Abstract

Background:

As the number of cartilage restoration procedures is increasing, so is the number of revision procedures. However, there remains limited information on the reasons for failure of primary cartilage restoration procedures.

Purpose:

To determine the common modes of failure in primary cartilage restoration procedures to improve surgical decision making and patient outcomes.

Study Design:

Case series; Level of evidence, 4.

Methods:

Patients who presented for revision after failed cartilage repair surgery were evaluated for factors contributing to failure of the primary procedure. All revision cases performed by a single surgeon at a tertiary center for failed cartilage restoration over a 6-year time frame were identified. In all cases, the medical records, preoperative radiographs, and magnetic resonance imaging scans were reviewed by 2 experienced cartilage surgeons. The cause for failure was categorized as malalignment, meniscal deficiency, graft or biologic failure, or instability. Univariate and descriptive statistics regarding patient demographics, index procedure, lesion location and size, and mechanism of failure were analyzed.

Results:

A total of 59 cases in 53 patients (32 male, 21 female) met the inclusion criteria. The mean patient age at the time of revision was 27.6 years, and the mean body mass index was 28.4 kg/m2. Failed index surgical procedures included 35 microfractures (59%), 12 osteochondral allograft transplantations (20%), 10 osteochondral autograft transfers (17%), 2 nonviable osteochondral allografts (3%), and 2 particulated juvenile chondral allografts (3%). The mean lesion size was 4.4 cm2. Reasons for failure included 33 cases with untreated malalignment (56%), 16 with graft failure (27%), 11 with untreated meniscal deficiency (19%), and 3 with untreated instability (5%); 4 cases demonstrated multiple reasons for failure.

Conclusion:

The most commonly recognized reason for failure was untreated malalignment. While biologic and graft failures will occur, the majority of failures were attributed to untreated background factors such as malalignment, meniscal deficiency, and instability. The stepwise approach of considering and addressing alignment, meniscal volume, and stability remains essential in cartilage restoration surgery.

Keywords: revision cartilage restoration, failed cartilage, malalignment, meniscal deficiency

It has been reported that focal cartilage defects impair quality of life in a similar fashion to severe osteoarthritis, causing long-term deficits in knee function.14 When nonoperative management fails, surgery may be indicated, with a variety of surgical options available to treat cartilage lesions. Overall, these interventions have been shown to improve quality of life and be cost-effective.24 Palliative treatment options offer limited and short-term symptom relief for cartilage defects, but articular cartilage restoration has demonstrated cost-effectiveness in reducing pain and functional disability.11,24 A variety of surgical options are available to treat cartilage lesions, and over 90,000 cartilage repair and restoration procedures were performed in the United States in 2010.22 Surgical options include microfracture, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transfer (OAT), osteochondral allograft transplantation (OCA), and particulated chondral tissue transplantation.8 Microfracture remains the most commonly performed procedure for cartilage defects.23

While these procedures have demonstrated satisfactory results, not all patients do well. Many patients have relevant abnormalities in addition to the isolated cartilage defect, such as patellar maltracking/instability, malalignment, meniscal deficiency, and instability of the tibiofemoral articulation.5 It is critical to understand how the cartilage defect occurred before considering any attempt at restoration surgery. Treatment with cartilage restoration may fail or outcome durability may be compromised if all possible influential factors are not corrected.

In addition, the incidence of articular cartilage defects, the number of surgical procedures, and the variety of techniques have all risen over the past 2 decades. More surgeons are being trained in these complex procedures with narrow indications, including many who do not subspecialize in cartilage restoration. This is comparable with trends in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, the majority of which are performed by surgeons who perform fewer than 10 ACL procedures per year.20,38 The most common reason for failure of ACL reconstruction is technical error with misplacement of the femoral socket by the surgeon.30,40 On the other hand, the mode of failure in cartilage repair surgery has not been well elucidated.

As a result of the growing number of primary cartilage procedures, revision surgery will also be more common. These revision procedures may have satisfactory outcomes, but they are typically inferior to those of initial cartilage restoration.17 Consequently, it would be instructive to evaluate the current modes of failure to optimize patient outcomes and limit the number of failures. The purpose of the present study was to determine the mode of failure of a consecutive series of failed primary cartilage repair procedures presenting to a specialized cartilage clinic at a single tertiary referral center. We hypothesized that a large number of failures are caused by unrecognized or untreated concomitant influential factors, such as malalignment, meniscal deficiency, and instability.

Methods

With institutional review board approval, patients who underwent revision surgery after failed cartilage repair between September 2011 and May 2017 were identified. Inclusion criteria consisted of all referred patients undergoing revision cartilage surgery by the first author (A.J.K.) at a single institution in the abovementioned time period. Exclusion criteria consisted of (1) patients presenting with failed cartilage surgery who were not candidates for revision cartilage surgery, (2) patients who required arthroplasty, and (3) patients choosing not to participate in the research. Patients who were not candidates for revision cartilage surgery were those with generalized degenerative changes and osteoarthritis of the knee, leading to nonoperative management or arthroplasty after their index cartilage procedure.

