Abstract

DNA repair is now understood to play a key role in a variety of disease states, most notably cancer. Tools for studying DNA have typically relied on traditional biochemical methods which are often laborious and indirect. Efforts to study the biology and therapeutic relevance of DNA repair pathways can be limited by such methods. Recently, specific fluorescent probes have been developed to aid in the study of DNA repair. Fluorescent probes offer the advantage of being able to directly assay for DNA repair activity in a simple, mix-and-measure format. This review will summarize the distinct classes of probe designs and their potential utility in varied research and preclinical settings.

Graphical abstract

The genetic information in the cell is constantly under threat of degradation by endogenous and exogenous elements. Each human cell experiences tens of thousands of endogenously generated lesions per day, and potentially many thousands more from sunlight alone.1 In response to this, an elaborate DNA repair network has evolved, comparable in complexity and scope to the cell's transcriptional machinery. In the late 1960s, Cleaver and Setlow independently published a pair of papers suggesting that DNA repair played an integral role in the prevention and development of cancer.2,3 Today, scientists appreciate the panoply of DNA repair pathways that exist in human cells and the ways in which these pathways can become compromised, giving rise to cancer. Associations between mutations in DNA repair genes and specific cancers are becoming increasingly common.4 While our understanding of DNA repair has grown greatly, many of the tools for studying DNA repair have lagged behind, creating a significant need for improved methods. In response to this need, over the past decade researchers have developed fluorescent probes of DNA repair as tools to advance the study of repair pathways. This article reviews and characterizes recent efforts made toward developing fluorescent probes of these crucial enzymes. The field was previously reviewed in 2013 by Leung and coworkers;5 however the large number of novel probes and probe designs reported in recent years necessitates a new evaluation of the field. Note that while the terms “sensor” and “probe” both appear in the literature for describing similar chemical approaches, the majority of publications have used the term “probe” (which we use here) to describe these tools.

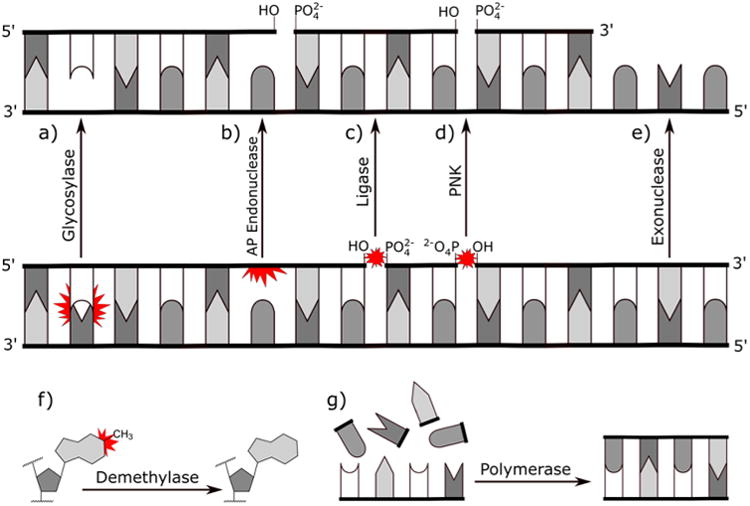

For the purposes of this review, it is useful to briefly highlight some of the major classes of enzymes involved in DNA repair. For the sake of brevity, this review will not cover the mechanistic details of DNA repair or its specific roles in cancer. Instead, we direct the reader to several recent reviews on these topics.4,6–9 The following is a short description of the catalytic function possessed by each class of enzyme that will be discussed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biochemical activities of key classes of repair enzymes. The lesions being recognized are marked by red stars.

Glycosylases (Figure 1a)

Glycosylases are enzymes that specifically recognize and excise damaged or mispaired bases by hydrolyzing the N-glycosidic bond between the heterocyclic base and the sugar ring, leaving behind an apurinic or apyrimidinic site (AP site). Some glycosylases, known as bifunctional glycosylases, possess an additional lyase functionality which allows them to nick the DNA backbone. Most glycosylases tightly bind promutagenic AP sites until displaced by an AP endonuclease. Glycosylases are essential in initiating base excision repair (BER) as well as epigenetic regulation of DNA.

AP Endonucleases (Figure 1b)

AP endonucleases are enzymes that recognize and cleave the DNA backbone either on the 3′ or 5′ side of an AP site, typically following glycosylase activity in BER or spontaneous depurination. Other classes of endonucleases participate in excision of damaged patches of DNA in BER and nucleotide excision repair (NER).

DNA Ligases (Figure 1c)

DNA ligases are enzymes that catalyze the formation of a phosphodiester bond between a 3′ hydroxyl and 5′ phosphate of DNA. Without ligase activity, promutagenic nicks would accumulate along the DNA backbone. Ligases participate in nearly all forms of DNA repair including BER, NER, mismatch repair (MMR), nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ), and homologous recombination (HR).

Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK; Figure 1d)

Polynucleotide kinase are enzymes that transfer the gamma phosphate from ATP to the hydroxyl group of a DNA or RNA terminus. Certain kinases, such as T4 polynucleotide kinase (T4 PNK), may have a phosphatase activity which allows them to hydrolyze phosphate groups as well. This allows T4 PNK to dephosphorylate 3′ phosphates and phosphorylate 5′ hydroxyl groups, allowing polymerases and ligases to complete the DNA repair cycle. These kinases participate in the same pathways as DNA ligases.

Exonucleases (Figure 1e)

Exonucleases are enzymes that digest nucleic acids by cleaving nucleotides from the end of a DNA or RNA chain. Exonucleases are essential for digesting damaged DNA strands in MMR and HR.

Polymerases (Figure 1g)

Polymerases are enzymes that catalyze the formation of polynucleotide chains using nucleotide triphosphates. Polymerases are responsible for replacing excised nucleotides in BER, NER, MMR, and HR.

Demethylases (Figure 1f)

Demethylases are enzymes that remove alkyl groups, typically methyl groups, from the reactive nitrogen and oxygen atoms in DNA bases. Demethylases directly reverse DNA damage without the need to delete and rewrite genetic information. Such repair is referred to as direct reversal (DR).

Traditionally, as with most nucleic acid modifying enzymes, the predominant method for studying DNA repair has been gel electrophoresis or radiation release assay.10,11 Gel electrophoresis allows a scientist to study enzymes that change the mobility of DNA through a gel. This method works well for studying enzymes such as bifunctional glycosylases, nucleases, or ligases as these enzymes cause significant gel shifts to their substrates. Radiation release assays use radiolabeled DNA and measure the release of repair products into the supernatant. This technique works well for monofunctional glycosylases, phosphatases, and demethylases. However, both methods are time intensive and discontinuous techniques, making the measurement of quantitative and time-dependent values such as KM and kcat laborious. Additionally, radiation release assays require the handling and use of expensive radioactive materials such as tritium. More recently, LCMS,12 Capillary Electrophoresis,13 and qPCR14 have been used; however these methods still suffer from discontinuity, low-throughput, and relatively high cost per sample, limiting their utility for high throughput analysis. While the COMET assay is well-known for determining global DNA damage and repair activity in cells,15 very few methods exist for studying the repair activity of individual enzymes in living cells or whole cell lysates. Immunohistochemistry such as Western blotting and immunostaining, may be used to quantify protein amounts, but not their activity.

In the past few years, there has been a significant effort in many laboratories to develop fluorescent probes of DNA repair, spurred by not only the increasing connections to cancer biology but also by the growing realization that some of them are promising therapeutic targets.16 The use of fluorescent probes offers many advantages over the above traditional methods. The most significant advantages are the simplicity of instrumentation and implementation, the ability to monitor repair in real-time, and the possibility of imaging DNA repair in cells and tissues. Since fluorescence is a continuous method, a single reaction under given conditions is needed to calculate an initial rate, whereas discontinuous methods such as polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) require many individual reactions to be run, then stopped and stored for future quantitation. For this reason, fluorescent probes of DNA repair can be more readily adapted for high-throughput assays of DNA repair activity. Furthermore, cell-permeable fluorescent probes can be used to directly observe DNA repair activity of specific enzymes in tissue culture. A robust and well-designed fluorescent probe can be used to quantify enzyme activity levels in different cell lines and tissues using spectrometers, fluorescence microscopy, or flow cytometry. The ubiquity of such fluorescence instrumentation makes these methods readily available to most researchers.

Introduction to Probe Design

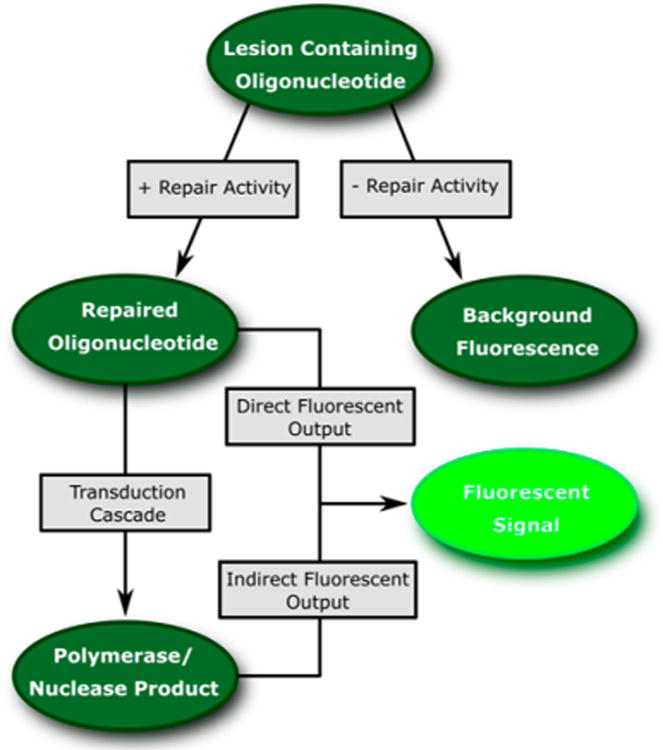

On its most fundamental level, a biological probe may be thought of as a logic gate in which some input is converted into an output. In the case of fluorescent probes of DNA repair, the input is a lesion containing oligonucleotide, and the output is a change in the intensity of a fluorescence signal which correlates to the activity of a specific DNA repair enzyme. The most useful fluorescent probes should be able to respond dynamically to DNA repair activity. The dynamic response allows for quantification of repair activity to determine parameters such as kinetic constants, potency of inhibitors, and activity levels in cells.

