-qPCR).

Additional file 11: Figure S2. Quantification of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells per mm2 of the RV myocardium (a) and septum (b). The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4 individuals/3 sections/group). Two-way ANOVA indicating a significant effect of diabetes (RV: P < 0.0001; septum: P < 0.0001) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

Additional file 12: Figure S3. PECAM-1 expression in the LV. Representative images of staining of PECAM-1 (red) with Hoechst stained cell nuclei (blue) in the LV of 12 week-old offspring (a-d). Scale bar = 50 μm. e-h: Delineated PECAM+ area in the myocardium using Adobe Photoshop. Quantification of PECAM-1 staining determined as a percentage of positive area in the field of view by ImageJ (i). The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: genotype effect P = 0.0302, followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test with no significant result.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to experimental design, have read and approved the manuscript. GP conceptualized the work and wrote the manuscript. FK designed physiological evaluations. RC, RB, FK, FP, and DS designed and carried out the experiments, and analysed the data. VB designed and carried out RNAseq. PA and RC performed bioinformatics analysis of RNAseq data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Gregg L. Semenza, M.D., Ph.D., Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank R. Sindelka, Ph.D., for helpful discussion of RNAseq experiments. We thank A. Pavlinek for editing the manuscript. We thank the Imaging Methods Core Facility at BIOCEV supported by the MEYS CR (LM2015062 Czech-BioImaging) and the Genomics Core Facility EMBL Heidelberg.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and was performed in accordance to the ethics principles in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Sources of funding

This work was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (Grant Agreement No. 16-06825S to GP); by BIOCEV CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0109 from the ERDF; by the institutional support of the Czech Academy of Sciences RVO: 86652036; and by the Charles University in Prague (GA UK No. 228416 to RC).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- AGEs

advanced glycation end products

- CD36

cluster of differentiation 36 (fatty acid translocase)

- COL1

collagen 1

- CX43

connexin 43

- FA

fatty acid

- FS

fractional shortening

- HIF-1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha

- LDHA

lactate dehydrogenase A

- LV

left ventricle

- PAS

periodic acid-shiff

- RNAseq

RNA deep sequencing

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RV

right ventricle

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TGFß1

transforming growth factor, beta 1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor

