Abstract

In light of the ongoing antimicrobial resistance crisis, there is a need to understand the role of co-pathogens, commensals, and the local microbiome in modulating virulence and antibiotic resistance. To identify possible interactions that influence the expression of virulence or survival mechanisms in both the multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and human host cells, unique cohorts of clinical isolates were selected for whole genome sequencing with enhanced assembly and full annotation, pairwise co-culturing, and transcriptome profiling. The MDROs were co-cultured in pairwise combinations either with: (1) another MDRO, (2) skin commensals (Staphylococcus epidermidis and Corynebacterium jeikeium), (3) the common probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri, and (4) human fibroblasts. RNA-Seq analysis showed distinct regulation of virulence and antimicrobial resistance gene responses across different combinations of MDROs, commensals, and human cells. Co-culture assays demonstrated that microbial interactions can modulate gene responses of both the target and pathogen/commensal species, and that the responses are specific to the identity of the pathogen/commensal species. In summary, bacteria have mechanisms to distinguish between friends, foe and host cells. These results provide foundational data and insight into the possibility of manipulating the local microbiome when treating complicated polymicrobial wound, intra-abdominal, or respiratory infections.

Introduction

The emergence of Multiple Drug Resistant Organisms (MDROs) that exhibit resistance to at least three classes of antibiotics1, and the frequency of serious infections caused by MDROs combined with the lack of development and approval of new antibiotics has led the World Health Organization (WHO), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) to declare that antimicrobial resistance poses an urgent threat to global public health2–4. In addition to new antibiotics that are not inactivated by the resistance mechanisms described below5, alternative and or adjunctive treatment strategies are critically needed6,7.

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and Enterobacter species are some of the most challenging MDROs to treat, especially when they are isolated with other co-pathogens and/or commensals from polymicrobial respiratory, intra-abdominal and wound infections8–10. These organisms have evolved and/or horizontally acquired a diverse arsenal of resistance mechanisms11, including transmembrane transporters known as efflux pumps, drug neutralizing enzymes such the carbapenemases12 and extended spectrum beta-lactamases13,14, and mutations in ribosomal RNA (rRNA)15 or topoisomerase genes16 to escape the target of the drug. Plasmids17, integrative conjugative elements (ICE)18, integrons19, resistance islands20 and even bacteriophage21 have all aided and abetted in disseminating antibiotic resistance genes between diverse bacterial species. Despite all we know regarding resistance mechanisms, it is not clear what role, if any, co-infecting pathogenic, resident microbiota, or the human host may have in influencing the expression of antibiotic resistance genes and virulence factors and ultimately pathogenicity of infectious species.

Microbial communities consist of multiple species in commensal or symbiotic coexistence where cells can communicate via quorum sensing and influence interactions with each other. To detect these biological interactions, classical studies have used co-culture assays to monitor the effects of a pathogen/commensal species on the growth or survival of the target species. Such co-cultures have been implicated in the induction of genes and cellular structures required for competitive viability22,23. In a few cases, genome-wide transcriptomic changes have been measured and results from these studies suggest that microbial gene expression can be extensively reprogrammed by other microbes in the same niche22,24–26. Growth inhibition as a result of co-culture assays have been reported among human resident or pathogenic bacteria (such as P. aeruginosa against S. aureus25, and Streptococcus sanguinis against Streptococcus mutans27, and certain groups of soil bacteria and fungi (such as Bacillus subtilis against Streptomyces coelicolor28, Collimonas fungivorans against Aspergillus niger26, and Pseudomonas fluorescens against Bacillus, Brevundimonas or Pedobacter22. There are also examples demonstrating the influence of host factors on virulence strategies of the pathogen such as the induction of antibiotic resistance in the presence of human host cells29,30 or sub-inhibitory concentrations of antibiotics31. Co-culture studies are valuable in understanding co-infection with more than one type of MDRO32. For example, in some studies, co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and Acinetobacter has been associated with a higher level of resistance to carbapenems33. Co-infection can also manifest cross-kingdom effects by regulating the survival of the host. Caenorhabditis elegans showed better survival when co-infected with both Candida albicans and A. baumannii instead of C. albicans alone34. Thus, it appears that A. baumannii may attenuate the growth of a competing organism, thereby directly influencing the outcome of a co-infection and the survival of the nematode.

Although there have been microarray and RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) based transcription profiles of bacterial co-culture and host-pathogen interactions22,35–38, there is a lack of information on how different nosocomial MDROs respond to each other and to the inhabitants of the human skin microbiome, and whether this interaction might affect regulation of genes that ultimately influence the virulence capacity of the organisms. In this study, we conducted genome-wide RNA-Seq gene expression analysis to reveal the transcriptional regulation of individual MDROs when co-cultured with or confronted against another MDRO, selected probiotic and skin commensal organisms, or cultured human cells. The primary goal was to identify and characterize interactions among bacteria and host that influence the expression of virulence factors and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in MDROs.

Results and Discussion

Whole Genome Sequencing of MDROs

MDROs used in this study were selected by collaborators at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) Multidrug-resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network (MRSN) as having one or more of the following characteristics: polytraumatic blast injuries, initial injuries in Afghanistan or Iraq, multi-drug resistant, isolated from traumatic wound surfaces or surveillance culture, and/or outbreak in the DOD health system from 2003–2015. Details of the multiple selection criteria that apply to each isolate are summarized in Supplementary Table S1. The antibiogram for the 3 selected MDROs was included as Supplementary Table S2. Bacteria considered human commensals and members of the human skin microbiome were chosen as confronting partners if they can be cultured aerobically at 37 °C and on media similar to the selected MDROs, and if their genome sequence was publicly available. Preference was also given to those isolates known to inhabit skin39,40. L. reuteri was chosen due to its growing use as a probiotic41,42.

Although strains of a given bacterial species are highly similar, their gene content can vary by as much as 35%43. The differences among bacterial strains tend to be mobile elements (e.g., prophage, plasmids, integrated elements) and genes encoding for O-antigen or capsular polysaccharides (CPS)44–48. These “flexible” regions tend to encode genes involved in cell surface structures (i.e., O-antigen, CPS, teichoic acid, S-layer, flagella, pili, and porins) as well as genes for resource utilization, including antibiotic resistance genes. These regions that vary between strains have been referred to as flexible genomic islands (fGIs)49,50. To avoid missing biologically important genes within MDROs that may not be present in generic reference genomes, and to more precisely map mRNA transcripts generated during bacterial co-culture experiments, draft genome sequencing of these clinically relevant MDRO isolates was conducted.

