Abstract

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) during pregnancy are growing health concerns because these conditions are associated with adverse outcomes for newborn infants. SDB/OSA during pregnancy exposes the mother and the fetus to intermittent hypoxia. Direct exposure of adults and neonates to IH causes neuroinflammation and neuronal apoptosis, and exposure to IH during gestation (GIH) causes long-term deficits in offspring respiratory function. However, the role of neuroinflammation in CNS respiratory control centers of GIH offspring has not been investigated. Thus, the goal of this hybrid review/research article is to comprehensively review the available literature both in humans and experimental rodent models of SDB in order to highlight key gaps in knowledge. To begin to address some of these gaps, we also include data demonstrating the consequences of GIH on respiratory rhythm generation and neuroinflammation in CNS respiratory control regions. Pregnant rats were exposed to daily intermittent hypoxia during gestation (G10-G21). Neuroinflammation in brainstem and cervical spinal cord was evaluated in P0-P3 pups that were injected with saline or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 0.1 mg/kg, 3 h). In CNS respiratory control centers, we found that GIH attenuated the normal CNS immune response to LPS challenge in a gene-, sex-, and CNS region-specific manner. GIH also altered normal respiratory motor responses to LPS in newborn offspring brainstem-spinal cord preparations. These data underscore the need for further study of the long-term consequences of maternal SDB on the relationship between inflammation and the respiratory control system, in both neonatal and adult offspring.

1. Introduction

The neonatal respiratory control system needs to be functional and responsive to chemosensory input while adapting to rapid ongoing developmental changes in respiratory mechanics (Greer, 2012; Greer et al., 2006). Unfortunately, newborn humans are often exposed to pathological challenges, such as gestational intermittent hypoxia (GIH) due to maternal OSA, and postnatal inflammation due to bacterial infection, which compromise respiratory function and ongoing neural development. SDB and OSA during pregnancy are a growing clinical concern (Fung et al., 2012; Louis et al., 2014; Mindell et al., 2015; Pengo et al., 2014) because they are associated with adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes (Bourjeily et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2014; Pamidi et al., 2014). Likewise, infection and inflammation in newborn humans leads to life-threatening inhibition of breathing (Black et al., 2010; Chan et al., 2015) and causes neurodevelopmental disabilities (Dammann et al., 2002; Ferreira et al., 2014; Patro et al., 2015; Stoll et al., 2002a; Zanghi and Jevtovic-Todorovic, 2017). Inflammation in newborns can decrease breathing frequency, induce bouts of apneas and hypoxemia, and impair endogenous autoresuscitative responses (Herlenius, 2011). Given that SDB/OSA during pregnancy is increasingly prevalent with the ongoing obesity epidemic (see below), and perinatal infection is common, we propose an interaction between these two phenomena such that infants exposed to GIH are particularly vulnerable to inflammation. Specifically, we suggest that GIH may increase susceptibility of the newborn CNS to inflammatory challenge which will impair the respiratory control system.

Our goal in this review is to briefly summarize the literature regarding SDB and OSA during human pregnancy, and infection-induced inflammation in newborns. Our focus will be on how these conditions adversely affect pregnancy outcomes and the health of newborn infants. The limited literature on relevant experimental animal models will also be reviewed, particularly with respect to respiratory motor control. Our working hypothesis is that these early life experiences (GIH, inflammation) alter respiratory motor control in early development through to adulthood, thereby predisposing offspring to suffer from SDB and OSA later in life. Accordingly, we present our preliminary data regarding GIH effects on brainstem and cervical spinal cord inflammatory gene expression in vivo, and respiratory rhythm generation in vitro.

1.1. Prevalence of SDB and OSA during pregnancy

Sleep-disordered breathing covers a spectrum of disorders characterized by upper airway resistance during sleep, ranging in severity from snoring to OSA, which is characterized by apneas (>90% reduction in airflow for ≥ 10 s) and hypopneas (30% or more reduction in airflow for ≥ 10 s) that cause oxyhemoglobin desaturation and arousals (Amfilochiou et al., 2009; Tsara et al., 2009). The earliest reports of SDB during pregnancy were case studies (Conti et al., 1988; Joel-Cohen and Schoenfeld, 1978; Kowall et al., 1989), and a potential causal link between SDB and adverse perinatal outcomes was proposed (Schoenfeld et al., 1989). During the following 20 years, several studies sought to determine the prevalence of SDB during pregnancy using questionnaires regarding sleep (e.g., sleep duration, snoring, daytime sleepiness) with relatively small sample sizes. But importantly, these results provided the first evidence that SDB during pregnancy is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes (gestational diabetes mellitus, hypertension, preeclampsia, unplanned Caesarian delivery) and adverse perinatal outcomes (preterm delivery, low birth weight, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and intrauterine growth restriction) (Ding et al., 1997; Pamidi et al., 2014; Venkata and Venkateshiah, 2009). Since the predictive power of questionnaires and overnight portable sleep monitoring devices to detect OSA is limited (Lockhart et al., 2015), there is an ongoing effort to clinically document SDB in pregnant women using polysomnography or at-home ambulatory sleep-monitoring devices while prospectively following their pregnancy, birth outcome, and infant health.

A recent prospective polysomnography study (n = 1509 subjects) estimated OSA prevalence to be 4.9%, and identified obesity and hypertensive disorders as risk factors for SDB (Antony et al., 2014). With respect to obesity, an early case-controlled study showed that obese pregnant women had increased SDB parameters that further increased over pregnancy (Maasilta et al., 2001). In a larger, more recent prospective study to screen for OSA among obese pregnant women (n = 175), OSA prevalence was estimated at 15.4% and was associated with preeclampsia, Caesarian delivery, and neonatal intensive care unit admissions (Louis et al., 2012). The increased rate of OSA during pregnancy from 1998–2009 represents an annual increase of 24%, and exactly parallels the increased number of obese pregnant women (Louis et al., 2014). The increased incidence of OSA during pregnancy is suggested to be due to the increased prevalence of obesity in pregnant women (Louis et al., 2012; Pien et al., 2014). A 5–15% prevalence in otherwise healthy, pregnant women nonetheless represents a large patient population given that there are ~4 million births/year in the United States. Furthermore, the rise in obesity among fertile women suggests that the prevalence will continue to increase, increasing the number of patients who will be at risk for hypertensive disorders that further exacerbate their condition. Also, pregnant women with hypertensive disorders (chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia) are particularly at risk for OSA, as 41% of these women had OSA compared to only 16% of normotensive pregnant women (O’Brien et al., 2014). In agreement with this study, sleep monitoring testing revealed that OSA-positive pregnant patients tended to have had greater BMI’s and higher rates of hypertension (chronic and gestational), pre-gestational diabetes mellitus, asthma, and preeclampsia (Lockhart et al., 2015). Thus, OSA prevalence is estimated to be ~20% in a prospective observational study in pregnant women with other risk factors (Facco et al., 2014), much higher than in the population of healthy pregnant women.

1.2. Causes of SDB/OSA during pregnancy

Pregnancy causes widespread changes in respiratory function, sex hormone levels, and upper airway patency that paradoxically promotes and protects against SDB/OSA. The increasing size of the fetus elevates the diaphragm and significantly reduces maternal functional reserve capacity, expiratory reserve volume, and residual volume (Edwards et al., 2002), which decrease oxygen reserves in the lungs and compromise the ability to withstand apneas. The decrease in expiratory reserve volume may cause early airway closure during tidal ventilation (Holdcroft et al., 1977) and reduce oxygenation of the blood (Awe et al., 1979). Maternal nasal passage patency is also reduced during pregnancy due to chronic hyperemic congestion and rhinitis (Bende and Gredmark, 1999). Indeed, there is an associated increase in the Mallampati score (visual measure of ease of intubation) with pregnancy (Pilkington et al., 1995), coinciding with smaller upper airways in pregnant women at the oropharyngeal junction (Izci et al., 2006). During pregnancy, high progesterone levels increase ventilatory drive, which is thought to be protective (Lyons and Antonio, 1959). However, high progesterone also induces a respiratory alkalosis (pH = 7.44) that may promote instability in respiratory control, especially during sleep. For example, in non-pregnant subjects, hypocapnia and respiratory alkalosis induce central apneas during non-REM sleep, especially when transitioning from wakefulness to sleep (Skatrud and Dempsey, 1983). These wide-ranging physiological changes in respiratory function due to pregnancy may predispose the mother to experience nocturnal bouts of intermittent hypoxia.

1.3. Perinatal consequences and outcomes of maternal SBD/OSA

Although we are now becoming aware of the detrimental effects of SDB/OSA during pregnancy on the mother, the consequences of maternal SDB/OSA on the developing fetus are only beginning to be identified. Several studies link SDB/OSA during pregnancy with adverse perinatal outcomes (Chen et al., 2012a; Ding et al., 2014; Louis et al., 2012; Louis et al., 2014), but there is variability in the findings. A recent meta-analysis of the literature showed that moderate-to-severe SDB during pregnancy is associated with poor fetal outcomes, such as preterm delivery, low birth weight, neonatal intensive care unit admission, intrauterine growth restriction, and a low Apgar score (Ding et al., 2014). Likewise, women with documented sleep apnea prior to becoming pregnant are more likely to have preterm deliveries, Caesarian section, small-for-gestational age infants, preterm deliveries, low Apgar scores at delivery, and babies that are admitted more frequently to neonatal intensive care/special care units (Bin et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2012a). Similarly, mothers diagnosed with SDB during pregnancy (via in-home polysomnography) had increased odds of delivering an infant small for gestational age (Pamidi et al., 2014). In contrast, a prospective study that recruited a high-risk cohort of pregnant women (n = 128, BMI >30 kg/m2, history of chronic hypertension, pre-gestational diabetes, prior preeclampsia, or twin gestation) with documented sleep apnea showed no correlation with preterm delivery or extremely low birthweights (Facco et al., 2014). However, it is important to note that although there were no acute adverse effects on the newborns, some adverse effects may not be revealed until later in development. For example, in a study of 74 pregnant women with SDB, social development was impaired in their infants at one year of age (Tauman et al., 2015). Thus, infants and children of mothers with SDB/OSA should be carefully observed and tested to reveal potential long-lasting pathophysiological conditions.

