Abstract

Many signaling proteins consist of globular domains connected by flexible linkers that allow for substantial domain motion. Because these domains often serve as complementary functional modules, the possibility of functionally important domain motions arises. To explore this possibility, we require knowledge of the ensemble of protein conformations sampled by interdomain motion.

Measurements of NMR residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) of backbone NH bonds offer a per-residue characterization of interdomain dynamics, as the couplings are sensitive to domain orientation. A challenge in reaching this potential is the need to interpret the RDCs as averages over dynamic ensembles of domain conformations.

Here, we address this challenge by introducing an efficient protocol for generating conformational ensembles appropriate for flexible, multi-domain proteins. The protocol uses map-restrained self-guided Langevin dynamics simulations to promote collective, interdomain motion while restraining the internal domain motion to near rigidity. Critically, the simulations retain an all-atom description for facile inclusion of site-specific NMR RDC restraints. The result is the rapid generation of conformational ensembles consistent with the RDC data.

We illustrate this protocol on human Pin1, a two-domain peptidyl-prolyl isomerase relevant for cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. The results include the ensemble of domain orientations sampled by Pin1, as well as those of a dysfunctional variant, I28A-Pin1. The differences between the ensembles corroborate our previous spin relaxation results that showed weakened interdomain contact in the I28A variant relative to wild type. Our protocol extends our abilities to explore the functional significance of protein domain motions.

Keywords: protein dynamics, NMR, ensemble description, domain motion, self-guided Langevin dynamics, residual dipolar couplings, multi-conformational fitting

Graphical abstract

INTRODUCTION

Many signaling proteins have a modular architecture, consisting of globular domains that carry out distinct and inter-related functions 1–3. Often the linkers enable substantial rotational motion between adjacent domains. Exploring the functional role of these motions in the signaling mechanism calls for both experimental and computational approaches.

An effective experimental approach is the measurement of NMR residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) between pairs of spin ½ nuclei 4. Dipolar couplings depend on the average orientation between the dipolar interaction vector (the inter-nuclear vector), and the external static magnetic field, B0. In standard solution-state samples, the internuclear vectors sample all orientations with equal likelihood as a result of isotropic molecular tumbling; consequently, the dipolar couplings average to zero. However, the dipolar couplings can be re-introduced by weak alignment of the protein molecules using established alignment media 5, 6. In this work, we focus on RDCs of backbone amide 1H-15N bonds, which report on the average orientation of the 1H-15N bond vectors with respect to B0. Backbone HN RDC measurements are particularly popular due to the availability of robust 2-D heteronuclear correlation pulse schemes for extracting HN RDC values, and the ubiquity of uniformly 15N-enriched (U-15N) proteins samples in protein NMR studies 7, 8. Of note, (U-15N) protein samples offer several advantages that explain their ubiquity: (i) 2-D 1H-15N correlation spectra can account for all residues except Proline, as their 2-D cross-peaks correspond to amide 1H-15N bonds; (ii) 2-D 1H-15N spectra of backbone amides generally show favorable chemical shift dispersion; and (iii) U-15N enrichment is relatively inexpensive.

To extract conformational information from the RDCs, one re-expresses the orientation angle between the RDC internuclear vectors and B0 in terms of two sets of angles. The first set describes the average orientation of the HN bond vector relative to a molecule-fixed set of axes that corresponds to the protein alignment tensor. Then, the second set of angles describes the orientation of the tensor axes relative to B0. The alignment tensor describes the orientational preferences of the protein, as dictated by the chosen alignment medium and the protein’s spatial distribution of mass and charge. Being a 2nd rank spherical tensor, the alignment tensor has five independent components. Provided one measures at least five independent RDCs from the same rigid domain or whole molecule (e.g. RDCs from five non-collinear HN bonds), the tensor components can be determined using singular value decomposition (SVD) 9. The set of backbone HN RDCs usually suffices for this purpose. Importantly, the alignment tensor, once determined, acts as a common reference frame for comparing the orientations of widely separated NH bonds, such as those in distinct globular domains. This feature endows RDCs with long-range conformational information that is lacking in more traditional NMR structural parameters, such as NOEs or through-bond scalar couplings 4.

The default analysis of 1H 15N RDC data assumes a single alignment tensor corresponding to a single, dominant backbone structure 9. This assumption is reasonable for single domain proteins. But it is questionable for modular proteins, which often consist of globular domains are connected by flexible linkers. Relative motion between the domains can give rise to multiplicity of domain orientations with an attendant multiplicity of alignment tensors. If the domain motions occur on time scales short compared to the RDC measurements (i.e. < 1 ms) 10, then the measured RDC values are not reflective of a single interdomain configuration, but instead, represent averages over the ensemble of domain orientations sampled by the domain motions. In this case, the original SVD method is not appropriate for deriving the alignment tensor in that it attempts to match the experimental RDCs to a single conformation. In contrast, model-based simulations can estimate the alignment tensor using individual conformations, such as in the PALES approach (“Prediction of ALignmEnt from Structure) 11, 12, where the tensor is estimated via a Monte Carlo search of molecules in the vicinity of an infinite two dimensional plate.

In principle, the experimental RDCs can provide insight into the domain motions, if they can be quantitatively related to distributions of domain orientations contained within a suitable ensemble of protein conformations. Interpreting RDCs and other NMR parameters in terms of conformational ensembles have relied on computational approaches, such as explicit solvent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, to generate structural ensembles 13–16. A persistent challenge facing these simulations is achieving sufficiently broad conformational sampling on the time scales of protein dynamics characterized by experiment. Collective motions, such as domain re-orientation studied here, occur less frequently and thus require longer simulation trajectories. Millisecond simulation trajectories are now possible using MD-dedicated supercomputers 17. Nevertheless, such trajectories are not yet routine, and may be impractical for large-scale studies (e.g. multiple protein constructs and series of homologs). Enhancing the efficiency of conformational sampling thus remains a practical and important priority.

Two techniques for enhancing sampling efficiency are coarse-grained simulations, and restraint potentials incorporating experimental results. Coarse-graining reduces the degrees of freedom during the simulation by judicious removal of some level of atomic detail. Examples include methods that treat the protein as a set of hydrodynamic spheres in order to focus on domain reorientation 18–20. Experimental restraint potentials bias the simulation to regions of configuration space pertinent to the experimental observations (e.g. nuclear Overhauser enhancements, scalar couplings, RDCs, chemical shifts) 21. Yet, there is potential conflict between these two routes: namely, decreased atomic resolution from coarse-graining may exclude the atomic detail necessary for including site-specific NMR data.

The above considerations motivate the present work: an efficient protocol for generating conformational ensembles to interpret NMR observables reporting on whole domain motion. Our protocol is based on map-restrained self-guided Langevin dynamics (Map-SGLD) 22, 23. Map restraints enable trajectories emphasizing relative domain motion, while simultaneously allowing for facile inclusion of NMR restraints. The combination of Map-SGLD simulations with NMR restraints (MapSGLD-NMR, hereafter) generates a broad ensemble of domain orientations suitable for interpreting dynamic RDCs. To inter-relate the RDCs and the resulting ensemble, we use a genetic algorithm (GA) based multi-conformation fitting procedure 24. The GA procedure fits the observed RDCs to population-weighted averages calculated over the distribution of domain orientations contained in the Map-SGLD-NMR ensemble. The end result is a tractable set (~10) of population-weighted conformations that collectively capture the inter-domain flexibility sensed by the dynamically averaged RDCs from experiment. This GA procedure is similar to previous multi-structure approaches for RNA 25 and protein 26 ensembles.

We demonstrate the MapSGLD-NMR protocol by applying it to 1H–15N RDC measurements of Pin1, a peptidyl-prolyl isomerase recruited by numerous signaling pathways regulating mitosis and neurodegenerative disease 27–30. Pin1 consists of two flexibly linked domains: an N-terminal WW domain (residues 1-39) binds protein substrates, and a larger C-terminal peptidyl-prolyl-isomerase (PPIase) domain (residues 52-163). Both domains target phospho-Ser/Thr-Pro (pS/T-P) motifs. The WW domain serves as a binding module, while the larger PPIase accelerates the cis-trans isomerization of imide pS/T-P linkage. Previous x-ray and NMR studies indicated significant interdomain motion 31–38; yet, an atomic-level description of the ensemble of domain configurations remains elusive. Our MapSGLD-NMR analysis of Pin1 gives a first glimpse of this ensemble.

