Abstract

Background

Mosquito-borne and sexually-transmitted Zika virus infection has become widespread across Central and South America as well as in the Caribbean. Over 30 Zika vaccine candidates are under active development.

Objective

To quantify the impact of Zika vaccine prioritization of females aged 9–49, followed by males aged 9–49, on the incidence of prenatal Zika infections.

Design

We developed a compartmental model of Zika transmission between mosquitoes and humans calibrated to empirical estimates of country-specific mosquito density. Mosquitoes were stratified into susceptible, exposed, or infected classes; humans were stratified into susceptible, exposed, infected, recovered, or vaccinated classes. We further incorporated age-specific rates of fertility, Zika sexual transmission, and country-specific demographics.

Setting

34 countries or territories in the Americas with documented Zika outbreaks.

Target population

Males and females aged 9–49.

Interventions

Age- and gender-targeted immunization using a Zika vaccine with efficacy ranging from 60–90%.

Measurements

Annual prenatal Zika infections

Results

For a base-case vaccine efficacy of 75% and vaccination coverage of 90%, immunizing females aged 9–49, the WHO target population, would reduce the incidence of prenatal infections by at least 94%, depending on the country-specific Zika attack rate. In regions where an outbreak is not expected for at least ten years, vaccination of females aged 15–29 is more efficient than vaccinating women over 30 years.

Limitations

Population-level modeling may not capture all local and neighborhood-level heterogeneity in mosquito abundance or Zika incidence.

Conclusions

A Zika vaccine of moderate to high efficacy has the potential of virtually eliminating prenatal infections through a combination of direct protection and transmission reduction. Efficiency of age-specific Zika vaccination targeting depends on timing of future outbreaks.

Funding

National Institutes of Health

Keywords: Zika, vaccination, Americas, model

Introduction

Since Zika virus, a flavivirus, was introduced into Brazil, it has spread across Central and South America as well as the Caribbean, fueled by the widespread distribution of the Aedes aegypti vector and a susceptible human population (1). Zika infection has been associated with Guillain-Barré Syndrome in adults and with congenital birth defects, including microcephaly, vision-threatening ocular lesions, and central nervous system lesions, as well as fetal demise (2–5). Despite the vector control measures already implemented in many affected countries to combat dengue and yellow fever, Zika continued to spread throughout 2016 and into 2017 (6). Sustained risk reduction of future outbreaks will likely require a combination of vector control and vaccination, as is necessary for the control of yellow fever, another flavivirus (7). Benefiting from existing technologies underlying other flavivirus vaccines, Zika vaccine development has progressed quickly (8), with a viable vaccine expected to be available within several years (9).

The effectiveness of a vaccine in preventing infections depends not only on vaccine efficacy but also on demographic and fertility patterns, local Zika attack rates, and the proportion of the population still susceptible by the time of vaccine availability. Initially, supplies may not be sufficient to cover the entire population. In this case, vaccine supply should be allocated to minimize infections in pregnant women, as perinatal transmission to infants poses the gravest consequences. For this reason, the World Health Organization (WHO) has proposed prioritizing females aged 9–49 followed by males 9–49 for receipt of Zika vaccine (10,11). While vaccinating women in the peak of their fertility years is a clear priority during an outbreak, how to extend vaccination to other women and to men is less clear. This is particularly challenging when there is uncertainty surrounding the likely timing of an outbreak.

Previous models had projected that up to 93.4 million people, including 1.65 million pregnant women, would be infected during the first epidemic wave in the Americas (12). A predictive model has suggested that herd immunity from the first epidemic wave could provide up to a decade of protection against future epidemics (13). Other forecasts have warned that Zika could become sylvatic in parts of the Americas, including Brazil, which would pose a continual reintroduction threat (14). These studies also warned that Zika outbreaks could be potentially exacerbated by cross-interaction with dengue vaccination (15). To evaluate the potential for vaccination to reduce future Zika virus transmission, we developed an age-stratified transmission model applied in each of 34 affected countries/territories. By accounting for country-specific demographics, vector abundance, and potential sexual transmission, we evaluate the effectiveness of Zika vaccination for averting prenatal infections.

Methods

Model overview

We developed a compartmental model of Zika transmission, incorporating both vector-borne and sexual transmission. Susceptible (S) men and women are at risk of becoming asymptomatically exposed (E) to Zika by either vector-borne or sexual routes, from which they transition to become infectious (I). The duration of infectiousness to mosquitoes ranges from 4–7 days (16). After this phase, women recover (R), but men remain infectious to their female partners (J) for an additional 15–180 days (17). Immunological protection is conferred upon recovery or via vaccination (V) and is assumed to be robust, consistent with other flaviviruses (18,19). Each of these clinical and epidemiological states are stratified by age and gender. We take into account age-specific fertility, fundamental to accurately estimating prenatal infection risk, and background age-specific mortality. Mosquito vectors are susceptible to Zika infection (SV), latently infected (EV), or infectious to humans (IV). As our primary outcome, we quantified the burden of a Zika epidemic in terms of the predicted prenatal Zika incidence, measured as infections per 1000 pregnancies over five years. A model flowchart and equations describing the system are provided in the Supplemental Methods (Figure S1).

