Abstract

Objective

To examine the internal consistency and distribution of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) scores to inform modification of the measure.

Methods

This cross-sectional study included 617 participants with a tic disorder (516 children and 101 adults), who completed an age-appropriate diagnostic interview and the YGTSS to evaluate tic symptom severity. The distributions of scores on YGTSS dimensions were evaluated for normality and skewness. For dimensions that were skewed across motor and phonic tics, a modified Delphi consensus process was used to revise selected anchor points.

Results

Children and adults had similar clinical characteristics, including tic symptom severity. All participants were examined together. Strong internal consistency was identified for the YGTSS Motor Tic score (α = 0.80), YGTSS Phonic Tic score (α = 0.87), and YGTSS Total Tic score (α = 0.82). The YGTSS Total Tic and Impairment scores exhibited relatively normal distributions. Several subscales and individual item scales departed from a normal distribution. Higher scores were more often used on the Motor Tic Number, Frequency, and Intensity dimensions and the Phonic Tic Frequency dimension. By contrast, lower scores were more often used on Motor Tic Complexity and Interference, and Phonic Tic Number, Intensity, Complexity, and Interference.

Conclusions

The YGTSS exhibits good internal consistency across children and adults. The parallel findings across Motor and Phonic Frequency, Complexity, and Interference dimensions prompted minor revisions to the anchor point description to promote use of the full range of scores in each dimension. Specific minor revisions to the YGTSS Phonic Tic Symptom Checklist were also proposed.

Empirically supported interventions for Tourette disorder (TD) have been established in randomized clinical trials (RCTs). Entry criteria in RCTs and treatment guidelines rely on accurate assessment of tic severity for participant selection and empirically supported treatment recommendations.1–3 Thus, optimal precision in measuring tic severity is essential for clinical care and research. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) is a multidimensional, clinician-rated scale that measures tic severity4 and is commonly used as a primary outcome measure in RCTs.5–7,17 There have been 5 published psychometric evaluations of the YGTSS.4,8–11 These studies have shown that the YGTSS Total Tic score has excellent internal consistency (α = 0.93–0.99),8,12 excellent interrater reliability (intraclass correlations = 0.84–0.95),4,12 and good test–retest reliability.8 The YGTSS Total Tic score has also demonstrated good convergent validity4,8 and discriminant validity from measures of anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) severity, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) (r = 0.01–0.36).4,8 Finally, the motor and vocal, 2-factor structure has been supported in all 5 studies.4,8,10–12

Despite their strengths, these prior reports have been relatively small, single-site studies, which limits the generalization of the findings. Moreover, the small sample sizes do not allow detailed examination of the scale dimensions. This report examines the internal consistency and distribution of YGTSS component scores and dimensions in a large, multisite sample of children and adults. Based on these findings, strategic revisions are offered designed to increase the precision of the YGTSS.

