Abstract

By unconscious or covert processing of pain we refer to nascent interactions that affect the eventual deliverance of pain awareness. Thus, internal processes (viz., repeated nociceptive events, inflammatory kindling, re-organization of brain networks, genetic) or external processes (viz., environment, socioeconomic levels, modulation of epigenetic status) contribute to enhancing or inhibiting the presentation of pain awareness. Here we put forward the notion that for many patients, ongoing sub-conscious changes in brain function are significant players in the eventual manifestation of chronic pain. In this review, we provide clinical examples of nascent or what we term pre-pain processes and the neurobiological mechanisms of how these changes may contribute to pain, but also potential opportunities to define the process for early therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Subconscious, Awareness, Chronic pain, Cognition, Iceberg, Brain, Neural networks

1. Introduction

The emergence of chronic pain is usually not abrupt in onset. Subtle ongoing conscious or subconscious processes contribute to a brain state that defines the ‘chronic pain phenotype’, usually associated with a complex phenotype involving sensory, emotional, cognitive, endocrine and other processes. Conscious “inner qualitative, subjective states and processes of awareness” (Searle, 2000) is a complex neurobiological process (Delacour, 1997). Unconscious neural processing involves neural connections that may be unperceived by the individual (Zeman, 2001). Such processes may eventually have an effect on an individual’s awareness (Kihlstrom, 1987). Several systems have been considered to play a role in the latter including perceptual, evaluative and motivational components (Bargh and Morsella, 2008). Subliminal processes may contribute to overt behavior as they do in unconscious processes in the control of actions (Morsella and Poehlman, 2013).

In the context of experimental pain, elements of subconscious processing have been reported in healthy subjects. Examples include: (1) Experimental manipulation of subconsciousness can affect nociceptive processing (Lewis et al., 2015); (2) unconscious manipulation of the placebo or nocebo responses (Jensen et al., 2012a); (3) decreased pain perception modulated by unconscious emotional pictures (Pelaez et al., 2016); and (4) classical conditioning of pain without awareness of conditioning cues (Jensen et al., 2015). Unconscious perception – processing of sensory information that we are not aware of – has been evaluated in other systems including visual (Brogaard, 2011; Kiefer et al., 2011) and motor (Morsella and Poehlman, 2013). In addition, there is unconscious processing of negative emotions (Okubo and Ogawa, 2013). Taken together, such processes are reflective of “The Cognitive Unconscious” wherein “…. research on subliminal perception, implicit memory and hypnosis indicates that events can affect mental functions” even though they are not part of our conscious awareness (Kihlstrom, 1987).

1.1. The iceberg principle

Modulation of brain systems may result in changes in behavior. The transition from acute to chronic pain is one example of how brain systems may change to incorporate initial drivers of acute pain that may contribute to the complexities of brain changes that manifest in chronic pain. Clearly non-conscious processes may be ongoing. The so called ‘Iceberg Principle’ provides an example of conscious (above water) and non-conscious (underwater) contributions to the overall ongoing process that may change with time. The Iceberg Principle has been defined as: “Observation that in many (if not most) cases only a very small amount (the ‘tip’) of information is available or visible about a situation or phenomenon, whereas the ‘real’ information or bulk of data is either unavailable or hidden” (www.businessdictionary.com). The expression of pain may follow this principle in a number of ways (see Fig. 1). In this paper we refer to a number of terms that may require defining in the context of how they are applied here are shown in Box 1.

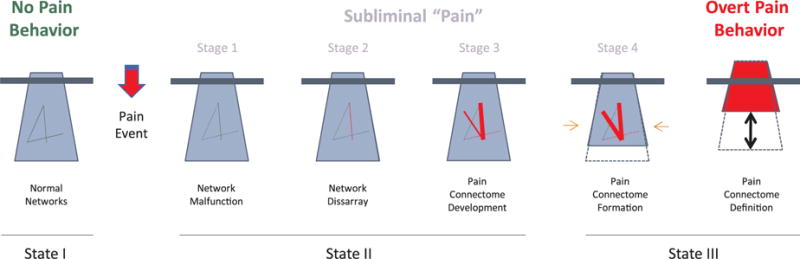

Fig. 1.

The Iceberg Principle and Chronic Pain (see Text).

State I: No Pain Behavior (Left). Under healthy conditions, the tip of the iceberg presents with an adaptive behavior based on underlying normal brain network interactions that may be dependent on environment, health status, genetic status, etc.

State II: Subliminal “Pain” (Middle): A pain event (viz., injury, a disease, a genetic condition, etc.) produces a transition fromm State I to State II. Multiple processes may be at play following a perturbation that may be endogenous (e.g., depression) or exogenous (e.g., trauma). These may be categorized as: (a) Network malfunction; (b) Network Disarray; (c) Pain Connectome Development; and (d) Pain Connectome Formation. Thus, latent processes are ongoing.

State III: Overt Pain Behavior (Right): A number of changes in brain systems including morphometric, chemical and functional metrics that lead to a brain state of chronic pain (Pain Connectome Definition). The behavior becomes overt (and usually progressively worse) at a particular time. An altered brain system evolves with new connections, changes in grey matter volume to produce a ‘lighter iceberg’ where now more is obvious above the waterline (i.e., overt behavior), while ongoing dysregulation may be ongoing. At this point, the brain may rekindle its original form with pain behavior resolving, or remain in the same status (i.e., pain behavior becoming stuck). State III may continue with no resolution or reverse partially (State IV) or completely through similar processes noted in State II. With symptomatic reversal, the brain state is not fully ‘cured’ (i.e., does not revert completely to State I), but remains sensitized to pain recrudescence (see Text). State IV, not shown here, is the process of reversal (see Fig. 2 and Text).

Box 1. Definitions of Terms.

Acute and Chronic Pain

Both acute and chronic pain are ill defined. While acute pain has been considered pain to be a pain that lasts for 3–6 months by some, a more appropriate definition is that associated with a defined etiology (e.g., injury, surgery and resolves with healing. The definition of chronic pain is more difficult and while defined by the IASP of pain that lasts for more than 3 months (Treede et al., 2015) (when healing apparently has resolved, there is an inherent issue of when it may begin (since the pain continues) and subclinical processes e.g., inflammatory may be present but not easily evaluated. Chronic pain may also occur in the absence of prior tissue injury.

Brain Pain Phenotype

The phenotypic expression of pain (“an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (https://www.iasp-pain.org/Taxonomy#Pain)).

Comorbid(ity) and Pain

Pain may co-exist with other disease states (“existing simultaneously with and usually independently of another medical condition” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/comorbid)).

Consciousness and Pain

Pain is an experience of a conscious brain.

Pain Relapse

A condition where there is reversal from a non-pain state to a pain state (i.e., pain has previously been present).

Pre- Pain

We use this term in the context of neural systems being primed or functionally or structurally changed in a temporal sense (i.e., on a continuum to a chronic pain state) or in a static sense where additional stressors (viz., pain, onset of or presence of comorbid state) may add to the tipping point of phenotypic/subjective expression.

Subconscious Processing and Pain

Pain-related information is present without awareness in otherwise awake/conscious individuals.

Subliminal Pain

We have used the definition of subliminal as “existing or functioning below the threshold of consciousness” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/subliminal).

In this review, we evaluate the nature of potential unconscious processing of an underlying subliminal “pre-pain” prior to its evolution to a chronic pain state, a process that may occur over a short, (hours to days) or long (weeks to months), time-span. While we are not clear as to the most appropriate definition, clearly pain includes conscious awareness. We have divided the review into the following sections: (1) In the first section, When Pain Pops Out to Conscious Awareness – Insights from Clinical Examples, we review clinical examples of chronic pain that seem to have an underlying ongoing silent process prior to a clinical presentation and vice versa; and (2) In the section of Neurobiological Mechanisms and Pre-Pain Unconsciousness we discuss process, including sensory and emotional priming, conscious and unconscious sensory flow, and neuroimaging data that support unconscious processes in chronic pain. We have provided some definitions of terms used in this paper in Table 1.

Table 1.