Transmission

We assumed that both symptomatic and asymptomatic infection are equally infectious. We also assumed frequency-dependent, homogeneous transmission between humans and mosquitoes and no waning of natural immunity, consistent with other flaviviruses (18,19). We modeled sexual transmission by incorporating age- and gender-specific partnership formation rates and mixing matrices, which define the probability of sexual contact between men and women for every age combination (Table S1–2) (20–22). Immune individuals will neither acquire nor transmit infections even if exposed in the future, thereby reducing the overall transmission rate and indirectly protecting susceptible individuals through herd immunity.

Vaccination

We simulated vaccination by calculating the number of individuals who would be vaccinated within each age and gender class (as determined by the planned coverage for that class), and moving these individuals from the susceptible to the vaccinated class prior to the epidemic (Figure S1). We analyzed five vaccination strategies: 1) females ages 9–49, the WHO target product profile; 2) both sexes ages 9–49; 3) single 5-year age cohorts for females between 10 and 49 years; 4) only males 9–49; and 5) scale-up beginning with the 5-year age cohorts in strategy (3) and expanding in 5-year age increments.

1. Vaccination of females ages 9–49

To quantify the impact of vaccination according to the WHO target product profile on prenatal infections (11), we modeled coverage ranging from 0–90% of females aged 9–49.

2. Vaccination of population ages 9–49

As a secondary strategy, we extended coverage to include 0–90% of both males and females aged 9–49.

3. Age-specific vaccination impact

To quantify the impact of age-specific vaccination, we compared vaccination of women in each 5-year age group between 15 and 49 years. For each country, we also tested the correlation between the age-specific fertility rate and the prenatal infections averted per dose, using a simple linear regression.

4. Indirect protection

To quantify the indirect protection conferred by vaccinating the non-childbearing population, we simulated the reduction in prenatal infections achieved by vaccinating only males aged 9–49.

5. Vaccination scale-up

To determine how a limited supply of vaccines should be allocated, we modeled the impact of vaccinating each possible contiguous age group, constrained by age breaks at 5-year intervals (eg ages 10–14, 10–19...10–49, 15–19, 15–24, etc). We then plotted the prenatal infections averted and vaccines administered for each scenario, and determined the age groups for which targeted vaccination dominates – averting at least as many infections as all other strategies employing equal or more vaccines. From this set of dominant strategies we first identified the 5-year age group with the optimal per-dose vaccination impact. We then identified the next three age groups expanding on this optimal age group.

Countries and territories

We specifically modeled Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands as well as 32 countries: Aruba, Barbados, Belize, Bolivia, Bonaire, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Curacao, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Martinique, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Saint Lucia, Saint Martin, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela (23).

Human demographics

For each country, we constructed annual age classes from birth to 100 years among males and females, initialized the population distribution, and parametrized region- and age-specific fertility and mortality rates from United Nations data (Table S3–6).

Mosquito population

For each region, we calibrated the mosquito birth rate to align the model equilibrium mosquito prevalence with empirical estimates (Table S7) and also incorporated seasonal fluctuations in mosquito abundance (24). For countries in which mosquito prevalence indices were unavailable, we substituted estimates from geographically proximate countries. As we did not evaluate vector control, we did not include Aedes aegypti pupal or larval development in the model.

Vaccine efficacy

We assumed a base case vaccine efficacy of 75%, as a mid-point within the recommended minimal and preferred vaccine efficacies of 70% and 80%, respectively, designated in the WHO vaccine target product profile (25).

Parameter calibration

Aedes aegypti mortality and biting rates and Zika-specific parameter estimates were drawn from published literature (Table S7–8). We calibrated the model in a three-step process. First, we fixed the mosquito-to-human Zika transmission rate relative to the human-to-mosquito transmission rate, as estimated in previous models of Zika in the Americas (12,26). Second, we varied the human-to-mosquito transmission rate, and simulated the corresponding Zika epidemics. Based on projections of decade intervals between Zika outbreaks due to herd immunity (13), we used a ten year horizon. Third, we determined the best fit parameter sets for the epidemiological variables using a least-squares approach. For Puerto Rico, we computed the human-to-mosquito transmission rate that produced a 23.5% attack rate, as observed during the Puerto Rico Chikungunya outbreak (27), and computed the mosquito seasonality parameters which best fit the observed Zika epidemic trajectory over the period January 17, 2016 through July 21, 2017 (28,29) (Figure S2). When not otherwise specified, we used the Puerto Rico best-fit attack rate as our base case. Given the uncertainty about attack rates in many countries, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in which we varied the attack rate from 5–50% for each country (Table S9).

Uncertainty Analysis

We fit our model to Puerto Rican incidence data using a Bayesian melding approach. To incorporate empirical parameter uncertainty into model projections, we first used Monte Carlo sampling to create 5,000 input parameter sets from prior distributions for epidemiological, clinical, entomological, demographic, and age-specific fertility derived from empirical ranges for each parameter (Figure S3). We then selected the 1000 parameter sets which, for Puerto Rico, generated a cumulative Zika attack rate that minimized the mean square difference from the observed Chikungunya attack rate of 23.5%. Finally, with each of these 1000 parameter sets, and separately for each country, we compared the impact of vaccination of females 9–49 and vaccination of both females and males 9–49.

Sensitivity Analysis

To quantify how pre-existing immunity acquired during Zika outbreaks prior to the availability of a vaccine impacts vaccine effectiveness, we varied the percentage of the population immune to Zika from 0–50% while varying the attack rate from 5–50% and modeling 0, 50%, and 90% coverage of females 9–49. To evaluate the sensitivity of vaccination scale-up (vaccination scenario 5) to uncertainty in outbreak timing, we considered a scenario where outbreak onset occurs 10 years following vaccination (13). The decrease in vaccination effectiveness under retracted coverage represented in this sensitivity analysis also approximates the effect of reducing vaccine efficacy.