Cases were reviewed by 2 fellowship-trained experts in cartilage surgery in a blinded fashion to arrive at a consensus for the cause of failure. Failure was defined as a lack of improvement of preoperative symptoms including pain, function, activity level, and overall quality of life, leading to an indication for revision surgery. Index (failed) surgical procedures were performed at outside institutions and included microfracture, OAT, OCA, nonviable/decellularized osteochondral allograft (Chondrofix; Zimmer Biomet), and particulated juvenile chondral allograft (DeNovo NT Natural Tissue Graft; Zimmer Biomet). All revision procedures were performed by a single surgeon (A.J.K.) and included OAT, OCA, high tibial osteotomy, tibial tubercle osteotomy (TTO), ACI, distal femoral osteotomy, medial meniscal allograft transplantation, and particulated juvenile chondral allograft.

A total of 53 patients, comprising 59 failed cases, were identified for this review of prospectively collected data. Basic demographic information, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and level of education, was collected from the medical records for all cases. Surgical details, including size and location of the lesion, laterality, type of failed intervention, and revision strategy, were gathered from preoperative and intraoperative notes. Patients with failure of bilateral cartilage restoration procedures and those who underwent repeat revision procedures were eligible for inclusion. Lesion dimension data were available for 53 of the 59 failed cases and were combined from all anatomic locations of the knee joint. Surgical notes in all cases provided maximal width and height dimensions (in mm), which were used to calculate a total lesion area estimate.

The mechanism of failure was determined by physical examination, imaging (before and after the index procedure), and intraoperative findings during revision surgery. While imaging performed before index surgery at outside institutions varied, standard anteroposterior, lateral, patellar (sunrise or Merchant), and full-length standing radiographs were obtained in addition to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans in preparation for revision surgery.

Mechanisms of failure were categorized into 4 broad categories:

Malalignment: defined as ≥5° of mechanical axis deviation.10,15

Meniscal deficiency: defined as <50% functioning meniscal tissue.

Instability: defined as unaddressed or persistent clinically symptomatic instability. In the patellofemoral joint, this was typically a patellar subluxation/dislocation that required medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction and/or TTO during revision surgery. In the femorotibial joint, this was typically persistent instability after ACL reconstruction requiring revision ACL reconstruction.

Graft failure: defined as biologic failure of the index cartilage repair or restoration procedure without other identified contributing factors.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics, including demographics and risk factors for cartilage failure, were summarized using descriptive statistics including means, SDs, and percentages, as appropriate. Descriptive statistics predominated because of the nature of this case series of failed procedures and referrals to a tertiary surgical center. Where appropriate, proportions were compared using chi-square testing. Statistical analysis was performed with R 3.4.0 (R Core Team). P values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Fifty-nine failed cartilage procedures in 53 patients were surgically revised between September 2011 and May 2017. The mean patient age at the time of revision surgery was 27.6 years (range, 14.0-49.0 years). The study sample included 32 male (60%) and 21 female (40%) patients. The mean duration from failed index surgery to revision was 41.5 ± 38.4 months (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics at the Time of Revisiona

| Value | |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 27.6 ± 9.0 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 32 (60) |

| Female | 21 (40) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 5.3 |

| Laterality, n (%) | |

| Right | 32 (54) |

| Left | 27 (46) |

| Time to revision, mo | 41.5 ± 38.4 |

aData are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise specified.

Failed index surgery included 35 microfractures (59%), 12 OCAs (20%), 10 OATs (17%), 2 nonviable osteochondral allografts (3%), and 2 particulated juvenile chondral allografts (3%) (Table 2). Thirty-two patients had lesions involving the medial femoral condyle (54%), 21 involving the lateral femoral condyle (36%), 12 involving the patella (20%), and 9 involving the trochlea (15%) (Table 3). Forty-eight failures involved lesions affecting only 1 area of the knee joint (81%), 7 affected 2 regions (12%), and 4 affected 3 regions (7%).

TABLE 2.

Failed Index Cartilage Procedures

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Primary procedures | |

| Microfracture | 35 (59) |

| Osteochondral allograft transplantation | 12 (20) |

| Osteochondral autograft transfer | 10 (17) |

| Particulated juvenile chondral allograft (DeNovo) | 2 (3) |

| Nonviable osteochondral allograft (Chondrofix) | 2 (3) |

| Totala | 61 |

| Concurrent procedures | |

| Tibial tubercle osteotomy | 14 (24) |

| High tibial osteotomy | 12 (20) |

| Distal femoral osteotomy | 7 (12) |

| Lateral meniscal allograft transplantation | 7 (12) |

| Medial meniscal allograft transplantation | 3 (5) |

| Meniscal repair | 2 (3) |

| Otherb | 3 (5) |

| Totalc | 48 |

aOne patient underwent microfracture, DeNovo, and Chondrofix.

bOther included 2 patients who underwent medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction and 1 patient who underwent revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

cTwo patients underwent multiple concomitant procedures at the time of revision.

