Abstract

Objectives:

Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ)/medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) include both bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaw (BRONJ) and denosumab-related osteonecrosis of jaw (DRONJ). The purpose of this study is to study radiological characteristics of ARONJ/MRONJ. These imaging features may serve as one useful aid for assessing ARONJ/MRONJ.

Methods:

CT scans of 74 Japanese patients, who were clinically diagnosed by inclusion criteria of ARONJ/MRONJ, obtained between April 1, 2011 and September 30, 2016, were evaluated. We investigated the CT imaging features of ARONJ/MRONJ, and clarified radiological differentiation between BRONJ and DRONJ, BRONJ due to oral bisphosphonate administration and due to intravenous bisphosphonate administration, BRONJ with respective kinds of medication, BRONJ with long-term administration and short-term administration, BRONJ with each clinical staging respectively. Fisher’s exact test, χ2 test, Student’s t-test and analysis of variance were performed in the statistical analyses.

Results:

Unilateral maxillary sinusitis was detected in all patients with upper ARONJ/MRONJ (100%). DRONJ showed large sequestrum more frequently than BRONJ (3/4, 75 vs 3/35, 8.6%, p < 0.05). DRONJ showed periosteal reaction more frequently than BRONJ (4/10, 40 vs 7/65, 10.1%, p < 0.05). Patients of BRONJ resulting from intravenous bisphosphonate administration showed larger and more frequent buccolingual cortical bone perforations than BRONJ resulting from oral bisphosphonate administration (7/8, 87.5 vs 11/30, 36.7%, p < 0.05). There was no significant correlation between CT findings and respective kinds of medication, long/short-term administration, clinical stages of BRONJ.

Conclusions:

ARONJ/MRONJ has characteristic CT image findings which could be useful for its assessment.

Introduction

Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (ARONJ) is a now well-known complication associated with antiresorptive medications and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (MRONJ) is a complication associated with antiresorptive medications and antiangiogenic medications. These medications decrease bone turnover and are used to manage cancer-related conditions or cancer itself. ARONJ/MRONJ includes bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) and denosumab-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (DRONJ). Bisphosphonate and denosumab are antiresorptive drugs used primarily in management of osteoporosis/osteopenia and metastastic bone disease.

Bisphosphonate, a non-metabolized analogue of pyrophosphate, is a drug used for prevention of osteoporosis as well as treatment of skeletal metastases (especially in breast cancer and prostate cancer), hypercalcemia associated with malignancy, Paget’s disease and multiple myeloma.1, 2 The incidence of BRONJ in patients taking intravenous bisphosphonate is significantly greater than in patients taking oral bisphosphonate.3–6 Still, the underlying pathophysiological mechanism has not been fully elucidated.

Denosumab, an inhibitor of the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa ligand (RANKL), is an antiresorptive agent that exists as a fully humanized monoclonal antibody against RANKL and inhibits osteoclast function and associated bone resorption. This medication was introduced as a more powerful alternative to bisphosphonate with a hope to lower the incidence of complications, but it also has become known as a cause of osteonecrosis of the jaw.7–9

According to the recommendations of position paper 2017 of the Japanese allied committee on osteonecrosis of the jaw, ARONJ is diagnosed when all of the following clinical features are present: “Patients have a history of treatment with bisphosphpnate or denosumab,” “Patients have no history of radiation therapy to the jaw. Bone lesions of ARONJ must be differentiated from cancer metastasis to the jawbone by histological examination,” and “Exposure of alveolar bone in the oral cavity, jaw, and/or face is continuously observed for longer than 8 weeks after first detection by a medical or dental expert, or the bone is palpable in the intra- or extraoral fistula for longer than 8 weeks. These criteria do not apply to Stage 0 ARONJ”.10

According to the recommendations of American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) 2014 position paper, MRONJ is diagnosed when all of the following clinical features are present: “Current or previous treatment with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic agents”, “Exposed bone or bone that can be probed through an intraoral or extraoral fistula in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for longer than 8 weeks”, and “No history of radiation therapy to the jaws or obvious metastatic disease to the jaws”.11 The clinical staging system of MRONJ recommended by AAOMS is classified from Stage 0 to 3 according to the clinical findings including the presence of exposed and necrotic bone or fistulas, degree of extention to jaw bone and symptoms.11

Although CT findings of BRONJ have been reported,12–15 so far the image findings of ARONJ/MRONJ including BRONJ and DRONJ are not specific and can also be similar to ordinary osteomyelitis of the jaw. They both generally present as lytic and/or sclerotic lesion occasionally with sequestrum, periosteal reaction, cortical perforation or soft tissue swelling on CT. Other conditions that are hard to differentiate from BRONJ include osteoradionecrosis, cancer metastasis and Paget’s disease.12 Also, CT findings of BRONJ have not been studied based on whether BRONJ was caused by oral bisphosphonate or intravenous bisphosphonate. Moreover, neither clinical diagnostic criteria, as described above, nor clinical stages currently include radiological evaluation factors.

Common imaging modalities to evaluate ARONJ/MRONJ are panoramic radiography (PR), CT, MRI and bone scintigraphy. CT has a great advantage of morphological evaluation and delineating the extent of the disease in comparison with PR for observation of the osteonecrosis of the jaws.13,15–17 Because of radiation concern and availability, bone scintigraphy has not been widespread so far. For these reasons, CT is considered as a standard modality in evaluation for ARONJ/MRONJ. Though MRI may provide supportive information in its diagnosis, this modality is not readily available at all places.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the CT imaging features of ARONJ/MRONJ, and clarify radiological differentiation between BRONJ and DRONJ, BRONJ due to oral bisphosphonate administration and due to intravenous bisphosphonate administration, BRONJ with respective kinds of medication, BRONJ with long-term administration and short-term administration, BRONJ with each clinical staging respectively.

