Abstract

In Lewy body (LB) diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), without and with dementia (PDD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients with LB co-pathology1, α-synuclein (α-Syn) aggregates in neurons as LBs and Lewy neurites (LNs)2, while in multiple system atrophy (MSA), α-Syn mainly accumulates in oligodendrocytes as glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs)3. Here, we report that pathological α-Syn in GCIs and LBs (GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn) are conformationally and biologically distinct. GCI-α-Syn forms more compact structures and is ~1,000-fold more potent than LB-α-Syn in seeding α-Syn aggregation, consistent with the highly aggressive nature of MSA. Surprisingly, GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn show no cell type preference in seeding α-Syn pathology, raising the question of why they demonstrate different cell type distributions in LB disease versus MSA. Strikingly, we found that oligodendrocytes but not neurons transform misfolded α-Syn into a GCI-like strain, highlighting that distinct α-Syn strains are generated by different intracellular milieus. Moreover, GCI-α-Syn maintains its high seeding activity when propagated in neurons. Thus, α-Syn strains are determined by both misfolded seeds and intracellular environments.

Main Text

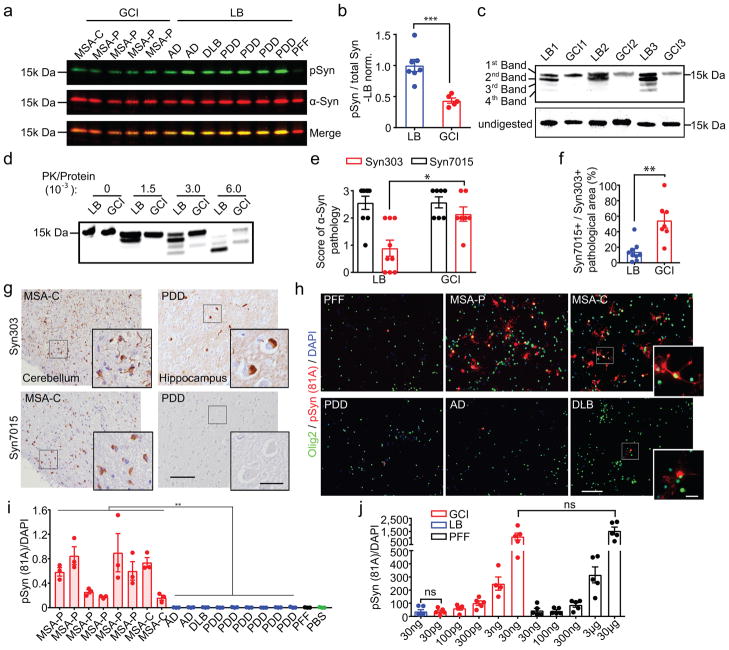

The diverse nature of α-synucleinopathies suggests that they may be caused by distinct α-Syn strains4–8. To investigate whether GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn represent two distinct strains, sarkosyl-insoluble α-Syn was isolated from MSA, which contains two subtypes [the parkinsonian subtype (MSA-P) and the cerebellar subtype (MSA-C) 9,10], and LB disease brains (Extended Data Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1&2). Firstly, we evaluated the extent of Ser129 phosphorylation (pS129), a hallmark of pathological α-Syn11,12, on GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn and found much less pS129 on GCI-α-Syn than LB-α-Syn (Fig. 1a–b). Secondly, conformational differences between GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn were analyzed using proteinase K (PK) digestion. Interestingly, PK digestion shows predominantly undigested α-Syn for GCI-α-Syn (1st band in Fig. 1c), while LB-α-Syn was cleaved into smaller fragments (2nd– 4th bands in Fig. 1c). The relative resistance of GCI-α-Syn to PK digestion was further confirmed using increasing concentrations of PK (Fig. 1d), indicating that GCI-α-Syn might form a more compact structure than LB-α-Syn. Epitope mapping showed that the 2nd band after PK digestion was mainly truncated at the N-terminus, while the 3rd and 4th bands were mainly truncated at the C-terminus (Extended Data Fig. 1b–c). GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn also produced distinct banding patterns when digested with trypsin or thermolysin, further demonstrating their different conformations (Extended Data Fig. 1d–g).

Fig. 1. GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn represent two distinct strains.

(a) GCI and LB immunoblotted with antibodies against total or pS129 α-Syn. (b) Quantification of pS129 versus total α-Syn in (a) (GCI, n=5; LB, n=7 cases). (c) PK-digested LB-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn from 6 cases immunoblotted with anti-α-Syn MAb (Syn211). (d) GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn incubated with increasing concentrations of PK and immunoblotted with Syn211 (repeat 3 times). (e) Semi-quantitative scores (0–3) to quantify α-Syn pathology revealed by Syn303 or Syn7015 immunohistochemistry (IHC) in adjacent MSA or LB disease brain sections. (LB, n=9; GCI, n=7 cases) (statistics: Mann Whitney U test). (f) Quantification of area occupied by Syn7015+ versus Syn303+ α-Syn pathology for experiments in (e). (LB, n=9, GCI, n=7 cases). (g) Representative photomicrographs for experiments in (e) (repeat with 7 cases). (h) Primary oligodendrocytes expressing α-Syn-mCherry incubated with 13 ng GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFFs were stained with 81A (pS129 α-Syn) and anti-olig2 (repeat 4 times). (i) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn induced by GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn and PFF in oligodendrocytes expressing α-Syn (GCI, n=8; LB, n=9 different preparations). (statistics: two tail, unpaired t-test using the mean value of each case). (j) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn induced by various amounts of PFFs, GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn in oligodendrocytes expressing α-Syn (LB, n=6; GCI 3ng, n=4; other groups, n=5 biological replicates) (statistics: adjusted with Bonferroni correction). Results shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant). Scale bars: 100 μm [(g) and (h)], 25 μm [(g) inset], 10 μm [(h) inset]. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

To confirm that GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn have different conformations, we immunostained diseased brain sections with a monoclonal antibody (MAb), Syn7015, selective for a synthetic α-Syn strain13. At low concentrations, Syn7015 preferentially recognized GCIs over LBs, whereas another MAb Syn303 that detects pathological α-Syn13,14, immunostained GCIs and LBs equally well (Extended Data Fig. 2a–b). Semi-quantitative analyses of LBs and GCIs 15,16 stained by Syn7015 or Syn303 on adjacent sections showed that Syn7015 preferentially recognized GCIs over LBs (Fig. 1e), which was also supported by the ratio of total area occupied by Syn7015+ over Syn303+ pathology (Fig. 1f–g, Extended Data Fig. 2c) further demonstrating conformational differences between GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn.

To determine whether structural differences between GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn influence their seeding activities, we treated primary oligodendrocytes expressing α-Syn with an equal amount of GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or α-Syn preformed fibrils (PFFs)17. Remarkably, GCI-α-Syn is much more potent than LB-α-Syn and PFFs in seeding α-Syn aggregation in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 1h–i, Extended Data Fig. 3a–b). Specifically, GCI-α-Syn is ~1,000-fold more potent than LB-α-Syn and α-Syn PFFs (Fig. 1j) since 30 ng LB-α-Syn induced a similar amount of pathology as 30 pg GCI-α-Syn, and 30 μg α-Syn PFFs were comparable to 30 ng GCI-α-Syn. Purity of the oligodendrocyte cultures and the presence of α-Syn pathology in oligodendrocytes were confirmed by immunofluorescence staining (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f).

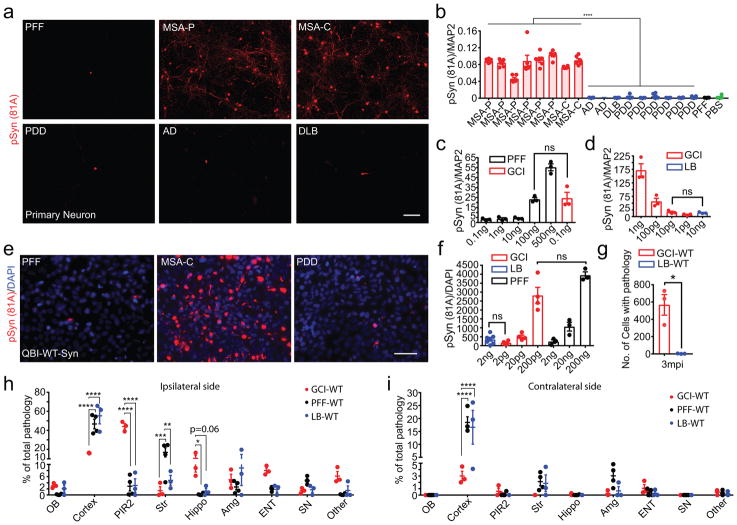

Since the high potency of GCI-α-Syn in inducing oligodendrocyte pathology is consistent with its oligodendrocytes distribution in MSA, we hypothesized that the properties of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn dictate their differential cell type distribution in patients (hypothesis 1 in Extended Data Fig. 3g), and speculated that LB-α-Syn are more potent than GCI-α-Syn in inducing neuronal pathology. Surprisingly, primary neurons treated with GCI-α-Syn developed much more α-Syn inclusions than those treated with LB-α-Syn or α-Syn PFFs (Fig. 2a–b, Extended Data Fig. 4a–b) and GCI-α-Syn also was ~1,000-fold more potent than LB-α-Syn or PFFs in inducing neuronal α-Syn pathology (Fig. 2c–d). Furthermore, using a QBI-293 cell line expressing human α-Syn (QBI-WT-Syn cells) 18, we confirmed that GCI-α-Syn is ~1,000 fold more potent than LB-α-Syn and PFFs (Fig. 2e–f, Extended Data Fig. 4c–e). To rule out possible contributions of contaminating proteins, GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn were further purified by immunoprecipitation (IP). IP purified GCI-α-Syn maintained its dramatically higher seeding ability compared to LB-α-Syn (Extended Data Fig. 4f). Furthermore, the addition of PFFs to IP-depleted GCI-α-Syn preparations did not increase the seeding ability of PFFs (Extended Data Fig. 4g–h).

