Abstract

The prfA-virulence gene cluster (pVGC) is the main pathogenicity island in Listeria monocytogenes, comprising the prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, and plcB genes. In this study, the pVGC of 36 L. monocytogenes isolates with respect to different serotypes (1/2a or 4b), geographical origin (Australia, Greece or Ireland) and isolation source (food-associated or clinical) was characterized. The most conserved genes were prfA and hly, with the lowest nucleotide diversity (π) among all genes (P < 0.05), and the lowest number of alleles, substitutions and non-synonymous substitutions for prfA. Conversely, the most diverse gene was actA, which presented the highest number of alleles (n = 20) and showed the highest nucleotide diversity. Grouping by serotype had a significantly lower π value (P < 0.0001) compared to isolation source or geographical origin, suggesting a distinct and well-defined unit compared to other groupings. Among all tested genes, only hly and mpl were those with lower nucleotide diversity in 1/2a serotype than 4b serotype, reflecting a high within-1/2a serotype divergence compared to 4b serotype. Geographical divergence was noted with respect to the hly gene, where serotype 4b Irish strains were distinct from Greek and Australian strains. Australian strains showed less diversity in plcB and mpl relative to Irish or Greek strains. Notable differences regarding sequence mutations were identified between food-associated and clinical isolates in prfA, actA, and plcB sequences. Overall, these results indicate that virulence genes follow different evolutionary pathways, which are affected by a strain's origin and serotype and may influence virulence and/or epidemiological dominance of certain subgroups.

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, virulence, gene sequencing, diversity, prfA, hly, actA

Introduction

Listeria monocytogenes is a facultative intracellular foodborne pathogen, with pregnant women and neonates, immunocompromised individuals, and the elderly representing high risk groups for infection (Farber and Peterkin, 1991; EFSA ECDC, 2015). It is equally capable of both a saprophytic lifecycle in the environment and human infection causing the severe disease of listeriosis (Gray et al., 2006). Due to its wide variety of reservoirs (Farber and Peterkin, 1991; Lianou and Sofos, 2007), its ability to colonize abiotic surfaces (Møretrø and Langsrud, 2004; Poimenidou et al., 2016b) and to withstand environmental stresses (Hill et al., 2002; Poimenidou et al., 2016a), it is frequently implicated in food processing plant contamination, where it is able to persist for several months or years (Halberg Larsen et al., 2014), thus raising the risk to food safety. After transmission via contaminated food to humans, L. monocytogenes cells may cause illnesses such as gastroenteritis or invasive listeriosis following intestinal translocation. It may then be carried by blood or lymph fluid and reach the mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen and/or the liver, leading to subclinical pyogranulomatous hepatitis, meningoencephalitis, septicemia, placentitis, abortion, or neonatal septicemia (Vázquez-Boland et al., 2001b). Within the host, L. monocytogenes parasitizes macrophages and invades non-phagocytic cells, utilizing its virulence factors to mediate cell-to-cell spread (de las Heras et al., 2011).

The virulence potential of L. monocytogenes relies on several molecular determinants (Camejo et al., 2011), which play key roles at different stages of the infection process. Among the early stages of the infection process, genes including the internalins (inlA, inlB, inlF, inlJ) play key roles in adhesion and invasion. Intracellular pathogenesis heavily relies on factors transcribed by genes located in the major prfA-regulated virulence gene cluster (pVGC), also referred to as Listeria pathogenicity island 1 or LIPI-1 (Vázquez-Boland et al., 2001a; Ward et al., 2004). pVGC genes facilitate the intracellular growth and spread of the bacterium in the host and consist of a monocistron hly, which occupies the central position in the locus, a lecithinase operon comprising mpl, actA, and plcB genes, which is located downstream from hly and transcribed in the same orientation, and the plcA-prfA operon located upstream from hly and transcribed in the reverse direction (Portnoy et al., 1992; Vázquez-Boland et al., 2001b; Roberts and Wiedmann, 2003). The prfA gene encodes the PrfA protein, which is required for the transcription of pVGC, and prfA itself. Listeriolysin O (LLO) encoded by the hly gene is a pore-forming toxin that mediates lysis of bacterium-containing phagocytic vacuole, resulting in the release of bacterial cells into the host cytoplasm. plcA and plcB encode the phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) and zinc-dependent broad-spectrum phospholipase C (PC-PLC), respectively, which synergistically with LLO mediate the escape of the pathogen from the single- and double-membrane-bound vacuoles. After lysis, the intracellular motility and cell-to-cell spread are mediated by the surface protein actin A (ActA) through actin polymerization, for which additional functions (i.e., role in invasion, aggregation, colonization and persistence in the gut lumen) have been reported (Suárez et al., 2001; Travier et al., 2013). mpl encodes a zinc metalloproteinase needed to activate PC-PLC in order to initiate a new infection cycle.

Listeria monocytogenes is a genetically diverse species; its isolates form a structured population and are differentiated into four distinct lineages and 13 serotypes (Orsi et al., 2011), with the majority of isolates clustering into lineage I (serotypes 1/2b, 3b, 3c, 4b) and lineage II (serotypes 1/2a, 1/2c, 3a). Serotypes 4b and 1/2a are overrepresented among isolates associated with human listeriosis cases and food environment isolates, respectively (McLauchlin, 1990, 2004; Schuchat et al., 1991; Norton et al., 2001; Jacquet et al., 2002; Mereghetti et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2004; Lukinmaa et al., 2004; Gilbreth et al., 2005; Kiss et al., 2006; Swaminathan and Gerner-Smidt, 2007; Ebner et al., 2015). Additionally, various L. monocytogenes strains have presented diversity in virulence potential (Brosch et al., 1993; Chakraborty et al., 1994; Jaradat and Bhunia, 2003; Roche et al., 2003; Neves et al., 2008). Defective forms of virulence determinants were identified as the source of such virulence attenuation (Olier et al., 2002, 2003; Roberts et al., 2005; Roche et al., 2005; Témoin et al., 2008; Van Stelten et al., 2011).

The reasons that 1/2a serotype strains predominate among food environment isolates and 4b serotype strains among human listeriosis isolates are under investigation, with no clear inference made so far (Jaradat et al., 2002; Larsen et al., 2002; Gray et al., 2004; Jensen et al., 2007, 2008; Neves et al., 2008; Houhoula et al., 2012). On the other hand, there are indications of selective pressure for maintenance or specific adaptation of the pVGC genes in particular environments (Roberts et al., 2005; Orsi et al., 2008; Travier et al., 2013). Comparative genotyping could contribute to identifying unique genetic determinants toward the intraspecific pathogenic characteristics of L. monocytogenes isolates. Considering the above, the objective of this study was to examine the nucleotide diversity of the pVGC genes of L. monocytogenes strains isolated from human clinical cases and food or food-related environments, which belonged to the serotypes 4b and 1/2a and originated from three distinct geographical locations (i.e., Australia, Greece, and Ireland). Studying these variations may provide valuable information toward understanding the significance of virulence gene variation and the influence of environmental pressures acting on the genes.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains

A total of 36 Listeria monocytogenes strains (Table 1) were analyzed in this study. The strains represented three distinct geographically dispersed regions (Australia, Greece, Ireland), two serotypes (serotype 4b and 1/2a) and two isolation sources (clinical and food–related isolates). The clinical strains were kindly provided by Dr. Josheph Papaparaskevas (Houhoula et al., 2012) and Prof. Martin Cormican (University College Hospital, Galway, Ireland). The food-associated isolates were obtained from food and the food-processing environment. The strains were serotyped using a combination of antisera specific to the L. monocytogenes somatic O-antigen (Denka Seiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), in tandem with a PCR-based serovar determination assay (Doumith et al., 2004), as described by Fox et al. (2009). Bacterial strains were stored at −80°C in Tryptic Soy broth (TSB) containing 20% glycerol and were cultured in TSB supplemented with 0.6% yeast extract (YE) at 37°C overnight, prior to pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and DNA extraction.

Table 1.

Origins and characteristics of 36 L. monocytogenes strains used in the study.

| Country | Isolate | Origin | Date | Serotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ireland | IR_227 | Dairy processing environment | 2008 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_728 | Dairy processing environment | 2012 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_872 | Dairy processing environment | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_873 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_874 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_875 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Ireland | IR_250 | Dairy processing environment | 2008 | 4b |

| Ireland | IR_338 | Dairy processing environment | 2008 | 4b |

| Ireland | IR_355 | Dairy processing environment | 2008 | 4b |

| Ireland | IR_876 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 4b |

| Ireland | IR_877 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 4b |

| Ireland | IR_878 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_PL11 | Chicken | 2007 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL18 | Chicken | 2007 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL37 | Clinical isolate | 2009 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL38 | Clinical isolate | 2009 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL44 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL50 | Food isolate | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Greece | GR_PL4 | Dairy farm environment | 2007 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_PL13 | Chicken | 2007 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_PL32 | Clinical isolate | 2009 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_PL41 | Clinical isolate | 2009 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_PL46 | Clinical isolate | 2013 | 4b |

| Greece | GR_FL78 | Meat | 2012 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2884 | Seafood | 2009 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_2919 | Meat processing environment | 2013 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_2942 | Dairy food | 2009 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_2994 | Vegetable | 2011 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_2998 | Meat | 2011 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_Lm14-002 | Dairy food | 2014 | 1/2a |

| Australia | AU_2473 | Dairy food | 1998 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2544 | Clinical isolate | 1994 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2727 | Meat | 1988 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2948 | Dairy food | 2010 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2993 | Dairy processing environment | 2009 | 4b |

| Australia | AU_2995 | Dairy processing environment | 2009 | 4b |

PFGE of L. monocytogenes isolates

PFGE was carried out using the International Standard PulseNet protocol (Pulsenet USA, 2009). Two restriction enzymes, AscI and ApaI, were used and band patterns were analyzed using Bionumerics version 5.10 software (Applied Maths, Belgium), as previously described (Fox et al., 2012). Briefly, band matching was performed using the DICE coefficient, with both optimization and tolerance settings of 1%. Dendrograms were created using the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA). Strains were considered to be indistinguishable when their pulsotypes displayed 100% similarity on the dendrogram and after confirmation by visual examination of the bands. To help support population diversity, all isolates were confirmed as having a unique pulsotype relative to any other isolate included in this study.

