Abstract

From life science to material science, to pharmaceutical industry, and to food chemistry, polysulfides are vital structural scaffolds. However, there are limited synthetic methods for unsymmetrical polysulfides. Conventional strategies entail two pre-sulfurated cross-coupling substrates, R–S, with higher chances of side reactions due to the characteristic of sulfur. Herein, a library of broad-spectrum polysulfurating reagents, R–S–S–OMe, are designed and scalably synthesized, to which the R–S–S source can be directly introduced for late-stage modifications of biomolecules, natural products, and pharmaceuticals. Based on the hard and soft acids and bases principle, selective activation of sulfur-oxygen bond has been accomplished via utilizing proton and boride for efficient unsymmetrical polysulfuration. These polysulfurating reagents are highlighted with their outstanding multifunctional gram-scale transformations with various nucleophiles under mild conditions. A diversity of polysulfurated biomolecules, such as SS−(+)-δ-tocopherol, SS-sulfanilamide, SS-saccharides, SS-amino acids, and SSS-oligopeptides have been established for drug discovery and development.

Synthetic methods to access unsymmetrical polysulfides are limited despite their high biological relevance. Here, the authors disclose a polysulfurating reagent affording unsymmetrical di- and tri-sulfides under mild conditions, and suitable for late-stage modification of natural products.

Introduction

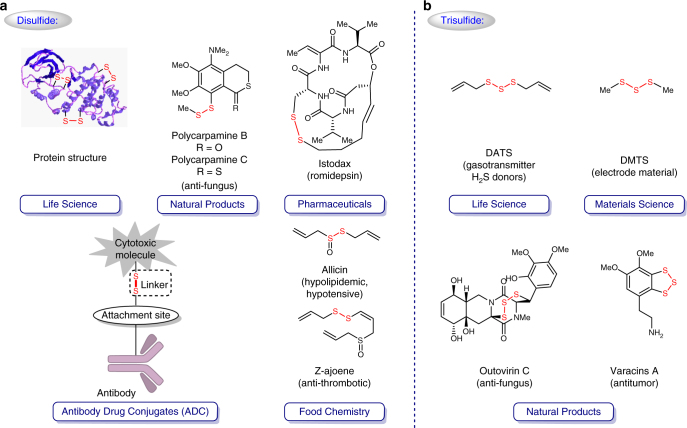

Disulfide scaffolds, containing two covalently linked sulfur atoms, are important molecular motifs in life science1–6, pharmaceutical science7–15, and food chemistry16–18 by virtue of their unique pharmacological and physiochemical properties (Fig. 1a). Disulfide bonds, for instance, in biomolecules take multifaceted roles in various biochemical redox processes to generate and regulate hormones, enzymes, growth factors, toxins, and immunoglobulins for very homeostasis and bio-signaling (e.g., metal trafficking); secondary and tertiary structures of proteins are also well formed and stabilized via the disulfide bridge2–5. In recent decades, potent bioactive natural products and pharmaceuticals possessing sulfur–sulfur bonds have been discovered, such as the antifungal polycarpamine family7, the anti-poliovirus epidithiodiketopiperazine (ETPs) family8, 9, romidepsin10, gliotoxin11, and some new histone deacetylase/methyltransferase inhibitors12, which, mechanism-wise, either sequester enzyme-cofactor zinc or generate highly reactive electrophiles to induce DNA strand scission. When it comes to antibody-drug conjugates (ADC), the disulfide bond has also been extensively utilized as a linker to deliver the active drug into the targeted cell after cleavage upon internalization of ADC19–22. Due to the higher intracellular concentration of free thiols (glutathione) than in the bloodstream, the sulfur–sulfur bonds can be selectively cleaved in the cytoplasm of cancer cell, thereby achieving the specified release of cytotoxic molecules. Notably, disulfide compounds in allium species plants can not only demonstrate vasorelaxation activity, but also inhibit ADP-induced platelet aggregation16–18.

Fig. 1.

