Abstract

Background

Low muscle mass and strength are highly prevalent in inpatients. It is acknowledged that low muscle mass and strength are associated with falls in community-dwelling older adults, but it is unknown if these muscle measures are also associated with falls in a population of older inpatients. This study aimed to investigate the association between muscle measures and pre- and post-hospitalization falls in older inpatients.

Methods

An inception cohort of patients aged 70 years and older, admitted to an academic teaching hospital, was included in this study. Muscle mass and hand grip strength were measured at admission using bioelectrical impedance analysis and handheld dynamometry. Pre-hospitalization falls were dichotomized as having had at least one fall in the six months prior to admission. Post-hospitalization falls were dichotomized as having had at least one fall during the three months after discharge. Associations were analysed with logistic regression analysis.

Results

The study cohort comprised 378 inpatients (mean age, SD: 79.7, 6.4 years). Fifty per cent of female and 41% of male patients reported at least one fall prior to hospitalization. Post-hospitalization, 18% of female and 23% of male patients reported at least one fall. Lower muscle mass was associated with post-hospitalization falls, and lower hand grip strength was associated with both pre- and post-hospitalization falls in male, but not in female, patients.

Conclusions

These findings confirm the likely involvement of muscle mass and strength in the occurrence of pre- and post-hospitalization falls in a population of older inpatients, but only in males.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-018-0812-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Accidental Falls, Aged, Hospitalization, Muscle strength, Sarcopenia

Background

Sarcopenia, a combination of low muscle mass and low muscle strength [1], is prevalent in up to 25% of older inpatients at admission [2]. During hospitalization, low muscle mass and low muscle strength are associated with a higher incidence of adverse clinical events, malnutrition, a longer length of hospital stay, incomplete functional recovery and in-hospital mortality [2–6]. After discharge, low muscle mass and strength at admission have been associated with low cognitive function, depressive symptoms, poor quality of life, nursing home institutionalization, hospital readmission and mortality [2, 4, 5, 7–10].

In community-dwelling older adults, low muscle mass and low muscle strength, indicated by low leg extension force as well as low hand grip strength (HGS), have been associated with a higher risk of falls [11–16]. Intervention studies have shown that improving muscle mass and strength in older community-dwelling adults reduces the risk of falls [17, 18]. However, currently there is no evidence demonstrating that strength training as mono-therapy reduces the risk or rate of falling. In older patients with a previous hospitalization, a fall rate of 15% within the first month after discharge was reported [19]. Risk factors of post-discharge falls in older patients include male gender, depressed mood, reliance on an assistive device, decline in mobility during hospitalization and cognitive impairment at discharge [20, 21]. Low muscle mass and strength may be the underlying cause of most of these risk factors and should therefore conceptually be associated with falls.

We aimed to investigate whether muscle mass and strength are associated with pre- and post-hospitalization falls in older inpatients.

Methods

Study design

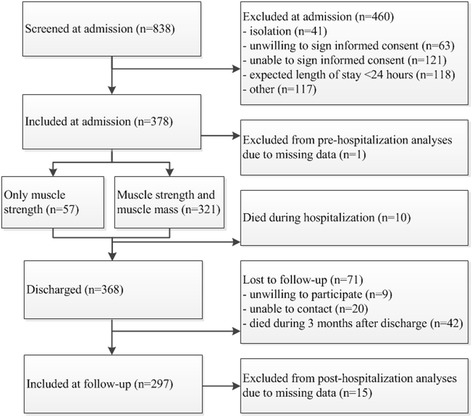

The Evaluation of Muscle parameters in a Prospective cohort of Older patients at clinical Wards Exploring Relations with bed rest and malnutrition (EMPOWER) study was a prospective, inception cohort study conducted from April until December 2015 at the VU university medical center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. An extended description of the protocol is published elsewhere [22]. In short, patients aged 70 years and older, either electively or acutely admitted to the internal medicine, acute admission, trauma or orthopaedic ward, and who were hospitalized for > 24 h were included in the study. Patients were assessed within 48 h after admission (n = 378) and three months after discharge by a telephone interview (n = 297) (see Fig. 1). Main reason for loss to follow-up was death in the three months following hospitalization (n = 42). The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center and all included patients signed written informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart on the number of patients included for each assessment