Role of funding source

The funding source had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to publish.

Results

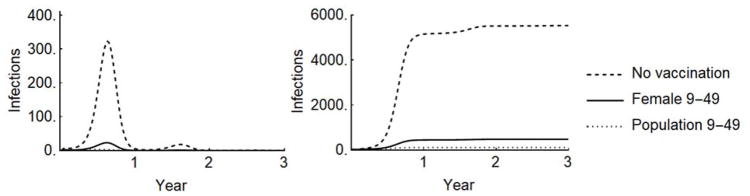

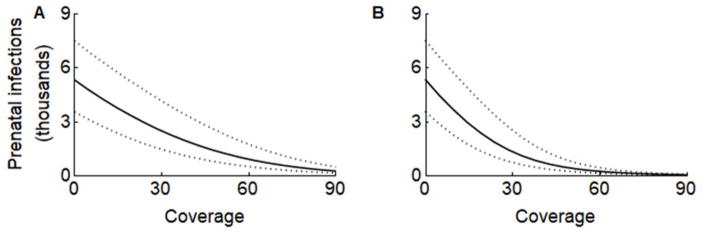

In each of the 34 countries/territories considered, we predicted the impact on prenatal infections of vaccinating females 9–49 years, and then of expanding coverage to include males in this age class, consistent with the WHO target population profile (11). For Puerto Rico, we estimated 5,530 (3,551–7,503) prenatal infections to occur during 2016–2017. With 90% coverage of females 9–49 and a base case vaccine efficacy of 75%, prenatal infections would have been reduced to 358 (188–626), a reduction of 94% (92–95%) (Table 1, Figure 1–2). Extending coverage to include 90% of males aged 9–49 years would have averted all but 76 (52–111) prenatal infections, achieving an overall 99% (98–99%) reduction in prenatal infections.

Table 1.

Pregnancies and prenatal infections for Puerto Rico in the absence of vaccination, and prenatal infections, percentage reduction in prenatal infections, and vaccines administered for four vaccination scenarios: 50% coverage of women 9–49, 50% coverage of the population 9–49, 90% coverage of women 9–49, 90% coverage of the population 9–49. Prenatal infections are calculated over five years, assuming no prior exposure to Zika and an attack rate fit to the epidemic curve as described in the Supplemental Methods. Parentheses indicate 95% credible intervals.

| No vaccinatio n |

Vaccinate 50% of females 9–49 | Vaccinate 50% of population 9–49 | Vaccinate 90% of females 9–49 | Vaccinate 90% of population 9–49 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Pregnanci es |

Prenatal infections |

Prenatal infections |

Reduction | Vaccines | Prenatal infections |

Reduction | Vaccines | Prenatal infections |

Reduction | Vaccines | Prenatal infections |

Reduction | Vaccines |

| Population | 29226 | 5530 (3551–7503) | 1538 (812–2625) | 72% (65–78%) | 640383 | 540 (278–939) | 90% (87–93%) | 1274553 | 358 (188–626) | 94% (92–95%) | 1149986 | 76 (52–111) | 99% (98–99%) | 2277208 |

| Men | 0% (0–0%) | 0 | 0% (0–0%) | 636765 | 0% (0–0%) | 0 | 0% (0–0%) | 1137387 | ||||||

| Women | 29226 | 5530 (3551–7503) | 1538 (812–2625) | 72% (65–78%) | 640383 | 540 (278–939) | 90% (87–93%) | 637788 | 358 (188–626) | 94% (92–95%) | 1149986 | 76 (52–111) | 99% (98–99%) | 1139821 |

| 10–14 | 733 | 140 (89–190) | 39 (20–66) | 72% (65–78%) | 176883 | 14 (7–24) | 90% (87–93%) | 174288 | 9 (5–16) | 94% (92–95%) | 315686 | 2 (1–3) | 99% (98–99%) | 305520 |

| 15–19 | 3605 | 767 (491–1042) | 213 (113–363) | 72% (65–78%) | 66500 | 75 (39–130) | 90% (87–93%) | 66500 | 50 (26–87) | 94% (92–95%) | 119700 | 11 (7–15) | 99% (98–99%) | 119700 |

| 20–24 | 7865 | 1643 (1062–2248) | 457 (243–785) | 72% (65–78%) | 70000 | 160 (83–280) | 90% (87–93%) | 70000 | 107 (56–188) | 94% (92–95%) | 126000 | 23 (15–33) | 99% (98–99%) | 126000 |

| 25–29 | 8545 | 1505 (964–2039) | 419 (220–715) | 72% (65–78%) | 66000 | 147 (75–255) | 90% (87–93%) | 66000 | 97 (51–170) | 94% (92–95%) | 118800 | 21 (14–30) | 99% (98–99%) | 118800 |

| 30–34 | 5818 | 996 (636–1350) | 277 (146–470) | 72% (65–78%) | 66000 | 97 (50–169) | 90% (87–93%) | 66000 | 64 (34–112) | 94% (92–95%) | 118800 | 14 (9–20) | 99% (98–99%) | 118800 |

| 35–39 | 2223 | 403 (256–546) | 112 (59–190) | 72% (65–78%) | 66500 | 39 (20–68) | 90% (87–93%) | 66500 | 26 (14–45) | 94% (92–95%) | 119700 | 6 (4–8) | 99% (98–99%) | 119700 |

| 40–44 | 419 | 74 (47–100) | 20 (11–35) | 72% (65–78%) | 64500 | 7 (4–12) | 90% (87–93%) | 64500 | 5 (2–8) | 94% (92–95%) | 116100 | 1 (1–1) | 99% (98–99%) | 116100 |

| 45–49 | 18 | 3 (2–4) | 1 (0–1) | 72% (65–78%) | 64000 | 0 (0–1) | 90% (87–93%) | 64000 | 0 (0–0) | 94% (92–95%) | 115200 | 0 (0–0) | 99% (98–99%) | 115200 |

