Abstract

Aims

To test the acceptability and feasibility of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of mood and injection risk behavior among young people who inject drugs (PWID), using mobile phones.

Methods

Participants were 185 PWID age 18 to 35 recruited from two sites of a large syringe service program in Chicago. After completing a baseline interview, participants used a mobile phone app to respond to momentary surveys on mood, substance use, and injection risk behavior for 15 days. Participants were assigned to receive surveys 4, 5, or 6 times per day.

Results

Participants were 68% male, 61% non-Hispanic white, 24% Hispanic, and 5% non-Hispanic Black. Out of 185 participants, 8% (n=15) failed to complete any EMA assessments. Among 170 EMA responders, the mean number of days reporting was 10 (SD 4.7), the mean proportion of assessments completed was 0.43 (SD 0.27), and 76% (n=130) completed the follow-up interview. In analyses adjusted for age and race/ethnicity, women were more responsive than men to the EMA surveys in days reporting (IRR=1.33, 95% CI 1.13–1.56), and total number of surveys completed (IRR=1.51, 95% CI 1.18–1.93). Homeless participants responded on fewer days (IRR=0.76, 95% CI 0.64–0.90) and completed fewer surveys (IRR=0.70, 95% CI 0.54–0.91), and were less likely to return for follow-up (p=0.016). EMA responsiveness was not significantly affected by the number of assigned daily assessments.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated high acceptability and feasibility of EMA among young PWID, with up to 6 survey prompts per day. However, homelessness significantly hampered successful participation.

Keywords: ecological momentary assessment, injection drug use, emotion dysregulation, risk behavior, HIV, hepatitis C, homeless

1. Introduction

Sharing syringes and other injection equipment among people who inject drugs (PWID) is a significant risk factor for transmission and acquisition of blood-borne diseases including HIV and hepatitis C (HCV) (Boodram et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Hagan et al., 2001; Pouget et al., 2012; Thorpe et al., 2002). The prevalence of syringe sharing decreased in the 1990’s as HIV awareness and access to legal sources of sterile syringes increased (Huo et al., 2005; Huo and Ouellet, 2007), but has remained stable in recent years (Neaigus et al., 2017) with high rates among younger PWID (Bailey et al., 2007; Cedarbaum and Banta-Green, 2016; Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2014; Muñoz et al., 2015; Spiller et al., 2015). Models commonly used to explain individual variation in risky behavior include factors such as knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, and behavioral skills as predictors (Bandura, 1994; Fishbein and Middlestadt, 1989; Fisher et al., 2003) or group-level factors such as social norms (Bailey et al., 2007; Davey-Rothwell et al., 2010; Latkin et al., 2013) or social networks (Boodram et al., 2015; De et al., 2007; Latkin et al., 2010). However, the role of emotion has been largely neglected.

A few studies have examined the relationship between injection risk behavior and negative affect (Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2014; Pilowsky et al., 2011; Stein et al., 2003), and the findings indicate that depression is associated with a greater likelihood of risky injection behavior. Deficits in the ability to regulate emotions may also play a role. Recent studies in Australia (Darke et al., 2004) and the United States (Mackesy-Amiti et al., 2014) have found an association between borderline personality disorder (BPD) and risky injection practices. These findings suggest that emotion dysregulation, a defining feature of BPD (Crowell et al., 2009; Linehan, 1993), may be an important determinant of risky injection behavior. Emotion dysregulation has also been implicated in other types of risky behavior (e.g., sexual risk) (Brown et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2012; Morioka et al., 2018; Steinberg, 2008). Nevertheless, these studies have not examined intrapersonal patterns of behavior and affect, which are imperative to better inform interventions, particularly among young PWID.

Cross-sectional studies are inadequate to address how emotion affects risky behavior (Kalichman and Weinhardt, 2001; Mustanski, 2007). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is an optimal method for studying dynamic processes using real-time data collection, and for minimizing retrospective recall bias (Ebner-Priemer and Trull, 2009a, b; Kuntsche and Labhart, 2013; Shiffman et al., 2008). It is particularly appropriate for the study of behaviors that rely on intuitive or automatic processes, as opposed to deliberate decision-making (Kahneman, 2003; Strack and Deutsch, 2004). Biases in retrospective reporting of past events and experiences have been demonstrated in a number of empirical studies, and may be exacerbated by mental health problems (Ebner-Priemer et al., 2006). In addition, EMA allows the study of within-person variability that is not possible with cross-sectional observational studies. However, it is important to understand the potential limitations and biases in using this approach. While studies of drug users in treatment have found good levels of compliance (Freedman et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2009; Serre et al., 2012), little is known about the limitations of this methodology with active drug users (Kirk et al., 2013), or biases that may be related to psychological traits (Courvoisier et al., 2012).

We conducted an exploratory study of mood and injection risk behavior among young PWID using EMA with mobile phones to collect real-time data on injection risk within the context of everyday activities. The primary aim of the study was to test the acceptability and feasibility of EMA to study mood and behavior among young PWID. This included testing for potential biases related to key measures. In addition, we tested the effects of different numbers of daily assessments on participant response patterns. In this paper we report our findings on participation and completion rates, daily response rates, and disruptions caused by events such as arrest or hospitalization. We also examine associations between baseline measures and non-completion, including measures of depression, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, and receptive syringe sharing.

2. Methods

2.1. Participant recruitment

The research was conducted at two field sites operated by Community Outreach Intervention Projects (COIP) in Chicago, Illinois, U.S. from February 2016 to June 2017. These locations provide harm reduction services including a syringe services program (SSP), HIV and HCV testing, counseling and case management services, and prevention-focused street outreach. People between the ages of 18 and 35 who injected illicit drugs in the past 30 days were eligible for the study. COIP’s SSP clients were invited to participate and were encouraged to refer other PWID to the study. Current injection was verified by trained counselors who inspected for injection stigmata and, when stigmata were absent or questionable, evaluated knowledge of the injection process. Age was verified with a driver’s license or a state identification card. Individuals who met the eligibility criteria were offered $10 to complete a screening questionnaire assessing symptoms of borderline personality disorder (MacLean Screening Instrument for BPD) (Zanarini et al., 2003). All participants who completed the screening were invited to participate in the study, regardless of their scores.

