Abstract

Treatment of acute secretory diarrheal illnesses remains a global challenge. Enterotoxins produce secretion through direct epithelial action and indirectly by activating enteric nervous system (ENS). Using a microperfused colonic crypt technique, we have previously shown that R568, a calcimimetic that activates the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR), can act on intestinal epithelium and reverse cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion. In the present study, using the Ussing chamber technique in conjunction with a tissue-specific knockout approach, we show that the effects of cholera toxin and CaSR agonists on electrolyte secretion by the intestine can also be attributed to opposing actions of the toxin and CaSR on the activity of the ENS. Our results suggest that targeting intestinal CaSR might represent a previously undescribed new approach for treating secretory diarrheal diseases and other conditions with ENS over-activation.

Introduction

Acute secretory diarrheal illnesses, such as cholera, affect millions of children and adults each year and morbidity and mortality from the large fluid and electrolyte losses remain high1,2. The extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR)3 is an ancient G protein-coupled cell surface receptor that is expressed in diverse tissues in mammalian4 and marine5 species and is a key regulator of tissue responses required for calcium homeostasis3, salt and water balance6,7, and osmotic regulation5. The primary physiological ligand for the CaSR is extracellular ionized calcium (Ca2+o), providing a mechanism for Ca2+o to function as a first messenger. The CaSR also functions as a more general sensor of the extracellular milieu due to allosteric modification of Ca2+o affinity by polyamines, L-amino acids, pH and ionic strength8.

Enteric mucosal cells along the entire small and large intestines express the CaSR. These include enterocytes9–12, neurons in the enteric nervous system (ENS)9,13 and enterochromaffin (EC) cells14 and other enteroendocrine (EE) cells (refer to a recent review by Tang et al.15 for refs). Studies that characterize the physiologic function of the CaSR in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract have just begun15,16. CaSR has been identified on both the apical and basolateral membranes of human11,17 and rat colonocytes9,11. Receptors localized to both membrane domains of this polarized epithelium are functionally active and can be activated by Ca2+o, calcimimetics such as R568, and other polycations such as spermine with similar potency and EC50 values10,11. In isolated microperfused colonic crypts, CaSR activation from either the mucosal or serosal side inhibited net fluid secretion10,11,18 and cyclic nucleotide accumulation18 induced by synthetic/natural secretagogues such as forskolin and guanylin, which generate cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP, respectively. CaSR activation also blocks the effects of bacterial enterotoxins18 such as cholera toxin (CTX), a potent activator of membrane-bound adenylyl cyclase leading to elevated intracellular levels of the cyclic AMP. It also blocks the effects of heat stable Escherichia coli enterotoxin (STa)18, which enhances cytosolic cyclic GMP accumulation through the guanylyl cyclase C-type guanylin receptor. CaSR has also been localized to the neurons in the ENS9,13, the brain of the gut19, and thus could regulate neural secretory responses. However, studies that characterize the role of CaSR in the enteric neurons have been limited.

In rodents and humans, the ENS, mainly the submucosal plexus, releases neurotransmitters [e.g., vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) and acetylcholine (ACh)] that regulate fluid secretion (see reviews20–22). There is compelling evidence from in vivo experiments that the ENS modulates intestinal fluid secretion induced by bacterial enterotoxins (e.g., CTX, STa)21–23, as well as by viral enterotoxins [e.g., rotavirus nonstructural protein 4 (NSP4)]24,25. For example, cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion is blocked by tetrodotoxin (TTX) or lidocaine, inhibitors of neural activity26, or hexamethonium, an inhibitor of cholinergic nicotinic receptor antagonist27. Based upon this, a dual pathway model for fluid secretion and diarrhea formation has been proposed: (1) a non-neuronal fluid secretory response due to binding of enterotoxins directly to enterocytes, leading to generation of cyclic nucleotides, which is TTX/lidocaine-insensitive; (2) a neuronal secretory response that is mediated by stimulation of the neurons in the ENS, which is TTX/lidocaine-sensitive. The calcimimetic R568 is a specific CaSR agonist. Using isolated rat colon segments containing intact ENS mounted in Ussing chambers, we have previously shown that R568, when applied serosally, inhibited basal and forskolin-induced secretory currents in the absence, but not presence, of TTX13. This suggests that this anti-secretory agent acts on the intestine through neurons within the ENS. Although the finding from this latter study on calcimimetic is consistent with the dual-pathway regulation model, it is also possible that R568’s anti-secretory effect results from its binding to the receptor in the basolateral membrane of mucosal epithelial cells. Furthermore, R568 might inhibit TTX/lidocaine-dependent secretory current indirectly, by acting on the CaSR on mucosal epithelial cells that then interact with TTX/lidocaine-sensitive enteric neurons. Finally, there is a small likelihood that R568’s anti-secretory effect is due to a non-specific off-target effect of this agent28.

To test the hypothesis that R568 acts on neuronal CaSR of the ENS to inhibit electrolyte secretion by the intestine, the present study employed a tissue-specific knockout mouse approach in conjunction with Ussing chamber methods for further studying the effect of this calcimimetic on basal and secretagogue-evoked intestinal secretion. In addition to forskolin, we also employed cholera toxin. We selected cholera toxin because it is a secretagogue known to activate enteric neuronal reflexes21. The two tissue-specific CaSR mutant mouse lines used were: (1) Mucosal epithelial cell CaSR-specific conditional knockout mice (villinCre/Casrflox/flox mice)29, and (2) Neuronal cell CaSR-specific conditional knockout mice (nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice)30. Our results show that CaSR activity on enteric neurons is required for R568-mediated inhibition of cholera toxin-induced electrolyte secretion by the intestine. This is the first demonstration that the CaSR expressed by enteric neurons is functional. Thus, apart from their direct mucosal epithelial effects shown in our previous studies using ENS-absent colonic epithelial crypts10,11,18, our present data show that the pro- and anti-secretory effects of cholera toxin and R568 on electrolyte secretion by the intestine could also be mediated, indirectly, through opposing actions of the two agents on the activity of the ENS.

