Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients often experience lower limb muscle dysfunction and wasting. Exercise-based training has potential to improve muscle function and mass, but literature on this topic is extensive and heterogeneous including numerous interventions and outcome measures. This review uses a detailed systematic approach to investigate the effect of this wide range of exercise-based interventions on muscle function and mass. PUBMED and PEDro databases were searched. In all, 70 studies (n = 2504 COPD patients) that implemented an exercise-based intervention and reported muscle strength, endurance, or mass in clinically stable COPD patients were critically appraised. Aerobic and/or resistance training, high-intensity interval training, electrical or magnetic muscle stimulation, whole-body vibration, and water-based training were investigated. Muscle strength increased in 78%, muscle endurance in 92%, and muscle mass in 88% of the cases where that specific outcome was measured. Despite large heterogeneity in exercise-based interventions and outcome measures used, most exercise-based trials showed improvements in muscle strength, endurance, and mass in COPD patients. Which intervention(s) is (are) best for which subgroup of patients remains currently unknown. Furthermore, this literature review identifies gaps in the current knowledge and generates recommendations for future research to enhance our knowledge on exercise-based interventions in COPD patients.

Keywords: COPD, pulmonary rehabilitation, exercise training, lower limb, muscle function, muscle mass

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a lung disease characterized by persistent airflow limitation.1 Nevertheless, many patients with COPD also commonly experience systemic features, such as impaired lower limb muscle function and muscle wasting.2 Cross-sectional research has reported that quadriceps strength is reduced by 20–30% in patients with COPD.2 This observed decrease in strength is proportional to the decrease in muscle mass in the majority of patients with COPD, suggesting the onset of disuse-related muscle atrophy instead of myopathy-related muscle atrophy.3 In line with this reasoning, patients with COPD generally are less physically active compared to healthy peers,4,5 which is directly related to lower limb muscle dysfunction.6 A decreased quadriceps endurance has also been established in COPD but is more variable across studies because of differences in test procedures.2 This lower limb muscle dysfunction clearly contributes to the observed exercise intolerance and exercise-induced symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue in patients with COPD.7 Moreover, lower limb muscle dysfunction has been associated with a worse health status, more hospitalizations, and worse survival.2

In turn, exercise-based interventions have the potential to reverse or at least stabilize lower limb muscular changes in patients with COPD.2,8 Exercise-based pulmonary rehabilitation programs are a cornerstone of the comprehensive care of patients with COPD.9 Indeed, international guidelines state that exercise training is the best available nonpharmacological therapy to improve lower limb muscle function and muscle mass in these patients.9,10 The comprehensive American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) statement provides only a short overview of the effects of exercise-based therapies on muscle function and muscle mass in patients with COPD,2 whereas actually the literature about this topic is extensive and heterogeneous including numerous interventions and outcome measures. A critically appraised and detailed overview of the impact of this wide range of exercise-based therapies on lower limb muscle function and muscle mass in patients with COPD is presented in this narrative review.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The included studies investigated the effects of any exercise training intervention on lower limb muscle strength, endurance, and mass in clinically stable patients with COPD. Studies investigating the muscle response to a single exercise test or a single exercise session were excluded. Studies that specifically investigated the effect of an additional intervention on top of exercise training were also excluded. The selected studies needed to include original data, but there were no restrictions regarding study design or muscle strength, endurance, and mass assessment used. Only studies published in English were included.

Search methods

Electronic databases PUBMED and PEDro were searched for articles published from inception until March 7, 2016. In PUBMED, the following search strategy was used: COPD AND (exercise OR exercise training OR rehabilitation OR pulmonary rehabilitation OR physical activity OR aerobic training OR endurance training OR resistance training OR strength training OR cycling OR walking OR neuromuscular electrical stimulation OR NMES OR magnetic stimulation). The search strategy was adapted to “COPD” alone when searching in PEDro to identify all relevant articles. Corresponding authors were contacted to provide full texts when not accessible via electronic databases. Reference screening of available reviews in the same field of research was also performed to expand the search for eligible articles.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (JDB and CB) performed the study screening based on the listed inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the first phase, both reviewers conducted a part of the title screening in a conservative manner, excluding only titles that undoubtedly did not fulfill the criteria. Next, both reviewers screened all remaining abstracts independently. Results were compared, discrepancies between reviewers were discussed, and a consensus-based decision was taken. Finally, full-text screening was performed in a similar way.

Data extraction

Information on sample size, study design (for studies comparing COPD with other disease states, only the data from patients with COPD is shown and the design described as single group pre post-test), baseline forced expiratory volume at first second (FEV1), age, exercise training parameters (frequency, intensity, modality, session and program duration), assessment modality, and relevant outcome measures of muscle strength, muscle endurance, and muscle mass were extracted from the articles. Mean relative change (percentages of baseline) between pre- and postmeasurements were extracted. If mean relative change (expressed as percentage of baseline) was not available, pre- and postvalues were used to manually calculate mean relative change as percentage of baseline: ([post – pre]/pre x 100). All extracted data are presented in Tables 2–7 (according to training modality) and Figures 1 –7. For Figure 4, a weighted mean relative change (percentage of baseline) was calculated per study as followed:

Table 2.

Aerobic training.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups posttraining | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O’Donnell et al., 199711 | 20 COPD | COPD: 41 (3) | COPD: 69 (2) | Single group pre post-test | 150 minutes: upper and lower limb exercises: walking, stair climbing, arm ergometry, cycling ergometry, treadmill exercise at or below Borg breathlessness rating corresponding to symptom-limited maximum rating | 6 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extension strength: isometrica Knee extension endurance: isometric contraction at 50% of maximum until exhaustiona | p < 0.001 ns | ↑21% – | – – |

| Mador et al., 200112 | 21 COPD | COPD: 45 (4) | COPD: 70 (2) | Single group pre post-test | Cycle ergometer and treadmill, calisthenics, and stretching exercises | 8 weeks (3x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometrica Unpotentiated twitch Potentiated twitch | p < 0.01 p = 0.049 p = 0.05 | ↑14.9% ↑9.7% ↑8.8% | – – – |

| Radom-Aizik et al., 200713 | 6 COPD, 5 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 39 (3); HC: 108 (8) | COPD: 72 (2); HC: 70 (2) | Noncontrolled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups | 45 minutes of cycle ergometer at 80% of individual Wmax | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps peak torque: isokinetic (60°/seconds)b | COPD (p = 0.003) ns HC | ↑13.6% – | Not reported |

| Vivodtzev et al., 200814 | 7 COPD, 8 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 29 (9); HC: 94 (22) | COPD: 60 (6); HC: 53 (11) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | 10–30 minutes of cycle ergometer at 50% of initial Wmax (if workload was tolerated, workload increased with 5 W) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometric.a Potentiated twitch | p = 0.04 ns | ↑10% – | – – |

| Vivodtzev et al., 201015 | 17 COPD: 10 training (TR), 7 control (C) matched for age, disease severity, and walking distance | TR: 62 (9); C: 63 (6) | TR: 47 (20); C: 54 (13) | Nonrandomized controlled trial | Cycling: initially at 38% of Wpeak. Progressive increase to 65% of Wpeak. Duration: initially 18 minutes and progressively increased to 30 minutes. | 4 weeks (5x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometric.a Quadriceps endurance: dynamic leg extension with weights corresponding to 30% MVC (12 movements per minute) up to exhaustiona | TR (p < 0.008) ns C; TR (p < 0.008) ns C | ↑14% – ↑58.6% – | TR > C (p < 0.05); TR > C (p < 0.05) |

| Guzun et al., 201216 | 8 COPD, 8 sedentary and healthy age and gender matched controls (HC) | COPD: 1.5 (0.16) L; HC: 3.3 (0.2) L (absolute FEV1 values) | COPD: 62 (4); HC: 59 (4) | Noncontrolled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | 45 minutes: cycle ergometer at 50% of Wpeak initially and progressed up to 80% of Wpeak. | 12 weeks (3x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometrica | ns COPD ns HC | – – | HC > COPD (p < 0.05)c |

| Farias et al., 201417 | 34 COPD: 18 training (TR), 16 control (C) | TR: 56 (16) C: 51 (14) | TR: 65 (10) C: 71 (8) | RCT | 40 minutes of walking, progressively increased to 60 minutes. | 8 weeks (5x/w) | 1 RM leg curl Muscle mass lower right leg (BIA) Muscle mass lower left leg (BIA) | TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C | ↑50% – ↑8.3% – ↑8.3% – | ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; MVC: maximum voluntary contraction; BIA: bioelectrical impedance analysis; Wpeak/max: peak/maximal workload.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer (e.g. Biodex).

cBetween groups difference based on post training values.

Table 3.

Resistance training.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups post training | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simpson et al., 199218 | 28 COPD: 14 training (TR), 14 control (C) | TR: 40 (19); C: 39 (21) | TR: 73 (5); C: 70 (6) | RCT | TR: 3 sets of 10 reps of arm curl, leg extension, and leg press at 50–85% of 1 RM | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extension 1 RM Leg press 1 RM Quadriceps strength: isometrica | TR (p < 0.01) ns C TR (p < 0.01) ns C TR (p < 0.01) ns C | ↑44% – ↑16% – ↑25.4% – | Not reported Not reported Not reported |

| Clark et al., 199617 | 48 COPD: 32 circuit training (TR), 16 control (C) | TR: 64 (29); C: 55 (22) | TR: 58 (8); C: 55 (8) | RCT | Home exercise program: every exercise for 30 up to 60 seconds: shoulder circling, full arm circling, increasing and decreasing circles, abdominal exercise, wall press-ups, sitting to standing, quadriceps exercise, calf raises, calf alternates, walking on the spot, and step up. | 12 weeks (7x/w) | Isokinetic muscle strengthb Isotonic muscle endurance (number of repetitions in 30 seconds) | ns TR ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C | – – ↑25 repse – | Not reported TR > C (p < 0.001) |

| Clark et al., 200019 | 43 COPD: 26 training (TR), 17 control (C); 52 healthy controls (HC) | TR: 76 (23); C: 79 (23); HC: 109 (16) | TR: 51 (10); C: 46 (11); HC: 51 (10) | RCT | TR: 10 reps of 8 exercises (bench press, body squat, squat calf, latissimus, arm curls, leg press, knee flexion, and hamstrings) at 70% of 1 RM | 12 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isotonic. Lower body muscle strength: isokinetic (70°/seconds)b. Lower body muscle work: isokinetic (70°/seconds): repeated contractions for 60 secondsb | Not reported Not reported TR (p < 0.05) ns C | – – ↑320 Je | TR > C (p < 0.001) ns between groups TR > C (p < 0.02) |