Significant polysulfides. a The importance of disulfide scaffolds in life science, natural products, pharmaceuticals, antibody drug conjugates, and food chemistry. b Functional trisulfide molecules

Tri-sulfides have recently received considerable attention. To cite the allium-derived diallyl trisulfide (DATS) as an example, it serves as a gasotransmitter precursor and an excellent hydrogen sulfide donor, mediating and regulating the release of hydrogen sulfide upon physiological activation (Fig. 1b)23, 24. From the materials perspective, organotrisulfides, such as dimethyl trisulfide (DMTS) with a theoretical capacity of 849 mAhg−1, hold promise as high-capacity cathode materials for high-energy rechargeable lithium batteries25. It should also be pointed out that trisulfides do exist in bioactive natural products from marine invertebrates7, 26–28, such as the antitumor varacins A26 and the anti-fungus outovirin C27.

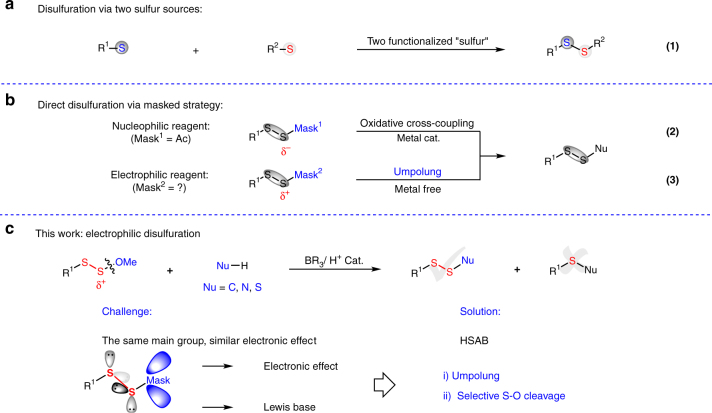

Given the importance and predominance in pharmaceuticals and other bioactive compounds of polysulfurated structures, it is always sought-after to develop general polysulfuration protocols for synthetic purposes. Although typical methods for symmetrical disulfide preparation have been well developed29, the construction of unsymmetrical disulfides is still a challenging transformation due to the high reactivity of S–S bond30–40. In general, the synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides can be achieved via an SN2 process between a thiol and a prefunctionalized thiol with leaving group32–38. Alternatively, one can employ either two different kinds of thiols with unavoidable formation of homocoupling byproducts39 or two distinct symmetrical disulfides with the use of rhodium(I) by Yamaguchi group40. Based on our continuous research in organic sulfur chemistry41–48, comproportionation between two distinct inorganic sulfur sources was utilized for unsymmetrical disulfides syntheses49. However, the strategy of aforementioned methods introduces disulfide bonds from two different kinds of sulfur-containing substrates, requiring more synthetic steps and leading to side-reactions due to both reactive thio-derivatives (Fig. 2a)30–40, 49. We intend to develop methodology which can introduce the RSS source with one disulfurating reagent at a later stage so as to provide great compatibility and several possibilities of polysulfuration. Hydropersulfide (RSSH) seems to be a prime disulfurating reagent, though it is unstable owing to its high reactivity50, 51. Two sulfur atoms were successfully introduced in one step via oxidative cross-couplings of acetyl masked disulfurating nucleophiles and organometallic reagents (Fig. 2b)52.

Fig. 2.

Strategies for polysulfide construction. a Traditional methodologies for unsymmetrical disulfide syntheses. b Masked strategy for disulfuration. c Electropilic disulfurating reagent for polysulfuration

Nevertheless, there is a large demand for a universal disulfurating reagent, which is compatible with diverse coupling partners without transition-metal catalysis. The umpolung strategy, replacement of acetyl (RSS−) with methoxyl (RSS+) group, will afford the precursor of persulfide cation (Fig. 2c). Originating from the same main group, sulfur and oxygen possess similar electronic effect, which imposes a great challenge for selective cleavage of S–O bond with S–S bond untouched. Based on the hard and soft acids and bases (HSAB) principle53, we hypothesize that boride/proton can help to make the difference between S–S and S–O, in which the hard acid boride/proton prefers oxygen coordination. Herein, we disclose a polysulfurating reagent which can construct unsymmetrical disulfide and trisulfide products by utilizing a RSS source only on one substrate, which renders the late-stage functionalization feasible. Different nucleophilic regents, such as 1,3-dicarbonyl derivatives, electron-rich arenes, heteroarenes, amines, and thiols, had been smoothly coupled with disulfurating reagents under mild, transition-metal-free, and base-free conditions, especially suitable for the late-stage modification of natural products and pharmaceuticals.