Results

Calcimimetic inhibits basal Isc in mouse colon via CaSR on enteric neurons

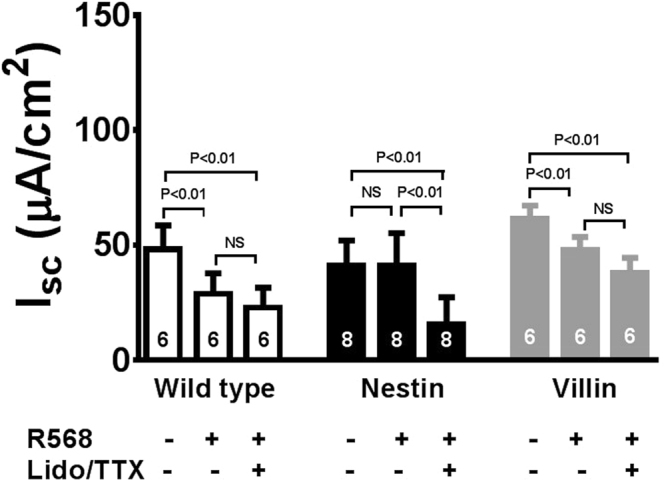

Under basal conditions, mucosal distension during normal digestion or mechanical stimulation during experimental preparations can activate neuronal reflex pathways in the ENS, evoking Cl− secretion20,31. This reflex-evoked Cl− secretion can be measured in Ussing chamber experiments as increases in TTX/lidocaine-sensitive short-circuit current (Isc)13. To test the hypothesis that CaSR is expressed on enteric neurons to restrict neurally mediated secretory responses, we generated a neuronal tissue-specific CaSR conditional knockout mouse line (i.e., nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice or nestin mice) using Cre recombinase. For comparison, we also generated an epithelial tissue-specific CaSR conditional knockout (i.e., villinCre/Casrflox/flox mice or villin mice). Colons from these knockouts were isolated, mounted onto Ussing chambers, and Cl− secretory Isc responses to R568 were measured and compared with their wild-type littermates. The results are shown in Fig. 1. Consistent with the presence of neurogenic Cl− secretion, a large TTX/lidocaine-sensitive Isc was detected in these mouse colons. In wild-type mice, R568 (10 µM, added to the serosal bath) inhibited basal secretory Isc and abolished the inhibitory effect of TTX/lidocaine (2 µM/1.6 mM, added to the serosal bath) on Isc. In neuronal CaSR knockout mice or nestin mice, however, R568 did not significantly inhibit Isc, although it caused significant inhibition on Isc in epithelial CaSR knockout mice or villin mice. In all three groups, inhibitory effects of TTX/lidocaine on basal Isc were unaffected [mean % inhibition of Isc by TTX/lidocaine in wild-type, nestin and villin mice: 55 ± 12% (6), 63 ± 7% (8) and 43 ± 8% (6), P > 0.05]. These results suggest that the calcimimetic acts on CaSR of enteric neurons, not mucosal cells, to inhibit TTX/lidocaine-sensitive electrolyte secretion by the intestine.

Figure 1.

R568 anti-secretory effects under basal conditions. Summarized are steady-state Isc changes in response to the sequential serosal additions of R568 (10 µM) and lidocaine (Lido, 1.6 mM)/TTX (2 µM). The R568 anti-secretory effect is present in colons of wild-type mice and mice expressing neuronal CaSR (villinCre/Casrflox/flox or villin mice) but is absent in mice lacking neuronal CaSR (nestinCre/Casrflox/flox or nestin mice). NS, no significance.

Calcimimetic inhibits cholera toxin-evoked Isc in mouse colon via CaSR on enteric neurons

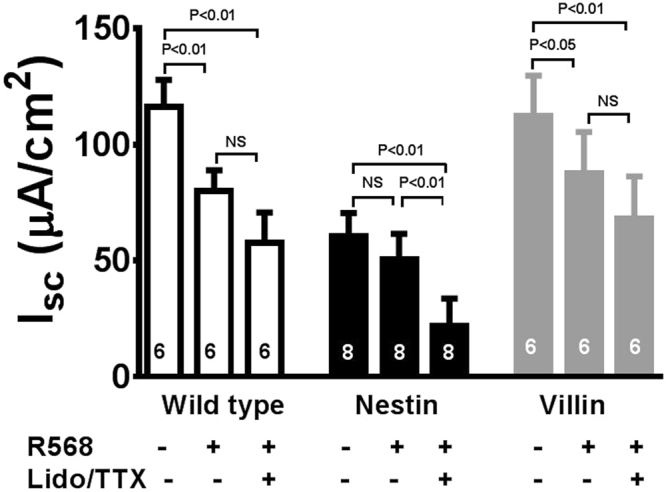

To strengthen the hypothesis that R568 acts on CaSR of enteric neurons to limit secretion, we also performed experiments using cholera toxin to enhance the neurally mediated secretory state. In a pilot study, we found that mouse colons did not survive the long (90 min) incubation required for cholera toxin to have an effect in Ussing chambers. Accordingly, we adopted a two-step protocol previously described by Gabriel et al.32, i.e., pretreating mouse intestines with cholera toxin, in vivo, in live animals to induce hypersecretion (see Methods), followed by examining Isc responses of pre-treated colons, ex vivo, in Ussing chambers (Fig. 2). Compared with non-cholera toxin controls, cholera toxin pretreatment significantly increased Isc in colons of wild-type mice and both knockouts (see Table 1). Subsequent treatment with R568 abrogated cholera toxin-induced increases in Isc in wild-type and villin mice, but not in nestin mice. In all three groups, inhibitory effects of TTX/lidocaine on cholera toxin-augmented Isc were unaffected [mean % inhibition of Isc by TTX/lidocaine in wild-type, nestin and villin mice: 51 ± 8% (6), 62 ± 11% (8) and 40 ± 12% (6), P > 0.05]. These results confirm the finding in Fig. 1, suggesting that this calcimimetic anti-secretory agent acts on CaSR of enteric neurons, not mucosal cells, to reduce cholera toxin-induced electrolyte secretion by the intestine.

Figure 2.

R568 anti-secretory effects under cholera toxin-stimulated conditions. Mouse intestines were pretreated with cholera toxin, in vivo, in live animals to induce hypersecretion (see Methods), followed by examining Isc changes of pre-treated intestines, ex vivo, in Ussing chambers. Summarized are steady-state Isc changes of these pretreated intestines in response to the sequential serosal additions of R568 (10 µM) and lidocaine (Lido, 1.6 mM)/TTX (2 µM). The R568 anti-secretory effect is present in colons of wild-type mice and mice expressing neuronal CaSR (villinCre/Casrflox/flox or villin mice) but is absent in mice lacking neuronal CaSR (nestinCre/Casrflox/flox or nestin mice). NS, no significance.

Table 1.

Isc responses to cholera toxin in wild-type and CaSR mutant mouse colons.

| Isc (µA/cm2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | nestin Cre/Casr flox/flox | villin Cre/Casr flox/flox | |

| Control | 48 ± 10 (6) | 41 ± 10 (8)nsNS | 65 ± 6 (6)ns |

| Cholera toxin | 116 ± 12 (6)** | 60 ± 10 (8)*,##,¶¶ | 113 ± 17 (6)**,ns |

Data shown are means ± SEM (n).

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

##P < 0.01, ns > 0.05 vs. Wild-type.

¶¶P < 0.01, NS > 0.05 vs. villinCre/Casrflox/flox.

