Abstract

Background: Well-differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) represents the thyroid neoplasia with the highest incidence. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have been found deregulated in several human carcinomas, and hence, proposed as potential diagnostic and prognostic markers. Therefore, the aim of our study was to investigate their role in thyroid carcinogenesis. Methods: We analysed the lncRNA expression profile of 12 PTC and four normal thyroid tissues through a lncRNA microarray. Results: We identified 669 up- and 2470 down-regulated lncRNAs with a fold change >2. Among them, we focused on the down-regulated RP5-1024C24.1 located in an antisense position with respect to the MPPED2 gene which codes for a metallophosphoesterase with tumour suppressor activity. Both these genes are down-regulated in benign and malignant thyroid neoplasias. The restoration of RP5-1024C24.1 expression in thyroid carcinoma cell lines reduced cell proliferation and migration by modulating the PTEN/Akt pathway. Inhibition of thyroid carcinoma cell growth and cell migration ability was also achieved by the MPPED2 restoration. Interestingly, RP5-1024C24.1 over-expression is able to increase MPPED2 expression. Conclusions: Taken together, these results demonstrate that RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 might be considered as novel tumour suppressor genes whose loss of expression contributes to thyroid carcinogenesis.

Keywords: long non-coding RNA, MPPED2, thyroid carcinoma, tumour suppressor, carcinogenesis

1. Introduction

Thyroid carcinomas are moderately rare, constituting 1% of all human carcinomas, but represent the highest percentage of all malignancies derived from the endocrine system [1]. Neoplasias resulting from thyroid follicular cells consist of a wide spectrum of lesions with increasing degree of malignancies going from benign follicular thyroid adenomas (FTA), to differentiated carcinomas (papillary thyroid carcinomas, PTC, and follicular thyroid carcinomas, FTC), to completely undifferentiated carcinomas (anaplastic thyroid carcinomas, ATC) that are always fatal [2]. Among thyroid carcinomas, PTC is the most frequent histotype representing about 80% of all diagnosed thyroid carcinomas. Some genetic mutations are already known to be involved in PTC development, such as RET/PTC rearrangement [3,4,5], BRAF and RAS mutations [6,7,8,9]. Moreover, microRNA (miRNA) deregulated expression has been frequently described in human thyroid carcinomas [10]. However, most of the molecular mechanisms underlying thyroid carcinogenesis have not been completely elucidated yet.

In order to better understand the basic mechanisms involved in thyroid carcinogenesis, a great interest has been recently raised by long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), single-strand RNA molecules with a length that varies between 200 and 100,000 nucleotides. They are classified in five different groups on the basis of their position in the genome (sense, antisense, bidirectional, intronic, intergenic) [11,12].

Currently, their molecular action mechanisms and their role played in gene expression regulation have not been clarified, but it has been demonstrated that they can modulate gene expression by inducing histonic epigenetic modifications or acting as “sponge” for miRNAs, thus playing a role in both normal biological processes and diseases, including cancer [13,14,15,16,17]. Moreover, recent evidence has shown that lncRNAs are deregulated in several neoplasias depending on the tumour histotype, proposing their detection as an important tool in cancer diagnosis and prognosis [18,19,20].

Therefore, in order to identify deregulated lncRNAs in thyroid neoplasias and unveil their role in thyroid carcinogenesis, we analysed the expression profile of 12 PTC versus four normal thyroid tissues. Several lncRNAs differentially expressed in PTC compared to normal thyroid tissues were identified. Then, we focused on the lncRNA RP5-1024C24.1 that was also down-regulated in FTA, FTC and ATC. Interestingly, the expression of MPPED2, its associated gene, was significantly decreased in the thyroid carcinoma samples analysed, suggesting a role of both these genes in thyroid carcinogenesis. Accordingly, the stable restoration of both RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 expression was able to attenuate proliferation and migration rate of thyroid cancer cell lines, suggesting a role of both these genes in thyroid cancer progression.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of LncRNAs Deregulated in Human PTC

In order to identify the lncRNAs deregulated in PTC, we analysed the lncRNA expression profile of 12 PTC and four normal thyroid tissues (see Supplementary Material, Table S1) by hybridizing the RNA extracted from these samples to the Human LncRNA Microarray Version 3.0 (Arraystar, Rockville, MD, USA). After hybridization and normalization of the raw data, we obtained through bioinformatic analysis a list of 669 and 2470 lncRNAs that resulted up- and down-regulated, respectively, in the PTC tissues analysed compared to normal thyroid samples with fold change >2 and p-value < 0.05. The complete list of up- and down-regulated lncRNAs is provided in Supplementary Material (Table S2). A representative partial list of deregulated lncRNAs is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Representative list of lncRNAs deregulated in papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTC) vs. normal thyroid tissues (NT) 1.

| Up-Regulated LncRNAs (PTC vs. NT) | |||||||

| Gene Symbol | Seqname | Fold Change | p -Value | Chr. | Strand | Relationship | Associated Gene |

| XLOC_010052 | TCONS_00020760 | 44.796062 | 0.011679098 | chr12 | − | intergenic | |

| EGFEM1P | ENST00000488647 | 29.21525 | 0.003039263 | chr3 | + | intergenic | |

| RP11-230G5.2 | ENST00000538294 | 16.403324 | 0.003381364 | chr12 | − | natural antisense | MSRB3 |

| AC008079.9 | ENST00000434390 | 15.255612 | 0.017524553 | chr22 | − | intergenic | |

| RP11-353N14.2 | ENST00000576963 | 14.603789 | 6.1 × 10−5 | chr17 | + | intergenic | |

| AC079630.2 | ENST00000457989 | 12.705946 | 0.00535464 | chr12 | + | intergenic | LRRK2 |

| CTC-255N20.1 | ENST00000504297 | 6.02792 | 0.001935031 | chr5 | − | bidirectional | STK32A |

| AC003102.3 | ENST00000453562 | 5.626362 | 7.34 × 10−4 | chr17 | − | natural antisense | RUNDC3A |

| DLEU2 | uc001vdo.1 | 4.361354 | 9.4 × 10−4 | chr13 | − | natural antisense | TRIM13 |

| RP11-4C20.4 | ENST00000433110 | 3.8502407 | 0.035742607 | chr10 | + | intron sense-overlapping | PTPRE |

| Down-Regulated LncRNAs (PTC vs. NT) | |||||||

| Gene Symbol | Seqname | Fold Change | p -Value | Chr. | Strand | Relationship | Associated Gene |

| CTB-85P21.2 | ENST00000566630 | 72.72284 | 6.38 × 10−7 | chr5 | + | intergenic | |

| SLC26A4-AS1 | NR_028137 | 27.245485 | 0.006468582 | chr7 | − | natural antisense | SLC26A4 |

| RP11-317P15.5 | ENST00000570153 | 20.019192 | 0.007198248 | chr1 | − | intergenic | |

| RP1-240B8.3 | ENST00000511849 | 17.767982 | 0.001431982 | chr6 | − | exon sense-overlapping | KHDRBS2 |

| ZFY-AS1 | ENST00000417305 | 14.560697 | 0.017612867 | chrY | − | natural antisense | ZFY |

| LA16c-329F2.1 | ENST00000570022 | 12.498036 | 0.031231718 | chr16 | − | intronic antisense | MAPK8IP3 |

| RP5-1024C24.1 | ENST00000531002 | 10.285704 | 7.4 × 10−6 | chr11 | + | intronic antisense | MPPED2 |

| AC002066.1 | ENST00000439070 | 9.467349 | 8.22 × 10−4 | chr7 | − | intergenic | |

| ST7-AS1 | NR_002330 | 8.9516325 | 1.38 × 10−4 | chr7 | − | natural antisense | ST7 |

| RP11-121G22.3 | ENST00000553197 | 8.723473 | 5.89 × 10−6 | chr12 | + | intronic antisense | PPFIA2 |

1 For each lncRNA we report the gene symbol, accession number, the fold change expression compared to normal thyroid tissues, the p-value of the analysis, the chromosome and the DNA strand in which they are located, their classification and the name of their associated gene on the genome.

