Abstract

Background

Mutations in the aggrecan (ACAN) gene can cause short stature (with heterogeneous clinical phenotypes), impaired bone maturation, and large variations in response to growth hormone (GH) treatment. For such cases, long-term longitudinal therapy data from China are still scarce. We report that a previously unknown ACAN gene variant reduces adult height and we analyze the GH response in children from an affected large Chinese family.

Methods

Two children initially diagnosed with idiopathic short stature (ISS) and a third mildly short child from a large Chinese family presented with poor GH response. Genetic etiology was identified by whole exome sequencing and confirmed via Sanger sequencing. Adult heights were analyzed, and the responses to GH treatment of the proband and two affected relatives are summarized and compared to other cases reported in the literature.

Results

A novel ACAN gene variant c.7465 T > C (p. Gln2364Pro), predicted to be disease causing, was discovered in the children, without evident syndromic short stature; mild bone abnormity was present in these children, including cervical-vertebral clefts and apophyses in the upper and lower thoracic vertebrae. Among the variant carriers, the average adult male and female heights were reduced by − 5.2 and − 3.9 standard deviation scores (SDS), respectively. After GH treatment of the three children, first-year heights increased from 0.23 to 0.33 SDS (cases in the literature: − 0.5 to 0.8 SDS), and the average yearly height improvement was 0.0 to 0.26 SDS (cases in the literature: − 0.5 to 0.9 SDS).

Conclusions

We report a novel pathogenic ACAN variant in a large Chinese family which can cause severe adult nonsyndromic short stature without evident family history of bone disease. The evaluated cases and the reports from the literature reveal a general trend of gradually diminishing yearly height growth (measured in SDS) over the course of GH treatment in variant-carrying children, highlighting the need to develop novel management regimens.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12881-018-0591-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Aggrecan, ACAN gene, Short stature, Adult height, Growth hormone

Background

Human linear growth is a complex process determined primarily by genetic factors and modulated by environmental factors [1]. Based on its etiology, short stature can be divided into primary growth disorder, secondary growth disorder, and idiopathic short stature (ISS) [2, 3]. ISS refers to short stature with no apparent cause and is often described as either sporadic cases or familial short stature [2]. With the development of sequencing technologies, ISS has been found, in some patients, to be caused by mutations in genes involved in the hypothalamic-pituitary-growth hormone (GH) axis, such as GH1, GHR, and GHRHR (GHRH receptor) [4–7]. Genetic defects in the GH axis only constitute a small fraction of clinically diagnosed short-stature cases [8]. Defects in growth height are probably associated with other yet-to-be-identified genes [9].

Recent studies found that ACAN (MIM 155760, NM_013227.3) mutations are associated with accelerated bone maturation and progressive growth failure [4, 10]. In a prospective clinical study of 290 patients born small for gestational age (SGA) with short stature [11], four patients were identified as carrying heterozygous ACAN mutations and showed large variation in response to GH treatment. A recent study indicated that ACAN mutations are associated with short stature without syndromic manifestations [12]. However, studies on the relationship between ACAN gene mutations and adult height are scarce, and the reported data are typically from small family pedigrees. Thus, the optimal management of child mutation carriers remains unclear. We have analyzed the effects of an ACAN variant on adult height, based on data from one large Chinese family. In addition, we report the affected children’s response to GH treatment and summarize the effects of GH treatment on individuals with ACAN mutations reported in the literature.

Methods

Subjects and diagnosis

This study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee of the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University. Three children from the same large family, comprising 90 members, were recruited. Two of the children (Fig. 1. IV:23 and IV:44) were initially referred to us due to their short statures, according to the growth charts for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years [13]. Normal GH secretion in both children was confirmed by a peak of GH ≥10 ng/mL in insulin or arginine provocative tests. After evident physical deformities and organic etiologies were excluded, the primary diagnosis of ISS was made according to the diagnosis consensus [3]. The third child, for whom an initial height record was lacking, had height (Fig. 1. III:21) -0.88 standard deviation score (SDS) from the same family and had received 1 year of GH therapy before being referred to our clinic. We initiated GH therapy in these three children at a dose between 40 and 60 μg/kg/d and titrated to maintain serum IGF-1 levels between the average and + 2 standard deviations (SDs) of the reference [3]. All three children showed a poor response to GH treatment according to the criterion of SDS < 0.5 proposed by Patel and Clayton [14]. Therefore, the three children and their family members were offered genetic testing. Among the 90 family members, 62 subjects were available.