| Kongsgaard et al., 200420 | 13 COPD: 6 training (TR), 7 control (C) | TR: 48 (4); C: 44 (3) | TR: 71 (1); C: 73 (2) | RCT | TR: 60 minutes: 4 sets of 8 reps (2–3 minutes rest) leg press, knee extension, and knee flexion at 80% of 1 RM | 12 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps MVC: isometricb Knee extension: isokinetic (60°/seconds)b Knee extension: isokinetic (180°/seconds)b 5 RM leg press CSA quadriceps (MRI) | TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (P<0.01) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C | ↑14.7% – ↑17.8% – ↑15.1% – ↑36.5% – ↑4.2% – | TR > C (p < 0.05) TR > C (p < 0.05) TR > C (p < 0.05) TR > C (p < 0.01) ns between groups |

| Hoff et al., 200721 | 12 COPD: 6 training (TR), 6 control (C) | TR: 33 (3); C: 40 (6) | TR: 63 (1); C: 61 (3) | RCT | TR: 4 sets of 5 reps (2 minutes rest) leg press (90° bend knees to straight legs) at 85–90% of 1 RM. Load increased with 2.5 kg until only five reps could be achieved. | 8 weeks (3x/w) | 1RM leg press | TR (p < 0.05) ns C | ↑27.1% – | TR > C (p < 0.05) |

| O’Shea et al., 200722 | 44 COPD: 20 training (TR), 24 control (C) | TR: 49 (25); C: 52 (22) | TR: 67 (7); C: 68 (10) | RCT | TR: 3 sets of 8–12 RM against elastic bands of increasing resistance. Exercises: standing hip abduction, simulated lifting, sit-to-stand, seated row, lunges and chest press. Resistance level was increased when 3 sets of 12 reps were achieved. | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extensor strength: isometricc Hip abductor strength: isometricc | Not reported Not reported | – – | TR > C (p < 0.01) ns between groups |

| Houchen et al., 201123 | 43 COPD | COPD: 46 (21) | COPD: 68 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 3 sets of 8 reps leg extension and leg curls on weight machines at 60–70% of 1 RM (progressively increased if RPE scores went down) + step up and sit to stand exercises (3 sets of 8 reps) | 7 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isometricb | p < 0.001 | ↑22.8% | – |

| Menon et al., 2012a24 | 12 COPD, 7 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 46 (6); HC: 103 (6) | COPD: 67 (2); HC: 67 (2) | Non-controlled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: 30 minutes of bilateral, lower limb, high intensity isokinetic resistance training on an isokinetic dynamometer (5 sets of 30 maximal isokinetic knee contractions at angular velocity of 180°/second) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isometric peak torqueb Quadriceps concentric strength: isokinetic peak torqueb Thigh lean mass (DEXA) | COPD (p = 0.002) HC (p = 0.046) COPD (p = 0.001) ns HC COPD (p = 0.003) HC (p = 0.004) | ↑13.2% ↑10.1% ↑25.2% – ↑7.3% ↑5.1% | Not reported Not reported Not reported |

| Menon et al., 2012b25 | 45 COPD, 19 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 47 (19); HC: 107 (22) | COPD: 68 (8); HC: 66 (5) | Noncontrolled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: 30 minutes of bilateral, lower limb, high intensity isokinetic resistance training on an isokinetic dynamometer (5 sets of 30 maximal isokinetic knee contractions at angular velocity of 180°/seconds) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps MVC: isometricb Thigh lean mass (DEXA) Rectus femoris CSA (Ultrasound) Quadriceps muscle thickness (Ultrasound) | COPD (p < 0.0001) HC (p = 0.024) COPD (p < 0.0001) HC (p < 0.001) COPD (p < 0.0001) HC (p < 0.0001) COPD (p < 0.0001) HC (p < 0.001) | ↑20.0% ↑11.3% ↑5.7% ↑5.4% ↑21.8% ↑19.5% ↑12.1% ↑10.9% | Not reported Not reported Not reported Not reported |

| Ricci-Vitor et al., 201326 | 13 COPD | COPD: 48 (12) | COPD: 67 (7) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 60 minutes: 3 sets of 10 reps (2–3 minutes rest) lower limb (knee flexion and extension on leg bend and leg extension equipment) and upper limb strength at 60% of 1 RM (progressed to 80% of 1 RM) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extension MVC: isometrica Knee flexion MVC: isometrica | ns p = 0.023 | – ↑11.4% | – – |

| Ramos et al., 201427 | 34 COPD: 17 conventional training (CT), 17 elastic tubing (ET) | CT: 1.3 (1-1.4) L; ET: 1.1 (1-1.5) L (Absolute values + median and IQR) | CT: 66 (61-68); ET: 67 (60-69) (median and IQR) | RCT | CT: 60 minutes: 3 sets of 10 reps knee flexion and extension, shoulder abduction and flexion, elbow flexion on weight machines at 60% of 1 RM (progressed to 80% of 1 RM) ET: 60 minutes: 2 to 7 sets (2–3 minutes rest), intensity based on a fatigue resistance test (load increased by adding sets) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extension MVC: isometrica Knee flexion MVC: isometrica | CT (p < 0.001) ET (p < 0.001) CT (p < 0.001) ET (p < 0.001) | ↑18.4% ↑13.2% ↑16.5% ↑19.0% | ns between groupsd ns between groupsd |

| Nyberg et al., 201528 | 40 COPD: 20 training (TR), 20 control (C) | TR: 59 (11); C: 55 (15) | TR: 69 (5); C: 68 (6) | RCT | TR: 60 minutes: 2 sets of 25 reps (1 minute rest) elastic theraband exercises upper and lower limb muscles at 25 RM. Resistance level increased by increasing tension of elastic band if patients scores < 4 on Borg and performs > 20 reps. | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extensor strength: isokineticb Knee extensor endurance: isokinetic total work (30 repetitions)b | TR (p < 0.05) ns C TR (p < 0.05) ns C | ↑8% – ↑11.5% – | TR > C (p = 0.003) TR > C (p = 0.018) |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RM: repetition maximum; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; RPE: rate of perceived exertion; MVC: maximum voluntary contraction; CSA: cross-sectional area; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; DEXA: dual energy x-ray absorptiometry.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer, for example, Biodex.

cMeasured via hand-held dynamometer.

dBetween groups difference based on post training value.

eOnly absolute values available.

Table 4.

Combined aerobic and resistance training.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups post training | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Troosters et al., 200029 | 62 COPD: 34 training (TR), 28 control (C) | TR: 41 (16); C: 43 (12) | TR: 60 (9); C: 63 (7) | RCT | TR: 90 minutes: cycling (60% of Wmax, progressed up to 80%), treadmill walking (60% of max walking speed at 6MWT, progressed up to 80%), stair climbing (2 minutes–1 to 3 reps), arm cranking (2 minutes–1 to 3 reps), peripheral muscle training of triceps, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis and quadriceps (3 x 10 reps at 60% of 1 RM) | 24 weeks: (3x/w first 12 weeks, 2x/w last 12 weeks) | Quadriceps strength: isometricb | Not reported | – | TR > C (p = 0.004) |

| Gosselin et al., 200330 | 7 COPD | COPD: 62 (6) | COPD: 61 (3) | Single group pre post-test | TR: cycling (45 minutes based on heart rate at AT), gymnastics (60 minutes weight training), relaxation (30 minutes), walking (2 hours country walking with 45 minutes at heart rate AT) | 3 weeks (5x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometrica | ns | – | – |

| Franssen et al., 200431 | 50 COPD; 36 healthy controls (HC) | COPD: 39 (16); HC: 111 (17) | COPD: 64 (9); HC: 61 (6) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | TR: submaximal cycling at 50–60% of Wmax for 20 minutes, treadmill for 20 minutes just below symptom limited rate, 30 minutes gymnastics, unsupported arm exercise (10 x 1 minute), strength upper and lower limbs (individual approach) | 8 weeks (5x/w) | Quadriceps strenght: isokinetic (90°/s)b | p < 0.05 | ↑30% | – |

| Kamahara et al., 200432 | 10 COPD | COPD: 40 (21) | COPD: 70 (5) | Single group pre post-test | 3 sets of 4 exercises in circuit. Calf raise (10 reps), abdominals (6 reps), upper limbs (20 reps) and 2 minutes cycle ergometer at 80% of peak VO2 | 2 weeks (5x/w) | Isokinetic hamstring strength: right leg (60°/s)b Isokinetic hamstring strength: left leg (60°/s)b Isokinetic quadriceps strength: right leg (60°/seconds)b Isokinetic quadriceps strength: left leg (60°/seconds)b | p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.05 p < 0.05 | ↑20.2% ↑42.1% ↑27.7% ↑16% | – – – – |

| Franssen et al., 200533 | 87 COPD: 59 Non-FFM depleted (NF), 28 FFM-depleted (F) 35 healthy controls (HC) | COPD NF: 37 (2); COPD F: 31 (3); HC: 111 (3) | COPD NF: 63 (1); COPD F: 62 (2) HC: 62 (1) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | TR: submaximal cycling at 50–60% of Wmax for 20 minutes (2x/d), treadmill for 20 minutes just below symptom limited rate, 30 minutes gymnastics, unsupported arm exercise (10 x 1 minute), strength upper and lower limbs (individual approach) | 8 weeks (5x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isokinetic (90°/seconds)b Quadriceps endurance: isokinetic: 15 maximal contractions (90°/second)b | All COPD (p < 0.01) All COPD (p < 0.01) | ↑20% ↑20% | – – |

| Spruit et al., 200534 | 78 COPD | COPD: 45 (18) | COPD: 65 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: ergometry cycling at 60% of Wpeak for 10 minutes (progressed to 25 minutes at 75% of Wpeak), treadmill walking (60% of average speed at 6MWT for 10 minutes, progressed to 25 minutes), arm cranking (4 minutes progressed to 9 minutes), dynamic strengthening exercises quadriceps, pectoral muscles, triceps brachia (70% of 1 RM 3 x 8 reps, every week load was increased with 5% of 1 RM) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isometricb | p = 0.002 | ↑16% | – |