The design of a probe can be generically modeled as in Figure 2. The first step in any DNA repair probe is the conversion of a lesion-containing substrate into a repaired product. Since DNA is the natural substrate of most repair enzymes, the lesion containing substrate typically manifests as a short oligonucleotide that has site-selectively incorporated a DNA lesion that the enzyme of interest will recognize and repair. To prevent high background, the lesion must in some way inhibit the fluorescence output and be specifically repaired by the enzyme. The repaired oligonucleotide may either generate a direct fluorescence output or may serve as a new substrate for further downstream processing that will ultimately result in a fluorescence signal. Probes that require further downstream processing by other enzymes and oligonucleotides generate an indirect signal. Indirect output probes typically cannot be used in cells and are often discontinuous owing to the need for multiple steps during signal generation. While the term “probe” suggests a single small molecule or oligonucleotide reporter, many of the published fluorescent DNA repair probes require complex systems of oligonucleotides and polymerases/nucleases to transduce the signal.

Figure 2.

Transduction of repair activity into a fluorescence signal. The lesion containing oligonucleotide is designed such that the lesion inhibits signal generation. Repair of the lesion is the initiating step in a transduction cascade that generates a fluorescent output. In certain probe designs, lesion repair alone generates a direct fluorescent output. In most cases, however, after the lesion is repaired there are several additional steps required to transduce the repaired oligonucleotide into a fluorescent signal.

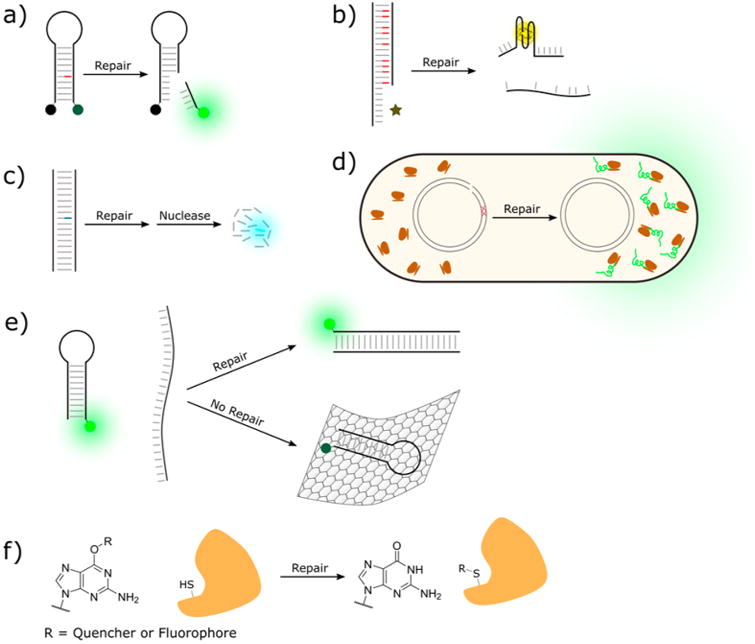

While hundreds of different probes have been reported to date, there are several major design motifs under which most reported probes can be categorized (Figure 3):

Molecular beacon probes (Figure 3a): Synthetic quenchers and fluorophores are placed on a DNA scaffold. DNA repair initiates a signal transduction cascade that results in separation of the fluorophore/quencher pair.

DNA-binding stimulated fluorescence probes (Figure 3b): The repaired oligonucleotide initiates formation of a secondary structure which is subsequently bound by an environmentally sensitive fluorophore or metal ion.

Naturally quenched probes (Figure 3c): DNA itself directly quenches a carefully chosen fluorophore. Upon repair of the lesion, structural or electronic changes diminish this quenching effect and fluorescence is restored.

Host cell reactivation probes (Figure 3d): A plasmid coding for a fluorescent protein is damaged to prevent proper expression of the fluorescent protein. Upon repair of the plasmid by cellular machinery, the fluorescent protein is expressed.

Graphene oxide probes (Figure 3e): Repairedoligonucleotides are liberated from a fluorophore-quenchinggraphene oxide surface by formation of fully duplexed DNA.

O6-guanine labeled probes (Figure 3f): Alkyl labels areappended to guanosine and are removed by alkyl transferases togenerate a fluorescent signal.

Figure 3.

Examples of major types of DNA repair probe designs. (a) Simple molecular beacon probe. (b) DNA binding-stimulated fluorescence probe. (c) Naturally quenched probe. (d) Host cell reactivation probe. (e) O6-guanine labeled probe. (f) Graphene oxide based probe.

Molecular Beacon Probes

The concept of the molecular beacon hybridization probe was first reported in 1996 by Tyagi and Kramer.17 Four years later, Biggins et al. designed a molecular beacon probe for the restriction endonuclease BamHI by incorporating its recognition sequence into the stem.18 Upon cleavage of the probe stem by BamHI, the fluorophore and quencher fragments dissociate, resulting in a fluorescence light-up. The authors suggested that such a probe design could be used to develop continuous assays for various enzymatic DNA strand cleaving agents. Since the inception of the molecular beacon, many probes have been developed based on the concept of using DNA as a scaffold to place synthetic quenchers and fluorophores in proximity (see below). Through cleavage, digestion, or changes in secondary structure, the quencher and fluorophore are separated in space and the quenching effected is diminished. This represents the largest category of fluorescent probes of DNA repair. We have divided molecular beacon repair probes into two subcategories, simple molecular beacons (Figure 3a) and signal amplification molecular beacons (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Signal amplification cycle of a nuclease or DNAzyme dependent signal amplification probe. The template strand is generated as a product of DNA repair.

Simple Molecular Beacons

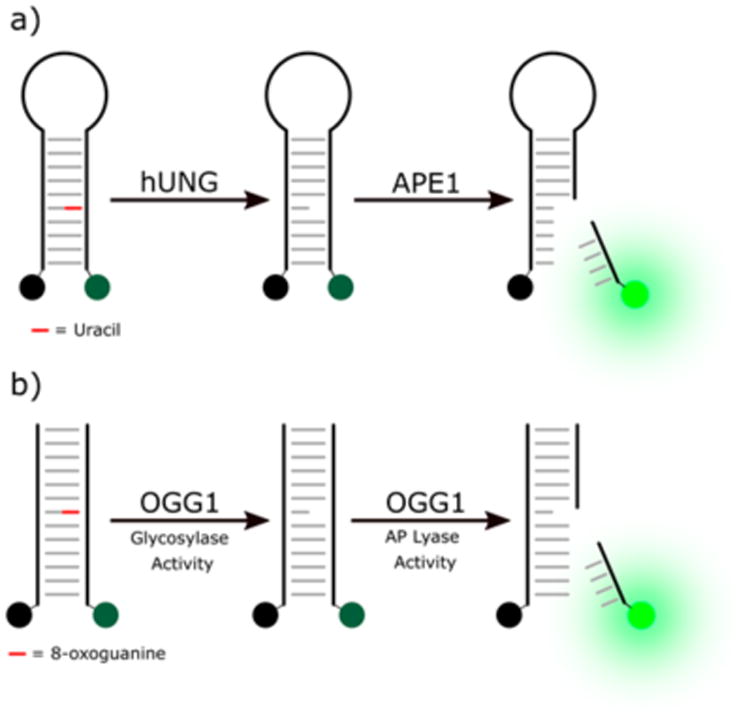

An early example of a molecular beacon repair probe was reported by the group of Saparbaev in 2004.19 Using molecular beacon probes labeled with 5′-fluorescein and 3′-dabcyl, researchers incorporated either a series of deoxyuridine lesions or a single AP site into the 13-bp stem of the beacon to assay either human uracil DNA glycosylase (hUNG) or human AP endonuclease 1 (APE1). The APE1 probe contains a single uracil and is first pretreated with hUNG to generate an AP site. The probe can then be used to assay APE1, which performs strand scission resulting in the dissociation of the fluorescein containing fragment (Figure 4a). In the case of the hUNG probe, the hairpin incorporates multiple uracil residues into the stem, becoming destabilized and dissociating after base excision takes place. These probes were used to monitor repair activity of purified enzyme and cell free extracts as well as transfected into cells. In the extracts and cells, repair deficient cell lines showed diminished repair activity. Additionally, the probes could be used to measure enzyme inhibition. Following the work of Saparbaev, others have reported similar hUNG and APE1 probes that provide some improvements to the original probe design such as eliminating the need for multiple uracil residues.20–24 A similar probe of endonuclease III-like protein 1 (NTH1) was reported, which replaces uracil with damaged thymine bases,25 and a molecular beacon based probe of phosphodiesterase 1 has also been reported.26 A strand displacement assay of DNA polymerases reported by the group of Simeonov27 was later used by Coggins and co-workers to screen small molecule inhibitors and perform a SAR study on several hits.28 A polymerase-dependent, strand displacement probe was previously reported by Ma and co-workers to assay the dephosphorylating activity of T4 PNK.29

Figure 4.