Methods

Participants

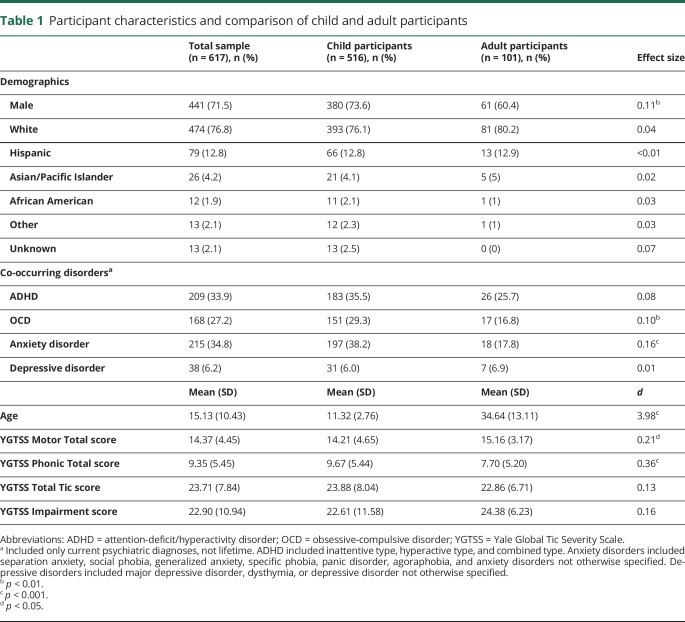

Participants included 617 individuals diagnosed with a DSM-IV tic disorder (552 Tourette syndrome, 46 chronic motor tic disorder, 5 chronic vocal tic disorder, and 14 transient tic disorder) that were recruited from 7 US academic TD and OCD specialty clinics. Participants were ascertained in routine clinical care or via participation in a clinical trial (University of California Los Angeles, n = 181; University of South Florida, n = 207; University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, n = 66; Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, n = 47; John Hopkins University, n = 41; University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, n = 40; Yale Child Study Center, n = 35).5,6,13–19 The sample was predominantly male and Caucasian (see table 1 for demographic and clinical characteristics). The average age of participants was 15 ± 10 years (range 5–69). Co-occurring psychiatric conditions were common, with 64% of participants meeting diagnostic criteria for one or more of the following disorders: ADHD, OCD, non-OCD anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and comparison of child and adult participants

Measures

Psychiatric diagnoses

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined by an experienced multidisciplinary team at each site (e.g., child psychiatrist, psychologist, psychiatric nurse practitioner). In 410 (66.4%) cases, the clinical assessment was supported by an age-appropriate structured diagnostic interview administered by a trained clinician (i.e., Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule–Parent and Child Version [ADIS-C/P],20,21 n = 157; the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV [SCID],22 n = 122; Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders [K-SADS], n = 106; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-KID [MINI-KID],23 n = 25). In the remaining 207 cases, 2 doctoral-level psychologists or child psychiatrists applied a best estimate procedure to establish consensus on diagnoses using all available information.24

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale

The YGTSS is a clinician-rated measure of tic severity over the last 7–10 days that has a stable factor structure9 and excellent psychometric properties.4,8 The motor and phonic tics are rated separately on a 0–5 scale across 5 dimensions: number, frequency, intensity, complexity, and interference. Although motor and phonic tics are rated separately, the anchor point descriptions used to guide scoring are the same for both motor and phonic domains. The scores from each dimension (number, frequency, intensity, complexity, and interference) are summed to produce the Total Motor Tic score (range 0–25), the Total Phonic Tic score (range 0–25), and the combined Total Tic score (range 0–50). The scale also includes a separate Impairment scale that reflects overall tic-related impairment (range 0–50).

Procedures

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

Local institutional review boards approved all study procedures for each research protocol. After explaining study procedures, adult participants provided consent and a parent provided permission for minors (with minor assent). Participants (and their parents for youth) completed clinician-administered measures to assess psychiatric diagnoses (ADIS-C/P, SCID, K-SADS, MINI-KID, or clinical interview). The same or another clinician trained to reliability administered the YGTSS to assess tic symptom severity. Supervision on assessments varied slightly across protocols. However, all raters received regular supervision from investigators with extensive TD assessment experience at the local study site, or, for multisite trials, through monthly teleconference calls.

Analytic plan

First, descriptive statistics characterized the demographics, co-occurring psychiatric conditions, tic symptom severity, and tic-related impairment of the sample. Second, to check for age differences, χ2 and t tests compared clinical and demographic differences between youth and adults. p Values and effect sizes were calculated (Cramer V for categorical and Cohen d for continuous comparisons). Third, Cronbach α examined the internal consistency of the YGTSS Motor Tic score, YGTSS Phonic Tic score, YGTSS Total Tic score, and YGTSS Total Tic and Impairment score. Fourth, we examined the distribution of the Total Motor, Total Phonic, and Total Tic scores, the Impairment score, and individual YGTSS severity items. For an initial evaluation on the normality of these individual and summary scores, we used Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Because these normality tests may be unreliable for larger sample sizes,25 we also used z scores to identify the magnitude of skewness (i.e., degree of asymmetry in the distributions). z Scores larger than 1.96 were considered significant. Negatively skewed distributions have a longer tail on the left that indicates more frequent use of higher scores (i.e., the median > mean). By contrast, positively skewed distributions have a longer tail on the right, reflecting more frequent use of lower scores (median < mean). Means, SDs, and distributions were examined to develop suggestions on strategic revisions of the YGTSS. Using a modified Delphi method, consensus was achieved through an iterative process.26 The measurement concerns and initial anchor point revisions were proposed by 2 study authors (J.F.M., L.S.). These concerns and proposals were independently reviewed by a panel of experts (other authors of this report). Expert panel members then provided independent comments and feedback that were integrated and summarized into a second and third round of anchor point revisions. The panel approved the appropriateness of the final set of revisions.