Results

Optimization and synthesis of polysulfurating reagents

Initial studies commenced with the construction of designed electrophilic polysulfurating reagents. It was hypothesized that the electrophilic reagent could be obtained through hydropersulfide anion and methanol via oxidative cross-coupling. The polysulfurating reagent 2d was obtained in 31% yield under the conditions of copper(II) as catalyst, 2,2′-bipyridine as ligand, and PhI(OAc)2 as oxidant (Table 1, entry 1). The bulky iodonium salt PhI(OPiv)2 was the oxidant of choice in this conversion (Table 1, entries 1–3). Systematic investigations of ligands showed that 4,7-diphenyl-1,10-phenanthroline helped to increase the yield of 2d to 77% (Table 1, entries 3–5). Further study demonstrated that slightly lower temperature was important for keeping product 2d stable in this system (Table 1, entry 6). Catalyst loading was lowered with the same efficiency of the transformation (Table 1, entries 7–9). The optimal conditions were found to involve treatment of 1d with 5 mol% of catalyst, 10 mol% of ligand L1, 2.2 equivalents of bis(tert-butylcarbonyloxy)iodobenzene, and 1.0 equivalent of lithium carbonate in 0.1 M methanol at 20 °C, which afforded electrophilic polysulfurating reagent 2d in the yield of 88% (Table 1, entry 10). When the oxidant bis(tert-butylcarbonyloxy)iodobenzene was reduced to 1.9 equivalents, the yield of 2d was dropped sharply to 65% (Table 1, entry 11).

Table 1.

Optimization of polysulfide reagentsa,b

|

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | CuSO4 (mol%) | Ligand (mol%) | PhI(OPiv)2 (equiv) | Temp (°C) | Time (h) | Yields (%) |

| 1c | 10 | bpy (10) | 2.5 | 25 | 11 | 31 |

| 2d | 10 | bpy (10) | 2.5 | 25 | 11 | ND |

| 3 | 10 | bpy/ phen (10) | 2.5 | 25 | 11 | 50/53 |

| 4 | 10 | L1 (10) | 2.5 | 25 | 11 | 77 |

| 5 | 10 | L2/L3/L4 (10) | 2.5 | 25 | 11 | 70/63/68 |

| 6 | 10 | L1 (10) | 2.5 | 20 | 13 | 86 |

| 7 | 5 | L1 (10) | 2.5 | 20 | 13 | 86 |

| 8 | 2.5 | L1 (10) | 2.5 | 20 | 13 | 79 |

| 9 | 5 | L1 (5) | 2.5 | 20 | 13 | 76 |

| 10 | 5 | L1 (10) | 2.2 | 20 | 13 | 88 |

| 11 | 5 | L1 (10) | 1.9 | 20 | 13 | 65 |

|

| ||||||

aConditions: 1d (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), CuSO4·5H2O, Ligand, Li2CO3 and PhI(OPiv)2 were added to MeOH (2 mL) at 20 °C for 13 h