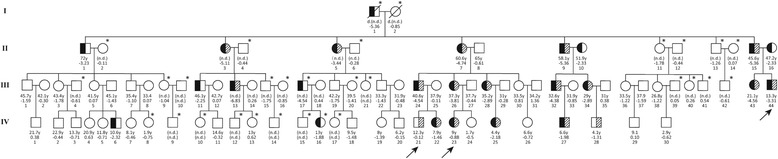

Fig. 1.

The family pedigree of members with and without the ACAN p. Gln2364Pro variant. Age and height are listed below each symbol. Black arrows: three children whose bloods were performed WES. Half-black symbols: family members with short stature (height < -2SD). Half-shaded symbols: family members carrying the ACAN mutation. An asterisk next to a symbol indicates that a blood sample was unavailable. A slash with a symbol indicates that the individual is deceased. n.d.: not determined

Whole exome sequencing

Whole exome sequencing was performed with genomic DNA extracted (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit, Qiagen, Germany) from subjects’ blood samples. Exomes were enriched with Illumina’s SureSelect Human All Exon kit V4, targeting 50 Mb of sequence from exons and flanking regions. Sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Reads with adaptors, reads with > 10% of unknown bases (Ns), and low-quality reads with > 50% of low-quality bases (i.e., bases with a sequencing quality of 5 or less) were discarded from the raw data to generate clean reads, 90-bp paired-end and with at least 100-fold average sequencing depth. Clean reads were aligned to the reference human genome (UCSC hg19) by using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) (v.0.5.9-r16). Subsequent processing steps of sorting, merging, and removing duplicates for the BAM files were performed by using SAMtools and Picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Mutation calls, which differed from the reference sequence, were obtained with the use of GATK. Mutations were annotated by ANNOVAR and VEP software [15, 16]. Mutations with suboptimal quality scores were removed from consideration. The remaining mutations were compared computationally with the list of reported mutations from the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD, professional version). Mutations in this database with minor allele frequency < 5% according to either the 1000 Genomes Project or ExAC data of The Exome Aggregation Consortium (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/) were retained. For changes that were not represented in the HGMD, synonymous mutations, intronic mutations that were > 15 bp from exon boundaries (which are unlikely to affect messenger RNA splicing), and common mutations (minor allele frequency > 1%) were discarded [15, 16].

Bioinformatics assessment of variant function

To assess the effects of the variant, we conducted analyses using SIFT, PolyPhen-2, and MutationTaster software, to predict possible deleterious effects [17–19]. In addition, we performed conservation analysis, using the PhyloP score embedded in the USCS genome browser [20]. Three-dimensional models of aggrecan protein were produced by SWISS-MODEL SERVER [21].

Variant confirmation by sanger sequencing

After the identification of an ACAN variant in family members, we performed Sanger sequencing on PCR products containing the variant (in exon 14). The purified DNA was used as template for PCR amplification. The reaction mixture (20 μL) contained 50 ng DNA; 1 U Taq DNA polymerase (Promega, USA); 1.5 mM MgCl2; 0.25 mM each dNTP; and 0.5 μM primers. The primers for the amplification of ACAN were as follows: ACAN-Forward: CATCTGCCATCCCCTGGT, ACAN-Reverse: CCTACACCGCCACTCTCCTC. The thermal cycling conditions for the PCR reactions consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95 °C for 5 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, primer annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final step at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR products were sequenced in an ABI sequencer 3500 xL GA (Applied Biosystems). The sequence data were evaluated using Mutation Surveyor software and compared with the reference sequence of ACAN (NM_001135).

Family members

After identification of ACAN variant in the three children who came to our clinic, we invited all family members to participate in our study; the pedigree is shown in Fig. 1. Genotyping and collection of basic information (height, age, and history of bone disorders) in the adult family members were conducted after obtaining informed consent from the subjects. For persons younger than 18 y, informed consent was obtained from the parents.

