Abstract

In flowering plants, fertilization requires complex cell-to-cell communication events between the pollen tube and the female reproductive tissues, which are controlled by extracellular signaling molecules interacting with receptors at the pollen tube surface. We found that two such receptors in Arabidopsis, BUPS1 and BUPS2, and their peptide ligands, RALF4 and RALF19, are pollen tube–expressed and are required to maintain pollen tube integrity. BUPS1 and BUPS2 interact with receptors ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 via their ectodomains, and both sets of receptors bind RALF4 and RALF19. These receptor-ligand interactions are in competition with the female-derived ligand RALF34, which induces pollen tube bursting at nanomolar concentrations. We propose that RALF34 replaces RALF4 and RALF19 at the interface of pollen tube–female gametophyte contact, thereby deregulating BUPS-ANXUR signaling and in turn leading to pollen tube rupture and sperm release.

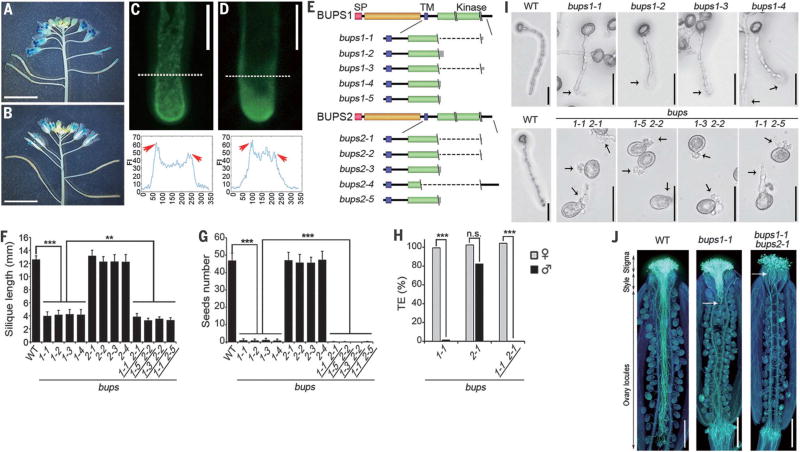

In angiosperms, unlike animals, gametes are embraced in multicellular haploid gametophytes. To accomplish sexual reproduction, two nonmotile sperm cells are delivered as passive cargoes of the pollen tube, representing the male gametophyte, to the female gametes (1).The guided growth, reception, and rupture of the pollen tube are essential for successful fertilization, which entails signaling, often through receptor-like kinases (RLKs) (2–6), between male and female tissues (7–10). In Arabidopsis, CrRLK1L (Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like subfamily) receptors regulate cell expansion (11–17) and function in pollen tube reception at the point of contact with the female gametophyte (2, 3, 18). FERONIA (FER), a CrRLK1L receptor expressed in the female gametophyte, is essential for pollen tube reception (18, 19). Another two CrRLK1L receptors, ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 (ANX1/2), expressed in the pollen tube, prevent precocious pollen tube rupture (2, 3). To more comprehensively understand these signaling networks, we identified two CrRLK1L members containing typical extracellular malectin domains and named them Buddha’s Paper Seal l (BUPS1, At4g39110) and BUPS2 (At2g21480) on the basis of the pollen tube phenotypes of their knockout mutants, as described below. Promoter-GUS (β-glucuronidase) analysis showed that both BUPS1 and BUPS2 are expressed in mature pollen grains and tubes (Fig. 1, A and B, and fig. S1, A to I). Green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein analysis demonstrated that both BUPS1 and BUPS2 proteins are expressed in pollen grains and pollen tubes and localize at the apical plasma membrane of pollen tubes (Fig. 1, C and D, and fig. S1, J and K).

Fig. 1. Pollen-expressed BUPS1 and BUPS2 control pollen tube integrity.

(A and B) Expression pattern of BUPS1 and BUPS2, as shown by BUPS1p::GUS (A) and BUPS2p::GUS (B) in flowers. (C and D) Localization of BUPS1-GFP (C) and BUPS2-GFP (D) in pollen tubes. Graphs show fluorescence intensity (FI) 10 µm from the apex (denoted by white dashed line); the x-axis values represent the distance from the first dash at the left (in pixels) along the dashed line. Arrowheads indicate the fluorescence enrichment on the plasma membrane. (E) Mutant alleles of bups1 and bups2. Double backslash (\\) denotes localization of single-guide RNAs; single backslash (\) denotes the mutation site; dashed lines indicate large chromosomal deletion. SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane domain. (F and G) Silique length (F) and number of seeds per silique (G) of the wild type (WT) and various mutants. Data are means ± SD (n = 20 siliques); **P < 0.005, ***P < 0.001 (Student t test). (H) Transmission efficiency of bups mutants. ***P < 0.001 (χ2 test); n.s., not significant. (I) Pollen germination assay of bups1 and bups1 bups2 pollen grains. Pictures were collected after 7 hours of incubation. Arrows indicate the position of rupture. (J) Aniline Blue staining of WT, bups1, and bups1 bups2 pollen tubes in wild-type pistils after 20 hours of pollination. Arrows show the areas where the bups pollen tubes made contact. Scale bars, 5 mm [(A), (B)], 10 µm [(C), (D)], 50 µm (I), 500 µm (J).