(a) The molecular beacon based probe reported by Saparbaev, which uses APE1 to generate a signal following the repair activity of hUNG. (b) The molecular beacon based probe reported by Lloyd uses a simple duplex and requires the AP lyase activity of OGG1 to generate a signal.

In a similar vein, a series of molecular beacon probes of the bifunctional glycosylase 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) have also been reported. By placing 8-oxoguanine in the stem of a molecular beacon, Mirbahai et al. created a scission dependent probe of OGG1.30 It should be noted that the cellular relevance of OGG1's lyase activity is under question.31 This molecular beacon probe was used to study OGG1 expression levels in response to oxidative stress. A slightly different probe consisting of a short DNA duplex bearing a rhodamine fluorophore and Black Hole Quencher (BHQ) was reported by Lloyd and co-workers (Figure 4b).32,33 This probe also relies on the lyase activity of OGG1 to stimulate strand dissociation and was used to assay a small library of inhibitors. Since the probe measures strand scission rather than base excision, inhibitors discovered via such assays may inhibit any one of these steps rather than base excision alone.

To simplify workflow and allow for rapid separation of the probe from complex matrices, several groups have reported on-bead versions of molecular beacon repair probes.34–40 Such probes operate either by generating a fluorescent on-bead light up or by releasing a fluorophore from the bead surface into solution. In one recent example, an on-bead probe of APE 1 was used in cells to explore APE 1 repair activity in tumors.41

Signal Amplification Probes

In a simple molecular beacon probe, one turnover of an enzyme generates a single unquenched fluorophore.18 As a result, the signal strength correlates linearly to the amount of enzyme present, making detection of small amounts of enzyme a challenge. In an effort to lower detection limits, several signal amplification methods have been developed. While these signal amplification probes do not typically use molecular beacons, we have chosen to classify them under the molecular beacon category because they still rely on the quenching of a fluorophore using a synthetic quencher.

The signal amplification step is generically represented in Figure 5. First, a template strand is generated as a product of DNA repair. The template strand then duplexes with a quencher/fluorophore labeled reporter oligonucleotide. Upon duplexing of the template and reporter oligonucleotide, either a nuclease or DNAzyme cleaves the reporter oligonucleotide, causing the fluorophore to become unquenched. The amplification cycle may turn over multiple times from a single template strand allowing for an accumulation of signal. These probes are classified here as either nuclease dependent or DNAzyme dependent.

Nuclease Dependent Signal Amplification Probes

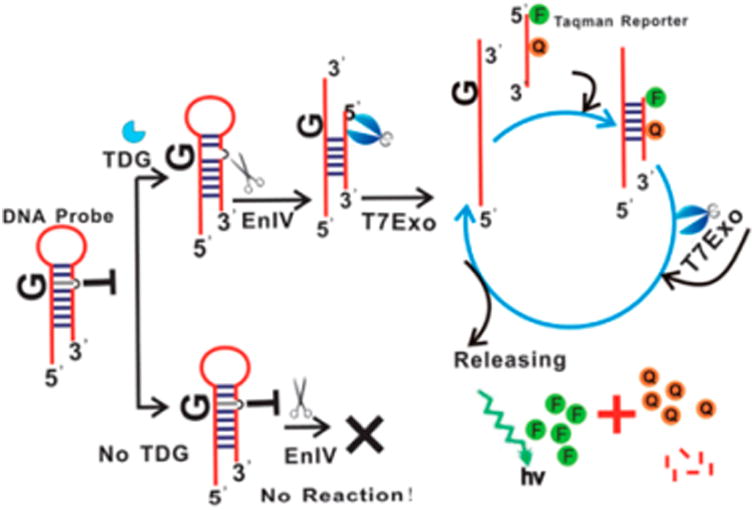

Nuclease dependent signal amplification probes operate by digesting the reporter oligonucleotide through either exonuclease digestion or endonuclease cleavage. The probes in this category typically require one nuclease and sometimes a polymerase to generate the template strand. This means that signal amplification probes are typically discontinuous. In the past 5 years, many nuclease dependent probes of various glycosylases and kinases have been reported. Probes of thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG),42 Endo IV,43 T4 PNK,44 and OGG145 have been developed which use a TaqMan reporter (Figure 6). A slightly modified design that uses a specific endonuclease restriction site has also been reported for probes of TDG,46 bacterial uracil glycosylase (UDG),47 and T4 PNK.48 Probes that use a cyclic signal amplification step have reported detection limits between 0.01 and 0.001 U/mL; however the need for many components limits their use in high throughput or cellular contexts.

Figure 6.

Example of a signal amplification probe of TDG reported by Chen et al.42 Upon repair of the G:T mismatch by TDG, the AP endonuclease EnIV cuts the DNA. The resulting 5′ terminal is digested by T7Exo. The G-containing template strand duplexes with the reporter oligonucleotide that is digested by T7 Exo to generate a fluorescent signal. Because the template strand is recycled, the signal of a single enzyme turnover is amplified. Reproduced from ref 42 with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry, copyright 2013.

DNAzyme Dependent Amplification Probes

To eliminate the need for an exogenous nuclease, several groups have used DNA repair to stimulate in situ formation of a DNAzyme that catalyzes cleavage of a reporter oligonucleotide. Similar to the endonuclease dependent probes, DNAzymes may turn over multiple times allowing for signal accumulation from a small number of turnovers. The first example came from Zhang et al., who use a partially duplexed circular DNA containing a U:A mispair to generate a primer for rolling circle amplification (RCA), which is revealed after uracil excision by UDG and cleavage by endonuclease IV.49 The product of RCA is an autocatalytic DNAzyme which cleaves a reporter oligonucleotide. A similar strategy was later employed by Kong et al. in their probe of OGG1.50 Xiang and Lu developed a DNAzyme that is inactivated by replacing an essential thymidine with uridine. Upon excision of the uridine by UDG, DNAzyme activity is restored, allowing it to cleave a reporter oligonucleotide.51 The detection limits reported by the DNAzyme based probes are comparable to the nuclease dependent signal amplification probes.

DNA Binding Stimulated Fluorescence Probes

DNA binding stimulated fluorescence probes are oligonucleotides that form secondary structures once they are repaired. The secondary structure then binds an environmentally sensitive fluorophore or metal ion. The most common secondary structure formed is the G-quadruplex; however, probes have also been designed to template fluorescent nanoparticles or bind intercalating dyes. In any DNA binding stimulated fluorescence probe, the DNA lesion prevents formation of the required secondary structure.

G-Quadruplex Based Probes

In G-quadruplex based probes, the repair of a lesion causes the release or synthesis of a G-quadruplex forming strand which then binds a chromophore or metal ion to generate fluorescence. Early G-quadruplex based probes were reported by the groups of Leung and Ma as well as the group of Ren. In 2011, Leung and Ma reported a probe of exonuclease III (ExoIII) in which a guanosine rich hairpin is partially digested by ExoIII to release a G-quadruplex forming strand.52 The resulting G-quadruplex binds Crystal Violet dye to generate a ∼3 fold change in fluorescence. Concurrently, Ren also reported a G-quadruplex based probe of UDG consisting of a G-quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide annealed to a 16-base “blocking” oligonucleotide which contains several uracil residues (Figure 3b). The blocking oligonucleotide prevents the G-quadruplex loop from forming; however upon excision of the uracil residues by UDG, the blocking strand dissociates from the G-quadruplex forming oligonucleotide allowing it to fold. The fluorophore N-methyl mesoporphyrin IX (NMM) then binds the G-quadruplex generating a ∼14-fold enhancement in fluorescence. The blocking strand design has been used in several subsequent UDG probes54,55 and a T4 PNK probe.56 Other G-quadruplex forming probe designs include primer extension based probes of T4 PNK,57,58 a split G-quadruplex probe of DNA ligase,59 and a toehold mediated strand displacement probe of UDG.60 Leung and co-workers have continued their work in this field with recently reported probes of TDG61 and of several nucleases.62,63 As with molecular beacon based probes, several signal amplification probes have also been reported based on G-quadruplex formation. Such signal amplification probes have been made for the detection of UDG,64 APE1,65 and T4 PNK,66 which claim detection limits between 10–3 and 10–4 U/mL.

Fluorescent Nanoparticle Forming Probes

Recently, researchers have begun exploring DNA-templated fluorescent nanoparticles as alternatives to organic dyes. In the presence of a reducing agent, such as ascorbate, DNA may template the formation of strongly fluorescent metal nanoparticles. The most widely explored example of this is the formation of DNA-templated copper nanoparticles (CuNPs), which have a strong absorption band around 340 nm and emit at 600 nm, giving them a very large Stokes shift. Copper nanoparticles can be templated by duplex DNA or single stranded DNA containing regions of polyT.67

Recently, Qing et al. reported a probe of T4 PNK that consists of a nicked dumbbell68 (Figure 7). In the presence of T4 PNK, the nick is repaired through a kinase dependent pathway, resulting in fully circularized DNA. Once circularized, the dumbbell is resistant to exonuclease digestion and fluorescent CuNPs form. In the absence of T4 PNK, the DNA is degraded by an exonuclease and cannot template CuNPs. A similar “turn-off” version of this probe was previously reported which uses kinase-dependent exonuclease digestion to darken the probe in the presence of T4 PNK and λ exonuclease.69 Several other CuNP based probes have been reported for T4 PNK70,71 and UDG72 that are very similar in design and performance. Probes of T4 PNK,73,74 poly-merases,75,76 and UDG77 have also been reported that use the DNA intercalating dye SYBR Green instead of copper nanoparticles but function on the same principle.

