Photosynthesis and productivity are less compromised by low light in NADP-ME C4 grasses relative to PEP-CK and NAD-ME counterparts.

Keywords: Biochemical subtypes, C4 photosynthesis, CO2-concentrating mechanism, low light, shade

Abstract

The high energy cost and apparently low plasticity of C4 photosynthesis compared with C3 photosynthesis may limit the productivity and distribution of C4 plants in low light (LL) environments. C4 photosynthesis evolved numerous times, but it remains unclear how different biochemical subtypes perform under LL. We grew eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes [NADP-malic enzyme (NADP-ME), NAD-malic enzyme (NAD-ME), and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEP-CK)] under shade (16% sunlight) or control (full sunlight) conditions and measured their photosynthetic characteristics at both low and high light. We show for the first time that LL (during measurement or growth) compromised the CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) to a greater extent in NAD-ME than in PEP-CK or NADP-ME C4 grasses by virtue of a greater increase in carbon isotope discrimination (∆P) and bundle sheath CO2 leakiness (ϕ), and a greater reduction in photosynthetic quantum yield (Φmax). These responses were partly explained by changes in the ratios of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC)/initial Rubisco activity and dark respiration/photosynthesis (Rd/A). Shade induced a greater photosynthetic acclimation in NAD-ME than in NADP-ME and PEP-CK species due to a greater Rubisco deactivation. Shade also reduced plant dry mass to a greater extent in NAD-ME and PEP-CK relative to NADP-ME grasses. In conclusion, LL compromised the co-ordination of the C4 and C3 cycles and, hence, the efficiency of the CCM to a greater extent in NAD-ME than in PEP-CK species, while CCM efficiency was less impacted by LL in NADP-ME species. Consequently, NADP-ME species are more efficient at LL, which could explain their agronomic and ecological dominance relative to other C4 grasses.

Introduction

C4 photosynthesis is characterized by the operation of a CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) whereby atmospheric CO2 is initially fixed in the mesophyll cells (MCs) into C4 acids. These acids are subsequently decarboxylated in the bundle sheath cells (BSCs) releasing CO2 where Rubisco, the ultimate CO2-fixing enzyme, is located (Hatch, 1987). The CCM serves to raise the CO2 concentration in the BSCs, thus curbing photorespiration and CO2-saturating photosynthesis at current ambient CO2 concentrations ([CO2]) under high light (Hatch, 1987; Kanai and Edwards, 1999). The CCM requires additional energy costs compared with the C3 cycle associated with the regeneration of the C3 precursor phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the overcycling of CO2. Nevertheless, under warm temperatures, C4 plants have a superior photosynthetic quantum yield (Фmax) relative to C3 plants (Ehleringer and Björkman, 1977; Pearcy et al., 1981; Ehleringer and Pearcy, 1983; Zhu et al., 2008). This explains the ecological dominance of C4 plants in open, high light (HL) environments and their disproportionately high global productivity relative to their small taxonomic representation (Ehleringer et al., 1997; Brown, 1999; Edwards et al., 2010).

Despite their success under HL, C4 plants experience low light (LL) under natural conditions. C4 crops and grasses can form dense canopies where a significant proportion of the leaf area is shaded, in addition to short-term LL exposures during the course of the day (Sage, 2014; Ort et al., 2015). Numerous C4 grasses are adapted to the shade of the forest interior (Sage and Pearcy, 2000). Shading is expected to increase in the understorey of C4 grass-dominated ecosystems with predicted woody thickening under increasing atmospheric [CO2] (Bond and Midgley, 2012; Saintilan and Rogers, 2015). Consequently, it is important to investigate the efficiency of C4 photosynthesis under LL across diverse C4 plants.

C4 photosynthesis has evolved independently many times, resulting in three biochemical subtypes named after the primary C4 acid decarboxylase enzyme found in the BSCs, and they are NADP-malic enzyme (ME), NAD-ME, and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEP-CK) (Hatch 1987). PEP-CK operates as a secondary decarboxylase in many C4 species (Leegood and Walker, 2003; Furbank, 2011; Sharwood et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). However, the primary decarboxylase is generally associated with a suite of anatomical, biochemical, and physiological features (Gutierrez et al., 1974; Hattersley, 1992; Kanai and Edwards, 1999; Ghannoum et al., 2011), making it a suitable classification basis for the purpose of the current study investigating the efficiency of the C4-CCM. The grass family includes species from all biochemical subtypes (Sage and Pearcy, 2000; Edwards et al., 2010), but our understanding of how different C4 subtypes respond and acclimate to LL environments remains limited.

It is well demonstrated that the C4 subtypes have different leaf dry matter carbon isotope composition (δ13C) and Фmax. In particular, C4 grasses with the NAD-ME subtype (i.e. NAD-ME as the primary decarboxylase) show lower leaf δ13C (i.e. more negative values which are closer to the C3 range) and Фmax, while NADP-ME and PEP-CK species (i.e. those with NADP-ME and PEP-CK as the primary decarboxylases, respectively) show the highest and intermediate values, respectively (Hattersley, 1982; Ehleringer and Pearcy, 1983). There is a paucity of data comparing the response to shade of leaf δ13C and Фmax of the various C4 subtypes. Using 14 C4 grasses, Buchmann et al. (1996) found that leaf δ13C values of NAD-ME species were most impacted by shade, followed by PEP-CK and NADP-ME species. In a large survey of C4 grasses, von Caemmerer et al. (2014) reported that leaf δ13C was equally affected by growing season irradiance (winter versus summer) in NAD-ME and NADP-ME grasses. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that carbon isotope composition and discrimination are not significantly affected until photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) decreases below 700 μmol m–2 s–1 (Buchmann et al., 1996).

In C4 plants, both photosynthetic and post-photosynthetic discrimination factors determine leaf δ13C (Farquhar, 1983; von Caemmerer et al., 2014). Reduced leaf δ13C under LL may be attributed to increased photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (ΔP) and BSC leakiness (ϕ) as a result of reduced CCM efficiency (Henderson et al., 1992). For example, LL may reduce the activity of the C3 cycle to a greater extent than that of the C4 cycle, leading to greater overcycling. In turn, this will lead to higher ϕ and energetic cost of operating the C4-CCM. Consequently, we hypothesized that LL will differentially compromise the C4-CCM efficiency depending on the biochemical subtype. In particular, we predicted that LL will increase leaf δ13C and ΔP, and reduce Фmax to a greater extent in NAD-ME grasses, followed by PEP-CK and NADP-ME species (Hypothesis 1).

Short- and long-term photosynthetic responses to LL are expected to differ. Following long-term exposure to LL (shade), the photosynthetic apparatus commonly acclimates to maximize light use efficiency (Björkman, 1981; Boardman, 1977; Sage and McKown, 2006). Depending on the plant species and ecotype, acclimation may be minimal or profound (Ward and Woolhouse, 1986a, b; Björkman and Holmgren, 1966). Overall, acclimation of C3 and C4 plants to shade involves partitioning of photosynthetic nitrogen (N) away from Rubisco towards the light-harvesting processes (Boardman, 1977; Björkman, 1981; Hikosaka and Terashima, 1995; Evans and Poorter, 2001; Walters, 2005; Tazoe et al., 2006; Pengelly et al., 2010). NAD-ME species are known to have higher leaf N content and a greater N fraction invested in Rubisco relative to NADP-ME species (Ghannoum et al., 2005). Hence, the former subtype may have a greater flexibility to reallocate N under shade especially since, as mentioned above, LL is expected to reduce the activity of the C3 cycle (e.g. Rubisco) more than the C4 cycle [e.g. phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase (PEPC)]. However, optimal photosynthetic acclimation of C4 photosynthesis to shade is expected to involve parallel reductions in the activities of the C3 and C4 cycles in order to curb leakiness and maintain an efficient CCM and quantum yield (Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014a, b), which does not seem to be the case for NAD-ME species in Buchmann et al. (1996). Consequently, we hypothesized that NAD-ME species will exhibit a greater photosynthetic acclimation in response to shade relative to the other two subtypes. This will manifest as a greater photosynthetic down-regulation and higher leakiness in the LL-acclimated leaves of NAD-ME species relative to the other two subtypes (Hypothesis 2).

To address these two hypotheses, we investigated the photosynthetic responses of eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes (Table 1) to short-term (200 µmol quanta m–2 s–1 versus 2000 µmol quanta m–2 s–1) and long-term (16% versus 100% sunlight; Supplementray Fig. S1A at JXB online) light treatments. We sought to elucidate the underlying mechanisms by describing changes in photosynthetic rates and enzyme activities, and in the CCM efficiency as described by leakiness and quantum yield. Our results indicated that NADP-ME species are generally more efficient at LL due to effective co-ordination of the C4 and C3 cycles.

Table 1.

List of C4 grasses used in the current study

| C4 subtype | C4 tribe | Species |

|---|---|---|

| NADP-ME | Paniceae |

Cenchrus ciliaris

Panicum antidotale |

| Andropogoneae |

Sorghum bicolor

Zea mays |

|

| PEP-CK | Paniceae Chloridoideae |

Megathyrsus maximus

Chloris gayana |

| NAD-ME | Paniceae Chloridoideae |

Panicum coloratum

Leptochloa fusca |

Materials and methods

Plant culture

The experiment was conducted in a naturally lit glasshouse chamber (5 m3) during the Australian summer. Within the chamber, an aluminium structure (1.5 × 5 m3) was covered with white shade cloth (Premium Hortshade Light, Model No. 428976, Coolaroo, VIC, Australia). A PPFD of ~100 μmol quanta m–2 s–1 was achieved inside the shade structure by adjusting the number of cloth layers. The impact of heavy shade during cloudy days was minimized by supplementing external growth light (LimiGrow Pro S325, Emeryville, CA, USA) to achieve a leaf-level PPFD of 100 μmol m–2 s–1. The chamber temperature was maintained at 28/22 °C for day/night with an in-built glasshouse temperature-controlled system. The air temperature and relative humidity (RH) at leaf level were monitored using Rotronic HC2-S3 (Bassersdorf, Switzerland) sensors placed in a shield vented with a 12 V fan. A Licor quantum sensor (LI-190, Lincoln, NE, USA) was mounted at the leaf level to monitor incident PPFD in the unshaded and shaded glasshouse structure. Data from these sensors were stored using a Licor data logger (LI-1400). Through the experiment, average midday ambient PPFD, T, and RH at leaf level were 741 μmol m–2 s–1, 25 ºC, and 69% in the sun treatment. These figures in the shade treatment were 119 μmol m–2 s–1, 26 °C, and 65% (see Supplementary Fig. S1C). Hence, the shade treatment was equivalent to 16% of sunlight measured in the sun treatment, averaged over the experimental period (Supplementary Fig. S1). Instantaneous leaf temperature was measured using a hand-held, non-contact infrared thermometer (AGRI-THERM II™, Chino Hills, CA USA). On average, shaded leaves were 1–2 °C cooler than sun leaves (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

Locally collected soil was sun dried (Pinto et al., 2014), coarsely sieved, and added to 3.5 litre cylindrical pots. Pots were watered to 100% capacity and transferred to the glasshouse chamber. Seeds for grasses used in this study (Table 1) were obtained from the Australian Plant Genetic Resources Information System (QLD, Australia) and Queensland Agricultural Seeds Pty. Ltd. (Toowoomba, Australia). In the current study, we used 2–3 representative species belonging to each of the C4 subtypes. Within each subtype, species were selected from different C4 origins (tribes in Table 1) to randomize the C4 origin effect, and hence focus on the subtype effect.

