Abstract

The nuclear RNA-binding protein TDP43 is integrally involved in RNA processing. In accord with this central function, TDP43 levels are tightly regulated through a negative feedback loop, in which TDP43 recognizes its own RNA transcript, destabilizes it, and reduces new TDP43 protein production. In the neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), cytoplasmic mislocalization and accumulation of TDP43 disrupt autoregulation; conversely, inefficient TDP43 autoregulation can lead to cytoplasmic TDP43 deposition and subsequent neurodegeneration. Because TDP43 plays a multifaceted role in maintaining RNA metabolism, its mislocalization and accumulation interrupt several RNA processing pathways that in turn affect RNA stability and gene expression. TDP43-mediated disruption of these pathways — including alternative mRNA splicing, non-coding RNA processing, and RNA granule dynamics — may directly or indirectly contribute to ALS pathogenesis. Therefore, strategies that restore effective TDP43 autoregulation may ultimately prevent neurodegeneration in ALS and related disorders.

Keywords: RNA, nonsense mediated mRNA decay, alternative splicing, non-coding RNA, stress granule, autoregulation, disease, neurodegeneration

1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal neurodegenerative disorder in which the progressive loss of motor neurons results in paralysis and respiratory failure (Bruijn, Miller, and Cleveland 2004). There is no effective disease-modifying therapy for ALS, and its heterogeneous biochemical, genetic, and clinical features complicate the identification of therapeutic targets. However, it is increasingly clear that RNA dysregulation is a key contributor to ALS pathogenesis. Over the past decade, disease-associated mutations have been identified in genes encoding multiple RNA-binding proteins participating in all aspects of RNA processing (Kapeli, Martinez, and Yeo 2017). Among these is TDP43, a nuclear protein integrally involved in RNA metabolism. Although mutations in the gene encoding TDP43 (TARDBP) account for only a small proportion of the disease burden (2–5%), cytoplasmic TDP43 mislocalization and accumulation are observed in >90% of individuals with ALS (Neumann 2009). Moreover, mutations in several other ALS-associated genes — including C9orf72 (Murray et al. 2011), ANG (Seilhean et al. 2009), TBK1 (Van Mossevelde et al. 2016), PFN1 (Smith et al. 2015), UBQLN2 (Deng et al. 2011), VCP (J. O. Johnson et al. 2010), and hnRNPA2/B1 (Kim et al. 2013) — result in TDP43 pathology. This convergence heavily implicates TDP43 and TDP43-dependent RNA processing in neurodegenerative disease. In this review, we examine how TDP43 dysregulation impacts RNA metabolism, in particular the maintenance of RNA stability, and how these downstream events may contribute to ALS pathogenesis.

2. Mechanisms of TDP43 Autoregulation

TDP43 is an essential protein involved in several RNA processing events, including splicing, transcription, and translation. Since TDP43 recognizes UG-rich sequences present within approximately one third of all transcribed genes (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Tollervey et al. 2011; Sephton et al. 2011), it is uniquely able to influence the processing of hundreds to thousands of transcripts. In keeping with these fundamental functions, the level and localization of TDP43 are tightly regulated and critical for cell health. TDP43 knockout mice die early in embryogenesis, and partial or conditional knockout animals exhibit neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits that correlate with the neuroanatomical pattern of TDP43 ablation (Kraemer et al. 2010; Wu, Cheng, and Shen 2012; Iguchi et al. 2013; Sephton et al. 2010). Additionally, sustained TDP43 overexpression results in neurodegeneration in primary neuron (Barmada et al. 2010), mouse (Swarup et al. 2011; Wils et al. 2010), rat (Dayton et al. 2013; Tatom et al. 2009), Drosophila (Voigt et al. 2010; Y. Li et al. 2010), zebrafish (Kabashi et al. 2010; Schmid et al. 2013), and primate models (Uchida et al. 2012; Kasey L. Jackson et al. 2015), providing convincing evidence that too little or too much TDP43 is lethal.

Despite the observed sensitivity of neurons and other cell types to long-term changes in TDP43 protein levels, TDP43 expression and localization are dynamically regulated in the short-term by physical injury and other cellular stressors (Moisse et al. 2009; Swarup et al. 2012; V. E. Johnson et al. 2011). This pattern of expression suggests that TDP43 may be important for orchestrating the response to acute injury and eventual recovery. However, even relatively minor (~2-fold) persistent changes in TDP43 levels are sufficient to drive neurodegeneration (Janssens et al. 2013; Wegorzewska and Baloh 2011; Barmada et al. 2010, 2014), indicative of a coping response that over time becomes ineffective and eventually detrimental to cell health.

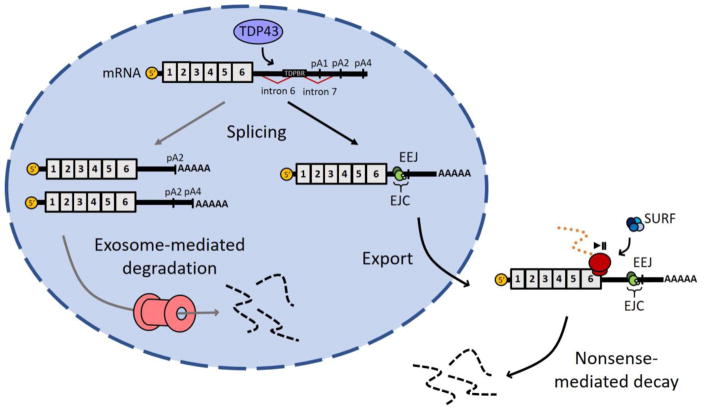

Similar to systems employed by related RNA-binding proteins, TDP43 regulates its own expression through an intricate negative feedback loop. At high levels, TDP43 recognizes sequences within the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of its own transcript (the TDP43 binding region, or TDPBR) (Bhardwaj et al. 2013; Ayala et al. 2011), triggering alternative splicing within the 3′ UTR (Tollervey et al. 2011; Polymenidou et al. 2011), mRNA destabilization, and reduced protein expression (Ayala et al. 2011; Polymenidou et al. 2011; Xu et al. 2010). Two separate mechanisms may account for this destabilization.

In the first, association of TDP43 with the TDPBR induces the removal of two alternative introns (6 and 7) within the last exon of the TARDBP mRNA transcript (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Koyama et al. 2016). These splicing events create perceived exon-exon junctions (EEJs) with subsequent deposition of exon-junction complexes (EJCs), structures composed of eukaryotic initiation factor 4A-III, Magoh, Y14, UPF2 and UPF3. During the process of translation, scanning ribosomes typically displace EJCs at EEJs upstream of a stop codon. Translation is stalled when the ribosome encounters a stop codon, allowing association of the SURF complex (SMG1, UPF1, and eRF1 and 2) with the ribosome. When an EJC is present >50 nt downstream of the stop codon, factors within the EJC (i.e. UPF2) may interact with UPF1 in the SURF complex, triggering UPF1 phosphorylation and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (Ivanov et al. 2008; Popp and Maquat 2013). In support of this model, knockdown of UPF1 — an essential NMD factor (Popp and Maquat 2013; Sun et al. 1998; Medghalchi et al. 2001) — increased the expression of constructs carrying the TARDBP 3′ UTR, while exogenous TDP43 reduced their expression (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Barmada et al. 2015).

This mechanism of autoregulation by RNA-binding proteins is not unique to TDP43, and forms the basis for a cascade labeled regulated unproductive splicing and transcription (RUST) that is also utilized by the splicing factors PTB and SC35 (Wollerton et al. 2004; Sureau et al. 2001; Ni et al. 2007; Lareau et al. 2007; Dredge et al. 2005). Like TDP43, these proteins recognize sequences present within the 3′ UTR of their respective transcripts, resulting in splicing and EJC deposition downstream of the canonical stop codon. This, in turn, causes RNA destabilization via NMD, and an overall reduction in protein levels. An analogous mechanism is responsible for the regulation of FUS, a nuclear RNA-binding protein whose cytoplasmic mislocalization and accumulation are implicated in ALS, much like TDP43 (Lagier-Tourenne and Cleveland 2009; Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2012; Kwiatkowski et al. 2009; Vance et al. 2009). FUS and TDP43 share basic structural and functional elements, including a glycine-rich low complexity domain that harbors ALS-associated mutations. FUS also binds its own transcript, resulting in exclusion of exon 7 and a shift in the reading frame (Zhou et al. 2013). This shift uncovers a premature stop codon in exon 8, leading to destabilization of the alternatively-spliced FUS mRNA via NMD. Furthermore, disease-associated mutations in FUS (Zhou et al. 2013) and TARDBP (Koyama et al. 2016) may impair effective autoregulation of these RNA-binding proteins, resulting in their accumulation and downstream toxicity (see below).

