Abstract

AIM

To analyze the effect of intralesional steroid injections in addition to endoscopic dilation of benign refractory esophageal strictures.

METHODS

A comprehensive search was performed in three databases from inception to 10 April 2017 to identify trials, comparing the efficacy of endoscopic dilation to dilation combined with intralesional steroid injections. Following the data extraction, meta-analytical calculations were performed on measures of outcome by the random-effects method of DerSimonian and Laird. Heterogeneity of the studies was tested by Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. Risk of quality and bias was assessed by the Newcastle Ottawa Scale and JADAD assessment tools.

RESULTS

Eleven articles were identified suitable for analyses, involving 343 patients, 235 cases and 229 controls in total. Four studies used crossover design with 121 subjects enrolled. The periodic dilation index (PDI) was comparable in 4 studies, where the pooled result showed a significant improvement of PDI in the steroid group (MD: -1.12 dilation/month, 95%CI: -1.99 to -0.25 P = 0.012; I2 = 74.4%). The total number of repeat dilations (TNRD) was comparable in 5 studies and showed a non-significant decrease (MD: -1.17, 95%CI: -0.24-0.05, P = 0.057; I2 = 0), while the dysphagia score (DS) was comparable in 5 studies and did not improve (SMD: 0.35, 95%CI: -0.38, 1.08, P = 0.351; I2 = 83.98%) after intralesional steroid injection.

CONCLUSION

Intralesional steroid injection increases the time between endoscopic dilations of benign refractory esophageal strictures. However, its potential role needs further research.

Keywords: Intralesional steroid, Meta-analysis, Benign refractory esophageal stricture, Dilation

Core tip: Benign refractory stricture can be a very challenging pathology, which requires regular endoscopic dilations. Results of this meta-analysis suggest that endoscopic intralesional steroid injection significantly decreases the frequency of the endoscopic dilations in benign refractory esophageal strictures. In addition, there are very few and mild complications reported in association with this method. We believe that the benefits of intralesional steroid in the treatment of benign refractory stricture overweigh its risks. However, further research would be essential on this treatment method, as there are no data concerning its efficacy and safety in different etiologies of refractory esophageal strictures.

INTRODUCTION

Benign esophageal stricture (BES) is the narrowing of the lumen due to scar formation and fibrosis[1]. The most common, simple strictures need 3-5 sessions of endoscopic dilation at most, while benign refractory esophageal strictures (BRES) require more than 3-5 repeated endoscopic dilation sessions, or it is impossible to achieve a 14 mm wide lumen after 3 sessions of dilation[2].

Patients fail to maintain an effective swallowing action resulting in significant dysphagia. Other symptoms can be atypical chest pain, heartburn and odynophagia. BRES significantly impair the quality of life and may cause severe complications, most importantly weight loss due to malnutrition, but aspiration and regurgitation may occur too[3]. Patients with BRES need regular endoscopic dilations and it is not uncommon that the stricture recurs in days or weeks, necessitating frequent repeat procedures, in some cases multiple times a month.

There are many potential causes of BRES, the most frequent being peptic stricture from pathological acid exposure in gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD). Other common causes include radiation, caustic injury, and anastomotic strictures after esophageal surgery or endoscopic submucosal dissection. Less frequent etiologies include eosinophilic esophagitis, congenital and drug-induced stenosis, and it may also develop as a complication of nasogastric intubation or sclerotherapy of esophageal varices[1].

The pathogenesis of BRES is not entirely understood, but chronic inflammation must have a key role. The initial narrowing of the esophageal wall results from edema and muscular spasm as part of an inflammatory process. As the disease progresses, erosions and ulcerations evolve as well as chronic inflammation, leading to fibrous tissue production and collagen deposition. The chronic inflammation probably induces the synthesis of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and α2-macroglobulin, which are inhibitors of collagenase activity. Therefore, depositions of collagen form scars, resulting in the narrowing of the lumen and the rigidity of the wall[3]. Steroids (triamcinolone acetonide injection into 4 quadrants of the stricture[2]) reduce the activity of these inflammatory pathological pathways (e.g. the transcription of matrix protein genes, including fibronectin and procollagen), so this may be considered as an effective treatment of scar-forming conditions, providing the basis for the trials included in this meta-analysis[1].