DNA extraction

Following overnight culture of each strain, DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, UK) for strains from both Greece and Australia, or the QIAmp DNA mini kits (Qiagen) for strains from Ireland. A cell lysis step preceded DNA extraction and consisted in incubation of the cells in lysis buffer (20 mM TrisHCl, pH 8; 2 mM EDTA, pH 8; 1.2% Triton® −100; 20 mg/ml lysozyme) for 1 h at 37°C. DNA was stored at −20°C before use.

Nucleotide sequencing of actA, hly, mpl, plcA, plcB, prfA

PCR amplification of the targeted genes was performed using genomic DNA extracted as described above. Primer design was based on available sequences of the targeted genes in public databases using Primer3Plus software version 2.3.5 (Untergasser et al., 2012). The primers and PCR conditions, all including 35 cycles, are described in Table 2. Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs® Inc, USA) and AccuTaqTM LA DNA polymerase (Sigma, USA) were used for PCR reactions on 50 ng DNA for strains from Greece and Ireland, respectively. Following amplification, PCR products were purified using MinElute Gel Extraction kit (Qiagen). DNA sequencing was performed using external forward and reverse PCR primers at CEMIA SA (Larisa, Greece) and Source Biosciences (Dublin, Ireland) for Greece and Ireland PCR products, respectively. In the case of Australian isolates, sequences were extracted in silico from draft genomes using the same primer sets (Table 2) with Geneious® software version 9 (Kearse et al., 2012). DNA sequencing chromatograms were saved as ABI files for analysis.

Table 2.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions for each virulence gene target.

| Gene | Strains ID | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Hybridization temperature (°C) | Elongation time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| actA | All strains | Forwarda, GTATTAGCGTATCACGAGGA | 60 | 1 |

| Reversea, CAAGCACATACCTAGAACCA | ||||

| Forwardb, AAGMGTCAGTTRYGGATRCT | 57 | 1 | ||

| Reverseb, CCCGCATTTCTTGAGTGTTT | ||||

| hly | 227, 728, 872, 873, 874, 875, 876 | Forwarda, GGCCCCCTCCTTTGATTAGT | 60 | 2 |

| Reversea, GCCTCTTTCTACATTCTTCACAAA | ||||

| 355 | Forwarda, TATGCTTTTCCGCCTAATGG | 57 | 1 | |

| Reversea, CGTGTGTGTTAAGCGGTTT | ||||

| 250, 338, 877, 878 | Forwarda, AAAAGAGAGGGGTGGCAAAC | 60 | 2 | |

| Reversea, GCCTCTTTCTACATTCTTCACAAA | ||||

| All strains | Forwardb, CCAGGTGCTCTCGTRAAAGC | 57 | 1 | |

| Reverseb, RCCGTCGATGATTTGAACTT | ||||

| mpl | All strains | Forwarda, GCCACCTATAGTTTCTACTGCAAA | 57 | 1 |

| Reversea, TGRAGAATTAAKTTTTCTCTAACATTT | ||||

| All strains | Forwardb, ATACGCTCGCGCTAAGTTCT | 60 | 1 | |

| Reverseb, GCTTCTTATTCGCCCATCTCG | ||||

| plcA | All strains | Forwarda, ATCAAAGGAGGGGGCCATT | 60 | 1 |

| Reversea, CCGAGGTTGCTCGGAGATATAC | ||||

| plcB | All strains | Forwarda, ATTGGCGTGTTCTCTTTAGGc | 57 | 1 |

| Reversea, CAAAGAAAAAGATTAACCTCCCTTT | ||||

| prfA | All strains | Forwarda, TTCAGGTCCKGCTATGAAAC | 57 | 1 |

| Reversea, AACTCCATCGCTCTTCCAGA |

External primers located in upstream and downstream regions surrounding the targeted gene.

Internal primers.

Roche et al., 2005.

Data analysis

Sequence assembly was performed using SeqMan Pro application in Lasergene® Genomics suite (DNASTAR, USA). Geneious® software version 9 (Kearse et al., 2012) was used to construct translation alignments for each gene separately and the pVGC (a concatenated sequence comprising the prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, plcB sequences).

Descriptive analysis

Number of polymorphic sites (S), nucleotide diversity (π; average pairwise nucleotide differences per site), number of segregating sites (θ), and Tajima's D for neutrality were calculated using DnaSP software version 5 (Librado and Rozas, 2009). Number of polymorphic sites, number of substitutions, number of synonymous substitutions (SS) and non-synonymous substitutions (NSS), and the G + C content (%) were defined using Geneious software version 9 (Kearse et al., 2012). The dN/dS ratios or ω [number of non-synonymous substitutions/nonsynonymous sites (dN) to the number of synonymous substitutions/synonymous sites (dS)] were calculated using the Datamonkey online platform (Kosakovsky Pond and Frost, 2005). 3D scatterplots were created using 'Excel 3D Scatter Plot' version 2.1 (available at: http://www.doka.ch/Excel3Dscatterplot.htm).

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic trees were generated using the NeighborNet algorithm (Bryant and Moulton, 2004) as adopted in SplitsTree software (Huson, 1998).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis data calculated for individual genes were used in order to compare π, θ, and ω parameters for the pVGC with regard to different serotypes, geographical origin or isolation source using Student's t test (JMP version 9.0); significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

Among the 36 strain sequences analyzed, representing distinct PFGE profiles (Supplementary Material), 26 unique alleles were identified for pVGC (Table 3, Supplementary Dataset S1). Twenty-three isolates harbored a full length cluster of 7,503 nucleotides; 12 isolates had a 105 bp deletion in their actA sequence and as such had a 7,398 bp pVGC; one isolate had a single nucleotide deletion in its actA gene sequence and thus a 7,502 bp pVGC.

Table 3.

Sequence diversity analysis of virulence genes sequences.

| Gene (length in nt) | Strains | Polymorphic sites | Substitutions | Alleles | G + C content (%) | SynSubsa | Non-SynSubsb | π/sitec | θ/sited | Tajima's D valuee | dN/dS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pVGC (7503) | 36 | 439 | 463 | 26 | 37.2 | 281 | 182 | 0.02427 | 0.01601 | 2.05558** | 0.188618 |

| Serotype 1/2a | 18 | 243 | 258 | 14 | 37.2 | 124 | 134 | 0.00913 | 0.01059 | −0.62147 | 0.230547 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 75 | 75 | 12 | 37.2 | 24 | 51 | 0.00411 | 0.00345 | 0.89916 | 0.169137 |

| Food associated | 23 | 433 | 456 | 19 | 37.2 | 276 | 180 | 0.025 | 0.01736 | 1.85522* | 0.181073 |

| Clinical | 13 | 351 | 359 | 11 | 37.2 | 223 | 136 | 0.02393 | 0.0174 | 1.81904* | 0.168402 |

| Australian | 12 | 405 | 424 | 10 | 37.2 | 258 | 166 | 0.02593 | 0.01978 | 1.55772 | 0.183604 |

| Greek | 12 | 373 | 374 | 8 | 37.2 | 237 | 137 | 0.02513 | 0.01971 | 1.5115 | 0.175085 |

| Irish | 12 | 384 | 395 | 11 | 37.2 | 245 | 150 | 0.0243 | 0.01823 | 1.61429 | 0.173244 |

| prfA (711) | 36 | 24 | 24 | 8 | 33.4 | 20 | 4 | 0.01551 | 0.01296 | 1.03014 | 0.0842314 |

| Serotype 1/2a | 18 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 33.4 | 3 | 3 | 0.00336 | 0.00403 | −1.14554 | 0.26142 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 33.2 | 1 | 1 | 0.00187 | 0.00187 | NAf | 0.259992 |

| Food associated | 23 | 24 | 24 | 8 | 33.2 | 20 | 4 | 0.01551 | 0.01296 | 1.03014 | 0.0842313 |

| Clinical | 13 | 19 | 19 | 4 | 33.3 | 19 | 0 | 0.01727 | 0.01451 | 1.94585 | 5.00E−09 |

| Australian | 12 | 21 | 22 | 5 | 33.4 | 19 | 3 | 0.01653 | 0.01412 | 1.26346 | 0.0464163 |

