Abstract

The bacterial flagellum exemplifies a system where even small deviations from the highly regulated flagellar assembly process can abolish motility and cause negative physiological outcomes. Consequently, bacteria have evolved elegant and robust regulatory mechanisms to ensure that flagellar morphogenesis follows a defined path, with each component self-assembling to predetermined dimensions. The flagellar rod acts as a driveshaft to transmit torque from the cytoplasmic rotor to the external filament. The rod self-assembles to a defined length of ~25 nanometers. Here, we provide evidence that rod length is limited by the width of the periplasmic space between the inner and outer membranes. The length of Braun’s lipoprotein determines periplasmic width by tethering the outer membrane to the peptidoglycan layer.

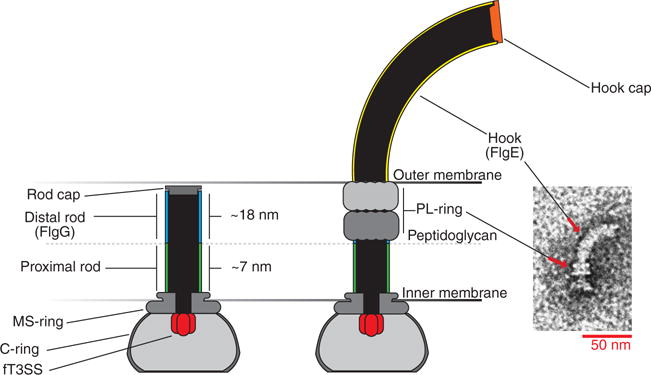

Length determination of linear filaments poses a particular problem, some of whose known examples are solved by using molecular rulers. The bacterial flagellum is one such linear filament composed of a series of axial structures that must be assembled to precise specifications to enable motility. The bacterial flagellum consists of a cytoplasmic, ion-powered rotary motor connected to a driveshaft (rod) that transmits torque to the external filament (propeller). The rod extends ~25 nm from the inner membrane through the peptidoglycan layer and periplasmic space to the outer membrane and terminates (Fig. 1). Termination of rod assembly positions the rod tip perpendicular to the outer membrane permitting an outer membrane–bound bushing complex, the periplasmic lipopolysaccharide ring (PL-ring), to assemble around the rod. The PL-ring forms an outer-membrane pore and results in the initiation of hook polymerization, which extends ~55 nm, followed by the filament. The hook acts as a universal joint connecting the rigid rod to the rigid filament, whose rotation propels the bacterium forward and allows the cell to alter its swimming trajectory (Fig. 1) (1–5). The length-control mechanism of the hook is well characterized and depends on the action of a secreted, molecular ruler, FliK. When the hook reaches a minimal length, the C terminus of FliK that is in the process of being secreted through the growing flagellar structure interacts with the FlhB gatekeeper protein of the flagellar type III secretion apparatus to switch secretion-substrate specificity from early, rod-hook secretion mode to late, filament secretion mode (6–10).

Fig. 1. The hook basal body of Salmonella enterica.

Construction of the flagellum begins with the assembly of the transmembrane membrane supramembrane ring (MS-ring), the flagellar type 3 secretion system (fT3SS), and the cytoplasmic ring (C-ring) rotor complex. The proximal rod polymerizes on top of the MS-ring followed by the FlgG distal rod to span the distance between the peptidoglycan layer and the outer membrane. FlgJ, the rod cap, allows the growing structure to pass through the peptidoglycan layer through localized hydrolysis of the peptidoglycan (28). Once the distal rod has reached the outer membrane, formation of the periplasmic ring–lipopolysaccharide ring (P-ring–L-ring) complex simultaneously forms a hole in the outer membrane and dislodges the rod cap. Rod cap removal allows the hook cap (FlgD) to form on the tip of the nascent structure and to promote assembly of the hook by FlgE subunits.

Although the flagellar hook serves as an excellent model for understanding length determination via the FliK molecular ruler, the length-control mechanism of another flagellar component, the rod, has remained enigmatic (11). The rod consists of two distinct substructures: the ~7-nm proximal and ~18-nm distal rod (12–14). The proximal rod is composed of four different proteins, and its mechanism of assembly remains unknown. In contrast, the distal rod is composed of ~50 copies of a single protein, FlgG. FlgG subunits must stack upon one another to reach the outer membrane (14). The self-stacking capability of FlgG poses a dilemma for the cell: Once initiated, what prevents continuously secreted FlgG subunits from polymerizing indefinitely?