2.2. Procedures

After the interviewer administered the written informed consent procedure, participants completed a baseline audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) and were compensated $25. Participants were then trained on the use of the mobile phone app to access the survey and answer the questions. An Android mobile phone (4.4 KitKat OS, retail value ~$50) was provided, or participants could choose to use their own device. Phones were encrypted, password protected, and the EMA app and study messages were protected with an app lock. A mobile contact number was provided for participants to ask questions or report technical problems. Study personnel responded promptly to assistance requests during usual operating hours and as soon as possible outside of usual hours to troubleshoot and resolve issues. Participants received mobile surveys for 15 days (including partial first day). At the end of the 15-day observation period, participants were notified to return to the field site for a brief follow-up survey, and to collect their compensation. The study coordinator attempted to locate participants who failed to appear for the final interview to document the reason for non-return. Study procedures were approved by the University of Illinois at Chicago Institutional Review Board.

2.2.1. Ecological momentary assessment

We used the ilumivu mEMA platform (ilumivu, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA; www.ilumivu.com), that includes a web site for creating and managing surveys and data, and a mobile phone app to deliver the assessments. The EMA app delivered surveys to the phone for 15 days. We varied the number of daily assessments across participants to examine the impact on participation and completion. We also modified the payment per response to allow all participants to potentially earn up the same amount (up to $9.00/day) regardless of the assigned number of assessments. Because participants were often known to one another, we assigned participants to condition sequentially rather than randomly. The first participants received 6 daily assessments (condition 1, paid at $1.50 per response); later participants received 5 daily assessments (condition 2, paid at $1.80 per response), and then 4 (condition 3, paid at $2.25 per response). Participants earned a bonus of $10 for completing at least 80% of the assessments, and an additional $10 if they completed 90% of the assessments. Participants who used their own mobile phone received $25 to offset data usage. Participants who used a project phone received a minimum payout of $25 for returning the phone.

The mEMA app allows responses to be entered on the cell phone even when there is no active internet connection, although an internet connection is needed to upload data. Participants received a notification when each assessment was available, and reminders after 5 minutes and 10 minutes if the survey was not accessed. After 20 minutes the survey became unavailable until the next scheduled assessment. Assessments occurred at random time-points within a set 12-hour window, which was decided by the participant at the beginning of the study to accommodate individual schedules (nearly all within 08:00 to 23:00).

Participants received daily text message updates on their progress showing the number of assessments completed, and the number needed to reach the bonus level. If a participant missed all assessments on any day, he/she received a reminder to contact study personnel for assistance. If a participant failed to complete any assessments for a second consecutive day, the site study coordinator attempted to contact the participant to offer assistance. If a participant failed to complete any assessments for a third day, her/she was notified to return to the field site.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Baseline assessment

The following measures were included in the baseline ACASI.

2.3.1.1. Borderline personality disorder

The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (Zanarini et al., 2003) consists of ten yes/no items. The score is computed as the total number of items positively endorsed. To adapt the instrument for computer-assisted self-administration, we revised item #3, “Have you had at least two other problems with impulsivity…,” by presenting a checklist with the question “Have you had any of the following problems with impulsive behavior? [eating binges, gambling or spending sprees, drug or drinking binges, reckless sexual activity, reckless driving, verbal outbursts]” and scoring the item as positive if two or more items were endorsed. Internal consistency in the current sample was acceptable (alpha = 0.77).

2.3.1.2 Sociodemographic and geographic characteristics

The questionnaire assessed demographic characteristics including sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, and highest level of education attained. Residential zip code, sources of income, places lived or slept, homelessness, and drug treatment were assessed with reference to the past six months. Current participation in drug treatment was also assessed. Homelessness was measured with two different questions: 1) “In the past 6 months, have you thought of yourself as homeless?” and 2) “In the past 6 months, have you slept in a shelter, car, abandoned building, public park, squatting place, or other non-dwelling for more than 7 nights in a row?” Based on these two questions, we created a single composite variable with three levels: 1) not homeless, 2) thought of as homeless, 3) slept in non-dwelling.

2.3.1.3 Risk behavior and HIV/HCV status

The NIDA Risk Behavior Assessment (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1993), a widely used instrument with established reliability and validity (Needle et al., 1995; Weatherby et al., 1994), was administered to assess substance use and sexual risk behavior, and HIV testing history and outcomes. Items were added to measure HCV testing history and outcomes. Injection behaviors were assessed with reference to the past 6 months. Receptive syringe sharing (“Thinking about all the times you injected in the past 6 months, how often did you inject with needles that had been used before you by somebody else, even if the needle was cleaned first?”) was measured on a 7-point Likert type scale from “never” to “always”. We recoded responses into 3 categories: never, rarely, and sometimes (less than half the time to always).

2.3.1.4. Emotion dysregulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scales (DERS) (Gratz and Roemer, 2004) is a self-report instrument with six sub-scales, including non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal directed behavior, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Scores are coded such that high scores indicate greater emotion dysregulation. The DERS has been validated in samples of cocaine (Fox et al., 2007) and alcohol (Fox et al., 2008) dependent respondents. Total and subscale scores are computed as the sum of item ratings. In the current sample, internal consistency was excellent for the total scale (alpha = 0.95) and good for all subscales (alpha = 0.82 - 0.87).

2.3.1.5. Impulsivity

The SUPPS-P Impulsive Behavior Scale (Cyders et al., 2014) is a short version of the Urgency, Premeditation, Perseverance, Sensation Seeking, Positive Urgency Impulsive Behavior Scale (UPPS-P) (Cyders et al., 2007; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001; Whiteside et al., 2005), consisting of 20 4-point Likert scale items measuring 5 dimensions of impulsivity. Subscale scores were computed as the mean of item ratings. In the current sample, internal consistency was acceptable for negative urgency (alpha = 0.70) and positive urgency (alpha = 0.73). The perseverance and premeditation subscales were combined for a general measure of impulsivity (alpha = 0.80). The sensation seeking subscale had poor reliability (alpha = 0.46) and these items were not used.

2.3.1.6. Trait negative affect

The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 – Brief Form (American Psychiatric Association, 2013a; Anderson et al., 2016) assesses 5 personality trait domains, each measured with 5 items rated on a 4-point scale from “very false or often false” to “very true or often true.” Trait negative affect is measured by items such as “I worry about almost everything,” and “I get irritated easily by all sorts of things.” We computed the average domain score. Internal consistency in the current sample was adequate (alpha = 0.76).

2.3.1.7. Depression

The DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure (American Psychiatric Association, 2013b) was used to assess possible psychiatric problems across 13 domains. The instrument consists of 23 questions about problems experienced in the previous 2 weeks, with participants rating how much they have been bothered by these problems on a 5-point scale, from “not at all (0)” to “nearly every day (4)”. Two items were used to screen for potential depression: 1) “Little interest or pleasure in doing things” and 2) “Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” The maximum rating on these two items was used as an indicator of potential depression, with a score of 2 indicating possible mild depression and a score of 3 or 4 indicating possible moderate to severe depression.

