Abstract

Heritable bacterial endosymbionts can alter the biology of numerous arthropods. They can influence the reproductive outcome of infected hosts, thus affecting the ecology and evolution of various arthropod species. The spruce bark beetle Pityogenes chalcographus (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) was reported to express partial, unidirectional crossing incompatibilities among certain European populations. Knowledge on the background of these findings is lacking; however, bacterial endosymbionts have been assumed to manipulate the reproduction of this beetle. Previous work reported low-density and low-frequency Wolbachia infections of P. chalcographus but found it unlikely that this infection results in reproductive alterations. The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis of an endosymbiont-driven incompatibility, other than Wolbachia, reflected by an infection pattern on a wide geographic scale. We performed a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening of 226 individuals from 18 European populations for the presence of the endosymbionts Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma, and additionally screened these individuals for Wolbachia. Positive PCR products were sequenced to characterize these bacteria. Our study shows a low prevalence of these four endosymbionts in P. chalcographus. We detected a yet undescribed Spiroplasma strain in a single individual from Greece. This is the first time that this endosymbiont has been found in a bark beetle. Further, Wolbachia was detected in three beetles from two Scandinavian populations and two new Wolbachia strains were described. None of the individuals analyzed were infected with Cardinium and Rickettsia. The low prevalence of bacteria found here does not support the hypothesis of an endosymbiont-driven reproductive incompatibility in P. chalcographus.

Keywords: Wolbachia, Spiroplasma, reproductive incompatibility, endosymbiont, bark beetle

A high number of terrestrial arthropods harbor maternally inherited, intracellular bacterial endosymbionts (Weinert et al. 2015). These bacteria can influence the biology of their hosts in a wide manner, e.g., by altering their reproduction (Engelstädter and Hurst 2009) or enhancing their resistance to viruses, fungi, nematodes, or parasitoids (e.g., Oliver et al. 2003, Teixeira et al. 2008, Martinez et al. 2017). Thus, endosymbionts are important players in the ecology and evolution of insects and other arthropod species (Moran et al. 2008).

One of the most common and widespread endosymbionts that can alter the reproduction of arthropods and filarial nematodes is Wolbachia. It can induce a variety of reproductive phenotypes in host organisms, including cytoplasmatic incompatibility (CI), male killing, parthenogenesis, or feminization (Werren et al. 2008). Among those phenotypes, CI is the most common where mating of a Wolbachia-infected male with a Wolbachia-uninfected female, or a female infected with a different Wolbachia strain, results in embryonic death (Hoffmann and Turelli 1997). The endosymbiont Cardinium also causes various reproductive phenotypes in numerous arthropod hosts (Zchori-Fein and Perlman 2004). It can induce CI, parthenogenesis, and feminization, but can also provide fitness benefits by enhancing the fecundity of its hosts (Weeks et al. 2001, Zchori-Fein et al. 2001, Hunter et al. 2003, Weeks et al. 2003, Weeks and Stouthamer 2004, Zchori-Fein et al. 2004). Another bacterial endosymbiont that can alter the biology of insect hosts is Spiroplasma. It was found to act as reproductive manipulator by expressing a male-killing phenotype in Drosophila flies (Xie et al. 2014) and in a nymphalid butterfly (Jiggins et al. 2000). Furthermore, a Spiroplasma infection can protect Drosophila spp. against natural enemies (Jaenike et al. 2010, Xie et al. 2014). Rickettsia bacteria occur in various terrestrial arthropods (Weinert et al. 2015) with a wide range of effects on host biology (e.g., Sakurai et al. 2005, Zchori-Fein et al. 2006, Himler et al. 2011). They can also express phenotypes with altered reproductive behavior, such as male killing in coleopteran or parthenogenesis in hymenopteran hosts (Lawson et al. 2001, Hagimori et al. 2006).

Bark beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) are key players in forest ecosystems, and some species can have huge economic and ecological impacts on their environment (Grégoire et al. 2015, Raffa et al. 2015). Numerous scolytines express symbiotic relationships with other organisms, such as arthropods, fungi, or bacteria (Hofstetter et al. 2015, Wegensteiner et al. 2015). Associations with bacterial endosymbionts have been described for various bark beetles, but knowledge of effects on host biology is often limited. For example, infections with Wolbachia and Rickettsia can be related to sex determination or oogenesis in bark beetles, however, background on underlying mechanisms is scarce (e.g., Peleg and Norris 1972a,b, Stauffer et al. 1997, Vega et al. 2002, Zchori-Fein et al. 2006, Arthofer et al. 2009, Kawasaki et al. 2010, 2016). The influence of Spiroplasma and Cardinium on the reproduction of scolytines is largely unknown.