Nevertheless, alternatively-spliced TARDBP mRNA isoforms and predicted NMD substrates have been difficult to identify and measure, and additional studies suggest that TDP43 autoregulation operates by a separate mechanism. In the second model, TDP43-mediated splicing within the TARDBP 3′ UTR removes the primary mRNA polyadenylation site (pA1) present within intron 7 (Ayala et al. 2011; Avendaño-Vázquez et al. 2012). Transcripts that utilize the remaining polyadenylation sites pA2 and pA4 are preferentially retained in the nucleus (Avendaño-Vázquez et al. 2012) and degraded by the RNA exosome (Ayala et al. 2011). Genetic ablation of exosome components Rrp6 and Rrp44 is sufficient to increase exogenous TARDBP mRNA levels and protein production, implying that the RNA exosome is indeed responsible for degrading the overexpressed TARDBP minigene. However, more recent evidence suggests that differential polyadenylation cannot fully explain TDP43 autoregulation in this model (Bembich et al. 2014). Rather, TDP43-induced splicing of intron 7 within the TARDBP 3′ UTR destabilizes the transcript, reduces nuclear export, and decreases protein production. Artificial mutations that enhance intron 7 splicing promote TARDBP destabilization, while cDNA and other transcripts that intrinsically lack intron 7 escape autoregulation and are constitutively expressed at high levels (Bembich et al. 2014). This suggests that spliceosome assembly and intron 7 splicing is a key event in TDP43 autoregulation, but whether this process participates in the regulation of endogenous TDP43 levels is unclear, and further studies are required to fully elucidate its contribution.

3. Disruption of TDP43 Autoregulation in ALS

Regardless of whether TDP43 mRNA is destabilized by NMD or degraded by the exosome following nuclear retention, interruption of this autoregulatory process likely has severe consequences for cell health. Five disease-associated mutations have been identified within the TARDBP 3′ UTR (Pesiridis, Lee, and Trojanowski 2009), which may block binding of TDP43 to its own transcript and subsequent alternative splicing. At least one of these mutations is associated with a steady-state increase in TARDBP mRNA levels, supporting the notion of disrupted autoregulation as an underlying factor leading to TDP43 accumulation and disease (Gitcho et al. 2009). The majority of ALS-associated TARDBP mutations lie within the carboxy-terminal glycine rich domain of the protein (Barmada and Finkbeiner 2010), and although the precise mechanism remains unclear, several studies have suggested that these pathogenic mutations enhance cytoplasmic TDP43 mislocalization and aggregation (Barmada et al. 2010; W. Guo et al. 2011; Mutihac et al. 2015; Barmada et al. 2014) and stabilize cytoplasmic TDP43 (Austin et al. 2014; S.-C. Ling et al. 2010). By increasing the proportion of cytoplasmic TDP43, these changes would be expected to reduce autoregulation, resulting in elevated TDP43 production. Eventually, this vicious cycle may culminate in cytoplasmic TDP43 deposition, nuclear TDP43 clearance and neurodegeneration (E. B. Lee, Lee, and Trojanowski 2011).

Mutations in genes other than TARDBP may inhibit TDP43 autoregulation by affecting nucleocytoplasmic transport. The most prevalent mutation responsible for ALS, hexanucleotide (G4C2) expansions in the C9orf72 gene, may block nuclear protein import through one or more related mechanisms: repeat (G4C2)-containing RNA may sequester essential transport factors (i.e. RanGAP) (K. Zhang et al. 2015), or dipeptide repeat proteins produced by repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation of the repeat RNA might directly clog the nuclear pore (Shi et al. 2017). Additional evidence suggests that cytoplasmic protein aggregates may universally impair nucleocytoplasmic transport in neurodegenerative conditions (Woerner et al. 2016), further facilitating the cytoplasmic deposition of proteins such as TDP43 and FUS that typically participate in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. Because splicing takes place within the nucleus, cytoplasmic retention of FUS and TDP43 would interfere with the normal autoregulation process, ultimately increasing mRNA stability and protein production. Therefore, cytoplasmic sequestration of the proteins or inefficient nuclear import would be sufficient to inhibit autoregulation, accelerating the formation of TDP43 or FUS cytoplasmic inclusions that are characteristic of ALS (E. B. Lee, Lee, and Trojanowski 2011).

4. Downstream Consequences of Failed TDP43 Autoregulation: TDP43 Nuclear Exclusion and Cytoplasmic Accumulation

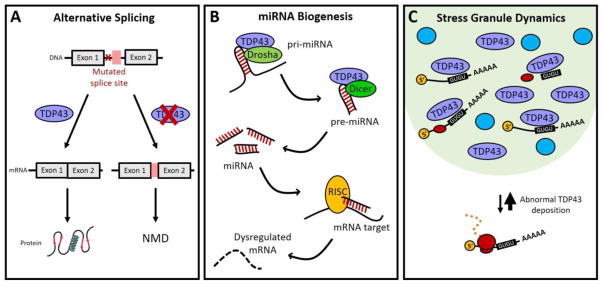

Disruption of TDP43 autoregulation influences both the protein level and localization of TDP43, resulting in cytoplasmic TDP43 deposition. Given TDP43’s crucial functions in RNA processing, its dysregulation leads to abnormalities in alternative mRNA splicing, non-coding RNAs, miRNA biogenesis, and the dynamics of RNA-rich granules.

4.1 Alternative Splicing

Alternative splicing is the differential inclusion or exclusion of exons within mature transcripts, enabling the expression of multiple RNA and protein isoforms from a single gene. Between 92 and 94% of all mRNAs in the human genome are alternatively spliced (Pan et al. 2008), and the brain expresses more alternatively spliced mRNAs than any other organ (M. B. Johnson et al. 2009; Yeo et al. 2004). Because changes in the splicing environment determine which isoforms are produced (Weg-Remers et al. 2001; van der Houven van Oordt et al. 2000), alternative splicing can regulate gene expression by creating transcripts that are more or less stable. In fact, an estimated 33% of alternatively-spliced transcripts contain premature termination codons that mark them as substrates for NMD (Lewis, Green, and Brenner 2003). Thus, NMD is not simply a mechanism for degrading abnormal or mutated transcripts, but also represents an active pathway regulating the stability of alternatively-spliced transcripts. Alternative splicing therefore represents an effective and rapid means of regulating gene expression via changes in RNA stability, without the need to revert to transcription. As mentioned above, RUST is an NMD-related mechanism utilized by RNA-binding proteins to dynamically and quickly modulate their own expression; signal transduction by inflammatory cytokines likewise affects gene expression via changes in splicing and RNA stability (Shakola, Suri, and Ruggiu 2015; Paulsen et al. 2013).

In addition to regulating the splicing of its own mRNA, TDP43 is crucial for the alternative splicing of hundreds of other transcripts (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2012; Arnold et al. 2013; Tollervey et al. 2011). It interacts strongly with several splicing factors (Freibaum et al. 2010), and loss of TDP43 causes widespread changes in alternative splicing (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Tollervey et al. 2011) including many transcripts that are critical for neuronal viability (Polymenidou et al. 2011; Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2012; Chang et al. 2014). ALS-associated TARDBP mutations can likewise alter alternative splicing and subsequent gene expression (Arnold et al. 2013; Highley et al. 2014).

Alternatively spliced transcripts can also be targeted for decay if they include mutations that create novel splice sites. This can lead to the inclusion of unannotated or “cryptic” exons and the production of faulty transcripts. Recent work suggests that TDP43 actively suppresses unannotated exon splicing events (J. P. Ling et al. 2015; Tan et al. 2016). Its depletion results in a widespread increase in cryptic exon splicing, and the inclusion of these exons typically leads to NMD (Humphrey et al. 2017). Many of these events are specific to neurons (Jeong et al. 2017), suggesting that the disruption of TDP43-mediated cryptic exon regulation may directly contribute to neurodegeneration. Furthermore, the unannotated exons affected by TDP43 are distinct in murine and human cells (J. P. Ling et al. 2015), indicating species-specific differences in TDP43 function that may predispose to mechanisms of neurodegeneration unique to humans. TDP43 is not the only RNA-binding protein that modulates exon inclusion — RBM17, PTBP1 and PTBP2 also repress the inclusion of unannotated exons (J. P. Ling et al. 2015; Tan et al. 2016). Like TDP43, each of these factors is essential for neuronal development and their loss results in neurodegeneration (Q. Li et al. 2014; Suckale et al. 2011; J. P. Ling et al. 2016; Tan et al. 2016), implying that neurons are particularly susceptible to the abnormal inclusion of unannotated exons.