Figure 7.

T4 PNK copper nanoparticle dumbbell probe designed by Qing et al.68 In order to assay for the presence of T4 PNK, T4 DNA ligase and an exonuclease are added to the mixture followed by the nicked dumbbell. Only in the presence of T4 PNK will the 5′ OH be phosphorylated, allowing for ligation of the nick which protects the structure from digestion. Ascorbate and Cu2+ are then added, which template fluorescent copper nanoparticles in the presence of duplexed DNA.

Naturally Quenched Probes

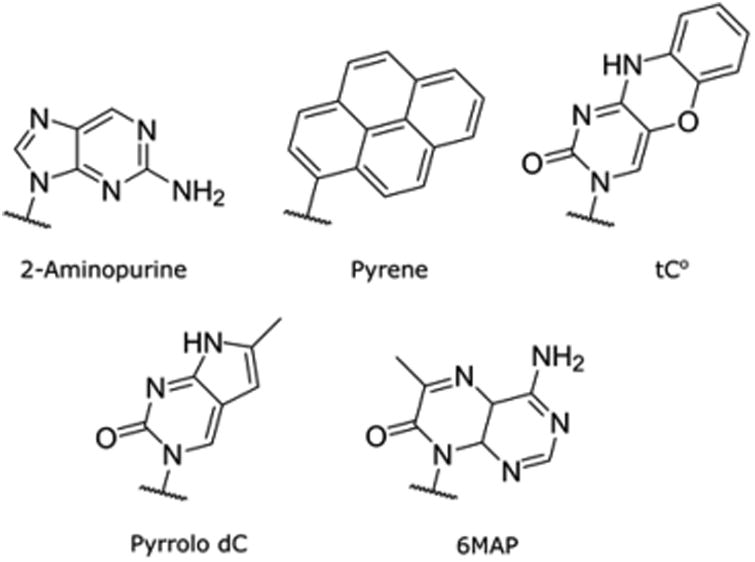

While molecular beacon based probes rely on synthetic quenchers such as dabcyl or BHQ, naturally quenched probes use the intrinsic quenching properties of canonical DNA bases to report on changes in DNA structure. In most cases, naturally quenched probes contain a fluorescent nucleoside analogue that is strongly quenched in duplex DNA but becomes emissive when liberated from the DNA duplex. The most well-studied fluorescent nucleoside analogue is 2-aminopurine (2AP), which has proven useful as a research tool because of its fluorescence properties as well as its ability to act as a wobble base pair.78 In DNA, 2-AP can base pair with either cytosine or thymine, and its fluorescence is strongly quenched in duplex DNA. Over the past several decades, a host of new fluorescent nucleoside analogues has been reported (Figure 8), some of them enabling the design of naturally quenched probes of DNA drepair. For more information on fluorescent nucleoside analogues, we direct the reader to a recent review on the topic.79 We group these probes into three categories: base flipping probes, fluorophore liberation probes, and natural base quenching probes.

Figure 8.

Several examples of fluorescent nucleoside analogue bases. Each base is attached to deoxyribose.

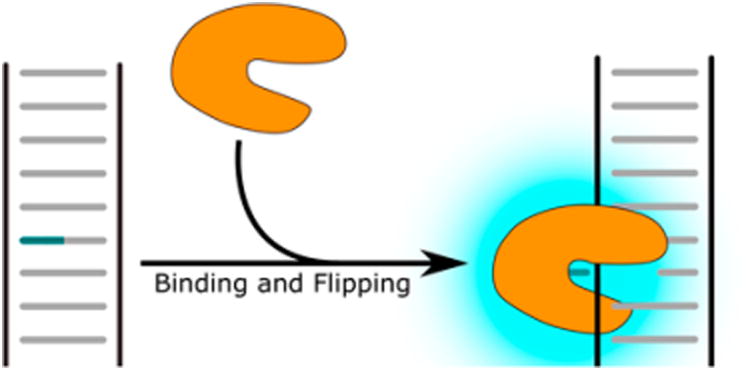

Base-Flipping Probes

Base-flipping probes typically use ultrafast time-resolved fluorescence to study the dynamics of enzymes that shift (“flip”) a base to be repaired out of the helix and into an enzyme pocket. Rather than measuring the complete DNA repair reaction (i.e., base excision), these probes are useful for determining the kinetic and mechanistic details of the early base flipping step that certain repair enzymes, such as glycosylases, perform as part of their catalytic cycle.80 Typically, these probes function by placing a fluorescent nucleoside analogue that is quenched by duplexed DNA adjacent to or opposite a DNA lesion. When either the lesion or the nucleoside analogue is flipped into the extrahelical position, a rapid change in fluorescence is observed (Figure 9), on a time scale of milliseconds to nanoseconds. Fast time-resolved fluorescence base-flipping studies have focused on repair enzymes such as UDG,81,82 T4 pyrimidine dimer glycosylase,83 DNA photolyase,84,85 and O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase (AGT).86 The use of such probes, in conjunction with mutation studies, has revealed important details about the mechanisms of base flipping enzymes involved in DNA repair.

Figure 9.

Base flipping probes measure the dynamics of base flipping enzymes using environmentally sensitive fluorescent nucleoside analogues.

Fluorophore Liberation Probes

In fluorophore liberation probes, the DNA duplex is either destabilized or entirely digested through a pathway initiated by the activity of a DNA repair enzyme. The liberation of the fluorophore from the duplex DNA creates a fluorescent signal (Figure 3c). Several fluorophore liberation probes of T4 PNK have been reported, all of which function on the basis of 5′ phosphorylation-dependent exonuclease digestion.87–89 Similar to molecular beacon probes, several probes have been developed which rely on strand scission to destabilize a duplex. For example, a probe of AGT has been reported which possesses a methylated restriction site. Upon demethylation, the restriction site is recognized and digested by exonucleases resulting in strand dissociation. One of the released strands contains a duplex-quenched nucleoside analogue.90 Similarly, an OGG1 probe has been reported in which OGG1 catalyzed strand scission causes dissociation of a nucleoside analogue containing strand.91 A clever probe of UDG has been designed which uses G-quadruplex formation to place 2-aminopurine extrahelical to the duplex.92 One example of a signal amplification fluorophore liberation probe has been reported, which uses a bifunctional probe to detect both OGG1 and UDG through exonuclease degradation of a 2-AP or pyrrolo deoxycytidine (PdC) containing hairpin. This yielded a reported detection limit of ∼0.004 U/mL.93

Natural Base Quenching Probes

Recently, our lab began developing probes which are designed around the native fluorescence quenching ability of DNA lesions.94–98 Similar to the above probes, these natural base quenching probes rely on the quenching of a fluorescent nucleoside analogue by natural DNA. However, in natural base quenching probes the quencher is the DNA lesion itself rather than the entire DNA duplex (Figure 10). For a natural base quenching probe to function, the DNA lesion itself must be an effective quencher while the repaired product must provide little quenching. The fundamental design challenge of such a probe is to identify a fluorescent nucleoside analogue which is strongly quenched by the DNA lesion and poorly quenched by the remaining bases in the repaired product.

Figure 10.

A damaged base quenching probe of the demethylase ABH3, which relies on the ability of 1-methyladenine (m1A) to quench the fluorescence of a neighboring pyrene nucleoside analogue. Upon demethylation by ABH3, the quenching interaction is diminished owing to the loss of a formal positive charge on the damaged base.

The first such probe targeted UDG.94 Previously, it had been shown that pyrimidine bases were effective quenchers of a pyrene fluorescent nucleoside analogue while adenine was not.99 On the basis of this observation, a UDG probe was designed which sandwiches a pyrene nucleoside analogue between two uracil residues in the middle of a short poly(dA) oligonucleotide. Upon excision of the uracil residues, the pyrimidine quenching effect is lost, and the fluorescence of the pyrene nucleoside is restored. This results in a 90-fold increase in fluorescence. This probe design was further modified with the use of pyrene excimers to redshift the emission for use in live cells.96

We next developed a probe of the enzyme OGG1 by exploiting the fluorescence quenching properties of the 8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) lesion.100 Since little was known about 8-oxoG's ability to quench fluorescent nucleoside analogues, a screen was performed to identify an analogue which was strongly quenched by a neighboring 8-oxoG. The screen identified the nucleoside analogue tC°, which was then placed adjacent to 8-oxoG in a DNA hairpin. The resulting probe generates a 40-fold light up response to OGG1 base excision. Importantly, because the signal is generated immediately following base excision, this probe does not rely on the AP lyase activity of OGG1 for signal generation and instead reports directly on glycosylase activity. Such details can be important. For example, the base excision activity (and not DNA lysase activity) of OGG1 is implicated in mammalian inflammation pathways;101 a probe that requires the latter for signaling may report on molecular activities that are not relevant to the biology under study.

A more recent natural base quenching probe was reported for the demethylase ABH3 (Figure 10), which repairs the positively charged lesions 1-methyladenine (m1A) and 3-methylcytosine.102 Due to the small structural change created by demethylation, designing probes of demethylases is quite challenging. We hypothesized that because m1A is positively charged and electron deficient, it might quench electron rich fluorophores (with high LUMO energy levels) while the natural adenosine base would not. After screening several fluorophore candidates, it was found that pyrene was strongly quenched by a neighboring m1A residue but not by a neighboring adenosine. By placing a pyrene nucleoside next to the m1A lesion, the probe could report directly on the demethylase activity of ABH3. The resulting probe was able to measure ABH3 activity in vitro, in lysates and in live cells. Demethylation represents a relatively small structural perturbation in DNA, making signal transduction relatively challenging.