Pityogenes chalcographus (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) is a common and widespread bark beetle in the Palearctic. It is oligophagous utilizing various conifers of the family Pinaceae; however, the main host tree in its European range is Norway spruce, Picea abies. Pityogenes chalcographus prefers thin-barked parts of trees, such as upper parts of the trunk or branches. Usually, this beetle infests weakened hosts, for example, trees damaged by wind or snow, or after logging operations. Pityogenes chalcographus is polygamous where one male can mate with up to seven females and one female beetle can deposit about 10 to 26 eggs. After subcortical development young beetles emerge to infest new host trees. This bark beetle can produce up to three generations per year (Schwerdtfeger 1929, Postner 1974).

Reproductive incompatibilities in scolytines are rare. Pityogenes chalcographus is unique among bark beetles studied, in that reproductive incompatibilities among certain European populations have been detected for this species (Führer 1976, 1977). Another remarkable example in this weevil subfamily is the North American mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), where reproductive incompatibilities around the Great Basin Desert have been described (Bracewell et al. 2017).

In P. chalcographus, mating experiments with males and females from certain European populations revealed partial, unidirectional crossing incompatibilities, reflected in a reduced number of offspring in allochthonous (males and females from different populations) compared to autochthonous (males and females from the same population) crosses. A northeastern and a central European lineage of this beetle were proposed and processes of incipient speciation were suggested (Führer 1976, 1977). Knowledge of the background of these findings is lacking; however, bacterial endosymbionts as potential factors have been hypothesized (Riegler 1999, Avtzis 2006, Arthofer et al. 2009).

Previous studies reported a low Wolbachia prevalence in P. chalcographus (Riegler 1999, Avtzis 2006). Arthofer et al. (2009) found Wolbachia only in low titers in European individuals and no geographic infection pattern was observed. Pityogenes chalcographus might harbor an ancient Wolbachia infection that might have been lost over time making it unlikely that this endosymbiont infection affects the reproduction of this bark beetle (Arthofer et al. 2009, 2010). Moreover, evidence suggests a strong, positive relationship between the density of Wolbachia in a host and the level of CI that occurs (Bordenstein and Bordenstein 2011) supporting the hypothesis that low-titer and low-prevalence Wolbachia in P. chalcographus likely does not result in reproductive incompatibilities. Knowledge on the presence and potential role of other secondary endosymbionts present in this bark beetle is lacking.

The aim of this study was to screen for endosymbionts in P. chalcographus that are described to alter the reproduction of arthropods and might be involved in reproductive peculiarities reported by Führer (1976, 1977). Thus, we screened this beetle for the presence of Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In addition, we aimed to detect non-low-titer Wolbachia to supplement previous findings. Subsequently, endosymbiont infections were confirmed and characterized by sequencing positive PCR products. We studied 226 individuals from 18 European populations to find drivers of reproductive alterations in this bark beetle. This is the first study on the prevalence of Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma in P. chalcographus and provides novel insights in the biology of this important beetle species.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Pityogenes chalcographus was collected from breeding systems of infested trees or felled logs of Norway spruce between 1994 and 2009. In total, 226 individuals from 18 European locations were studied (Table 1), covering a wide part of the beetle’s range. To avoid biases due to the maternal inheritance of endosymbionts only one beetle per breeding system was collected and specimens were stored in absolute ethanol at −20°C. DNA was extracted from whole beetles using the ‘GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA miniprep kit’ (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 1.

Overview on Pityogenes chalcographus samples screened for the prevalence of the bacterial endosymbionts Cardinium, Rickettsia, Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia: population origin, coordinates, year of collection, sample size (n), and endosymbiont infection. + endosymbiont-infected samples (with number of infected individuals per population), − endosymbiont-uninfected samples

| Cardinium | Rickettsia | Spiroplasma | Wolbachia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Coordinates | Year | n | +/− | +/− | +/− | +/− |

| Austria, Kalkalpen | 47°56′N, 14°22′E | 2004 | 12 | − | − | − | − |

| Austria, Murau-Neumarkt | 47°07′N, 14°01′E | 2004 | 7 | − | − | − | − |

| Bosnia-Herzegovina, Ingman Mountain | 43°52′N, 18°25′E | 2004 | 28 | − | − | − | − |