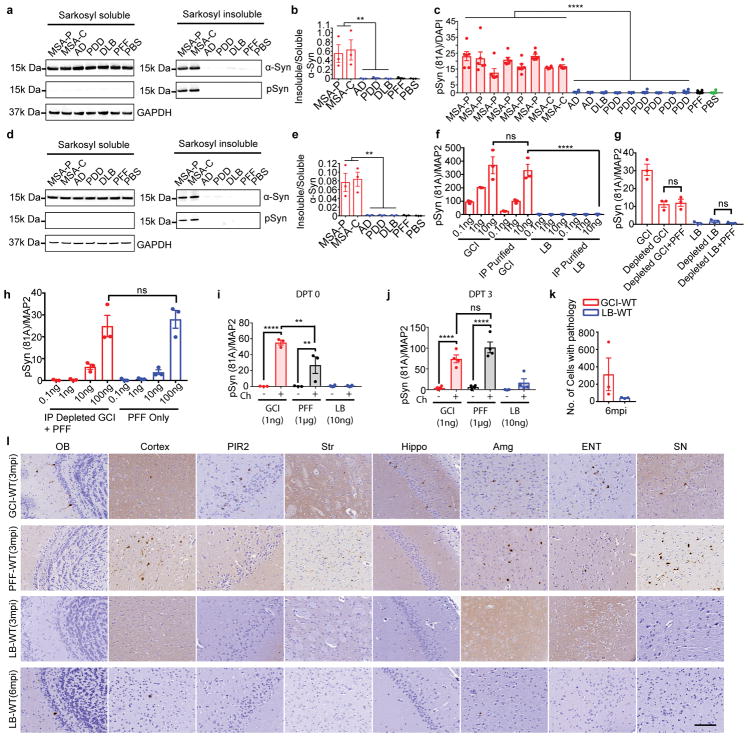

Fig. 2. The seeding properties of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn do not show any cell type preference.

(a) pS129 α-Syn induced by 1 ng GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFFs in primary neurons (repeat 7 times). (b) Quantification of α-Syn pathology for experiments in (a) (GCI, n=8, LB, n=9 different preparations) (statistics: two tail, unpaired t-test using the mean value of each case.). (c–d) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn induced by various concentrations of PFFs, GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn in neurons (n=3 biological replicates) (statistics: adjusted with Bonferroni correction). (e) pS129 α-Syn induced by 2 ng GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFFs in QBI-WT-Syn (repeat 7 times). (f) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn induced by various concentration of PFFs, GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn Cells. (LB, n=7; GCI, n=4; PFF, n=3 biological replicates) (statistics: adjusted with Bonferroni correction). (g) Quantification of the number of cells with α-Syn pathology in WT mice inoculated with 50 ng GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn at 3 mpi (n=3 mice). (h–i) Quantification of the distribution of α-Syn pathology seeded by GCI-α-Syn (GCI-WT, n=3 mice) or PFFs (PFF-WT, n=4 mice) at 3 mpi and LB-α-Syn (LB-WT, n=3 mice) at 6mpi. OB: olfactory bulb; Cortex: cortex except pyramidal layer of piriform area (PIR2) and entorhinal cortex (ENT); Str: striatum; Hippo: hippocampus; SN: substantia nigra. Results shown as mean ± SEM. Statistics shown in (h–i) are two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD. Scale bars: 100 μm (a), 50 μm (e). See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

Since GCI-α-Syn is more resistant to PK digestion (Fig. 1c–d), we asked whether the high potency of GCI-α-Syn is due to its resistance to degradation. Previously we showed that exogenously added misfolded α-Syn accumulate in lysosomes and that treating the cells with chloroquine (lysosomal inhibitor) could increase the amount of α-Syn pathology induced19. To test this hypothesis, primary neurons seeded with GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFFs were treated with chloroquine. Interestingly, chloroquine treatment similarly increased the amount of pathology induced by GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn and PFFs (Extended Data Fig. 4i–j), suggesting that the high potency of GCI-α-Syn is unlikely due to its resistance to lysosomal proteolysis.

The dramatically different seeding abilities of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn in vitro prompted us to test their properties in vivo. Equivalent amounts of GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn were injected into the striatum of WT mice20. At 3 months post-injection (mpi), only GCI-α-Syn injected WT (GCI-WT) mice developed abundant neuronal inclusions (Fig. 2g). At 6 mpi, although the amount of α-Syn pathology in GCI-WT mice declined dramatically, only limited number of neurons developed α-Syn pathology in LB-WT mice (Extended Data Fig. 4k). Therefore, GCI-α-Syn more potently induces neuronal pathology in vivo, which also argues against cell-type specific seeding by GCI-α-Syn. Furthermore, no oligodendroglia pathology was detected in GCI-WT mice, which further argues against the hypothesis that GCI-α-Syn properties could dictate its oligodendrocyte distribution. On the other hand, the high potency of GCI-α-Syn likely contributes to the aggressive nature of MSA.

Misfolded α-Syn was shown to spread through the neuroanatomical connectome, but how different α-Syn strain properties affect this spreading process is unclear. We compared the transmission pattern of α-Syn pathology in WT mice injected with GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFFs. Interestingly, GCI-α-Syn spread more efficiently to entorhinal cortex, hippocampus and piriform cortex, but less efficiently to other cortical regions such as motor cortex, compared to PFFs and LB-α-Syn, while α-Syn PFFs induced relatively more pathology in the striatum and substantia nigra, but less in olfactory bulb compared with LB-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn (Fig. 2h–i, Extended Data Fig. 4l and 5a–b). Therefore, our data demonstrate that different α-Syn strains dramatically modulate their transmission patterns in the nervous system.

The observation that GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn seeding properties do not show any cell type preference raises the question of why they demonstrate distinct cell type distribution in diseased brains. Since our data argue against the hypothesis that strain properties determine cell type distributions (hypothesis 1 in Extended Data Fig. 3g), we proposed an alternative hypothesis that different cellular environments of neurons and oligodendrocytes promote the formation of distinct α-Syn strains (hypothesis 2 in Extended Data Fig. 3g). According to this hypothesis, injection of LB-α-Syn into mice expressing α-Syn in oligodendrocytes should convert it into a GCI-like strain. To test this hypothesis and to eliminate confounds arising from neuronal pathology, we crossed CNP-α-Syn transgenic (TG) mice (M2 line)21, with α-Syn knockout mice, generating a new mouse line expressing α-Syn only in oligodendrocytes (KOM2 mice) (Extended Data Fig. 6a&b).

