ABSTRACT

The innate immune response of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has been extensively studied and a variety of Toll-independent immune response pathways have been identified. Surprisingly little, however, is known about how pathogens activate the C. elegans immune response. Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium are closely related enterococcal species that exhibit significantly different levels of virulence in C. elegans infection models. Previous work has shown that activation of the C. elegans immune response by Pseudomonas aeruginosa involves P. aeruginosa-mediated host damage. Through ultrastructural imaging, we report that infection with either E. faecalis or E. faecium causes the worm intestine to become distended with proliferating bacteria in the absence of extensive morphological changes and apparent physical damage. Genetic analysis, whole-genome transcriptional profiling, and multiplexed gene expression analysis demonstrate that both enterococcal species, whether live or dead, induce a rapid and similar transcriptional defense response dependent upon previously described immune signaling pathways. The host response to E. faecium shows a stricter dependence upon stress response signaling pathways than the response to E. faecalis. Unexpectedly, we find that E. faecium is a C. elegans pathogen and that an active wild-type host defense response is required to keep an E. faecium infection at bay. These results provide new insights into the mechanisms underlying the C. elegans immune response to pathogen infection.

KEYWORDS: Caenorhabditis elegans, Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, host-pathogen interactions, innate immunity, invertebrate models of infection, pathogen-associated molecular patterns, stress response

Introduction

Innate immunity is an evolutionarily ancient defense system that provides the first line of defense against invading microbes and is found in all plant and metazoan life. Innate immunity in both plants and metazoans is mediated in part by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize invariant molecular structures shared by pathogens, called microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). Upon activation, PRRs trigger downstream signaling, which ultimately culminates in the expression of immune effectors that inhibit the infection. While much is known about the activation of immune signaling pathways via MAMPs in plants, insects, and vertebrates, little is known about whether the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans is able to perceive MAMPs. It is possible that C. elegans is blind to MAMPs, as it is a natural bacteriovore, and thus must be somewhat tolerized to invariant microbial molecules such as lipopolysaccharides, peptidoglycans, and flagellin. In one relevant study, similar immune responses were activated when C. elegans was fed either live or heat-killed Staphylococcus aureus, suggesting that that C. elegans might be able to perceive MAMPs [1]. However, the single Toll-Like Receptor in C. elegans (TOL-1) does not appear to be significantly involved in innate immune signaling in C. elegans, at least in intestinal epithelial cells where the primary immune response occurs [2, 3]. Thus, these results suggested that the host response to S. aureus is activated by MAMPs in a manner independent of Toll signaling [1], although TOL-1-mediated signaling in chemosensory neurons can affect pathogen avoidance behavior [4].

In addition to MAMP recognition, host recognition of pathogen-elicited damage is also thought to be a general mechanism by which the host innate immune response is activated in both plants and animals [5], even though the mechanisms by which pathogens mediate direct or indirect damage to their hosts are still poorly understood. In the case of C. elegans, infection by live Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but not heat-killed cells, activates an immune response, with the magnitude of the host response to P. aeruginosa infection correlating with the degree of virulence of the infecting strain [5]. Moreover, P. aeruginosa-mediated blocking of host protein synthesis appears to be sufficient to activate immunity [6–8]. More generally, there is mounting evidence that disruption of cellular homeostasis by a variety of external toxins or defects in the function of particular essential genes can lead to immune activation in C. elegans [9–11].

With these results in mind, we investigated the mechanism by which C. elegans recognizes infection by two enterococcal species, E. faecalis and E. faecium, which have distinct infection-related phenotypes. Previously, our laboratory demonstrated that whereas E. faecalis and E. faecium both accumulate in and cause distention of the intestine of C. elegans, only E. faecalis is able to form a persistent infection and kill C. elegans [12]. These observations suggested that C. elegans may be tolerant to an E. faecium infection, if the accumulation of E. faecium in the intestine reflects a pathogenic process, as opposed, for example, to a mechanical or structural impediment in clearing E. faecium cells from the intestine. In any case, the mechanisms by which these two enterococcal strains disrupt host physiology, the nature of the host response to these pathogens, and the defense pathways required for resistance to Enterococcus have been elucidated only to a limited extent.

In this study, through ultrastructural imaging, we observed that infection with either E. faecalis or E. faecium causes intestinal distention in the absence of obvious damage, although infection with E. faecalis impairs the C. elegans defecation rhythm. Using gene expression profiling, we identified a large overlap in the C. elegans genes activated or repressed by E. faecalis or E. faecium, many of which are regulated by immune signaling pathways. We show that expression of these genes can also be elicited by heat-killed Enterococcus, but not by other heat-killed bacteria, demonstrating that C. elegans may perceive enterococcal-encoded MAMPs. We also demonstrate that stress pathways are required for the regulation of a specific subset of host effectors following infection with E. faecium, but not E. faecalis. Finally, we find that E. faecium is capable of infecting and killing immunocompromised C. elegans mutants. Since large numbers of E. faecium cells accumulate in the intestine of wild-type C. elegans animals, these results suggest that wild-type worms employ immune-response pathways to establish tolerance to an E. faecium infection. These findings shed new light on the mechanisms underlying pathogen sensing in C. elegans.

Results

Both E. faecalis and E. faecium distend the C. elegans intestine in the absence of extensive host damage, but only E. faecalis causes a lethal infection

Confirming previous work [12], we found that E. faecalis strain MMH594 causes a lethal infection in wild-type C. elegans strain N2 in an established agar-based assay [13], whereas the enterococcal species E. faecium strain E007 does not (S1 Fig). Importantly, the lethality of E. faecalis is not solely a consequence of in utero hatching of eggs (“bagging”). Although the LT50 of C. elegans treated with cdc-25.1 RNAi to induce maternal sterility and subsequently fed E. faecalis is longer than wild-type worms fed E. faecalis, the LT50 of cdc-25.1 RNAi-treated worms fed E. faecalis was almost half that of cdc-25.1 RNAi-treated worms fed E. faecium (LT50 = 8 days and 18 days, respectively) (S1 Fig).

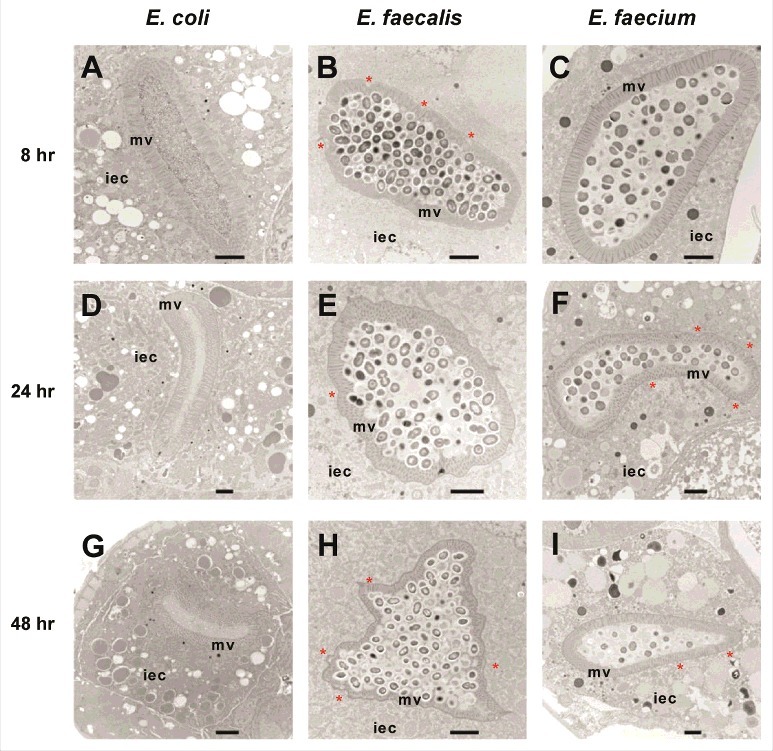

We used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to assess the ultrastructural cytopathology of E. faecalis- and E. faecium-infected worms. In control E. coli-fed C. elegans animals, nearly all bacterial cells in the intestinal lumen were macerated, and the intestinal microvilli appeared long, straight and anchored at their base into the terminal web (Figs. 1A, 1D, 1G). In contrast, E. faecalis- or E. faecium infected worms were found to have large numbers of bacterial cells packing and distending the intestine (Figs. 1B, 1E, 1H and Figs. 1C, 1F, 1I, respectively). Importantly, in both infections, many dividing bacterial cells were present in the intestine, as evidenced by the presence of septa, suggesting that they were actively proliferating. Interestingly, however, in the case of E. faecium, but not E. faecalis, many intestinal bacterial cells did not stain darkly, suggesting that their viability may have been negatively impacted by the host immune response. While the overall morphology of the intestinal cells in both E. faecalis- and E. faecium infected animals was not dramatically different from that observed in E. coli-fed worms, several features were clearly different in the Enterococcus-infected animals. First, some slight dehiscence of the terminal web from the luminal membrane was observed in the E. faecium-infected worms (Figs. 1C, 1F, 1I). Second, shortening of the intestinal microvilli could be seen in most E. faecalis-infected C. elegans (24 out of 32 sections) and some E. faecium-infected animals (7 out of 34 sections), which may be indicative of damage to the apical microvilli. Similar shortening of the microvilli was reported previously four days after infection with E. faecalis in a liquid-based killing assay [14]. Third, the basolateral surface of the intestinal cells of E. faecalis (Figs. 1E and 1H) and E. faecium (Figs. 1F and 1I) appeared undulatory in some TEM images (27 out of 32 E. faecalis-infected C. elegans sections; 10 out of 34 E. faecium-infected C. elegans sections), rather than exhibiting a smooth border as seen in worms fed E. coli. In contrast to live E. faecalis or live E. faecium, heat-killed enterococci did not accumulate in or distend the host intestine (data not shown). Furthermore, unlike infection by E. faecalis or E. faecium, previous TEM analysis showed that infection with P. aeruginosa or S. aureus caused severe intestinal damage [1]. P. aeruginosa infections were characterized by shortened microvilli, intracellular invasion from the intestine, and arrested autophagosomes, whereas S. aureus infections were characterized by severe effacement of the microvilli and lysis of intestinal epithelial cells [1]. All of the TEM images that we obtained are available upon request.