Clinical and demographic measures

Baseline characteristics were obtained from medical charts augmented with a bedside interview. Measures included: use of walking aid (yes/no), living independently (yes/no), weight (in kilograms, kg, using a weighting chair), height (in centimetres, cm, using knee height as proposed by the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam, LASA formula [Male: 74,48 + (2,03 * knee height) - (0,15 * age), female: 68,74 + (2,07 * knee height) - (0,16 * age)]), current smoking (yes/no), current alcohol use (yes/no), type of admission (elective/acute), treating specialism (surgical including vascular and orthopaedic surgery/non-surgical including internal medicine, cardiology and neurology), number of chronic medications (polypharmacy defined as > 4 chronic medications), number of chronic diseases (comorbidities defined as > 1 chronic disease), disability (Katz-Activities of Daily Living, ADL [23]), pain (Numeric Rating Scale, NRS [24]), mobility (Functional Ambulatory Categories, FAC [25]), cognition (six item Cognitive Impairment Test, 6-CIT [26]), malnutrition (Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire, SNAQ [27]).

Muscle measures

At admission, patients were assessed for muscle mass and muscle strength. Muscle mass was measured using direct segmental multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis (DSM-BIA, InBody S10, Biospace Co., Ltd., Seoul) resulting in the following parameters: 1) absolute skeletal muscle mass (SMM); 2) skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), calculated as [SMM/height2] [1]; and 3) relative muscle mass (RMM), calculated as [SMM/weight] [28]. DSM-BIA could not be performed in patients with a pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, plasters or bandages that could not be removed from the positioning place of the electrodes, or amputated arm and/or leg (n = 57, see Fig. 1).

HGS was measured using a hydraulic handheld dynamometer (Jamar, Sammons Preston Rolyan, IL, USA) sitting upright in a chair without support of the elbows. In case the patient was unable to get out of bed, HGS was measured with the bed in an angle of 30 degrees and the elbows unsupported. Repeated measurements were performed in the same position with two attempts per hand [29]. The maximum score out of four attempts was used for analysis.

Pre- and post-hospitalization falls

A fall was defined as an event that resulted in “unintentionally coming to the ground or some lower level and other than as a consequence of sustaining a violent blow, loss of consciousness, sudden onset of paralysis as in stroke or an epileptic seizure” [30]. Pre-hospitalization falls were retrospectively assessed at admission with a questionnaire and dichotomized as at least one fall within six months before admission [31]. Post-hospitalization falls were prospectively assessed three months after discharge by a telephone interview and defined as at least one fall within the three months after discharge.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, median and interquartile range (IQR) for skewed data and numbers and % for categorical data. Due to missing data, respectively one patient and 15 patients were excluded from the analyses on pre- and post-hospitalization falls.

All analyses were stratified for sex. The associations of muscle measures with pre-hospitalization and with post-hospitalization falls were investigated using logistic regression analyses. We first performed unadjusted analyses and subsequently adjusted for age, comorbidities, and height (only for HGS) or weight (only for RMM) in multivariable models. Both age and number of comorbidities were selected as covariates because of their association with muscle measures and fall risk [16, 32]. We added height to the model of HGS [33] and body weight to the model of RMM [34] as they effect these variables next to the risk of falls [35, 36]. To be able to compare the effect sizes of the different muscle measures, we performed post-hoc analyses and repeated the adjusted models using sex specific z-scores. Results were presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. Significance level was set at α = 0.05. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0. Armonk, NY, IBM Corp) was used for all analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the patients at baseline and at follow-up are shown in Table 1. Mean age (SD) was 79.7 (6.4) years of the entire patient cohort, 49% were female and 91% were living independently before hospitalization. In the six months before hospitalization, 50% of female and 41% of male patients experienced a fall. In the three months after discharge, 18% of female and 23% of male patients experienced a fall.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at admission and three months follow-up, stratified by sex

| Characteristics | Included at baseline (n = 378) | Included at follow-up (n = 297) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ♂ (n = 192) |