| Croatia, Sarborsko | 44°59′N, 15°28′E | 2009 | 26 | − | − | − | − |

| Finland, Jarvenpää | 60°28′N, 25°06′E | 2004 | 10 | − | − | − | − |

| Finland, Kangashäkki | 62°36′N, 25°44′E | 2004 | 13 | − | − | − | + (2) |

| France, Massif Central | 45°01′N, 3°05′E | 2004 | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| Germany, Harz - Hasselfelde | 51°45′N, 11°00′E | 2004 | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| Greece, Drama | 41°08′N, 24°09′E | 2004 | 12 | − | − | + (1) | − |

| Italy, Abetone | 44°08′N, 10°39′E | 2009 | 6 | − | − | − | − |

| Italy, Asiago | 45°52′N, 11°30′E | 2004 | 9 | − | − | − | − |

| Italy, Pavullo | 44°20′N, 10°50′E | 2004 | 30 | − | − | − | − |

| Italy, Tolmezzo | 46°24′N, 13°01′E | 2004 | 6 | − | − | − | − |

| Lithuania, Kaunas | 55°02′N, 24°12′E | 1994 | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| Lithuania, Vilnius | 54°04′N, 25°20′E | 2004 | 12 | − | − | − | − |

| Norway, Rora | 63°50′N, 11°22′E | 2004 | 13 | − | − | − | − |

| Poland, Beskid Slaski | 50°06′N, 18°32′E | 2004 | 5 | − | − | − | − |

| Sweden, Overkalix | 66°19′N, 22°50′E | 2004 | 22 | − | − | − | + (1) |

| Total | 226 | + (1) | + (3) |

PCR Screening for Endosymbionts

PCR screening of P. chalcographus for all four endosymbionts was performed in a total volume of 10 µl using 1× Y-buffer (2 mM, incl. MgCl2), 1 mg/ml BSA, 800 µM dNTP-mix, 0.2 µM symbiont-specific forward and reverse primer, 0.5 U peqGold Taq-DNA-Polymerase ‘all inclusive’ (Peqlab/VWR, Erlangen, Germany), and 1.0 µl template DNA.

To detect Cardinium we used the primers CLO-F1 and CLO-R1, targeting a ~450 bp fragment of the 16S rDNA gene (Weeks et al. 2003). PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s, 72°C for 45 s, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Cardinium-harboring Bemisia tabaci (Gennadius) (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) whiteflies were used as positive controls.

Rickettsia screening was done using the primers 528F and 1044R, targeting a ~500 bp fragment of the 16S rDNA gene (Chiel et al. 2009). PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 45 s, 72°C for 45 s, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. We used Rickettsia-infected individuals of B. tabaci as positive controls.

Samples were screened for Spiroplasma using the primer pair SpixoF/SpixoR, amplifying a ~800 bp fragment of the 16S rDNA gene (Duron et al. 2008). PCR was performed at 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 52°C for 45 s, 72°C for 1 min, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Spiroplasma-harboring Dermanyssus gallinae (De Geer) (Mesostigmata: Dermanyssidae) mites were used as positive controls.

Wolbachia infection was studied using the primer pair 81F/691R, targeting a ~600 bp fragment of the wsp (Wolbachia surface protein) gene (Braig et al. 1998, Zhou et al. 1998). PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 45 s, 72°C for 45 s, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 8 min. Wolbachia-infected specimens of the tephritid fly Rhagoletis cerasi (L.) (Diptera: Tephritidae) were used as positive controls.

PCR products of all endosymbionts were separated by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel stained with GelRed nucleic acid dye (Biotum, Hayward, CA). To avoid false positive results, PCR in all samples where an endosymbiont infection was detected were replicated.

Characterization of Endosymbionts

PCR products of positive samples were Sanger sequenced by a commercial provider (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany). Sequence chromatograms were carefully screened for the presence of ambiguous sites using ChromasLite version 2.1 (Technelysium, Australia). Sequences were edited in GeneRunner version 5.0 (www.generunner.net) and a BLAST search was done using the ‘blastn’ algorithm in GenBank. Sequences were aligned to the top BLAST hits using ClustalX version 2.0 (Larkin et al. 2007). All genotypes were confirmed by sequencing three independent PCR products. Representative sequences for each strain were submitted to GenBank.