A model for flagellar rod-length control was proposed on the basis of a set of mutations mapping to the flgG gene (flgG* mutations) that resulted in increased rod lengths. The flgG* rods grow beyond the wild-type (WT) length of ~25 nm to ~60 nm, which is determined by the FliK ruler (15). Because the flgG* mutations resulted in extended distal rod growth, a rod length–control mechanism was proposed that depended on intrinsic FlgG subunit stacking interactions during distal rod assembly. This model was based on earlier reports that the distal rod consisted of ~26 FlgG subunits, which would constitute two stacks of FlgG in the distal rod (16). Recent work has determined that the number of FlgG subunits in the distal rod is actually ~50 (14), which does not support an intrinsic distal rod length–control model based on subunit stacking interactions.

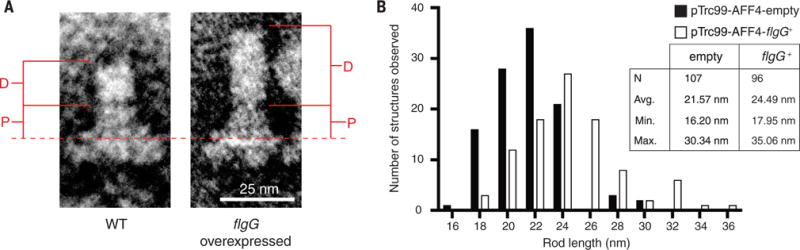

The FlgG-intrinsic model for rod-length control predicted that rod length would be unaffected by the cytoplasmic FlgG concentration. However, overexpression of the flgG gene yielded an increase in the average rod length (Fig. 2). This result and the finding that the distal rod is composed of ~50 FlgG subunits forced us to explore other possible mechanisms of flagellar rod-length control.

Fig. 2. Overexpression of flgG resulted in longer distal rods.

To test the FlgG intrinsic model for length control of the distal rod, flgG was overexpressed from a plasmid vector to supplement flgG expression from its native chromosomal locus in a strain lacking the genes required for termination of distal rod assembly (flgH) and subsequent hook assembly (flgD and flgE). (A) Flagellar basal bodies were purified from the flgG-overexpression background and compared with those from an empty-vector control strain by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). (B) Measurements were taken from the top of the MS-ring [dashed line in (A)] to the tip of the rod (P, proximal rod; D, distal rod). Overexpression of flgG was found to significantly increase the length of the rod (P < 0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t test, N = 2).

A clue to the actual rod-length control mechanism came from the isolation of suppressor mutations of the flgG* length-control mutants. Because rod growth in these mutants continues to ~60 nm, we speculated that the placement of the rod tip was no longer perpendicular to the outer membrane, compromising PL-ring assembly and resulting in filament growth in the periplasm and a nonmotile phenotype (11, 17). The nonmotile phenotype of flgG* mutants allowed us to perform a selection for suppressor mutations that relieved these mutants of the motility defect. One class of mutants arose in a gene not previously implicated in flagellar morphogenesis, lppA.

The lppA gene encodes Braun’s lipoprotein, which is the major outer-membrane lipoprotein of the cell in Gram-negative bacteria. Lpp is the most abundant protein in Escherichia coli, with 106 copies per cell. The LppA protein is secreted to the periplasm and processed to a final length of 58 amino acids that form homotrimers. N-terminal cysteine residues are acylated and anchor the LppA trimer in the outer membrane, whereas C-terminal lysine residues are covalently attached to the peptidoglycan layer (fig. S1) (18–20). Unlike the case in WT Salmonella, which displays a slight reduction in motility upon deletion of lppA (fig. S2), the flgG* mutants exhibited a 2- to 3-fold increase in swim diameter on motility agar when lppA was deleted (fig. S3).

We hypothesized that without LppA, the space between the peptidoglycan and outer membrane would be less constricted and would allow flgG* distal rods to be positioned perpendicular to the outer membrane as they grew longer than 25 nm, which would permit PL-ring pore formation. This predicted that the number of extracellular filaments assembled by flgG* mutants would increase upon deletion of lppA. Western blot analysis and fluorescence microscopy confirmed that extracellular flagellin secretion and assembly in flgG* mutants increased in the absence of LppA (fig. S4). Additionally, flgG* mutants still produced abnormally long rods regardless of whether LppA was present or not (fig. S5). These data suggested that the outer membrane acts as a barrier to distal rod growth and prevents continuous rod polymerization.

Unlike E. coli, Salmonella has two tandem lpp genes, lppA and lppB (fig. S1) (21, 22). The LppA protein is the equivalent of E. coli Lpp, whereas lppB is not expressed under standard laboratory conditions (23). LppA-length variants were constructed to test whether LppA determined the spacing between the peptidoglycan and outer membrane and whether this spacing determined distal rod length. LppA trimer formation is driven by hydrophobic interactions between seven heptad-repeat motifs within the mature 58–amino acid LppA monomers (20). An initial attempt to increase Lpp length by fusing LppA and LppB resulted in cells severely defective in cell shape and division (fig. S1). The LppA structure is based on heptad repeats of interacting monomers in the trimer. In an attempt to prevent cell-shape and division defects, length variants were designed that maintained interacting heptad repeats. The LppA length variants constructed included a 21–amino acid deletion and three longer variants containing insertions of 21, 42, and 63 residues (fig. S6).