4.2 Non-Coding RNAs

Though attention is often focused on the 1–2% of transcripts that encode protein, the vast majority of the genome is transcribed as non-protein-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) (Esteller 2011). These transcripts are loosely categorized as short or long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and the latter act by regulating gene expression in a variety of ways. These include, but are not limited to: the sequestration (Hung et al. 2011), competition (Kino et al. 2010), or altered localization of transcription factors (Z. Liu et al. 2011); transcriptional coactivation (Hubé et al. 2011) or corepression (X. Wang et al. 2008); alternative mRNA splicing (Annilo, Kepp, and Laan 2009); mRNA transport and stability (Gong and Maquat 2011); and modulation of translation (Ebralidze et al. 2008). lncRNAs serve crucial functions in development and disease, and also help scaffold membraneless organelles such as nuclear speckles and paraspeckles (Kung, Colognori, and Lee 2013) that are important sites of RNA processing and modification (Galganski, Urbanek, and Krzyzosiak 2017).

Both TDP43 and FUS recognize lncRNAs (Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2012; Tollervey et al. 2011; Hoell et al. 2011), including gadd7 (X. Liu et al. 2012), MALAT1 (F. Guo et al. 2015), and NEAT1_2 (Nishimoto et al. 2013), via UG-rich binding sites (Tollervey et al. 2011; Lagier-Tourenne et al. 2012). The abundance of many lncRNAs is altered in response to TDP43 knockdown in murine models of ALS (Polymenidou et al. 2011) and in human post-mortem tissue (Tollervey et al. 2011). Thus, TDP43 deposition in ALS likely has profound consequences for lncRNA expression and function. However, further studies are required to determine how TDP43 pathology influences lncRNA-related processes, and whether TDP43-mediated impairment of lncRNA contributes significantly to neurodegeneration in ALS.

4.3 miRNA Biogenesis

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNAs that base-pair with complementary sequences within mRNA transcripts to trigger their decay and/or translational repression. These 20–25 nt RNAs are produced from an RNA precursor (pri-miRNA) that forms a hairpin loop shortly after transcription (Cai, Hagedorn, and Cullen 2004; Y. Lee et al. 2004). The enzyme Drosha then cleaves the hairpin from the rest of the transcript (Y. Lee et al. 2003; Gregory, Chendrimada, and Shiekhattar 2006), and the resulting molecule (pre-miRNA) is exported to the cytoplasm (Murchison and Hannon 2004). There, the enzyme Dicer cuts away the looped end (Lund and Dahlberg 2006), leaving a duplex of two short, complementary RNA strands. The two strands dissociate and the mature miRNA associates with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), which assists in orienting the miRNA with its mRNA target, repressing translation of the target transcript and triggering its degradation.

TDP43 promotes miRNA biogenesis through a direct association with pri-miRNA, pre-miRNA, and both Drosha and Dicer (Kawahara and Mieda-Sato 2012). In so doing, TDP43 regulates the formation of key miRNAs that are essential for neuronal development, activity and survival (Fan, Chen, and Chen 2014; Buratti et al. 2010; Kawahara and Mieda-Sato 2012; Gascon and Gao 2014; Z. Zhang et al. 2013). FUS also interacts with Drosha and pri-miRNA in neurons, suggesting that it plays a similar role in neuronal miRNA biogenesis (Morlando et al. 2012).

Concordant with TDP43 pathology, the expression of several TDP43-associated miRNAs were altered in the CSF of sporadic ALS patients, compared to healthy controls (Freischmidt et al. 2013; Figueroa-Romero et al. 2016). Similar changes in miRNA levels were detected in transgenic mutant SOD1 mouse spinal cord and human ALS monocytes, but not fibroblasts from ALS patients (Butovsky et al. 2012; Koval et al. 2013). Human neurons carrying TARDBP mutations exhibited reduced levels of miR-9 and the immature pri-miRNA precursor pri-miR-9-2 (Z. Zhang et al. 2013). Knockdown of endogenous TARDBP in control neurons reproduced these deficits, suggesting that TDP43 actively participates in miR-9 biogenesis, and that disease-associated TARDBP mutations inhibit this function. One of the predicted targets of miRNAs disrupted in ALS tissues is EIF2/AGO4 (Figueroa-Romero et al. 2016), a component of RISC that participates in miRNA-mediated RNA degradation (Sasaki et al. 2003). Thus, abnormal miRNA biogenesis triggered by TDP43 dysfunction in ALS may have direct and indirect consequences for the maintenance of RNA stability. Further, since each individual miRNA can regulate the stability and translation of many downstream mRNA targets, the potential implications of even minor abnormalities in miRNA biogenesis are considerable (Paez-Colasante et al. 2015).

4.4 Stress Granule Dynamics

Cells undergo a wide range of molecular changes in response to environmental stressors, including the inhibition of conventional translation (Koritzinsky et al. 2007; Spriggs, Bushell, and Willis 2010) and the formation of stress granules (SGs), cytoplasmic ribonucleoprotein particles rich in mRNA, RNA-binding proteins, and stalled translation initiation complexes (Kedersha et al. 1999; Harding et al. 2000; Mazroui et al. 2006). TDP43 is one of several RNA-binding proteins that localize to SGs in response to various conditions (Colombrita et al. 2009; Dewey et al. 2011; Liu-Yesucevitz et al. 2010; McDonald et al. 2011). Although it is not essential for SG formation per se, changes in TDP43 levels or localization affect SG dynamics. For instance, TARDBP knockdown slows SG formation (Colombrita et al. 2009; McDonald et al. 2011), while expression of ALS-associated mutant TDP43 accelerates SG formation and results in larger SGs than wild-type TDP43 overexpression (Dewey et al. 2011; Liu-Yesucevitz et al. 2010). Based on its ability to recognize thousands of GU-rich transcripts, it is possible that excess TDP43 inclusion within SGs enables broad mRNA sequestration, shifting transcripts from actively translating polysomes to the relatively inert SGs. Conversely, SG-localized TDP43 may also bind to and prevent the degradation of RNAs that would have otherwise been degraded through association with components of processing (P)-bodies, including decapping proteins and exonucleases. Therefore, cytoplasmic TDP43 accumulation within normal or abnormal SGs in ALS might effectively increase mRNA stability without causing a reciprocal increase in mRNA translation. Nevertheless, any potential RNA stabilizing effect of TDP43 deposition is likely to be outweighed by the substantive TDP43-dependent changes in alternative splicing, unannotated exon inclusion, and miRNA biogenesis that collectively act to destabilize RNA.

4.5 RNA Transport Granules

Localized translation of mRNA is a common mechanism for regulating protein expression in specific regions of the cell. This is of particular importance in highly compartmentalized cells such as neurons, in which local translation is essential for synaptic plasticity (Klann and Dever 2004), neurotransmitter production (Mohr, Fehr, and Richter 1991), axon guidance, and recovery from injury (Willis et al. 2005). mRNAs are transported in granules comprised primarily of RNA-binding proteins (Ainger et al. 1993) that stabilize and translationally repress (Huang et al. 2003; Krichevsky and Kosik 2001) their cargo. TDP43 colocalizes with mRNA and related RNA-binding proteins in transport granules that undergo bidirectional, microtubule-dependent transport (Alami et al. 2014; Fallini, Bassell, and Rossoll 2012), suggesting that TDP43 acts as a neuronal mRNA transport factor (I.-F. Wang et al. 2008). Disease-associated TARDBP mutations impair the motility of TDP43-positive axonal granules (Alami et al. 2014), and the overexpression of TDP43 C-terminal fragments sequester components of transport granules such as HuD (Fallini, Bassell, and Rossoll 2012). Taken together with evidence showing that wild-type or mutant TDP43 overexpression impairs axon outgrowth (Fallini, Bassell, and Rossoll 2012), these observations imply that TDP43-dependent dysregulation of mRNA transport and local protein synthesis may contribute to axon degeneration in ALS.

5. Therapeutic Implications

Consistent with a potential contribution of NMD to ALS pathogenesis, modifications to this pathway have consistently demonstrated protective effects in ALS models. Components of the NMD pathway (UPF1 and UPF2) were originally identified in an unbiased screen for genes that rescue FUS-mediated toxicity in yeast (Ju et al. 2011). Subsequent studies demonstrated that UPF1 overexpression significantly prevented TDP43- and FUS-dependent cell death in rodent primary neuron ALS models (Barmada et al. 2015). As in yeast, this protective effect was also observed in response to UPF2. Moreover, the rescue was blocked by inhibition of NMD, suggesting that UPF1 and UPF2 act through NMD to improve survival. Neuroprotection by UPF1 was also confirmed in an in vivo model of ALS. Here, the expression of UPF1 in rats effectively prevented TDP43-mediated forelimb paralysis (K. L. Jackson et al. 2015). Although the mechanism by which UPF1 overexpression extends neuronal survival and improves outcomes in these models is unknown, one possibility is that UPF1 overexpression enables the cells to cope with the influx of NMD substrates elicited by TDP43 dysfunction and unannotated alternative splicing. Alternatively, UPF1 may enhance NMD-dependent degradation of the TARDBP transcript itself, facilitating TDP43 autoregulation and preventing further TDP43 deposition.