Figure 1.

Enterococci proliferate in and cause distention of the C. elegans intestine, but do not invade intracellularly or lyse intestinal cells. Transmission electron micrographs of transverse midbody sections of N2 C. elegans feeding on E. coli OP50 (A, D, G), E. faecalis MMH594 (B, E, H), or E. faecium E007 (C, F, I) at 8 hours (A-C), 24 hours (D-F), or 48 hours (G-I) post infection. Representative micrographs are shown. The microvilli (mv) and cytoplasm of an intestinal epithelial cell (iec) are marked. Sites of dehiscence of the terminal web from the luminal membrane are marked with an asterisk. Scale bar, 2 µm.

E. faecium is a C. elegans pathogen but wild-type worms are at least partially tolerant to an E. faecium infection

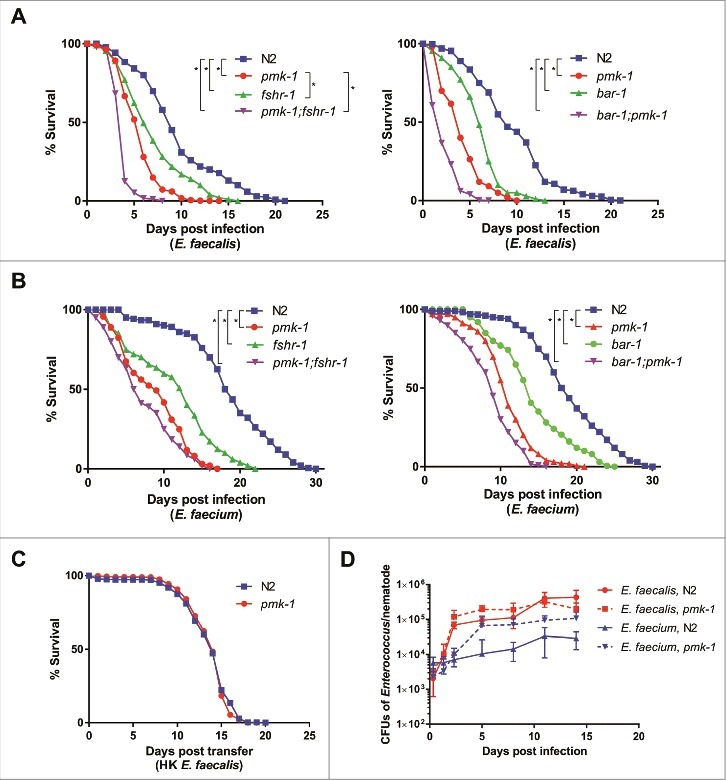

Previous work has shown that immune-deficient C. elegans exhibit enhanced susceptibility to E. faecalis [12]. We extended this work by assessing the survival of various characterized C. elegans immunity-related mutants feeding on either E. faecalis or E. faecium. In the case of E. faecalis infection, pmk-1, fshr-1, and bar-1 mutants were more susceptible than wild-type worms (Fig. 2A). PMK-1 encodes a p38 MAPK that is a highly-conserved component of metazoan immune response pathways [15, 16]. FSHR-1 encodes a leucine-rich repeat containing G-protein coupled receptor, homologous to the human follicle stimulating hormone receptor, and is important in the C. elegans defense response against P. aeruginosa [17]; recently, it has also been shown to regulate the host response to oxidative stress [18]. BAR-1 encodes a C. elegans homolog of β-catenin critical for conferring resistance to S. aureus [19]. Interestingly, pmk-1;fshr-1 and pmk-1; bar-1 double mutants were more susceptible to E. faecalis than the single mutants, suggesting that BAR-1 and FSHR-1 may each function in pathways independent from PMK-1 to mediate C. elegans immunity against E. faecalis infection (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

BAR-1, FSHR-1, and PMK-1 are required for defense against both E. faecalis and E. faecium. (A, B) Survival of wild-type N2, pmk-1(km25), fshr-1(ok778), and pmk-1(km25);fshr-1(ok778) C. elegans on E. faecalis (left) and wild-type N2, pmk-1(km25), bar-1(ga80), and pmk-1(km25);bar-1(ga80) animals (right) on E. faecalis (A) and E. faecium (B), sterilized with cdc-25.1 RNAi. (C) Survival of N2 and pmk-1(km25) worms sterilized with cdc-25.1 RNAi on heat-killed E. faecalis. Each graph shows the average of three plates for each strain, with each plate containing 30–40 worms. Results are representative of 3 independent assays. Statistical significance of differences between survival curves was calculated using Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis. Strains that showed a statistically significant difference from N2 are denoted with an asterisk and bracket. (D) Bacterial load of wild-type N2 and pmk-1 C. elegans after infection with E. faecalis or E. faecium. Time course of colony forming units in the intestines of wild-type N2 or pmk-1 deficient C. elegans, sterilized with cdc-25.1, and infected with either E. faecalis or E. faecium. Error bars represent the standard deviation. Results are representative of 2 independent assays; each condition of each experiment was performed in triplicate or quadruplicate.

Unexpectedly, although E. faecium does not kill wild-type C. elegans (S1 Fig), we observed the same pattern of susceptibility among the pmk-1, fshr-1, and bar-1 mutants after infection with E. faecium (Fig. 2B) as with E. faecalis (Fig. 2A). The pmk-1 mutant was also susceptible to a different E. faecium strain (BM4105SS) (S2 Fig). Importantly, wild-type N2 and mutant pmk-1 worms showed no difference in lifespan on heat-killed E. faecalis (Fig. 2C). Similarly, pmk-1 and fshr-1 showed no statistically significant difference in lifespan from wild-type N2 worms on the non-pathogenic food source heat-killed E. coli, although bar-1 and both pmk-1;fshr-1 and pmk-1;bar-1 exhibited some decrease in survival (S3 Fig). These data demonstrate that an active immune response is required for defense against E. faecium and that E. faecium appears to be a C. elegans pathogen.

The observation that E. faecium accumulates to large numbers in the C. elegans intestine (Fig. 1) and that immune pathways are required for the maintenance of host viability (Fig. 2) suggested that C. elegans is at least partially tolerant of an E. faecium infection. While it is not possible to vary microbial load in the C. elegans system, as C. elegans are infected by feeding ad libitum on bacterial lawns and often ingest bacteria on the plates that they have previously egested, we measured the load of viable bacterial cells in the C. elegans intestine of worms infected with E. faecalis or E. faecium as determined by their ability to form colonies when the worms were disrupted (see Methods). We found that N2 worms accumulated up to 4.3 × 105 E. faecalis CFUs in their intestines, whereas only a maximum of 3.1 × 104 CFUs accumulated in case of E. faecium (Fig. 2D). This observation correlates with the TEM results in Fig. 1, suggesting that E. faecium may be more susceptible than E. faecalis to the C. elegans immune response. A deficiency in PMK-1, however, led to an increase in the number of E. faecium CFUs recovered per worm (up to 1.1 × 105 cells/worm), but no significant increase in CFUs upon E. faecalis infection (up to 3.2 × 105 cells/worm). Thus, bacterial CFUs per worm correlate with host killing in the case of E. faecium, but not E. faecalis, even though deficiency of PMK-1 causes C. elegans to prematurely succumb to either infection. The reason that E. faecalis does not accumulate to higher titers in a pmk-1 mutant than in wild type worms may be that the intestine simply cannot accommodate any additional bacterial cells. Thus, it appears that wild-type C. elegans can tolerate a significant E. faecium infection, but that this level of tolerance requires PMK-1, and likely other components of the C. elegans immune response, which negatively impact E. faecium viability.