Measurement of responses to growth hormone treatment

During GH treatment of the three children, we measured the levels of serum IGF-1 and IGF-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) every three or six months by solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay via an automated MMULITE 1000 immunoassay system (Siemens, Munich, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Height, body mass index (BMI, weight (kg) divided by the square of the height (m)), and bone age (GP atlas) were measured. SDS values for height and BMI were calculated using national references. We used a t-test (SPSS Version 17.0) to compare the differences in height between family members with and without the ACAN variant.

Results

ACAN variant and functional in silico prediction

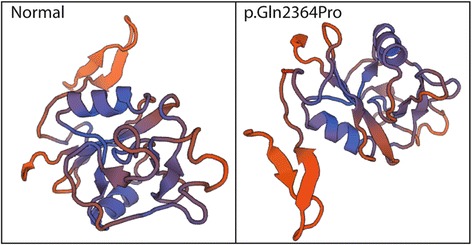

Whole exome sequencing to a median of 150× 125.47 (125.47~ 165.65) coverage in the index patients identified 825,823 genetic variants of which 119 were not found in dbSNP137, ExAC, the 1000 Genomes database, or in internal database at 0.5% allele frequency. Further analysis showed that only one variant, c.7465 T > C (p. Gln2364Pro), was consistent with the phenotype of the index and shared by the three affected children in this family. Subsequent Sanger sequencing detected the same variant (p. Gln2364Pro) totally in 19 of 62 blood samples available which was not present in the HGMD or GNOMAD databases. These 19 subjects (10 females and 9 males) ranged in age from 4.1 to 60.6 y and included 7 children (< 18 y; 3 females, 4 males) and 12 adults (7 females, 5 males). The missense variant was predicted by in silico tools to be deleterious (Table 1). Amino acid conservation analysis showed that the affected site was highly conserved in at least fifteen species, including humans (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The three-dimensional models for aggrecan protein with the variant, produced by SWISS-MODEL SERVER (Fig. 2), showed significant anomalies in the formation of normal dimensional structure.

Table 1.

Characteristics of children with ACAN variant treated with growth hormone

| Relative 1 | Relative 2 | Proband | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | Male | Male |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3 | 3 | 3.5 |

| Birth height (cm) | 50 | 51 | 50 |

| ACAN mutation | c.7465 T > Ca | c.7465 T > Ca | c.7465 T > Ca |

| Protein changes | p.Gln2364Pro | p.Gln2364Pro | p.Gln2364Pro |

| First visit | |||

| Age (y) | 5.6 | 7.8 | 6.4 |

| Height (cm) | 104.5 | 122.5 | 100.5 |

| HSDS | − 2.09 | − 0.88 | − 3.74 |

| Weight (kg) | 18 | 25 | 17.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 16.48 | 16.66 | 17.33 |

| Peak growth hormone (ng/ml) | 12.1 | ND | 15.1 |

| IGF1(ng/ml) | 290 | 200 | 148 |

| IGFBP3 (μg/ml) | 4.15 | 7.96 | 3.43 |

| Bone age (y) | 6.5 | 9.5 | 6 |

HSDS height standard deviation scores, BMI body mass index, IGF1 insulin-like growth factor 1, IGFBP3 insulin-like growth factor binding factor 3, ND not detected; a in silico prediction: Sift: affect protein function (score = 0.00); Polyphen: probably damaging (score = 1)

Fig. 2.

The three-dimensional models for aggrecan protein with and without the variant

ACAN variant and its correlation with adult height

Among the 31 adult family members (15 females, 16 males), there were 12 adult variant carriers (7 females, 5 males). All of the adults with the ACAN mutation had severe short stature (height < − 2 SD, Table 2), and the difference in height between members with and without the ACAN variant was significant in both genders (p < 0.001, Table 2).

Table 2.

Adult heights of family members with and without ACAN variant

| Variant (+) | Variant (−) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | (n = 5) | (n = 11) | |

| Height (cm) | 141.2 ± 4.4 | 162.2 ± 8.1 | < 0.0001 |

| HSDS | −5.2 ± 0.7 | −1.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Female | (n = 7) | (n = 8) | |

| Height (cm) | 139.4 ± 4.9 | 156.0 ± 5.8 | < 0.0001 |

| HSDS | −3.9 ± 0.9 | − 0.9 ± 1.1 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD. HSDS height standard deviation score