Putative brain regions involved in pain evolution and subliminal processing of pain.

| Brain Region | Putative Role | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cortical | ||

| Prefrontal cortex | A critical node within the default mode and frontoparietal network and thalamocortical connections corresponding to conscious information processing and restoration. Inactivation during sensory processing. | Laureys (2005), Laureys et al. (2002), Di Perri et al. (2014) |

| Precuneus | An important brain region involved in the default mode and frontoparietal network; involved in consciousness information processing. | Cavanna and Trimble (2006), Cavanna (2007), Cavanna (2007) |

| Anterior insula | Involved in increased responsivity to subliminally arousing stimuli as compared with consciously perceived stimulus. Involved in pain salience that may change with state. Initial state involvement relates to state of awareness (Examples include – ‘feeling pain’ in the absence of a painful stimulus, reporting minimal pain in the setting of major trauma, having an ‘analgesic’ response in the absence of an active treatment). | Borsook et al. (2013), Meneguzzo et al. (2014) |

| Anterior cingulate cortex | Involved in processing physiological subliminal stimuli and a key node in differential activation in response to subliminal as compared with consciously perceived stimuli. Involved in many functions that include affective state and perceived pain intensity. | Brooks et al. (2012), Meneguzzo et al. (2014), Fuchs et al. (2014) |

| Hippocampus | Involved in conscious and unconscious memories; involved in interactions with sensory cortices. | Behrendt (2013), Züst et al., (2015) |

| Involved in functional/structural changes in chronic pain. | ||

| Subcortical | ||

| Thalamus | Thalamocortical connections with anterior cingulate and frontal cortices; involved in restoration and maintenance of consciousness. Thalamic habenula nucleus: Frontal – brainstem connections; transition of ‘reward to misery’ |

Laureys et al. (2000), Batalla et al. (2017) |

| Amygdala | Involved in subliminal processing of emotional and neutral face-related stimuli. Involved in pain- related fear and structural and functional alterations observed across chronic pain syndromes. | Brooks et al. (2012), Icenhour et al. (2015) |

| Brainstem | Important (nonconscious) brainstem nodes involved in endogenous pain modulatory processes on dorsal horn nociception:

|

Fields and Heinricher (1985), Bouhassira et al. (1992), Youssef et al. (2016) |

2. When pain pops out to conscious awareness – insights from clinical examples

Damage to our peripheral or central nervous system may take place as a consequence of a particular event (e.g., trauma) that may result in acute pain that then disappears, or an ongoing low-level process (e.g., poison, endocrine abnormalities); in both scenarios, patients may present later with chronic pain. Other examples include delayed pain with aging, pain with depression, pain following early life trauma, etc. The underlying basis is an evolution of brain changes that reach a threshold to activate the “behavioral phenotype”. Here we discuss a few clinical examples of this process and evaluate the current theme of underlying brain processes that precede conscious awareness of pain. In this section, we explore observations that may support the ‘iceberg principle” through various clinical examples. These include the following themes – (1) delayed onset or offset of pain that may be present in development (neonatal/infant) or following damage central nervous system (e.g., in post stroke pain where pain may occur weeks to months after the insult) or delayed recovery from pain (e.g., in post herpetic neuralgia); (2) aspects of pain/nociception that relate to the unconscious state viz., nociceptive barrage occurring during surgery that may evolve in some to a chronic state; in a similar manner, pain recall for a procedure, represents a subliminal/subconscious process that can evolve to consciousness; (3) evolution of repetitive nociceptive drive to a chronic daily pain state (e.g., in migraine and sickle cell anemia); (4) comorbidity and emotional states and pain – i.e., the contributions of brain state (e.g., underlying anxiety, depression) in pain evolution where such conditions may either evolve with a pain phenotype (viz., previously no pain) or initiate or exacerbate pain consciousness; (5) effects of analgesic medications on pain chronification; included in this section is the notion that pain occurring in the setting of torture (i.e., emotional salience) may have a greater chance of evolution to chronicity; (5) Finally we embrace a theme from the addiction literature on pain relapse.

2.1. Delayed development of pain

Injuries to nerves in animal models produce pain in a relatively consistent manner, depending on the strain being tested. Chronic neuropathic pain following nerve damage in early childhood usually does not evolve in the majority of individuals and may perhaps reflect age-related resilience (Fitzgerald and McKelvey, 2016b). This is clear when examining the relationship between early child amputation and delayed (in years) phantom limb, that is, the occurrence of delayed phantom limb pain is more likely with increased age of deafferentation (Melzack et al., 1997). This observation has also been evaluated in animal models. Following nerve damage, no mechanical hyperalgesia is observed during early development, but emerges in adolescent P31 (21 days post-injury) rats. This type of study supports the idea that, during early development, an insult may induce changes that persist but only become behaviorally relevant (at least as assessed by testing for pain responsivity) later. Others have shown a parallel process where there seems to be a lack of chronic pain outcome in infants who sustain brachial plexus injuries during birth (Anand and Birch, 2002). Neural pathways that are damaged earlier result in similar pain behavior as older animals receiving the identical surgical nerve damage. The data show that while an interim protective process (lymphocytes) may be in place, changes are induced that remains subclinical until later in life. The data support the notion of development or presence of altered neural systems that manifest later “emerge clinically as ‘unexplained’ pain” later in life (Fitzgerald and McKelvey, 2016a; Vega-Avelaira et al., 2012) because it is suppressed (McKelvey et al., 2015).

2.2. Recall of pain and anesthesia awareness

Pain memory/recall has been reported by several investigators (Hunter et al., 1979; Noel et al., 2012) and some note that “recall for acute pain is more accurate than for chronic pain” (Erskine et al., 1990). More importantly, recall or memory of events that may have occurred and not reached conscious awareness but may make individuals more susceptible to pain later. We provide two clinical examples – anesthesia awareness and torture; these clinical examples may have slightly different processes in ‘hiding pain’ with delayed awareness. In both cases, alterations in brain systems precipitated by an earlier event may lead to delayed onset or recall of prior events.

While rare, patients undergoing surgery under anesthesia, may recall some events during surgery (Orser et al., 2008). Less common within this group is recall of pain that may include severe surgical pain at the incision site; pain recall may take place immediately after surgery following anesthesia reversal or recovery, or it may be delayed for hours or days (Sandin et al., 2000). For example, in two patients, post-traumatic changes existed for years “including pain symptoms that resembled, in quality and location, the pain experienced during surgery” (Salomons et al., 2004). Thus, brain systems recall a painful event long after the anesthetic event suggesting either post operative drugs limit the processing and recall of being aware of this or, and perhaps more germane to the thesis being put forward here, some individuals may have psychological adverse responses akin to PTSD (nightmares, anxiety and flashbacks) or depression (Samuelsson et al., 2007). “Symptoms involve re-experiencing the event awake or in dreams, sleep disturbances, depression, avoidance of stimuli associated with the event” (Schwender et al., 1995). From the point of view of emergence of pain, this concept fits well into the new thinking that chronic pain reflects alterations in emotional systems (Borsook et al., 2016a; Hashmi et al., 2013), and the insights garnered from these surgical related changes under incomplete anesthesia may parallel changes in pain chronification.

2.3. Repetitive, intermittent, acute pain that emerges into chronic pain

Classic clinical examples include sickle cell disease (SCD) (Niscola et al., 2009) and episodic migraine, where repeated episodic crises in SCD may emerge into a chronic pain state (Hollins et al., 2012) and the progression of migraine frequency, from episodic migraine into chronic migraine (Bigal and Lipton, 2008a; May and Schulte, 2016). In both cases, summation of repeated attacks affecting or involving afferent sensory systems may induce brain changes leading to a cascade that presents with a chronic pain condition. The example of migraine is discussed further in the section Subliminal “Pain” under Section 3.2. below.

2.4. Delayed chronic pain evolution and chronic pain recrudescence

Two clinical examples of delay in pain evolution include the following neuropathic conditions: Thalamic Stroke and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Both invoke central brain plasticity and have a clinical spectrum of either delay or increased complexity of the behavioral phenotype: (a) Thalamic stroke: Thalamic stroke may interfere with spino-thalamic-cortical pathways to produce a severe, contralateral pain (Henry et al., 2008). Temporal profiles on post-stroke pain onset and offset have been noted in prior reviews (Schott, 2001). Early psychophysical changes may predict later onset of Central Post Stroke Pain (CPSP) (Klit et al., 2014). (b) CRPS: Although not common, CRPS onset may be gradual or months after injury (Goris et al., 2007) or even spontaneous onset in 3–11% of cases (de Rooij et al., 2010). In addition, the various manifestation of CRPS (spreading pain/allodynia, hemi-inattention, abnormal posture/movements (dystonia), vasomotor disturbances) may take place over time (delay) with associated increased pain severity (van Rijn et al., 2007). Consistent with the theme of subconscious processing, these two examples implicate a tipping point leading to delayed expression of chronic pain. The latter may be enhanced or diminished by environmental, health, physiological or social interactions.