- TNFR2

tumor necrosis factor receptor type II

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- VEGFA

vascular endothelial growth factor A

- Wt

wild type

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12933-018-0713-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Greene MF. Diabetic embryopathy 2001: moving beyond the “diabetic milieu”. Teratology. 2001;63(3):116–118. doi: 10.1002/tera.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persson M, Norman M, Hanson U. Obstetric and perinatal outcomes in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: a large, population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(11):2005–2009. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goueslard K, Cottenet J, Mariet AS, Giroud M, Cottin Y, Petit JM, Quantin C. Early cardiovascular events in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:15. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0338-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vilmi-Kerala T, Lauhio A, Tervahartiala T, Palomaki O, Uotila J, Sorsa T, Palomaki A. Subclinical inflammation associated with prolonged TIMP-1 upregulation and arterial stiffness after gestational diabetes mellitus: a hospital-based cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12933-017-0530-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oyen N, Diaz LJ, Leirgul E, Boyd HA, Priest J, Mathiesen ER, Quertermous T, Wohlfahrt J, Melbye M. Prepregnancy diabetes and offspring risk of congenital heart disease: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2016;133(23):2243–2253. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barker DJ. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in later life. Br Med Bull. 1997;53(1):96–108. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manderson JG, Mullan B, Patterson CC, Hadden DR, Traub AI, McCance DR. Cardiovascular and metabolic abnormalities in the offspring of diabetic pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2002;45(7):991–996. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0865-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West NA, Crume TL, Maligie MA, Dabelea D. Cardiovascular risk factors in children exposed to maternal diabetes in utero. Diabetologia. 2011;54(3):504–507. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-2008-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pettitt DJ, Aleck KA, Baird HR, Carraher MJ, Bennett PH, Knowler WC. Congenital susceptibility to NIDDM. Role of intrauterine environment. Diabetes. 1988;37(5):622–628. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.5.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Catrina SB, Okamoto K, Pereira T, Brismar K, Poellinger L. Hyperglycemia regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein stability and function. Diabetes. 2004;53(12):3226–3232. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013;93(1):137–188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sada K, Nishikawa T, Kukidome D, Yoshinaga T, Kajihara N, Sonoda K, Senokuchi T, Motoshima H, Matsumura T, Araki E. Hyperglycemia induces cellular hypoxia through production of mitochondrial ROS followed by suppression of aquaporin-1. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(7):e0158619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ornoy A, Reece EA, Pavlinkova G, Kappen C, Miller RK. Effect of maternal diabetes on the embryo, fetus, and children: congenital anomalies, genetic and epigenetic changes and developmental outcomes. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2015;105(1):53–72. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonanez-Organis JG, Godoy-Lugo JA, Hernandez-Palomares ML, Rodriguez-Martinez D, Rosas-Rodriguez JA, Gonzalez-Ochoa G, Virgen-Ortiz A, Ortiz RM. HIF-1alpha and PPARgamma during physiological cardiac hypertrophy induced by pregnancy: transcriptional activities and effects on target genes. Gene. 2016;591(2):376–381. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenchegowda D, Natale B, Lemus MA, Natale DR, Fisher SA. Inactivation of maternal Hif-1alpha at mid-pregnancy causes placental defects and deficits in oxygen delivery to the fetal organs under hypoxic stress. Dev Biol. 2017;422(2):171–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, homeostasis, and disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):537–547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer NV, Kotch LE, Agani F, Leung SW, Laughner E, Wenger RH, Gassmann M, Gearhart JD, Lawler AM, Yu AY, et al. Cellular and developmental control of O2 homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha. Genes Dev. 1998;12(2):149–162. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Bosch-Marce M, Nanayakkara A, Savransky V, Fried SK, Semenza GL, Polotsky VY. Altered metabolic responses to intermitternt hypoxia in mice with partial deficiency of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 a. Physiol Genomics. 2006;25:450–457. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00293.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohuslavova R, Kolar F, Kuthanova L, Neckar J, Tichopad A, Pavlinkova G. Gene expression profiling of sex differences in HIF1-dependent adaptive cardiac responses to chronic hypoxia. J Appl Physiol. 2010;109(4):1195–1202. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00366.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bosch-Marce M, Okuyama H, Wesley JB, Sarkar K, Kimura H, Liu YV, Zhang H, Strazza M, Rey S, Savino L, et al. Effects of aging and hypoxia-inducible factor-1 activity on angiogenic cell mobilization and recovery of perfusion after limb ischemia. Circ Res. 2007;101(12):1310–1318. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang Y, Hickey RP, Yeh JL, Liu D, Dadak A, Young LH, Johnson RS, Giordano FJ. Cardiac myocyte-specific HIF-1alpha deletion alters vascularization, energy availability, calcium flux, and contractility in the normoxic heart. Faseb J. 2004;18(10):1138–1140. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1510fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marfella R, D’Amico M, Di Filippo C, Piegari E, Nappo F, Esposito K, Berrino L, Rossi F, Giugliano D. Myocardial infarction in diabetic rats: role of hyperglycaemia on infarct size and early expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Diabetologia. 2002;45(8):1172–1181. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0882-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bohuslavova R, Skvorova L, Sedmera D, Semenza GL, Pavlinkova G. Increased susceptibility of HIF-1alpha heterozygous-null mice to cardiovascular malformations associated with maternal diabetes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;60:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kopylova E, Noe L, Touzet H. SortMeRNA: fast and accurate filtering of ribosomal RNAs in metatranscriptomic data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(24):3211–3217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(1):15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq–a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(2):166–169. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rouillard AD, Gundersen GW, Fernandez NF, Wang Z, Monteiro CD, McDermott MG, Ma’ayan A. The harmonizome: a collection of processed datasets gathered to serve and mine knowledge about genes and proteins. Database (Oxford) 2016 doi: 10.1093/database/baw100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wessels A, Sedmera D. Developmental anatomy of the heart: a tale of mice and man. Physiol Genomics. 2003;15(3):165–176. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan J, Tank J. Complexity of impaired parasympathetic heart rate regulation in diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(6):1847–1849. doi: 10.2337/db14-0304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramer T, Yamanishi Y, Clausen BE, Forster I, Pawlinski R, Mackman N, Haase VH, Jaenisch R, Corr M, Nizet V, et al. HIF-1alpha is essential for myeloid cell-mediated inflammation. Cell. 2003;112(5):645–657. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00154-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Defer N, Azroyan A, Pecker F, Pavoine C. TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling interplay in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(49):35564–35573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704003200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luo D, Luo Y, He Y, Zhang H, Zhang R, Li X, Dobrucki WL, Sinusas AJ, Sessa WC, Min W. Differential functions of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 and 2 signaling in ischemia-mediated arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(5):1886–1898. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bashey RI, Martinez-Hernandez A, Jimenez SA. Isolation, characterization, and localization of cardiac collagen type VI. Associations with other extracellular matrix components. Circ Res. 1992;70(5):1006–1017. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.70.5.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frangogiannis NG. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(5):255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vlassara H, Striker GE. AGE restriction in diabetes mellitus: a paradigm shift. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(9):526–539. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gutstein DE, Morley GE, Tamaddon H, Vaidya D, Schneider MD, Chen J, Chien KR, Stuhlmann H, Fishman GI. Conduction slowing and sudden arrhythmic death in mice with cardiac-restricted inactivation of connexin43. Circ Res. 2001;88(3):333–339. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.88.3.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tittarelli A, Janji B, Van Moer K, Noman MZ, Chouaib S. The selective degradation of synaptic connexin 43 protein by hypoxia-induced autophagy impairs natural killer cell-mediated tumor cell killing. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(39):23670–23679. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.651547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waza AA, Andrabi K, Hussain MU. Protein kinase C (PKC) mediated interaction between conexin43 (Cx43) and K(+)(ATP) channel subunit (Kir6.1) in cardiomyocyte mitochondria: implications in cytoprotection against hypoxia induced cell apoptosis. Cell Signal. 2014;26(9):1909–1917. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sato T, Haimovici R, Kao R, Li AF, Roy S. Downregulation of connexin 43 expression by high glucose reduces gap junction activity in microvascular endothelial cells. Diabetes. 2002;51(5):1565–1571. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.5.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benes J, Jr, Melenovsky V, Skaroupkova P, Pospisilova J, Petrak J, Cervenka L, Sedmera D. Myocardial morphological characteristics and proarrhythmic substrate in the rat model of heart failure due to chronic volume overload. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2011;294(1):102–111. doi: 10.1002/ar.21280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sedmera D, Neckar J, Benes J, Jr, Pospisilova J, Petrak J, Sedlacek K, Melenovsky V. Changes in myocardial composition and conduction properties in rat heart failure model induced by chronic volume overload. Front Physiol. 2016;7:367. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolwicz SC, Jr, Purohit S, Tian R. Cardiac metabolism and its interactions with contraction, growth, and survival of cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2013;113(5):603–616. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.302095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mwaikambo BR, Yang C, Chemtob S, Hardy P. Hypoxia up-regulates CD36 expression and function via hypoxia-inducible factor-1- and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(39):26695–26707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Semenza GL, Jiang BH, Leung SW, Passantino R, Concordet JP, Maire P, Giallongo A. Hypoxia response elements in the aldolase A, enolase 1, and lactate dehydrogenase A gene promoters contain essential binding sites for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(51):32529–32537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.32529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang J, Sambandam N, Han X, Gross RW, Courtois M, Kovacs A, Febbraio M, Finck BN, Kelly DP. CD36 deficiency rescues lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2007;100(8):1208–1217. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264104.25265.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zygalaki E, Kaklamanis L, Nikolaou NI, Kyrzopoulos S, Houri M, Kyriakides Z, Lianidou ES, Kremastinos DT. Expression profile of total VEGF, VEGF splice variants and VEGF receptors in the myocardium and arterial vasculature of diabetic and non-diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(1–2):82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Holemans K, Gerber RT, Meurrens K, De Clerck F, Poston L, Van Assche FA. Streptozotocin diabetes in the pregnant rat induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Diabetologia. 1999;42(1):81–89. doi: 10.1007/s001250051117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crispi F, Bijnens B, Figueras F, Bartrons J, Eixarch E, Le Noble F, Ahmed A, Gratacos E. Fetal growth restriction results in remodeled and less efficient hearts in children. Circulation. 2010;121(22):2427–2436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.937995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salbaum JM, Kruger C, Zhang X, Delahaye NA, Pavlinkova G, Burk DH, Kappen C. Altered gene expression and spongiotrophoblast differentiation in placenta from a mouse model of diabetes in pregnancy. Diabetologia. 2011;54(7):1909–1920. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2132-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burton GJ, Fowden AL, Thornburg KL. Placental origins of chronic disease. Physiol Rev. 2016;96(4):1509–1565. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Patterson AJ, Xiao D, Xiong F, Dixon B, Zhang L. Hypoxia-derived oxidative stress mediates epigenetic repression of PKCepsilon gene in foetal rat hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;93(2):302–310. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong D, Reece EA, Lin X, Wu Y, AriasVillela N, Yang P. New development of the yolk sac theory in diabetic embryopathy: molecular mechanism and link to structural birth defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lekva T, Michelsen AE, Bollerslev J, Norwitz ER, Aukrust P, Henriksen T, Ueland T. Low circulating pentraxin 3 levels in pregnancy is associated with gestational diabetes and increased apoB/apoA ratio: a 5-year follow-up study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:23. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0345-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lekva T, Michelsen AE, Aukrust P, Henriksen T, Bollerslev J, Ueland T. Leptin and adiponectin as predictors of cardiovascular risk after gestational diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12933-016-0492-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrov VV, Fagard RH, Lijnen PJ. Stimulation of collagen production by transforming growth factor-beta1 during differentiation of cardiac fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. Hypertension. 2002;39(2):258–263. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Heerebeek L, Hamdani N, Handoko ML, Falcao-Pires I, Musters RJ, Kupreishvili K, Ijsselmuiden AJ, Schalkwijk CG, Bronzwaer JG, Diamant M, et al. Diastolic stiffness of the failing diabetic heart: importance of fibrosis, advanced glycation end products, and myocyte resting tension. Circulation. 2008;117(1):43–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.728550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gilkes DM, Bajpai S, Chaturvedi P, Wirtz D, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) promotes extracellular matrix remodeling under hypoxic conditions by inducing P4HA1, P4HA2, and PLOD2 expression in fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(15):10819–10829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.442939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 60.King MK, Coker ML, Goldberg A, McElmurray JH, 3rd, Gunasinghe HR, Mukherjee R, Zile MR, O’Neill TP, Spinale FG. Selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibition with developing heart failure: effects on left ventricular function and structure. Circ Res. 2003;92(2):177–185. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000052312.41419.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spinale FG. Myocardial matrix remodeling and the matrix metalloproteinases: influence on cardiac form and function. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(4):1285–1342. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakano SJ, Siomos AK, Garcia AM, Nguyen H, SooHoo M, Galambos C, Nunley K, Stauffer BL, Sucharov CC, Miyamoto SD. Fibrosis-related gene expression in single ventricle heart disease. J Pediatr. 2017;191(82–90):e82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nin JW, Jorsal A, Ferreira I, Schalkwijk CG, Prins MH, Parving HH, Tarnow L, Rossing P, Stehouwer CD. Higher plasma levels of advanced glycation end products are associated with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in type 1 diabetes: a 12-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):442–447. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peppa M, He C, Hattori M, McEvoy R, Zheng F, Vlassara H. Fetal or neonatal low-glycotoxin environment prevents autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2003;52(6):1441–1448. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.6.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bohuslavova R, Cerychova R, Nepomucka K, Pavlinkova G. Renal injury is accelerated by global hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha deficiency in a mouse model of STZ-induced diabetes. BMC Endocr Disord. 2017;17(1):48. doi: 10.1186/s12902-017-0200-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng K, Ho K, Stokes R, Scott C, Lau SM, Hawthorne WJ, O’Connell PJ, Loudovaris T, Kay TW, Kulkarni RN, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha regulates beta cell function in mouse and human islets. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(6):2171–2183. doi: 10.1172/JCI35846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sung MM, Byrne NJ, Kim TT, Levasseur J, Masson G, Boisvenue JJ, Febbraio M, Dyck JR. Cardiomyocyte-specific ablation of CD36 accelerates the progression from compensated cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2017;312(3):H552–H560. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00626.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hu CJ, Wang LY, Chodosh LA, Keith B, Simon MC. Differential roles of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in hypoxic gene regulation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(24):9361–9374. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9361-9374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yoon YS, Uchida S, Masuo O, Cejna M, Park JS, Gwon HC, Kirchmair R, Bahlman F, Walter D, Curry C, et al. Progressive attenuation of myocardial vascular endothelial growth factor expression is a seminal event in diabetic cardiomyopathy: restoration of microvascular homeostasis and recovery of cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy after replenishment of local vascular endothelial growth factor. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2073–2085. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162472.52990.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chou E, Suzuma I, Way KJ, Opland D, Clermont AC, Naruse K, Suzuma K, Bowling NL, Vlahos CJ, Aiello LP, et al. Decreased cardiac expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptors in insulin-resistant and diabetic States: a possible explanation for impaired collateral formation in cardiac tissue. Circulation. 2002;105(3):373–379. doi: 10.1161/hc0302.102143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Giordano FJ, Gerber HP, Williams SP, VanBruggen N, Bunting S, Ruiz-Lozano P, Gu Y, Nath AK, Huang Y, Hickey R, et al. A cardiac myocyte vascular endothelial growth factor paracrine pathway is required to maintain cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(10):5780–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091415198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hlatky MA, Quertermous T, Boothroyd DB, Priest JR, Glassford AJ, Myers RM, Fortmann SP, Iribarren C, Tabor HK, Assimes TL, et al. Polymorphisms in hypoxia inducible factor 1 and the initial clinical presentation of coronary disease. Am Heart J. 2007;154(6):1035–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR.