2.3.2. Measures for EMA

The EMA assessments included questions on current mood, context (where and who with), current intoxication or withdrawal, injection since last report, and if applicable, recency of injection, and syringe and equipment sharing at last injection. For this analysis we report summary measures of EMA responding, including 1) whether or not EMA surveys were initiated, 2) number of days on which any EMA assessments were completed, and 3) total number of EMA assessments completed.

2.3.3. Follow-up/De-briefing

When participants returned to the field site, we conducted a brief face-to-face follow-up interview using open-ended interviewer-administered questions to assess the participant’s study experience, focused on elucidating problems that participants encountered during the study, as well as potential barriers to responding to assessment prompts. We assessed overdose events, hospitalizations, arrests, and any other event that may have disrupted data collection.

2.4. Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata 13 (StataCorp). For all regression analyses, we conducted link tests to detect specification errors, and we inspected residuals. We computed robust (Huber-White/sandwich) standard errors in regression analyses.

2.4.1. Participation and completion

We conducted chi-square tests to assess bivariate associations of (1) EMA participation and (2) return for follow-up (among EMA responders) with categorical variables including sex, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, employment, homelessness, injection frequency, receptive syringe sharing, and depression score, and t-tests to assess differences on continuous variables (BPD, DERS, impulsivity, and negative affect scores). For each variable having a statistically significant (p < 0.05) effect in bivariate analyses, we computed the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) in a multivariable logistic regression including sex, age, and race/ethnicity as covariates.

2.4.2. EMA responsiveness

We recoded number of days of EMA responding into a categorical variable by quintiles. We conducted ordinal logistic regression on this measure, and negative binomial regression on total number of assessments completed, with sex, age, race/ethnicity, and study condition included as predictors (step 1). We computed a Brant test of the proportional odds assumption for the ordinal logistic model. To test the effect of study condition (see section 2.2.1) on number of assessments completed, we included an offset term in the model to adjust for assessment frequency. In step 2, we computed adjusted effects for sociodemographic variables (education, employment, homelessness, jail past six months), current drug treatment, injection frequency, receptive syringe sharing, and psychological variables, adjusting for significant (p< 0.05) step 1 variables.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

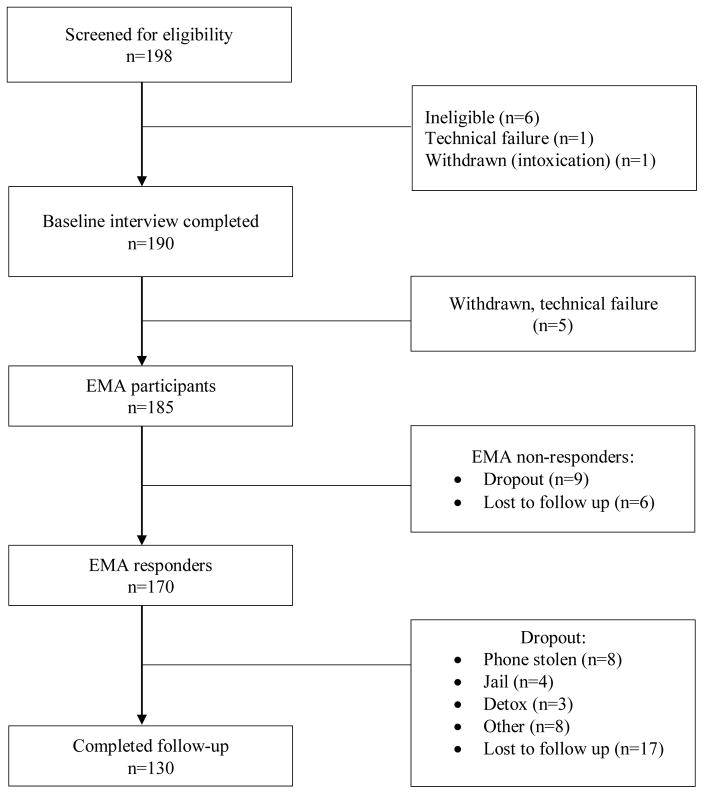

Study participation is summarized in Figure 1. A total of 190 participants, including 128 male and 62 female PWID, were successfully enrolled and completed the baseline assessment. All eligible subjects consented to participate, and none withdrew consent during the baseline visit. Five participants were withdrawn due to technical problems that resulted in loss of data, leaving a sample of 185. Seventy participants were enrolled in condition 1, 74 in condition 2, and 41 in condition 3. Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study Participation Flow

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample (N = 185)

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 126 | 68.1 |

| Female | 59 | 31.9 |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 29.8 (3.9) | |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Heterosexual | 152 | 82.2 |

| Non-Heterosexual | 28 | 15.1 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.7 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 113 | 61.1 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13 | 7.0 |

| Hispanic | 45 | 24.3 |

| Other, non-Hispanica | 12 | 6.5 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.1 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| 8th grade or less | 10 | 5.4 |

| Some high school (9th to 11th grade) | 28 | 15.1 |

| High school graduate (12th grade) or GED | 73 | 39.5 |

| Some college or technical training | 55 | 29.7 |

| College graduate or higher | 15 | 8.1 |

| Missing | 4 | 8.1 |

| Residence (zip code of place slept most past 6 months) | ||

| Chicago | 120 | 64.9 |

| Outside of Chicago | 63 | 34.1 |

| Missing | 2 | 34.1 |

| Homelessness past 6 months | ||

| Not homeless | 68 | 36.8 |

| Thought of as homeless | 37 | 20.0 |

| Slept in non-dwelling > 7 nights | 78 | 42.2 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.1 |

| Places lived or slept past 6 monthsb | ||

| Parent’s house or apartment | 93 | 50.3 |

| Own house, apartment (not parent’s) | 49 | 26.5 |

| Someone else’s house or apartment | 85 | 46.0 |

| Rented room (hotel, motel, or rooming house) | 61 | 33.0 |

| Squatting place, abandoned buildings, car/vehicle, park, street | 82 | 44.3 |

| Shelter, welfare residence | 25 | 13.5 |

| Jail (prison, detention center, juvenile hall) | 31 | 16.8 |

| Halfway house or treatment facility | 37 | 20.0 |

| Other | 18 | 9.7 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.1 |

| Income sourcesb | ||

| Regular job (full or part-time) | 77 | 41.6 |

| Temporary work or odd-jobs | 84 | 45.4 |

| Parents | 103 | 55.7 |

| Friends or family members (not parents) | 86 | 46.5 |

| Husband/wife or domestic partner | 41 | 22.2 |

| Panhandling | 73 | 39.5 |

| Public assistance or disability | 36 | 18.4 |

| Activities that are not legal | 63 | 34.1 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.7 |

