Abstract

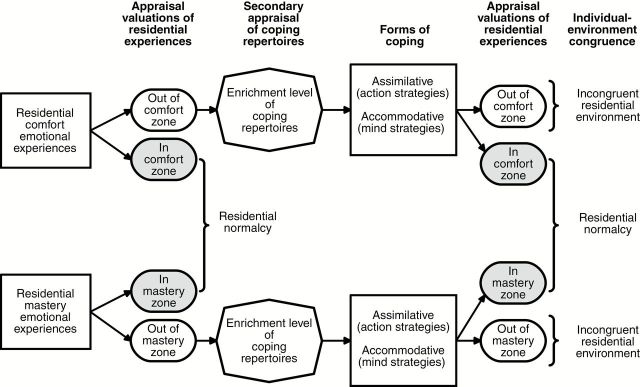

An earlier theoretical model equated the construct of residential normalcy with older persons positively appraising their residential environments. Failing to achieve congruent places to live, they initiate assimilative (action) or accommodative (mind) coping strategies. This paper theorizes that the assimilative coping strategies of older persons depend on their secondary appraisal processes whereby they judge the availability, efficaciousness, and viability of their coping options. Older persons with more enriched coping repertoires are theorized as more resilient, making their own decisions, and with access to more resource-rich objectively defined resilient environments. Successful aging formulations infrequently examine how residential environmental adaptations of people influence the quality of their lives. Programmatically, the theory emphasizes the potential of individual and environmental interventions targeting older persons who are not aging successfully.

Key words: Environmental gerontology, Resiliency, Residential relocation, Subjective experiences, Quality of life

This paper outlines a theoretical model that predicts why older occupants of incongruent residential environments cope differently with their unmet needs and goals. It extends an earlier model of residential normalcy that explained how older persons differently judged the appropriateness of where they lived and specified their coping responses (Golant, 2011b). Successful aging formulations infrequently examine how the adaptations made by older persons to their residential environments influence the quality of their lives (Depp & Jeste, 2006; Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, Rose, & Cartwright, 2010). This is exemplified by the frequently cited “New Gerontology” paradigm of Rowe and Kahn (1998) that focuses on a toolbox of predictive individual indicators such as physical health, cognitive functioning, and level of activity.

This limited perspective ignores a large body of research by environmental gerontologists, architects, sociologists, and health care professionals who have linked the physical and psychological well-being, engagement in life, and independence of older persons to the features of their residential and care environments (Golant, 2011a; Moore & Ekerdt, 2011). The mission of environmental gerontology particularly focuses on the fit or congruence between aging persons and their physical–social environments and how to optimize them (Scheidt & Windley, 2006; Wahl, Iwarsson, & Oswald, 2012). Similarly, for many occupational therapists and sociologists, the functional limitations of older persons are only construed as disabilities when their dwellings lack compensatory design modifications or when mediating social supports are absent (Iwarsson et al., 2007; Nygren et al., 2007; Verbrugge & Jette, 1994).

Earlier Theory of Residential Normalcy

Any formulation of how environments influence individual well-being must inevitably incorporate the perspective of at least one of two worldviews. The first encompasses the objective indicators of environmental quality typically constructed and relied on by professionals, academics, and policy makers and that recognizes an empirical reality independent of thinking and perceiving older individuals (Golant, 1998). The second encompasses the subjective residential assessments—the voices or reported self-ratings—of older people (Löfqvist et al., 2013; Wahl et al., 2012).

Successful aging formulations have also had to choose between these orientations (Strawbridge, Wallhagen, & Cohen, 2002), and for the most part have emphasized objective indicators of individual status and functioning as opposed to “older adults’ self-rated successful aging” (Jeste et al., 2013, p. 188). Critics, however, have characterized such approaches as unnecessarily limiting (Pruchno et al., 2010; Villar, 2012) because research shows that older persons with limited physical or cognitive functioning or with chronic diseases often are satisfied with their lives and express a positive well-being (von Faber et al., 2001).

My earlier emotion-based theory of residential normalcy recognized both worldviews (Golant, 2011b, 2012). Although it focused on the subjective residential experiences of older persons, it also conceptualized an objectively defined residential environment with the potential of “evoking, reinforcing, or modifying” their behaviors and experiences. It assumed, however, “that older adults will not have the same encyclopedic awareness and knowledge of their residential setting’s contents, nor the same motivations, capabilities, or confidence to use, manipulate, or interact with their features and attributes” (Golant, 2011b, p. 195).

The model distinguished two broad and relatively independent categories of emotional experiences. The first, residential comfort experiences represented older persons’ subjective appraisals of whether they felt their places of residence were pleasurable (e.g., enjoyable, appealing, stimulating), hassle-free (i.e., free of problems), and memorable; and the second, residential mastery experiences represented their subjective appraisals of whether they felt competent and in control when occupying their places of residence. When older persons appraised these two sets of salient feelings as altogether positive, the model conceptualized them as being squarely in their residential comfort and residential mastery zones and occupying places where they had achieved residential normalcy.