TABLE 3.

Location of Casesa

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Medial femoral condyle | 32 (54) |

| Lateral femoral condyle | 21 (36) |

| Patella | 12 (20) |

| Trochlea | 9 (15) |

aFour failed cases involved lesions at 3 locations, and 7 involved lesions at 2 locations; the remainder involved 1 lesion.

The reason for index surgery failure was divided into 4 categories as follows: 33 due to malalignment (56%), 11 due to meniscal deficiency (19%), 16 due to graft failure (27%), and 3 due to instability (5%) (Table 4). Four of the 59 failed cases involved more than 1 failure mechanism. Six patients had bilateral disease (11%). Of these, 1 underwent simultaneous revisions of both sides, whereas the remaining revisions were performed serially. Ten of the index cases involved an initial insult that was traumatic in nature (17%). In total, 74 distinct lesions were found, accounting for the 59 failed cases. Dimension data in either the surgical or radiology note was available in 66 of these lesions, and the mean lesion size was 4.4 cm2.

TABLE 4.

Reason for Index Procedure Failurea

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Malalignment | 33 (56) |

| Graft failure | 16 (27) |

| Meniscal deficiency | 11 (19) |

| Instability | 3 (5) |

| Total | 63 |

aIn 4 of the 59 cases, 2 reasons of failure were cited.

Overall, the most common failed procedure was microfracture, and the majority failed because of malalignment. While most of the failures were attributable to 1 mechanism, 4 cases were found to have failed by 2 mechanisms. The most commonly affected region of the joint was the medial femoral condyle, followed by the lateral femoral condyle. Although some patients did have cartilage failure at multiple locations, the majority of patients only had 1 point of failure. The reasons for failure were statistically similar in distribution (P > .99) between outside institutions and the tertiary referral center (Table 5). Detailed patient data are organized in Table 6.

TABLE 5.

Reason for Failure of Index Procedures Performed at an Outside Hospital and the Tertiary Center

| Outside Hospital, n (%) | Tertiary Center, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Malalignment | 20 (50) | 12 (52) |

| Meniscal deficiency | 8 (20) | 4 (17) |

| Graft failure | 11 (28) | 6 (26) |

| Instability | 1 (3) | 1 (4) |

TABLE 6.

Patient Dataa

| Patient | Sex | Age at Revision, y | Side Affected | Failed Index Surgery | Lesion Location | Lesion Size, cm2 | Reason for Failure | Time From Index Surgery to Revision, mo | Revision Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 43 | R | MFX | MFC | 1.44 | Varus malalignment | — | OAT, HTO |

| 2 | F | 17 | L | OAT | LFC | 1.20 | Meniscal deficiency | 12.6 | OCA, LMAT |

| 3 | M | 31 | L | MFX | MFC | 1.00 | Varus malalignment | 40.0 | OAT, HTO |

| 4 | F | 24 | R | MFX | MFC | 1.65 | Varus malalignment | 31.7 | OAT, HTO |

| 5 | F | 34 | R | MFX | MFC | 1.12 | Varus malalignment | — | OAT, HTO |

| 6 | M | 20 | L | MFX | MFC | — | Varus malalignment | — | OAT, HTO |

| 7 | F | 20 | R | MFX | Patella | 1.44 | Patellar maltracking, graft failure (fibrocartilage) | 67.2 | MACI, TTO |

| 8 | F | 16 | L | OAT | LFC | 3.96 | Meniscal deficiency | — | OCA, LMAT |

| 9 | M | 39 | L | MFX | MFC | 6.25 | Varus malalignment | 30.8 | OCA, HTO |

| 10 | F | 14 | R | OAT | MFC | 3.30 | Varus malalignment | — | OCA, HTO |

| 11 | F | 32 | R | OAT | MFC | 4.50 | Meniscal deficiency | — | OCA, MMAT |

| 12 | F | 24 | R | OAT | MFC | — | Graft failure | 18.1 | OCA (preoperative weight loss) |

| 13 | M | 20 | L | MFX | LFC | 4.84 | Valgus malalignment | — | OCA, DFO |

| 14 | M | 17b | R | OCA | MFC | 6.00 | Graft failure | — | OCA |

| 17b | L | OCA | MFC | 6.00 | Graft failure | — | OCA | ||

| 19 | R | OCA | MFC | 6.72 | Graft failure | 15.6 | OCA | ||

| 21 | R | OCA | MFC | 6.00 | Graft failure | 24.8 | OCA | ||

| 15 | M | 14 | L | OAT | LFC | 2.00 | Meniscal deficiency | 7.7 | OCA, LMAT |

| 16 | M | 31 | L | OCA | LFC | — | Valgus malalignment | 4.2 | OCA, DFO |

| 17 | M | 32 | R | MFX, DeNovo, Chondrofix | MFC | 8.75 | Varus malalignment | 36.0 | OCA, HTO |