Results

Detection of Endosymbionts using PCR

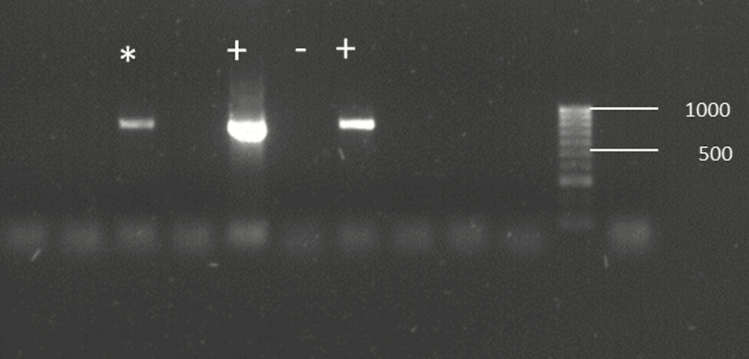

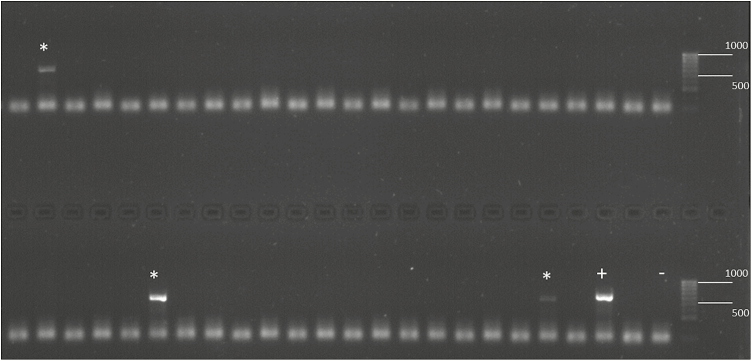

Screening of P. chalcographus for the presence of the endosymbionts Cardinium, Rickettsia, Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia revealed that these bacteria were present in less than 2% of the individuals studied (Table 1). Only one out of 12 P. chalcographus from the Greek population Drama was infected with the bacterium Spiroplasma (Fig. 1). Wolbachia was found in three beetles: in two out of 13 individuals from the Finnish population Kangashäkki and in one out of 22 samples from the Swedish population Overkalix (Table 1, Fig. 2). No Cardinium and no Rickettsia infections were detected (Table 1). Individuals with an endosymbiont infection had amplicons in the same size range as the positive controls (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Detection of Spiroplasma in Pityogenes chalcographus using PCR and electrophoretic separation on a 2% agarose gel stained with GelRed. *Spiroplasma-infected individual, + positive control, − negative control. Numbers indicate fragment size.

Fig. 2.

Detection of Wolbachia in Pityogenes chalcographus using PCR and electrophoretic separation on a 2% agarose gel stained with GelRed. *Wolbachia-infected individual, + positive control, − negative control. Numbers indicate fragment size.

Characterization of Endosymbionts

Sequence chromatograms of all four positive samples had unambiguous single peaks, suggesting infections with only one bacterial strain per individual. The Spiroplasma infection detected in a P. chalcographus individual from Drama/Greece (GenBank accession number: MH232090) has 99% homology to a Spiroplasma found in the weevil Curculio sikkimensis (Heller) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (AB545038, Toju and Fukatsu 2011), differing by four mutations.

Genotyping of Wolbachia from three infected individuals resulted in three different strains: One P. chalcographus individual from Overkalix/Sweden (MH232091) shows 100% identity with the strain wCha-B that was described for P. chalcographus previously (DQ993183, Arthofer et al. 2009). Two beetles from Kangashäkki/Finland were infected by two new Wolbachia strains: One strain (MH232093) has 99% homology to the previously described strain wCha-B (DQ993183, Arthofer et al. 2009), differing by two mutations; this new strain was named wCha-B2. The other strain (MH232092) shows 99% homology to a Wolbachia infection from Chilo suppressalis (Walker) (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) (HQ336511), differing by four mutations; this new strain was named wCha-B3.

Discussion

Here, we screened the bark beetle P. chalcographus for the presence of Cardinium, Rickettsia, Spiroplasma, and Wolbachia. These endosymbionts are known to manipulate the reproduction of several arthropod hosts and could explain previously described unidirectional reproductive incompatibilities in this beetle. We found a low prevalence of the four endosymbionts. A single beetle from a Greek population carried the bacterium Spiroplasma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that Spiroplasma has been described in a bark beetle. Three individuals from two Scandinavian populations were infected with Wolbachia, two of them with two new Wolbachia strains. The low prevalence of Wolbachia and Spiroplasma does not support the hypothesis that heritable bacterial endosymbionts are causing reproductive incompatibilities in P. chalcographus.