Seeds were germinated in a commercial Osmocote® professional, seed raising and cutting mix (Scotts, Bella Vista, NSW, Australia). Three to four weeks after germination, two healthy seedlings were transplanted into each of the soil-filled and pre-irrigated pots. A week later, one healthy seedling was left in each pot while the other was removed. Plants were allowed to grow until the 5–6 leaf stage in full sunlight before they were transferred to the shade treatment. There were eight pots per species and light treatment. Pots were randomly positioned and regularly rotated within each treatment throughout the experiment. Plants were well watered daily with added commercial soluble fertilizer (Aquasol, N:P:K=23.3:3.95:14; Yates, Wetherill Park, NSW, Australia).

Leaf gas exchange measurements

Leaf gas exchange was measured with a portable open gas exchange system (LI-6400XT, LI-COR). The youngest last fully expanded leaf (LFEL) on the main stem of a 6- to 9-week-old plant was measured at a leaf temperature of 28 °C between 10.00 h and 14.00 h. Shaded plants developed a minimum of three new leaves under shade before gas exchange measurements were made.

Each leaf was allowed to reach a steady state, at least 20 min, CO2 assimilation rate (A) at ambient [CO2] of 407 µbar, PPFD of 2000 μmol m–2 s–1, and RH of 50–70%. After this, a steady-state measurement [performed concurrently with tunable diode-laser (TDL) analysis; see below for details] was taken. Subsequently, the response of A to step increases of intercellular CO2 (Ci), the A–Ci curve, was measured by raising the LI-6400XT leaf chamber [CO2] in 10 steps between 50 µbar and 1500 µbar. After completing the A–Ci curve at PPFD 2000 μmol m–2 s–1, the leaf was allowed to reach a steady state of gas exchange at saturating CO2 (660 µbar) before measuring the responses to PPFD. The light response curve was measured from HL to LL (11 steps) followed by measurements of dark respiration (Rd) at ambient [CO2] of 407 µbar after 20 min in a dark leaf chamber. Prior to LL steady-state measurement (performed concurrently with TDL analysis; see below for details), the same leaf was allowed to reach a steady-state A similarly to HL measurements, except PPFD was controlled at 250 μmol m–2 s–1. This was followed by measuring the A–Ci curve at the same light (LL) as described above. There were 3–4 replicates per treatment. The initial slope (IS) of the A–Ci curve was estimated for the linear part of the A–Ci curve measured at HL where Ci is <55 µbar. The aximum CO2 assimilation rate (A) on the A–Ci curve was considered as the CO2-saturated rate (CSR). The A–Ci curves measured at LL could not be used for accurate IS determination due to low overall rates. The light response curves were fitted using the following equation (Ögren and Evans, 1993):

| (1) |

where, I=absorbed irradiance, we assumed absorptance=0.85; A=CO2 assimilation rate at given light; Φnls=maximum quantum yield of PSII; Amax=light-saturated CO2 assimilation rate; and θ=curvature factor of the light response curve. In addition, the slope of a linear part of the light response curve (PPFD <120 μmol m–2 s–1) was estimated as the ‘apparent’ maximum quantum yield of PSII (Фmax). We consider this estimate in our further analysis.

Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination

Bundle sheath leakiness (ϕ) was determined by measuring real-time 13CO2/12CO2 isotope discrimination using a LI-6400XT interfaced with a tunable diode laser, TDL (TGA100, Campbell Scientific, Inc., Logan, UT, USA). The mean SD for repeated TDL measurements of δ13C values for a reference gas was 0.09‰. Observed photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination against (ΔP) was calculated using (Evans et al., 1986):

| (2) |

| (3) |

where δe, δo, Ce, and Co are the δ13C (δ) and CO2 mole fraction (C) of the air entering (e) and leaving (o) the leaf chamber measured with the TDL-LI-6400 set up. Leakiness at high light (ϕh) was calculated using the model of Farquhar (1983) as modified by Pengelly et al. (2010, 2012) and von Caemmerer et al. (2014):

| (4) |

where t, the ternary correction factor, is calculated as per Farquhar and Cernusak (2012):

| (5) |

where E is the transpiration rate, gtac the total conductance to CO2 diffusion including boundary layer and stomatal conductance (von Caemmerer and Farquhar, 1981). The combined fractionation factor through the leaf boundary layer and stomata is denoted by a′,

| (6) |

Definition and units for the variables included in the above equation are described in Table 2, but briefly, Ca, Ci, and Cls are the ambient, intercellular and leaf surface CO2 mole fractions respectively; ab (2.9‰) is the fractionation occurring through diffusion in the boundary layer; s (1.8‰) is the fractionation during leakage of CO2 out of the bundle sheath assuming there is no HCO3– leakage out of BSCs (Henderson et al., 1992); a (4.4‰) is the fractionation due to diffusion in air (Evans et al., 1986); and ai is the fractionation factor associated with the dissolution of CO2 and diffusion through water (1.8‰).

Table 2.

Statistical summary

| Parameter | Species | Treat | Species×treatment | Species (rand) | Subtype | Treatment | Subtype×treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total DM (g per plant) | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | ** | ** |

| Total leaf area (m2 per plant) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | * |

| Root/shoot DM | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ** | ns |

| LMA (g m–2) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | ns |

| Leaf Nmass (mg g–1) | *** | * | *** | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| Leaf Narea (gm–2) | *** | *** | *** | ** | ns | *** | ns |

| Leaf NUE | *** | *** | ** | *** | 0.10 | ** | * |

| ∆DM (‰) | *** | *** | *** | *** | * | * | * |

| PNUE (µmol CO2 s–1 g–1 N) | *** | *** | *** | NA | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| PWUE (µmol CO2 mol–1 H2O) | *** | * | * | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| A h at HL (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.09 | ** | * |

| A l at LL (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | ** | *** | ** | ns | * | * |

| g sh at HL (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | ** | *** | ns | ** | 0.07 |

| g sl at LL (µmol m–2 s–1) | * | ns | ns | * | ns | ns | ns |

| ∆Ph at HL (‰) | *** | *** | * | *** | ns | 0.10 | ns |

| ∆Pl at LL (‰) | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| C i/Cah at HL | *** | *** | 0.06 | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| C i/Cal at LL | *** | ns | * | 0.07 | ns | ns | ns |

| Leakiness (Фh) at HL | *** | ** | * | *** | ns | ** | ns |

| Leakiness (Фl) at LL | *** | ns | ns | *** | ns | ns | ns |

| R d (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | * | ** | ns | 0.06 | ns |

| IS at HL (µmol m–2 s–1 bar–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | 0.10 |

| CSR at HL (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.07 | ** | * |

| IS/CSR at HL | *** | ns | * | * | ns | ns | ns |

| A max (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | NA | 0.10 | ** | * |

| Фmax (mol CO2 mol-1quanta) | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.08 | * | * |

| Curvature factor (θ) | *** | 0.08 | *** | * | 0.10 | 0.08 | * |

| Initial Rubisco activity | * | *** | * | * | ns | * | * |

| Rubisco activity (µmol m–2 s–1) | ns | *** | ns | * | ns | * | ns |

| Rubisco sites (µmol m–2) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | ns |

| Rubisco activation (%) | *** | *** | *** | * | ns | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| PEPC activity (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.10 | ** | * |

| PEPC/Rubisco activity | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.08 | * | * |

| NADP-ME activity (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | NA | * | * | * |

| NAD-ME activity (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | 0.10 | * | ns |

| PEP-CK activity (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | ns |

| DCs (µmol m–2 s–1) | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | * | 0.10 |

| Protein (g m–2) | * | *** | *** | NA | ns | * | ns |

Summary of statistical analysis using two-way ANOVA to test for the effects of species and light treatment, and a linear-mixed effect model to test subtype and light treatment effects where species were considered as a random variable.

ns, not significant (P>0.05); *P<0.05; ** P<0.01; ***P<0.001

and are defined as in von Caemmerer et al. (2014):

| (7) |

and

| (8) |

where b3 is the fractionation by Rubisco (30‰); b4 is the combined fractionation of the conversion of CO2 to HCO3– and PEP carboxylation (–5.41‰ at 28 °C)(Henderson et al., 1992; Mook et al., 1974); f is the fraction associated with photorespiration; and Vo and Vc are the rates of oxygenation and carboxylation, respectively. Under HL we assumed no photorespiration, hence the term (Pengelly et al., 2010, 2012; Ubierna et al., 2013; von Caemmerer et al., 2014). The reference gas supplied to the LI-6400XT during gas exchange measurements had δ13C= –5.5‰. Therefore, the value for the fractionation factor e associated with respiration was calculated assuming recent photoassimilates as the respiratory substrate (Stutz et al., 2014). Thus, e equalled the difference between δ13C in the CO2 sample line in LI-6400XT and that in the glasshouse chamber (–8‰; Tazoe et al. (2008)). A and Rd (von Caemmerer et al., 2014) denote the CO2 assimilation rate and day respiration, respectively; Rd was assumed to equal measured dark respiration. We assumed mesophyll conductance, gm=1.4 mol m–2 s–1 at 28 °C (for C4 the model plant Setaria viridis) (Ubierna et al., 2017).