The epidemiology of BRES is not well-known. Most of the available data are provided by small clinical studies and case studies. The incidence of esophageal stricture seems to be decreasing in parallel with the growing use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)[3,4], yet its common cause is GERD and it still occurs in 7%-23% of GERD patients with esophagitis[4].

Endoscopic dilation is an effective standard treatment for BES[1,2]; however, 30%-40% of patients show refractory dysphagia within the first year after intervention and require frequent and repeat dilations in the long term[3]. Several trials have been conducted to determine the efficacy of intralesional steroid injection in the treatment of BRES since the first encouraging results were published in a canine model in 1969[5]. However, a meta-analysis has not been carried out yet.

We wanted to investigate whether intralesional steroid injection in combination with dilation is beneficial in the treatment of BRES.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A meta-analysis was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement[6]. The meta-analysis was registered in advance in PROSPERO under the registration number 42017072329. The PICO items of the search strategy were: Population (P): Patients with esophageal stricture; intervention (I): Dilation plus intralesional steroid injection; control (C): Dilation alone; and outcomes (O): Dysphagia score (DS), total number of repeat dilations (TNRD) and periodic dilation index (PDI).

Search strategy

The article search was carried out in PubMed, Embase and Cochrane databases from inception to 10 April 2017. Two investigators conducted a comprehensive search with a combination of the following keywords: (oesophagus OR esophagus) AND [stricture OR stenosis OR refractory stricture OR benign stricture OR (o)esophageal stricture] AND (dilation OR dilatation) and (steroid OR triamcinolone OR intralesional steroid). No filters were imposed on the searches in the individual databases. References in the primarily eligible articles were screened for additional suitable publications.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Articles were selected if they had detailed data on a control (endoscopic dilation only) and a treatment group (endoscopic dilations with intralesional steroid injection). Benign refractory esophageal strictures of all etiologies requiring repeat dilations were included. Language was not an exclusion criterion. Conference abstracts were also included if they contained sufficient data. Case reports, case series, and results from pediatric and non-human trials were excluded. We did not contact the authors of the included articles.

Selection process: Records were managed by the EndNote X7.4 software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, United States) to remove duplicates. Publications were screened first by title, second by abstract, and finally by full-text, based on our eligibility criteria. The comprehensive search and the selection of the studies were carried out by two investigators.

Data extraction

Numeric and texted data were extracted onto a purpose designed Excel 2016 sheet (Office 365, Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States). The extracted data were the following: study author, year of publication, geographical location, study design, number of controls and cases, age of the patients, etiology of the strictures, length and location of the stricture, dose of the intralesional steroid injection, the outcomes of the treatment with and without intralesional steroid injection (DS, TNRD and PDI, the complications of the treatment and follow-up time). Data extraction was performed by two investigators and extracted data were checked by a third investigator.

Statistical analysis

In our statistical analysis, we compared the outcomes of treatment with dilation alone to the outcomes of dilation in combination with intralesional steroid injections. Meta-analytical calculations were conducted on the TNRD, PDI and DS. Standardized difference in means (SMD), difference in means (MD) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were calculated using the random-effects method developed by DerSimonian and Laird[7]. Results reported in the study in median and range were converted to means and standard deviation with the Hozo method[8]. Heterogeneity among trials was tested with Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. According to the Cochrane Handbook, I2 values of 25%-50%, 50%-75% and > 75% correspond to low, moderate and high degrees of heterogeneity[9]. The Q test implies that the heterogeneity among effect sizes reported in the studies under examination is more diverse than could be explained by random error only. We considered the Q test significant if P < 0.1. The presence of any publication bias was examined by visual inspection of the funnel plots.