bIsolated yields

cPhI(OAc)2 was instead of PhI(OPiv)2

dPhI(OTFA)2 was instead of PhI(OPiv)2

With the optimized conditions in hand, the syntheses of electrophilic polysulfurating reagents were comprehensively investigated. A scale of 5 mmol operation was practicably performed, decreasing catalyst loading to 0.25 mol% (for details see the Supplementary Table 2). Various acetyl substituted disulfides were readily transformed to methoxyl substituted disulfides (Table. 2). Initially, the reagents bearing both electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on aromatic rings were successfully obtained (Table 2, 2a–2f). Notably, 1.84 g of 2d was achieved in a yield of 87% with 10 mmol scale operation (Table 2, 2d). The arene substituted with chloromethylene group was compatible under the standard conditions (Table 2, 2e–2f). Reactions involving secondary benzyl and propargyl derivatives were carried out smoothly (Table 2, 2g–2h). When aliphatic substrates were evaluated, the corresponding products were formed efficiently (Table 2, 2i–2m). The scope was further demonstrated through the successful syntheses of bis-disulfurating reagents (Table 2, 2n–2o). Notably, the modification of saccharides and amino acids were also converted into corresponding disulfurating reagents (Table 2, 2p–2t). These reagents are fairly stable without deterioration when stored in a refrigerator (−18 °C) for half a year. Around 20% of these reagents will decompose at room temperature (+25 °C) after 1 week.

Table 2.

The scope of polysulfurating reagentsa,b

|

a1 (5 mmol, 1 equiv), CuSO4·5H2O (0.0125 mol, 0.125 mol%), L1 (0.025 mol, 0.25 mol%), Li2CO3 (5 mmol, 1 equiv) and PhI(OPiv)2 (11 mmol, 2.2 equiv) were added to MeOH (10 mL) at 20 °C for 15 h

bIsolated yields

c1 (10 mmol, 1 equiv) and MeOH (10 mL) were used

Polysulfuration with designed reagents

With the class of disulfurating reagents in hand, the construction of unsymmetrical disulfides and trisulfides was consequently explored. We initiated our efforts with 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds due to their excellent nucleophilic property. Based on the HSAB principle, the coupling between acetylacetone and reagent 2d has been explored under the assistance of the hard acid Tris(perfluorophenyl)borane as a catalyst (for details see the Supplementary Table 3). Various 1,3-dicarbonyl structures effectively afford disulfuration catalyzed with the combination of tris(perfluorophenyl)borane and 4-methoxypyridine (Table 3). Acyclic and cyclic 1,3-dicarbonyl substrates were smoothly converted to the desired disulfides (Table 3, 3a–3d). The configuration of 3a was further confirmed through X-ray crystallographic analysis. Aliphatic and propargyl derivatives were compatible in this process (Table 3, 3e–3h). Significantly, disulfurating reagents bearing both saccharide and amino acid groups accomplished this transformation efficiently with two parts connected via the disulfur linkage (Table 3, 3i–3l).

Table 3.

Disulfuration with carbon nucleophiles a,b

|

aStandard conditions A: NuH (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equiv), 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), B(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%) and 4-MeOPy (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%) were added to DCE (0.25 mL) at r.t. for 22 h. Standard conditions B: NuH (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%) were added to PhMe (0.5 mL) at 0 °C for 24 h. Standard conditions C: NuH (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and MeSO3H (0.02 mmol, 10 mol%) were added to tAmylOH (0.5 mL) at 0 °C for 5–24 h

bIsolated yields

cr.t. was instead of 0 °C

dB(C6F5)3 (0.002 mmol, 1 mol%) was used

eB(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 0.2 mol%) was used

fB(C6F5)3 (0.004 mmol, 2 mol%) were added to PhMe (0.25 mL) at r.t. for 24 h

gNuH (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equiv), 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (0.004 mmol, 2 mol%) were added to PhMe (0.25 mL) at 0 °C for 24 h. Ar = 4-CNC6H4

Following the activation mode, electron-rich aromatics were readily accommodated under standard conditions (Table 3, 4a–4d). (+)-δ-Tocopherol, a significant bioactive molecule, could be disulfurated directly despite the presence of free hydroxyl group (Table 3, 4c–4d). Indole and pyrrole, ubiquitous in natural products and pharmaceuticals, are excellent coupling partners as well. Indoles bearing both electron-rich and -deficient functional groups proceeded smoothly with disulfurating reagents to afford the corresponding indolyl-disulfides on 3-position (Table 3, 5a-5p). A bis-disulfurating electrophile also afforded the corresponding twofold disulfur-containing molecule efficiently (Table 3, 5q). Saccharide and amino acid structures were directly installed with indoles via the disulfide linker (Table 3, 5r-5u). A gram-scale operation was performed with 5 mmol of 2d under the catalysis of 1 mol% of B(C6F5)3 affording 5o in 93% yield (1.38 g), which structure was further confirmed through X-ray analysis. In particular, iodo- and formyl-substituted indoles were also compatible in this transformation (Table 3, 5m-5n). Pyrroles substituted on different positions were treated to the disulfuration conditions, successfully providing desired products as well (Table 3, 5v-5y).