Previous demethylase probes have relied on endonuclease scission of methylated restriction sites, generating an indirect signal of DNA repair.90 The methyl-adenosine quenched probe's ability to directly report on a small structural change without the need for other enzymes demonstrates the advantage of natural base quenching probes.

Host Cell Reactivation Probes

Host cell reactivation probes are distinct from the above probes because they are used to assay the activity of an entire repair pathway in a living cell rather than a single enzyme. As the name suggests, these probes function by measuring the ability of a cell to repair, or reactivate, a damaged plasmid which expresses a fluorescent protein. Only upon repair of the damage will the fluorescent protein be properly expressed (Figure 3d). Cells that are mutated or lack the proper repair pathways will not fluoresce.

The idea of using host cell reactivation to couple DNA repair to expression of a fluorescent protein was first put forward by Roguev and Russev in 2000.103 To assess the overall repair capacity of a cell, the authors took enhanced GFP constructs and irradiated them with UV light, causing photodamage of the plasmid DNA. Following transfection of the damaged plasmid, they were able to monitor the rate at which fluorescence was restored relative to the unirradiated construct. This was a broad probe of DNA photodamage repair since the damage was not site specific or homogeneous. The probe was used to identify repair deficient cell lines. The concept was taken further by the groups of Sun and Dong through the introduction of specific mismatches into the GFP construct to measure mismatch repair activity in different cell lines.104–106 In 2014, the group of Samson developed a flow-cytometric host cell reactivation assay to measure multiple DNA repair pathways at once.107 They have since used this assay to measure several different repair deficiencies in a wide array of cell types.108,109 Host cell reactivation probes have been used to study outcomes in double strand breaks well.110,111 These probes are biochemically complex, and interpreting a negative result (no expression) can be a challenge.

Graphene Oxide DNA Adsorption Systems

In 2009, Lu et al. demonstrated that in addition to acting as a fluorophore quencher, graphene oxide (GO) could selectively bind ssDNA over dsDNA.112 It was proposed that in the absence of a complementary strand, DNA nucleobases would stack with the hydrophobic GO surface. Owing to GO's ability to quench fluorophores as well as discriminate between ssDNA and dsDNA, GO has lent itself well to DNA repair probes. In these probes, the signal transduction cascade creates or destroys ssDNA, resulting in adsorption or release of a fluorophorecontaining oligonucleotide (Figure 3e).

In 2011, Wu et al. reported the first graphene-oxide based system for the detection of T4 PNK.113 In their system, a nick is introduced into a DNA duplex. When T4 PNK is present, the nick is repaired by a kinase dependent pathway, and a stable duplex is formed with a Tm of >50 °C. In the absence of T4 PNK, the nick cannot be repaired, causing the duplex to melt upon heating to 50 °C. Once melted, a semistable hairpin forms which adsorbs to the GO surface through the single-stranded loop region, quenching the attached fluorophore label. Other hairpin-based methods have been developed for the detection of DNA phosphatases114 and UDG.115,116 An alternative system for T4 PNK detection based on hairpin loop elongation has also been developed.117 In addition to hairpin based probes, a probe for UDG detection has been developed using supercharged GFP and GO by Wang and co-workers.118

GO based biosensing systems continue to gain prominence; however their utility in high throughput screens may be limited due to GO's hydrophobic surface, which is known to adsorb drug-like molecules.119 In spite of this, a screen of helicase inhibitors has been reported using an oligonucleotide/GO based assay.120 While GO nanosheets have been used for cellular DNA aptamer delivery,121 none of the reported GO based DNA repair probes have been used in live cells.

O6-Alkylguanine Probes

Probes of the suicide repair enzyme O6-alkylguanine DNA transferase, also known as MGMT or AGT, represent a highly specialized class of probes. MGMT is a suicide enzyme which transfers alkyl adducts from guanine O-6 onto an active site cysteine (Figure 3f).122 The lab of Johnsson first showed in 2001 that an O6-biotin-labeled guanine could serve as a substrate for AGT to perform a streptavidin pulldown assay of AGT.123 This concept was later developed into the SNAP-Tag technology in which AGT fusion proteins can be labeled with fluorescently labeled O6-benzylguanine derivatives.124

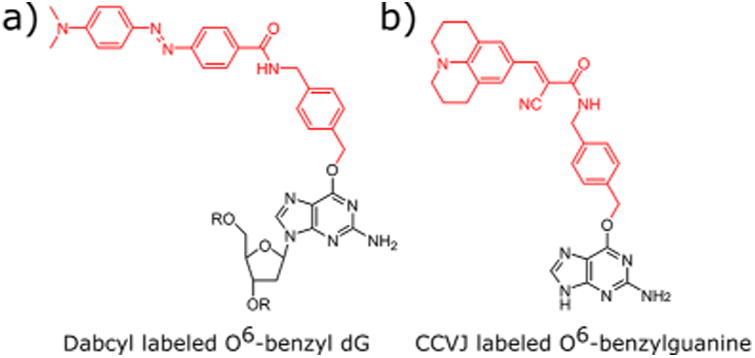

While the probes developed in the Johnsson lab can directly label AGT/MGMT in cells, they can have limits as quantitative probes of enzyme activity since the catalyzed reaction often generates no change in fluorescence. In 2015, Tintore et al. reported a probe of AGT activity by incorporating fluoresceinlabeled O6-benzylguanine into an oligonucleotide and base pairing it opposite a dabcyl labeled cytosine.125 A fluorescence signal is generated by removal of the fluorescein adduct from the dabcyl-containing duplex. Concurrently, our lab reported a series of probes in which a dabcyl labeled O6-benzyl deoxyguanosine (Figure 11a) is incorporated into a fluorophore labeled oligonucleotide.126 In our probe design, MGMT removes the quencher from the probe rather than the fluorophore, yielding a ∼40-fold light-up signal. This probe has the advantage of being relatively small, single-stranded, and nuclease resistant and was shown to function in mammalian cell lysates. A more recently reported MGMT probe uses the fluorescent molecular rotor CCVJ, which becomes highly emissive when conformationally locked.127 The motor rotates freely when appended to O6-benzylguanine (Figure 11b); however, upon transfer to MGMT it becomes rotationally locked in the enzyme binding pocket, resulting in increased fluorescence. The fluorescence intensity diminishes upon enzyme degradation because the CCVJ fluorophore is no longer conformationally locked.

Figure 11.

O6-Benzylguanine labeled probes. The red portion of each molecule is transferred to a reactive cysteine residue in the active site of MGMT. (a) The dabcyl labeled O6-benzyl deoxyguanosine reported by Beharry and co-workers.126 The modified nucleoside is incorporated into fluorescently labeled oligonucleotides. MGMT activity removes the quenching dabcyl moiety. (b) The rotor based probe reported by Yu and co-workers.127 Upon transfer of the CCVJ moiety to MGMT, intramolecular bond rotation about the trisubstituted olefin is hindered causing CCVJ to become emissive.

Future Directions

While the number of probes reported in the literature continues to increase, the number of probes that have found traction in clinical applications remains small. Countless probes have been reported in the hopes of screening potential drugs or providing clinical diagnostic tools; however such applications are often blocked by limitations in design and performance. Indeed, while several probes have been used to confirm previously reported inhibitors, there have only been a handful of high-throughput screens performed using such probes. For many probes, practical considerations concerning the feasibility of high-throughput screening remain to be addressed.

Two major problems most existing DNA repair probes suffer from are complexity of design and limited target choice. Some classes of probes—for example, molecular beacon based signal amplification probes—require complex signal generating pathways involving multiple oligonucleotides, nucleases, and polymerases to transduce the action of a DNA repair enzyme into a fluorescent signal. Indeed, some probe designs require upward of eight individual steps to produce a fluorescent signal. The added requirement of components such as restriction endonucleases makes such probes difficult or impossible to use in cells and cumbersome to use in lysates and offers multiple paths to false positive signals. Furthermore, a high throughput assay requiring additional proteins and oligonucleotides may be difficult to optimize by introducing many alternative and undesired targets for small molecules to bind. While many efforts have been made to lower probe detection limits, much less progress has been made toward simplifying probe designs.

Some recent probe designs have attempted to address the issue of complexity in design. Minimizing probe size and keeping the design simple (such as natural base quenching probes) minimizes false positives and improves cell permeability and activity. In one recent example, a probe of OGG1 was used in a high throughput screen to identify OGG1 inhibitors. A subsequent SAR study of the screen hits resulted in novel, potent inhibitors of OGG1128. Several other instances of enzyme inhibitors being identified using a fluorescent probe of DNA repair have been reported,28,32,33,129 but many repair enzymes remain inaccessible to HTS.

In addition to HTS, another promising application of fluorescent DNA repair probes is assaying repair activity directly in biological media, including lysates and intact cells. Cell permeable probes of DNA repair can identify repair deficient or overexpressing cell populations without the need for expensive and time-consuming PCR or immunohistochemistry. Importantly, enzyme-targeting probes can directly measure activity, while measurements of RNA expression or protein quantity are indirect and are likely to be less directly relevant to the biology of the pathway. Future therapies aimed at DNA repair pathways will no doubt benefit from quantitative measures of their activities in patient samples. Direct fluorogenic probes can address these issues; for example, recent probes of ALKBH3, MGMT, and APE1 have been used to quantify expression levels of repair enzymes in different human cell lines.41,102,127 In addition to HTS and clinical applications, simple, cell-permeable probes of DNA repair could be used in super-resolution microscopy for the study of localized DNA repair dynamics in live cells. Going forward, simplifying probe design and paying attention to issues of stability and background signals will be essential for the development of useful DNA repair probes for studying cancer biology.