Methods and materials

This retrospective study was approved by the IRB and Ethic Committee at Tokyo Dental Collage, Ichikawa General Hospital (Approval number: I 16–62). The requirement of an informed consent was waived. CT scans of 74 Japanese patients obtained between April 1, 2011 and September 30, 2016 were evaluated.

The subjects included patients who were clinically diagnosed as ARONJ/MRONJ including BRONJ and DRONJ. The inclusion criteria for the study followed the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw definition of ARONJ10 and AAOMS definition of MRONJ.11 We evaluated earliest CT imaging performed at our hospital. These examinations were performed by using a 64-section MDCT scanner, a model Aquilion ONE (Toshiba Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan) with the following standard protocol: 64 × 0.625 mm collimation with 0.5 mm-thick sections, 2 mm reconstruction, and a pitch of 0.942. The CT threshold was adjusted in the bone algorithm (window center and window width were fixed as 500 and 3000) to evaluate the imaging features of the mandible and the maxilla, and in soft tissue algorithm (window center and window width were fixed as 50 and 350) to confirm such soft tissue swelling, maxillary sinusitis caused from ARONJ/MRONJ of the maxilla.

In this study, two radiologists (AB with 9 years experience, specialized in head and neck imaging and YK with 19 years experience, specialized in musculoskeletal radiology) retrospectively evaluated and interpreted the CT findings clinically diagnosed lesions with consensus on a picture archiving and communication systems monitor and analyzed the findings.

Findings of ARONJ/MRONJ (N = 74, 75 jaws) were evaluated for age, sex, location (mandible/maxilla, anterior/posterior/whole, laterality), and CT findings as described as below; internal texture (normal, sclerotic, lytic and sclerotic), the presence of sequestrum, size of sequestrum (larger or smaller than 20 mm), periosteal reaction, cortical perforation (buccal, lingual, both), soft tissue swelling (including gingiva, muscles, and subcutaneous fat), bone expansion, unilateral maxillary sinusitis adjacent upper ARONJ/MRONJ, and pathological fracture. The CT findings were statistically compared between BRONJ and DRONJ, BRONJ due to oral bisphosphonate administration and due to intravenous bisphosphonate administration, BRONJ with respective kinds of medication, BRONJ with long-term administration and short-term administration, BRONJ with each clinical staging respectively. Period of duration of medication was determined as 4 years, because increased incidence of BRONJ in patients with osteoporosis who were treated with bisphosphonate for longer than 4 years.10

Fisher’s exact test χ2 test, Student’s t-test and analysis of variance were performed in the statistical analysis. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare sex, location (maxilla or mandible), the presence of sequestrum, sequestrum size, periosteal reaction, soft tissue swelling, bone expansion and pathological fractures as the variables are shown in 2 × 2 tables. χ2 test was used to compare location (anteroposterior), internal texture, labial or buccal/lingual cortical perforation, as those are in 3 × 2 tables and sex, location (maxilla or mandible), the presence of sequestrum, sequestrum size, periosteal reaction, soft tissue swelling, bone expansion and pathological fractures as the variables are shown in 2 × 4 tables. Student’s t-test and analysis of variance were used to compare age. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted with backward selection with significant findings in univariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed by using BellCurve for Excel (SSRI, Tokyo, Japan). A p value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

74 patients, 75 ARONJ/MRONJ jaws [60 females (81%) and 14 males (19%); age range: 50–91 years; average age (± SD), 76.4 ± 9.2 years] were evaluated. A male presented with ARONJ/MRONJ in maxilla and mandible. For all we could evaluate, duration of medication administration including bisphosphonate and denosumab ranged 0.2 to 15 years, average was 3.44 years. Patients with ARONJ/MRONJ data are presented in Table 1. BRONJ was more prevalent (86.5%) than DRONJ (13.5%). Out of 10 DRONJ patients, 6 were cancer and 3 were osteoporosis patients. Among patients with BRONJ, more patients had undergone oral bisphosphonate therapy (73.4%) than intravenous administration (26.6%) in our hospital. The three most common underlying primary diseases were osteoporosis, breast cancer and prostate cancer. In our study, MRONJ clinical Stage 2 was the most common staging.

Table 1.

Patients with MRONJ data (N = 74)

| No. of patients (%) | |

| Types of MRONJ | |

| BRONJ | 64 (86.5) |

| DRONJ | 10 (13.5) |

| Administration way of medication in BRONJ | |

| Oral administration | 47 (73.4) |

| Intravenous administration | 17 (26.6) |

| Kinds of medication in BRONJ | |

| Alendronate | 26 (40.6) |

| Zoledronate | 16 (25.0) |

| Risedronate | 10 (15.6) |

| Minodronate | 9 (14.1) |

| Unknown | 3 (4.7) |

| Duration of BRONJ administration | |

| Long duration (more 4 years) | 17 (26.6) |

| Short duration (less 4 years) | 31 (48.4) |

| Unkown | 16 (25.0) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Osteoporosis | 44 (59.5) |

| Breast cancer | 8 (10.8) |

| Prostate cancer | 7 (9.5) |

| Multiple myeloma | 5 (6.8) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 3 (4.0) |

| Renal cancer | 2 (2.7) |

| Gastric cancer | 1 (1.3) |

| Colorectal cancer | 1 (1.3) |

| Others | 3 (4.1) |

| MRONJ stage | |

| 0 | 3 (4.0) |

| 1 | 19 (25.7) |

| 2 | 33 (44.6) |

| 3 | 19 (25.7) |

| Treatment methods | |

| Operative | 20 (27.0) |

| Non-operative | 54 (73.0) |

BRONJ, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaw; DRONJ, denosumab-related osteonecrosis of jaw; MRONJ, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