Coping Strategies to Achieve Residential Normalcy

The theory argued that when older persons confront incongruent residential environments, they do not passively sit back and accept their unfortunate fates (Holahan, 1978; Wahl et al., 2012). Rather, they take proactive steps to engage and influence their environments in order to change their undesirable circumstances and to put them on “a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation” (Wild, Wiles, & Allen, 2013, p. 130). The now classic environmental press model of Lawton and Nahemow (1973) similarly linked individual-environment congruence to the adaptive behaviors of older adults and their efforts to optimize their affective responses. Human development and life course theorists have also long emphasized the importance of such adaptive strategies for successfully aging older persons to optimize their experiences, maintain their level of activities, and cope with their declines and losses (Baltes & Carstensen, 1996; Heckhausen, 1997; Magai, 2001; Steverink, Lindenberg, & Ormal, 1998). And Rowe and Kahn (1998, p. 102) argued it was never too late for older persons to pursue a pathway to successful aging because the “frailty of old age is largely reversible.”

The residential normalcy theory specifically proposed that when older persons find themselves out of their residential comfort and/or mastery zones, they initiate accommodative and/or assimilative forms of coping (Brandtstadter & Greve, 1994). Accommodative adaptive responses (or secondary control) refer to mind strategies whereby older persons deal with their negative appraisals by lowering their environmental expectations or aspirations, de-emphasizing their salience, or variously rationalizing that their incongruent residential arrangements are not that important for their self-esteem, self-identity, or happiness. Assimilative (or primary control) adaptive responses, on the other hand, refer to action strategies, whereby older persons change how they occupy or use their residential environments and eliminate or change their incompatible content or features.

Theorists have usually equated aging successfully with the initiation of assimilative coping responses (Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010; Schulz & Heckhausen, 1996). Older persons rely more heavily on accommodative coping strategies when they feel overwhelmed with their problems and cannot eliminate them.

Extending the Residential Normalcy Theory

This earlier theoretical framework left largely unspecified how older persons decide on their assimilative coping responses, that is, “what might and can be done” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 35). To fill this void, this paper outlines a theoretical framework that explains why older people are differently motivated and vary in their abilities to cope successfully with their inappropriate circumstances—that is, when they are out of their residential comfort and/or mastery zones.

The proposed theoretical model makes two major contributions: first, it will help frame the empirical research of academic researchers, thereby enabling them to explain and predict more completely and accurately why older people differently cope (some more successfully than others) with their incongruent residential settings; and, second, it will inform planners, practitioners, policy makers, and philanthropists about how older people make their coping decisions and thus better prepare them to introduce solutions that will change or eliminate their incongruent residential environments.

Secondary Appraisal of Individual Coping Repertoires

The theory proposes that how well older persons cope with their incongruent residential environments depends on how they subjectively appraise their coping opportunities or repertoires (Figure 1). The assumption that this is an interactional process is important. Different older persons can appraise the very same objectively depicted environments as having both bountiful and meager coping solutions (Wild et al., 2013). As Lazarus and Folkman (1984, p, 47) aptly put it: “private ways of thinking [may have] no necessary relationship with objective reality.”

Figure 1.

Extended theoretical model of residential normalcy.

Older people will have more enriched coping repertoires when they are aware of coping strategies that they believe are more efficacious (leading to successful outcomes) and viable (doable or implementable) (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). When they engage in this secondary appraisal decision-making process, they perform several conceptually distinguishable perceptual and cognitive operations that in practice, however, may not be so neatly separable or clearly temporally sequenced (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Subjective Appraisal of the Resiliency of Places

Older persons initially must subjectively appraise the availability of their options, that is, the solutions that are out there. They must scan not only the contents of their current places of residence, but also the options found in possible alternative residential destinations, to identify alternative courses of action to achieve their goals and needs (Heckhausen et al., 2010). More formally, they must appraise the adaptive capacities or resiliency of these places to find ways to rectify or manage their incongruent residential settings.

Efficaciousness of Coping Solutions

“Spotting all the things that might be done,” or searching for available and relevant environmental information, however, is but the first step of “a complex evaluative process” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 35). Older persons must next assess which of their potential coping solutions will best manage or successfully resolve their incongruent environments.

These coping strategies might resolve some discordant environmental aspects, but not others; in some places, they may be ideal, and in others, inferior choices (Masten & Wright, 2010). These appraisals will depend on the number, enormity, and complexity of their problems. Some coping efforts may only have to resolve simple or less demanding residential difficulties. However, more complex or multifaceted solutions will be necessary when older persons feel that many different and salient aspects of their environments are contributing to their incongruous feelings (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Masten & Wright, 2010).

The appropriateness of their coping responses will also depend on whether they are consistent with the temporal immediacy (or urgency) and permanence of their unattainable goals. They must deliberate on whether they can implement their possible solutions quickly enough and whether these will constitute temporary or permanent fixes. This requires them to assess the likely duration and temporal trajectory of their incongruent environmental statuses (Golant, 2003; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). They must assess whether in the absence of adaptive behaviors, they will experience their adverse outcomes only for a short period or over the long term, and whether these consequences will occur quickly, slowly, or plateau for a substantive period and then worsen abruptly.

The challenging appraisal tasks of older persons diagnosed with early stage Alzheimer’s disease illustrate these issues. They must decide how soon they must relocate to a more supportive residential/care environment and whether this prospective place will sustain them over the long term when their disease symptoms worsen. Similarly, consider the appraisal process of an older occupant of an independent living unit in a continuing care retirement community (CCRC). After her hip replacement, she must decide on the desirability of an otherwise disagreeable nursing home admission, given her expectations that she will only have to remain in this facility for a short period to receive rehabilitation services, after which she can return to her original accommodation. On the other hand, the coping deliberations of older persons seeking compatible places to enjoy their leisure-oriented retirement years will lack the urgency of the previous two examples and if unhappy with their new residential arrangements, they can return to their original homes.

