Abstract

Several developmental windows, including placentation, must be negotiated to establish and maintain pregnancy. Impaired placental function can lead to pre-eclampsia and/or intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), resulting in increased infant mortality and morbidity. It has been hypothesized that chorionic somatomammotropin (CSH), plays a significant role in fetal development, potentially by modifying maternal and fetal metabolism. Recently, using lentiviral-mediated in vivo RNA interference in sheep, we demonstrated significant reductions in near-term (135 days of gestation; dGA) fetal and placental size, and altered fetal liver gene expression, resulting from CSH deficiency. We sought to examine the impact of CSH deficiency on fetal and placental size earlier in gestation (50 dGA), and to examine placental gene expression at 50 and 135 dGA. At 50 dGA, CSH-deficient pregnancies exhibited a 41% reduction (P≤0.05) in uterine vein concentrations of CSH, and significant (P≤0.05) reductions (≈21%) in both fetal body and liver weights. Placentae harvested at 50 and 135 dGA, exhibited reductions in IGF1 and IGF2 mRNA concentrations, along with reductions in SLC2A1 and SLC2A3 mRNA. By contrast, mRNA concentrations for various members of the System A, System L and System y+ amino acid transporter families were not significantly impacted. The IUGR observed at the end of the first-third of gestation, indicates that the near-term IUGR reported previously, began early in gestation, and may have in part resulted from deficits in the paracrine action of CSH within the placenta. These results provide further compelling evidence for the importance of CSH in the progression and outcome of pregnancy.

Keywords: Chorionic Somatomammotropin, Placental Lactogen, Sheep, Placenta, Lentivirus, RNA Interference, SLC2A1, SLC2A3

Introduction

Various complications during pregnancy can impact the health and survival of a fetus, among the most significant of these being intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). IUGR affects upwards to 8% of human pregnancies, and occurs when a fetus fails to grow to its full potential (Gagnon 2003). IUGR is a leading cause of perinatal mortality and is associated with an increased risk of adult-onset disease such as hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, and stroke (Barker & Osmond 1986, Barker et al. 1989, 1990, 1993a & b, Gagnon 2003). Functional placental insufficiency accounts for at least half of IUGR cases when the fetus is normally formed (Ghidini 1996). As the placenta mediates the exchange of nutrients and oxygen from the mother to the fetus (Barry & Anthony 2008), placental insufficiency results in relative fetal undernutrition, impairing normal growth and development. Furthermore, the placenta is itself a highly metabolic organ, metabolizing a majority of the glucose and oxygen delivered to it (Meschia et al. 1980, Bell et al. 1986), as well as producing an array of hormones and growth factors that impact maternal and fetal metabolism and promote fetal growth and development. Of these, chorionic somatomammotropin (CSH, a.k.a. placental lactogen) has long been hypothesized to impact metabolism in both the mother and fetus (Handwerger 1991, Handwerger & Freemark 2000).

CSH is a member of the growth hormone/prolactin gene family that is synthesized and secreted by syncytiotrophoblasts in the human placenta and binucleate cells in the sheep placenta (Gootwine 2004). Both human and sheep IUGR pregnancies are associated with reduced concentrations of CSH in maternal circulation (Spellacy 1976, Lea et al. 2008), and CSH is among the most abundantly produced placental proteins, continuously secreted into maternal and fetal circulation throughout pregnancy (Walker et al. 1991, Wooding & Burton 2008). However, until recently (Baker et al. 2016) there was no direct evidence as to whether CSH-deficiency had a causative, correlative, or dependent relationship with IUGR. Baker et al. (2016) reported the generation of CSH-deficient sheep pregnancies, generated by lentiviral-mediated RNA interference in vivo, which resulted in significant IUGR near term.

At 135 days of gestation (dGA), CSH-deficient pregnancies (Baker et al. 2016) exhibited 52% and 32% reductions in placental and fetal weights, respectively, as a result of 50% and 38% reductions in CSH mRNA and protein. The observed growth restriction was associated with significant reductions in umbilical concentrations of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), as well as fetal hepatic concentrations of IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 mRNA, supporting hypotheses about CSH actions within the fetus (Handwerger 1991, Handwerger & Freemark 2000). However, maternal concentrations of insulin and IGF1, as well as maternal hepatic concentrations of IGF1, IGF2 and IGFBP mRNA, were not impacted by CSH deficiency, contrary to what had been previously hypothesized about the actions of CSH on maternal physiology (Handwerger 1991, Handwerger & Freemark 2000). To determine whether CSH deficiency impacted placental and fetal growth prior to late-gestation, we generated additional pregnancies, which were harvested at the end of the first-third of gestation (50 dGA), and utilized the resulting tissue, as well as tissue harvested at 135 dGA (Baker et al. 2016), to investigate the impact of CSH deficiency on placental expression of the IGFs, glucose and amino acid transporters. It was our hypothesis that CSH deficiency impacts placental growth during early- to mid-gestation, setting the stage for fetal growth restriction during late-gestation.

Materials and Methods

All procedures conducted with animals and lentivirus were approved by the Colorado State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Protocol 14-5257A) and the Institutional Biosafety Committee (Protocols 11-034B and 13-043B), respectively.

Lentivirus generation

Generation of hLL3.7 tg6, which expresses an shRNA targeting CSH mRNA was previously described (Baker et al. 2016). The scrambled control sequence used by Baker et al. (2016) was cloned into LL3.7, using the same procedures as described for hLL3.7 tg6, thereby generating hLL3.7 NTS (non-targeting sequence/scrambled control). The shRNA sequences for both hLL3.7 tg6 and hLL3.7 NTS are presented in Table 1. Generation and titering of virus harboring the hLL3.7 tg6 and hLL3.7 NTS constructs followed the procedures extensively described by Baker et al. (2016).