| McKeough et al., 200635 | 10 COPD, 10 healthy controls (HC) | COPD: 42 (5); HC: 103 (4) | COPD: 71 (2); HC: 68 (3) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | TR: supervised leg cycling (40–60% of Wpeak for 20 minutes, progressed up to 80%), walking (80% of speed 6MWT for 20 minutes, progressed to 30 minutes) and leg strength training (2 sets 8–10 reps at 70% of 1 RM, progressed to 3 sets at 80% of 1 RM) | 8 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps MVC: isometricd CSA quadriceps (MRI) | p = 0.007 p = 0.03 | ↑32% ↑7% | – – |

| Bolton et al., 200736 | 40 COPD, 18 healthy age and gender-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 37 (16); HC: 106 (16) | COPD: 62 (9); HC: 61 (4) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | TR: 20 minutes submaximal cycling at 50% Wpeak (2x/d), 20 minutes treadmill, 30 minutes gymnastics, unsupported arm exercise training (10 x 1 minute) | 8 weeks (5x/w) | Quadriceps peak torque: isokinetic (90°/second)b | p = 0.018 | ↑15.2% | – |

| Skumlien et al., 200737 | 40 COPD: 20 training (TR), 20 control (C) | TR: 45 (11); C: 46 (10) | TR: 63 (8); C: 65 (7) | Non-randomized controlled trial | TR: 45 minutes: treadmill at 64–83% of Wpeak for 18–21 minutes, resistance training 2–3 sets legs at 62–70% of 15 RM and arms at 82–96% of 15 RM. | 4 weeks (5x/w) | Leg press: MVC: isometrica 15 RM seated leg press | TR (p < 0.0005) ns C TR (p < 0.0005) ns C | ↑15% ↑16 kgf | TR > C (p < 0.05) TR > C (p < 0.05) |

| Pitta et al., 200838 | 29 COPD | COPD: 46 (16) | COPD: 67 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 90 minutes: cycling at 60% of Wmax (progressed up to 85%), walking at 75% of average walking speed 6MWT (progressed up to 110%), strength training lower (quadriceps) and upper (pectoralis, triceps) extremities (3 sets of 8 reps at 70% of 1 RM, progressed to 121%), arm cranking (1–3 sets of 2 minutes) and stair climbing (1–3 sets of 1–3 minutes). | 24 weeks: first 12 weeks (3x/w), second 12 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps muscle strength: isometricb | p < 0.05 | ↑12.8% | – |

| Van Wetering et al., 200939 | 175 COPD: 87 training (TR), 88 control (C) | TR: 58 (17); C: 60 (15) | TR: 66 (9); C: 67 (9) | RCT | TR: cycling and walking + 4 upper and lower extremity strength and endurance exercises | 16 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps peak torque: isometric | Not reported | – | ns between groups |

| Evans et al., 201040 | 44 COPD | COPD: 43 (15) | COPD: 69 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 120 minutes: walking at 85% of VO2 peak of ISWT (progressed based on Borg 3–6), peripheral muscle exercises upper and lower limbs (8 exercises: 10 reps) | 7 weeks (2x/w walking, 3x/w strength) | Quadriceps peak torque: isometricb | ns | – | – |

| Arizono et al., 201141 | 57 COPD | COPD: 44 (16) | COPD: 63 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 60 minutes supervised: cycle ergometer for 20 minutes at 80% of Wpeak, strength training upper and lower body (11 exercises: step-ups, sit-to-stand, leg press, knee extensions, trunk flexion, trunk rotation, pelvic tilt, lying triceps extension, dumbbell bench press, dumbbell fly, shoulder shrugs) Unsupervised: walking (20 minutes at Borg dyspnea intensity 4 and 5) | 10 weeks (2x/w supervised, 3x/w unsupervised) | Knee extension strength: isokineticb | p < 0.01 | ↑8.3% | – |

| Kozu et al., 201142 | 45 COPD | COPD: 45 (12) | COPD: 67 (5) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 40–50 minutes: cycling at 50% of Wpeak for 5–10 minutes progressed to 20 minutes, repetitive bilateral shoulder flexion and abduction with light weights (2 minutes), strength training: free weights, 1 set of 10 reps progressed to 3 sets. | 8 weeks (2x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isometricc Quadriceps strength (% bodyweight)c | p < 0.01 p < 0.01 | ↑23.5% ↑23.3% | – – |

| Probst et al., 201143 | 40 COPD: 20 low intensity (L), 20 high intensity (H) | L: 39 (14); H: 40 (13) | L: 65 (10); H: 67 (7) | RCT | L: 60 minutes: 5 sets of exercises: breathing exercises, strengthening of the abdominal muscles, calisthenics (1 set = 12 different exercises, 15 reps). Increase intensity by more difficult execution of exercises H: 60 minutes: cycling at 60% of Wmax, walking at 75% of average walking speed based on 6MWT (progression based on Borg 4–6) and strength training of quadriceps, biceps and triceps at 70% of 1 RM | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 1 RM quadriceps: leg extension | ns L H (p = 0.02) | – ↑33.9% | H > L (p = 0.04) |

| Burtin et al., 201244 | 46 COPD: 29 contractile fatigue (CF), 17 no contractile fatigue (NCF) | All COPD: 42 (13); CF: 41 (13); NCF: 44 (14) | All COPD: 64 (8); CF: 63 (7); NCF: 66 (9) | Non-controlled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: treadmill walking at 75% of mean walking speed at 6MWT for 10 minutes progressed to 16 minutes, cycling at 60–70% of Wmax for 10 minutes progressed to 16 minutes, leg press (3 sets of 8 reps at 70% of 1 RM progressed based on Borg 4–6, stair climbing (2 steps up–2 steps down) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps muscle strength: isometrica | All COPD (p = 0.03) | ↑7.0% | ns between groups |

| Gouzi et al., 201345 | 24 COPD 24 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 46 (18); HC: 106 (13) | COPD: 61 (8); HC: 62 (6) | Non-controlled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: 45 minutes endurance exercise at heart rate corresponding to the ventilatory or dyspnea threshold. Every two sessions: 30 minutes of resistance training at 40% of 1 RM. | 6 weeks (3–4x/w) | Quadriceps muscle strength: isometrica Quadriceps endurance: time isometric contraction at 30% of MVC at a rate of 10 contractions/minute until exhaustiona | COPD (p < 0.001) HC (p < 0.001) COPD (p < 0.001) HC (p < 0.001) | ↑g ↑g ↑44.5% ↑98.2% | ns between groups HC > COPD (p < 0.05) |

| Chigira et al., 201446 | 36 COPD: 18 one monthly session (M), 18 one weekly session (W) | M: 50 (20); W: 40 (17) | M: 67 (7); W: 65 (5) | Nonrandomized controlled trial | TR: upper limb: anterior and posterior arm raises with weights, lower limb: tiptoe standing, sit-to-stand exercises, stepping (all with free weights 0,5–2 kg for 20–50 reps), free walking training | 12 weeks (1x/w or 1x/m) | Quadriceps MVC: isometrica | Not reported | – | W > M (p < 0.01) |

| Greulich et al., 201447 | 34 COPD: 20 individualized training (IT), 14 non-individualized training (NIT) | IT: 62 (20); NIT: 68 (20) | IT: 65 (9); NIT: 66 (9) | RCT | IT: 2 x 3 minutes cycling at RPE 13, 3 sets of 25 reps thigh muscles, lateral hip and trunk stabilizers, anterior shoulder muscles, rotator cuff muscles, upper extremities muscles, dorsal trunk and scapular stabilizer at 30% of maximal muscle strength (progressed to 2–6 sets of 8–15 reps at 40–70% of 1 RM) NIT: walking and climbing stairs, ball games, resistance training with dumbbells and elastic tubes (intensity is patient regulated) | 12 weeks (1x/w) | CSA m. rectus femoris (ultrasound) | IT (p = 0.049) ns NIT | ↑8.6% – | ns between groups |

| Jacome & Marques, 201448 | 26 COPD | COPD: 84 (6) | COPD: 68 (10) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 60 minutes: walking at 60–80% of average speed at 6MWT for 20 minutes (progression based on Borg 4–6), strength training upper and lower limb: 7 exercises at 50–85% of 10 RM (2 sets of 10 reps) for 15 minutes (progression of load when 2 additional reps could be performed on 2 consecutive session and based on Borg 4–6), balance training (static and dynamic exercises) for 5 minutes. | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 10 RM knee extension | p = 0.001 | ↑63.4% | – |

| Costes et al., 201549 | 23 COPD: 15 normoxemic (N), 8 hypoxemic (H) | N: 42 (3); H: 34 (4) | N: 61 (2); H: 60 (2) | Noncontrolled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: bicycle exercise (20–30 minutes), treadmill exercise (10–15 minutes) at intensity heart rate at VT or at 60% of Wpeak (increase by 5 W when HR decreased with more than 5 beats/minute on 2 consecutive sessions), resistance exercise upper and lower limb (3 sets of 8–12 reps at 60% of maximal isometric force, progressed to 85%) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps muscle strength: isometrica | N (p < 0.05) H (p < 0.05) | ↑19.1% ↑31.7% | ns between groupse ns between groupse |

| Jones et al., 201550 | 86 COPD: 43 sarcopenic (S), 43 non-sarcopenic (NS) | COPD S: 44 (37 – 50); COPD NS: 45 (39 – 51) (Median and IQR) | COPD S: 73 (8); COPD NS: 72 (11) | Noncontrolled intervention study with subgroup analyses. Same intervention for both groups. | TR: 60 minutes: walking at 80% of predicted VO2 based on ISWT, 10 minute cycling, strength: lower limb (2 sets of 10 leg press reps at 60% of 1 RM, sit-to-stand, knee lifts/extensions, hip abduction) and upper limb (biceps curls, shoulder press and upright row) | 8 weeks (2x/w supervised + 1x/w home) | MVC quadriceps: isometrica | ns NS S (p < 0.05) | – ↑7% | ns between groups |

| Marques et al., 2015a51 | 22 COPD | COPD: 72 (22) | COPD: 68 (12) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 60 minutes: walking at 60–80% of average speed at 6MWT for 20 minutes (progression based on Borg 4–6), strength upper and lower limb: at 50– 85% of 10 RM for 15 minutes (2 sets of 10 reps) progressed when 2 additional reps could be performed in 2 consecutive sessions, balance training (static and dynamic exercises) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 10 RM quadriceps: leg extension | p = 0.001 | ↑96.9% | – |

| Marques et al., 2015b52 | 9 COPD | COPD: 69 (25) | COPD: 70 (8) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 60 minutes: 20 minutes walking at 60–80% of average speed at 6WMT, resistance training: 15 minutes of elastic bands and free weights (7 exercises upper and lower limbs, 2 sets of 10 reps at 50–85% of 10 RM), 5 minutes balance training | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 10 RM quadriceps: leg extension | p = 0.002 | ↑91.2% | – |

| Pothirat et al., 201553 | 30 COPD | COPD: 45 (11) | COPD: 69 (9) | Single group pre post-test | TR: 35–40 minute: 3 sets at 100% of 10 RM of upper and lower limbs (not specified) using weight lifting and resistive loading (progressed with 10 reps and 2 sets), walking at 40–45% of heart rate reserve without exceeding Borg 6 for 15–20 minutes progressed up to 35–40 min. | 8 weeks (2x/w) | 10 RM quadriceps | p < 0.001 | ↑71.0% | – |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RM: repetition maximum; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; FFM: fat free mass; ISWT; incremental shuttle walk test; MVC: maximum voluntary contraction; Wpeak/max: peak/maximal workload; 6MWT: 6-minute walking test; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; AT/VT: anaerobic/ventilatory threshold; CSA: cross-sectional area; RPE: rate of perceived exertion.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer, for example, Biodex.

cMeasured via hand-held dynamometer.

dMeasured via pushing against force platform.

eBetween group difference based on post training value.

fOnly absolute values available.

gData not reported.