All three MDRO isolates were sequenced to a high depth of coverage (e.g., 79 to 115-fold) and improved using reads from other sequencing technologies, optical maps, and an in-house automated genome finishing tool, resulting in the genome finishing status of “Improved High-Quality Draft” (IHQD) (Table 1). Plasmid-related contigs were discovered in all three genomes: two in A. baumannii MRSN 7339, three in E. hormaechei MRSN 11489 and 23 in K. pneumoniae MRSN 1319. A list of the plasmid-related contigs can be found in Supplementary Table S3. In the K. pneumoniae and E. hormaechei isolates, plasmid-encoded genes were identified that belong to the Type IV secretion system, for example, the tra and virB gene clusters, likely involved in conjugation. For AMR genes, a total of 10 and 5 were annotated on plasmid-derived contigs in the K. pneumoniae and E. hormaechei isolates, respectively. The AMR genes encode for inhibitors against various drug class combinations of beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones, phenicols, sulfonamides, and/or trimethoprim. As for the A. baumannii isolate, interestingly, the AMR genes were not detected on the plasmid-derived contigs but instead 15 AMRs genes, against beta-lactams, aminoglycosides, quinolones, and trimethoprim, were identified on the chromosome. Plasmid-derived genes from the 3 MDROs can be found in Supplementary Tables S4–S6.

Table 1.

Genomic features and metadata of bacterial genomes used in this study.

| Repository ID | MRSN 1319 | MRSN 7339 | MRSN 11489 | ATCC 55730 | BEI HM-118 | ATCC 43734 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organism | K. pneumoniae | A. baumannii | E. hormaechei | L. reuteri SD2112 | S. epidermidis SK135 | C. jeikeium |

| Accession | JSVB00000000 | JPHV00000000 | JTEP00000000 | CP002844 | ADEY00000000 | ACYW00000000 |

| Group | MDRO | MDRO | MDRO | Commensal | Commensal | Commensal |

| Origin | wound | wound | wound | breast milk | skin | blood culture |

| Sequencing Technology | Illumina HiSeq. 2000 | Illumina HiSeq. 2000 | Illumina HiSeq. 2000 | Roche 454 | Roche 454 | Roche 454 |

| Finishing Status† | IHQD | IHQD | IHQD | Finished | HQD | HQD |

| Average Coverage | 79.23× | 115.46× | 94.99× | 63× | 26× | 35× |

| #Contigs | 52 | 34 | 28 | 5 | 33 | 93 |

| Contig N50 | 392,725 | 246,634 | 332,009 | na | na | na |

| Average Contig Length (bp) | 105,180 | 116,337 | 165,823 | 463,368 | 76,304 | 26,091 |

| Max. Contig Length (bp) | 765,691 | 847,614 | 652,496 | 2,264,399 | 751,210 | 161,413 |

| Total Genome size (bp) | 5,469,353 | 3,955,466 | 4,643,032 | 2,316,838 | 2,518,045 | 2,426,461 |

| Total G + C% | 57.31 | 39.09 | 55.30 | 39.04 | 32.24 | 61.63 |

| #Proteins | 5,430 | 3,787 | 4,513 | 2,300 | 2,395 | 2,224 |

| #Plasmid contigs | 23 | 2 | 3 | 4 | nd | nd |

| References | This study | Chan et al., 2015 | This study | Spinler et al., 2014 | BEI Resources | Jackman et al., 1987 |

†Improved High-Quality Draft (IHQD); High-Quality Draft (HQD).

na = Not available or applicable.

nd = Not determined.

Co-cultures of selected MDROs and human skin microbiome species

The skin represents a complex microbial ecosystem, with interactions between microbial species, and between microbes and the host. Common skin inhabitants include bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Many of the microbes that colonize the skin are harmless and may play a beneficial role through colonization and protection against invasion by pathogens. The resident skin microbes may also offer an additional line of defense through priming the host immune system to counteract possible attacks by pathogens. The skin microflora consists of four major phyla: Actinobacteria (e.g., Corynebacterium, Propionibacterium, Micrococcus), Firmicutes (e.g., Staphylococcus), Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria39.

We selected A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, E. hormaechei isolates from the WRAIR MRSN as the MDRO pathogen species, S. epidermidis and Corynebacterium jeikeium as the representative skin commensal residents, and L. reuteri as a probiotic representative, focusing on the responses of the MDROs to each other and the selected pathogen/commensal species. The pairwise co-culture assays among MDROs and the commensals or probiotics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Bacteria-Bacteria Confrontation Assays.

| Confronting bacteria | Commensal Controls | MDRO species | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. hormaechei | K. pneumoniae | A. baumannii | |||

| EH | KP | AB | |||

| L. reuteri | LR | LR:LR | EH:LR | KP:LR | AB:LR |

| S. epidermidis | SE | SE:SE | EH:SE | KP:SE | AB:SE |

| C. jeikeium | CJ | CJ:CJ | EH:CJ | KP:CJ | AB:CJ |

| E. hormaechei | EH | na | EH:EH | KP:EH | AB:EH |

| K. pneumoniae | KP | na | na | KP:KP | AB:KP |

| A. baumannii | AB | na | na | na | AB:AB |

na = Not available or applicable.

The total number of trimmed mapped reads from each organism per pairwise co-culture assay is summarized in Supplementary Table S7. A total of 388 and 321 A. baumannii genes (out of 3,860 genes in the genome) were up or down-regulated when co-cultured with K. pneumoniae and E. hormaechei, respectively. As many as 909 and 212 K. pneumoniae genes (out of 5,548 genes in the genome) were up or down-regulated when co-cultured with A. baumannii and E. hormaechei, respectively. Compared to the other two MDROs, E. hormaechei gene expression was only moderately affected when co-cultured with A. baumannii or K. pneumoniae, with 78 and 15 up or down-regulated genes out of 4,617 genes in the genome, respectively. A summary of differentially regulated gene counts obtained from co-cultures are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Differentially expressed gene in the MDROs E. hormaechei, K. pneumoniae, and A. baumannii when confronted with individual pathogenic/commensal bacteria.

| MDRO species | #Annotated genes in genome | Regulation | Confronting Bacteria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. baumannii | K. pneumoniae | E. hormaechei | C. jeikeium | S. epidermidis | L. reuteri | |||

| A. baumannii | 3,860 | Up | na | 200 | 171 | 191 | 9 | 0 |

| Down | na | 188 | 150 | 233 | 3 | 1 | ||

| K. pneumoniae | 5,548 | Up | 466 | na | 60 | 46 | 18 | 5 |

| Down | 443 | na | 152 | 118 | 94 | 9 | ||

| E. hormaechei | 4,617 | Up | 71 | 13 | na | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Down | 7 | 2 | na | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

Differentially expressed genes are defined as genes with an FDR <0.05 from edgeR analysis. Annotated genes included protein-coding, tRNA, tmRNA, and ncRNA.

na = Not available or applicable.