ACAN variant and response to GH treatment

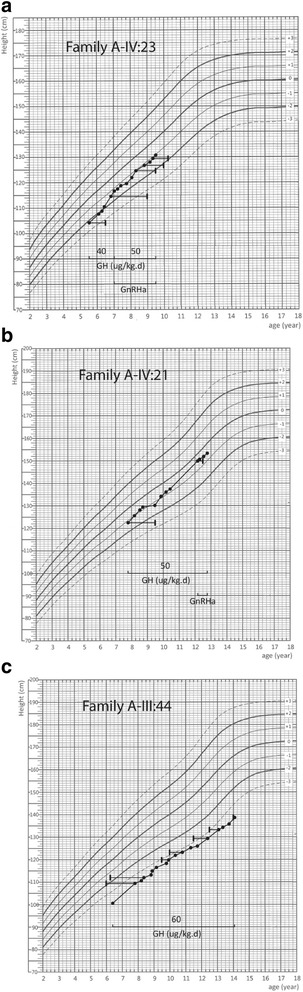

The major characteristics of the three children who received GH treatment are shown in Table 1. The proband (Fig. 1, III:44) was a boy born with normal birth length and weight. However, his father’s height was 153 cm (− 5.36 SDS) and his mother’s height was 140 cm (− 2.33 SDS). He was referred to us at the age of 6.4 y with height 100.5 cm (− 3.74 SDS). After GH therapy, 60 μg/kg/d for 8 years, his height was − 3.75 SD below average, at latest evaluation (age 14.1 y, Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Growth charts of patients with the ACAN p. Gln2364Pro variant. Vertical bars represent bone age. GH; growth hormone. GnRHa; gonadotropin releasing hormone analog

The affected relative 1 in the family was a girl (Fig. 1. IV:23), born full term, with normal birth length and weight. She was referred to our clinic at the age of 5.6 y with height 104.5 cm (− 2.09 SDS) and bone age (BA) 6.5 y. Her father’s height was 170 cm (− 0.44 SDS), and her mother’s height was 138 cm (− 4.19 SDS). Radiographs showed slight abnormalities of her spine, including cervical-vertebral clefts and apophyses in the upper and lower thoracic vertebrae (Additional file 2: Figure S2). We started GH treatment at dose 40 μg/kg/d, and she received GnRHa for pubertal management at age 7. Her height was − 1.07 SDS at her latest visit (age 9.5 y, Fig. 3a).

Relative 2 (Fig. 1. IV:21) was a boy born with normal birth length and weight at full term. He visited our department at the age of 7.8 y with height 122.5 cm (− 0.88SDS). His father’s height was 150 cm (− 3.72 SDS), and his mother’s height was 160 cm (− 0.11 SDS). His bone age (BA) was 9.5 y at his first visit. He received GH therapy, 50 μg/kg/d (Fig. 3b). He received GnRHa at 12.2 y due to his pubertal development. His latest height was − 0.31 SD (at age 12.8 y, Fig. 3b).

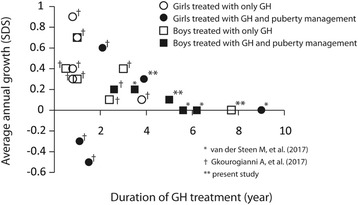

Responses to GH treatment reported in other studies

In addition to reporting on our current cases, we reviewed the two other available studies on children with an ACAN variant, which involved 18 patients. The characteristics of these patients and their responses to GH treatment are shown in Table 3. The change in height SDS during the first year of treatment ranged from − 0.5 SDS to 0.8 SDS, and the overall yearly height change during GH treatment was − 0.5 SDS to 0.9 SDS. Among these children, there was a general trend of a gradual reduction in yearly height SDS growth over the course of GH treatment (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Patients with ACAN variant treated with growth hormone

| N | Gender | ACAN Variant | GH starting age (y) | Initial Height (SDS) | GH dosage | 1st year growth ΔSDS | GH duration (y) | Additional treatment | Average growth ΔSDS/y | Latest Height (SDS) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| van der Steen M, et al. (2017) | |||||||||||

| 1 | Female | c.1608C > A (p.Tyr536*) | 5.0 | −3.7 | 1-2 mg/m2/d | + 0.7 | 9 | GnRHa for 1.5 y | −0.0 | − 3.9 (AH) | |

| 2 | Male | c.1608C > A (p. Tyr536*) | 11.9 | −2.4 | 2 mg/m2/d | + 0.7 | 3.5 | GnRHa for 2 y | + 0.2 | −1.6 | |