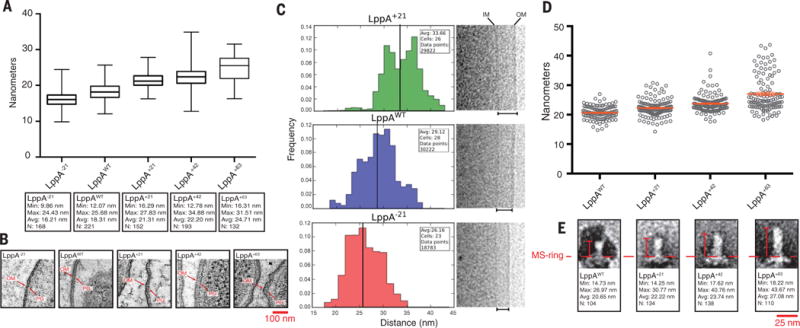

To determine whether changing LppA length resulted in a concomitant change in peptidoglycan-to–outer-membrane distance, LppA length–variant cells were embedded in resin and analyzed by electron microscopy. We observed changes in peptidoglycan-to–outer-membrane spacing that were proportional to LppA lengths (Fig. 3, A and B). Electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM), which preserved cells in a near-native frozen-hydrated state, corroborated these results. Imaging cells harboring lppA−21, lppA+21, and lppAWT variants by using cryo-EM demonstrated that the length of LppA was a principal determinant of the inner-membrane–to–outer-membrane distance (Fig. 3C and fig. S7).

Fig. 3. The inner-to outer-membrane distance and flagellar rod length varied with LppA lengths.

Resin-embedded LppA-length mutants, as well as WT control (TH22579 and TH22634 to TH22637) were thin-sectioned and observed by electron tomography. (A and B) The peptidoglycan-layer (PG)–to–outer-membrane (OM) distances for each strain were measured. As the length of LppA increased, we observed a corresponding increase in PG-to-OM distance [P < 0.0001, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)]. (C) To verify these results, cells from −21, +21, and WT LppA strains (TH22579, TH22634, and TH22635) were imaged via cryo-EM, and the distances between the inner membrane (IM) and OM were measured for each. The distances varied with LppA lengths (P < 0.0001, Student’s two-tailed t test). (D and E) Flagellar rods from lengthened LppA variants (TH22574 to TH22577) were purified, imaged via TEM and measured. The average length of the rod increased ~1.5 to 2 nm for every three heptad repeats (21 residues) added [P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA, N = ≥ 3, data in (D) are means ± SEM].

To test whether the length of the flagellar rod was dictated by periplasmic width, we measured rods isolated from the LppA-length mutants. We observed changes in the average length of the flagellar rod as the length of LppA changed (Fig. 3, D and E, and figs. S8 and S9). Taken together, the data obtained from resin-embedded electron microscopy, cryo-EM, and rod-length measurements were consistent with a model for distal rod–length control that required contact with the outer membrane.

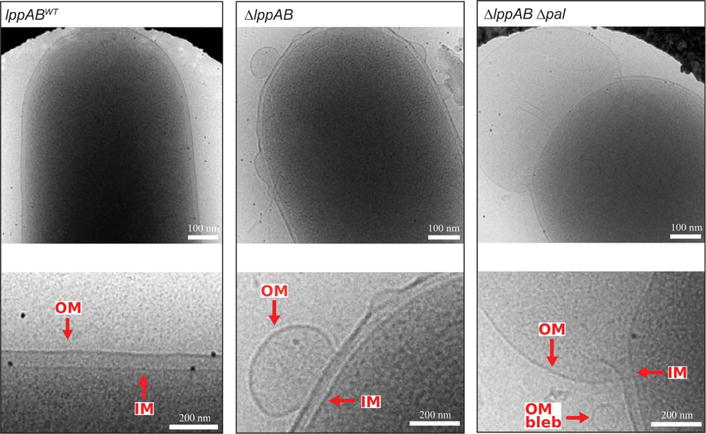

Electron cryo-EM was then used to address whether the osmotic pressure in the periplasm mirrors that of the cytoplasm or the external environment. Suppression of the flgG* motility defect by loss of LppA is consistent with the osmolalities in the cytoplasm and periplasm being equal, which is in agreement with previous studies (24, 25). In an attempt to further address this, we imaged one mutant having lppAB deleted and one with both lppAB and pal deleted. Pal is another abundant outer-membrane lipoprotein that noncovalently binds peptidoglycan (26, 27) and could tether the outer membrane to the peptidoglycan. We reasoned that if LppA functions as a tether under tension, as expected if the cytoplasmic and periplasmic osmolalities were equal, the absence of LppA would allow the outer membrane to pull away from the cell body as the osmolality of the periplasm equilibrates with that of the external environment.