Data availability

Study data for the primary analyses presented in this report are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding and senior author.

Results

Participants

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the sample. Compared to the adult sample (≥18 years), youth <18 years of age had a higher proportion of male participants, higher prevalence of OCD and anxiety disorders, and a 2-point higher mean score on Total Phonic Tic score. Other than these minor differences, the adult and pediatric samples were similar. Thus, the adult and pediatric samples were combined.

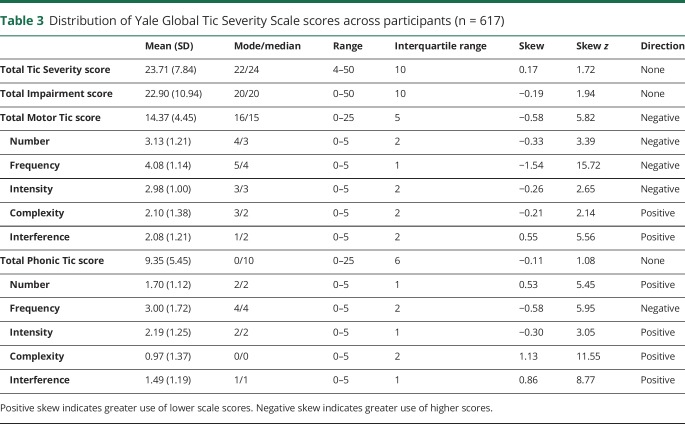

Internal consistency of YGTSS summary scores

The internal consistency for Total Motor, Total Phonic, and Total Tic scores suggested solid coherence of the subscale scores and the Total Tic score (table 2).27 In addition, one-by-one removal of individual dimension scores produced internal consistencies that suggest that no single item was a threat to the overall internal consistency of the scale (table 2).

Table 2.

Internal consistencies of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) scores (n = 617)