| 3 | Male | c.7090C > T (p.Gln2364*) | 11.7 | −2.7 | 2 mg/m2/d | + 0.1 | 5.6 | GnRHa for 2 y | −0.0 | −2.9 | |

| 4 | Male | c.4762_4765del (p.Gly1588fs) | 12.3 | −2.7 | 1 mg/m2/d | 0 | 6.2 | GnRHa for 2 y | + 0.0 | −2.6 (AH) | |

| Gkourogianni A, et al. (2017) | |||||||||||

| 1 | Male | c.272delA (p.Arg93Alafs*) | 8.7 | −3.3 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.8 | 2.6 | Along with aromatase inhibitor | + 0.2 | −2.7 | |

| 2 | Male | c.272delA (p.Arg93Alafs*) | 6.3 | −1.8 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.2 | 2.4 | + 0.1 | −1.6 | ||

| 3 | Female | c.7064 T > C (p.Leu2355Pro) | 12.0 | −3.2 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | −0.5 | 1.5 | Along with GnRHa | −0.5 | −3.9 (AH) | |

| 4 | Male | c.5391 (p.Gly1797Glyfs*) | 6.2 | −2.6 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.6 | 1.0 | + 0.3 | −2.0 | ||

| 5 | Female | c.7429G > A (p.Val2417Met) | 11.3 | −0.8 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | −0.2 | 1.1 | Along with GnRHa | −0.3 | −1.1 | |

| 6 | Female | c.7429G > A (p.Val2417Met) | 5.5 | −1.2 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.4 | 3.8 | + 0.1 | −0.7 | ||

| 7 | Female | c.1443G > T (p.Glu415*) | 8.5 | −1.7 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.6 | 2.1 | GnRHa for 1 y | + 0.6 | −0.5 | |

| 8 | Male | c.1443G > T (p.Glu415*) | 5.7 | −1.7 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.2 (0.5y) | 0.5 | + 0.4 | −1.5 | ||

| 9 | Female | c.1443G > T (p.Glu415*) | 8.4 | −0.7 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.2 (0.8y) | 0.8 | + 0.3 | −0.5 | ||

| 10 | Female | c.1443G > T (p.Glu415*) | 3.2 | −3.0 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.7 (0.8y) | 0.8 | + 0.9 | −2.3 | ||

| 11 | Female | c.4657G > T (p.Glu1553*) | 8.7 | −2.9 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.3 (0.8y) | 0.8 | + 0.4 | −2.6 | ||

| 12 | Male | c.223 T > C (p.Trp75Arg) | 5.5 | −2.0 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.7 | 1.0 | + 0.7 | −1.3 | ||

| 13 | Female | c.223 T > C (p.Trp75Arg) | 8.3 | −1.9 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.7 | 1.0 | + 0.7 | −1.2 | ||

| 14 | Male | c.1425delA (p.Val478Serfs*) | 7.4 | −2.9 | 30-50 μg/kg/d | + 0.4 | 3.0 | + 0.4 | −1.7 | ||

| Present study | |||||||||||

| 1 | Female | c.7465 T > C (p.Gln2364Pro) | 5.6 | −2.09 | 40 μg/kg/d | + 0.33 | 3.9 | GnRHa for 2 y | + 0.26 | −1.07 | |

| 2 | Male | c.7465 T > C (p.Gln2364Pro) | 7.8 | −0.88 | 50 μg/kg/d | + 0.27 | 5.0 | GnRHa for 1 y | + 0.11 | −0.31 | |

| 3 | Male | c.7465 T > C (p.Gln2364Pro) | 6.4 | −3.74 | 60 μg/kg/d | + 0.23 | 7.7 | −0.0 | −3.75 | ||

GH growth hormone, SDS standard deviation score, GnRHa gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist, AH adult height

Fig. 4.

Average annual change in the SDS of height in subjects with ACAN p. Gln2364Pro variant receiving GH treatment

Discussion

Human height is a highly heritable trait that involves many genes [22]. In this study, we identified a novel ACAN gene pathogenic variant (c.7465 T > C) and found that mean adult height was − 5.2 ± 0.7 SDS and − 3.9 ± 0.9 SDS in male and female variant carriers, respectively. Studies of human mating preferences with respect to height have found that short men prefer small height differences [23]; therefore, in the family studied here, the shortness of both parents might cumulatively affect the heights of their descendants. Our current study of a large family provides the first evidence from a Chinese population that an ACAN gene variant can cause low adult height in the absence of a high incidence of familiar bone malformation.