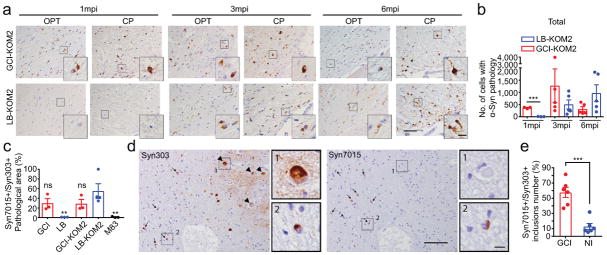

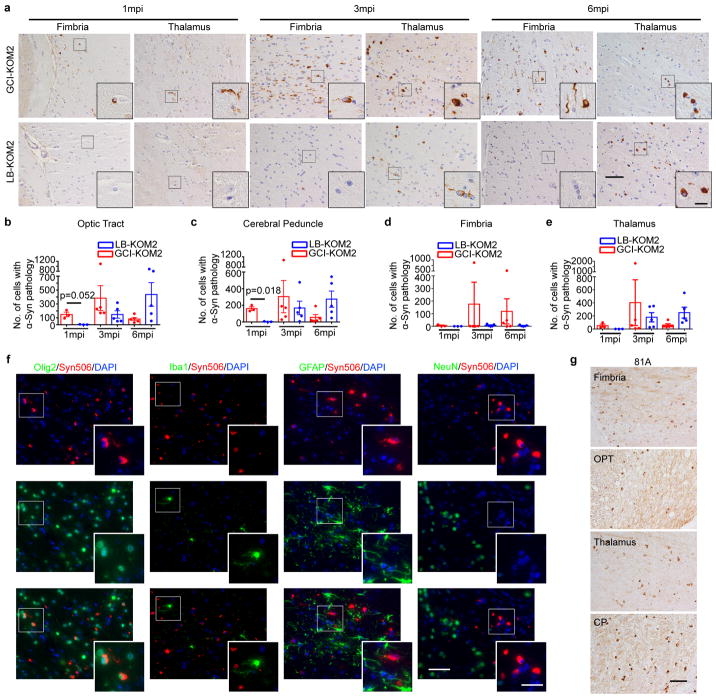

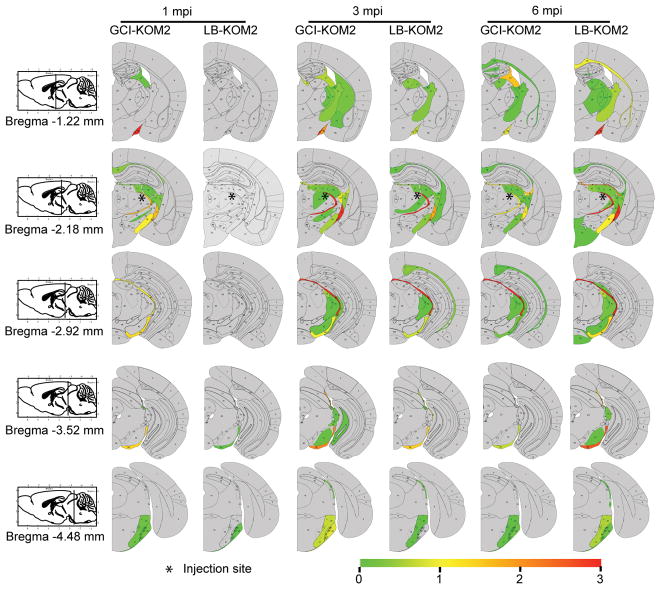

KOM2 mice were unilaterally injected with GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn into the thalamus (GCI-KOM2 and LB-KOM2 mice). At 1 mpi, although α-Syn inclusions appeared in the thalamus and fimbria of GCI-KOM2 mice, more abundant pathology was observed in the optic tract and cerebral peduncle, i.e. sites distant from the injection site but highly enriched with oligodendrocytes, suggesting that α-Syn pathology spreads between oligodendrocytes. In contrast, few oligodendrocytes developed pathology in LB-KOM2 mice, demonstrating that GCI-α-Syn is more potent than LB-α-Syn. However, at 3 mpi, as the burden of pathology in GCI-KOM2 mice peaked, LB-KOM2 mice began to show significant oligodendrocyte pathology. At 6 mpi, while the pathology in GCI-KOM2 mice declined precipitously, LB-KOM2 mice showed even more inclusions, reaching levels comparable to GCI-KOM2 mice at 3 mpi (Fig. 3a–b, Extended Data Fig. 7a–e). The presence of α-Syn pathology in oligodendrocytes and the phosphorylation of S129 were confirmed by immunostaining (Extended Data Fig. 7f–g). Mapping of α-Syn pathology in LB-KOM2 and GCI-KOM2 mice revealed a similar pattern (Extended Data Fig. 8). This delayed induction of α-Syn pathology in LB-KOM2 mice supports our hypothesis that LB-α-Syn is less potent than GCI-α-Syn, but once initiated, the subsequent propagation within oligodendrocytes results in the formation of a GCI-α-Syn-like strain.

Fig. 3. Oligodendrocyte environment generate the GCI-α-Syn strain.

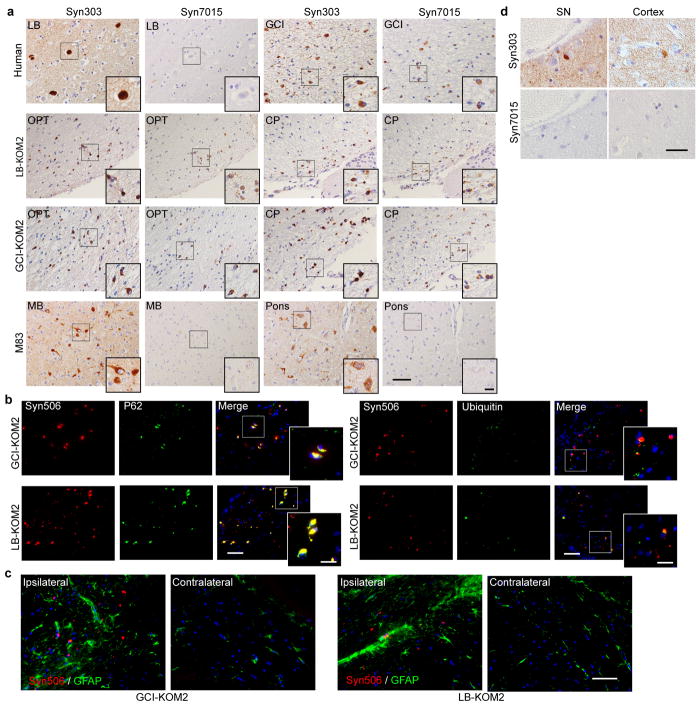

(a) Syn506+ α-Syn aggregates seeded by 18.75 ng GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn in KOM2 mice. OPT: optic tract; CP: cerebral peduncle (repeat 3 times). (b) Quantification of the number of oligodendrocytes with α-Syn pathology in injected KOM2 mice (1 mpi, n=3; 3 and 6 mpi, n=5 mice). (Statisitcs: adjusted with Bonferroni correction.) (c) Quantification of the ratio of area occupied by Syn7015+ versus Syn303+ α-Syn pathology in adjacent sections of MSA, LB disease, injected KOM2 or M83 TG mouse brains (GCI, n=3 cases; LB n=3 cases; GCI-KOM2, LB-KOM2 and M83 n=4 mice). (Statisitcs: one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc test comparing each group with LB-KOM2.) (d) Adjacent sections of the medulla from an MSA case stained with Syn303 and Syn7015 (repeat with 4 cases). Arrows: GCIs; arrowheads: NIs. (e) Quantification of the ratio of Syn7015+ versus Syn303+ GCIs and NIs on adjacent sections of MSA brains (n=6 cases). Results shown as mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 50 μm (a); 12.5 μm [(a) insets]; 100 μm (d); 10 μm [(d) insets]. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

Moreover, while LBs in PD brains were not detected by Syn7015, the oligodendrocyte α-Syn pathology induced by these LB-α-Syn in KOM2 mice were Syn7015 positive (Fig. 3c, Extended Data Fig. 9a), suggesting that LB-α-Syn-induced oligodendrocyte pathology acquired properties of the GCI-α-Syn strain. Furthermore, detailed characterization of oligodendrocyte pathologies induced by GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn showed that they were indistinguishable, including co-localization with p62, partial co-localization with ubiquitin and association with reactive astrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 9b–c). Thus, LB-α-Syn can induce oligodendrocyte pathologies in the KOM2 mice that adopt properties of the GCI-α-Syn strain.

Both α-Syn neuronal inclusions (NIs) and GCIs are present in MSA brains although NIs are uncommon. If oligodendrocyte environment generates the GCI-α-Syn strain, we hypothesized NIs in the MSA brains to resemble LBs in PD brains. To test this, adjacent sections of 6 MSA cases with NIs in the medulla or hippocampus were immunostained with Syn7015 and Syn303. Importantly, Syn7015 preferentially stained GCIs over NIs (Fig. 3d–e), demonstrating that MSA NIs are similar to PD LBs. Furthermore, Syn7015 also failed to detect NIs in other brain regions such as substantia nigra and cortex in additional MSA cases (Extended Data Fig. 9d), providing additional support for our hypothesis.

To further test our hypothesis, we injected human α-Syn PFFs into the pons and cerebellum of KOM2 mice (Fig. 4a–b). Then, the induced pathological α-Syn (PFF-KOM2-Syn) were recovered by sequential extraction. Strikingly, PFF-KOM2-Syn was much more potent than PFFs themselves in inducing α-Syn pathology (Fig. 4c, Extended Data Fig. 10a). In contrast, mixing PFFs with the sarkosyl-insoluble fraction from un-injected KOM2 mice only slightly increased the potency (PFF+KOM2) (Fig. 4c). A similar phenomenon was also observed when passaging LB-α-Syn in KOM2 mice (Fig. 4d). To test if this effect of cellular milieu is unique to oligodendrocytes, α-Syn PFFs were added to different cell types including oligodendrocytes, hippocampal and cortical neurons and QBI-WT-Syn cells. After the induction of α-Syn pathology, sarkosyl-insoluble α-Syn were prepared from these cells (Fig. 4e). PFF passaged through oligodendrocytes was more potent than those passaged through other cell types (Fig. 4f, Extended Data Fig. 10b–d). Taken together, these results clearly demonstrate that oligodendrocyte environment leads to the generation of GCI-α-Syn strain.

Fig. 4. Oligodendrocytes convert misfolded α-Syn to a GCI-α-Syn-like strain but neurons could not convert GCI-α-Syn to a LB-α-Syn like strain.

(a) Schematic diagram for passaging α-Syn PFFs in KOM2 mice. (b) α-Syn pathology in PFF injected KOM2 mice (repeat 3 times). (c) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by PFFs, passaged PFFs (PFF-KOM2-Syn) or PFFs combined with insoluble fraction from uninjected KOM2 mice (PFF+KOM2). (PFF-KOM2-Syn, n=6; PFF, n=3; PFF+KOM2, n=5 independent experiments) (d) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by equal amount LB-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn passaged in KOM2 mice (LB-KOM2). (LB, n=3; LB-KOM2, n=7 independent experiments) (e) Schematic diagram for passaging PFFs in various cells. (f) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by PFF passaged in cells. (PFF-Oligo-Syn, n=6; PFF-HipN-Syn and PFF-CtxN-Syn, n=4; PFF, n=3 independent experiments) (g) Schematic diagram for generating α-Syn PFFs in cell lysates. (h) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by PFFs generated in oligodendrocyte lysate (Oligo-PFF), cortex and hippocampus neuron lysate (CtxN-PFF and HipN-PFF), or with α-Syn monomer alone (PFF) (Oligo-PFF, n=6; CtxN-PFF, n=4; HipN-PFF, n=4; PFF, n=4 independent experiments). (i) Schematic diagram for passaging GCI-α-Syn in primary neurons. (j) Quantification of pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by α-Syn PFFs, GCI-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn passaged in primary neurons (GCI, n=3; GCI-N-P1, n=5; GCI-N-P2, n=4; GCI-N-P3, n=4; PFF, n=3 independent experiments). (k) PK digested LB-α-Syn, GCI-α-Syn and GCI-N-P1 to P3 were immunoblotted with anti-α-Syn antibody (repeat 3 times). (l) Quantification of insoluble pS129 α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by equal amount of GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn passaged in M83 mice (GCI, n=8; GCI-M-P1, n=6; LB, n=8 independent experiments). Results shown as mean ± SEM. Statistics shown in (c), (f), (h), (j) and (l) are one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc test comparing each group with PFF-KOM2-Syn in (c), PFF-Oligo-Syn in (f), Oligo-PFF in (h), GCI 200pg in (j) and GCI in (l). Scale bars: 1 mm (b); 50 μm [(b) middle inset]; 15 μm [(b) right inset]. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

To test whether the generation of GCI-α-Syn strain depends on cell structures or specific ‘factors’, we prepared cell lysates from primary oligodendrocytes and neurons, in which cell structures were disrupted but cell ‘factors’ were preserved. We incubated each lysate with equal amount of α-Syn monomer to generate α-Syn PFFs (Fig. 4g). Interestingly, PFFs generated in oligodendrocyte lysates were able to induce several-fold more pathology compared with PFFs generated in neuron lysates or with α-Syn monomers alone, supporting the hypothesis that the generation of GCI-α-Syn strain relies on specific ‘factors’ in oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4h).