Assessment of risk of selection and information bias

The assessment of risks of bias and quality was done at the outcome level. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale[10] was used for case control trials with the following 8 items. Item 1: Were the cases randomly selected subjects with BRES without significant exclusion criteria? Item 2: Were the controls randomly selected subjects with BRES without significant exclusion criteria? Item 3: Was there an endoscopic or radiological diagnosis of BRES? Item 4: Was the diagnosis of non-refractory BES excluded? Item 5: Were the cases and controls comparable? Item 6: Were the subjects and investigators blinded to the intralesional steroid treatment? Item 7: Was follow-up long enough (≥ 6 mo) for outcomes to occur? Item 8: Was there complete follow up of all subjects enrolled?

For the above detailed items an answer of yes represented low risk, no represented high risk, while lack of description represented unknown risk of bias. Modified NOS was used for studies with cross-over study design with the 7 out of the above detailed 8 items as item 2 regarding the selection of controls was not applicable due to the cross-over study design.

The JADAD scoring system[11] was used for the assessment of randomized controlled trials with the following 5 items. Item 1: Was the study described as randomized? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point); Item 2: Was the randomization scheme described and appropriate? (Yes = 1 point, No = -1 point); Item 3: Was the study described as double-blind? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point); Item 4: Was the method of double blinding appropriate? (Yes = 1 point, No = -1 point, if the answer of Item 3 was No, Item 4 is not calculable); Item 5: Was there a description of dropouts and withdrawals? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point).

Assessment of the grade of evidence

The GRADE system was used to assess the strength of recommendation and quality of evidence of our results. GRADE stands for Grades of Recommendation Assessment, Development, and Evaluation[12].

RESULTS

Results of the selection process

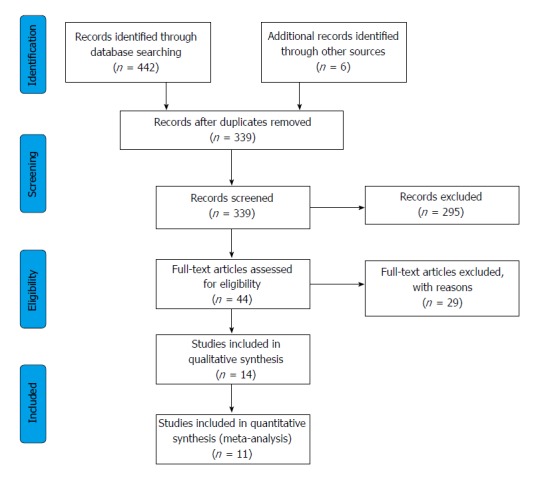

Our search identified 321 articles in Embase, 109 in PubMed, and 12 in the Cochrane database, a total of 11 articles[13-23] (10 in English and 1 in Portuguese) eligible for the quantitative analysis, these included 343 patients in total, 235 cases and 229 controls, as four studies used cross-over design with 121 subjects enrolled. Further 3 articles gave results, but they were not suitable for meta-analytical calculations[24-26]. The selection process is shown on Figure 1 and the main characteristics of the studies included are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow chart of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies included

| Study | Study design | Country | Parameter |

Patients |

Etiology of BRES | Follow-up (mo) |

Complication |

||

| Cases | Control | Cases | Control | ||||||

| Kochhar et al[13] 1999 | Crossover | India | PDI | 14 | 14 | Mixed | 23 | 1 | 0 |

| Kochhar et al[14] 2002 | Crossover | India | PDI | 71 | 71 | Mixed | 59 | 0 | 0 |

| Ahn et al[16] 2015 | Crossover | New Zealand | PDI | 25 | 25 | Mixed | 90 | 0 | 0 |

| Nijhawan et al[16] 2016 | Crossover | India | PDI | 11 | 11 | Corrosive | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Dunne et al[17] 1999 | RCT | United States | TNRD, DS | 20 | 22 | Mixed | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| Altintas et al[18] 2004 | RCT | Turkey | TNRD | 11 | 10 | Mixed | 48 | 1 | 1 |

