Abstract

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance endangers effective prevention and treatment of infections, and places significant burden on patients, families, communities and healthcare systems. Low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) are especially vulnerable to antibiotic resistance, owing to high infectious disease burden, and limited resources for treatment. High prevalence of antibiotic prescription and use due to lack of provider’s knowledge, prescriber’s habits and perceived patient needs further exacerbate the situation. Interventions implemented to address the inappropriate prescription and use of antibiotics in LMICs must address different determinants of antibiotic resistance through sustainable and scalable interventions. The aim of this protocol is to provide a comprehensive overview of the methods that will be used to identify and appraise evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behaviour change interventions implemented in LMICs to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics.

Methods and analysis

Two databases (Web of Science and PubMed) will be searched based on a strategy developed in consultation with an essential medicines and health systems researcher. Additional studies will be identified using the same search strategy in Google Scholar. To be included, a study must describe a behaviour change intervention and use an experimental design to estimate effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness in an LMIC. Following systematic screening of titles, abstracts and keywords, and full-text appraisal, data will be extracted using a customised extraction form. Studies will be categorised by type of behaviour change intervention and experimental design. A meta-analysis or narrative synthesis will be conducted as appropriate, along with an appraisal of quality of studies using the Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) checklist.

Ethics and dissemination

No individual patient data are used, so ethical approval is not required. The systematic review will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at a relevant international conference.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017075596

Keywords: antibiotic resistance, behaviour change, public health, systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

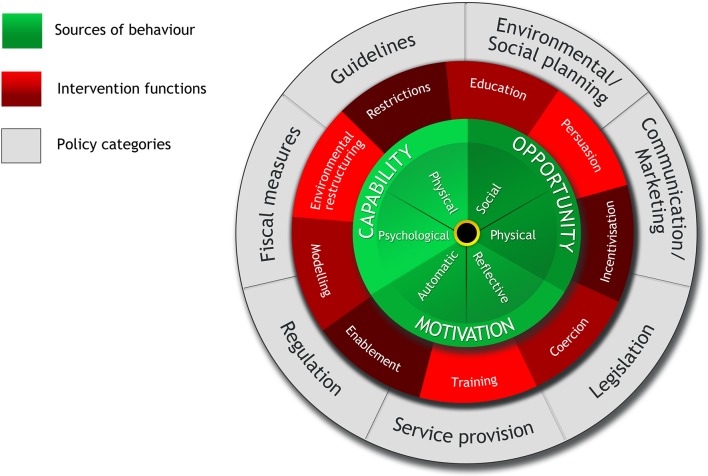

This study will focus on behaviour change interventions, using the Behaviour Change Wheel to systematically classify interventions.

Studies written in multiple languages (English, Spanish, French and Portuguese) will be considered.

The GRADE checklist will be used to assess quality and strength of the evidence.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness outcomes of the included data might be too heterogeneous to conduct a meta-analysis; if so, a narrative synthesis of evidence will be conducted.

Studies may not report process and/or wider contextual factors that could facilitate or act as a barrier to the success of an intervention.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is recognised as one of the greatest threats to human health.1 2 It endangers the effective prevention and treatment of a range of infections as it often results in prolonged illness, and consequently, patients remain infectious for a longer time.3 There is also an increased risk of spreading resistant micro-organisms to others.4 5 Owing to resistance to first-line drugs, alternative and more expensive and lengthy treatment procedures must be used, placing a strain on the healthcare system.6–8 This adds to the burden on individuals, their families and communities who bear higher direct and indirect costs of care.4 5 9 10 While ABR has predominantly been a clinical problem in hospital settings, there is increasing evidence that resistant organisms are prevalent at the primary-care level.11

A significant force driving the spread of ABR is the inappropriate use and prescription of antibiotics in primary care and hospital settings.7 12 Low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) are especially vulnerable, owing to a high burden of infectious diseases and limited resources to treat them.13–15 A complex range of determinants of the inappropriate use of antibiotics has been identified in LMIC settings including lack of provider knowledge7 14 16–18; prescriber’s habit7 17 18; limited availability of independent, non-pharmaceutical industry sources of information about the effects of medicines17; lack of continuing medical education and supervision17 19–21; pharmaceutical promotion17 21; short doctor–patient–dispenser interaction time1 17; peer pressure2 17 18 22 23; perceived and real patient demand17 18 24; lack of diagnostic support tools,1 17 economic incentives to prescribers and/or dispensers17 18 25; inappropriate medicine supply17 18 26; and how patients and community members use or consume prescribed medicines.18