E. faecalis infection perturbs C. elegans defecation

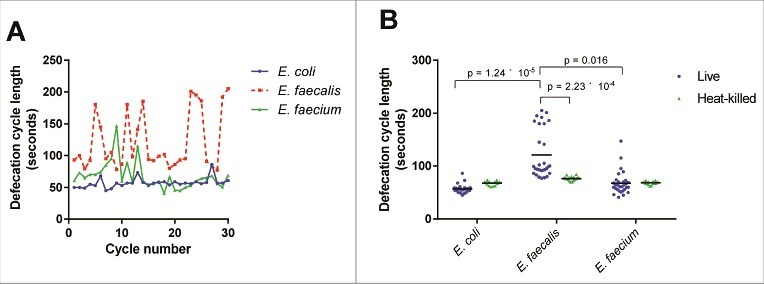

We hypothesized that the efficient colonization of the intestine by enterococci may be at least in part a consequence of a decreased defecation rate, as described for other Gram-positive bacterial infections [20]. Indeed, E. faecalis-infected C. elegans displayed a highly irregular and longer defecation rhythm than E. coli-fed worms (Fig. 3A). E. faecium-infected C. elegans exhibited a somewhat intermediate phenotype, and C. elegans fed on heat-killed bacteria, whether E. coli, E. faecalis, or E. faecium, had similar mean defecation cycle lengths (68.1, 76.5, and 68.6 seconds, respectively) (Fig. 3B). Although the underlying mechanism is not clear, these data suggest that the extent of disruption of the normal defecation rhythm correlates with worm killing, but that the relatively modest decrease in defection rate observed in the case of E. faecium is most likely not solely responsible for the accumulation of E. faecium in the C. elegans intestine.

Figure 3.

Live E. faecalis perturbs defecation cycle length in C. elegans. (A) Sequential defecation cycle lengths (time between consecutive contractions of the posterior body wall muscle) in wild-type C. elegans fed on E. coli, E. faecalis, or E. faecium. (B) Defecation cycle lengths in L4 worms fed E. coli, E. faecalis, or E. faecium, either live or heat-killed, for 24 hours. Mean defecation cycle lengths are indicated with horizontal bars. Results are representative of 3 independent assays. Relevant statistically significant differences are indicated with a bracket. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired t-test and the Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison correction.

The Enterococcus infection gene signature

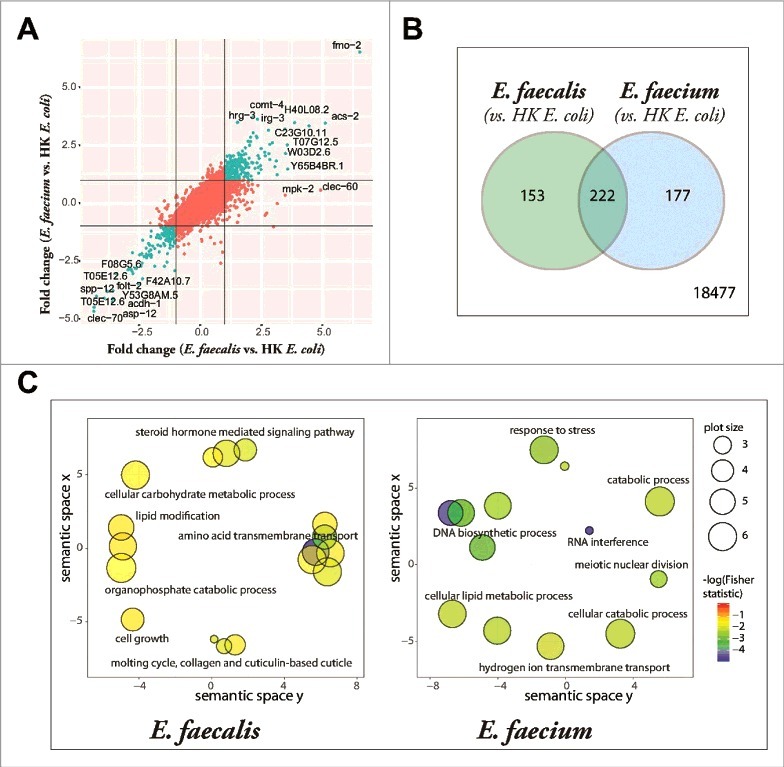

We characterized the C. elegans host response to Enterococcus infection with whole-genome transcriptional profiling of Enterococcus-infected young adult C. elegans using Affymetrix GeneChip® technology. The transcriptional profile of C. elegans fed heat-killed E. coli was used as a control because live E. coli is pathogenic to C. elegans on BHI agar, the rich medium required for E. faecalis and E. faecium growth [12]. Using a fold-change cutoff of 2-fold (relative to heat-killed E. coli) and a Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-value of 0.05, we identified 375 differentially expressed genes (235 upregulated, 140 downregulated) in the E. faecalis infection compared to E. coli (S1 Table) and 399 differentially expressed genes (244 upregulated, 155 downregulated) in the E. faecium infection (S2 Table). Plotting the fold changes of the transcripts induced by E. faecalis against those induced by E. faecium, each relative to the heat-killed E. coli control, revealed a high degree of correlation between the two signatures, both for genes upregulated by both pathogens (upper right quadrant), as well as those downregulated by both pathogens (lower left quadrant) (Fig. 4A). The overlapping infection gene signature of E. faecalis and E. faecium contained 222 genes (p = 1.37 × 10−295, Fig. 4B and S3 Table) and was overrepresented by genes associated with amino acid metabolism, oxidation-reduction, lipid metabolism, and the innate immune response, as determined by gene ontology term analysis (S3 Table). Among the effector genes upregulated by infection with Enterococcus were three genes that had previously been demonstrated to mediate C. elegans resistance to pathogens: sodh-1 (sorbitol dehydrogenase) and cyp-37B1 (cytochrome P450), whose decreased expression caused enhanced susceptibility to killing by S. aureus [1], and ilys-3, an invertebrate lysozyme effector required in the pharynx and in the intestine to prevent the accumulation of bacterial cells in the gut lumen and to protect against M. nematophilum [21].

Figure 4.

Enterococcus infection gene signature. (A) Fold-change by fold-change plot, depicting E. faecalis-infected C. elegans with E. faecium-infected C. elegans (relative to heat-killed E. coli-fed controls). Genes differentially expressed by both E. faecalis and E. faecium (relative to HK E. coli, |FC| > 2) are highlighted in aquamarine. 18,477 annotated Affymetrix probes were found to not be differentially expressed in either comparison. (B) The set of differentially expressed genes (|FC| > 2, BH-adjusted p-value < 0.05) in the E. faecalis infection signature (375) shared a significant overlap with genes differentially expressed in the E. faecium infection (399), p = 1.37 × 10295. (C) Functional classification summary of the differentially expressed genes that are exclusive to either E. faecalis (left) or E. faecium (right), relative to heat-killed E. coli. Similar functional categories of GO terms were clustered together in two-dimensional space using REViGO, a visualization tool that uses a clustering algorithm to represent GO data by plotting their semantic similarity. The bubble color indicates the Fisher test statistic while the bubble size is proportional to the frequency of GO terms in the GO annotation database. Colors corresponding to log10 Fisher test statistic are provided in the legend.)

Although there were many similarities between the E. faecalis and E. faecium gene signatures, there were other facets of the gene signatures that differed between the two species. Using gene ontology term enrichment (Fig. 4C), we detected that the genes exclusively regulated by E. faecalis (and not E. faecium) revealed an enrichment in genes associated with amino acid transmembrane transport, lipid transport, steroid hormone mediated signaling, and a defense response (S4 Table), while transcripts exclusively regulated by E. faecium were enriched in genes associated with RNA interference, DNA biosynthesis and DNA repair, tRNA aminoacylation for protein translation, and the response to stress (S5 Table).

We hypothesized that genes regulated in response to infection by disparate pathogens may be responding to a shared facet of the infection process, such as signals indicative of host damage. Comparing the datasets of previously published transcriptional profiling with our datasets revealed a significant overlap between the genes regulated by both enterococci and three other pathogens (S4 Fig), S. aureus (S6 Table), P. aeruginosa (S7 Table), and even the fungal pathogen C. albicans (S8 Table).

When we directly compared the arrays from C. elegans infected with E. faecalis to those infected with E. faecium, we noted 18 Affymetrix probes for C. elegans transcripts that were more highly expressed in the E. faecalis infection relative to E. faecium, including the C-type lectins clec-60 and clec-82, a number of hypothetical proteins (e.g., H02F09.2, H02F09.3, C49C8.5, and Y54G2A.37), and an F-box A protein (fbxa-157); only one transcript, the heme responsive gene hrg-3, was more highly expressed by C. elegans infected with E. faecium relative to E. faecalis (S9 Table). We reasoned that genes induced more highly in infection by E. faecalis than E. faecium may be responsive to the virulence of the infection. To address this issue, we compared the set of genes regulated by E. faecalis infection (relative to E. faecium) (S9 Table), to the set of genes differentially regulated by Microbacterium nematophilum, a C. elegans-specific Gram-positive bacterial pathogen, relative to an avirulent M. nematophilum, as this gene set may also include genes that are part of a “virulence signature”. This comparison yielded a small but statistically-significant overlap of three Affymetrix probes to two genes, clec-60 and C49C8.5 (p = 2.27 × 10−7, S10 Table).