The remainder of our report proceeds as follows. The results section highlights the central features of the Map-SGLD-NMR and GA/Multi-conformational fitting protocols, with finer technical details deferred to the Materials and Methods section. We then describe the MapSGLD-NMR ensemble for wild-type (WT) Pin1, focusing on simulation parameters governing the RDC restraints and overall sampling efficiency. We also explore the validity of the MapSGLD-NMR ensemble through studies of a Pin1 variant, I28A, which carries a single Isoleucine to Alanine substitution in the WW domain β2β3-turn. The I28A-Pin1 ensemble indicates enhanced interdomain mobility compared to WT-Pin1 – a result consistent with our previous 15N/13CMETHYL spin relaxation and chemical shift analyses of I28A-Pin1 36, 39. We conclude by discussing the potential of MapSGLD-NMR for the general study of interdomain motion. Notably, while this work illustrates MapSGLD-NMR using RDC data, it could in principle be used for any NMR observables sensitive to interdomain flexibility (e.g. chemical shifts, spin relaxation rates, paramagnetic relaxation enhancements).

RESULTS

Backbone HN RDCs for Pin1

We collected two independent 1H 15N RDC data sets for wild-type (WT) Pin1, corresponding to two alignment media: (i) a 4% (w/vol)/r=0.87% octanol) C8E5/octanol mixture 40, hereafter referred to as C8E5; (ii) and 10– 20 mg/mL Pf1 phage media 41. Weak alignment results from steric collisions in the C8E5 mixture, and electrostatic interactions in the case of Pf1 phage. 1H 15N RDCs were measured in triplicate (i.e. three spectra recorded and dipolar splittings measured) using standard IPAP 2D 1H 15N pulse schemes 8; data acquisition parameters are in the Materials and Methods subsection (vide infra).

We pruned the raw RDCs to those most representative of domain re-orientational motion. This meant excluding HN bonds showing signs of large amplitude, sub-nanosecond local bond librations (e.g. low order parameter SHN per Eq 2), excessive exchange broadening, or resonance overlap. The pruned datasets (Fig. S1) consisted of 83 RDCs from 4% C8E5 media (11 from the WW domain, 72 from the PPIase domain), and 93 RDCs from 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage (17 from the WW domain, 76 from the PPIase domain). We used the standard deviation of the triplicate RDC values to estimate the uncertainties in the RDCs. The average uncertainties were 1.52 Hz for 4% C8E5, and 1.04 Hz for 10 mg/ml Pf1 page.

To assess the independence of the 4% C8E5 and Pf1 phage RDC data sets, we compared the corresponding alignment tensors, using PALES (“Prediction of ALignmEnt from Structure) 11, 12 (Table S1, Supporting information). In particular, we evaluated the normalized dot product between vectors consisting of the five tensor components (AZZ, AXX-AYY, AXY, AYZ, AXZ) from the respective media 10, 42, 43. Orthogonal vectors (zero dot product, 90 degrees between vectors) correspond to total independence. The dot products (Table S2 in the Supporting information) indicate sufficient independence (vector angles differing by 55 to 79 degrees) between the 4% C8E5 and Pf1 phage RDC datasets. These values are consistent with the fact that alignment tensors from C8E5 and Pf1 reflect different molecular properties (steric effect and charge distribution), although the conformations might be correlated.

Map-restrained Self-Guided Langevin Dynamics

To generate Pin1 conformations relevant to backbone 1H-15N RDCs, we pursued an MD strategy that emphasized relative domain motion. Specifically, we kept the PPIase domain fixed in space by applying strong Cartesian harmonic restraints (force constants of 1.0 kcal/mol·Å2); indeed the PPIase RMSD values were < 0.5 Å over the simulations (Fig. S2, Supporting Information). We then moved the WW domain relative to the fixed PPIase domain using map-restrained 23 self-guided Langevin dynamics (Map-SGLD) 22. The map restraints were of central importance, as they enabled motion of the WW domain as a nearly rigid body, while keeping full atomic detail. Further details concerning the setup of the MapSGLD simulations are in the Materials and Methods.

RDC restraints

This preservation of full atomic detail presented an opportunity to extend the original Map-SGLD method by including residue-specific restraint potentials based on experimental NMR RDC data 21

| (1) |

Eq 1 is a sum of quadratic restraint potentials over the 1H–15N RDCs for both domains and in both the 4% C8E5 and phage alignment media. The overall magnitude of ERDC, κRDC, was set to a low value (κRDC = 0.1 kcal/Hz2) to avoid inhibition of the conformational search. The RDCj, CALC values were calculated from the atomic coordinates of the jth NH bond using the form 21

| (2) |

Eq 2 assumes that the internal motions of the HN bonds are cylindrically symmetric about a well-defined average position in the molecule-fixed frame 21. The pre-factor contains the 1H–15N dipolar coupling constant . The cosine terms (cosΦX, j, cosΦY, j, and cosΦZ, j) are the average X,Y, and Z positions of the unit vector lying along the jth HN bond in an arbitrary molecule-fixed reference frame. The AXX, AYY, AZZ, AXY, AYZ, and AXZ terms are Cartesian alignment tensor components in the same molecule-fixed frame. The Lipari-Szabo scaling factor SHN, (0 < SHN < 1) 44 accounts for the amplitude of presumed symmetric motion of the HN bond about its average position (the aforementioned cosines). The pruning of raw RDCs serves to select for those HNs for whom the SHN are close to unity (low amplitude local motion). Of note, the tensor components are treated as dynamical coordinates in these simulations; they are updated each 1-femtosecond time step along with the usual atomic coordinates 21. Hence, the alignment tensor is determined by minimization of Eq 1, and is independent of an a priori physical model for the alignment mechanism.

MapSGLD-NMR Simulation Protocol

The initial Pin1 coordinates for the MapSGLD-NMR simulations came from the PDB deposition 1NMV, the NMR solution structure of apo Pin1 33. We chose 1NMV, as it was the only Pin1 PDB deposition with an intact linker, thereby preserving the translational information between the domains. To promote broader conformational searching, we ran three parallel simulations starting from structures 1,2, and 4 in the 1NMV PDB deposition, referred to as 1NMV-1, 1NMV-2, and 1NMV-4 hereafter. This trio of initial structures spanned the range of interdomain orientations defined by all ten structures within 1NMV.

The three initial structures were prepared identically for the MapSGLD-NMR simulations. Preparation included a first energy minimization (500 steps) with NMR ERDC restraint potentials (Eq 1) turned off. The resulting energy reductions were typically to −3000 to −5000 kcal/mol. Next, the structures underwent a second energy minimization (100 steps), with the ERDC potentials turned on in order to define the initial alignment tensor components AXX, AYY, AZZ, AXY, AXZ, and AYZ for each conformer and alignment medium. This involved varying the tensor components while holding the protein domain coordinates (direction cosines) fixed 21. The final preparatory step defined the initial map restraints for the WW domains of the starting structures, per the methods outlined by Wu et al 22.

The three minimized structures (1NMV-1, 1NMV-2, and 1NMV-4) kicked off three 30ns MapSGLD-NMR trajectories, each using the same set of parameters listed in Table 1. Each trajectory used a 1 femtosecond time step to evaluate all forces needed to advance atomic positions, velocities, and alignment tensor components AXX, AYY, AZZ, AXY, AXZ, and AYZ for each alignment medium. Notably, the atomic “positions” included both the protein coordinates and the map coordinates xi, yj, and zk. The latter evolved according to the over-damped Langevin motion of its proxy rigid body 22. The interval for local the time-averaging needed to calculate the guiding force was tL = 0.5 picoseconds (500 steps of δt = 1 femtoseconds).

Table 1.

Parameters for MapSGLD-NMR Simulations

| Parameter | Significance | Value |

|---|---|---|

| kRDC | ERDC Constant | 0.1 kcal/mol-Hz 2 |

| CMAP | EMAP Constant | 0.1 kcal/amu, |

| RMAP | Map Resolution | 5 Å |

| γMAP | map friction coefficient | 0.1 ps−1 |

| γ | atomic friction coefficient | 5 ps−1 |

| δt | time-step | 1 fs |

| tL | window for local time-averaging | 0.5 ps (500 time steps) |

| λ | guiding factor | 1.0 |

| TSG | guiding force enhancement | 400K |

Each starting structure spawned a 30 nanoseconds MapSGLD-NMR trajectory, with snapshots (structural coordinates) written every 1000 steps (1 picosecond). Each 30 nanoseconds trajectory took approximately 6 days on 48 processors, using the Gyges processors at Rutgers University. Pooling the three 30 nanoseconds trajectories generated the raw MapSGLD-NMR ensemble of 90,000 conformations (snapshots) used for the subsequent analysis.

To monitor the trajectory stabilities and verify the intended rigid body motion, we followed domain-specific RMSDs and standard energy values. The energies stabilized quickly, (within ~ 250 picoseconds), and remained stable throughout the rest of simulations (Fig. S3, Supporting Information).