It is hypothesized that cyclical episodes of maternal hypoxemia/reoxygenation due to SDB reduces placental oxygen delivery to fetus, thereby restricting fetal growth. Pregnant women with SDB had a mean apnea-hypopnea index of 63 ± 15 events/h, which exposes the fetus to a significant number of hypoxia/reoxygenation events (Edwards et al., 2005). This idea is also consistent with the findings that maternal snoring is associated with intrauterine growth restriction and lower APGAR scores at birth (Franklin et al., 2000). Maternal snoring during pregnancy is also associated with enhanced fetal erythropoiesis based on umbilical cord blood analysis (Tauman et al., 2011), suggesting that the fetus becomes hypoxic with maternal SDB. Similarly, a pregnant woman with OSA experienced nocturnal oxygen desaturations that were accompanied by prolonged fetal heart rate decelerations (Fung et al., 2013). Taken together, these data suggest that the fetus may experience some degree of in utero intermittent hypoxia with maternal SDB/OSA.

An alternative hypothesis is that intermittent hypoxia due to SDB during pregnancy causes stress in the mother and alters the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, such that plasma levels of stress hormones increase in the mother, which then reprograms the fetal CNS. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies examining ACTH or corticosterone plasma levels in pregnant women with documented SDB/OSA. In rodents, gestational stress induces long-lasting epigenome alterations in offspring (Cao-Lei et al., 2017), including long-lasting changes in the morphology and biological activity of microglia (Slusarczyk et al., 2015). Also, gestational stress increases spontaneous apneas and blunts the hypoxic ventilatory responses in young postnatal rats (Fournier et al., 2013). Taken together, rodent studies suggest that maternal stress and its deleterious fetal consequences may contribute to negative perinatal respiratory outcomes, but this has not yet been evaluated in pregnant women with SDB.

1.4. Perinatal inflammation

While a causal relationship between SDB/OSA during pregnancy and perinatal outcomes is still being tested, it is also important to consider another common pathophysiological challenge - infection and inflammation. Infection is particularly common in premature infants with up to 65% having at least one infection during hospitalization (Stoll et al., 2002b; Stoll et al., 2004). Neonatal infections are a significant cause of death in the first week of life (Chan et al., 2015) and account for approximately 1/3 of all neonatal deaths (Black et al., 2010). Bacterial infections represent the major cause of neonatal infections worldwide (Osrin et al., 2004; Skogstrand et al., 2008). Neonates surviving infection have increased vulnerability to both short- and long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities (Dammann et al., 2002; Ferreira et al., 2014; Patro et al., 2015; Stoll et al., 2002b; Zanghi and Jevtovic-Todorovic, 2017). Neonatal inflammation can arise from different stimuli including exposure to pathogens (e.g., group B streptococcus, respiratory syncytial virus), as well as diseases such as chorioamnionitis, sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia, many of which result in Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation. While TLR4 is directly activated by Gram negative bacterial endotoxin (lipopolysaccharide; LPS), fetal TLR4 signaling is also upregulated by maternal obesity in humans (Yang et al., 2016) and animal models (Pimentel et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2010). Thus, the use of TLR4 agonists, such as LPS, to create animal models in which to study early life neuroinflammation is not only simple, but it is well-studied and clinically relevant.

1.5. Critical periods of neurodevelopment

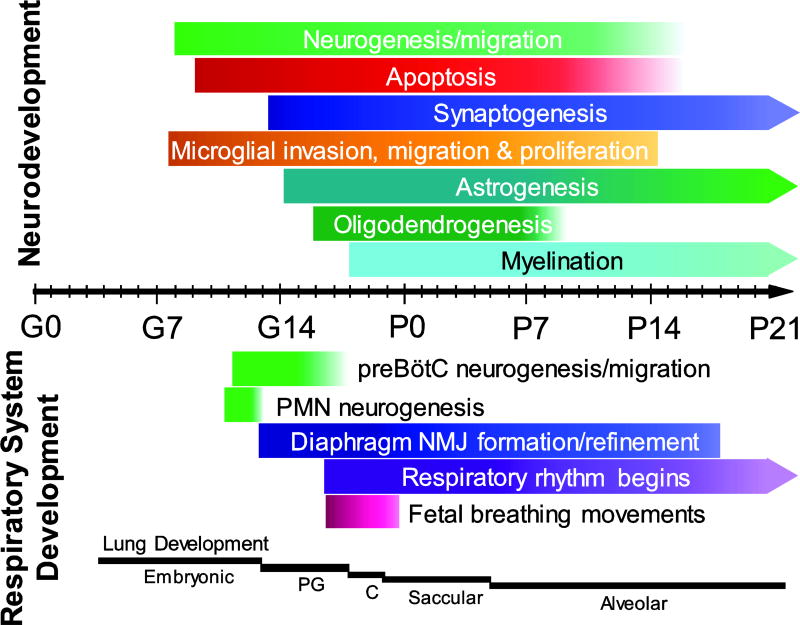

The potential for in utero intermittent hypoxia or perinatal inflammation to impact neural networks is high given the critical periods involved in fetal brain development, many of which extend into postnatal life ((Patro et al., 2015; Zanghi and Jevtovic-Todorovic, 2017); Fig. 1). In rodents, neurogenesis and angiogenesis peak around the time of birth and continue until ~P20, while oligodendrogenesis and astrogenesis peak after birth between P0-P5 (Reemst et al., 2016). Astrogenesis and synaptogenesis begin at approximately the same time, in the latter third of gestation (Ge et al., 2002; Kanjhan et al., 2016). Microglia, on the other hand, are born and invade the CNS early in embryogenesis, but undergo significant postnatal change both in terms of cell number, morphology and function (Crain et al., 2009; Crain and Watters, 2015; Mosser et al., 2017; Nikodemova et al., 2015). Microglia play key roles in the development and maturation of the CNS. Microglia release cytokines and trophic factors, perform synaptic pruning and maturation activities, assist in neuronal and glial migration, and influence cellular differentiation (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2012; Mosser et al., 2017). In many brain regions, spatiotemporal increases in cytokines (likely released from microglia) are thought to be important for proper development of neural circuits (Bilbo and Schwarz, 2012; Mosser et al., 2017). However, astrocytes and even neurons themselves can also contribute to the brain cytokine milieu (Ramesh et al., 2013). Regardless, perturbations in the balance of local CNS cytokines, or in the activation status of microglia specifically, may not only have lasting aberrant effects on developing neural circuits, but also on the expression profiles of key molecules involved in normal signal transduction and function of nearby developing cells (Reemst et al., 2016). Microglia or astrocyte dysfunction is linked to numerous neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (Squarzoni et al., 2014; Zhan et al., 2014), schizophrenia (Ma et al., 2013; Paolicelli et al., 2011), Fragile-X syndrome (Higashimori et al., 2013; Jacobs et al., 2010), depression (Nishiyama et al., 2002), and obsessive compulsive disorder (Zhan et al., 2014).

Fig. 1. CNS and respiratory system development during gestation and postnatal period in rats.

The timeline shows development from conception (E0) to 21 days of postnatal age (P21). “Neurodevelopment” (upper) depicts neuron, astrocyte, and microglial development and function (e.g., synaptogenesis, myelination). “Respiratory system development” (lower), depicts the development of respiratory-related neurons (preBötzinger Complex [preBötC], phrenic motoneurons) and the diaphragm, along with the onset of processes such as respiratory rhythm generation and fetal breathing movements. The bottom indicates the different stages of lung development from early formation in the fetus to alveolar structure in the lungs of a newborn rat. Abbreviations: PMN - phrenic motor neuron, PG - pseudoglandular, C - cancalicular, E - embryonic day, P - postnatal day.

However, a key question is whether there is evidence for a link between maternal SDB/OSA, newborn neuroinflammation and respiratory consequences. While such studies have not yet been done in humans, compelling evidence suggest they should. In a report of pregnant women with OSA, 46% of their offspring required admission to the NICU, even though the rate of cesarean delivery was similar to non-OSA pregnant women. Further, the incidence of NICU admissions represented over a 2.5 fold increase compared to mothers without OSA (Louis et al., 2012). Interestingly, over half of the babies admitted to the NICU from mothers with OSA were admitted for respiratory morbidities (Louis et al., 2012), suggesting that there may be negative consequences of maternal OSA on the development of the newborn respiratory system. To our knowledge, there are no data available where markers of inflammation in the offspring of mothers with OSA have been studied in humans or rodent models. Accordingly, we performed experiments using a rat model of GIH to investigate the relationship between intermittent hypoxia and neonatal inflammation in CNS regions controlling breathing (data discussed in sections 2 and 3).

1.6. Animal models of GIH

There are a few studies examining the effects of GIH on cardiorespiratory motor control and growth, but none evaluated neuroinflammation in the neonatal offspring. The first study of respiratory function in rodent GIH offspring demonstrated long-lasting increases in ventilation persisting into adulthood (Gozal et al., 2003). Interestingly, while the magnitude of the peak hypoxic responses were the same in offspring from GIH- and normoxic-exposed dams, the relative peak responses in GIH-offspring were lower due to an increase in normoxic ventilation. Likewise, the hypoxic ventilatory decline was increased in GIH-exposed P5 offspring. These data suggest that P5 may be a particularly vulnerable time during respiratory development. Important with respect to the long-lasting consequences in the offspring, the increased normoxic ventilation caused by GIH was still evident in 4 month-old rats, suggesting that the adult respiratory control system is unable to compensate for the negative consequences of GIH. These observations prompt questions about the capacity of the respiratory control system in neonatal and adult offspring of GIH-exposed dams to exhibit neuroplasticity, a form of learning that allows rapid adaptation of the neural control system to physiological and pathological challenges (Mitchell and Johnson, 2003).