Leakiness at low light (ϕl) was calculated as described by Bellasio and Griffiths (2014b) and Ubierna et al. (2013). Briefly, electron transport flux (Jt) at low light was derived by deploying the light-limited C4 photosynthesis model to calculate Cs (CO2 mole fraction in the bundle sheath), Vp (PEP carboxylation rate), Vc (Rubisco carboxylation rate), and Vo (Rubisco oxygenation rate) at LL using the C4 model (von Caemmerer, 2000) (see Supplementary Appendix S1). It should be noted that we used measured values for the fraction of PSII in BSCs, α (0 for NADP-ME and 0.2 for PEP-CK and NAD-ME) and half of the reciprocal of Rubisco specificity, γ* (0.000255, 0.00023, and 0.000233 for NADP-ME, NAD-ME, and PEP-CK, respectively) (Table 2; Sharwood et al., 2016a) for biochemical subtypes of C4 photosynthesis during the calculation of Jt. These parameters were then used to calculate (the combined effects of fractionations by the CO2 dissolution, hydration, and PEPC activity at LL) and (Rubisco fractionation at LL by accounting for the fraction during respiration and photorespiration) (Farquhar, 1983; Ubierna et al., 2013) to calculate ϕl in the following equation,

| (9) |

other variables and unit are as defined in Table 2, but briefly Cm is the mesophyll CO2 mole fraction given by

| (10) |

Subtype-specific values for α and γ* improved the estimations of ϕl as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S7.

Activity of Rubisco, PEPC, NADP-ME, NAD-ME, and PCK

Following gas exchange measurements, replicate discs (0.4–1 cm2) were rapidly frozen in liquid N then stored at –80 °C until analysed. Two sets of extractions were performed to complete the biochemical analysis. For Rubisco activity, activation, and content, PEPC and NADP-ME activity, and soluble protein assays, the extraction buffer was purged of CO2 overnight by bubbling a weak jet of nitrogen gas through the basic buffer [50 mM EPPS-NaOH (pH 7.8), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA]. Each leaf disc was extracted in 0.8 ml of ice-cold extraction buffer [50 mM EPPS-NaOH (pH 7.8), 5 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 10 μl of protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma), 1% (w/v) polyvinyl polypyrrolidone (PVPP)] using a 2 ml Tenbroeck glass homogenizer kept on ice. Chlorophyll content was estimated according to Porra et al. (1989) by mixing 100 µl of total extract with 900 µl of acetone. The extract was then centrifuged at 15 000 g for 1 min and the supernatant was used for the subsequent assays. For Rubisco content, subsamples of the supernatant were incubated for 10 min in activation buffer [50 mM EPPS (pH 8.0), 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM NaHCO3]. Rubisco content was estimated by the irreversible binding of [14C]CABP (2-C-carboxyarabinitol 1,5-bisphosphate) to the fully carbamylated enzyme (Sharwood et al., 2008). Extractable soluble proteins were measured using the Pierce Coomassie Plus (Bradford) protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA).

The activities of the photosynthetic enzymes Rubisco, PEPC, and NADP-ME were measured using spectrophotometric assays as described previously (Jenkins et al., 1987; Ashton et al., 1990; Sharwood et al., 2008, 2014, 2016b; Pengelly et al., 2010). Briefly, initial Rubisco activity was measured in assay buffer containing 50 mM EPPS-NaOH (pH 8), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM ATP, 5 mM phosphocreatine, 20 mM NaHCO3, 0.2 mM NADH, 50 U of creatine phosphokinase, 0.2 mg of carbonic anhydrase, 50 U of 3-phosphoglycerate kinase, 40 U of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, 113 U of triose-phosphate isomerase, and 39 U of glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and the reaction initiated by the addition of 0.22 mM ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP). For maximal Rubisco activity, the supernatant was activated in assay buffer for 10 min at 25 °C before initiation of the reaction. Rubisco activation was calculated as the initial/maximal Rubisco activity ratio. Our Rubisco activity from in vitro assays was slightly lower than CO2 assimilation rates. Hence, in the current study, we presented Rubisco activity estimated from Rubisco sites measured with CABP assay and published Rubisco Kcat for individual species (Sharwood et al., 2016a), and Rubisco activation values are from in vitro initial and activated Rubisco assays.

PEPC activity was measured in assay buffer [50 mM EPPS-NaOH (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EDTA, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM NADH, 5 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 0.2 mM NADH, 1 mM NaHCO3, 1 U of malate dehydrogenase (MDH)] after the addition of 4 mM PEP. NADP-ME activity was measured in assay buffer [50 mM NADP-ME buffer (pH 8.3), 4 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM NADP, 0.1 mM EDTA] after the addition of 5 mM malic acid.

The activity of PEP-CK was measured in the carboxylation direction using the method outlined previously (Koteyeva et al., 2015; Sharwood et al., 2016b). For PEP-CK and NAD-ME activity, a separate leaf disc was homogenized in extraction buffer containing 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton, 5 mM DTT, 1% PVPP, and 2 mM MnCl2 using a 2 ml Tenbroeck glass homogenizer kept on ice. The extract was centrifuged at 21 130 g for 1 min and the supernatant used for PEP-CK and NAD-ME activity assays. PEP-CK activity was measured in assay buffer containing 50 mM HEPS (pH 6.3), 4% β-mercaptoethanol, 100 mM KCl, 90 mM KHCO3, 0.5 mM ADP, 2 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM NADH, 6 U of MDH, and 5 mM aspartic acid after the addition of 10 mM PEP. NAD-ME activity was measured in 25 mM Tricine (pH 8.3), 5 mM DTT, 2 mM NAD, 0.1 mM acetyl-CoA, 4 mM MnCl2, and 2 mM EDTA after the addition of 5 mM malic acid. Enzyme activity was calculated by monitoring the decrease/increase of NADH+ absorbance at 340 nm with a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (model 8453, Agilent Technologies Australia, Mulgrave, Victoria).

SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis of photosynthetic proteins

SDS–PAGE and immunoblot analysis of photosynthetic proteins were performed as described in Sharwood et al. (2014). The procedures are described below.

Subsamples of total leaf extracts used for enzyme assays were mixed with 0.25 vols of 4× LDS buffer (Invitrogen) containing 100 mM DTT and placed in liquid nitrogen, then stored at –20 °C until they were analysed. For confirmatory visualization, protein samples were separated by SDS–PAGE in TGX Any kD (BioRad) pre-cast polyacrylamide gels buffered with 1× Tris-glycine SDS buffer (BioRad) at 200 V using the Mini-Protean apparatus at 4 °C. Proteins were visualized by staining with Bio-Safe Coomassie G-250 (BioRad) and imaged using the VersaDoc imaging system (BioRad).

For immunoblot analyses, samples of total leaf proteins were separated by SDS–PAGE as outlined above, then transferred at 4 °C to nitrocellulose membranes (0.45 µm; BioRad) using the Xcell Surelock western transfer module (Invitrogen) buffered with 1× Transfer buffer [20 × 25 mM Bicine, 25 mM Bis-Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 20% (v/v) methanol]. After 1 h transfer at 30 V, the membrane was placed in blocking solution [3% (w/v) skim milk powder in Tris-buffered saline (TBS); 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8, 150 mM NaCl] for 1 h at room temperature with gentle agitation.

Primary antisera raised in rabbit against tobacco Rubisco (prepared by S.M. Whitney) was diluted 1:4000 in TBS before incubation for 1 h with membranes at room temperature with gentle agitation. Antiserum raised against PEPC (Cat. AS09 458) was obtained from AgriSera and diluted 1:2000 with TBS. For NADP-ME and PEP-CK, synthetic peptides based on monocot amino acid sequences for each protein were synthesized by GL Biochem and antisera were raised against each peptide in rabbits. The reactive antiserum was the antigen purified for use in immunoblot analysis (GL Biochem). The NADP-ME and PEP-CK antisera were diluted in TBS 1:1000 and 1:500, respectively. All primary antisera were incubated with membranes at room temperature for 1 h with gentle agitation before washing three times with TBS. Secondary goat anti-rabbit antiserum conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Cat. NEF 812001EA, Perkin Elmer) was diluted 1:3000 in TBS and incubated with the membranes for 1 h at room temperature followed by three washes with TBS. Immunoreactive peptides were detected using the Immun-Star Western C kit (Cat. 170-5070, BioRad) and imaged using the VersaDoc.

Leaf nitrogen and carbon isotope analyses

Following gas exchange and leaf disc sampling, the remainder of the LFEL was cut and its area was measured using a leaf area meter (LI-3100A, LI-COR). The LFEL was oven-dried, weighed, then milled to a fine powder. Leaf N content was determined on the ground leaf tissue samples using a CHN analyser (LECO TruSpec, LECO Corp., MI, USA). Leaf mass per area (LMA, g m–2) was calculated as total leaf dry mass/total leaf area. Leaf N per unit area (Narea) was calculated as (mmol N g–1)×LMA (g m–2). For leaf δ13C, ground leaf samples were combusted in a Carlo Erba Elemental Analyser (Model 1108) and the released CO2 was analysed by MS. The δ13C=[(Rsample–Rstandard)/Rstandard]×1000, where Rsample and Rstandard are the 13C/12C ratio of the sample and standard (Pee Dee Belemnite), respectively. Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination based on leaf dry matter δ13C (∆DM) was calculated as described by Farquhar and Richards (1984):

| (11) |

where δa and δp are the δ13C values in the glasshouse air (assumed to be –8‰) and in the leaf bulk material, respectively.

PWUE and PNUE calculations

Photosynthetic water use efficiency (PWUE) was calculated as A (µmol m–2 s–1)/gs (mol m–2 s–1). Photosynthetic nitrogen use efficiency (PNUE) was calculated as A (µmol m–2 s–1)/leaf Narea (mmol m–2).

Plant harvest

Plants were harvested 10–11 weeks after transplanting. At harvest, leaves were separated from stems. Total leaf area was determined using a Licor LI-3100A leaf area meter. Roots were washed free of soil. Plant materials were oven-dried at 80 ºC for 48 h before dry mass (DM) was measured. Total plant DM included leaf, stem, and root DM. Leaf nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) was calculated as the ratio of total plant DM (g per plant)/total leaf N content (mg).

Statistical analysis

Growth, gas exchange, enzyme assay, and leaf nitrogen analyses were performed on 3–4 replicates per treatment combination (species×light). For species as a main effect, the relationship between various response variables and the main effect (species and light treatment) and their interactions were fitted using the linear model in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (R Core Team, 2015). Since the numbers of species within each subtype were unequal and measurements were taken on multiple individuals within a species, each unit cannot be considered as a true independent replicate. Therefore, a linear mixed effect model (lmer) was used to estimate the fixed effect associated with light treatment and subtype, where species were treated as a random variable. For each response variable, the models containing all possible fixed effects were fitted using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2013) in R. The model residues were tested for normality, and data transformation was carried out to achieve a normal distribution, if required. Significance tests were performed with a parametric bootstrap by using the ‘pbkrtest’ package in R (Halekoh and Højsgaard, 2014). Briefly, a linear mixed effect model (fitted with maximum likelihood), full and restricted models, was used as a sample to generate the likelihood ratio statistic (LRT) after 1000 bootstraps. To estimate the P-value, LRT divided by the number of degrees of freedom was assumed to be F-distributed where denominator degrees of freedom are determined by matching the first moment of reference distribution.