Subsequently, amine partners were systematically varied providing access to a wide range of functional aza-disulfide in the presence of 2.5 mol% of tris(perfluorophenyl)borane. The anilines substituted with electron-withdrawing and electron-donating functional groups afforded the desired aza-disulfides in moderate to excellent yields (Table 4, 6a-6f). The secondary amines proceeded in this transformation, affording corresponding products in favorable yields (Table 4, 6g-6h). Notably, allyl, propargyl and heteroaromatic amines were all efficiently transformed to the corresponding products (Table 4, 6i-6k). Sulfanilamides, as a significant type of antibiotic, could be modified with the designed persulfurating reagent in good to excellent yields (Table 4, 6m-6s). Lenalidomide, a myeloma drug, was installed with the disulfide under mild reaction conditions (Table 4, 6t). Furthermore, functional disulfurating electrophiles, modified with saccharide and amino acid groups, were furnished with the substituted disulfur amine linker (Table 4, 6u-6y). The structure of 6a was further confirmed by X-ray analysis. In order to validate the efficiency and practicability of this aza-disulfuration, 0.25 mol% catalyst loading was launched on a gram-scale reaction to afford 6a in 81% yield (1.1 g).

Table 4.

Disulfuration with heteroatomic nucleophiles a,b

|

aStandard conditions D: NuH (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equiv), 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (0.005 mmol, 2.5 mol%) were added to PhMe (0.5 mL) at r.t. for 24 h. Standard conditions E: NuH (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equiv) and 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv) were added to DCM (2.0 mL) at r.t. for 8 h

bIsolated yields

cB(C6F5)3 (0.0125 mmol, 0.25 mol%) was used

dCH3CN was used as solvent

eNuH (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), 2 (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv) and B(C6F5)3 (0.005 mmol, 2.5 mol%) were added to DMF at r.t. for 24 h

fB(C6F5)3 (2.5 mol%) was added at r.t. for 5 h

gB(C6F5)3 (2.5 mol%) and DCM (0.5 mL) was added

hB(C6F5)3 (2.5 mol%) and DMF (0.5 mL) was added

i24 h. Ar = 4-CNC6H4, R = (CH2)9Me

Trisulfuration was readily achieved with thiols as a nucleophile (Table 4, 7a-7q). Even sterically bulky aliphatic thiols, tert-butylthiol and 1-adamantanethiol, displayed excellent trisulfurations (Table 4, 7d, and 7l). The structure of 7d was further confirmed via X-ray analysis. A gram-scale production for 7g could be performed in 92% yield practically. Thiols substituted with vinyl, polyfluoroalkyl, silyl, and hydroxyl groups, and heterocycles were all tolerated in this transformation, being converted to the unsymmetrical trisulfides, respectively (Table 4, 7h-7k, and 7o). Even dithiols efficiently formed the corresponding twofold trisulfur-containing products in good yields (Table 4, 7s-7t). Aliphatic trisulfurations could be achieved in high yields (Table 4, 7u-7v). It should be noted that trisulfides containing saccharide and cysteine fragments were readily formed through these reagents (Table 4, 7r, 7w-7ac). Cysteine was successfully utilized for constructing trisulfur-containing amino acids and oligopeptides, which might provide another access for peptide drug discovery (Table 4, 7aa-7ac).