Lastly, we asked whether the neuronal environment could convert GCI-α-Syn strain to LB-α-Syn strain. Primary mouse neurons were treated with GCI-α-Syn and the induced α-Syn pathology was enriched by sequential extraction (GCI-N-P1) (Fig. 4i). Using ELISAs that detect only human α-Syn or both human and mouse α-Syn, we estimated that majority (>99.7%) of pathological α-Syn in GCI-N-P1 was derived through recruitment of mouse α-Syn (Supplementary Table 3). Interestingly, GCI-N-P1 was as potent as GCI-α-Syn (Fig. 4j). Furthermore, GCI-α-Syn strain was repetitively passaged in neurons such that even after 3 rounds of passaging, GCI-N-P3 still maintained the profound activity of GCI-α-Syn strain (Fig. 4j, Extended Data Fig. 10e–g). PK digestion revealed that after passaging in neurons, the GCI-α-Syn conformation was maintained (Fig. 4k). Furthermore, when both GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn were passaged in M83 mice expressing mutant human (A53T) α-Syn22, their different seeding properties were maintained (Fig. 4l). Thus, we conclude that the GCI-α-Syn strain can be maintained in a neuronal milieu. Combining with the observation that NIs in MSA are similar to LB-α-Syn, our data suggest that GCI-α-Syn rarely transmitted from oligodendrocytes to neurons in MSA brains, although we cannot exclude the possibility that GCI-α-Syn transmits to neurons, but those neurons died.

Since LB-α-Syn could induce α-Syn pathology in oligodendrocytes expressing α-Syn in vitro and in vivo, the lack of GCIs in LB diseases is unlikely due to strain properties of LB-α-Syn, but might be due to the lack of α-Syn in oligodendrocytes23. The source of α-Syn in oligodendrocytes in MSA is still unclear. Two hypotheses has been proposed: 1) oligodendrocytes pathologically overexpress α-Syn in MSA24; or 2) oligodendrocytes take up α-Syn from neurons25. Interestingly, GCI-α-Syn also could not induce α-Syn pathology in oligodendrocytes cultured in medium with high concentration of α-Syn monomer (unpublished data), suggesting that internalization of exogenous α-Syn from the environment might be insufficient for GCI formation in oligodendrocytes.

Methods

Recombinant α-Syn Purification and In Vitro Fibrillization

Full length human and mouse α-Syn (1–140) proteins were expressed in BL21 (DE3) RIL cells and purified as previously described 26. Fibrillization was conducted by diluting recombinant α-syn to 5 mg/mL in sterile Dulbecco’s PBS (Cellgro, Mediatech Inc; pH adjusted to 7.0) followed by incubating this recombinant α-Syn at 37°C with constant agitation at 1,000 rpm for 7 days. Successful α-Syn fibrillization was verified by sedimentation test and Thioflavin T-binding assay as described27.

Preparation of Sarkosyl-Insoluble Fractions from Disease and Control Brains

All human brain tissues are from the CNDR brain bank28. Preparations of sarkosyl-insoluble fraction were performed as previously described 5 and outlined in Extended Data Fig. 1a. Briefly, brain regions with abundant α-Syn inclusions from MSA, PDD, DLB and AD patients were identified by post-mortem histological examination15. The AD brains were selected for the presence of abundant LBs in addition to plaques and tangles. Frozen brain tissues from the identified regions were homogenized in high-salt (HS) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 750 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA) with protease and protein phosphatase inhibitors, incubated on ice for 20 min and centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min. The pellets were then re-extracted with HS buffer, followed by sequential extractions with 1% Triton X-100-containing HS buffer and 1% Triton X-100-containing HS buffer with 30% sucrose. The pellets were then re-suspended and homogenized in 1% sarkosyl-containing HS buffer, rotated at 4°C overnight and centrifuged at 100,000g for 30 min. The resulting sarkosyl-insoluble pellets were washed once with Dulbecco’s PBS and re-suspended in Dulbecco’s PBS by brief sonication (QSonica Microson™ XL-2000; 20 pulses; setting 2; 0.5 sec/pulse). This suspension was termed the “sarkosyl insoluble fraction” containing pathological α-Syn and used for the cellular and in vivo assays described here. The amount of α-Syn, tau, Aβ 40 and 42 in the sarkosyl insoluble fractions were determined by sandwich ELISAs (see below) and the protein concentrations were examined by bicinchoninic acid assay. PK, trypsin and thermolysin digestion was performed as previously described5.

Sandwich ELISA

The concentrations of tau, Aβ 1-40 and Aβ 1-42 in the sarkosyl insoluble fraction of human brain extractions were measured using sandwich ELISA as previously described 29,30 with the following combinations of capture/reporting antibodies: Tau5/BT2+HT7 for tau, Ban50/BA27 for Aβ 1-40, Ban50/BC05 for Aβ 1-42.

To measure the concentration of α-Syn, 384 well NuncTM MaxisorpTM clear plates were coated with 100 ng (30 μL/well) Syn9027, a MAb to α-Syn, in Takeda buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed 4X with PBS containing 1% Tween 20 (PBS-T), and blocked using Block AceTM solution (90 μL/well) (AbD Serotec) overnight at 4°C. Then, the plates were incubated with brain lysates at 4°C overnight using recombinant α-Syn monomer as standards. The plates were then washed with PBS-T and a rabbit monoclonal anti-α-Syn antibody, MJF-R1 (1:1K, 30 μL/well) was added to each well and incubated at 4°C overnight. After washing, goat-anti-rabbit-IgG conjugated to horse radish peroxidase (Cell Signaling Technology, 1:15K, 30 μL/well) was added to the plates followed by incubation for 2 hr at room temperature. Following another wash, the plates were developed for 10–15 min using 1-Step Ultra TMB-ELISATM Substrate Solution (Fisher Scientific, 30 μL/well), the reaction was quenched using 10% phosphoric acid (30 μL/well) and plates were read at 450 nm on a Molecular DevicesTM Spectramax M5TM plate reader.

Cell Cultures

Primary mouse neurons were prepared from the hippocampus of embryonic day (E) 15–E17 CD1 mouse embryos as previously described27. α-Syn PFFs and sarkosyl insoluble α-Syn fractions were diluted in Dulbecco’s PBS (without Mg2+ or Ca2+) and sonicated (QSonica Microson™ XL-2000; 60 pulses; setting 1.5; 0.5 sec/pulse). Neurons were then treated with PBS, sonicated PFFs or the α-Syn sarkosyl insoluble fractions at 10 days in vitro (DIV) and harvested for immunocytochemistry at 14 days post treatment. To passage GCIs in primary neuron, 5 million neurons were plated per 10 cm dish, treated with 30 ng of sonicated GCI-α-Syn at 10 DIV and harvested at 24 DIV by sequential extraction with the same protocol as described for human brain, except that HS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 750 mM NaCl, 10 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA) containing 1% Triton-100 was used in the initial extraction. The amount of total α-Syn in the sarkosyl insoluble fractions was determined by sandwich ELISA with antibodies against both mouse and human α-Syn (Syn9027 and HuA) and the amount of human α-Syn was examined by sandwich ELISA using MJF-R1, which recognizes only human α-Syn, as the reporter antibody. PK digestion has been performed in the same way as above described for GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn. Treatment of primary neurons with chloroquine was performed as previous described19.

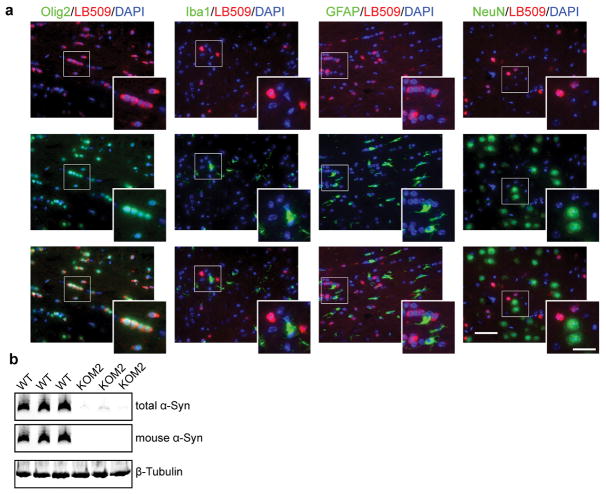

Primary oligodendrocytes were prepared from the cortices of neonatal Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories; Wilmington, MA) as previously described 31. Briefly, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPC) were purified from mixed glial culture by mechanical shaking. The purified OPC were plated on poly-L-lysine coated coverslips and infected with AAV8-α-Syn-mCherry or AAV8-α-Syn 3 days after plating. Then, differentiation was induced 3 days after infection by culturing OPC in the differentiation medium. Treatment with sonicated α-Syn PFF and sarkosyl insoluble fractions was performed 3 days after differentiation as described above. Treated oligodendrocytes were harvested for immunocytochemistry at 14 days post treatment. To evaluate the purity of the oligodendrocyte culture, three independent cultures were stained with various cell marker for astrocytes (GFAP), microglial (Iba1), neuron (NeuN) and oligodendrocytes (Olig2) at DIV3, DIV9 and DIV23. At least 3 different 20X images were randomly taken for each coverslip and at least 3 coverslips were analyzed for each time point for each cell marker.