Results

Throughout this study, the species effect was highly significant for all parameters and generally is not described below (Table 2).

Plant growth and leaf chemistry

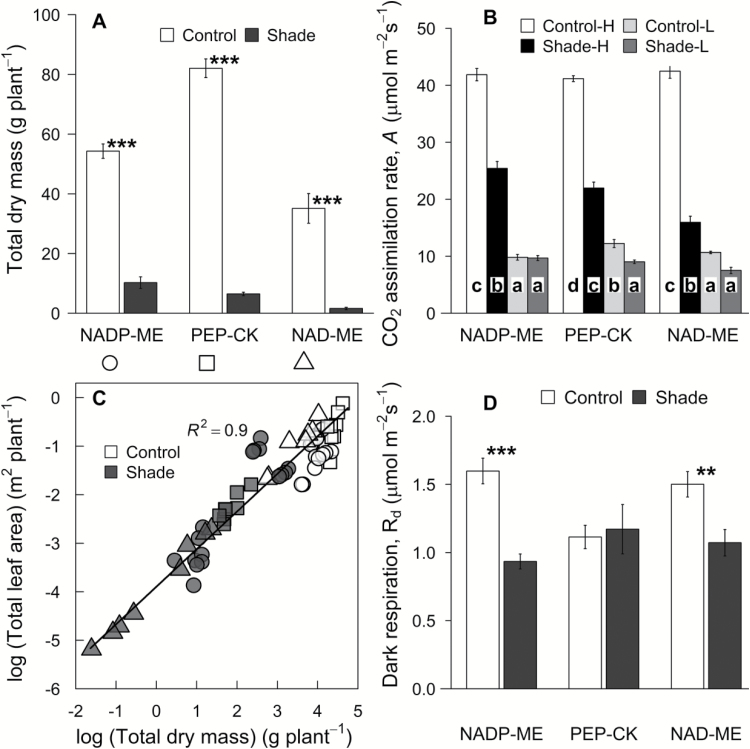

Across treatments, PEP-CK species had a higher average plant DM and total leaf area relative to NADP-ME and NAD-ME species (P<0.05; Table 2; Fig. 1A; Supplementary Table S1). Shade reduced plant DM to a greater extent in NAD-ME (–95%) and PEP-CK (–92%) relative to NADP-ME (–81%) species (Table 2; Fig. 1A; Supplementary Table S1). Total plant DM and total leaf area were linearly correlated across the species and light treatments (R2=0.9 for the log relationship) (Fig. 1C). The effect of shading on plant DM and leaf area increased linearly with shaded plant DM (R2=0.97 and 0.89, respectively). The root to shoot ratio did not vary according to subtype but was substantially reduced by shade in all species (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1). There was no significant subtype effect on LMA, leaf Nmass, or leaf Narea, while shade reduced LMA and leaf Narea (but not leaf Nmass) in most species (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Total plant dry mass and leaf area. (A) Total plant dry mass (DM), (B) CO2 assimilation rate measured at ambient [CO2], (C) relationship between the log of total leaf area and the log of total DM, and (D) dark respiration (Rd) for eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes and grown in control (full sunlight; white) or shade (16% of natural sunlight; black) environments. Each column represents the mean ±SE of subtype. For (A) and (D), statistical significance levels (t-test) for the growth condition within each subtype are shown: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. In (B), measurements were made at 2000 (HL) and 250 (LL) μmol quanta m–2 s–1 for both control and shade treatments. Letters indicate the ranking (from lowest=a) within each subtype using multiple-comparison Tukey’s post-hoc test.

Leaf gas exchange at low and high light

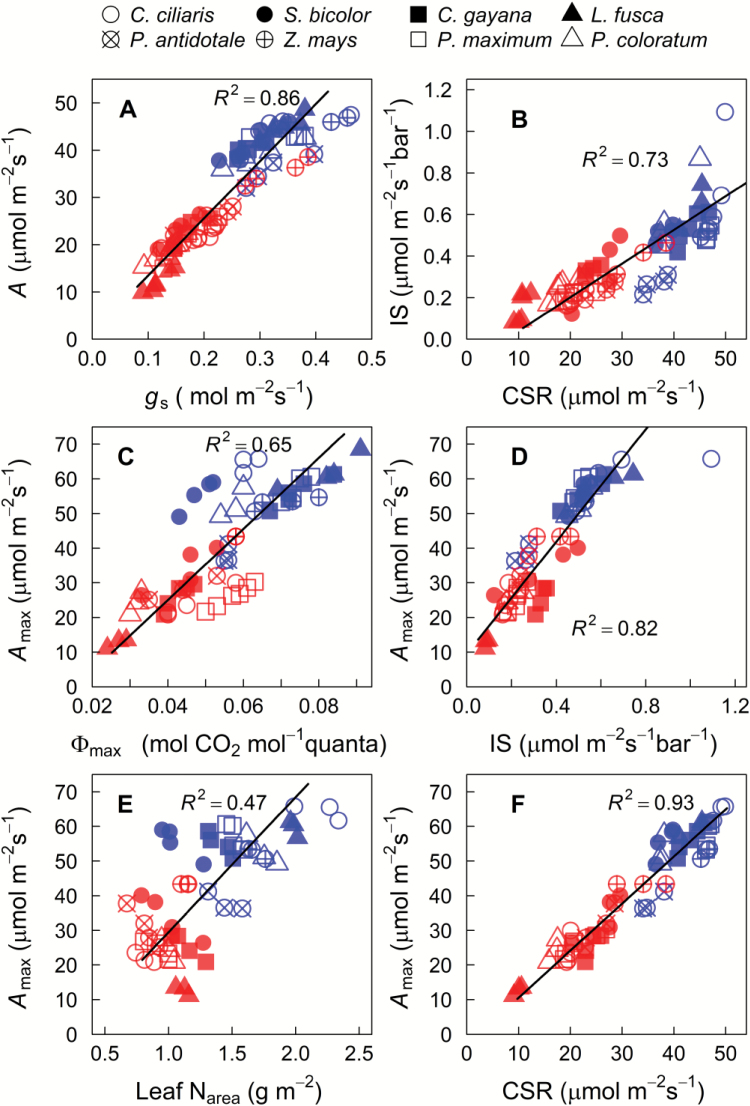

Overall, there was no significant subtype effect on CO2 assimilation rates and stomatal conductance measured at HL (Ah and gsh, respectively) and LL (Al and gsl, respectively) (P>0.05, Table 2). However, there was a significant treatment and subtype×treatment effect on both Ah and Al (P<0.05; Table 2). In particular, shade reduced Ah and Al to a greater extent in NAD-ME (–62% and –27%, respectively) relative to PEP-CK (–46% and –15%, respectively) and NADP-ME –40% and 0%, respectively) species (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, under shade, NADP-ME species had the highest and NAD-ME species had the lowest Ah and gh, indicating that photosynthesis and stomatal conductance acclimated to shade more strongly in the latter species (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Table S2). The CO2 assimilation rate was strongly correlated with stomatal conductance across all species and treatments (R2=0.86) (Fig. 2A). Consequently, Ci/Ca was constant and, together with PWUE, did not vary according to the subtype or light treatment (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Relationships among physiological and in vivo derived parameters. CO2 assimilation (Ah), stomatal conductance (gh), IS, and CSR derived from A–Ci curves measured at high light, Amax and Φmax derived from light response curves measured at saturating [CO2], and leaf Narea for eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes grown in control (full sunlight; blue) or shade (16% of natural sunlight) (red) environments. Straight lines are linear regressions for all data points.

R d did not differ between the subtypes but it was reduced by shade in NADP-ME and NAD-ME species (Fig. 1D; Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). For control plants, the Rd/A ratio (measured at growth light) was lowest in PEP-CK species; shade increased Rd/A less in NADP-ME (+158%) relative to PEP-CK (+374%) and NAD-ME (+341%) species (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). CO2 assimilation rate measured at HL, Ah, and Rd showed good linear relationships to leaf Narea across species (R2=0.59 and R2=0.54, respectively). PNUE was marginally lower (P=0.1) in NAD-ME relative to NADP-ME and PEP-CK species, and was reduced by shade mostly in NAD-ME (–28%) and PEP-CK (–19%) (Table 2; Supplementary Table S2). Leaf NUE was reduced to a greater extent in NADP-ME and NAD-ME species (–41% and –39%, respectively) relative to PEP-CK species (Table 2; Supplementary Table S1).

Photosynthetic CO2 response curves

The initial slopes (ISs) of the A–Ci curvesand CO2-saturated rates (CSRs) were estimated from measurements at HL (Supplementary Fig. S2). In control plants, the IS and CSR did not vary with subtypes, but were reduced by shade to a greater extent in NAD-ME (–77% for IS and –64% for CSR) than PEP-CK (–49% for IS and CSR) and NADP-ME species (–46% for IS and –39% for CSR) (Tables 2, 3). Consequently, CSR of shaded plants was lowest in NAD-ME, intermediate in PEP-CK, and highest in NADP-ME species (Tables 2, 3). There was a strong linear relationship between IS and CSR irrespective of treatment and subtype (R2=0.73) (Fig. 2B).