S. epidermidis (a skin resident) and L. reuteri (a common probiotic) stimulated the least gene expression responses when co-cultured with the MDROs. It is possible that the growth of commensal organisms was impaired by the MDROs in co-culture since growth inhibition has been observed previously in bacterial confrontations22,23. To determine if the MDROs were inhibiting the growth of the commensal organism, phenylethyl-alcohol and Hektoen Enteric selective agars were used to quantitate colony forming units of S. epidermidis and E. hormaechei, respectively during co-culture. No growth inhibition was observed (Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that slower growth patterns and low biomass at the end of the co-culture was the cause for the low amount of RNA-Seq reads, at least for the E. hormaechei-S. epidermidis confrontation. The same analysis could not be performed with the other commensal bacteria in this study because of their specific media requirements and the fact that other MDROs, A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae, both possess alcohol-dehydrogenase genes, which would have allowed growth on the selective phenylethyl-alcohol agar.

Genes responsive in co-culture ranked by fold-change

We also examined extreme up/down gene responses of MDROs under co-culture conditions by requiring at least 4-fold up/down expression with FDR below 5%. For A. baumannii, a total of 25 and 19 genes were strongly up/down regulated respectively when co-cultured with E. hormaechei (Supplementary Fig. S2). A major fraction of the same gene set was similarly regulated when A. baumannii was co-cultured with another MDRO K. pneumoniae. Amongst the most strongly upregulated genes, by 11 to 12-fold, were alcohol dehydrogenase (T634_RS01410), aldehyde dehydrogenase (T634_RS01395), and lipoyl synthase (T634_RS06340). Two MFS transporters (T634_RS14350, T634_RS14800) and an outer membrane porin of the OprD family (T634_RS14805) were strongly downregulated by 5 to 10-fold.

As for K. pneumoniae gene responses, 24 and 14 genes were up/down regulated respectively when the co-culture was performed with A. baumannii (Supplementary Fig. S3). The strongest K. pneumoniae gene response was found in genes involved in iron acquisition, including TonB-dependent receptor (T643_RS07920; 45-fold), iron ABC transporter permease (T643_RS07935; 39-fold), hemin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein (T643_RS07930; 36-fold), and hemin-degrading factor (T643_RS07925; 34-fold). When the co-culture partner used was E. hormaechei instead, a different gene response was observed which involved a strong downregulation of the enterobactin gene clusters required for siderophore synthesis (discussed below).

Finally, a total of 25 E. hormaechei genes responded to co-culturing with A. baumannii or K. pneumoniae. Most genes were strongly upregulated when co-cultured with A. baumannii with the exception of a hypothetical protein (T636_RS15175) which was down-regulated (Supplementary Fig. S4). The most strongly upregulated E. hormaechei genes were involved in iron transport including ligand-gated channel protein (T636_RS04035), hemin uptake protein (T636_RS04030), hemin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein (T636_RS04045) by 21 to 32-fold when co-cultured with A. baumannii, followed by the enterobactin and aerobactin siderophore synthesis gene clusters (also discussed below).

Regulation of AMR genes during co-culturing

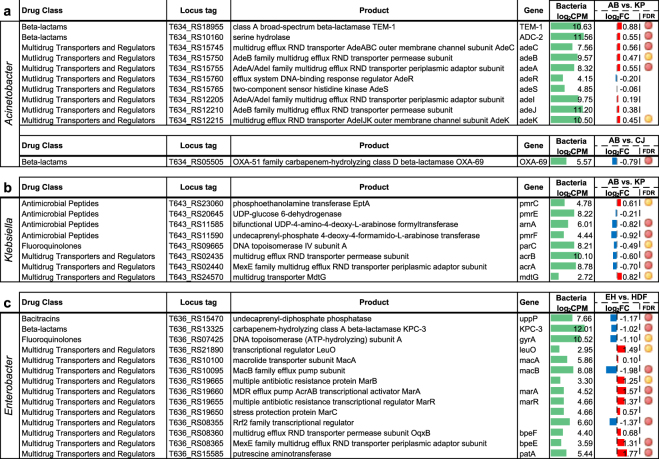

It is known that AMR is critically important to the survival strategy of the MDROs used in this study and that expression of AMR determinants has a fitness cost associated with it, but it is unknown to what extent AMR gene (ARG) expression is influenced by other co-cultured microbes. To determine effects of MDRO bacterial challenge on the expression of ARGs, we first identified ARGs using the Resistance Gene Identifier (RGI)51 in strict mode against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)51–53. RNA-Seq analysis showed significant differential expression of ARGs when K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii were co-cultured, with patterns of up- and down-regulation observed within each species (Fig. 1a,b). In A. baumannii, both the TEM-1 and ADC-2 beta-lactamase variants were upregulated when challenged with K. pneumoniae along with RND-family efflux systems adeABC and adeIJK. Conversely, in K. pneumoniae, lipid A modifying enzymes responsible for antimicrobial peptide resistance (arnA, pmrE, and pmrF), multi-drug transporters acrAB, and quinolone resistance protein parC, were downregulated when challenged with A. baumannii. Exceptions of ARGs being up-regulated in K. pneumoniae were pmrC and mdtG. There were few significant ARG expression changes observed in MDROs when co-cultured with commensals. For E. hormaechei, no significant differentially expressed ARG was observed when challenged with any of the other bacteria – MDROs or commensals. One notable mention is the down regulation of the beta-lactamase OXA-69 (an OXA-51 subfamily carbapenemase54) in A. baumannii when co-cultured with the skin commensal C. jeikeium (Fig. 1a). This finding would be of considerable interest to the healthcare industry if the co-culturing of a skin commensal could result in an increase in susceptibility of A. baumannii to carbapenems through the lowering of the intrinsic OXA-51-like gene expression. This finding could also inform treatment decisions – for example by avoiding the concomitant use of vancomycin which kills commensals such as coagulase negative staphylococci and corynebacterial species.

Figure 1.