We also followed the trajectories progress by following the correlation between the experimental RDCs versus the predicted RDCs from PALES 12. The predicted RDCs came from the standard “ –bestFit ” mode of PALES, which uses the singular value decomposition (SVD) described by Losonsci et al 9, to best fit the experimental RDCs. We used the PALES calculated Q factor 4, 45

| (3) |

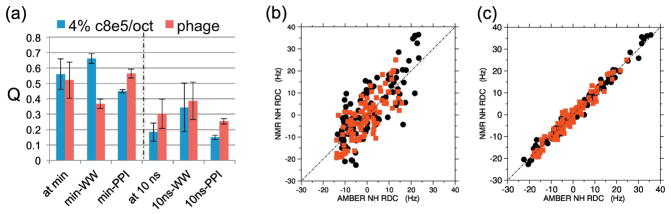

to define the agreement between the calculated versus experimental RDC values (lower Q indicates better agreement). Figure 2 compares the Q factors and linear correlation plots obtained at the conclusion of energy minimization to those obtained after 10 nanoseconds of the production-run MapSGLD-NMR simulations. Both the Q factors and linear correlation plots show clear improved consistency between the experimental RDCs and the Pin1 conformations sampled by the trajectories, for both alignment media.

Fig. 2.

(A) RDC Q factors (blue and maroon bars) for assessing agreement between 1H-15N RDCs predicted from AMBER generated conformations with those from the NMR experiments. The Q factors are averages are over the three parallel production-run simulations started from structures 1NMV-1, 1NMV-2, and 1NMV-4 from the solution structure deposition PDB 1NMV 33; the error bars are the corresponding standard deviations of Q factors. The predicted RDCs came from singular value decomposition (SVD) fitting to the experimental RDCs 9, using the “ –bestFit ” option in PALES 12. Pairs of blue and maroon bars indicate Q factors for 4% C8E5/octanol media (blue), and 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage (maroon), respectively. Q factors for full-length Pin1, the WW domain, and the PPIase domain are indicated. The dashed-dotted line distinguishes two sets of Q factors. Left of the line are Q-factors just after energy minimization and before the production-run simulations. Right of the line are the analogous Q factors after 10 ns of the three production-run AMBER simulations, using the MapSGLD-NMR protocol. The reduction in Q factors after 10 ns (1/3 of the total simulation time per starting structure) is apparent. (B, C) Representative correlation plots between the 1H-15N RDCs predicted by AMBER conformations (x-axes) versus experiment (y-axes). Black circles are RDCs in and 4% C8E5; red squares are RDCs in 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage. In (B), the standard linear regression coefficient is r = 0.88 ± 0.07 for 4% C8E5 (black circles) and r = 0.87 ± 0.03 for 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage (red squares); (C) after 10 nanoseconds of production-run simulations, the standard linear regression coefficient is r = 0.991 ± 0.002 for 4% C8E5 (black circles) and r = 0.984 ± 0.008 for 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage (red squares).

Single conformer analysis of RDCs

Of main interest was the ability of the MapSGLD-NMR ensemble to reproduce the experimental 1H-15N RDCs, and thereby investigate the extent to which those RDCs demanded a dynamic interpretation. To set a baseline, we first did the standard single conformer analysis, testing the individual abilities of each of 90,000 Pin1 conformations in the MapSGLD-NMR ensemble to reproduce all of the experimental RDCs. For each conformation, we used PALES 12 in the “ –stPales ” mode, to calculate the alignment tensor, 1H-15N RDCs, and Q factor, per Eq 3. Of note, in contrast to the “ –bestFit” mode, the “ –stPales ” mode determines the alignment tensor based on the structural coordinates and a physical model of its interactions with the alignment media; the experimental RDCs are not used for the prediction.

To explore the effect of the RDC restraints on conformational ensemble, we varied their number and looked for changes in the Q factors. Switching off the RDC restraints one by one raised the minimum Q, indicating the influence of experimental RDCs on the MapSGLD-NMR trajectories. We also investigated the influence of media-specific RDCs by generating three additional 90 nanosecond MapSGLD-NMR ensembles (again 90,000 conformations each): (a) an ensemble restrained exclusively by 4% C8E5 RDCs; (b) an ensemble restrained by Pf1 phage RDCs exclusively; (c), and an ensemble lacking all RDC restraints. Table 2 summarizes the results, listing the minimum, maximum, and average values for the single conformer Q factors. Generally, these Q factors were large compared to the Q factors reported in the literature to be demonstrative of high-quality fits among single domain globular proteins (e.g. Q ~ 0.2 to 0.3 4, 46). The high single conformer Q factors suggested that the underlying premise – that a single rigid structure should be able to account for the NH RDCs – was unsatisfactory for Pin1. Comparisons of Q factors between media-exclusive ensembles are discussed further below.

Table 2.

Distribution of Single Conformer Q Factors from Different MapSGLD-NMR Simulations

| RDC restraints Enforced | Min Q | Max Q | Average Q |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both Media RDCs (83+93) | 0.236* | 1.054* | 0.858* |

| Exclusive 4% C8E5 RDCs (83) | 0.257 | 1.039 | 0.774 |

| Exclusive phage RDCs (93) | 0.560 | 1.054 | 0.915 |

| No RDC restraints | 0.527 | 1.053 | 0.930 |

Q factors calculated using on the 4% C8E5 experimental RDCs

Multi-conformer analysis of RDCs

Proteins sampling a distribution of conformations on time scales up to ~ ms yield dynamically-averaged RDCs 10. To account for this averaging, we used a multi-conformational fitting procedure in the calculated RDCs 47. The procedure calculates the RDC for the jth NH bond vector as a population-weighted average over “M” basis structures, per Eq 4,

| (4) |

RDCj,k denotes the RDC for the jth bond vector, specific to the kth basis structure with fractional population Pk. Notably, Eq 4 allows each kth basis structure to have its own distinct pair of alignment tensors. To calculate 〈RDCj〉, we applied PALES to each of the “M” basis structures to calculate alignment tensor components and RDCs, and then took the Pk–weighted sum. Critically, in these PALES calculations, the aforementioned “ –bestFit ” (SVD) approach must be avoided, as it assumes the experimental RDCs reflect one conformation – an assumption inconsistent with conformational averaging. Instead, we used the “ –stPales ” mode, which bypasses the experimental RDCs, and makes predictions based purely on the protein structure and shape and an a priori model of the alignment media mechanism 12. For a given set of 〈RDCj〉 values, we calculated QM, the multi-conformational analog of the standard Q:

| (5) |

Eq 5 simply replaces RDCj,CALC in the standard Q formula (Eq 3) with 〈RDCj〉. QM thus measured the ability of the multi-conformational average, 〈RDCj〉, rather than the RDC of a single conformation, to reproduce the jth experimental RDC (RDC j, EXP).

To find the optimal weights Pk, the multi-conformational fitting used a genetic algorithm (GA) approach 47, selecting for population combinations yielding lower QM. The GA approach for RDCs is similar to the Sparse Ensemble Selection model of Berlin et al. 26 in its emphasis on finding a small number of configurations that fit the data, in the hopes of facilitating physical insights; comparisons can also be made to earlier ensemble methods for RNA RDCs 48, 49, and schemes for NOE-based structure determination of bound ligands 50.

We applied the GA multi-conformational fitting to the raw Pin1 MapSGLD-NMR ensemble; this entailed an initial clustering of the 90,000 MapSGLD-NMR conformations to a smaller set of 1000 unique structures. The 1000 structures were then subjected to 1,000,000 GA steps to identify an optimal set of population weights (Further details are in Materials and Methods). From the 1000 conformers, the GA fit identified a set of 6 conformers with populations > 1.0 × 10−3 (Fig. 3A). Critically, the GA fitting allows each unique conformer to have its own alignment tensors; Table S3 in the Supporting Information lists the 4% C8E5 tensor components for the final set of six conformers. The GA conformer with the lowest single conformer Q (Q = 0.236) contributed more than 50% of the total population (Fig 3A and, Fig. S4 Supporting Information). The GA multi-conformational fitting gave a QM reduced by 17% relative to that obtained from the best single-structure (e.g. QM = 0.196 versus Q = 0.236) (Fig. 3B). These results strengthen the notion that Pin1 RDCs reflect conformational averaging.

Fig. 3.

Identification of reduced conformational ensembles using the genetic algorithm (GA) approach for multi-conformational fit 47. The bars indicate conformations with a fractional population > 0.001 for WT-Pin1 (A) and the single-substitution mutant, I28A-Pin1 (C). Linear correlation plots of predicted versus experimental 1H-15N RDCs recorded in 4% C8E5 media for WT-Pin1 (B) and I28A-Pin1 (D). Open circles (○) are RDCs predicted by the multi-conformational fit (WT QM = 0.196, I28A-Pin1 QM = 0.202); turquoise crosses ✚ are RDCs predicted by the GA ensemble conformation yielding the lowest single conformer Q factor (best single conformational fit): WT-Pin1 Q = 0.236, and I28A-Pin1 Q = 0.280.