An estimated 2.4–4% of prenatal Zika infections result in Zika congenital syndrome (ZCS) (30).

Figure 1.

A) Incidence and B) cumulative prenatal Zika infections in Puerto Rico under three scenarios: 1) no vaccination, 2) vaccination of females age 9–49, and 3) vaccination of the population 9–49. Projections assume the ‘best fit’ attack rate and 90% coverage with a vaccine of 75% efficacy.

Figure 2.

The impact of vaccinating 0–90% of (A) females aged 9–49 or (B) males and females aged 9–49 on prenatal Zika infections with a base case vaccine efficacy of 75%. Dashes indicate the range of the 1000 best-fit model parameter sets. Results are shown for Puerto Rico in the absence of pre-existing immunity.

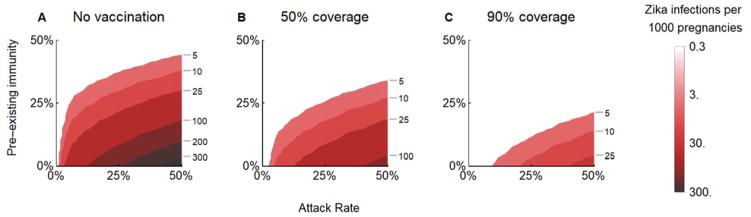

In regions that have already experienced a Zika outbreak, a fraction of the population will have immunity. For example, if 25% of the population in Puerto Rico is already immune to Zika (27), coverage of 50% or 90% of women 9–49 would reduce prenatal infections in a subsequent outbreak to 5 or 2, respectively, per 1000 pregnancies (Figure 3B–C), compared with 192 in an unvaccinated, immunologically naive Puerto Rican population (Figure 3A). The expected impact under reduced vaccine coverage represented in this sensitivity analysis also approximates the impact under reduced vaccine efficacy.

Figure 3.

The 5-year predicted incidence of prenatal Zika infections A) without vaccination, and B) under 50% and C) 90% coverage of women aged 9–49. Attack rates range from 0–50% and pre-existing immunity ranges from 0–50%. Results are shown for a vaccine of 75% efficacy in Puerto Rico; other countries are provided in the Supplementary Results (Figure S4).

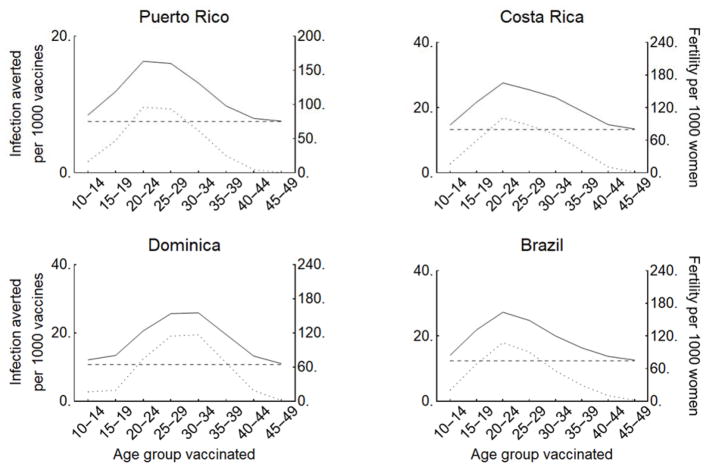

In the event that vaccine supply does not permit coverage across the full age range of the vaccine profile recommended by the WHO, we compared the effectiveness of vaccinating each 5-year age group between the ages of 10 and 49. For all countries and age groups, the estimated number of prenatal infections averted per administered vaccine was significantly (p<0.001) proportional to the country- and age-specific fertility rate (Figure 4, Figure S5, linear regression in Figure S6). For the majority of countries, including Brazil, Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico, vaccinating women aged 20–24 is most effective. For some countries such as Dominica, Guadeloupe, and Suriname, fertility typically peaks later, such that vaccination of females ages 25–34 is predicted to achieve the greatest reduction in prenatal Zika infections.

Figure 4.

The prenatal infections averted per 1000 vaccines (with base case 75% efficacy) administered to each 5-year age group (solid) is proportional to the country- and age-specific fertility rate (dotted), shown here for Puerto Rico, Costa Rica, Dominica, and Brazil under a 25% attack rate in the absence of prior immunity. The per-dose indirect protection against prenatal infections (horizontal dashed) is conferred by vaccinating of women <15, women >50, and males. Results for all countries are provided in the Supplement (Figure S5).