Table 1.

Scrambled control and CSH-targeting shRNA sequences.

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| NTS shRNA sense | GAGTTAAAGGTTCGGCACGAATTCAAGAGATTCGTGCCGAACCTTTAACTC |

| tg6 shRNA sense | AAGGCCAAAGTACTTGTAGACTTCAAGAGAGTCTACAAGTACTTTGGCCTT |

Blastocyst collection and transfer

Individual hatched and fully expanded blastocysts, harvested from donor ewes 9 days after breeding, were infected with 100,000 transducing units of either hLL3.7 NTS or hLL3.7 tg6, as previously described (Baker et al. 2016). Following ≈5 hours of incubation with the virus, the blastocysts were thoroughly washed in HCDM-2 media (Baker et al. 2016) and a single blastocyst was surgically transferred to each synchronized recipient ewe. Recipient ewes were monitored for return to standing estrus daily. The recipient ewes were group housed and fed to meet, or slightly exceed, their gestational nutrient requirements.

Tissue collection

At 50 dGA, 8 hLL3.7 NTS pregnancies (Control) and 6 hLL3.7 tg6 pregnancies (CSH-deficient) were harvested at terminal surgery as previously described (Baker et al. 2016). Uterine vein blood was harvested prior to euthanization of the ewe and fetus (90 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital; intravenous infusion of the uterine vein and umbilical vein), and the resulting serum was stored at −80°C, before being assayed for CSH concentrations (Kappes et al. 1992, Lea et al. 2008, Baker et al. 2016). Fetal body weight and crown-rump length were recorded for each fetus. Fetal livers were harvested, recorded for weight, and stored in 50-ml conical tubes snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. After hysterectomies were performed, all placentomes (combination of maternal caruncle and fetal cotyledon) were excised, washed in PBS, and recorded for placental weight and total placentome number. The fetal cotyledons were separated from the maternal caruncles, and the fetal cotyledons were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, before being pulverized using a mortar and pestle. Pulverized tissue was kept frozen at −80°C for later use. Harvest of placental tissue (fetal cotyledon) from Control and CSH-deficient pregnancies at 135 dGA, as well as the characteristics of those pregnancies, has been previously reported (Baker et al. 2016).

RNA isolation

Total cellular RNA was isolated from 50 dGA fetal placenta and liver, as well as from 135 dGA fetal placenta (Baker et al. 2016) using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The BioTek Synergy 2 Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT) was used to quantify RNA concentration, and measure RNA purity using the 260/280 absorbance ratio. Samples were stored at −80°C until use.

cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR

cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total cellular RNA using iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All cDNA samples were treated with 5 units of RNase H (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 37°C for 20 minutes. To control for variance in efficiency of the reverse transcription reaction, cDNA was quantified using the Quant-iT OliGreen ssDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An equal mass of cDNA (20 ng) was used for each sample in the quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) reaction.

qPCR was performed using the LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) and protocol previously described (Baker et al. 2016). Forward and reverse primers for qPCR were designed using Oligo software (Molecular Biology Insights, Cascade, CO) to amplify an intron-spanning product. Primer sequences and amplicon sizes are summarized in Table 2. A PCR product for each gene was generated using cDNA from 135 dGA fetal placenta as a template and cloned into the StrataClone vector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Amplification of the correct cDNA was verified by sequencing each PCR product (Colorado State University Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility). Standard-curves were generated for each mRNA from 1×102 to 1×10−5 pg using the PCR products amplified from the sequenced plasmids, and were used to measure amplification efficiency. Starting quantities (pg) were normalized by dividing the starting quantity of the mRNA of interest by the starting mRNA quantity (pg) of ovine ribosomal S15 (RPS15). All primers were annealed at 60°C. The starting quantity (pg) of RPS15 mRNA was not impacted (P≥0.25) by CSH deficiency in either 50 or 135 dGA tissues.

Table 2.

Primers and product sizes for cDNA used in qPCR.

| cDNA | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Product, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1 | TCG CAT CTC TTC TAT CTG GCC CTG T | ACA GTA CAT CTC CAG CCT CCT CAG A | 240 |