2.5. Pain onset related to evolution and devolution of comorbidity

While comorbidities of Depression and/or Anxiety and pain per se are well documented (Asmundson and Katz, 2009; Fishbain et al., 1997), the ‘de novo rise of pain’ in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) or the diminution of pain with diminished Anxiety are examples of aberrant brain circuits that may be present. Moreover, reports of generalized pain occurring in patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) are common (Greden, 2003; Husain et al., 2007; Trivedi, 2004), and depression is potentially one of the best examples of the notion that ongoing undercurrent reordering of neural networks may produce a chronic pain phenotype. While MDD is defined as having symptoms for at least two weeks (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition Text Revision (DSM-V)), the correlation of pain onset has not been fully evaluated. Some reports indicate that physical pains are found in > 50% of depressed patients (Pelissolo, 2009). In other words, depression may induce changes in the brain that tips the behavior into a pain phenotype, where this had not been present before nor any history of prior pain (Husain et al., 2007). Anxiety has also been found to be high in people with pain conditions and, despite the challenges of determining whether anxiety is pre-cursor to or consequence of living with chronic pain, people with high trait-anxiety are hypersensitive to stimuli and have increased psychological reactivity (e.g., restlessness, resistance to sedation) suggesting that anxiety may cause increased pain (Wassermann et al., 2001). Anxiety levels (severity) may change over time, producing more or less sensitivity to the presence or absence of pain (de Heer et al., 2014) and affected through multiple brain regions including the septum (Ang et al., 2017). The neurobiological basis for how psychological states such as depression and anxiety may exacerbate pain has been reviewed elsewhere (Bair et al., 2013; Borsook and Elman, 2018; Kageyama, 1973). The contribution of these states of decreasing the threshold for activation of pain awareness have not been explored. However, associated symptoms such as catastrophizing (Coronado et al., 2015; Quartana et al., 2009) or fear of pain (Simons et al., 2012, 2017) may predict later onset of pain. Some have argued that anxiety or chronic stress may exacerbate pain (Li et al., 2017) through alteration in specific nuclei (e.g., amygdala) via a process that induced neuronal sensitization due to decreased inhibition (Jiang et al., 2014). The link between depression and physical symptoms including pain has been ascribed to alteration in neurotransmitters involved in descending modulation. Indeed, alteration in descending modulation may be a principle mechanism that provides a set point for the conscious awareness of pain (see Section 3.1 below).

2.6. Opioids and induction of pain syndromes

Independent of opioid addiction (as a comorbid state), chronic use of opioids may induce increased sensitivity to pain. There are a number of examples but three illustrate the notion: (a) methadone addicts who have given up their addiction experience increased pain sensitivity to experimental pain years after halting their opioid use (Ren et al., 2009); (b) migraine patients who take opioids have an increased risk of disease chronification (Bigal and Lipton, 2008b); (c) chronic pain patients taking opioids may have so called opioid induced hyperalgesia (Lee et al., 2011), which probably relates to a process of pain ‘enhancement’ (hyperalgesia). Ongoing hyperalgesia may be a pre-determinant of more complex changes that lead to pain chronification (Woolf, 2011). Evidence for this includes that preoperative heat hyperalgesia predicts increased use of postoperative analgesics (Werner et al., 2010); potential alteration in descending modulatory systems (Miranda et al., 2015; Ossipov et al., 2014) are reported to be present in chronic pain patients (Jensen et al., 2012b; Yu et al., 2014); and intraoperative use of opioids may increase postoperative pain due to acute opioid tolerance or opioid induced hyperalgesia (Kim et al., 2014). Thus, from a number of perspectives, the addition of an opioid may produce changes in brain systems acutely (Upadhyay et al., 2012) or chronically (Upadhyay et al., 2010) that may then affect those being affected by the pain state.

2.7. Altered pain perception by emotional influences

Much has been written about emotional processing in pain. A few papers have addressed this concept in terms of how unconscious processing may either enhance or inhibit (see (Pelaez et al., 2016) pain. As such, unconscious emotional processing of interactive positive or negative events, feelings, sights, may produce changes that enhance the behavioral manifestation of pain. Here we differentiate deficits in emotional processing that may be present in patients (see (Kamping et al., 2013). Thus, unconscious process may induce a greater analgesic state when ‘rewarding’ and a greater pain state when ‘aversive’. In support of the latter, patients with migraine seem to have enhanced responsivity to aversive pictures (Wilcox et al., 2016). Taken together, interactions with our environment result in a barrage of sensory and emotional information that may contribute to unconscious processing that can drive sensitized systems (i.e., patients who have pain) or those where an evolving emotional status may be cross-sensitized to such stimuli.

2.8. Torture and traumas

Traumas involving simultaneous physical and psychological events (e.g., sexual abuse, rape and torture) with associated negative emotions (Walter et al., 2010) may produce exacerbated effects as a result of parallel processes (i.e., pain and emotional processes). As a result, the interactions may enhance the evolution of pain chronicity. Indeed, data supports the notion that chronic pain is ongoing and persists at nearly the same level as at the time of the initiating event (Olsen et al., 2006), and survivors have higher lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders (Van Ommeren et al., 2001). Psychological or physical torture may inflict ‘pain,’ but memories of pain may also be blunted as a result of impaired memory formation due to stress (Defrin et al., 2017). There seems to be a powerful interaction between pain and emotional processing: on the one hand, the level of pain predicts psychological sequelae (de C Williams and van der Merwe, 2013), while the type of psychological stress, rather than the trauma per se, has a significant effect on pain modulation and perception (Defrin et al., 2014, 2017). “Torture appears to induce generalized dysfunctional pain modulation that may underlie the intense chronic pain experienced by torture survivors decades after torture”. Pain repression may also be present, since painful flashbacks have been reported in the literature for a number of post-traumatic events (Loncar et al., 2010; Whalley et al., 2007) suggesting repression of pain memories, but that a pain ‘engram’ exists. Taken together, the notion of coincidental activation of both physical and negatively emotional events, may contribute to chronic dysfunction in the brain, including specific regions (viz., amygdala and hippocampus (Marin et al., 2016).

2.9. Pain relapse

Just as with pain onset and the cumulative changes that occur that eventually determine the behavioral syndrome, pain offset may produce a distinct subliminal state (Becerra and Borsook, 2008; Xie et al., 2014). It is germane here that the opponent-process theory (Solomon and Corbit, 1973, 1974) addresses simultaneous painful and rewarding experiences in the form of powerful neural mechanisms engaged in the maintenance of hedonic homeostasis essential for stabilization of emotional and motivational states. Accordingly, the hedonic tone is derived not only from the aversive pain experience but also from a valuationally opposite low and sluggish euphoric component that dampens the affective and motivational characteristics of the initial painful input (Elman and Borsook, 2016). The former, overshadowed by pain, usually becomes noticeable with the conclusion of the proponent painful condition. However, in some people, the opponent may later grow to define the intensity and valence of the overall affect and to yield algophilia, that is to say, a sense of pleasure derived from the experience of pain (Corsini, 2002). In this regard, termination of conditioned cue-induced effects (related to pain sensations, its emotions, interoceptions and behaviors) can evoke opponent subliminal symptomatology caused by the backward conditioning (i.e., linked to the conclusion of the unconditioned stimulus) and evidenced in pleasurable feeling, joy, reward and vigor leading to perpetuation of pain via positive reinforcement mechanisms (Borsook et al., 2016a).

The symptomatic reappearance may also be viewed as a pre-sensitized state allowing for recrudescence of the same pain previously experienced based on minor re-injury changes in emotional states or stress levels. Specifically, recurrent pain episodes disrupt the regulatory inhibitory GABA-ergic output in subcortical limbic structures such as basolateral amygdala (BLA) leading to hyperactivity (including diminished after hyperpolarization; (Faber et al., 2008)) of the principal glutamatergic excitatory outputs (Neugebauer, 2015), underlying anxiety, associative learning, pain conditioning and outpouring of the stress hormones. Such impairments in the BLA microcircuitry and in its projections to the respective structures involved in cognition and in motivational drives, namely the medial prefrontal cortex and ventral and dorsal striatum, also results in poor inhibitory control and impulsivity in conjunction with limited behavioral repertoire in the form of habit-based, rather than value-based, decision making processes and behavioral choices fixated on pain-related content including irresistible urges to seek and consume analgesic drugs and catastrophizing (Elman et al., 2011). Fig. 2 represents a potential process in relapse in chronic pain.

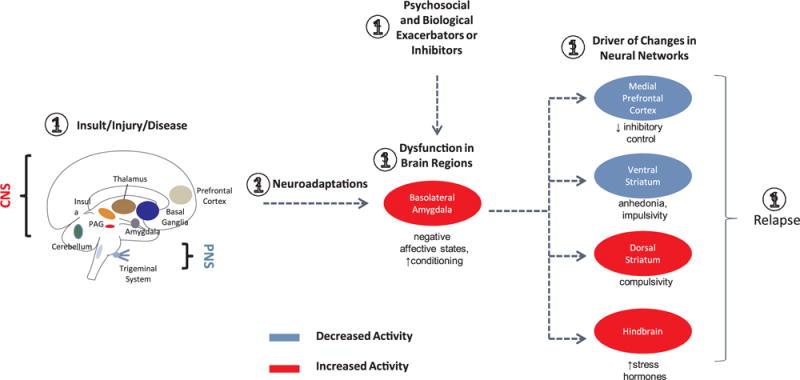

Fig. 2.