Another issue for many reported probes is the lack of diversity when it comes to selecting enzyme targets. For example, for the enzymes UDG and T4 PNK alone there are over 35 reported probe designs. While these enzymes have the attractive properties of being relatively robust and cheaply available, they only represent a small fraction of the therapeutically implicated repair enzymes that are known. For the field to progress, probes must be developed that assay new, diverse repair enzymes beyond these well-studied examples. Given the many advantages of fluorescence methods and creative diversity of probe designs, there is a great deal of potential for the field to expand, providing much needed tools for studying DNA repair.

Acknowledgments

We thank the U.S. National Institutes of Health (GM110050, GM106067, CA217809) for support.

Keywords

- Fluorescence

the process by which light of a specific wavelength is absorbed by a molecule and then emitted at a longer wavelength through a special relaxation pathway

- DNA repair

the cellular process by which DNA is maintained; compromised DNA repair pathways can give rise to cancer or other disease states because of its role in gene regulation

- Oligonucleotide probe

a small polynucleotide chain which is designed to interrogate some property of a system such as presence or activity of a specific enzyme; oligonucleotide probes must produce an output such as fluorescence, luminescence, or an electrochemical signal

- Fluorescent nucleoside analogue

a non-natural nucleobase which possess fluorescence properties; when incorporated into an oligonucleotide, the base participates in stacking or hydrogen bonding in a manner analogues to a natural base

- Molecular beacon

a specific type of molecular probe which is based on a DNA hairpin structure that is labeled with a quencher on one end and a fluorophore on the other; any event which causes destruction of the hairpin structure (i.e., hybridization) causes the quencher to become unquenched

- High throughput screening:

the process of testing large libraries of drug-like molecules as inhibitors or activators of a specific enzyme target. High throughput screening requires the activity of the enzyme to be assayed in a simple format that may be adapted for use on large, highly automated systems Continu

- Continuous assay

a method for assaying an enzyme's activity in which signal generation is occurring concomitantly with enzyme activity (i.e., fluorescence)

- Discontinuous assay

any method for assaying an enzyme's activity in which signal generation requires arresting enzyme activity at specific time points and performing downstream processing steps to produce a signal (i.e., PAGE)