Immune pathways are activated by and required for defense against E. faecalis and E. faecium

To validate the set of differentially-expressed genes identified by Affymetrix GeneChip© technology, we designed a 72-gene “CodeSet” for the multiplexed NanoString nCounter® gene expression analysis system [22] that included genes activated or repressed exclusively by E. faecalis (13 genes), exclusively by E. faecium (7 genes), or both (47 genes) compared to heat-killed E. coli-fed controls, along with 5 “housekeeping” control genes. Even though the three different biological replicates tested in the NanoString experiment were a different set of biological replicates from those prepared for the Affymetrix microarray experiment, we observed an excellent concordance between the two experiments, for both E. faecalis- and E. faecium-induced genes (S5 Fig).

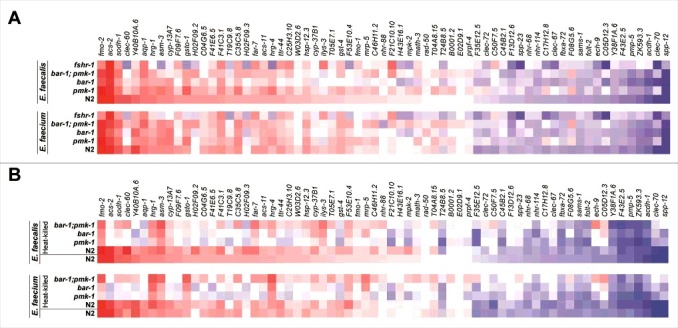

We used the NanoString CodeSet to investigate whether Enterococcus-induced genes are regulated by known immune-related pathways by profiling wild-type C. elegans, as well as mutants deficient in pmk-1, bar-1, or fshr-1, each infected with E. faecalis or E. faecium (Fig. 5A). These NanoString experiments led to four major conclusions. First, we found that the expression profiles of the 72 genes represented by the NanoString CodeSet in the different immune mutants were very similar for both E. faecalis and E. faecium (S6 Fig). This was at least partially expected given that the CodeSet was populated with some of the most highly upregulated and downregulated genes identified following E. faecalis or E. faecium infection, many of which overlapped between the two enterococcal species.

Figure 5.

Induction of Enterococcus-activated genes through known C. elegans immune pathways and by heat-killed bacteria. (A) Heat-map of Enterococcus-activated genes in wild-type N2 worms or immune pathway mutant worms (pmk-1(km25), bar-1(ga80), pmk-1(km25);bar-1(ga80), and fshr-1(ok778)), during infection with E. faecalis (top panel) or E. faecium (bottom panel). The heat-map reflects data from 2–3 biological replicates for each mutant analyzed. (b) Heat-map of Enterococcus-activated genes in wild-type N2 or immune pathway mutant worms, after 8 hours of exposure to heat-killed E. faecalis (top panel) or heat-killed E. faecium (bottom panel). For comparison, induction in N2 wild-type worms by live E. faecalis or E. faecium is shown in the bottom row of each panel. The heat-map reflects data from 2–3 biological replicates for each mutant analyzed. Genes are ordered by their degree of induction on E. faecalis in N2 worms, from red (most highly upregulated) to blue (most highly downregulated).

Second, the disruption of each of the three immune pathways hampered the induction of at least some of the Enterococcus-activated genes. Most strikingly, the fshr-1 mutation abrogated expression of clec-60, Y40B10A.6, hrg-1, asm-3, gsto-1, H02F09.2, hrg-4, W03D2.6, and cyp-37B1, among a number of other genes, which was unexpected, because fshr-1 was first identified as a regulator of a set of P. aeruginosa response genes, some of which are co-activated downstream of PMK-1 [17], and was not previously thought to play an important role in the response to Gram-positive bacterial pathogens.

Third, mutation of none of the pmk-1, fshr-1, or bar-1 immune pathways abrogated the induction of all the Enterococcus-activated genes, though removal of any one of the pathways affected the induction of at least some of the Enterococcus-activated genes. Moreover, it appeared that wild-type expression of some genes (e.g., clec-60, F09F7.6, T19C9.8, H02F09.2, H02F09.3, and T24B8.5) depended at least in part on multiple pathways.

Fourth, some of the most highly upregulated genes in the E. faecalis infection appear to be negatively regulated by the pmk-1, fshr-1, and bar-1 pathways (e.g., clec-60, T19C9.8, and ilys-3).

A separate NanoString experiment showed that the pmk-1, fshr-1, and bar-1 pathways regulate Enterococcus-activated genes in the absence of pathogen attack (i.e., at steady state, when worms were only fed heat-killed E. coli OP50) (S7 Fig).

Live and dead enterococci elicit similar gene expression profiles

Given the similarities between the C. elegans host response to E. faecalis and E. faecium infection, we hypothesized that the response might be driven by the perception of shared MAMPs between the two enterococcal species. To test this hypothesis, we used the NanoString CodeSet to compare the gene expression profile of N2 wild-type C. elegans fed heat-killed E. faecalis or E. faecium to that of N2 wild-type C. elegans fed live E. faecalis or E. faecium, respectively. The rationale for this experiment was that MAMPs are typically heat-stable components of microbial cell walls. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found the gene expression profiles elicited by live or dead E. faecalis, or live or dead E. faecium, to be extremely similar (Fig. 5B, bottom two rows of the upper and lower panels). Moreover, the induction of these genes by heat-killed E. faecalis or E. faecium was dependent on the immune regulators PMK-1 and BAR-1. Although the gene expression profiles of N2 worms fed live or heat-killed bacteria (E. faecalis or E. faecium) were highly correlated, the immune mutants clustered more closely based on whether they were exposed to heat-killed or live enterococci (S6 Fig), suggesting that there may be some conserved features of the response to heat-killed versus live Enterococci that are independent of the particular immune mutants.

Together, these gene expression profiling experiments show that C. elegans responds transcriptionally to live and dead Enterococcus similarly, and that full induction of these Enterococcus-activated genes are dependent upon known immune pathways. These results suggest that the perception of and response to Enterococcus is mediated by conserved heat-stable moieties, potentially including MAMPs synthesized by E. faecalis and E. faecium.

Enterococcus-activated effectors are induced by both species, but are regulated by different pathways

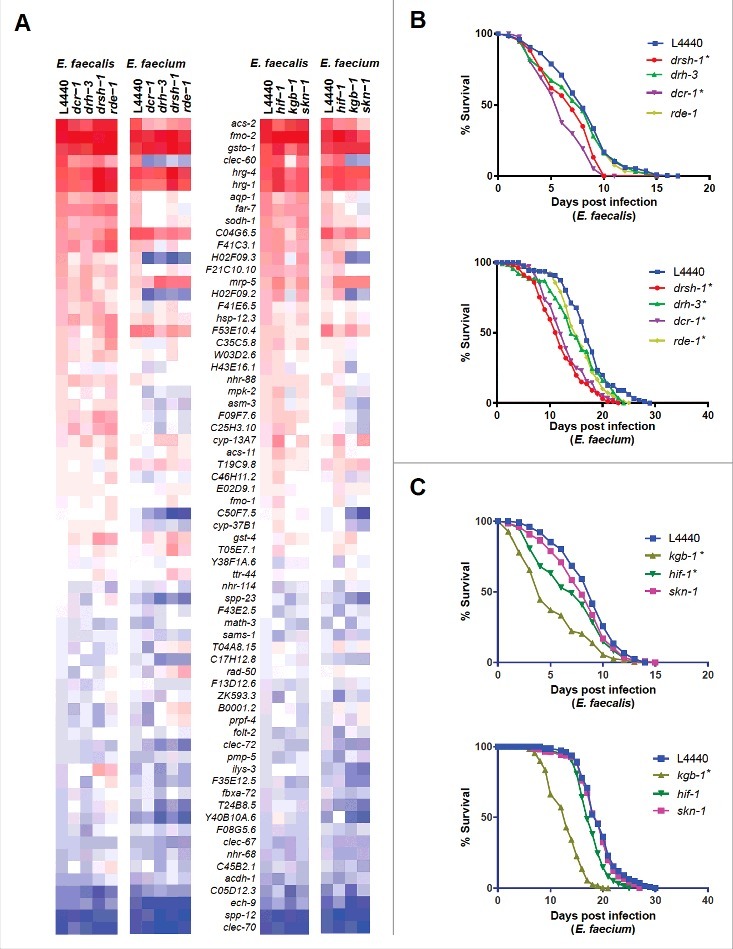

From the gene ontology analysis (Fig 4C), we noted that genes related to RNA interference were enriched among the genes exclusive to the E. faecium infection signature. To test the importance of these genes in the host transcriptional response to E. faecium, we knocked down four RNAi-related genes that were differentially upregulated in the E. faecium infection signature: dcr-1 (Dicer), drh-3 (Dicer-related helicase-3), drsh-1 (Drosha), and rde-1 (one of the 27 C. elegans argonaute proteins). Knocking down these genes impaired the induction of a sizable subset of the Enterococcus-activated genes represented by the nCounter CodeSet (including clec-60, aqp-1, far-7, H02F09.2, H02F09.3, H43E16.1, mpk-2, asm-3, F09F7.6, and C25H3.10) following infection with E. faecium, but not E. faecalis (Fig. 6A, left two panels). Additionally, these small RNA pathway-related genes regulate the basal expression of the tested Enterococcus-activated genes when worms were feeding on E. coli OP50 (S8 Fig). To evaluate the role of the small RNA processing machinery in defense against Enterococcus, we knocked down the same four RNAi-related genes and then assayed for susceptibility of the worms to either E. faecalis or E. faecium. Worms deficient in either dcr-1 or drsh-1 exhibited enhanced susceptibility to E. faecalis or E. faecium; in contrast, C. elegans deficient in drh-3 and rde-1 were much more susceptible to E. faecium than E. faecalis (Fig. 6B). Importantly, knockdown of drsh-1, drh-3, and rde-1 had no effect on lifespan on heat-killed E. coli and knockdown of dcr-1 had only a marginal effect (S8 Fig). These results indicate that the small RNA processing pathway in C. elegans is required for defense against Enterococcus, but may be differentially required and regulated in defense against the two enterococcal species.