Table 5.

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and magnetic stimulation training.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups post training | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) | ||||||||||

| Bourjeily-Habr et al., 200254 | 18 COPD: 9 NMES, 9 control (C) | NMES: 36 (4), C: 41 (4) | NMES: 59 (2), C: 62 (2) | RCT | NMES: 50 Hz for 200 ms every 1500 ms at initial 55 mA–120 mA (intensity increased 5 mA/week) for 20 minutes each limb (quadriceps, hamstrings, and calf muscles). C: no active electrical stimulation | 6 weeks (3x/w) | Maximal quadriceps strength: isokineticb Maximal hamstring strength: isokineticb | NMES (p = 0.004) ns C NMES (p = 0.02) ns C | ↑39% – ↑33.9% – | NMES > C (p = 0.046) NMES > C (p = 0.038) |

| Neder et al., 200255 | 15 COPD: 9 NMES, 6 control first 6 weeks + NMES last 6 weeks (C) | NMES: 38 (10); C: 40 (13) | NMES: 67 (8); C: 65 (5) | RCT | NMES: 50 Hz, pulse width 300–400 µs, 2 seconds on–18 s off (progressed to 10 s on –30 s off) at 10–20 mA (progressed to 100 mA) for 15 minutes each leg (progressed to 30 minutes), quadriceps femoris muscle C: receive NMES after a control period | 6 weeks (5x/w) | Maximal quadriceps strength: isokinetic (70°/second)b Quadriceps strength: isometricb Quadriceps endurance isokinetic: 1 minute maximal number of contractions at angular velocity 70°/second (fatigue index)b | C last 6 weeks (p < 0.05) Not reported NMES ns NMES ns C last 6 weeks C last 6 weeks (p < 0.05) Not reported NMES | ↑e – – – ↓e – | NMES > C (p < 0.05)d ns between groupsd NMES > C (p < 0.05)d |

| Dal Corso et al., 200756 | 17 COPD: assigned to NMES followed by sham or sham followed by NMES | All COPD: 50 (13) | All COPD: 66 (7) | Cross-over RCT (due to no significant effect of treatement sequence all the subjects were seen as a single group) | NMES: 50 Hz, pulse width 400 µs, 2 seconds on–10 seconds off (progressed to 10 seconds on–20 seconds off) at 10 to 25 mA (progressed weekly with 5 mA) for 15 minutes each leg (progressed to 60 minutes), quadriceps femoris muscle. Sham: 10 Hz, pulse width 50 µs at 10 mA for 15 minutes each leg (quadriceps femoris muscle) | 6 weeks (5x/w) | Concentric contraction of quadriceps: isokinetic (60°/second)b Right leg muscle mass (DEXA) | ns ns | – – | – – |

| Napolis et al., 201157 | 30 COPD: assigned to NMES followed by sham or sham followed by NMES | All COPD: 50 (13) | All COPD: 64 (7) | Cross-over RCT | NMES: 50 Hz, 300–400 µs pulse width, 2 seconds on–10 seconds off (progressed to 10 seconds on–20 seconds off) at 15–20 mA (progressed to 60 mA) for 15 minutes each leg (progressed to 60 minutes), quadriceps femoris muscle; Sham: 50 Hz, 200 µs pulse width, 2 seconds on–10 seconds off at 10 mA for 15 minutes each leg (quadriceps femoris muscle) | 6 weeks (5x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isokineticb Quadriceps strength: isometricb | ns NMES ns sham ns NMES ns sham | – – – – | ns between groups Not reported |

| Vivodtzev et al., 201258 | 20 COPD: 12 NMES, 8 sham | NMES: 34 (3) Sham: 30 (4) | NMES: 70 (1) Sham: 68 (3) | RCT | NMES: 50 Hz, 400 µs pulse width, 6 seconds/16 seconds on-off cycle, intensity set at patients tolerance for 35 minutes quadriceps muscle and 25 minutes calf muscle Sham: 5 Hz, 100 µs pulse width | 6 weeks (5x/w) | Quadriceps strength: isometrica Quadriceps endurance: maintain 60% MVC until exhaustion (time to fatigue = time when isometric contraction dropped to 50% MVC)a Midthigh muscle CSA (CT) Calf muscle CSA (CT) | Not reported NMES Not reported sham Not reported NMES Not reported sham Not reported NMES Not reported sham Not reported NMES Not reported sham | ↑11% Not reported ↑37% Not reported ↑6% Not reported ↑6% Not reported | NMES > sham (p < 0.03) NMES > sham (p < 0.03) NMES > sham (p < 0.05) NMES > sham (p < 0.05) |

| Vieira et al., 201459 | 20 COPD: 11 NMES, 9 sham | NMES: 37 (11); Sham: 40 (14) | NMES: 56.3 (11); Sham: 56.4 (13) | RCT | NMES: 50 Hz, 300–400 µs pulse width, 2 seconds on–18 seconds off (progressed to 10 seconds on –30 seconds off) at 15–20 mA (progressed to 100 mA) for 60 minutes twice a day, bilateral quadriceps Sham: no stimulation current | 8 weeks (5x/w) | Thigh circumference (after 4 weeks) | NMES (p < 0.01) ns sham | ↑2.9% – | NMES > sham (p < 0.01)d |

| Maddocks et al., 201660 | 52 COPD: 25 NMES, 27 sham | NMES: 31 (11); Sham: 31 (13) | NMES: 70 (11) Sham: 69 (9) | RCT | NMES: 50 Hz, 350 µs pulse width, 2s/15 seconds on–off (progressed to 10 s on–15 s off) at 0–120 mA (progressed based on patients tolerance) for 30 minutes, bilateral quadriceps muscle Sham: 0–20 mA | 6 weeks (7x/w) | Quadriceps unpotentiated twitch (adjusted for baseline) Quadriceps strength: isometrica Rectus femoris CSA (ultrasound) | NMES (p < 0.05) ns sham NMES (p < 0.05) ns sham NMES (p < 0.05) ns sham | ↑14% – ↑14.8% – ↑19.7% – | NMES > sham (p = 0.045) NMES > sham (p = 0.028) NMES > sham (p = 0.003) |

| Magnetic stimulation training (MST) | ||||||||||

| Bustamante et al., 201061 | 18 COPD: 10 MST, 8 control (C) | MST: 30 (7) C: 35 (8) | MST: 61 (6) C: 62 (8) | RCT | MST: 15 Hz, 2 seconds on, 4 seconds off at intensity 40% (increased by 2–3% every session) for 15 minutes each thigh C: no intervention | 8 weeks (3x/w) | MVC quadriceps: isometrica Quadriceps endurance isometric: maximal sustainable time for leg extensions of the dominant leg bearing 10% of MVC (12 contractions per minute)a Unpotentiated twitch quadriceps | MST (p = 0.005) ns C MST (p = 0.05) ns C ns MST ns C | ↑17.5% – ↑44% – – – | Not reported Not reported Not reported |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RM: repetition maximum; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; MVC: maximum voluntary contraction; CSA: cross-sectional area; CT: computed tomography; DEXA: dual energy x-ray absorptiometry.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer, for example, Biodex.

cMeasured via hand-held dynamometer.

dBetween groups difference based on post training value.

eData not reported.

Table 6.

Other training modalities.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups post training | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-intensity interval training (HIIT) | ||||||||||

| Bronstad et al., 201262 | 7 COPD 5 healthy, age-matched controls (HC) | COPD: 46 (10); HC: 93 (14) | COPD: 68 (7); HC: 70 (5) | Single group pre post-test (HC only baseline) | Knee-extensor protocol: 5 minutes warm up without load, 4 intervals of 4 minutes at 90% of peak WR, 2 minutes active unloaded kicking (60 kicks a minute). Legs trained separately. | 6 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps endurance: peak worke Quadriceps muscle mass (MRI) | p < 0.001 ns | ↑37% – | – – |

| Whole-body vibration training | ||||||||||

| Pleguezuelos et al., 201363 | 51 COPD: 26 whole body vibration training (WBVT), 25 control (C) | WBVT: 37 (12); C: 32 (7) | WBVT: 68 (9); C: 71 (8) | RCT | WBVT: squatting position (30° hip flexion, 55° knee flexion), 6 series of 4 x 30-s repetitions at frequency 35 Hz and amplitude 2 mm with 60 seconds rest in between sets. Intensity set via Borg scale. | 6 weeks (3x/w) | Right leg: isokinetic knee extension (60°/s)b Right leg: isokinetic knee extension (180°/s)b Right leg: isokinetic knee flexion (60°/s)b Right leg: isokinetic knee flexion (180°/s)b Left leg: isokinetic knee extension (60°/s)b Left leg: isokinetic knee extension (180°/s)b Left leg: isokinetic knee flexion (60°/s)b Left leg: isokinetic knee flexion (180°/s)b | ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups ns both groups | – – – – – – – – | ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups ns between groups |

| Salhi et al., 201564 | 51 COPD: 26 whole-body vibration training (WBVT), 25 resistance training (RT) | WBVT: 38 (28– 45); RT: 39 (29– 45) (Median and IQR) | WBVT: 58 (55– 73) RT: 63 (57–68) (Median and IQR) | RCT | WBVT: 27 hz, peak-to-peak amp (2 mm), 30 seconds–1 minute, reps 1–3, 4 lower body ex (high squat, deep squat, wide-stance squat and lunge), 4 upper body ex (front raise, bent over lateral, biceps curl and cross-over) + 15 minutes aerobic exercise RT: 3 sets of 10 reps quadriceps, hamstrings, deltoid, biceps brachii, triceps brachii, pectoral muscles at 70% of 1 RM (progressed based on Borg 4-6) + 15 minutes aerobic exercise (After 6w: dynamic strength exercises) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Knee extension strength: isometricc | ns WBVT RT (p = 0.009) | – ↑10.5% | ns between groupse |