Calcimimetic inhibits forskolin-evoked Isc in mouse colon via CaSR on enteric neurons

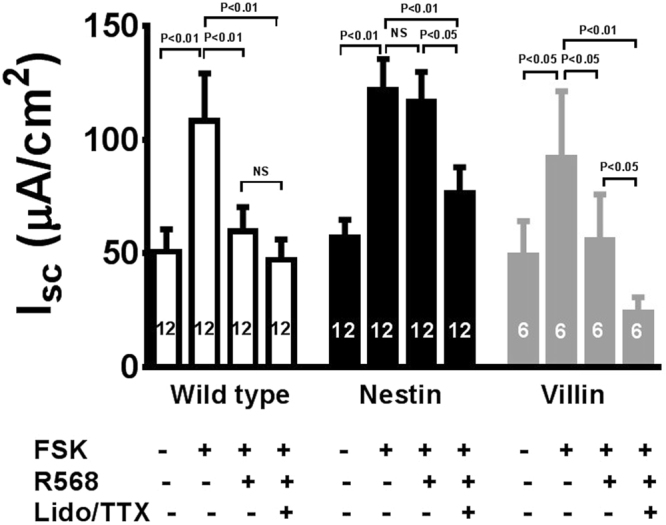

In colonic crypts18 as well as in kidney33 and parathyroid cells34, CaSR exerts its regulatory actions via reductions of the cyclic AMP. Thus, to provide insights into the messenger systems involved in the actions of the CaSR in enteric neurons, we also studied effects of R568 on forskolin-induced Isc (Fig. 3). We chose forskolin also because in enteric neurons this agent has long been shown to simulate the neuroexcitatory effects of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), substance P, VIP and many other neurotransmitters released in neuronal reflexes35. Indeed, forskolin (500 nM, added to the serosal bath) significantly increased Isc in colons of wild-type mice and both knockouts. Subsequent addition of R568 significantly diminished forskolin-induced increases in Isc in wild-type mice and villin mice, but not in nestin mice. In all three groups, inhibitory effects of TTX/lidocaine on forskolin-evoked Isc were unaffected [mean % inhibition of Isc by TTX/lidocaine in wild-type, nestin and villin mice: 52 ± 6% (12), 36 ± 11% (12) and 67 ± 8% (6), P > 0.05]. These results suggest that activation of adenylate cyclase by forskolin and subsequent elevation of intra-neuronal cyclic AMP mimic the effects of cholera toxin-induced neuronal cell excitation on Cl− secretion, thus supporting the possibility that reductions of cyclic AMP might be involved in the actions of this neural CaSR.

Figure 3.

R568 anti-secretory effects under forskolin-stimulated conditions. Mouse intestines were pretreated with forskolin (FSK, 500 nM, added to the serosal bath), ex vivo, in Ussing chambers to elevate cyclic AMP and excite neurons to induce hypersecretion. Following this pre-treatment, R568 (10 µM) and lidocaine (Lido, 1.6 mM)/TTX (2 µM) were subsequently added to the serosal solution of Ussing chambers with the sequence of their additions indicated. Summarized are steady-state Isc changes of these pretreated intestines and effects of R568 and lidocaine/TTX. R568 abolishes the forskolin’s excitatory effect in colons of wild-type mice and mice expressing neuronal CaSR (villinCre/Casrflox/flox or villin mice) but not in mice lacking neuronal CaSR (nestinCre/Casrflox/flox or nestin mice). NS, no significance.

Neural CaSR is required for enteric neurons to communicate with the mucosal epithelium

Enteric neurons communicate with the mucosal epithelium in not one- but two-way directions. In addition for the mucosa (e.g., EC cells) secreting neuroactive agents (e.g., 5-HT) to control the activity of enteric neurons, enteric neurons also release neurotransmitters (e.g., VIP, somatostatin) to influence the function of the mucosal cells (e.g., EC cells)36,37. Thus, after characterizing its role in regulating the functionality of enteric neurons, we asked if CaSR on enteric neurons also regulates the functions of the mucosal epithelium. For this, we compared Isc changes in response to cholera toxin (which was administered to the mucosal side) and forskolin (which was administered to the serosal side). The rationale is that cholera toxin requires mucosa to activate a secretory neural reflex whereas forskolin does not. Accordingly, if CaSR on enteric neurons regulated the functionality of the mucosa, then cholera toxin should increase Isc differently in nestin mice compared with wild-type and villin mice, whereas forskolin should have a similar effect on Isc in all three groups. Indeed, although both pro-secretory agents increased Isc in all three animal groups, cholera toxin increased Isc to a significantly lesser extent in nestin mice (Fig. 2 and Table 1), whereas forskolin had a similar effect on Isc in all three groups (Fig. 3 and Table 2). Thus, in nestin mice, the mean % increase in Isc induced by cholera toxin was only 20 ± 12% (8), which is significantly smaller than 141 ± 59% (6) in wild-type (P < 0.05) and 83 ± 28% (6) in villin mice (P < 0.05). In contrast, the mean % increases in Isc induced by forskolin were 126 ± 25% (12), 120 ± 23% (12), and 86 ± 29% (6), respectively (P > 0.05). These results suggest that, in addition to regulating neuronal function, the CaSR expressed by neuronal cells also modulates the function of the mucosa, highlighting the importance of this receptor in GI physiology and pathophysiology.

Table 2.

Isc responses to forskolin in wild-type and CaSR mutant mouse colons.

| Isc (µA/cm2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | nestin Cre/Casr flox/flox | villin Cre/Casr flox/flox | |

| Control | 50 ± 10 (12) | 57 ± 8 (12)ns | 49 ± 15 (6)ns |

| Forskolin | 108 ± 21 (12)** | 122 ± 14 (12)**,ns,NS | 92 ± 29 (6)* |

Data shown are means ± SEM (n).

**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 vs. Control.

ns P > 0.05 vs. Wild-type.

NS P > 0.05 vs. villinCre/Casrflox/flox.

Discussion

Our data confirm that CaSR in enteric neurons is functional and can modulate neurogenic secretory responses. Using a rat colon model, we have previously shown that the serosally applied calcimimetic R568 inhibits forskolin-induced secretory Isc in the absence, but not presence, of the neurotoxin TTX13, suggesting that this anti-secretory agent might act on the intestine via enteric neurons within the ENS. In the present study, we extend these observations by showing that in mouse colons this same small molecule compound also inhibits basal and secretagogue (forskolin and cholera toxin)-induced Isc in a neuronal CaSR-dependent manner, i.e., R568 inhibited basal or evoked secretory Isc in colons of wild type mice and mutant mice that contained CaSR in neurons (i.e., villinCre/Casrflox/flox mice), but not in colons of nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice in which CaSR in neuronal cells was eliminated, providing further support for potential roles that this neuronal CaSR may play in the control of ENS activity and GI function.