| Greek | 12 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 33.3 | 19 | 1 | 0.01625 | 0.01345 | 1.54012 | 0.0312951 |

| Irish | 12 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 33.4 | 19 | 1 | 0.01597 | 0.01345 | 1.38611 | 0.0314107 |

| plcA (951) | 36 | 57 | 58 | 13 | 35.8 | 41 | 17 | 0.02215 | 0.01925 | 0.67574 | 0.166368 |

| Serotype 1/2a | 18 | 38 | 39 | 10 | 35.7 | 26 | 13 | 0.01624 | 0.01408 | 0.74193 | 0.193846 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 36.1 | 5 | 1 | 0.00419 | 0.00419 | NA | 0.0560234 |

| Food associated | 23 | 56 | 57 | 11 | 35.8 | 41 | 16 | 0.02314 | 0.02004 | 0.73176 | 0.152218 |

| Clinical | 13 | 50 | 50 | 7 | 35.8 | 36 | 14 | 0.02296 | 0.02139 | 0.42397 | 0.16682 |

| Australian | 12 | 51 | 52 | 8 | 35.8 | 38 | 14 | 0.02242 | 0.02062 | 0.47162 | 0.141993 |

| Greek | 12 | 43 | 43 | 5 | 35.7 | 32 | 11 | 0.02432 | 0.02164 | 0.93385 | 0.123106 |

| Irish | 12 | 54 | 55 | 8 | 35.9 | 39 | 16 | 0.02538 | 0.02183 | 0.87667 | 0.153798 |

| hly (1587) | 36 | 57 | 59 | 19 | 36 | 53 | 6 | 0.01409 | 0.01044 | 1.43362 | 0.0660299 |

| Serotype1/2a | 18 | 22 | 23 | 11 | 36 | 19 | 4 | 0.00453 | 0.00472 | −0.18884 | 0.106618 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 31 | 31 | 8 | 36 | 26 | 5 | 0.00984 | 0.00752 | 1.63658 | 0.0630305 |

| Food associated | 23 | 55 | 57 | 16 | 36 | 51 | 6 | 0.01388 | 0.01061 | 1.30974 | 0.0681005 |

| Clinical | 13 | 51 | 52 | 9 | 36 | 48 | 4 | 0.01544 | 0.0118 | 1.57407 | 0.0634322 |

| Australian | 12 | 53 | 54 | 8 | 36 | 49 | 5 | 0.01388 | 0.0131 | 0.32216 | 0.0474897 |

| Greek | 12 | 51 | 51 | 6 | 36 | 46 | 5 | 0.01694 | 0.01405 | 1.3193 | 0.0498417 |

| Irish | 12 | 48 | 48 | 9 | 36 | 44 | 4 | 0.01328 | 0.01111 | 0.99492 | 0.0458643 |

| mpl (1497) | 36 | 86 | 87 | 14 | 38.1 | 58 | 29 | 0.02413 | 0.01873 | 1.16267 | 0.133937 |

| Serotype1/2a | 18 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 38.2 | 9 | 3 | 0.0026 | 0.00283 | −0.37581 | 0.0731896 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 37.9 | 6 | 3 | 0.00345 | 0.00328 | 0.52223 | 0.118136 |

| Food associated | 23 | 86 | 87 | 11 | 38.1 | 58 | 29 | 0.02633 | 0.01984 | 1.56388 | 0.136483 |

| Clinical | 13 | 79 | 79 | 7 | 38.1 | 52 | 27 | 0.02418 | 0.02154 | 0.71271 | 0.144224 |

| Australian | 12 | 81 | 82 | 8 | 37.1 | 54 | 28 | 0.02221 | 0.02113 | 0.27887 | 0.141179 |

| Greek | 12 | 82 | 82 | 6 | 38.1 | 54 | 28 | 0.03059 | 0.02399 | 1.77607 | 0.148356 |

| Irish | 12 | 78 | 78 | 8 | 38.1 | 52 | 26 | 0.02667 | 0.0201 | 1.77542* | 0.136472 |

| actA (1890) | 36 | 174 | 190 | 20 | 40.1 | 82 | 108 | 0.03782 | 0.029 | 1.26319 | 0.288458 |

| Serotype1/2a | 18 | 86 | 93 | 13 | 38.8 | 44 | 49 | 0.01819 | 0.01594 | 0.64095 | 0.276396 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 24 | 25 | 7 | 40.2 | 13 | 12 | 0.0055 | 0.00572 | −0.21918 | 0.248332 |

| Food associated | 23 | 169 | 184 | 16 | 40.1 | 81 | 103 | 0.03939 | 0.03005 | 1.35214 | 0.280161 |

| Clinical | 13 | 140 | 152 | 8 | 40.1 | 61 | 91 | 0.03874 | 0.03549 | 0.50002 | 0.320893 |

| Australian | 12 | 154 | 167 | 10 | 40.2 | 72 | 95 | 0.04118 | 0.03228 | 1.37403 | 0.305107 |

| Greek | 12 | 135 | 142 | 7 | 40.1 | 61 | 81 | 0.03727 | 0.03156 | 1.06034 | 0.284034 |

| Irish | 12 | 161 | 175 | 8 | 40.1 | 78 | 97 | 0.04197 | 0.03614 | 0.88101 | 0.288721 |

| plcB (870) | 36 | 45 | 46 | 12 | 36 | 26 | 20 | 0.02254 | 0.01751 | 1.31427 | 0.189206 |

| Serotype1/2a | 18 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 35.8 | 4 | 4 | 0.00271 | 0.00355 | −1.14142 | 0.246995 |

| Serotype 4b | 18 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 36.3 | 2 | 2 | 0.0023 | 0.00251 | −0.78012 | 0.251206 |

| Food associated | 23 | 45 | 46 | 11 | 35.9 | 26 | 20 | 0.02082 | 0.01805 | 0.72105 | 0.188388 |

| Clinical | 13 | 41 | 42 | 6 | 36 | 25 | 17 | 0.02713 | 0.02114 | 1.80741* | 0.16398 |

| Australian | 12 | 42 | 43 | 8 | 35.9 | 24 | 19 | 0.02011 | 0.01906 | 0.29607 | 0.189685 |

| Greek | 12 | 43 | 44 | 6 | 36.1 | 26 | 18 | 0.02797 | 0.02215 | 1.67957 | 0.168418 |

| Irish | 12 | 40 | 41 | 6 | 36.1 | 24 | 17 | 0.02674 | 0.02064 | 1.88777 | 0.169274 |

Number of synonymous substitutions.

Number of non-synonymous substitutions.

Average pairwise nucleotide difference per site.

Index of the number of segregating sites (mutation rate).

Tajima's D-values significantly different from 0 are indicated with

(0.05 < P < 0.1) or with

(P < 0.05).

The value is not available, as it could be not evaluated due to the low number of alleles (4 or more sequences needed).