To study the role of BUPS1/2, we generated loss-of-function single and double mutants by CRISPR/Cas9 (20). We identified five homozygous single loss-of-function mutants for either BUPS1 or BUPS2 (Fig. 1E and fig. S2, A and B) and four homozygous double mutants. None of these mutants exhibited defects in vegetative growth, although mature bups1 and bups1 bups2 mutant plants produced shorter than normal siliques (Fig. 1F and fig. S3, A to D). Although the number of seeds per silique in bups2 was comparable to that of the wild type, bups1 and bups1 bups2 plants produced almost no seeds (Fig. 1G). Only male transmission of bups1 or bups1 bups2 was defective (Fig. 1H, table S1, and fig. S4, A to D). Two T-DNA–induced mutants, bups1-T-1 and bups1-T-2 (fig. S5, A and B), also showed suppressed male transmission (table S2A and fig. S6). We conclude that the bups1 and bups1 bups2 fertility defects we observed are male-specific.

The bups1 and bups1 bups2 pollen grains were morphologically normal (fig. S7, A to D) and initiated germination normally. Whereas only 7.3% of wild-type pollen tubes ruptured at an average length of 268 ± 73 µm, 98% of bups1 pollen tubes ruptured precociously at 89.0 ± 45.5 µm, and bups1 bups2 tubes burst immediately upon germination (Fig. 1I, table S3, and movie S1). On the stigma of wild-type plants, both bups1 and bups1 bups2 pollen germinated normally. Most mutant tubes did not penetrate beyond the style; some burst in the style or at the top of the ovary locule (Fig. 1J and fig. S8, A to C). The bups1-T-1 and bups1-T-2 mutants showed similarly severe pollen tube growth defects (fig. S5C), which were rescued by BUPS1p::BUPS1-GFP (fig. S5, D to F, and table S2B). Taken together, these results indicate that BUPS1, with some minor contribution from BUPS2, maintains pollen tube growth by prohibiting precocious pollen tube rupture and sperm cell discharge. The precocious pollen tube bursting phenotype in bups mutants reminded us of the famous Chinese myth “Journey to the West,” where the Monkey King was once trapped under a mountain and sealed by a Buddha’s Paper Seal for 500 years before a monk heading to the West removed the seal to release him. The two receptors are therefore named BUPSs.