The primary function of the GI tract is to digest food and absorb nutrients. To aid in digestion, the GI tract secretes fluid. It is estimated that following the intake of a meal, intestinal secretion can be increased eightfold38. There is compelling evidence that the ENS has a major role in enhancing this secretory state20. This enhanced secretion helps lubricate the surface of the lumen of the intestine, ensuring the appropriate mixing and flow of digest along its length. Once digestion is completed and nutrients are extracted, these secretions along with released nutrients must be reabsorbed while also ensuring that further post-digestive secretions do not occur. These processes are highly regulated and coordinated; failure to do so may result in diseases such as mal-digestion, mal-absorption, constipation, or diarrhea. How these functions are regulated and coordinated remains a focus of study. We have presented evidence from this and other studies that CaSR may play a major role in the control of these processes (see a recent review by Tang et al.15). CaSR is a highly conserved G protein-coupled cell surface receptor (GPCR) that is coupled to multiple G proteins including Gq/11, Gi/o, and G12/13, and its downstream factors, and, when activated, turns on various signaling pathways regulating cellular behaviors. These include an increase of intracellular Ca2+, alteration of the intracellular cyclic AMP, phosphorylation of ERK1/2, and activation of small GTPase RhoA39. However, CaSR is an unusual GPCR in that it uses extracellular nutrients (e.g., calcium, polyamines, certain amino acids and peptides) as its ligands. Accordingly, unlike most other GPCRs, CaSR must function in the chronic presence of agonists. This is possible because CaSR adopts unusual mechanisms to regulate receptor expression, trafficking, and degradation40. For example, instead of inducing internalization and causing desensitization in other GPCRs, continuous elevation of agonist increases the number of CaSR in the plasma membrane via the so-called agonist-driven insertional signaling and sensitizes receptor function40. This is important because this unique property enables CaSR the ability to continuously monitor the ionic and nutritional compositions of the extracellular milieu in the gut and modulate the intestinal secretion/absorption in accordance with the status of digestion. Accordingly, local nutrient signals released from digestion, such as calcium, amino acids, and polyamines, can act on CaSR on neurons to function as a negative modulator of these physiological secretory actions and provides a mechanism for modulating net fluid movement during normal digestion. Based on this, we predict that over-activation of CaSR in this process may contribute to constipation whereas under-activation of CaSR may contribute to diarrhea. Indeed, people with high-calcium diets or taking excessive calcium are often constipated41, as are patients with hypercalcemia42. By contrast, those who are starved tend to hypersecrete in their small and large intestines43–49.

It is worth noting, however, that although this present study shows the primary effect of R568 is via neuronal CaSR, part of the inhibitory effect of this compound may be due to an action on epithelial CaSR. The latter is evidenced by the following: First, R568 produced a significantly less pronounced inhibitory effect on basal Isc in villinCre/Casrflox/flox knockouts than wild type mice [compare right versus left panels of Fig. 1; mean inhibition: 24 ± 5% (6) versus 40 ± 5% (6); P < 0.05], even though such a difference on cholera toxin [compare right versus left panels of Fig. 2; mean inhibition: 24 ± 7% (6) versus 29 ± 4% (6); P > 0.05] or forskolin stimulated Isc [compare right versus left panels of Fig. 3; mean inhibition: 40 ± 5% (6) versus 40 ± 5% (12); P > 0.05] was not statistically significant. Second, R568 reduced forskolin-evoked Isc and this clearly diminished the inhibitory effect of subsequent TTX/lidocaine addition in wild-type mice [Fig. 3 left panel; mean inhibition by TTX/lidocaine: 22 ± 5% (12)]. However, the ability of R568 to reduce the inhibitory effect of TTX/lidocaine was significantly less pronounced in villinCre/Casrflox/flox knockouts (Fig. 3 right panel; mean inhibition by TTX/lidocaine: 46 ± 10% (6); P < 0.05). This suggests that epithelial CaSR may be involved, albeit to a lesser extent, in the inhibitory effect of R568.

Also noted was the finding that R568 failed to inhibit basal and secretagogue-induced Isc in colons of nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice (Figs 1–3, middle panels). The reason is unknown. One possibility is the thickness of the tissue preparations used, which may prevent this hydrophobic calcimimetic drug from diffusing into the epithelium layer to access to the receptor50,51. An alternative explanation would be that the receptor function in the enterocyte might also be lost or its level may be down-regulated in this neuron-specific mutant mouse line. In support of this possibility, Crone et al. recently showed that the use of nestinCre mice also drove expression in the colonic epithelium52. Accordingly, the expression of Casr gene in the colonic epithelium may be reduced in nestinCre/Casrflox/flox knockouts. Finally, epithelial stem cell production of the many different types of epithelial cells is under neural control so that any mechanism that alters neural activity can be expected to modify the epithelium and whether this affects EC or EE cell numbers or properties is not known. The CaSR knockouts used here are whole of life effects and hence it might be expected that there are significant differences in neural regulation of epithelial differentiation and hence insensitivity to calcimimetics. This may also explain their reduced sensitivity to cholera toxin (see below).

What is the most surprising was the finding on the effect of cholera toxin in nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice. In these animals, cholera toxin increased Isc to a significantly lesser extent than it did in wild-type and villinCre/Casrflox/flox (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This suggests that this neural CaSR may also influence the function of the mucosa, particularly the EC cells. Generating an effective secretory response to cholera toxin requires not only activation of secretomotor reflexes but also release of 5-HT from EC cells53. Thus, two possibilities may exist in nestinCre/Casrflox/flox intestine: a defect occurred in the ENS or in the mucosa. The fact that only cholera toxin (which acts in the mucosa and ENS) but not forskolin (which acts in the ENS) caused the blunted Isc response seems to suggest the latter, rather than the former. Indeed, via synaptic connections, the mucosa (e.g., EC cells) communicates with enteric neurons in a not mono- but bi-directional manner54. In addition for EC cells secreting neuroactive agents (e.g., 5-HT) to control the activity of enteric neurons, enteric neurons also release neurotransmitters to influence the function and fate of EC cells. Numerous receptors for neurotransmitters have been shown to be present on the basolateral aspect of EC cells36,37. When stimulated, these receptors modify the release of 5-HT. While some receptors (e.g., GABA and somatostatin) inhibit, others (e.g., VIP/PACAP) enhance, 5-HT release. Thus, neurogenic influences on EC cells may be altered in nestinCre/Casrflox/flox intestines such that the balance is shifted to more inhibitory in these animals. In addition, EC cell proliferation and differentiation are under neural control. For example, enteric neurons may release PACAP/VIP to stimulate EC cell proliferation55. Thus, without influences from neuronal CaSR, EC cells may become hypoplastic and/or hypotrophic. Future studies need to characterize what exact changes occur to EC cells in nestinCre/Casrflox/flox intestines and understand how CaSR elimination from enteric neurons leads to such changes.