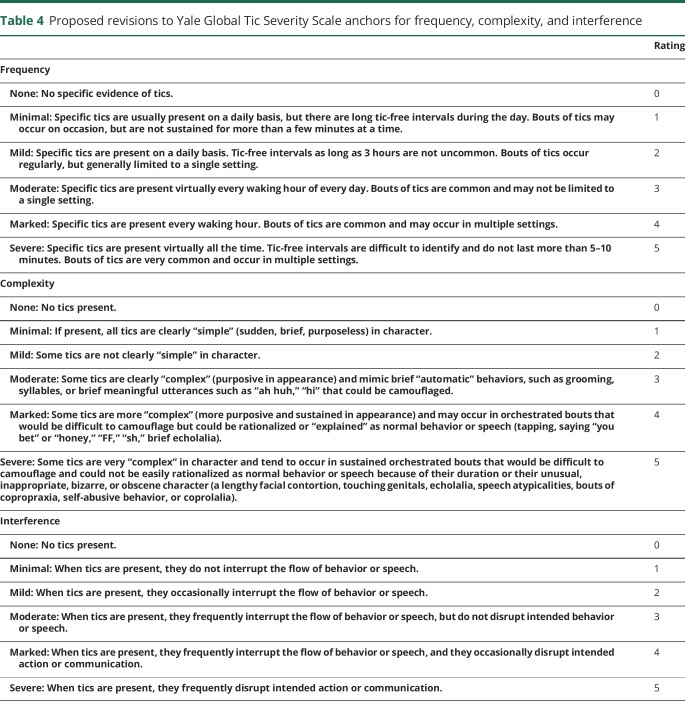

Distribution of YGTSS scores

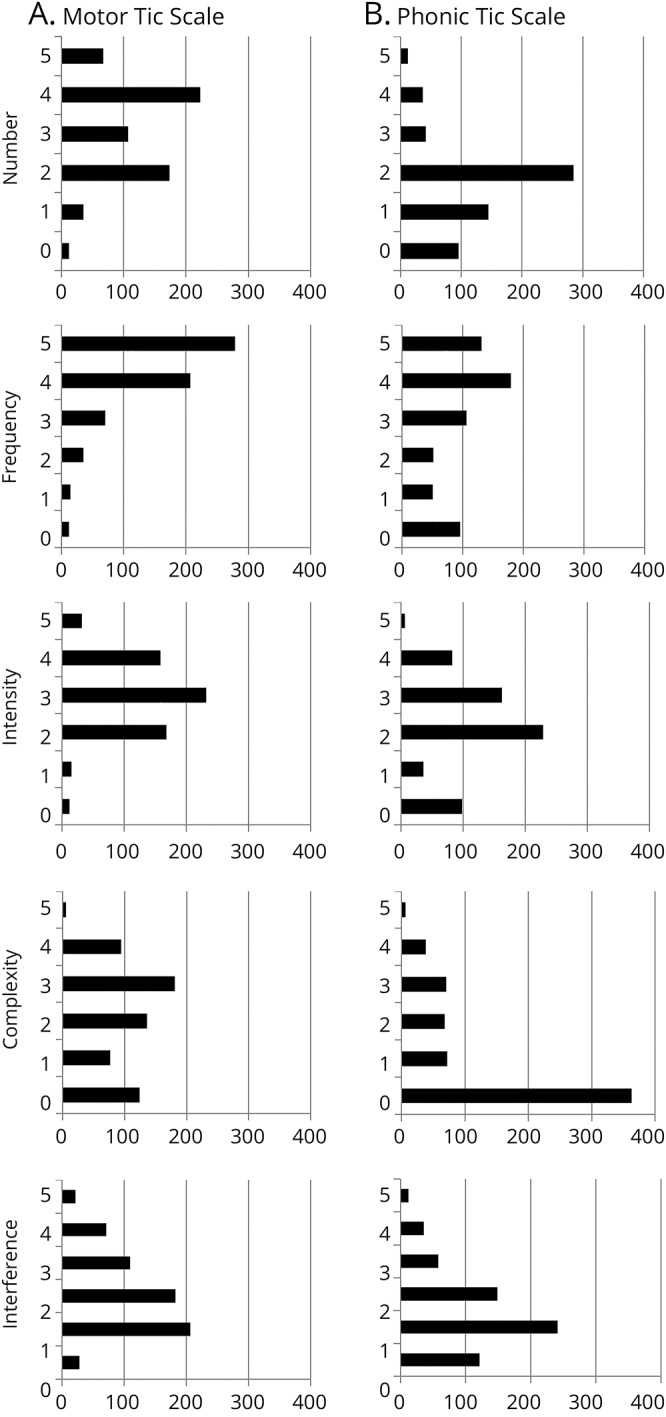

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics and distribution for YGTSS Total Motor, Total Phonic, and Total Tic Impairment scores, and individual YGTSS dimension scales (figure e-1, links.lww.com/WNL/A422, presents distribution of Impairment scores). Using a z score of 1.96 to define skewness, the Total Phonic Tic score, Total Tic score, and Impairment score did not depart from a normal distribution. The Total Motor Tic score showed a negative skew (infrequent use of lower scores). At the individual dimension level, all 5 Motor scores and all 5 Phonic scores were significantly skewed (table 3 and figure 1). Across the Motor and Phonic dimensions, both positive and negative skewness were observed. Furthermore, some Motor Tic and Phonic Tic dimensions were skewed in opposite directions (e.g., Motor and Phonic Number dimension). Because anchor point descriptions serve the same Motor and Phonic tic dimension, any revision to the anchor point description could have contrary effects. For example, a revision to the Number dimension would have opposing effects on Motor and Phonic tic severity. As shown in table 3, 3 dimensions (Frequency, Complexity, and Interference) were significantly skewed in the same direction across Motor and Phonic tic dimensions. The Frequency dimension was negatively skewed for Motor and Phonic tic dimensions (infrequent use of lower scores). Complexity and Interference were positively skewed for Motor and Phonic dimensions (infrequent use of higher scores). Based on these observations, the following minor revisions to the YGTSS Frequency, Complexity, and Interference dimensions were undertaken.

Table 3.

Distribution of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale scores across participants (n = 617)

Figure 1. Distribution of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale item scores in the sample of 617 children and adults with tic disorders.

(A) Motor Tic scale. (B) Phonic Tic scale.