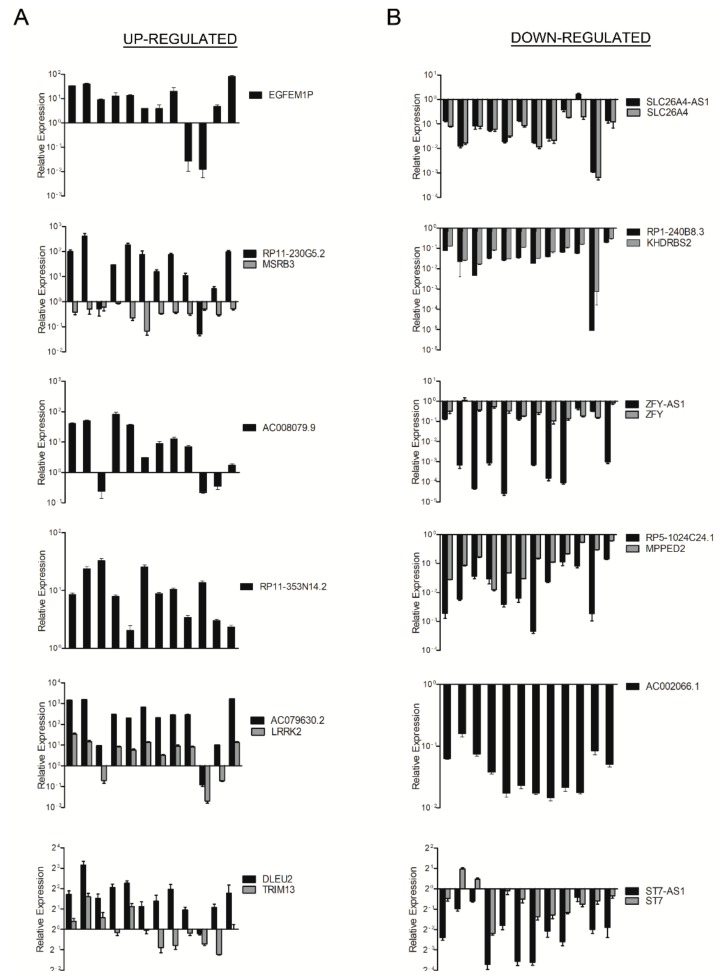

To validate the results obtained by the microarray analysis, we selected six up- (EGFEM1P, RP11-230G5.2, AC008079.9, RP11-353N14.2, AC079630.2 and DLEU2) and six down-regulated lncRNAs (SLC26A4-AS1, RP1-240B8.3, ZFY-AS1, RP5-1024C24.1, AC002066.1 and ST7-AS1) with respect to normal thyroid tissues. Then, we evaluated their expression by qRT-PCR in the same PTC and normal thyroid samples previously used for the lncRNA microarray thus confirming the results obtained. In fact, as shown in Figure 1A,B, we found that the expression of EGFEM1P, RP11-230G5.2, AC008079.9, RP11-353N14.2, AC079630.2 and DLEU2 was up-regulated in PTC, while the expression of SLC26A4-AS1, RP1-240B8.3, ZFY-AS1, RP5-1024C24.1, AC002066.1 and ST7-AS1 resulted down-regulated. Moreover, we selected the lncRNAs RP11-230G5.2, DLEU2 and SCL26A4-AS1 and analysed their expression levels in additional 12 PTC comparing them to the mean of three normal thyroid tissues (three out of the four normal thyroid samples used for microarray hybridization and validation, see Materials and Methods section). By qRT-PCR, we observed also in this case an up-regulation of RP11-230G5.2 and DLEU2, and a down-regulation of SCL26A4-AS1, thus supporting the lncRNA microarray analysis (see Supplementary Material, Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Analysis of lncRNA and gene expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). Total RNA extracted from 12 PTC and four normal thyroid samples was hybridized to a lncRNA microarray. qRT-PCR analysis was performed to evaluate the expression of up-regulated (A) and down-regulated (B) lncRNAs and their associated genes. Results are reported as relative expression ± SEM compared to the mean of four normal thyroid samples set equal to 1.

As shown in Table S2, the lncRNAs identified were classified on the basis of their genomic orientation with respect to their neighbouring genes in exon-sense overlapping, intron-sense overlapping, intronic antisense, natural antisense, bidirectional and intergenic [11,12]. Since several studies have recently demonstrated that lncRNAs frequently act through the modulation of their associated neighbouring gene expression [21,22,23,24,25,26], we focused our attention on the antisense class of lncRNAs for further investigations. By the lncRNA microarray analysis, we observed the following association between lncRNAs and related genes: RP11-230G5.2, antisense with respect to the MSRB3 gene; AC079630.2, intergenic with respect to the LRRK2 gene; DLEU2, antisense with respect to the TRIM13 gene; SLC26A4-AS1, antisense with respect to the SLC26A4 gene; RP1-240B8.3 antisense with respect to the KHDRBS2 gene; ZFY-AS1, antisense with respect to the ZFY gene; RP5-1024C24.1, antisense with respect the MPPED2 gene; ST7-AS1, antisense with respect to the ST7 gene (Table 1 and Table S2). Therefore, we evaluated, by qRT-PCR, the expression of the selected lncRNA-associated genes in the same PTC and normal thyroid microarray samples. Interestingly, we found a positive association between the lncRNAs and their related gene expression in six out of eight lncRNA/neighbouring-gene pairs analysed (Figure 1A,B). Conversely, a negative association was observed between RP11-230G5.2 and MSRB3 expression, and no association was observed between DLEU2 and TRIM13 expression (Figure 1A).

2.2. Analysis of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 Expression in Neoplastic Thyroid Diseases

To characterize the role of lncRNAs in thyroid carcinogenesis, we decided to focus our study on the lncRNA RP5-1024C24.1, located on chromosome 11 in antisense position with respect to the MPPED2 gene encoding a metallophosphoesterase protein. We made this choice since both of them were drastically down-regulated in all the PTC samples analysed by the lncRNA microarray, and then by qRT-PCR. Moreover, MPPED2 gene has been already reported to play an important anti-oncogenic role in oral squamous cell carcinoma [27], cervical cancer [28] and neuroblastoma [29]. Therefore, we decided to further investigate the functional role of the lncRNA RP5-1024C24.1 and its associated MPPED2 gene in human thyroid carcinomas and their possible relationship in thyroid cancer.