| IGF2 | GAC CGC GGC TTC TAC TTC AG | AAG AAC TTG CCC ACG GGG TAT | 203 |

| IGFBP1 | TGA TGA CCG AGT CCA GTG AG | GTC CAG CGA AGT CTC ACA C | 248 |

| IGFBP2 | CAA TGG CGA GGA GCA CTC TG | TGG GGA TGT GTA GGG AAT AG | 330 |

| IGFBP3 | CTC AGA GCA CAG ACA CCC A | GGC ATA TTT GAG CTC CAC | 336 |

| RPS15 | ATC ATT CTG CCC GAG ATG GTG | TGC TTG ACG GGC TTG TAG GTG | 134 |

| SLC2A1 | GAC AGG GAG GAG CAA GCC AAA | TAG GGT GAA GCC AGG GAT GTG | 380 |

| SLC2A3 | CTC TAC TGC TGG GCT TCA CC | ACT TGC TTC TCC TGC GAC AT | 211 |

| SLC38A1 | CCC GAA GAC GAT AAC ATT AGC AA | CTC CCA GCT TTT CAT AAA CCA | 382 |

| SLC38A2 | CTT GCT GCC CTC TTT GGA T | CAA CAC AGC CAA ACG GAC AA | 120 |

| SLC38A4 | CTA TTC GCA CAT CAG TGA C | TGA AAA TGA TGC CAA CCA C | 279 |

| SLC7A5 | GCT CGG CTT CAT CCA GAT C | AGG CAA AGA GGC CGC TGT A | 122 |

| SLC7A8 | TAT TGC TCC TCA CAT GGG TCA | GAC AAG CTC CTC AGT CAC GTA | 272 |

| SLC7A1 | CTT ACG GTA TCA GCC CGA GCA | GAA AGA CTG CTG CCC ACA ACT CCC | 320 |

Western immunoblotting

Cellular protein from 50 and 135 dGA fetal placenta (cotyledon) tissue was assessed using Western immunoblot analysis. To isolate total cellular protein, cotyledon tissue (100 mg) was lysed in 500 μl of Western lysis buffer (0.48 M Tris, pH 7.4; 10 mM EGTA, pH 8.6; 10 mM EDTA, pH 8; 0.1 mM PMSF; 0.1 mM AEBSF; 0.0015 mM pepstatin A; 0.0014 mM E-64; 0.004 mM bestatin; 0.002 mM leupeptin; and 0.00008 mM aprotinin) and sonicated on ice. 10 to 50 μg of protein from each sample was electrophoresed through a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and transferred to a 0.45-μm pore nitrocellulose membrane. To visualize CSH (1:25,000 dilution, α-oPL-S4; Kappes et al. 1992), SLC2A1 (1:2,000 dilution, product no. 07-1401; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA), and SLC2A3 (1:500 dilution, product no. ab125465; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) an anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (1:5,000 dilution, product no. sc-2004; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) was used. As a loading control and housekeeping protein to normalize CSH, SLC2A1, and SLC2A3, a polyclonal antibody to β-actin (ACTB, 1:2,500 dilution, product no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) bound by a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000, product no. sc-2005; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used. Membranes were developed using an ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent chemiluminescent kit (Amersham, Pittsburgh, PA) and imaged using the ChemiDoc XRS+ chemiluminescence system (BioRad). Densitometry calculations were performed using Image Lab Software (Bio-Rad). Technical error between membranes was corrected by including a common sample in each Western immunoblot. Densitometry measurements were adjusted based on the average densitometry measurement of the common sample and normalized to ACTB.

Statistical analyses

All data were subjected to analysis of variance using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and the PROC Mixed procedure, with treatment and fetal sex as dependent variables and the treatment × fetal sex interaction. There was not a significant fetal sex effect (50 dGA), or a significant treatment by fetal sex interaction, subsequently data from Control and CSH-deficient pregnancies were compared by Student’s t-test within a gestational age. Statistical significance was set at P≤0.05, and statistical tendency was set at P≤0.10. Data are reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

Day 50 fetal and placental measurements

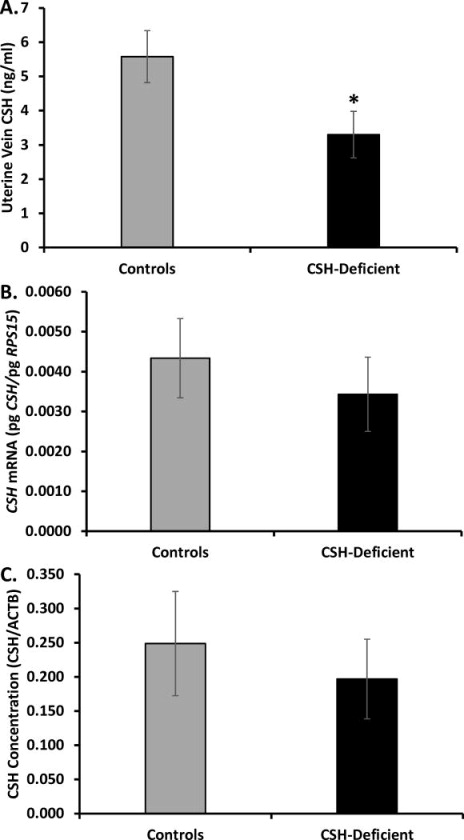

Following viral infection and single blastocyst transfer, 8 Control (50% males) and 6 CSH-deficient (33% males) pregnancies were harvested at 50 dGA. Fetal body weight (FBW), crown-rump length (CRL), fetal liver weight (FLW) and placental weight (PW) are presented in Table 3. As evidenced in Table 3, both FBW and FLW were significantly (P≤0.01) reduced in the 50 dGA CSH-deficient pregnancies, whereas CRL and PW only tended (P≤0.10) to be impacted. Placental efficiency (FBW/PW) was not impacted (P≥0.10) by CSH deficiency (Table 3). Uterine vein CSH concentrations were reduced (P≤0.05) ≈41% in CSH-deficient pregnancies (Figure 1), as compared to Control pregnancies. CSH mRNA and protein concentrations within the placenta were both reduced ≈21% in CSH-deficient pregnancies, but these differences were not statistically significant (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Fetal and placental measurements for 50 dGA pregnancies.

| 50 dGA | Controls | CSH-Deficient | p value | % difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Weight (g) | 17.17±0.39 | 13.65±0.61 | 0.01 | 20.5 |

| CRL (cm) | 9.5±0.11 | 8.5±0.20 | 0.10 | 10.4 |

| Fetal Liver (g) | 1.32±0.06 | 1.04±0.08 | 0.01 | 20.9 |

| Placenta Weight (g) | 105.5±4.42 | 88.1±10.31 | 0.11 | 16.5 |

| Placental Efficiency (g/g) | 0.165±0.008 | 0.165±0.02 | 0.98 | 0.32 |

Figure 1.

(A) Uterine vein CSH concentration at 50 dGA. (B) Placental CSH mRNA concentrations at 50 dGA. (C) Placental CSH concentrations at 50 dGA. *P≤0.05 when CSH-deficient pregnancies are compared with controls.