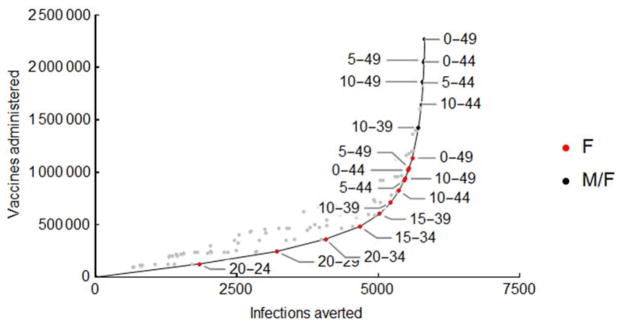

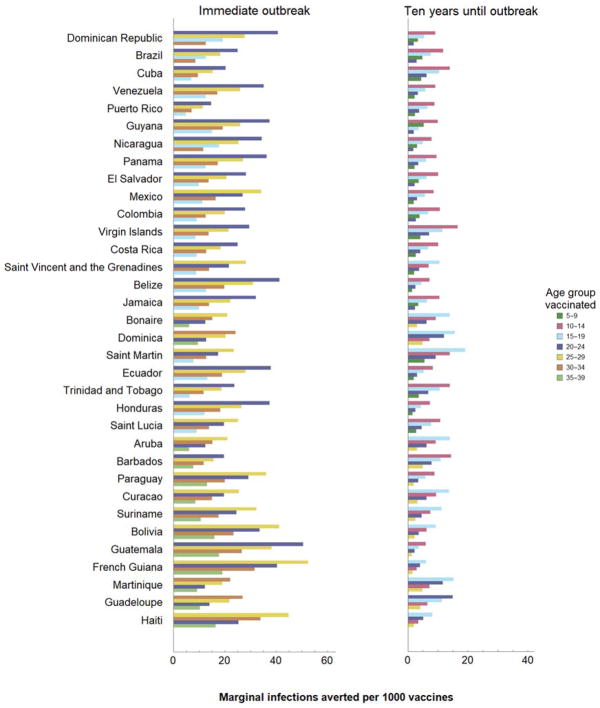

We found that optimal vaccination strategies – those preventing more prenatal infections than any other strategies for the same number of vaccine doses – first target female age groups with highest rates of childbearing and then sequentially expanding to age groups as more vaccines become available (Figure 5). In Puerto Rico, the most efficient strategy is vaccination of women aged 20–24, followed by 20–29, and then successive extension in contiguous age classes, alternating between addition of older and then younger age classes. Only after all females under 59 years have been vaccinated would it become efficient to include males. We found that the four age groups in which vaccination has the greatest impact encompass women aged 20–34 in all 34 regions evaluated (Figure 6). For countries with a higher mean age of childbearing, such as Haiti, optimal vaccination also includes women aged 35–39, while for countries with a lower mean age of childbearing such as the Dominican Republic, optimal vaccination includes women aged 15–19. There is considerably more variability in the magnitude of the decline in marginal benefit provided. For example, in Barbados there is a 37% difference between the marginal number of infections averted by the first and third age groups in impact, while this difference is 56% in Jamaica. If an outbreak is not expected immediately, vaccination in older age groups has less relative impact and the priority shifts to vaccination of younger women (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Prenatal infections averted and vaccines administered under a range of possible combinations of 5-yr age groups targeting females only (F, red dots) or targeting both males and females (M/F, black dots). Dominant strategies, which avert at least as many infections as all other strategies using equal or more vaccines, are indicated in bold with the corresponding age group labeled. Results are for Puerto Rico, assuming a 75% vaccine efficacy.

Figure 6.

The optimal 5-year age group for vaccination and the marginal benefit of further expansions in coverage in 5-year increments, under a 25% attack rate and 75% vaccine efficacy for an outbreak occurring A) immediately after vaccination or B) ten years after vaccination. Countries are ordered by increasing mean childbearing age.

Discussion

Our results indicate that a vaccine against Zika, once available and effectively deployed, may substantially reduce prenatal infections. However the magnitude of this reduction is sensitive to local demographics, transmission potential, and outbreak timing. To maximize per-dose vaccination impact in regions with high probability of an outbreak in the near future, vaccines should generally be provided first to women in their twenties. Then, as more vaccines become available, coverage should be expanded to include all females aged 15–39. Our marginal benefit analysis identified the four 5-year age groups in which vaccination has the greatest impact for each country (Figure 6). A country’s mean age of childbearing is the primary determinant of optimal strategy. Secondarily, demographic structure and sexual contact patterns influence the optimum. The first three priority groups are encompassed within ages 20–34 in all but one region evaluated. The exception, Dominican Republic, has the lowest mean age of childbearing which leads to prioritization of young women 15–19 years before women 30–34 years. The fourth 5-year extension includes women aged 35–39 for 13 of the countries with relatively high mean age of childbearing, such as Haiti. For all other countries, optimal vaccination extends to women aged 15–19. The shift in optimal policy occurs between Saint Lucia and Aruba, at mean childbearing ages of 27.7 and 28.0, respectively, with the exception of Bonaire and Dominica.

Our results underscore the importance of understanding the interplay between human demography and the epidemiological dynamics of Zika when developing control and immunization strategies. In particular, previous models suggest that herd immunity from the current epidemic could delay future outbreaks for up to a decade (13). Our analysis demonstrates that the coverage required to control future epidemics of Zika depends on the age-specific pattern of pre-existing immunity at the time a vaccine becomes available. Consequently, seroprevalence surveys across the affected countries will be critical both to understanding the extent of the current epidemic and for future planning.