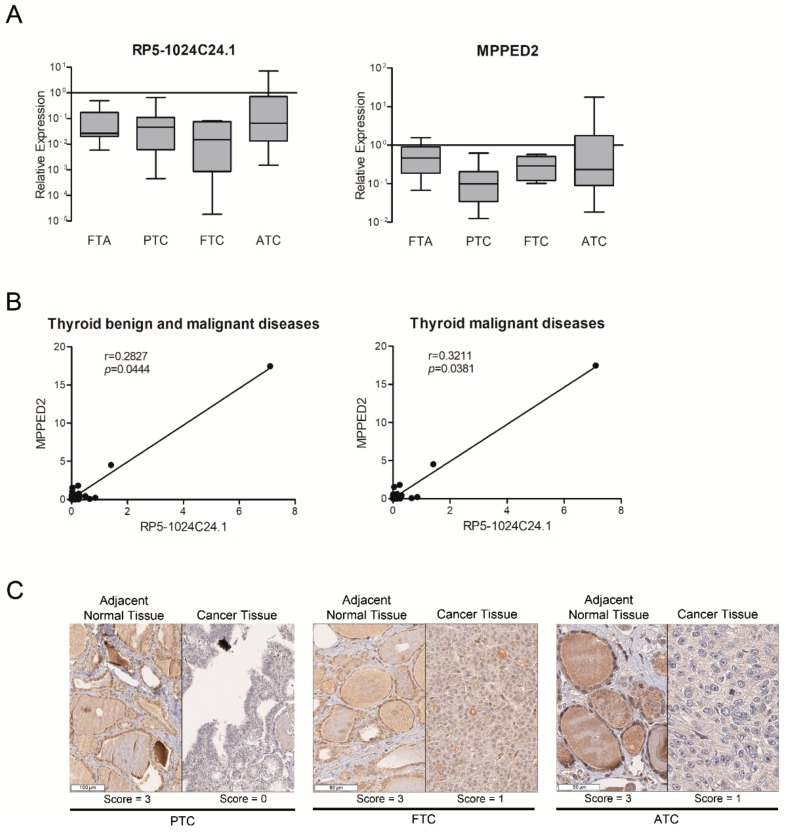

To this aim, we analysed by qRT-PCR the expression levels of both RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 in a set of nine FTA samples, additional 12 PTC samples, six FTC and 12 ATC and compared them to the mean of three normal thyroid tissues (three out of the four normal thyroid samples used for microarray hybridization and validation, see Materials and Methods section). As shown in Figure 2A, we observed a reduced expression of both genes with respect to normal thyroid tissues in all the thyroid neoplastic histotypes analysed, including the FTA samples. Moreover, we found a significant (p = 0.0444) positive correlation between their expression in the whole neoplasm set analysed, suggesting that both RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 are co-regulated during the process of thyroid carcinogenesis (Figure 2B, left panel). The positive correlation between RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 expression was still significant when we consider only the thyroid malignant samples (PTC, FTC, ATC) (p = 0.0381) (Figure 2B, right panel). These results were then confirmed at the protein level by immunohistochemical analysis using an anti-MPPED2 antibody. In fact, reduced MPPED2 protein levels were found in 37% of FTA (7 out of 19 cases), 79% of PTC (116 out of 147 cases), 77% of FTC (23 out of 30 cases), 86% of PDC (32 out of 37 cases) and 53% of ATC (8 out of 15 cases) in comparison to normal matched thyroid tissue (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 expression in thyroid neoplastic diseases. (A) qRT-PCR analysis performed on FTA (n = 9), PTC (n = 12 previously used for lncRNA microarray hybridization and n = 12 additional samples), FTC (n = 6), ATC (n = 12) to evaluate the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 (left panel) and MPPED2 (right panel). Results are reported as relative expression compared to the mean of normal thyroid samples, set equal to 1 (box and whiskers, min to max). (B) Correlation scatterplot (Spearman test) of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 mRNA levels (relative expression) in thyroid benign and malignant diseases (FTA, PTC, FTC, ATC) (left panel). Correlation scatterplot (Spearman test) of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 mRNA levels (relative expression) in thyroid carcinomas (PTC, FTC, ATC) (right panel). (C) Representative immunohistochemical staining of MPPED2 protein in thyroid carcinoma samples (PTC, FTC, ATC) and in their corresponding adjacent normal tissue. The MPPED2 signal is strong in normal thyroid tissues (Score = 3) and mild (Score = 1) or absent (Score = 0) in thyroid carcinoma tissues (magnification 40×).

Table 2.

Expression of MPPED2 protein levels in thyroid neoplasias analysed by immunohistochemistry.

| Histotype (n) | Reduced Expression 1 (n, %) | Whole Cohort |

|---|---|---|

| FTA 2 (n = 19) | n = 7 (37%) | p < 0.001 |

| PTC 3 (n = 147) | n = 116 (79%) | p < 0.001 |

| FTC 4 (n = 30) | n = 23 (77%) | p < 0.001 |

| PDC 5 (n = 37) | n = 32 (86%) | p < 0.001 |

| ATC 6 (n = 15) | n = 8 (53%) | p = 0.003 |

| Whole cohort p < 0.001 | ||

1 MPPED2 protein expression in thyroid carcinoma vs. the adjacent corresponding normal thyroid tissue; 2 FTA, follicular thyroid adenoma; 3 PTC, papillary thyroid carcinoma; 4 FTC, follicular thyroid carcinoma; 5 PDC, poorly differentiated carcinoma; 6 ATC, anaplastic thyroid carcinoma.

Representative results are shown in Figure 2C. The signal corresponding to MPPED2 was strong (Score = 3) with a granular cytoplasmic expression in the normal tissues. Conversely, in the paired PTC, FTC and ATC samples shown in the same figure, the signal corresponding to MPPED2 was completely absent (Score = 0) or mild and non-granular (Score = 1) (see Materials and Methods section). Statistical analyses of MPPED2 expression in thyroid carcinoma samples compared to their adjacent normal tissue reveal significant differences between tumours and their corresponding normal tissue in the following categories: whole cohort (p < 0.001), PTC (p < 0.001), FTC (p < 0.001), PDC (p < 0.001), ATC (p = 0.003) (Table 2). We did not observe any significant differences of MPPED2 expression levels between the different histological groups. Moreover, as far as the association of differential MPPED2 expression between tumour and normal matched samples with clinico-pathological information is concerned, we did not find any significant correlation with the TNM stage, morphological tumour characteristics and the mutational status of specific thyroid cancer-related genes (data not shown).

2.3. Down-Regulation of RP5-1024C24.1 Expression Contributes to Thyroid Carcinogenesis by Affecting the PTEN/Akt Pathway

Subsequently, to better define the role of RP5-1024C24.1 in thyroid carcinogenesis, we modulated its expression in thyroid carcinoma cell lines. To achieve this aim, we first analysed the expression of this gene by qRT-PCR in a panel of thyroid carcinoma cell lines, including TPC-1 and B-CPAP (PTC-derived cell lines), WRO (FTC-derived cell line) and FB-1 and FRO (ATC-derived cell lines). As shown in Figure S2, the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 was much lower in all the cell lines analysed in comparison with three normal thyroid samples used as control (see Materials and Methods section).