General radiological findings of all ARONJ/MRONJ

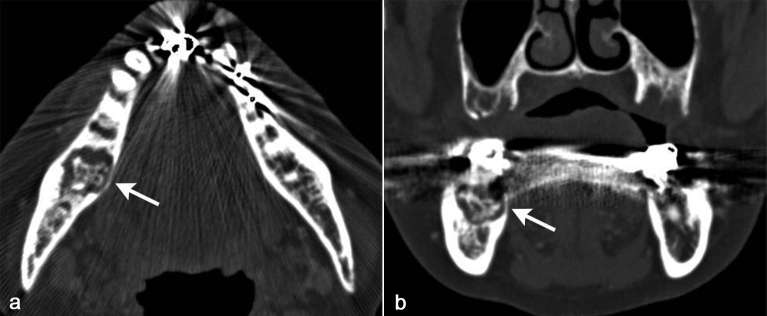

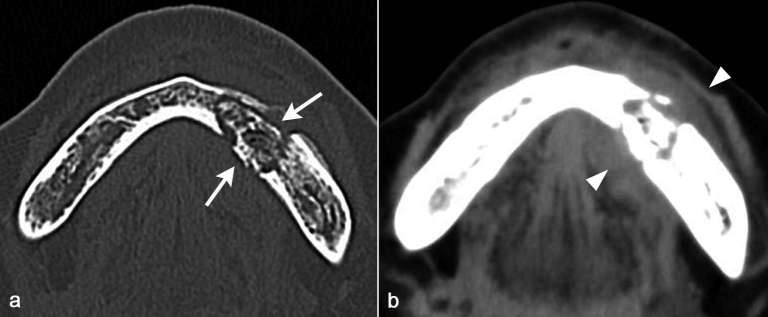

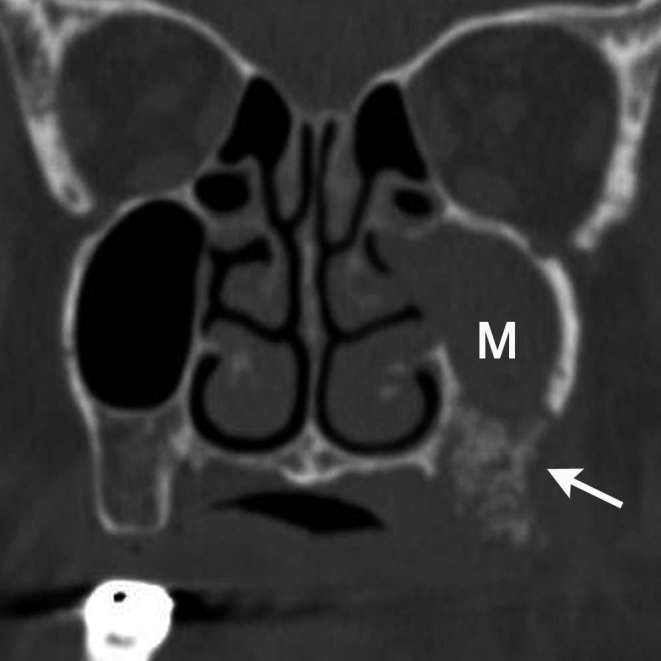

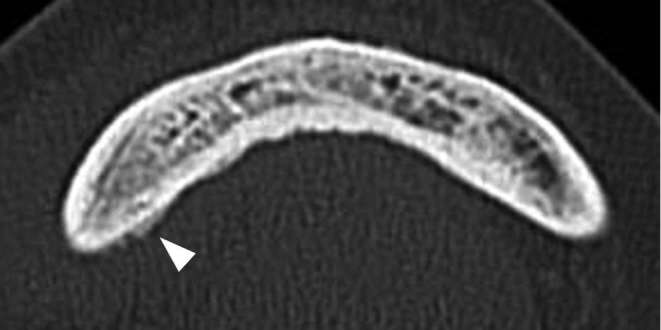

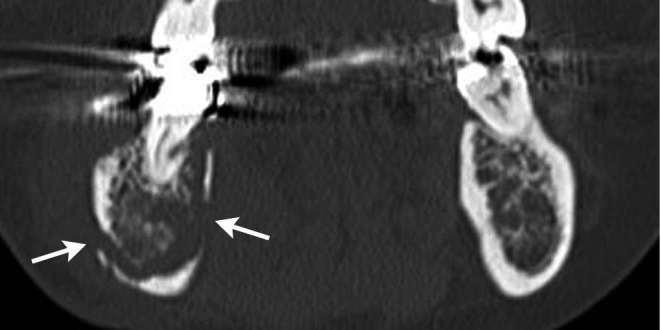

Findings of patients with ARONJ/MRONJ are presented in Table 2. ARONJ/MRONJ were mostly presented in the mandible (78.7%) and mostly presented in posterior portion of the both mandible and the maxilla (84%) (Figure 1). ARONJ/MRONJ of right side (42.7%) was similar to that of left side (46.7%). The internal texture of ARONJ/MRONJ were mainly lytic and sclerotic type (61.3%) (Figures 1–3), subsequently sclerotic type (34.7%) and then normal type (3%). Sequestrum was seen in about a half (52%) of all ARONJ/MRONJ (Figures 1–3). Among those with sequestrum, the size of sequestrum was small in 84.6% of the cases (Figures 1 and 3). Periosteal reactions adjacent to ARONJ/MRONJ were detected in relatively low frequency (17.3%). Cortical perforation was detected in more than half of the cases (57.3%). The frequency of both buccal and lingual cortical perforation (51.2%) (Figure 2) was slightly greater than that of buccal only (39.5%) (Figure 3), while that of lingual lesion was only 9.3%. Swelling of soft tissue including gingiva on CT was detected in relatively high frequency (81.3%) (Figures 2 and 3). Bone expansions were detected in one third of all ARONJ/MRONJ (33.3%). Of note, unilateral maxillary sinusitis was detected in all patients with upper ARONJ/MRONJ (100%) (Figure 4). Pathological fractures were uncommon, presenting in only 5.3% of the cases.

Table 2.

Findings of patients with MRONJ (N = 74, 75 jaws)

| MRONJ (N = 74, 75 jaws) | BRONJ and DRONJ (N = 74, 75 jaws) | |||

| BRONJ (N = 64,65 jaws) | DRONJ (N = 10) | Univariate P -value a | ||

| Mean age (y) | 76.4 | 77.5 | 69.3 | <0.01* |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 60 (81) | 55 (86) | 5 (50) | 0.017* |

| Male | 14 (19) | 9 (14) | 5 (50) | |

| Location | ||||

| Maxilla | 16 (21.3) | 12 (18) | 4 (40) | 0.21 |

| Mandible | 59 (78.7) | 53 (82) | 6 (60) | |

| Anterior | 8 (10.7) | 8 (12) | 0 | 0.052 |

| Posterior | 63 (84.0) | 55 (85) | 8 (80) | |

| Whole | 4 (5.3) | 2 (3) | 2 (20) | |

| Right | 32 (42.7) | 28 (43) | 4 (40) | 0.58 |

| Left | 35 (46.7) | 31 (48) | 4 (40) | |

| Bilateral | 8 (10.6) | 6 (9) | 2 (20) | |

| Internal texture | ||||

| Normal | 3 (4.0) | 2 (3) | 1 (10) | .50 |

| Sclerotic | 26 (34.7) | 22 (34) | 4 (40) | |

| Lytic and sclerotic | 46 (61.3) | 41 (63) | 5 (50) | |

| Sequestrum | ||||

| Present | 39 (52.0) | 35 (54) | 4 (40) | 0.51 |

| Absent | 36 (48.0) | 30 (46) | 6 (60) | |