| 18 | F | 29 | R | OCA | MFC | 2.34 | Graft failure | 39.9 | ACI sandwich technique |

| 19 | M | 39 | L | MFX | MFC, LFC, trochlea | — | Graft failure | 120.9 | Multifocal OCA |

| 20 | M | 37 | R | Chondrofix | MFC | — | Varus malalignment, graft failure | 25.6 | HTO, OCA |

| 21 | F | 47 | L | MFX | MFC | 3.24 | Graft failure | 96.6 | OCA |

| 22 | M | 28 | R | OCA | LFC | 7.29 | Meniscal deficiency | — | OCA, LMAT |

| 23 | F | 20 | R | MFX | Patella | 4.40 | Patellar maltracking | 28.9 | DeNovo, TTO |

| 21 | L | MFX | Patella | 8.68 | Patellar maltracking | 44.8 | DeNovo, TTO | ||

| 24 | M | 26 | L | MFX | Patella | 5.00 | Patellar maltracking | 83.3 | DeNovo, TTO |

| 25 | F | 34 | L | DeNovo | Patella, trochlea, MFC | Patella: 3.12; trochlea: 1.30; MFC: 5.67 | Patellar maltracking | 40.5 | ACI, TTO |

| 35 | R | MFX | MFC, trochlea, patella | MFC: 4.00; trochlea: 1.68; patella: 4.20 | Patellar maltracking | 22.5 | ACI, TTO | ||

| 26 | M | 33 | L | MFX | MFC, patella | MFC: 3.60; patella: 6.80 | Varus malalignment | 3.1 | ACI, HTO |

| 33 | R | MFX | Patella, trochlea | Patella: 6.00; trochlea: 1.44 | Patellar maltracking | 5.8 | ACI, TTO | ||

| 27 | M | 22 | R | MFX | MFC | 1.00 | Patellar instability | 96.4 | ACI (patella), TTO, MPFLR |

| 28 | M | 20 | L | MFX | LFC | 5.00 | Valgus malalignment | 42.1 | DFO, ACI |

| 29 | F | 20 | R | MFX | Patella | 3.96 | Patellar instability | 74.8 | ACI, MPFLR |

| 30 | F | 32 | L | MFX | Patella | 3.75 | Patellar maltracking | 24.7 | ACI, TTO |

| 31 | M | 24 | R | OCA | LFC | 7.56 | Valgus malalignment | 4.5 | OCA, DFO |

| 32 | M | 33 | R | OAT | LFC | 3.24 | Valgus malalignment | — | OCA, DFO |

| 33 | M | 49 | L | MFX | MFC | 4.00 | Varus malalignment | 33.5 | OCA, HTO |

| 34 | M | 31 | L | MFX | MFC | 6.00 | Varus malalignment | 8.9 | OCA, HTO |

| 35 | M | 39 | L | MFX | Patella, MFC | Patella: 1.50; MFC: 5.29 | MFX for an osteochondral lesion (bone and cartilage) | — | OCA |

| 36 | M | 25 | R | OAT | LFC | 4.84 | Meniscal deficiency | — | Lateral meniscal root repair, OCA |

| 37 | M | 23 | L | MFX | LFC | 4.00 | Meniscal deficiency | 72.4 | LMAT, OCA (LFC) |

| 38 | M | 45 | R | MFX | MFC | 6.00 | MFX for an osteochondral lesion (bone and cartilage) | 7.3 | OCA |

| 39 | M | 25 | L | OAT | LFC | 1.00 | Meniscal deficiency | — | OAT (LFC), root repair |

| 40 | M | 23 | L | MFX | MFC | 6.25 | Graft failure | 113.5 | OCA |

| 41 | F | 22 | R | OCA | MFC | 5.29 | Meniscal deficiency | 35.9 | OCA, MMAT |

| 42 | F | 16 | L | MFX | LFC | — | Meniscal deficiency, valgus malalignment | 23.9 | DFO, LMAT |

| 43 | M | 18 | R | OCA | LFC | 8.00 | Valgus malalignment | 21.8 | DFO, OCA |

| 44 | M | 21 | R | OCA | LFC | 6.25 | Meniscal deficiency, ACLR failure | — | DFO, ACLR, MMAT |

| 45 | F | 36 | R | MFX | Patella | 4.00 | Patellar maltracking | 116.4 | Cartiform, TTO |

| 46 | M | 20 | R | OCA | MFC | 7.56 | Graft failure | — | OCA |

| 47 | F | 33 | R | MFX | Trochlea, MFC, LFC | Trochlea: 4.00; MFC: 1.60; LFC: 2.80 | Patellar maltracking | 4.1 | ACI, TTO |