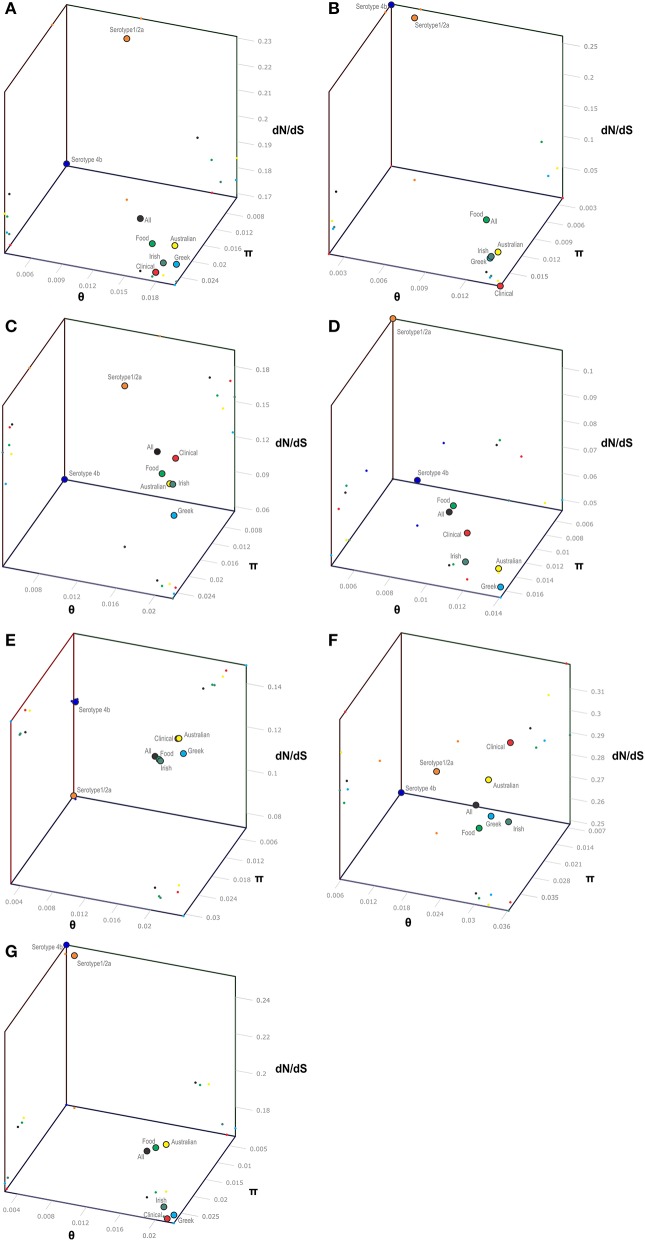

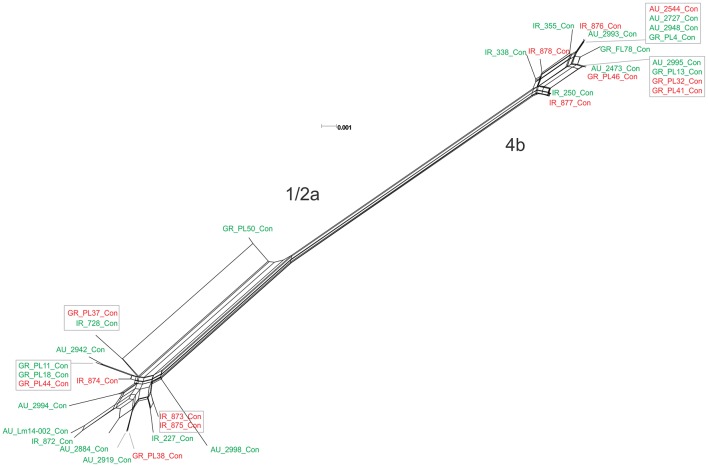

The pVGC contained 439 polymorphic sites, with 281 synonymous and 182 non-synonymous substitutions. The G + C% content was 37.2%. The overall nucleotide diversity was π = 0.02427 and θ = 0.01601. Although π and θ values for serotype 1/2a strains were higher than for 4b strains, the difference was not significant (P > 0.05). No significant π difference was observed among strains of different geographical origin, or between food environment and clinical origin. Comparing groupings by serotype, geographical origin or isolation source, grouping by serotype had a significantly lower π value (P < 0.0001). Serotype groups also exhibited distinct clustering on the 3D-scatter plot (Figure 1A), showing divergence from the other groupings. Divergence between the two serotypes in dN/dS ratio was also observed, suggesting different selective pressure acting on the two serotypes, with higher values among the serotype 1/2a group. The pVGC phylogenetic tree (Figure 2) showed two major distinct clusters representing the two serotypes, 1/2a and 4b. No specific pattern of origin-based classification was observed, with strains isolated in different countries or from different sources (i.e., food-associated or clinical) sharing an identical nucleotide sequence. In each serotype group, stains were clustered in short distances to each other, with only strain GR_PL50 distant to the others.

Figure 1.

3-D scatter-plot illustration of nucleotide diversity parameters (π, θ) and dN/dS ratio (ω) for the pVGC (A), prfA (B), plcA (C), hly (D), mpl (E), actA (F), and plcB (G) genes. Within each gene, colored dots represent the L. monocytogenes population grouping based on serotype (4b and 1/2a), geographical origin (Australian, Greek, and Irish strains), source of isolation (clinical or food environment), and as a whole (All strains).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene cluster prfA (pVGC; concatenated genes prfA, plcA, hly, mpl, actA, and plcB) using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

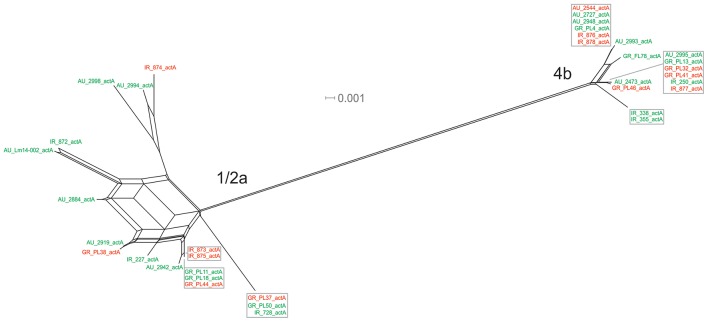

Eight haplotypes among the 36 strains were recovered for the prfA gene (5 for 1/2a serotype and 3 for 4b serotype). This gene possessed the lowest number of polymorphic sites (n = 24) with the lowest number of substitutions (n = 24) and non-synonymous substitutions (n = 4) compared to all fragments tested (Table 3). The overall nucleotide diversity was π = 0.01551 and θ = 0.01296. Groups containing strains of different geographical origin were clustered closely to each other (Figure 1B), while food isolates were distinct from the clinical isolates with respect to π values. Divergence in dN/dS, π and θ parameters resulted in distinct clustering of serotype groups compared to other groupings. The phylogenetic tree of prfA gene (Figure 3) showed the lowest degree of divergence among all tested genes, with longer branch lengths observed for 1/2a serotype isolates than for 4b isolates, which is in accordance with the higher nucleotide diversity within 1/2a serotype than 4b serotype (Table 3). Among the 19 substitutions observed for clinical isolates, none of them were non-synonymous.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene prfA using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

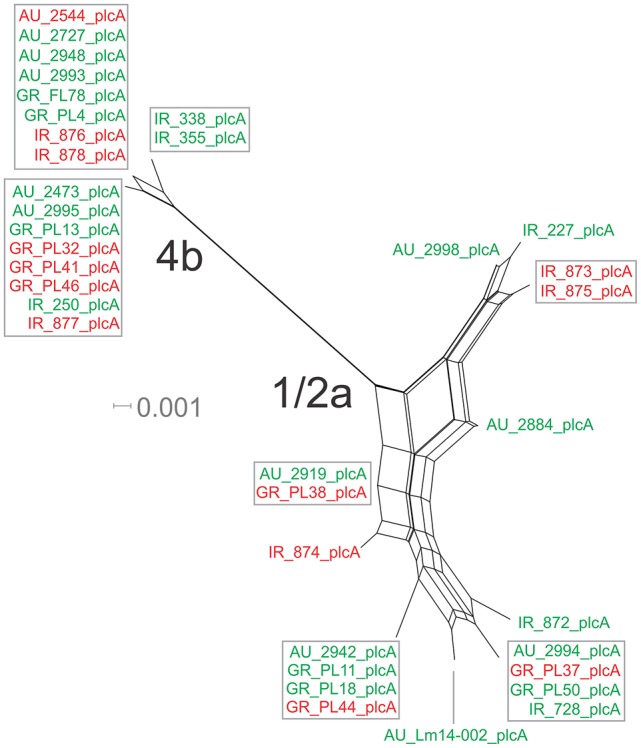

The nucleotide sequence of the plcA gene (13 haplotypes; π = 0.02215) was diversified into 10 unique alleles of 1/2a serotype strains (π = 0.01624) and 3 alleles of 4b serotype strains (π = 0.0419). Serotype 4b strains had the lowest number of substitutions (n = 6) compared to the other subgroups (n = 39–57), which resulted in the lowest nucleotide diversity. Serotype 1/2a strains differed from the other groups in dN/dS ratio values and serotype 4b strains in θ values, resulting in distinct clustering on the 3D-scatter plot (Figure 1C). The phylogenetic tree of the plcA gene (Figure 4) showed that isolates of the 1/2a serotype were highly divergent with more distant branches compared to 4b serotype strains. Unique sequence types in the group of 1/2a serotype belonged to Australian or Irish origin strains.

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene plcA using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