A putative model for pain relapse based on similar neurobiological mechanisms involved in pain and in addiction (see text).

1: Insult/Injury/Disease: Disease state produces acute pain as a result of insult (e.g., chemical, toxic), injury (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy), or disease (e.g., genetic, Parkinson’s, stroke) affecting either the central nervous system (CNS) or peripheral nervous system (PNS) or both.

2: Neuroadaptations: The peripheral and central changes due to the initial insult/injury/disease may endure or cease.

3: Dysfunction in Brain Systems: Using the Basolateral Amygdala (BLA) as an example, nociceptive input may produce changes in brain regions, in this case leading to negative affective states and an increase in pain conditioning to heretofore neutral stimuli.

4: Psychosocial and Biological Exacerbators or Inhibitors: Various factors such as social stress, therapeutic interventions, etc. may exacerbate the processes occurring in brain systems.

5: Neural Networks: Efferent projections of the BLA driving the key emotional, cognitive and behavioral components contributing to the relapse process, namely distress and other negative affective states along with poor inhibitory control, anhedonia, impulsivity and compulsivity. Note that these changes may be increased (red) or decreased (blue) based on afferent drive.

6: Relapse: Pain may be a remitting and relapsing condition. Drivers that alter brain state may change this from subliminal pain (treated) to regain a symptomatic pain state.

Amongst the best examples is Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) which can reoccur following re-injury (e.g., following surgery (Ackerman and Ahmad, 2008; Van Dam and Elliot, 2014)), suggesting a preordained state. Brain imaging studies in children report altered networks for the previously affected vs. unaffected limb, even after the pain has disappeared (Lebel et al., 2008). Such altered states may provide a basis for recurrence in CRPS patients.

The incidence of relapse following initially successful treatment of persistent pain is reported to be between 30–60% (Turk and Rudy, 1991), to be differentiated from treatment non-compliance. The model of relapse in chronic pain may have a parallel in relapse in addiction (Koob and Volkow, 2016; Pickens et al., 2011; Seo et al., 2013; Sinha, 2013). In both conditions where relapse occurs, there is (1) an apparent asymptomatic state; (2) a prior behavioral state, and in both the same behaviors previously exhibited; and (3) a disrupted motivational state (e.g., reward deficit). Thus, in both conditions, an altered brain state exists that is easily resensitized. Pickens et al. use the term “incubation” based on changes in putative brain regions including the mesocortico-limbic system in the VTA (projections to the medial prefrontal cortex accumbens, and amygdala) and the nigrostriatal dopamine system (projecting to the dorsal striatum) (Pickens et al., 2011). Alterations in dopamine function contribute to the emergence of pain or components of pain such as affect (Jarcho et al., 2012; Martikainen et al., 2015; Tiemann et al., 2014). Dopamine may be involved in both reward and aversive signaling and thus in the continuum of pain relief or ongoing pain (Taylor et al., 2016). Some brain regions, known to be involved in pain (Shelton et al., 2012) have been specifically implicated in transition states (e.g., habenula in transition of ‘reward to misery’ in addicts and mood disorders (Batalla et al., 2017).

In Section 2 we provide an overview of a number of clinical conditions that exemplify the following ideas: (1) The evolution and devolution of chronic pain: The phenotypical expression of chronic pain (continuous or intermittent on a regular basis) its very nature usually is not immediate and may evolve over time. The idea of the subliminal onset is captured by the question of when, following acute pain, does pain become chronic, since frequently acute pain may subside and chronic pain evolves later (e.g., post-surgical acute pain vs. post-surgical neuropathic pain). (2) The brain state: resilience to pain may involve a number of factors including genetic, socioeconomic, epigenetic etc. As such, some individuals may have an underlying brain state (e.g., depression or catastrophizing) that sets up brain systems to be more susceptible to chronic pain. As noted, perhaps the best example of this is patients with major depressive disorder may develop a generalized pain disorder. (3) Repetitive drivers for phenotypic change: repetitive barrage of the brain (acute intermittent pain) may drive brain changes (perhaps through recruitment of emotional centers) that produce a chronic pain state. Overall there is evidence to support the hypothesis that there is this unconscious state that is become a pre-pro-pain state that when it reaches a tipping point through still undefined mechanisms (as exemplified by our lack of understanding of the transition from acute to chronic pain), is expressed as chronic pain.

3. The tipping point: neurobiological processes, brain dysfunction

In this section we attempt to provide support for the thesis using neurobiological constructs including a state dependent model in which there are stages of subconscious, preconscious and conscious domains related to subliminal pain and its evolution to chronic pain. Specifically, we first look at this model in the context of allostatic load (Section 3.1: From Nociceptive Allostasis to Allostatic Pain Load and the Evolution of Pain Consciousness) – where a balanced responsive state not only fails, but the addition of stressors may contribute to a negative feedback loop that exacerbates the underlying condition. The second section relates to the proposed model (3.2: Subconscious Processing and the Evolution to the Pain Connectome). These changes contribute to an “altered brain state that is easily resensitized”.

3.1. Pain sensitivity and altered descending modulation

Descending modulation may be considered as a process that thresholds pain awareness. Mechanistic processes may contribute to the submerged (subliminal) or emerged (pain) state of pain that may manifest in differences in the set point that differentiates conscious awareness. Differences in pain sensitivity may relate to genetic (Nielsen et al., 2008) epigenetic (Descalzi et al., 2015), psychological (Nahman-Averbuch et al., 2016) or other factors. Pain sensitivity is increased in patients with comorbid pain conditions (Ashina et al., 2018). Endogenous modulation may be altered by the environment (Gibson et al., 2017) physical and emotional/cognitive (Roy et al., 2011; Villemure and Schweinhardt, 2010) factors. Altered endogenous pain inhibition is observed in numerous and human psychophysical reports in both healthy subjects (Bulls et al., 2015; Niesters et al., 2011) and chronic pain patients (Levy et al., 2017). Disruption of endogenous pain modulation (inhibition or facilitation (see (Bushnell et al., 2013) is also observed in human brain imaging studies across a number of diseases including fibromyalgia (Jensen et al., 2012b) migraine (Chen et al., 2017), orofacial pain (Mills et al., 2018), fibromyalgia (Harper et al., 2018), and diabetic neuropathy (Segerdahl et al., 2018) may be a nice working model for the concept presented here. While the model previously summarized for alterations in descending modulation and pain chronification has been review (Ossipov et al., 2014), the concept of an oscillatory state where the set point defines the presence or absence of pain. One basis for this may relate to changes in neurotransmitters such as serotonin or norepinephrine (Marks et al., 2009) or the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (Lau and Vaughan, 2014) in descending modulatory hubs such as the periaqueductal gray or the effects of such structures by more rostral brain areas (viz., anterior cingulate cortex (Eippert et al., 2009) may contribute to the inflection point seems credible. We have previously suggested a similar theme for migraine onset where depending on the tone of the modulatory circuit pain may be set off or inhibited (Borsook and Burstein, 2012). This theme is summarized in Fig. 4.

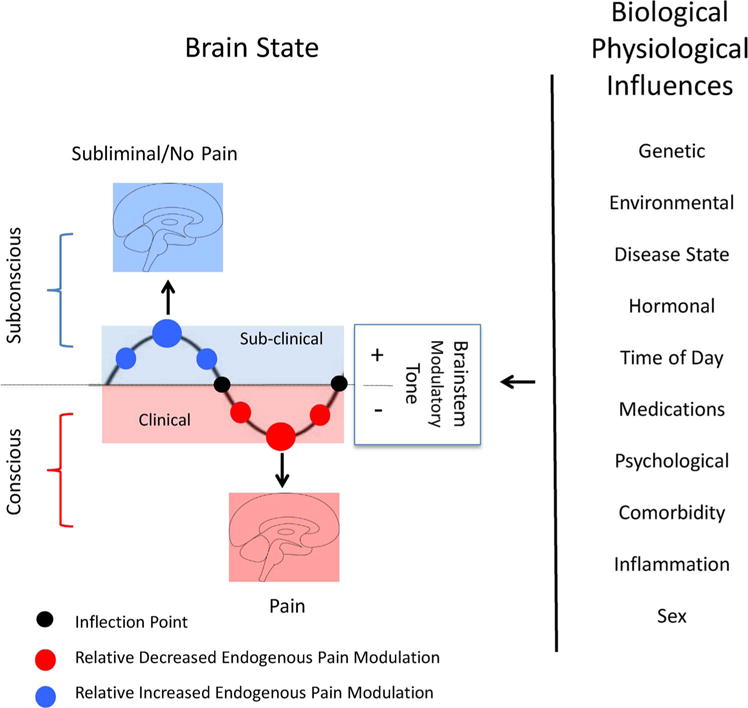

Fig. 4.