♀ (n = 186) |

♂ (n = 141) |

♀ (n = 156) |

|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 79.1 (6.3) | 80.3 (6.5) | 78.1 (5.5) | 80.3 (6.5) |

| Use of walking aid | 92 (48.2) | 108 (58.7) | 64 (45.7) | 91 (59.1) |

| Living independently | 178 (92.7) | 161 (89.0) | 132 (93.6) | 135 (88.2) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 77.3 (15.4) | 68.3 (16.7) | 79.8 (15.2) | 68.9 (17.3) |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 175 (6.7) | 161 (5.7) | 176 (6.4) | 161 (5.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 25.2 (4.5) | 26.3 (6.3) | 25.9 (4.4) | 26.5 (6.5) |

| Current smoking | 27 (14.5) | 13 (7.1) | 19 (13.8) | 8 (5.2) |

| Alcohol use | 91 (48.9) | 55 (30.4) | 80 (58.0) | 45 (29.6) |

| Elective admission | 25 (13.0) | 33 (17.7) | 23 (16.3) | 29 (18.6) |

| Surgical specialism | 76 (39.6) | 95 (51.1) | 65 (46.1) | 83 (53.2) |

| Polypharmacya | 127 (66.1) | 107 (57.5) | 88 (62.4) | 91 (58.3) |

| Comorbiditiesb | 170 (88.5) | 163 (88.6) | 120 (85.1) | 137 (89.0) |

| ADL-score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 0 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) |

| NRS-score, median (IQR) | 1 (0–4) | 3 (0–6) | 1 (0–4) | 3 (0–6) |

| FAC-score, median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (0–4) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (0–5) |

| 6-CIT-score, median (IQR) | 4 (0–8) | 4 (1–10) | 4 (0–8) | 4 (0–10) |

| SNAQ-score, median (IQR) | 0 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) |

| LOS, days, median (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–9) | 5 (2–7) | 5 (3–9) |

| Pre-hospitalization fallsc | 79 (41.1) | 93 (50.3) | 57 (40.4) | 79 (51.0) |

| Post-hospitalization fallsd | 32 (23.4) | 26 (17.9) | ||

All variables are presented as n (%), unless otherwise indicated

BMI Body Mass Index. SNAQ Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire. ADL KATZ Activities of Daily Living. 6-CIT 6-item Cognitive Impairment Test. NRS Numerical Rating Scale for pain. FAC Functional Ambulation Categories. LOS Length of Stay. SD Standard Deviation. IQR Interquartile Range aNumber of medications > 4. bNumber of comorbidities > 1. cPre-hospitalization falls: Patients who reported at least one fall within 6 months before admission. dPost-hospitalization falls (♂n = 137, ♀n = 145): Patients who reported at least one fall within 3 months after discharge

Table 2 shows the associations of muscle mass and HGS with pre-hospitalization falls. In male patients, lower HGS (OR, 95% CI, 0.94, 0.90–0.98) was associated with pre-hospitalization falls. For lower SMM and SMI a trend was observed (ORs, 95% CI, SMM: 0.94, 0.88–1.01 and SMI: 0.80, 0.64–1.01), but not for RMM (OR, 95% CI, 0.97, 0.90–1.04). In female patients, lower HGS was associated with pre-hospitalization falls, but this did not reach statistical significance (OR, 95% CI, 0.94, 0.88–1.00). No association was found between muscle mass and pre-hospitalization falls in female patients (ORs, 95% CI, SMM: 1.04, 0.95–1.13, SMI: 1.10, 0.85–1.42 and RMM: 0.99, 0.92–1.07).

Table 2.

Muscle parameters at admission and pre- and post-hospitalization falls, stratified by sex

| N | Falls, Mean (SD) | No falls, Mean (SD) | Crude | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

| Pre-hospitalization fallsa | ||||||||

| HGS, kg | ♂ | 192 | 23.5 (10.8) | 27.9 (8.82) | 0.95 (0.92, 0.98) | 0.003 | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 0.003 |

| ♀ | 185 | 14.3 (5.96) | 15.6 (5.25) | 0.96 (0.91, 1.01) | 0.128 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.062 | |

| SMM, kg | ♂ | 158 | 28.9 (5.22) | 30.4 (5.84) | 0.95 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.104 | 0.94 (0.88, 1.01) | 0.074 |

| ♀ | 162 | 22.8 (4.01) | 22.3 (3.50) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.13) | 0.352 | 1.04 (0.95, 1.13) | 0.393 | |