Our results confirm previously published data that P. chalcographus is rarely infected with Wolbachia (Riegler 1999, Avtzis 2006, Arthofer et al. 2009) and that this symbiont might not be an important player in the reproductive biology of this bark beetle. Moreover, Wolbachia in P. chalcographus is present mainly in low titers (Arthofer et al. 2009). Since CI is correlated with Wolbachia density (Bordenstein and Bordenstein 2011) it is unlikely that low-titer infections result in reproductive incompatibilities in this beetle (Arthofer et al. 2009, 2010).

Spiroplasma was detected only in one single individual. Therefore, we assume that it is unlikely that this bacterium expresses a phenotype with an altered reproductive mode that affects evolutionary processes in P. chalcographus on a broad geographic scale. Spiroplasma infections are described for various insect orders, such as Diptera, Lepidoptera, and Coleoptera (Jiggins et al. 2000, Weinert et al. 2007, Jaenike et al. 2010, Xie et al. 2014). Our results support the assumption (Duron et al. 2008, Weinert et al. 2015) that many relationships between Spiroplasma and arthropods are still undiscovered.

None of the individuals in this study harbored an infection with Cardinium or Rickettsia. A screening of the whole microbiome of P. chalcographus using Next Generation Sequencing techniques (e.g., Morrow et al. 2017, Vieira et al. 2017), however, could elucidate relationships to any other symbiont of this bark beetle. This could provide potential culprit organisms to explain the previously observed reproductive incompatibilities in P. chalcographus. Further experimentation, e.g., extensive crossing studies or antibiotic treatment, could then be conducted to understand the mechanisms causing incompatibility, thus shedding further light on the evolution and biology of P. chalcographus in Europe.

Although mating experiments in P. chalcographus are laborious (Avtzis et al. 2008) they would add important knowledge to the beetle’s reproductive biology. For example, findings by Führer (1976, 1977) did not show complete incompatibilities among crosses or a clear geographic pattern of altered reproduction. Further, Avtzis et al. (2008) did not detect a distinct genetic basis for reproductive incompatibilities. Therefore, we suggest confirming and re-assessing previous crossing studies, combining them with fine-scale genetic analyses, and relating endosymbiont infections to a reproductive phenotype to elucidate this chapter of the beetle’s biology and to add significant knowledge to the evolution of this weevil subfamily.

Peleg and Norris (1972a,b) reported a scolytine-endosymbiont relationship with potential impacts on the reproductive outcome of the host for the first time. Subsequently, an increasing number of scolytine-endosymbiont associations were described (e.g., Stauffer et al. 1997, Vega et al. 2002, Zchori-Fein et al. 2006, Arthofer et al. 2009, Kawasaki et al. 2010, 2016). Among reproductive manipulators, Wolbachia is the best studied symbiont of bark beetles. This bacterium, e.g., might be involved in the sex determination of some species (Vega et al. 2002, Kawasaki et al. 2010, 2016). Kawasaki et al. (2016) screened various bark beetles and found that haplodiploid species are more often infected with this endosymbiont than diploid species, with infection frequencies ranging from 0 to 100%. However, no general infection pattern and no co-evolutionary relationships between beetle and endosymbiont were found (Kawasaki et al. 2016). In addition to their influence in sex determination, endosymbionts like Wolbachia and Rickettsia can affect the egg production of the scolytine Coccotrypes dactyliperda F. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Zchori-Fein et al. 2006). Finally, many endosymbiont infections that alter the reproduction of bark beetle hosts might still be undiscovered, and future research will shed light on the background and evolutionary impacts of this symbiosis.

In conclusion, our findings confirm that Wolbachia is not likely a reproductive manipulator of P. chalcographus. Moreover, our results suggest that it is improbable that Cardinium, Rickettsia, and Spiroplasma have implications on the evolution of this beetle. If P. chalcographus expressed an endosymbiont-driven incompatibility on a European scale, reflected in a central and northeastern lineage (Führer 1976, 1977), we would expect differences in infection patterns in these regions. For example, southern and central European populations of the tephritid fruit fly R. cerasi were reported to show unidirectional reproductive incompatibilities (Boller et al. 1976). Wolbachia was detected to cause these findings by expressing CI (Riegler and Stauffer 2002) and frequencies of the CI-inducing Wolbachia strain change from 100 to 0% within a few kilometers, reflecting this incompatibility pattern (Boller et al. 1976, Riegler and Stauffer 2002, Schuler et al. 2016). In contrast, the infection pattern found here, as well as by other authors (Arthofer et al. 2009, 2010), does not support an endosymbiont-driven incompatibility in P. chalcographus.