Insulin-like growth factor and insulin-like growth factor binding proteins

At 50 dGA, there were no statistical differences in mRNA concentrations for either IGF1, IGF2, or any of the three IGFBPs (Table 4) within the fetal liver. Within the placenta, IGF1 mRNA concentrations were reduced at 50 (P=0.12) and 135 (P≤0.05) dGA (Table 5), whereas IGF2 mRNA concentration was reduced (P≤0.05) only at 135 dGA. Placental expression of IGFBP1 was undetectable at 50 dGA (Table 5), whereas at 135 dGA there was a tendancy (P=0.11) for increased IGFBP1 mRNA concentration in CSH-deficient pregnancies relative to Control pregnancies. By contrast, IGFBP2 mRNA concentration was reduced (P≤0.05) at 50 dGA in CSH-deficient pregnancies, but there was no treatment effect at 135 dGA (Table 5). Placental IGFBP3 mRNA concentration was not statistically impacted by treatment at either 50 or 135 dGA.

Table 4.

50 dGA fetal liver insulin-like growth factor mRNA concentrations.

| Controls | oCSH-Deficient | p value | % difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1, pg/pg | 0.0015±0.00015 | 0.0013±0.00013 | 0.24 | 17.0 |

| IGF2, pg/pg | 1.05±0.12 | 0.74±0.13 | 0.14 | 29.3 |

| IGFBP1, pg/pg | 0.68±0.12 | 0.73±0.09 | 0.77 | 6.9 |

| IGFBP2, pg/pg | 0.052±0.010 | 0.043±0.011 | 0.53 | 18.1 |

| IGFBP3, pg/pg | 0.30±0.05 | 0.28±0.05 | 0.85 | 4.7 |

Table 5.

50 and 135 dGA placenta insulin-like growth factor mRNA concentrations.

| 50 dGA | Controls | CSH-Deficient | p value | % difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IGF1, pg/pg | 0.000081±0.000028 | 0.000024±0.000008 | 0.12 | 69.6 |

| IGF2, pg/pg | 0.082±0.012 | 0.064±0.009 | 0.28 | 21.4 |

| IGFBP1, pg/pg | 0 | 0 | ||

| IGFBP2, pg/pg | 0.0022±0.00060 | 0.0006±0.00025 | 0.04 | 73.1 |

| IGFBP3, pg/pg | 0.026±0.006 | 0.019±0.004 | 0.41 | 27.3 |

|

| ||||

| 135 dGA | Controls | CSH-Deficient | p value | % difference |

|

| ||||

| IGF1, pg/pg | 0.003±0.0009 | 0.001±0.0002 | 0.03 | 65.7 |

| IGF2, pg/pg | 0.36±0.07 | 0.17±0.05 | 0.04 | 53.3 |

| IGFBP1, pg/pg | 0.00021±0.00007 | 0.00057±0.00019 | 0.11 | 62.5 |

| IGFBP2, pg/pg | 0.0024±0.0006 | 0.0029±0.0010 | 0.69 | 16.8 |

| IGFBP3, pg/pg | 0.047±0.008 | 0.045±0.007 | 0.88 | 3.4 |

Nutrient transporters

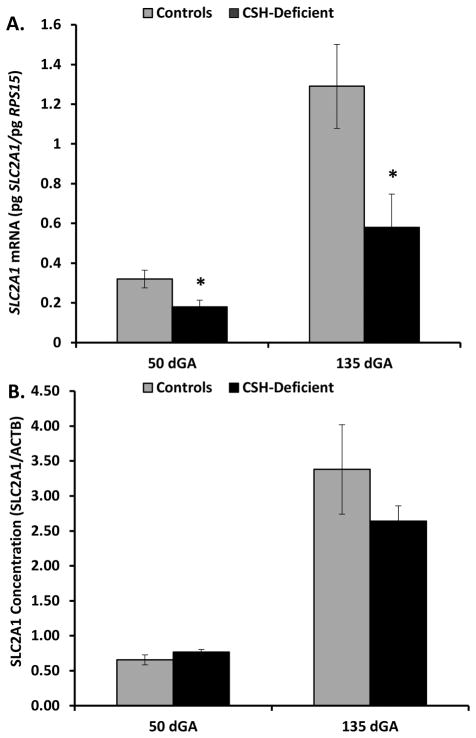

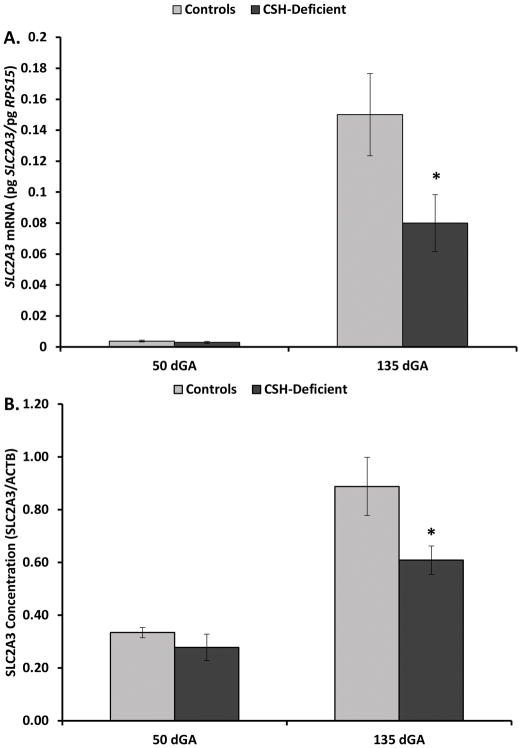

As evidenced in Figure 2, SLC2A1 mRNA concentration was reduced (P≤0.05) in CSH-deficient placenta at 50 and 135 dGA, relative to Controls. However, placental SLC2A1 concentration (Figure 2) was not statistically reduced at either 50 or 135 dGA. By contrast SLC2A3 mRNA (Figure 3) was reduced only 24% (P≥0.10) at 50 dGA, but was significantly less (49%; P≤0.05) in CSH-deficient placenta at 135 dGA. Placental SLC2A3 concentration (Figure 3) mirrored the changes in mRNA concentrations, with a nonsignificant (P≥0.10) 17% reduction at 50 dGA, and a significant 32% reduction (P≤0.05) at 135 dGA in CSH-deficient pregnancies. There was no effect of CSH deficiency at 50 dGA on SLC2A8 mRNA concentration (Figure 4), but SLC2A8 mRNA was increased (P≤0.05) in CSH-deficient placenta at 135 dGA (Figure 4). We were unable to identify an antiserum that allowed the specific assessment of sheep SLC2A8 by Western immunoblot analysis.