The mechanisms by which CaSR inhibits the ENS activity are currently under investigation. In a recent study, Sun et al. examined the R568 effect on the myenteric neuron c-fos expression, a biochemical measure of neuronal excitability, and found that activation of CaSR by R568 significantly reduced neuronal cell c-fos expression in colons of wild-type mice and villinCre/Casrflox/flox knockouts, but not nestinCre/Casrflox/flox knockouts30. Thus, one possibility would be to operate by reducing neuronal excitability. Consistent with this, we show in the present study that activation of CaSR on enteric neurons inhibited the neurogenic secretion caused by the neuroexcitatory agent forskolin (Fig. 3). Forskolin is known to excite enteric neurons via activation of neuronal membrane adenylyl cyclase and subsequent elevation of the intra-neuronal cyclic AMP, which inhibits Ca2+ influx and closes Ca2+-dependent K+ channels, causing membrane depolarization35. Thus, CaSR might inhibit neuronal excitability by reversing this cellular process through receptor-mediated inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and/or reduction cyclic AMP, as described in enterocytes10,11,18 and many other cell types39. Recent studies on CaSR mechanisms on neurons of the CNS also seem to support this possibility56.

Alternatively, CaSR, particularly those expressed on nerve terminals of the ENS, may exert its inhibitory effect on neurons through inhibition of voltage-gated sodium channels (Nav) and thereby synaptic transmission and neurotransmitter release, as in the CNS56. Decreases in Ca2+o, a primary ligand of CaSR, have long been recognized to increase the likelihood of action potential initiation57. The CaSR location in nerve terminals of enteric neurons13, the TTX/lidocaine-sensitive nature of the CaSR-mediated suppression of neurogenic secretion13 (present study), and the abolition of the veratridine-evoked Isc by R568 (Tang, unpublished observations) also seem to suggest this possibility. In the CNS, cyclic AMP regulates excitability/neurotransmission in two different pathways: action potential-dependent, which involves PKA-dependent phosphorylation and activation of Nav58, and action potential-independent, which involves PKA-independent Epac-dependent modifications of other mechanisms such as increasing Ca2+ influx59,60. Currently, it is unknown which pathway (s) is utilized by CaSR in the ENS.

Synaptic excitation is triggered by increases in intracellular Ca2+, which not only leads to the release of neurotransmitters but also increases synaptic H+ (co-released with neurotransmitters from vesicles) and Ca2+ (resulting from Ca2+/H+ exchange mediated via presynaptic plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase)61. While the primary function of neurotransmitters is to excite postsynaptic effector cells, we do not know the roles and fates of these ions. The finding that enteric neuronal activity was inhibited by calcimimetics revealed in the present and the previous studies30 leads us to speculate that these synaptic Ca2+ and H+ ions may represent an internal ‘brake’ to limit synaptic excitation. Considering the known effects on CaSR of Ca2+o (which activates receptor) and H+ (which inhibits receptor via allosteric modification of Ca2+o affinity)8, we further hypothesize that CaSR is the receptor that detects and transduces changes in these synaptic ions into changes in cellular excitability. Furthermore, the resultant changes in cellular activity can be of either the presynaptic neuron or the postsynaptic neuron/epithelial cell or both.

The finding of the present study may have important pathophysiological significances. Bacterial enterotoxins, such as cholera toxin and STa, enhance intestinal fluid secretion and cause severe diarrhea. They do so through both direct enterocyte generation of cyclic nucleotides and indirect stimulation of the ENS to release neurotransmitter secretagogues such as VIP. Remarkably, our studies show that nearly all the secretory responses induced by cholera toxin are reversed upon activation of CaSR, acting either on the enterocyte10,11,18 or on the ENS (present study). Based on these findings, we predict that whether a patient develops diarrhea or not is determined not only by the toxin that provokes it but also by the activity of CaSR that prevents it. We also predict that, when this CaSR-mediated anti-secretory protection is decreased or lost, such as in children with a negative calcium balance or nutrient deprivation, this and other diarrheal diseases would be anticipated to be more common. Additionally, the diarrheal symptoms would be more severe, and the disease duration would be longer, as shown62–64. This CaSR protection theory may also explain why increasing calcium intake is effective in reducing the severity and duration of diarrhea resulting from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli65 and other enterotoxin-producing infections66.

Effectively reducing the life-threatening intestinal fluid loss in enterotoxin-induced diarrhea remains a major challenge. The novel pathway for modulating intestinal Cl− secretion through the colonic CaSR may lead to new pharmaco-nutritional therapies for prevention or treatment of certain clinical diarrheal diseases (i.e., cholera and other cyclic nucleotide-associated diarrheal diseases). Although the present study was conducted in the colon, the finding should apply to the small intestine, as CaSR is similarly expressed in the epithelium9–12 and neurons9,13 of the small and large intestines. Similarly, the primary virulence factor and diarrhea inducer of the Vibrio cholerae cholera toxin affects both the small21–23 and large intestine (present study), including the human colon67, even if the non-invading pathogen colonizes primarily the small intestine. Given that ENS-mediated secretory response is also critically implicated in many other forms of diarrhea, including viral [e.g., rotavirus68], neurogenic [e.g., irritable bowel disease69], and immunogenic/inflammatory diarrhea [e.g., inflammatory bowel disease70], the CaSR-mediated inhibition of the ENS-dependent secretory response observed in the present study might be of clinical importance in treating those forms of diarrhea as well.