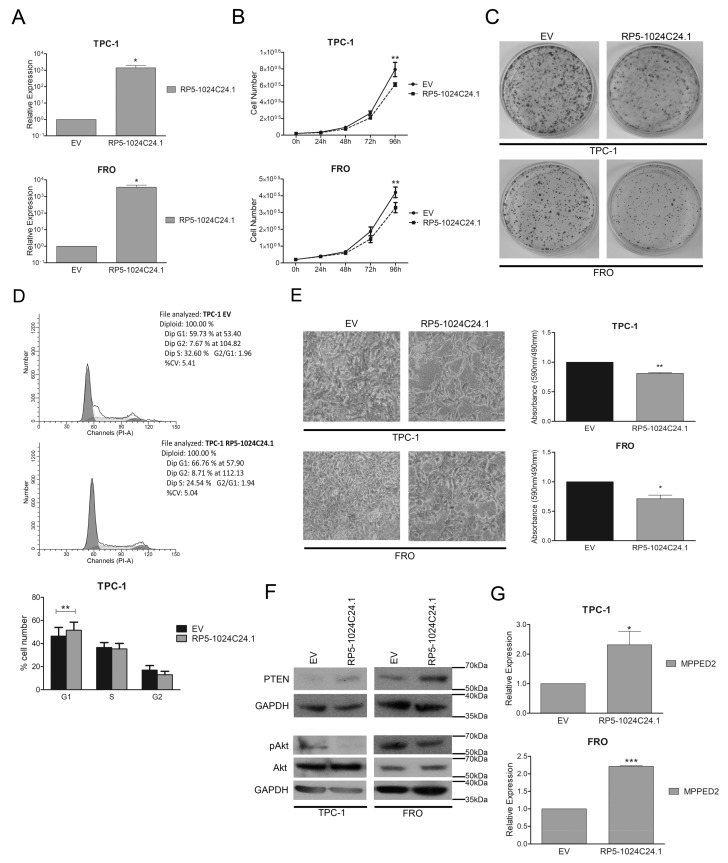

Then, we restored the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 in TPC-1 and FRO cell lines by transfecting them with a vector expressing the lncRNA and selected the transfected cells in a G418-containing medium. Next, we confirmed by qRT-PCR the restoration of RP5-1024C24.1 expression in the selected cells (Figure 3A and Figure S3A) and evaluated its effects on cell proliferation. As shown in Figure 3B, both TPC-1 and FRO cells expressing RP5-1024C24.1 displayed a significant reduction in the cell growth rate compared to the respective empty vector transfected cells. Consistently, cell colony-forming assays evidenced that RP5-1024C24.1 reduces the number of colonies compared to the control cells (Figure 3C), thus confirming that RP5-1024C24.1 is able to negatively modulate the cell proliferation of both PTC and ATC cells.

Figure 3.

RP5-1024C24.1 reduces cell migration and proliferation of thyroid carcinoma cell lines. (A) qRT-PCR analysis performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or the corresponding empty vector (EV). Results were obtained from four independent experiments. Data were compared to EV, set equal to 1, and reported as relative expression ± SEM. t-test; * p < 0.05. (B) Cell growth analysis of TPC-1 and FRO stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or EV. Cell number was evaluated at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h after seeding. Values were obtained from three independent experiments performed in duplicate. Data were reported as mean ± SEM. 2-way Anova-test followed by Bonferroni post-test; ** p < 0.01. (C) Representative colony assay performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or EV. (D) Representative cell cycle analysis of TPC-1 cell lines stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or EV. Cell number was reported on the y-axis while the percentage of propidium iodide (PI) incorporated was reported on the x-axis (upper panel). Values shown in the lower panel were obtained from five independent experiments. t-test; ** p < 0.01 compared to EV cells. (E) Representative acquisition of migration assays performed on TPC-1 and FRO stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or EV (magnification 40×) (left panel). Data obtained from three (TPC-1) or four (FRO) independent experiments are shown in the right panel. Values were reported as mean value ± SEM and compared to the EV, set equal to 1. t-test; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01. (F) Immunoblot analysis performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably carrying RP5-1024C24.1 or EV to analyze the protein level of PTEN, Akt and pAkt. GAPDH was used to normalize the amount of loaded protein. (G) MPPED2 expression evaluated by qRT-PCR in TPC-1 and FRO stably expressing RP5-1024C24.1. Data were obtained from five (TPC-1) or three (FRO) independent experiments. Values were reported as relative expression ± SEM and were compared to the EV, set equal to 1. t-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001.

Cell cycle analysis performed by flow cytometry showed that RP5-1024C24.1 increased the number of TPC-1 cells in the G1 phase compared to the empty vector (TPC-1-EV, G1: 59.73%; TPC-1-RP5-1024C24.1, G1: 66.76%; p = 0.0092) (Figure 3D). Moreover, to verify whether the restoration of RP5-1024C24.1 has an effect on other cancer-associated processes as well, we analysed the cell migration rate of TPC-1 and FRO stably expressing RP5-1024C24.1 by transwell assays after inhibiting cell proliferation with mytomicin C. As shown in Figure 3E, we found that the restoration of the lncRNA expression was also able to reduce the migration ability of the selected thyroid carcinoma cell lines.

Next, to characterize the molecular mechanisms by which the lncRNA RP5-1024C24.1 may act, we evaluated the expression of PTEN, a well-known oncosuppressor protein [30,31], in TPC-1 and FRO cells stably expressing the lncRNA. By western blot analysis, we found that RP5-1024C24.1 is able to increase PTEN levels (Figure 3F, upper panel). In addition, we analysed the effect of the PTEN induction on its down-stream effector Akt [32,33] and found that cells expressing RP5-1024C24.1 showed a reduced Akt phosphorylation on Ser473 (Figure 3F, lower panel) resulting in the reduction of its activation [34].

Therefore, these results indicate that RP5-1024C24.1 can affect cell proliferation and migration through a mechanism that involves the modulation of the PTEN/Akt pathway, further supporting the anti-oncogenic role played by RP5-1024C24.1 in thyroid carcinogenesis.

2.4. MPPED2 Is Induced by RP5-1024C24.1 and Negatively Modulates Cell Proliferation and Migration of Thyroid Carcinoma Cell Lines

To investigate whether RP5-1024C24.1 modulates the expression of its-associated MPPED2 gene, we analysed the expression of MPPED2 by qRT-PCR in TPC-1 and FRO stably expressing RP5-1024C24.1. Interestingly, we found that RP5-1024C24.1 is able to increase the expression of MPPED2 in both cell lines with respect to the empty vector transfected cells, thus suggesting that the lncRNA may act also through the modulation of the MPPED2 expression (Figure 3G).