To check whether we found a unique (global) solution corresponding to the experimental 1H-15N RDCs, we used a procedure demonstrated previously in the first paper presenting the GA method for RDCs 47. Specifically, we reran the GA fitting procedure on the 1000 Pin1 conformers 5 times, each time with different random population weights assigned to each of the 1000 conformers. Gratifyingly, in all cases, the GA fit reproduced the same six conformations and their relative population weights (Fig. S5). This demonstrates that the GA-determined set was stable, as it could be reproduced from different randomized initial populations (Fig. S5).

We also wanted to explore the sensitivity of GA-determined populations to the precision of the experimental RDCs. In principle, this could involve a Monte Carlo approach, generating hundreds of synthetic RDC data sets using Gaussian deviates based on the experimental variances. Such a procedure was used in the first paper presenting the GA multi-conformational fit for RDCs on oligo-saccharide systems (e.g. Supporting Information in Xia et al., 47). However, the larger scale of the present Pin1 RDC study presented challenges. Notably, one GA run of 1,000,000 steps required several days on a workstation to determine the population weights of 1000 conformers. This would have to be repeated for hundreds of synthetic datasets, and this proved to be impractical.

As an alternative approach, we evaluated sensitivity of the QM factors and Chi-squared values to the number of conformations in the final GA ensemble. While this was clearly not as satisfactory as a bootstrapping analysis described above, it addressed the question of the minimum number of GA conformations needed to account for the experimental RDCs within their estimated errors. Specifically, we monitored the change in QM factors and Chi-squared, as we successively omitted the lowest-populated GA conformation and renormalized the population weights for the remaining conformations. The results (Fig. S6, Supporting Information) suggested that conformations with original populations < 10% (5th and 6th conformations in the original six) could be dropped without significant changes in QM or Chi-squared.

Effects of alignment media

A persistent discrepancy emerged between the Q factors calculated from the C8E5 media RDCs versus the Pf1 phage RDCs. Including the Pf1 phage RDCs raised the Q factors for both the conventional single-conformer fits (e.g. Table 2, rows 1 and 2) and GA multi-conformational fits. We wondered if this discrepancy was related to known difficulties in predicting RDCs from protein structures in the case of electrostatically induced alignment, such as Pf1 phage 51. We investigated this possibility using the three additional 90 nanosecond MapSGLD-NMR ensembles (90,000 conformations each) listed in Table 2: (a) an ensemble restrained exclusively by 4% C8E5 RDCs; (b) an ensemble restrained by Pf1 phage RDCs exclusively; (c), and an ensemble lacking all RDC restraints. We then compared the abilities of the media-exclusive ensembles to reproduce the experimental RDCs, using both the conventional single-conformer approach, and GA multi-conformational approach.

The C8E5-only ensemble included conformers with lower PALES-predicted Q factors. As before, the GA multi-conformational search found a reduced set of 6 weighted conformers reproducing experimental C8E5 RDCs. By contrast, the Pf1-only ensemble had conformers with typically higher PALES-predicted Q factors, and GA multi-conformational search failed to find a reduced ensemble to reproduce the experimental Pf1 RDC values. We also investigated the cross-fitting capabilities of the media-specific ensembles. We found that the Pf1-only ensemble gave a poorer fit of the 4% C8E5 RDCs compared to the 4% C8E5-only ensemble. Similarly, the 4% C8E5-only ensemble gave a poorer fit of the phage RDCs compared to the phage-only ensemble.

The above results are consistent with the notion that the discrepancies stemmed from greater difficulties in model-based predictions of electrostatic (Pf1-phage) as opposed to collision-induced (4% C8E5) alignment. For electrostatic media, alignment tensor predictions rely on knowledge of the charge distribution over the whole protein; that distribution varies with force fields and electrostatic models, and the optimal choice is not obvious.

It is worth noting here that the uneven success of model-based predictions alignment tensors media underscores an advantage of the MapSGLD-NMR simulations. For MapSGLD-NMR, the simulations optimize the alignment tensor components (and RDC values) directly at each time step via minimization of the RDC restraint potential (Eq 1). As such, the resulting MapSGLD-NMR tensors are independent from a priori model assumptions concerning the physical mechanism of the alignment media. This independence is appealing when considering the standard imperative that getting a reliable conformational ensemble requires RDCs from numerous different alignment media, some of which may be incompatible with protein function or stability, or perturb the distribution of conformations sampled in different ways.

While the GA multi-conformational search had difficulties in reproducing the Pf1 RDCs, it worked well with the C8E5 RDCs, producing a “basis set” of six population-weighted conformers that capture the essential features of the overall C8E5 ensemble. This is very encouraging as it suggests a reasonable conformational ensemble can be obtained without measurements across a large number (> 5) of alignment media. This reduced GA description should prove more tractable for future modeling studies involving Pin1 binding modes.

Description of the Pin1 Interdomain Ensemble

To describe the distribution of interdomain orientations, we used a fictitious interdomain vector connecting the geometric centers of the catalytic pocket PPIase domain catalytic site to the WW domain substrate-binding loop (residues 16-21) (Fig. 4A). We defined the vector coordinates ( r, θ, ϕ) in the principal axes frame of the PPIase domain inertia tensor, which remained immobile throughout the MapSGLD-NMR simulations. We defined the polar angle θ such that it ends to 180° as the domains adopt a more extended configuration, with the WW domain along the Z principal axis of the PPIase inertia tensor. We then polled the ( r, θ, ϕ) values, as well as the radius of gyration for the 90,000 conformers of the raw MapSGLD-NMR ensemble, resulting in the histograms of Figs 4C–F.

Fig. 4.

WT-Pin1 conformations sampled by three 30ns AMBER simulations, using the MapSGLD-NMR protocol. The simulations started from three different structures (1NMV-1, 1NMV-2, and 1NMV-3) producing a total of 90,000 conformations. (A) The relative domain orientation is specified by an interdomain vector (green arrow) that starts at the geometric center of the PPIase domain active site and ends at the geometric center of the WW domain substrate-binding loop (residues 16-21). The interdomain vector coordinates (length

r and angles θ and ϕ) are in the principle axis frame of the PPIase domain inertia tensor. (B) The six conformers identified by the GA/Multi-conformational search, and their corresponding interdomain vectors (green arrows defined in (A)). Panels (C–E) show histograms for the spherical coordinates of the interdomain vector, including (C) the radial (distance) coordinate

r; (D) the polar angle θ; and (E) the azimuthal angle ϕ. Panel (F) is the average and the radius of gyration. Black bars represent the 90,000 conformations of the raw WT MapSGLD-NMR ensemble; the red trace represents the analogous 90,000 conformations for the raw I28A MapSGLD-NMR ensemble. Green diamonds (◆) indicate the six WT conformers; red x’s (

) indicate the seven I28A conformers identified by GA/multi-conformational search; stacked diamonds/x’s are populations in nearly the same bins. Panels (G and H) compare conformations sampled by the raw WT-Pin1 versus I28A-Pin1 ensembles (i.e. MapSGLD-NMR simulations producing 90,000 conformations). Yellow-orange ribbons indicate the most frequently sampled conformation; magenta indicates a less populated conformation.

) indicate the seven I28A conformers identified by GA/multi-conformational search; stacked diamonds/x’s are populations in nearly the same bins. Panels (G and H) compare conformations sampled by the raw WT-Pin1 versus I28A-Pin1 ensembles (i.e. MapSGLD-NMR simulations producing 90,000 conformations). Yellow-orange ribbons indicate the most frequently sampled conformation; magenta indicates a less populated conformation.

The histograms for “ r” and the radius of gyration showed both compact and extended conformations, with the compact conformations being more prevalent. The compact conformations do not show direct interdomain contact, nor are they as compact as depicted in the crystal structures 1PIN 31 or 1F8A 32. However, we note that the crystal structures were actually Pin1 complexes, such as ala-cis-pro dipeptide in the PPIase active site in 1PIN 31 and a doubly phosphorylated CTD peptide bound to the WW domain 32.

It is also worth emphasizing that the RDCs do not directly restrain the interdomain distance; they report mainly on HN bond orientation. This also influences the prevalence of extended versus compacted domains within the ensemble. Conceivably, adding distinct NMR restraints based on parameters more sensitive to interdomain proximity (e.g. PREs 52) would produce conformers with closer interdomain contact. We also mapped the interdomain vector coordinates of the six GA-selected ensemble for WT-Pin1 (Fig. 4B). Their values for ( r, θ, ϕ) and the radius of gyration correspond to the green diamonds in Figs 4C–F.