Interventions to tackle these different determinants must be a key part of any strategy to address ABR.12 Recently published systematic reviews have identified a range of interventions that could improve antibiotic stewardship.6 27–29 These interventions include the use of printed educational materials6 27; audit and feedback6 27; interactive educational meetings6 27; didactic lectures, compliance with antibiotic guidelines28; reinforcement of existing guidelines or their development, if previously non-existent28; and physician reminders to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics6 27 as means for improving the use and prescription of antibiotics. Another set of interventions uses mass media communication campaigns to reach both the public and prescribers through nationwide campaigns or more targeted interventions.29 The majority of studies included in these reviews used data from interventions implemented in high-income settings. Only 26 of the 221 studies included in the review by Davey et al,27 4 of the 39 studies included in the review by Arnold and Straus6 and 1 of the 14 included studies in the review by Cross et al 29 were set in LMICs. The review by Charani et al 28 did not include any interventions set in LMICs.

The studies included in all four reviews appraised both single and multi-faceted interventions. Overall, multi-faceted interventions (more than one intervention component) were more effective in the improvement of antibiotic use and prescribing.1 6 17 22 29 All studies included in these reviews were set in the health facilities (ambulatory and inpatient), and did not include any interventions implemented in the community setting. Moreover, only two reviews included behaviour change interventions.28 29 None of these reviews provided any estimates of costs of delivery or cost-effectiveness of the implemented interventions. This leaves a considerable knowledge gap for LMICs where resistance to antibiotics is growing at an alarming rate.16 25

The aim of this protocol is to provide a comprehensive overview of the methods that will identify behaviour change interventions implemented in LMICs to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics, and appraise their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness through a systematic review of available evidence. The proposed review will summarise and critically appraise the evidence on behaviour change interventions implemented to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics in LMICs. Specifically, the objectives of the review are to:

Identify behaviour change interventions implemented in LMICs to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics in inpatient and outpatient settings.

Synthesise the available evidence to determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the implemented behaviour change interventions, using the framework outlined by the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW).30

Appraise the quality of the studies included in the review using criteria set in the GRADE checklist.31

Identify the intervention components that are most strongly associated with effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Identify knowledge gaps to guide future research in this area in the content of health promotion and health system interventions.

Methods

Population, interventions and outcomes

For the review, we will consider peer-reviewed and published studies that evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of behaviour change interventions to improve the prescription and use of antibiotics in LMICs. We follow Michie et al’s definition of behaviour change—‘a coordinated set of activities designed to change specified behaviour patterns’ (p1).30 We will consider interventions targeting healthcare workers (including doctors, nurses, pharmacists and support staff), patients and community, and we will review all primary and secondary outcomes relating to antibiotic prescription and use.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Based on Michie et al’s BCW, we will include those interventions that focus on education, training, modelling, enablement, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, restriction and environmental restructuring.30

The BCW is a layered framework (figure 1).30 At the centre of this framework is the capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B) model that recognises that behaviour is part of an interacting system involving multiple components that include ‘capability’, ‘opportunity’, ‘motivation’ and ‘behaviour’. This allows for the investigation of a situation by defining the problem, specifying the target behaviour and identifying changes needed. The next circle contains the intervention functions such as training, enablement, education that might be necessary to address the gaps identified by the COM-B model. The outermost circle of the BCW is built on categories of policy that can potentially support the implementation and delivery of the intervention functions that are appropriate for the setting (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Behaviour Change Wheel (reproduced from Michie et al 30).

We will include studies that evaluate interventions within the framework of a randomised controlled trial (RCT), interrupted time series (ITS), controlled before–after (CBA) or have a quasi-experimental design, as the experimental design allows rigorous testing and establishment of causal relationships, and the ruling out of alternative causes.32 We will include studies undertaken in countries classified as LMIC using the World Bank’s 2016 country classification.33 The complete list of countries can be found in online supplementary appendix 1. The review will comprise articles published between 1990 and 2017, reflecting the period over which debate around appropriate use of antibiotics gained significant momentum.34

bmjopen-2018-021517supp001.pdf (19.1KB, pdf)

Studies written in languages other than those that the authors are proficient in (English, Spanish, French and Portuguese) will be excluded. Finally, we will also exclude conference abstracts, trial protocols, previous systematic reviews and non-peer reviewed publications of programme or intervention evaluation.