Figure 2.

(A) Effect of CSH deficiency on SLC2A1 mRNA concentrations in the placenta at 50 and 135 dGA. (B) Effect of CSH deficiency on SLC2A1 concentrations in the placenta at 50 and 135 dGA. *P≤0.05 when CSH-deficient pregnancies are compared with controls, within a gestational age.

Figure 3.

(A) Effect of CSH deficiency on SLC2A3 mRNA concentrations in the placenta at 50 and 135 dGA. (B) Effect of CSH deficiency on SLC2A3 concentrations in the placenta at 50 and 135 dGA. *P≤0.05 when CSH-deficient pregnancies are compared with controls, within a gestational age.

Figure 4.

Effect of CSH deficiency on SLC2A8 mRNA concentrations in the placenta at 50 and 135 dGA. *P≤0.05 when CSH-deficient pregnancies are compared with controls, within a gestational age.

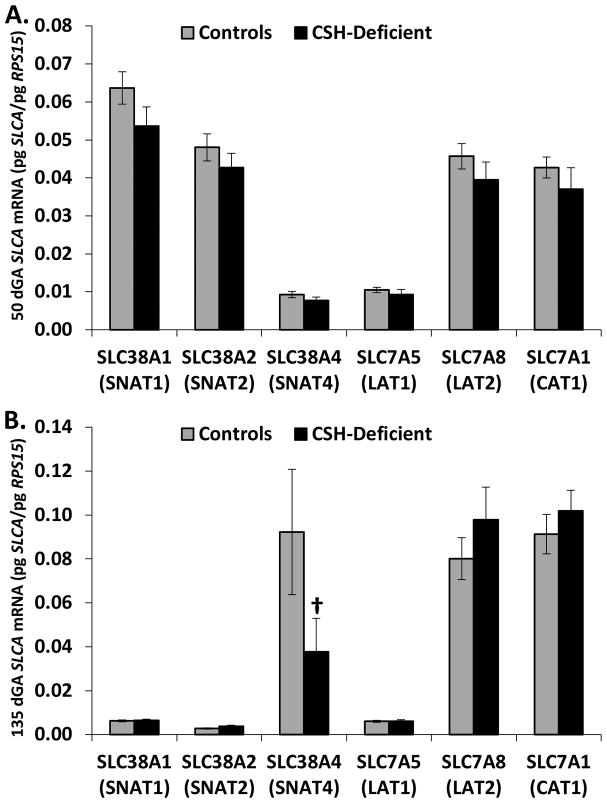

The mRNA concentration of System A (SLC38A1, SLC38A2 and SLC38A4), System L (SLC7A5 and SLC7A8) and System y+ (SLC7A1) amino acid transporter families was assessed in our Control and CSH-deficient pregnancies harvested at 50 and 135 dGA. As evidence in Figure 5, there were no significant changes in the mRNA concentration of any of these amino acid transporters at 50 dGA, as a result of CSH deficiency. At 135 dGA (Figure 5), the only transporter that appeared to be impacted by CSH deficiency was SLC38A4 (SNAT4), which tended (P≤0.10) to be reduced.

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of CSH deficiency on amino acid transporter mRNA concentrations in the placenta at 50 dGA. (B) Effect of CSH deficiency on amino acid transporter mRNA concentrations in the placenta at 135 dGA. †P≤0.10 when CSH-deficient pregnancies are compared with controls, within a gestational age.

Discussion

Using lentiviral-mediated RNA interference, we recently reported the generation of CSH-deficient pregnancies in sheep (Baker et al. 2016). Near-term (135 dGA), CSH-deficient pregnancies (Baker et al. 2016) were characterized by significant fetal (32% reduction) and placental (52% reduction) growth restriction, associated with reductions in placental CSH mRNA (50%) and protein (38%). These results provided support for the long-held hypotheses that CSH promotes fetal growth (Handwerger 1991, Handwerger & Freemark 2000). The purpose of the current study was to determine whether CSH deficiency manifested changes in placental function and fetal growth at the end of the first-third of gestation (50 dGA), a time-point when the placenta is fully established and continuing to grow.

At the end of the first-third of gestation we observed significant (P≤0.01) reductions in fetal weight and fetal liver weights, suggesting that the growth restriction observed near-term (Baker et al. 2016) in CSH-deficient pregnancies started during early gestation. Although placental weight only tended to be smaller at 50 dGA (Table 3), the ratio of fetal weight to placental weight (i.e., placental efficiency) was equivalent between Control and CSH-deficient pregnancies. This would suggest that placental size/function was the driving force behind the fetal growth restriction observed at 50 dGA.