Factors Influencing Conformational Searching

We investigated the influence of the NMR RDC restraints on the trajectories, by comparing the range of r and θ values for 20 nanoseconds MapSGLD simulations with and without NMR-RDC restraints (i.e. MapSGLD in Fig. 5A versus MapSGLD-NMR in Fig. 5B). Including the RDC restraints clearly reduced the number of conformations with smaller interdomain distances and angles.

Fig. 5.

2-d histograms comparing the conformational space sampled by (A) 20 nanoseconds rigid-body Map-SGLD-NMR simulations, implicit solvent model, and map and RDC restraints enforced; (B) 20 nanoseconds Map-SGLD simulation, implicit solvent model, map restraints enforced but RDC restraints absent; (C) depicts 400 nanoseconds explicit-solvent simulations lacking both map and RDC restraints. Comparison of (A) and (B) indicates certain conformations are excluded by the RDC data; Comparison of (B) and (C) indicates many conformations are not sampled in the explicit-solvent simulation. All simulations were started from the same structure, marked by the star.

We also compared the conformational space explored by MapSGLD versus conventional explicit-solvent simulations. We examined the breadth of sampling by the aforementioned 20ns MapSGLD simulation (~5 days CPU time, Fig. 5B) versus that of a 400 nanoseconds standard explicit-solvent simulation (~1 month CPU time, Fig. 5C), both in the absence of any RDC restraints. Per Figs 5B, C, the 20 nanoseconds of rigid-body MapSGLD simulations (implicit solvent) covered a substantially broader r and θ range (broader range of motion between the domains) than even 400 nanoseconds of standard explicit-solvent MD. The increased search space by MapSGLD is noteworthy, given its nearly 6-fold reduction in CPU time compared to the explicit solvent simulation.

Wild-Type Pin1 versus I28A Ensembles

We wanted to investigate the validity of the MapSGLD-NMR ensembles. Previous validation strategies have used a cross-validation approach – generating conformational ensembles from a subset of a large and diverse set of RDCs and then evaluating the ensemble’s ability to predict RDCs excluded from ensemble generation (i.e. that were not used as restraints) 53–55.

Unfortunately, we lacked a sufficiently large set of RDCs for this type of cross-validation. We therefore pursued an indirect approach, investigating the consistency of the MapSGLD-NMR ensembles with the findings from our previous studies of Pin1 versus I28A interdomain motion 36. Critically, those findings were based on comparisons of NH chemical shift perturbations and 15N spin relaxation parameters excluded from the present ensemble generation. Moreover, those previous studies showed that I28A, a single site substitution in the WW domain β2-β3 hairpin (see Fig. 1), decreased the transient interdomain contact compared to that observed in wild-type (WT) Pin1. Here, we investigated whether an I28A-Pin1 MapSGLD-NMR ensemble based on I28A-Pin1 RDCs, would have features consistent with the reduced interdomain contact. This query addresses cross-validation, in that it examines the consistency of the RDC-based ensemble with results from non-RDC parameters excluded from ensemble generation.

Fig. 1.

Human Pin1, a two-domain mitotic regulator with PPIase (cyan) and WW (magenta) domains; the structure is a snapshot from a 30ns MapSGLD-NMR simulation started from a conformer of 1NMV 33. The –Z and –X axes are the principal axes of PPIase domain inertia tensor (origin at its center of mass). Linker flexibility (green curved arrow) enables relative domain motion. Residue I28 lies in the WW domain (Yellow), the site of the I28A substitution. The strategy for simulating interdomain motion is: (i) strong Cartesian restraints hold the PPIase fixed in space, (ii) while the WW domain moves as a nearly rigid body by map restraints (green curved arrow).

Toward this end, we subjected I28A-Pin1 to the same experiments and ensemble analysis carried out for WT-Pin1. Specifically, we measured I28A-Pin1 NH RDCs (83 RDCs 4% C8E5 media, 94 RDCs Pf1 phage) and verified dataset independence via a dot product analysis (Table S2, Supporting Information). We then generated a MapSGLD-NMR ensemble of 90,000 conformations for I28A-Pin1. The raw ensemble furnished a basis for the GA based multi-conformational fit, which identified seven population-weighted I28A-Pin1 conformers (cutoff population ≥ 0.001), each with their own alignment tensor (Table S4, Supporting Information). We then compared the raw I28A- and WT-Pin1 ensembles (Fig. 4), with attention to the same interdomain vector depicted in Fig. 4A and the radius of gyration.

The histograms for length ( r) and the radius of gyration were particularly revealing. They showed that the I28A-Pin1 ensemble preferred conformations that were more extended (longer “ r” and a longer radius of gyration), than those in the WT-Pin1 ensemble. Greater extension in I28A-Pin1 was also apparent in the θ (polar angle) histogram, which skewed to values closer to 180°, indicating a higher preference for extended interdomain conformations than WT-Pin1. These differences between the I28A- and WT-Pin1 ensembles were consistent with the decreased levels of interdomain contact inferred from our previous 15N spin-relaxation studies 36, 39. The shift to more extended conformations apparently decreased the uniformity of the ϕ. In particular, the I28A-Pin1 ϕ distribution was less broad than WT, and noticeably depopulated in the range (50° < ϕ < 120°). The “dot clouds” of Fig. 6 give another view of the differences between the I28A-Pin1 and WT-Pin1 ensembles. The dots, gold for I28A-Pin1 and blue for WT-Pin1, are the tips of the interdomain vector that start in the PPIase domain active site and terminate at the WW domain substrate-binding loop, for various ensemble snapshots. The dots help visualize the distribution of WW orientations relative to the fixed PPIase domain for both I28A-Pin1 and WT-Pin1. Non-overlapping regions of dots highlight differences in orientational preferences for the two constructs.

Fig. 6.

Comparison of interdomain vector orientations ( r, Θ, ϕ) sampled by WT-Pin1 and I28A-Pin1. The PPIase domains are superimposed and fixed (cyan); the black lines are the –X and –Z principal axes of its inertia tensor. The dots represent the tips of the interdomain vectors starting at the geometric center of the PPIase domain active site, and terminating at the geometric center of the WW domain-binding loop. Blue dots are the WT-Pin1 ensemble; gold dots are the I28A-Pin1 ensemble. The interdomain vectors (red lines) and WW domains (dark blue) for conformers 4 and 6 from the WT GA ensemble are shown.

Closer examination of the less populated conformations within both the WT-Pin1 and I28A-Pin1 ensembles showed I28A-Pin1 could become more compact than WT-Pin1. A plausible explanation for this is that in WT-Pin1, greater side chain steric repulsion (I instead of A) discourages these more compact conformations. We return to this issue in the Discussion subsection below.

Collectively, the above differences suggest (i) I28A-Pin1 samples a broader span of conformations than WT-Pin1; (ii) the more populated conformations of I28A-Pin1 are more extended than those of WT-Pin1. These results are consistent with the decreased level of interdomain contact and greater interdomain mobility inferred from our previous 15N spin-relaxation for I28A vs. WT-Pin1 36.

DISCUSSION

Multi-domain signaling proteins such as Pin1 consist of flexibly linked globular domains that can sample a multiplicity of conformations involving different domain orientations. NMR RDCs measured for these domains reflect averages over their orientational fluctuations. Interpreting their RDCs thus requires a description in terms of conformational ensembles. The present work addressed this challenge by introducing a new protocol: MapSGLD-NMR simulations. MapSGLD-NMR promotes efficient and broad conformational sampling of interdomain motion via four main routes: (i) use of an implicit solvent model; (ii) self-guiding forces that enhance slower and more collective motion; (iii) map-restraints that enable quasi-rigid body motion of domains, while retaining a full-atom description of the protein; (iv) inclusion of site-specific NMR restraints. Our results show that the MapSGLD-NMR simulations give an ensemble of conformations consistent with NMR RDCs, with the more frequently visited structures corresponding to the more relevant structures. The MapSGLD-NMR ensemble provides raw material for fitting the experimental RDCs in terms of a reduced set of population-weighted conformers. In particular, the GA/multi-conformational search 47 can define a set of population-weighted conformations derived from the raw ensemble.

We demonstrated MapSGLD-NMR by applying it to the human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1, an essential mitotic regulator consisting of a catalytic PPIase domain and a WW domain (binding module). Their connection via a disordered linker, in principle, allows for a substantial range of domain motion. However, the nature of the conformations sampled by motion has remained obscure. The MapSGLD-NMR ensemble provides a first glimpse of range of Pin1 interdomain orientations at atomic resolution. In turn, this provides a basis for understanding the biological implications of Pin1 interdomain motion, in particular, how it may affect its role as an essential mitotic regulator 27, 56–58. We discuss this below.