Footnotes

Notes: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA Damage Response: Making It Safe to Play with Knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cleaver JE. Defective Repair Replication of DNA in Xeroderma Pigmentosum. Nature. 1968;218:652–656. doi: 10.1038/218652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Setlow RB, Regan JD, German J, Carrier WL. Evidence that Xeroderma Pigmentosum Cells do not Perform the First Step in the Repair of Ultraviolet Damage to their DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;64:1035–1041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.64.3.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helleday T, Eshtad S, Nik-Zainal S. Mechanisms underlying mutational signatures in human cancers. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:585–598. doi: 10.1038/nrg3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung CH, Zhong HJ, He HZ, Lu L, Chan DSH, Ma DL. Luminescent oligonucleotide-based detection of enzymes involved with DNA repair. Chem Sci. 2013;4:3781–3795. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roos WP, Thomas AD, Kaina B. DNA damage and the balance between survival and death in cancer biology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;16:20–33. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2015.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Connor MJ. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell. 2015;60:547–560. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481:287–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sancar A, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Unsal-Kacmaz K, Linn S. Molecular Mechanisms of Mammalian DNA Repair and the DNA Damage Checkpoints. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:39–85. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972;11:3610–3618. doi: 10.1021/bi00769a018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klungland A, Lindahl T. Second pathway for completion of human DNA base excision-repair: reconstitution with purified proteins and requirement for DNase IV (FEN1) EMBO J. 1997;16:3341–3348. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.11.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen F, Tang Q, Bian K, Humulock ZT, Yang X, Jost M, Drennan CL, Essigmann JM, Li D. Adaptive Response Enzyme AlkB Preferentially Repairs 1-Methylguanine and 3-Methylthymine Adducts in Double-Stranded DNA. Chem Res Toxicol. 2016;29:687–693. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.5b00522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yufa R, Krylova SM, Bruce C, Bagg EA, Schofield CJ, Krylov SN. Emulsion PCR Significantly Improves Nonequilibrium Capillary Electrophoresis of Equilibrium Mixtures-Based Aptamer Selection: Allowing for Efficient and Rapid Selection of Aptamer to Unmodified ABH2 Protein. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1411–1419. doi: 10.1021/ac5044187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakao S, Mabuchi M, Shimizu T, Itoh Y, Takeuchi Y, Ueda M, Mizuno H, Shigi N, Ohshio I, Jinguji K, Ueda Y, Yamamoto M, Furukawa T, Aoki S, Tsujikawa K, Tanaka A. Design and synthesis of prostate cancer antigen-1 (PCA-1/ ALKBH3) inhibitors as anti-prostate cancer drugs. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:1071–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins AR. The comet assay for DNA damage and repair. Mol Biotechnol. 2004;26:249. doi: 10.1385/MB:26:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pearl LH, Schierz AC, Ward SE, Al-Lazikani B, Pearl FMG. Therapeutic opportunities within the DNA damage response. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15:166–180. doi: 10.1038/nrc3891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Molecular Beacons: Probes that Fluoresce upon Hybridization. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:303–308. doi: 10.1038/nbt0396-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biggins JB, Prudent JR, Marshall DJ, Ruppen M, Thorson JS. A continuous assay for DNA cleavage: The application of “break lights” to enediynes, iron-dependent agents, and nucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13537–13542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240460997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maksimenko A, Ishchenko AA, Sanz G, Laval J, Elder RH, Saparbaev MK. A molecular beacon assay for measuring base excision repair activities. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;319:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu B, Yang X, Wang K, Tan W, Li H, Tang H. Real-time monitoring of uracil removal by uracil-DNA glycosylase using fluorescent resonance energy transfer probes. Anal Biochem. 2007;366:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang X, Tong C, Long Y, Liu B. A rapidfluorescence assay for hSMUG1 activity based on modified molecularbeacon. Mol Cell Probes. 2011;25:219–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Long Y, Liu B, Xiang D, Zhu H. Real timemonitoring uracil excision using uracil-containing molecular beacons. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;819:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu B, Peng L. Real-time monitoring AP site incision caused by APE1 using a modified hybridization probe. Anal Methods. 2016;8:862–868. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang S, Chen L, Zhao M. Unimolecular Chemically Modified DNA Fluorescent Probe for One-Step Quantitative Measurement of the Activity of Human Apurinic/ Apyrimidinic Endonuclease 1 in Biological Samples. Anal Chem. 2015;87:11952–11956. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b03939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsumoto N, Toga T, Hayashi R, Sugasawa K, Katayanagi K, Ide H, Kuraoka I, Iwai S. Fluorescent probes for theanalysis of DNA strand scission in base excision repair. Nucleic AcidsRes. 2010;38:e101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lebedeva NA, Anarbaev RO, Kupryushkin MS, Rechkunova NI, Pyshnyi DV, Stetsenko DA, Lavrik OI. Design of a New Fluorescent Oligonucleotide-Based Assayfor a Highly Specific Real-Time Detection of Apurinic/ApyrimidinicSite Cleavage by Tyrosyl-DNA Phosphodiesterase 1. BioconjugateChem. 2015;26:2046–2053. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.5b00451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorjsuren D, Wilson DM, Beard WA, McDonald JP, Austin CP, Woodgate R, Wilson SH, Simeonov A. A real-time fluorescence method for enzymatic characterization of specialized human DNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e128–e128. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coggins GE, Maddukuri L, Penthala NR, Hartman JH, Eddy S, Ketkar A, Crooks PA, Eoff RL. N-Aroyl Indole Thiobarbituric Acids as Inhibitors of DNA Repair and Replication Stress Response Polymerases. ACS Chem Biol. 2013;8:1722–1729. doi: 10.1021/cb400305r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma C, Tang Z, Wang K, Tan W, Yang X, Li W, Li Z, Li H, Lv X. Real-Time Monitoring of Nucleic Acid Dephosphorylation by Using Molecular Beacons. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1487–1490. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirbahai L, Kershaw RM, Green RM, Hayden RE, Meldrum RA, Hodges NJ. Use of a molecular beacon to track the activity of base excision repair protein OGG1 in live cells. DNA Repair. 2010;9:144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dalhus B, Forsbring M, Helle IH, Vik ES, Forstrøm RJ, Backe PH, Alseth I, Bjøras M. Separation-of-Function Mutants Unravel the Dual-Reaction Mode of Human 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase. Structure. 2011;19:117–127. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donley N, Jaruga P, Coskun E, Dizdaroglu M, McCullough AK, Lloyd RS. Small Molecule Inhibitors of 8-Oxoguanine DNA Glycosylase-1 (OGG1) ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:2334–2343. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jacobs AC, Calkins MJ, Jadhav A, Dorjsuren D, Maloney D, Simeonov A, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, McCullough AK, Lloyd RS. Inhibition of DNA Glycosylases via Small Molecule Purine Analogs. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Zhang Q, Tang B, Zhang C. Single-Molecule Detection of Polynucleotide Kinase Based on Phosphorylation-Directed Recovery of Fluorescence Quenched by Au Nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2017;89:7255–7261. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H, Zhao Z, Lei Z, Wang Z. Sensitive Detection of Polynucleotide Kinase Activity by Paper-Based Fluorescence Assay with λ Exonuclease Assistance. Anal Chem. 2016;88:11358–11363. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gines G, Saint-Pierre C, Gasparutto D. On-bead fluorescent DNA nanoprobes to analyze base excision repair activities. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;812:168–175. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2013.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang Y, Zhao S, Shi M, Chen J, Chen ZF, Liang H. Intermolecular and Intramolecular Quencher Based Quantum Dot Nanoprobes for Multiplexed Detection of Endonuclease Activity and Inhibition. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8913–8918. doi: 10.1021/ac2013114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gines G, Saint-Pierre C, Gasparutto D. A multiplex assay based on encoded microbeads conjugated to DNA NanoBeacons to monitor base excision repair activities by flow cytometry. Biosens Bioelectron. 2014;58:81–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flaender M, Costa G, Nonglaton G, Saint-Pierre C, Gasparutto D. A DNA array based on clickable lesion-containing hairpin probes for multiplexed detection of base excision repair activities. Analyst. 2016;141:6208–6216. doi: 10.1039/c6an01165a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Ma F, Tang B, Zhang C. Base-Excision-Repair-Induced Construction of a Single Quantum-Dot-Based Sensor for Sensitive Detection of DNA Glycosylase Activity. Anal Chem. 2016;88:7523–7529. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhai J, Liu Y, Huang S, Fang S, Zhao M. A specific DNA-nanoprobe for tracking the activities of human apurinic/ apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 in living cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e45–e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen C, Zhou D, Tang H, Liang M, Jiang J. A sensitive, homogeneous fluorescence assay for detection of thymine DNA glycosylase activity based on exonuclease-mediated amplification. Chem Commun. 2013;49:5874–5876. doi: 10.1039/c3cc41700j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kong XJ, Wu S, Cen Y, Chen TT, Yu RQ, Chu X. Endonuclease IV cleaves apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in single-stranded DNA and its application for biosensing. Analyst. 2016;141:4373–4380. doi: 10.1039/c6an00738d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu ZM, Yu RQ, Chu X. Amplifiedfluorescence detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity andinhibition via a coupled λ exonuclease reaction and exonuclease III-aided trigger DNA recycling. Anal Methods. 2014;6:6009–6014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang X, Hou T, Lu T, Li F. AutonomousExonuclease III-Assisted Isothermal Cycling Signal Amplification: AFacile and Highly Sensitive Fluorescence DNA Glycosylase ActivityAssay. Anal Chem. 2014;86:9626–9631. doi: 10.1021/ac502125z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang LJ, Wang ZY, Zhang Q, Tang B, Zhang CY. Cyclic enzymatic repairing-mediated dual-signal amplificationfor real-time monitoring of thymine DNA glycosylase. Chem Commun. 2017;53:3878–3881. doi: 10.1039/c7cc00946a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Ren M, Zhang Q, Tang B, Zhang C. Excision Repair-Initiated Enzyme-Assisted Bicyclic Cascade Signal Amplification for Ultrasensitive Detection of Uracil-DNA Glycosylase. Anal Chem. 2017;89:4488–4494. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao M, Zhang J, Jin Y, Li B. Highly sensitive fluorescence assay of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity and inhibition via enzyme-assisted signal amplification. Anal Biochem. 2014;464:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L, Zhao J, Jiang J, Yu R. A target-activated autocatalytic DNAzyme amplification strategy for the assay of base excision repair enzyme activity. Chem Commun. 2012;48:8820–8822. doi: 10.1039/c2cc34531e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kong XJ, Wu S, Cen Y, Yu RQ, Chu X. Light-up” Sensing of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase activity by target-induced autocatalytic DNAzyme-generated rolling circle amplification. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;79:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.12.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiang Y, Lu Y. Expanding Targets of DNAzyme-Based Sensors through Deactivation and Activation of DNAzymes by Single Uracil Removal: Sensitive Fluorescent Assay of Uracil-DNA Glycosylase. Anal Chem. 2012;84:9981–9987. doi: 10.1021/ac302424f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leung CH, Chan DSH, Man BYW, Wang CJ, Lam W, Cheng YC, Fong WF, Hsiao WLW, Ma DL. Simple and Convenient G-Quadruplex-Based Turn-On Fluorescence Assay for 3′ → 5′ Exonuclease Activity. Anal Chem. 2011;83:463–466. doi: 10.1021/ac1025896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu D, Huang Z, Pu F, Ren J, Qu X. A Label-Free, Quadruplex-Based Functional Molecular Beacon (LFG4-MB) for Fluorescence Turn-On Detection of DNA and Nuclease. Chem - Eur J. 2011;17:1635–1641. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leung KH, He HZ, Ma VPY, Zhong HJ, Chan DSH, Zhou J, Mergny JL, Leung CH, Ma DL. Detection of base excision repair enzyme activity using a luminescent G-quadruplex selective switch-on probe. Chem Commun. 2013;49:5630–5632. doi: 10.1039/c3cc41129j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lu YJ, Hu DP, Deng Q, Wang ZY, Huang BH, Fang YX, Zhang K, Wong WL. Sensitive and selective detection of uracil-DNA glycosylase activity with a new pyridinium luminescent switch-on molecular probe. Analyst. 2015;140:5998–6004. doi: 10.1039/c5an01158b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.He HZ, Leung KH, Wang W, Chan DSH, Leung CH, Ma DL. Label-free luminescence switch-on detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity using a G-quadruplex-selective probe. Chem Commun. 2014;50:5313–5315. doi: 10.1039/c3cc47444e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ma C, Jin S, Liu H, Xia K, Tang J, Wang K, Wang J. Thioflavin T as a fluorescence probe for label-free detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase and its inhibitors. Mol Cell Probes. 2015;29:500–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mcp.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao H, Liu Q, Liu M, Jin Y, Li B. Label-free fluorescent assay of T4 polynucleotide kinase phosphatase activity based on G-quadruplexe-thioflavin T complex. Talanta. 2017;165:653–658. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guo Y, Wang Q, Wang Z, Chen X, Xu L, Hu J, Pei R. Label-free detection of T4 DNA ligase and polynucleotidekinase activity based on toehold-mediated strand displacement andsplit G-quadruplex probes. Sens Actuators, B. 2015;214:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu Y, Wang L, Jiang W. Toehold-mediatedstrand displacement reaction-dependent fluorescent strategy forsensitive detection of uracil-DNA glycosylase activity. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;89:984–988. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lin S, Kang TS, Lu L, Wang W, Ma DL, Leung CH. A G-quadruplex-selective luminescent probe with an anchor tail for the switch-on detection of thymine DNA glycosylase activity. Biosens Bioelectron. 2016;86:849–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.07.