To passage PFF in primary oligodendrocytes, 2 million OPC were plated in 10 cm dish, infected with AAV8-Syn to express human α-Syn, differentiated and treated with sonicated α-Syn PFFs as described above. Cells were harvested at 14 days after treatment by sequential extraction with the same protocol as described for primary mouse neurons. The amount of total α-Syn in the sarkosyl insoluble fractions was determined by sandwich ELISA with three different combinations of capture and reporting antibodies (Syn9027 + HuA, Syn9027 + MJF-R1 and HuA + Syn211).

The culture of QBI-WT-Syn cells and treatment with misfolded α-Syn were performed as previously described 18. To induce α-Syn pathology, in QBI-WT-Syn cells, 1 million QBI-WT-Syn cells were plated in 6 cm dish and treated with PFFs 2 days later. Cells were harvested at 3 days post treatment by sequential extraction with the same protocol as described for primary mouse neurons. The amount of total α-Syn in the sarkosyl insoluble fractions was determined by sandwich ELISA with three different combinations of capture and reporting antibodies (Syn9027 + HuA, Syn9027 + MJF-R1 and HuA + Syn211).

Primary hippocampus and cortical neurons of Sprague Dawley rats were generated from the Neuron Culture Service Center at University of Pennsylvania. To passage PFFs in primary rat neurons, 1.2 million hippocampus or cortical neurons were plated in 6 cm dish, infected with AAV8-α-Syn at 3 DIV to express human α-Syn and treated with PFFs at 6 DIV as described above. Cells were harvested at 14 days post treatment by sequential extraction with the same protocol as described for primary mouse neurons. The amount of total α-Syn in the sarkosyl insoluble fractions was determined by sandwich ELISA with three different combinations of capture and reporting antibodies (Syn9027 + HuA, Syn9027 + MJF-R1 and HuA + Syn211).

Stereotaxic Injection of Sarkosyl Insoluble Fraction of Pathological α-Syn and α-Syn PFFs

Sarkosyl insoluble fractions from diseased brains were diluted in sterile Dulbecco’s PBS to reach the same concentration of α-Syn in the samples and sonicated as described above. 2–3 months old C57BL6/C3H WT mice or 3–4 months old KOM2 mice were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (100 mg/kg), xylazine (10 mg/kg) and acepromazine (0.1 mg/kg). For WT type mice, 50 ng sarkosyl insoluble pathological α-Syn from two different MSA brains and one PDD brain or 6.25 μg mouse PFFs in 2.5 μL Dulbecco’s PBS was stereotaxically injected into the dorsal striatum (coordinates: +0.2 mm relative to Bregma, +2.0 mm from midline, +3.2 mm beneath the surface of skull) with 10 μL syringes (Hamilton, NV) at a rate of 0.4 μL per min. For KOM2 mice, 18.75 ng pathological α-Syn from three different MSA brains, two different PDD brains and one DLB brain in 2.5 μL Dulbecco’s PBS was stereotaxically injected into the thalamus, an area of relatively high oligodendrocyte α-Syn expression in these mice, (coordinates: −2.5 mm relative to Bregma, +2.0 mm from midline, +3.4 mm beneath the surface of skull) at a rate of 0.4 μL per min. Animals were then sacrificed at 1, 3 and 6 month post-injection.

To passage PFFs in KOM2 mice, 5 mg/mL PFFs were sonicated as described above and stereotaxically injected into the pons and cerebellum of the KOM2 mice (coordinates: −5.45 mm relative to Bregma, +1.1 mm from midline, +5 mm beneath the surface of skull for pons and +2.6 mm for cerebellum). 1 μL and 1.5 μL PFFs were injected into pons and cerebellum respectively at a rate of 0.1 μL per min. Mice were sacrificed 3–8 month post-injection and the pons and cerebellum were either processed for histological studies or frozen for sequential extraction. Sequential extractions were performed with the same protocol as described for human brain except that the two rounds of extraction of HS buffer were omitted and the extraction began with 1% Triton containing HS buffer. The amount of pathological α-Syn in the sarkosyl insoluble fraction was examined by sandwich ELISAs with two different combinations of capture and reporting antibodies (9027 + MJF-R1 and Syn211 + HuA). To passage LB-α-Syn in KOM2, 2.5μL LB-α-Syn at the concentration of 7.52–15.87 ng/μL were injected into the pons/cerebellum or thalamus of KOM2. Mice were sacrificed 3–8 month post-injection and the brains were sequentially extracted and analyzed in the same way as PFF injected KOM2 mice. To passage LB-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn in M83 mice, 2.5 μL GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn at the concentration of 7.52 ng/μL were injected bilaterally into the striatum of M83. Mice were sacrificed 1 month post-injection and the brains were sequentially extracted and analyzed in the same way as PFF injected KOM2 mice.

Immunohistochemistry

For histological studies, animals were transcardially perfused with PBS and the brain and spinal cord were removed and fixed in 70% ethanol (in 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) overnight before being processed for paraffin embedding. IHC was performed on 6 μm thick sections as previously described (Duda et al., 2000; Luk et al., 2012a). The names and dilutions of the primary antibodies used here are shown in Supplementary Table 4. Stained sections were digitized by a Perkin Elmer Lamina scanner at 20X magnification. For quantitative analysis of α-Syn pathology in the mouse brain, Syn506-stained sections spanning the entire mouse brain at ~120 μm intervals were counted manually for the total number of cells with α-Syn positive inclusions. The semi-quantitative heat maps were generated as previously described 32 using Syn506 stained slides. To quantify the spreading of pathological α-Syn in WT mice, representative Syn506-stained brain sections at Bregma 4.28, 2.10, 0.98, −0.22, −1.22, −2.18, −2.92, −3.52, −4.48 mm were counted manually for the number of cells with α-Syn pathology in each brain region. For GCI-WT and PFF-WT mice, 1–3 brain sections at each Bregma point have been quantified and the mean value of these 1–3 brain sections has been used for quantification. For LB-WT mice, because of the low amount of pathology, 3–13 brain sections at each Bregma point have been quantified.

For the quantification of NIs in MSA cases, adjacent sections of medulla or hippocampus from 6 MSA cases were stained with Syn7015 and Syn303. The stained sections were digitalized and the number of NIs labeled by each antibody were quantified manually for each inferior olivary nucleus in medulla and dentate gyrus in hippocampus. To quantify the number of stained GCIs, three to six 10X images were randomly sampled in the white matter region near each inferior olivary nucleus or dentate gyrus. The position of these 10X images were digitally labeled by drawing lines on the boundaries, and the exact same 10X images were sampled on adjacent sections by copying these annotations using the digitized image, and the total number of GCIs labeled by Syn7015 or Syn303 in these sampled areas were counted manually.

To grade the α-Syn pathology revealed by Syn7015 or Syn303 IHC in MSA and LB-spectrum α-synucleinopathies, adjacent sections of hippocampus, frontal cortex, substantia nigra, cerebellum or midbrain from 3 AD, 3 DLB, 3 PDD, 4 MSA(C) and 3 MSA(P) cases (see Supplementary Table 1) were stained with Syn7015 and Syn303 and graded by experienced pathologists. To quantify the ratio of total amount of Syn7015 positive versus Syn303 positive GCI or LB, the stained adjacent sections were digitalized and the total area occupied by Syn7015 or Syn303 positive α-Syn inclusions were quantified using an automated threshold-based algorithm by HALO software. Then the ratios of total Syn7015 positive area versus Syn303 positive area were calculated. For the serial dilution of Syn7015 and Syn303, all the ratios were calculated against the area occupied by IHC conducted with the highest concentration of Syn303 (45 ng/mL).

Animals

2–3 months old C57BL6/C3H WT mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). M2 mice expressing wild type human α-Syn in oligodendrocytes under the control of CNP promoter have been described previously 21. KOM2 mice were generated by crossing M2 mice with Snca−/− mice 33. 3–4 months old KOM2 has been used for the study. All breeding, housing, and experimental procedures were performed according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Experimental Animals and approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Both male and female mice were used for this study. Roughly equal number of male and female KOM2 mice has been used in each group. All the GCI-WT, LB-WT mice are female. All the 3mpi PFF-WT mice are female as well. For the 6mpi PFF-WT mice, 3 of them are male and 1 is female.

Immunocytochemistry and quantification

For regular immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 15 min followed by permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. To examine α-Syn aggregates, cells were fixed with 4% PFA containing 1% Triton X-100 for 15 min to remove soluble proteins. Fixed coverslips were blocked with 3% BSA and 3% FBS for 1 hr at room temperature and incubated with specific primary antibodies (Supplementary Table 4) at 4°C overnight followed by staining with secondary antibodies for 2 hr at room temperature. After mounting with Fluoromount G with DAPI (eBioscience), coverslips were scanned on a Perkin Elmer Lamina scanner. Total amount of 81A signal as well as total amount of MAP2 signals for neuronal cultures and total number of DAPI positive nuclei for oligodendrocytes and QBI-WT-Syn cells were quantified using Indica Labs HALO software. For cells cultured in 96-well plates, cells were incubated in DAPI solution after staining with secondary antibodies. Then, plates were scanned with In Cell Analyzer 2200 (GE Healthcare) and analyzed using the accompanying software (In Cell Toolbox Analyzer).

Purification and Depletion of α-Syn from the Sarkosyl Insoluble Fraction by Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Control mouse IgG (Sigma) or Syn9027 MAb, an in house generated Mab against α-Syn (epitope aa130-140), were coupled to tosyl activated Dynabeads (Invitrogen) or NHS-Activated Magnetic Beads (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For IP purification, sarkosyl insoluble fractions from diseased brains were incubated with control IgG coupled beads in Dulbecco’s PBS and rotated at 4°C overnight. The resulting supernatant was then incubated with Syn9027 coupled beads in a rotator at 4°C overnight to capture α-Syn. The following day, the Syn9027 beads were washed 3 times with Dulbecco’s PBS and incubated with 0.1 M ethanolamine (pH 11.5) for 3–7 min at 55°C to elute the bound α-Syn, which was then neutralized immediately with 1 M Tris (pH 7.0) and the eluted samples were stored at −80°C until use. For IP depletion, the sarkosyl insoluble fractions from diseased brains were incubated with Syn9027 coupled beads at 4°C overnight. The resulting supernatants were incubated with Syn9027 beads again for a second round of α-Syn depletion and the final supernatants were stored at −80°C until use.