ACAN encodes aggrecan, which is the main proteoglycan in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of cartilage [24]. Aggrecan binds chondroitin sulfate and keratan sulfate to its central region, and it forms large aggregates with hyaluronan polymer through its N-terminal globular domain (G1) to form the cartilage ECM scaffold [25]. Aggrecan has two additional globular domains (G2 and G3) that flank its central region. The G3 domain contains a C-type lectin-binding domain that is important in interactions with other extracellular proteins [25]; the function of the G2 domain is unknown. Although aggrecan dysfunction is strongly associated with chondropathy and distinct phenotypes, only a few patients with aggrecan deficiency have been reported, likely due to the wide phenotypic spectrum of ACAN mutations [26]. Patients with aggrecan mutations can remain undiagnosed owing to their presentation of clinically less significant conditions, such as ISS [4, 12, 26, 27]. Some studies have identified ACAN mutations among patients with syndromic short stature conditions such as spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia, Kimberley type, short stature with early-onset osteoarthritis and/or osteochondritis dissecans [28–30]; short stature might be the most obvious manifestation of ACAN mutations [26]. A recent study showed that ACAN nonsense mutations are associated with short stature without advanced bone age among Chinese individuals [12]. This evidence and the findings of our study suggest that environmental factors or other undetected genetic variations also influence the manifestations of patients with ACAN mutations.

To date, 25 pathogenic ACAN mutations have been reported in 24 families with the dominant form of short stature [11, 12, 26]. The reported mutations were present in all domains of the gene; however, all of the mutations disrupted the integrity of at least one of the aggrecan globular domains (G1, G2 or G3) [26]. The association between ACAN mutations and adult height suggests that these ACAN mutations impair chondrogenesis in a similar way. In mice, aggrecan deficiency follows a recessive pattern, and homozygous deletion of aggrecan is perinatally lethal [31, 32]. Similarly, in humans, the homozygous missense mutation (p. Asp2267Asn) in ACAN causes extreme short stature and skeletal dysplasia [30], whereas patients heterozygous for the mutation have less severe phenotypes. It is likely that the impairment of growth plate chondrogenesis is due to insufficient function rather than gain-of-function.

Considering the progressive development of short stature among patients with ACAN mutations [25], GH-based treatment is used to rescue height deficiency and prevent further height loss. We found that, among patients with ACAN mutations, the response to GH treatment during the first year was generally poor and was correlated with the overall response to GH treatment; however, patients with ACAN mutations treated with GH were 5–8 cm taller than their same-sex family members [11]. GH promotes height development by stimulating IGF-1 production and chondrocyte differentiation; therefore, aggrecan deficiencies are unlikely to be repaired by GH alone. Future research to identify molecules to restore normal ECM is needed to improve treatment options for children with ACAN mutations.

Conclusions

We have identified a novel variant in the ACAN gene associated with minor bone abnormality without a high incidence of familiar bone malformation. Response to GH therapy was poor compared with the effect in GHD children; however, our results and those of other studies support the view that long-term GH therapy is beneficial for preventing age-accompanied cumulative deterioration of growth loss. Earlier genetic diagnosis and long-term therapy would be useful to obtain better clinical outcomes for children with ACAN mutations.

Additional files

Figure S1. The amino acid "Q" in red represents the conservative property in position "p. Gln2364Pro" among differet species. (PDF 416 kb)

Figure S2. Black arrow: Cervical-vertebral cleft in the spine. White arrows: Apophyses in the upper and lower thoracic vertebrae. (PDF 2309 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the family members for their valuable contribution to the study. We are also grateful to Professor David Josephy from the Department of Molecular & Cellular Biology, College of Biological Science, University of Guelph, Canada, for the revision of this manuscript. The authors thank all of the physicians, nurses, and technicians involved for their assistance.