Search strategy

The study team (NB, CC, MK and VW) will define the search terms to be used. These will be categorised into different domains, based on the research question (table 1). These domains are: population, interventions, outcomes and countries. The process will be iterative, as key search terms might change throughout the process. Two researchers from the review team (CC and NB) will independently conduct comprehensive searches for peer-reviewed articles using two online research databases: Web of Science and PubMed. They will use the same set of keywords to search for studies in Google Scholar and screen the first 100 hits for peer-reviewed articles that might have been missed in the previous database searches. They will hand-search the references of the final included studies to capture additional studies that fit the inclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Proposed keywords for systematic review search strategy

| Population — drugs | antibiotic*; antimicrobial*; “anti-bacterial agents”; antibacterial; anti-bacterial |

| Interventions | “behavioural intervention*”, “behavioral intervention*”, “behaviour intervention”, “behavior intervention”, “behaviour change”, “behavior change”, “behaviour modification”, “behavior modification”, “training”, “supervision”, “education”, “knowledge”, “feedback”, “audit”, “reminders”, “modelling”, “modeling”, “enablement”, “persuasion”, “incentivisation”, “incentivization’, “coercion”, “restriction”, “environmental restructuring”, “guidelines”, “stewardship”, “law enforcement”, “policy”, “governance” |

| Outcomes | “use”, “rational use”, “irrational use”, “inappropriate use”, “appropriate use”, “appropriate treatment”, “treatment”, “prescription”, “adequate prescription”, “prescri*”, “knowledge”, “prophylactic use”, “prophilaxys”, “effectiveness”, “cost effectiveness”, “cost-effectiveness”, “economic evaluation”, “costs”, “costing”, “cost effectiveness analysis”, “cost-effectiveness analysis”, “cost benefit analysis”, “cost-benefit analysis”, “cost utility analysis”, “cost-utility analysis”, “utilization”, “utilisation”, “drug use”, “medicine use”, “essential medicine*”, “drug information”, “drug therapy”, “consumption”, “prescribing practices”, “prescribing behaviour”, “prescribing behavior” |

| Countries | “low and middle income countr*”, “low income countr*”, “middle income countr*”, LMIC*, “developing countr*”, Afghanistan, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Korea, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mozambique, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zimbabwe, Armenia, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Bolivia, Cabo Verde, Cambodia, Cameroon, Republic of Congo, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Arab Republic of Egypt, Egypt, El Salvador, Ghana, Guatemala, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Kiribati, Kosovo, Republic of Kyrgyz, Kyrgyz, Lao PDR, Lao, Lesotho, Mauritania, Federated States of Micronesia, Micronesia, Moldova, Mongolia, Morocco, Myanmar, Burma, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Philippines, Samoa, Sao Tome and Principe, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Swaziland, Arab Republic of Syria, Syria, Tajikistan, Timor-Leste, Timor Leste, East Timor, Tonga, Tunisia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Vietnam, West Bank and Gaza, Republic of Yemen, Yemen, Zambia, Albania, Algeria, American Samoa, Angola, Argentina, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belize, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea, Ecuador, Fiji, Gabon, Georgia, Grenada, Guyana, Islamic Republic of Iran, Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Lebanon, Libya, Republic of Macedonia, Macedonia, Malaysia, Maldives, Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Mexico, Montenegro, Namibia, Palau, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Romania, Russian Federation, Russia, Serbia, South Africa, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Thailand, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Venezuela RB, Venezuela |

Terms within each row are separated by OR.

Terms across each row are separated by AND.

Limited to publications related to Humans.

Limited to publications from January 1990 to 2017.