Other long-lasting consequences of GIH in animals are likely to be similar to the risk factors and adverse perinatal outcomes of OSA in pregnant women. First, GIH exposure appears to alter metabolic regulation in the offspring and predisposes them to have metabolic disorders later in life. For example, GIH during the entire pregnancy in the rat caused asymmetric growth restriction on P1 offspring, with decreased body weights but higher brain:liver weight ratios (Iqbal and Ciriello, 2013). However, by adulthood, the body weights of the growth restricted offspring had rebounded in the other direction, showing significantly increased body weights and liver:body weight ratios. The increase in body weight corresponded to an increase in body fat deposition in adult GIH offspring, and the adult rats were also hyperglycemic with elevated insulin plasma levels (Iqbal and Ciriello, 2013). GIH exposure late in gestation (G13-G18) produced adult mice with increases in body fat, adiposity index, and insulin levels (Khalyfa et al., 2017). Interestingly, triglyceride and cholesterol levels were increased in male, but not female offspring. Adult male offspring had higher levels of pro-inflammatory macrophages in visceral white adipose tissue, which displayed changes in differentially methylated gene regions. These observations suggest that epigenetic alterations in DNA methylation may contribute to metabolic dysfunction in offspring of dams exposed to GIH (Khalyfa et al., 2017). Although no studies to our knowledge have evaluated the metabolic states of human offspring of mothers with OSA, based on the increasing prevalence of obesity and metabolic disease in western countries in recent decades, it is tempting to speculate that there may be a direct relationship between metabolic dysfunction and in utero intermittent hypoxia exposure. Second, cardiovascular control may also be deleteriously altered in rodents. Using a different model of GIH exposure late in gestation (G19-G20), adult rat offspring had increased blood pressure and sympathetic drive (Svitok et al., 2016), suggesting the autonomic nervous system can also be affected by GIH. Thus, GIH causes altered metabolic and cardiovascular regulation in adult rodent offspring, both of which are significant risk factors for other diseases.

1.7. Vulnerability of the developing respiratory control system

Despite our increasing understanding of the effects of perinatal inflammation on other physiological systems, only a few studies have investigated the effects of perinatal inflammation on respiratory control. Important components of the respiratory system begin developing in utero, such as rhythm generating cells in the preBötzinger Complex of the medulla ((Borday et al., 2006; Pagliardini et al., 2003), phrenic motoneurons (Mantilla and Sieck, 2008), and the diaphragm muscle (Mantilla and Sieck, 2008; Mantilla et al., 2008; Prakash et al., 2000). However, the respiratory system also undergoes significant postnatal maturation. The respiratory system must transition from fetal breathing movements in utero (facilitating lung maturation) to functional gas exchange after birth, an abrupt but important developmental shift (Greer et al., 2006). A hallmark of neonatal breathing, however, is instability with significant variations in frequency, amplitude, chemosensitivity, and paradoxical breathing (aberrant movement of rib cage and abdomen during inspiration) (Greer, 2012).

The respiratory control system is altered by early life events. For example, nicotine exposure in utero has lasting effects on lung development, apneas, breathing pattern, and autoresuscitation postnatally (Fregosi and Pilarski, 2008; Huang et al., 2010). Further, maternal separation early after birth elicits a stress response (and likely acute inflammation) in neonates, effects that are sex-specific and involve lasting consequences on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis which alter baseline breathing and chemosensitivity in the offspring (Genest et al., 2007a; Genest et al., 2004, 2007b). Adult females which experienced maternal separation as neonates have higher minute ventilation due to increased tidal volume, and adult males have increased hypoxic ventilatory responses (Genest et al., 2004). However, whether maternal intermittent hypoxia exposure has a similar ability to increase plasma levels of corticosterone in neonates is less clear. Neonates from dams exposed to gestational hypoxia (9% O2 for 6 h/day from G15 to 21, or 12% O2 for 24 h/day from G19 to 21) show decreased plasma corticosterone levels (Hermans et al., 1994; Raff et al., 2000), suggesting that while the HPA axis may be disrupted in these offspring, stress hormone levels do not increase. GIH (10% O2 90s intervals for 24 h/day from G5 to 21) causes long-lasting increases in baseline ventilation, increases sensitivity to opiate-induced respiratory depression, and blunts the hypoxic response (Gozal et al., 2003), but whether these respiratory outcomes are associated with elevated stress hormone levels in the neonates is not known. While none of above studies in which fetal stress hormone levels were measured mirror our particular GIH protocol, direct exposure of neonates to intermittent hypoxia (6 cycles of 3% O2 90s interval) does increase plasma corticosterone levels (Chintamaneni et al., 2013). Thus, the extent to which different maternal or fetal intermittent hypoxia protocols cause stress is not established, and the effects of stress or intermittent hypoxia on the developing respiratory control system are not well understood.

There are no studies examining the effects of GIH on CNS inflammatory status, or the response to postnatal inflammatory challenge in GIH-treated animals. However, in non-conditioned rodents, administration of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β decreases respiratory motor burst frequency (Hofstetter et al., 2007; Olsson et al., 2003) an effect that is linked to increased apneas (Greer, 2012). Since increased IL-1β and COX-2 gene expression are proposed to cause apnea in newborn infants (Herlenius, 2011), GIH may disrupt respiratory rhythm generation in neonatal rats, causing decreased breathing frequency and irregular rhythm via increased CNS cytokine and prostaglandin production. Although there are several studies examining the effects of postnatal/adult inflammation on respiratory motor control in rodents (e.g., (Agosto-Marlin et al., 2017; Gresham et al., 2011; Hofstetter and Herlenius, 2005; Hofstetter et al., 2007; Huxtable et al., 2011; Koch et al., 2015; Master et al., 2016; Olsson et al., 2003; Ribeiro et al., 2017; Rourke et al., 2016; Siljehav et al., 2012; Vinit et al., 2011), there are no studies testing the effects of inflammatory challenge in GIH offspring. Accordingly, in neonates from GIH-exposed dams, we evaluated: (1) pro-inflammatory gene expression (IL-1β, TNFα, COX-2) in brainstem and spinal cord (2) the neuroinflammatory response to subsequent immune challenge, (3) respiratory rhythm generation in isolated neonatal brainstem-spinal cord preparations, and (4) the response of the respiratory control system to an ensuing immune challenge. Dams were exposed to daily bouts of intermittent hypoxia (GIH) or normoxia (GNX) for 12 days prior to giving birth (G10-G21; pups were never directly exposed to intermittent hypoxia). Brainstem and spinal cord tissues were harvested from neonatal GIH and GNX offspring to quantify pro-inflammatory gene expression and to study respiratory-related rhythms in vitro.

2. Methods

All animal experimental procedures were performed according to the NIH guidelines set forth in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.1. Intermittent hypoxic exposures during pregnancy

Timed pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats (gestational age G9) were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) and housed in AAALAC-accredited facilities with 12 h:12 h light-dark conditions. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Beginning at G10, dams were exposed to 8 h/day of intermittent hypoxia (GIH) which consisted of alternating 2-min hypoxic (10.5% O2) and normoxic (21% O2) episodes, daily for 12 days. The time down to 10.5% O2 was 45 s and the time at 10.5% O2 was 75 s; the reoxygenation time to 21% O2 was 15 s. These parameters were designed to mimic the desaturation and reoxygenation times in humans with OSA (Lim et al., 2015). O2 and N2 were piped into the cages at a speed of 15 L/min, and O2 and CO2 levels were continuously monitored and regulated by a custom-designed, computer-controlled script written in LabVIEW Software (National Instruments, New Delhi, India). The control group (GNX) received alternating episodes of room air (normoxia) with the same time and gas flow parameters as GIH dams. Both groups were housed in standard rat cages, but the lids were replaced with custom-made Plexiglas tops to deliver the gases. Prior to their expected delivery date (G21), standard filter tops were replaced to prevent direct exposure of the pups to intermittent hypoxia. Pups were utilized for electrophysiological recording and inflammatory gene expression experiments between postnatal days 0 and 3 (P0-P3). Hereafter, newborn offspring of GNX- and GIH-exposed dams are referred to as “GNX rats” and “GIH rats”, respectively.

2.2 Real-time PCR

GNX and GIH rats (P2.5-P3.5) were injected intraperitoneally with either vehicle (saline) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 0.1mg/kg) 3 h prior to sacrifice. Pups were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (O2 balance) before being decerebrated. The remaining tissue was placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), composed of (in mM): 120 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, 2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 3 KCl, and 1.25 Na2HPO4 for tissue dissections. For inflammatory gene expression analyses, brainstem (medulla and caudal pons) and cervical spinal cord tissues were flash-frozen on dry ice and stored at −80 C prior to sonication in Tri-Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Total RNA was isolated with the addition of Glycoblue reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. Inflammatory gene expression in males and females was analyzed separately, and sex was confirmed using PCR of the SRY gene (see below). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using MMLV reverse transcriptase and a cocktail of oligo dT and random primers (Promega, Madison, WI), as we have previously described (Crain et al., 2009). qPCR was performed using PowerSYBR green PCR master mix on an ABI 7500 Fast system. The ddCT method was employed to determine relative expression of IL-1β, COX-2, and TNFα relative to 18s ribosomal RNA (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) in brainstem and cervical spinal cord tissue homogenates. The primer sequences used for qPCR are shown in Table 1. Primers were designed to span introns wherever possible (Primer 3 software) and were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). Primer efficiency was assessed by use of standard curves, as we have previously reported (Crain et al., 2009). Gene transcripts were considered undetectable, and not included in statistical analyses if their CT values fell outside of the linear range of the standard curve for that primer set; for all genes assessed here, this value was ≥34 cycles.

Table 1.

| Forward Primer (5’ → 3’) | Reverse Primer (5’ → 3’) | |

|---|---|---|

| 18s | CGG-GTG-CTC-TTA-GCT-GAG-TGT-CCC | CTC-GGG-CCT-GCT-TTG-AAC-AC |

| IL-1β | GAC-TTC-ACC-ATG-GAA-CCC-GT | GGA-GAC-TGC-CCA-TTC-TCG-AC |

| COX-2 | TGT-TCC-AAC-CCA-TGT-CAA-AA | CGT-AGA-ATC-CAG-TCC-GGG-TA |

| TNFα | TGC-CAC-TTC-ATA-CCA-GGA-GA | CCG-GAC-TCC-GTG-ATG-TCT-A |

| SRY | CTA-GAG-CTG-CAC-ACC-AGT-CC | TGG-GTA-TCC-AGT-GGG-GAT-GT |

2.3. Sex determination

The genitourinary distance was visually inspected in all pups to determine sex. PCR for the sex-determining region Y gene (SRY; located on the Y chromosome) was performed to confirm visual inspection. Genomic DNA was isolated from each rat (cortex tissue samples) using Tri-Reagent (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Real-time PCR for SRY (50 ng DNA/reaction) was performed using Sybr Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). CT values for SRY in males was ≤18 and >29 in females.