It has been estimated that 1.65 (1.45–2.06) million pregnant women in the Americas were infected with Zika during the 2015–2016 outbreak (12), consistent with our estimate of 1.85 prenatal infections. A third analysis predicted 7800 (5900–10300) prenatal infections for Puerto Rico (31) which is higher than our estimate of 5,530 (3,551–7,503) prenatal infections, although the confidence intervals overlap. The discrepancy likely arises from different parameterization of the cumulative attack rates. Specifically, the attack rate in the previous analysis was based on an outbreak of Chikungunya in Puerto Rico. However, data from the entire course of the Zika outbreak has since become available, which we incorporated in conjunction with age-specific fertility to improve accuracy. Based on these estimates, the expected burden of ZCS would be 127–221 and 180–312 cases, for our prediction and the previous estimate respectively, assuming a 2.3–4% risk per completed pregnancy (30). As of October 5, 2017, only 47 cases had been reported (32). Several sources of bias could explain this discrepancy and affect estimated risk of ZCS given prenatal infection (33). For example, bias could arise from underreporting, misdiagnosis and/or disproportionate rates of pregnancy termination among infected women. The risk of birth defects from Zika may also have been elevated by a confounding factor. Previous dengue exposure has been suggested to heighten the risk of complications from Zika (34), and both dengue and Zika were circulating in Brazil (15) during the time period in which ZCS risk was estimated. Given the uncertainties of ZCS risk associated with prenatal infection, we projected incidence and prenatal infections, rather than ZCS cases. The outcome measure of prenatal infections can also be most straightforwardly translated to risks of other ZCS manifestations that may still be identified. The affinity of Zika virus for the central nervous system may lead to more subtle but nonetheless significant cognitive or neurological impairments that are less immediately apparent than manifestations such as microcephaly. Zika infection has been preliminarily linked with neuropsychological and cognitive changes in adolescents (35). Comparably, Chikungunya, also a flavivirus, has been shown to cause neurocognitive impairments among young children as well as prolonged arthralgia and depression (36,37).

There remain uncertainties regarding other clinical and epidemiological aspects of Zika. Lifelong immunity to Zika is generally expected on the basis of immune responses to other flaviviruses (38). However, longitudinal serological studies will be necessary to quantify immunological protection and waning. In vitro studies have suggested cross-reactivity between dengue and Zika antibodies (39), but the effect of this cross-reactivity on clinical outcomes remains unclear (40,41). When country-specific parameters for age-stratified sexual mixing were not available, we used US-derived estimates (Table S2), and when country-specific mosquito indices were not available, we used estimates from geographically proximate countries (Table S7).

As for any model, we made several simplifying assumptions. Our model is based on a compartmental framework, in which the population is divided into distinct classes representing clinical Zika status (Susceptible, Exposed, Infected, Recovered, and Vaccinated) stratified by age and gender. This compartmental framework is appropriate given the data available and the high-level focus on country outcomes. An alternative approach is an agent-based structure which typically tracks individuals in a population. Agent-based modeling is generally most suitable when stochasticity of individual-level human behavior affects epidemiological outcomes, such as during disease emergence and eradication, and when individual-level data is available for parameterization. While our results do not capture local heterogeneity in Zika infection incidence, our model does highlight the robustness of targeted Zika vaccination strategies across affected countries.

The Aedes mosquitoes that transmit Zika have long been the target of vector control measures in affected regions. We therefore assumed that the effect of vector control on mosquito density would remain constant throughout the time period of projections. The appropriate vaccine strategy to deploy under any improvements in vector control, such as more aggressive efforts or the introduction of genetically-modified Wolbachia (42,43), can be determined by considering the lower attack rate scenarios in our sensitivity analyses. Likewise, long-term shifts in mosquito prevalence, as might be driven by climate change, could be represented by varying the attack rates (44,45).

Significant challenges must be addressed in the development and implementation of a Zika vaccine. The drop in Zika incidence makes traditional clinical trial methodology infeasible. Even during an epidemic, the speed of Zika outbreaks at the local level necessitates innovative approaches for trial site selection, possibly including simultaneous pre-approval and surveillance for a number of trial sites. At the implementation stage, cost-effectiveness and affordability are key considerations in the resource-constrained settings at highest risk of Zika outbreaks. Further research is required to elucidate regional patterns of age-stratified Zika seroprevalence, which could affect the cost-effectiveness of Zika vaccination in different countries.

Despite these challenges, our results demonstrate the substantial impact that Zika vaccination programs could have in mitigating and preventing future outbreaks. Through a combination of direct protection and indirect transmission reduction, virtual elimination is achievable even with imperfect vaccine efficacy and coverage. Our results also highlight the importance of targeted Zika vaccination. Given the temporal uncertainty of Zika resurgences, it is imperative that vaccine development and testing continue to be pursued, ensuring that such a Zika vaccine is available as soon as possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (U01 GM087719 and U01 GM105627). MCF was also supported by National Institutes of Health grant T32 AI007524. Simulations were run on the Yale University Biomedical High Performance Computing Center, which is supported by NIH grants RR19895 and RR029676-01. The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Author Contributions. DPD, MCF, MLNB, and APG designed the study; DPD and ASP collected the data; DPD developed the model and analyzed the data; DPD, MCF, MLNB, and APG interpreted the data; DPD, MCF, MLNB, ASP, NLM, and APG wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest statements. MCF has received consulting fees from Merck & Co and from Sanofi Pasteur. DPD, MLNB, ASP, NLM, and APG declare no conflicts.