Viability of Coping Solutions

Older persons must assess not just whether their possible coping strategies will yield efficacious or successful residential outcomes, but the extent to which they are viable or doable, that is, whether they have the physical, psychological, and financial abilities or other relevant demographics to implement their selected coping strategies (Bandura, 1982; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). All assimilative coping solutions have implementation costs and usability barriers, which we can characterize as collateral damages—and that are mostly unrelated to their actual expected outcomes.

The implementation costs of pursuing some otherwise appropriate coping strategies may be too great (Bandura, 1982). Challenging application procedures to obtain government-financed home care may be too stressful for some older people to complete. They may discount some solutions because they constitute too radical a change in their lives (Löfqvist et al., 2013). Moving to another address, for example, may allow older persons to feel once again in their residential comfort and/or mastery zones (Perry, Andersen, & Kaplan, 2013). However, they may appraise the act of relocation itself as too psychologically and physically exhausting and financially expensive (Golant, 2003, 2011b; Lieberman, 1991; Schulz & Brenner, 1977; Sergeant, Ekerdt, & Chapin, 2010).

Similarly, even as older persons believe that recommended home modifications will reduce their likelihood of falling, they may be unable to tolerate the physical mess or the anxiety of having unknown hired workers in their houses. The prospects of hiring a minority worker as a live-in caregiver may also be too high a barrier for some prejudiced White older persons to overcome—despite all the agreed-upon benefits of such a person.

Carstensten’s socioemotional selectivity of aging theory offers another interpretation. At higher chronological ages, older persons feel closer to death whereupon they decide that the time left to benefit from their coping adaptations is too short for them to tolerate or absorb their implementation costs (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999).

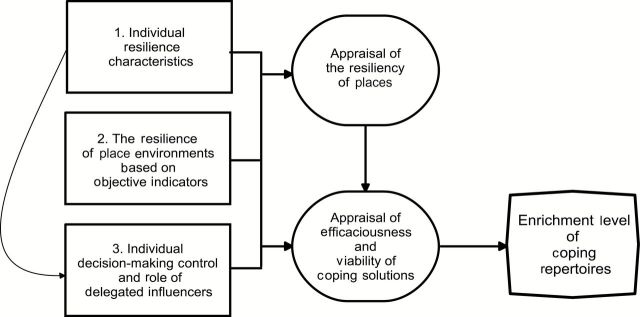

Individual and Environmental Influences of Enriched Coping Repertoires

We theorize that three sets of individual and environmental factors will influence how older persons appraise the resiliency of their residential places and the efficaciousness and viability of their alternative coping solutions (Figure 2). Specifically, the extent that older persons have enriched coping repertoires will depend on the following:

Figure 2.

Factors influencing secondary appraisals of coping repertoires by older adults.

Whether they have resilient characteristics;

Whether their current or alternative places of residence have resilient environments based on objective indicators; and

Whether they make decisions of their own volition or if they have voluntarily delegated their decision-making authority to others.

Resilient Individuals

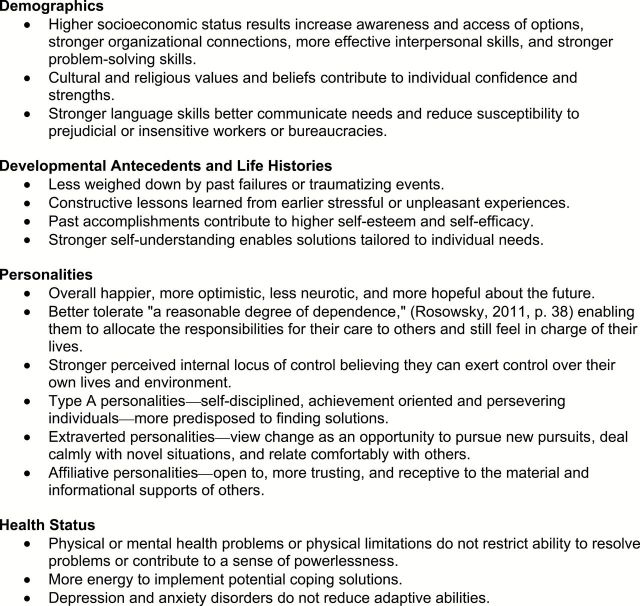

Resilient older persons will be more motivated and able (Heckhausen et al., 2010) to find creative and constructive goal-attainment adaptive strategies (Zautra, Hall, & Murray, 2010). They will have stronger problem-solving skills enabling them to find ways around even their major environmental difficulties and better tolerate the collateral costs of various coping strategies. We can distinguish four sets of predictive personal characteristics (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The characteristics of resilient older persons. (Aldwin & Igarashi, 2012; Pargament & Cummings, 2010; Rosowsky, 2011; Skodol, 2010; Zautra et al., 2010).

Favorable Demographics

Higher income older persons will be able to afford products and services that will enable them to age in place and compensate for their functional declines. Better educated and English-speaking older persons will likely have more complete and accurate “what’s out there” and “how to access” information informing them of possible solutions (Finkelstein, Garcia, Netherland, & Walker, 2008). They will be more aware that they can develop new social relationships or obtain nutritious meals in a nearby senior center. On the other hand, the cultural and religious backgrounds of older persons may instill in them greater confidence and inner strength to implement their solutions.