2.4. Isolated neonatal rat brainstem-spinal cord preparations

Neonatal (P0-P3) Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane (O2 balance) before decerebration. The remaining tissue was placed in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF), which was composed of (in mM): 120 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 20 glucose, 2 MgSO4, 1 CaCl2, 3 KCl, and 1.25 Na2HPO4.The brainstem and spinal cord from the pontomedullary border to thoracic spinal segment T1 (Fig. 4A) was removed in ice-cold aCSF and pinned down ventral side up in a standard recording chamber (volume = 0.75 ml). The tissue was continuously bathed with oxygenated aCSF solution (26°C, aerated with 5% CO2 and 95% O2, pH = ~7.4) at a flow rate of 6–8 ml/min. The bath volume and flow rate were designed to facilitate rapid turnover of aCSF in the bath. Brainstem-spinal cord preparations were allowed to equilibrate for 50–65 min before recording data. Spontaneously produced respiratory motor bursts were recorded by attaching glass suction electrodes to ventral cervical C4-C5 nerve roots. Signals were acquired at 50 Hz, amplified (1000–10,000x) and band-pass filtered (0.1–500 Hz) using a differential AC amplifier (model 1700, A–M Systems, Everett, WA, USA) before being rectified and integrated (time constant = 50 ms) using a moving averager (MA-821/RSP, CWE, Inc., Ardmore, PA, USA; Fig. 4B). Data were collected using Axoscope hardware and software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

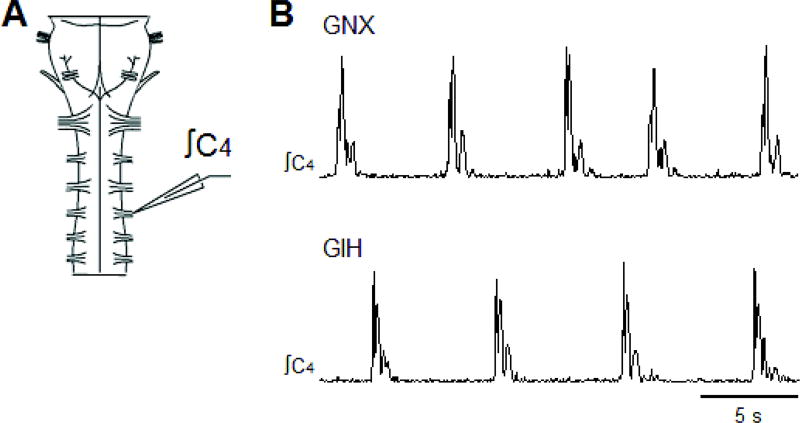

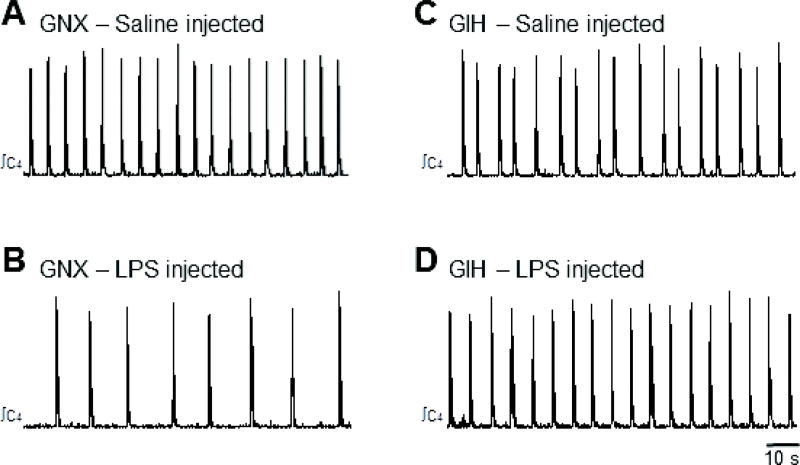

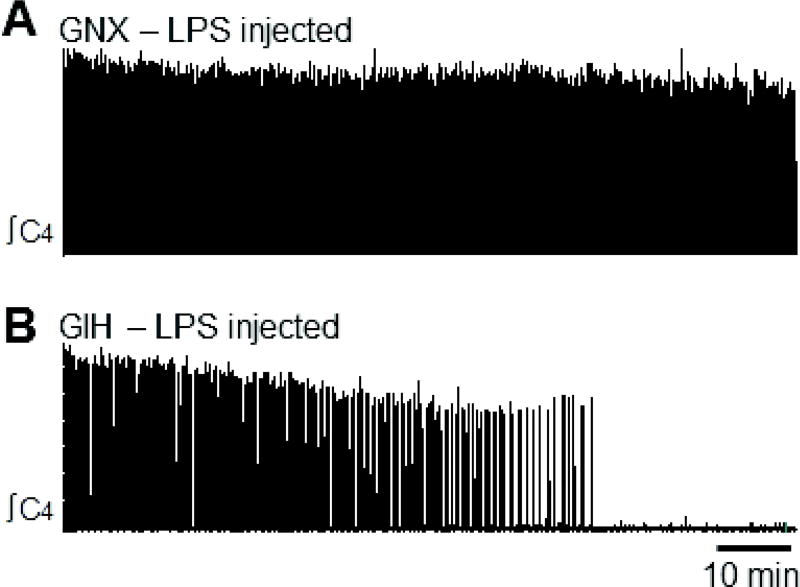

Fig. 4. Brainstem-spinal cord preparations from GNX and GIH neonatal (P0-P3) rats producing rhythmic respiratory-related motor bursts.

(A) Brainstem-spinal cord preparation with a suction electrode attached to cervical ventral spinal root C4. (B) Rhythmic motor bursts produced by GNX rat preparation (upper trace) and GIH rat preparation (lower trace).

Respiratory recordings were performed in 2 separate experiments. In the first, brainstem-spinal cord preparations from GNX and GIH rats were placed in the chamber and respiratory motor bursts were recorded. In the second, GNX and GIH rat pups were injected with saline (50 µl) or LPS dissolved in saline (40–50 µl) to deliver 0.1 mg/kg, and were returned to their mothers. In 3/13 LPS-injected GIH rats, the dosage was 1 mg/kg. There was no statistical difference between LPS doses so the data were pooled. Brainstem-spinal cords were removed 3 h after injection to record respiratory motor bursts.

2.5 Statistical analyses

qRT-PCRdata were analyzed using the ddCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001), as we have described before (Crain et al., 2013; Nikodemova and Watters, 2011). All data are graphically expressed as mean fold change + 1 SEM relative to the combined average of saline-injected male and female normoxic pups (GNX Sal), and represent individuals from at least 8 independent litters. Statistical analyses were performed on dCT values, and those identified by the Grubb’s test as falling outside of 1.96 z-scores from the mean were not included. Multivariate comparisons were performed using a two-way ANOVA (Sigma Stat version 11, Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA); Fisher’s LSD post hoc tests were used to assess statistical significance in individual comparisons. One, two, and three statistical symbols indicate p<0.05, p<0.01, and p<0.001, respectively; comparisons as indicated in the figure legends.

Voltage traces of spinal respiratory motor bursts were analyzed using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Data in the first 20-min period following equilibration of the preparation was used for analysis. Respiratory motor burst frequency was measured as bursts/min. The irregularity score was calculated as follows (Telgkamp et al., 2002): Score of the nth cycle = 100*ABS[(Pn - Pn−1)/Pn−1] with ABS = absolute value, Pn = interburst period, and Pn−1 = preceding interburst period. Burst duration was the time from the beginning to the end of the burst, and burst rise time was the time for the burst to increase from 10% to 90% of the peak amplitude at the beginning of the burst. Data are reported as mean ± SEM. Using Sigma Stat software (Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, CA, USA), a t-test was used to compare values obtained from GNX and GIH preparations, and a one-way ANOVA was used to compare values from GNX and GIH preparations pre-injected with saline of LPS. A two-way ANOVA was used to determine if there were sex-dependent effects. If the data did not satisfy the normality assumption, the data were transformed (e.g., natural log transform for irregularity score data in Figs. 5C and 8A) or the t-test was performed on ranked data if the data transformations failed (e.g. burst rise time in Figs. 5D and 8C). Statistical significance was set at p< 0.05. One and two statistical symbols indicate p<0.05 and p<0.01 respectively; comparisons as indicated in the figure legends.

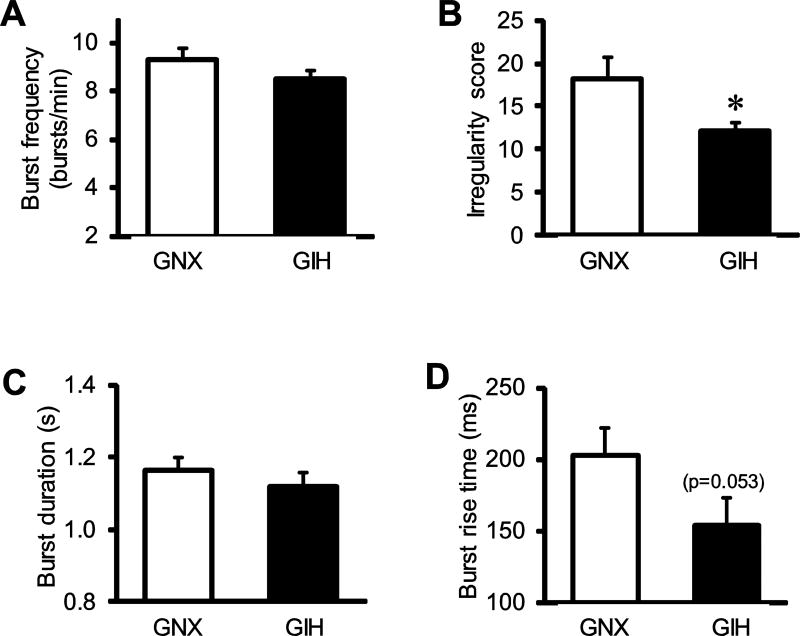

Fig. 5. Comparison of respiratory variables produced by brainstem-spinal cord preparations from GNX and GIH rats.

Baseline respiratory values from GNX (white bars) and GIH (black bars) preparations for (A) burst frequency, (B) irregularity score, (C) burst duration, and (D) burst rise time. * vs. GNX.