| Water-based training | ||||||||||

| Lotshaw et al., 200765 | 40 COPD: 20 water-based training (WT), 20 land-based training (LT) | WT: 47 (17); LT: 44 (16) | WT: 65 (14); LT: 71 (7) | Retrospective non-randomized controlled trial | WT: 90 minutes: aerobic exercise (guided lane walking for 30 min at 60–80% of predicted HR, Borg 11–14, BP < 200/100 mmHg, saturation > 90%, resistance exercise with floatation devices (2 sets of 10 reps knee extension, squats, stair climbing, hip flexion, hamstring curls, toe raises, hamstring and gastrocnemius stretch, shoulder flexion, abduction, scapular protraction and retraction, active neck exercises and scapular stretches); LT: aerobic exercise (treadmill and stationary bicycle at same intensity as WT, resistance exercise (2 sets of 10 reps of same exercises as WT at 100% of 6 RM after 6 weeks) | 6 weeks (3/w) | 6 RM knee extension 6 RM hip flexion | WT (p = 0.008) LT (p = 0.008) WT (p = 0.008) LT (p=0.008) | ↑92.7% ↑68.0% ↑85.8% ↑82.7% | ns between groups ns between groups |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RM: repetition maximum; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; HR: heart rate.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer, for example, Biodex.

cMeasured via hand-held dynamometer.

dIncremental knee-extension protocol.

eBetween groups difference based on post training value.

Table 7.

Comparing studies.

| Author, year of publication | Number of patients (n) | Mean (SD) FEV1 (%predicted) | Mean (SD) age (y) | Study design | Study intervention | Study duration | Outcome measures | Significant difference within groups post training | Significant change pre to post (% baseline) | Significant difference between groups (% change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic and resistance training | ||||||||||

| Bernard et al., 199966 | 36 COPD: 15 aerobic training (AT), 21 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 39 (12); CT: 45 (15) | AT: 67 (9); CT: 64 (7) | RCT | AT: 30 minutes ergocycle at 80% of Wpeak. CT: AT + RT: 2 sets of 10 reps seated press, elbow flexion and shoulder abduction, leg press, bilateral knee extension, at 60% of 1 RM (progressed to 3 sets of 10 reps at 80% of 1 RM) | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Bilateral thigh MCSA (CT) 1 RM bilateral knee extension | ns AT CT (p < 0.0001) AT (p < 0.005) CT (p < 0.0001) | – ↑8% ↑7.8% ↑20% | CT > AT (p < 0.05) CT > AT (p < 0.05) |

| Ortega et al., 200267 | 47 COPD: 17 resistance training (RT), 16 aerobic training (AT), 14 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | RT: 40 (14); AT: 41 (11); CT: 33 (12) | RT: 66 (6); AT: 66 (8); CT: 60 (9) | RCT | AT: 40 min ergocycle at 70% of Wpeak; RT: 4 sets of 6–8 reps chest pull, butterfly, neck press, leg flexion, leg extension at 70–85% of 1 RM; CT: 2 set of 6–8 reps at 70–85% of 1 RM + 20 minutes ergocycle at 70% of Wpeak | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 1 RM leg extension 1 RM leg flexion | RT (p < 0.05) AT (p < 0.05) CT (p < 0.05) RT (p < 0.05) AT (p < 0.05) CT (p < 0.05) | ↑52.8% ↑20.5% ↑52.8% ↑106.7% ↑33.3% ↑88.2% | RT > AT (p<0.001) CT > AT (p < 0.01) RT > AT (p < 0.001) CT > AT (p < 0.01) |

| Spruit et al., 200268 | 30 COPD: 16 aerobic training (AT), 14 resistance training (RT) | AT: 41 (20); RT: 40 (18) | AT: 63 (8); RT: 64 (7) | RCT | AT: 90 minutes: 10 minutes cycling at 30% of Wpeak (progressed to 25 min at 75%), 10 minutes treadmill walking at 60% of average speed 6MWT (progressed to 25 minutes), 4 minutes arm cranking at Borg dyspnea 5 - 6 (progressed to 9 minutes) and 3 min stair climbing (progressed to 6 minutes). RT: 90 minutes: 3 sets of 8 reps quadriceps, pectoralis, triceps at 70% of 1 RM (load was increased with 5% of 1 RM weekly), 3 minutes stair climbing (progressed to 6 minutes), 2 minutes cycling and walking at 40% of Wpeak or averaged speed 6MWT | 12 weeks (3x/w) | Isometric knee extension peak torqueb Maximal isometric knee extension forcec Maximal isometric knee flexion forcec | AT (p < 0.05) RT (p < 0.05) ns AT RT (p < 0.05) AT (p < 0.05) RT (p < 0.05) | ↑42% ↑20% – ↑35% ↑28% ↑31% | AT > RT (p < 0.01) ns between groups ns between groups |

| Mador et al., 200469 | 24 COPD: 13 aerobic training (AT), 11 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 40 (4); CT: 44 (4) | AT: 68 (2); CT: 74 (2) | RCT | AT: 20 min of cycle ergometer at 50% of Wmax (progressed with 10% when patient could cycle for 20 minutes < 5 Borg), 15 minutes treadmill exercise 1.1 to 2.0 mph based on 6MWT with 0% elevation (elevation and speed increased when patient could walk for 15 minutes < 5 Borg). CT: AT + RT: 1 set of 10 reps knee flexion, knee extension, chest press, shoulder abduction, and elbow flexion at 60% of 1 RM (progressed to 3 sets and addition of 5 lb) | 8 weeks (3x/w) | 1 RM quadriceps 1 RM hamstrings | ns AT CT (p < 0.005) ns AT CT (p < 0.03) | – ↑23.6% – ↑26.7% | CT > AT (p < 0.002) ns between groups |

| Panton et al., 200470 | 17 COPD: 8 aerobic training (AT), 9 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 40 (32); CT: 42 (16) | AT: 63 (8); CT: 61 (7) | Non-randomized controlled trial | AT: 30 minutes of arm ergometer, cycle ergometer, Airdyne cycling, treadmill, indoor track walking + 30 minutes chair aerobics. Everything at 50–70% of HRR. CT: AT + RT: 45–60 minutes: 3 sets of 10–12 reps leg press, calf press, seated leg curl, leg extension, chest press, pull down, shoulder press, seated row, crunch, back extension, biceps curl, and triceps extension (when 12 reps could be completed, resistance was increased). | AT: 12 weeks (2x/w); CT: 12 weeks (4x/w) | 1 RM leg extension | ns AT CT (p < 0.05) | – ↑36.5% | CT > AT (p < 0.05)d |

| Phillips et al., 200671 | 19 COPD, 9 aerobic training (AT), 10 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 33 (6); CT: 42 (3) | AT: 70 (2); CT: 71 (1) | RCT | AT: 20 – 40 minutes arm ergometer, treadmill, cycle and stepper (all at 3 MET, RPE < 13 and saturation ≥ 90%), low intensity resistance training with 2 or 3 lb handheld dumbbells (8–10 reps arm curl, lateral torso bend, lateral arm raise, wrist curl, standing triceps extension, and shoulder abduction with arms flexed). Progression: increase with 2–3 reps each session based on RPE < 13, load increased when patient could complete 16–18 reps. CT: AT + RT: chest press, leg press, lat pulldown, cable triceps pushdown, cable triceps curl at 50% of 1 RM (load increased with 5–10% after completion of 10 reps) | 8 weeks (2x/w) | 1 RM leg press | ns AT CT (p < 0.05) | – ↑9% | CT > AT (p < 0.05) |

| Alexander et al., 200872 | 20 COPD: 10 aerobic training (AT), 10 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 39 (15); CT: 30 (13) | AT: 73 (9); CT: 65 (8) | RCT | AT: 20–40 minutes: upper (arm ergometer) and lower limb (treadmill, cycle ergometer, and stepper) at 20–40 bpm above HRrest, breathlessness score 1–5, RPE 11–13 and 3 METs, upper arm strength training at low intensity using handheld dumbbells (1 set of 8–15 reps arm curl, lateral torso bend, lateral arm raise, wrist curl, triceps extension, upright row with 1–10 lbs). Progression: duration was increased before intensity. CT: AT + RT: one set of 12 reps bench press, leg press, pull down, cable triceps pushdown, cable biceps curl at RPE: 11–13 and 50% of 1 RM. Progression: loads increased with 3–5 lb after completion > 12 reps for 2 consecutive sessions | 8 weeks (2x/w) | 1 RM leg press | ns both groups | – | ns between groups |

| Dourado et al., 200973 | 35 COPD: 11 resistance training (RT), 11 combined low intensity training and resistance training (LTRT), 13 low intensity training (LT) | RT: 59 (24); LTRT: 59 (27); LT: 58 (24) | RT: 61 (9); LTRT: 62 (10); LT: 65 (9) | RCT | RT: 60 minutes: 7 exercises on resistance training machines (3 sets of 12 reps, 2 minutes rest, at 50–80% of 1 RM) LT: 60 min: 30 minutes walking, 30 minutes low intensity resistance training with free weights and on parallel bars (3 MET, high reps with low load) LTRT: 60 minutes: 30 minutes RT: 2 sets of 8 reps at 50 – 80% of 1 RM + 30 min LT at half the volume | 12 weeks (3x/w) | 1 RM leg press 1 RM leg extension | RT (p < 0.05) LTRT (p < 0.05) ns LT RT (p < 0.05) LTRT (p < 0.05) ns LT | ↑58.2% ↑48.7% – ↑44.4% ↑21.2% – | RT > LTRT (p < 0.05) LTRT & RT > LT (p < 0.05) RT & LTRT > LT (p < 0.05) |

| Vonbank et al., 201274 | 36 COPD: 12 aerobic training (AT), 12 resistance training (RT), 12 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 58 (19) RT: 58 (16) CT: 51 (20) | AT: 62 (5) RT: 60 (6) CT: 59 (8) | RCT | AT: 20 minutes cycle ergometer at 60% of VO2peak (5 minutes increase every 4 weeks) RT: 2 sets of 8–15 reps lower and upper body (bench press, chest cross, shoulder press, pull downs, biceps curls, triceps extensions, abdominals and leg press) at 8–15 RM (progression: weight increased when > 15 reps were possible and sets increased to 4) CT: AT + RT | 12 weeks (2x/w) | 1 RM leg press | ns AT RT (p < 0.01) CT (p < 0.01) | – ↑39.3% ↑43.3% | RT & CT > AT (p < 0.05) |