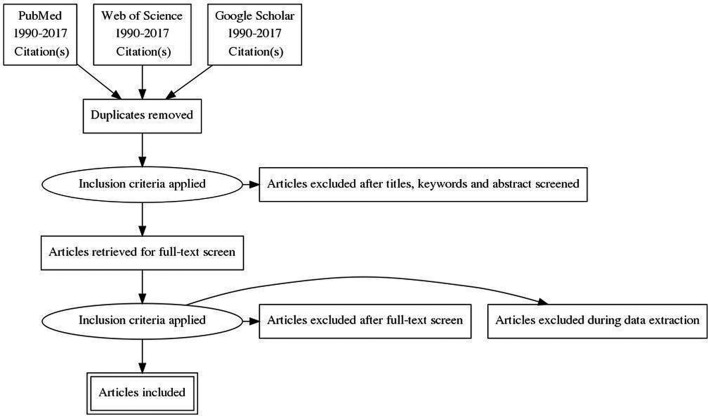

Data analysis and synthesis

The search results will be extracted into Mendeley V.1.17.11 and checked for duplicates which will be removed. CC and NB will independently screen all titles and abstracts retrieved from their literature searches. If there is uncertainty around whether certain studies should be included, the other team members (MK and VW) will independently appraise these studies to resolve the uncertainty. Following this screening phase, one researcher (CC) will review the full text of the papers to ensure that all inclusion criteria are met. Studies not meeting one or more of the inclusion criteria will be excluded. If there is uncertainty around the inclusion of studies at this stage, a second round of appraisal will be undertaken by MK. Any outstanding disputes will be resolved by VW. The selection process will be summarised in a flow chart that will also document the number of excluded studies and reasons for exclusion (figure 2). Studies published in Spanish, French or Portuguese will be translated by CC into English and made available for the team to discuss. CC will extract the data into a data extraction form in Excel to capture details about the authors, country setting, study design, description of intervention package, outcome indicators and results.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram.

Once the data have been extracted, we will categorise studies according to the different types of behaviour change interventions using the BCW. Interventions will be assessed as either single or multi-faceted, as well as by the level of effectiveness and/or cost-effectiveness, and generalisability of results. Given that the included studies might have different evaluation designs, we will analyse the results for RCT, ITS, CBA and quasi-experimental studies separately. We anticipate a high degree of heterogeneity among study outcomes as interventions will be tailored to specific behaviours, populations and country settings. If there is some degree of homogeneity in the outcomes assessed across all or a subset of included studies, we will conduct a meta-analysis of effect with subgroup analysis. Otherwise, a narrative synthesis strategy will be used.35 Careful consideration will also be given to publication bias across studies and selective reporting within studies.

Finally, we will conduct an appraisal of the quality of the included studies using the GRADE checklist31 which has been widely used by the WHO, Cochrane Collaboration, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (USA) and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK).36 This checklist explicitly evaluates the quality of the evidence and the strengths and weaknesses of the recommendations that follow.37

Study dates

This study is ongoing, and the anticipated completion date for data extraction is 31 May 2018.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or public are not involved in this study.

Ethics and dissemination

As no individual patient data are used in this study, ethical approval is not required. The systematic review’s findings will be disseminated in a peer-reviewed journal and presented at relevant international conferences.

Discussion

The extent of the adverse impacts of ABR is widely known and recognised as a global public health concern. Timely and appropriate interventions and programmes need to be implemented to alleviate its harmful impact on people, communities and health systems. This review will be one of the first to focus on interventions designed to improve the use of antibiotics in LMICs. The results will be of direct benefit to governments and donors who are seeking to respond to the threat of ABR by developing evidence-based national strategies and action plans that include priority interventions to control resistance to antibiotics and antimicrobials. This review will provide a comprehensive overview of available evidence on both the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions that will aid priority setting and investment decisions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed equally to the design of the study. NB and CC drafted the manuscript, with support from MK and VW. VW is the guarantor of the review.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Llor C, Bjerrum L. Antimicrobial resistance: risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2014;5:229–41. 10.1177/2042098614554919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sumpradit N, Chongtrakul P, Anuwong K, et al. Antibiotics Smart Use: a workable model for promoting the rational use of medicines in Thailand. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:905–13. 10.2471/BLT.12.105445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neu HC. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science 1992;257:1064–73. 10.1126/science.257.5073.1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mølbak K. Human health consequences of antimicrobial drug-resistant Salmonella and other foodborne pathogens. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:1613–20. 10.1086/497599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Holmes AH, Moore LS, Sundsfjord A, et al. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2016;387:176–87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arnold SR, Straus SE. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;20 10.1002/14651858.CD003539.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Franco BE, Altagracia Martínez M, Sánchez Rodríguez MA, et al. The determinants of the antibiotic resistance process. Infect Drug Resist 2009;2:1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Bhutta ZA, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part I: recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:481–93. 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70189-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paladino JA, Sunderlin JL, Price CS, et al. Economic consequences of antimicrobial resistance. Surg Infect 2002;3:259–67. 10.1089/109629602761624225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmberg SD, Solomon SL, Blake PA. Health and economic impacts of antimicrobial resistance. Rev Infect Dis 1987;9:1065–78. 10.1093/clinids/9.6.1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Disseases. Community-Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance: Consultation Notes, 2010.