| SMI, kg/m2 | ♂ | 158 | 9.45 (1.49) | 9.88 (1.45) | 0.82 (0.65, 1.02) | 0.076 | 0.80 (0.64, 1.01) | 0.063 |

| ♀ | 162 | 8.73 (1.32) | 8.51 (1.17) | 1.11 (0.87, 1.43) | 0.399 | 1.10 (0.85, 1.42) | 0.470 | |

| RMM, % | ♂ | 158 | 38.9 (5.56) | 39.2 (4.60) | 0.99 (0.93, 1.06) | 0.748 | 0.97 (0.90, 1.04) | 0.383 |

| ♀ | 162 | 33.2 (6.04) | 34.3 (5.26) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.02) | 0.226 | 0.99 (0.92, 1.07) | 0.856 | |

| Post-hospitalization fallsb | ||||||||

| HGS, kg | ♂ | 137 | 23.4 (9.16) | 29.6 (9.90) | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98) | 0.004 | 0.93 (0.88, 0.99) | 0.020 |

| ♀ | 145 | 14.7 (5.43) | 15.1 (5.56) | 0.99 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.746 | 1.02 (0.92, 1.12) | 0.771 | |

| SMM, kg | ♂ | 116 | 27.3 (3.71) | 31.8 (5.61) | 0.81 (0.71, 0.91) | 0.001 | 0.80 (0.71, 0.92) | 0.001 |

| ♀ | 125 | 22.1 (4.36) | 23.0 (3.75) | 0.94 (0.83, 1.07) | 0.320 | 0.92 (0.81, 1.06) | 0.243 | |

| SMI, kg/m2 | ♂ | 116 | 9.08 (1.15) | 10.2 (1.41) | 0.53 (0.36, 0.77) | 0.001 | 0.50 (0.33, 0.76) | 0.001 |

| ♀ | 125 | 8.39 (1.55) | 8.80 (1.16) | 0.75 (0.50, 1.13) | 0.166 | 0.73 (0.48, 1.10) | 0.132 | |

| RMM, % | ♂ | 116 | 38.2 (4.70) | 39.4 (5.32) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.04) | 0.309 | 0.85 (0.75, 0.96) | 0.009 |

| ♀ | 125 | 32.9 (6.51) | 33.7 (5.04) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.06) | 0.533 | 0.95 (0.85, 1.07) | 0.435 | |

CI Confidence Interval. HGS Hand Grip Strength. OR Odds Ratio. SD Standard Deviation. SMI Skeletal Muscle Index. SMM Skeletal Muscle Mass. RMM Relative Muscle Mass. Adjusted model adjusted for age, comorbidities, HGS for height and RMM for weight. Statistically significant results are presented in bold. aPre-hospitalization falls, yes: N = 172, no: N = 205. bPost-hospitalization falls, yes: N = 58, no: N = 224

The associations of muscle mass and HGS with post-hospitalization falls are shown in Table 2. In male patients, lower HGS, SMM and SMI (ORs,95% CI, respectively: 0.93, 0.88–0.99, 0.80, 0.71–0.92 and 0.50, 0.33–0.76) were associated with post-hospitalization falls. Lower RMM was associated with falls after adjustment for confounders (OR, 95% CI, 0.85, 0.75–0.96). No association were found between muscle measures and post-hospitalization falls in female patients (ORs, 95% CI, HGS: 1.02, 0.92–1.12, SMM: 0.92, 0.81–1.06, SMI: 0.73, 0.48–1.10 and RMM: 0.95, 0.85–1.07).

The results of the post-hoc analyses with sex specific z-scores for comparison of the effect sizes between muscle measures are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. Taking the significant associations into account, HGS had the largest effect size for pre- hospitalization falls, and SMM had the largest effect size for post-hospitalization falls in male patients.

Discussion

In older male patients, lower absolute and relative muscle mass were associated with post-hospitalization falls, and lower HGS was associated with pre- and post-hospitalization falls. In female patients, no significant associations between muscle measures and pre- and post-hospitalization falls were found.