Discussion

In summary, a class of stable and broad-spectrum polysulfurating reagents with masked strategy has been designed and a general polysulfurating methodology has been established under mild conditions, which can directly introduce two sulfur atoms into functional molecules. The designed reagents were compatible with a considerable range of significant biomolecules, such as saccharides, amino acids, peptides and variety of heterocycles. This protocol showcases the wide utility of both carbon and nitrogen nucleophiles resulting in the functional disulfides. Furthermore, the trisulfuration provides a convenient and efficient method for sulfur-containing drug discovery. Further studies on modification of biomolecules and pharmaceuticals with these disulfurating reagents are still ongoing.

Methods

General methods

See Supplementary Methods for further details.

General procedure for syntheses of disulfurating reagents 2

To a Schlenk tube were added RSSAc 1 (5 mmol, 1 equivalent), CuSO4·5H2O (0.0125 mmol, 0.25 mol%, 3.2 mg), L1 (0.025 mmol, 0.5 mol%, 8.1 mg), Li2CO3 (5 mmol, 1 equivalent, 370 mg), PhI(OPiv)2 (11 mmol, 2.2 equivalents, 4.47 g) and undried MeOH (10 mL), the mixture was stirred at 20 °C under normal conditions for 15 h. Then the mixture was quenched by saturated NaHCO3 and extracted by DCM before the organic phase was concentrated under vacuum without adding silica gel. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

General procedure for syntheses of disulfides 3

To a Schlenk tube were added 1,3-dicarbonyl compound (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equivalents), B(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%, 5.2 mg), 4-MeO-pyridine (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%, 1.1 mg), RSSOMe 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and 1,2-dichloroethane (0.25 mL), the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 22 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

General procedure for syntheses of disulfides 4

To a Schlenk tube were added arene (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equivalents), B(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 5 mol%, 5.2 mg), RSSOMe 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and toluene (0.5 mL), the mixture was stirred at 0 °C or r.t. for 24–60 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

General procedure for syntheses of disulfides 5

Method A: To a Schlenk tube were added indole (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equivalents), MeSO3H (0.02 mmol, 10 mol%, 2 mg), RSSOMe 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and t-AmylOH (0.5 mL), the mixture was stirred at r.t. for 24 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product. Method B: To a Schlenk tube were added indole (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equivalents), B(C6F5)3 (0.004 mmol, 2 mol%, 2.1 mg), RSSOMe (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and toluene (0.25 mL), the mixture was stirred at 0 °C or r.t. for 24 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

General procedure for syntheses of aza-disulfides 6

To a Schlenk tube were added amine (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equivalents), B(C6F5)3 (0.01 mmol, 2.5 mol%, 2.6 mg), RSSOMe 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and toluene (0.5 mL), the mixture was stirred at 0 °C or r.t. for 24 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

General procedure for syntheses of trisulfides 7

To a Schlenk tube were added thiol (0.22 mmol, 1.1 equivalents), B(C6F5)3, RSSOMe 2 (0.2 mmol, 1 equivalent), and DCM (0.5 mL), the mixture was stirred at r.t. under N2 atmosphere for 5–8 h before it was concentrated under vacuum. Purification by column chromatography afforded the desired product.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1565934 (3a), 1565935(5o), 1565936 (6a) and 1565937 (7d). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for financial support provided by The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0200500), NSFC (21722202, 21672069, 21472050), Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation (141011), DFMEC (20130076110023), the program for Shanghai Rising Star (15QA1401800), Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning, and National Program for Support of Top-Notch Young Professionals.