A second therapeutic approach seeks to compensate for the loss of functional TDP43 within the nucleus of affected neurons in ALS. As previously discussed, TDP43 is a repressor of cryptic exon splicing, and its depletion results in a widespread excess of unannotated splicing events. Fusion of the amino-terminus of TDP43 to the splicing repressor domain from the ribonucleoprotein Raver1 results in a chimeric protein that retains much of the function of full-length TDP43. In cells depleted of TDP43, the TDP43-Raver1 fusion is localized to the nucleus, is capable of recognizing UG repeats, and effectively blocked cryptic exon inclusion elicited by TDP43 knockout (J. P. Ling et al. 2015). Further, TDP43-Raver1 expression prevented apoptosis in these cells, suggesting that the chimera can functionally substitute for TDP43. These results further imply that cryptic exon inclusion contributes to cell death, and the introduction of a splicing repressor capable of inhibiting these events may be therapeutically advantageous in the absence of native TDP43 function.

Figure 1. TDP43 autoregulation.

TDP43 may destabilize its own mRNA transcript through two distinct mechanisms. In the first (gray arrows), TDP43 protein recognizes the TDP43 binding region (TDPBR) within the 3′ UTR of its own transcript, stimulating the removal of alternative intron 7 and the primary polyadenylation site (pA1) contained within the intron. Spliced transcripts are preferentially retained in the nucleus and targeted for exosome-mediated decay. In the second mechanism (black arrows), the removal of introns 6 and/or 7 creates exon-exon junctions (EEJs) and the assembly of exon junction complexes (EJCs). The transcript is then exported to the cytoplasm. During the first or pioneer round of translation, the ribosome pauses at the stop codon, allowing the association of the SURF complex with the ribosome. Factors within the downstream EJC interact with UPF1 in the SURF complex, triggering UPF1 phosphorylation and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay.

Figure 2. TDP43 deposition impacts RNA stability through several pathways.

(A) Alternative splicing. Mutations that introduce novel splice sites can lead to the inclusion of unannotated or “cryptic” exons (pink box). These faulty transcripts are often targeted by NMD. Typically, TDP43 is a strong repressor of these unannotated splicing events, but nuclear exclusion prevents TDP43 from performing this function, and abnormal transcripts accumulate. (B) miRNA biogenesis. TDP43 promotes several steps of miRNA biogenesis, and regulates the formation of key miRNAs that, in turn, control the stability and translation of mRNAs that are essential for neuronal survival, growth and development. (C) Stress granule dynamics. TDP43 is one of several RNA-binding proteins (blue circles) that localize to SGs (light green) in response to various conditions. Because TDP43 recognizes thousands of GU-rich transcripts, cytoplasmic TDP43 deposition within SGs forces mRNA recruitment to SGs, shifting transcripts from actively translating polysomes to inert, though stable, SGs.

Highlights.

TDP43 is an important regulator of RNA processing whose expression is regulated through an intricate negative feedback loop.

Cytoplasmic mislocalization and accumulation of TDP43 are characteristic features of ALS.

TDP43 pathology influences RNA stability and gene expression via alternative mRNA splicing, non-coding RNA processing, and RNA granule dynamics.

Targeting these pathways may enable the development of novel neuroprotective therapies for ALS.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health / National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NIH/NINDS) R01NS097542 (SB), and Active Against ALS (KW).