We found that absolute muscle mass was not associated with pre-hospitalization falls, but was associated with post-hospitalization falls, in male inpatients. The difference between pre- and post-hospitalization falls in the association with muscle mass is rather small, which might be due to differences in recall bias pre- and post-hospitalization. Our results are in line with a previous study of a large sample of community-dwelling older adults, in which people who had fallen in the previous year had significantly lower absolute muscle mass [16]. Furthermore, we found that RMM was significantly associated with post-hospitalization falls after adjustment for weight. This finding is in concordance with a previous study of community-dwelling older males, in which RMM was associated with risk of falls, after adjustment for fat mass [15]. SMM, SMI and RMM show different effect sizes, because of different scaling of the measures. Yet, comparing the effect sizes with z-scores indicates that all three measures are valuable determinants of post-hospitalization falls. Studies in older community-dwelling adults also showed an association of falls with upper and lower extremity weakness [13, 17]. Experimental studies with induced gait perturbations showed significantly lower limb muscle strength and lower HGS in fallers compared with non-fallers [14]. In line with our results, sarcopenia – defined using various definitions including absolute or relative muscle mass, isolated or combined with HGS and gait speed – was found to be associated with falls in community-dwelling older adults [11, 12].

In contrast to their male counterparts, female inpatients had relatively lower HGS and lower population variation. The HGS value of female inpatients is comparable with adults of the general population above 89 years of age [37] or those who are chronically ill [32]. The relatively lower strength and lower variation may account for the non-significant relation with either pre- or post-hospitalization. The contribution of other risk factors for falls, such as active disease, multi-morbidity and polypharmacy, may also be sex specific [38, 39]. None of the previous mentioned studies in community-dwelling adults reported their results separately for females, complicating the comparison to our results.

Clinical implications and future research

Muscle strength and power are essential in the maintenance of balance. Also, a quick recovery during loss of balance, coupled with muscle strength, seem to exhibit a superior role over muscle mass in screening and intervening in fall prevention [17, 40]. However, an independent causality between muscle weakness and falls in older people has yet to be proven [41, 42]. The measured effect sizes of HGS and muscle mass are clinically meaningful, since an increase of one kg of muscle mass or strength leads to a large decrease in the odds of falls. These findings underline the potential for beneficial outcomes of interventions directed at increasing muscle strength and mass. Identification at an early stage in clinical practice of male inpatients at risk of falls, by use of relatively simple measures such as muscle mass and HGS, could allow for development of targeted interventions and potentially reduce healthcare costs in the long term. Despite the lack of significant associations with pre- and post-hospitalization falls in female patients, screening of female patients with low muscle mass and muscle strength at an early stage during hospitalization is important to identify females at risk of other detrimental outcomes [2].

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study investigating the association between muscle measures and pre- and post-hospitalization falls in older inpatients. Selection bias was minimized through the study design as an inception cohort. An important limitation was the self-reporting of falls by patients, both in the questionnaire on admission and in the telephone interview three months after discharge. Self-reporting may be prone to recall bias, but this was unavoidable due to the study cohort design including predominantly acutely admitted patients. We did not record the number of falls per patient, since this is likely to be affected by recall bias. Furthermore, the dropout of patients between discharge from hospital and the telephone interview may have induced a selection bias, due to the death of more than half of the participants in this frail sample population.

Conclusions

In this prospective, inception cohort study of inpatients aged 70 years and older, we found an association between post-hospitalization falls and muscle mass, and between pre- and post-hospitalization falls and HGS in male patients. No such association was found among female patients. Further research is needed to provide evidence on the causality of muscle mass and muscle strength in pre- and post-hospitalization falls in inpatients, for the development of inpatient interventions.

Additional file

Table S1. Z-scores of muscle parameters at admission and pre- and post-hospitalization falls, stratified by sex. Adjusted models of the standardized measures of HGS, SMM, SMI and RMM stratified for sex by z-scores. (DOCX 17 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank V. D. Pierik, S. T. Numans, A. Verburg and H. M. D. Nagtzaam for their assistance during the inclusion of patients and R. C. Kruizinga and Monique Slee-Valentijn for the help in designing the protocol.