- 12. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO | Antibiotic resistance. 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/antibiotic-resistance/en/#.WEXNQUSXazI.mendeley (accessed 5 Dec 2016).

- 13. Murni IK, Duke T, Kinney S, et al. Reducing hospital-acquired infections and improving the rational use of antibiotics in a developing country: an effectiveness study. Arch Dis Child 2015;100:454–9. 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Esmaily HM, Silver I, Shiva S, et al. Can rational prescribing be improved by an outcome-based educational approach? A randomized trial completed in Iran. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2010;30:11–18. 10.1002/chp.20051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Opondo C, Ayieko P, Ntoburi S, et al. Effect of a multi-faceted quality improvement intervention on inappropriate antibiotic use in children with non-bloody diarrhoea admitted to district hospitals in Kenya. BMC Pediatr 2011;11:109 10.1186/1471-2431-11-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ayukekbong JA, Ntemgwa M, Atabe AN. The threat of antimicrobial resistance in developing countries: causes and control strategies. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2017;6 10.1186/s13756-017-0208-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Holloway K. Promoting the rational use of antibiotics. Reg Heal Forum 2011;15:122–30 http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Regional_Health_Forum_RHF_Vol_15_No_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Radyowijati A, Haak H. Improving antibiotic use in low-income countries: an overview of evidence on determinants. Soc Sci Med 2003;57:733–44 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12821020 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00422-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Xiao Y, Zhang J, Zheng B, et al. Changes in Chinese policies to promote the rational use of antibiotics. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001556–4. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wahlström R, Kounnavong S, Sisounthone B, et al. Effectiveness of feedback for improving case management of malaria, diarrhoea and pneumonia--a randomized controlled trial at provincial hospitals in Lao PDR. Trop Med Int Health 2003;8:901–9. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Laing R, Hogerzeil H, Ross-Degnan D. Ten recommendations to improve use of medicines in developing countries. Health Policy Plan 2001;16:13–20. 10.1093/heapol/16.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Awad AI, Eltayeb IB, Baraka OZ. Changing antibiotics prescribing practices in health centers of Khartoum State, Sudan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:135–42. 10.1007/s00228-005-0089-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pérez-Cuevas R, Guiscafré H, Muñoz O, et al. Improving physician prescribing patterns to treat rhinopharyngitis. Intervention strategies in two health systems of Mexico. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:1185–94. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00398-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu C, Zhang X, Wang X, et al. Does public reporting influence antibiotic and injection prescribing to all patients? A cluster-randomized matched-pair trial in china. Medicine 2016;95:e3965 10.1097/MD.0000000000003965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yip W, Powell-Jackson T, Chen W, et al. Capitation combined with pay-for-performance improves antibiotic prescribing practices in rural China. Health Aff 2014;33:502–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aiken AM, Wanyoro AK, Mwangi J, et al. Changing use of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis in Thika Hospital, Kenya: a quality improvement intervention with an interrupted time series design. PLoS One 2013;8 10.1371/annotation/6506cc0b-2878-4cf8-b663-23a2f32a199a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Davey P, Marwick CA, Scott CL, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:CD003543 10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Charani E, Edwards R, Sevdalis N, et al. Behavior change strategies to influence antimicrobial prescribing in acute care: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:651–62. 10.1093/cid/cir445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cross EL, Tolfree R, Kipping R. Systematic review of public-targeted communication interventions to improve antibiotic use. J Antimicrob Chemother 2017;72:975–87. 10.1093/jac/dkw520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R, et al. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490–4. 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neuman WL. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th Edition. 2010. https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Neuman-Social-Research-Methods-Qualitative-and-Quantitative-Approaches-7th-Edition/PGM74573.html (accessed 14 Dec 2017).

- 33. World Bank. World Bank GNI per capita Operational Guidelines & Analytical Classifications. 2016.

- 34. McDonagh M, Peterson K, Wintrhtop K, et al. Interventions to Improve Appropriate Antibiotic Use fro Acute Respiratory Tract Infections. Comp Eff Rev 2014;2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Prod from ESRC Methods Program 2006;2006:211–9. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Meader N, King K, Llewellyn A, et al. A checklist designed to aid consistency and reproducibility of GRADE assessments: development and pilot validation. Syst Rev 2014;3:82 10.1186/2046-4053-3-82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021517supp001.pdf (19.1KB, pdf)