Antimicrobial resistance gene expression. Differentially regulated AMR genes in A. baumannii (AB) (a), K. pneumoniae (KP) (b) during bacterial co-culture experiments, and E. hormaechei (EH) in response to co-cultured HDF cells (c) are shown. (CJ) denotes C. jeikeium. Differentially regulated genes shown with edgeR false discovery rate (FDR): <0.05 (red circle) and <0.1 (yellow circle). Log2-fold change values of gene expression was shown as red (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated) bar graphs with reference to monocultures. Bar scale from −4 to 4. Averaged gene expression level across control and treatment experiments (log2 read counts per million, log2CPM) was shown as green bar graphs. Bar scale from 0 to 15.

When confronted with HDF cells, transcriptome analysis of E. hormaechei showed significant changes in ARG expression (Fig. 1c). Most notable, the antibiotic efflux complexes marABC and bpeEF were upregulated when challenged with HDF cells, while the macB periplasmic ATPase component of the macAB cassette and the KPC-3 beta-lactamase variant were downregulated. In K. pneumoniae, the aminoglycoside APH(3″)-Ib and beta-lactam resistance enzyme CTX-M-15 were downregulated in the presence of HDF. No significant differentially expressed ARGs were observed in A. baumannii when co-cultured with HDF cells.

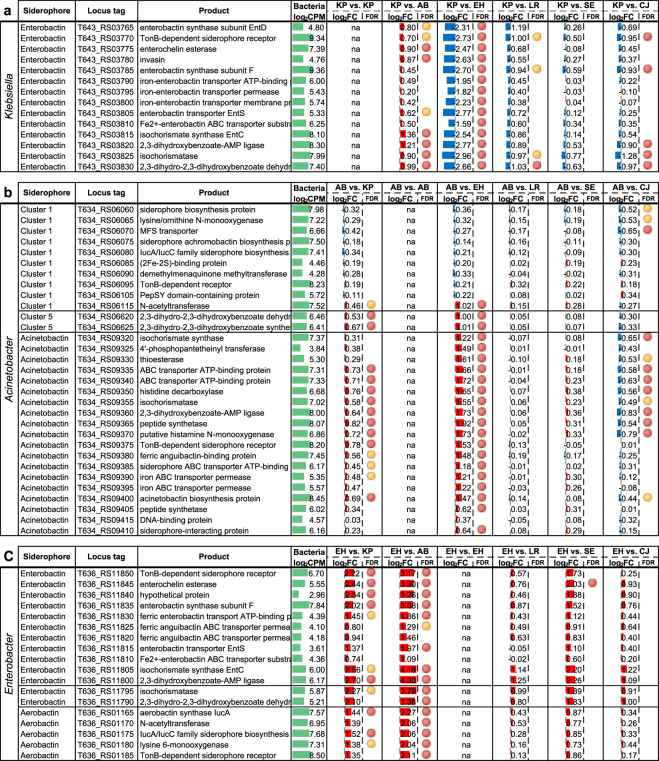

Differential expression of siderophore gene clusters

Siderophores are molecules essential for iron acquisition and the survival of bacteria, and are especially important for pathogens to compete for limiting free iron in an eukaryotic host environment. To determine how siderophore gene clusters are regulated during bacterial co-culture, we identified the corresponding siderophore gene clusters including acinetobactin in A. baumannii, enterobactin in K. pneumoniae, and both enterobactin-like and aerobactin in E. hormaechei. Genome-wide RNA-Seq expression and annotated virulence gene sets are shown in Supplementary Tables S4–S6. Across the 6 MDRO pairwise analysis performed, siderophore gene cluster expression was upregulated in almost all cases (Fig. 2). The only exception observed was when K. pneumoniae was co-cultured with E. hormaechei (i.e. KP vs. EH, Fig. 2a) in which case the K. pneumoniae enterobactin cluster was strongly downregulated by 8-fold (log2 fold change of 3) in the presence of E. hormaechei. Interestingly, although both K. pneumoniae and E. hormaechei encode enterobactin, only K. pneumoniae downregulated the transcription of enterobactin in the presence of E. hormaechei but not vice versa. Conceivably, K. pneumoniae may have evolved iron utilization feedback mechanisms to largely shut down production of enterobactin in favor of utilizing the enterobactin produced by Enterobacter. In contrast, the expression of the A. baumannii siderophore acinetobactin was consistently upregulated regardless whether the co-cultured pathogen was K. pneumoniae or E. hormaechei.

Figure 2.

Siderophore gene cluster expression in (a) K. pneumoniae (enterobactin), (b) A. baumannii (acinetobactin), and (c) E. hormaechei (enterobactin-like and aerobactin) when co-cultured with individual pathogen/commensal species. K. pneumoniae (KP), A. baumannii (AB), E. hormaechei (EH), L. reuteri (LR), S. epidermidis (SE) and C. jeikeium (CJ). Differentially regulated genes shown with edgeR false discovery rate (FDR): <0.05 (red circle) and <0.1 (yellow circle). Log2 fold change values of gene expression was shown as red (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated) bar graphs with reference to monocultures. Bar scale from −4 to 4. Averaged gene expression level across control and treatment experiments (log2 read counts per million, log2CPM) was shown as green bar graphs. Bar scale from 0 to 15.

When the MDROs were individually co-cultured with the common skin resident C. jeikeium, a mild down-regulation of the K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii siderophore gene clusters was also observed (Fig. 2). The C. jeikeium-mediated reduction of siderophore production in competing co-cultured species could be a defense mechanism of commensals to outcompete invading pathogens in the human host.

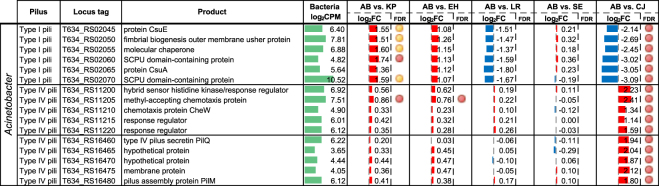

Differential expression of cell attachment components

Pili and fimbriae systems are important for cell attachment and physical interactions; therefore, we also performed extensive annotation of the three selected MDRO genomes to identify genes involved in surface attachment, including type I and type IV pili and fimbriae proteins. RNA-Seq analysis showed that one of the three annotated csu chaperone gene clusters in A. baumannii (type I pili formation) was upregulated when co-cultured with K. pneumoniae by 3-fold, but distinctly downregulated almost 8-fold only when co-cultured with C. jeikeium (Fig. 3). This csu operon has been previously suggested to be involved in the adherence and formation of biofilm of A. baumannii on abiotic surfaces, but not human respiratory cells55. In addition, our transcriptome analysis also showed that two of the annotated type IV pili gene clusters in the A. baumannii strain were upregulated specifically when co-cultured with C. jeikeium. Type IV pili play a role in natural transformation, twitching motility, and biofilm formation56. Our results showed that C. jeikeium modifies type I and type IV pili expression of A. baumannii, which may be a mechanism to interfere with biofilm formation and surface attachment of the competitor species, in this case A. baumannii.