Alternatively, we propose that other processes, e.g., cycles of glacial and interglacial periods (Hewitt 1996), have likely shaped the genetic structure and evolutionary history of P. chalcographus (Avtzis et al. 2008, Bertheau et al. 2013, Schebeck et al. unpublished).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dimitrios N. Avtzis and Coralie Bertheau for providing samples of P. chalcographus, Laurence Mouton, Marie-Thérèse Poirel, Einat Zchori-Fein, and Martha Stock for providing positive controls of the four endosymbionts. This study was financially supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; project number P26749-B25 to C.S. and J-3527-B22 to H.S.). M.S., C.S., and H.S. designed the study. M.S., L.F., M.B., and S.K. conducted lab work and analyzed data. M.S. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to the final version.

References Cited

- Arthofer W., Avtzis D. N., Riegler M., and Stauffer C.. 2010. Mitochondrial phylogenies in the light of pseudogenes and Wolbachia: re-assessment of a bark beetle dataset. Zookeys. 56: 269–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthofer W., Riegler M., Avtzis D. N., and Stauffer C.. 2009. Evidence for low-titre infections in insect symbiosis: Wolbachia in the bark beetle Pityogenes chalcographus (Coleoptera, Scolytinae). Environ. Microbiol. 11: 1923–1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avtzis D. N. 2006. Race differentiation of Pityogenes chalcographus (Coleoptera, Scolytidae): an ecological and phylogeographic approach. PhD dissertation. BOKU University, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Avtzis D. N., Arthofer W., and Stauffer C.. 2008. Sympatric occurrence of diverged mtDNA lineages of Pityogenes chalcographus (Coleoptera, Scolytinae) in Europe. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 94: 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Bertheau C., Schuler H., Arthofer W., Avtzis D. N., Mayer F., Krumböck S., Moodley Y., and Stauffer C.. 2013. Divergent evolutionary histories of two sympatric spruce bark beetle species. Mol. Ecol. 22: 3318–3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boller E. F., Russ K., Vallo V., and Bush G. L.. 1976. Incompatible races of European cherry fruit fly, Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera: Tephritidae), their origin and potential use in biological control. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 20: 237–247. [Google Scholar]

- Bordenstein S. R. and Bordenstein S. R.. 2011. Temperature affects the tripartite interactions between bacteriophage WO, Wolbachia, and cytoplasmic incompatibility. PLoS One. 6: e29106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracewell R. R., Bentz B. J., Sullivan B. T., and Good J. M.. 2017. Rapid neo-sex chromosome evolution and incipient speciation in a major forest pest. Nat. Commun. 8: 1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braig H. R., Zhou W., Dobson S. L., and O’Neill S. L.. 1998. Cloning and characterization of a gene encoding the major surface protein of the bacterial endosymbiont Wolbachia pipientis. J. Bacteriol. 180: 2373–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiel E., Zchori-Fein E., Inbar M., Gottlieb Y., Adachi-Hagimori T., Kelly S. E., Asplen M. K., and Hunter M. S.. 2009. Almost there: transmission routes of bacterial symbionts between trophic levels. PLoS One. 4: e4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duron O., D. Bouchon S. Boutin L. Bellamy L. Zhou J. Engelstädter, and Hurst G. D.. 2008. The diversity of reproductive parasites among arthropods: Wolbachia do not walk alone. BMC Biol. 6: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelstädter J., and Hurst G. D. D.. 2009. The ecology and evolution of microbes that manipulate host reproduction. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 40: 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Führer E. 1976. Fortpflanzungsphysiologische Unverträglichkeit beim Kupferstecher (Pityogenes chalcographus L.) – Ein neuer Ansatz zur Borkenkäferbekämpfung?Forstarchiv. 6: 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Führer E. 1977. Studien über intraspezifische Inkompatibilität bei Pityogenes chalcographus L. (Col., Scolytidae). J. Appl. Entomol. 83: 286–297. [Google Scholar]

- Grégoire J.-C., Raffa K. F., and Lindgren B. S.. 2015. Economics and politics of bark beetles, pp. 585–613. In F. E. Vega and R. W. Hofstetter (eds.), Bark beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hagimori T., Y. Abe S. Date, and Miura K.. 2006. The first finding of a Rickettsia bacterium associated with parthenogenesis induction among insects. Curr. Microbiol. 52: 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt G. M. 1996. Some genetic consequences of ice ages, and their role in divergence and speciation. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 58: 247–276. [Google Scholar]