Favorable Developmental Antecedents and Life Histories

Older persons with more enriched coping repertoires will have developmental and life histories that have better prepared them emotionally, materially, and informationally to remedy their stressful or incompatible events or circumstances. Because of more positive life experiences and successful past coping efforts, they have higher self-esteem (they believe in themselves), self-understanding (they are aware of their strengths and limitations), and are more confident in their coping abilities.

Favorable Personalities

Individuals with certain personality traits will be more motivated and capable of finding efficacious and viable coping solutions. They are more hopeful, confident, and optimistic about the efficacy of their coping strategies (Skodol, 2010). When they have more affiliative personalities, they will have stronger interpersonal communication skills enabling them relate better to both individuals and organizations offering possible solutions (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Wild et al., 2013). Those with internal locus of control traits will feel they can personally overcome their adversities. Similarly, more extraverted and persevering individuals will have more flexible coping styles or plasticity and will not be afraid to try out new goal-attainment strategies (Skodol, 2010).

Favorable Physical and Mental Health Status

More resilient older persons are less likely to suffer from debilitating physical or psychological health problems or functional declines. They have the physical and mental prowess and stamina to identify, access, and benefit from solutions offered by their places of residence (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). They will judge the collateral costs of their coping actions as less constraining.

Resilient Residential Environments Based on Objective Indicators

Physical Anatomy of Resilient Places

The coping repertoire appraisals of older persons also depend on whether they live in or are considering new places that offer potential solutions to their problems. The most resilient older persons cannot conjure up public transit alternatives, affordable rental housing, or pharmacies within walking distance, where none exists. Even the most motivated and capable older persons may find their coping alternatives are limited in an economically disadvantaged and isolated rural community.

Ecologically, we can distinguish these places of residence by their resiliency, that is, the extent to which their environments have adapted to the realities of their aging populations. More resilient places offer older persons living in incongruent environments more opportunities and resources (and fewer barriers and constraints) to rectify the reasons for why they are out of their residential comfort or mastery zones (Davoudi, 2012; Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010).

Multiple taxonomies are available to depict the resiliency of older people’s residential environments (Scheidt & Windley, 2006; Wahl et al., 2012). These frameworks often encompass the variable qualities of older people’s care settings because the places they call home and receive health and supportive services are often the same and the boundaries that separate residential and care attributes and activities have become blurred (Golant, 2008).

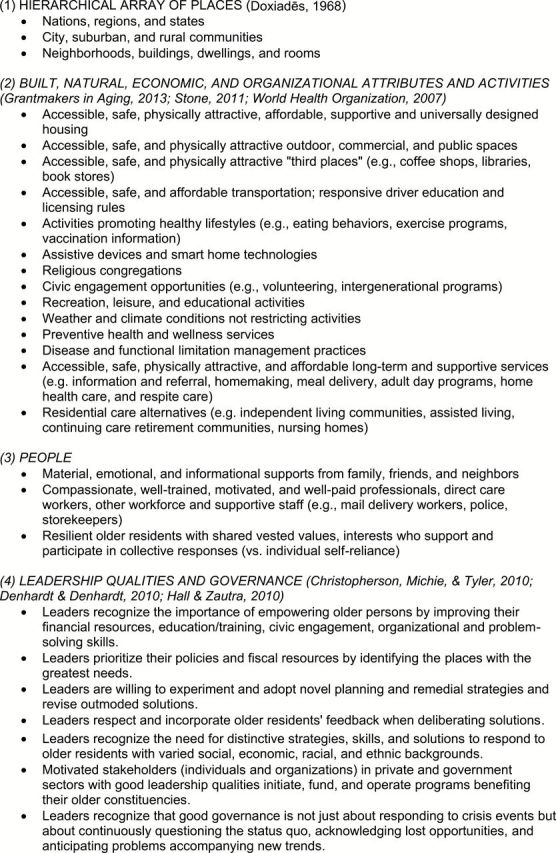

We distinguish a hierarchically defined array of places ranging from nations to rooms (Doxiadēs, 1968), each variously described by three broad categories of indicators (Figure 4): Built, natural, economic, and organizational attributes and activities; People; and Leadership qualities and governance. The residential and care quality indicators designated in these categories are very similar to those typically found in age-friendly community classifications (Grantmakers in Aging, 2013; World Health Organization [WHO], 2007).

Figure 4.

Opportunities and resources of resilient places.

Place Resilience Varies

Some residential areas will offer older people more opportunities to enjoy pleasurable and stimulating leisure, recreation, or volunteering activities (Hall & Zautra, 2010). Here universities will offer adult education opportunities or intellectually inspiring lectures or organized outside activities. In other places, older persons will have more opportunities to pursue emotionally rewarding social relationships with others of their own age or with their married children and their grandchildren.

Some communities will offer assistance or services for older persons seeking to cope with their declining physical prowess who want to feel more competent and in control. In distant locations may be found family members—the bedrock of our long-term care network—who can help older persons (sometimes referred to as “return migrants”) maintain their independent households (Stoller & Longino, 2001). Neighborhoods—attractive to lower income old—will offer affordable health and supportive services staffed by trained and well-compensated direct care workers (Stone, 2011). States with driver education programs (Marottoli & Coughlin, 2011) may appeal to those older adults having difficulty driving their vehicles. Some neighborhoods will have public transit stops located within a short distance of their dwellings.