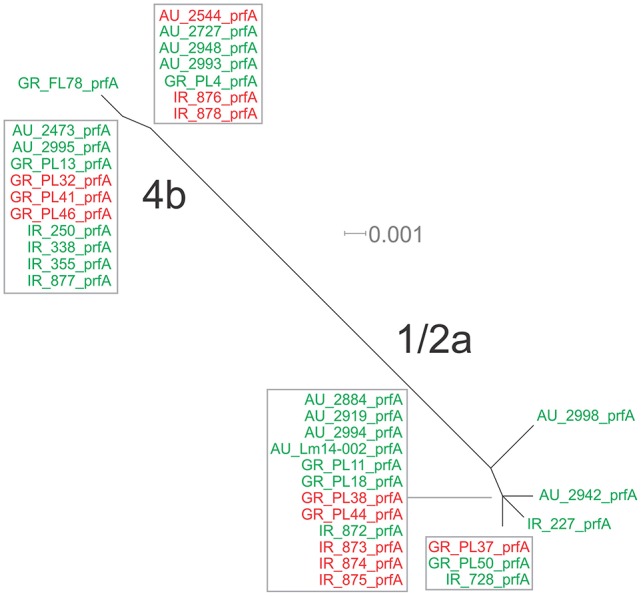

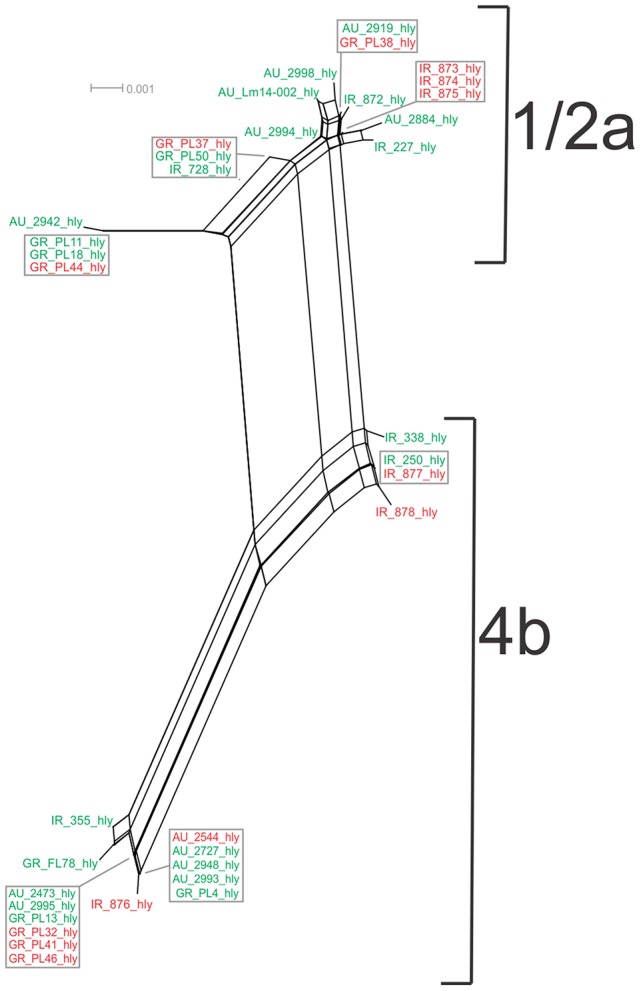

Analysis of the hly gene showed 19 haplotypes among the 36 strains with overall nucleotide diversity π = 0.01409 and θ = 0.01044. Higher diversity was observed among 1/2a serotype than 4b serotype strains (11 and 8 unique alleles, respectively). Groups of different geographical origin or groups of different isolation source (i.e., food environment or clinical) were clustered closely to each other (Figure 1D), in contrast to different serotypes, where the two groups (i.e., 1/2a and 4b serotypes) clustered apart along the dN/dS ratio axis showing a diverse selective pressure acting on the gene within each serotype. As illustrated in Figure 5, a high divergence in hly gene sequences among strains of 4b serotype was observed; two subpopulations were identified, one of which only included Irish isolates. The second subpopulation contained two sets of strains with shared sequences between Australian and Greek strains, and three unique alleles (i.e., one Greek strain and two Irish).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene hly using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

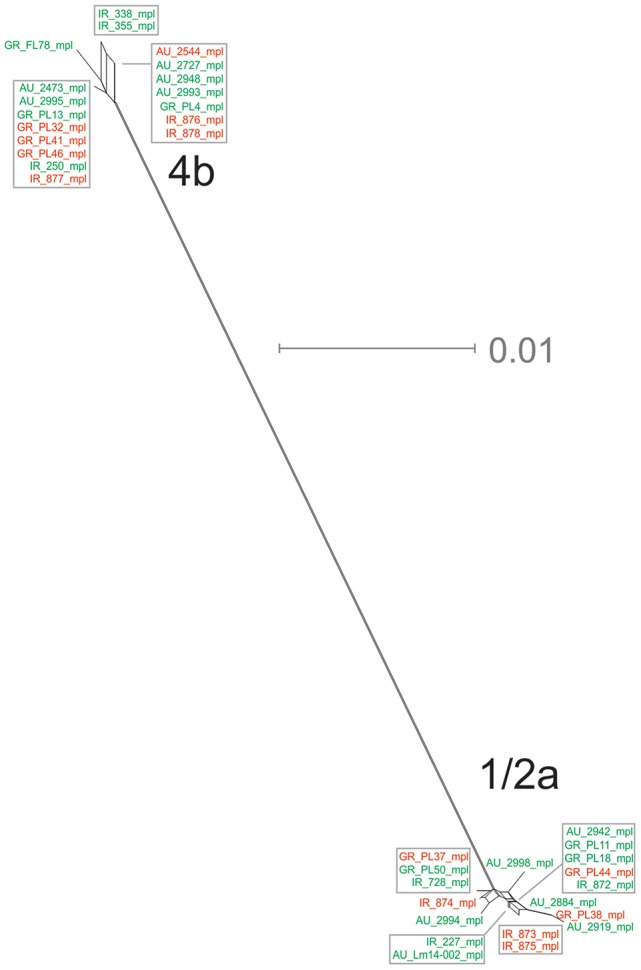

The mpl gene was represented by 14 unique alleles, 10 for 1/2a serotype and 4 for 4b serotype, with π = 0.02413 and θ = 0.01873. Grouping according to serotypes resulted in distinct clusters compared to the other groupings (Figure 1E), due to lower π values, while additionally the two serotype groups (i.e., 1/2a and 4b) differed in their dN/dS ratio demonstrating diverse selective pressure acting on the strains of each serotype within this gene. The phylogenetic tree for the mpl gene (Figure 6) showed a similar clustering of the strains between the two serotypes with respect to branch lengths, and higher divergence within the 1/2a serotype compared to 4b serotype, in terms of unique alleles.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene mpl using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

The actA gene was represented by 20 unique alleles, the highest number among any of the pVGC genes, with overall nucleotide diversity π = 0.03782 and θ = 0.029. Groups containing strains of various origins or serotypes were highly variant, as illustrated in Figure 1F, confirming the diversity of this particular gene. Strains of serotype 1/2a were more diverse (π = 0.01819, θ = 0.01594) than serotype 4b strains (π = 0.0055, θ = 0.00572). This was also evident from the phylogenetic tree (Figure 7), where 13 different nucleotide sequences were found among 18 isolates of 1/2a serotype, with longer branch lengths compared 4b serotype strains. Food isolates had the highest number of non-synonymous substitutions (n = 103) among all subgroups within this gene and clinical isolates the lowest (n = 12). A large variation between the dN/dS ratio values was observed for food and clinical isolates, suggesting a different selective pressure acting on these two groups. Divergence in dN/dS was also observed between Australian and Greek or Irish isolates. Twelve isolates, representing 5 unique alleles, had a 105-bp deletion in their sequences; 8 of these isolates were of food environment origin and 4 of clinical origin. The isolate (AU_Lm14-002) that had a single nucleotide deletion was of food origin.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene actA using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

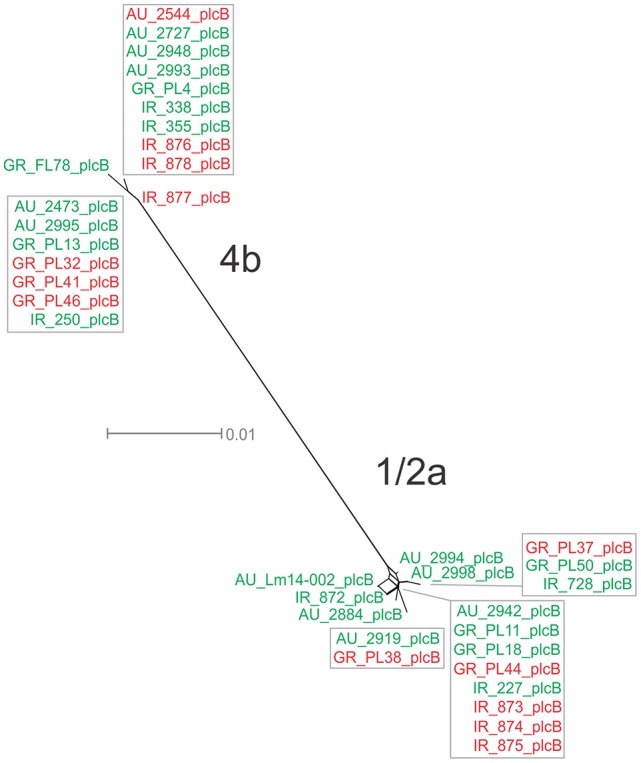

For the plcB gene, 12 haplotypes were observed among the 36 strains, with nucleotide diversity π = 0.02254 and θ = 0.01751. Serotype 1/2a strains were more diverse than 4b strains, represented by higher numbers of unique alleles (8 and 4, respectively), and higher π and θ values. Food-related strains differed from clinical strains, and Australian strains clustered apart from Greek and Irish strains (Figure 1G), showing lower nucleotide diversity and thus, a higher genetic uniformity within the former groups (i.e., food or Australian) compared to the latter (i.e., clinical, Greek, or Irish). In the phylogenetic tree (Figure 8), the short length of the branches indicated the small divergence level among strains within each serotype.

Figure 8.

Phylogenetic network applied to virulence gene plcB using the Neighbor-Net algorithm. L. monocytogenes strains represented food environment isolates (green color) or clinical isolates (red color), isolated in Ireland (IR), Greece (GR), and Australia (AU). Strains clustered together in a box represent identical nucleotide sequence.

Comparing all genes, the most diverse gene was actA (π = 0.03782) and the most conserved hly (π = 0.01409) and prfA (π = 0.01551); the π value of actA was significantly higher compared to hly (P = 0.0095) or prfA (P = 0.0088). Additionally, for pVGC no significant difference in nucleotide diversity was observed between the two serotype groupings, the two isolation sources or the three geographical origin groups. Higher nucleotide diversity in serotype 4b vs. serotype 1/2a was only observed for mpl and hly genes. Regarding the selective pressure acting on the genes, the highest values of the dN/dS ratio were observed for actA and the lowest on prfA and hly genes (P < 0.05).