Figure 6.

Stress response pathways are required for defense against Enterococcus. (a) Heat-map of the fold-changes of Enterococcus-activated genes in N2 worms treated with RNAi against C. elegans small RNA pathway components (drsh-1, drh-3, dcr-1 or rde-1) (two panels on left) or stress response pathway components (hif-1, kgb-1, or skn-1) (two panels on right) or vector control (L4440) during infection with E. faecalis or E. faecium relative to heat-killed E. coli control. The heat-map reflects data from 2 biological replicates for each mutant analyzed. (b) Effect of Enterococcus infection on the survival of fer-15(b26);fem-1(hc17) C. elegans treated with L4440 vector control, drsh-1, drh-3, dcr-1 or rde-1 RNAi. (c) Effect of Enterococcus infection on the survival of fer-15;fem-1 C. elegans treated with L4440 vector control, kgb-1, hif-1 or skn-1 RNAi strains. For (b) and (c), each graph shows the average of three plates for each strain, with each plate containing 30–40 worms. results are representative of 3 independent assays and statistical significance of differences between survival curves was calculated using Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis. Relevant statistically significant survival curves (relative to control) are marked with asterisks.

Because dcr-1 mutants are compromised in a variety of stress response pathways [23], we also assessed the role of several stress-related regulatory genes in the induction of Enterococcus-activated genes. We found that knockdown of the JNK kinase KGB-1 [24] or the transcription SKN-1 [25], or to a lesser extent the transcription factor HIF-1 [26, 27] affected the induction of these genes in response to E. faecium but to a much lesser extent in E. faecalis (Fig. 6A, right two panels). Furthermore, the expression profiles of the RNAi-deficient worms following E. faecium infection were highly correlated to worms deficient in skn-1 and kgb-1 (S9 Fig). These stress-related genes also regulate the basal expression of Enterococcus-activated genes (S10 Fig), though not to the same degree as the previously examined immune pathways (PMK-1, BAR-1, etc.). Worms deficient in kgb-1, but not skn-1 or hif-1, showed hypersensitivity to both enterococcal species (Fig. 6C). This was somewhat surprising because skn-1 appears to play a larger role than kgb-1 in the induction of the Enterococcus-activated genes following E. faecium infection. A caveat is that knockdown of kgb-1 (but not skn-1 or hif-1), caused a partial decrease in lifespan on heat-killed E. coli (S10 Fig). Furthermore, the skn-1 mutant has previously been shown to be hypersusceptible to E. faecalis infection [28, 29], and it is possible that knockdown by feeding RNAi may be generating only a weak “loss of function”. Taken together, these data suggest that canonical stress-response pathways play an important role in the C. elegans response to E. faecium.

Nuclear hormone receptors contribute to the differential stress response of E. faecalis and E. faecium

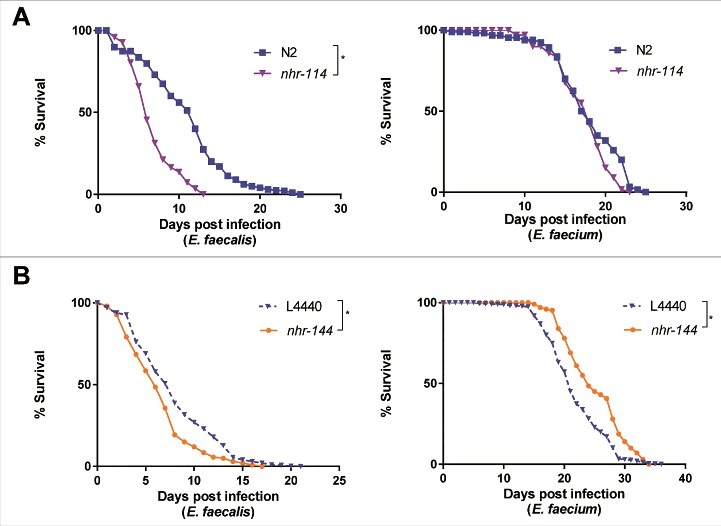

Although stress-response pathways appear to be selectively required for the induction of immunity-related genes in response to E. faecium but not E. faecalis (Fig. 6A), only knockdown of kgb-1 had a significant effect on the susceptibility to E. faecalis (Fig. 6C). We therefore reasoned that other pathways related to stress might explain the differential transcriptional response of E. faecalis and E. faecium. In this regard, we noted that steroid hormone mediated signaling pathway genes were enriched among the genes exclusively regulated by E. faecalis (S4 Table), many of which were nuclear hormone receptors (NHRs). NHRs comprise a family of transcription factors regulated by small lipophilic hormones and have been demonstrated to regulate gene expression in response to a variety of environmental signals [30]. To assess the role of a panel of the NHRs up- or downregulated by enterococcal infection (relative to heat-killed E. coli control) from the microarray data (S4 Table), we examined the survival of C. elegans in which these NHRs were mutated or knocked down using feeding RNAi (S11 Fig). Among the NHRs tested, we identified two, which when knocked down, exhibited opposite phenotypes following infection with E. faecalis or E. faecium: loss of function of nhr-114 or knockdown of nhr-144 led to increased susceptibility to E. faecalis infection (Fig. 7A and B, left), whereas loss of function of nhr-114 had no effect on resistance to E. faecium, and knockdown of nhr-144 led to modest but significant resistance to E. faecium, relative to worms fed an E. coli vector control (Fig. 7A and B, right). Importantly, loss of function of either NHR had no statistically significant effect on longevity on heat-killed E. coli (S12 Fig). These data suggest that nuclear hormone receptors and their downstream signaling partners may be playing an important role in immunity.

Figure 7.

Nuclear hormone receptors are required for defense against Enterococcus. (a) Effect of E. faecalis and E. faecium infection on the survival of wild-type N2 and nhr-114(gk849). (b) Effect of E. faecalis and E. faecium infection on fer-15(b26);fem-1(hc17) C. elegans treated with L4440 vector control or nhr-144 RNAi. Results are representative of 2 independent assays. Each graph shows the average of three plates for each strain, with each plate containing 30–40 worms. Relevant statistically significant survival curves (relative to control) are marked with asterisks and a bracket. Statistical significance of differences between survival curves was calculated using Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis.

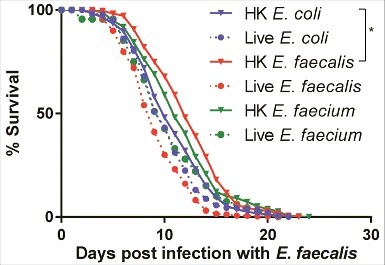

Prior exposure of C. elegans to heat-killed Enterococcus confers E. faecalis resistance

Because heat-killed E. faecalis or E. faecium are not pathogenic but induce a similar transcriptional response to live E. faecalis or E. faecium, we reasoned that pre-exposure of C. elegans to either heat-killed E. faecalis or E. faecium might render worms more resistant when subsequently challenged by a later E. faecalis infection, as hormeotic conditioning that protects from subsequent lethal infection has been described previously in worms [31–33]. We exposed C. elegans to heat-killed E. coli, E. faecalis, or E. faecium, or to live E. faecalis or E. faecium for eight hours, after which these “pre-exposed” worms were transferred to a lawn of live E. faecalis (Fig. 8). Indeed, conditioning with heat-killed E. faecalis afforded a statistically significant level of resistance to E. faecalis (34% increase in mean lifespan with heat-killed E. faecalis treatment vs. heat-killed E. coli, p = 0.04). Pre-treatment with heat-killed E. faecium also appeared to render C. elegans somewhat more resistant (32% increase in mean lifespan vs. heat-killed E. coli, p = 0.08). However, pre-treatment with either B. subtilis or S. aureus, alive or heat-killed, conferred no protection (S13 Fig). Furthermore, the extension in lifespan by pre-treatment with heat-killed E. faecalis was not conferred transgenerationally (S13 Fig). Although these data suggest that heat-killed E. faecalis and E. faecium elicit a potentially protective, pathogen-specific defense response that renders C. elegans modestly more resistant to subsequent infection with live E. faecalis, it is not clear whether this preconditioning induces a generalized protective stress response or a specific immune-driven response.

Figure 8.