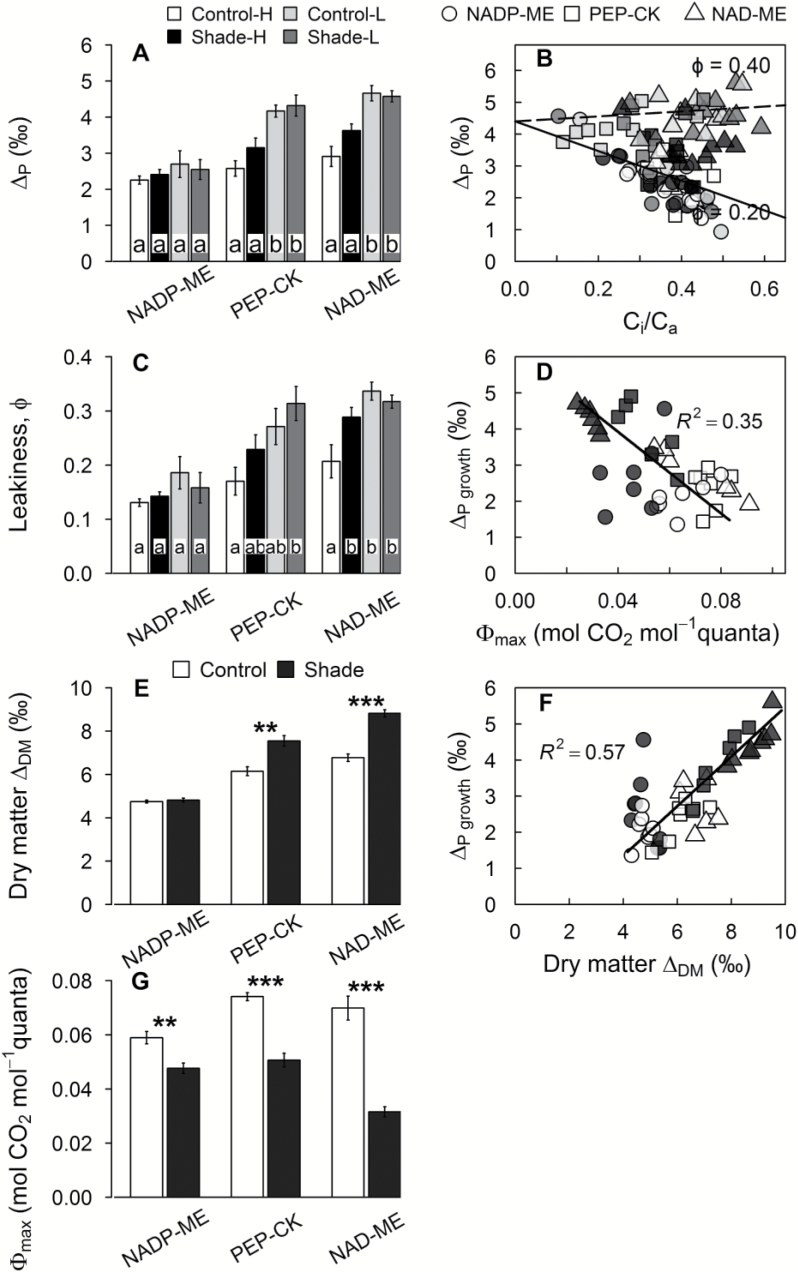

Photosynthetic light response curves

The light-saturated photosynthesis rate, Amax, and photosynthetic quantum yield, Фmax, were estimated from the light response curves of photosynthesis measured at saturating CO2 (Supplementary Fig. S3). In control plants, Amax and Фmax did not vary with subtypes (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 3G). Shade reduced Amax and Фmax to a greater extent in NAD-ME species (–68% and –55%, respectively) than PEP-CK (–54% and –32%, respectively) and NADP-ME (–39% and –19%, respectively) species (Tables 2, 3). Consequently, Фmax was lower in shaded NAD-ME species relative to their NADP-ME and PEP-CK counterparts (P<0.05), which indicates differential shade acclimation of photosynthetic capacity and quantum efficiency among the C4 subtypes. In control plants, the curvature (θ) was highest in NADP-ME (0.81) and lowest in NAD-ME species (0.53) (P<0.05) (Tables 2, 3). When all data were considered, Amax was well correlated with Фmax, IS, CSR, and leaf Narea (Fig. 2C–F).

Fig. 3.

The CCM efficiency parameters. (A) Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (∆P) measured concurrently with leaf gas exchange, (B) carbon isotope discrimination against the ratio of intercellular [CO2] to ambient [CO2] (Ci/Ca), (C) leakiness (ϕ) at measured light (h or l), (D) ∆P measured at growth light (∆growth) against Фmax, (E) ∆DM calculated from leaf dry matter δ13C, (F) ∆P measured at growth light (∆Pgrowth) against ∆DM, and (G) and maximum quantum yield of PSII, Фmax, for C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes grown in control (full sunlight; white) or shade (16% of natural sunlight; black) environments. Each column represents the mean ±SE of subtype. Statistical significance levels (t-test) for the growth condition within each subtype are shown: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

Carbon isotope discrimination

Concurrent measurements of 13CO2/12CO2 discrimination and leaf gas exchange showed that photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination, ∆P, was independent of the C4 subtype at HL (Table 2). ∆P tended to be lower in NADP-ME species relative to the other two subtypes, but differences were not significant, except when compared with the control plants measured at HL (Table 2; Supplementary Table S3). For NADP-ME species, ∆P was unchanged by either LL or shade, while ∆P increased in PEP-CK and NAD-ME species in response to both LL and shade (22–37%) (Fig. 3A; Supplementary Table S3).

Leakiness (ϕ) ranged between 0.15 and 0.35 across the C4 grasses and light treatments (Fig. 3B, C). For shaded plants measured at HL, NAD-ME species had higher leakiness (0.29) than NADP-ME species (0.14) (Supplemetary Table S3). Overall, NAD-ME species exhibited increased ϕ at LL and in the shade environment (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Table S3).

Photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination derived from bulk leaf δ13C values, ∆DM, was significantly lower in NADP-ME species relative to the other two subtypes (P<0.05) (Table 2; Supplementary Table S3). Shade increased ∆DM in NAD-ME and PEP-CK species only (+30% and +22%, respectively) (Fig. 3E; Table 2; Supplementary Table S3).

There was a strong linear relationship between photosynthetic discrimination measured at growth light, ∆growth, and ∆DM (R2=0.56) (Fig. 3F). This relationship had an x-intercept of 0.9‰, which reflects the difference between ∆growth and ∆DM due to time-integrated changes in ambient 13CO2/12CO2 and post-photosynthetic fractionation. The good fit between ∆growth and ∆DM suggests that leaf δ13C is a good predictor of ∆growth, and perhaps Ci/Ca (PWUE) for C4 grasses when changes are caused by a difference in light intensity. In addition, there was a significant, negative linear relationships between Фmax and ∆growth (R2=0.35) (Fig 3D).

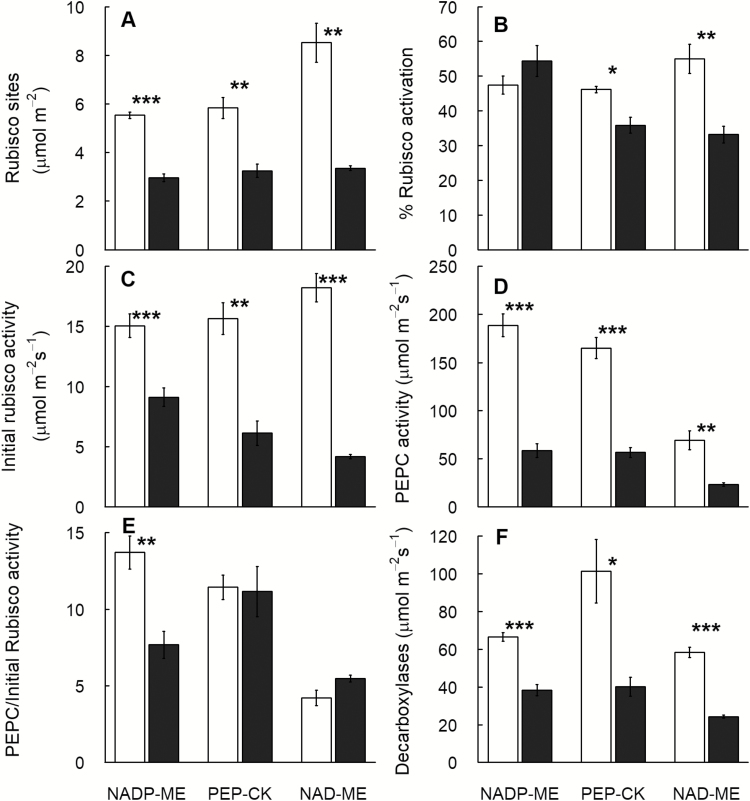

Activity of photosynthetic enzymes

Control NAD-ME plants had the highest leaf content of Rubisco sites (P<0.05) (Fig. 4A; Table 2: Supplemetnary Table S4). Rubisco activation decreased significantly in NAD-ME (–40%) and PEP-CK (–22%) species, while it increased by ~15% in NADP-ME species (subtype×light P=0.07) (Fig. 4A, B; Table 2; Supplementary Table S4). Consequently, initial Rubisco activity did not differ according to the C4 subtype (P>0.05), and was reduced to a greater extent in NAD-ME relative to the PEP-CK and NADP-ME species under shade in all C4 grasses (subtype×treatment P<0.08) (Fig. 4C; Table 2; Supplementary Table S4). Soluble protein content decreased under shade by 12–67% depending on the species but not the subtype (Table 2; Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 4.

Shade acclimation of photosynthetic enzymes in C4 subtypes. (A) Rubisco sites, (B) % Rubisco activation, (C) Initial Rubisco activity, (D) PEPC activity, (E) PEPC to initial Rubisco activity ratio, and (F) decarboxylases activity for eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes and grown in control (full sunlight; white) or shade (16% of natural sunlight; black) environments. Each column represents the mean ±SE of subtype. Statistical significance levels (t-test) for the growth condition within each subtype are shown: *P<0.05; **P<0.01; ***P<0.001.

In general, shade reduced PEPC activity by 49–84% in the C4 grasses. PEPC activity was higher in control NADP-ME plants and decreased to a lesser extent in NAD-ME (66%) than in NADP-ME (69%) and PEP-CK (65%) species (Fig. 4D; Table 2; Supplementary Table S4). Consequently, shade reduced the ratio of PEPC to initial Rubisco activity in NADP-ME (–44%) but not in PEP-CK (–3%) species, while this ratio tended to increase in NAD-ME species (+30%) (Fig. 4E; Supplementary Table S4,).

There was a significant relationship between the PEPC/initial Rubisco activity ratio and ∆DM (P<0.05), and this relationship was stronger in shade (R2=0.49) than in control (R2=0.40) plants. In contrast, PEPC/initial Rubisco activity showed a weaker relationship to ∆growth (R2=0.23) irrespective of treatment and subtype.

Activities of NADP-ME, PEP-CK, and NAD-ME enzymes were dominant in their respective subtype; however, substantial PEP-CK activity (6–25 µmol m–2 s–1) was measured in NADP-ME and NAD-ME species (Supplementary Table S4). Shade reduced the activity of NADP-ME, PEP-CK, and NAD-ME by 35–60, 52–64, and 49–57%, respectively (P<0.05). Shade also reduced the activity of total decarboxylases by 25–64% (P<0.05); the reduction was lower in NADP-ME (42%) relative to PEP-CK (60%) and NAD-ME (65%) species (Fig. 4F; Table 2; Supplementary Table S4).