Figure 3.

Regulation of A. baumannii type I and type IV pili gene cluster expression when co-cultured with individual pathogen/commensal species. K. pneumoniae (KP), A. baumannii (AB), E. hormaechei (EH), L. reuteri (LR), S. epidermidis (SE) and C. jeikeium (CJ). Differentially regulated genes shown with edgeR false discovery rate (FDR): <0.05 (red circle) and <0.1 (yellow circle). Log2 fold change values of gene expression was shown as red (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated) bar graphs with reference to monocultures. Bar scale from −4 to 4. Averaged gene expression level across control and treatment experiments (log2 read counts per million, log2CPM) was shown as green bar graphs. Bar scale from 0 to 15.

Confirmation of gene expression by qPCR

RNA-Seq gene expression results were validated by performing qPCR for a select group of differentially expressed genes. Genes were chosen for analysis based on the ability to design unique primers and their reported fold change values. Biological replicates were tested and qPCR was performed on cDNA from reverse transcription of total RNA. For K. pneumoniae, 2 downregulated (acnB, T643_RS19850; gabT_2, T643_RS11485) and 3 upregulated (aminotransferase, T643_RS18930; cimH, T643_RS19470; PTS system fructose IIA component, T643_RS18905) genes were tested. For A. baumannii, 3 downregulated (papD, T634_RS02055; mmsA_1, T634_RS14320; EamA-like transporter, T634_RS10710) and 4 upregulated (pilN, T634_RS16475; NAD family protein, T634_RS01410; Hpt domain protein, T634_RS11200; hypothetical protein, T634_RS08500) genes were tested. Gene expression was normalized to gyrB (T634_RS06810, T643_RS05975) and relative expression ratios were determined by comparing co-culture samples with monoculture samples. Relative expression ratios were converted to log2FC and compared to the log2FC from RNA-Seq data. All genes tested showed the same direction of log2FC in both RNA-Seq and qPCR analysis (Supplementary Fig. S5), confirming the trends observed in the RNA-Seq analysis.

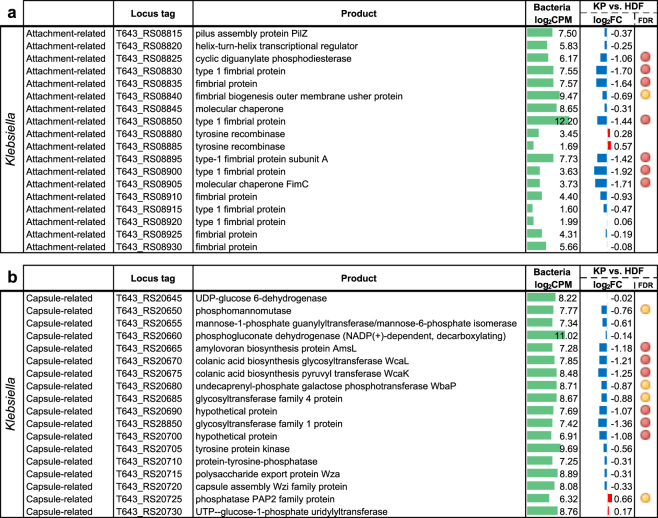

Bacterial responses to human fibroblast co-culture assays

To assess host interactions, each of the three selected MDROs for this study was also individually co-cultured with adult human fibroblast cells (HDF). Our transcriptome analysis using RNA-Seq showed that two gene clusters in K. pneumoniae were specifically down-regulated when co-cultured with HDF cells. The down-regulated K. pneumoniae gene clusters were involved in fimbriae production and capsule synthesis and showed a strong reduction of up to 3.8-fold (log2 fold change of −1.92) in both gene loci (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Expression of K. pneumoniae (a) attachment-related and (b) capsule-related gene clusters in response to co-cultured HDF cells. Differentially regulated genes shown with edgeR false discovery rate (FDR): <0.05 (red circle) and <0.1 (yellow circle). Log2 fold change values of gene expression was shown as red (up-regulated) and blue (down-regulated) bar graphs with reference to monocultures. Bar scale from −4 to 4. Averaged gene expression level across control and treatment experiments (log2 read counts per million, log2CPM) was shown as green bar graphs. Bar scale from 0 to 15.

Down-regulation of bacterial surface antigen is likely a fitness strategy to cope with the constantly changing host environment. Evrard et al.57 showed that the capsule-deficient mutant of a K. pneumoniae clinical isolate could be more efficiently internalized by dendritic cells than its wild-type counterpart. It was suggested that the presence of a thick capsule at the surface of K. pneumoniae may interfere with binding and internalization by host cells. Similarly, in uropathogenic E. coli, King et al.58 reported that the capsule gene expression are spatially and temporally regulated during different phases of infection such that the unencapsulated cells in the population can preferentially adhere to and invade bladder epithelial cells, and only produce capsule once internalized for intracellular survival and spread. Our results further support these previous studies that expression of bacterial surface antigens are possibly regulated in response to interactions with host cells to evade host immune responses.

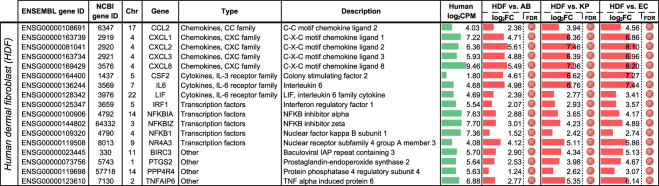

Host responses to MDRO co-culture

With the same set of co-cultured assays in which MDROs were individually co-cultured with mammalian human fibroblast cells, we also measured human host gene responses. Analysis of HDF-derived human RNA-Seq reads revealed a set of 17 human genes that were significantly up-regulated across all three MDRO-fibroblast co-culture assays (Fig. 5). The up-regulated gene set included chemokines, cytokines, and transcription factors that were up-regulated from 2.36 (log2 fold change of 1.24) to 294-fold (log2 fold change of 8.2) across the three MDROs. Pathway and GO term enrichment analyses of the gene set were performed using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (https://david.ncifcrf.gov)59,60. The top 5 enriched KEGG pathways and biological process GO terms were shown in Supplementary Table S8. The gene set was enriched in inflammatory and immune response functions. A total of 11 out of the 17 genes could be mapped to the Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) signaling pathway in KEGG (Supplementary Fig. S6)61–63. TNF is involved in the regulation of apoptosis, cell survival, and inflammation and immunity.