Evaluate α-Syn expression in KOM2 mice

Total proteins were extracted from KOM2 and WT mice by sonicating the brain in 1% Triton X-100-containing HS buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors, and centrifuged at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C. Protein concentration of the supernatant were determined by BCA assay and same amount of protein from each mice were resolved on 12% Bis-Tris gel and immunoblotted with antibodies against total α-Syn, mouse α-Syn or β-tubulins.

Generation of PFF in different cell lysates

Neuron and oligodendrocyte cell lysates were prepared by sonicating primary rat hippocampus or cortical neurons at DIV12 and oligodendrocyte cultures at DIV10-12 in DPBS. The protein concentrations of cell lysates were evaluated by BCA assay and adjust to 1.86 mg/mL. α-Syn monomer were added to these cell lysates at the final concentration of 500 μg/mL and shake at 37°C with constant agitation at 1,000 rpm for 14 days.

Statistical Analysis

Unless otherwise specified, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test was used for all the comparisons in the study, and differences with p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. For each t test, F test was also performed to evaluate the differences in variances. If there is a significant difference in variances (p<0.05 by F test), Welch’s correction on t-test was performed. Multiple comparisons were adjusted with Bonferroni correction. Detailed information of statistical analysis was provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Extended Data

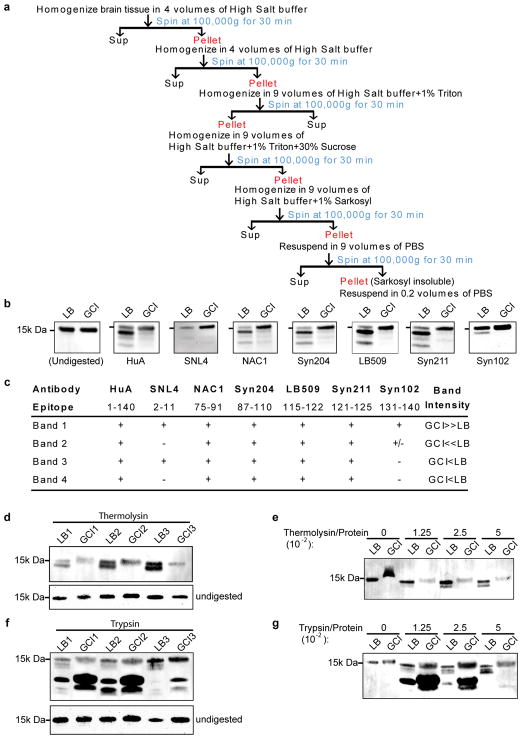

Extended Data Fig. 1. Biochemical analysis of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn.

(a) Schematic diagram for sequential extraction of α-synucleinopathy brains. Disease brain samples were sequentially extracted with buffer of increasing extraction strengths (1% Triton X-100 followed by 1% sarkosyl) to remove soluble proteins. (b) PK-digested GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn were immunoblotted with a series of antibodies targeting specific domains of α-Syn that spanning the entire molecule. (c) Summary of the results for experiments described in (b). (d) Thermolysin-digested and undigested sarkosyl-insoluble fractions from 3 LB disease cases (LB1-LB3) and 3 MSA cases (GCI1-GCI3) were resolved on 12% Bis-Tris gel and immunoblotted with antibody against α-Syn (Syn211). (e) Sarkosyl-insoluble fractions from a pair of LB disease and MSA cases were incubated with increasing concentrations of thermolysin (with the ratio of thermolysin versus total protein range from 1.25 × 10−2 to 5 × 10−2) and immunoblotted with antibody against α-Syn (Syn211). Undigested fractions were loaded on the same gel. (f) Trypsin-digested and undigested sarkosyl-insoluble fractions from 3 LB disease cases (LB1-LB3) and 3 MSA cases (GCI1-GCI3) were resolved on 12% Bis-Tris gel and immunoblotted with antibody against α-Syn (Syn211). (g) Sarkosyl-insoluble fractions from a pair of LB disease and MSA cases were incubated with increasing concentrations of trypsin (with the ratio of trypsin versus total protein range from 1.25 × 10−2 to 5 × 10−2) and immunoblotted with antibody against α-Syn (Syn211). Undigested fractions were loaded on the same gel. The experiments shown in (b) and (d–g) have been repeated 3 times with similar results. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

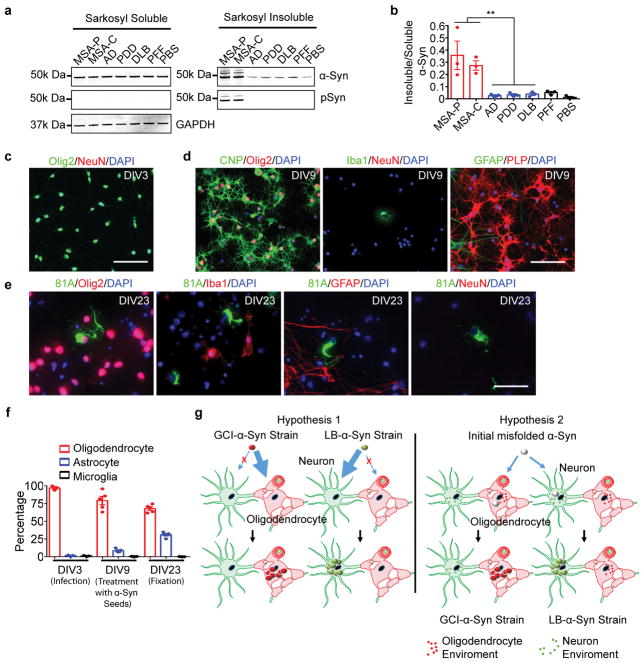

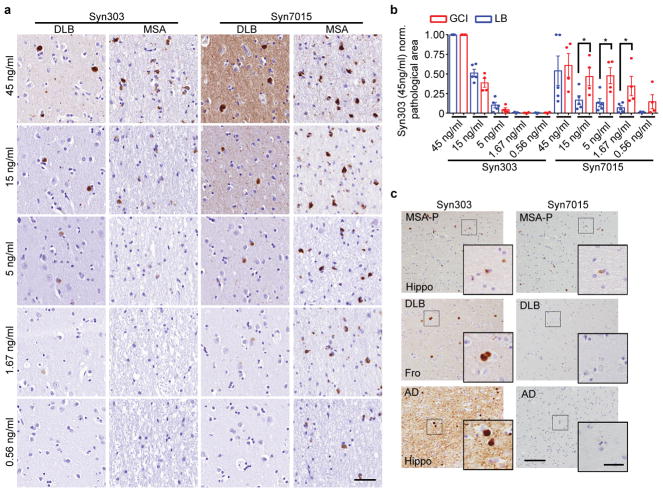

Extended Data Fig. 2. Syn7015 preferentially recognizes GCIs over LBs.

(a) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) using a series dilution of Syn303 or Syn7015 on serial sections of a DLB brain and a MSA brain. At 45 ng/ml, Syn7015 recognized both LBs and GCIs. At lower concentrations, particularly 1.67 ng/ml and 0.56 ng/ml, Syn7015 preferentially recognizes GCIs over LBs (repeat with 4 cases). (b) Quantification of the area occupied by pathological α-Syn stained with serial dilutions of Syn7015 or Syn303 on serial sections of 2 MSA-P, 2 MSA-C, 1AD, 2PDD and 2DLB cases. The results for each case are normalized to Syn303 staining at 45 ng/ml. (GCI, n=4; LB, n=5 cases). (c) α-Syn pathology revealed by Syn303 or Syn7015 in adjacent sections from LB disease and MSA cases (repeat with 7 cases). Results shown as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] (*p < 0.05). Scale bar: 50μm (a), 100 μm (c), 25 μm [(c) inset]. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

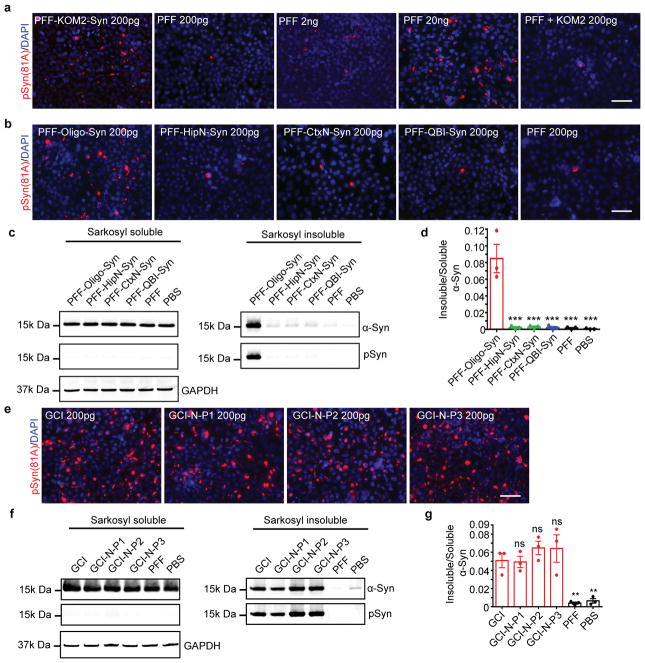

Extended Data Fig. 3. GCI-α-Syn is more potent to induce α-Syn pathology in primary oligodendrocytes.