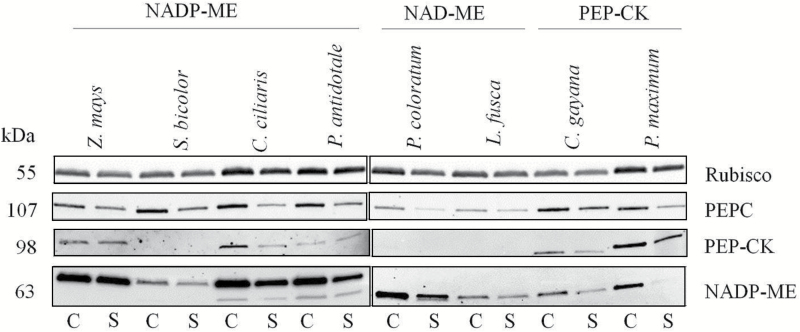

The detectability of enzyme activity was corroborated by immunodetection of the corresponding protein for all the photosynthetic enzymes assayed, except for NAD-ME where a suitable antibody was not available during this study (Fig. 5). Rubisco and PEPC proteins were detected in all species and treatments. Surprisingly, NADP-ME protein was detected in all C4 species, including NAD-ME and PEP-CK. This may be attributed to cross-reaction with a non-photosynthetic isomer of NADP-ME or NAD-ME proteins (Fig. 5). PEP-CK protein was strongly detectable in Panicum maximum and to a lesser extent in Chloris gayana, although C. gayana had the highest PEP-CK activity (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S4). In addition, PEP-CK protein was detected in three NADP-ME species, but not in Sorghum bicolor, reflecting well the trends in PEP-CK activity (Fig. 5; Supplementary Table S4).

Fig. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of photosynthetic enzymes. Immunoblot analysis for the photosynthetic proteins Rubisco, PEPC, PEP-CK, and NADP-ME extracted from leaves of eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes in control (C) or shade (S) environments. Loaded volumes varied between 4 μl and 15 μl in order to normalize the protein content to a common leaf area. Because of the small gel size, a limited number of samples (8–9) was loaded on an individual gel. Finally, all immunoblots of the studied protein and species were arranged in a composite figure. For uniform visualization, gamma settings of individual images were adjusted. A protein ladder was used for individual immunoblots; for simplicity, band size is referred to numerically.

Discussion

C4 photosynthesis is thought to be less plastic in response to shade than C3 photosynthesis due to its complex anatomy and biochemistry (Sage and McKown, 2006). Yet, some studies found similar photosynthetic responses to LL in C3 and C4 plants (Tazoe et al., 2006, 2008; Pengelly et al., 2010). These studies have focused on the response of selected C4 species to short-term changes in irradiance (Tazoe et al., 2008; Pengelly et al., 2010; Ubierna et al., 2013; Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014a, b) or long-term adaptation to growth under LL (Kromdijk et al., 2008, 2010; Tazoe et al., 2008; Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014b). However, there is limited information about how LL responses differ across the C4 subtypes. Here, we present the first study comparing the short- and long-term responses to LL of C4 grasses with different biochemical subtypes. We hypothesized that (i) LL (short and long term) will compromise the CCM efficiency to a greater extent in NAD-ME than in PEP-CK or NADP-ME grasses due to a greater increase in leakiness (ϕ) in the former subtype; and (ii) shade will cause a greater photosynthetic acclimation in NAD-ME grasses than in NADP-ME and PEP-CK counterparts by virtue of their higher leaf N and Rubisco content. To evaluate these hypotheses, we grew eight C4 grasses belonging to three biochemical subtypes (NADP-ME, NAD-ME, and PEP-CK) under shade (16% sunlight) or control (full sunlight) conditions, and subsequently measured their photosynthetic characteristics under both LL and HL. Our results supported both hypotheses and demonstrated that LL compromised the CCM efficiency and photosynthetic quantum yield to a greater extent in NAD-ME relative to PEP-CK and NADP-ME species.

Low light compromised the CCM efficiency most in NAD-ME followed by PEP-CK, but not in NADP-ME grasses

For the operational CCM, the C4 cycle must be faster than the C3 cycle (i.e. PEPC/initial Rubisco activity ratio >1) to concentrate CO2 inside the BSCs, some of which will inevitably leak back out to the MCs. In the short term, LL may compromise CCM efficiency by affecting the activity of the C3 cycle (e.g. Rubisco) more significantly than that of the C4 cycle (e.g. PEPC) and, hence, increasing ∆P, ϕ, and Фmax. Under LL, A is low and CO2 evolved during respiration can make an important contribution to the total CO2 concentration inside the BSCs. Larger Rd/A ratios under LL can potentially lead to higher ∆P. Increased ∆P due to respiratory CO2 does not involve an energy cost for the CCM but may lead to an overestimation of ϕ independently of Фmax. Long-term acclimation to LL may act to optimize CCM efficiency by reversing the negative short-term effects of LL (Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014a). Hence, we used the metrics PEPC/initial Rubisco activity, Rd/A, ϕ, and Фmax to evaluate the effects of LL during measurements and growth on the CCM efficiency of the various C4 subtypes. Consequently, increased ϕ, PEPC/initial Rubisco activity, and Rd/A can be interpreted as a less efficient photosynthetic process. Assuming that bundle sheath conductance does not change with irradiance, increased ∆P and ϕ can be interpreted as a less efficient CCM and an indication of imbalance between the C3 and C4 cycles (von Caemmerer, 2000).

Response of NADP-ME grasses to LL

In the NADP-ME grasses, ∆P, ∆DM, and ϕ were not significantly impacted by LL during either measurement or growth (Fig. 3A, C, E), suggesting that in this subtype, the co-ordination between the C3 and C4 cycles was largely maintained despite changes in the light environment. Our results are in agreement with previous reports that ∆P was insensitive to LL during the measurements for NADP-ME species (Henderson et al., 1992; Kubásek et al., 2007; Cousins et al., 2008) as well as ∆DM being insensitive to growth under shade in NADP-ME Zea mays (Sharwood et al., 2014). NADP-ME species grown under shade had lower PEPC/initial Rubisco activity (–44%) and higher Rd/A (+158% at growth light) than the control plants. Decreased PEPC/initial Rubisco activity is expected to reduce ∆P, ∆DM, and ϕ, while increased Rd/A will have the opposite effect under shade. The combined opposing effects may explain the insensitivity of ∆P, ∆DM, and ϕ in response to the shade environment. In line with this conclusion, NADP-ME species showed the lowest reduction in Фmax (–19%), and it is likely that the contribution from photorespiration was negligible in the low-O2-evolving BSC chloroplasts of NADP-ME species (Ghannoum et al., 2005). Previous work describing the shade acclimation of the NADP-ME of Z. mays suggested that this species reduced the ATP cost of the CCM under shade by reducing the PEPC activity more than the C3 cycle activity, which resulted in low ϕ values (Bellasio and Griffiths, 2014a). Our findings support this argument by providing direct measurements of in vitro C4 and C3 cycle enzymes as well as Фmax. This argument is also supported by the modelling approach of Wang et al. (2014) who suggested that the NADP-ME biochemical pathway is favoured at LL. In contrast to our results, differential responses of C4 and C3 cycle enzymes were reported in earlier studies with NADP-ME species (Sugiyama et al., 1984; Ward and Woolhouse, 1986a; Sharwood et al., 2014). This discrepancy may be related to differences in the intensity of the shade treatment used. In addition, these studies considered total (rather than initial) Rubisco activity for calculating the PEPC/Rubisco activity ratio.

It is worth noting that, in addition to NADP-ME decarboxylase activity, Z. mays and Cenchrus ciliaris showed significant activity of PEP-CK decarboxylase (16–25 µmol m–2 s–1), while S. bicolor and Panicum antidotale appeared as true NADP-ME types. Without considering cytosolic resistance of BSCs to CO2, Wang et al. (2014) suggested the possibility of higher leakiness in the C4 photosynthesis model with mixed decarboxylase pathways. This was not validated in our study. Bellasio and Griffiths (2014c) also suggested that the engagement of the secondary PEP-CK pathway in an NADP-ME species enables the CCM to regulate an optimal BSC [CO2] under changing light conditions. These predictions were indirectly validated in our study. Under LL, Z. mays showed higher ∆P and ϕ but similar Фmax relative to the other two NADP-ME species, P. antidotale and S. bicolor (Supplementary Table S4). However, the link between ∆P, CCM efficiency, and PEP-CK activity as a secondary decarboxylase in NADP-ME species requires further investigation.

Response of PEP-CK and NAD-ME grasses to LL

PEP-CK and NAD-ME plants had larger ∆DM under shade relative to the control condition (Fig. 3E). Previous studies have shown similar ∆DM responses to shade across the C4 subtypes (Buchmann et al., 1996; Tazoe et al., 2006). In PEP-CK and NAD-ME grasses, instantaneous measurements of ∆P and ϕ increased at LL, and the difference between the light treatments was highly significant when the comparison was made between control and shade plants measured under their respective growth irradiance (Fig. 3A, C). These results indicate that LL resulted in a less efficient CCM in PEP-CK and NAD-ME grasses. Additionally, the relative increase in ϕ from HL to LL was larger for control (+60%) than shade (+12%) plants. This is in line with Tazoe et al. (2008) and suggests that a degree of acclimation to the shade condition mitigated the negative effects of LL observed in response to short-term light changes during measurements. Our results with PEP-CK and NAD-ME grasses are in agreement with previous reports of increased ∆P and ϕ with short-term exposure to LL (Henderson et al., 1992; Cousins et al., 2008).

In NAD-ME species, shade increased the PEPC/initial Rubisco activity (+30%) and Rd/A (+341% at growth light) and decreased Фmax (–55%). Species of the NAD-ME subtype possess significant PSII activity in the BSC (Ghannoum et al., 2005), and hence potentially high [O2]. PEP-CK species exhibited intermediate responses to shade relative to the other two subtypes. In PEP-CK species, the PEPC/initial Rubisco activity ratio was not affected by shade, but the Rd/A ratio was larger (+374%) in shade than in control plants (Supplementary Table S2). Further, the reduction of Фmax under shade was intermediate in PEP-CK species (–32%) relative to NADP-ME (–19%) and NAD-ME (–55%). We also have evidence that PEP-CK species possess significant PSII activity in BSCs (Pinto, 2015). Accordingly, ∆P, ∆DM, and ϕ increased under shade in PEP-CK species to a similar extent relative to NAD-ME counterparts (Fig. 3A, C, E). Thus, in line with the first hypothesis, our results demonstrated that LL compromised the CCM efficiency of NAD-ME species more than that of PEP-CK species, while CCM efficiency was largely maintained in NADP-ME species under LL.