Author contributions

X.J. conceived the idea and supervised the whole project. X.X. designed and carried out the experiments. J.X. contributed to part experiments. X.J. and X.X. discussed the results, contributed to writing the manuscript, and commented on the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-04306-5.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Narayan M, Welker E, Wedemeyer WJ, Scheraga HD. Oxidative folding of proteins. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:805–812. doi: 10.1021/ar000063m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.A.-Cebollada J, Kosuri P, R.-Pardo JA, Fernández JM. Direct observation of disulfide isomerization in a single protein. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:882–887. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wommack AJ, et al. Discovery and characterization of a disulfide-locked C2-symmetric defensin peptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:13494–13497. doi: 10.1021/ja505957w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Góngora-Benítez M, Tulla-Puche J, Albericio F. Multifaceted roles of disulfide bonds. Peptides as therapeutics. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:901–926. doi: 10.1021/cr400031z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu S, et al. Mapping native disulfide bonds at a proteome scale. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:329–331. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landeta C, et al. Compounds targeting disulfide bond forming enzyme DsbB of gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:292–298. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang CS, Müller WEG, Schröder HC, Guo YW. Disulfide- and multisulfide-containing metabolites from marine organisms. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2179–2207. doi: 10.1021/cr200173z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicolaou KC, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of epidithio-, epitetrathio-, and bis-(methylthio)diketopiperazines: synthetic methodology, enantioselective total synthesis of epicoccin G, 8,8’-epi-ent-rostratin B, gliotoxin, gliotoxin G, emethallicin E, and haematocin and discovery of new antiviral and antimalarial agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:17320–17332. doi: 10.1021/ja308429f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chankhamjon P, et al. Biosynthesis of the halogenated mycotoxin aspirochlorine in koji mold involves a cryptic amino acid conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:13409–13413. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen DS, et al. Orally absorbed cyclic peptides. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:8094–8128. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharf DH, et al. A dedicated glutathione S-transferase mediates carbon-sulfur bond formation in gliotoxin biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12322–12325. doi: 10.1021/ja201311d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, et al. Development of the first generation of disulfide-based subtype-selective and potent covalent pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:2227–2244. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zorzi A, Deyle K, Heinis C. Cyclic peptide therapeutics: past, present and future. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017;38:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brocchini S, et al. PEGylation of native disulfide bonds in proteins. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:2241–2252. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stephanopoulos N, Francis MB. Choosing an effective protein bioconjugation strategy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:876–884. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Block E, Ahmad S, Catalfamo JL, Jain MK, Apitz-Castro RT. Antithrombotic organosulfur compounds from garlic: structural, mechanistic, and synthetic studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:7045–7055. doi: 10.1021/ja00282a033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Block E, Bayer T, Naganathan S, Zhao SH. Allium chemistry: synthesis and sigmatropic rearrangements of alk(en)yl 1-propenyl disulfide S-oxides from cut onion and garlic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2799–2810. doi: 10.1021/ja953444h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanschen FS, Lamy E, Schreiner M, Rohn S. Reactivity and stability of glucosinolates and their breakdown products in foods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:11430–11450. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senter PD. Potent antibody drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chari RVJ, Miller ML, Widdison WC. Antibody–drug conjugates: an emerging concept in cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:3796–3827. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staben LR, et al. Targeted drug delivery through the traceless release of tertiary and heteroaryl amines from antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:1112–1119. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C, Corvaïa N. Strategies and challenges for the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017;16:315–337. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cerda MM, Hammers MD, Earp MS, Zakharov LN, Pluth MD. Applications of synthetic organic tetrasulfides as H2S donors. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2314–2317. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benavides GA, et al. Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17977–17982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705710104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu M, et al. Organotrisulfide: a high capacity cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:10027–10031. doi: 10.1002/anie.201603897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makarieva TN, et al. Varacin and three new marine antimicrobial polysulfides from the far-eastern ascidian polycitorsp. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:254–258. doi: 10.1021/np50116a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oku N, Matsunaga S, Fusetani N. Shishijimicins A-C, novel enediyne antitumor antibiotics from the ascidian didemnum proliferum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:2044–2045. doi: 10.1021/ja0296780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kajula M, et al. Bridged epipolythiodiketopiperazines from penicillium raciborskii, an endophytic fungus of rhododendron tomentosum harmaja. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:685–690. doi: 10.1021/np500822k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Witt D. Recent developments in disulfide bond formation. Synthesis. 2008;16:2491–2509. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Musiejuka M, Witt D. Recent developments in the synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfanes (disulfides) Org. Prep. Proced. Int. 2015;47:95–131. doi: 10.1080/00304948.2015.1005981. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng M, Tang B, Liang S, Jiang X. Sulfur containing scaffolds in drugs: synthesis and application in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016;16:1200–1216. doi: 10.2174/1568026615666150915111741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swan JM. Thiols, disulphides and thiosulphates: some new reactions and possibilities in peptide and protein chemistry. Nature. 1957;180:643–645. doi: 10.1038/180643a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bao M, Shimizu M. N-Trifluoroacetyl arenesulfenamides, effective precursors for synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides and sulfenamides. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:9655–9659. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2003.09.080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sivaramakrishnan S, Keerthi K, Gates KS. A chemical model for redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10830–10831. doi: 10.1021/ja052599e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunter R, Caira M, Stellenboom N. Inexpensive, one-pot synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides using 1-chlorobenzotriazole. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8268–8271. doi: 10.1021/jo060693n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Antoniow S, Witt D. A novel and eficient synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides. Synthesis. 2007;22:363–366. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szymelfejnik M, Demkowicz S, Rachon J, Witt D. Functionalization of cysteine derivatives by unsymmetrical disulfide bond formation. Synthesis. 2007;22:3528–3534. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taniguchi N. Unsymmetrical disulfide and sulfenamide synthesis via reactions of thiosulfonates with thiols or amines. Tetrahedron. 2017;73:2030–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2017.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vandavasi JK, Hu WP, Chen CY, Wang JJ. Efficient synthesis of unsymmetrical disulfides. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:8895–8901. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.09.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arisawa M, Yamaguchi M. Rhodium-catalyzed disulfide exchange reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6624–6625. doi: 10.1021/ja035221u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu H, Jiang X. Transfer of sulfur: from simple to diverse. Chem. Asian J. 2013;8:2546–2563. doi: 10.1002/asia.201300636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiao Z, et al. Efficient access to 1, 4-benzothiazine: palladium-catalyzed double C-S bond formation using Na2S2O3 as sulfurating reagent. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2594–2597. doi: 10.1021/ol400618k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei J, Li Y, Jiang X. Aqueous compatible protocol to both alkyl and aryl thioamide synthesis. Org. Lett. 2016;18:340–343. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qiao Z, Jiang X. Recent development in sulfur-carbon bond Formation reaction involving thiosulfate. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:1942–1946. doi: 10.1039/C6OB02833K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang M, Wei J, Fan Q, Jiang X. Cu(II)-catalyzed sulfide construction: both aryl groups utilization of intermolecular and intramolecular diaryliodonium salt. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:2918–2921. doi: 10.1039/C6CC09201B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan W, Wei J, Jiang X. Thiocarbonyl surrogate via combination of sulfur and chloroform for thiocarbamide and oxazolidinethione constructions. Org. Lett. 2017;19:2166–2169. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang M, Chen S, Jiang X. Construction of functionalized annulated sulfone via SO2/I exchange of cyclic diaryliodonium salts. Org. Lett. 2017;19:4916–4919. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, Wang M, Jiang X. Controllable sulfoxidationand sulfenylation with organic thiosulfate salts via dual electron- and energy-transfer photocatalysis. ACS Catalysis. 2017;7:7587–7592. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.7b02735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao X, Feng M, Jiang X. Transition-metal-free persulfuration to construct unsymmetrical disulfides and mechanistic study of sulfur redox process. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:4208–4211. doi: 10.1039/C4CC09633A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bailey TS, Zakharov LN, Pluth MD. Understanding hydrogen sulfide storage: probing conditions for sulfide release from hydrodisulfides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:10573–10576. doi: 10.1021/ja505371z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chauvin JPR, Griesser M, Pratt DA. Hydropersulfides: H-atom transfer agents par excellence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:6484–6493. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiao X, Feng M, Jiang X. New design of disulfurating reagent: facile and straightforward pathway to unsymmetrical disulfanes via Cu-catalyzed oxidative cross coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:14121–14121. doi: 10.1002/anie.201608011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearson RG. Hard and soft acids and bases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:3533–3539. doi: 10.1021/ja00905a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1565934 (3a), 1565935(5o), 1565936 (6a) and 1565937 (7d). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.