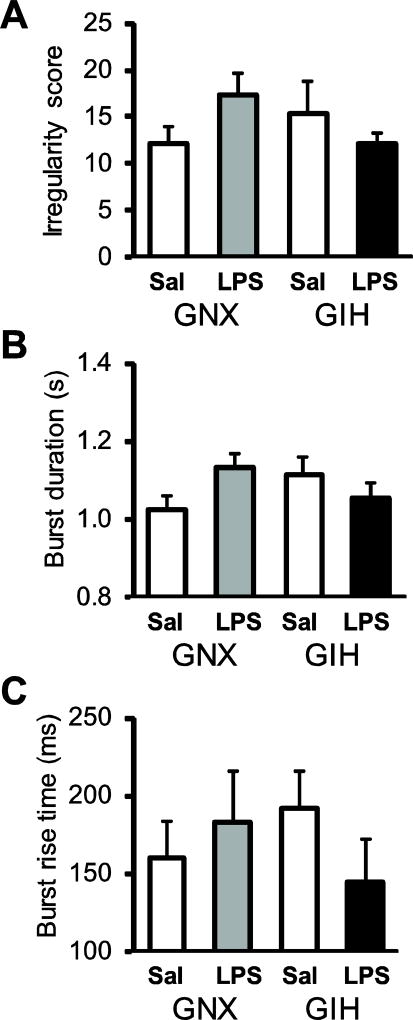

Fig. 8. GIH Respiratory variables are not changed in GIH preparations.

There were no differences between saline- or LPS-injected GNX and GIH rats with respect to irregularity score (A), burst duration (B), or burst rise time (C). Data are shown from preparations derived from saline-injected GNX (white bars), LPS-injected GNX (gray bars), saline-injected GIH (hatched bars), and LPS-injected GIH rats (black bars).

3.0 Results

3.1 GIH has gene- and region-specific effects on the basal expression levels of IL-1β, TNFα, and COX-2 in brainstem and cervical spinal cord

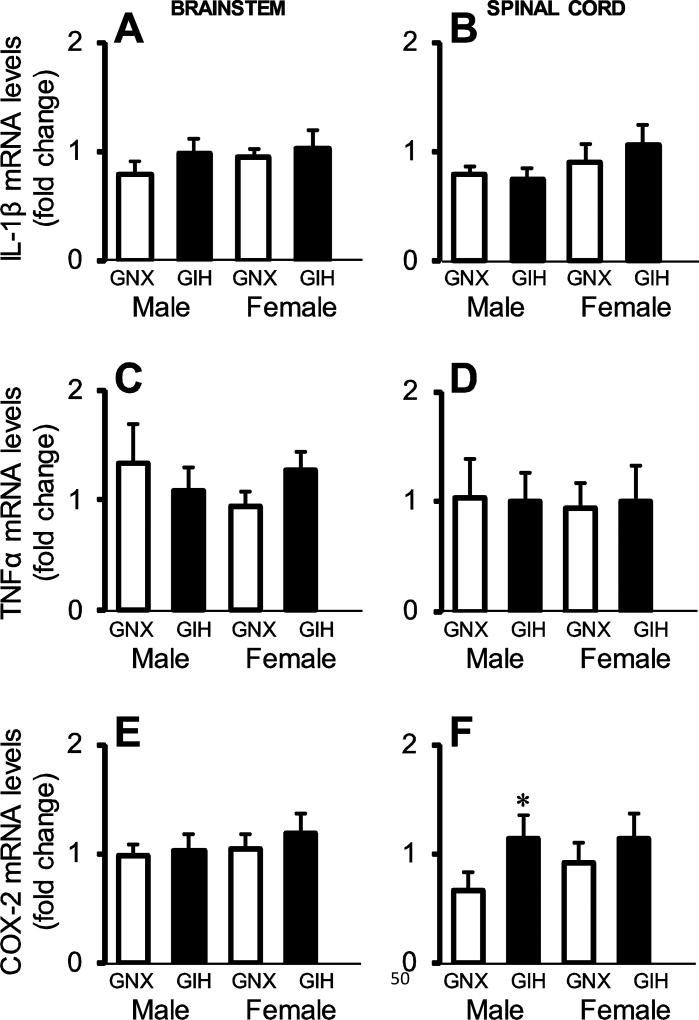

In newborn male and female rat pups (P2.5-P3.5), we evaluated the ability of GIH to increase the expression of the neuroinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα, as well as the enzyme COX-2, in CNS regions controlling breathing, brainstem and cervical spinal cord. Tissue was collected from saline-injected GNX rats (n = 17; 7 male, 10 female) and saline-injected GIH rats (n = 17, 8 male, 9 female). We hypothesized that basal expression levels would be increased by GIH in these CNS regions because these molecules negatively influence respiratory activity in neonates and/or are increased in the brainstem following neonatal hypoxic injury (Jacono et al., 2011; Olsson et al., 2003; Revuelta et al., 2017). However, contrary to our hypothesis, we did not detect expression differences in IL-1β (treatment x sex effect p = 0.922 and p = 0.872 in brainstem and spinal cord, respectively; Figs. 2A, 2B) or TNFα mRNA levels (treatment x sex effect p = 0.093 and p =0.736 in brainstem and spinal cord, Figs. 2C, 2D) in either sex. In contrast, while there were no differences in basal COX-2 mRNA levels in the brainstem (treatment x sex effect p = 0.849; Fig. 2E), GIH increased COX-2 expression in the cervical spinal cord in males (p = 0.013) but not females (p = 0.201). The difference in basal COX-2 expression between GNX males and females in the cervical cord trended towards statistical significance (p = 0.096). Thus, GIH effects on increased basal COX-2 mRNA levels were sexually dimorphic and CNS region-specific.

Fig. 2. Basal inflammatory gene expression in male and female brainstem and spinal cord tissue homogenates.

mRNA levels for IL-1β (A,B), TNFα (C,D), and COX-2 (E,F) in the brainstem (left) and spinal cord (right) in saline-injected GNX (white bars) and GIH (black bars) rats are shown. Data are graphed as fold change relative to GNX rats. GIH did not alter basal inflammatory cytokine gene expression in either sex, in either CNS region. However, GIH did elevate basal COX-2 mRNA levels in the male spinal cord. *p<0.05 vs. GIH.

3.2 GIH attenuates brainstem and cervical spinal cord neuroinflammatory responses to peripheral immune system challenge in females, but not males

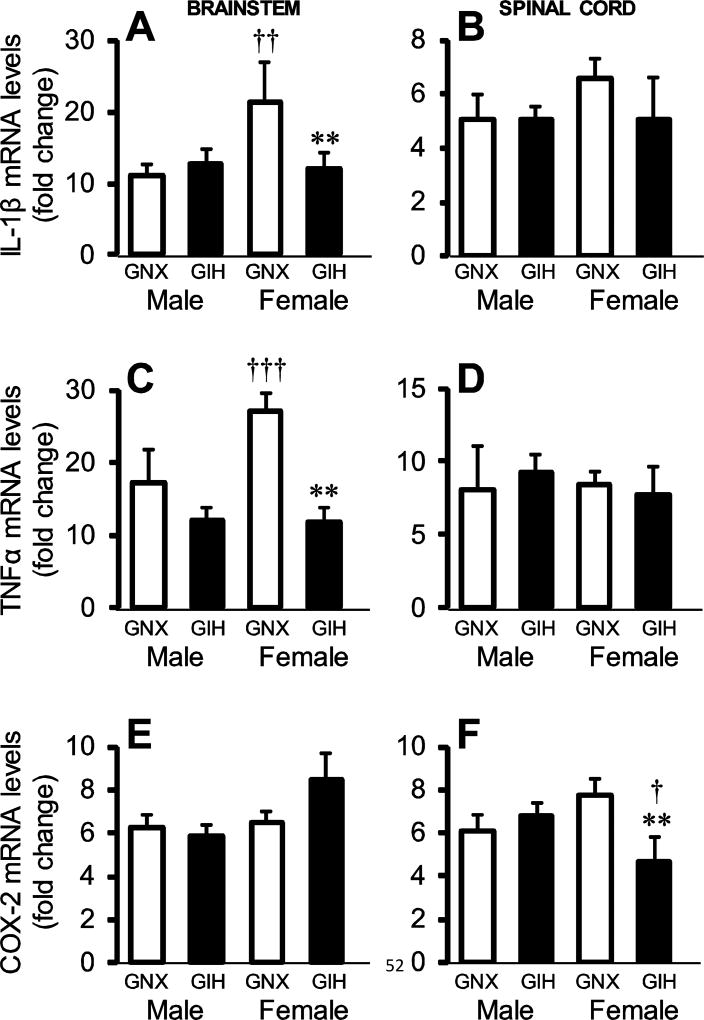

Although we did not detect a generalized increase in neuroinflammation due to GIH, we evaluated the effects of an immune challenge with Gram negative bacterial endotoxin (LPS) on the neuroinflammatory response of GNX and GIH rats (Fig. 3). As expected, in both GNX and GIH pups, LPS significantly increased the expression of all genes in pups of both sexes (p<0.001) in brainstem (GNX n=13, 6 male, 7 female; GIH n =16, 10 male, 6 female) and spinal cord (GNX n = 16, 6 male, 10 female; GIH n = 17, 10 male, 7 female). Interestingly, compared to males, female GNX pups had an augmented IL-1β response to LPS (p = 0.007; treatment x sex effect p = 0.028) in the brainstem (Fig. 3A). The IL-1β response to LPS in males was not different between GNX and GIH (p = 0.673), but GIH females had a blunted response compared to GNX females (p = 0.009). In cervical spinal cord, there was no effect of GIH on the LPS-induced IL-1β response in either sex or treatment group, although there was a trend (treatment x sex effect p = 0.061; Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. GIH alters neuroinflammatory responses to immune challenge in the female brainstem and spinal cord.

mRNA levels for IL-1β (A,B), TNFα (C,D), and COX-2 (E,F) in the brainstem (left) and spinal cord (right) in saline-injected GNX (white bars) and GIH (black bars) rats are shown. Data are graphed as fold change relative to saline-injected GNX rats. * vs. GNX female. † vs. same treatment male.

Brainstem TNFα gene expression (Fig. 3C) mirrored the brainstem IL-1β response. LPS-induced TNFα gene expression was higher in GNX females than GNX males (p<0.001; treatment x sex effect p = 0.04), but much reduced in GIH females (p = 0.006), while the LPS response in GIH males was unchanged compared to GNX males (p = 0.958). Again, in the cervical spinal cord (Fig. 3D), the LPS-induced increase in TNFα gene expression in GNX and GIH pups was not different between males and females (treatment x sex effect p = 0.588).