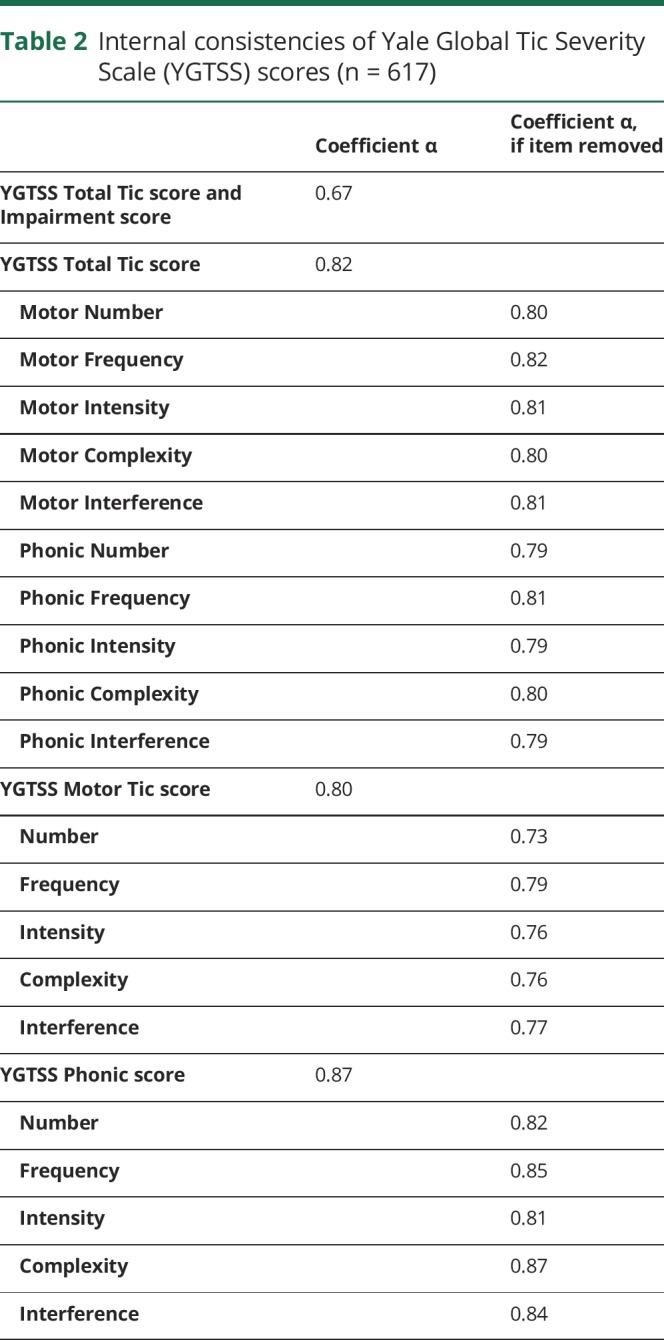

Standardization of anchors across dimensions

To support consistency across dimensions, we suggest using the same qualitative designations: none, minimal, mild, moderate, marked, and severe for scores of 0–5, respectively.

Tic Frequency dimension

As shown in table 3, the mean score for Motor Frequency was 4.08 and Phonic Frequency was 3.00. Although a score of 1 was rarely used, scores of 4 and 5 predominate (figure 1). These observations are consistent with the significant negative skew of this dimension (infrequent use of lower scores). Based on these observations, the anchor point description for the score of 1 on the Frequency dimension was dropped. In the revised set of anchor points (table 4 and table e-1, links.lww.com/WNL/A423), the 3 key elements of the Frequency dimension (duration of tic-free intervals, frequency of tic bouts, and whether the bouts of tics occur in 1 or more settings) are presented incrementally for scores 1–5. The phrase in the original anchor description “periods of sustained bouts” has been removed from descriptions of moderate or marked, as it is arguable that the expression “sustained bouts” is captured in the Complexity dimension.

Table 4.

Proposed revisions to Yale Global Tic Severity Scale anchors for frequency, complexity, and interference

Tic Complexity dimension

The original description for a Complexity score of zero read “If present, all tics are clearly ‘simple’ (sudden, brief, purposeless) in character.” This description is unlike any other zero score on YGTSS dimensions, where a score of zero is “none” or “no tics present.” To match the other dimensions, we inserted “No tics present” for the Complexity score of 0 (tables 4 and e-1). This should remedy the high frequency of zeros for the Motor and Phonic Complexity items (figure 1). The former description of 0 (i.e., “If present, all tics are clearly ‘simple’ [sudden, brief, purposeless] in character”) is now aligned with a score of 1 (minimal); the former description for a score of 1 (borderline) is now aligned with a score of 2. The description of moderate (score of 3) is similar to the original, except that the wording “may occur in orchestrated bouts” was removed. The mention of orchestrated bouts is reserved for ratings of marked and severe (scores of 4 and 5, respectively). Scores of marked and severe are delineated by the presence of behavior that could or could not be explained as normal behavior due to the extreme nature of the behavior.