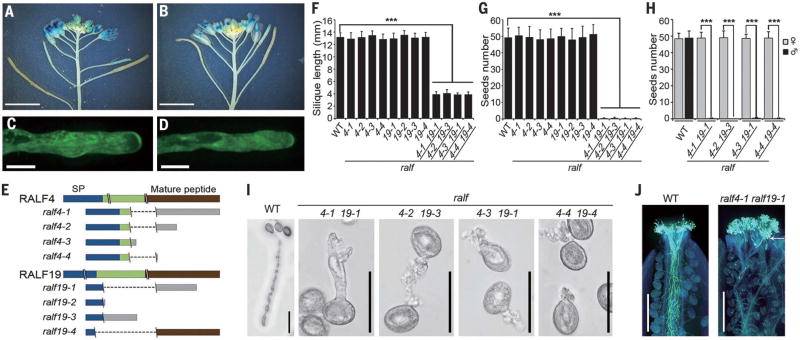

The 5-kDa cysteine-rich peptides known as RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTORs (RALFs) are ligands for receptors of the CrRLK1L family (21–24). Two of these peptides, RALF4 and RALF19, inhibit pollen germination in vitro (25). We found that their genes (At1g28270 and At2g33775, respectively) were expressed in the mature pollen grains and tubes (Fig. 2, A and B, and fig. S1, L to R) and their encoded proteins were present in pollen grains and tubes (Fig. 2, C and D and fig. S1, S and T). We generated four homozygous single mutants for each of the two genes and four homozygous double mutants (Fig. 2E and fig. S2, C and D). None of them exhibited defects in vegetative growth, but, like bups1 bups2 double mutants, ralf4 ralf19 double mutants showed male-specific defects (Fig. 2H and fig. S4, E and F), producing abnormally short siliques and were male sterile (Fig. 2, F and G, and fig. S3, E and F). Although ralf4 ralf19 pollen grains were normal in morphology (fig. S7, E and F) and germinated normally in vitro, their pollen tubes burst prematurely (Fig. 2I, table S4, and movie S2). On the stigma, these pollen grains germinated, but mutant pollen tubes soon became arrested, some rupturing on the stigmatic surface (Fig. 2J and fig. S8D). Thus, the ralf4 ralf19 pollen tube growth phenotype resembles that of bups1 bups2 mutants.

Fig. 2. RALF4 and RALF19 are pollen tube–expressed and, like BUPS1/2, are required for pollen tube integrity.

(A and B) Expression pattern of RALF4p::GUS (A) and RALF19p::GUS (B) in flowers. (C and D) Localization of RALF4-GFP (C) and RALF19-GFP (D) in pollen tubes. (E) Mutant alleles of ralf4 and ralf19. Denotations are as described in Fig. 1E. (F and G) Silique length (G) and number of seeds per silique (F) of WT and various mutants. Data are means ± SD (n = 20 siliques); ***P < 0.001 (Student t test). (H) Seed number analysis in reciprocal crosses between WT and homozygous double mutants. ***P < 0.001 (Student t test). (I) Pollen germination assay of ralf4 ralf19 pollen grains. Pictures were collected after 7 hours incubation. (J) Aniline Blue staining of WT and ralf4 ralf19 pollen tubes in WT pistils at 20 hours after pollination. Arrow shows the area where the mutant pollen tubes made contact. Scale bars, 5 mm [(A), (B)], 10 µm [(C), (D)], 50 µm (I), 500 µm (J).

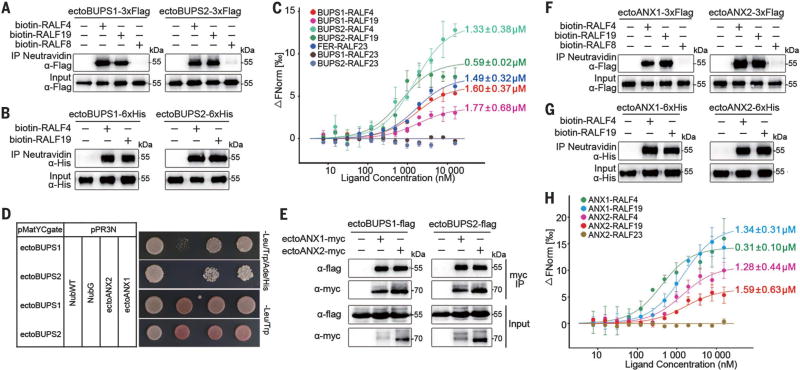

Given the similar phenotypes induced by mutations in RALF4/19 peptides and BUPS1/2 receptors, we hypothesized that they represent functional pairs and therefore looked for physical interactions. Flag-tagged ectodomains of BUPS1 and BUPS2 expressed in tobacco could be pulled down by biotinylated RALF4 and RALF19, but not by pollen-expressed RALF8 (At1g61563) (Fig. 3A). Pull-down of RALF4/19 by insect cell–expressed BUPS1/2 ectodomains also confirmed the direct interaction (Fig. 3B). Microscale thermophoresis (MST) analyses showed that RALF4 and RALF19 both interact with BUPS1 and BUPS2, with affinities comparable to that reported for RALF23-FER interaction (24), all with dissociation constant (Kd) values in the low micromolar range (Fig. 3C). In contrast, RALF23 did not bind BUPS1 or BUPS2 (Fig. 3C), indicating that BUPSs selectively bind to the pollen RALFs. Interestingly, we detected physical interaction between the ectodomains of BUPS1/2 and of the other two pollen tube–expressed CrRLK1L receptors, ANX1/2, in a yeast two-hybrid assay (Fig. 3D), which also showed interactions between their cytoplasmic domains (fig. S9), and by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 3E). RALF4/19 also interacted with ANX1/2 (Fig. 3, F and G) with comparable affinities (26) (Fig. 3H). Male sterility induced by loss of ANXs alone (2, 3) or loss of BUPSs alone (Fig. 1) already had implied that these receptors might function in a complex; results from our interactive studies are also consistent with potential heteromer formation between these proteins for their biological function. Whether and how these RALFs affect receptor complex formation will be important to examine in the future.

Fig. 3. BUPS1/2, ANX1/2, and RALF4/19 interact with each other.