Pin1 regulates the activity of numerous cell cycle phosphoproteins, including the oncoprotein c-Myc 59 and the p53 tumor suppressor 60. A recent tally indicates Pin1 substrates include over 40 oncogenes and 20 tumor suppressors 30, 61, 62. Some of these interactions occur in the nucleus (nuclear speckle) while others are in the cytoplasm. In all cases, Pin1 targets phospho-Ser/Thr-Pro (pS/T-P) motifs of its protein substrates; both the WW and PPIase domains recognize these motifs and can be simultaneously occupied by pS/T-P motifs 35. A natural and open question persists: what atomic properties of Pin1 enable to interact with so many different targets in different cell milieus?

The MapSGLD-NMR ensemble of Pin1 suggests that interdomain flexibility as one of those properties. The ensemble samples a broad range of domain orientations that generally disfavor highly collapsed conformations. Relative domain flexibility, and the preference for more open conformation make sense in light of the physical phenotypes of Pin1 target sites. In particular, Pin1 target sites (pS/T-P motifs) typically reside within intrinsically disordered regions (IDR) of the substrate proteins 38, 63. Extensive interdomain flexibility could help Pin1 adapt to these “moving targets”. Moreover, many Pin1 substrates have multiple pS/T-P sites and Pin1 interdomain motion could allow for multivalent recognition. As we have speculated previously, it is conceivable Pin1 could dock at one pS/T-P motif first via its WW domain; interdomain flexibility would then enable the PPIase domain to search for proximal pS/T-P sites 38, 39 in a manner resembling “fly-casting” 64.

The MapSGLD-NMR ensembles also give insight into the breadth of domain orientations supporting Pin1 function. This was illustrated in the comparison of MapSGLD-NMR ensembles of WT-Pin1 versus I28A-Pin1. As stated, the single I-to-A substitution in the WW domain β2-β3 hairpin (Fig. 1) that gives rise to weaker interdomain contact and a modest increase of PPIase isomerase activity 36, 39. Fig. 4 shows that the most populated conformations for I28A reside in a different region of r, θ and ϕ space from WT. Per Fig 4c–h, the more populated I28A-Pin1 conformations are more extended than those of WT-Pin1. Yet, Fig. 4c–h also shows that the less populated I28A-Pin1 conformations could be more compact than those of the WT-Pin1. Closer inspection of these compact I28A-Pin1 conformations do not establish the interdomain contact of WT; in particular, the WW domain β2/β3 turn is improperly oriented away from the PPIase domain interface. In effect, the I28A-Pin1 ensemble suggests that the linker flexibility is such that there are multiple ways for the two domains to become “compact” without properly forming interdomain contact. Moreover, the I28A substitution may decrease WT interdomain contact, not only by distance effects, but also by inhibiting proper interdomain orientation. This would be consistent with our results in Fig 4d–e showing that I28A samples smaller and larger values of θ, and ϕ than WT Pin1. The RDC restraints alone are insufficient to distinguish distance versus angular effects. For that, we would need to enhance our simulations with complementary NMR parameters more sensitive to distance effects, such as Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancements (PRE).

It is also worth mentioning the functional implications of our difficulties in finding a conformational ensemble compatible with both the 4%C8E5 and Pf1 phage RDCs. As stated, these difficulties may reflect limitations of the PALES predictions for phage RDCs. However, another possibility is that Pin1 samples a slightly different distribution of domain orientations in the Pf1 phage versus 4% C8E5 media. Indeed, some NH resonances of the WW domain showed slight differences in chemical shifts and line-broadening between the two media. This accounted for the difference in the number of NHs pruned from the raw RDC data on account of overlap or poor signal to noise. These differences, combined with the rather different alignment tensor principal values (e.g. Azz), suggest Pin1 may adopt slightly different conformational ensembles between the two media, and that our simulations may not have been long enough to capture the breadth of conformations in Pf1 phage.

With MapSGLD-NMR, it should be possible to extend our findings here. For example, point mutations such as I28A are straightforward, experimentally and in silico, and thus provide a simple perturbative means to gain more insights about interdomain mobility. MapSGLD-NMR can also account for the effects of ligand interactions implicitly, by including bound-state NMR data into the simulation. Also, relaxation of the EMAP restraints would allow greater intradomain mobility; in principle, this would allow us to explore the possible interplay between intra- and interdomain dynamics.

Larger systems may also benefit from the MapSGLD-NMR method because Emap greatly reduces the computational expense for moving domains, and multiple Emap constraints can be used in a single simulation.22 The efficiency gain may be even greater for larger protein complexes because a larger portion of atoms may be included in the rigid-bodies instead of treated atomically, thus requiring less computing power.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the MapSGLD-NMR method, which combines simulation and experimental NMR parameters to extend current capabilities for investigating interdomain motions of modular proteins. MapSGLD-NMR provides a straightforward and efficient method for determining the conformational ensemble underlying NMR-RDC data. Moreover, it may be extended to other experimental restraints that are sensitive to domain motion (e.g. chemical shifts, spin relaxation rates, paramagnetic relaxation enhancements), which may be essential for investigating more complicated domain motion, or for finer distinction of dynamic behavior.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pin1 Sample Preparation

U-15N Pin1 was over-expressed and purified as previously described.65 The final NMR buffer was 30 mM imidazole-D4, pH 6.6 with 30 mM NaCl, 0.03% NaN3, 5 mM DTT-D10 and 90% H2O/10% D2O. Partial alignment for residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) was induced with a mixture of C8E5/octanol 40 or 10 mg/ml Pf1 phage 66. A 10% stock solution of C8E5 media was prepared by dissolving C8E5 in NMR buffer, pH-adjustment, sterile filtering, and adding octanol to a molar ratio of 0.87. Stock solutions of each media were added to stock solutions of Pin1 to a final concentration of 250 μM protein and 4% (w/vol) C8E5 media or 10–20 mg/mL Pf1 phage. In Pf1 phage samples, we increased the buffer ionic strength 100 mM imidazole-D4 and 100 mM NaCl to reduce interactions with phage.

NMR Measurements of HN RDCs

Backbone NH RDCs were measured in triplicate using the standard in-phase/antiphase (IPAP) 2D 1H 15N HSQC pulse scheme 67. All NMR measurements were at a nominal temperature of 295 K on Bruker Avance spectrometers (16.4 T or 18.8 T) equipped with TCI cryogenic probes. The 2D datasets (15N dimension (ω1/t1): 64 complex points in t1, sweep width of 35.2351 ppm, carrier at 118 ppm, and 32 scans per t1; 1H dimension (ω2/t2): 1024 points in t2, 15.0031 ppm, carrier at 4.703 ppm) were apodized and Fourier-transformed using Topspin 2.1 (Bruker Biospin, Inc.). The raw 1H-15N couplings were measured from the frequency separation of 15N doublet members along the 15N dimension, using Sparky 3 (T. D. Goddard and D. G. Kneller, SPARKY 3, University of California, San Francisco). The NH RDCs were calculated as the Hertz difference between the raw couplings observed in aligned media versus non-aligned media. Statistical uncertainties were estimated by taking the standard deviation among RDC values measured in triplicate. The average uncertainties were1.52 Hz for 4% C8E5, and 1.04 Hz for Pf1 phage. The initial alignment tensors to assess the independence of RDC datasets were obtained using the Prediction of ALignmEnt from Structure (PALES) software from Zweckstetter and Bax 11, 12 (e.g. Fig. S1).

Map-restrained Self-Guided Langevin Dynamics

To generate Pin1 conformations relevant to NH RDCs, we pursued an MD strategy that emphasized relative domain motion, rather than intradomain motion. Specifically, we fixed the PPIase domain in space, and then moved the WW domain relative to it as a nearly rigid body (Fig. 1). We immobilized the PPIase domain atoms using strong Cartesian harmonic restraints (force constants of 1.0 kcal/mol·Å2); indeed, the PPIase RMSD values < 0.5 Å over the simulations (Fig. S3). To move the WW domain as a nearly rigid body, we used self-guided Langevin dynamics 68 together with map-restraints 23 – a method previously described as MapSGLD 22. Each “ith” atom obeyed the equations of motion

| (6) |

The right-hand-side of Eq 6 denotes three types of forces. The first type, in the parentheses, are standard Langevin dynamics (LD) forces which include spatial gradients of the AMBER12 potential function (FF12SB) 69, 70, a solvent drag force -γpi, and a delta-correlated random force Ri. The drag and random forces constitute the implicit solvent model.