Funding

This study was supported by the seventh framework program MYOAGE (HEALTH-2007-2.4.5-10); European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (No 689238 and No 675003); and Nutricia Research, Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition, The Netherlands. These funding sources were not involved in the study design, data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of the data, or in writing of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 6-item CIT

6-item Cognitive impairment test

- CI

Confidence intervals

- DSM-BIA

Direct segmental multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis

- EMPOWER

The evaluation of muscle parameters in a prospective cohort of older patients at clinical Wards Exploring Relations with bed rest and malnutrition

- FAC

Functional ambulatory categories

- HGS

Hand grip strength

- IQR

Interquartile range

- KATZ-ADL

Katz index of independence in activities of daily living

- LASA

Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam

- NRS

Numeric rating scale

- OR

Odds ratios

- RMM

Relative muscle mass

- SD

Standard deviation

- SMI

Skeletal muscle mass index

- SMM

Skeletal muscle mass

- SNAQ

Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire

- SPSS

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

Authors’ contributions

Conceived the study protocol and design: JMVA, MP, NHJ, KS, SV, CGMM and ABM. Collected data: JMVA and KS. Analyzed the data: JMVA and NHJ. Contributed to analyses: JMVA, MP, NHJ, KS, SV, CGMM and ABM. Drafted the article: JMVA. Critically revised the article: JMVA, MP, NHJ, KS, SV, CGMM and ABM. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. All included patients signed written informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12877-018-0812-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Jeanine M. Van Ancum, Email: j.m.van.ancum@vu.nl

Mirjam Pijnappels, Email: m.pijnappels@vu.nl.

Nini H. Jonkman, Email: n.h.jonkman@vu.nl

Kira Scheerman, Email: k.scheerman@vumc.nl.

Sjors Verlaan, Email: g.verlaan@vumc.nl.