Figure 5.

Human host genes were upregulated when HDF cells were co-cultured with MDROs. Differentially regulated genes shown with edgeR false discovery rate (FDR): <0.05 (red circle). Log2 fold change values of human gene expression was shown as red (up-regulated) bar graphs with reference to monocultures of HDF cells. Bar scale from 0 to 9. Averaged gene expression level across control and treatment experiments (log2 read counts per million, log2CPM) was shown as green bar graphs. Bar scale from 0 to 15.

Conclusion

In summary, we performed pairwise co-culture experiments of three selected high-priority military MDROs individually with each other, commensal and probiotic microbes, and cultured human cells. We monitored transcriptome responses of both the target and co-cultured pathogen/commensal species using RNA-Seq. Our goal was to delineate gene responses associated with virulence, survival mechanisms, and AMR in the MDROs with partners likely found in combat wound infections and potential probiotic scenarios rather than monoculture conditions.

Using this co-culturing approach, we observed differentially regulated gene responses associated with siderophore production, pili formation, and cell attachment. Our results suggested that a mixed microbial population may modulate the virulence and colonization of host cells. Future experiments are needed to determine the biological signals involved in the regulation of these important survival and virulence mechanisms of MDROs for effective drug targeting.

Our approach leveraged bacteria-bacteria and bacteria-host in vitro co-culture to observe differential transcriptional regulation using RNA-Seq analysis. This study highlights the diverse stimuli an organism may encounter in different environmental niches, and the complex gene regulation that takes place to achieve optimal survival and fitness. This type of analysis will be critical to understanding the interactions among the microbial pathogens, the host microbiome and the host environment, particularly in disease conditions. Our results provide foundational data and insight into the possibility of manipulating the local microbiome or avoiding ‘collateral-damage’ by minimizing exposure to overly broad-spectrum antibiotics or vancomycin, which kills skin commensals, when treating complicated polymicrobial wound, intra-abdominal, or respiratory infections.

Methods

Genome Sequencing

The genomes of the MDRO isolates were sequenced at JCVI by Illumina HiSeq (2 × 100 bp). Briefly, paired-end libraries were constructed for each sequencing technology from randomly nebulized genomic DNA in the 300–800 bp size range following manufacturer recommendations. Sequence reads were generated with a target average read depth of ~60-fold coverage.

Draft Genome Assembly

To integrate the JCVI Illumina HiSeq data with data generated through various sequencing platforms and OpGen optical restriction maps generated by WRAIR, an Automated Gap Closure pipeline that combined de novo assembly followed by reference-guided gap closure to resolve short and uncomplicated gaps was implemented as described previously50.

Genome annotation

Contigs were annotated for protein- and RNA-encoding features using the JCVI automated annotation pipeline essentially as described previously50. Genes conferring drug resistance were identified using the RGI (Resistance Gene Identifier, Version 2) tool in strict mode against the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD)51–53.

Bacterial strains, growth conditions and bacterial co-culture experiments

MDROs A. baumannii MRSN 7339, K. pneumoniae MRSN 1319, and E. hormaechei MRSN 11489 were selected by WRAIR MRSN based on having the highest degree of clinical importance as described earlier in the results section and identified by standard automated biochemical analysis as described previously64. The selection criteria and antibiotic resistance profile of the three MDROs against 20 antibiotics were shown in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, respectively. WRAIR MRSN provided purified genomic DNA and culture stocks of these MDROs. The Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) of the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command determined that this study was research not involving human subjects, as it did not “involve living individuals about whom an investigator conducting research obtains (1) data through intervention or interaction with the individual, or (2) identifiable private information, in accordance with 32 CFR 219.102(f).” Likewise, the JCVI IRB determined that the use of MDROs from MRSN was exempt from IRB review because the material provided was pre-existing and de-identified.

The commensal bacteria Lactobacillus reuteri SD2112 (ATCC 55730), Staphylococcus epidermidis SK135 (BEI HM-118), and C. jeikeium NCTC 11913 (ATCC 43734) were obtained from ATCC/BEI Resources, and therefore exempt from IRB review at JCVI since they are publicly available and de-identified from any human source. A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, E. hormaechei, and S. epidermidis were grown in BHI broth (BD) to a concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/ml in log phase growth. C. jeikeium and L. reuteri were grown to the same target concentrations in BHI supplemented with 1% (vol/vol) Tween-80 (Fisher) and MRS broth (BD), respectively. For co-culture assays, equal amounts of cells from the cultures were combined and shaken at 37 °C for 5 min at 200 RPM. 1 × 107 CFU of each co-culture were plated onto a BHI agar plate in triplicates. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 6 hours, at which point approximately 1 × 108 CFU from each triplicate plate were combined and treated with RNAprotect bacteria reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Bacterial cells were spun down and the RNAprotect bacterial reagent removed after treatment. Cell pellets were stored at −80 °C until RNA extraction. Growth inhibition of S. epidermidis by E. hormaechei was analyzed by quantifying colony forming units (CFUs) on phenylethyl alcohol and Hektoen Enteric selective agar media65,66. The same experiment was performed using independent cultures on different days for biological replicates to control for reproducibility.

Human dermal fibroblast growth conditions and co-culture experiments

Adult human dermal fibroblast (HDF) cells (Cat. no. C-013-5C) were obtained from Invitrogen and their experimental use in this study was found to be exempt from IRB review by the JCVI IRB because these cells are publicly available and de-identified. HDF cultures were set up to test multiplicity of infection (MOI) and incubation times for individual MDROs. The MOIs for all three MDROs with HDF cells was determined to be optimal at 100:1 (MDRO:HDF). The optimal duration of a bacterial-HDF co-culture assay was determined to be one hour. Prolonged co-culture times resulted in acidification of the cell culture media, which was avoided to eliminate interference with gene expression due to pH changes.

Multiple control experiments to determine retention of bacteria to HDF cells were performed and bacteria were observed via light microscopy to be adherent to the HDF cells, even after 3 rinses with PBS (data not shown). Cells (including MDRO bacteria and HDF cells) were isolated for RNA extraction from the co-culture assays after removing excess culture media so only adherent/close proximity bacterial cells were harvested. Cells were then treated with RNAprotect Cell Reagent (Qiagen) to immediately stabilize RNA transcripts before further processing.