Pre-exposure to heat-killed Enterococci protects against subsequent infection with live E. faecalis. Survival of fer-15(b26);fem-1(hc17) worms exposed to 8 hours of heat-killed bacteria (E. coli, E. faecalis, or E. faecium) or live bacteria (E. faecalis or E. faecium) and then transferred to live E. faecalis. Each graph shows the average of three plates for each condition, with each plate containing 30–40 worms. Results are representative of 2 independent assays. Statistically significant (p<0.05) survival curves that were increased in resistance (relative to HK E. coli) are marked with an asterisk and bracket. Statistical significance of differences between survival curves was calculated using Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis.

Discussion

Previously published work from our laboratory showed that when C. elegans feed exclusively on either E. faecalis or E. faecium, large numbers of bacterial cells accumulate in the C. elegans intestine, which becomes grossly distended. However, only E. faecalis kills the worms, suggesting that C. elegans can normally tolerate a significant E. faecium intestinal infection and that distention of the intestinal lumen and packing with bacteria per se does not necessarily impact worm longevity. Here we extended these initial observations by transmission electron microscopic ultrastructural imaging, which showed that both E. faecalis and E. faecium pack the intestinal lumen. However, whereas the majority of E. faecalis cells appear to be viable since they stain darkly in the TEM images, a significant fraction of the E. faecium cells appear to be nonviable. This correlates with the observation that there are about 5 times as many E. faecalis cells that accumulate in individual worms and that can form colonies compared to E. faecium cells. Compared to wild-type worms, pmk-1 immuno-deficient worms accumulate several fold more viable E. faecium cells, which correlates with the observation that the pmk-1 mutant is killed by E. faecium whereas wild-type worms are tolerant to the infection. On the other hand, although the pmk-1 mutant is also more susceptible to killing by E. faecalis than wild-type worms, the bacterial load is about the same. The simplest explanation of these data is that C. elegans tolerates an E. faecium load of ∼3 × 104 cells/worm in a pmk-1-dependent manner without impairing worm longevity. In pmk-1 mutant worms, E. faecium accumulates to about a 5-fold higher level than in wild-type worms, which negatively impacts worm longevity. The higher bacterial load in an E. faecalis infection than in an E. faecium infection correlates with a more severe decrease in longevity. The reason that E. faecalis does not accumulate to higher titers in a pmk-1 mutant than in wild type may be that the intestine simply cannot accommodate any additional bacterial cells.

We also show by transmission electron microscopic ultrastructural imaging that intestinal distention, even late in infection, appears to occur in the absence of any extensive host damage, even though E. faecalis kills the worms. In contrast, previous ultrastructural studies have shown that C. elegans lethality caused by P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus is accompanied by severe host cellular damage [1]. Despite the fact that neither E. faecalis nor E. faecium caused any obvious host damage, genome-wide transcriptional profiling showed that both enterococcal species elicited a relatively robust immune response and that 45% of the C. elegans genes differentially upregulated by E. faecalis infection relative to the heat-killed E. coli control were also differentially upregulated by E. faecium.

Testing a subset of 67 genes differentially regulated by E. faecalis, E. faecium or both using nanoString analysis showed that heat-killed E. faecalis and heat-killed E. faecium elicited most of the same genes as live E. faecalis (Fig. 5B). These experiments suggest that the primary immune response elicited by E. faecalis and E. faecium is not activated by host damage but rather by heat-resistant pattern recognition molecules, although it is formally possible that heat-killed Enterococci may induce a DAMP-triggered response in the C. elegans intestine. Even though C. elegans – pathogen interactions have been studied now for almost 20 years, it is not known what bacterial MAMPs, if any, are recognized by C. elegans, or what, if any, PRRs exist in the C. elegans genome to detect pathogens. Previous studies using Candida albicans or S. aureus showed that the heat-killed pathogen induced many of the same C. elegans genes as a live infection. In contrast, in the case of P. aeruginosa live bacterial cells are required to elicit a C. elegans immune response that is proportional to the killing ability of the P. aeruginosa strain [1,6). Further studies showed that host cellular damage such as that caused by the inhibition of protein synthesis by P. aeruginosa exotoxin A was sufficient to elicit a robust immune response [6,7,11].

Consistent with the conclusion that heat-killed E. faecalis elicits a similar transcriptional response as live E. faecalis, preconditioning worms with heat-killed E. faecalis for just 8 hours was sufficient to extend host survival by 1.5 days following subsequent E. faecalis infection. This is a relatively modest shift in lifespan, but in the wild may afford the worms an evolutionary advantage to escape, survive, and lay more eggs. Hormeotic conditioning in C. elegans has been described previously in response to exposure to either pathogenic or avirulent strains of E. coli – which induce slightly different, although somewhat overlapping, protective immune responses – prior to infection with entero-pathogenic E. coli (EPEC) [32]. Other studies have shown that pre-exposure of C. elegans to the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus enhanced Gram-positive, but not Gram-negative, immune responses in the host [33]. Additionally, pre-treatment of C. elegans with E. faecium, but not E. coli or B. subtilis, appears to promote pathogen tolerance through secreted E. faecium peptidoglycan hydrolase SagA in a tol-1 dependent manner [35]. Though E. faecium does not appear to promote pathogen tolerance to E. faecalis in our studies, this may be because the TOL-1 immune pathway is more important in the S. typhimurium defense response than in E. faecalis.

Importantly, even though E. faecium does not kill wild-type worms, mutating previously described immune or stress response signaling pathways allows E. faecium to kill the worms, demonstrating that E. faecium is a weak C. elegans pathogen. In other words, the activation of canonical immune and stress response pathways in wild type worms make them tolerant to an E. faecium infection.

Interestingly, we observed that the maximal lifespan of C. elegans fed live E. faecium was considerably longer that the lifespan of worms fed heat-killed E. faecalis (30 vs. 20 days) (compare Fig. 2B and Fig. 2C). One potential explanation is that E. faecalis makes a heat stable toxin that contributes to worm killing, whereas E. faecium does not. If E. faecalis makes such a toxin, its ability to kill would have to be PMK-1-independent, since wild-type and pmk-1 mutant worms have the same lifespans on heat-killed E. faecalis (20 days) (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the presumptive toxin could not be primarily responsible for the bulk of the immune gene induction shared between the E. faecalis and E. faecium infection gene signatures, since E. faecium presumably does not make the toxin. It is also possible that such a toxin might be at least partially responsible for the priming effect observed with E. faecalis. Heat-stable toxins have previously been explored in P. aeruginosa infection of C. elegans [36–38], and have been postulated as an explanation for the observation that live and heat-killed S. aureus both elicited the expression of a panel of immune response genes [1]. An alternative explanation for the longer lifespan of live E. faecium compared to heat-killed E. faecalis is that E. faecium induces a particularly effective immune response that abrogates killing.

NanoString multiplexed gene expression analysis examining the expression of E. faecalis and E. faecium activated genes showed that the previously-described PMK-1, FSHR-1, and BAR-1 immune pathways contribute to host defense (Fig. 5) and that these immune and stress response pathways appear to activate many common genes (Figs. 5 and 6). In addition, genetic epistasis analysis showed that the PMK-1 and FSHR-1 and the PMK-1 and BAR-1 pathways appear to act independently of each other (Fig. 2). These data are consistent with previous studies showing that C. elegans has several parallel immune pathways that converge upon a set of shared, but nevertheless distinct set of putative immune effectors, presumably allowing C. elegans to integrate and fine-tune the defense response to various combination of MAMPs, DAMPs, and other elicitors. The activation of multiple pathways may also act as a safeguard against pathogens that attempt to subvert host defense by targeting an upstream signaling molecule.

One somewhat unexpected finding was that the FSHR-1 signaling pathway is activated by both E. faecalis and E. faecium, and that FSHR-1 is required for wild-type level of resistance to both pathogens. Another surprising finding was that the infection with E. faecium but not E. faecalis elicited a change in a variety of immune and stress response genes that appear to be dependent on SKN-1, KGB-1, and small RNA processing. One possible explanation is that in the case of an E. faecium infection, FSHR-1 activates a variety of stress and immune genes through the coordinated activity of the small RNA processing pathway, KGB-1, and SKN-1, whereas in E. faecalis, FSHR-1 activates these downstream putative effectors independently of the stress pathways.

Taken together, our study sheds new light on how Enterococcus infection disrupts host physiology, the differential response of C. elegans to E. faecalis and E. faecium, as well as potential ways in which C. elegans recognizes and responds to bacterial infection.

Materials and methods

Strains and growth conditions

All C. elegans strains were maintained on nematode growth media (NGM) and fed E. coli strain OP50, as previously described. The C. elegans strains used in this study are wild-type N2 Bristol, pmk-1(km25), fshr-1 (ok778), pmk-1(km25); fshr-1(ok778), bar-1(ga80), bar-1(ga80);pmk-1(km25), nhr-68 (gk708), nhr-101 (gk586), and nhr-114 (gk849). The bar-1(ga80);pmk-1(km25) mutant was a gift of Javier Irazoqui and the pmk-1(km25); fshr-1(ok778) was generated in our lab [17]; all others were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center. Unless otherwise stated, the E. coli, E. faecalis, E. faecium, and B. subtilis strains used in this study correspond to strains OP50 [39], MMH594 [40], E007 [12], and PY79 sigF::kan (gift of Richard Losick), respectively.