Unlike regulation of the cytokine genes, LPS-induced COX-2 expression in the brainstem (Fig. 3E) did not differ between GNX and GIH pups in either males or females (treatment x sex effect p = 0.974). However, in the cervical spinal cord, while LPS-induced COX-2 expression did not differ between GNX and GIH males (p = 0.541), it was impaired in GIH females (p = 0.005; treatment x sex effect p = 0.014). The ability of LPS to induce COX-2 gene expression also differed in GIH males and females, but not GNX animals (p = 0.221), with GIH females having a blunted response compared to males (p = 0.02). Together, these data suggest that females exposed to GIH have an impaired ability to mount a normal neuroinflammatory response to a peripheral immune challenge in two important CNS regions essential to the neural control of breathing.

3.3. GIH-dependent changes in neonatal respiratory motor output and responses to LPS

Given the deficits in neuroinflammatory responses in key CNS regions controlling breathing, we next evaluated the respiratory rhythm in neonates of the same age using reduced brainstem-spinal cord preparations (Fig. 4). Spontaneous respiratory motor output was compared for brainstem-spinal cord preparations isolated from GNX rats (n = 21; 11 male, 10 female) and GIH rats (n = 17, 8 male, 9 female). Although age-dependent (P0-P4) effects for rat medullary brainstem-spinal cord preparations are not observed with respect to burst frequency (Fong et al., 2008), neonatal rat age was roughly matched for GNX and GIH rats to avoid potential age-dependent effects due to gestational gas exposures. The average ages of the GNX and GIH rats were 40.8 ± 5.6 and 41.4 ± 5.0 h, respectively. Compared to GNX, burst frequency was unchanged by GIH (GNX: 9.3 ± 0.5 bursts/min; GIH: 8.5 ± 0.4 bursts/min; p = 0.162; Fig. 5A). However, the rhythm produced by GIH preparations was more regular than that produced by GNX preparations (p = 0.03; Fig. 5B). Respiratory motor burst duration was similar between GNX (1.16 ± 0.03 s) and GIH preparations (1.12 ± 0.04 s; p = 0.40; Fig. 5C), but there was a strong trend for a lower burst rise time in bursts from GIH preparations (p = 0.053; Fig. 5D). There were no significant sex-dependent effects between GNX and GIH rats with respect to these variables.

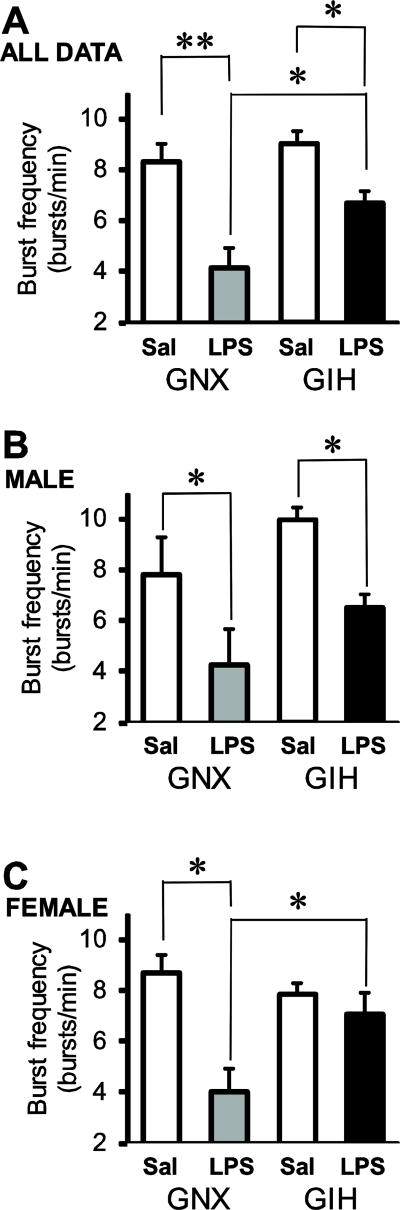

To test whether respiratory motor output was altered by LPS-induced inflammation, GNX and GIH rats were injected with saline or LPS (0.1 mg/kg) 3 h before isolating their brainstem-spinal cord preparations. LPS decreased respiratory motor burst frequency in GNX rat brainstem-spinal cord preparations, but this effect was attenuated in GIH rats (Fig. 6). Burst frequency in preparations from LPS-injected GNX rats (n = 8; 4 male, 4 female) was decreased to 4.2 ± 0.8 bursts/min from 8.3 ± 0.8 bursts/min in saline-injected rats (n = 13; 6 male, 7 female; p<0.001; Fig. 7A). Likewise, burst frequency in preparations from LPS-injected GIH rats (n = 13; 8 male, 5 female) decreased less significantly to 6.7 ± 0.5 bursts/min from 9.1 ± 0.5 bursts/min in preparations from saline-injected GIH rats (n = 13; 6 male, 7 female; p = 0.032; Fig. 7A). Burst frequencies following LPS treatment were significantly different between GNX and GIH preparations (p = 0.009; Fig. 7A).

Fig. 6. LPS pretreatment reduces burst frequency in preparations from GNX but not GIH rats.

Respiratory-related motor bursts produced in a saline-injected GNX (A) and LPS-injected (0.1 mg/kg) GNX rat preparation (B). LPS pretreatment reduced baseline burst frequency in GNX rats. In contrast, in GIH preparations, the burst frequency was similar between saline- (C) and LPS-injected (D) rats.

Fig. 7. Normal reductions in burst frequency induced by LPS are blunted in brainstem-spinal cord preparations from GIH rats.

(A) Burst frequency from averaged pooled male and female preparations show that LPS treatment reduces burst frequency in GNX and GIH rats. (B) Male preparations from both GNX and GIH rats show decreased burst frequency data upon LPS treatment. (C) In contrast, in GIH female preparations, the LPS-induced reduction in burst frequency is blunted. Data are shown from preparations derived from saline-injected GNX (white bars), LPS-injected GNX (gray bars), saline-injected GIH (hatched bars), and LPS-injected GIH rats (black bars). *p<0.05 and **p<0.01.

The LPS-induced frequency decrease was both sex- and treatment-dependent because LPS injections significantly decreased burst frequency in GNX and GIH preparations compared to saline-injected controls in males (Fig. 7B), but not in females (Fig. 7C). For males, LPS-treatment significantly reduced burst frequency in both GNX (p = 0.033) and GIH (p = 0.016) preparations with no difference in burst frequency between LPS-injected GNX and GIH preparations (p = 0.092; Fig. 7B). For females, LPS-treatment significantly reduced burst frequency in GNX (p = 0.005), but not GIH (p = 0.546) preparations (Fig. 7C). Burst frequency in LPS-injected GNX preparations was decreased compared to LPS-injected GIH preparations (p = 0.037; Fig. 7C). There were no differences between preparations from saline- and LPS-injected GNX and GIH rats with respect to rhythm irregularity (p = 0.24 for treatment effect, p = 0.63 for sex effect), burst duration (p = 0.27 for treatment effect, p = 0.43 for sex effect), and burst rise time (p = 0.76 for treatment effect, p = 0.88 for sex effect; Fig. 8). The average ages of the GNX and GIH rats were 44.1 ± 4.2 and 42.8 ± 3.9 h, respectively.

Although data during the first 20 min of recording (after preparation equilibration) are shown in Figs. 5–8, all recordings were performed for at least 100 min. Rhythmic motor bursts were produced for the full 100 min in all preparations from GNX and GIH rats, as well as most preparations from saline-injected GNX and GIH rats (Fig. 9A). In one preparation from a saline-injected GNX rat, rhythmic motor bursts stopped after 58 min. In contrast, LPS injections caused preparations from some GNX and GIH rats to stop producing rhythmic motor bursts (Fig. 9B). LPS injection caused 2/8 preparations from GNX rats to stop producing motor bursts after 50 and 80 min, and 2/13 preparations from GIH rats to stop producing motor bursts after 68 and 72 min.

Fig. 9. Respiratory-related motor bursts stop in some brainstem-spinal cord preparations from LPS-treated GIH animals.

(A) Preparation from LPS-injected GNX rat continues to produce motor bursts. (B) Preparation from LPS-injected GIH rat stops producing motor bursts after 58 min.

4.0 Discussion

This study is the first to begin to address some of the important gaps in knowledge regarding respiratory and neuroinflammatory consequences to neonatal offspring of mothers exposed to intermittent hypoxia due to SDB. Here, we: 1) quantified pro-inflammatory gene expression in offspring from pregnant rats exposed to GIH, 2) assessed alterations in offspring neuroinflammatory responses to a subsequent postnatal immune system challenge, 3) examined the effects of GIH on respiratory motor control using isolated in vitro brainstem-spinal cord preparations, which permit quantification of motor output without potentially confounding factors, such as alterations in peripheral chemosensation (carotid body) or interactions with the cardiovascular control system, and finally, 4) evaluated sex-dependent differences in gene expression and respiratory motor control in GIH offspring. While GIH itself did not generally increase pro-inflammatory gene expression in the brainstem or spinal cord, it altered offspring response to a subsequent postnatal inflammatory challenge, in a sex-dependent manner. Further, the effects of GIH on attenuating the normal response to LPS was gene- and CNS region-specific. Interestingly, the normally large decrease in burst frequency induced by LPS in brainstem-spinal cord preparations from GNX pups was blunted in GIH rats. Preparations from both male and female GIH rats showed an attenuated LPS-dependent decrease in burst frequency, but this effect was more pronounced in females. Our working hypothesis is that intermittent hypoxia during pregnancy re-programs the neuroinflammatory response in females particularly, such that they become tolerant, thereby producing less cytokines (e.g., IL-1β) that normally decrease respiratory rhythm frequency. Whether this represents a beneficial adaptation, or a detrimental consequence, remains to be tested.