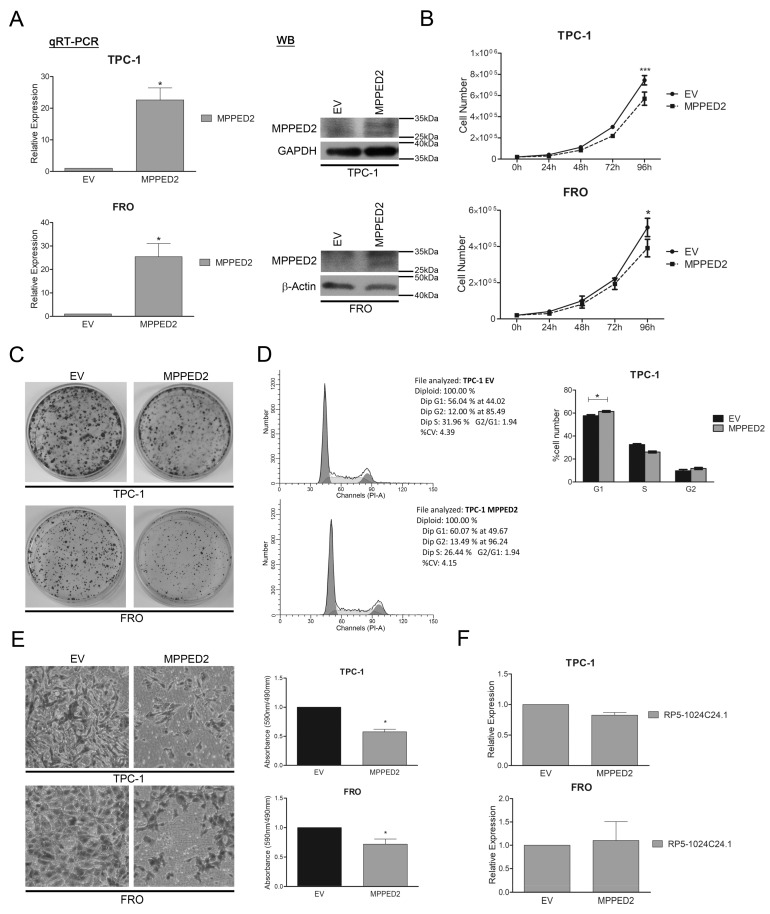

Next, to characterize the role that this gene plays in thyroid carcinogenesis, we analysed by qRT-PCR the expression of MPPED2 in a panel of thyroid carcinoma cell lines (Figure S2) and then we stably restored its expression in TPC-1 and FRO cell lines. After G418 selection, we confirmed the increased expression of MPPED2 in the transfected cells (Figure 4A and Figure S3B) and evaluated its functional effects. As displayed in Figure 4B,C, the growth curve and colony formation assays showed that both the MPPED2-transfected TPC-1 and FRO cells have a lower proliferation rate than cells carrying the empty vector. Moreover, cell cycle progression analysis performed on TPC-1 cells through flow cytometry confirmed the negative effect of MPPED2 on cell proliferation by showing an increased percentage of cells in the G1 phase when compared to cells carrying the empty vector (TPC-1-EV, G1: 56.04%; TPC-1-MPPED2, G1: 60.07%; p = 0.0367) (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

MPPED2 negatively modulates cell proliferation and migration of thyroid carcinoma cell lines. (A) qRT-PCR analysis performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably carrying MPPED2 or the corresponding empty vector (EV). Values were reported as relative expression ± SEM and were compared to EV, set equal to 1. t-test; * p < 0.05 (left panel). Immunoblot analysis confirming the expression of MPPED2. GAPDH and β-Actin were used to normalize the amount of loaded protein (right panel). (B) Cell growth analysis of TPC-1 and FRO stably carrying MPPED2 or EV. Cell number was evaluated at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h after seeding. Values were obtained from three independent experiments performed in duplicate and data were reported as mean ± SEM. 2-way Anova-test followed by Bonferroni post-test; * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001. (C) Representative colony assay performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably carrying MPPED2 or EV. (D) Representative cell cycle analysis of TPC-1-MPPED2 and TPC-1-EV cells. Cell number was reported on the y-axis while the percentage of propidium iodide (PI) incorporated was reported on the x-axis (left panel). Values shown in the right panel were obtained from three independent experiments. t-test; * p < 0.05 compared to EV. (E) Representative acquisition of migration assays performed on MPPED2 or EV transfected TPC-1 and FRO cells (magnification 40×) (left panel). Values obtained from three (TPC-1) or four (FRO) independent experiments were reported as mean ± SEM and compared to the EV, set equal to 1 (right panel). t-test; * p < 0.05. (F) qRT-PCR analysis to evaluate the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 after MPPED2 transfection. Data obtained from three (TPC-1) or five (FRO) independent experiments were reported as relative expression ± SEM and were compared to the EV, set equal to 1. t-test; p = ns.

In addition, to evaluate the effects of MPPED2 on cancer progression, we performed transwell assays on MPPED2-expressing TPC-1 and FRO cells treated with mytomicin C. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 4E, we found a significant reduction of migrating cells both in MPPED2-TPC-1 and FRO cells, thus demonstrating a role of MPPED2 in inhibiting also cellular migration.

Noteworthy, through qRT-PCR, we observed no modulation of the RP5-1024C24.1 expression mediated by MPPED2, thus indicating that RP5-1024C24.1 is able to modulate MPPED2, but not vice versa (Figure 4F).

3. Discussion

The aim of our study was to investigate the role of lncRNAs in thyroid carcinogenesis by evaluating the expression profile of 12 PTC compared to four normal thyroid samples through a human lncRNA microarray approach. This analysis identified a relevant number of lncRNAs deregulated in PTC compared to normal thyroid tissues. The microarray results were confirmed by evaluating the expression of six up- and six down-regulated lncRNAs by qRT-PCR. Subsequently, we focused our attention on the RP5-1024C24.1 lncRNA, that was drastically down-regulated in all PTC samples analysed with respect to normal thyroid tissues. However, we are currently planning to examine in depth the role of other deregulated lncRNAs in thyroid carcinogenesis.

The next step of our investigation was to evaluate the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 in thyroid neoplastic samples of different malignant degrees. Interestingly, we observed that the expression levels of this lncRNA are decreased in both differentiated and undifferentiated thyroid carcinomas. Surprisingly, RP5-1024C24.1 reduction was also observed in benign FTA suggesting a key role of RP5-1024C24.1 down-regulation even in the early phases of thyroid cell neoplastic transformation.

Bioinformatic analyses (Materials and Methods section) revealed that RP5-1024C24.1 is located on the genome in an antisense position with respect to MPPED2. This gene codes for an enzyme belonging to the III class-family of phosphoesterase in mammals and is highly expressed in foetal brain. Recent studies have demonstrated that the expression of MPPED2 is drastically down-regulated in several malignant neoplasias originating from different tissues. Moreover, its restoration in cancer cell lines induces apoptosis and negatively modulates cell proliferation [27,28,29], thus proposing MPPED2 as a potential candidate tumour suppressor gene. Consequently, we evaluated the expression of the MPPED2 gene by qRT-PCR in the same set of thyroid neoplastic samples analysed for RP5-1024C24.1 expression: a reduced expression of this gene was observed in the different histotypes analysed. In addition, we observed a significant positive correlation between MPPED2 and RP5-1024C24.1 expression in the thyroid neoplastic samples analysed (p = 0.0444).