Imaging the ΔlppAB mutant revealed that the outer membrane pulled away from the cell body in taut blebs. In the ΔlppAB Δpal double mutant, more extreme blebbing was observed (Fig. 4 and fig. S7). These results support previous reports that the osmolality of the periplasm mirrors that of the cytoplasm and that the function of LppA (and perhaps other peptidoglycan-binding lipoproteins) is to act as a tether rather than a support column under normal growth conditions.

Fig. 4. LppA functions as an outer-membrane tether.

Deletion of lppAB (strain TH22543) resulted in the formation of taut outer-membrane blebs that pulled away from the cell body. The severity of blebbing was increased in the ΔlppAB Δpal double mutant (strain TH22569).

Evolution places constraints and limitations on each component of an organism in order to maximize the fitness of the organism as a whole. In addition to housing the flagellar driveshaft, the periplasm contains a multitude of other cellular machinery. We were surprised to discover that addition of 21 residues to LppA increased the apparent swim rate of Salmonella to a small degree (~10%) (fig. S10). Also, altering the length of LppA caused slower growth and morphological abnormalities that became more pronounced the further the length deviated from the mature wild-type LppA length of 58 residues (fig. S10). These observations suggest that the selective forces that have influenced flagellar form and function have led to a compromise on the absolute optimization of swimming ability in favor of a motility organelle that is optimized to function in harmony with other components of the cell and under various conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. Silhavy for anti-Lpp antisera and D. Blair and N. Wingreen for helpful discussions. All strains, primers, and plasmids used in this study are available upon request. This work was funded by NIH grant GM056141 (K.T.H.), Marie Curie Career Integration Grant 630988 (M.B.) and UK Medical Research Council Ph.D. Doctoral Training Partnership award MR/K501281/1 (J.L.F.).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

www.sciencemag.org/content/356/6334/197/suppl/DC1 Materials and Methods

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Macnab RM. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:77–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chevance FFV, Hughes KT. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:455–465. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones CJ, Homma M, Macnab RM. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:3890–3900. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.7.3890-3900.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schoenhals GJ, Macnab RM. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4200–4207. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4200-4207.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berg HC, Anderson RA. Nature. 1973;245:380–382. doi: 10.1038/245380a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano T, Yamaguchi S, Oosawa K, Aizawa S. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5439–5449. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5439-5449.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erhardt M, Singer HM, Wee DH, Keener JP, Hughes KT. EMBO J. 2011;30:2948–2961. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muramoto K, Makishima S, Aizawa SI, Macnab RM. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:871–882. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uchida K, Aizawa S. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:1753–1758. doi: 10.1128/JB.00050-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi N, et al. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6469–6472. doi: 10.1128/JB.00509-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chevance FFV, et al. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2326–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.1571607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homma M, Kutsukake K, Hasebe M, Iino T, Macnab RM. J Mol Biol. 1990;211:465–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90365-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saijo-Hamano Y, Uchida N, Namba K, Oosawa K. J Mol Biol. 2004;339:423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujii T, et al. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14276. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirano T, Mizuno S, Aizawa S, Hughes KT. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:3938–3949. doi: 10.1128/JB.01811-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones CJ, Macnab RM, Okino H, Aizawa S. J Mol Biol. 1990;212:377–387. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen EJ, Hughes KT. J Bacteriol. 2014;196:2387–2395. doi: 10.1128/JB.01580-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;415:335–377. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(75)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kovacs-Simon A, Titball RW, Michell SL. Infect Immun. 2011;79:548–561. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shu W, Liu J, Ji H, Lu M. J Mol Biol. 2000;299:1101–1112. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sha J, et al. Infect Immun. 2004;72:3987–4003. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.3987-4003.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fadl AA, et al. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1081–1096. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1081-1096.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kröger C, et al. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:683–695. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cayley DS, Guttman HJ, Record MT., Jr Biophys J. 2000;78:1748–1764. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76726-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sochacki KA, Shkel IA, Record MT, Weisshaar JC. Biophys J. 2011;100:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cascales E, Bernadac A, Gavioli M, Lazzaroni JC, Lloubes R. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:754–759. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.3.754-759.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parsons LM, Lin F, Orban J. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2122–2128. doi: 10.1021/bi052227i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nambu T, Minamino T, Macnab RM, Kutsukake K. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1555–1561. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1555-1561.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.