4.1. GIH-induced changes in neuroinflammation in brainstem and spinal cord

Paradigms of intermittent hypoxia that mimic OSA cause neuroinflammation in adult rats, depending on the level of hypoxia and duration of the hypoxic exposures. For example, intermittent hypoxia (2 min 21% O2 / 2 min 10.5% O2, × 8/day, 14 days) increases inflammatory gene expression in several CNS regions (Smith et al., 2013) and reviewed in (Kiernan et al., 2016; Navarrete-Opazo and Mitchell, 2014). In contrast to numerous studies in adult rodents, intermittent hypoxia-induced neuroinflammation was only recently demonstrated in P13 and P18 rat pups that were directly exposed to intermittent hypoxia from P2-P12 (Darnall et al., 2017). In GIH offspring in the present study, we found no evidence that GIH generally enhanced basal pro-inflammatory gene expression in the brainstems of GIH offspring at least for the genes analyzed here, although GIH did increase basal COX-2 expression in the spinal cord. In contrast to the intermittent hypoxia-induced neuroinflammatory response in adult and neonatal rats, the lack of a neuroinflammatory response in GIH neonates may be explained by the following. First, the extent to which GIH treatment alters fetal CNS PO2 levels is not known. This is a difficult variable to measure, and there are no studies attempting to absolutely quantify brain tissue PO2 levels in rat fetuses. The fetus may be able to maintain arterial PO2 near normal levels and blunt PO2 changes resulting from intermittent bouts of maternal hypoxemia. For example, although blood PO2 levels in the fetal brain increase during maternal hyperoxia (breathing 100% oxygen; Aldrich et al., 1994), fetal brain tissue PO2 does not appear to be influenced (Huen et al., 2014) because the placenta is partially protective during hypoxia (Arthuis et al., 2017). Thus, GIH may be unable to cause the hypoxia necessary to induce neuroinflammation in the fetal brain. Second, the fetus is already chronically hypoxic; human umbilical cord blood PO2 levels are typically below 40 mm Hg (Siggaard-Andersen and Huch, 1995). Since the fetal CNS is already severely hypoxic, it may not be able to respond to further, transient decreases in tissue PO2 during GIH exposures. In contrast, bouts of intermittent hypoxia in neonates or adults represent a much larger decrease in PO2 from a much higher baseline PO2 level.

In this study, GIH rats had impaired responses to an inflammatory challenge that was gene-, sex- and CNS region-specific. For example, LPS-induced cytokine but not COX-2 responses were decreased in the brainstem of GIH rats. However, this did not occur in the spinal cord, and was only observed in females. These data suggest that specific inflammatory genes are differentially regulated by GIH, responses that differ by CNS region. Sex differences to LPS challenge were noted both in GNX and GIH pups, with female GNX rats responding more strongly to LPS than their male counterparts. While LPS responses between GIH males and females did not differ, GIH females had a blunted response to LPS compared to responses in GNX females. Thus, one could argue that GIH simply reveals or exacerbates existing sex-differences in LPS responses in females. But observations in the spinal cord for COX-2 may argue against this possibility; LPS-induced COX-2 gene expression is not different between GNX males and females, but GIH still attenuates the LPS response in GIH females.

The recurring theme is that GIH decreases LPS-induced pro-inflammatory gene expression in females, but not males. Mechanisms underlying these sex-dependent differences are not known, but sex differences in CNS cells and CNS cell responses to immune challenge are well-known. For example, microglia display considerable heterogeneity in their immune function depending on both sex and CNS region (Crain et al., 2009; Crain et al., 2013; Crain and Watters, 2015; Hanamsagar et al., 2017; Hanamsagar and Bilbo, 2016; Schwarz and Bilbo, 2012). Sex- and region-dependent differences in microglial activities could explain the differences in neuroinflammatory responses to postnatal immune challenge in GIH pups. In addition, astrocytes and neurons also produce cytokines and may exhibit similar variability in their responses to immune challenge (Ramesh et al., 2013). One caveat with our experiments is that these gene expression studies were performed on large blocks of tissue containing neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, as well as vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and connective tissue. The overall gene expression response is the sum of all the activities of these different cell types. Quantifying the responses of specific cell types, especially microglia and astrocytes, would greatly aid in our understanding of how GIH alters brain function.

What role might maternal stress play in our model of GIH? Since gestational stress alters microglia function (Slusarczyk et al., 2015) and disturbs breathing in postnatal rats (Fournier et al., 2013), it is possible that our findings may involve stress-related changes in the mother in response to the intermittent hypoxia, that then result in fetal CNS changes. A key question is whether the intermittent hypoxic exposure protocol used in these experiments (2-min 10.5% O2 / 2-min 21% O2, 8 h/d, 12d) is sufficient to cause maternal stress in pregnant dams. Exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia increases cortisol levels in adult rats, but the protocol was more severe (6% O2 for 40 s every 9 min, 8 h/d, 35d) and only males were tested (Zoccal et al., 2007) In contrast, intermittent hypoxia (3 min 10.5% O2 / 3-min 21% O2, 8h/d, 7d) in adult male rats did not demonstrate an increase in plasma ACTH levels using an intermittent hypoxia protocol more similar to ours (Ma et al., 2008). Significant differences in offspring stress responses were observed only when the offspring were subjected to another stressor, such as immobilization (Ma et al., 2008). Thus, further experiments will be required to determine whether intermittent hypoxia-induced maternal stress disrupts the offspring hypothalamic-pituitary axis and contributes to changes in neuroinflammatory function and respiratory motor output in vitro observed in this study.

4.2. GIH-induced alterations in respiratory rhythm generation in vitro

Little is known regarding the effects of GIH on respiratory motor control in offspring, especially in young neonates. In one study, GIH-exposed P5 rats had increased ventilation and lower hypoxic ventilatory responses (Gozal et al., 2003), but specific features of respiratory rhythm generation were not examined, such as apneas or rhythm regularity. In addition, there are no studies that examined the effects of inflammation on respiratory rhythm in GIH offspring. The present study examined respiratory motor output produced by P0-P3 isolated brainstem-spinal cord preparations (Johnson et al., 2012). Brainstem-spinal cord preparations are advantageously isolated from circulating factors (including inflammatory cytokines produced in the periphery) and peripheral chemo- and mechanoreceptor input that can influence respiratory rhythm generation.

We found no treatment-dependent changes in respiratory burst frequency, duration or rise-time in preparations from GNX and GIH rats. Our results are in agreement with the observation that ventilation is increased in P5 GIH-treated rats due to an increase in tidal volume only, without changes in breath frequency (Gozal et al., 2003). The nature of our experiments on isolated brainstem-spinal cord preparations prevents us from determining whether the amplitude of spinal respiratory motor output was increased by GIH (i.e., absolute measurement of burst amplitude is not possible with suction electrodes). The significance of increased rhythm regularity in preparations from GIH rats remains unclear because the neurochemical-dependent mechanisms that modulate rhythm regularity are complex (Doi and Ramirez, 2008). In isolated brainstem-spinal cord preparations or rhythmically active thick medullary slices, several neurochemical systems are required to maintain the regularity of respiratory motor bursts, including serotonin 5HT2 receptors (Pena and Ramirez, 2002) and NK1 receptors activated by substance P (Telgkamp et al., 2002). GIH may alter the abundance or release of one or more of these neurotransmitters or their receptors on neurons responsible for generating or modulating respiratory rhythm frequency and regularity. Is the increased regularity of breathing rhythm in GIH rats beneficial/adaptive or pathological? Decreases in heartbeat variability are known to correlate with potential cardiovascular disease (Chen et al., 2012b), but the significance of changes in breathing frequency variability with respect to disease are poorly understood. Breath-to-breath timing of inspiration and expiration are being used to distinguish between different types of patients with OSA (Yamauchi et al., 2011), but little is known regarding whether changes in breathing regularity in neonates is indicative of ongoing respiratory pathology. However, increased rhythm regularity reflects a limited dynamic range, and is associated with respiratory disease in adults (Jacono, 2013). On the one hand, the GIH-induced increases in regularity could be beneficial because they may help prevent apneas that are common in newborn or preterm infants. But on the other hand, an increase in regularity could reflect a pathological change in normal neurochemical mechanisms that control the dynamic range of breathing timing, an effect that may be revealed by hypoxic or hypercapnic challenge.

There is a robust literature documenting the effects of inflammatory stimuli (particularly LPS, IL-1β, PGE2) on respiratory function in several species at different postnatal ages. However, administration of pro-inflammatory molecules produces different, often opposite effects on respiratory motor control, particularly respiratory frequency. For example, LPS administration in P10–11 rat pups increases diaphragm burst frequency (Gresham et al., 2011) and attenuates the hypoxic ventilatory response (Balan et al., 2011; Master et al., 2015); Ribeiro et al., 2017), presumably by adversely changing carotid body function (Master et al., 2016). In contrast, IL-1β injection into the nucleus tractus solitarius of isolated neonatal rat brainstem-spinal cord preparations decreases respiratory burst frequency (Gresham et al., 2011). In intact neonatal rats and piglets, IL-1β administration likewise decreases breathing frequency (Froen et al., 2000; Hofstetter et al., 2007; Olsson et al., 2003). To complicate matters further, LPS-induced increases in IL-1β production increases COX-2 levels, which increase PGE2 production (Herlenius, 2011). Although PGE2 injection into the preBötzinger Complex of thick murine medullary slices increases burst frequency (Koch et al., 2015), other studies in intact newborn and fetal lambs indicate that PGE2 administration decreases breathing frequency (Guerra et al., 1988; Kitterman et al., 1983; Tai and Adamson, 2000) (Savich et al., 1995). TNFα may participate in LPS-induced changes in chemosensory activity (Fernandez et al., 2008), but the effects of TNFα on respiratory rhythm-generating neurons in neonates is not known. Thus, the net effect of inflammation on respiratory motor control involves complex interactions between multiple inflammatory molecules in different CNS regions involved in rhythm generation and modulation; additional studies are required to tease apart these multifaceted effects.

In this study, brainstem-spinal cords from young P0-P3 rats were harvested 3 h after peripheral LPS injection, thereby eliminating input from the carotid body during the recordings. In preparations from GNX rats, LPS decreased respiratory burst frequency, whereas in preparations from GIH female rats, burst frequency was maintained after LPS. This suggests that GIH may protect females against subsequent inflammatory challenges because an LPS-induced decrease in breath frequency in neonate already struggling to breathe without apneas would compound the problem. The mechanism underlying the GIH-dependent attenuation of the LPS response in females is not known. One could speculate that this is due to the impaired upregulation of IL-1β following LPS challenge in females, but this study examined gene expression for only three pro-inflammatory molecules. There are likely changes in the expression of many other inflammation-related factors that could modulate respiratory burst frequency. Whether attenuated LPS-induced frequency decrease in GIH rats is beneficial or protective is still open to question and remains to be directly tested. It is important to note that we have not yet demonstrated a causal link between impaired inflammation and respiratory rhythm disturbances in GIH offspring. However, these initial observations, together with the emerging human literature of negative pregnancy outcomes, underscore the need for such investigations in the future.