| Sequestrum size | ||||

| Large (>20 mm) | 6 (15.4) | 3 (9) | 3 (75) | .008* |

| Small (<20 mm) | 33 (84.6) | 32 (91) | 1 (25) | |

| Periosteal reaction | ||||

| Present | 11 (14.7) | 7 (11) | 4 (40) | 0.035* |

| Absent | 64 (85.3) | 58 (89) | 6 (60) | |

| Cortical perforation | ||||

| Present | 43 (57.3) | 38 (58) | 5 (50) | 0.76 |

| Absent | 32 (42.7) | 27 (42) | 5 (50) | |

| Buccal | 17 (39.5) | 17 (45) | 0 | 0.15 |

| Lingual | 4 (9.3) | 3 (8) | 1 (20) | |

| Buccal and lingual | 22 (51.2) | 18 (47) | 4 (80) | |

| Soft tissue swelling | ||||

| Present | 60 (80.0) | 52 (80) | 8 (80) | 1.00 |

| Absent | 15 (20.0) | 13 (20) | 2 (20) | |

| Bone expansion | ||||

| Present | 25 (33.7) | 23 (35) | 2 (20) | 0.48 |

| Absent | 50 (66.7) | 42 (65) | 8 (80) | |

| Pathological fracture | ||||

| Present | 4 (5.3) | 4 (6) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Absent | 71 (94.7) | 61 (94) | 10 (100) | |

| Unilateral maxillary sinusitis adjacent to upper MRONJ | ||||

| Present | 16 (100) | 13 (100) | 3 (100) | – |

| Absent | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Note. Data are number of findings, percentages.

Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were used.

BRONJ, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaw; DRONJ, denosumab-related osteonecrosis of jaw; MRONJ, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw.

Figure 1.

A 72-year-old female diagnosed as BRONJ with clinical Stage 3. On axial and coronal CT in bone window setting (a, b), sclerotic and lytic lesion with sequestrum formation (arrows) was detected centered in the posterior part of right body of the mandible.

Figure 2.

A 72-year-old female diagnosed as BRONJ with clinical Stage 2. On axial CT in bone window setting (a), sclerotic and lytic lesion with relatively large sequestrum formation with buccal and lingual cortical bone perforation (arrows) was detected centered in the anterior part of left body of the mandible. On axial CT in soft tissue window setting (b), buccolingual soft tissue swelling (arrow heads) adjacent the sequestrum in the anterior part of left body of the mandible.

Figure 3.

A 69-year-old female diagnosed as BRONJ with clinical Stage 3. On axial and coronal CT in bone window setting (a, c), sclerotic and lytic lesion with relatively small sequestrum formation with buccal cortical bone perforation (arrow) was detected centered in the posterior part of left body of the mandible. On axial CT in soft tissue window setting (b), buccal soft tissue swelling (arrow head) in the floor of mouth (lingual) and along the anterolateral surface of the mandible (buccal).