Additional file 2: Table S2. Basal left ventricular echocardiographic parameters, heart rate, and body weight of the offspring.

Additional file 3: Table S3. Bioinformatics classification of differentially expressed genes.

Additional file 4: Table S4. List of genes in Venn diagram in Fig. 3.

Additional file 5: Table S5. List of differentially expressed genes with fold change ≥ 30%.

Additional file 6: Table S6. The list of HIF-1 signaling target genes.

Additional file 7: Table S7. The list of the references for genes linked to HIF-1 signalling by manual literature search.

Additional file 8: Table S8. Bioinformatics enrichment analysis using gProfiler: g:GOST Gene Group Functional Profiling tool.

Additional file 9: Table S9. Bioinformatics mammalian phenotype ontology enrichment analysis using MouseMine Analysis Tools.

Additional file 10: Figure S1. RNAseq data validation by RT-qPCR. The values are mean ± SEM (n = 3/group for RNA-Seq, n = 8/group for RT-qPCR).

Additional file 11: Figure S2. Quantification of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells per mm2 of the RV myocardium (a) and septum (b). The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4 individuals/3 sections/group). Two-way ANOVA indicating a significant effect of diabetes (RV: P < 0.0001; septum: P < 0.0001) followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, **** P < 0.0001.

Additional file 12: Figure S3. PECAM-1 expression in the LV. Representative images of staining of PECAM-1 (red) with Hoechst stained cell nuclei (blue) in the LV of 12 week-old offspring (a-d). Scale bar = 50 μm. e-h: Delineated PECAM+ area in the myocardium using Adobe Photoshop. Quantification of PECAM-1 staining determined as a percentage of positive area in the field of view by ImageJ (i). The values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). Statistical significance assessed by two-way ANOVA: genotype effect P = 0.0302, followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple-comparison test with no significant result.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.