- Himler A. G., T. Adachi-Hagimori J. E. Bergen A. Kozuch S. E. Kelly B. E. Tabashnik E. Chiel V. E. Duckworth T. J. Dennehy E. Zchori-Fein, et al. 2011. Rapid spread of a bacterial symbiont in an invasive whitefly is driven by fitness benefits and female bias. Science. 332: 254–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A. A., and Turelli M.. 1997. Cytoplasmatic incompatibility in insects, pp. 42–80. In S. L. O’Neill A. A. Hoffmann, and J. H. Werren (eds.), Influential passengers: inherited microorganisms and arthropod reproduction. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstetter R. W., Dinkins-Bookwalter J., Davis T. S., and Klepzig K. D.. 2015. Symbiotic associations of bark beetles, pp. 209–245. In F. E. Vega and R. W. Hofstetter (eds.), Bark beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter M. S., S. J. Perlman, and Kelly S. E.. 2003. A bacterial symbiont in the Bacteroidetes induces cytoplasmic incompatibility in the parasitoid wasp Encarsia pergandiella. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270: 2185–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenike J., R. Unckless S. N. Cockburn L. M. Boelio, and Perlman S. J.. 2010. Adaptation via symbiosis: recent spread of a Drosophila defensive symbiont. Science. 329: 212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiggins F. M., G. D. Hurst C. D. Jiggins J. H. v d Schulenburg, and Majerus M. E.. 2000. The butterfly Danaus chrysippus is infected by a male-killing Spiroplasma bacterium. Parasitology. 120: 439–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y., M. Ito K. Miura, and Kajimura H.. 2010. Superinfection of five Wolbachia in the alnus ambrosia beetle, Xylosandrus germanus (Blandford) (Coleoptera: Curuculionidae). Bull. Entomol. Res. 100: 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y., Schuler H., Stauffer C., Lakatos F., and Kajimura H.. 2016. Wolbachia endosymbionts in haplodiploid and diploid scolytine beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 8: 680–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin M. A., G. Blackshields N. P. Brown R. Chenna P. A. McGettigan H. McWilliam F. Valentin I. M. Wallace A. Wilm R. Lopez, et al. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 23: 2947–2948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson E. T., T. A. Mousseau R. Klaper M. D. Hunter, and Werren J. H.. 2001. Rickettsia associated with male-killing in a buprestid beetle. Heredity. 86: 497–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J., I. Tolosana S. Ok S. Smith K. Snoeck J. P. Day, and Jiggins F. M.. 2017. Symbiont strain is the main determinant of variation in Wolbachia-mediated protection against viruses across Drosophila species. Mol. Ecol. 26: 4072–4084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A., J. P. McCutcheon, and Nakabachi A.. 2008. Genomics and evolution of heritable bacterial symbionts. Annu. Rev. Genet. 42: 165–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow J. L., A. A. G. Hall, and Riegler M.. 2017. Symbionts in waiting: the dynamics of incipient endosymbiont complementation and replacement in minimal bacterial communities of psyllids. Microbiome. 5: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver K. M., J. A. Russell N. A. Moran, and Hunter M. S.. 2003. Facultative bacterial symbionts in aphids confer resistance to parasitic wasps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100: 1803–1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg B. and Norris D. M.. 1972a. Bacterial symbiote activation of insect parthenogenetic reproduction. Nat. New Biol. 236: 111–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg B., and Norris D. M.. 1972b. Symbiotic interrelationships between microbes and ambrosia beetles: VII. Bacterial symbionts associated with Xyleborus ferrugineus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 20: 59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postner M. 1974. Scolytidae (= Ipidae), Borkenkäfer, pp. 334–482. In W., Schwenke (ed.), Die Forstschädlinge Europas, 2. Band. Verlag Paul Parey, Hamburg, Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Raffa K. F., Grégoire J.-C., and Lindgren B. S.. 2015. Natural history and ecology of bark beetles, pp. 1–40. In F. E. Vega and R. W. Hofstetter (eds.), Bark beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Riegler M. 1999. Untersuchungen zu Wolbachia (α-Proteobacteria) in Ips typographus L. (Coleoptera, Scolytidae) und anderen Arten der Rhynchophora. Master thesis. BOKU University, Vienna, Austria. [Google Scholar]