In contrast to what we observed (Baker et al. 2016) near-term, there was a significant (P≤0.05) reduction in uterine vein concentrations of CSH. At 50 dGA, due to the size of the fetus and amount of fetal blood, we could not harvest sufficient umbilical blood to assess CSH concentrations, as we did at 135 dGA (Baker et al. 2016). As discussed in Baker et al. (2016), blood concentrations of CSH become quite variable towards the end of gestation (Taylor et al. 1980, Butler et al. 1987, Bauer et al. 1995), and surgery elevates both maternal and fetal concentrations of CSH for up to 5 days (Taylor et al. 1980). Similar studies of CSH variability over time, during early to mid-gestation, have not been reported. However, simply comparing the overall (both Control and CSH-deficient) coefficients of variation (COV) for the uterine vein values obtained at 50 dGA (≈16%) versus 135 dGA (≈1858%) infers that CSH secretion into maternal circulation is not nearly as variable during early to mid-gestation as it is near-term. Maternal and fetal vascular cannulation, and harvest of serial samples obtained under non-stressed/non-anesthetized conditions, along with blood flow measurements, will be necessary to accurately assess the impact of CSH RNA interference on maternal and fetal concentrations of CSH. To our surprise, within the CSH-deficient placenta at 50 dGA, we could not demonstrate a statistically significant change in CSH mRNA and protein, as we had at 135 dGA. Unfortunately we cannot fully explain discrepancies between these two studies as a result of in vivo RNA interference on placental CSH mRNA and protein. This could result from day to day variability in shRNA expression and function, but to our knowledge there is no approach to directly address this potential variability in vivo.

In contrast to the robust reduction in fetal liver mRNA concentrations for IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 observed at 135 dGA (Baker et al. 2016), at 50 dGA neither IGF1 nor IGF2 mRNA concentration were significantly changed, nor were fetal liver mRNA concentrations for all three IGFBPs impacted by CSH deficiency. Due to the major impact of CSH deficiency on placental size observed at 135 dGA (Baker et al. 2016), we reasoned that at least part of CSH’s impact may result from paracrine actions within the placenta. Accordingly, we examined the mRNA concentrations of IGF1, IGF2, IGFBP1, IGFBP2 and IGFBP3 in the placenta harvested at both 50 and 135 dGA (Baker et al. 2016). At 50 dGA, placental IGF1 tended (Table 5) to be reduced, and IGFBP2 was significantly lower, whereas IGF2, IGFBP1 and IGFBP3 were not impacted. However, near-term (135 dGA) placental concentrations of IGF1 and IGF2 mRNA were both significantly reduced, as they were in the near-term fetal liver (Baker et al. 2016). In contrast to what was observed in the near-term fetal liver (Baker et al. 2016), neither IGFBP2 nor IGFBP3 mRNA concentration was impacted by placental CSH deficiency at 135 dGA. While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from these samples, the disparity in expression of the various IGF axis components between the placenta and fetal liver, and between the two gestational ages examined, may result from both direct effects (i.e., directly within the placenta or fetus) and indirect effects (i.e., placental mediated effects on the fetus) of CSH.

Due to the impact of CSH deficiency on placental IGF expression, and evidence that IGF can impact the expression of placental nutrient transporters (Wali et al. 2012, Jones et al. 2013,2014, Baumann et al. 2014), we turned our attention to the expression of glucose and amino acid transporters within CSH-deficient placentae. Fitting with the hypothesis that CSH drives placental IGF1 expression and IGF1 in turn enhances SLC2A1 expression (Baumann et al. 2014), we observed diminished (P≤0.05) expression of SLC2A1 mRNA at both 50 dGA and 135 dGA, whereas SLC2A3 mRNA was significantly reduced (P≤0.05) only at 135 dGA. In contrast to what was observed with the reductions in SLC2A1 mRNA, Western blot analysis of fetal placental homogenates revealed no significant change in SLC2A1 at either 50 or 135 dGA. Janzen et al. (2013) reported a significant reduction in SLC2A1 mRNA within the basal plate region of human IUGR placenta, similar to what we observed in this study, with no change in the concentration of SLC2A1 protein. It is possible that SLC2A1 is so highly expressed in the placenta that there is a functional “reserve” of SLC2A1 mRNA, making SLC2A1 less susceptible to “outside” influences.

In contrast to SLC2A1, there was a similar magnitude of change at both 50 and 135 dGA for both SLC2A3 mRNA and protein. Similar to the human, SLC2A1 is much more abundant than SLC2A3 in the sheep placenta, but in sheep, SLC2A1 is located on the trophoblast basolateral surface, whereas SLC2A3 is located solely on the maternal-facing apical microvillous surface (Wooding et al. 2005). While the expression of SLC2A3 increases significantly during the latter-half of gestation (Ehrhardt & Bell 1997), due to its location (Wooding et al. 2005), affinity and glucose transport capacity (Simpson et al. 2008), similar to the human (Brown et al. 2011), SLC2A3 may play a significant role during the first-half of gestation as well, by mediating the uptake of glucose into the trophoblast. Due to the greater impact of CSH-deficiency on SLC2A3 protein, lack of SLC2A3 may have been a driving force behind the growth restriction observed.

At 50 dGA there was no difference in SLC2A8 mRNA, but at 135 dGA, there was a ≈76% increase (P≤0.05) in SLC2A8 mRNA concentration. It has been reported that SLC2A8 placental mRNA and protein expression is decreased in the hyperthermic-model of sheep IUGR (Limesand et al. 2004). However, Wooding et al. (2005) was unable to identify significant membrane localization of SLC2A8 in any of the ruminant placenta examined. SLC2A8 is a class III glucose transporter (SLC2A1 and SLC2A3 are class I transporters; Joost et al. 2002), which is primarily localized to endosomes, lysosomes and endoplasmic reticulum membranes (Schmidt et al. 2009), and is thought to catalyze hexose transport across intracellular membranes. SLC2A8 might be up-regulated in response to deficiencies in SLC2A1 or SLC2A3. If its role is as an intracellular transporter (Schmidt et al. 2009), its up-regulation may infer a mechanism by which the placenta preserves its metabolic function, which would fit with the reductions in mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP generation in sperm of Slc2A8−/− mice (Gawlik et al. 2008). While our data on SLC2A8 are intriguing, since there is no evidence for its role in glucose transport to the fetus, its role in the resulting IUGR observed in CSH-deficient pregnancies at 50 and 135 dGA is not readily apparent.