Set Point and Descending Modulation: The figure shows Biological and Physiological influences on the Brain State. When a underlying process that causes chronic pain is initiated, subconscious processes persist as a result of antecendant or evolving pacompensatory or robust (+) modulatory tone and brain processes including alterations in brain connectivity (blue brain) that are evolving toward the clinical expression of pain are inhibited. The size of the blue circles represents the level of enhanced modulatory tone. Conceptually patients may have no or minimal pain until they reach an inflection point (black circle). In the clinical sense modulatory tone fails (−) and the pain connectome now presents with the pain behavior/phenotype. The magnitude of failure may correlate with the relative level of pain. The transitions at the set points contribute to conscious vs. unconscious. (See text). (See text).

3.2. Peripheral nociceptive drive – sometimes silent drivers

Spontaneous activity in C-nociceptors is well described in neuropathic pain states (Orstavik et al., 2006; Serra et al., 2012), a process that may contribute to the maintenance of chronic pain. Spontaneous activity may arise in the nerve or in the dorsal root ganglia (Vaso et al., 2014). In conditions such as amputees (Houghton et al., 1994) or complex regional pain syndrome in children (Low et al., 2007) (but less so in adults (Schwartzman et al., 2009)), pain may spontaneously disappear over time, suggesting that the quieting of the input may contribute to this but be reactivated by new damage. However, C fiber activity may be altered by environmental factors (Campero et al., 2009) or activity may be affected by subclinical neuroinflammatory processes. Evidence for evolving pain includes spontaneous activity in uninjured C-fibers after neighboring fibers have been injured (Jang et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2001). Cytokine and Inflammation involving the peripheral nerve have been suggested in some conditions including complex regional pain syndrome (Parkitny et al., 2013), diabetic neuropathy (Doupis et al., 2009), arthritis (Schaible, 2014) and other neuropathic pain conditions (Ellis and Bennett, 2013) may evolve with time to produce the pain state). In these conditions, there may be either an exacerbation or rekindling of pain with an infection including influenza with associated cytokine profile (Van Reeth, 2000) that then enhance or stimulate C fiber activity. In primarily CNS conditions fibromyalgia (Doppler et al., 2015; Harte et al., 2017) such processes implicate complex peripheral nerve-CNS interactions.

3.3. Central neuroinflammation and evolving pain

The role of glia in chronic pain has been the topic of recent papers (Gosselin et al., 2010; Ji et al., 2013). Neuronal-glial interactions have a putative role in maintaining chronic pain (Widerstrom-Noga et al., 2013). Although reported a number of years ago that increased glia activation was present in the thalamus of a patient with CRPS, more recent studies have presented a more compelling story for enhanced glial activity in the brain in chronic pain (Jeon et al., 2017; Loggia et al., 2015). Glial changes have also been implicated in co-morbidities in CRPS (Cooper and Clark, 2013). While unclear on how the glial process may be initiated, it may a process that is subliminal for a time that reaches an inflexion point in the phenotypic presentation of pain and potentially comorbidities that are frequently associated or evolve with fibromyalgia and CRPS (Littlejohn, 2015).

3.4. From nociceptive allostasis to allostatic pain load and the evolution of pain consciousness

The concept of a stable system that responds to perturbations has been used to define how a system may fail as a result of ongoing stressors that contribute to a failing system. Under these circumstances feedback loops are negatively reinforcing. In functional acute pain (for example following surgery with complete recovery of pain symptoms), the process is protective and restorative. In dysfunctional acute pain (for example CRPS that may come about following twisting of an ankle), the process is the harbinger of ongoing changes that leads to chronic pain. As such there is a progression of the “pain biome” with eventual behavioral manifestations of the Pain Connectome. The concept of Pain Load becoming ‘heavier’ provides a basis for the sum of changes that contribute to the evolution, expression, and maintenance of pain consciousness. Fig. 3 summarizes these processes as they relate to the evolution of pain consciousness.

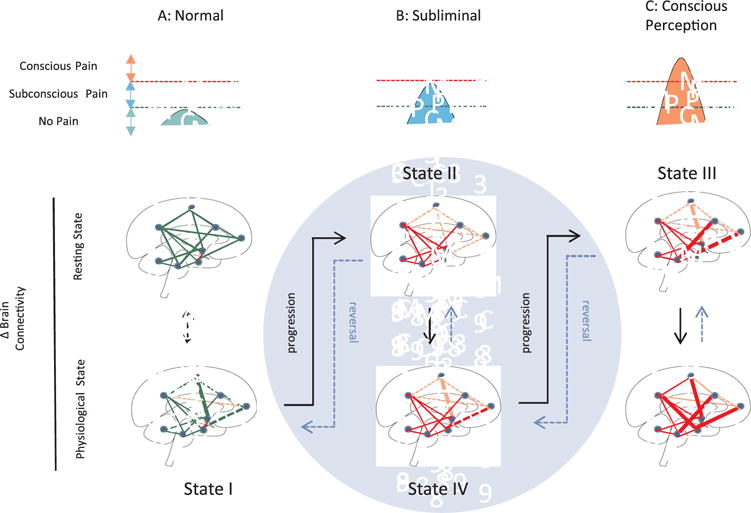

Fig. 3.

Evolution Pain – Temporal Integration of Unconscious Perception to Pain Perception. The changes progress (black arrows) through different States I-III and may reverse (dashed blue arrows) State IV in the subliminal condition (Blue Circle); see Text for details on State specific processes.

A: Normal/Healthy Brain State: Brain circuits (viz., connectivity at rest, functional responsivity and structure) are normal and at rest show normal connectivity (including Default Mode Network). These circuits respond normally to physiological stimuli (e.g., nociceptive input) and then revert back to their homeostatic state. In healthy individuals, the overall strength and connectivity of brain regions is high and responsive in this state (State I).

B: Subliminal Pain State: Following injury, disease or genetic processes that are involved in the eventual development of the pain phenotype, brain circuits become abnormal. Individuals with a premorbid state that enhances their susceptibility to pain (e.g., genetic, sex, emotional) are more likely to progress within Stage II (see (George et al., 2016). In the subliminal or subconscious state these processes escape conscious perception through no or little cortical involvement or through inhibitory processes. The pre-pain state (State III) may include the development of a progressive aversive state with changes in reward function. Such changes may depend on, for example, opioidergic tone (Borsook, 2017). This state may be the harbinger of the pain phenotype or the ‘pain-free’ state with treatment or natural devolution (State IV). Putative functional changes in pain modulation, concentration of inhibitory neurons, or tone of pain related reward-aversion or cognitive and emotional circuits contribute to the maintenance of diminished phenotypic expression.

C: Conscious Perception: The conscious phenotype evolves principally through aberrant brain connectivity that now involves cortical regions. Multiple changes in the brain structure and function evolve and may be responsive to treatment (see (Puiu et al., 2016) or resistant to treatment and become entrenched (stuck).

Consciousness has various terms and definitions (Zeman, 2001) including: “…. the awareness of the sights, sounds, and feelings of everyday experience. In this sense, the system of sensory inputs and outputs of the anterior temporal cortex, amygdala, and the hippocampus must be functional” (Turner and Knapp, 1995). Here we focus the term “consciousness” in two ways: (1) a perception related to the integration of abnormal sensory processing, an awareness of what is being felt or sensed (Leisman and Koch, 2009; Tononi, 2005); and (2) a process related to the evolution of emotional consciousness (Northoff, 2012). It should be noted that some patients that have disorders of consciousness, including a minimally conscious/vegetative state, may communicate that they have pain (Schnakers et al., 2010) opening the issue of what level of consciousness is required for no chronic pain to be experienced. As noted by Sanders and colleagues, “Unresponsiveness = Unconsciousness” (Sanders et al., 2012). The group’s research notes the issues of differentiation of awareness based on brain connectivity or lack thereof (see (Laureys, 2005). Such data may perhaps be extrapolated to include awareness of pain once systems are connected in a certain manner (see below). The theme is the inverse of what this paper tries to focus on – but makes the point that consciousness and behavioral responsiveness (nociceptive or pain behavior) may be disconnected as is the case in general anesthesia, where nociceptive drive is still be present in the unconscious patient (see above). Pain and consciousness have been reviewed elsewhere (Chapman and Nakamura, 1999; Tiengo, 2003). What are the potential neurobiological processes that contribute to latent subconscious processes that evolve into chronic pain? We have subdivided these processes of subconscious processing that contribute to the pain load and that, at some point, break the ‘event horizon’, in other words, a point where the relative state of the brain is no longer limited by inhibitory (maintenance of subconscious processing) mechanisms. The black hole analogy, for which the concept of an event horizon is usually associated with, is perhaps a nice conceptual approach: the subconscious ‘pain’ brain (i.e., little or nothing (behaviorally speaking)) escapes the event horizon in the subconscious pain state.