Abbreviations

- ALS

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- 3′ UTR

3′ untranslated region

- TDPBR

TDP43 binding region

- EEJ

exon-exon junction

- EJC

exon junction complex

- NMD

nonsense-mediated decay

- RUST

regulated unproductive splicing and translation

- RAN translation

repeat-associated non-AUG translation

- ncRNA

non-coding RNA

- lncRNA

long non-coding RNA

- miRNA

microRNA

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- SG

stress granule

- P-body

processing body

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- Ainger K, Avossa D, Morgan F, Hill SJ, Barry C, Barbarese E, Carson JH. Transport and Localization of Exogenous Myelin Basic Protein mRNA Microinjected into Oligodendrocytes. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1993;123(2):431–41. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alami Nael H, Smith Rebecca B, Carrasco Monica A, Williams Luis A, Winborn Christina S, Han Steve SW, Kiskinis Evangelos, et al. Axonal Transport of TDP-43 mRNA Granules Is Impaired by ALS-Causing Mutations. Neuron. 2014;81(3):536–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annilo Tarmo, Kepp Katrin, Laan Maris. Natural Antisense Transcript of Natriuretic Peptide Precursor A (NPPA): Structural Organization and Modulation of NPPA Expression. BMC Molecular Biology. 2009;10(August):81. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-10-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold Eveline S, Ling Shuo-Chien, Huelga Stephanie C, Lagier-Tourenne Clotilde, Polymenidou Magdalini, Ditsworth Dara, Kordasiewicz Holly B, et al. ALS-Linked TDP-43 Mutations Produce Aberrant RNA Splicing and Adult-Onset Motor Neuron Disease without Aggregation or Loss of Nuclear TDP-43. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(8):E736–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222809110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin James A, Wright Gareth SA, Watanabe Seiji, Günter Grossmann J, Antonyuk Svetlana V, Yamanaka Koji, Samar Hasnain S. Disease Causing Mutants of TDP-43 Nucleic Acid Binding Domains Are Resistant to Aggregation and Have Increased Stability and Half-Life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(11):4309–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317317111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avendaño-Vázquez S Eréndira, Dhir Ashish, Bembich Sara, Buratti Emanuele, Proudfoot Nicholas, Baralle Francisco E. Autoregulation of TDP-43 mRNA Levels Involves Interplay between Transcription, Splicing, and Alternative polyA Site Selection. Genes & Development. 2012;26(15):1679–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.194829.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala Youhna M, De Conti Laura, Eréndira Avendaño-Vázquez S, Dhir Ashish, Romano Maurizio, D’Ambrogio Andrea, Tollervey James, et al. The EMBO Journal. 2. Vol. 30. EMBO Press; 2011. TDP-43 Regulates Its mRNA Levels through a Negative Feedback Loop; pp. 277–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada Sami J, Finkbeiner Steven. Pathogenic TARDBP Mutations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia: Disease-Associated Pathways. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2010;21(4):251–72. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2010.21.4.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada Sami J, Ju Shulin, Arjun Arpana, Batarse Anthony, Archbold Hilary C, Peisach Daniel, Li Xingli, et al. Amelioration of Toxicity in Neuronal Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis by hUPF1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(25):7821–26. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509744112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada Sami J, Serio Andrea, Arjun Arpana, Bilican Bilada, Daub Aaron, Michael Ando D, Tsvetkov Andrey, et al. Autophagy Induction Enhances TDP43 Turnover and Survival in Neuronal ALS Models. Nature Chemical Biology. 2014;10(8):677–85. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmada Sami J, Skibinski Gaia, Korb Erica, Rao Elizabeth J, Wu Jane Y, Finkbeiner Steven. Cytoplasmic Mislocalization of TDP-43 Is Toxic to Neurons and Enhanced by a Mutation Associated with Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(2):639–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4988-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bembich Sara, Herzog Jeremias S, De Conti Laura, Stuani Cristiana, Eréndira Avendaño-Vázquez S, Buratti Emanuele, Baralle Marco, Baralle Francisco E. Predominance of Spliceosomal Complex Formation over Polyadenylation Site Selection in TDP-43 Autoregulation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2014;42(5):3362–71. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj Amit, Myers Michael P, Buratti Emanuele, Baralle Francisco E. Characterizing TDP-43 Interaction with Its RNA Targets. Nucleic Acids Research. 2013;41(9):5062–74. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn Lucie I, Miller Timothy M, Cleveland Don W. Unraveling the Mechanisms Involved in Motor Neuron Degeneration in ALS. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2004;27:723–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buratti Emanuele, De Conti Laura, Stuani Cristiana, Romano Maurizio, Baralle Marco, Baralle Francisco. Nuclear Factor TDP-43 Can Affect Selected microRNA Levels. The FEBS Journal. 2010;277(10):2268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky Oleg, Siddiqui Shafiuddin, Gabriely Galina, Lanser Amanda J, Dake Ben, Murugaiyan Gopal, Doykan Camille E, et al. Modulating Inflammatory Monocytes with a Unique microRNA Gene Signature Ameliorates Murine ALS. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(9):3063–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI62636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Xuezhong, Hagedorn Curt H, Cullen Bryan R. Human microRNAs Are Processed from Capped, Polyadenylated Transcripts That Can Also Function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10(12):1957–66. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Jer-Cherng, Hazelett Dennis J, Stewart Judith A, Morton David B. Motor Neuron Expression of the Voltage-Gated Calcium Channel Cacophony Restores Locomotion Defects in a Drosophila, TDP-43 Loss of Function Model of ALS. Brain Research. 2014;1584(October):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombrita Claudia, Zennaro Eleonora, Fallini Claudia, Weber Markus, Sommacal Andreas, Buratti Emanuele, Silani Vincenzo, Ratti Antonia. TDP-43 Is Recruited to Stress Granules in Conditions of Oxidative Insult. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009;111(4):1051–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayton Robert D, Gitcho Michael A, Orchard Elysse A, Wilson Jon D, Wang David B, Cain Cooper D, Johnson Jeffrey A, et al. Selective Forelimb Impairment in Rats Expressing a Pathological TDP-43-25 kDa C-Terminal Fragment to Mimic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2013;21(7):1324–34. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Han-Xiang, Chen Wenjie, Hong Seong-Tshool, Boycott Kym M, Gorrie George H, Siddique Nailah, Yang Yi, et al. Mutations in UBQLN2 Cause Dominant X-Linked Juvenile and Adult-Onset ALS and ALS/dementia. Nature. 2011;477(7363):211–15. doi: 10.1038/nature10353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey Colleen M, Cenik Basar, Sephton Chantelle F, Dries Daniel R, Mayer Paul, 3rd, Good Shannon K, Johnson Brett A, Herz Joachim, Yu Gang. TDP-43 Is Directed to Stress Granules by Sorbitol, a Novel Physiological Osmotic and Oxidative Stressor. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2011;31(5):1098–1108. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01279-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dredge B Kate, Stefani Giovanni, Engelhard Caitlin C, Darnell Robert B. Nova Autoregulation Reveals Dual Functions in Neuronal Splicing. The EMBO Journal. 2005;24(8):1608–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebralidze Alexander K, Guibal Florence C, Steidl Ulrich, Zhang Pu, Lee Sanghoon, Bartholdy Boris, Jorda Meritxell Alberich, et al. PU.1 Expression Is Modulated by the Balance of Functional Sense and Antisense RNAs Regulated by a Shared Cis-Regulatory Element. Genes & Development. 2008;22(15):2085–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.1654808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esteller Manel. Non-Coding RNAs in Human Disease. Nature Reviews. Genetics. 2011;12(12):861–74. doi: 10.1038/nrg3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallini Claudia, Bassell Gary J, Rossoll Wilfried. The ALS Disease Protein TDP-43 Is Actively Transported in Motor Neuron Axons and Regulates Axon Outgrowth. Human Molecular Genetics. 2012;21(16):3703–18. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Zhen, Chen Xiaowei, Chen Runsheng. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis of TDP-43 Binding Small RNAs Identifies miR-NID1 (miR-8485), a Novel miRNA That Represses NRXN1 Expression. Genomics. 2014;103(1):76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa-Romero Claudia, Hur Junguk, Simon Lunn J, Paez-Colasante Ximena, Bender Diane E, Yung Raymond, Sakowski Stacey A, Feldman Eva L. Expression of microRNAs in Human Post-Mortem Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Spinal Cords Provides Insight into Disease Mechanisms. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2016;71(March):34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freibaum Brian D, Chitta Raghu K, High Anthony A, Paul Taylor J. Global Analysis of TDP-43 Interacting Proteins Reveals Strong Association with RNA Splicing and Translation Machinery. Journal of Proteome Research. 2010;9(2):1104–20. doi: 10.1021/pr901076y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freischmidt Axel, Müller Kathrin, Ludolph Albert C, Weishaupt Jochen H. Systemic Dysregulation of TDP-43 Binding microRNAs in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Acta Neuropathologica Communications. 2013;1(July):42. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galganski Lukasz, Urbanek Martyna O, Krzyzosiak Wlodzimierz J. Nuclear Speckles: Molecular Organization, Biological Function and Role in Disease. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45(18):10350–68. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascon Eduardo, Gao Fen-Biao. Journal of Neurogenetics. 1–2. Vol. 28. Taylor & Francis; 2014. The Emerging Roles of MicroRNAs in the Pathogenesis of Frontotemporal Dementia–Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (FTD-ALS) Spectrum Disorders; pp. 30–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitcho Michael A, Bigio Eileen H, Mishra Manjari, Johnson Nancy, Weintraub Sandra, Mesulam Marsel, Rademakers Rosa, et al. Acta Neuropathologica. 