In contrast to the glucose transporters, we did not observe significant changes in mRNA concentrations for SLC38A1, SLC38A2, SLC38A4, SLC7A1, SLC7A5 or SLC7A8, except for a trend (P≤0.10) for reduced SLC38A4 (SNAT4) at 135 dGA. Placental transfer of amino acids, especially essential amino acids, is reduced in human and sheep IUGR pregnancies (Marconi et al. 1999, deVrijer et al. 2004, Reganult et al. 2005). However, amino acid transporter mRNA and protein concentration is not a perfect surrogate for transporter activity in IUGR pregnancies (Mando et al. 2013, Chen et al. 2015, Dunlap et al. 2015, Panthan et al. 2016). Thorough in vivo assessment of placental uptake, net utilization, and transfer to the fetus, is required before any changes in placental nutrient transporter mRNA or protein concentrations can be interpreted completely.

Collectively, our current results combined with the work of Baker et al. (2016), provide compelling evidence for the importance of CSH in the progression and outcome of pregnancy. Our initial study (Baker et al. 2016) supported the long-held hypotheses (Handwerger 1991, Handwerger & Freemark 2000) that CSH promoted fetal growth by impacting fetal concentrations of IGF1 and insulin. Our current results expand the possible impact of CSH to actions within the placenta itself, including the expression of IGF1, IGFBP2 and glucose transporters. These paracrine actions within the placenta may have been responsible for the reduction in fetal growth that occurred during early gestation (50 dGA), but may have also set the stage for functional placental insufficiency during late gestation (135 dGA). Unfortunately, with both of our studies, it was not feasible to chronically catheterize the pregnancies, allowing steady-state investigations under non-stressed/non-anesthetized conditions that will be required to determine direct effects of CSH within the placenta versus actions directly within the fetus. Regardless of these shortcomings, our results highlight the utility of in vivo lentiviral-mediated RNA interference to study the function of genes expressed by the placenta of large mammals. More importantly, they provide compelling evidence that CSH plays a critical role in the progression of pregnancy and lay the groundwork for future studies that can delineate the exact mechanisms by which CSH promotes fetal growth.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2012-67015-30215 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA), USDA NIFA W3112 Multistate Project, and NIH grant HD 090312.

The authors wish to thank Vince Abushaban, Richard Brandes, Zella Brink, Gregory Harding, Jay Kailey, Erin McWhorter and Rachel West for animal care and additional technical support.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