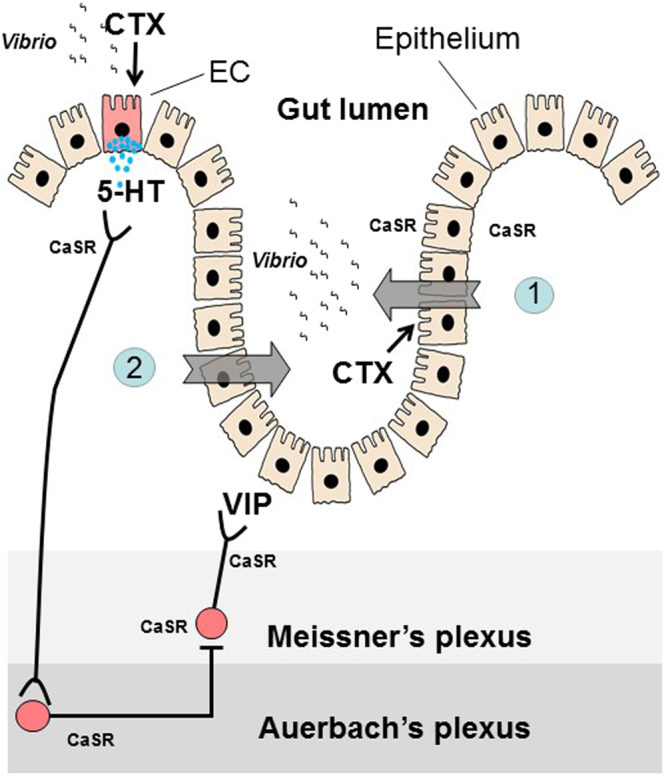

In light of the present study and previously published data10,11,13,18,29, we propose a new paradigm for CaSR inhibition of cholera toxin-induced hypersecretion (Fig. 4). According to this paradigm, cholera toxin produces its effect on electrolyte secretion by the intestine using two pathways and CaSR agonists block both pathways. First, cholera toxin induces a non-neuronal fluid secretory response due to binding of toxin directly to enterocytes, leading to the generation of the cyclic AMP, and this direct diarrhea-causing pathway is inhibited by activation of CaSR on enterocytes. Second, cholera toxin induces a neuronal secretory response by stimulation of enteric neurons in the ENS, and this indirect diarrhea-causing pathway is inhibited by activation of CaSR on these neurons. Besides enterocytes and neurons, the cholera toxin-induced hypersecretion also requires the release of 5-HT and other mediators from EC cells, and EC cells express CaSR. Future studies need to address whether the cholera toxin-evoked release of 5-HT from EC cells is blocked by activation of EC cell CaSR. Nonetheless, the ability of CaSR agonists to reduce cholera toxin-induced fluid secretion demonstrated in this and other studies highly suggests that this class of nutrients and drugs may provide a unique therapy for cholera and other secretory diarrheal diseases.

Figure 4.

Proposed dual-pathway model for CaSR inhibition of cholera toxin-induced hypersecretion in the intestine. Vibrio cholerae generates cholera toxin (CTX) to evoke hypersecretion using two pathways and CaSR agonists block both pathways. (1) CTX induces a non-neuronal fluid secretory response due to binding of toxin directly to enterocytes, leading to the generation of cyclic AMP and activation of CFTR and NKCC1. This direct secretory response is blocked by activation of CaSR on enterocytes, either apically or basolaterally, through enhancing cyclic nucleotide destruction. (2) CTX induces a neurally mediated secretory response by stimulation of secretomotor reflex pathways in the ENS. This neurally mediated indirect secretory response is blocked by activation of CaSR on neurons (cell bodies, indicated in filled red circles, and nerve terminals, indicated in black lines) possibly by modulations of cyclic nucleotide metabolism and ion channel properties, leading to inhibition of neuronal cell excitability and/or synaptic excitation (see text for more discussions). Besides enterocytes and neurons, the cholera toxin-induced hypersecretion requires the release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT, indicated by blue dots) from enterochromaffin (EC, indicated in red) cells of the mucosa, which also express CaSR. It remains to be addressed whether cholera toxin-evoked release of 5-HT from EC cells is blocked by CaSR on EC cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Experiments were performed using non-fasting male/female C57BL/6 mice (wild-type and Casr mutants). Mice lacking CaSR expression in intestinal epithelial cells (villinCre/Casrflox/flox mice) and mice lacking CaSR expression in intestinal neurons (nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice) and their wild-type littermates were bred and maintained in-house at the University of Florida Communicore Animal Facility. Mutant villinCre/Casrflox/flox mice and nestinCre/Casrflox/flox mice were generated as previously described30,71. Briefly, CaSR flox/flox mice were bred with transgenic mice expressing Cre Recombinase under the control of the villin 1 or nestin promoter and genotyped prior to all experiments after an approximate 10–12 generations. Mice were used at 5–10 weeks of age in accordance with the Animal Welfare Act and the Public Health Policy on Humane Care. Animals were fed and maintained on regular chow (Harlan) with free access to water before sacrifice. In some experiments, mice were induced for hypersecretion by cholera toxin (10 µg in 100 µl 7% NaHCO3 administered via intra-gastric gavage72) 6 hrs prior to sacrifice. Cholera toxin-induced hypersecretion/diarrhea was confirmed by the formation of loose stool and/or accumulation of clear fluid in the intestines as previously described32,72–74. Animals were sacrificed with standard CO2 inhalation and killed by cervical dislocation before colons were removed. The use of animals, as well as the protocols for cholera toxin treatment and colon tissue isolation, was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC# 201307567) at University of Florida.

Ussing chamber Isc measurements from colonic segments

Segments of colons were quickly isolated. Segments were cut open along the mesenteric border into a flat sheet and flushed with ice-cold basal HEPES-Ringer solution containing 1.25 mM Ca2+ and Mg2+. Intact full-thickness segments containing all the layers of middle colons (between proximal and distal colons) were used. Proximal and distal colons were distinguished grossly by the presence of oblique mucosal folds in the former and longitudinal folds in the latter. In a pilot study, we tested proximal and distal colons separately and found no significant difference in their Isc responses to R568. The intestinal segments were then mounted between two halves of a modified Ussing chamber (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) and short-circuited continuously by a voltage clamp (VCC MC6, Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) with correction for solution resistance. The exposure area was 0.3 cm2. The mucosal and serosal surfaces of the tissue were bathed in reservoirs with 3–5 ml HEPES-Ringer solution containing 110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM CaCl2, 1.25 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 22 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, maintained at 37 °C and continuously bubbled with 100% O2. On average, an interval of 10 min elapsed between euthanizing the animal and mounting the tissue into the chamber. Tissues were allowed a minimum of 15-minute stabilization and basal recording period before test reagents or vehicles were added to the mucosal and/or serosal sides of the intestine. Trans-epithelial potentials generated by the tissues were continuously clamped to 0 mV, except for brief interruption to recording open-circuit potential (VT, mV). Tissue conductance (GT, mS/cm2) was calculated as the ratio of the measured short-circuit current (Isc, μA/cm2) to VT from Ohm’s law. Data were acquired via DATAQ™ instruments and were stored on a PC and processed using the program Acquire & Analyze™. Isc is defined as the current flow through the tissue when the tissue is short-circuited (i.e., when the voltage across the tissue is zero). Magnitudes (μA/cm2) of change in Isc were determined before and after additions of test reagents or vehicle, with a positive sign representing net cation absorption and/or net anion secretion, and % changes in Isc were calculated. In the present study, a two-step protocol was employed to induce hypersecretion by cholera toxin. To estimate the % changes in Isc induced by cholera toxin, the basal Isc from colons that were not pretreated with cholera toxin were pooled and used as controls.

In a pilot study, it was found that Isc in mouse colons was less sensitive to TTX. Thus, in studies involving mouse colons, TTX was used in combination with lidocaine, another inhibitor of neural activity26. For measurements of TTX/lidocaine-sensitive neurally mediated Isc, 2 μM TTX and 1.6 mM lidocaine were applied to the serosal solutions and the differences in stable Isc before and after TTX/lidocaine treatment were compared and calculated and were defined as TTX/lidocaine-sensitive Isc. According to a pilot experiment in which a dose-response effect on Isc by TTX/lidocaine was sought, these doses of TTX and lidocaine were the lowest concentrations that maximally blocked the activity of the ENS without directly affecting the function of the epithelium13,18,25. Previous studies using Cl− free Ringer solutions and pharmacologic inhibitors established that under present experimental conditions both the basal and secretagogue-stimulated Isc primarily reflected Cl− secretion13.