| HCV test past 6 months | ||

| No | 77 | 41.6 |

| Yes | 102 | 55.1 |

| Missing | 6 | 3.2 |

| Result of last HCV test | ||

| Negative | 136 | 73.5 |

| Positive | 33 | 17.8 |

| Never Tested | 11 | 5.9 |

| Missing | 5 | 2.7 |

| Frequency of injection past 6 months | ||

| Less than 4 days per week | 25 | 13.5 |

| Four to six days per week | 28 | 15.1 |

| Daily, 2 to 4 times per day | 77 | 41.6 |

| Daily, 5 or more times per day | 51 | 27.6 |

| Missing | 4 | 2.2 |

| Receptive syringe sharing past 6 months | ||

| Never | 99 | 53.5 |

| Rarely | 39 | 21.1 |

| Sometimes | 43 | 23.2 |

| Missing | 4 | 2.2 |

| Currently in drug treatment | ||

| No | 158 | 85.4 |

| Yes | 25 | 13.5 |

| Missing | 2 | 1.1 |

Includes Asian, Pacific Islander, Native American, Black/African-American, mixed race, and unidentified race.

Multiple response variable

3.2. EMA participation and completion

EMA participation and study completion were similar across the three study conditions. Fifteen participants (8%) failed to initiate the EMA surveys. Six of these non-responders returned the phone (being either unable to follow the instructions or unwilling to make the effort), 1 entered drug treatment, 1 reported the phone stolen, 1 gave the phone away, and 6 were lost-to-follow-up.

Among the 170 participants who initiated EMA assessments, 55% responded to surveys on at least 11 of the 15 days, while 24% responded on 5 days or fewer. Forty respondents (24%) did not complete the follow-up interview, including 2 participants who returned the phone but refused the interview. We were able to contact or obtain proxy information for 21 of the non-returning participants: 8 reported the phone stolen, 4 were jailed, 3 entered detox, 4 left the area, 1 was hospitalized, and 1 sold the phone. The remaining 17 were lost to follow-up. Thirteen participants withdrew early (day 3 to 11) but returned to collect payment, citing reasons of entering treatment or detox (n=2), leaving the area (n=4), going to jail (n=1), or giving no reason (n=6). Of the 130 participants who returned for the follow-up, five had been arrested, and 11 had been hospitalized; three hospitalizations were drug-related including one non-fatal overdose. Another 3 participants experienced a possible overdose but were not hospitalized.

3.2.1. Predictors of EMA participation

Predictors of EMA participation are shown in Table 2. Hispanic participants had a nominally lower rate of EMA participation compared to all other groups (84% vs. 94%; Fisher’s exact test, p=0.057). Potential depression was associated with greater likelihood of participation. There were no differences between responders and non-responders on BPD, DERS, negative affect, general impulsivity, or negative urgency. However, responders had higher positive urgency scores. In multivariable models adjusting for sex, age, and race/ethnicity, participants with potential moderate to severe depression were more likely to initiate the EMA surveys (vs. None/Slight, aOR = 4.53, 95% CI 1.16–17.67), and higher positive urgency scores were associated with greater likelihood of initiating EMA surveys (aOR = 3.52, 95% CI 1.35–9.15).

Table 2.

Predictors of EMA participation (N = 185) and study completion among EMA responders (N = 170)

| EMA participants | EMA non-participants | Completers | Non-completers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | N | % | Chi2 | p | N | % | N | % | Chi2 | p |

| Sex | 0.21 | 0.651 | 3.65 | 0.056 | ||||||||

| Male | 115 | 91.3 | 11 | 8.7 | 83 | 72.2 | 32 | 27.8 | ||||

| Female | 55 | 93.2 | 4 | 6.8 | 47 | 85.5 | 8 | 14.6 | ||||

| Sexual Orientation | 0.40 | 0.528 | 1.05 | 0.304 | ||||||||

| Non-Heterosexual | 25 | 89.3 | 3 | 10.7 | 21 | 84.0 | 4 | 16.0 | ||||

| Heterosexual | 141 | 92.8 | 11 | 7.2 | 105 | 74.5 | 36 | 25.5 | ||||

| Race | 4.49 | 0.213 | 1.90 | 0.593 | ||||||||

| NH White | 107 | 94.7 | 6 | 9.3 | 80 | 74.8 | 27 | 25.2 | ||||

| NH Black | 12 | 92.1 | 1 | 7.7 | 10 | 83.3 | 2 | 16.7 | ||||

| Hispanic | 38 | 84.4 | 7 | 15.6 | 28 | 73.7 | 10 | 26.3 | ||||

| Other (NH) | 11 | 91.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 10 | 90.9 | 1 | 9.1 | ||||

| Education Level | 0.37 | 0.830 | 1.13 | 0.569 | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 34 | 89.5 | 4 | 10.5 | 27 | 79.4 | 7 | 20.6 | ||||

| High school graduate | 67 | 91.8 | 6 | 8.2 | 48 | 71.6 | 19 | 28.4 | ||||

| Post-secondary | 65 | 92.9 | 5 | 7.1 | 51 | 78.5 | 14 | 21.5 | ||||

| Employment (full-or part-time) | 0.32 | 0.570 | 1.11 | 0.292 | ||||||||

| No | 96 | 93.2 | 7 | 6.8 | 70 | 72.9 | 26 | 27.1 | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 90.9 | 7 | 9.1 | 56 | 80.0 | 14 | 20.0 | ||||

| Jail past 6 months | 3.33 | 0.068 | 1.50 | 0.221 | ||||||||

| No | 137 | 90.1 | 15 | 9.9 | 107 | 78.1 | 30 | 21.9 | ||||

| Yes | 31 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 67.7 | 10 | 32.3 | ||||

| Homelessness | 2.45 | 0.293 | 8.32 | 0.016 | ||||||||

| Not homeless | 65 | 95.6 | 3 | 4.4 | 57 | 87.7 | 8 | 12.3 | ||||

| Thought of as homeless | 34 | 91.9 | 3 | 8.1 | 25 | 73.5 | 9 | 26.5 | ||||

| Slept in non-dwelling > 7 nights | 69 | 88.5 | 9 | 11.5 | 46 | 66.7 | 23 | 33.3 | ||||