Noteworthy, immunohistochemical analysis performed on a large number of paraffin-embedded thyroid neoplastic tissues and their adjacent normal thyroid tissue confirmed the results obtained by qRT-PCR. In fact, we observed that MPPED2 levels were moderately decreased in FTA, and strongly decreased in FTC, PTC and PDC. Surprisingly, while the expression of MPPED2 was markedly reduced in 86% of PDC samples, in the ATC set only 53% of cases showed reduced expression of MPPED2. Additionally, by analysing each thyroid carcinoma histotype, we found significant differences of MPPED2 expression between neoplastic and normal tissue samples.

Functional studies were performed to define the role of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 down-regulation in thyroid carcinogenesis. Accordingly, we stably restored the expression of RP5-1024C24.1 in two thyroid carcinoma cell lines by transfecting them with a vector expressing the lncRNA sequence. We observed that RP5-1024C24.1 was able to reduce the cell proliferation and migration rate, thus indicating that the deregulation of this lncRNA might play a causative role in the modulation of the biological processes leading to thyroid carcinoma development.

Interestingly, in order to clarify the molecular mechanisms by which RP5-1024C24.1 is able to affect cell growth and migration in thyroid carcinoma cells, we found that the restoration of RP5-1024C24.1 is able to increase PTEN protein levels and to reduce Akt-Ser473 phosphorylation, thus suggesting that the modulation of this pathway could account for the effects of RP5-1024C24.1 on cell proliferation and migration [30,31,32,33,34].

However, since we demonstrated that also MPPED2 restoration is able to inhibit cell proliferation and migration in TPC-1 and FRO cell lines, we suggest that the functional effects of RP5-1024C24.1 could also be due to the up-regulation of the MPPED2 gene expression. Interestingly, no RP5-1024C24.1 modulation was observed in MPPED2-expressing cells indicating that the regulation is unidirectional.

As far as the mechanisms by which RP5-1024C24.1 is able to positively regulate MPPED2 are concerned, they still need to be clarified, although several pieces of evidence suggest that lncRNAs are able to modulate the expression of their associated genes through epigenetic regulations [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Consistently, Shen and colleagues have recently indicated miR-448 as a negative regulator of MPPED2 [27]. Therefore, we have analysed the expression of this miRNA in our thyroid carcinoma cell systems stably expressing RP5-1024C24.1. Interestingly, our preliminary data have shown a reduction of the miR-448 expression following the restoration of the lncRNA expression (data not shown), thus suggesting that one of the mechanisms by which RP5-1024C24.1 might positively regulate MPPED2 expression could be through the negative modulation of the miR-448.

In conclusion, the results presented here indicate that the down-regulated RP5-1024C24.1 and its associated-gene MPPED2, could represent novel tumour suppressor genes with a considerable role in thyroid cell neoplastic transformation and progression.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Human Thyroid Samples

The whole set of human thyroid carcinoma specimens used was provided by the Service d’Anatomie et Cytologie Pathologiques, Centre de Biologie Sud, Groupement Hospitalier Lyon Sud, Pierre Bénite, France. The histotype and TNM characteristics of PTC samples used for lncRNA microarray analysis are reported in Table S1. The activity of biological samples conservation was declared under the number DC-2011-1437 to the ministry of Research, to the committee of people’s protection of south-east IV and to the Health Regional Agency. The activity of biological material cession was agreed upon by the ministry of Health under the number AC-2013-1867.

4.2. Long Non-Coding RNA Microarray Analysis

Total RNA extracted from 12 PTC samples and four normal thyroid tissues was hybridized to the Human LncRNA Microarray Version 3.0 of the Arraystar company (Rockville, MD, USA). This system is based on probes able to recognize specific exons or splice junction of each lncRNA. The expression analysis was performed by comparing the average of the expression levels observed in 12 PTC samples with the average of the expression levels observed in four normal thyroid tissues. Bioinformatic analyses were performed by the Arraystar company based on the following databases: Refseq, UCSC, GENCODE, RNAdb, NRED, UCR, lincRNA catalogs [35,36] (https://www.arraystar.com/human-lncrna-expression-microarray-v4-0/) (Table S2).

4.3. Cell Lines and Transfection

TPC-1 and FRO cell lines were grown in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (Euroclone, Milan, Italy), 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and were maintained at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere.

The authenticity of cell lines has been confirmed through short tandem repeat (STR) profiling.

TPC-1 cells were transfected using Fugene HD reagent (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) while FRO cells were transfected using the Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For stably-expressing cell lines, TPC-1 and FRO were selected by using 1000 µg/mL and 1200 µg/mL of G418 (Life Technologies), respectively.

For cell count number assays, 2 × 104 TPC-1 and FRO stable clones were seeded in a six well plate in duplicate and counted after 24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h using a Burker chamber.

4.4. Plasmids

The RP5-1024C24.1 expression vector was obtained by cloning the lncRNA sequence in the pCMV6-AC-GFP vector (Origene Technologies, Rockville, MD, USA) using the HindIII and XhoI restriction sites. The pCMV6-MPPED2-DDK-myc expression vector encoding human MPPED2 (NM_00145399.1) fused to the myc/DDK epitope in the C-terminal region was purchased from Origene Technologies (RC227201).

4.5. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines and tissues by using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 1 μg of total RNA was used to obtain a double strand cDNA with the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). qRT-PCR was carried out in a 96 well plate with the CFX 96 thermocycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using 20 ng of each cDNA and SYBR Green (Bio-Rad). G6PD was used as reference gene for qRT-PCR performed on thyroid neoplasias, while β-Actin was used for thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Primers sequences are listed in Table S3.

Relative expression values were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt formula as previously described [37].

As far as qRT-PCR analyses are concerned, we used four normal thyroid tissue samples for the validation of the microarray results (lncRNA and associated gene expression in PTC). However, we used only three out of four normal thyroid tissues for further analyses (expression analyses in additional set of thyroid neoplasms and cell lines) since the RNA of one out of the four normal samples ran out.

4.6. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Total protein extracts were obtained using the lysis buffer (120 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 2% Nonidet P40) completed with a mix of proteases and phosphatases inhibitors. 80 μg of extracted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Membranes were blocked with BSA or 5% not-fat milk and then incubated with the following antibodies: anti-myc tag (ab9132, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-MPPED2 (H00000744-D01P, Abnova, Taipei City, Taiwan), anti-PTEN (ab32199, Abcam), anti-pospho-Akt (Ser473) (#4051, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-Akt (#92725, Cell Signaling). To normalize the amount of protein loaded, the membranes were incubated with anti-GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-β-Actin protein (Sigma-Aldrich). Filters were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3000) for 1 h at room temperature and the signals were detected by western blotting detection system (ECL).