3.5. Subconscious processing and the evolution to the pain connectome

Recent reports indicate that imperceptible sensory stimuli may alter cortical connectivity (Nierhaus et al., 2015). Indeed, the notion that most sensory information is not perceived. In the Nierhaus study, this was associated with diminished functional connectivity between primary sensory regions and fronto-parietal regions. The data may be interpreted as an increased threshold for perception. Changes in brain connectivity strengths may thus alter endogenous evaluation, including salience and perception. Cortical brain regions involved in subconscious perception may include the somatosensory region itself (Nierhaus et al., 2015), the anterior insula, the precuneus (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006) and the frontoparietal connections (Boly et al., 2011). These regions may influence brain states in a similar manner as exogenous manipulation, such as anesthetics, may do (Hamilton et al., 2017; Hudetz et al., 2015). Individual differences in subconscious behavior may be mediated by tone/connectivity of reward-aversion systems as they relate to dopaminergic tone and release (Marcott et al., 2014; Skyt et al., 2017) and to individual differences in inhibitory neurotransmitters (Boy et al., 2010). With respect to the latter, it is notable that GABA levels predict responsivity to analgesic efficacy in patients with fibromyalgia (Harris et al., 2013), suggesting an underlying state of pain evolution in these patients. By whatever mechanism, there is a breakdown in the connectome where changes in pain related networks do not have strong connectivity with those regions involved in conscious awareness.

In Fig. 1 we provide a cartoon for the evolution of brain systems that are in an increasingly complex but subconscious state that eventually evolves as the Pain Connectome, the state in which behavioral manifestations of pain are present. These behavioral manifestations may be progressive and difficult to restore (treat) or may reverse in nature, either as a result of reconstitution of broken networks or adaptation of other networks. Using the cartoon, we provide evidence, where present, of neurobiological processes that may contribute to the subconscious ‘pain’ state from (A) the Healthy State (no pain behavior) to (B) processes that may be present in the Subliminal Pain State, and finally the expression of (C) the Pain Connectome (see Kucyi and Davis (2015)). Summarized in Fig. 1, further details of the 3 stages are discussed below:

3.5.1. State I: premorbid state (No overt pain behavior)

Individual may either be healthy with no inherent pain-related process or have an underlying (e.g., early depression, fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis) or inciting (e.g., mild nociceptive pain) process. In both cases, the system is in balance and pain behavior is non-existent or minimal. Intrinsic brain activity organizes brain networks that define behavior in health and disease. This activity, when perturbed, for example in response to stress or pain, may show short-term dysfunction that then ‘normalizes’. Brain intrinsic activity is quite robust showing similar networks across populations over time. In other words, this intrinsic activity is “ongoing, involving information processing for interpreting, responding to and predicting environmental demands” (Raichle, 2015). What we define as “normal” intrinsic activity is still debatable because there are sex differences, differences in individuals who may have a predisposition to anxiety or depression, etc. As discussed above, such changes may exacerbate the underpinnings and rate of evolution of pain as it develops, initially in many patients in the subliminal state (see below). Nevertheless, while the intrinsic activity does not have a pain phenotype, the differences between this and the early stages of the subliminal ‘pain state’ are nuanced. Some regions have been specifically implicated in transition states (e.g., habenula in transition of ‘reward to misery’ in addicts and mood disorders (Batalla et al., 2017).

Potential processes that may be risk factors for the development or association of pain include genetic (Costigan et al., 2010; Estacion et al., 2009; Reimann et al., 2010), psychosocial (Innes, 2005), emotional status (Hasenbring et al., 2001; Pincus et al., 2002; Rosenberger et al., 2006), and chronic stress (Abdallah and Geha, 2017) resilience. We have previously summarized these in a prior paper (George et al., 2016). The amalgamated sum of these factors contribute to pain resistance (defined here as the propensity of innate neurobiological (Besson, 1999; von Hehn et al., 2012), neurochemical (Hunt and Mantyh, 2001) and neuroimmune (Calvo et al., 2012; Ren and Dubner, 2010; Scholz and Woolf, 2007) systems to limit the evolution of Stage II, see below) or negative resilience (defined here as the inability of these systems to prevent the march of Stage II changes). While a number of papers address many of these underlying mechanisms from acute to chronic pain (Hasenbring et al., 2001; Kawaguchi et al., 2017; Pincus et al., 2002), some have focused on premorbid psychological status as important (Celestin et al., 2009; Rosenberger et al., 2006).

The evidence for premorbid status in predicting subsequent chronic pain has been focused primarily on genetic, social and emotional processing and are summarized below. We briefly review these in the context of state (I-III) and nature of susceptibility in the context of ‘subliminal’ contributions to pain evolution/progression, since these may contibute to rapid or slow evolution of pain chronification:

Genetic

While a number of genetic predispositions exist to the development of pain, few have been studied in the human condition. Perhaps one of the more intriguing recent studies is on μ opioid receptors related to single nucleotide polymorphism (rs1799971/rs563649) expression evaluated in adolescents and how this relationship can predict pain later in life (Nees et al., 2017). This is an excellent example of how a premorbid state in subjects defines brain responses in neural circuts (here the PAG and accumbens) that alters pain expression later in life. Similarly, other polymorphisms may contribute to altered stress responses (Pecina et al., 2014), post operative chronic pain (viz., genetic variants related to a number of genes (COMT, OPRM1, potassium channel, GCH1, CACNG, CHRNA6, P2 × 7R, cytokine-associated, human leucocyte antigens, DRD2, and ATXN1)) (Hoofwijk et al., 2016). In one study, evaluating polymorphisms as predictors of post surgical pain in nearly 3000 patients, the 2-year post surgical study reported that pain developed with a medial of 4.4 months in 18% of patients (Montes et al., 2015). While no strong genetic-predictive process was observed, the data provides an example of differential evolution of the pain process, common in post-surgical pain.

Social and Emotional

An ustable social and emotional environment contributes to an uncertain state that results in stress (Peters et al., 2017). The emotional status of an individual may set them up to be more susceptible to development of pain. For example, catastrophic thinking predicts pain at 6 months (Vervoort et al., 2010). These two conditions fit in with the thesis most recently summarized on “uncertainty and stress” (Peters et al., 2017) where an ongoing brain-related energy crisis exists that may contribute to ‘a sensitivity of dysfunction’ (i.e., a premorbid state that may relate to the ongoing evolution/susceptibility to brain changes) that conform with a ‘pain connectome’ and therefore the behavioral expression of the latter.

3.5.2. State II: progressive state (Subliminal “Pain” – antecendant or evolving pain)

In our model, either intrinsic or extrinsic factors may contribute to brain changes that are the harbingers of chronic pain. While the etiology of chronic pain is well described (infection, trauma, metabolic, toxic, genetic, etc.), most do not present abruptly. The transition from the healthy state to the chronic pain state, whatever the etiology, must involve a number of processes that initiate, maintain or intermittently exacerbate systems that contribute to the chronic pain state. Perhaps the transition from episodic to chronic migraine is a good, if not, useful example. While episodic migraine is devoid of pain in the interictal phase, it may, with increasing frequency, result in chronic migraine. Another example of a more aggressive state is the rapid evolution from Episodic Migraine into New Daily Persistent Headache. There is now accumulating data on brain structure and function that differentiates these groups of patients. For example, episodic migraine within the interictal phase shows different activity or responsiveness to stimuli (light, sound, emotion, etc.) with increasing frequency, and these networks display differences with increasing frequency of attacks (i.e., migraine chronification) (Schwedt et al., 2013). Intrinsic (e.g., genetic susceptibility, ongoing depression, temporal rate of development of disease) or extrinsic (e.g., acute trauma) processes drive alterations in brain network efficiency, connectivity and strength. These changes remain latent as either the symptoms of acute pain resolve or exacerbate.

What do we know about the neurobiological underpinnings of State II? The networks involved in conscious perception of pain include diverse cortical systems that are not limited to SI (Bushnell et al., 1999; Vierck et al., 2013), Brodmann 10 (Peng et al., 2018), cingulate (Fuchs et al., 2014), insula (Borsook et al., 2016b; Starr et al., 2009) and temporal (Moulton et al., 2011) cortices. Other brain regions such as the amygdala, basal ganglia, hypothalamus, and cerebellum are probably areas most involved in the evolution from subliminal to conscious perception of pain, by initially being ‘undercover’ and eventually, through interactions with different cortical regions, driving a behavioral state of pain consciousness. These areas may be involved in a process called masked priming (Baars and Edelman, 2012; Delacour, 1997). Table 1 lists brain regions involved in pain that may be involved in evolution and subliminal processing of pain.