Figure 4.

A 87-year-old female diagnosed as BRONJ with clinical Stage 2. On coronal CT in bone window setting, left unilateral maxillary sinusitis (M) with defect of inferior maxillary wall to sequestrum formation of left maxilla (arrow) was detected. This sinusitis was considered to be probably resulting from BRONJ of maxilla.

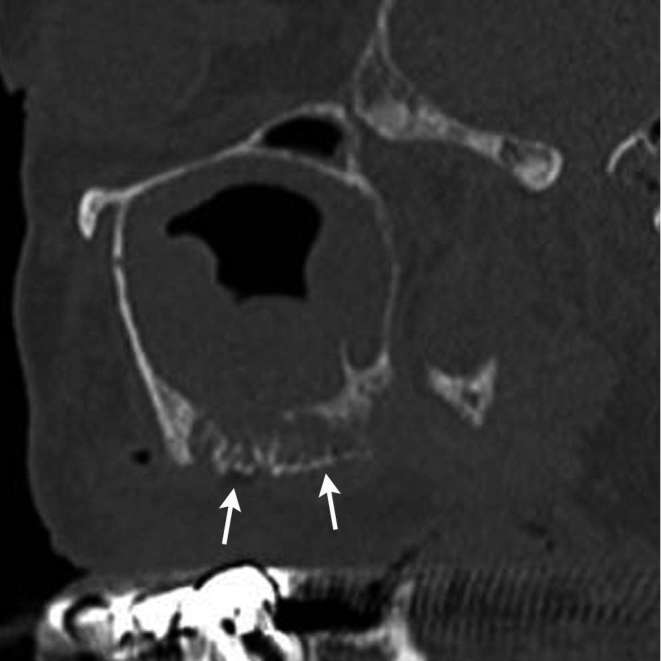

Comparison between BRONJ and DRONJ

Demographic characteristics and findings of patients with BRONJ and DRONJ are presented in Table 2. In univariate analyses, patients with BRONJ had a higher proportion of females than males (55/64, 86 vs 5/5, 50%, p < 0.05). Mean age of BRONJ was higher than that of DRONJ (77.5 vs 69.3%, p < 0.01). DRONJ showed larger sequestrum than BRONJ (3/4, 75 vs 3/35, 8.6%, p < 0.05) (Figure 5). DRONJ showed periosteal reaction more frequently than BRONJ (4/10, 40 vs 7/65, 10.1%, p < 0.05) (Figure 6). In multivariate analyses, there was no significant difference in factors that were statistically significant.

Figure 5.

A 76-year-old male diagnosed as DRONJ with clinical Stage 2. On sagittal CT in bone window setting, relatively large (2.2 cm) sequestrum (arrows) was detected in left maxilla with left unilateral maxillary sinusitis.

Figure 6.

A 78-year-old male diagnosed as DRONJ with clinical Stage 2. On axial CT in bone window setting, periosteal reaction (arrow) along the lingual cortical bone was detected.

Comparison between BRONJ resulting from oral bisphosphonate administration and intravenous administration

The findings are presented in Table 3. In univariate analyses, patients of BRONJ resulting from intravenous bisphosphonate administration showed larger and more frequent buccolingual cortical bone perforations than BRONJ resulting from oral bisphosphonate administration (7/8, 87.5 vs 11/30, 36.7%, p < 0.05) (Figure 7).

Table 3.

Findings of patients with BRONJ (oral bisphosphonate administration vs intravenous bisphosphonate administration)

| Characteristic | BRONJ (N = 64, 65 jaws) | ||

| Oral administration | Intravenous administration | Univariate P-valuea | |

| Mean age (y) | 71.8 | 79.6 | <0.01* |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 44 (94) | 11 (65) | <0.01* |

| Male | 3 (6) | 6 (35) | |

| Location | |||

| Maxilla | 7 (15) | 5 (29) | 0.27 |

| Mandible | 41 (85) | 12 (71) | |

| Anterior | 5 (11) | 3 (18) | 0.53 |

| Posterior | 41 (85) | 14 (82) | |

| Whole | 2 (4) | 0 | |

| Right | 21 (44) | 7 (41) | 0.91 |

| Left | 23 (48) | 8 (47) | |

| Bilateral | 4 (8) | 2 (12) | |

| Internal texture | |||

| Normal | 2 (4) | 0 | 0.13 |

| Sclerotic | 13 (27) | 9 (53) | |

| Lytic and sclerotic | 33 (69) | 8 (47) | |

| Sequestrum | |||

| Present | 28 (58) | 7 (41) | 0.26 |

| Absent | 20 (42) | 10 (59) | |

| Sequestrum size | |||

| Large (>20 mm) | 2 (7) | 1 (14) | 0.50 |

| Small (<20 mm) | 26 (93) | 6 (86) | |

| Periosteal reaction | |||

| Present | 4 (8) | 3 (18) | 0.37 |

| Absent | 44 (92) | 14 (82) | |

| Cortical perforation | |||

| Present | 30 (63) | 8 (47) | 0.39 |

| Absent | 18 (38) | 9 (53) | |

| Cortical perforation | |||

| Buccal | 17 (57) | 0 | 0.016* |

| Lingual | 2 (7) | 1 (13) | |

| Buccal and lingual | 11 (36) | 7 (87) | |

| Soft tissue swelling | |||

| Present | 41 (85) | 11 (65) | 0.08 |

| Absent | 7 (15) | 6 (35) | |

| Bone expansion | |||

| Present | 18 (37) | 5 (29) | 0.77 |

| Absent | 30 (63) | 12 (71) | |

| Pathological fracture | |||

| Present | 1 (2) | 3 (18) | 0.052 |

| Absent | 47 (98) | 14 (82) | |

| Unilateral maxillary sinusitis adjacent to upper MRONJ | |||

| Present | 8 (100) | 5 (100) | – |

| Absent | 0 | 0 | |

BRONJ, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaw. Data are number of findings, percentages.

Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test and χ2 test were used.

Figure 7.

A 66-year-old female diagnosed as BRONJ resulting from from intravenous bisphosphonate administration with clinical Stage 2. On coronal CT in bone window setting, focal buccal and lingual cortical bone perforation (arrows) of right mandible were detected.

Comparison among medications in BRONJ

In univariate analyses, there were no statistically significant differences among alendronate, zoledronate, risedronate nor minodronate in patients with BRONJ.

Comparison between BRONJ with long-term administration and short-term administration

In univariate analyses, there were no statistically significant differences between BRONJ with long-term (more than 4 years) administration and short-term (less than 4 years) administration.

Imaging features of BRONJ among different clinical stagings

In univariate analyses, there were no statistically significant differences among Stage 0,1 and 2,3 nor between 0 ~ 2 and 3 in patients with BRONJ.

Discussions

ARONJ/MRONJ, which we clinically encounter more and more recently in our institution, is a complication associated with antiresorptive medications used to manage osteoporosis/osteopenia and cancer-related conditions including skeletal related events. However, imaging findings of ARONJ/MRONJ are not specific and can also be similar to other conditions including inflammatory or tumoral lesion. Characteristic radiological features of ARONJ/MRONJ have not been fully investigated.

The MRONJ staging system recommended by AAOMS assigns patients to different stages based on clinical manifestations and does not include radiological evaluation.11 Nevertheless the clinical examination cannot usually show the disease extent and involvement of BRONJ beneath the mucosa.18, 19 Radiological examinations, especially with CT, have possibilities to better estimate the extent of the lesions.3, 19 PR serves as the baseline imaging and possibly depicts signs that may serve as predictors for the disease extent including sclerosis, thickening of the lamina dura, prominent mandibular canal, and delayed healing of extraction sockets.20 However, its sensitivity is lower than CT, particularly with regard to soft tissue swelling, periosteal new bone, and sequestrum as previously reported.13, 15 It has been reported that the detectability of ARONJ/MRONJ is 96% in CT compared with 54% in PR.17 Besides the high sensitivity, CT offers greater information on the extent of bone involvement with better precision than PR for observation of the ARONJ/MRONJ16, 19,21,22 Thus, in evaluation of ARONJ/MRONJ, the most adequate modality is considered CT.

Regarding the bone and the location involved in ARONJ/MRONJ in our study, the mandibular ARONJ/MRONJ was detected more frequently than maxillary ARONJ/MRONJ (78.7 vs 21.3%). This result was consistent with previous reports that mandibular ARONJ/MRONJ was the most frequently presented site (95%).4 When including all mandibular and maxillary ARONJ/MRONJ, posterior parts of the jaws were the more involved more (86%) than anterior. This report is the first report to mention its predominance of posterior involvement.

General CT findings characteristic of ARONJ/MRONJ were similar to those previously reported. Previous studies reported that the CT evaluation for ARONJ/MRONJ detected periosteal reaction, cortical perforation, periosteal bone deposition, mandibular fractures, and soft tissue inflammation.16 Our findings were that: most lesions were both lytic and sclerotic, about a half of the cases showed bony sequestrum, and sometimes they presented with soft tissue swelling. There were also other findings that had not been noted previously, though not statistically evaluated this time. These findings were the following. There was no predisposition for either side of the mandible among all ARONJ/MRONJ. Regarding the sequestrum size, sequestra were mostly small (some with periosteal reaction). Also, cortical bone perforation was seen in higher frequency in buccolingual or buccal cortical bone, compared with lingual cortical bone.

It should be noted that BRONJ tends to show thicker cortical bones and more sclerotic bone marrow, which could not be evaluated in our study. This finding is reported only with assessment using cone beam CT (CBCT).23, 24 CBCT is known to be more useful for measuring the mandibular cortical bone23 and other characteristic findings of BRONJ than PR.23, 25,26 We used only conventional CT in our study, and so we were unable to include thickness of cortical bone and degree of bone marrow sclerosis for findings of CT. CBCT has possibility to give additional information to conventional CT or PR.