| Covey et al., 201475 | 75 COPD: 20 resistance training followed by aerobic training (RTAT), 28 sham training followed by combined aerobic training and resistance training (CT), 27 sham training followed by aerobic training (AT) | RTAT: 42 (10); CT: 41 (10); AT: 39 (9) | RTAT: 68 (6); CT: 68 (8); AT: 68 (7) | RCT | AT: 4 x 5 minutes of stationary cycling at 50% of Wpeak with rest intervals of 2–4 minutes of unloaded cycling (progressed to 80% of Wpeak). RT: 2 sets of 8–10 reps leg press, knee extension, knee flexion, calf raise, hip adduction and hip abduction at 70% of 1 RM (progressed to 3 sets at 80% of 1 RM). CT: AT + RT Sham training: gentle chair exercises | 16 weeks (3x/w) | 1 RM (sum of different muscles) Leg extension endurance: isotonic repetitions at 60% of 1 RM at a cadence of 12 reps per minute until task failure | RTAT (p > 0.001) CT (p < 0.001) AT (p < 0.001) RTAT (p < 0.001) CT (p < 0.001) AT (p < 0.001) | ↑26.7% ↑27.7% ↑13.3% ↑173.8% ↑96.6% ↑46.9% | RTAT > AT (p = 0.006) CT > AT (p = 0.015) ns RTAT vs. CT RTAT > AT (p = 0.001) RTAT > CT (p = 0.05) CT > AT (p = 0.039) |

| Zanini et al., 201576 | 60 COPD: 30 aerobic training (AT), 30 combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | AT: 46 (14); CT: 51 (16) | AT: 72 (8); CT: 69 (6) | RCT | AT: 30–40 minute treadmill or cycle ergometer at 60–70% of HRmax during 6MWT at Borg dyspnea 3–5, upper limb training (arm ergometer and callisthenics with light weights). CT: AT + RT: 2 sets of 7 exercises, 12–20 reps at 60–70% of 1 RM (progressed when 1 or 2 reps more could be performed on 2 consecutive sessions) | 3 weeks (5x/w) | 1 RM leg extension | ns AT CT (p < 0.001) | – ↑30.3% | Not reported |

| NMES and other training modalities | ||||||||||

| Sillen et al., 201477 | 91 COPD: 33 HF-NMES, 29 LF-NMES, 29 resistance training (RT) | HF: 33 (2); LF: 35 (2); RT: 33 (2) | HF: 64 (1); LF: 66 (1); RT: 64 (1) | RCT | NMES: quadriceps and calf stimulation: 18 minutes at maximal tolerable intensity. LF = 15 Hz, HF = 75 Hz. Pulse width 400 µs, 6 seconds on–8 seconds off cycle. RT: 4 sets of 8 reps leg extension and leg press at 70% of 1 RM with 2 minutes rest (progression of load with 5% every 2 weeks) | 8 weeks (5x/w - 2x/d) | Isokinetic quadriceps peak torque (90°/s)b Isokinetic total work: endurance (90°/s)b | HF (p < 0.01) ns LF RT (p < 0.01) HF (p < 0.03) LF (p < 0.03) RT (p < 0.03) | ↑13.7% – ↑8.3% ↑24.0% ↑8.7% ↑16.3% | HF > LF (p = 0.01) ns HF vs RT ns RT vs LF HF > LF (p = 0.03) ns HF vs RT ns RT vs LF |

| Kaymaz et al., 201578 | 50 COPD: 23 NMES, 27 aerobic training (AT) | NMES: 26 (7); AT: 27 (8) | NMES: 63 (10); AT: 63 (7) | Nonrandomized controlled trial | NMES: quadriceps and deltoid stimulation: 50 Hz, 300–400 µs, 15 minutes, maximum tolerable intensity, active strengthening exercises quadriceps AT: treadmill at 60–85% of VO2max for 15 minutes, cycling at 50–75% of Wmax for 15 minutes, active strengthening exercises | NMES: 10 weeks (3x/w) AT: 8 weeks (3x/w) | Quadriceps MMT score right Quadriceps MMT score left | NMES (p < 0.05) AT (p < 0.001) NMES (p < 0.001) AT (p < 0.001) | ↑0.34 pte ↑0.48 pte ↑0.39 pte ↑0.48 pte | ns between groups ns between groups |

| Tasdemir et al., 201579 | 27 COPD: 13 NMES + combined aerobic and resistance training (CT), 14 sham NMES + combined aerobic and resistance training (CT) | NMES: 29 (16-71); Sham: 42.5 (23-66) (median and IQR) | NMES: 62 (8); Sham: 63 (8) | RCT | NMES: quadriceps stimulation for 20 minutes at 50 Hz, 300 µs, 10 s on–20 s off cycle, intensity set at patient’s maximum tolerance. CT: 30 min cycle and treadmill at 80% of HRmax, 2 sets of 10 reps leg extension at 45% of 1 RM (progressed to 3 sets of 10 reps at 70% of 1 RM), 1 set of 10 reps shoulder girdle and elbow muscles with 0.5–1.5 kg. Sham: NMES at 5 Hz + CT | 10 weeks (2x/w) | 1 RM quadriceps | NMES (p < 0.05) Sham (p < 0.05) | ↑18.4% ↑31.0% | ns between groups |

ns: not significant; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RM: repetition maximum; FEV1: forced expired volume in 1 second; pt: points improvement on manual muscle testing scale 0–5; RPE: rate of perceived exertion; MET: metabolic equivalent; HF/LF NMES: high/low frequency neuromuscular electrical stimulation; MCSA: muscle cross-sectional area; CT: computed tomography; Wpeak/max: peak/maximal workload; 6MWT: 6-minute walking test; HRR: heart rate reserve; HR: heart rate; MMT : manual muscle testing.

aMeasured via strain-gauge system.

bMeasured via computerized dynamometer, for example, Biodex.

cMeasured via hand-held dynamometer.

dBetween groups difference based on post training value.

eOnly absolute values available.

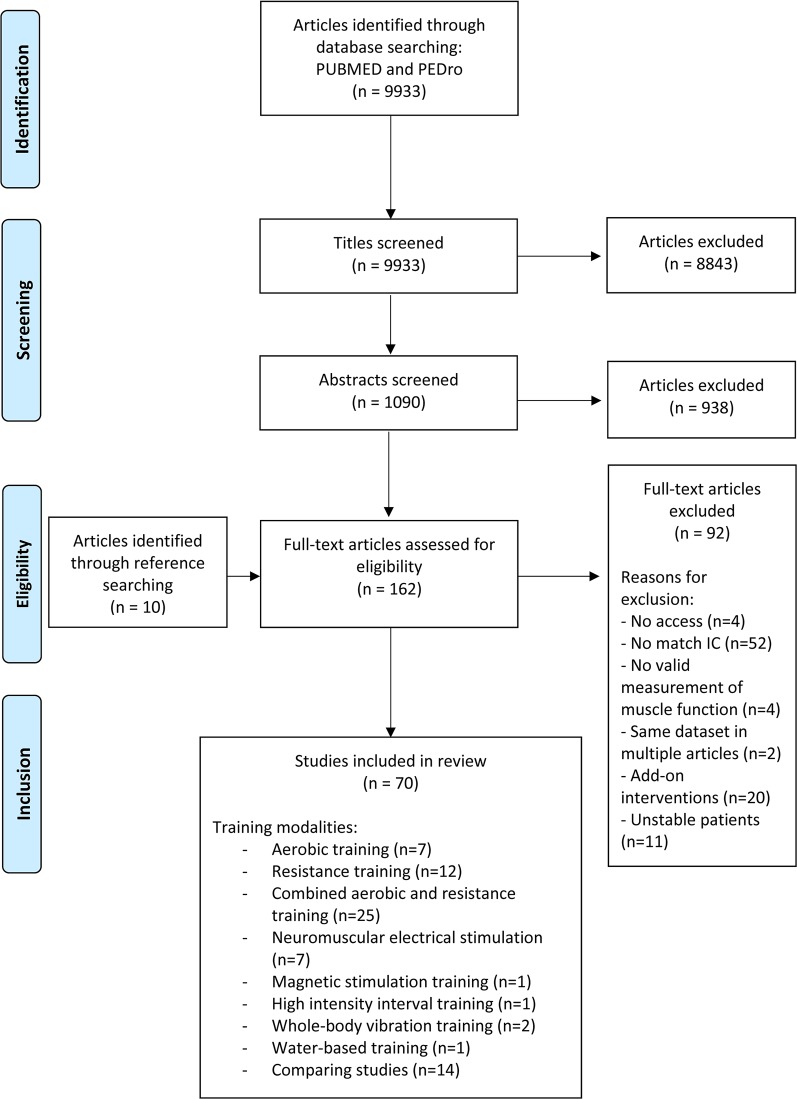

Figure 1.

Study flowchart from identification of articles to final inclusion (based on the Prisma flowchart template). IC: inclusion criteria; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; MST: magnetic stimulation training.

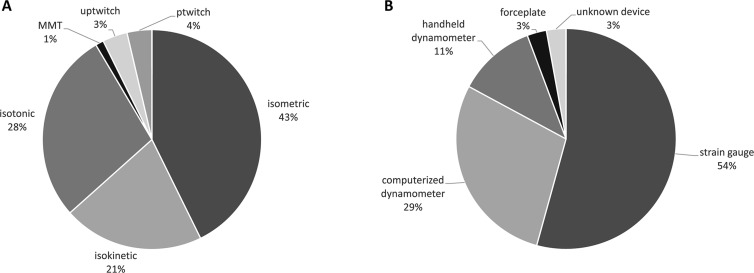

Figure 2.

A) Pie chart depicting an overview of muscle strength measures used across the 70 included studies. B) Pie chart depicting an overview of used isometric strength assessment modalities. MMT: manual muscle testing; uptwitch: unpotentiated twitch; ptwitch: potentiated twitch.