| Orive-Calzada et al[20] 2012 | Cohort | Spain | TNRD | 14 | 9 | Mixed | 45 | 0 | 1 |

| Hirdes et al[19] 2013 | RCT | Netherland | TNRD, DS | 31 | 29 | Anastomotic | 33 | 5 | 1 |

| Pereira-Lima et al[21] 2015 | RCT | Brazil | TNRD, DS | 9 | 10 | Mixed | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Camargo et al[22] 2003 | RCT | Brazil | DS | 7 | 7 | Mixed | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Rupp et al[23] 1995 | RCT | United States | DS | 22 | 21 | Mixed | 11 | 0 | 0 |

PDI: Periodic dilation index; NRD: Total number of repeat dilations; DS: Dysphagia score; RCT: Randomized controlled trial; BRES: Benign refractory esophageal stricture.

Results of the statistical analysis

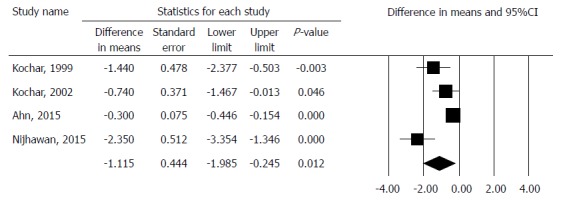

The PDI was comparable in 4 studies with crossover design involving 121 patients[13,14,15,16]. The pooled result showed that PDI significantly decreased in the intralesional steroid plus dilation group, with difference in means method. (MD: -1.16, 95%CI: -1.99, -0.25, P = 0.012). There was a high degree of heterogeneity across the studies included in the analysis for PDI (Q = 11.73, df = 3, P = 0.0084, I2 = 74.43%). A detailed result of the analysis on PDI by the random effect model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the random effect analysis of the 4 studies concerning periodic dilation index shows a significant decrease of periodic dilation index after intralesional steroid injection in addition to endoscopic dilation.

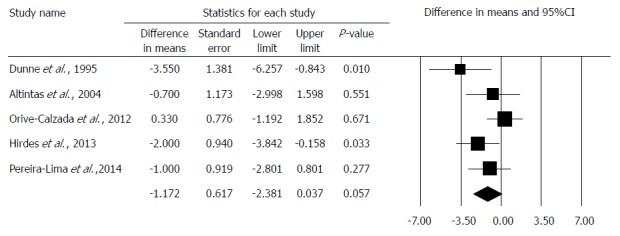

The TNRD was comparable in 5 studies[17,18,19,20,21], where MD was -1.172 in comparison to the dilation alone group (95%CI: -0.238, 0.053; P = 0.057). The studies in this analysis showed no heterogeneity: (Q = 3.66; df = 4; P = 0.45; I2 = 0.0%). A detailed result of the analysis on TNRD by the random effect model is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the random effect analysis of the 5 studies concerning total number of repeat dilation shows a non-significant decrease of total number of repeat dilation after intralesional steroid injection in addition to endoscopic dilation.

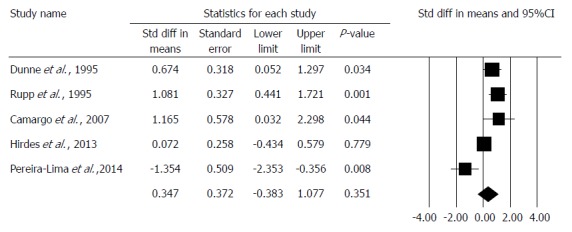

The DS was comparable in 5 studies[17,18,21,22,23], and an improvement could not be observed in the combined therapy group (std. MD: 0.347, 95%CI: -0.383, 1.077, P = 0.351). We note that DS was only comparable with standardization as different studies used different scoring systems. There was a high degree of heterogeneity across the studies included in the analysis for DS (Q = 24.97, df = 4, P < 0.001, I2 = 83.98%). A detailed result of the analysis on DS by the random effect model is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the random effect analysis of the 5 studies concerning dysphagia score shows no significant improvement of dysphagia score after intralesional steroid injection in addition to endoscopic dilation.