Tajima's D-test for neutrality (Tajima, 1989; Simonsen et al., 1995), which examines whether the occurring mutations are a result of selection or random (neutral) evolution, showed a significantly positive value for the test for the pVGC (Table 3). This suggests that the gene evolution deviates significantly from the standard neutral model and is under balancing selection, decrease in population size or a subdivision of the population structure. High Tajima's D-values (0.1 > P > 0.05) were also observed for food and clinical isolates in the pVGC, for Irish isolates in the mpl gene and for clinical isolates in the plcB gene. Negative values were observed for serotype 1/2a strains in the pVGC, prfA, and plcB genes, and for 4b serotype in plcB; however, these were not statistically significant and therefore are unlikely to represent a population bottleneck, a selective sweep or purifying selection.

Discussion

In the present study, the intraspecies variations in the prfA virulence gene cluster among 36 L. monocytogenes strains, with respect to different serotype (i.e., 1/2a and 4b), geographical origin (Australian, Greek, and Irish isolates), or isolation source (i.e., food environment or clinical isolates) was investigated. Consistent with previous classification studies (Ward et al., 2004; Orsi et al., 2008), within all six virulence genes analyzed and the pVGC, strains were divided into two major clusters, each representing one serotype, i.e., 4b and 1/2a serotype, which belong to lineage I and II, respectively. L. monocytogenes is a highly diverse species and lineages I and II are considered to be deeply separated evolutionary lineages (Nightingale et al., 2005). Significant association between lineage and the origin of the strains has been reported (Wiedmann et al., 1997), while additionally, molecular types of the strains were shown to be associated with specific food types (Gray et al., 2004). Strains of different lineages are also divergent in terms of their virulence potential. While higher virulence associated with the lineage I population relative to that of lineage II has been reported, (Wiedmann et al., 1997; Norton et al., 2001; Gray et al., 2004; Jensen et al., 2007), others found no statistical correlation between virulence of the strains and their serotypes (Conter et al., 2009). Therefore, molecular typing and a better understanding of virulence stratification among serotypes and lineages are essential in epidemiological surveys and risk estimation procedures. The analysis in this study also showed that 4b serotype strains exhibited lower diversity than the 1/2a strains. This is consistent with previous findings where lineage II strains were genetically more diverse compared to lineage I, based on molecular typing of seven genetic loci including four housekeeping genes, two virulence genes and stress response sigB gene (den Bakker et al., 2008), ribotyping and random multiprimer PCR analysis (Mereghetti et al., 2002), or analysis of the prfA virulence gene cluster (Orsi et al., 2008). In addition to these reports, it was shown here that ω values were similar between the serotype groups for prfA and plcB, while varied largely for the pVGC, plcA, hly, mpl, and actA, indicating a different selective pressure acting on these genes within each serotype. Furthermore, the opposite (i.e., negative vs. positive) Tajima's D values for the serotype groups within pVGC, hly, mpl, and actA suggest that these genes follow a different evolutionary pathway across serotypes.

Results of this study showed that among the six genes examined, only the hly gene of 4b serotype strains was partially correlated with geographical origin, with strains separating into two distinct subpopulations: one containing only Irish strains, the other containing Greek and Australian strains and two Irish strains. Since serotype 4b strains have been found as the etiological agent of the majority of epidemic or sporadic human listeriosis cases in many countries, including Ireland (Schuchat et al., 1991; Swaminathan and Gerner-Smidt, 2007; Fox et al., 2012), and hly is a key gene for the virulence potential of L. monocytogenes (Gaillard et al., 1986; Roberts et al., 2005), the correlation between Irish strains and hly could imply a possible impact of geographical-specific diversification. Previous studies have shown no polymorphism in LLO protein among 150 strains of food and human origin, while slight changes in the hly gene did not imply alterations on LLO molecular weight (Jacquet et al., 2002). Furthermore, no significant differences in the LLO protein among different serotypes 4b and 1/2a were reported (Matar et al., 1992; Jacquet et al., 2002). Nonetheless, Gray et al. (2004) reported a significant correlation between hly allelic types and origin of the strains (i.e., food vs. human isolates); hly type 1 was significantly more common among human isolates and was associated with larger plaque forming, indicative of in vitro cytopathogenicity, compared with other hly types (Gray et al., 2004). Therefore, such correlation of origin and hly types might be important in epidemiological studies. Additionally, studies based on ribotype analysis showed no specific clustering among L. monocytogenes strains distributed across different geographical locations, and therefore no significant effect of geographical distribution on their genetic diversity (Gendel and Ulaszek, 2000; Jaradat et al., 2002; Mereghetti et al., 2002). The sequence diversity analysis in the current study showed that the groups of Greek, Australian and Irish isolates within the pVGC form distinct clusters based on parameters π, θ, and ω, which may underlie diverse evolutionary pathways for each group; this was also observed for all individual genes except the prfA gene. Origin-based pattern in nucleotide diversity was observed for Australian strains, which showed less diversity in plcB and mpl sequences relative to their Irish or Greek counterparts. The Tajima's D-values for Australian isolates were close to 0 contrary to Greek and Irish isolates with increased Tajima's D-values. This indicates a differentiation in the evolutionary pathway of Australian compared to Greek and Irish isolates within these genes.

Although serotype 4b strains predominate among human clinical isolates and serotype 1/2a strains among food isolates, gene-specific pattern between clinical isolates and 4b serotype strains or between food isolates and 1/2a serotype strains were not observed; food and clinical isolates could share alleles for all genes tested. However, descriptive analysis revealed that food and clinical isolates formed distinct clusters regarding their π and ω parameters for all the genes tested, with larger variations within prfA, actA, and plcB genes. This divergence might indicate that these genes were adapted differentially within each group, and this adaptation correlated with their prevalence in food or virulence phenotype, respectively. Previous studies investigating the correlation of isolation source and virulence of strains yielded differing conclusions. Some showed lower virulence potential for strains isolated from food environments compared to human clinical isolates (Norton et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2008). Conversely, Larsen et al. (2002) reported no significant correlation between food or human origin of strains and invasiveness in the Caco-2 cell infection model, while all strains managed equally to multiply once inside the host cells when an in vivo test was used. Similarly others found no systematic differences in virulence between food or clinical isolates (Brosch et al., 1993; Gray et al., 2004; Neves et al., 2008; Bueno et al., 2010).

The results of this study also showed that the most conserved genes were prfA and hly and the most diverse was actA. Proteins PrfA, LLO and ActA are considered essential virulence factors (Gaillard et al., 1986; Nishibori et al., 1995; Vázquez-Boland et al., 2001a; Travier and Lecuit, 2014). It seems that there is a selective pressure on L. monocytogenes to maintain the former genes, while the increased diversity of actA compared to the other genes is consistent with previous findings (Orsi et al., 2008) and is attributed to increased recombination events occurring in actA, and to evolution by positive selection in both lineages I and II. Rapid PCR-based methods utilize species-specific genes to detect L. monocytogenes in food samples, aiming at preventing the unnecessary recalls of food products. It is of great importance to use target sequences of highly conserved regions rather than genes prone to genetic variability (Rodríguez-Lázaro et al., 2004). Virulence associated genes (e.g. actA, hly, inlA, inlB, prfA, plcA, plcB) and 16S/23S rRNA genes have been studied toward the development of such methods (Liu, 2006). The results indicated that due to the diversity seen, PCR assays based on prfA or hly as opposed to actA would be more reliable, covering isolates of different origin, serotype or isolation source.

In the current study, actA showed the highest number of alleles among all genes tested; 13 alleles were observed for serotype 1/2a strains and 7 alleles for serotype 4b strains. One food isolate (AU_Lm14-002) had a single nucleotide deletion. Although this deletion would lead to a premature stop codon and a predicted truncated 487 amino acid protein, it was located immediately upstream of a poly(A) tract of 7 adenine residues. These mutations may have a role in influencing gene regulation, which allows phase switching and inactivation, and may be influencing actA transcription in this isolate, whereby a full length ActA may still be synthesized (Orsi et al., 2010). Twelve isolates representing 5 unique alleles had a 105 bp deletion, which comprises a 35 amino acid Proline-Rich Repeats (PRRs) fragment (Wiedmann et al., 1997; Jacquet et al., 2002; Orsi et al., 2008; Holen et al., 2010); the encoded proteins possess 3 instead of 4 PRRs. The number of PRRs contributes to bacterial movement (Lasa et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1996), however no significant effect on virulence potential of the strains has been shown (Roberts and Wiedmann, 2006; Holen et al., 2010). Among the isolates tested in this study, the 105 bp deletion was observed for 4 out of 18 isolates of 1/2a serotype and 8 out of 18 isolates of 4b serotype. Of these, 8 strains (which includes 3 alleles) were isolated from the food environment and 4 strains (2 alleles) were clinical isolates. Similar results were demonstrated by Wiedmann et al. (1997), who observed a predominance of 3-PRRs actA sequence among lineage I isolates compared to isolates of lineage II. This could indicate that this deletion does not influence the pathogenic potential of L. monocytogenes. Jacquet et al. (2002) observed that polymorphism in ActA proteins was rather correlated with origin (human or food isolates) than with serotype of the strains, while Conter et al. (2009) could not correlate actA polymorphism to the virulence of the strains. Based on the sequence analysis in the current study, no clear driving factor appeared to influence the nucleotide sequence or mutations in this gene, as all of the groups were dispersed regarding the parameters π, θ, and ω, while phylogenetic trees showed no consistent pattern between origin or environment of the strains and their genetic polymorphisms. These findings, along with the adapting character to certain functions previously suggested for this gene, and the increased recombination events (Orsi et al., 2008) might imply its multi-functionality recently reported (Travier et al., 2013).