Shade induced larger photosynthetic down-regulation in NAD-ME relative to NADP-ME and PEP-CK species

In the current study, shade down-regulated Ah and light-saturated photosynthesis, Amax, in NAD-ME (–68%) to a greater extent than in PEP-CK (–54%) and NADP-ME (–39%) species, indicating stronger photosynthetic acclimation to shade in the former subtype (Table 3). Shade equally reduced PEPC activity in all the C4 subtypes (–68%), while Rubisco sites and activation were more profoundly reduced in NAD-ME (–60% and –40%, respectively) relative to the PEP-CK (–48% and –22%, respectively) and NADP-ME (–47% and +15%, respectively) species (Supplementary Table S4). Similar large reductions in Rubisco content and activity (>55%) were reported in studies using C3 species (Evans, 1988). In shade-grown C4 species, inconsistent changes in Rubisco content and activity have been observed (Winter et al., 1982; Ward and Woolhouse, 1986a, b; Tazoe et al., 2006), with an average reduction of 29% (Sage and McKown, 2006). A relevant study by Ward and Woolhouse (1986a) subjecting C4-NADP-ME grasses to deep shade reported a greater reduction in Rubisco activity in species from the open habitat (34%) relative to the shade habitat (3%). Likewise, NAD-ME species generally originate from relatively more open habitats than NADP-ME and PEP-CK species (Vogel et al., 1986; Hattersley, 1992; Schulze et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2012). In addition, similar to the C3 species, NAD-ME grasses may have a greater N flexibility by having higher leaf N relative to NADP-ME and PEP-CK counterparts.

Table 3.

Parameters derived from A–Ci and light response curves for eight C4 grasses grown under control (full sunlight) or shade (16% of natural sunlight) environments

| Parameter | Treatment | Subtype | C4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NADP-ME | PEP-CK | NAD-ME | |||

| IS at HL (µmol m–2 s–1 bar–1) | Control | 0.5 ± 0.06 a | 0.52 ± 0.02 a | 0.62 ± 0.06 a | 0.53 ± 0.03 |

| Shade | 0.27 ± 0.03 a | 0.27 ± 0.02 a | 0.2 ± 0.02 a | 0.25 ± 0.02 | |

| % change | –46 | –49 | –77 | –54 | |

| CSR at HL (µmol m–2 s–1) | Control | 42 ± 1 a | 45 ± 1 a | 41 ± 1 a | 43 ± 1 |

| Shade | 25 ± 1 b | 23 ± 1 ab | 15 ± 1 a | 21 ± 1 | |

| % change | –39 | –49 | –64 | –50 | |

| IS/CSR at HL (×103) | Control | 12 ± 1 a | 12 ± 0 a | 15 ± 1 a | 12 ± 1 |

| Shade | 10 ± 1 a | 12 ± 1 a | 13 ± 1 a | 12 ± 1 | |

| % change | –12 | 1 | –9 | –6 | |

| A max (µmol m–2 s–1) | Control | 53 ± 3 a | 57 ± 1 a | 58 ± 2 a | 55 ± 1 |

| Shade | 32 ± 2 a | 26 ± 1 a | 18 ± 3 a | 28 ± 1 | |

| % change | –39 | –54 | –68 | 50 | |

| Maximum quantum yield (Фmax) (mol mol–1) | Control | 0.06 ± 0 a | 0.07 ± 0 a | 0.07 ± 0 a | 0.07 ± 0 |

| Shade | 0.05 ± 0 b | 0.05 ± 0 b | 0.03 ± 0 a | 0.05 ± 0 | |

| % change | –19 | –32 | –55 | –32 | |

| Curvature (θ) of light response curve | Control | 0.81 ± 0.04 b | 0.57 ± 0.03 ab | 0.53 ± 0.04 a | 0.66 ± 0.03 |

| Shade | 0.61 ± 0.04 a | 0.64 ± 0.05 a | 0.64 ± 0.05 a | 0.62 ± 0.03 | |

| % change | –25 | 12 | 19 | –6 | |

Values are means ±SE (n=3–4). The ranking (from lowest=a) of subtypes within each single row using multiple-comparison Tukey’s post-hoc test. Values followed by the same letter are not significantly different at the 5% level. Significant fold changes are shown in bold (P<0.05).

Reduced Rubisco content is a common photosynthetic acclimation response to shade allowing optimal nitrogen allocation for maximal light harvesting (Boardman, 1977; Hikosaka and Terashima, 1995; Evans and Poorter, 2001; Walters, 2005). Consequently, lower Rubisco activity and activation may indicate a shift in photosynthetic limitation from Rubisco (sun leaves) to electron transport (shade leaves) (Evans, 1988; Evans and Poorter, 2001). Under shade, NAD-ME species had lower Фmax relative to NADP-ME and PEP-CK counterparts (Fig. 3). This difference may be attributed to a greater inefficiency of the NAD-ME CCM, especially under shade as argued above. It could also be attributed to inherent inefficiencies of the light conversion apparatus in the NAD-ME subtype due to the burden of operating two fully fledged linear electron transport systems with granal chloroplasts in both MCs and BSCs. This is not the case for the NADP-ME subtype, and somewhat intermediate for the PEP-CK subtype (Ghannoum et al., 2005, 2011). Taken together, these findings support our second hypothesis stating that larger photosynthetic reduction and acclimation in NAD-ME species is associated with their lower Rubisco activation and lower quantum efficiency relative to PEP-CK and NADP-ME species.

Whole-plant implications of differential shade acclimation among the C4 subtypes

In the current study, CO2 assimilation at growth light was equally reduced in NAD-ME (–81%), PEP-CK (–79%), and NADP-ME (–76%) species. However, total leaf area and plant DM were more profoundly reduced in NAD-ME (–92% and –95%, respectively) than in PEP-CK (–81% and –98%, respectively) and NADP-ME (–73% and –81%, respectively) species. In addition to reduced leaf area, the larger reduction in plant DM for NAD-ME and PEP-CK species could also be attributed to reduced CCM efficiency and Фmax. Further, the Rd/A ratio increased to a greater extent in NAD-ME and PEP-CK (~3.5-fold) than in NADP-ME species (1.6-fold) under shade, which may result in a greater C loss in these two subtypes. Taken together, these findings suggest that shade may favour NADP-ME species due to their efficient CCM and quantum yield, and lower photosynthetic down-regulation and lower increase in Rd/A relative to NAD-ME and PEP-CK species.

This conclusion is supported by ecological observations. NAD-ME species are preferentially found in open and arid habitats relative to the other two C4 subtypes (Osmond et al., 1982; Vogel et al., 1986; Hattersley, 1992; Schulze et al., 1996; Liu et al., 2012). On the one hand, most of the understorey C4 grasses belong to the NADP-ME subtypes, such as Setaria species (Schulze et al., 1996), Paspalum species (Ward and Woolhouse, 1986b; Klink and Joly, 1989; Firth et al., 2002), and Microstegium vimineum (Barden, 1987). Moreover, NADP-ME species form dense canopy crops such as maize, Sorghum, Miscanthus, and sugarcane where most leaves are shaded (Sage, 2014).

It should be noted that a different light spectrum affects CCM efficiency in C4 photosynthesis (Sun et al., 2012). The light spectrum may vary in natural shade settings due to growth season, canopy compositions, and architecture (Ross et al., 1986; Messier et al., 1998). Therefore, an interaction effect between subtype and light spectral composition cannot be ignored, and further investigations are warranted.

Conclusion

Using C4 grass from three biochemical subtypes and grown under full sunlight and shade (16% of full sunlight) conditions equivalent to the light environment prevailing in lower crop canopies or forest understorey, this study demonstrated that NAD-ME and to a lesser extent PEP-CK species were generally outperformed by NADP-ME species under shade. This response was underpinned by a more efficient CCM and quantum yield in NADP-ME. These findings were corroborated by in vivo and in vitro measurements of C3 and C4 cycle enzymes, maximum quantum yield of PSII (Фmax), photosynthetic carbon isotope discrimination (ΔP), leaf dry matter δ13C, and total plant dry mass. Future research is needed to quantify the impact of respiration and photorespiration on carbon isotope discrimination (∆P) in the three biochemical subtypes of C4 photosynthesis, as well as the significance of the secondary PEP-CK decarboxylase on photosynthetic responses to shade.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at JXB online.

Table S1. Summary of plant growth parameters.

Table S2. Summary of gas exchange parameters.

Table S3. Summary of carbon isotope discrimination parameters.

Table S4. Summary of biochemical parameters.

Table S5. Definitions and units for variables described in the text.

Fig. S1. Glasshouse growth conditions.

Fig. S2. Photosynthetic CO2 response curves (A–Ci) of C4 grasses.

Fig. S3. Photosynthetic light response curves for C4 grasses.

Fig. S4. Sensitivity of leakiness at low light

Appendix S1. Leakiness calculations at low light

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Craig Barton for support with the TDL measurements, and Mr Burhan Amiji for support with the setting up of the shade structure and data loggers. We also thank Fiona Koller for assistance in biochemical assays. BVS was supported by a postgraduate research award funded by the Australian Research Council and the Hawkesbury Institute for the Environment at Western Sydney University. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council: DP120101603 (OG and SMW), DE130101760 (RES), and CE140100015 (OG and SMW).