The second type of force is the guiding-force “gi” that distinguishes SGLD from standard LD. The guiding force promotes low frequency, collective motions, such as domain re-orientation. It consists of two parts

| (7) |

The first part is the local time average of the momentum, 〈p(t)〉L, which filters for lower frequency collective motions. Local time-averaging occurs over a duration tL = 0.5 picoseconds (10−12 sec) that far exceeds the basic simulation time-step, δτ = 1 femtoseconds (10−15 sec). The second term has a ξ factor that compensates for the spurious energy increase that would otherwise come from gi. λ sets the overall strength of gi.

The third force term on the far-right term of Eq 1, fi,MAP, refers to a protein map function (‘map’, hereafter) and its restraint potential 23. The map is what allows a group of atoms to move as a nearly rigid structure, while maintaining its full atomic description. More specifically, the map is an effective mass density ρ(xi, yj, zk), defined on a 3-d lattice of points, and created from atomic structural coordinates 22. The deviation from complete rigidity is controlled by the assumed resolution of the density map. We defined the Pin1 WW map from its coordinates in PDB deposition 1NMV 33. The map and its average value, ρ̄, were incorporated into the restraint potential,

| (8) |

where CMAP sets the overall magnitude (CMAP = 0.1kcal/amu). The sum includes all atoms of the WW domain, and a normalized map is used where δρ = 1 Å−3 22. Other critical parameters values are in Table 1. The essential feature of Eq 8 is that EMAP decreases when the WW domain coordinates adopt configurations reproducing the initial map density. The fi,MAP terms are the spatial gradients of EMAP that push WW domain atoms to positions reducing EMAP, thereby maintaining its internal atomic structure. In this manner, EMAP and fi,MAP promote nearly rigid body motion of the WW domain while maintaining its full-atom description. We chose parameters that kept the internal structure of the WW domain within about 1 Å of its initial structure (see Fig. S3, Supporting Information).

Map restraints and MapSGLD-NMR Simulations

Both MapSGLD-NMR and standard explicit solvent simulations were conducted in AMBER 12 69 using the ff12SB force field. For the initial Pin1 coordinates, we used three structures from the PDB deposition 1NMV, the results of the NMR structure determination of apo Pin1 33. For each initial structure, we generated AMBER topology and coordinate files using the auxiliary program, “tleap”. Each initial set of coordinates then underwent 500 steps of energy minimization (without NMR restraint potentials), using the improved constant pH generalized Born implicit solvent with a 12 Å cut-off 71, 72. Typical energy reductions were to −3000 – −5000 kcal/mole. To generate the RDC restraint potentials, we used the AMBER auxiliary program, make_dip_RST.protein. The resulting restraint potentials ERDC were of the form given in Eq 1 above.

The MapSGLD-NMR simulations moved the Pin1 WW domain as a rigid body relative to a fixed PPIase domain using EMAP per Eq 8 above 22. The map function is an effective density function ρ̂(xI, yJ, zK) defined on a 3-d grid of NX NY NZ points, where

| (9) |

and

| (10) |

The summation indices are over the grid points defining the map function. The map function ρ(x,y,z) describes the internal shape of the WW domain to be maintained. The WW domain rigidity was adjusted using the map resolution parameter, RMAP, which has dimensions of length Smaller RMAP describes the targeted conformation with finer grid spacing. Thus, EMAP potentials with smaller RMAP increase internal domain rigidity; this includes bond vector mobility that would affect the scaling parameter SHN in Eq 2. We used a small value of RMAP = 5 Å, which led to a WW domain RMSD of ~2.0 Å.

Explicit Solvent MD simulations

We ran standard MD simulations in explicit solvent using the TIP4P water model 73 and the same AMBER ff12SB force field. The initial Pin1 structure for these simulations was the first structure (1NMV-1) from the NMR solution structure 1NMV 33. The initial structure was energy minimized as follows: the protons were first minimized for 1000 steps, then the solvent was minimized for 1000 steps, then the whole system was minimized for 2500 steps. The system was then equilibrated at constant volume for 40 picoseconds and at constant pressure for 40 picoseconds, while the protein was restrained. The production run was a 400 nanoseconds simulation using Particle Mesh Ewald Molecular Dynamics (PMEMD) using an NVIDIA GPU C2050 card on a local machine at Rutgers University.

Trajectory Analysis

For all simulations, we monitored kinetic and potential energies using the publicly available Perl script, proc_out_md.perl. The potential energies included the standard AMBER protein potential,69 and those of the EMAP and NMR ERDC restraint potentials. To calculate histograms of selected angles and distances, and RMSDs, we used the CPPTRAJ tool in AMBER12.

Genetic Algorithm/Multi-conformational Search

The genetic algorithm (GA) multi-conformational search 47 was performed on raw MapSGLD-NMR ensembles (90,000 conformations). Prior to GA fitting, we trimmed the raw MapSGLD-NMR ensemble by clustering conformations according to the coordinates interdomain vector coordinates of Fig. 4. We assigned conformations to different “boxes” within a 3-d grid, each box with edges of 2 Å × 2 deg × 2 deg. Then, all conformers in the same box were replaced by the single conformation with the lowest individual QRDC factor, as calculated using PALES in the “ –stPales ” mode. For the MapSGLD-NMR ensemble based on both alignment media, this approach reduced the raw 90,000 conformations to 1000 conformations. We then performed 1,000,000 GA steps on these reduced ensembles, and converged to a final ensemble of six conformers (Fig’s 3, 4) with fractional populations > 0.001.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Efficient generation of conformational ensembles for NMR probes of domain motion

Protocol combines self-guided Langevin dynamics with map and NMR RDC restraints

NH RDCs fit to weighted populations of domain conformations; applied to human Pin1

RDC-based ensembles support findings of other Pin1 NMR parameters

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grant No. RO1-GM083081 to J.W.P., NIH training grant T32GM075762 to J.J.B., and NIH Grant GM103297 to D.A.C. Computing resources at Rutgers were funded in part by NIH grant S10OD012346-01A1. We thank Dr. Xiongwu Wu, Dr. In-Suk Joung, Dr. Pawel Janowski, Dr. Brendan Mahoney, Ms. Meiling Zhang, Dr. Kimberly Wilson, Dr. Xingsheng Wang, and Dr. Thomas Frederick for valuable suggestions and useful discussions.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SGLD

self-guided Langevin Dynamics

- PPIase

peptidyl-prolyl isomerase

- RDC

residual dipolar coupling

- GA

genetic algorithm

- WT

wild-type

- IPAP

in-phase antiphase

- PALES

“Prediction of ALignmEnt from Structure”