The “Constitutional State” of an individual is paramount in the evolution of pain awareness. Individuals with a specific biological (genetic, physiological/autonomic, immune, health status, psychological status, prior history of pain) and social background (family status, childhood history) may be more susceptible to developing chronic pain (see above). This status, independent of the underlying process (e.g., trauma, post surgical, evolving rheumatologic disease, nascent fibromyalgia, etc.) that may lead to chronic pain awareness, may be a significant catalyst for the temporal nature of this evolution. Of these issues, some have a sound neurobiological basis and many have been individually well documented in the context of pain risk, and are summarized below:

Prior History of Pain

As with afferent fiber ‘priming,’ prior pain may constitute a form of priming that results in an exacerbation of a response to a new pain process or development. In keeping with this, two pieces of research support this. The first is that pre-operative pain sensitivity predicts postoperative pain intensity (Nielsen et al., 2007) and pain medication use (Buhagiar et al., 2013). Thus, patients with CRPS report greater pain intensity post-surgery than a non-CRPS group undergoing similar surgery (Savas et al., 2017). The second is that prior pain is a predictor of post-operative persistent (up to 1yr after surgery) pain (Andersen et al., 2015; Sieberg et al., 2017). Similarly, rekindling of pain, after treatment may be akin to reintroduction of addiction after treatment (Koob and Volkow, 2016). The system is primed for re-synchronization of reconstitution of the pain connectome (see above).

Neuroimmune processes and Hyperalgesic Priming

A neuroimmune process wherein pro- (e.g., TNFa, IL-6) and anti-inflammatory (e.g., IL-10) molecules contribute to nerve and brain (glia) changes fits in well with the temporal nature of the subclinical evolution to chronic pain awareness (DeLeo et al., 2004; Griffis, 2011; Watkins and Maier, 2005). The theme also integrates independently and dependently a process wherein activation of peripheral inflammatory processes and CNS neuroglia (see above) may contribute to the evolving process including hyperexcitability of the PNS and CNS acting as a driver that may result in the evolution of the pain connectome. One driver is hyperalgesic priming. This is defined as a prolonged latent hyper-responsiveness of nociceptors to inflammatory mediators subsequent to nerve damage (Aley et al., 2000; Kandasamy and Price, 2015; Reichling and Levine, 2009). The notion of hyperalgesic priming has also been applied as it relates to estrogen receptors (Ferrari et al., 2017b) and repeated opioid exposure (Araldi et al., 2017). We are unaware of evidence for similar processes in the CNS that may lead to covert processing of non-consciously perceived ‘stimuli’ that may lead to CNS hyperalgesic priming. Evidence for subliminal priming has been reported in psychological paradigms, implicating a CNS role (Eimer and Schlaghecken, 2003). In TBI, microglia are reported to undergo priming (viz., reactive or sensitized), that may contribute to subsequent clinical problems including ‘second hit’ sensitivity and potential clinical (viz., psychiatric or degenerative) complications (Norden et al., 2015; Witcher et al., 2015). Similar glial priming may occur in chronic pain. Indeed, recent data suggest glial activation in chronic pain (Loggia et al., 2015), but the temporal nature of this process (onset, persistence and offset) is unknown.

All the above processes may contribute to what has been defined as ‘latent sensitization’ in which the remission phase from chronic pain does not represent the healthy state (Marvizon et al., 2015; Walwyn et al., 2016). Thus patients may be more susceptible to the unveiling or recrudescence of pain symptoms and behavior. The concept of latent sensitization has a neurobiological basis (viz., driven by alteration in receptor subtypes, including opioid receptors (Pereira et al., 2015; Walwyn et al., 2016)) can also explain the intermittent nature of chronic pain sensitivity. In the latent process here, the system may undergo suppression of the chronic pain behavior state.

Brain Connectivity including Altered Descending Modulation

The brain state (brain functional connectivity) may confer resistance to the hindrance or development of chronic pain. This includes the basal tone of descending modulatory circuits (see above). Neuroimaging data has supported prediction of sub-acute to chronic pain for both structural (Mansour et al., 2013) and functional (Baliki et al., 2012) measures. However innate status of brain connectivity may provide further evidence of susceptibility of pain development in patients, and this evolving or changing connectivity (dynamic pain connectome) may be latent for days to months or longer. Evidence for altered dysfunction of intrinsic connectivity of brain networks is increased in pain processing networks (Colombo et al., 2015; Kim et al., 2013).

Subliminal processing in non-conscious perception has been reviewed elsewhere (Kouider and Dehaene, 2007), adding to the notion of non-conscious processing without awareness (Peremen and Lamy, 2014). Unconscious processing in the context of pain evolution would necessitate changes in neural networks. CNS-related subliminal priming has been evaluated in non-pain systems, including task-irrelevant, threat-related emotion (Pantazatos et al., 2012) or face emotion processing (Khalid and Ansorge, 2017). The neurobiology of subliminal priming (behavioral modulation by an unconscious stimulus) has been reviewed elsewhere (Jacobs and Sack, 2012). The issue of an unconscious stimulus in pain may be exemplified in the conscious state in patients with congenital insensitivity to pain where empathy to the concept of pain is still present in subjects who have never known a painful stimulus (Danziger et al., 2009). Such changes are in line with central hyperalgesic priming and various putative mechanisms have been suggested (e.g., BDNF in brainstem in rat model of migraine (Burgos-Vega et al., 2016) and Neuroligin 2 in spinal cord GABAergic plasticity (Kim et al., 2016)). For the migraine example, the interictal state may mimic the migraine interictal period that can be triggered.

Within the pain context – two examples may provide insight into these premorbid changes that may be basally present and evolve in time: One set of examples relates to the status of specific regional functional connectivity such as the amygdala-cortical functional connectivity (Vachon-Presseau et al., 2016) or networks involved in endogenous pain modulation (a presumed gateway for increased or decreased responsivity of the pain system) (Staud, 2012; Yarnitsky, 2015). The former may be evaluated in terms of disease development (for example, anxiety disorders (Swartz and Monk, 2014)). The latter, evaluated in terms of functional connectivity (Kim et al., 2011), is of note because individuals with an underlying anxiety disorder (including catastrophizing) are at greater risk (diathesis) to develop chronic pain (Burns et al., 2015).

3.5.3. State III: overt pain behavior – transition to consciousness

An accumulation of imaging data on chronic pain networks in human chronic pain is now available but few studies evaluating sub-clinical manifestations of connectome changes that evolve into chronic have been reported (Lebel et al., 2008). The clinical expression of chronic neuropathic pain following injury, for example, has a wide spectrum of a silent period prior to fulminant expression of pain.

The development of changes in these subcortical structures further contributes to pain connectome development; that is, it provides a basis for changes that produces the chronic pain state: a sensory and emotional process (IASP). Cortical regions may also be involved, but there may be dyssynchrony or disruption of networks as a result of changes that may include structural and chemical changes in the brain of affected individuals. As such, these changes become more dominant/effective and affect the brain until a tipping point is reached and awareness of overt pain is present with all its inherent manifestations – fluctuation of intensity, altered autonomic function, altered pain modulation, etc. The defined dyssynchrony of networks leads to the definable pain state and the formation and definition of what is now called the “Pain Connectome” (rather than the now outmoded formulation of the “Pain Matrix)” (Kucyi and Davis, 2015).

While this stage can be aligned with the so-called ‘transition from acute to chronic pain’ in this thesis, these are not exactly the same but may have some parallel changes. Current neuroimaging methods have suggested that there is a ‘switch’ from predominantly sensory processing to engage emotional circuitry (Hashmi et al., 2013). However, this change probably can also be accounted for by more rapid subliminal changes argued herein. The factors that need to be considered include processes such as a delay in transition (it is variable in disease type (e.g., following stroke (Vartiainen et al., 2016) or Parkinson’s Disease (Defazio et al., 2008; Skogar and Lokk, 2016)), age as shown in animal models (Vega-Avelaira et al., 2012), and individuals’ specific biological constitutions including sex (Ferrari et al., 2017a)). Furthermore, while specific functional (Baliki et al., 2012) and anatomical (Mansour et al., 2013) changes are present in the acute – chronic transition, other networks are probably involved in subliminal processing. Of these, the salience network potentially plays a large role in the transition to “behavioral dysfunction” (Palaniyappan and Liddle, 2012; Uddin et al., 2015). Salience network involvement in pain has been reviewed elsewhere (Borsook et al., 2013). Chronic pain evolution may include the contribution of aberrant functioning of the brain circuits that define salience values to stimuli. Such a large-scale brain network may then contribute to a number of defined phenomena including response to placebo/nocebo, evolution of pain responsivity, etc. Salience networks are altered in animal models of pain (Becerra et al., 2017) and across most chronic pain conditions, including visceral pain (Gupta et al., 2017), sickle cell disease (Zempsky et al., 2017) and CRPS (Becerra et al., 2014), to name a few examples. Large-scale networks ‘support allostasis and interoception’ (Kleckner et al., 2017). We are unaware of any study that reports the changes in networks in the evolution of State I to State III.