| 48 | M | 30 | R | MFX | LFC, trochlea | LFC: 2.99; trochlea: 9.00 | Patellar maltracking | 8.0 | ACI, TTO |

| 49 | F | 22 | L | OAT | LFC | 4.84 | Meniscal deficiency | 59.9 | OCA, LMAT |

| 50 | M | 42 | R | MFX | Trochlea, MFC | Trochlea: 4.00; MFC: 8.00 | Graft failure | 54.9 | OCA |

| 51 | M | 32 | L | MFX | LFC, trochlea | LFC: 4.60; trochlea: 6.60 | Patellar maltracking | 2.6 | MACI, TTO |

| 52 | M | 42 | L | MFX | Trochlea, LFC | Trochlea: 5.06; LFC: 1.76 | Patellar maltracking | 12.5 | MACI, TTO |

| 53 | F | 36 | R | MFX | MFC | 5.94 | Graft failure | 166.0 | OCA |

aACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; Chondrofix, nonviable osteochondral allograft; DeNovo, particulated juvenile chondral allograft; DFO, distal femoral osteotomy; F, female; HTO, high tibial osteotomy; L, left; LFC, lateral femoral condyle; LMAT, lateral meniscal allograft transplantation; M, male; MACI, matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation; MFC, medial femoral condyle; MFX, microfracture; MMAT, medial meniscal allograft transplantation; MPFLR, medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction; OAT, osteochondral autograft transfer; OCA, osteochondral allograft transplantation; R, right; TTO, tibial tubercle osteotomy.

bSurgeries were performed simultaneously.

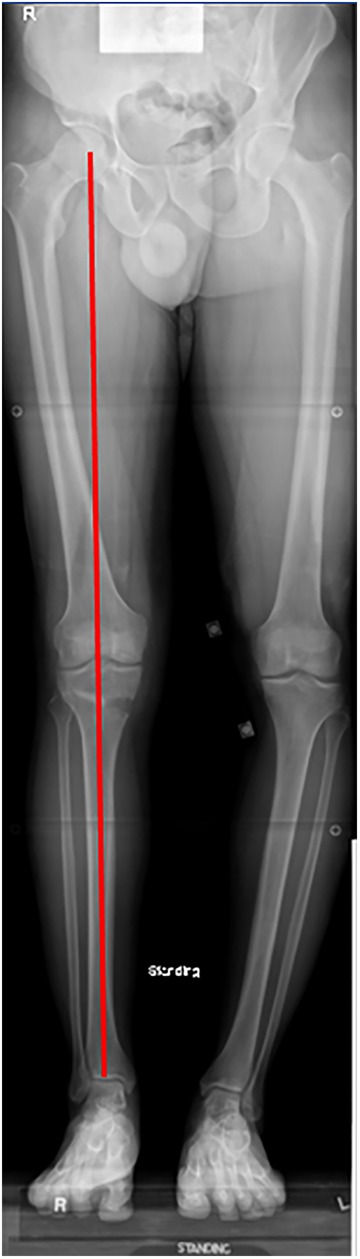

An illustrative example has been provided in Figures 1 to 3. This patient was a 32-year-old active golfer who developed an osteochondritis dissecans lesion and underwent excision and microfracture. Because microfracture failed, he received a cell-based particulated juvenile chondral allograft, which was later revised with a decellularized osteochondral allograft, which also failed. His initial radiographs demonstrated significant varus malalignment through the osteochondral lesion. At presentation to our cartilage center, he was offered surgery with valgus osteotomy and revision with a fresh osteochondral allograft. This case represents the only patient in this series with more than 1 procedure at presentation.

Figure 1.

(A) Initial anteroposterior and (B) posteroanterior radiographs demonstrating lucency (arrows) in the medial femoral condyle consistent with an osteochondral defect and a preserved joint space. (C) Long-leg radiograph demonstrating a significant 10° varus deformity with malalignment through the affected compartment.

Figure 2.

(A, B) Intraoperative photographs demonstrate failed osteochondral allograft transplantation (OCA). (C) Photograph after revision OCA with the snowman technique.

Figure 3.

Long-leg radiograph demonstrating correction of a varus deformity with valgus-producing proximal tibial osteotomy.

Discussion

Healthy articular cartilage is essential for normal pain-free knee function, and focal cartilage defects can impair quality of life similar to severe osteoarthritis.14 With the evolution of cartilage restoration techniques, the number of cartilage procedures performed in the United States has substantially increased, with an associated increase in failed cartilage surgical procedures and subsequent revisions.22 The purpose of this study was to determine the mode of failure for primary cartilage procedures referred to a tertiary referral center, so as to conduct a descriptive causal analysis and identify treatable risk factors for failure. Our hypothesis was confirmed in that the majority of failures were caused by a lack of treating underlying factors such as malalignment, meniscal deficiency, and ligament instability.