Tic Interference dimension

The Interference dimension turns on 2 elements: whether tics interrupt the flow of behavior or speech and whether tics actually disrupt intended action or speech. The descriptions for minimal and mild items were not changed. However, to distinguish the anchor point for moderate, we added the phrase “but do not disrupt intended behavior or speech” (table 4). Descriptions of marked and severe were not changed.

Tic Number dimension

The Number dimension showed a negative skew for Motor (infrequent use of lower scores) and a positive skew for Phonic (infrequent use of higher scores). Thus, anchor point revision would not be useful. As shown in figure 1, the 2 most common Phonic Tic Number scores in this sample were 1 (single phonic tic) or 2 (2–5 multiple discrete tics). The score of 3 (>5 multiple discrete tics) was rarely used. Although it may be possible that individuals with TD have a greater diversity of motor tics than phonic tics, the difference in the Number scores may be attributed to the limited number of examples on the YGTSS Phonic Tic Symptoms Checklist. In addition, some entries on the Phonic Symptom Checklist are categories rather than separate tics (e.g., animal noises rather than a list of specific noises). By contrast, the Motor Symptom Checklist is more detailed. In order to reduce the differences between Motor and Phonic Checklists, the revised YGTSS includes a longer list of phonic tic symptoms based on commonly endorsed tics in the Comprehensive Behavioral Intervention for Tics trials (e.g., snorting, gulping, whistling). Rater training should remind clinicians that each phonic tic should be counted separately when making ratings on the Number dimension.

Discussion

This article examines the internal consistency and distribution of YGTSS tic severity scores in a well-characterized sample of children and adults with TD. To our knowledge, this is the largest sample of participants with TD evaluated using the YGTSS. Consistent with prior research,28 only minor differences between children and adults with TD were observed. The YGTSS Total Motor Tic score, Total Phonic Tic score, and Total Tic score showed good internal consistency across component scales (α values ranged from 0.82 to 0.87), and no improvement in internal consistency was observed if a specific item was removed from the scale. These observations are consistent with prior reports.4,8,10–12 Thus, the findings support the internal consistency of the YGTSS, and support its use as a measure of tic symptom severity in children and adults.

The overall aim of the minor anchor point revisions to the YGTSS was to promote use of the entire range of these scales. For the negatively skewed distribution of Motor and Phonic Tic Frequency (infrequent use of lower scores), revisions to the anchor point descriptions are intended to promote use of lower severity scores on these dimensions (table 4). Briefly, the description for a score of 1 was dropped and a more severe description was provided for the score of 5. Scores in between 1 and 5 were dropped 1 unit without changing the anchor point descriptions. To repair the positively skewed distribution of the Motor and Phonic Tic Complexity dimension (infrequent use of higher scores), we revised the score of zero to be consistent with all other YGTSS dimensions to read “no tics present.” This revision shifted the former anchor point descriptions upward by 1 unit, and called for minor clarification to differentiate scores for 4 and 5. Finally, the positively skewed distribution of the Motor and Phonic Tic Interference dimension implied that the anchor points needed revision to capture incremental description on interruption and disruption of intended behavior and speech. These proposed minor revisions are offered to improve the precision of the YGTSS, and do not controvert the reliability and validity of findings from prior studies using this measure. Based on discussion and final consensus of our expert panel, the revised YGTSS (referred to as the YGTSS-Revised [YGTSS-R]) is recommended for use in clinical practice and research. A copy of the YGTSS-R can be obtained online or from J.F.L. or L.S.

These study findings need to be considered in light of several limitations. First, these participants were recruited from TD and OCD specialty clinics and may not generalize to the wider populations with TD. Second, the sample consisted primarily of patients with TD, which may have contributed to the use of higher scores on some YGTSS dimensions. However, our sample appears similar to samples in prior psychometric evaluations of the YGTSS. Thus, our sample appears representative of cases in clinical practice. Finally, although YGTSS raters were trained to reliability, we did not examine interrater or test–retest reliability across sites and raters.