Chemicals

Forskolin, veratridine, cholera toxin and lidocaine were obtained from Sigma, and stock solutions were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (forskolin, veratridine) or in water (cholera toxin). TTX was purchased from Enzo Life Science (Plymouth Meeting, PA), and 2 mM stock solutions were prepared in 10 mM acetic acid. R568 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MI), and 100 mM stock solutions were prepared in DMSO.

Statistical Analysis

Values are given as means ± SEM of n experiments. Statistical comparisons between two means were performed by Student’s t-test, whereas comparisons among multiple means were by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Both tests were performed either using Microsoft Excel 2016 for Windows or using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to Dr. Tao Huang, Dr. Peng Yi and Mr. Suman Donepudi for technical assistance on short-circuit current recordings and Dr. Fred Gorelick at Yale University and Dr. Bryon Petersen at University of Florida for discussing experiments and reviewing the final manuscript. Part of experiments was performed in Dr. Fred Gorelick’s laboratory at the VA hospital of West Haven, CT. The tissue-specific Casr−/− mice were kindly provided by Dr. Wenhan Chang at Endocrine Research, VA Medical Center, University of California at San Francisco. This work was supported in part by Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health HD079674 (SXC), Children’s Miracle Network (SXC), and NIH T32 DK 007017 in Investigative Gastroenterology.

Author Contributions

S.X.C. conceptualized the study, L.T., L.J., and S.X.C. designed the study, L.T., L.J., E.P., M.E.M., and S.X.C. performed the experiments, L.T., L.J., and S.X.C. analyzed the data, and L.T. and S.X.C. drafted and revised the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Black R, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2008;375:1969–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore S, Lima AAM, Guerrant R. Infection: Preventing 5 million child deaths from diarrhea in the next 5 years. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:363–364. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown EM, et al. Cloning and characterization of an extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor from bovine parathyroid. Nature. 1993;366:575–580. doi: 10.1038/366575a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:239–297. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nearing J, et al. Polyvalent cation receptor proteins (CaRs) are salinity sensors in fish. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 2002;99:9231–9236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152294399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riccardi D, et al. Cloning and functional expression of a rat kidney extracellular calcium/polyvalent cation-sensing receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 1995;92:131–135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.1.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sands JM, et al. Apical extracellular calcium/polyvalent cation-sensing receptor regulates vasopressin-elicited water permeability in rat kidney inner medullary collecting duct. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:1399–1405. doi: 10.1172/JCI119299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tfelt-Hansen J, Brown E. The calcium-sensing receptor in normal physiology and pathophysiology: a review. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2005;42:35–70. doi: 10.1080/10408360590886606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chattopadhyay N, et al. Identification and localization of extracellular Ca(2+)-sensing receptor in rat intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1998;274:G122–130. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.1.G122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng SX, Geibel J, Hebert S. Extracellular polyamines regulate fluid secretion in rat colonic crypts via the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:148–158. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng SX, Okuda M, Hall A, Geibel JP, Hebert SC. Expression of calcium-sensing receptor in rat colonic epithelium: evidence for modulation of fluid secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2002;283:G240–250. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00500.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gama L, Baxendale-Cox LM, Breitwieser GE. Ca2+-sensing receptors in intestinal epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1997;273:C1168–1175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng SX. Calcium-sensing receptor inhibits secretagogue-induced electrolyte secretion by intestine via the enteric nervous system. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G60–G70. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00425.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gwynne RM, Ly K, Parry LJ, Bornstein JC. Calcium sensing receptors mediate local inhibitory reflexes evoked by L-phenylalanine in Guinea pig jejunum. Front. Physiol. 2017;8:991. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang L, et al. The Extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in the intestine: evidence for regulation of colonic absorption, secretion, motility, and immunity. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:245. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hebert S, Cheng S, Geibel J. Functions and roles of the extracellular Ca2+-sensing receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. Cell Calcium. 2004;35:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheinin Y, et al. Immunocytochemical localization of the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor in normal and malignant human large intestinal mucosa. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2000;48:595–602. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geibel J, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor abrogates secretagogue-induced increases in intestinal net fluid secretion by enhancing cyclic nucleotide destruction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.USA. 2006;103:9390–9397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602996103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9:286–294. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooke HJ. Neurotransmitters in neuronal reflexes regulating intestinal secretion. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000;915:77–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Field M. Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:931–943. doi: 10.1172/JCI200318326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundgren O. Enteric nerves and diarrhoea. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;90:109–120. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.900301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burleigh DE, Borman RA. Evidence for a nonneural electrogenic effect of cholera toxin on human isolated ileal mucosa. Dig. Dis.Sci. 1997;42:1964–1968. doi: 10.1023/A:1018835815627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorrot M, Vasseur M. How do the rotavirus NSP4 and bacterial enterotoxins lead differently to diarrhea? Virol. J. 2007;4:31. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lundgren O, et al. Role of the enteric nervous system in the fluid and electrolyte secretion of rotavirus diarrhea. Science. 2000;287:491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cassuto J, Jodal M, Tuttle R, Lundgren O. On the role of intramural nerves in the pathogenesis of cholera toxin-induced intestinal secretion. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1981;16:377–384. doi: 10.3109/00365528109181984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cassuto J, Jodal M, Lundgren O. The effect of nicotinic and muscarinic receptor blockade on cholera toxin induced intestinal secretion in rats and cats. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1982;114:573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massy ZA, Henaut L, Larsson TE, Vervloet MG. Calcium-sensing receptor activation in chronic kidney disease: effects beyond parathyroid hormone control. Semin. Nephrol. 2014;34:648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang L, et al. Calcium-sensing receptor stimulates Cl–and SCFA-dependent but inhibits cAMP-dependent HCO3− secretion in colon. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2015;308:G874–883. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00341.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun X, Tang L, Winesett S, Chang W, Cheng SX. Calcimimetic R568 inhibits tetrodotoxin-sensitive colonic electrolyte secretion and reduces c-fos expression in myenteric neurons. Life Sci. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hubel KA. Intestinal nerves and ion transport: stimuli, reflexes, and responses. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1985;248:G261–271. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1985.248.3.G261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gabriel SE, Brigman KN, Koller BH, Boucher RC, Stutts MJ. Cystic fibrosis heterozygote resistance to cholera toxin in the cystic fibrosis mouse model. Science. 1994;266:107–109. doi: 10.1126/science.7524148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Jesus Ferreira MC, Bailly C. Extracellular Ca2+ decreases chloride reabsorption in rat CTAL by inhibiting cAMP pathway. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 1998;275:F198–203. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.2.F198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen CJ, Barnett JV, Congo DA, Brown EM. Divalent cations suppress 3′,5′-adenosine monophosphate accumulation by stimulating a pertussis toxin-sensitive guanine nucleotide-binding protein in cultured bovine parathyroid cells. Endocrinology. 1989;124:233–239. doi: 10.1210/endo-124-1-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nemeth PR, Palmer JM, Wood JD, Zafirov DH. Effects of forskolin on electrical behaviour of myenteric neurones in guinea-pig small intestine. J. Physiol. 1986;376:439–450. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Racke K, Schworer H. Regulation of serotonin release from the intestinal mucosa. Pharmacol. Res. 1991;23:13–25. doi: 10.1016/S1043-6618(05)80101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Pfragner R, Eick GN, Champaneria MC. The functional characterization of normal and neoplastic human enterochromaffin cells. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:2340–2348. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang, E. B. & Rao, M. C. in Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract (ed Johnson, L. R.) 2027–2081 (Raven, 1994).