5. Vol. 118. Springer-Verlag; 2009. TARDBP 3′-UTR Variant in Autopsy-Confirmed Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration with TDP-43 Proteinopathy; p. 633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Chenguang, Maquat Lynne E. lncRNAs Transactivate STAU1-Mediated mRNA Decay by Duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu Elements. Nature. 2011;470(7333):284–88. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory Richard I, Chendrimada Thimmaiah P, Shiekhattar Ramin. MicroRNA Biogenesis: Isolation and Characterization of the Microprocessor Complex. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2006;342:33–47. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Fengjie, Jiao Feng, Song Zuoqing, Li Shujun, Liu Bin, Yang Hongwei, Zhou Qinghua, Li Zhigang. Regulation of MALAT1 Expression by TDP43 Controls the Migration and Invasion of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells in Vitro. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2015;465(2):293–98. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Weirui, Chen Yanbo, Zhou Xiaohong, Kar Amar, Ray Payal, Chen Xiaoping, Rao Elizabeth J, et al. An ALS-Associated Mutation Affecting TDP-43 Enhances Protein Aggregation, Fibril Formation and Neurotoxicity. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2011;18(7):822–30. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Zeng H, Wek R, Schapira M, Ron D. Regulated Translation Initiation Controls Stress-Induced Gene Expression in Mammalian Cells. Molecular Cell. 2000;6(5):1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Highley J Robin, Kirby Janine, Jansweijer Joeri A, Webb Philip S, Hewamadduma Channa A, Heath Paul R, Higginbottom Adrian, et al. Loss of Nuclear TDP-43 in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Causes Altered Expression of Splicing Machinery and Widespread Dysregulation of RNA Splicing in Motor Neurones. Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 2014;40(6):670–85. doi: 10.1111/nan.12148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoell Jessica I, Larsson Erik, Runge Simon, Nusbaum Jeffrey D, Duggimpudi Sujitha, Farazi Thalia A, Hafner Markus, Borkhardt Arndt, Sander Chris, Tuschl Thomas. RNA Targets of Wild-Type and Mutant FET Family Proteins. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2011;18(12):1428–31. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oordt Houven, van der W, Diaz-Meco MT, Lozano J, Krainer AR, Moscat J, Cáceres JF. The MKK(3/6)-p38-Signaling Cascade Alters the Subcellular Distribution of hnRNP A1 and Modulates Alternative Splicing Regulation. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2000;149(2):307–16. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Yi-Shuian, Carson John H, Barbarese Elisa, Richter Joel D. Facilitation of Dendritic mRNA Transport by CPEB. Genes & Development. 2003;17(5):638–53. doi: 10.1101/gad.1053003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubé Florent, Velasco Guillaume, Rollin Jérôme, Furling Denis, Francastel Claire. Steroid Receptor RNA Activator Protein Binds to and Counteracts SRA RNA-Mediated Activation of MyoD and Muscle Differentiation. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39(2):513–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey Jack, Emmett Warren, Fratta Pietro, Isaacs Adrian M, Plagnol Vincent. Quantitative Analysis of Cryptic Splicing Associated with TDP-43 Depletion. BMC Medical Genomics. 2017;10(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12920-017-0274-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung Tiffany, Wang Yulei, Lin Michael F, Koegel Ashley K, Kotake Yojiro, Grant Gavin D, Horlings Hugo M, et al. Extensive and Coordinated Transcription of Noncoding RNAs within Cell-Cycle Promoters. Nature Genetics. 2011;43(7):621–29. doi: 10.1038/ng.848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi Yohei, Katsuno Masahisa, Niwa Jun-Ichi, Takagi Shinnosuke, Ishigaki Shinsuke, Ikenaka Kensuke, Kawai Kaori, et al. Loss of TDP-43 Causes Age-Dependent Progressive Motor Neuron Degeneration. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2013;136(Pt 5):1371–82. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov Pavel V, Gehring Niels H, Kunz Joachim B, Hentze Matthias W, Kulozik Andreas E. Interactions between UPF1, eRFs, PABP and the Exon Junction Complex Suggest an Integrated Model for Mammalian NMD Pathways. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27(5):736–47. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson Kasey L, Dayton Robert D, Fisher-Perkins Jeanne M, Didier Peter J, Baker Kate C, Weimer Maria, Gutierrez Amparo, et al. Journal of Medical Primatology. 2. Vol. 44. Wiley Online Library; 2015. Initial Gene Vector Dosing for Studying Symptomatology of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Non-Human Primates; pp. 66–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KL, Dayton RD, Orchard EA, Ju S, Ringe D, Petsko GA, Maquat LE, Klein RL. Preservation of Forelimb Function by UPF1 Gene Therapy in a Rat Model of TDP-43-Induced Motor Paralysis. Gene Therapy. 2015;22(1):20–28. doi: 10.1038/gt.2014.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens Jonathan, Wils Hans, Kleinberger Gernot, Joris Geert, Cuijt Ivy, Groote Chantal Ceuterick-de, Van Broeckhoven Christine, Kumar-Singh Samir. Overexpression of ALS-Associated p.M337V Human TDP-43 in Mice Worsens Disease Features Compared to Wild-Type Human TDP-43 Mice. Molecular Neurobiology. 2013;48(1):22–35. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8427-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong Yun Ha, Ling Jonathan P, Lin Sophie Z, Donde Aneesh N, Braunstein Kerstin E, Majounie Elisa, Traynor Bryan J, LaClair Katherine D, Lloyd Thomas E, Wong Philip C. Tdp-43 Cryptic Exons Are Highly Variable between Cell Types. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2017;12(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13024-016-0144-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Janel O, Mandrioli Jessica, Benatar Michael, Abramzon Yevgeniya, Van Deerlin Vivianna M, Trojanowski John Q, Raphael Gibbs J, et al. Exome Sequencing Reveals VCP Mutations as a Cause of Familial ALS. Neuron. 2010;68(5):857–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Matthew B, Kawasawa Yuka Imamura, Mason Christopher E, Krsnik Zeljka, Coppola Giovanni, Bogdanović Darko, Geschwind Daniel H, Mane Shrikant M, State Matthew W, Sestan Nenad. Functional and Evolutionary Insights into Human Brain Development through Global Transcriptome Analysis. Neuron. 2009;62(4):494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Victoria E, Stewart William, Trojanowski John Q, Smith Douglas H. Acute and Chronically Increased Immunoreactivity to Phosphorylation-Independent but Not Pathological TDP-43 after a Single Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;122(6):715–26. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0909-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju Shulin, Tardiff Daniel F, Han Haesun, Divya Kanneganti, Zhong Quan, Maquat Lynne E, Bosco Daryl A, et al. A Yeast Model of FUS/TLS-Dependent Cytotoxicity. PLoS Biology. 2011;9(4):e1001052. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabashi Edor, Lin Li, Tradewell Miranda L, Dion Patrick A, Bercier Valérie, Bourgouin Patrick, Rochefort Daniel, et al. Gain and Loss of Function of ALS-Related Mutations of TARDBP (TDP-43) Cause Motor Deficits in Vivo. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(4):671–83. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapeli Katannya, Martinez Fernando J, Yeo Gene W. Genetic Mutations in RNA-Binding Proteins and Their Roles in ALS. Human Genetics. 2017 Jul; doi: 10.1007/s00439-017-1830-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-017-1830-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kawahara Yukio, Mieda-Sato Ai. TDP-43 Promotes microRNA Biogenesis as a Component of the Drosha and Dicer Complexes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(9):3347–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112427109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. RNA-Binding Proteins TIA-1 and TIAR Link the Phosphorylation of eIF-2 Alpha to the Assembly of Mammalian Stress Granules. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1999;147(7):1431–42. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Hong Joo, Kim Nam Chul, Wang Yong-Dong, Scarborough Emily A, Moore Jennifer, Diaz Zamia, MacLea Kyle S, et al. Mutations in Prion-like Domains in hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 Cause Multisystem Proteinopathy and ALS. Nature. 2013;495(7442):467–73. doi: 10.1038/nature11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kino Tomoshige, Hurt Darrell E, Ichijo Takamasa, Nader Nancy, Chrousos George P. Noncoding RNA gas5 Is a Growth Arrest- and Starvation-Associated Repressor of the Glucocorticoid Receptor. Science Signaling. 2010;3(107):ra8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klann Eric, Dever Thomas E. Biochemical Mechanisms for Translational Regulation in Synaptic Plasticity. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2004;5(12):931–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koritzinsky Marianne, Rouschop Kasper MA, van den Beucken Twan, Magagnin Michaël G, Savelkouls Kim, Lambin Philippe, Wouters Bradly G. Phosphorylation of eIF2alpha Is Required for mRNA Translation Inhibition and Survival during Moderate Hypoxia. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2007;83(3):353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koval Erica D, Shaner Carey, Zhang Peter, du Maine Xavier, Fischer Kimberlee, Tay Jia, Nelson Chau B, Wu Gregory F, Miller Timothy M. Method for Widespread microRNA-155 Inhibition Prolongs Survival in ALS-Model Mice. Human Molecular Genetics. 2013;22(20):4127–35. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Akihide, Sugai Akihiro, Kato Taisuke, Ishihara Tomohiko, Shiga Atsushi, Toyoshima Yasuko, Koyama Misaki, et al. Increased Cytoplasmic TARDBP mRNA in Affected Spinal Motor Neurons in ALS Caused by Abnormal Autoregulation of TDP-43. Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44(12):5820–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer Brian C, Schuck Theresa, Wheeler Jeanna M, Robinson Linda C, Trojanowski John Q, Lee Virginia MY, Schellenberg Gerard D. Loss of Murine TDP-43 Disrupts Motor Function and Plays an Essential Role in Embryogenesis. Acta Neuropathologica. 2010;119(4):409–19. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. Neuronal RNA Granules: A Link between RNA Localization and Stimulation-Dependent Translation. Neuron. 2001;32(4):683–96. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung Johnny TY, Colognori David, Lee Jeannie T. Long Noncoding RNAs: Past, Present, and Future. Genetics. 2013;193(3):651–69. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.146704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski TJ, Jr, Bosco DA, Leclerc AL, Tamrazian E, Vanderburg CR, Russ C, Davis A, et al. Mutations in the FUS/TLS Gene on Chromosome 16 Cause Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Science. 