RNA isolation

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). The manufacturer’s protocol was followed with additional steps as described below. Enzymatic lysis was performed on cell pellets resuspended in TE with 15 mg/ml lysozyme (Fisher) and 3 mg/ml Proteinase K (NEB) and incubated for 10 min at room temperature with vortexing for 10 s every 2 min. After enzymatic lysis, mechanical lysis was performed by adding buffer RLT with 1% vol/vol 2-mercaptoethanol and transferring the lysate to a Lysis Matrix B bead beating tube (MP Bio). Samples were homogenized for 45 s at 6.5 m/s on a FastPrep120 Cell Disrupter system. On-column DNAse treatment (Qiagen) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated RNA was treated with TURBO DNase (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

RNA-Seq library preparation for Illumina sequencing

Enrichment for mRNA was done using the RiboZero rRNA Removal Kit for bacteria (Epicentre). Libraries were constructed from 10 ng of mRNA using the NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Libraries were normalized and pooled for sequencing using qPCR (Kapa Biosystems Library Quantification Kit). The resulting pooled libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform (2 × 100 bp).

RNA-Seq data analysis

Illumina sequencing reads in FASTQ format were analyzed using CLC Genomics Workbench version 6.5 (http://www.clcbio.com) after removing low quality reads (CLC quality score limit = 0.05, maximum of 2 ambiguities), reads less than 50 bp, and adaptors. To remove rRNA reads, a set of known 4,692 distinct rRNA sequences were collected from the SILVA database (http://www.arb-silva.de/) for all five species of bacteria used in the co-culture assays. All reads mapped to the known rRNA sequences were discarded. BWA67 was used for the mapping allowing up to three mismatches. Reference files for RNA-Seq analysis were prepared from Genbank files imported into CLC. For each pair of control and co-culture experiment, the expected genomes were selected and reads were mapped using the following settings: maximum number of mismatches = 2, minimum length fraction = 0.8, minimum similarity fraction = 0.98, maximum number of hits for a read = 10, minimum and maximum distances for paired reads = 1,1000 and counting scheme of “include broken pairs”. All reads mapped to each gene were used as raw read count to determine up or down-regulated genes using the Bioconductor package edgeR68. Genes with at least 1 CPM in at least 2 samples were included for the differential expression analysis. Differentially expressed genes were determined using an exact test implemented for negative-binomially distributed counts with estimated genewise dispersion values using edgeR. The RNA-Seq gene expression for the three MDROs A. baumannii, K. pneumoniae, and E. hormaechei, together with curated virulence gene annotation and AMR annotation are shown in Supplementary Tables S4–S6.

Reverse Transcription and qRT-PCR

Reverse transcription (RT) was performed to generate cDNA from two biological replicates to be used in qRT-PCR for the validation of RNA-Seq data. RNA concentrations were determined with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and 1.5 μg of total RNA was used in each reaction. RNA was incubated with 6 μg of random hexamers (Invitrogen) and 40 U of RNaseOUT (Invitrogen) in 18.5 μl at 70 °C for 10 min, followed by snap cooling on ice. The reaction was set up with 1 × First Strand Buffer, 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen), and 400 U SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) in 30 μl. The reaction was incubated in a 42 °C water bath for 16 h. The reaction was stopped and RNA was hydrolyzed with 0.1 M EDTA and 0.2 M NaOH at 65 °C for 12 min. Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) was added to neutralize the pH. Purification of cDNA was achieved by using QIAquick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol and quantitated by fluorometric assays using SYBR Gold (Invitrogen).

qRT-PCRs were performed with 10 ng of template cDNA in 10 μl triplicate reactions with SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche) in 384-well plates on the LightCycler480 qPCR instrument (Roche). Cycling conditions were 95 °C for 10 min followed by 50 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 15 s. A melting curve analysis was performed after all cycles were completed to verify the Tm of amplified products. No-RT controls and qPCR control reactions were performed as well. To determine the CP value (crossing point-PCR-cycle or threshold cycle) for each reaction, the ‘Fit Point Method’ was performed in the LightCycler480 software 1.5.0 (Roche Diagnostics). Efficiency for each primer was optimized by adjusting primer concentration and was determined for the reaction conditions. Efficiency and CP values were used to calculate the gene expression with normalization to gyrB. Relative expression ratios were determined by comparing co-culture samples with monoculture samples using the method described previously69. Primer sequences and concentrations used are provided in Supplementary Table S9.

Data availability

Genome assembly and annotation for the three selected MDRO isolates are available under NCBI bioprojects: PRJNA223624, PRJNA223615 and PRJNA223617. RNA-Seq datasets for the co-culture assays are available at the NCBI SRA under bioprojects: PRJNA292770, PRJNA292776, PRJNA292777, PRJNA294773, PRJNA294780, PRJNA294781 and PRJNA314266.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The opinions and assertions herein are solely those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or representing those of the US Army or Department of Defense. This project was funded in whole or part with federal funds from the Department of Defense, Defense Medical Research and Development Program - Military Infectious Diseases Basic Research Award number W81XWH-12-2-0106 to D.E.F. and A.P.C. and from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services under award number U19AI110819.

Author Contributions

D.E.F. and A.P.C. conceived and designed the study, E.P.L. and M.K.H. selected and provided the military MDRO isolates, M.K. performed genome assembly, J.D. and R.K. conducted wet lab experiments, Y.C., A.P.C., L.M.B. and D.E.F. analyzed the results. A.P.C., Y.C., R.K., J.D., L.M.B., E.B.L. and D.E.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Agnes P. Chan and Yongwook Choi contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-26738-1.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Agnes P. Chan, Email: achan@jcvi.org

Derrick E. Fouts, Email: dfouts@jcvi.org

References

- 1.Magiorakos A-P, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boucher HW, et al. Bad bugs, no drugs: no ESKAPE! An update from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48:1–12. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013 | Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance | CDC. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html.

- 4.WHO | Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014 (2016).