4.7. Cell Migration Assays

Transwell motility assays were performed as previously described [38]. Briefly, cells were first treated with mytomicin C (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 0.01 mg/mL for 3 h. Then, 3 × 104 TPC-1 and FRO cells were seeded both in the transwell for migration and in a 96 well plate in triplicate or quadruplicate to normalize the number of cells used for each cell line. The cell titer and the crystal violet de-stained with PBS-0.1% SDS solution were read at 490 nm and 590 nm, respectively, in a microplate reader (LX 800, Universal Microplate Reader, BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Results were obtained by normalizing the crystal violet values to cell titer ones.

4.8. Immunohistochemical Analysis

In the IHC analysis, the following set of thyroid neoplasias and the corresponding adjacent normal thyroid tissue was included: FTA, n = 19; PTC, n = 147 (classical variant, n = 74; follicular variant, n = 73); FTC, n = 30; PDC, n = 37; ATC, n = 15.

The original Hematoxylin–Eosin–Saffron (HES) stained slides were reviewed. For the PTC cases, the most representative areas of normal and tumoural tissues were circled. Up to two formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks were selected to be sampled in a tissue microarray (TMA). One 0.6 mm normal tissue core and three 0.6 mm tumoural tissue cores were collected and aligned in two TMA blocks, using the tissue arrayer Minicore® 3 (Alphelys, Plaisir, France). The blocks were sectioned at 3 µm. An HES stain of the TMAs was performed to assess the representativeness of the cores. The ATC and FTA cases were processed as whole slides following the same immunohistochemical protocol as the TMAs.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed on a Benchmark Ultra automated staining platform (Ventana, Tucson, AZ, USA) using a rabbit polyclonal MPPED2 antibody (Abnova), with a 1:60 dilution and an UltraView DAB detection kit (Ventana). A hematoxylin counterstain followed.

The level of staining was evaluated in the normal and tumoural tissues following a qualitative scoring method. The expected staining pattern was “cytoplasmic granular”, conformingly to what was observed in the positive controls (normal duodenal epithelium). The absence of staining was scored 0, a mild non-granular staining was scored 1, a granular moderate staining was scored 2 and a granular intense staining was scored 3.

The difference of MPPED2 expression between non tumoural and tumoural tissue, in the whole cohort and in each histologic subtype, was analysed using the paired sample t-test.

4.9. Flow Cytometry Analysis

For cell cycle analyses, cells were processed as previously described [39]. Briefly, cells were trypsinized and, after washing in PBS, fixed in 70% ethanol. After a centrifugation at 1200 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, cells were treated with 50 µg/mL propidium iodide and 25 µg/mL ribonuclease A in PBS for 20 min at RT safe of light. For each measurement 10,000 events were analysed using a FACScanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) and then cell cycle data were analysed with the ModFit LT 2.0 software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA) in a semiautomatic analysis procedure. The ModFit algorithm was finally used to analyse the files obtained, calculating the percentage of cells in each cell cycle phase.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software was used for statistical analyses. t-test and Anova tests were used to evaluate the statistical significance of the obtained data, while gene expression correlation was evaluated through non-parametric Spearman’s Rank correlation coefficient. When Anova test was significant (p < 0.05), we determined the differences between groups using Bonferroni post-test. In all the experiments, the significance was assessed for p < 0.05. Data are reported as mean values ± standard error of mean (SEM).

5. Conclusions

In this study, we identified several lncRNAs whose expression is deregulated in PTC compared to normal thyroid samples and, among them, we focused on RP5-1024C24.1 and on its associated-antisense gene MPPED2 for further investigation. We report that both genes are down-regulated in thyroid neoplasias. Moreover, the restoration of their expression in thyroid cancer cell lines reduces cell proliferation and migration, thus suggesting a tumour suppressor role for RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 in the development of thyroid neoplasias.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants provided by: “Progetto di Interesse Strategico Invecchiamento (PNR-CNR Aging Program) PNR-CNR 2012–2014” and “CNR Flagship Projects (Epigenomics-EPIGEN)”. Romina Sepe was granted with a fellowship provided by “Fondazione Adriano-Buzzati Traverso”, 2016. We thank Giuseppina Ippolito and Giulia Speranza (IEOS-CNR) for administrative support and Salvatore Sequino (DMMBM, University of Naples “Federico II”) for technical support.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/10/5/146/s1, Figure S1: LncRNA expression analysis in additional PTC samples. qRT-PCR analysis to evaluate the expression of RP11-230G5.2, DLEU2 and SLC26A4-AS1 in additional PTC samples. Results are reported as relative expression ± SEM compared to the mean of three normal thyroid samples set equal to 1; Figure S2: Expression analysis of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 in thyroid carcinoma cell lines. qRT-PCR performed on papillary (TPC-1, B-CPAP), follicular (WRO), anaplastic (FB-1 and FRO) thyroid carcinoma cell lines and three normal thyroid tissue samples (NT1, NT2, NT3). Data are reported as 2−ΔCt values ± SD; Figure S3: Analysis of RP5-1024C24.1 and MPPED2 expression in TPC-1- and FRO-transfected cells. qRT-PCR analysis performed on TPC-1 and FRO cell lines stably expressing RP5-1024C24.1 (A), MPPED2 (B) or carrying the corresponding empty vector (EV), and three normal thyroid tissue samples (NT1, NT2, NT3). Data are reported as 2−ΔCt values ± SEM; Table S1: PTC samples used for lncRNA microarray; Table S2: Whole list of lncRNAs deregulated in PTC vs. NT; Table S3: List of primer sequences used for qRT-PCR analyses.

Author Contributions

R.S. contributed to the scientific planning and experimental execution, the interpretation and analyses of the data and the manuscript drafting; S.P. contributed to the experimental procedure and analyses of the data; P.S. and M.D.-P. contributed to samples collection and IHC analyses; D.D., A.F. and R.C.C.P. contributed to cloning procedure and migration experiments; M.R. and L.D.V. contributed to cell cycle analyses; P.P. and A.F. contributed to study design, manuscript writing and final approval. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Materials