(a) Oligodendrocytes treated with the same amount of GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFF were sequentially extracted with 1% Triton-X100 lysis buffer followed by 1% Sarkosyl lysis buffer, which were combined together as the Sarkosyl soluble fraction. The Sarkosyl insoluble pellets were resuspended in DPBS by sonication. Both soluble and insoluble fractions were immunoblotted with antibody against total or S129 phosphorylated α-Syn. (b) Densitometric quantification of insoluble/soluble α-Syn for experiments described in (a) (n=3 independent experiments). (c–d) Primary oligodendrocyte cultures were immunostained with antibodies against various cell type specific markers: CNP (oligodendrocytes), olig2 (oligodendrocytes), Iba1 (microglial cells), NeuN (neurons), GFAP (astrocytes), PLP (oligodendrocytes) at day in vitro 3 (DIV3) (c) or DIV9 (d). (e) Insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn induced in primary oligodendrocytes overexpressing α-Syn were co-stained with antibodies against various cell type specific markers demonstrating that the cells with α-Syn pathology are oligodendrocytes. (f) Percentage of different type of cells (oligodendrocytes, microglial and astrocytes) in oligodendrocyte culture, at DIV3 (the time point for virus infection), DIV9 (the time point for misfolded α-Syn treatment) and DIV23 (the time point for fixation) (DIV3, n=3; DIV9, n=5, DIV23, n=5 coverslips from three independent experiments). (g) Working hypotheses on the different cell-type distributions of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn strains in diseased brains. Hypothesis 1: The unique properties of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn strains determine their different cell type distribution. GCI-α-Syn strain (represented by red spheres) is more efficient in inducing α-Syn pathology in oligodendrocytes, while LB-α-Syn strain (green spheres) is more efficient in inducing α-Syn pathology in neurons. Hypothesis 2: GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn strains do not have cell type preference, they could be initiated by the same misfolded α-Syn seeds (grey spheres), but the different intracellular environment of neurons and oligodendrocytes convert them to different strains. Results shown as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] (**p < 0.01). Scale bars: 100μm (c) and (d); 50μm (e). The experiments shown in (a) and (c–e) have been repeated 3 times with similar results. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data. Fig. 4. The seeding properties of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn do not show cell type preference.

(a) Soluble and insoluble fractions from primary neurons treated with the same amount of GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFF were immunoblotted with antibodies against total or S129 phosphorylated α-Syn. (b) Densitometric quantification of insoluble/soluble α-Syn for experiments described in (a) (n=3 independent experiments). (c) Quantification of phosphorylated α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells induced by equal amount of GCI-α-Syn (MSA-C, MSA-P), LB-α-Syn (PDD, DLB and AD) or PFFs. (GCI, n=8; LB, n=9 different preparations) (d) Soluble and insoluble fractions from QBI-Syn-WT cells treated with the same amount of GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFF were immunoblotted with antibody against total or S129 phosphorylated α-Syn. (e) Densitometric quantification of insoluble/soluble α-Syn for experiments described in (d) (n=3 independent expreiments). (f) Quantification of insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in primary neurons induced by various concentrations of GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn before or after IP purification (n=3 independent experiments). (g) Quantification of insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in primary neurons incubated with (1) GCI-α-Syn and LB-α-Syn preparations; (2) the same preparations after IP depletion to remove α-Syn; and (3) the depleted preparation to which the same amount of α-Syn PFFs (1ng) was added (n=3 independent experiments). (h) PFFs combined with the GCI-α-Syn preparation depleted of α-Syn behave similar to α-Syn PFFs alone. Quantification of insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in primary neurons seeded by PFFs alone or PFFs combined with depleted GCI preparation (subtract the amount of pathology induced by IP depleted GCI preparation alone) (n=3 independent experiments). (i–j) Primary neuron were treated with GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn or PFF and incubate with chloroquine (Ch) at the day of misfolded α-Syn treatment (DPT0) or 3 days post treatment (DPT3). The amount of insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn were quantified 3 days after chloroquine treatment (DPT0-GCI and PFF, n=3; DPT0-LB, n=4; DPT3, n=4 independent experiments). (k) Quantification of the number of cells with α-Syn pathology in WT mice inoculated with 50 ng of GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn at 6 mpi. (l) Representative photomicrographs of α-Syn pathology (stained by Syn506) in multiple brain regions ipsilateral to the injection site in GCI-α-Syn, PFF and LB-α-Syn injected WT mice. OB: olfactory bulb; Cortex: motor cortex; PIR2: pyramidal layer of piriform area; Str: striatum; Hippo: hippocampus; Amg: Amygdala; ENT: entorhinal cortex; SN: substantia nigra. Results shown as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM] (*p < 0.05;**p < 0.01;****p < 0.0001; ns: not significant). Statistics shown in (c) is two-tail, unpaired t-test using the mean value of each case. Statistics shown in (f) is one-way Anova with Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Statistics shown in (g–h) are two-tail, unpaired t-test adjusted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparison. Statistics shown in (i–j) are two-way ANOVA, with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. The experiments in (a), (d) and (l) has been repeated 3 times with similar results. Scale bar: 100 μm. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

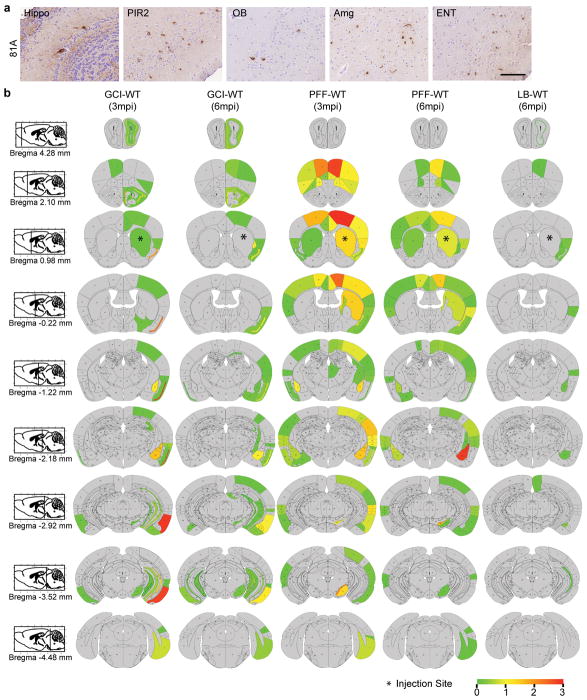

Extended Data Fig. 5. Distribution of α-Syn pathology in injected WT mice.

(a) Representative photomicrographs of α-Syn pathologies stained by antibody against S129-phosphorylated α-Syn (81A) in multiple brain regions in GCI-α-Syn injected WT mice (repeat 3 times). (b) Heat map for the distribution of α-Syn pathology in wild-type mice injected with GCI-α-Syn, PFF or LB-α-Syn. GCI-α-Syn, LB-α-Syn and α-Syn PFF were unilaterally injected into the dorsal striatum of wild-type (WT) mice. The seeded α-Syn pathology was analyzed and graded by IHC with Syn506. The data were presented as heat maps to semi-quantitatively demonstrate the CNS distribution of α-Syn pathology. Each panel represents a coronal plane (Bregma 4.28, 2.10, 0.98, −0.22,−1.22,−2.18, −2.92, −3.52, −4.48mm) for each treatment group. Left column illustrates sagittal views of the corresponding coronal planes. (GCI-WT, n=3; PFF-WT, n=4; LB-WT, n=3 mice). Scale bar: 100 μm (a).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Characterization of KOM2 mice.

(a) Brain sections from KOM2 mice were double labeled with antibodies against α-Syn (LB509) and various cell type specific markers: Olig2 (oligodendrocytes), Iba1 (microglial cells), GFAP (astrocytes) and NeuN (neuron). α-Syn is only expressed in oligodendrocytes in KOM2 mice. (b) Brain lysates of WT and KOM2 mice were immunoblotted with antibody against total α-Syn (Syn 9027), mouse α-Syn (Cell Signaling) and beta-tubulin. Scale bars: 50 μm (a); 25μm (a) inset. The experiments in (a–b) has been repeated 3 times with similar results. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Extended Data Fig. 7. Induction of oligodendroglial α-Syn pathology in KOM2 mice.

(a) Syn506 positive α-Syn aggregates seeded by equal amounts of GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn (18.75 ng) in KOM2 mice at 1, 3 and 6 month post-injection in fimbria and thalamus (b–e) Quantification of the number of oligodendrocytes with α-Syn pathology in optic tract (b), cerebral peduncle (c), fimbria (d), and thalamus (e) at different time points. (1mpi, n=3; 3&6 mpi, n=5 mice) (f) Brain sections from GCI-α-Syn injected KOM2 mice were double labeled with antibodies against misfolded α-Syn (Syn506) and various cell type specific markers. The induced α-Syn pathologies are located in oligodendrocytes in KOM2 mice. (g) GCI-α-Syn injected KOM2 mouse brain sections were stained with an antibody against phosphorylated α-Syn (81A). Results shown as mean ± SEM. Scale bars: 50 μm [(a), (f) & (g)]; 12.5 μm [(a) insets]; 25 μm [(f) insets]. The experiments in (a), (f) and (g) has been repeated 3 times with similar results. Statistics shown in (b–c) are two tail unpaired T-test adjusted with Bonferroni correction. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Distribution of α-Syn pathology in injected KOM2 mice.

Heat maps to semi-quantitatively demonstrate the CNS distribution of α-Syn pathology in KOM2 mice unilaterally injected with GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn into thalamus. α-Syn pathologies were analyzed and graded by IHC with Syn506 at 1 month (n=3), 3 month (n=5) and 6 month (n=5) post injection. Each panel represents a coronal plane (bregma −1.22, −2.18, −2.92, −3.52, −4.48mm) for each treatment group. Since there is no α-Syn pathology in the contralateral side, only the ipsilateral side is shown. The left column illustrates sagittal views of the corresponding coronal planes.