The YGTSS is the most commonly accepted outcome measure for tic symptom severity in children and adults with TD. The proposed revisions to the YGTSS do not change the overall architecture of the scale, or controvert the reliability and validity of the original scale. These strategic revisions expand the Phonic Tic Symptom Checklist and anchor points for 3 YGTSS dimensions to promote full use of scales for these dimensions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the children and parents who participated in these research projects.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ADIS-C/P

Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule–Parent and Child Version

- DSM-IV

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition

- K-SADS

Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders

- MINI-KID

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview-KID

- OCD

obsessive-compulsive disorder

- RCT

randomized clinical trial

- SCID

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

- TD

Tourette disorder

- YGTSS

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale

- YGTSS-R

Yale Global Tic Severity Scale–Revised

Author contributions

Dr. McGuire had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, and Scahill. Acquisition of data: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts, Woods, Walkup, Peterson, Wilhelm, Lewin, McCracken, and Scahill. Analysis and interpretation of data: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts, Woods, Walkup, Peterson, Wilhelm, Lewin, McCracken, Leckman, and Scahill. Drafting of the manuscript: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Woods, Walkup, and Scahill. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts, Woods, Walkup, Peterson, Wilhelm, Lewin, McCracken, Leckman, and Scahill. Statistical analysis: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, and Scahill. Obtained funding: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts, Woods, Walkup, Peterson, Wilhelm, Lewin, McCracken, Leckman, and Scahill. Administrative, technical, or material support: Drs. McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts, Woods, Walkup, Peterson, Wilhelm, Lewin, McCracken, Leckman, and Scahill.

Study funding

This work was supported in part by grants or contracts to Dr. McGuire (Tourette Association of America [TAA], American Academy of Neurology, and American Brain Foundation), Dr. Piacentini (R01MH070802, TAA), Dr. Murphy (U01 DD000509), Dr. Wilhelm (R01MH069877), Dr. Peterson (RO1MH069875), Dr. Woods (TAA), Dr. McCracken (T32MH073517, P50MH077248), and Dr. Scahill (R01MH069874). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIMH, NIH, or other grant organizations.

Disclosure

J. McGuire reports receiving research support from the Tourette Association of America (TAA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American Brain Foundation (ABF). He has also received royalties from Elsevier. J. Piacentini has received grant or research support from the NIMH, Pfizer Pharmaceuticals through the Duke University Clinical Research Institute CAPTN Network, Psyadon Pharmaceuticals, and the TAA. He has received financial support from the Petit Family Foundation and the Tourette Syndrome Association Center of Excellence Gift Fund. He has received royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press. He has served on the speakers' bureau of the TAA, the International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation (IOCDF), and the Trichotillomania Learning Center (TLC). E. Storch has received research support from the NIH, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, IOCDF, and All Children's Hospital Research Foundation. He reports receiving royalties from Elsevier Publications, Springer, American Psychological Association, John Wiley & Sons Inc., and Lawrence Erlbaum. He has been a consultant for Prophase Inc and Rijuin Hospital in China, and serves on the speaker's bureau and scientific advisory board for the IOCDF. He also reports receiving research support from the All Children's Hospital Guild Endowed Chair. T. Murphy has received research funding from Auspex Pharmaceuticals, NIMH, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd., AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Massachusetts General Hospital, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Neurocrine Biosciences, PANDAS Network, and Psyadon Pharmaceuticals. E. Ricketts has received research support from the TAA and NIMH. D. Woods has received speaker's honoraria from the TAA and royalties from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press. J. Walkup has received research support from the Hartwell Foundation and the TAA. He is an unpaid advisor to the Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA), the TLC, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. He has received royalties for books from Guilford Press and Oxford University Press and educational materials from Wolters Kluwer. He has served as a paid speaker for the Tourette Syndrome–Centers for Disease Control and Prevention outreach educational programs, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the American Psychiatric Association. A. Peterson has received research support and speaker's honoraria from the TAA and receives royalties from Oxford University Press. S. Wilhelm has received research support in the form of free medication and matching placebo for NIMH–funded studies from Forest Laboratories, presenter for the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy in educational programs supported through independent medical education grants from pharmaceutical companies, and salary support from Novartis. She receives royalties from Elsevier Publications, Springer Publications, Guilford Publications, New Harbinger Publications, and Oxford University Press, and speaking honoraria from the IOCDF and the TAA. She received payment from the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies for her role as Associate Editor for Behavior Therapy as well as from John Wiley & Sons, Inc. for her role as Associate Editor for Depression & Anxiety. A. Lewin reports receiving research support from the All Children's Hospital Research Foundation, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and IOCDF; serving on the speaker's bureau for the TAA and IOCDF; receiving travel support from the TAA, American Psychological Association, ADAA, NIMH, and Rogers Memorial Hospital; receiving consulting fees from Bracket and Prophase Inc.; receiving book royalties from Springer; receiving honoraria from Oxford Press, Children's Tumor Foundation, and University of Central Oklahoma; and being on the scientific and clinical advisory board for the IOCDF and the board of directors for the Society for Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology and American Board of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. J. McCracken has received grant or research support from NIH, Seaside Therapeutics, Roche, and Otsuka. He has served as a consultant to BioMarin and PharmaNet. J. Leckman serves on the scientific advisory boards of the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, the European Multicentre Tics in Children Studies, the National Organization for Rare Diseases, Fondazione Child, and How I Decide. He has also received royalties from John Wiley and Sons, McGraw-Hill, and Oxford University Press. L. Scahill has served as a consultant for Roche, Neuren, Bracket, CB Partners, and Supernus and participates in the Speakers Bureau of the TAA. He has received royalties from Oxford and Guilford. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosure.