| In drug treatment, past 6 months | 1.13 | 0.288 | 0.01 | 0.916 | ||||||||

| No | 102 | 93.6 | 7 | 6.4 | 78 | 76.5 | 24 | 23.5 | ||||

| Yes | 66 | 89.2 | 8 | 10.8 | 50 | 75.8 | 16 | 24.2 | ||||

| Currently in drug treatment | 0.68 | 0.410 | 0.79 | 0.375 | ||||||||

| No | 144 | 91.1 | 14 | 8.9 | 108 | 75.0 | 36 | 25.0 | ||||

| Yes | 24 | 96.0 | 1 | 4.0 | 20 | 83.3 | 4 | 16.7 | ||||

| Injection frequency | 2.49 | 0.477 | 1.59 | 0.663 | ||||||||

| Less than 4 days/week | 22 | 88.0 | 3 | 12.0 | 18 | 81.8 | 4 | 18.2 | ||||

| Four to six days/week | 24 | 85.7 | 4 | 14.3 | 16 | 66.7 | 8 | 33.3 | ||||

| Daily, 2 to 4 times/day | 72 | 93.5 | 5 | 6.5 | 55 | 76.4 | 17 | 23.6 | ||||

| Daily, 5 or more times/day | 48 | 94.1 | 3 | 5.9 | 37 | 77.1 | 11 | 22.9 | ||||

| Inject with used syringe | 1.35 | 0.510 | 5.05 | 0.080 | ||||||||

| Never | 92 | 92.9 | 7 | 7.1 | 76 | 82.6 | 16 | 17.4 | ||||

| Rarely | 37 | 94.9 | 2 | 5.1 | 26 | 70.3 | 11 | 29.7 | ||||

| Sometimes | 38 | 88.4 | 5 | 11.6 | 25 | 65.8 | 13 | 34.2 | ||||

| Depression screening | 6.86 | 0.032 | 6.17 | 0.046 | ||||||||

| None to slight | 18 | 78.3 | 5 | 21.7 | 10 | 55.6 | 8 | 44.4 | ||||

| Mild | 43 | 91.5 | 4 | 8.5 | 31 | 72.1 | 12 | 27.9 | ||||

| Severe | 107 | 94.7 | 6 | 5.3 | 87 | 81.3 | 20 | 18.7 | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | p | |

| Age | 29.7 | 3.9 | 30.9 | 3.5 | 1.16 | 0.248 | 29.7 | 3.9 | 29.8 | 3.8 | 0.18 | 0.859 |

| BPDa Screener Score | 7.2 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 2.2 | −0.84 | 0.402 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 2.8 | −0.64 | 0.520 |

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation | 98.2 | 25.3 | 88.0 | 15.3 | −1.53 | 0.127 | 99.2 | 24.6 | 94.9 | 27.4 | −0.95 | 0.346 |

| Impulsivity: Lack of Premeditation | 3.1 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 0.01 | 0.994 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.07 | 0.944 |

| Impulsivity: Positive Urgency | 2.4 | 0.7 | 2.0 | 0.6 | −2.52 | 0.013 | 2.4 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 0.6 | −0.43 | 0.664 |

| Impulsivity: Negative Urgency | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.5 | −0.67 | 0.504 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 0.72 | 0.475 |

| Trait Negative Affect | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0.947 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 0.7 | −1.49 | 0.139 |

Borderline personality disorder

3.2.2. Predictors of study completion

Predictors of study completion are shown in Table 2. Homelessness in the past six months was significantly associated with non-completion, while potential depression was associated with greater likelihood of completion. There were no differences between participants who returned for follow-up and those who did not on BPD, DERS, negative affect, or measures of impulsivity. In multivariable models adjusting for sex, age and race/ethnicity, participants who slept in a non-dwelling for more than 7 nights were significantly less likely to return for follow-up (vs. not homeless, aOR = 0.29, 95% CI 0.12–0.72), while those who had potential moderate to severe depression were significantly more likely to return for follow-up (vs. None/Slight, aOR = 3.79, 95% CI 1.23–11.69).

3.3. EMA responsiveness

Table 3 reports on EMA responsiveness. In step 1 regressions, there were no significant differences in the number of response days or the proportion of surveys completed across study conditions. Women were more responsive than men for both measures, and participants of non-Hispanic “other” race/ethnicity were more responsive compared to other groups (grand weighted mean contrast, chi2[days]=10.91, p=0.001; chi2[assessments]=8.54, p=0.004). In step 2, participants who slept in a non-dwelling for more than 7 nights were less responsive than those who were not homeless by both measures. Participants who shared syringes more than “rarely” also had fewer days responding and fewer surveys in total. Current drug treatment was associated with greater responsiveness on both measures. No other effects were statistically significant. As there was a significant association between homelessness and receptive syringe sharing (Chi2=13.90, p = 0.008), we also tested their independent contributions by entering both variables together, controlling for sex and race/ethnicity (Table 4). The effects of both variables were diminished, with only the effect of homelessness on total number of assessments remaining statistically significant independent of syringe sharing.

Table 3.

Days of EMA responding and total number of surveys completed, ordinal logistic and negative binomial regression models with robust standard errors (N = 168)a

| Days of EMA responding (quintiles) | Total number of surveys completedb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | aIRR | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | |||

| Step 1 variables:c | ||||||||

| Female vs. male | 4.06 | 2.05 | 8.05 | <0.001 | 1.51 | 1.25 | 1.82 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.02 | 0.94 | 1.10 | 0.677 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 1.04 | 0.373 |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref = NH white) | ||||||||

| NH Black | 3.09 | 0.61 | 15.63 | 0.172 | 1.04 | 0.72 | 1.51 | 0.823 |

| Hispanic | 0.62 | 0.31 | 1.23 | 0.169 | 0.86 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.252 |

| Other (NH) | 3.07 | 1.49 | 6.33 | 0.002 | 1.36 | 1.07 | 1.73 | 0.013 |

| Wald test | chi2(3) = 15.89, p=0.001 | chi2(3) = 9.84, p=0.02 | ||||||

| Condition (Ref = Condition 1)d | ||||||||

| Condition 2 | 0.71 | 0.37 | 1.34 | 0.285 | 1.04 | 0.84 | 1.30 | 0.705 |

| Condition 3 | 0.71 | 0.35 | 1.43 | 0.333 | 1.12 | 0.86 | 1.45 | 0.395 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 1.62, p=0.44 | chi2(2) = 0.74, p=0.69 | ||||||

| Step 2 variables: e | ||||||||

| Education (Ref = less than high school) | ||||||||

| High school | 0.71 | 0.33 | 1.51 | 0.369 | 0.99 | 0.75 | 1.31 | 0.969 |

| Post-secondary | 1.05 | 0.49 | 2.23 | 0.905 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 1.36 | 0.758 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 1.58, p=0.45 | chi2(2) = 0.20, p=0.91 | ||||||