Nematode killing assays

For all enterococcal killing assays, starter cultures of E. faecalis or E. faecium strains were prepared from single colonies inoculated into 5 ml of BHI broth and were incubated for 6–8 hours with shaking at 37°C. Afterward, 10 μL of log phase cultures were spread onto 35 mm brain-heart infusion (BHI) agar plates containing 10 μg/ml kanamycin, and incubated at 37°C overnight (16–20 hours) [13]. Before use, the plates were allowed to equilibrate to room temperature. Approximately 40–50 late L4-staged C. elegans worms were then transferred from a lawn of E. coli OP50 on NGM medium to BHI medium-grown Enterococcus, taking care to transfer as little E. coli as possible from the maintenance plates to the killing plates. Nematodes were placed outside of the lawn on the bare agar. The plates were then incubated at 25°C, and every 24 hours, worms were examined for viability using a dissecting microscope. Worms that did not respond to a gentle touch with a platinum wire pick to the head, body, and tail were scored as dead. As E. faecium-infected-C. elegans do not move much when they are near death, even when prodded, special attention had to be paid to head movement and pharyngeal pumping to determine whether the nematodes were alive. Worms that did not move were scored as dead, counted, and picked off the killing plate; worms that died from crawling off the agar were also picked off the plate, but were censored from the assay. Worms that were found to be still moving were scored as alive and were also counted.

Each experimental condition was tested in triplicate. Kaplan-Meier log rank analysis was performed to determine the statistical significance of the difference in survival curves using OASIS [41], an online, publicly available tool that provides Kaplan-Meier estimates and mean/median survival time by based on censored survival data. Bonferroni-corrected p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RNAi feeding experiments

RNAi constructs were obtained from the publicly available Ahringer RNAi library [41]. All clones were verified by sequencing. For RNAi experiments, starter cultures of RNAi expressing E. coli HT115 bacterial clones were grown overnight in LB (25 ug/ml carbenicillin and 10 ug/ml tetracycline) at 37°C, followed by further growth for 4–6 hours in a larger volume of LB (carbenicillin) at 37°C. NGM plates containing 5 mM IPTG and 100 μg/ml carbenicillin were then seeded with the double-stranded RNAi-expressing HT115 bacteria [42]. The dsRNA within the bacteria was induced over two days at room temperature, after which L1 worms, synchronized by hypochlorite treatment and L1 arrest [43], were added to the plates. Worms were fed through the L4 stage with dsRNA-expressing bacteria to target genes of interest.

Defecation assays

N2 or pmk-1 worms were grown to the L4 stage and were then picked to Enterococcus or E. coli-seeded plates and incubated at 25°C for 8 or 24 hours. For scoring, worms were then moved to room temperature, allowed to acclimate for 30–60 minutes, and their defecation phenotype was scored by assessing the time between expulsions (which are preceded by posterior and anterior body wall muscle contraction, and the contraction of enteric muscles in a normally regular pattern) [44]. Defecation cycles were also followed in individual L4 worms for 30 consecutive cycles for some experiments. In general, more than 20 worms were scored and experiments were performed in duplicate. The significance of differences in values between conditions was determined using unpaired two-tailed Student t tests, with unequal variance.

RNA isolation

C. elegans N2 wild-type animals were synchronized by hypochlorite treatment and L1 arrested. Arrested L1 worms were allowed to grow on NGM media seeded with OP50 and grown at 20°C until they reached the young adult stage. Young adults were then washed three times in M9W buffer and transferred to BHI (10 µg/ml) plates seeded with heat-killed E. coli OP50, live B. subtilis PY79, live E. faecalis MMH594, or live E. faecium E007. Worms were treated as described for the killing assays, with the exception that approximately ∼2,000 worms were plated onto each 10-cm assay plate. After 8 hours at 25°C, the treated worms were washed three times in M9W, resuspended in TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), per the manufacturer's instructions, and frozen at −80°C. Once thawed, total RNA was prepared and then further purified through an RNeasy column (Qiagen). Three independent replicates of each treatment were isolated.

For the multiplexed gene expression profiling studies using NanoString nCounter, the same protocol was followed, except altering the C. elegans strain (genotype) or the type of bacteria, depending on the experiment. Two or three independent replicates of each treatment were carried out.

For feeding of C. elegans with heat-killed bacteria, bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, washed thrice in a large excess of M9W, concentrated 25x and incubated at 95°C for 90–120 minutes. The heat-killed bacterial suspension was equilibrated to room temperature before it was added to BHI agar plates and allowed to dry under a sterile hood with heat. Once dry, these plates were allowed to once again equilibrate to room temperature before worms were added to them.

NanoString nCounter analysis

RNA was analyzed by NanoString nCounter Gene Expression Analysis (NanoString Technologies) using a “CodeSet” designed in consultation with NanoString Technologies that contained probes for 72 C. elegans genes of interest. Probe hybridization, data acquisition and analysis were carried out per instructions from NanoString. Each RNA sample was normalized to the housekeeping genes snb-1, ama-1, act-1, pmp-3, and tba-1 using the nSolver Analysis software (NanoString Technologies).

Transmission electron microscopy

C. elegans were fixed overnight at 4°C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, 1.0% paraformaldehyde in 0.05M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4 plus 3.0% sucrose. The cuticles were nicked with a razor blade in a drop of fixative under a dissecting microscope to allow the fixative to penetrate. After 1 hour fixation at room temperature, the worms were fixed overnight at 4°C. After several rinses in 0.1M cacodylate buffer, the samples were post-fixed in 1.0% osmium tetroxide in 0.1M cacodylate buffer for one hr at room temp. They were rinsed in buffer and then in double distilled water and stained, en bloc in 2.0% aqueous uranyl acetate for 1 hour at room temperature. After rinsing in distilled water, the last rinse was carefully drawn off and the worms were embedded in 2.0% agarose in PBS for ease of handling.

The agarose blocks were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol to 100%, then into a 1:1 mixture of ethanol:EPON overnight on a rocker. The following day, the agarose blocks were further infiltrated in 100% EPON for several hours and then were embedded in fresh EPON overnight at 60°C. Thin sections were cut on a Reichert Ultracut E ultramicrotome, collected on formvar-coated gold grids, post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed in a JEOL 1011 TEM at 80 kV equipped with an AMT digital imaging system (Advanced Microscopy Techniques, Danvers, MA). Transmission electron microscopy studies were carried out at the MGH Microscopy Core, Program in Membrane Biology.

Colony forming unit assay of bacterial colonization

Infected C. elegans were picked onto plain NGM agar plates to allow them to wriggle off any external bacteria and then picked again to another plain NGM agar plate. Afterward, worms were transferred to a 2-ml microcentrifuge tube containing 25 mM tetramisole hydrochloride and 0.01% Triton X-100 in M9W buffer to inhibit expulsion of bacteria from the worm intestine and wash any adherent external bacteria. The infected worms were washed 5–6 times in the abovementioned buffer, and the volume was brought to a total of 250 µl. 200µl of buffer was removed and plated to determine the number of colony forming units outside the worm intestine. Approximately 400 mg of 1.0-mm silicon carbide particles (Catalog no. 11079110sc; Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) and 100 µl of M9W buffer containing 20 mM levamisole and 2% Triton were added to each tube, and the tubes were vortexed at maximum speed for one minute to release the bacteria from the worm intestine without impairing bacterial viability. The resulting suspension was serially diluted and plated onto BHI agar plates (Nunc® OmniTray Single-Well Plates, Thermo Scientific Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing 10 µg/ml kanamycin to enumerate the number of intestinal CFUs per worm.

Microarray analysis

RNA integrity was confirmed using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) analysis. All samples had an RIN of 10. The RNA samples were hybridized to the Affymetrix C. elegans Genome Array GeneChips, following manufacturer protocols, at the Joslin Advanced Genomics and Genetics Core (Boston, MA). All samples were run in triplicates, except for the heat-killed E. coli control, which was run in quadruplicates.

Affymetrix software was used to obtain raw probe-level chip data (.CEL files). Subsequent analysis was performed in the R programming environment following the differential gene expression analysis workflow described in [45]. Background adjustment, quantile normalization and summarization were performed on the .CEL files by Robust Multiarray Averaging (RMA) [46–48]. From this preprocessed data, differentially expressed genes were identified using the Limma (linear models for microarray data) package in R language [49]. Genes of low median intensity (< 10th percentile) were filtered and adjusted P-values were calculated using the Benjamini and Hochberg (BH) method. A log fold change > 1.0 and BH-adjusted P < 0.05 was used as a threshold to determine pathogen- or treatment-specific gene signatures. An identical analysis was performed using publicly available microarray datasets (Table S11) of C. elegans infection to calculate additional pathogen-specific gene signatures. Gene ontology based enrichment analysis was performed using the topGO package [50] and the results were plotted using ReViGO [51]. Microarray data are available from the National Center for Biotechnology Information/GEO repository under accession no. GSE95636.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, P01-AI083214, National Science Foundation, Graduate Research Fellowship.