Overall, this study provides insights into the selective pressures acting on the main virulence gene cluster of L. monocytogenes, and suggests differences based on serotype, geographic location and source. The selective pressure to minimize diversification was noted with the key virulence regulatory gene prfA, therefore results of this study support the key role of the global regulator prfA in the lifecycle of L. monocytogenes. In contrast to this, conservation of the actA gene sequence was lowest, with a greater sequence variation and number of alleles. Broadly speaking, higher conservation was noted among isolates sharing a serotype when compared with other groupings such as geographical location or source. Food and clinical isolates largely varied with respect to nucleotide diversity within prfA, actA, and plcB genes, possibly suggesting that a particular adaptation correlated with their prevalence in food or virulence phenotype, respectively. Geographical divergence was noted with respect to the hly gene, with serotype 4b Irish strains distinct to Greek and Australian strains. Future studies will be needed in order to clarify the correlation of geographical distribution of strains and their hly sequence, as well as the impact of such correlation on LLO functionality. Additionally, actA polymorphism should be further evaluated for other phenotypes that might result from its increased diversity among strains and diverse origins. In the present study, strains were selected to represent the distribution of L. monocytogenes based on prevalent serotypes and clinical or food associated origin. Further, a larger data set comprising strains of more serotypes, geographical or isolation origin and year of isolation should be investigated in order to infer significant conclusions regarding the impact of these parameters on LIPI-1 evolution and its correlation to virulence potential of the pathogen.

Author contributions

The study was conceived and designed by KJ, PS, and EF. All authors contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data. The work was drafted and revised by SP and EF. All authors approved and agreed in the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

SP would like to acknowledge the Greek State Scholarships Foundation (IKY) for providing her a Ph.D. fellowship.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was supported by the 7th Framework Programme projects PROMISE, contract number 265877.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01103/full#supplementary-material