Extended data Fig. 9. Oligodendrocyte environment generate the GCI-α-Syn strain.

(a) IHC of adjacent sections from human or mouse brains with Syn303 and Syn7015. First row: adjacent brain sections of LB disease and MSA cases used for the extraction of LB-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn for injection. Second row: adjacent brain sections of KOM2 mice injected with LB-α-Syn prepared from the brain tissue shown in the first row. OPT and CP are shown here. While the LB-α-Syn used for the injections is Syn7015 negative, the induced oligodendrocyte pathology is Syn7015 positive. Third row: adjacent brain sections of KOM2 mice injected with GCI-α-Syn prepared from the brain sample shown in the first row. OPT and CP were shown. Forth row: adjacent brain sections of M83 mice with α-Syn pathology. Midbrain (MB) and pons are shown. (b) Brain sections from KOM2 mice injected with GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn in the thalamus were double labeled with Syn506 and antibodies against P62 (left panel) or ubiquitin (right panel). (c) Brain sections from GCI-α-Syn or LB-α-Syn injection KOM2 mice were double labeled with Syn506 and GFAP. Both ipsilateral and contralateral optic tracts are shown here. (d) Adjacent sections of substantia nigra (SN) and cortex from 2 different MSA cases were stained with Syn7015 and Syn303. Scale bars: 50 μm (a,b,c); 12.5 μm [(a) insets]; 20μm [(b) inset]. 30 μm (d). The experiments in (a–d) has been repeated 3 times with similar results.

Extended Data Fig. 10. α-Syn pathology induced by passaged PFF and GCI.

(a) Insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells seeded by α-Syn PFFs, α-Syn PFFs that have been passaged in KOM2 mice (PFF-KOM2-Syn) or α-Syn PFFs that were combined with sarkosyl insoluble fraction prepared from uninjected KOM2 mice (PFF+KOM2). (b) Insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells induced by equal amount (200pg) of PFF-Oligo-Syn, PFF-HipN-Syn, PFF-CtxN-Syn, PFF-QBI-Syn and α-Syn PFFs. (c) Soluble and insoluble fractions from QBI-Syn-WT cells treated with the same amount of PFF-oligo-Syn, PFF-HipN-Syn, PFF-CtxN-Syn, PFF-QBI-Syn and PFF were immunoblotted with antibodies against total or S129 phosphorylated α-Syn. (d) Densitometric quantification of insoluble/soluble α-Syn for experiments described in (c) (n=3 independent experiments). (e) Insoluble phosphorylated α-Syn in QBI-WT-Syn cells induced by GCI-α-Syn and GCI-α-Syn that has been passaged in primary neurons for multiple times, i.e. GCI-N-P1, GCI-N-P2, GCI-N-P3. (f) Soluble and insoluble fractions from QBI-Syn-WT cells treated with the same amount of GCI, GCI-N-P1, GCI-N-P2, GCI-N-P3 and PFF were immunoblotted with antibodies against total α-Syn or S129 phosphorylated α-Syn. (g) Densitometric quantification of insoluble/soluble α-Syn for experiments described in (f) (n=3 independent experiments). Statistics shown in (d), and (g) are one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett post hoc test comparing each group with PFF-Oligo-Syn in (d) or GCI in (g). Results shown as mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; (**p<0.01; ***p<0.01; ns: not significant). Scale bars: 50 μm (a), (b) and (e). The experiments in (a–c) and (e–f) has been repeated 3 times with similar results. See Supplementary Table 5 for statistical details. For gel source data, see Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kurt Brunden and Jing Guo for critical reading of the manuscript, Sharon Xiangwen Xie for helping with statisitcs. Linda Kwong and Yan Xu for helping with brain extraction, Dawn Riddle for providing primary neurons, Lisa Romero for helping with quantification, Lakshmi Changolkar for helping with ELISA and all the other members of the Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research for their support. Judith Grinspan and Christiane Richter-Landsberg are thanked for advice on culturing oligodendrocytes. The anti-PSP antibody was provided by Judith Grinspan. This work was supported by NIH/NINDS Udall Center grant NS53488, the Ofer Nimerovsky Family Fund, the Jeff and Anne Keefer Fund and the MSA Coalition Global Seed Grant.

Footnotes

Author Contributions:

C.P. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. R. G., C.M. and M.O. performed the animal experiments and did quantification analysis. R. G. also performed α-Syn ELISA and biochemical analysis. D.J.C. generated the Syn9027 and Syn7015 antibodies and α-Syn PFFs. A.S. generated the KOM2 mice and assisted in stereotaxic injections. J.L.R. scored stained human brain sections. B.Z., R.G. and M.O. performed stereotaxic injections. R.P. performed cell culture experiments. K.C.L performed experiments and reviewed the manuscript. J.Q.T supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript. V.M.Y.L. supervised the study, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript.

There are no competing financial or non-financial interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Lippa CF, et al. Lewy bodies contain altered alpha-synuclein in brains of many familial Alzheimer’s disease patients with mutations in presenilin and amyloid precursor protein genes. The American journal of pathology. 1998;153:1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spillantini MG, et al. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tu PH, et al. Glial cytoplasmic inclusions in white matter oligodendrocytes of multiple system atrophy brains contain insoluble alpha-synuclein. Annals of neurology. 1998;44:415–422. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bousset L, et al. Structural and functional characterization of two alpha-synuclein strains. Nature communications. 2013;4:2575. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo JL, et al. Distinct alpha-synuclein strains differentially promote tau inclusions in neurons. Cell. 2013;154:103–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peelaerts W, et al. alpha-Synuclein strains cause distinct synucleinopathies after local and systemic administration. Nature. 2015;522:340–344. doi: 10.1038/nature14547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prusiner SB, et al. Evidence for alpha-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in humans with parkinsonism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E5308–5317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514475112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Woerman AL, et al. Propagation of prions causing synucleinopathies in cultured cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:E4949–4958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1513426112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fanciulli A, Wenning GK. Multiple-system atrophy. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:1375–1376. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1501657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koga S, Dickson DW. Recent advances in neuropathology, biomarkers and therapeutic approach of multiple system atrophy. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara H, et al. alpha-Synuclein is phosphorylated in synucleinopathy lesions. Nature cell biology. 2002;4:160–164. doi: 10.1038/ncb748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorbatyuk OS, et al. The phosphorylation state of Ser-129 in human alpha-synuclein determines neurodegeneration in a rat model of Parkinson disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:763–768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711053105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Covell DJ, et al. Novel conformation-selective alpha-synuclein antibodies raised against different in vitro fibril forms show distinct patterns of Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/nan.12402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duda JE, Giasson BI, Mabon ME, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Novel antibodies to synuclein show abundant striatal pathology in Lewy body diseases. Annals of neurology. 2002;52:205–210. doi: 10.1002/ana.10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Irwin DJ, et al. Neuropathologic substrates of Parkinson disease dementia. Annals of neurology. 2012;72:587–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.23659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montine TJ, et al. Multisite assessment of NIA-AA guidelines for the neuropathologic evaluation of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2016;12:164–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.07.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Volpicelli-Daley LA, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils induce Lewy body pathology leading to synaptic dysfunction and neuron death. Neuron. 2011;72:57–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luk KC, et al. Exogenous alpha-synuclein fibrils seed the formation of Lewy body-like intracellular inclusions in cultured cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:20051–20056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908005106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpowicz RJ, Jr, et al. Selective imaging of internalized proteopathic alpha-synuclein seeds in primary neurons reveals mechanistic insight into transmission of synucleinopathies. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2017;292:13482–13497. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.780296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luk KC, et al. Pathological alpha-synuclein transmission initiates Parkinson-like neurodegeneration in nontransgenic mice. Science. 2012;338:949–953. doi: 10.1126/science.1227157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yazawa I, et al. Mouse model of multiple system atrophy alpha-synuclein expression in oligodendrocytes causes glial and neuronal degeneration. Neuron. 2005;45:847–859. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giasson BI, et al. Neuronal alpha-synucleinopathy with severe movement disorder in mice expressing A53T human alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2002;34:521–533. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller DW, et al. Absence of alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in normal and multiple system atrophy oligodendroglia. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2005;112:1613–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00702-005-0378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asi YT, et al. Alpha-synuclein mRNA expression in oligodendrocytes in MSA. Glia. 2014;62:964–970. doi: 10.1002/glia.22653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reyes JF, et al. Alpha-synuclein transfers from neurons to oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2014;62:387–398. doi: 10.1002/glia.22611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giasson BI, Murray IV, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. A hydrophobic stretch of 12 amino acid residues in the middle of alpha-synuclein is essential for filament assembly. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:2380–2386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008919200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volpicelli-Daley LA, Luk KC, Lee VM. Addition of exogenous alpha-synuclein preformed fibrils to primary neuronal cultures to seed recruitment of endogenous alpha-synuclein to Lewy body and Lewy neurite-like aggregates. Nature protocols. 2014;9:2135–2146. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toledo JB, et al. A platform for discovery: The University of Pennsylvania Integrated Neurodegenerative Disease Biobank. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. 2014;10:477–484. e471. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo JL, Lee VM. Seeding of normal Tau by pathological Tau conformers drives pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like tangles. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:15317–15331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee EB, Skovronsky DM, Abtahian F, Doms RW, Lee VM. Secretion and intracellular generation of truncated Abeta in beta-site amyloid-beta precursor protein-cleaving enzyme expressing human neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4458–4466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richter-Landsberg C, Vollgraf U. Mode of cell injury and death after hydrogen peroxide exposure in cultured oligodendroglia cells. Experimental cell research. 1998;244:218–229. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iba M, et al. Synthetic tau fibrils mediate transmission of neurofibrillary tangles in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s-like tauopathy. J Neurosci. 2013;33:1024–1037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2642-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abeliovich A, et al. Mice lacking alpha-synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron. 2000;25:239–252. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).