All published data and material are available upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Parkin D.M., Bray F., Ferlay J., Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedinger C., Williams E.D., Sobin L.H. The who histological classification of thyroid tumors: A commentary on the second edition. Cancer. 1989;63:908–911. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890301)63:5<908::AID-CNCR2820630520>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fusco A., Grieco M., Santoro M., Berlingieri M.T., Pilotti S., Pierotti M.A., Della Porta G., Vecchio G. A new oncogene in human thyroid papillary carcinomas and their lymph-nodal metastases. Nature. 1987;328:170–172. doi: 10.1038/328170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fusco A., Santoro M. 20 years of RET/PTC in thyroid cancer: Clinico-pathological correlations. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 2007;51:731–735. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27302007000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grieco M., Santoro M., Berlingieri M.T., Melillo R.M., Donghi R., Bongarzone I., Pierotti M.A., Della Porta G., Fusco A., Vecchio G. PTC is a novel rearranged form of the ret proto-oncogene and is frequently detected in vivo in human thyroid papillary carcinomas. Cell. 1990;60:557–563. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung C.K., Little M.P., Lubin J.H., Brenner A.V., Wells S.A., Jr., Sigurdson A.J., Nikiforov Y.E. The increase in thyroid cancer incidence during the last four decades is accompanied by a high frequency of BRAF mutations and a sharp increase in RAS mutations. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99:E276–E285. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ming J., Liu Z., Zeng W., Maimaiti Y., Guo Y., Nie X., Chen C., Zhao X., Shi L., Liu C., et al. Association between BRAF and RAS mutations, and ret rearrangements and the clinical features of papillary thyroid cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015;8:15155–15162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Penna G.C., Vaisman F., Vaisman M., Sobrinho-Simoes M., Soares P. Molecular markers involved in tumorigenesis of thyroid carcinoma: Focus on aggressive histotypes. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2017;150:194–207. doi: 10.1159/000456576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melillo R.M., Castellone M.D., Guarino V., De Falco V., Cirafici A.M., Salvatore G., Caiazzo F., Basolo F., Giannini R., Kruhoffer M., et al. The RET/PTC-RAS-BRAF linear signaling cascade mediates the motile and mitogenic phenotype of thyroid cancer cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2005;115:1068–1081. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Pallante P., Battista S., Pierantoni G.M., Fusco A. Deregulation of microrna expression in thyroid neoplasias. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013;10:88–101. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derrien T., Johnson R., Bussotti G., Tanzer A., Djebali S., Tilgner H., Guernec G., Martin D., Merkel A., Knowles D.G., et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: Analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res. 2012;22:1775–1789. doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttman M., Amit I., Garber M., French C., Lin M.F., Feldser D., Huarte M., Zuk O., Carey B.W., Cassady J.P., et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gutschner T., Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: A long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9:703–719. doi: 10.4161/rna.20481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta R.A., Shah N., Wang K.C., Kim J., Horlings H.M., Wong D.J., Tsai M.C., Hung T., Argani P., Rinn J.L., et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1071–1076. doi: 10.1038/nature08975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai M.C., Manor O., Wan Y., Mosammaparast N., Wang J.K., Lan F., Shi Y., Segal E., Chang H.Y. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wapinski O., Chang H.Y. Long noncoding RNAs and human disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponting C.P., Oliver P.L., Reik W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2009;136:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang C.G., Yin D.D., Sun S.Y., Han L. The use of lncRNA analysis for stratification management of prognostic risk in patients with NSCLC. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;21:115–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang J., Lin Z., Gao Y., Yao T. Downregulation of long noncoding RNA MEG3 is associated with poor prognosis and promoter hypermethylation in cervical cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;36:5. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0472-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen M., Liu B., Xiao J., Yang Y., Zhang Y. A novel seven-long non-coding RNA signature predicts survival in early stage lung adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:14876–14886. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T., Huang Y., Chen J., Chi H., Yu Z., Wang J., Chen C. Attenuated ability of bace1 to cleave the amyloid precursor protein via silencing long noncoding RNA bace1as expression. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014;10:1275–1281. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotake Y., Nakagawa T., Kitagawa K., Suzuki S., Liu N., Kitagawa M., Xiong Y. Long non-coding RNA ANRIL is required for the PRC2 recruitment to and silencing of p15INK4B tumor suppressor gene. Oncogene. 2011;30:1956–1962. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yap K.L., Li S., Munoz-Cabello A.M., Raguz S., Zeng L., Mujtaba S., Gil J., Walsh M.J., Zhou M.M. Molecular interplay of the noncoding RNA ANRIL and methylated histone H3 lysine 27 by polycomb CBX7 in transcriptional silencing of INK4a. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:662–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckedorff F.C., Ayupe A.C., Crocci-Souza R., Amaral M.S., Nakaya H.I., Soltys D.T., Menck C.F., Reis E.M., Verjovski-Almeida S. The intronic long noncoding RNA ANRASSF1 recruits PRC2 to the RASSF1A promoter, reducing the expression of RASSF1A and increasing cell proliferation. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berghoff E.G., Clark M.F., Chen S., Cajigas I., Leib D.E., Kohtz J.D. Evf2 (Dlx6as) lncRNA regulates ultraconserved enhancer methylation and the differential transcriptional control of adjacent genes. Development. 2013;140:4407–4416. doi: 10.1242/dev.099390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Da Rocha S.T., Boeva V., Escamilla-Del-Arenal M., Ancelin K., Granier C., Matias N.R., Sanulli S., Chow J., Schulz E., Picard C., et al. Jarid2 is implicated in the initial XIST-induced targeting of PRC2 to the inactive X chromosome. Mol. Cell. 2014;53:301–316. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen L., Liu L., Ge L., Xie L., Liu S., Sang L., Zhan T., Li H. miR-448 downregulates MPPED2 to promote cancer proliferation and inhibit apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 2016;12:2747–2752. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R., Shen C., Zhao L., Wang J., McCrae M., Chen X., Lu F. Dysregulation of host cellular genes targeted by human papillomavirus (HPV) integration contributes to HPV-related cervical carcinogenesis. Int. J. Cancer. 2016;138:1163–1174. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liguori L., Andolfo I., de Antonellis P., Aglio V., di Dato V., Marino N., Orlotti N.I., De Martino D., Capasso M., Petrosino G., et al. The metallophosphodiesterase Mpped2 impairs tumorigenesis in neuroblastoma. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:569–581. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.3.19063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura M., Gu J., Matsumoto K., Aota S., Parsons R., Yamada K.M. Inhibition of cell migration, spreading, and focal adhesions by tumor suppressor PTEN. Science. 1998;280:1614–1617. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song M.S., Salmena L., Pandolfi P.P. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sun H., Lesche R., Li D.M., Liliental J., Zhang H., Gao J., Gavrilova N., Mueller B., Liu X., Wu H. PTEN modulates cell cycle progression and cell survival by regulating phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5,-trisphosphate and AKT/protein kinase B signaling pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6199–6204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stambolic V., Suzuki A., de la Pompa J.L., Brothers G.M., Mirtsos C., Sasaki T., Ruland J., Penninger J.M., Siderovski D.P., Mak T.W. Negative regulation of PKB/AKT-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu N., Lao Y., Zhang Y., Gillespie D.A. AKT: A double-edged sword in cell proliferation and genome stability. J. Oncol. 2012;2012:951724. doi: 10.1155/2012/951724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cabili M.N., Trapnell C., Goff L., Koziol M., Tazon-Vega B., Regev A., Rinn J.L. Integrative annotation of human large intergenic noncoding RNAs reveals global properties and specific subclasses. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1915–1927. doi: 10.1101/gad.17446611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalil A.M., Guttman M., Huarte M., Garber M., Raj A., Rivea Morales D., Thomas K., Presser A., Bernstein B.E., van Oudenaarden A., et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:11667–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904715106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepe R., Formisano U., Federico A., Forzati F., Bastos A.U., D'Angelo D., Cacciola N.A., Fusco A., Pallante P. CBX7 and hmga1b proteins act in opposite way on the regulation of the SPP1 gene expression. Oncotarget. 2015;6:2680–2692. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puca F., Colamaio M., Federico A., Gemei M., Tosti N., Bastos A.U., Del Vecchio L., Pece S., Battista S., Fusco A. Hmga1 silencing restores normal stem cell characteristics in colon cancer stem cells by increasing p53 levels. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3234–3245. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All published data and material are available upon request to the corresponding authors.