These resilient places will not be ubiquitously located. Older persons have unequal access to opportunities and resources to resolve their incongruent residential or care arrangements (Zautra et al., 2010). Additionally, there will be historical variations—or period effects—influencing the resiliency of places, coinciding with changing social, economic, and political events and circumstances. During the great United States recession of 2005–2007, for example, a stagnant housing market prevented large numbers of older homeowners from selling or moving from their dwellings, irrespective of where they lived. On the other hand, some historical happenings will be place-specific. During this past decade, a few U.S. urban and rural places with strong leaderships initiated policies designed to make their communities age-friendly to their older constituencies (Golant, 2014; WHO, 2007).

Less resilient older persons who occupy the most incongruent residential environments (e.g., very unaffordable or physically deficient dwellings; or extremely unsafe neighborhoods) stand to gain or lose the most by whether they occupy resilient places of residence. Whereas more motivated and capable (i.e., the more resilient) older persons may discern coping solutions in even resource-poor settings, those with weaker coping skills (i.e., the less resilient) will have difficulties finding relief in such places. They require access to more resilient places to find solutions. This leads to the following Environmental Resiliency proposition: Unequal levels of place resiliency will account for more variation in the coping repertoires of less resilient older persons.

Decision-Making Control and Role of Influencers

The coping repertoires of older persons will depend on whether they are making their own residential or care decisions or if others have usurped this responsibility against their will. Typical scenarios include the adult daughter taking away the car keys of her father or coercing her 85-year-old mother to transition on short notice to her home, an assisted living property or to a nursing home (Bekhet, Zauszniewski, & Nakhla, 2009; Schulz & Brenner, 1977). It is theorized that older persons who are more resilient will be less likely to relinquish their decision-making authority, although empirical evidence for this proposition is limited (Ball, Perkins, Hollingsworth, Whittington, & King, 2009).

The gerontology and adult development literature offers strong theoretical and empirical arguments for expecting that older persons who are not deliberating on their own coping repertoires will negatively assess their coping outcomes (Langer & Abelson, 1983; Lieberman, 1991). They feel that others have “unfairly taken over” their lives (Morgan & Brazda, 2013, p. 663), they are being “punished or dumped” (Bekhet et al., 2009, p. 464), and they can no longer “shape or influence a particularly stressful person-environment relationship” (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984, p. 69). These persons are more likely to experience declines in their physical health, unhappiness, lower life satisfaction, fearfulness, a sense of hopelessness, frustration, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and a strong sense of loss (Langer & Abelson, 1983; Luborsky, Lysack, & Van Nuil, 2011).

There is much less study of older persons who have lost some but not all control over their residential or care decisions or who have willingly delegated or given up this authority to other persons, what one study refers to as “proxy control” (Morgan & Brazda, 2013, p. 655). These influencers can variously include not only family, friends, or other informal significant others, but also housing, health care, social worker, and long-term care professionals, financial advisors, clergy, work colleagues, or other formal significant others. In these instances, older persons trust their influencers, welcome their counsel, believe they are more knowledgeable than themselves, and will act in their best interests (Ball et al., 2009; Morgan & Brazda, 2013).

These older persons spare themselves from making otherwise traumatic and possibly bad decisions (Janssen, Abma, & Van Regenmortel, 2012). Surrendering this responsibility to others—and conceding their vulnerability and inability to make decisions on their own—may thus be a source of great emotional relief. Moreover, because they have actively participated in the transfer of decision-making control, that is, have exercised agency, they are less likely to feel a sense of reduced efficacy (Morgan & Brazda, 2013; Wahl et al., 2012). The opinions, beliefs, and actions of these influencers will arguably shape how these older persons subjectively appraise their coping repertoires and the outcomes of their coping efforts (Gubrium, Rittman, Williams, Young, & Boylstein, 2003).

Coping Repertoires and Residential Normalcy

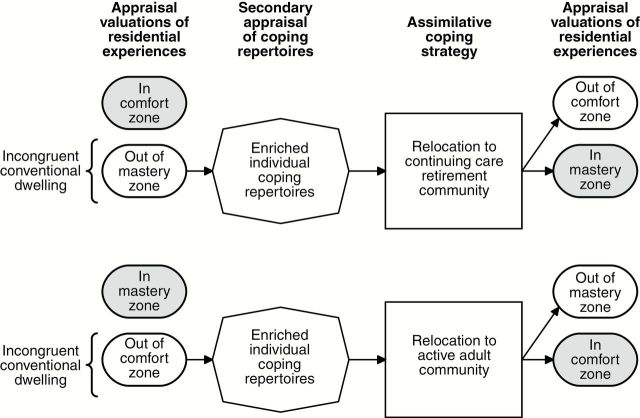

Enriched Coping Repertoires, Assimilative Coping Strategies, but Elusive Normalcy

The appraisals of older persons of their coping repertoires are usually not momentary events but rather occur over weeks, months, and even years. Moreover, these ongoing coping behavior deliberations are an uneven and a messy process because their environmental needs and goals are continually in flux and they are continually accumulating and evaluating information (both relevant and irrelevant and both correct and incorrect) about their adaptive behavior possibilities. There are also no guarantees that their selected assimilative coping strategies will yield successful outcomes. Even older persons with enriched coping repertoires may not have accurately judged the implementation costs or outcomes of their adaptive behaviors.