Funding

Feihong Luo is supported by Minhang District Talented Development Foundation and the Development Project of Shanghai Peak Disciplines-Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine. The study is supported by Shanghai Key Laboratory of Birth Defect, Children’s Hospital of Fudan University new development project (2014–2015).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BA

Bone age

- BMI

Body mass index

- BWA

Burrows-wheeler aligner

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- GH

Growth hormone

- GHD

Growth hormone deficiency

- HGMD

Human gene mutation database

- IGFBP3

IGF-binding protein 3

- ISS

Idiopathic short stature

- OMIM

Online Mendelian inheritance in man

- SDS

Standard deviation score

- SGA

Small gestational age

Authors’ contributions

FHL conducted clinical diagnosis and management of the patients, reviewed the data and manuscript, and was the guarantor of the work. DDX performed genetic testing and contributed to writing the manuscript. CJS performed the literature search, conducted data synthesis and reviewed the manuscript. ZYZ performed the Sanger sequencing and contributed to manuscript writing. BBW, LY and ZC conducted genetic analysis. MYZ, LX, RQC and JWN helped manage the patients and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee in Children’s Hospital of Fudan University(No. 2010–2-26, 2012–130). The study conforms to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent from participants (in the cases of children, from their parents), was obtained using an institutional consent form.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient/parents of the patients who were minors. Copies of the consent forms are available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12881-018-0591-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Dandan Xu, Email: xudandan-rita@163.com.

Chengjun Sun, Email: chengjsun@163.com.

Zeyi Zhou, Email: zeyi_zhou@berkeley.edu.

Bingbing Wu, Email: bingbingwu2010@163.com.

Lin Yang, Email: yanglin_fudan@163.com.

Zhuo Chang, Email: alice_lzl@163.com.

Miaoying Zhang, Email: miaoyingzhang@126.com.

Li Xi, Email: drxili@163.com.

Ruoqian Cheng, Email: chengrq78@163.com.

Jinwen Ni, Email: chris_kris7@hotmail.com.