Complications

Due to the low number of events of complications, statistical analysis was not possible; therefore, only narrative synthesis could be performed. It is important to note that all trials reported low numbers of complications; therefore, this technique seems to be safe. Kochhar et al[13] reported transient worsening of dysphagia for 24 h in one patient after the intralesional steroid injection. There were 2 perforations reported by Altintas et al[18] one in the dilation only and one in the combined treatment group, both in caustic strictures. Hirdes et al[19] reported one gastrointestinal bleeding in the monotherapy group and 5 adverse events, such as 1 laceration and 4 candida esophagitis in the patients treated with intralesional steroid. However, the laceration developed in a patient, who continued the anticoagulant therapy during the procedure, and the other 4 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, which is a risk factor for candidiasis. One perforation occurred in the dilation only group in Orive-Calzada et al[20] trial, with no complication reported in patients with intralesional steroid injection. Other trials did not report any adverse events in either therapy group.

Results of the assessment of risk of bias and quality

Detailed results of the assessments are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Results of the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for cross-over and cohort studies

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Item 6 | Item 7 | Item 8 | ||

| Ahn et al[21] 2015 | - | N/A | + | + | - | ? | + | ? | Modified NOS |

| Kochhar et al[21] 2015 | - | N/A | + | + | - | ? | + | + | Modified NOS |

| Kochhar et al[21] 2015 | + | N/A | + | + | - | ? | + | + | Modified NOS |

| Nijhawan et al[21] 2015 | - | N/A | + | + | - | - | + | + | Modified NOS |

| Orive-Calza et al[21] 2015 | - | - | + | ? | + | + | + | ? | NOS |

Item 1: Were the cases randomly selected subjects with BRES without significant exclusion criteria? Item 2: Were the controls randomly selected subjects with BRES without significant exclusion criteria? Item 3: Was there an endoscopic or radiological diagnosis of BRES? Item 4: Was the diagnosis of non-refractory BES excluded? Item 5: Were the cases and controls comparable? Item 6: Were the subjects and investigators blinded to the intralesional steroid treatment? Item 7: Was follow-up long enough (≥ 6 mo) for outcomes to occur? Item 8: Was there complete follow up of all subjects enrolled? For the above detailed items an answer of yes represented low risk, no represented high risk, while lack of description represented unknown risk of bias (- = high risk of bias; ? = unknown or moderate risk of bias; + = low risk of bias). BRES: Benign refractory esophageal stricture; BES: Benign esophageal stricture.

Table 3.

Results of the quality assessment of randomized controlled trials by the JADAD scoring system

| Item 1 | Item 2 | Item 3 | Item 4 | Item 5 | Overall | Quality | |

| Dunne et al[17] 1999 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low; 0 |

| Altintas et al[18] 2004 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low; 0 |

| Hirdes et al[19] 2013 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | High; 5 |

| Pereira-Lima et al[21] 2015 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | High ,5 |

| Camargo et al[21] 2003 | 1 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | Low; 1 |

| Rupp et al[21] 1995 | 1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low; 0 |

Item 1: Was the study described as randomized? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point); Item 2: Was the randomization scheme described and appropriate? (Yes = 1 point, No = -1 point); Item 3: Was the study described as double-blind? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point); Item 4: Was the method of double blinding appropriate? (Yes = 1 point, No = -1 point, if the answer of Item 3 was No, Item 4 is not calculable); Item 5: Was there a description of dropouts and withdrawals? (Yes = 1 point, No = 0 point). Low range of quality: 3 >, high range of quality: 2 <.

DISCUSSION

The summary of our findings are shown in Table 4. Endoscopic dilation as the standard treatment of BES is effective in most cases[1,2], but BRES develops in some cases, necessitating repeated endoscopic dilations in the long term[3]. Endoscopic intralesional steroid injections may be useful and may reduce the number of necessary dilations. However, because of the low incidence of refractory benign esophageal strictures and because of the low number of studies and articles published on the topic, there is little evidence as to whether this approach is beneficial. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, no meta-analysis has been carried out yet.