Ethics committee approval. Not applicable; the described research used only publicly available, peer reviewed data sources.

Reproducible Research Statement. Study protocol: not applicable. Code and data used to generate results are available at https://github.com/davidpdurham/ZikaVaccination

References

- 1.Faria NR, Azevedo R do S da S, Kraemer MUG, Souza R, Cunha MS, Hill SC, et al. Zika virus in the Americas: Early epidemiological and genetic findings. Science. 2016 Mar 24;352(6283):345–9. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cauchemez S, Besnard M, Bompard P, Dub T, Guillemette-Artur P, Eyrolle-Guignot D, et al. Association between Zika virus and microcephaly in French Polynesia, 2013–15: a retrospective study. Lancet. 387(10033):2125–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00651-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cao-Lormeau V-M, Blake A, Mons S, Lastère S, Roche C, Vanhomwegen J, et al. Guillain-Barré Syndrome outbreak associated with Zika virus infection in French Polynesia: a case-control study. Lancet. 2016 Feb 29;387(10027):1531–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00562-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Paula Freitas B, de Oliveira Dias JR, Prazeres J, Sacramento GA, Ko AI, Maia M, et al. Ocular Findings in Infants With Microcephaly Associated With Presumed Zika Virus Congenital Infection in Salvador, Brazil. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2016 Feb 9;134(5):529–35. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sarno M, Sacramento GA, Khouri R, do Rosário MS, Costa F, Archanjo G, et al. Zika Virus Infection and Stillbirths: A Case of Hydrops Fetalis, Hydranencephaly and Fetal Demise. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Feb;10(2):e0004517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikejezie J, Shapiro CN, Kim J, Chiu M, Almiron M, Ugarte C, et al. Zika Virus Transmission - Region of the Americas, May 15, 2015–December 15, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Mar 31;66(12):329–34. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6612a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubler DJ. The changing epidemiology of yellow fever and dengue, 1900 to 2003: full circle? Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004 Sep;27(5):319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon J. Vaccines Protect Fetus From Zika. JAMA. 2017 Aug 22;318(8):689. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barouch DH, Thomas SJ, Michael NL. Prospects for a Zika Virus Vaccine. Immunity. 2017 Feb 21;46(2):176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas SJ, L’Azou M, Barrett ADT, Jackson NAC. Fast-Track Zika Vaccine Development - Is It Possible? N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 29;375(13):1212–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1609300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vannice KS, Giersing BK, Kaslow DC, Griffiths E, Meyer H, Barrett A, et al. Meeting Report: WHO consultation on considerations for regulatory expectations of Zika virus vaccines for use during an emergency. Vaccine [Internet] 2016 Dec 1; doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.034. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Perkins TA, Siraj AS, Ruktanonchai CW, Kraemer MUG, Tatem AJ. Model-based projections of Zika virus infections in childbearing women in the Americas. Nature Microbiology. 2016 Jul 25;1:16126. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson NM, Cucunubá ZM, Dorigatti I, Nedjati-Gilani GL, Donnelly CA, Basáñez M-G, et al. EPIDEMIOLOGY. Countering the Zika epidemic in Latin America. Science. 2016 Jul 22;353(6297):353–4. doi: 10.1126/science.aag0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Althouse BM, Vasilakis N, Sall AA, Diallo M, Weaver SC, Hanley KA. Potential for Zika Virus to Establish a Sylvatic Transmission Cycle in the Americas. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Dec;10(12):e0005055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang B, Xiao Y, Wu J. Implication of vaccination against dengue for Zika outbreak. Sci Rep. 2016 Oct 24;6:35623. doi: 10.1038/srep35623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucharski AJ, Funk S, Eggo RM, Mallet H-P, John Edmunds W, Nilles EJ. Transmission Dynamics of Zika Virus in Island Populations: A Modelling Analysis of the 2013–14 French Polynesia Outbreak. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 May 17;10(5):e0004726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell K, Hills SL, Oster AM, Porse CC, Danyluk G, Cone M, et al. Male-to-Female Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus — United States, January–April 2016. Clin Infect Dis. 2016 Oct 19;64(2):211–3. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fagbami AH. Zika virus infections in Nigeria: virological and seroepidemiological investigations in Oyo State. J Hyg. 1979 Oct;83(2):213–9. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400025997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sawyer WA. The Persistence of Yellow Fever Immunity. Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1931;5(6):413–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durham DP, Ndeffo-Mbah ML, Skrip LA, Jones FK, Bauch CT, Galvani AP. National- and state-level impact and cost-effectiveness of nonavalent HPV vaccination in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 May 3;113(18):5107–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515528113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juarez F, Martín TC. Partnership Dynamics and Sexual Health Risks Among Male Adolescents in the Favelas of Recife, Brazil. IFPP. 2006 Jun;32(02):62–70. doi: 10.1363/3206206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker E, Singh S, Hodges Z, Patel D, et al. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective. Lancet. 2006 Nov 11;368(9548):1706–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwizwai R. Infection disease surveillance update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 Feb;16(2):157. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luz PM, Vanni T, Medlock J, Paltiel AD, Galvani AP. Dengue vector control strategies in an urban setting: an economic modelling assessment. Dengue vector control strategies in an urban setti. 2011;377(9778):1673–80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60246-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO/UNICEF. Zika Virus (ZIKV) Vaccine Target Product Profile (TPP): Vaccine to protect against congenital Zika syndrome for use during an emergency [Internet] [cited 2017 Sep 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/research/development/WHO_UNICEF_Zikavac_TPP_Feb2017.pdf.