More perversely, even as older persons cope successfully with their appraised incongruent residential settings, their adaptive responses may unintentionally yield new negative residential experiences. Figure 5 offers two exemplars. In the top scenario, an older couple initially enjoys living in their dwelling and community and feel in their residential comfort zones. However, they are no longer able to drive and their suburban neighborhood makes it difficult for them to access their usual stores and services. Unable to maintain competently their independent lifestyles, they feel out of their residential mastery zones. They move to a well-operated CCRC—into its independent living unit section. Here, no longer having to worry about performing their instrumental activities of daily living, they feel once again in their residential mastery zones. Still, they miss badly their previous neighborhoods (filled with memories), their familiar restaurants, good friends, and attending their church. They also do not get along with some of the other CCRC residents. Now in their new environs, they (newly) feel out of their residential comfort zones.

Figure 5.

Incongruent environments resulting from “successful” coping strategies.

In the bottom scenario, an older couple can freely come and go in their residential subdivision, decide whether they participate in their religious congregation’s planned activities, and overall are very much in control of their lifestyles. Consequently, they feel in their residential mastery zones. However, they cannot find enjoyable and stimulating activities in their community that are compatible with their new retirement lifestyle and consequently feel out of their residential comfort zones. They cope by relocating to an active adult community where they find an abundance of leisure and recreational activities that enable them to feel once again in their residential comfort zones. However, the management of their new planned community imposes a great many restrictions on how they must maintain their dwellings and yards. They also are upset because both staff and other residents are continually channeling them into certain activities. Feeling others are unduly dictating how they must conduct their lifestyles, they feel out of their residential mastery zones.

Bouncing Back and the New Normal

The resiliency literature often characterizes individuals or communities as bouncing back from adversity. The residential normalcy theory also proposes that older persons can successfully alleviate undesirable individual or environmental outcomes. However, it argues that even the most successful adaptations may not result in older persons bouncing back or returning to their original equilibrium position. Being resilient implies the opposite of stability because individuals are engaging in a “process of continual adjustment” (Pendall, Foster, & Cowell, 2010, p. 76) and they do not return to their “previous state (like a rubber ball) but can actually adapt, learn, and change” (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2010, p. 335).

Consequently, after implementing their successful coping strategies, older individuals experience a “new normal” set of congruent residential feelings. They do not necessarily replace lost activities, re-establish the integrity of a past residential setting, or maintain the continuity of their past lives or environments. They end up in residential or care settings and conducting activities different from their pasts (Davoudi, 2012). Consider the coping solutions of the recently widowed woman who was feeling alone, bored, and financially stressed paying off her mortgage. She joins a book club, volunteers at a nearby church, and rents out her basement to a boarder. This does not bring back her husband, his companionship, his financial resources, or their previous lifestyle. The widow’s residential normalcy now has some obviously different underpinnings even as she now feels more useful, socially connected, and financially independent.

Consider also the older person who has experienced a mild stroke that prevents his golf and tennis activities and the major basis for his past enjoyable lifestyle. He adapts by having parties and card games in his own dwelling and becoming more involved in his condominium association management. He is now squarely back in his residential comfort zone—and is practicing a full and active lifestyle—but one substantially different from his past.

Conclusion

Strongly influenced by the environmental press model (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973), many studies have investigated how individual and environmental factors and their interaction effects account for why older people variously occupy congruent environments at any point in time (Golant, 2011a; Scheidt & Windley, 2006; Wahl et al., 2012). The theoretical model outlined in this paper has a different starting point. It focuses on older persons who feel they now occupy incongruent places—they are variously out of their residential comfort and/or mastery zones. It explains why over time these older persons adapt differently to their inappropriate circumstances by scrutinizing their secondary appraisal decision-making efforts, whereby they assess the viability and efficaciousness of their available coping strategies. Individual and environmental differences (and their interaction effects) again matter, but not to explain the fit or congruence of their current environments, but rather to explain why some older people have more enriched coping repertoires and adapt more successfully than others.

The multiple and linked layers of proposed constructs and relationships that influence the coping behaviors of older people contribute to the complexity of this theoretical model. The generation and testing of hypotheses will be challenging because a large number of interacting individual and environmental determinants—measured by both subjective and objective indicators—predict the coping outcomes of older people. Additionally, the temporal context of their secondary appraisal processes requires the implementation of a more expensive and time-consuming longitudinal research design to predict their coping outcomes. Qualitative rather than quantitative research investigations may at least initially offer the most promising lines of inquiry (Granbom et al., 2014; Löfqvist et al., 2013). An intensive focus on smaller study populations may help delineate and prioritize the most relevant secondary appraisal processes.

The complexity of this theory is tempered, however, by the proposal of constructs and relationships that are mostly derived from other well-tested theories (including assimilative coping processes, resiliency, and secondary appraisal processes) and by related past empirical investigations that offer useful operational and verification guidelines.

Moreover, this theoretical complexity may not necessarily be a bad thing. The real-world decision making of older persons is also complicated. To explain and predict their adaptive behaviors requires a holistic conceptual framework that can organize and interpret our current empirical evidence, guide what new questions to ask, data to collect, and relationships to investigate.

Our programmatic responses must also be sensitive to the idiosyncratic ways that older people decide on how to cope with their inappropriate residential and care environments. It is unrealistic to expect them to adopt and tolerate one-size-fits-all coping solutions given their diverse demographics, personalities, and past life histories. We must appreciate that they occupy places with different opportunities and barriers—both real and perceived—that can allow them once again to feel in their residential comfort and/or mastery zones. We must recognize their need for multiple fixes, how the temporal immediacy of their solutions complicate their coping deliberations, and their aversion to coping strategies with burdensome collateral costs. We must be alert to whether older persons have welcomed the decision-making help of their influencers or have felt victimized by their imposed housing and care decisions. We must also acknowledge that even the most favorable coping strategy appraisals of older persons may be at serious odds with the solutions recommended by professionals or experts. That is, from their objective perspectives, “the appraisal processes of older people may be faulty, and . . . coping strategies that first seem realistic may be flawed” (Granbom et al., 2014, p. 17).