4.3. Unanswered questions regarding SDB/OSA during pregnancy and GIH

There is growing interest in understanding the causes, developing treatment(s), and assessing clinical outcomes of SDB/OSA during pregnancy. With the paucity of animal studies in this area, there remains many questions and gaps in knowledge. A primary concern of SDB/OSA is the short-term health of both the mother and newborn infant, and the long-term consequences on juvenile and adult offspring. Some of these unanswered questions include whether GIH due to maternal OSA alters blood flow to the placenta, or impacts nutrient/gas exchange across the placental/fetal barrier? Does OSA and GIH alter sex hormone levels during pregnancy, predisposing to preterm delivery? Progesterone levels were lower in women with OSA, suggesting that progesterone might be protective against OSA (Lee et al., 2017). What roles do sex hormones play in contributing to or preventing SDB/OSA during pregnancy?

Using GIH as a model of SDB/OSA, our data suggest that the ability of GIH offspring to respond to a pro-inflammatory challenge is impaired in the early perinatal period. How long does this impairment last? Do GIH offspring recover over time, or does this impairment persist in juvenile and adult offspring? If so, how might these persistent changes be encoded at the cellular level? Are epigenetic mechanisms responsible for the long-lasting impairment in responses to pro-inflammatory challenges? Is it possible to reverse the GIH-induced impairment of the pro-inflammatory response, and if so, does that restore normal respiratory function? Also, does GIH alter normal fetal and postnatal development? Does it delay the normal sequence of events associated with respiratory system maturation?

4.4. Clinical and scientific significance

Our results show that GIH attenuates the normal inflammatory and respiratory rhythm responses to an immune system challenge in neonatal rats, particularly in females. If female GIH offspring have an impaired ability to mount a proper CNS immune response (akin to an immune tolerance), they may be less able to mount a protective neuroinflammatory response when confronted with an infection after birth, and perhaps even also later in development or adulthood. This may predispose the GIH offspring to a host of respiratory and other morbidities and pathologies later in life. The current treatment for SDB during pregnancy is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP; (Guilleminault et al., 2004)). Importantly however, CPAP only reverses some of the adverse maternal and fetal outcomes (Carnelio et al., 2017). For example, nasal CPAP treatment of pregnant women with preeclampsia risk factors allowed them to maintain mean blood pressures, but it did not prevent the negative pregnancy outcomes, such as miscarriage, premature delivery, neonatal intensive care admission, and caesarean delivery of a premature infant (Guilleminault et al., 2007). A separate study of hypertensive pregnant women showed that blood pressures were lower in the CPAP-treated group and none experienced complicated pregnancies, but the delivered infants had higher APGAR scores (Poyares et al., 2007). Thus, CPAP treatment early during pregnancy in high risk patients holds promise, but larger studies are needed. The literature, together with the data presented here, suggest that SDB/OSA needs to be identified more aggressively, especially in obese pregnant women with hypertensive disorders, and treated as early as possible during pregnancy.

There is a pressing need to develop experimental animal models mimicking the effects of SDB/OSA in pregnant women. Pregnant rodents (or larger animals such as pigs and sheep) exposed to intermittent hypoxia during pregnancy will allow the study of the effects of GIH on both the mother and the offspring. Obese or hypertensive rodent models could be used to determine how these risk factors exacerbate the effects of GIH. Another intriguing hypothesis is that maternal SDB predisposes the children (and adult offspring?) to OSA. This is supported by observations that children born preterm to mothers with SDB are more likely to exhibit childhood OSA (Rosen et al., 2003; Tapia et al., 2016; Walfisch et al., 2017). Preterm delivery is thought to compromise development of the upper airways, resulting in a higher risk of childhood OSA (Walfisch et al., 2017). A retrospective study of >240,000 deliveries indicated a 2–3 times higher incidence of OSA-related hospitalizations of the offspring (up to the age of 18 years) in preterm deliveries compared to full to late term deliveries (Walfisch et al., 2017). Thus, it is striking that a relatively brief in utero exposure to intermittent hypoxia due to maternal SDB predisposes the offspring to suffer from SDB during their lifetime. Clearly, the significant health implications for the mother, fetus, infant, and even adults requires further investigation to identify and then minimize/reverse the negative consequences of intermittent hypoxia during pregnancy.

Highlights.

Sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) during pregnancy is a growing clinical problem

Fetal exposure to intermittent hypoxia has deleterious effects

Gestational intermittent hypoxia in rats altered CNS immune response to LPS challenge

Gestational intermittent hypoxia in rats altered respiratory motor responses to LPS

Long-term consequences of SDB require further investigation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NS085226 (JJW), HL105511 (TLB), NIH 2T35OD011078-06 (KSR and JJE), and the University of Oregon (ADH and AGH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agosto-Marlin IM, Nichols NL, Mitchell GS. Adenosine-dependent phrenic motor facilitation is inflammation resistant. J Neurophysiol. 2017;117:836–845. doi: 10.1152/jn.00619.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amfilochiou A, Tsara V, Kolilekas L, Gizopoulou E, Maniou C, Bouros D, Polychronopoulos V. Determinants of continuous positive airway pressure compliance in a group of Greek patients with obstructive sleep apnea. European journal of internal medicine. 2009;20:645–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony KM, Agrawal A, Arndt ME, Murphy AM, Alapat PM, Guntupalli KK, Aagaard KM. Obstructive sleep apnea in pregnancy: reliability of prevalence and prediction estimates. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2014;34:587–593. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthuis CJ, Novell A, Raes F, Escoffre JM, Lerondel S, Le Pape A, Bouakaz A, Perrotin F. Real-Time Monitoring of Placental Oxygenation during Maternal Hypoxia and Hyperoxygenation Using Photoacoustic Imaging. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awe RJ, Nicotra MB, Newsom TD, Viles R. Arterial oxygenation and alveolar-arterial gradients in term pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1979;53:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan KV, Kc P, Hoxha Z, Mayer CA, Wilson CG, Martin RJ. Vagal afferents modulate cytokine-mediated respiratory control at the neonatal medulla oblongata. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;178:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bende M, Gredmark T. Nasal stuffiness during pregnancy. The Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1108–1110. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199907000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Schwarz JM. The immune system and developmental programming of brain and behavior. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2012;33:267–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bin YS, Cistulli PA, Ford JB. Population-Based Study of Sleep Apnea in Pregnancy and Maternal and Infant Outcomes. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2016;12:871–877. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Cousens S, Johnson HL, Lawn JE, Rudan I, Bassani DG, Jha P, Campbell H, Walker CF, Cibulskis R, Eisele T, Liu L, Mathers C. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2008: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1969–1987. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60549-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borday C, Vias C, Autran S, Thoby-Brisson M, Champagnat J, Fortin G. The pre-Botzinger oscillator in the mouse embryo. Journal of physiology, Paris. 2006;100:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourjeily G, El Sabbagh R, Sawan P, Raker C, Wang C, Hott B, Louis M. Epworth sleepiness scale scores and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Sleep Breath. 2013;17:1179–1186. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao-Lei L, de Rooij SR, King S, Matthews SG, Metz GAS, Roseboom TJ, Szyf M. Prenatal stress and epigenetics. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnelio S, Morton A, McIntyre HD. Sleep disordered breathing in pregnancy: the maternal and fetal implications. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2017;37:170–178. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2016.1229273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan GJ, Lee AC, Baqui AH, Tan J, Black RE. Prevalence of early-onset neonatal infection among newborns of mothers with bacterial infection or colonization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2015;15:118. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0813-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Kang JH, Lin CC, Wang IT, Keller JJ, Lin HC. Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012a;206:136, e131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Purdon PL, Brown EN, Barbieri R. A unified point process probabilistic framework to assess heartbeat dynamics and autonomic cardiovascular control. Frontiers in physiology. 2012b;3:4. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chintamaneni K, Bruder ED, Raff H. Effects of age on ACTH, corticosterone, glucose, insulin, and mRNA levels during intermittent hypoxia in the neonatal rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R782–789. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00073.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti M, Izzo V, Muggiasca ML, Tiengo M. Sleep apnoea syndrome in pregnancy: a case report. European journal of anaesthesiology. 1988;5:151–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain J, Nikodemova M, Watters J. Expression of P2 nucleotide receptors varies with age and sex in murine brain microglia. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2009;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain JM, Nikodemova M, Watters JJ. Microglia express distinct M1 and M2 phenotypic markers in the postnatal and adult central nervous system in male and female mice. Journal of Neuroscience Research. 2013;91:1143–1151. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain JM, Watters JJ. Microglial P2 Purinergic Receptor and Immunomodulatory Gene Transcripts Vary By Region, Sex, and Age in the Healthy Mouse CNS. Transcriptomics: open access 3. 2015 doi: 10.4172/2329-8936.1000124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dammann O, Kuban KC, Leviton A. Perinatal infection, fetal inflammatory response, white matter damage, and cognitive limitations in children born preterm. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews. 2002;8:46–50. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.10005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnall RA, Chen X, Nemani KV, Sirieix CM, Gimi B, Knoblach S, McEntire BL, Hunt CE. Early postnatal exposure to intermittent hypoxia in rodents is proinflammatory, impairs white matter integrity, and alters brain metabolism. Pediatr Res. 2017;82:164–172. doi: 10.1038/pr.2017.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding M, Pierre BAS, Parkinson JF, Medberry P, Wong JL, Rogers NE, Ignarro LJ, Merrill JE. Inducible Nitric-oxide Synthase and Nitric Oxide Production in Human Fetal Astrocytes and Microglia. A KINETIC ANALYSIS. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:11327–11335. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.17.11327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XX, Wu YL, Xu SJ, Zhang SF, Jia XM, Zhu RP, Hao JH, Tao FB. A systematic review and quantitative assessment of sleep-disordered breathing during pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. Sleep Breath. 2014;18:703–713. doi: 10.1007/s11325-014-0946-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi A, Ramirez JM. Neuromodulation and the orchestration of the respiratory rhythm. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2008;164:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards N, Blyton DM, Hennessy A, Sullivan CE. Severity of sleep-disordered breathing improves following parturition. Sleep. 2005;28:737–741. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.6.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards N, Middleton PG, Blyton DM, Sullivan CE. Sleep disordered breathing and pregnancy. Thorax. 2002;57:555–558. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.6.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facco FL, Ouyang DW, Zee PC, Grobman WA. Sleep disordered breathing in a high-risk cohort prevalence and severity across pregnancy. American journal of perinatology. 2014;31:899–904. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]