Table 4.

Summary of findings

| Outcomes | Intervention values | Control values | Number of patients | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| PDI | 0.335/mo | 1.355/mo | 121 | Very low | Only studies with cross-over design were analyzed |

| MD: -1.12 | |||||

| 95%CI: -1.99 to -0.25 | |||||

| P = 0.012 | |||||

| TNRD | n/a | n/a | 165 | Very low | Different length of follow up results in high risk of bias |

| MD: -1.17 | |||||

| 95%CI: -0.24 to 0.05 | |||||

| P = 0.057 | |||||

| DS | n/a | n/a | 178 | Very low | Different scoring scales were used and different lengths of follow up result in high risk of bias |

| SMD: 0.35 | |||||

| 95%CI: -0.38 to 1.08 | |||||

| P = 0.351 | |||||

PDI: Periodic dilation index; TNRD: Total number of repeat dilations; DS: Dysphagia score; MD: Mean difference; SMD: Standardized mean difference.

The effectiveness of intralesional steroid injections for BRES was first tested in a canine model in 1969[7]. The first study on humans was carried out by Holder et al[27]. They examined 10 pediatric patients, some with post-surgical (anastomotic) strictures and some with corrosive strictures (from acid or lye). They found that additional intralesional steroid treatments were only effective on the anastomotic strictures, but not on the caustic ones.

Among the parameters of the 11 articles included in our meta-analysis, the PDI, TNRD and DS were comparable. It is important to note that all studies used boogie dilators and no studies reported results with balloon dilation

The PDI values were calculated with the mean difference method due to the similar measures and showed a significant improvement of the PDI in the steroid group. These four articles[13-16] examined one patient group, treated first with a series of dilations alone, followed by a dilation combined with intralesional steroid injections afterwards. PDI values were compared before and after the intralesional steroid injections, as these patients all required continuing endoscopic dilation despite the steroid injections. It must be noted that the study by Nijhawan et al[15] showed a statistically significant, strong improvement in the PDI with the combined therapy in patients with corrosive strictures only, so the lack of subgroup analysis results in a high degree of bias.

The TNRD[17,18,19,20,21] was compared with the method noted above. We found a non-significant (P = 0.057) improvement in the combined therapy group using the mean difference method. Interestingly, the article by Orive-Calazda et al[20] did not identify improvement compared to the control groups: 9 study group patients and 12 control group patients received 30 and 37 dilations, respectively. The only published multicenter study investigating the TNRD was carried out by Hirdes et al[19], but all the patients had an anastomotic stricture, resulting in a bias in the interpretation of their data. In this case, the importance of the subgroup analysis must be highlighted again.

The third parameter, which describes the quality of life best, is the DS. Due to the use of different scoring systems, it was only possible to compare the data from five articles[17,19,21,22,23] with standardization. Based on the statistical analysis of the articles under examination, we did not find any improvement in the steroid group. However, this result cannot be regarded as relevant due to the high heterogeneity of the data. It is important to note that Pereira-Lima et al[21], proved a significant improvement in the DS in the combined therapy group in a randomized controlled trial. Hirdes et al[19] reported DS results in patients with anastomotic strictures only, which remains a significant bias.

Only a few studies reported outcomes of the treatment with intralesional steroids for different etiologies of the strictures. Kochhar et al[13] and Nijhawan et al[15] demonstrated significant improvement in caustic strictures. Hirdes et al[19] detected no benefit from the combined treatment in anastomotic stricures. Ahn et al[16]and Kochhar et al[14] showed the most improvement in peptic strictures, both in studies with cross over design.

There was no data on the histological activity of the inflammation of the strictures, although intralesional steroid is likely to be of more benefit in strictures with high degree of active inflammation, than in long standing fibrotic strictures. Subgroup analysis on the degree of inflammation could have given further in depth understanding of the effects of intralesional steroid injections.