Carel G. M. Meskers, Email: c.meskers@vumc.nl

Andrea B. Maier, Phone: +61 3 8387 2137, Email: andrea.maier@mh.org.au

References

- 1.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM et al. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Peterson SJ, Braunschweig CA. Prevalence of Sarcopenia and Associated Outcomes in the Clinical Setting. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;31:40–48. doi: 10.1177/0884533615622537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Pena C, Garcia-Fabela LC, Gutierrez-Robledo LM et al. Handgrip strength predicts functional decline at discharge in hospitalized male elderly: a hospital cohort study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Vetrano DL, Landi F, Volpato S, et al. Association of sarcopenia with short- and long-term mortality in older adults admitted to acute care wards: results from the CRIME study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glu034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Landi F, Calvani R, Ortolani E, et al. The association between sarcopenia and functional outcomes among older patients with hip fracture undergoing in-hospital rehabilitation. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:1569–1576. doi: 10.1007/s00198-017-3929-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierik VD, Meskers CGM, Van Ancum JM, et al. High risk of malnutrition is associated with low muscle mass in older hospitalized patients - a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:118. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0505-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cerri AP, Bellelli G, Mazzone A, et al. Sarcopenia and malnutrition in acutely ill hospitalized elderly: Prevalence and outcomes. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gariballa S, Alessa A. Association between muscle function, cognitive state, depression symptoms and quality of life of older people: evidence from clinical practice. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30(4):351–7. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0775-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanchez-Rodriguez D, Marco E, Miralles R, et al. Sarcopenia, physical rehabilitation and functional outcomes of patients in a subacute geriatric care unit. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verlaan S, Van Ancum JM, Pierik VD, et al. Muscle Measures and Nutritional Status at Hospital Admission Predict Survival and Independent Living of Older Patients - the EMPOWER Study. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6:161–166. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2017.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clynes MA, Edwards MH, Buehring B, et al. Definitions of Sarcopenia: Associations with Previous Falls and Fracture in a Population Sample. Calcif Tissue Int. 2015;97:445–452. doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-0044-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, et al. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: Results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreland JD, Richardson JA, Goldsmith CH, et al. Muscle weakness and falls in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1121–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pijnappels M, van der Burg PJ, Reeves ND, et al. Identification of elderly fallers by muscle strength measures. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008;102:585–592. doi: 10.1007/s00421-007-0613-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Szulc P, Beck TJ, Marchand F, et al. Low skeletal muscle mass is associated with poor structural parameters of bone and impaired balance in elderly men--the MINOS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:721–729. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Rekeneire N, Visser M, Peila R, et al. Is a fall just a fall: correlates of falling in healthy older persons. The Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. Geriatrics Society. 2003;51:841–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benichou O, Lord SR. Rationale for Strengthening Muscle to Prevent Falls and Fractures: A Review of the Evidence. Calcif Tissue Int. 2016;98:531–545. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012:Cd007146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Mahoney JE, Palta M, Johnson J, et al. Temporal association between hospitalization and rate of falls after discharge. Arch Intern Med. 2000:160, 2788–2195. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Mahoney J, Sager M, Dunham NC, et al. Risk of falls after hospital discharge. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:269–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill AM, Hoffmann T, McPhail S, et al. Evaluation of the sustained effect of inpatient falls prevention education and predictors of falls after hospital discharge--follow-up to a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011:66, 1001–1012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Van Ancum JM, Scheerman K, Pierik VD, et al. Muscle Strength and Muscle Mass in Older Patients during Hospitalization: The EMPOWER Study. Gerontology. 2017;63:507–514. doi: 10.1159/000478777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963:185, 914–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Williamson A, Hoggart B. Pain: a review of three commonly used pain rating scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005;14:798–804. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Holden MK, Gill KM, Magliozzi MR, et al. Clinical gait assessment in the neurologically impaired. Reliability and meaningfulness. Phys Ther. 1984:64, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Upadhyaya AK, Rajagopal M, Gale TM. The Six Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) as a screening test for dementia: comparison with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3:138–142. doi: 10.2174/1874609811003020138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruizenga HM, Seidell JC, de Vet HC, et al. Development and validation of a hospital screening tool for malnutrition: the short nutritional assessment questionnaire (SNAQ) Clin Nutr. 2005;24:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2004.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bijlsma AY, Meskers CG, van den Eshof N, et al. Diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia and physical performance. Age (Dordr). 2014;36:275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Reijnierse EM, de Jong N, Trappenburg MC, et al. Assessment of maximal handgrip strength: how many attempts are needed? J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:466–474. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibson MJ, Andres RO, Isaacs B, et al. The prevention of falls in later life. A report of the Kellogg International Work Group on the Prevention of Falls by the Elderly. Dan Med Bull. 1987;34:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oud FM, de Rooij SE, Schuurman T, et al. Predictive value of the VMS theme 'Frail elderly': delirium, falling and mortality in elderly hospital patients. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2015;159:A8491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beenakker KG, Ling CH, Meskers CG, et al. Patterns of muscle strength loss with age in the general population and patients with a chronic inflammatory state. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9:431–436. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spruit MA, Sillen MJ, Groenen MT, et al. New normative values for handgrip strength: results from the UK Biobank. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 11. 2013;14:775.e5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Wannamethee SG, Atkins JL. Muscle loss and obesity: the health implications of sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015:74, 405–412. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Mitchell RJ, Lord SR, Harvey LA, et al. Associations between obesity and overweight and fall risk, health status and quality of life in older people. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38:13–18. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faulkner KA, Cauley JA, Studenski SA, et al. Lifestyle predicts falls independent of physical risk factors. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:2025–2034. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0909-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling CH, Taekema D, de Craen AJ et al. Handgrip strength and mortality in the oldest old population: the Leiden 85-plus study. CMAJ. 2010;182:429–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Hayakawa T, Hashimoto S, Kanda H, et al. Risk factors of falls in inpatients and their practical use in identifying high-risk persons at admission: Fukushima Medical University Hospital cohort study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e005385. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pfortmueller CA, Lindner G, Exadaktylos AK. Reducing fall risk in the elderly: risk factors and fall prevention, a systematic review. Minerva Med. 2014;105:275–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bijlsma AY, Pasma JH, Lambers D, et al. Muscle strength rather than muscle mass is associated with standing balance in elderly outpatients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14:493–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orr R. Contribution of muscle weakness to postural instability in the elderly. A systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;46:183–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ding L, Yang F. Muscle weakness is related to slip-initiated falls among community-dwelling older adults. J Biomech. 2016;49:238–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Z-scores of muscle parameters at admission and pre- and post-hospitalization falls, stratified by sex. Adjusted models of the standardized measures of HGS, SMM, SMI and RMM stratified for sex by z-scores. (DOCX 17 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.