- Riegler M. and Stauffer C.. 2002. Wolbachia infections and superinfections in cytoplasmically incompatible populations of the European cherry fruit fly Rhagoletis cerasi (Diptera, Tephritidae). Mol. Ecol. 11: 2425–2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai M., R. Koga T. Tsuchida X. Y. Meng, and Fukatsu T.. 2005. Rickettsia symbiont in the pea aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum: novel cellular tropism, effect on host fitness, and interaction with the essential symbiont Buchnera. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71: 4069–4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler H., K. Köppler S. Daxböck-Horvath B. Rasool S. Krumböck D. Schwarz T. S. Hoffmeister B. C. Schlick-Steiner F. M. Steiner A. Telschow, et al. 2016. The hitchhiker’s guide to Europe: the infection dynamics of an ongoing Wolbachia invasion and mitochondrial selective sweep in Rhagoletis cerasi. Mol. Ecol. 25: 1595–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtfeger F. 1929. Ein Beitrag zur Fortpflanzungsbiologie des Borkenkäfers Pityogenes chalcographus L. J. Appl. Entomol. 15: 335–427. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer C., van Meer M. M. M., and Riegler M.. 1997. The presence of the Protobacteria Wolbachia in European Ips typographus (Col., Scolytidae) populations and the consequences for genetic data. Mitt. Dtsch. Ges. Allg. Angew. Entomol. 11: 709–711. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira L., A. Ferreira, and Ashburner M.. 2008. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol. 6: e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toju H. and Fukatsu T.. 2011. Diversity and infection prevalence of endosymbionts in natural populations of the chestnut weevil: relevance of local climate and host plants. Mol. Ecol. 20: 853–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega F. E., Benavides P., Stuart J. A., and O’Neill S. L.. 2002. Wolbachia infection in the coffee berry borer (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 95: 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira A. S., M. O. Ramalho C. Martins V. G. Martins, and Bueno O. C.. 2017. Microbial communities in different tissues of Atta sexdens rubropilosa leaf-cutting ants. Curr. Microbiol. 74: 1216–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks A. R. and Stouthamer R.. 2004. Increased fecundity associated with infection by a Cytophaga-like intracellular bacterium in the predatory mite, Metaseiulus occidentalis. Proc. Biol. Sci. 271 (Suppl 4): S193–S195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks A. R., F. Marec, and Breeuwer J. A.. 2001. A mite species that consists entirely of haploid females. Science. 292: 2479–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks A. R., R. Velten, and Stouthamer R.. 2003. Incidence of a new sex-ratio-distorting endosymbiotic bacterium among arthropods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 270: 1857–1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegensteiner R., Wermelinger B., and Herrmann M.. 2015. Natural enemies of bark beetles: predators, parasitoids, pathogens, and nematodes, pp. 247–304. In F. E. Vega and R. W. Hofstetter (eds.), Bark beetles: biology and ecology of native and invasive species. Academic Press, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert L. A., M. C. Tinsley M. Temperley, and Jiggins F. M.. 2007. Are we underestimating the diversity and incidence of insect bacterial symbionts? A case study in ladybird beetles. Biol. Lett. 3: 678–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinert L. A., E. V. Araujo-Jnr M. Z. Ahmed, and Welch J. J.. 2015. The incidence of bacterial endosymbionts in terrestrial arthropods. Proc. Biol. Sci. 282: 20150249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werren J. H., L. Baldo, and Clark M. E.. 2008. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6: 741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., S. Butler G. Sanchez, and Mateos M.. 2014. Male killing Spiroplasma protects Drosophila melanogaster against two parasitoid wasps. Heredity. 112: 399–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zchori-Fein E. and Perlman S. J.. 2004. Distribution of the bacterial symbiont Cardinium in arthropods. Mol. Ecol. 13: 2009–2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zchori-Fein E., Y. Gottlieb S. E. Kelly J. K. Brown J. M. Wilson T. L. Karr, and Hunter M. S.. 2001. A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 12555–12560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zchori-Fein E., S. J. Perlman S. E. Kelly N. Katzir, and Hunter M. S.. 2004. Characterization of a ‘Bacteroidetes’ symbiont in Encarsia wasps (Hymenoptera: Aphelinidae): proposal of ‘Candidatus Cardinium hertigii’. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 54: 961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zchori-Fein E., Borad C., and Harari A. R.. 2006. Oogenesis in the date stone beetle, Coccotrypes dactyliperda, depends on symbiotic bacteria. Physiol. Entomol. 31: 164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., F. Rousset, and O’Neil S.l. 1998. Phylogeny and PCR-based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc. Biol. Sci. 265: 509–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]