The most common reason for failure of cartilage restoration procedures was residual malalignment (56%). In cases of malalignment, the affected cartilage compartment is overloaded, with potentially profound changes in the force distribution at relatively low degrees of angulation. In previous native joint and total knee model analyses, it has been suggested that an increase of 4° to 6° of varus angulation leads to a 20% to 50% increase in medial tibiofemoral stresses.36,39 There exists strong evidence that malalignment plays a role in both the development and subsequent progression of osteoarthritis.6,33,35 In particular, Sharma et al,33 in their age-, sex-, and BMI-adjusted model, demonstrated that varus malalignment was associated with a 4-fold increase in the progression of Kellgren-Lawrence arthritis of ≥1 grade at 18-month follow-up, while valgus malalignment was associated with a near 5-fold increased incidence of arthritic progression.

In the study by Sharma et al,33 the severity of both varus and valgus deformities correlated with the risk of disease progression. As such, we believe that long-leg standing hip-to-ankle radiographs are of utmost importance in these patients. Without addressing the underlying increased contact stresses that may have caused the primary cartilage injury, any restorative procedures are at an increased risk to fail under continued increased stresses. While osteotomy alone in patients with chondral lesions and underlying malalignment may provide short-term symptomatic improvements, we recommend concurrent operative treatment of cartilage defects, as restoration of the articular surface is necessary for optimal load sharing to prevent asymmetric kinematics and resultant cartilage defects. In light of optimizing an even articular load distribution, we recommend restoration of the normal anatomic axis as opposed to overcorrection when performing osteotomy for focal defects. Accordingly, sports medicine surgeons who perform cartilage restoration in their practice need to be well equipped and experienced with performing periarticular osteotomy about the knee. We also recommend avoiding microfracture for lesions encountered at the time of arthroscopic surgery without knowledge of preoperative alignment, as it is possible that a significant number of microfracture failures are caused by addressing such findings without a sufficient evaluation of contributing background factors.

Another common reason for cartilage surgery failure was meniscal deficiency, which was observed in 11 of the 59 cases of revision surgery (19%). Meniscectomy and untreated meniscal tears have an extensive track record for leading to increased osteochondral degenerative changes over time when compared with uninvolved contralateral knees or population controls.3,7,12,27 In cadaveric studies, it has been demonstrated that after partial meniscectomy of the inner one-third of the meniscus, tibiofemoral contact areas decrease by 10%, while peak local contact stresses increase by 65%.4 Furthermore, in total meniscectomy, contact areas decrease by 75%, and peak local contact stresses increase 2.35-fold.4

Of additional significance is a definitive intraoperative examination of the meniscal roots, as tears in these difficult-to-image areas have demonstrated significant subsequent increases in articular contact stresses.2,18,19,21 Consideration should also be given for meniscal allograft transplantation for cases in which meniscal repair or conservative partial debridement is not possible. Although there is controversy regarding the long-term results of meniscal transplantation, biomechanical studies support a possible protective role in increasing the contact area and stability as well as decreasing peak contact stresses within the knee joint.1,16,26,29,31,34

The importance of concomitant instability in patellofemoral cartilage defects is considerable and provides a treatment challenge. In the landmark series by Brittberg et al,5 overall results for ACI were quite promising, with 16 of the 23 patients reporting good to excellent outcomes. However, positive outcomes were concentrated in the femoral condylar transplant group (14/16 good to excellent), while failures were concentrated in the patellar group (2/6 good to excellent). At the time of that study’s publication in 1994, patellar maltracking and instability had not been well recognized in the literature and thus were not addressed intraoperatively. In their discussion, the authors suggested that malalignment and subluxation may play a role in their modest results and that these may be better addressed by correction of the underlying abnormalities. In more contemporary series reporting on patellar ACI with concomitant biomechanical normalization procedures such as TTO with anteromedialization, trochleoplasty, and MPFL reconstruction, outcomes have been significantly improved. A recent multicenter study demonstrated greater than 80% good to excellent outcomes, and more than 90% of patients stated that they would undergo the procedure again.13

Special care should also be taken to evaluate for sagittal and coronal instability. There is an abundance of literature suggesting that for patients with laxity, coronal instability precedes and predisposes to osteoarthritic changes, with the degree of laxity positively associated with a degree of cartilage loss.32 In terms of sagittal instability, it has been demonstrated that patients with meniscal tears and concomitant ACL tears fare worse after meniscectomy than those who undergo isolated meniscectomy without ACL lesions.7 Similarly, MRI and biomechanical studies have suggested that posterior cruciate ligament deficiency causes both acute chondral damage and increased cartilage deformation and altered tibiofemoral loads, leading to chronic cartilage degeneration that is potentially preventable by addressing the underlying ligamentous source of instability.9,28,37 As such, patients with ligamentous laxity should be counseled on their increased risk for failure after cartilage procedures, while patients with surgically correctable factors such as ACL and/or posterior cruciate ligament deficiency should undergo treatment of both cartilage and associated ligamentous abnormalities to minimize the risk of subsequent failure.