References

- Baker CM, Goetzmann LN, Cantlon JD, Jeckel KM, Winger QA, Anthony RV. The development of ovine chorionic somatomammotropin hormone deficent pregnancies. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2016;310:R837–R846. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00311.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C. Infant mortality, childhood nutrition, and ischaemic heart disease in England and Wales. Lancet. 1986;327:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Bull AR, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ. Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. British Medical Journal. 1990;301:259–262. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6746.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Osmond C, Golding J, Kuh D, Wadsworth ME. Growth in utero, blood pressure in childhood and adult life, and mortality from cardiovascular disease. British Medical Journal. 1989;298:564–567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6673.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D, Godfrey K, Gluckman P, Harding J, Owens J, Robinson J. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet. 1993a;341:938–941. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91224-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ, Hales CN, Fall CH, Osmond C, Phipps K, Clark PM. Type 2 (non- insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia (syndrome X): relation to reduced fetal growth. Diabetologia. 1993b;36:62–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00399095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry JS, Anthony RV. The pregnant sheep as a model for human pregnancy. Theriogenology. 2008;69:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer MK, Breier BH, Harding JE, Veldhuis JD, Gluckman P. The fetal somatotropic axis during long term maternal undernutrition in sheep: evidence for nutritional regulation in utero. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1250–1257. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.3.7867579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MU, Schneider H, Malek A, Palta V, Surbek DV, Sager R, Zamudio S, Illsley NP. Regulation of human trophoblast GLUT1 glucose transporter by insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell AW, Kennaugh JM, Battaglia FC, Makowski EL, Meschia G. Metabolic and circulatory studies of fetal lamb at midgestation. American Journal of Physiolology - Endocrinolology & Metabolism. 1986;250:E538–E544. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1986.250.5.E538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown K, Heller DS, Zamudio S, Illsley NP. Glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) protein expression in human placenta across gestation. Placenta. 2011;32:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler WR, Huyler SE, Grandis AS, Handwerger S. Failure of fasting and changes in plasma metabolites to affect spontaneous fluctuations in plasma concentrations of ovine placental lactogen. Journal of Endocrinology. 1987;114:391–397. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1140391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YY, Rosario FJ, Shehab MA, Powell TL, Gupta MB, Jansson T. Increased ubiquitination and reduced plasma membrane trafficking of placental amino acid transporter SNAT-2 in human IUGR. Clinical Science (Lond) 2015;129:1131–1141. doi: 10.1042/CS20150511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vrijer B, Regnault TR, Wilkening RB, Meschia G, Battaglia FC. Placental uptake and transport of ACP, a neutral nonmetabolizable amino acid, in an ovine model of fetal growth restriction. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;287:E1114–E1124. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00259.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap KA, Brown JD, Keith AB, Satterfield MC. Factors controlling nutrient availability to the developing fetus in ruminants. Journal of Animal Science & Biotechnology. 2015;6:16. doi: 10.1186/s40104-015-0012-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt RA, Bell AW. Developmental increases in glucose transporter concentration in the sheep placenta. American Journal of Physiology - Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 1997;273:R1132–R1141. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1997.273.3.R1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon R. Placental insufficiency and its consequences. European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecolology Reproductive Biology. 2003;110:S99–S107. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(03)00179-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawlik V, Schmidt S, Scheepers A, Wennemuth G, Augustin R, Aumuller G, Moser M, Al-Hasani H, Kluge R, Joost HG, et al. Targeted disruption of Slc2a8 (GLUT8) reduces motility and mitochondrial potential of spermatozoa. Molecular Membrane Biology. 2008;25:224–235. doi: 10.1080/09687680701855405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghidini A. Idiopathic fetal growth restriction. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 1996;51:376–382. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199606000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootwine E. Placental hormones and fetal-placental development. Animal Reproduction Science. 2004;82–83:551–566. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerger S. Clinical counterpoint: the physiology of placental lactogen in human pregnancy. Endocrine Reviews. 1991;12:329–336. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-4-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerger S, Freemark M. The roles of placental growth hormone and placental lactogen in the regulation of human fetal growth and development. Journal of Pediatric Endocinology & Metabolism. 2000;13:343–356. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen C, Lei MYY, Cho J, Sullivan P, Shin B-C, Devaskar SU. Placental glucose transporter 3 (GLUT3) is up-regulated in human pregnancies complicated by late-onset intrauterine growth restriction. Placenta. 2013;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joost H-G, Bell GI, Best JD, Birnbaum MJ, Charrron MJ, Chen YT, Doege H, James DE, Lodish HF, Moley KH, et al. Nomenclature of the GLUT/SLC2A family of sugar/polyol transport facilitators. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2002;282:E974–E976. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00407.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HN, Crombleholme T, Habli M. Adenoviral-mediated placental gene transfer of IGF-1 corrects placental insufficiency via enhanced placental glucose transport mechanisms. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e74632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones H, Crombleholme T, Habli M. Regulation of amino acid transporters by adenoviral-mediated human insulin-like growth factor-1 in a mouse model of placental insufficiency in vivo and the human trophoblast line BeWo in vitro. Placenta. 2014;35:132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappes SM, Warren WC, Pratt SL, Liang R, Anthony RV. Quantification and cellular localization of ovine placental lactogen messenger ribonucleic acid expression during mid- and late-gestation. Endocrinology. 1992;131:2829–2838. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.6.1446621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lea RG, Wooding P, Stewart I, Hannah LT, Morton S, Wallace K, Aitken RP, Milne JS, Regnault TR, Anthony RV, et al. The expression of ovine placental lactogen, StAR and progesterone-associated steroidogenic enzymes in placentae of overnourished growing adolescent ewes. Reproduction. 2008;135:889–889. doi: 10.1530/REP-06-0294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand SW, Regnault TRH, Hay WW., Jr Characterization of glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) in the ovine placenta of normal and growth restricted fetuses. Placenta. 2004;25:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mando C, Tabano S, Pileri P, Colapietro P, Marino MA, Avagliano L, Doi P, Bulfamante G, Miozzo M, Cetin I. SNAT2 expression and regulation in human growth-restricted placentas. Pediatric Research. 2013;74:104–110. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marconi AM, Paolini CL, Stramare L, Cetin I, Fennessey PV, Pardi G, Battaglia FC. Steady state maternal-fetal leucine enrichments in normal and intrauterine growth-restricted pregnancies. Pediatric Research. 1999;46:114–119. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199907000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschia G, Battaglia FC, Hay WW, Jr, Sparks JW. Utilization of substrates by the ovine placenta in vivo. Federation Proceedings. 1980;39:245–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantham P, Rosario FJ, Weintraub ST, Nathanielsz PW, Powell TL, Li C, Jansson T. Down-regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction in maternal nutrient restricted baboons. Biology of Reproduction. 2016;95:1–9. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.116.141085. 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnault TR, Friedman JE, Wilkening RB, Anthony RV, Hay WW., Jr Fetoplacental transport and utilization of amino acids in IUGR--a review. Placenta. 2005;26(Suppl A):S52–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Joost HG, Schurmann A. GLUT8, the enigmatic intracellular hexose transporter. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2009;296:E614–E618. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.91019.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Dwyer D, Malide D, Moley KH, Travis A, Vannucci SJ. The facilitative glucose transporter GLUT3: 20 years of distinction. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008;295:E242–E253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90388.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spellacy WN, Buhi WC, Birk SA. Human placental lactogen and intrauterine growth restriction. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1976;47:446–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MJ, Jenkin G, Robinson JS, Thorburn GD, Friesen H, Chan JS. Concentrations of placental lactogen in chronically catheterized ewes and fetuses in late pregnancy. Journal of Endocrinology. 1980;85:27–34. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0850027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wali JA, de Boo HA, Derraik JGB, Phus HH, Oliver MH, Bloomfield FH, Harding JE. Weekly intra-amniotic IGF-1 treatment increases growth of growth-restricted ovine fetuses and up-regulated placental amino acid transporters. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e37899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker WH, Fitzpatrick SL, Barrera-Saldana HA, Resendez-Perez D, Saunders GF. The human placental lactogen genes: Structure, function, evolution and transcriptional regulation. Endocrine Reviews. 1991;12:316–328. doi: 10.1210/edrv-12-4-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooding F, Burton G. Comparative placentation: structures, functions and evolution. New York, NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wooding FBP, Fowden AL, Bell AW, Ehrhardt RA, Limesand SW, Hay WW., Jr Localisation of glucose transport in the ruminant placenta: Implication for sequential use of transporter isoforms. Placenta. 2005;26:626–640. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]