Primed Actions or Effects of Treatments may Contribute to Faulty Sensory-Emotional and Modulatory Processing

There is growing evidence that some treatments for pain may worsen the condition. In the migraine field, both opioids and excessive triptans (the latter being highly specific anti-migraine drugs) contribute to disease chronification (Bigal and Lipton, 2008b). The same may occur in the chronic pain field of which opioid induced chronification may be the best example. For those drugs that affect central systems, such as opioids (Lee et al., 2011), they may prime pain systems or alter neural networks to contribute to further disruption and disarray of the very systems that they are targeting (see (Borsook et al., 2016a).

Non-conscious Processing of Sensory and Emotional Stimuli

Negative affective and pain-related cues may be an ongoing process in chronic pain patients (Richter et al., 2014). Thus, subconscious emotional and sensory aversion may contribute to maintaining the pain state. For example, in migraine patients, an aversive response to negative emotional pictures has been reported (Wilcox et al., 2016); furthermore, negative responses to unpleasant odors have been reported to enhance chronic pain in a patient with neuropathic pain (Villemure et al., 2006). Conversely, in migraineurs, colors in the green wavelength diminish photophobia (Noseda et al., 2016). Such ongoing, for the most part, unconscious processes may contribute to the persistence of chronic pain.

3.5.4. State IV: subliminal processes involved in reversal of chronic pain

While some chronic pain conditions may stay constant or worsen (i.e., pain gets stuck), many reverse. The corollary of the above theme (i.e., silent evolution of pain onset) is observed clinically. A few concepts based on clinical insights may provide insights into subclinical processes that may have different temporal profiles in terms of resolution. In all cases, such changes reflect ‘trend towards normal’ of the healthy connectome.

Treatment Delay and Target Resilience

Data suggests that early treatment in the course of a chronic pain condition may provide better results. Perhaps the best example is that of early aggressive treatment of herpes zoster wherein early aggressive treatment may prevent chronic pain (post-herpetic neuralgia) (Johnson and Dworkin, 2003). In the context of unfolding of chronic pain, while constitutional processes (viz., genetic, emotional) may contribute, early treatments may be more effective in limiting if not reversing the evolution of chronic pain (McGreevy et al., 2011; Winston, 2016).

Unraveling of Treated Status

The treated status does not necessarily indicate complete remission to the healthy status. There are two examples of this: (1) Pain Recrudescence – Pain and or its related co-morbidities may remit and then rekindle. For example, following remission of CRPS, patients may still have chronic pain later even after apparent remission (Anderson and Fallat, 1999). (2) Delayed Relapse – Pain in children may remit and then be present either in a multiple pain format including vulnerabilities of comorbidities (e.g., depression or anxiety) or in the same disease (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome, IBS), years later (Shelby et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2010, 2012).

In the two themes noted above, brain circuits are either primed (see above) or abnormal. In support of this, in fully asymptomatic children who have recovered from CRPS, their brain systems remain abnormal in terms of responsivity to stimuli (Lebel et al., 2008) (See below). The take home message here, as it relates to subliminal processing, is that changes that are not behaviorally evident continue, potentially in the same manner as that noted for State II.

In Section 3 we provide a neurobiological construct, although general, in terms of allostatic load and how this may contribute to a negative sensory and emotional state, exacerbating the underlying condition and bringing pain consciousness to fruition. The model that encompasses Stages I–IV provides a testable approach to evaluating Subliminal/Latent Pain.

4. Conclusions

The enigma of transition from no pain to chronic pain is fraught with difficulties in definition of state and of process. While some chronic pains are “immediate” and present at the time of injury, for example spinal cord trauma, post surgical pain, stroke, and then persist, many evolve over time. While many have reported on the topic, the notion of the undercurrent, silent process that is likely to be ongoing provides a rational basis for a theoretical construct with implications for treatments if new approaches to defining the conditions are made accessible to health care providers.

The concept of subconscious pain processing attempts to address pre-awareness pain. It is a preventive approach to pain that deserves more attention in research and in the clinic for a number of reasons including but not limited to: early pain is easier to treat, diminishing the cost to society and the individual, possible for current non-opioid drugs to be more effective. As such, this endeavor deserves more attention in terms of further defining the neurobiology, having appropriate diagnostic measures, and reconsidering treatments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH Grant from NICHDR01HD083133 to DB.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abdallah CG, Geha P. Chronic pain and chronic stress: two sides of the Same coin? Chronic Stress (Thousand Oaks) 2017 doi: 10.1177/2470547017704763. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2470547017704763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ackerman WE, 3rd, Ahmad M. Recurrent postoperative CRPS I in patients with abnormal preoperative sympathetic function. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aley KO, Messing RO, Mochly-Rosen D, Levine JD. Chronic hypersensitivity for inflammatory nociceptor sensitization mediated by the epsilon isozyme of protein kinase C. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4680–4685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-12-04680.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand P, Birch R. Restoration of sensory function and lack of long-term chronic pain syndromes after brachial plexus injury in human neonates. Brain. 2002;125:113–122. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen KG, Duriaud HM, Jensen HE, Kroman N, Kehlet H. Predictive factors for the development of persistent pain after breast cancer surgery. Pain. 2015;156:2413–2422. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DJ, Fallat LM. Complex regional pain syndrome of the lower extremity: a retrospective study of 33 patients. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1999;38:381–387. doi: 10.1016/s1067-2516(99)80037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ang ST, Ariffin MZ, Khanna S. The forebrain medial septal region and noci-ception. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2017;138:238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araldi D, Ferrari LF, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic priming (type II) induced by repeated opioid exposure: maintenance mechanisms. Pain. 2017;158:1204–1216. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashina S, Lipton RB, Bendtsen L, Hajiyeva N, Buse DC, Lyngberg AC, Jensen R. Increased pain sensitivity in migraine and tension-type headache coexistent with low back pain: a cross-sectional population study. Eur J Pain. 2018 doi: 10.1002/ejp.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Katz J. Understanding the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and chronic pain: state-of-the-art. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:888–901. doi: 10.1002/da.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars BJ, Edelman DB. Consciousness, biology and quantum hypotheses. Phys Life Rev. 2012;9:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bair MJ, Poleshuck EL, Wu J, Krebs EK, Damush TM, Tu W, Kroenke K. Anxiety but not social stressors predict 12-month depression and pain severity. Clin J Pain. 2013;29:95–101. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3182652ee9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Petre B, Torbey S, Herrmann KM, Huang L, Schnitzer TJ, Fields HL, Apkarian AV. Corticostriatal functional connectivity predicts transition to chronic back pain. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1117–1119. doi: 10.1038/nn.3153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA, Morsella E. The unconscious mind. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3:73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2008.00064.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batalla A, Homberg JR, Lipina TV, Sescousse G, Luijten M, Ivanova SA, Schellekens AFA, Loonen AJM. The role of the habenula in the transition from reward to misery in substance use and mood disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Bishop J, Barmettler G, Kainz V, Burstein R, Borsook D. Brain network alterations in the inflammatory soup animal model of migraine. Brain Res. 2017;1660:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Borsook D. Signal valence in the nucleus accumbens to pain onset and offset. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:866–869. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Sava S, Simons LE, Drosos AM, Sethna N, Berde C, Lebel AA, Borsook D. Intrinsic brain networks normalize with treatment in pediatric complex regional pain syndrome. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;6:347–369. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt RP. Hippocampus and consciousness. Rev Neurosci. 2013;24(3):239–266. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2012-0088. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/revneuro-2012-0088. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besson JM. The neurobiology of pain. Lancet (London, England) 1999;353:1610–1615. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)01313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Concepts and mechanisms of migraine chronification. Headache. 2008a;48:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigal ME, Lipton RB. Excessive acute migraine medication use and migraine progression. Neurology. 2008b;71:1821–1828. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335946.53860.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boly M, Garrido MI, Gosseries O, Bruno MA, Boveroux P, Schnakers C, Massimini M, Litvak V, Laureys S, Friston K. Preserved feedforward but impaired top-down processes in the vegetative state. Science. 2011;332:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1202043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsook D. Opioidergic tone and pain susceptibility: interactions between reward systems and opioid receptors. Pain. 2017;158:185–186. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]