Despite the correction of background factors and improvements in techniques and outcomes, cartilage surgery will not have uniformly excellent results. In the current study, graft failure was the reason for approximately one-fourth of revision cases. While storage and optimization efforts are underway to improve graft quality, and surgical techniques continue to evolve, the patient undergoing cartilage surgery continues to pose a complex clinical entity, which is often the result of multiple overlapping biomechanical and patient-specific factors. While surgical factors can be optimized, other variables such as age, BMI, and activity level will continue to affect the rates of successful cartilage surgery.

Accordingly, cartilage surgery candidates must be preoperatively counseled in light of established risk factors for failure, such as increased BMI and age, as nonoperative treatment or arthroplasty may provide a more durable approach in these populations. We recommend that every patient undergoing cartilage surgery undergo an extensive clinical history, physical examination including analyses of gait and alignment, full-length radiography, and scrutinization of all imaging to recognize contributing background factors. Surgical management of such patients should only be considered in the practice of the physician facile in osteotomy, meniscal repair, meniscal transplantation techniques, and patellofemoral procedures such as TTO, MPFL reconstruction, lateral retinacular lengthening, and trochleoplasty.25

This review of failed cartilage procedures has some limitations. Defining failure as revision surgery at a tertiary referral center underestimates the number of procedures with poor results, as patients may elect for nonoperative management or even total knee arthroplasty after suboptimal outcomes with primary cartilage surgery. However, including patients with poor initial indications for cartilage surgery, such as diffuse degenerative changes, was not felt to add instructive insight to the mode of failure of cartilage repair surgery. The results of this study were also subject to a degree of referral bias, as the revising surgeon had no control over the nature of patients with failed cartilage repair presenting for re-evaluation or previous surgery that they had undergone. In light of this bias, the relative predominance or absence of primary procedures needing revision, such as microfracture and ACI, should be interpreted with caution, as these factors are influenced by not only the failure rate but also the prevalence and referral pattern.

An additional limitation was that the original surgeons did not assess alignment and provided no long-leg radiographs to the revising surgeon. Therefore, it is unknown if alignment changed from normal to malalignment between the primary and revision procedures. Similarly, an assumption was made that the status of the meniscus at the time of revision was similar to that after primary surgery was performed. Finally, when reporting surface area, the maximum length and width of lesions are presented. It is important to note that lesions were often irregular in shape, and thus, these total surface area measurements likely tend to overestimate the lesion size.

Conclusion

Cartilage restoration procedures play an important and evolving role in managing knee abnormalities, which often exist with a spectrum of contributing background factors. In the current series, the most common failed cartilage procedure treated with revision surgery was microfracture, and the most commonly recognized reason for failure was untreated coronal malalignment. While biologic and graft failures do occur, the majority of failures were attributed to untreated background factors such as malalignment, meniscal deficiency, and instability. Thorough preoperative recognition and consideration of the treatment of these background factors are critically important in cartilage surgery. By following a stepwise approach that first addresses alignment, meniscal volume, and joint stability before, or concurrently with, the cartilage defect, patient care and functional outcomes are more likely to be optimized.

Footnotes

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: A.J.K. receives research support from Aesculap/B. Braun, the Arthritis Foundation, Ceterix, and Histogenics; is a paid consultant for Arthrex, Vericel, and DePuy Orthopaedics; receives royalties from Arthrex; has received honoraria from the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation; and has received hospitality payments from Arthrex and the Musculoskeletal Transplant Foundation. M.J.S. is a paid consultant for Arthrex, receives royalties from Arthrex, receives research support from Stryker, and has received hospitality payments from Arthrex. D.B.F.S. receives research support from Arthrex, Ivy Sports Medicine, and Smith & Nephew and is a paid consultant for Cartiheal, Smith & Nephew, and Vericel.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (application No. 15-000601).