- 39.Conigrave AD, Ward DT. Calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR): pharmacological properties and signaling pathways. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;27:315–331. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Breitwieser GE. The calcium sensing receptor life cycle: trafficking, cell surface expression, and degradation. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;27:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prince RL, Devine A, Dhaliwal SS, Dick IM. Effects of calcium supplementation on clinical fracture and bone structure: results of a 5-year, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in elderly women. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166:869–875. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ragno A, et al. Chronic constipation in hypercalcemic patients with primary hyperparathyroidism. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;16:884–889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sagmanligil V, Levin RJ. Electrogenic ion secretion in proximal, mid and distal colon from fed and starved mice. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1993;106:449–456. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(93)90237-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nzegwu HC, Levin RJ. Fluid hypersecretion induced by enterotoxin STa in nutritionally deprived rats: jejunal and ileal dynamics in vivo. Exp. Physiol. 1994;79:547–560. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1994.sp003787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young A, Levin RJ. Intestinal hypersecretion of the refed starved rat: a model for alimentary diarrhoea. Gut. 1992;33:1050–1056. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Young A, Levin RJ. Diarrhoea of famine and malnutrition: investigations using a rat model. 1. Jejunal hypersecretion induced by starvation. Gut. 1990;31:43–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Young A, Levin RJ. Diarrhoea of famine and malnutrition–investigations using a rat model. 2–Ileal hypersecretion induced by starvation. Gut. 1990;31:162–169. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helweg-Larsen P, et al. Famine disease in German concentration camps; complications and sequels, with special reference to tuberculosis, mental disorders and social consequences. Acta Psychiatr. Neurol. Scand. Suppl. 1952;83:1–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levin RJ. The diarrhoea of famine and severe malnutrition–is glucagon the major culprit? Gut. 1992;33:432–434. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.4.432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clarke L. A guide to Ussing chamber studies of mouse intestine. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G1151–1166. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90649.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cox HM, Cuthbert AW, Hkanson R, Wahlestedt C. The effect of neuropeptide Y and peptide YY on electrogenic ion transport in rat intestinal epithelia. J. Physiol. 1988;398:65–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crone SA, Negro A, Trumpp A, Giovannini M, Lee KF. Colonic epithelial expression of ErbB2 is required for postnatal maintenance of the enteric nervous system. Neuron. 2003;37:29–40. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farthing MJ. Enterotoxins and the enteric nervous system - a fatal attraction. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2000;290:491–496. doi: 10.1016/S1438-4221(00)80073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bellono NW, et al. Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways. Cell. 2017;170:185–198 e116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lauffer JM, et al. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide modulates gastric enterochromaffin-like cell proliferation in rats. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:623–635. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones BL, Smith SM. Calcium-sensing receptor: a key target for extracellular calcium signaling in neurons. Front. Physiol. 2016;7:116. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Frankenhaeuser B, Hodgkin AL. The action of calcium on the electrical properties of squid axons. J. Physiol. 1957;137:218–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scheuer T. Regulation of sodium channel activity by phosphorylation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2011;22:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miura Y, Naka M, Matsuki N, Nomura H. Differential calcium dependence in basal and forskolin-potentiated spontaneous transmitter release in basolateral amygdala neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;529:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoshihara M, Suzuki K, Kidokoro Y. Two independent pathways mediated by cAMP and protein kinase A enhance spontaneous transmitter release at Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8315–8322. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08315.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sinning A, Hubner CA. Minireview: pH and synaptic transmission. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1923–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Black RE, Brown KH, Becker S. Malnutrition is a determining factor in diarrheal duration, but not incidence, among young children in a longitudinal study in rural Bangladesh. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1984;39:87–94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baqui AH, et al. Cell-mediated immune deficiency and malnutrition are independent risk factors for persistent diarrhea in Bangladeshi children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;58:543–548. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.4.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fraebel J, et al. Extracellular calcium dictates onset, severity, and recovery of diarrhea in a child with immune-mediated enteropathy. Front. Pediatr. 2018;6:7. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bovee-Oudenhoven IMJ, Lettink-Wissink MLG, Van Doesburg W, Witteman BJM, Van Der Meer R. Diarrhea caused by enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection of humans is inhibited by dietary calcium. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:469–476. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(03)00884-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng SX, Bai HX, Gonzalez-Peralta R, Mistry PK, Gorelick FS. Calcium ameliorates diarrhea in immunocompromised children. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013;56:641–644. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182868946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Speelman P, Butler T, Kabir I, Ali A, Banwell J. Colonic dysfunction during cholera infection. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(86)80012-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wickelgren, I. How rotavirus causes diarrhea. Science 287, 409, 411–409, 411 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Wood JD. Histamine, mast cells, and the enteric nervous system in the irritable bowel syndrome, enteritis, and food allergies. Gut. 2006;55:445–447. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.079046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Margolis KG, et al. Enteric neuronal density contributes to the severity of intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:588–598. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rey O, Bikle CW, Rozengurt D, Young N, Rozengurt SH. E. Negative cross-talk between calcium-sensing receptor and β-catenin signaling systems in colonic epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:1158–1167. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.274589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richardson SH, Kuhn RE. Studies on the genetic and cellular control of sensitivity to enterotoxins in the sealed adult mouse model. Infect. Immun. 1986;54:522–528. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.2.522-528.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gabriel SE, et al. A novel plant-derived inhibitor of cAMP-mediated fluid and chloride secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 1999;276:G58–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.1.G58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thiagarajah JR, Broadbent T, Hsieh E, Verkman AS. Prevention of toxin-induced intestinal ion and fluid secretion by a small-molecule CFTR inhibitor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:511–519. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.