References

- Ashton AR, Burnell JN, Furbank RT, Jenkins CLD, Hatch MD. 1990. Enzymes of C4 photosynthesis. In: Lea PJ, ed. Methods in plant biochemistry. Volume 3. Enzymes in primary metabolism. London: Academic Press, 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barden LS. 1987. Invasion of Microstegium vimineum (Poaceae), an exotic, annual, shade-tolerant, C4 grass, into a North Carolina floodplain. American Midland Naturalist 118, 40–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2013. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4. R Package Version 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014a Acclimation of C4 metabolism to low light in mature maize leaves could limit energetic losses during progressive shading in a crop canopy. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3725–3736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014b Acclimation to low light by C4 maize: implications for bundle sheath leakiness. Plant, Cell and Environment 37, 1046–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellasio C, Griffiths H. 2014c The operation of two decarboxylases (NADP-ME and PEP-CK), transamination and partitioning of C4 metabolic processes between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells allows light capture to be balanced for the maize C4 pathway. Plant Physiology 164, 466–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björkman O. 1981. Responses to different quantum flux densities. In: Lange OL, Nobel PS, Osmond CB, Ziegler H, eds. Physiological plant ecology I: responses to the physical environment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 57–107. [Google Scholar]

- Björkman O, Holmgren P. 1966. Photosynthetic adaptation to light intensity in plants native to shaded and exposed habitats. Physiologia Plantarum 19, 854–859. [Google Scholar]

- Boardman NK. 1977. Comparative photosynthesis of sun and shade plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology 28, 355–377. [Google Scholar]

- Bond WJ, Midgley GF. 2012. Carbon dioxide and the uneasy interactions of trees and savannah grasses. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 367, 601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RH. 1999. Agronomic implications of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, eds. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press, 473–507. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann N, Brooks JR, Rapp KD, Ehleringer JR. 1996. Carbon isotope composition of C4 grasses is influenced by light and water supply. Plant, Cell and Environment 19, 392–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins AB, Badger MR, von Caemmerer S. 2008. C4 photosynthetic isotope exchange in NAD-ME- and NADP-ME-type grasses. Journal of Experimental Botany 59, 1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards EJ, Osborne CP, Strömberg CA, et al. 2010. The origins of C4 grasslands: integrating evolutionary and ecosystem science. Science 328, 587–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J, Björkman O. 1977. Quantum yields for CO2 uptake in C3 and C4 plants: dependence on temperature, CO2, and O2 concentration. Plant Physiology 59, 86–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer JR, Cerling TE, Helliker BR. 1997. C4 photosynthesis, atmospheric CO2, and climate. Oecologia 112, 285–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehleringer J, Pearcy RW. 1983. Variation in quantum yield for CO2 uptake among C3 and C4 plants. Plant Physiology 73, 555–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR. 1988. Acclimation by the thylakoid membranes to growth irradiance and the partitioning of nitrogen between soluble and thylakoid proteins. Functional Plant Biology 15, 93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Poorter H. 2001. Photosynthetic acclimation of plants to growth irradiance: the relative importance of specific leaf area and nitrogen partitioning in maximizing carbon gain. Plant, Cell and Environment 24, 755–767. [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Sharkey TD, Berry JA, Farquhar GD. 1986. Carbon isotope discrimination measured concurrently with gas exchange to investigate CO2 diffusion in leaves of higher plants. Functional Plant Biology 13, 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. 1983. On the nature of carbon isotope discrimination in C4 species. Functional Plant Biology 10, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA. 2012. Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 1221–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Richards RA. 1984. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Functional Plant Biology 11, 539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Firth DJ, Jones RM, McFadyen LM, Cook BG, Whalley RDB. 2002. Selection of pasture species for groundcover suited to shade in mature macadamia orchards in subtropical Australia. Tropical Grasslands 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Furbank RT. 2011. Evolution of the C4 photosynthetic mechanism: are there really three C4 acid decarboxylation types?Journal of Experimental Botany 62, 3103–3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O, Evans JR, Chow WS, Andrews TJ, Conroy JP, von Caemmerer S. 2005. Faster Rubisco is the key to superior nitrogen-use efficiency in NADP-malic enzyme relative to NAD-malic enzyme C4 grasses. Plant Physiology 137, 638–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum O, Evans JR, von Caemmerer S. 2011. Nitrogen and water use efficiency of C4 plants. In: Raghavendra AS, Sage RF, eds. C4 photosynthesis and related CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez M, Gracen VE, Edwards GE. 1974. Biochemical and cytological relationships in C4 plants. Planta 119, 279–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halekoh U, Højsgaard S. 2014. A Kenward–Roger approximation and parametric bootstrap methods for tests in linear mixed models—the R package pbkrtest. Journal of Statistical Software 59, 1–32.26917999 [Google Scholar]

- Hatch MD. 1987. C4 photosynthesis: a unique blend of modified biochemistry, anatomy and ultrastructure. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 895, 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW. 1982. δ13 Values of C4 types in grasses. Functional Plant Biology 9, 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- Hattersley PW. 1992. C4 photosynthetic pathway variation in grasses (Poaceae): its significance for arid and semi-arid lands. In: Chapman GP, ed. Desertified grasslands: their biology and management. London: Academic Press, 181–212. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson SA, Caemmerer SV, Farquhar GD. 1992. Short-term measurements of carbon isotope discrimination in several C4 species. Functional Plant Biology 19, 263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K, Terashima I. 1995. A model of the acclimation of photosynthesis in the leaves of C3 plants to sun and shade with respect to nitrogen use. Plant, Cell and Environment 18, 605–618. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins CL, Burnell JN, Hatch MD. 1987. Form of inorganic carbon involved as a product and as an inhibitor of C4 acid decarboxylases operating in C4 photosynthesis. Plant Physiology 85, 952–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R, Edwards GE. 1999. The biochemistry of C4 photosynthesis. In: Sage RF, Monson RK, eds. C4 plant biology. San Diego: Academic Press, 49–87. [Google Scholar]

- Klink CA, Joly CA. 1989. Identification and distribution of C3 and C4 grasses in open and shaded habitats in Sao Paulo state, Brazil. Biotropica 21, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Koteyeva NK, Voznesenskaya EV, Edwards GE. 2015. An assessment of the capacity for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase to contribute to C4 photosynthesis. Plant Science 235, 70–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Griffiths H, Schepers HE. 2010. Can the progressive increase of C4 bundle sheath leakiness at low PFD be explained by incomplete suppression of photorespiration?Plant, Cell and Environment 33, 1935–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kromdijk J, Schepers HE, Albanito F, Fitton N, Carroll F, Jones MB, Finnan J, Lanigan GJ, Griffiths H. 2008. Bundle sheath leakiness and light limitation during C4 leaf and canopy CO2 uptake. Plant Physiology 148, 2144–2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubásek J, Setlík J, Dwyer S, Santrůcek J. 2007. Light and growth temperature alter carbon isotope discrimination and estimated bundle sheath leakiness in C4 grasses and dicots. Photosynthesis Research 91, 47–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leegood RC, Walker RP. 2003. Regulation and roles of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in plants. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 414, 204–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Edwards EJ, Freckleton RP, Osborne CP. 2012. Phylogenetic niche conservatism in C4 grasses. Oecologia 170, 835–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messier C, Parent S, Bergeron Y. 1998. Effects of overstory and understory vegetation on the understory light environment in mixed boreal forests. Journal of Vegetation Science 9, 511–520. [Google Scholar]

- Mook WG, Bommerson JC, Staverman WH. 1974. Carbon isotope fractionation between dissolved bicarbonate and gaseous carbon dioxide. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 22, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ögren E, Evans JR. 1993. Photosynthetic light–response curves. Planta 189, 182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ort DR, Merchant SS, Alric J, et al. 2015. Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 112, 8529–8536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osmond CB, Winter K, Ziegler H. 1982. Functional significance of different pathways of CO2 fixation in photosynthesis. In: Lange PDOL, Nobel PPS, Osmond PCB, Ziegler PDH, eds. Physiological plant ecology II. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 479–547. [Google Scholar]

- Pearcy RW, Tumosa N, Williams K. 1981. Relationships between growth, photosynthesis and competitive interactions for a C3 and C4 plant. Oecologia 48, 371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengelly JJ, Sirault XR, Tazoe Y, Evans JR, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2010. Growth of the C4 dicot Flaveria bidentis: photosynthetic acclimation to low light through shifts in leaf anatomy and biochemistry. Journal of Experimental Botany 61, 4109–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengelly JJ, Tan J, Furbank RT, von Caemmerer S. 2012. Antisense reduction of NADP-malic enzyme in Flaveria bidentis reduces flow of CO2 through the C4 cycle. Plant Physiology 160, 1070–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto H. 2015. Resource use efficiency of C4 grasses with different evolutionary origins. PhD Thesis, University of Western Sydney, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto H, Sharwood RE, Tissue DT, Ghannoum O. 2014. Photosynthesis of C3, C3–C4, and C4 grasses at glacial CO2. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3669–3681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porra RJ, Thompson WA, Kriedemann PE. 1989. Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 975, 384–394. [Google Scholar]

- R CoreTeam 2015. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Ross MS, Flanagan LB, Roi GHL. 1986. Seasonal and successional changes in light quality and quantity in the understory of boreal forest ecosystems. Canadian Journal of Botany 64, 2792–2799. [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF. 2014. Stopping the leaks: new insights into C4 photosynthesis at low light. Plant, Cell and Environment 37, 1037–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, McKown AD. 2006. Is C4 photosynthesis less phenotypically plastic than C3 photosynthesis?Journal of Experimental Botany 57, 303–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage RF, Pearcy RW. 2000. The physiological ecology of C4 photosynthesis. In: Leegood RC, Sharkey TD, Caemmerer SV, eds. Photosynthesis. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 497–532. [Google Scholar]

- Saintilan N, Rogers K. 2015. Woody plant encroachment of grasslands: a comparison of terrestrial and wetland settings. New Phytologist 205, 1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze ED, Ellis R, Schulze W, Trimborn P, Ziegler H. 1996. Diversity, metabolic types and δ13C carbon isotope ratios in the grass flora of Namibia in relation to growth form, precipitation and habitat conditions. Oecologia 106, 352–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharwood RE, Ghannoum O, Kapralov MV, Gunn LH, Whitney SM. 2016a Temperature responses of Rubisco from Paniceae grasses provide opportunities for improving C3 photosynthesis. Nature Plants 2, 16186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharwood RE, Sonawane BV, Ghannoum O. 2014. Photosynthetic flexibility in maize exposed to salinity and shade. Journal of Experimental Botany 65, 3715–3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharwood RE, Sonawane BV, Ghannoum O, Whitney SM. 2016b Improved analysis of C4 and C3 photosynthesis via refined in vitro assays of their carbon fixation biochemistry. Journal of Experimental Botany 67, 3137–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharwood RE, von Caemmerer S, Maliga P, Whitney SM. 2008. The catalytic properties of hybrid Rubisco comprising tobacco small and sunflower large subunits mirror the kinetically equivalent source Rubiscos and can support tobacco growth. Plant Physiology 146, 83–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutz SS, Edwards GE, Cousins AB. 2014. Single-cell C4 photosynthesis: efficiency and acclimation of Bienertia sinuspersici to growth under low light. New Phytologist 202, 220–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Mizuno M, Hayashi M. 1984. Partitioning of nitrogen among ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase, and pyruvate orthophosphate dikinase as related to biomass productivity in maize seedlings. Plant Physiology 75, 665–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Ubierna N, Ma JY, Cousins AB. 2012. The influence of light quality on C4 photosynthesis under steady-state conditions in Zea mays and Miscanthus×giganteus: changes in rates of photosynthesis but not the efficiency of the CO2 concentrating mechanism. Plant, Cell and Environment 35, 982–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]