(A) Pull-down assay between Flag-tagged ectodomains of BUPS1/2 (purified from tobacco leaves) and biotinylated RALF4/19. (B) Pull-down assay between insect cell–expressed His-tagged ectodomains of BUPS1/2 and biotinylated RALF4/19. (C) Binding affinity between BUPS1/2 and RALF4/19 by MST analysis; Kd values are as indicated. The published RALF23-FER Kd value is 0.31 µM (24). ΔFNorm, change in fluorescence. (D) Dual-membrane yeast two-hybrid assays of BUPS1/2 and ANX1/2. (E) Interaction of BUPS1/2 and ANX1/2 through their ectodomains, as assessed by coimmunoprecipitation assay. The ectodomains of BUPS1/2 and ANX1/2 were coexpressed in tobacco leaf cells. (F and G) ANX1/2-Flag (F) and ANX1/2-His (G) interact with biotinylated RALF4/19 by pull-down assays. (H) MST analysis of the binding affinity between ANX1/2 ectodomains and RALF4/19. Error bars in (C) and (H) are SEM of two independent experiments.

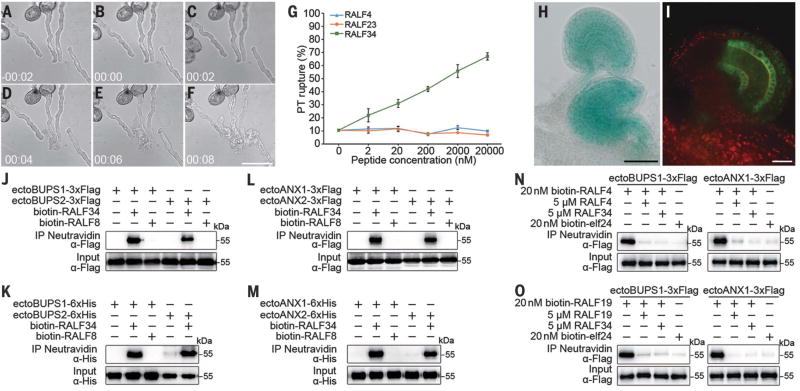

Next, we asked how pollen tube integrity is compromised to allow sperm cell release as a pollen tube penetrates the female gametophyte. We hypothesized that autocrine signaling of RALF4/19 at the receptor complex BUPS1/2-ANX1/2 in a growing pollen tube is inactivated upon pollen tube arrival by signals derived from the ovule. To test this idea, we synthesized RALF peptides that accumulate in immature or mature ovules (i.e., RALF5, 14, 18, 24, 28, 29, 31, 33, and 34) but not in dry pollen or semi–in vivo grown pollen tubes (fig. S1L) and applied them to pollen tubes in vitro. In comparison to pollen-specific RALF4 and immune response–related RALF23, a low concentration of RALF34 (At5g67070), 2 nM, was sufficient to induce rupture of 23% of pollen tubes as early as within 2 min of treatment, whereas rupture reached almost 70% in response to 20 µM RALF34 (Fig. 4, A to G, and movie S3). The RALF34 gene was prominently expressed in mature ovules, with evident expression around the micropylar/synergid cell region (Fig. 4H and fig. S10, A and B). Accumulation of RALF34-GFP could be observed in ovules before fertilization, albeit mainly in the inner integument (Fig. 4I and fig. S10C). Similar to RALF4/19, biotinylated RALF34 peptide bound to the ectodomains of BUPS1/2 (Fig. 4, J and K) and ANX1/2 (Fig. 4, L and M). Moreover, RALF34 was able to compete with RALF4/19 for interaction with BUPS1 or ANX1 (Fig. 4, N and O). Thus, RALF34 may serve as an ovule-derived paracrine signal to replace the autocrine signals (RALF4/19) required for cell integrity maintenance, thereby enabling the pollen tube to respond to the ovular environment generated by FER (19), resulting in rupture and sperm cell discharge for fertilization (fig. S11). Loss-of-function ralf34-1 plants are not notably compromised in reproduction, producing full siliques of seeds (fig. S10, D to F). It is likely that the presence of multiple female tissue–expressed RALFs (fig. S1L) had masked the impact of loss of RALF34. Isolation of viable higher-order mutants in these peptides would help to elucidate their contribution to pollen tube reception.

Fig. 4. RALF34 triggers pollen tube burst and interacts with and competes for the ANX-BUPS receptor complex.