References

- Brosch R., Catimel B., Milon G., Buchrieser C., Vindel E., Rocourt J. (1993). Virulence heterogeneity of Listeria monocytogenes strains from various sources (food, human, animal) in immunocompetent mice and its association with typing characteristics. J. Food Prot. 56, 296–301. 10.4315/0362-028X-56.4.297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant D., Moulton V. (2004). Neighbor-Net: an agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 255–265. 10.1093/molbev/msh018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno V. F., Banerjee P., Banada P. P., José De Mesquita A., Lemes-Marques E. G., Bhunia A. K. (2010). Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolates of food and human origins from Brazil using molecular typing procedures and in vitro cell culture assays. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 20, 43–59. 10.1080/09603120903281283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camejo A., Carvalho F., Reis O., Leitão E., Sousa S., Cabanes D. (2011). The arsenal of virulence factors deployed by Listeria monocytogenes to promote its cell infection cycle. Virulence 2, 379–394. 10.4161/viru.2.5.17703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty T., Ebel F., Wehland J., Dufrenne J., Notermans S. (1994). Naturally occurring virulence-attenuated isolates of Listeria monocytogenes capable of inducing long term protection against infection by virulent strains of homologous and heterologous serotypes. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 10, 1–9. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1994.tb00004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conter M., Vergara A., Di Ciccio P., Zanardi E., Ghidini S., Ianieri A. (2009). Polymorphism of actA gene is not related to in vitro virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 137, 100–105. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2009.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de las Heras A., Cain R. J., Bielecka M. K., Vázquez-Boland J. (2011). Regulation of Listeria virulence: PrfA master and commander. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14, 118–127. 10.1016/j.mib.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Bakker H. C., Didelot X., Fortes E. D., Nightingale K. K., Wiedmann M. (2008). Lineage specific recombination rates and microevolution in Listeria monocytogenes. BMC Evol. Biol. 8:277. 10.1186/1471-2148-8-277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumith M., Buchrieser C., Glaser P., Jacquet C., Martin P. (2004). Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 3819–3822. 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3819-3822.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebner R., Stephan R., Althaus D., Brisse S., Maury M., Tasara T. (2015). Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated during 2011-2014 from different food matrices in Switzerland. Food Control 57, 321–326. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2015.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA ECDC (2015). EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) and ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), (2015). The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2014. EFSA J. 13:4329 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farber J. M., Peterkin P. I. (1991). Listeria monocytogenes, a food-borne pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 55, 476–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E. M., Garvey P., Mckeown P., Cormican M., Leonard N., Jordan K. (2012). PFGE analysis of Listeria monocytogenes isolates of clinical, animal, food and environmental origin from Ireland. J. Med. Microbiol. 61, 540–547. 10.1099/jmm.0.036764-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox E., O'Mahony T., Clancy M., Dempsey R., Brien M. O., Jordan K. (2009). Listeria monocytogenes in the Irish dairy farm environment. J. Food Prot. 72, 1450–1456. 10.4315/0362-028X-72.7.1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard J. L., Berche P., Sansonetti P. (1986). Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 52, 50–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendel S. M., Ulaszek J. (2000). Ribotype analysis of strain distribution in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Prot. 63, 179–185. 10.4315/0362-028X-63.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbreth S. E., Call J. E., Wallace F. M., Scott V. N., Chen Y., Luchansky J. B. (2005). Relatedness of Listeria monocytogenes isolates recovered from selected ready-to-eat foods and listeriosis patients in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 8115–8122. 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8115-8122.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. J., Freitag N. E., Boor K. J. (2006). How the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes mediates the switch from environmental Dr. Jekyll to pathogenic Mr. Hyde. Infect. Immun. 74, 2505–2512. 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2505-2512.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M. J., Zadoks R. N., Fortes E. D., Dogan B., Cai S., Chen Y., et al. (2004). Listeria monocytogenes isolates from foods and humans form distinct but overlapping populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 5833–5841. 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5833-5841.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halberg Larsen M., Dalmasso M., Ingmer H., Langsrud S., Malakauskas M., Mader A., et al. (2014). Persistence of foodborne pathogens and their control in primary and secondary food production chains. Food Control 44, 92–109. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.03.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C., Cotter P. D., Sleator R. D., Gahan C. G. M. (2002). Bacterial stress response in Listeria monocytogenes: jumping the hurdles imposed by minimal processing. Int. Dairy, J. 12, 273–283. 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00125-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holen A., Gottlieb C. T., Larsen M. H., Ingmer H., Gram L. (2010). Poor invasion of trophoblastic cells but normal plaque formation in fibroblastic cells despite acta deletion in a group of Listeria monocytogenes strains persisting in some food processing environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 3391–3397. 10.1128/AEM.02862-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houhoula D., Peirasmaki D., Konteles S. J., Kizis D., Koussissis S., Bratacos M., et al. (2012). High level of heterogeneity among Listeria monocytogenes isolates from clinical and food origin specimens in Greece. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 848–852. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson D. H. (1998). SplitsTree: analyzing and visualizing evolutionary data. Bioinformatics 14, 68–73. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquet C., Gouin E., Jeannel D., Cossart P., Rocourt J. (2002). Expression of ActA, Ami, InlB, and Listeriolysin O in Listeria monocytogenes of human and food origin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 616–622. 10.1128/AEM.68.2.616-622.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat Z. W., Bhunia A. K. (2003). Adhesion, invasion and translocation characteristics of Listeria monocytogenes serotypes in Caco-2 cell and mouse models. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3640–3645. 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3640-3645.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaradat Z. W., Schutze G. E., Bhunia A. K. (2002). Genetic homogeneity among Listeria monocytogenes strains from infected patients and meat products from two geographic locations determined by phenotyping, ribotyping and PCR analysis of virulence genes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 76, 1–10. 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00050-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A., Larsen M. H., Ingmer H., Vogel B. F. (2007). Sodium chloride enhances adherence and aggregation and strain variation influences invasiveness of Listeria monocytogenes strains. J. Food Prot. 70, 592–599. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.3.592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen A., Thomsen L. E., Jørgensen R. L., Larsen M. H., Roldgaard B. B., Christensen B. B., et al. (2008). Processing plant persistent strains of Listeria monocytogenes appear to have a lower virulence potential than clinical strains in selected virulence models. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 123, 254–261. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearse M., Moir R., Wilson A., Stones-Havas S., Cheung M., Sturrock S., et al. (2012). Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28, 1647–1649. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss R., Tirczka T., Szita G., Bernáth S., Csikó G. (2006). Listeria monocytogenes food monitoring data and incidence of human listeriosis in Hungary, (2004). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 112, 71–74. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosakovsky Pond S. L., Frost S. D. W. (2005). Datamonkey: rapid detection of selective pressure on individual sites of codon alignments. Bioinforma. 21, 2531–2533. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen C. N., Nørrung B., Sommer H. M., Jakobsen M. (2002). In vitro and in vivo invasiveness of different pulsed-field gel electrophoresis types of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 5698–5703. 10.1128/AEM.68.11.5698-5703.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasa I., David V., Gouin E., Marchand J. B., Cossart P. (1995). The amino-terminal part of ActA is critical for the actin-based motility of Listeria monocytogenes; the central proline-rich region acts as a stimulator. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 425–436. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lianou A., Sofos J. N. (2007). A review of the incidence and transmission of Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat products in retail and food service environments. J. Food Prot. 70, 2172–2198. 10.4315/0362-028X-70.9.2172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P., Rozas J. (2009). DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. (2006). Identification, subtyping and virulence determination of Listeria monocytogenes, an important foodborne pathogen. J. Med. Microbiol. 55, 645–659. 10.1099/jmm.0.46495-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukinmaa S., Aarnisalo K., Suihko M. L., Siitonen A. (2004). Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes isolates of human and food origin studied by serotyping, automated ribotyping and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 10, 562–568. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matar G. M., Bibb W. F., Helsel L., Dewitt W., Swaminathan B. (1992). Immunoaffinity purification, stabilization and comparative characterization of listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes serotypes 1/2a and 4b. Res. Microbiol. 143, 489–498. 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlin J. (1990). Distribution of serovars of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from different categories of patients with listeriosis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 9, 210–213. 10.1007/BF01963840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLauchlin J. (2004). Listeria monocytogenes and listeriosis: a review of hazard characterisation for use in microbiological risk assessment of foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 92, 15–33. 10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00326-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereghetti L., Lanotte P., Savoye-Marczuk V., Marquet-van Der Mee N., Audurier A., Quentin R. (2002). Combined ribotyping and random multiprimer DNA analysis to probe the population structure of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 2849–2857. 10.1128/AEM.68.6.2849-2857.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møretrø T., Langsrud S. (2004). Listeria monocytogenes: biofilm formation and persistence in food-processing environments. Biofilms 1, 107–121. 10.1017/S1479050504001322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neves E., Silva A. C., Roche S. M., Velge P., Brito L. (2008). Virulence of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from the cheese dairy environment, other foods and clinical cases. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 411–415. 10.1099/jmm.0.47672-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale K. K., Windham K., Wiedmann M. (2005). Evolution and molecular phylogeny of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from human and animal listeriosis cases and foods. J. Bacteriol. 187, 5537–5551. 10.1128/JB.187.16.5537-5551.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishibori T., Cooray K., Xiong H., Kawamura I., Fujita M., Mitsuyama M. (1995). Correlation between the presence of virulence-associated genes as determined by PCR and actual virulence to mice in various strains of Listeria spp. Microbiol. Immunol. 39, 343–349. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton D. M., Scarlett J. M., Horton K., Sue D., Thimothe J., Boor K. J., et al. (2001). Characterization and pathogenic potential of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the smoked fish industry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 646–653. 10.1128/AEM.67.2.646-653.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olier M., Pierre F., Lemaître J. P., Divies C., Rousset A., Guzzo J. (2002). Assessment of the pathogenic potential of two Listeria monocytogenes human faecal carriage isolates. Microbiology 148, 1855–1862. 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olier M., Pierre F., Rousseaux S., Lemaître J. P., Rousset A., Piveteau P., et al. (2003). Expression of truncated internalin A is involved in impaired internalization of some Listeria monocytogenes isolates carried asymptomatically by humans. Infect. Immun. 71, 1217–1224. 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1217-1224.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi R. H., Bowen B. M., Wiedmann M. (2010). Homopolymeric tracts represent a general regulatory mechanism in prokaryotes. BMC Genomics 11:102. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi R. H., den Bakker H. C., Wiedmann M. (2011). Listeria monocytogenes lineages: genomics, evolution, ecology, and phenotypic characteristics. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301, 79–96. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsi R. H., Maron S. B., Nightingale K. K., Jerome M., Tabor H., Wiedmann M. (2008). Lineage specific recombination and positive selection in coding and intragenic regions contributed to evolution of the main Listeria monocytogenes virulence gene cluster. Infect. Genet. Evol. 8, 566–576. 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poimenidou S. V., Chatzithoma D.-N., Nychas G.-J., Skandamis P. N. (2016a). Adaptive response of Listeria monocytogenes to heat, salinity and low pH, after habituation on cherry tomatoes and lettuce leaves. PLoS ONE 11:e0165746. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poimenidou S. V., Chrysadakou M., Tzakoniati A., Bikouli V. C., Nychas G.-J., Skandamis P. N. (2016b). Variability of Listeria monocytogenes strains in biofilm formation on stainless steel and polystyrene materials and resistance to peracetic acid and quaternary ammonium compounds. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 237, 164–171. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy D. A., Chakraborty T., Goebel W., Cossart P. (1992). Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 60, 1263–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. J., Wiedmann M. (2003). Pathogen, host and environmental factors contributing to the pathogenesis of listeriosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60, 904–918. 10.1007/s00018-003-2225-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. J., Wiedmann M. (2006). Allelic exchange and site-directed mutagenesis probe the contribution of ActA amino-acid variability to phosphorylation and virulence-associated phenotypes among Listeria monocytogenes strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 254, 300–307. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2005.00041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A., Chan Y., Wiedmann M. (2005). Definition of genetically distinct attenuation mechanisms in naturally virulence-attenuated Listeria monocytogenes by comparative cell culture and molecular characterization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3900–3910. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3900-3910.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche S. M., Gracieux P., Albert I., Gouali M., Jacquet C., Martin P. M. V., et al. (2003). Experimental validation of low virulence in field strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun. 71, 3429–3436. 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3429-3436.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche S. M., Gracieux P., Milohanic E., Albert I., Témoin S., Grépinet O., et al. (2005). Investigation of specific substitutions in virulence genes characterizing phenotypic groups of low-virulence field strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 6039–6048. 10.1128/AEM.71.10.6039-6048.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Lázaro D., Hernández M., Scortti M., Esteve T., Vázquez-Boland J. A., Pla M. (2004). Quantitative detection of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua by real-time PCR: assessment of hly, iap, and lin02483 targets and amplifluor technology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1366–1377. 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1366-1377.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuchat A., Swaminathan B., Broome C. V. (1991). Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4, 169–183. 10.1128/CMR.4.2.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen K. L., Churchill G. A., Aquadro C. F. (1995). Properties of statistical tests of neutrality for DNA polymorphism data. Genetics 141, 413–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith G. A., Theriot J. A., Portnoy D. A. (1996). The tandem repeat domain in the Listeria monocytogenes ActA protein controls the rate of actin-based motility, the percentage of moving bacteria, and the localization of vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein and profilin. J. Cell Biol. 135, 647–660. 10.1083/jcb.135.3.647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez M., González-Zorn B., Vega Y., Chico-Calero I., Vázquez-Boland J. A. (2001). A role for ActA in epithelial cell invasion by Listeria monocytogenes. Cell. Microbiol. 3, 853–864. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan B., Gerner-Smidt P. (2007). The epidemiology of human listeriosis. Microbes Infect. 9, 1236–1243. 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. (1989). Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics 123, 585–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Témoin S., Roche S. M., Grépinet O., Fardini Y., Velge P. (2008). Multiple point mutations in virulence genes explain the low virulence of Listeria monocytogenes field strains. Microbiology 154, 939–948. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/011106-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travier L., Lecuit M. (2014). Listeria monocytogenes ActA: A new function for a “classic” virulence factor. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 17, 53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travier L., Guadagnini S., Gouin E., Dufour A., Chenal-Francisque V., Cossart P., et al. (2013). ActA promotes Listeria monocytogenes aggregation, intestinal colonization and carriage. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003131. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A., Cutcutache I., Koressaar T., Ye J., Faircloth B. C., Remm M., et al. (2012). Primer3 — new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 1–12. 10.1093/nar/gks596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Stelten A., Simpson J. M., Chen Y., Scott V. N., Whiting R. C., Ross W. H., et al. (2011). Significant shift in median guinea pig infectious dose shown by an outbreak-associated Listeria monocytogenes epidemic clone strain and a strain carrying a premature stop codon mutation in inlA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2479–2487. 10.1128/AEM.02626-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Boland J. A., Domínguez-Bernal G., González-Zorn B., Kreft J., Goebel W. (2001a). Pathogenicity islands and virulence evolution in Listeria. Microbes Infect. 3, 571–584. 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01413-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Boland J. A., Kuhn M., Berche P., Chakraborty T., Domínguez-Bernal G., Goebel W., et al. (2001b). Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 584–640. 10.1128/CMR.14.3.584-640.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward T. J., Gorski L., Borucki M. K., Robert E., Hutchins J., Pupedis K., et al. (2004). Intraspecific phylogeny and lineage group identification based on the prfA virulence gene cluster of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4994–5002. 10.1128/JB.186.15.4994-5002.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann M., Bruce J. L., Keating C., Johnson A. E., McDonough P. L., Batt C. A. (1997). Ribotypes and virulence gene polymorphisms suggest three distinct Listeria monocytogenes lineages with differences in pathogenic potential. Infect. Immun. 65, 2707–2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.