The complexity of the theory thereby communicates to planners, practitioners, policy makers, and philanthropists that they can rely on very different strategies to optimize the coping repertoires of older people and in turn their abilities to age successfully. They can reach out to less resilient older persons by giving them the confidence, knowledge, and adaptive skills to solve their problems. Alternatively, they can selectively change the adaptive capacities or resilience of where they live (or might live) by, for example, increasing their supportive services, recreational and volunteer opportunities, offering assistance to their family caregivers, or by educating their community leaders about the urgent needs of their older constituencies. Having alternative pathways by which to manipulate the coping repertoires of older persons is critical during periods when there are limited resources and when difficult choices must be made about who to target or help and what types of problems to alleviate (Golant, 2014).

References

- Aldwin C., Igarashi H. (2012). An ecological model of resilience in late life. In Hayslip B., Smith G. C. (Eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (pp. 115–130). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ball M. M., Perkins M. M., Hollingsworth C., Whittington F. J., King S. V. (2009). Pathways to assisted living: The influence of race and class. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28, 81–108. 10.1177/0733464808323451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes M. M., Carstensen L. L. (1996). The process of successful ageing. Ageing & Society, 16, 397–422. 10.1017/S0144686X00003603 [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122–147. 10.1037/0003-066x.37.2.122 [Google Scholar]

- Bekhet A. K., Zauszniewski J. A., Nakhla W. E. (2009). Reasons for relocation to retirement communities: A qualitative study. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 31, 462–479. 10.1177/0193945909332009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstadter J., Greve W. (1994). The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review, 14, 42–80. 10.1006/drev.1994.1003 [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen L. L., Isaacowitz D. M., Charles S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously. A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54, 165–181. 10.1037//0003-066x.54.3.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson S., Michie J., Tyler P. (2010). Regional resilience: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3, 3–10. 10.1093/Cjres/Rsq004 [Google Scholar]

- Davoudi S. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Planning Theory & Practice, 12, 299–333. 10.1080/14649357.2012.677124 [Google Scholar]

- Denhardt J., Denhardt R. (2010). Building organizational resilience and adaptive management. In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 333–349). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Depp C. A., Jeste D. V. (2006). Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 6–20. 10.1097/01.Jgp.0000192501.03069.Bc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxiadēs K. A. (1968). Ekistics: An introduction to the science of human settlements. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein R., Garcia A., Netherland J., Walker J. (2008). Toward an age-friendly New York City: A findings report. New York: The New York Academy of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (1998). Changing an older person’s shelter and care setting: A model to explain personal and environmental outcomes. In Windley P. G., Scheidt R. J. (Eds.), Environment and aging theory: A focus on housing (pp. 34–60). New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2003). Conceptualizing time and behavior in environmental gerontology: A pair of old issues deserving new thought. The Gerontologist, 43, 638–648. 10.1093/geront/43.5.638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2008). The future of assisted living residences: A response to uncertainty. In Golant S. M., Hyde J. (Eds.), The assisted living residence: A vision for the future (pp. 3–45). Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2011a). The changing residential environments of older people. In Binstock R. H., George L. K. (Eds.), Handbook of aging and the social sciences (7th ed., pp. 207–220). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2011b). The quest for residential normalcy by older adults: Relocation but one pathway. Journal of Aging Studies, 25, 193–205. 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.003 [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2012). Out of their residential comfort and mastery zones: Toward a more relevant environmental gerontology. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 26, 26–43. 10.1080/02763893.2012.655654 [Google Scholar]

- Golant S. M. (2014). Age-friendly communities: Are we expecting too much? Montreal, Canada: Institute for Research on Public Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Granbom M., Himmelsbach I., Haak M., Löfqvist C., Oswald F., Iwarsson S. (2014). Residential normalcy and environmental experiences of very old people: Changes in residential reasoning over time. Journal of Aging Studies, 29, 9–19. 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantmakers in Aging. (2013). Age-friendly communities. Arlington, VA: Grantmakers in Aging. [Google Scholar]

- Gubrium J. F., Rittman M. R., Williams C., Young M. E., Boylstein C. A. (2003). Benchmarking as everyday functional assessment in stroke recovery. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, S203–S211. 10.1093/geronb/58.4.S203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. S., Zautra A. J. (2010). Indicators of community resilience: What are they, why bother? In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 350–371). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J. (1997). Developmental regulation across adulthood: Primary and secondary control of age-related challenges. Developmental Psychology, 33, 176–187. 10.1037/0012-1649.33.1.176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J., Wrosch C., Schulz R. (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117, 32–60. 10.1037/A0017668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J. (1978). Environment and behavior: A dynamic perspective. New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Iwarsson S., Wahl H. W., Nygren C., Oswald F., Sixsmith A., Sixsmith J, … Tomsone S. (2007). Importance of the home environment for healthy aging: Conceptual and methodological background of the European ENABLE-AGE Project. The Gerontologist, 47, 78–84. 10.1093/geront/47.1.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen B. M., Abma T. A., Van Regenmortel T. (2012). Maintaining mastery despite age related losses. The resilience narratives of two older women in need of long-term community care. Journal of Aging Studies, 26, 343–354. 10.1016/j.jaging.2012.03.003 [Google Scholar]