As previously reported, ARONJ/MRONJ of the maxilla adjacent to the maxillary sinus is known to show mucoperiosteal thickening, air-fluid levels, and fistula formation.15, 19,27 Similar to those reports, maxillary sinusitis on the same side as ARONJ/MRONJ was detected in all patients of upper ARONJ/MRONJ (100%) in our study. The possible reason for high frequency of maxillary sinusitis involvement is anatomical bone thickness. The maxillary bone wall is thinner compared to the mandible bone, which may allow inflammation to spread. Thus, newly emerging signs of unilateral sinusitis with patients undergoing antiresorptive medications may alert the clinicians to suspect ARONJ/MRONJ.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no report that describes radiological features comparing BRONJ and DRONJ. Underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of these phenomena are still uncertain. In a previous study, the presence of expansive lytic lesions with a dense sequestrum resulting in a bone-within-bone appearance has been reported as the characteristic image findings of BRONJ.12 However, in our study, bone-within-bone appearances were found in both BRONJ and DRONJ. Interestingly, larger sequestrum was more common in DRONJ (3/4, 75 vs 3/35, 8.6%, p < 0.05). There has been a report that DRONJ tended to be detected in higher stage, such as Stage 2 and 328 which may be related to the sequestrum size. Difference of sequestrum formation between DRONJ and BRONJ might be affected by separation speed of bony sequestrum. Furthermore, DRONJ showed periosteal reaction more frequently than BRONJ (4/10, 40 vs 7/65, 10.1%, p < 0.05). Considering different periosteal reactions between DRONJ and BRONJ, drug distributions and pharmacokinetics might have some influences on the jaws in relative mechanisms. Although denosumab, compared with bisphosphonate, has significantly greater reductions in bone turnover markers, it does not accumulate on bones. It also has shorter half-life at 32 days maximum, rapid offset of action within 6 months and reversibility of its antiresorptive effect, and displays low-cytotoxicity or antiangiogenic profiles.29–32 In addition, Denosumab primarily inhibits remodeling-based bone formation and permits modeling-based bone formation whereas bisphosphonate tends to cease both pathways.33 This difference may make DRONJ more prone to advanced separation of necrotic bones from surrounding bony tissue and periosteal expansion. Further studies are needed in order to investigate the aetiology of these phenomena.

In our study, patients of BRONJ from intravenous bisphosphonate administration showed buccolingual cortical bone perforation more frequently than BRONJ with oral administration. Previous studies showed higher incidence rates of BRONJ with intravenous administration than with oral administration.3–6 Based on previous reports as well as our study, BRONJ resulting from intravenous bisphosphonate tended to show more progressive disease compared to those with oral bisphosphonate. The CT findings of buccolingual cortical perforation would be a characteristic for BRONJ with intravenous administration.

HAP (affinities for hydroxyapatite) adsorption affinity is different for bisphosphonate medications such as alendronate, zoledronate, risedronate and minodronate.34 It is likely that differences in HAP adsorption affinity influence imaging findings, however, according to our study, no significant statistical differences of CT findings along different BRONJ medications were observed.

Although BRONJ was more prevalent in patients who were under longer medication duration,10 no significant CT findings were noted in our study. The influence of medication duration may exist, but our study was inconclusive.

When focusing on relationship between radiological findings and clinical stages, studies in the past describe some correlations. One report says that Stage 0 and Stage 1 BRONJ patients tended to show osseous sclerosis, Stage 2 patients periosteal reaction and cortical bone perforation, and Stage 3 patients mandibular fractures in addition to all other findings.16 It has also been described that early-stage BRONJ may present predominantly osteolytic lesions with cortical bone destruction.14 On the other hand, progressed BRONJ may present with increased bone density, periosteal reactions, and bone sequestrations.15, 19 However, according to our study, no significant statistical differences of CT findings along different BRONJ stages were observed. Compared to our study, the size of the previous study was rather small and no statistical evaluation was performed.14–16,19 This discrepancy suggests that it is possible that there are only weak relationships exist between specific CT findings and BRONJ clinical staging.

Regardless, Franco et al proposed a new way to assess the therapeutic strategy of ARONJ/MRONJ, called a “dimensional staging,” which includes radiographic findings in addition to clinical findings. His retrospective follow-up study of 266 surgically-treated ARONJ/MRONJ lesions accordingly showed low recurrence rates and surgical sites stabilities.35 Using the same dimensional staging, Favia et al also reported similar clinical outcomes with low recurrence rates and surgical site stabilities.28 In terms of assessing the therapeutic strategy, CT findings could be a vital tool for better clinical outcomes.

Our study limitations include the relatively small size of the study, as well as demographic limitation. Though the conditions are relatively rare in clinical setting, larger studies would be needed to confirm our results. Since our study was limited to Japanese population, potential genetic component could not be eliminated, especially when considering metabolization of the drugs. Further studies are needed to clarify these components.

Conclusion

We investigated ARONJ/MRONJ findings on conventional CT, which can be considered as a standard modality to evaluate the extent of the disease, and analyzed the findings statistically. In particular, this is the first study to show imaging findings of DRONJ in comparison to BRONJ. We found novel findings regarding ARONJ/MRONJ imaging features. These characteristics may serve as a useful aid for assessing ARONJ/MRONJ.