Feihong Luo, Email: luofh@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Argente J. Challenges in the Management of Short Stature. Horm Res in Paediatr. 2016;85:2–10. doi: 10.1159/000442350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen P, Rogol AD, Deal CL, Saenger P, Reiter EO, Ross JL, Chernausek SD, Savage MO, Wit JM, I.S.S.C.W. participants Consensus statement on the diagnosis and treatment of children with idiopathic short stature: a summary of the growth hormone research society, the Lawson Wilkins pediatric Endocrine Society, and the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Workshop. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4210–4217. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grimberg A, DiVall SA, Polychronakos C, Allen DB, Cohen LE, Quintos JB, Rossi WC, Feudtner C, Murad MH. Drug and therapeutics committee and ethics Committee of the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Guidelines for growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-I treatment in children and adolescents: growth hormone deficiency, idiopathic short stature, and primary insulin-like growth factor-I deficiency. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016;86:361–397. doi: 10.1159/000452150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quintos JB, Guo MH, Dauber A. Idiopathic short stature due to novel heterozygous mutation of the aggrecan gene. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2015;28:927–932. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2014-0450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shima H, Tanaka T, Kamimaki T, Dateki S, Muroya K, Horikawa R, Adachi M, Naiki Y, Tanaka H, Mabe H, et al. Japanese. Systematic molecular analyses of SHOX in Japanese patients with idiopathic short stature and Leri-Weill dyschondrosteosis. J Hum Genet. 2016;61:585–591. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caliebe J, Broekman S, Boogaard M, Bosch CA, Ruivenkamp CA, Oostdijk W, Kant SG, Binder G, Ranke MB, Wit JM, Losekoot M. IGF1, IGF1R and SHOX mutation analysis in short children born small for gestational age and short children with normal birth size (idiopathic short stature) Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;77:250–260. doi: 10.1159/000338341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khetarpal P, Das S, Panigrahi I, Munshi A. Primordial dwarfism: overview of clinical and genetic aspects. Mol Genet Genomics : MGG. 2016;291:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alatzoglou KS, Dattani MT. Genetic causes and treatment of isolated growth hormone deficiency-an update. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:562–576. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2010.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baron J, Savendahl LF, De L, Dauber A, Phillip M, Wit JM, Nilsson O. Short and tall stature: a new paradigm emerges. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2015.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baron J, Savendahl L, De Luca F, Dauber A, Phillip M, Wit JM, Nilsson O. Short stature, accelerated bone maturation, and early growth cessation due to heterozygous aggrecan mutations. The J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1510–E1518. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Steen M, Pfundt R, Maas S, Bakker-van Waarde WM, Odink RJ, Hokken-Koelega ACS. ACAN gene mutations in short children born SGA and response to growth hormone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1458–1467. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X, Gui B, Su J, Li H, Li N, Yu T, Zhang Q, Xu Y, Li G, Chen Y, Qing Y, Chinese Genetic Short Stature, Consortium. Li C, Luo J, Fan X, Ding Y, Li J, Wang J, Wang X, Chen S, Shen Y. Novel pathogenic ACAN variants in non-syndromic short stature patients. Clin Chim Acta. 2017;469:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Ji CY, Zong XN, Zhang YQ. Height and weight standardized growth charts for Chinese children and adolescents aged 0 to 18 years. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi (Chinese J Pediatr) 2009;47:487–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel L, Clayton PE. Predicting response to growth hormone treatment. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:229–237. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0611-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP effect predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pollard KS, Hubisz MJ, Rosenbloom KR, Siepel A. Detection of nonneutral substitution rates on mammalian phylogenies. Genome Res. 2010;20:110–121. doi: 10.1101/gr.097857.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biasini M, Bienert S, Waterhouse A, Arnold K, Studer G, Schmidt T, Kiefer F, Cassarino TG, Bertoni M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: modelling protein tertiary and quaternary structure using evolutionary information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W252–W258. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wit JM, Oostdijk W, Losekoot M, van Duyvenvoorde HA, Ruivenkamp CA, Kant SG. Mechanisms in endocrinology: novel genetic causes of short stature. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;174:145–173. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stulp G, Buunk AP, Pollet TV, Nettle D, Verhulst S. Are human mating preferences with respect to height reflected in actual pairings? PLoS One. 2013;8:e54186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sophia Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: structure, composition, and function. Sports health. 2009;1:461–468. doi: 10.1177/1941738109350438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aspberg A. The different roles of aggrecan interaction domains. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:987–996. doi: 10.1369/0022155412464376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gkourogianni A, Andrew M, Tyzinski L, Crocker M, Douglas J, Dunbar N, Fairchild J, Funari MF, Heath KE, Jorge AA, et al. Clinical characterization of patients with autosomal dominant short stature due to Aggrecan mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:460–469. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dateki S, Nakatomi A, Watanabe S, Shimizu H, Inoue Y, Baba H, Yoshiura KI, Moriuchi H. Identification of a novel heterozygous mutation of the Aggrecan gene in a family with idiopathic short stature and multiple intervertebral disc herniation. J Hum Genet. 2017;62:717–721. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2017.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleghorn L, Ramesar R, Beighton P, Wallis G. A mutation in the variable repeat region of the aggrecan gene (AGC1) causes a form of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia associated with severe, premature osteoarthritis. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:484–490. doi: 10.1086/444401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stattin EL, Wiklund F, Lindblom K, Onnerfjord P, Jonsson BA, Tegner Y, Sasaki T, Struglics A, Lohmander S, Dahl N, Heinegard D, Aspberg A. A missense mutation in the aggrecan C-type lectin domain disrupts extracellular matrix interactions and causes dominant familial osteochondritis dissecans. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tompson SW, Merriman B, Funari VA, Fresquet M, Lachman RS, Rimoin DL, Nelson SF, Briggs MD, Cohn DH, Krakow D. A recessive skeletal dysplasia, SEMD aggrecan type, results from a missense mutation affecting the C-type lectin domain of aggrecan. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe H, Kimata K, Line S, Strong D, Gao LY, Kozak CA, Yamada Y. Mouse cartilage matrix deficiency (cmd) caused by a 7 bp deletion in the aggrecan gene. Nat Genet. 1994;7:154–157. doi: 10.1038/ng0694-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauing KL, Cortes M, Domowicz MS, Henry JG, Baria AT, Schwartz NB. Aggrecan is required for growth plate cytoarchitecture and differentiation. Dev Biol. 2014;396:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. The amino acid "Q" in red represents the conservative property in position "p. Gln2364Pro" among differet species. (PDF 416 kb)

Figure S2. Black arrow: Cervical-vertebral cleft in the spine. White arrows: Apophyses in the upper and lower thoracic vertebrae. (PDF 2309 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.