- 26.Lessler JT, Ott CT, Carcelen AC, Konikoff JM, Williamson J, Bi Q, et al. Times to key events in the course of Zika infection and their implications: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Bull World Health Organ [Internet] 2016:1. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.174540. Available from: http://www.who.int/entity/bulletin/online_first/BLT.16.174540.pdf?ua=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Simmons G, Brès V, Lu K, Liss NM, Brambilla DJ, Ryff KR, et al. High Incidence of Chikungunya Virus and Frequency of Viremic Blood Donations during Epidemic, Puerto Rico, USA, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Jul 15;22(7):1221–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.160116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chevalier MS, Biggerstaff BJ, Basavaraju SV, Ocfemia MCB, Alsina JO, Climent-Peris C, et al. Use of Blood Donor Screening Data to Estimate Zika Virus Incidence, Puerto Rico, April–August 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 May;23(5):790–5. doi: 10.3201/eid2305.161873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez DM, Johansson MA, Mier-y-Teran-Romero L, Yo JD, Doone BN, Anand A, et al. Data repository of publicly available Zika data [Internet] Zenodo. 2017 Available from: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.584136; https://github.com/cdcepi/zika/tree/2017.05.29.

- 30.Honein MA, Dawson AL, Petersen EE, Jones AM, Lee EH, Yazdy MM, et al. Birth Defects Among Fetuses and Infants of US Women With Evidence of Possible Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy. JAMA. 2017 Jan 3;317(1):59–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellington SR, Devine O, Bertolli J, Martinez Quiñones A, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Perez-Padilla J, et al. Estimating the Number of Pregnant Women Infected With Zika Virus and Expected Infants With Microcephaly Following the Zika Virus Outbreak in Puerto Rico, 2016. JAMA Pediatr. 2016 Oct 1;170(10):940–5. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. Zika suspected and confirmed cases reported by countries and territories in the Americas Cumulative cases, 2015–2017 [Internet] 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 7]. Available from: http://www2.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_docman&task=doc_view&Itemid=270&gid=39281&lang=es.

- 33.de Oliveira WK, Carmo EH, Henriques CM, Coelho G, Vazquez E, Cortez-Escalante J, et al. Zika Virus Infection and Associated Neurologic Disorders in Brazil. N Engl J Med. 2017 Apr 20;376(16):1591–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1608612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Wongwiwat W, Rouvinski A, Barba-Spaeth G, Duangchinda T, et al. Dengue virus sero-cross-reactivity drives antibody-dependent enhancement of infection with zika virus. Nat Immunol. 2016 Sep;17(9):1102–8. doi: 10.1038/ni.3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zucker J, Neu N, Chiriboga CA, Hinton VJ, Leonardo M, Sheikh A, et al. Zika Virus-Associated Cognitive Impairment in Adolescent, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Jun;23(6):1047–8. doi: 10.3201/eid2306.162029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schilte C, Staikowsky F, Staikovsky F, Couderc T, Madec Y, Carpentier F, et al. Chikungunya virus-associated long-term arthralgia: a 36-month prospective longitudinal study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013 Mar 21;7(3):e2137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gérardin P, Sampériz S, Ramful D, Boumahni B, Bintner M, Alessandri J-L, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of children exposed to perinatal mother-to-child Chikungunya virus infection: the CHIMERE cohort study on Reunion Island. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014 Jul;8(7):e2996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baud D, Gubler DJ, Schaub B, Lanteri MC, Musso D. An update on Zika virus infection. Lancet. 2017 Jun 21;390(10107):2099–109. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31450-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrison SC. Immunogenic cross-talk between dengue and Zika viruses. Nat Immunol. 2016 Aug 19;17(9):1010–2. doi: 10.1038/ni.3539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawiecki AB, Christofferson RC. Zika Virus–Induced Antibody Response Enhances Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Replication In Vitro. J Infect Dis. 2016 Nov 1;214(9):1357–60. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castanha PMS, Nascimento EJM, Cynthia B, Cordeiro MT, de Carvalho OV, de Mendonça LR, et al. Dengue virus (DENV)-specific antibodies enhance Brazilian Zika virus (ZIKV) infection. J Infect Dis. 2016 Dec 29;215(5):781–5. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yakob L, Walker T. Zika virus outbreak in the Americas: the need for novel mosquito control methods. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 Feb 1;4(3):e148–9. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dutra HLC, Rocha MN, Dias FBS, Mansur SB, Caragata EP, Moreira LA. Wolbachia Blocks Currently Circulating Zika Virus Isolates in Brazilian Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes. Cell Host Microbe. 2016 May 3;19(6):771–4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gagnon AS, Smoyer-Tomic KE, Bush ABG. The El Niño southern oscillation and malaria epidemics in South America. Int J Biometeorol. 2002 May;46(2):81–9. doi: 10.1007/s00484-001-0119-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caminade C, Turner J, Metelmann S, Hesson JC, Blagrove MSC, Solomon T, et al. Global risk model for vector-borne transmission of Zika virus reveals the role of El Niño 2015. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Jan 3;114(1):119–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614303114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.