| Employed vs. not employed | 0.90 | 0.49 | 1.66 | 0.738 | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.25 | 0.941 |

| Jail past 6 months | 0.53 | 0.27 | 1.04 | 0.065 | 0.89 | 0.67 | 1.18 | 0.400 |

| Homeless (Ref = Not homeless) | ||||||||

| Thought of as homeless | 0.60 | 0.28 | 1.29 | 0.192 | 0.80 | 0.63 | 1.02 | 0.074 |

| Slept in non-dwelling > 7 nights | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.74 | 0.003 | 0.66 | 0.53 | 0.83 | < 0.001 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 8.82, p=0.012 | chi2(2) = 13.74, p=0.001 | ||||||

| Currently in drug treatment | 2.64 | 1.05 | 6.62 | 0.039 | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.72 | 0.032 |

| Frequency of injection (Ref = less than 4 days per week) | ||||||||

| 4 to 6 days per week | 1.10 | 0.36 | 3.38 | 0.874 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 1.42 | 0.750 |

| daily, 2–4 times per day | 1.24 | 0.43 | 3.55 | 0.692 | 1.03 | 0.74 | 1.44 | 0.855 |

| daily, 5 or more times per.. | 1.30 | 0.45 | 3.73 | 0.626 | 0.97 | 0.69 | 1.38 | 0.881 |

| Wald test | chi2(3) = 0.37, p=0.95 | chi2(3) = 0.47, p=0.93 | ||||||

| Injected with used syringe past 6 months (Ref = Never) | ||||||||

| Rarely | 0.60 | 0.29 | 1.24 | 0.169 | 0.84 | 0.65 | 1.08 | 0.173 |

| Sometimes | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.003 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.002 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 8.63, p=0.013 | chi2(2) = 9.85, p=0.007 | ||||||

| BPDf Screener core | 1.03 | 0.91 | 1.16 | 0.646 | 1.01 | 0.97 | 1.05 | 0.704 |

| Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 0.085 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.155 |

| Impulsivity: (Lack of) Premeditation and Perseverence | 0.72 | 0.42 | 1.25 | 0.239 | 0.96 | 0.80 | 1.15 | 0.625 |

| Impulsivity: Positive Urgency | 0.86 | 0.58 | 1.25 | 0.421 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.16 | 0.925 |

| Impulsivity: Negative Urgency | 0.71 | 0.42 | 1.21 | 0.213 | 0.95 | 0.80 | 1.12 | 0.543 |

| Trait negative affect | 1.51 | 0.98 | 2.33 | 0.065 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.26 | 0.254 |

| Depression (Ref = no symptoms) | ||||||||

| Mild depression | 1.06 | 0.41 | 2.76 | 0.902 | 0.97 | 0.64 | 1.47 | 0.885 |

| Moderate to severe depression | 1.83 | 0.78 | 4.27 | 0.165 | 1.12 | 0.77 | 1.64 | 0.547 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 3.63, p=0.16 | chi2(2) = 1.62, p=0.44 | ||||||

2 observations missing on covariates

Model includes offset to adjust for number of surveys available based on condition enrollment

Entered all at once

Conditions: 1 = 6 assessments per day at $1.50 ea., 2 = 5 per day at $1.80 ea., 3 = 4 per day at $2.25 ea.

Entered separately, adjusted for selected step 1 variables

Borderline personality disorder

Table 4.

Days of EMA responding and total number of surveys completed, multivariable ordinal logistic and negative binomial regression models with robust standard errors (N = 166)a

| Days of EMA responding (quintiles) | Total number of surveys completed | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | aIRR | 95% Conf. Int. | p-value | |||

| Female vs. male | 4.07 | 2.01 | 8.25 | <0.001 | 1.47 | 1.20 | 1.80 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity (Ref = NH white) | ||||||||

| NH Black | 3.68 | 0.76 | 17.73 | 0.104 | 1.13 | 0.77 | 1.65 | 0.538 |

| Hispanic | 0.59 | 0.30 | 1.14 | 0.116 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 1.03 | 0.091 |

| Other (NH) | 2.43 | 1.09 | 5.42 | 0.030 | 1.24 | 0.95 | 1.61 | 0.114 |

| Wald test | chi2(3) = 11.96, p=0.008 | chi2(3) = 7.46, p=0.059 | ||||||

| Homeless (Ref = Not homeless) | ||||||||

| Thought of as homeless | 0.77 | 0.36 | 1.64 | 0.497 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 1.09 | 0.208 |

| Slept in non-dwelling > 7 nights | 0.48 | 0.25 | 0.90 | 0.022 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.89 | 0.003 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 5.25, p=0.072 | chi2(2) = 8.79, p=0.012 | ||||||

| Injected with used syringe past 6 months (Ref = Never) | ||||||||

| Rarely | 0.64 | 0.31 | 1.31 | 0.220 | 0.88 | 0.68 | 1.14 | 0.349 |

| Sometimes | 0.40 | 0.19 | 0.87 | 0.021 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 0.028 |

| Wald test | chi2(2) = 5.44, p=0.066 | chi2(2) = 5.06, p=0.080 | ||||||

4 observations missing on covariates

3.4. Debriefing reports

In the debriefing interview, two-thirds of participants reported a problem with the phone or the mobile app. The most common problem concerned not receiving notifications (25%), followed by problems with uploading surveys or number of surveys received by data manager not matching the number they thought they had completed (19%), and the app stalling or crashing (17%). Other problems included poor connectivity (4%) and difficulty keeping the battery charged (5%). Commonly cited reasons for missing surveys were being unavailable (e.g., sleeping, showering) (23%), phone turned off or battery discharged (18%), being outside or in a noisy environment (18%), and working (16%); few (8%) cited drug use as a reason.

4. Discussion

Recent studies have used EMA to collect data on substance use and craving in a community sample (Kirk et al., 2013; Linas et al., 2015). However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to test the use of EMA to study injection risk behavior among young PWID, a population that is experiencing alarming increases in HCV infection incidence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008, 2017; Page et al., 2009; Zibbell et al., 2015). This is a high-risk population with multiple factors potentially interfering with study participation, including high rates of residential transience (Boodram et al., 2017). The EMA study had high acceptability, as all of the eligible subjects agreed to participate, none withdrew their consent during the baseline visit, and 92% initiated EMA assessments. The most common reasons for study dropout were stolen phones, arrest, and entering drug treatment. Nevertheless, 70% of all enrolled participants (76% of those who initiated EMA) returned to complete the follow-up interview. Of those who dropped out after initiating EMA, we were able to locate more than half, leaving only 12% of all participants unaccounted for.