Limitations

We observed variable reporting of intervention outcomes. Studies with low patient numbers, heterogeneous data, use of different scoring systems, and differences in follow-up time resulted in significant difficulties of the analysis. Even though two long-term studies[17,23] were only available as abstracts, they contained the necessary data for the purposes of this meta-analysis. In addition, there was a lack of detailed data on etiological subgroups, which prevented us from performing a subgroup analysis, reulting in a high risk of bias.

In summary, the use of intralesional steroid injections seems to be beneficial in the treatment of BRES with a very low quality of evidence and a weak recommendation. A large, multicenter, prospective randomized trial could provide better evidence for the role of intralesional steroid therapy in the treatment of BRES.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Benign refractory esophageal stricture deteriorates the quality of life, as impaired and often painful swallowing necessitates semi liquid or liquid diet and leads to poor nutrition. Regular endoscopic dilations are a huge burden to the patients, carry risks of complications, require special expertise, and accessories of the endoscopy unit.

Research motivation

Our aim was to investigate if there is any benefit of intralesional steroid injection in addition to endoscopic dilation in the treatment of refractory esophageal strictures.

Research objectives

This is the first comprehensive article in this topic, taking into account all the available evidences and this study quantifies the effect of intralesional steroid injection in addition to endoscopic dilation of benign refractory esophageal stricture.

Research methods

A meta-analysis was performed following the guidelines of the PRISMA P protocol and the review was registered on PROPSPERO. PubMed, Cochrane Library and Embase databases were comprehensively searched for trials eligible for the analysis, describing the outcomes of dilation in comparison to dilation with intralesional steroids. The risks of bias and quality of the individual studies were assessed by using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale and JADAD Score. The random effect model described by DerSimonian-Laird was used to perform the statistical calculations.

Research results

The statistical analysis involved 343 patients with benign refractory stricture. The results showed that intralesional steroid significantly increased the time between endoscopic dilations, from 1.3-0.3 dilations/month. However, the dysphagia score and the total number of dilation did not improve.

Research conclusions

Intralesional steroid injection increases the time between endoscopic dilations of benign refractory esophageal strictures.

Research perspectives

Further research would be essential to understand the effects of intralesional steroid injection in the treatment of benign refractory esophageal strictures. A multi-center, double blind, randomized controlled trial could give better answers. Detailed data on the outcomes of the treatment in view of the etiology, the time of the diagnosis, the degree of inflammation/fibrosis, the length and location of the stricture should be collected with a long follow up period.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Hungary

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Supported by the Project Grant (KH125678 to PH) and an Economic Development and Innovation Operative Program Grant (GINOP 2.3.2-15-2016-00048 to PH) from the National Research, Development and Innovation Office.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors deny any conflict of interest.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Peer-review started: March 15, 2018

First decision: March 27, 2018

Article in press: April 23, 2018

P- Reviewer: Sterpetti AV S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

Contributor Information

László Szapáry, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Benedek Tinusz, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Nelli Farkas, Institute of Bioanalysis, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Katalin Márta, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Lajos Szakó, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Ágnes Meczker, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Roland Hágendorn, Department of Gastroenterology, First Department of Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Judit Bajor, Department of Gastroenterology, First Department of Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Áron Vincze, Department of Gastroenterology, First Department of Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Zoltán Gyöngyi, Department of Public Health Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Alexandra Mikó, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Dezső Csupor, Department of Pharmacognosy, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Szeged, Szeged 6720, Hungary.

Péter Hegyi, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary.

Bálint Erőss, Institute for Translational Medicine, Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs 7624, Hungary. eross.balint@pte.hu.