2009;323(5918):1205–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1166066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne Clotilde, Cleveland Don W. Rethinking ALS: The FUS about TDP-43. Cell. 2009;136(6):1001–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagier-Tourenne Clotilde, Polymenidou Magdalini, Hutt Kasey R, Vu Anthony Q, Baughn Michael, Huelga Stephanie C, Clutario Kevin M, et al. Divergent Roles of ALS-Linked Proteins FUS/TLS and TDP-43 Intersect in Processing Long Pre-mRNAs. Nature Neuroscience. 2012;15(11):1488–97. doi: 10.1038/nn.3230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Liana F, Inada Maki, Green Richard E, Wengrod Jordan C, Brenner Steven E. Unproductive Splicing of SR Genes Associated with Highly Conserved and Ultraconserved DNA Elements. Nature. 2007;446(7138):926–29. doi: 10.1038/nature05676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Edward B, Lee Virginia M-Y, Trojanowski John Q. Gains or Losses: Molecular Mechanisms of TDP43-Mediated Neurodegeneration. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2011;13(1):38–50. doi: 10.1038/nrn3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Yoontae, Ahn Chiyoung, Han Jinju, Choi Hyounjeong, Kim Jaekwang, Yim Jeongbin, Lee Junho, et al. The Nuclear RNase III Drosha Initiates microRNA Processing. Nature. 2003;425(6956):415–19. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Yoontae, Kim Minju, Han Jinju, Yeom Kyu-Hyun, Lee Sanghyuk, Baek Sung Hee, Narry Kim V. MicroRNA Genes Are Transcribed by RNA Polymerase II. The EMBO Journal. 2004;23(20):4051–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis Benjamin P, Green Richard E, Brenner Steven E. Evidence for the Widespread Coupling of Alternative Splicing and Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay in Humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100(1):189–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136770100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Jonathan P, Chhabra Resham, Merran Jonathan D, Schaughency Paul M, Wheelan Sarah J, Corden Jeffry L, Wong Philip C. PTBP1 and PTBP2 Repress Nonconserved Cryptic Exons. Cell Reports. 2016;17(1):104–13. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Jonathan P, Pletnikova Olga, Troncoso Juan C, Wong Philip C. TDP-43 Repression of Nonconserved Cryptic Exons Is Compromised in ALS-FTD. Science. 2015;349(6248):650–55. doi: 10.1126/science.aab0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Shuo-Chien, Albuquerque Claudio P, Han Joo Seok, Lagier-Tourenne Clotilde, Tokunaga Seiya, Zhou Huilin, Cleveland Don W. ALS-Associated Mutations in TDP-43 Increase Its Stability and Promote TDP-43 Complexes with FUS/TLS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(30):13318–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008227107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Qin, Zheng Sika, Han Areum, Lin Chia-Ho, Stoilov Peter, Fu Xiang-Dong, Black Douglas L. The Splicing Regulator PTBP2 Controls a Program of Embryonic Splicing Required for Neuronal Maturation. eLife. 2014;3(January):e01201. doi: 10.7554/eLife.01201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xuefeng, Li Dan, Zhang Weimin, Guo Mingzhou, Zhan Qimin. Long Non-Coding RNA gadd7 Interacts with TDP-43 and Regulates Cdk6 mRNA Decay. The EMBO Journal. 2012;31(23):4415–27. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu-Yesucevitz Liqun, Bilgutay Aylin, Zhang Yong-Jie, Vanderweyde Tara, Vanderwyde Tara, Citro Allison, Mehta Tapan, et al. Tar DNA Binding Protein-43 (TDP-43) Associates with Stress Granules: Analysis of Cultured Cells and Pathological Brain Tissue. PloS One. 2010;5(10):e13250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Zhihua, Lee Jinwoo, Krummey Scott, Lu Wei, Cai Huaibin, Lenardo Michael J. The Kinase LRRK2 Is a Regulator of the Transcription Factor NFAT That Modulates the Severity of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nature Immunology. 2011;12(11):1063–70. doi: 10.1038/ni.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Yan, Ray Payal, Rao Elizabeth J, Shi Chen, Guo Weirui, Chen Xiaoping, Woodruff Elvin A, 3rd, Fushimi Kazuo, Wu Jane Y. A Drosophila Model for TDP-43 Proteinopathy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(7):3169–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913602107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Dahlberg JE. Substrate Selectivity of Exportin 5 and Dicer in the Biogenesis of microRNAs. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 2006;71:59–66. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazroui Rachid, Sukarieh Rami, Bordeleau Marie-Eve, Kaufman Randal J, Northcote Peter, Tanaka Junichi, Gallouzi Imed, Pelletier Jerry. Inhibition of Ribosome Recruitment Induces Stress Granule Formation Independently of Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2alpha Phosphorylation. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2006;17(10):4212–19. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald Karli K, Aulas Anaïs, Destroismaisons Laurie, Pickles Sarah, Beleac Evghenia, Camu William, Rouleau Guy A, Velde Christine Vande. TAR DNA-Binding Protein 43 (TDP-43) Regulates Stress Granule Dynamics via Differential Regulation of G3BP and TIA-1. Human Molecular Genetics. 2011;20(7):1400–1410. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medghalchi SM, Frischmeyer PA, Mendell JT, Kelly AG, Lawler AM, Dietz HC. Rent1, a Trans-Effector of Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay, Is Essential for Mammalian Embryonic Viability. Human Molecular Genetics. 2001;10(2):99–105. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr E, Fehr S, Richter D. Axonal Transport of Neuropeptide Encoding mRNAs within the Hypothalamo-Hypophyseal Tract of Rats. The EMBO Journal. 1991;10(9):2419–24. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07781.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisse Katie, Volkening Kathryn, Leystra-Lantz Cheryl, Welch Ian, Hill Tracy, Strong Michael J. Divergent Patterns of Cytosolic TDP-43 and Neuronal Progranulin Expression Following Axotomy: Implications for TDP-43 in the Physiological Response to Neuronal Injury. Brain Research. 2009;1249(January):202–11. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morlando Mariangela, Modigliani Stefano Dini, Torrelli Giulia, Rosa Alessandro, Di Carlo Valerio, Caffarelli Elisa, Bozzoni Irene. The EMBO Journal. 24. Vol. 31. EMBO Press; 2012. FUS Stimulates microRNA Biogenesis by Facilitating Co-transcriptional Drosha Recruitment; pp. 4502–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murchison Elizabeth P, Hannon Gregory J. miRNAs on the Move: miRNA Biogenesis and the RNAi Machinery. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2004;16(3):223–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Melissa E, DeJesus-Hernandez Mariely, Rutherford Nicola J, Baker Matt, Duara Ranjan, Graff-Radford Neill R, Wszolek Zbigniew K, et al. Clinical and Neuropathologic Heterogeneity of c9FTD/ALS Associated with Hexanucleotide Repeat Expansion in C9ORF72. Acta Neuropathologica. 2011;122(6):673–90. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0907-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutihac R, Alegre-Abarrategui J, Gordon D, Farrimond L, Yamasaki-Mann M, Talbot K, Wade-Martins R. TARDBP Pathogenic Mutations Increase Cytoplasmic Translocation of TDP-43 and Cause Reduction of Endoplasmic Reticulum Ca2+ Signaling in Motor Neurons. Neurobiology of Disease. 2015;75(March):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann Manuela. Molecular Neuropathology of TDP-43 Proteinopathies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2009;10(1):232–46. doi: 10.3390/ijms10010232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Julie Z, Grate Leslie, Donohue John Paul, Preston Christine, Nobida Naomi, O’Brien Georgeann, Shiue Lily, Clark Tyson A, Blume John E, Ares Manuel., Jr Ultraconserved Elements Are Associated with Homeostatic Control of Splicing Regulators by Alternative Splicing and Nonsense-Mediated Decay. Genes & Development. 2007;21(6):708–18. doi: 10.1101/gad.1525507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto Yoshinori, Nakagawa Shinichi, Hirose Tetsuro, Okano Hirotaka James, Takao Masaki, Shibata Shinsuke, Suyama Satoshi, et al. The Long Non-Coding RNA Nuclear-Enriched Abundant Transcript 1_2 Induces Paraspeckle Formation in the Motor Neuron during the Early Phase of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Molecular Brain. 2013;6(July):31. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paez-Colasante Ximena, Figueroa-Romero Claudia, Sakowski Stacey A, Goutman Stephen A, Feldman Eva L. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Mechanisms and Therapeutics in the Epigenomic Era. Nature Reviews. Neurology. 2015;11(5):266–79. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Qun, Shai Ofer, Lee Leo J, Frey Brendan J, Blencowe Benjamin J. Deep Surveying of Alternative Splicing Complexity in the Human Transcriptome by High-Throughput Sequencing. Nature Genetics. 2008;40(12):1413–15. doi: 10.1038/ng.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen Michelle T, Veloso Artur, Prasad Jayendra, Bedi Karan, Ljungman Emily A, Tsan Ya-Chun, Chang Ching-Wei, et al. Coordinated Regulation of Synthesis and Stability of RNA during the Acute TNF-Induced Proinflammatory Response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(6):2240–45. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219192110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesiridis G Scott, Lee Virginia M-Y, Trojanowski John Q. Mutations in TDP-43 Link Glycine-Rich Domain Functions to Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Human Molecular Genetics. 2009;18(R2):R156–62. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polymenidou Magdalini, Lagier-Tourenne Clotilde, Hutt Kasey R, Huelga Stephanie C, Moran Jacqueline, Liang Tiffany Y, Ling Shuo-Chien, et al. Long Pre-mRNA Depletion and RNA Missplicing Contribute to Neuronal Vulnerability from Loss of TDP-43. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14(4):459–68. doi: 10.1038/nn.2779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp Maximilian Wei-Lin, Maquat Lynne E. Organizing Principles of Mammalian Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay. Annual Review of Genetics. 2013;47:139–65. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Takashi, Shiohama Aiko, Minoshima Shinsei, Shimizu Nobuyoshi. Identification of Eight Members of the Argonaute Family in the Human Genome☆. Genomics. 2003;82(3):323–30. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid Bettina, Hruscha Alexander, Hogl Sebastian, Banzhaf-Strathmann Julia, Strecker Katrin, van der Zee Julie, Teucke Mathias, et al. Loss of ALS-Associated TDP-43 in Zebrafish Causes Muscle Degeneration, Vascular Dysfunction, and Reduced Motor Neuron Axon Outgrowth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110(13):4986–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218311110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seilhean Danielle, Cazeneuve Cécile, Thuriès Valérie, Russaouen Odile, Millecamps Stéphanie, Salachas François, Meininger Vincent, LeGuern Eric, Duyckaerts Charles. Acta Neuropathologica. 4. Vol. 118. Springer-Verlag; 2009. Accumulation of TDP-43 and α-Actin in an Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patient with the K17I ANG Mutation; pp. 561–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sephton Chantelle F, Cenik Can, Kucukural Alper, Dammer Eric B, Cenik Basar, Han Yuhong, Dewey Colleen M, et al. Identification of Neuronal RNA Targets of TDP-43-Containing Ribonucleoprotein Complexes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286(2):1204–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.190884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sephton Chantelle F, Good Shannon K, Atkin Stan, Dewey Colleen M, Mayer Paul, 3rd, Herz Joachim, Yu Gang. TDP-43 Is a Developmentally Regulated Protein Essential for Early Embryonic Development. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(9):6826–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakola Felitsiya, Suri Parul, Ruggiu Matteo. Splicing Regulation of Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines: At the Interface of the Neuroendocrine and Immune Systems. Biomolecules. 2015;5(3):2073–2100. doi: 10.3390/biom5032073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Kevin Y, Mori Eiichiro, Nizami Zehra F, Lin Yi, Kato Masato, Xiang Siheng, Wu Leeju C, et al. Toxic PRn Poly-Dipeptides Encoded by the C9orf72 Repeat Expansion Block Nuclear Import and Export. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114(7):E1111–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620293114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Bradley N, Vance Caroline, Scotter Emma L, Troakes Claire, Wong Chun Hao, Topp Simon, Maekawa Satomi, et al. Novel Mutations Support a Role for Profilin 1 in the Pathogenesis of ALS. Neurobiology of Aging. 2015;36(3):1602.e17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs Keith A, Bushell Martin, Willis Anne E. Translational Regulation of Gene Expression during Conditions of Cell Stress. Molecular Cell. 2010;40(2):228–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suckale Jakob, Wendling Olivia, Masjkur Jimmy, Jäger Melanie, Münster Carla, Anastassiadis Konstantinos, Francis Stewart A, Solimena Michele. PTBP1 Is Required for Embryonic Development before Gastrulation. PloS One. 2011;6(2):e16992. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Xiaolei, Perlick Haley A, Dietz Harry C, Maquat Lynne E. A Mutated Human Homologue to Yeast Upf1 Protein Has a Dominant-Negative Effect on the Decay of Nonsensecontaining mRNAs in Mammalian Cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95(17):10009–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sureau A, Gattoni R, Dooghe Y, Stévenin J, Soret J. SC35 Autoregulates Its Expression by Promoting Splicing Events That Destabilize Its mRNAs. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20(7):1785–96. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup Vivek, Audet Jean-Nicolas, Phaneuf Daniel, Kriz Jasna, Julien Jean-Pierre. Abnormal Regenerative Responses and Impaired Axonal Outgrowth after Nerve Crush in TDP-43 Transgenic Mouse Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32(50):18186–95. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2267-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swarup Vivek, Phaneuf Daniel, Bareil Christine, Robertson Janice, Rouleau Guy A, Kriz Jasna, Julien Jean-Pierre. Pathological Hallmarks of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration in Transgenic Mice Produced with TDP-43 Genomic Fragments. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2011;134(Pt 9):2610–26. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Qiumin, Yalamanchili Hari Krishna, Park Jeehye, De Maio Antonia, Lu Hsiang-Chih, Wan Ying-Wooi, White Joshua J, et al. Extensive Cryptic Splicing upon Loss of RBM17 and TDP43 in Neurodegeneration Models. Human Molecular Genetics. 2016;25(23):5083–93. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddw337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatom Jason B, Wang David B, Dayton Robert D, Skalli Omar, Hutton Michael L, Dickson Dennis W, Klein Ronald L. Mimicking Aspects of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration and Lou Gehrig’s Disease in Rats via TDP-43 Overexpression. Molecular Therapy: The Journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2009;17(4):607–13. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tollervey James R, Curk Tomaž, Rogelj Boris, Briese Michael, Cereda Matteo, Kayikci Melis, König Julian, et al. Characterizing the RNA Targets and Position-Dependent Splicing Regulation by TDP-43. Nature Neuroscience. 2011;14(4):452–58. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida Azusa, Sasaguri Hiroki, Kimura Nobuyuki, Tajiri Mio, Ohkubo Takuya, Ono Fumiko, Sakaue Fumika, et al. Non-Human Primate Model of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis with Cytoplasmic Mislocalization of TDP-43. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2012;135(Pt 3):833–46. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance Caroline, Rogelj Boris, Hortobágyi Tibor, De Vos Kurt J, Nishimura Agnes Lumi, Sreedharan Jemeen, Hu Xun, et al. Mutations in FUS, an RNA Processing Protein, Cause Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Type 6. Science. 2009;323(5918):1208–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1165942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Mossevelde Sara, van der Zee Julie, Gijselinck Ilse, Engelborghs Sebastiaan, Sieben Anne, Van Langenhove Tim, De Bleecker Jan, et al. Clinical Features of TBK1 Carriers Compared with C9orf72, GRN and Non-Mutation Carriers in a Belgian Cohort. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 2016;139(Pt 2):452–67. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt Aaron, Herholz David, Fiesel Fabienne C, Kaur Kavita, Müller Daniel, Karsten Peter, Weber Stephanie S, Kahle Philipp J, Marquardt Till, Schulz Jörg B. TDP-43-Mediated Neuron Loss in Vivo Requires RNA-Binding Activity. PloS One. 2010;5(8):e12247. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I-Fan, Wu Lien-Szn, Chang Hsiang-Yu, James Shen C-K. TDP-43, the Signature Protein of FTLD-U, Is a Neuronal Activity-Responsive Factor. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2008;105(3):797–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Xiangting, Arai Shigeki, Song Xiaoyuan, Reichart Donna, Du Kun, Pascual Gabriel, Tempst Paul, Rosenfeld Michael G, Glass Christopher K, Kurokawa Riki. Induced ncRNAs Allosterically Modify RNA-Binding Proteins in Cis to Inhibit Transcription. Nature. 2008;454(7200):126–30. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegorzewska Iga, Baloh Robert H. TDP-43-Based Animal Models of Neurodegeneration: New Insights into ALS Pathology and Pathophysiology. Neuro-Degenerative Diseases. 2011;8(4):262–74. doi: 10.1159/000321547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weg-Remers S, Ponta H, Herrlich P, König H. Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing by the ERK MAP-Kinase Pathway. The EMBO Journal. 2001;20(15):4194–4203. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.15.4194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis Dianna, Li Ka Wan, Zheng Jun-Qi, Chang Jay H, Smit August B, Smit August, Kelly Theresa, et al. Differential Transport and Local Translation of Cytoskeletal, Injury-Response, and Neurodegeneration Protein mRNAs in Axons. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2005;25(4):778–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4235-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wils Hans, Kleinberger Gernot, Janssens Jonathan, Pereson Sandra, Joris Geert, Cuijt Ivy, Smits Veerle, Groote Chantal Ceuterick-de, Van Broeckhoven Christine, Kumar-Singh Samir. TDP-43 Transgenic Mice Develop Spastic Paralysis and Neuronal Inclusions Characteristic of ALS and Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(8):3858–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912417107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woerner Andreas C, Frottin Frédéric, Hornburg Daniel, Feng Li R, Meissner Felix, Patra Maria, Tatzelt Jörg, et al. Cytoplasmic Protein Aggregates Interfere with Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of Protein and RNA. Science. 2016;351(6269):173–76. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollerton Matthew C, Gooding Clare, Wagner Eric J, Garcia-Blanco Mariano A, Smith Christopher WJ. Autoregulation of Polypyrimidine Tract Binding Protein by Alternative Splicing Leading to Nonsense-Mediated Decay. Molecular Cell. 2004;13(1):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Lien-Szu, Cheng Wei-Cheng, James Shen C-K. Targeted Depletion of TDP-43 Expression in the Spinal Cord Motor Neurons Leads to the Development of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis-like Phenotypes in Mice. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(33):27335–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.359000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Ya-Fei, Gendron Tania F, Zhang Yong-Jie, Lin Wen-Lang, D’Alton Simon, Sheng Hong, Casey Monica Castanedes, et al. Wild-Type Human TDP-43 Expression Causes TDP-43 Phosphorylation, Mitochondrial Aggregation, Motor Deficits, and Early Mortality in Transgenic Mice. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30(32):10851–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1630-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo Gene, Holste Dirk, Kreiman Gabriel, Burge Christopher B. Variation in Alternative Splicing across Human Tissues. Genome Biology. 2004;5(10):R74. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Ke, Donnelly Christopher J, Haeusler Aaron R, Grima Jonathan C, Machamer James B, Steinwald Peter, Daley Elizabeth L, et al. The C9orf72 Repeat Expansion Disrupts Nucleocytoplasmic Transport. Nature. 2015;525(7567):56–61. doi: 10.1038/nature14973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Zhijun, Almeida Sandra, Lu Yubing, Nishimura Agnes L, Peng Lingtao, Sun Danqiong, Wu Bei, et al. Downregulation of microRNA-9 in iPSC-Derived Neurons of FTD/ALS Patients with TDP-43 Mutations. PloS One. 2013;8(10):e76055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Yueqin, Liu Songyan, Liu Guodong, Oztürk Arzu, Hicks Geoffrey G. ALS-Associated FUS Mutations Result in Compromised FUS Alternative Splicing and Autoregulation. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9(10):e1003895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]