The number of daily assessment prompts did not affect any measure of participation or responsiveness. Women were more responsive than men in terms of both the number of days reporting and total number of surveys completed. Although there were few participants of non-Hispanic “other” race/ethnicity, they were more responsive compared to other groups. Positive associations between symptoms of depression and measures of participation may reflect greater interest in mood tracking among PWID experiencing these symptoms. It is not clear why positive urgency (a tendency to engage in impulsive risky behavior in response to intense positive emotion) was associated with EMA participation; however, it was not associated with study completion or responding rate.

Homelessness was associated with non-completion and with fewer days of reporting and surveys completed. It was often a challenge for these participants to keep the phone charged, and they were often victims of theft. Most concerning, participants who shared syringes more than rarely also had a lower response rate. These effects partially overlap, as PWID who were homeless were also more likely to share syringes. On the other hand, being enrolled in drug treatment at baseline was associated with higher rates of responding. In future studies, it would be important to take account of these sources of bias. Steps to ameliorate the impact of homelessness may help to reduce response bias related to syringe sharing. On a more positive note, there was no evidence of bias associated with borderline personality disorder symptoms or with emotion dysregulation.

4.1. Limitations

Rather than randomizing each participant into one of the three study conditions with different numbers of survey prompts, we recruited participants into the conditions sequentially. It is possible, if unlikely, that there is a systematic difference between earlier and later participants that was confounded with study condition and masked its effects. Fewer participants were enrolled into the third condition; however, the sample size was sufficient to detect a medium to large effect (d ≥ 0.60) with at least 80% power. We also chose to vary the payment values per response to keep the daily maximum earnings constant across conditions in order to test the effect of requiring more or less effort for the same reward. The results might be different if per response payments are held equal instead.

Many participants reported problems with the phone or the mobile app in the debriefing interview, but most did not request technical assistance. These problems were usually temporary and were resolved by technical support if reported. Some of these difficulties arose due to app upgrades initiated by the vendor that were incompatible with our (low-budget) devices. This is an unfortunate consequence of using a commercial product rather than a custom-built application. We also found it necessary to lock the Google Play store to prevent interference from other apps.

5. Conclusion

This study demonstrated high acceptability and feasibility of EMA among young people who inject drugs, with up to 6 survey prompts per day. Individuals experiencing symptoms of depression may be more motivated to engage in a study that involves mood tracking. Otherwise, psychological characteristics including borderline personality symptoms and emotion dysregulation were not associated with compliance or responding rates. Difficulties associated with homelessness that impact responsiveness present a challenge, especially as these individuals are more likely to engage in risky injection behaviors.

Highlights.

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) of mood and injection behavior is feasible

Women and participants in drug treatment had higher response rates

Homelessness was a significant barrier to successful study participation

EMA is a promising approach for the study of mood and injection risk behavior

Limitations and potential biases associated with EMA must be considered

Acknowledgments

We thank study participants for the time and effort they contributed to this study, and acknowledge the dedication of our staff members who conducted the interviews and otherwise operated field sites in a manner welcoming to potential participants.