References

- 1.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Pasha SF, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Jue TL, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Sharaf R, Saltzman JR, Shergill AK, Cash B. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation and management of dysphagia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:191–201. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spaander MC, Baron TH, Siersema PD, Fuccio L, Schumacher B, Escorsell À, Garcia-Pagán JC, Dumonceau JM, Conio M, de Ceglie A, Skowronek J, Nordsmark M, Seufferlein T, Van Gossum A, Hassan C, Repici A, Bruno MJ. Esophageal stenting for benign and malignant disease: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2016;48:939–948. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-114210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poincloux L, Rouquette O, Abergel A. Endoscopic treatment of benign esophageal strictures: a literature review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11:53–64. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2017.1260002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Eklund S. Esophageal stricture: incidence, treatment patterns, and recurrence rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2685–2692. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashcraft KW, Holder TM. The expeimental treatment of esophageal strictures by intralesional steroid injections. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1969;58:685–91 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 11.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kochhar R, Ray JD, Sriram PV, Kumar S, Singh K. Intralesional steroids augment the effects of endoscopic dilation in corrosive esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:509–513. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kochhar R, Makharia GK. Usefulness of intralesional triamcinolone in treatment of benign esophageal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:829–834. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.129871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nijhawan S, Udawat HP, Nagar P. Aggressive bougie dilatation and intralesional steroids is effective in refractory benign esophageal strictures secondary to corrosive ingestion. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:1027–1031. doi: 10.1111/dote.12438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahn Y, Coomarasamy C, Ogra R. Efficacy of intralesional triamcinolone injections for benign refractory oesophageal strictures at Counties Manukau Health, New Zealand. N Z Med J. 2015;128:44–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunne DP, Rupp T, Rex DK, Rahmani E, Ness RM. Five year follow up of prospective randomized trial of savory dilations with or without intralesional steroids of benign gastrooesophageal reflux strictures. Gastroenterology. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altintas E, Kacar S, Tunc B, Sezgin O, Parlak E, Altiparmak E, Saritas U, Sahin B. Intralesional steroid injection in benign esophageal strictures resistant to bougie dilation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:1388–1391. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirdes MM, van Hooft JE, Koornstra JJ, Timmer R, Leenders M, Weersma RK, Weusten BL, van Hillegersberg R, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Plukker JT, et al. Endoscopic corticosteroid injections do not reduce dysphagia after endoscopic dilation therapy in patients with benign esophagogastric anastomotic strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:795–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orive-Calzada A, Bernal-Martinez A, Navajas-Laboa M, Torres-Burgos S, Aguirresarobe M, Lorenzo-Morote M, Arevalo-Serna JA, Cabriada-Nuño JL. Efficacy of intralesional corticosteroid injection in endoscopic treatment of esophageal strictures. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:518–522. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182747b31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pereira-Lima JC, Lemos Bonotto M, Hahn GD, Watte G, Lopes CV, dos Santos CE, Teixeira CR. A prospective randomized trial of intralesional triamcinolone injections after endoscopic dilation for complex esophagogastric anastomotic strictures: steroid injection after endoscopic dilation. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:1156–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3781-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camargo MA, Lopes LR, Grangeia Tde A, Andreollo NA, Brandalise NA. Use of corticosteroids after esophageal dilations on patients with corrosive stenosis: prospective, randomized and double-blind study. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2003;49:286–292. doi: 10.1590/s0104-42302003000300033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rupp T, Earle D, Ikenberry S, Lumeng L, Lehman G. Randomized trial of Savary dilation with/without intralesional steroids for benign gastroesophageal reflux strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:357. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramage JI Jr, Rumalla A, Baron TH, Pochron NL, Zinsmeister AR, Murray JA, Norton ID, Diehl N, Romero Y. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of endoscopic steroid injection therapy for recalcitrant esophageal peptic strictures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2419–2425. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee M, Kubik CM, Polhamus CD, Brady CE 3rd, Kadakia SC. Preliminary experience with endoscopic intralesional steroid injection therapy for refractory upper gastrointestinal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:598–601. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70199-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goncalves C, Almeida N, Gomes D. Injeccao intralesional de betametasona nas estrenoses benignas do esófago. Gastrenterol. 2006;13:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holder TM, Ashcraft KW, Leape L. The treatment of patients with esophageal strictures by local steroid injections. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:646–653. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(69)90492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]