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong ZZ, Lu L, Wang W, Li G, Kang TS, Han Q, Leung CH, Ma DL. Luminescent detection of nicking endonuclease Nb.BsmI activity by using a G-quadruplex-selective iridium(III) complex in aqueous solution. Sens Actuators, B. 2017;246:826–832. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lu L, Shiu-Hin Chan D, Kwong DWJ, He HZ, Leung CH, Ma DL. Detection of nicking endonuclease activity using a G-quadruplex-selective luminescent switch-on probe. Chem Sci. 2014;5:4561–4568. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu Y, Wang L, Zhu J, Jiang W. A DNAmachine-based fluorescence amplification strategy for sensitivedetection of uracil-DNA glycosylase activity. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;68:654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Huang Y, Ma Y, Li Y, Xiong M, Li X, Zhang L, Zhao S. Sensitive and label-free fluorescence detection of apurinic/ apyrimidinic endonuclease 1 activity based on isothermal amplified-generation of G-quadruplex. New J Chem. 2017;41:1893–1896. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheng R, Tao M, Shi Z, Zhang X, Jin Y, Li B. Label-free and sensitive detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity via coupling DNA strand displacement reaction with enzymatic-aided amplification. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;73:138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2015.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rotaru A, Dutta S, Jentzsch E, Gothelf K, Mokhir A. Selective dsDNA-Templated Formation of Copper Nano-particles in Solution. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:5665–5667. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qing T, He X, He D, Ye X, Shangguan J, Liu J, Yuan B, Wang K. Dumbbell DNA-templated CuNPs as a nano-fluorescent probe for detection of enzymes involved in ligase-mediated DNA repair. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;94:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang L, Zhao J, Zhang H, Jiang J, Yu R. Double strand DNA-templated copper nanoparticle as a novel fluorescence indicator for label-free detection of polynucleotide kinase activity. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;44:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ge J, Zhang L, Dong ZZ, Cai QY, Li ZH. Sensitive and label-free T4 polynucleotide kinase/phosphatase detection based on poly(thymine)-templated copper nanoparticles coupled with nicking enzyme-assisted signal amplification. Anal Methods. 2016;8:2831–2836. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dong ZZ, Zhang L, Qiao M, Ge J, Liu AL, Li ZH. A label-free assay for T4 polynucleotide kinase/phosphataseactivity and its inhibitors based on poly(thymine)-templated coppernanoparticles. Talanta. 2016;146:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2015.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cao M, Jin Y, Li B. Simple and sensitive detection of uracil-DNA glycosylase activity using dsDNA-templated copper nanoclusters as fluorescent probes. Anal Methods. 2016;8:4319–4323. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li X, Xu X, Song J, Xue Q, Li C, Jiang W. Sensitive detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity based on multifunctional magnetic probes and polymerization nicking reactions mediated hyperbranched rolling circle amplification. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;91:631–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lian S, Liu C, Zhang X, Wang H, Li Z. Detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity based on cationicconjugated polymer-mediated fluorescence resonance energy transfer.Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015;66:316–320. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Summerer D, Rudinger NZ, Detmer I, Marx A. Enhanced Fidelity in Mismatch Extension by DNA Polymerasethrough Directed Combinatorial Enzyme Design. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2005;44:4712–4715. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gloeckner C, Kranaster R, Marx A. Current Protocols in Chemical Biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2009. Directed Evolution of DNA Polymerases: Construction and Screening of DNA Polymerase Mutant Libraries. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ma Y, Zhao J, Li X, Zhang L, Zhao S. A label free fluorescent assay for uracil-DNA glycosylase activity based on the signal amplification of exonuclease I. RSC Adv. 2015;5:80871–80874. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jean JM, Hall KB. 2-Aminopurine fluorescence quenching and lifetimes: Role of base stacking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:37–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011442198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu W, Chan KM, Kool ET. Fluorescent nucleobases as tools for studying DNA and RNA. Nat Chem. 2017;9:1043. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Krokan HE, Standal R, Slupphaug G. DNA glycosylases in the base excision repair of DNA. Biochem J. 1997;325:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3250001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stivers JT, Pankiewicz KW, Watanabe KA. Kinetic mechanism of damage site recognition and uracil flipping by Escherichia coli uracil DNA glycosylase. Biochemistry. 1999;38:952–963. doi: 10.1021/bi9818669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bellamy SRW, Krusong K, Baldwin GS. A rapid reaction analysis of uracil DNA glycosylase indicates an active mechanism of base flipping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Walker RK, McCullough AK, Lloyd RS. Uncoupling of Nucleotide Flipping and DNA Bending by the T4 Pyrimidine Dimer DNA Glycosylase †. Biochemistry. 2006;45:14192–14200. doi: 10.1021/bi060802s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Christine KS, MacFarlane AW, Yang K, Stanley RJ. Cyclobutylpyrimidine Dimer Base Flipping by DNA Photolyase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38339–38344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yang K, Matsika S, Stanley RJ. 6MAP, a Fluorescent Adenine Analogue, Is a Probe of Base Flipping by DNA Photolyase. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10615–10625. doi: 10.1021/jp071035p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zang H, Fang Q, Pegg AE, Guengerich FP. Kinetic Analysis of Steps in the Repair of Damaged DNA by Human O6-Alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30873–30881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ma C, Liu H, Du J, Chen H, He H, Jin S, Wang K, Wang J. Quencher-free hairpin probes for real-time detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity. Anal Biochem. 2016;494:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tao M, Shi Z, Cheng R, Zhang J, Li B, Jin Y. Highly specific fluorescence detection of T4 polynucleotide kinase activity via photo-induced electron transfer. Anal Biochem. 2015;485:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Song C, Zhao M. Anal. Chem. 2009;81(4):1383–1388. doi: 10.1021/ac802107w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moser AM, Patel M, Yoo H, Balis FM, Hawkins ME. Real-Time Fluorescence Assay for O6-Alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase. Anal Biochem. 2000;281:216–222. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee CY, Park KS, Park HG. Pyrrolo-dC modified duplex DNA as a novel probe for the sensitive assay of base excision repair enzyme activity. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;98:210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2017.06.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lee CY, Park KS, Park HG. A fluorescent G-quadruplex probe for the assay of base excision repair enzyme activity. Chem Commun. 2015;51:13744–13747. doi: 10.1039/c5cc05010c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Y, Li C, Tang B, Zhang C. Homogeneously Sensitive Detection of Multiple DNA Glycosylases with Intrinsically Fluorescent Nucleotides. Anal Chem. 2017;89:7684–7692. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b01655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ono T, Wang S, Koo CK, Engstrom L, David SS, Kool ET. Direct Fluorescence Monitoring of DNA Base Excision Repair. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:1689–1692. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jung JW, Edwards SK, Kool ET. Selective fluorogenic chemosensors for distinct classes of nucleases. Chem-BioChem. 2013;14:440–444. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ono T, Edwards SK, Wang S, Jiang W, Kool ET. Monitoring eukaryotic and bacterial UDG repair activity with DNA-multifluorophore sensors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:e127. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Edwards SK, Ono T, Wang S, Jiang W, Franzini RM, Jung JW, Chan KM, Kool ET. In Vitro Fluorogenic Real-Time Assay of the Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:1637–1646. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beharry AA, Lacoste S, O'Connor TR, Kool ET. Fluorescence Monitoring of the Oxidative Repair of DNA Alkylation Damage by ALKBH3, a Prostate Cancer Marker. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:3647–3650. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wilson JN, Cho Y, Tan S, Cuppoletti A, Kool ET. Quenching of Fluorescent Nucleobases by Neighboring DNA:The “Insulator” Concept. ChemBioChem. 2008;9:279–285. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Edwards SK, Ono T, Wang S, Jiang W, Franzini RM, Jung JW, Chan KM, Kool ET. In Vitro Fluorogenic Real-Time Assay of the Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. ChemBioChem. 2015;16:1637–1646. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bacsi A, Aguilera-Aguirre L, Szczesny B, Radak Z, Hazra TK, Sur S, Ba X, Boldogh I. Down-regulation of 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 expression in the airway epithelium ameliorates allergic lung inflammation. DNA Repair. 2013;12:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Beharry AA, Lacoste S, O'Connor TR, Kool ET. Fluorescence Monitoring of the Oxidative Repair of DNA Alkylation Damage by ALKBH3, a Prostate Cancer Marker. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:3647–3650. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roguev A, Russev G. Two-WavelengthFluorescence Assay for DNA Repair. Anal Biochem. 2000;287:313–318. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen Y, Huang C, Bai C, Du C, Liao J, Dong Q. In vivo DNA mismatch repair measurement in zebrafishembryos and its use in screening of environmental carcinogens. J Hazard Mater. 2016;302:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lei X, Zhu Y, Tomkinson A, Sun L. Measurement of DNA mismatch repair activity in live cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e100. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou B, Huang C, Yang J, Lu J, Dong Q, Sun LZ. Preparation of heteroduplex enhanced green fluorescentprotein plasmid for in vivo mismatch repair activity assay. Anal Biochem. 2009;388:167–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nagel ZD, Margulies CM, Chaim IA, McRee SK, Mazzucato P, Ahmad A, Abo RP, Butty VL, Forget AL, Samson LD. Multiplexed DNA repair assays for multiple lesions and multiple doses via transcription inhibition and transcriptional mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E1823–E1832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401182111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chaim IA, Nagel ZD, Jordan JJ, Mazzucato P, Ngo LP, Samson LD. In vivo measurements of interindividual differences in DNA glycosylases and APE1 activities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017:201712032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1712032114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chaim IA, Gardner A, Wu J, Iyama T, Wilson DM, Samson LD. A novel role for transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair for the in vivo repair of 3,N4-ethenocytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:3242–3252. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Certo MT, Ryu BY, Annis JE, Garibov M, Jarjour J, Rawlings DJ, Scharenberg AM. Tracking genome engineering outcome at individual DNA breakpoints. Nat Methods. 2011;8:671–676. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Gomez-Cabello D, Jimeno S, Fernandez-Avila MJ, Huertas P. New Tools to Study DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77206. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN. A Graphene Platform for Sensing Biomolecules. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:4785–4787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu W, Hu H, Li F, Wang L, Gao J, Lu J, Fan C. A graphene oxide-based nano-beacon for DNA phosphorylation analysis. Chem Commun. 2011;47:1201–1203. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04312e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhu W, Zhao Z, Li Z, Jiang J, Shen G, Yu R. A graphene oxide platform for the assay of DNA 3′-phosphatases and their inhibitors based on hairpin primer and polymerase elongation. J Mater Chem B. 2013;1:361–367. doi: 10.1039/c2tb00109h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhou DM, Xi Q, Liang MF, Chen CH, Tang LJ, Jiang JH. Graphene oxide-hairpin probe nanocomposite as a homogeneous assay platform for DNA base excision repair screening. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;41:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xi Q, Li JJ, Du WF, Yu RQ, Jiang JH. A highly sensitive strategy for base excision repair enzyme activity detection based on graphene oxide mediated fluorescence quenching and hybridization chain reaction. Analyst. 2016;141:96–99. doi: 10.1039/c5an02255j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu X, Ge J, Wang X, Wu Z, Shen G, Yu R. Development of a highly sensitive sensing platform for T4 polynucleotide kinase phosphatase and its inhibitors based on WS2 nanosheets. Anal Methods. 2014;6:7212–7217. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wang Z, Li Y, Li L, Li D, Huang Y, Nie Z, Yao S. DNA-mediated supercharged fluorescent protein/grapheneoxide interaction for label-free fluorescence assay of base excisionrepair enzyme activity. Chem Commun. 2015;51:13373–13376. doi: 10.1039/c5cc04759e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sun X, Liu Z, Welsher K, Robinson JT, Goodwin A, Zaric S, Dai H. Nano-graphene oxide for cellular imaging and drug delivery. Nano Res. 2008;1:203–212. doi: 10.1007/s12274-008-8021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jang H, Ryoo SR, Lee MJ, Han SW, Min DH. A New Helicase Assay Based on Graphene Oxide for Anti-Viral Drug Development. Mol Cells. 2013;35:269–273. doi: 10.1007/s10059-013-0066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wang Y, Li Z, Hu D, Lin CT, Li J, Lin Y. Aptamer/Graphene Oxide Nanocomplex for in Situ Molecular Probing in Living Cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:9274–9276. doi: 10.1021/ja103169v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gerson SL. MGMT: its role in cancer aetiology and cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:296–307. doi: 10.1038/nrc1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Damoiseaux R, Keppler A, Johnsson K. Synthesis and Applications of Chemical Probes for Human O6-Alkylguanine-DNA Alkyltransferase. ChemBioChem. 2001;2:285. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20010401)2:4<285::AID-CBIC285>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Keppler A, Gendreizig S, Gronemeyer T, Pick H, Vogel H, Johnsson K. A general method for the covalent labeling of fusion proteins with small molecules in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:86–89. doi: 10.1038/nbt765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]