Footnotes

Contributors

MM was responsible for the development of the research protocol, statistical analysis, interpretation of results, and manuscript writing. BB contributed to interpretation of results, manuscript writing, and critical revision. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Role of Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health [grant number R21DA039010]. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Author; Washington, DC: 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Self-Rated Level 1 Cross-Cutting Symptom Measure—Adult. 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Sellbom M, Salekin RT. Utility of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5–Brief Form (PID-5-BF) in the measurement of maladaptive personality and psychopathology. Assessment. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1073191116676889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Ouellet LJ, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Golub ET, Hagan H, Hudson SM, Latka MH, Gao W, Garfein RS. Perceived risk, peer influences, and injection partner type predict receptive syringe sharing among young adult injection drug users in five U.S. cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:S18–S29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Intervention. Plenum Press; New York: 1994. pp. 25–59. [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Golub ET, Ouellet LJ. Socio-behavioral and geographic correlates of prevalent hepatitis C virus infection among young injection drug users in metropolitan Baltimore and Chicago. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Hotton AL, Shekhtman L, Gutfraind A, Dahari H. High-risk geographic mobility patterns among young urban and suburban persons who inject drugs and their injection network members. J Urban Health. 2017;95:71–82. doi: 10.1007/s11524-017-0185-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Latkin C. The role of social networks and geography on risky injection behaviors of young persons who inject drugs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Houck C, Lescano C, Donenberg G, Tolou-Shams M, Mello J. Affect regulation and HIV risk among youth in therapeutic schools. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2272–2278. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0220-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cedarbaum ER, Banta-Green CJ. Health behaviors of young adult heroin injectors in the Seattle area. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;158:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of enhanced surveillance for hepatitis C virus infection to detect a cluster among young injection-drug users--New York, November 2004-April 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among injecting drug users - 20 cities, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Surveillance for Viral Hepatitis -- United States, 2015. Division of Viral Hepatitis, CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Courvoisier DS, Eid M, Lischetzke T. Compliance to a cell phone-based ecological momentary assessment study: The effect of time and personality characteristics. Psychol Assess. 2012;24:713–720. doi: 10.1037/a0026733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychol Bull. 2009;135:495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Littlefield AK, Coffey S, Karyadi KA. Examination of a short version of the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1372–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: Development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Williamson A, Ross J, Teesson M, Lynskey M. Borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder and risk-taking among heroin users: Findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey-Rothwell MA, Latkin CA, Tobin KE. Longitudinal analysis of the relationship between perceived norms and sharing injection paraphernalia. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:878–884. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9520-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De P, Cox J, Boivin JF, Platt RW, Jolly AM. The importance of social networks in their association to drug equipment sharing among injection drug users: A review. Addiction. 2007;102:1730–1739. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Welch SS, Thielgen T, Witte S, Bohus M, Linehan MM. A valence-dependent group-specific recall bias of retrospective self-reports - A study of borderline personality disorder in everyday life. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:774–779. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000239900.46595.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Trull TJ. Ambulatory assessment: An innovative and promising approach for clinical psychology. Eur Psychol. 2009a;14:109–119. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040.14.2.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Trull TJ. Ecological momentary assessment of mood disorders and mood dysregulation. Psychol Assess. 2009b;21:463–475. doi: 10.1037/a0017075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Middlestadt S. Using the theory of reasoned action as a framework for understanding and changing AIDS-related behaviors. In: Mays V, Albee G, Schneider S, editors. Primary Prevention of AIDS: Psychological Approaches. Sage; Newbury Park: 1989. pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WA, Fisher JD, Harman J. The information-motivation-behavioraI skills model: A general social psychological approach to understanding and promoting health behavior. In: Suls J, Wallston KA, editors. Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness. Blackwell Publishing; Malden, MA: 2003. pp. 82–106. [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Axelrod SR, Paliwal P, Sleeper J, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control during cocaine abstinence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:298–301. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Hong KA, Sinha R. Difficulties in emotion regulation and impulse control in recently abstinent alcoholics compared with social drinkers. Addict Behav. 2008;33:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, Schumacher JE. Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26:41–54. doi: 10.1023/b:joba.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan H, Thiede H, Weiss NS, Hopkins SG, Duchin JS, Alexander ER. Sharing of drug preparation equipment as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:42–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.91.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo D, Bailey SL, Garfein RS, Ouellet LJ. Changes in the sharing of drug injection equipment among street-recruited injection drug users in Chicago, Illinois, 1994–1996. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40:63–76. doi: 10.108i/JA20030495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo D, Ouellet LJ. Needle exchange and injection-related risk behaviors in Chicago - A longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45:108–114. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EI, Barrault M, Nadeau L, Swendsen J. Feasibility and validity of computerized ambulatory monitoring in drug-dependent women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:322–326. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Weinhardt L. Negative affect and sexual risk behavior: Comment on Crepaz and Marks (2001) Health Psychol. 2001;20:300–301. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.20.4.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Maps of bounded rationality: Psychology for behavioral economics. Am Econ Rev. 2003;93:1449–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk GD, Linas BS, Westergaard RP, Piggott D, Bollinger RC, Chang LW, Genz A. The Exposure Assessment in Current Time Study: Implementation, feasibility, and acceptability of real-time data collection in a community cohort of illicit drug users. AIDS Res Treat. 2013;2013:10. doi: 10.1155/2013/594671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Labhart F. Using personal cell phones for ecological momentary assessment: An overview of current developments. Eur Psychol. 2013;18:3–11. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Donnell D, Liu TY, Davey-Rothwell M, Celentano D, Metzger D. The dynamic relationship between social norms and behaviors: The results of an HIV prevention network intervention for injection drug users. Addiction. 2013;108:934–943. doi: 10.1111/add.12095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C, Kuramoto S, Davey-Rothwell M, Tobin K. Social norms, social networks, and HIV risk behavior among injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:1159–1168. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9576-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linas BS, Latkin C, Westergaard RP, Chang LW, Bollinger RC, Genz A, Kirk GD. Capturing illicit drug use where and when it happens: An ecological momentary assessment of the social, physical and activity environment of using versus craving illicit drugs. Addiction. 2015;110:315–325. doi: 10.1111/add.12768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Guilford; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mackesy-Amiti ME, Donenberg GR, Ouellet LJ. Psychiatric correlates of injection risk behavior among young people who inject drugs. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:1089–1095. doi: 10.1037/a0036390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Vachon DD, Aalsma MC. Negative affect and emotion dysregulation: Conditional relations with violence and risky sexual behavior in a sample of justice-involved adolescents. Crim Just Behav. 2012;39:1316–1327. doi: 10.1177/0093854812448784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morioka CK, Howard DE, Caldeira KM, Wang MQ, Arria AM. Affective dysregulation predicts incident nonmedical prescription analgesic use among college students. Addict Behav. 2018;76:328–334. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz F, Burgos J, Cuevas-Mota J, Teshale E, Garfein R. Individual and socio-environmental factors associated with unsafe injection practices among young adult injection drug users in San Diego. AIDS Behav. 2015;19:199–210. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0815-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B. The influence of state and trait affect on HIV risk behaviors: A daily diary study of MSM. Health Psychol. 2007;26:618–626. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.5.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Risk Behavior Assessment. NIDA Community Research Branch; Rockville, MD: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Neaigus A, Reilly KH, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpi-Acosta C, Marshall DMI. Trends in HIV and HCV risk behaviors and prevalent infection among people who inject drugs in New York City, 2005–2012. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(Suppl):S325–S332. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Needle R, Fisher DG, Weatherby N, Chitwood D, Brown B, Cesari H, Booth R, Williams ML, Watters J, Andersen M, Braunstein M. Reliability of self-reported HIV risk behaviors of drug users. Psychol Addict Behav. 1995;9:242–250. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.9.4.242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page K, Hahn JA, Evans J, Shiboski S, Lum P, Delwart E, Tobler L, Andrews W, Avanesyan L, Cooper S, Busch MP. Acute hepatitis C virus infection in young adult injection drug users: A prospective study of incident infection, resolution, and reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1216–1226. doi: 10.1086/605947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT, Burchett B, Blazer DG, Ling W. Depressive symptoms, substance use, and HIV-related high-risk behaviors among opioid-dependent individuals: Results from the Clinical Trials Network. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:1716–1725. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.611960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouget ER, Hagan H, Des Jarlais DC. Meta-analysis of hepatitis C seroconversion in relation to shared syringes and drug preparation equipment. Addiction. 2012;107:1057–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03765.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serre F, Fatseas M, Debrabant R, Alexandre JM, Auriacombe M, Swendsen J. Ecological momentary assessment in alcohol, tobacco, cannabis and opiate dependence: A comparison of feasibility and validity. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiller MW, Broz D, Wejnert C, Nerlander L, Paz-Bailey G. HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among persons who inject drugs - 20 cities, United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:270–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MD, Solomon DA, Herman DS, Anderson BJ, Miller I. Depression severity and drug injection HIV risk behaviors. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1659–1662. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Dev Rev. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8:220–247. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0803_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe LE, Ouellet LJ, Hershow R, Bailey SL, Williams IT, Williamson J, Monterroso ER, Garfein RS. Risk of hepatitis C virus infection among young adult injection drug users who share injection equipment. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155:645–653. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherby NL, Needle R, Cesari H, Booth R, McCoy CB, Watters JK, Williams M, Chitwood DD. Validity of self-reported drug use among injection drug users and crack cocaine users recruited through street outreach. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17:347–355. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(94)90035-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Pers Indiv Differ. 2001;30:669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR, Miller JD, Reynolds SK. Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: A four-factor model of impulsivity. Eur J Pers. 2005;19:559–574. doi: 10.1002/per.556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, Boulanger JL, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J. A screening measure for BPD: The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) J Personal Disord. 2003;17:568–573. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.6.568.25355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, Suryaprasad A, Sanders KJ, Moore-Moravian L, Serrecchia J, Blankenship S, Ward JW, Holtzman D. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged </=30 years - Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]