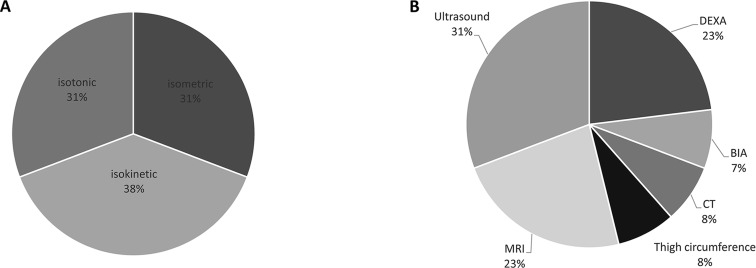

Figure 3.

A) Pie chart depicting an overview of muscle endurance measures used across the 70 included studies. B) Pie chart depicting an overview of muscle mass assessment modalities across the 70 included studies. MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; DEXA: dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; BIA: bioelectrical impedance analysis; CT: computed tomography.

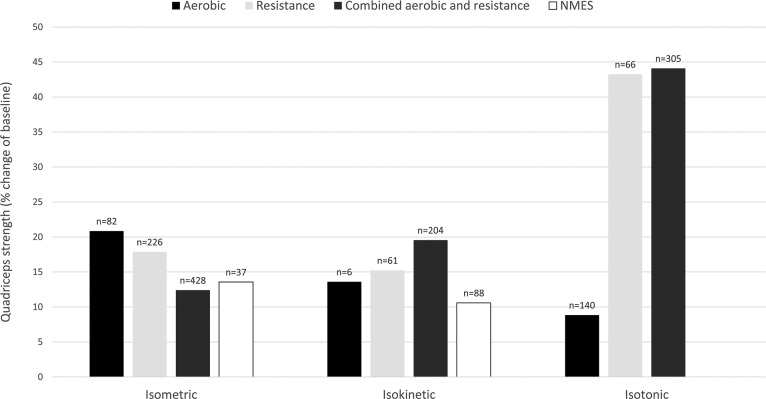

Figure 4.

Effect of aerobic, resistance, combined aerobic and resistance training and NMES on various measures of quadriceps strength in patients with COPD expressed as weighted means of relative change (percentage of baseline). Values on top of the bars are the number of patients with COPD. NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation.

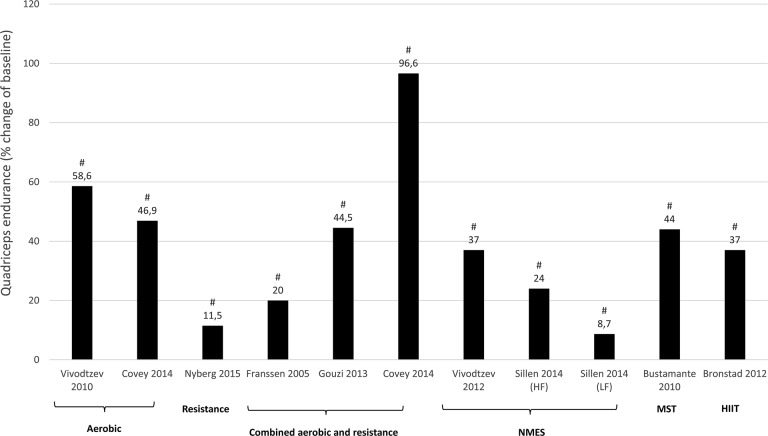

Figure 5.

Effect of different exercise interventions on quadriceps endurance in patients with COPD expressed as mean of relative change (percentage of baseline). NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; HF: high-frequency NMES; LF: low-frequency NMES; HIIT: high-intensity interval training. #Significant change from baseline (within group effect: P < 0.05).

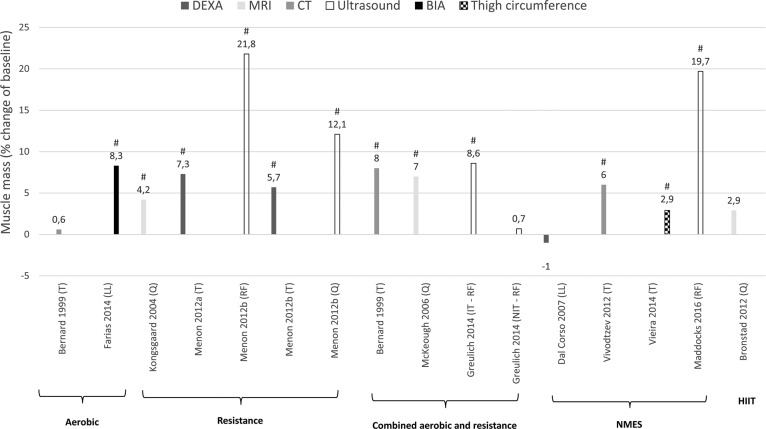

Figure 6.

Effect of different exercise interventions on muscle mass in patients with COPD expressed as mean of relative change (percentage of baseline). T: thigh; LL: lower-limb; Q: quadriceps; RF: rectus femoris; IT: individualized training; NIT: non-individualized training; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; HIIT: high-intensity interval training; DEXA: dual energy x-ray absorptiometry; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography; BIA: bioelectrical impedance analysis. #Significant change from baseline (within group effect: P < 0.05).

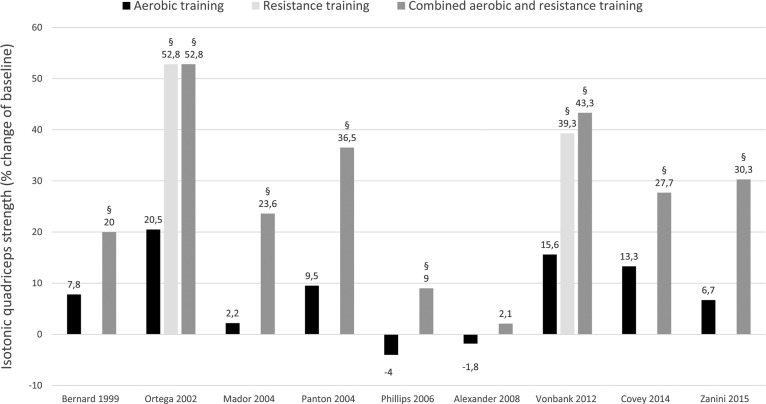

Figure 7.

Effect of different exercise interventions on isotonic quadriceps strength in patients with COPD expressed as mean of relative change (percentage of baseline). §Significantly different with aerobic training (P < 0.05 - between group effect).

(e.g. study 1, with x1 = mean relative change (percentage of baseline) and n1 = number of patients). Subsequently, an overall weighted mean per training modality and per outcome measure was calculated:

Quality assessment

Methodological quality of randomized controlled trials (RCT) or nonrandomized controlled trials were assessed (Table 1). The PEDro scale, based on the Delphi list and “expert consensus,” was used as a tool to assess the quality of the studies.81,82 PEDro scores were obtained from the PEDro database. If a study was not found in the PEDro database, PEDro scores were calculated for that study by two reviewers (JDB and CB). Eleven quality criteria received a “yes” or “no” answer and were summed (criteria 1 is not used in the calculation) to a maximum score of 10 points.82 Studies were considered of “good” to “excellent” quality when scoring ≥6 points on the PEDro scale. Studies scoring ≤5 points were defined as “low” to “fair” quality studies.83 Studies using a single group design with or without a healthy control group following a similar intervention were not assessed.

Table 1.

Assessment of methodological quality of RCTs and non-randomized controlled trials based on the PEDro scoring system. Studies are ranked alphabetically.

| Author, year of publication | Eligibility criteria | Random allocation | Concealed allocation | Baseline comparability | Blind subjects | Blind therapists | Blind assessors | Adequate follow-up | Intention-to- treat analysis | Between-group comparisons | Point estimates and variability | Total score on 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander et al., 200872 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Bernard et al., 199966 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Bourjeily-Habr et al., 200254 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Bustamante et al., 201061 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Chigira et al., 201446 | No | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Clark et al., 199680 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Clark et al., 200019 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Covey et al., 201475 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Dal Corso et al., 200756 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Dourado et al., 200873 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Farias et al., 201417 | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Greulich et al., 201447 | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Hoff et al., 200721 | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Kaymaz et al., 201578 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Kongsgaard et al., 200420 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Maddocks et al., 201660 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Mador et al., 200469 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Napolis et al., 201157 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Neder et al., 200255 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nyberg et al., 201528 | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| O’Shea et al., 200722 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Ortega et al., 200267 | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Panton et al., 200470 | No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Phillips et al., 200671 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Pleguezuelos et al., 201363 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Probst et al., 201143 | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Ramos et al., 201427 | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Salhi et al., 201564 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Sillen et al., 201477 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Simpson et al., 199218 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Skumlien et al., 200737 | Yes | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Spruit et al., 200268 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Tasdemir et al., 201579 | No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Troosters et al., 200029 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Van Wetering et al., 200939 | Yes | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Vieira et al., 201459 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Vivodtzev et al., 201015 | No | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Vivodtzev et al., 201258 | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Vonbank et al., 201274 | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Zanini et al., 201576 | Yes | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

Results

Search results

The study selection process is outlined in Figure 1. We identified 9933 articles with our search strategy. After title screening, 8843 articles were excluded, resulting in 1090 remaining articles for abstract screening. Reference screening of review papers delivered 10 more eligible articles. Finally, 162 full-text articles were screened, of which 92 articles were excluded. The remaining 70 articles (n = 2504 patients with COPD; n = 2124 exercise training, n = 380 control) were established as eligible to be used in our review.

Quality assessment

Pedro scores of RCTs and non-RCTs are given in Table 1. Of the 40 assessed studies, 17 studies scored between 6 and 8 points and are considered to be studies of “good” quality. In all, 23 studies scored ≤ 5 points, with 18 studies scoring 4 or 5 points (“fair” quality), and 5 studies ≤ 3 points which is considered “low” quality. The criteria of concealed allocation, blinding of assessors, adequate follow-up, and intention-to-treat analysis were often not fulfilled. One non-RCT was not assessed because of its retrospective nature.65 The other 29 studies used a single group design with (n = 4) or without (n = 25) a healthy control group that followed a similar intervention (Table 1).

Results per outcome measure

Outcome measures

Muscle strength can be categorized into voluntary strength, that is, isometric, isokinetic, and isotonic strength, and involuntary strength. Isometric strength is defined as a static contraction without a change in muscle length. Isokinetic strength is determined as dynamic strength while maintaining a constant speed. Isotonic strength is defined as dynamic strength with maintaining constant force while changing the length of the muscle. Involuntary strength is assessed by electrically or magnetically stimulating a peripheral nerve, resulting in an unpotentiated twitch (rest) or potentiated twitch (performed seconds after a maximum voluntary contraction). An overview of muscle strength measures used across the 70 included studies is given in Figure 2 (A). Isometric strength measures were used most frequently (43%), followed by isotonic (28%), and isokinetic (21%) strength measures. Manual muscle testing and involuntary strength measures were rarely used. Isometric strength assessment modalities are depicted in Figure 2 (B) and were dominantly performed by strain gauge, followed by computerized dynamometer, handheld dynamometer, force plate, or an unknown device. Used measures of muscle endurance and assessment modalities of muscle mass varied strongly and are depicted in Figure 3.