(A to F) Time-course imaging of pollen tube discharge induced by RALF34 treatment; 20 µM peptide was used to test the effect on growing wild-type pollen tubes. The pollen tube discharge occurs less than 10 s after RALF34 treatment. (G) Quantitative analysis of pollen tube rupture treated with different concentrations of RALF4, RALF23, and RALF34. Data are means ± SD (n = 230 pollen tubes of each treatment for two independent experiments). (H) RALF34p::GUS expressed predominantly in mature ovules. (I) RALF34-GFP protein expressed in ovules. (J to M) Pull-down assays between biotinylated RALF8/34 and Flag- or His-tagged ectodomains of BUPS1/2 [(J) and (K)] or between biotinylated RALF8/34 and Flag- or His-tagged ectodomains of ANX1/2 [(L) and (M)]. (N and O) RALF34 peptide outcompetes biotinylated RALF4/19 interaction with Flag-tagged ectodomain of BUPS1 or ANX1. Scale bars, 50 µm [(A) to (F), (H)], 20 µm (I).

Fertilization in flowering plants depends on precise spatiotemporal regulation of two antagonistic processes: pollen tube growth and disintegration (1–6, 27, 28). BUPSs and ANXs form heteromers to mediate both pollen tube growth and rupture, suggesting cross-regulation of antagonistic processes. Signaling through these common and related receptors, the related ligands, pollen tube–produced RALF4/19 and ovule-produced RALF34, apparently serve as distinct spatiotemporal triggers to mediate these two opposite outputs, thereby supporting tube growth and triggering its disintegration. Together, a suite of peptide ligands provides autocrine signaling to support growth during the long pollen tube journey to the ovule, where through a ligand exchange they act by paracrine signaling to disarm the pollen tube apparatus, placing developmental events in correct sequence to ensure reproductive success.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sodmergen and H. Ren for technical help in pollen germination assay. Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China grants 31620103903, 31621001, and 31370344; the 111 Project of the China Ministry of Education; NSF grants IOS1147165, 1146941, and 1645854; Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de Sao Paulo grant 2014/14487-1; Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Mexico) grant 329718/234690; and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico fellowship CNPq-201213/2014-1 (T.B.). The Qu laboratory is supported by the Peking-Tsinghua Joint Center for Life Sciences, the Dresselhaus lab by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Collaborative Research Center SFB924 consortium, and the Dong lab by National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant R01GM109080. We also thank the Research Coordination Network on Integrative Pollen Biology (NSF grant MCB0955910) for activities that forged this collaboration. Supplement contains additional data.

Footnotes

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Zhang J, et al. Nat. Plants. 2017;3:17079. doi: 10.1038/nplants.2017.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyazaki S, et al. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:1327–1331. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boisson-Dernier A, et al. Development. 2009;136:3279–3288. doi: 10.1242/dev.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T, et al. Nature. 2016;531:241–244. doi: 10.1038/nature16975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takeuchi H, Higashiyama T. Nature. 2016;531:245–248. doi: 10.1038/nature17413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, et al. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:993–998. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dresselhaus T, Sprunck S, Wessel GM. Curr. Biol. 2016;26:R125–R139. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qu L-J, Li L, Lan Z, Dresselhaus T. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:5139–5150. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bircheneder S, Dresselhaus T. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:4849–4861. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Q, Dresselhaus T, Gu H, Qu L-J. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2015;57:518–521. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hématy K, et al. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:922–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo H, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:7648–7653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812346106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan Q, Kita D, Li C, Cheung AY, Wu H-M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:17821–17826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005366107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bai L, et al. Plant Cell. 2014;26:1497–1511. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.124586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L, et al. PLOS Genet. 2016;12:e1006085. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Wu H-M, Cheung AY. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2379–2392. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pu CX, et al. Plant Cell. 2017;29:70–89. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escobar-Restrepo JM, et al. Science. 2007;317:656–660. doi: 10.1126/science.1143562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duan Q, et al. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3129. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ZP, et al. Genome Biol. 2015;16:144. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0715-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haruta M, Sabat G, Stecker K, Minkoff BB, Sussman MR. Science. 2014;343:408–411. doi: 10.1126/science.1244454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy E, De Smet I. Trends Plant Sci. 2014;19:664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nissen KS, Willats WGT, Malinovsky FG. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:516–527. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stegmann M, et al. Science. 2017;355:287–289. doi: 10.1126/science.aal2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morato do Canto A, et al. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014;75:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin G, et al. Genes Dev. 2017;31:927–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.297580.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang W, Kelley D, Ezcurra I, Cotter R, McCormick S. Plant J. 2004;39:343–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang W, Ezcurra I, Muschietti J, McCormick S. Plant Cell. 2002;14:2277–2287. doi: 10.1105/tpc.003103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.