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: RDC values, PALES analysis, metrics demonstrating the stability of the simulations, and further details of the GA analysis.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pufall MA, Graves BJ. Autoinhibitory domains: modular effectors of cellular regulation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2002;18:421–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.031502.133614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhattacharyya RP, Remenyi A, Yeh BJ, Lim WA. Domains, motifs, and scaffolds: The role of modular interactions in the evolution and wiring of cell signaling circuits. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2006:655–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lim WA. Designing customized cell signalling circuits. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2010;11:393–403. doi: 10.1038/nrm2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bax A. Weak alignment offers new NMR opportunities to study protein structure and dynamics. Protein Sci. 2003;12:1–16. doi: 10.1110/ps.0233303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tolman JR, Flanagan JM, Kennedy MA, Prestegard JH. NMR evidence for slow collective motions in cyanometmyoglobin. Nature Structural Biology. 1997;4:292–7. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tjandra N, Bax A. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 1997;278:1111–4. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolman JR, Prestegard JH. A quantitative J-correlation experiment for the accurate measurement of one-bond amide 15N-1H couplings in proteins. J Magn Reson B. 1996;112:245–52. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottiger M, Delaglio F, Bax A. Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J Magn Reson. 1998;131:373–8. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Losonczi JA, Andrec M, Fischer MWF, Prestegard JH. Order matrix analysis of residual dipolar couplings using singular value decomposition. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 1999;138:334–42. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tolman JR, Ruan K. NMR residual dipolar couplings as probes of biomolecular dynamics. Chem Rev. 2006;106:1720–36. doi: 10.1021/cr040429z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. Prediction of sterically induced alignment in a dilute liquid crystalline phase: Aid to protein structure determination by NMR. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:3791–2. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zweckstetter M. NMR: prediction of molecular alignment from structure using the PALES software. Nature Protocols. 2008;3:679–90. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Case DA. Molecular dynamics and NMR spin relaxation in proteins. Acc Chem Res. 2002;35:325–31. doi: 10.1021/ar010020l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Gunsteren WF, Brunne RM, Gros P, van Schaik RC, Schiffer CA, Torda AE. Accounting for molecular mobility in structure determination based on nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopic and X-ray diffraction data. Methods Enzymol. 1994;239:619–54. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)39024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruschweiler R, Case DA. Collective NMR relaxation model applied to protein dynamics. Phys Rev Lett. 1994;72:940–3. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bruschweiler R, Roux B, Blackledge M, Griesinger C, Karplus M, Ernst RR. Influence of rapid intramolecular motion on NMR cross-relaxation rates. A molecular dynamics study of antamanide in solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:2289–302. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw DE, Maragakis P, Lindorff-Larsen K, Piana S, Dror RO, Eastwood MP, et al. Atomic-level characterization of the structural dynamics of proteins. Science. 2010;330:341–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1187409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garcia de la Torre J, Ortega A, Perez Sanchez HE, Hernandez Cifre JG. MULTIHYDRO and MONTEHYDRO: conformational search and Monte Carlo calculation of solution properties of rigid or flexible bead models. Biophys Chem. 2005;116:121–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernado P, Fernandes MX, Jacobs DM, Fiebig K, de la Torre JG, Pons M. Interpretation of NMR relaxation properties of Pin1, a two-domain protein, based on Brownian dynamic simulations. Journal of Biomolecular Nmr. 2004;29:21–35. doi: 10.1023/B:JNMR.0000019499.60777.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia de la Torre J, Navarro S, Lopez Martinez MC, Diaz FG, Lopez Cascales JJ. HYDRO: a computer program for the prediction of hydrodynamic properties of macromolecules. Biophys J. 1994;67:530–1. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80512-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsui V, Zhu LM, Huang TH, Wright PE, Case DA. Assessment of zinc finger orientations by residual dipolar coupling constants. Journal of Biomolecular Nmr. 2000;16:9–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1008302430561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Subramaniam S, Case DA, Wu KW, Brooks BR. Targeted conformational search with map-restrained self-guided Langevin dynamics: application to flexible fitting into electron microscopic density maps. J Struct Biol. 2013;183:429–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu XW, Milne JLS, Borgnia MJ, Rostapshov AV, Subramaniam S, Brooks BR. A core-weighted fitting method for docking atomic structures into low-resolution maps: Application to cryo-electron microscopy. Journal of Structural Biology. 2003;141:63–76. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia JC, Margulis CJ, Case DA. Searching and Optimizing Structure Ensembles for Complex Flexible Sugars. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2011;133:15252–5. doi: 10.1021/ja205251j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salmon L, Bascom G, Andricioaei I, Al-Hashimi HM. A general method for constructing atomic-resolution RNA ensembles using NMR residual dipolar couplings: the basis for interhelical motions revealed. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:5457–66. doi: 10.1021/ja400920w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berlin K, Castaneda CA, Schneidman-Duhovny D, Sali A, Nava-Tudela A, Fushman D. Recovering a representative conformational ensemble from underdetermined macromolecular structural data. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16595–609. doi: 10.1021/ja4083717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu KP, Hanes SD, Hunter T. A human peptidyl-prolyl isomerase essential for regulation of mitosis. Nature. 1996;380:544–7. doi: 10.1038/380544a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu PJ, Wulf G, Zhou XZ, Davies P, Lu KP. The prolyl isomerase Pin1 restores the function of Alzheimer-associated phosphorylated tau protein. Nature. 1999;399:784–8. doi: 10.1038/21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao XH, Zhang AL, Zheng M, Li MQ, Chen CP, Xu H, et al. Chemical or genetic Pin1 inhibition exerts potent anticancer activity against hepatocellular carcinoma by blocking multiple cancer-driving pathways. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43639. doi: 10.1038/srep43639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou XZ, Lu KP. The isomerase PIN1 controls numerous cancer-driving pathways and is a unique drug target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:463–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ranganathan R, Lu KP, Hunter T, Noel JP. Structural and functional analysis of the mitotic rotamase Pin1 suggests substrate recognition is phosphorylation dependent. Cell. 1997;89:875–86. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Verdecia MA, Bowman ME, Lu KP, Hunter T, Noel JP. Structural basis for phosphoserine-proline recognition by group IVWW domains. Nature Structural Biology. 2000;7:639–43. doi: 10.1038/77929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayer E, Goettsch S, Mueller JW, Griewel B, Guiberman E, Mayr LM, et al. Structural analysis of the mitotic regulator hPin1 in solution - Insights into domain architecture and substrate binding. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:26183–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300721200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobs DM, Saxena K, Vogtherr M, Bernado P, Pons M, Fiebig KM. Peptide binding induces large scale changes in inter-domain mobility in human Pin1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:26174–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Namanja AT, Wang XDJ, Xu BL, Mercedes-Camacho AY, Wilson KA, Etzkorn FA, et al. Stereospecific gating of functional motions in Pin1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:12289–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019382108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson KA, Bouchard JJ, Peng JW. Interdomain interactions support interdomain communication in human Pin1. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6968–81. doi: 10.1021/bi401057x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Mahoney B, Zhang M, Zintsmaster JS, Peng JW. Negative Regulation of Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerase Activity by Interdomain Contact in Human Pin1. Structure. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.08.019. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng JW. Investigating Dynamic Interdomain Allostery in Pin1. Biophys Rev. 2015;7:239–49. doi: 10.1007/s12551-015-0171-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang X, Mahoney BJ, Zhang M, Zintsmaster JS, Peng JW. Negative Regulation of Peptidyl-Prolyl Isomerase Activity by Interdomain Contact in Human Pin1. Structure. 2015;23:2224–33. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruckert M, Otting G. Alignment of biological macromolecules in novel nonionic liquid crystalline media for NMR experiments. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2000;122:7793–7. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen MR, Hanson P, Pardi A. Pf1 filamentous phage as an alignment tool for generating local and global structural information in nucleic acids. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2000;17(Suppl 1):365–9. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2000.10506642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moltke S, Grzesiek S. Structural constraints from residual tensorial couplings in high resolution NMR without an explicit term for the alignment tensor. J Biomol NMR. 1999;15:77–82. doi: 10.1023/A:1008309630377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tolman JR. A novel approach to the retrieval of structural and dynamic information from residual dipolar couplings using several oriented media in biomolecular NMR spectroscopy. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2002;124:12020–30. doi: 10.1021/ja0261123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipari G, Szabo A. Model-Free Approach to the Interpretation of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Relaxation in Macromolecules. 1. Theory and Range of Validity. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:4546–59. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cornilescu G, Marquardt JL, Ottiger M, Bax A. Validation of Protein Structure from Anisotropic Carbonyl Chemical Shifts in a Dilute Liquid Crystalline Phase. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:6836–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montalvao RW, De Simone A, Vendruscolo M. Determination of structural fluctuations of proteins from structure-based calculations of residual dipolar couplings. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:281–92. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9644-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia J, Margulis CJ, Case DA. Searching and optimizing structure ensembles for complex flexible sugars. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:15252–5. doi: 10.1021/ja205251j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher CK, Zhang Q, Stelzer A, Al-Hashimi HM. Ultrahigh resolution characterization of domain motions and correlations by multialignment and multireference residual dipolar coupling NMR. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:16815–22. doi: 10.1021/jp806188j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frank AT, Stelzer AC, Al-Hashimi HM, Andricioaei I. Constructing RNA dynamical ensembles by combining MD and motionally decoupled NMR RDCs: new insights into RNA dynamics and adaptive ligand recognition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:3670–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearlman DA. FINGAR: A new genetic algorithm-based method for fitting NMR data. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:49–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00198139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zweckstetter M, Hummer G, Bax A. Prediction of charge-induced molecular alignment of biomolecules dissolved in dilute liquid-crystalline phases. Biophysical journal. 2004;86:3444–60. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iwahara J, Tang C, Marius Clore G. Practical aspects of (1)H transverse paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements on macromolecules. J Magn Reson. 2007;184:185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clore GM, Schwieters CD. How much backbone motion in ubiquitin is required to account for dipolar coupling data measured in multiple alignment media as assessed by independent cross-validation? Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2004;126:2923–38. doi: 10.1021/ja0386804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lange OF, Lakomek NA, Fares C, Schroder GF, Walter KF, Becker S, et al. Recognition dynamics up to microseconds revealed from an RDC-derived ubiquitin ensemble in solution. Science. 2008;320:1471–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1157092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blackledge M. Recent progress in the study of biomolecular structure and dynamics in solution from residual dipolar couplings. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectr. 2005;46:23–61. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yaffe MB, Schutkowski M, Shen M, Zhou XZ, Stukenberg PT, Rahfeld JU, et al. Sequence-specific and phosphorylation-dependent proline isomerization: a potential mitotic regulatory mechanism. Science. 1997;278:1957–60. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5345.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]