- 5.Spellberg B, Bonomo RA. Editorial Commentary: Ceftazidime-Avibactam and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: ‘We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat’. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:1619–1621. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauser AR, Mecsas J, Moir DT. Beyond Antibiotics: New Therapeutic Approaches for Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63:89–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tse BN, et al. Challenges and Opportunities of Nontraditional Approaches to Treating Bacterial Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017;65:495–500. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kalan, L. et al. Redefining the Chronic-Wound Microbiome: Fungal Communities Are Prevalent, Dynamic, and Associated with Delayed Healing. MBio7 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Dickson RP, Huffnagle GB. The Lung Microbiome: New Principles for Respiratory Bacteriology in Health and Disease. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004923. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenzel RP, Edmond MB. Antibiotics for abdominal sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;372:2062–2063. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1503936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell. 2007;128:1037–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yigit H, et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:1151–1161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.4.1151-1161.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Hoek AHAM, et al. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes: an overview. Front. Microbiol. 2011;2:203. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford, P. A. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 933–51, table of contents (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Springer B, et al. Mechanisms of streptomycin resistance: selection of mutations in the 16S rRNA gene conferring resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001;45:2877–2884. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.10.2877-2884.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacoby GA. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005;41(Suppl 2):S120–6. doi: 10.1086/428052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sykes RB, Richmond MH. R factors, beta-lactamase, and carbenicillin-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Lancet. 1971;2:342–344. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(71)90060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wozniak RAF, et al. Comparative ICE genomics: insights into the evolution of the SXT/R391 family of ICEs. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bissonnette L, Roy PH. Characterization of In0 of Pseudomonas aeruginosa plasmid pVS1, an ancestor of integrons of multiresistance plasmids and transposons of gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1992;174:1248–1257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1248-1257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fournier P-E, et al. Comparative genomics of multidrug resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouts DE, et al. Sequencing Bacillus anthracis typing phages gamma and cherry reveals a common ancestry. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:3402–3408. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.9.3402-3408.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garbeva P, Silby MW, Raaijmakers JM, Levy SB, Boer W. de. Transcriptional and antagonistic responses of Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1 to phylogenetically different bacterial competitors. ISME J. 2011;5:973–985. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwarz S, et al. Burkholderia type VI secretion systems have distinct roles in eukaryotic and bacterial cell interactions. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001068. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simionato MR, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis genes involved in community development with Streptococcus gordonii. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:6419–6428. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00639-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman LR, et al. Selection for Staphylococcus aureus small-colony variants due to growth in the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:19890–19895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mela F, et al. Dual transcriptional profiling of a bacterial/fungal confrontation: Collimonas fungivorans versus Aspergillus niger. ISME J. 2011;5:1494–1504. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreth J, Merritt J, Shi W, Qi F. Competition and coexistence between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis in the dental biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7193–7203. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7193-7203.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Straight PD, Willey JM, Kolter R. Interactions between Streptomyces coelicolor and Bacillus subtilis: Role of surfactants in raising aerial structures. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188:4918–4925. doi: 10.1128/JB.00162-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piddock LJV. Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps - not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2006;4:629–636. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nizet V. Antimicrobial peptide resistance mechanisms of human bacterial pathogens. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2006;8:11–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El Garch F, et al. Fluoroquinolones induce the expression of patA and patB, which encode ABC efflux pumps in Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010;65:2076–2082. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mammina C, et al. Co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii in intensive care unit patients. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;45:629–634. doi: 10.3109/00365548.2013.782614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marchaim D, et al. ‘Swimming in resistance’: Co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2012;40:830–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peleg AY, et al. Prokaryote-eukaryote interactions identified by using Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14585–14590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805048105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandlik A, et al. RNA-Seq-based monitoring of infection-linked changes in Vibrio cholerae gene expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphrys MS, et al. Simultaneous transcriptional profiling of bacteria and their host cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e80597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filkins LM, et al. Coculture of Staphylococcus aureus with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Drives S. aureus towards Fermentative Metabolism and Reduced Viability in a Cystic Fibrosis Model. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:2252–2264. doi: 10.1128/JB.00059-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.González-Torres P, et al. Interactions between closely related bacterial strains are revealed by deep transcriptome sequencing. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015;81:8445–8456. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02690-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grice EA, et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011;9:244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spinler JK, et al. From prediction to function using evolutionary genomics: human-specific ecotypes of Lactobacillus reuteri have diverse probiotic functions. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014;6:1772–1789. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prince T, McBain AJ, O’Neill CA. Lactobacillus reuteri protects epidermal keratinocytes from Staphylococcus aureus-induced cell death by competitive exclusion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:5119–5126. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00595-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fouts DE, et al. Major structural differences and novel potential virulence mechanisms from the genomes of multiple campylobacter species. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: serotype conversion and virulence. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:294. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gill SR, et al. Insights on evolution of virulence and resistance from the complete genome analysis of an early methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain and a biofilm-producing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis strain. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:2426–2438. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2426-2438.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rasko DA, et al. The genome sequence of Bacillus cereus ATCC 10987 reveals metabolic adaptations and a large plasmid related to Bacillus anthracis pXO1. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:977–988. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jacobsen A, Hendriksen RS, Aaresturp FM, Ussery DW, Friis C. The Salmonella enterica pan-genome. Microb. Ecol. 2011;62:487–504. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9880-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodriguez-Valera F, Ussery DW. Is the pan-genome also a pan-selectome? F1000Res. 2012;1:16. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.1-16.v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan AP, et al. A novel method of consensus pan-chromosome assembly and large-scale comparative analysis reveal the highly flexible pan-genome of Acinetobacter baumannii. Genome Biol. 2015;16:143. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McArthur AG, et al. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jia B, et al. CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McArthur AG, Wright GD. Bioinformatics of antimicrobial resistance in the age of molecular epidemiology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015;27:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Evans BA, Amyes SGB. OXA β-lactamases. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014;27:241–263. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00117-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Breij A, et al. CsuA/BABCDE-dependent pili are not involved in the adherence of Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC19606(T) to human airway epithelial cells and their inflammatory response. Res. Microbiol. 2009;160:213–218. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harding, C. M. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii strain M2 produces type IV pili which play a role in natural transformation and twitching motility but not surface-associated motility. MBio4, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Evrard B, et al. Roles of capsule and lipopolysaccharide O antigen in interactions of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:210–219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00864-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King JE, Aal Owaif HA, Jia J, Roberts IS. Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Expression of the K1 Polysaccharide Capsule of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli and Downregulation of the Capsule Genes during Growth in Urine. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:2605–2613. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00188-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D457–62. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scott P, et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex infection in the US military health care system associated with military operations in Iraq. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2007;44:1577–1584. doi: 10.1086/518170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lilley BD, Brewer JH. The selective antibacterial action of phenylethyl alcohol. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1953;42:6–8. doi: 10.1002/jps.3030420103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.King S, Metzger WI. A new plating medium for the isolation of enteric pathogens. I. hektoen enteric agar. Appl. Microbiol. 1968;16:577–578. doi: 10.1128/am.16.4.577-578.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth G. K. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Genome assembly and annotation for the three selected MDRO isolates are available under NCBI bioprojects: PRJNA223624, PRJNA223615 and PRJNA223617. RNA-Seq datasets for the co-culture assays are available at the NCBI SRA under bioprojects: PRJNA292770, PRJNA292776, PRJNA292777, PRJNA294773, PRJNA294780, PRJNA294781 and PRJNA314266.