References

- 1.Murphy TK, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Stock S. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with tic disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:1341–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verdellen C, van de Griendt J, Hartmann A, Murphy T, Group EG. European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders: part III: behavioural and psychosocial interventions. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;20:197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steeves T, McKinlay B, Gorman D, et al. Canadian guidelines for the evidence-based treatment of tic disorders: behavioural therapy, deep brain stimulation, and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Can J Psychiatry 2012;57:144–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT, et al. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: initial testing of a clinician-rated scale of tic severity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1989;28:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;303:1929–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, et al. Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scahill L, Leckman J, Schultz R, Katsovich L, Peterson B. A placebo-controlled trial of risperidone in Tourette syndrome. Neurology 2003;60:1130–1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, et al. Reliability and validity of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Psychol Assess 2005;17:486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Storch EA, Murphy TK, Fernandez M, et al. Factor-analytic study of the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale. Psychiatry Res 2007;149:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stefanoff P, Wolańczyk T. Validity and reliability of Polish adaptation of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) in a study of Warsaw schoolchildren aged 12-15. Przegl Epidemiol 2004;59:753–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung SJ, Lee JS, Yoo TI, et al. Development of the Korean form of Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: a validity and reliability study. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assn. 1998;37:942–951. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Lopez R, Perea-Milla E, Romero-Gonzalez J, et al. Spanish adaptation and diagnostic validity of the Yale Global Tics Severity Scale. Rev Neurol 2007;46:261–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGuire JF, McBride N, Piacentini J, et al. The premonitory urge revisited: an individualized premonitory urge for tics scale. J Psychiatr Res 2016;83:176–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire JF, Arnold E, Park JM, et al. Living with tics: reduced impairment and improved quality of life for youth with chronic tic disorders. Psychiatry Res 2015;225:571–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCracken JT, Suddath R, Chang S, Thakur S, Piacentini J. Effectiveness and tolerability of open label olanzapine in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2008;18:501–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ricketts EJ, Goetz AR, Capriotti MR, et al. A randomized waitlist-controlled pilot trial of voice over Internet protocol-delivered behavior therapy for youth with chronic tic disorders. J Telemed Telecare 2016;22:153–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGuire JF, Hanks C, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Murphy TK. Social deficits in children with chronic tic disorders: phenomenology, clinical correlates and quality of life. Compr Psychiatry 2013;54:1023–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanks CE, McGuire JF, Lewin AB, Storch EA, Murphy TK. Clinical correlates and mediators of self-concept in youth with chronic tic disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2016;47:64–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piacentini J, Chang S, Barrios V, McCracken J. Habit reversal training for childhood tic disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Paper presented at Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy Meeting 2002; Reno, NV.

- 20.Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and Parent Versions. San Antonio, TX: Graywinds Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverman WK, Saavedra LM, Pina AA. Test-retest reliability of anxiety symptoms and diagnoses with anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: child and parent versions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, et al. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leckman JF, Sholomskas D, Thompson D, Belanger A, Weissman MM. Best estimate of lifetime psychiatric diagnosis: a methodological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:879–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod 2013;38:52–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, Burnand B, LaCalle JR. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User's Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND CORP; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychol Assess 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuire JF, Nyirabahizi E, Kircanski K, et al. A cluster analysis of tic symptoms in children and adults with Tourette syndrome: clinical correlates and treatment outcome. Psychiatry Res 2013;210:1198–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Study data for the primary analyses presented in this report are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding and senior author.