References

- 1. Alhalki MM, Hull ML, Howell SM. Contact mechanics of the medial tibial plateau after implantation of a medial meniscal allograft: a human cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28(3):370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allaire R, Muriuki M, Gilbertson L, Harner CD. Biomechanical consequences of a tear of the posterior root of the medial meniscus: similar to total meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(9):1922–1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Allen PR, Denham RA, Swan AV. Late degenerative changes after meniscectomy: factors affecting the knee after operation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66(5):666–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baratz ME, Fu FH, Mengato R. Meniscal tears: the effect of meniscectomy and of repair on intraarticular contact areas and stress in the human knee. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14(4):270–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, Ohlsson C, Isaksson O, Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(14):889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brouwer GM, van Tol AW, Bergink AP, et al. Association between valgus and varus alignment and the development and progression of radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(4):1204–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burks RT, Metcalf MH, Metcalf RW. Fifteen-year follow-up of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(6):673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camp CL, Stuart MJ, Krych AJ. Current concepts of articular cartilage restoration techniques in the knee. Sports Health. 2014;6(3):265–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandrasekaran S, Scarvell JM, Buirski G, Woods KR, Smith PN. Magnetic resonance imaging study of alteration of tibiofemoral joint articulation after posterior cruciate ligament injury. Knee. 2012;19(1):60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherian JJ, Kapadia BH, Banerjee S, Jauregui JJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Mechanical, anatomical, and kinematic axis in TKA: concepts and practical applications. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2014;7(2):89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clar C, Cummins E, McIntyre L, et al. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of autologous chondrocyte implantation for cartilage defects in knee joints: systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9(47):iii-iv, ix-x, 1–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30B(4):664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gomoll AH, Gillogly SD, Cole BJ, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the patella: a multicenter experience. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1074–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heir S, Nerhus TK, Rotterud JH, et al. Focal cartilage defects in the knee impair quality of life as much as severe osteoarthritis: a comparison of Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score in 4 patient categories scheduled for knee surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hernigou P, Medevielle D, Debeyre J, Goutallier D. Proximal tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis with varus deformity: a ten to thirteen-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69(3):332–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hommen JP, Applegate GR, Del Pizzo W. Meniscus allograft transplantation: ten-year results of cryopreserved allografts. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(4):388–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Horton MT, Pulido PA, McCauley JC, Bugbee WD. Revision osteochondral allograft transplantations: do they work? Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(11):2507–2511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. LaPrade CM, Jansson KS, Dornan G, Smith SD, Wijdicks CA, LaPrade RF. Altered tibiofemoral contact mechanics due to lateral meniscus posterior horn root avulsions and radial tears can be restored with in situ pull-out suture repairs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(6):471–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. LaPrade RF, Matheny LM, Moulton SG, James EW, Dean CS. Posterior meniscal root repairs: outcomes of an anatomic transtibial pull-out technique. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(4):884–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Dwyer T, et al. The epidemiology of revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in Ontario, Canada. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(11):2666–2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marzo JM, Gurske-DePerio J. Effects of medial meniscus posterior horn avulsion and repair on tibiofemoral contact area and peak contact pressure with clinical implications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(1):124–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCormick F, Harris JD, Abrams GD, et al. Trends in the surgical treatment of articular cartilage lesions in the United States: an analysis of a large private-payer database over a period of 8 years. Arthroscopy. 2014;30(2):222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McNickle AG, Provencher MT, Cole BJ. Overview of existing cartilage repair technology. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2008;16(4):196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Minas T. Chondrocyte implantation in the repair of chondral lesions of the knee: economics and quality of life. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 1998;27(11):739–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ntagiopoulos PG, Dejour D. Current concepts on trochleoplasty procedures for the surgical treatment of trochlear dysplasia. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(10):2531–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Paletta GA, Jr, Manning T, Snell E, Parker R, Bergfeld J. The effect of allograft meniscal replacement on intraarticular contact area and pressures in the human knee: a biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25(5):692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Papalia R, Del Buono A, Osti L, Denaro V, Maffulli N. Meniscectomy as a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Br Med Bull. 2011;99:89–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ringler MD, Shotts EE, Collins MS, Howe BM. Intra-articular pathology associated with isolated posterior cruciate ligament injury on MRI. Skeletal Radiol. 2016;45(12):1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rongen JJ, Hannink G, van Tienen TG, van Luijk J, Hooijmans CR. The protective effect of meniscus allograft transplantation on articular cartilage: a systematic review of animal studies. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2015;23(8):1242–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Samitier G, Marcano AI, Alentorn-Geli E, Cugat R, Farmer KW, Moser MW. Failure of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2015;3(4):220–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sekiya JK, Giffin JR, Irrgang JJ, Fu FH, Harner CD. Clinical outcomes after combined meniscal allograft transplantation and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(6):896–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sharma L, Lou C, Felson DT, et al. Laxity in healthy and osteoarthritic knees. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(5):861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sharma L, Song J, Felson DT, Cahue S, Shamiyeh E, Dunlop DD. The role of knee alignment in disease progression and functional decline in knee osteoarthritis. JAMA. 2001;286(2):188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smith NA, Costa ML, Spalding T. Meniscal allograft transplantation: rationale for treatment. Bone Joint J. 2015;97B(5):590–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, Wluka AE, Berry P, Urquhart DM. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):459–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tetsworth K, Paley D. Malalignment and degenerative arthropathy. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):367–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Van de Velde SK, Bingham JT, Gill TJ, Li G. Analysis of tibiofemoral cartilage deformation in the posterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(1):167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wasserstein D, Khoshbin A, Dwyer T, et al. Risk factors for recurrent anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2099–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wong J, Steklov N, Patil S, et al. Predicting the effect of tray malalignment on risk for bone damage and implant subsidence after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Res. 2011;29(3):347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wright RW, Huston LJ, Spindler KP, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of the Multicenter ACL Revision Study (MARS) cohort. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(10):1979–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]