Financial disclosures statement

The authors declare that they have no relevant or material financial interests that relate to the research described in this paper.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Author summary

The enterococci are natural commensals of the human gastrointestinal tract and important hospital-borne pathogens, with the majority of human enterococcal infections caused by two species, Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium. Many mechanistic details remain to be determined concerning how enterococci perturb their host and how the host defends itself in the wake of infection. The free-living nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, because of its simple body plan and amenability to genetic analysis, has been used extensively to dissect essential mechanisms of host-pathogen interactions. E. faecalis distends the C. elegans intestine, induces intestinal stasis, and later kills the worm, whereas E. faecium simply distends the intestine without killing. We find that these different modes of infection translate to surprisingly similar C. elegans gene expression profiles during infection as well as during exposure to heat-killed E. faecalis or E. faecium. On the other hand, there are also some key differences in the immune and stress pathways activated by these two enterococcal species. This study elucidates the mechanisms by which enterococci perturb host physiology, as well as the means by which C. elegans detects and then defends itself from these pathogens, with prospective implications for immunity and infection in all metazoans.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Ausubel lab for comments and experimental advice; Mary McKee for technical assistance in TEM experiments; Daniel Kalman for helpful discussions; and Yan Wang, Ruslan Sadreyev, and Suresh Gopalan for helpful discussions concerning the analysis of transcriptional profiling data. We are also grateful to the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center for worm strains.

References

- [1].Irazoqui JE, Troemel ER, Feinbaum RL, et al.. Distinct Pathogenesis and Host Responses during Infection of C. elegans by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000982. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pujol N, Link EM, Liu LX, et al.. A reverse genetic analysis of components of the Toll signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2001;11:809–821. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00241-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Couillault C, Pujol N, Reboul J, et al.. TLR-independent control of innate immunity in Caenorhabditis elegans by the TIR domain adaptor protein TIR-1, an ortholog of human SARM. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:488–494. doi: 10.1038/ni1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brandt JP, Ringstad N. Toll-like Receptor Signaling Promotes Development and Function of Sensory Neurons Required for a C. elegans Pathogen-Avoidance Behavior. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2228–2237. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vance RE, Isberg RR, Portnoy DA. Patterns of Pathogenesis: Discrimination of Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Microbes by the Innate Immune System. Cell Host and Microbe. 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Estes K a., Dunbar TL, Powell JR, et al.. bZIP transcription factor zip-2 mediates an early response to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2153–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914643107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].McEwan DL, Kirienko NV, Ausubel FM. Host translational inhibition by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exotoxin A Triggers an immune response in Caenorhabditis elegans. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:364–374. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dunbar TL, Yan Z, Balla KM, et al.. C. elegans detects pathogen-induced translational inhibition to activate immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Govindan JA, Jayamani E, Zhang X, et al.. Lipid signalling couples translational surveillance to systemic detoxification in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:1294–1303. doi: 10.1038/ncb3229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Liu Y, Samuel BS, Breen PC, et al.. Caenorhabditis elegans pathways that surveil and defend mitochondria. Nature. 2014;508:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature13204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Melo JA, Ruvkun G. Inactivation of Conserved C. elegans Genes Engages Pathogen- and Xenobiotic-Associated Defenses. Cell. 2012;149:452–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Garsin DA, Sifri CD, Mylonakis E, et al.. A simple model host for identifying Gram-positive virulence factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10892–10897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191378698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Powell JR, Ausubel FM. Models of Caenorhabditis elegans infection by bacterial and fungal pathogens. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;415:403–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cruz MR, Graham CE, Gagliano BC, et al.. Enterococcus faecalis inhibits hyphal morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 2013;81:189–200. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00914-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Troemel ER, Chu SW, Reinke V, et al.. p38 MAPK regulates expression of immune response genes and contributes to longevity in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kim DH, Feinbaum R, Alloing G, et al.. A conserved p38 MAP kinase pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans innate immunity. Science. 2002;297:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1073759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Powell JR, Kim DH, Ausubel FM. The G protein-coupled receptor FSHR-1 is required for the Caenorhabditis elegans innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2782–2787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813048106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Miller EV, Grandi LN, Giannini JA, et al.. The Conserved G-Protein Coupled Receptor FSHR-1 Regulates Protective Host Responses to Infection and Oxidative Stress. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Irazoqui JE, Ng A, Xavier RJ, et al.. Role for beta-catenin and HOX transcription factors in Caenorhabditis elegans and mammalian host epithelial-pathogen interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17469–17474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809527105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mcghee JD. The Caenorhabditis elegans intestine. In WormBook. 2007. p. 347–367. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gravato-Nobre MJ, Vaz F, Filipe S, et al.. The Invertebrate Lysozyme Effector ILYS-3 Is Systemically Activated in Response to Danger Signals and Confers Antimicrobial Protection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005826. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Geiss GK, Bumgarner RE, Birditt B, et al.. Direct multiplexed measurement of gene expression with color-coded probe pairs. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nbt1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mori M a., Raghavan P, Thomou T, et al.. Role of microRNA processing in adipose tissue in stress defense and longevity. Cell Metab. 2012;16:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mizuno T, Hisamoto N, Terada T, et al.. The Caenorhabditis elegans MAPK phosphatase VHP-1 mediates a novel JNK-like signaling pathway in stress response. EMBO J. 2004;23:2226–2234. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].An JH, Blackwell TK. SKN-1 links C. elegans mesendodermal specification to a conserved oxidative stress response. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1882–1893. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Epstein AC, Gleadle JM, McNeill LA, et al.. C. elegans EGL-9 and mammalian homologs define a family of dioxygenases that regulate HIF by prolyl hydroxylation. Cell. 2001;107:43–54. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00507-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Semenza GL. HIF-1, O(2), and the 3 PHDs: how animal cells signal hypoxia to the nucleus. Cell. 2001;107:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00518-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van der Hoeven R, McCallum KC, Cruz MR, et al.. Ce-Duox1/BLI-3 Generated Reactive Oxygen Species Trigger Protective SKN-1 Activity via p38 MAPK Signaling during Infection in C. elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002453. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Papp D, Csermely P, Sőti C. A Role for SKN-1/Nrf in Pathogen Resistance and Immunosenescence in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002673. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Taubert S, Ward JD, Yamamoto KR. Nuclear hormone receptors in nematodes: Evolution and function. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.04.021; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Pukkila-Worley R, Feinbaum R, Kirienko NV, et al.. Stimulation of host immune defenses by a small molecule protects C. elegans from bacterial infection. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Anyanful A, Easley KA, Benian GM, et al.. 2009; Conditioning protects C. elegans from lethal effects of enteropathogenic E. coli by activating genes that regulate lifespan and innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 5:450–462. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kim Y, Mylonakis E. Caenorhabditis elegans Immune Conditioning with the Probiotic Bacterium Lactobacillus acidophilus Strain NCFM Enhances Gram-Positive Immune Responses. Infect Immun. 2012;80:2500–2508. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06350-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pham LN, Dionne MS, Shirasu-Hiza M, et al.. A specific primed immune response in Drosophila is dependent on phagocytes. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Rangan KJ, Pedicord VA, Wang Y-C, et al.. A secreted bacterial peptidoglycan hydrolase enhances tolerance to enteric pathogens. Science. 2016;353:1434–1437. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf3552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cezairliyan B, Vinayavekhin N, Grenfell-Lee D, et al.. Identification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phenazines that Kill Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003101. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mahajan-Miklos S, Tan MW, Rahme LG, et al.. Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence elucidated using a Pseudomonas aeruginosa-Caenorhabditis elegans pathogenesis model. Cell. 1999;96:47–56. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80958-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Meisel JD, Panda O, Mahanti P, et al.. Chemosensation of Bacterial Secondary Metabolites Modulates Neuroendocrine Signaling and Behavior of C. elegans. Cell. 2014;159:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Huycke MM, Spiegel CA, Gilmore MS. Bacteremia caused by hemolytic, high-level gentamicin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1626–1634. doi: 10.1128/AAC.35.8.1626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yang JS, Nam HJ, Seo M, et al.. OASIS: Online application for the survival analysis of lifespan assays performed in aging research. PLoS One. 2011;6: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kamath RS, Ahringer J. Genome-wide RNAi screening in Caenorhabditis elegans. Methods. 2003;30:313–321. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Powell JR, Ausubel FM. Models of Caenorhabditis elegans infection by bacterial and fungal pathogens. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;415:403–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Thomas JH. Genetic analysis of defecation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1990;124:855–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Klaus B. An end to end workflow for differential gene expression using Affymetrix microarrays. F1000Res 5. 2016. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.8967.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Irizarry RA, Hobbs B, Collin F, et al.. Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics. 4:249–264. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/4.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, et al.. 2003; Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, et al.. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al.. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Alexa A, Rahnenfuhrer J. topGO: enrichment analysis for gene ontology. R package version 2. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Supek F, Bošnjak M, Škunca N, et al.. REVIGO summarizes and visualizes long lists of gene ontology terms. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21800. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.