- Jeste D. V., Savla G. N., Thompson W. K., Vahia I. V., Glorioso D. K., Martin A. S, … Depp C. A. (2013). Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 188–196. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer E. J., Abelson R. P. (1983). The psychology of control. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton M. P., Nahemow L. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In Eisdorfer C., Lawton M. P. (Eds.), The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 619–674). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R. S., Folkman S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M. A. (1991). Relocation of the frail elderly. In Birrren J. E., Lubben J. E., Rowe J. C., Deutchman D. E. (Eds.), The concept and measurement of quality of life in the frail elderly (pp. 120–141). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Löfqvist C., Granbom M., Himmelsbach I., Iwarsson S., Oswald F., Haak M. (2013). Voices on relocation and aging in place in very old age–a complex and ambivalent matter. The Gerontologist, 53, 919–927. 10.1093/geront/gnt034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky M. R., Lysack C. L., Van Nuil J. (2011). Refashioning one’s place in time: Stories of household downsizing in later life. Journal of Aging Studies, 25, 243–252. 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magai C. (2001). Emotions over the life span. In Birren J. E., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook for psychology and aging (5th ed, pp. 399–426). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marottoli R. A., Coughlin J. F. (2011). Walking the tightrope: Developing a systems approach to balance safety and mobility for an aging society. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 23, 372–383. 10.1080/08959420.2011.605655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A. S., Wright M. O. (2010). Resilience over the lifespan. In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 213–237). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. D., Ekerdt D. J. (2011). Age and the cultivation of place. Journal of Aging Studies, 25, 189–192. 10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.010 [Google Scholar]

- Morgan L. A., Brazda M. A. (2013). Transferring control to others: Process and meaning for older adults in assisted living. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 32, 651–668. 10.1177/0733464813494568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren C., Oswald F., Iwarsson S., Fange A., Sixsmith J., Schilling O, … Wahl H. W. (2007). Relationships between objective and perceived housing in very old age. The Gerontologist, 47, 85–95. 10.1093/geront/47.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament K. I., Cummings J. R. (2010). Anchored by faith. In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 193–210). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pendall R., Foster K. A., Cowell M. (2010). Resilience and regions: Building understanding of the metaphor. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3, 71–84. 10.1093/cjres/rsp028 [Google Scholar]

- Perry T. E., Andersen T. C., Kaplan D. B. (2014). Relocation remembered: Perspectives on senior transitions in the living environment. The Gerontologist, 54, 75–81. 10.1093/geront/gnt070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruchno R. A., Wilson-Genderson M., Rose M., Cartwright F. (2010). Successful aging: Early influences and contemporary characteristics. The Gerontologist, 50, 821–833. 10.1093/geront/gnq041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosowsky E. (2011). Resilience and personality disorders in older age. In Resnick B., Gwyther L. P., Roberto K. A. (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research, and outcomes (pp. 31–50). New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe J. W., Kahn R. L. (1998). Successful aging. New York: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Scheidt R. J., Windley P. G. (2006). Environmental gerontology: Progress in the post-Lawton era. In Birren J., Schaie K. W. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (6th ed., pp. 105–125). New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Brenner G. (1977). Relocation of the aged: A review and theoretical analysis. Journal of Gerontology, 32, 323–333. 10.1093/geronj/32.3.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R., Heckhausen J. (1996). A life span model of successful aging. The American Psychologist, 51, 702–714. 10.1037//0003-066X.51.7.702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergeant J. F., Ekerdt D. J., Chapin R. K. (2010). Older adults’ expectations to move: Do they predict actual community-based or nursing facility moves within 2 years? Journal of Aging and Health, 22, 1029–1053. 10.1177/0898264310368296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol A. (2010). The resilient personality. In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 112–125). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steverink N., Lindenberg S., Ormal J. (1998). Towards understanding successful ageing: Patterned change in resources and goals. Ageing & Society, 18, 441–467. [Google Scholar]

- Stoller E. P., Longino C. F., Jr (2001). “Going home” or “leaving home”? The impact of person and place ties on anticipated counterstream migration. The Gerontologist, 41, 96–102. 10.1093/geront/41.1.96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone R. (2011). Long-term care for the elderly. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge W. J., Wallhagen M. I., Cohen R. D. (2002). Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. The Gerontologist, 42, 727–733. 10.1093/geront/42.6.727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge L. M., Jette A. M. (1994). The disablement process. Social Science & Medicine, 38, 1–14. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar F. (2012). Successful ageing and development: The contribution of generativity in older age. Ageing & Society, 32, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar]

- von Faber M., Bootsma-van der Wiel A., van Exel E., Gussekloo J., Lagaay A. M., van Dongen E, … Westendrop R. G. (2001). Successful aging in the oldest old: Who can be characterized as successfully aged? Archives of Internal Medicine, 161, 2694–2700. 10.1001/archinte.161.22.2694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl H. W., Iwarsson S., Oswald F. (2012). Aging well and the environment: Toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. The Gerontologist, 52, 306–316. 10.1093/geront/gnr154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild K., Wiles J. L., Allen R. E. S. (2013). Resilience: Thoughts on the value of the concept for critical gerontology. Ageing & Society, 33, 137–158. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2007). Global age-friendly cities: A guide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra A. J., Hall J. S., Murray K. E. (2010). Resilience: A new definition of health for people and communities. In Reich J. W., Zautra A. J., Hall J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 3–29). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]