REFERENCES

- 1. Drake MT, Clarke BL, Khosla S. Bisphosphonates: mechanism of action and role in clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83: 1032–45. doi: 10.4065/83.9.1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reid IR, Cundy T. Osteonecrosis of the jaw. Skeletal Radiol 2009; 38: 5–9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0549-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leite AF, Ogata FS, de Melo NS, Figueiredo PT. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a critical review of the quantitative studies. Int J Dent 2014; 2014: 1–11. doi: 10.1155/2014/784348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Huang YF, Chang CT, Muo CH, Tsai CH, Shen YF, Wu CZ. Impact of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw on osteoporotic patients after dental extraction: a population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0120756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, Broumand V. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63: 1567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lam DK, Sándor GK, Holmes HI, Evans AW, Clokie CM. A review of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws and its management. J Can Dent Assoc 2007; 73: 417–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aghaloo TL, Felsenfeld AL, Tetradis S. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient on Denosumab. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68: 959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stopeck AT, Lipton A, Body JJ, Steger GG, Tonkin K, de Boer RH, et al. Denosumab compared with zoledronic acid for the treatment of bone metastases in patients with advanced breast cancer: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 5132–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.7101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fusco V, Galassi C, Berruti A, Ciuffreda L, Ortega C, Ciccone G, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw after zoledronic acid and denosumab treatment. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: e521–e522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.1551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yoneda T, Hagino H, Sugimoto T, Ohta H, Takahashi S, Soen S, et al. Antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Position Paper 2017 of the Japanese Allied Committee on Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. J Bone Miner Metab 2017; 35: 6–19. doi: 10.1007/s00774-016-0810-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruggiero SL, Dodson TB, Fantasia J, Goodday R, Aghaloo T, Mehrotra B, et al. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw--2014 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014; 72: 1938–56. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2014.04.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fatterpekar GM, Emmrich JV, Eloy JA, Aggarwal A. Bone-within-bone appearance: a red flag for biphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2011; 35: 553–6. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318227a81d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Phal PM, Myall RW, Assael LA, Weissman JL. Imaging findings of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 1139–45. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bisdas S, Chambron Pinho N, Smolarz A, Sader R, Vogl TJ, Mack MG. Biphosphonate-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws: CT and MRI spectrum of findings in 32 patients. Clin Radiol 2008; 63: 71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bianchi SD, Scoletta M, Cassione FB, Migliaretti G, Mozzati M. Computerized tomographic findings in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007; 104: 249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guo Y, Wang D, Wang Y, Peng X, Guo C. Imaging features of medicine-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: comparison between panoramic radiography and computed tomography. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016; 122: e69–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stockmann P, Hinkmann FM, Lell MM, Fenner M, Vairaktaris E, Neukam FW, et al. Panoramic radiograph, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. Which imaging technique should be preferred in bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw? A prospective clinical study. Clin Oral Investig 2010; 14: 311–7. doi: 10.1007/s00784-009-0293-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wilde F, Heufelder M, Lorenz K, Liese S, Liese J, Helmrich J, et al. Prevalence of cone beam computed tomography imaging findings according to the clinical stage of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 114: 804–11. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2012.08.458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bedogni A, Blandamura S, Lokmic Z, Palumbo C, Ragazzo M, Ferrari F, et al. Bisphosphonate-associated jawbone osteonecrosis: a correlation between imaging techniques and histopathology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008; 105: 358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klingelhöffer C, Klingelhöffer M, Müller S, Ettl T, Wahlmann U. Can dental panoramic radiographic findings serve as indicators for the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw? Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2016; 45: 20160065. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiandussi S, Biasotto M, Dore F, Cavalli F, Cova MA, Di Lenarda R. Clinical and diagnostic imaging of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaws. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2006; 35: 236–43. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/27458726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleisher KE, Welch G, Kottal S, Craig RG, Saxena D, Glickman RS. Predicting risk for bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: CTX versus radiographic markers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010; 110: 509–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Torres SR, Chen CS, Leroux BG, Lee PP, Hollender LG, Santos EC, et al. Mandibular cortical bone evaluation on cone beam computed tomography images of patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2012; 113: 695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2011.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ozcan G, Sekerci AE, Gönen ZB. Are there any differences in mandibular morphology of patients with bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of jaws?: a case-control study. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2016; 1: 20160047l. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20160047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kämmerer PW, Thiem D, Eisenbeiß C, Dau M, Schulze RK, Al-Nawas B, et al. Surgical evaluation of panoramic radiography and cone beam computed tomography for therapy planning of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2016; 121: 419–24. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Demir A, Pekiner FN. Radiographic findings of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Comparison with cone-beam computed tomography and panoramic radiography. Niger J Clin Pract 2017; 20: 346–54. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.183241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Raje N, Woo SB, Hande K, Yap JT, Richardson PG, Vallet S, et al. Clinical, radiographic, and biochemical characterization of multiple myeloma patients with osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 2387–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Favia G, Tempesta A, Limongelli L, Crincoli V, Maiorano E. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: considerations on a new antiresorptive therapy (Denosumab) and treatment outcome after a 13-year experience. Int J Dent 2016; 2016: 1–9. doi: 10.1155/2016/1801676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silva I, Branco JC. Denosumab: recent update in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Acta Reumatol Port 2012; 37: 302–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gallacher SJ, Dixon T. Impact of treatments for postmenopausal osteoporosis (bisphosphonates, parathyroid hormone, strontium ranelate, and denosumab) on bone quality: a systematic review. Calcif Tissue Int 2010; 87: 469–84. doi: 10.1007/s00223-010-9420-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aghaloo T, Hazboun R, Tetradis S. Pathophysiology of osteonecrosis of the jaws. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2015; 27: 489–96. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allen MR. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: basic and translational science updates. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am 2015; 27: 497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langdahl B, Ferrari S, Dempster DW. Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2016; 8: 225–35. doi: 10.1177/1759720X16670154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nancollas GH, Tang R, Phipps RJ, Henneman Z, Gulde S, Wu W, et al. Novel insights into actions of bisphosphonates on bone: differences in interactions with hydroxyapatite. Bone 2006; 38: 617–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Franco S, Miccoli S, Limongelli L, Tempesta A, Favia G, Maiorano E, et al. New dimensional staging of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw allowing a guided surgical treatment protocol: long-term follow-up of 266 lesions in neoplastic and osteoporotic patients from the university of bari. Int J Dent 2014; 2014: 1–10. doi: 10.1155/2014/935657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]