Results per outcome measure

All studies wherein percentage change from baseline was available or where percentage change from baseline was calculated by the reviewers are presented per outcome measure in Figures 4 –7. Weighted means for changes from baseline for isometric, isokinetic, and isotonic strength are depicted for aerobic, resistance, combined aerobic and resistance training, and neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) in Figure 4. Overall, isometric quadriceps strength increased with 15%, isokinetic quadriceps strength with 17%, and isotonic lower limb strength with 34% (Figure 4). Quadriceps endurance improved with 8.7–96.6% (Figure 5) and quadriceps muscle mass with 4.2–12.1% (Figure 6). Comparisons in isotonic lower limb strength between aerobic, resistance and combined aerobic, and resistance training are presented in Figure 7.

Results per training modality

Different exercise training modalities were used to investigate the effect of exercise-based therapy on muscle function and muscle mass (Figure 1). A detailed overview is given in the following sections. More information on the characteristics of the different studies grouped per training modality are given in Tables 2–7.

Aerobic training (Table 2)

Muscle strength

Isometric strength: Four studies showed an increase of 10–21% in isometric quadriceps strength after training.11,12,14,15 In contrast, one study reported no significant change in isometric quadriceps strength.16 Significant between-group differences in the change in isometric quadriceps strength were reported in favor of the training group compared to the nonexercising COPD control group.15

Isokinetic strength: One study measured isokinetic quadriceps strength which increased with 13.6% after training in patients.13

Isotonic strength: Isotonic hamstring muscle strength was measured by 1RM leg curl and increased with 50% after training, while in the COPD control group no significant change was reported.17 The difference between groups was however not significant.17

Involuntary strength: Involuntary contraction of the quadriceps muscle produced by magnetic stimulation of the nervus femoralis and measured as potentiated and unpotentiated twitch showed a significant increase of 8.8% and 9.7% after training, respectively.12 In contrast, another study reported a nonsignificant increase in potentiated twitch after training.14

Muscle endurance

Isometric endurance: A study showed a nonsignificant increase in isometric knee extension endurance, measured as holding an isometric contraction at 50% of maximum until exhaustion.11

Isokinetic endurance: An increase of 58.6% in quadriceps muscle endurance, measured as dynamic repeated leg extension with weights corresponding to 30% MVC until exhaustion, was reported in one study. This change was significantly greater compared to the nonexercising control group.15

Muscle mass

Resistance training (Table 3)

Muscle strength

Isometric strength: Six studies showed a significant increase of 13.2–25.4% in isometric quadriceps strength after resistance training.17,18,20,23–25,27 Two studies also reported a significant difference in isometric quadriceps strength between training group and control group in favor of training.20,22 One study, however, did not report a significant increase in isometric quadriceps muscle strength after training.26 Two studies measured isometric hamstrings muscle strength, all showing a significant increase of 11.4–19.0%.27,26 Isometric hip abductor strength was not significantly different after training between the training group and the control group22. The study of Ramos et al. did not report a significant difference in isometric strength of knee flexors and knee extensors between 8 weeks of conventional resistance training and elastic tube resistance training.27

Isokinetic strength: Three studies showed a significant increase of 8.0–25.2% in isokinetic peak torque (Nm) after training.24,20,28 One study, however, reported no significant increase in isokinetic peak torque.80 Significant between-group differences in isokinetic peak torque were in favor of training compared to control in two studies.20,28 In one study, however, no significant difference between training and control group was reported in isokinetic peak torque.19

Isotonic strength: Isotonic quadriceps strength measured by 1RM leg press showed an increase of 16.0–27.1% after training.18,21 Between group differences were also significant in favor of training compared to control.18,21 A 5RM leg press was also measured in one study and increased with 34.5% after training, which was significantly different compared to control.20 A 1RM leg extension increased with 44% after resistance training in patients with COPD, which was significantly different compared to control in favor of training.18

Muscle endurance

Isokinetic endurance: Isokinetic total work during 30 consecutive knee extension repetitions was significantly increased with 11.5%, which was significantly different with controls.28 Another study reported a significant increase of 320 J in isokinetic total work during 60 seconds of knee extension repetitions in patients with COPD after training which was also significantly different with controls.19

Isotonic endurance: Isotonic muscle endurance of the lower limbs with external loading increased with 25 repetitions performed in 30 seconds in the training group compared to the control group.80

Muscle mass

One study reported a significant 4.2% increase in cross-sectional area (CSA) of the quadriceps, measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which was not different compared to nonexercising COPD controls.20 Two other studies measured thigh lean mass with dual-energy x-ray absorptiometriy (DEXA) and reported a 5.7–7.3% increase after resistance training.24,25 Menon et al. also measured an increase of 21.8% in m. rectus femoris CSA and 12.1% in quadriceps thickness via ultrasound after training.25

Combined aerobic and resistance training (Table 4)

Muscle strength

Isometric strength—A significant increase of 7.0–32.0% in isometric quadriceps strength after training was reported in seven studies,34,35,37,38,42,44,49 with one study only stating significant improvement without showing data.45 Two studies reported no significant change in isometric quadriceps strength after training.30,40 Three studies reported significant differences between the training and the control group in favor of training,37,29,46 while one other study reported no significant difference between training and control group.39 Nonsignificant differences were also reported between sarcopenic and nonsarcopenic patients,50 between patients with or without contractile muscle fatigue,44 between trained patients with COPD and trained healthy controls,45 and between hypoxemic and normoxemic patients.49

Isokinetic strength: Five studies measured isokinetic quadriceps strength after training showing a 8.3–30% increase in peak torque.31–33,36,41 One study also measured isokinetic hamstring strength of the right and the left leg which increased with 20.2% and 42.1%, respectively.32

Isotonic strength: One study measured isotonic strength as 1RM after training, showing a 33.9% increase in leg extension 1RM after high-intensity training which was significantly different with low-intensity training.43 No significant change was established after low-intensity training.43 Four studies measured isotonic quadriceps strength via 10RM, with three studies showing a 63.4–96.9% increase in 10RM leg extension,48,51,52 while another study reported a 71.0% increase in 10RM weightlifting after training.53 A 15RM leg press was measured in one study, with a mean change of 16 kg reported after training, which was significantly different with controls whom did not show a significant change.37

Muscle endurance

Isokinetic endurance: Quadriceps fatigue as a proportional decline of isokinetic peak torques during 15 sequential voluntary maximal contractions at an angular velocity of 90°/second was measured and improved with 20% after training.33

Isotonic endurance: A study measured an increase of 44.5% in time to exhaustion during dynamic contractions at 30% maximal voluntary contraction (MVC) at a rate of 10 movements per minute after training.45

Muscle mass

Quadriceps CSA, measured via MRI, was reported to increase with 7% after combined aerobic and resistance training.35 Another study compared CSA of m. rectus femoris, measured via ultrasound, between a nonindividualized low-intensity and individualized training group. Muscle mass improved significantly with 8.6% after individualized training but not after nonindividualized low-intensity training. Between group differences were however not significant.47

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and magnetic stimulation training (Table 5)

Muscle strength

Isometric strength: Two studies reported an 11–14.8% increase in isometric quadriceps strength after NMES,58,60 which was significantly different between NMES and sham after 6 weeks in favor of NMES.58,60 Two other studies did not report a significant increase after NMES,55,57 with one study also reporting no significant differences between NMES and control after the training protocol.55 Magnetic stimulation training (MST) increased isometric quadriceps strength with 17.5%.61

Isokinetic strength: Peak torque increased and was significantly different with controls in favor of NMES after the training protocol,55,54 wherein one study with 39.0%54 while the other study did not report significant data.55 Two studies did not report a significant increase after NMES56,57 with also no significant difference between NMES and sham after the training protocol.57 Hamstrings peak torque showed a 33.9% increase after NMES which was significantly different with controls in favor of NMES.54

Involuntary strength: Unpotentiated twitch after NMES was reported to be significantly increased with 14% which was significantly different between NMES and sham after 6 weeks in favor of NMES after adjustment for baseline.60 Unpotentiated twitch after MST showed no significant increase in both the intervention and the control group.61

Muscle endurance

Isometric endurance: A NMES study measured time to exhaustion after an endurance test (isometric contraction at 60% MVC) and reported a 37% increase in time to exhaustion after NMES, which was significantly different with the control group58. After MST, quadriceps muscle endurance was increased with 44%. Muscle endurance was measured as time to exhaustion for isometric leg extensions at 10% MVC with 12 contractions per minute.61

Isokinetic endurance: The fatigue index after a quadriceps muscle endurance isokinetic test (maximal number of contractions in 1 minute) was reported to be decreased which was significantly different between NMES and controls in favor of NMES.55

Muscle mass

A 6% increase in mid-thigh and calf muscle mass was reported, which was significantly different between NMES and sham in favor of NMES, measured by computed tomography (CT).58 In contrast, another study reported no increase in leg muscle mass, measured by DEXA, after NMES.56 A third study measured thigh circumference and reported a significant 2.9% increase, which was significantly higher compared to the control group.59 Another recent study measured rectus femoris CSA via ultrasound after NMES and reported a significant increase of 19.7%, which was significantly different between NMES and sham in favor of NMES.60 (Table 6)

Other training modalities (Table 6)

High-intensity interval training

One study performed high-intensity interval knee-extensor training in patients with COPD (Table 6). Muscle endurance of the quadriceps, measured as peak work during an incremental knee-extensor protocol with 2 W increments every 3 minutes, increased with 37.0% after training.62 Muscle mass, measured with MRI, did not increase significantly after HIIT of the knee extensors.62

Whole-body vibration training

Two studies implemented whole-body vibration training (WBVT) as their training stimulus (Table 6)63,64. In one 6-week WBVT study, isokinetic strength of the quadriceps and hamstrings did not increase significantly after WBVT and was not significantly different between WBVT and control group after the intervention.63 Another 12-week study implemented WBVT or resistance training. Only the resistance training group increased their isometric quadriceps strength significantly with 10.5%. However, no significant differences between WBVT and resistance training were established after the intervention (Table 6).64

Water-based training