ABSTRACT

Background

Letters of recommendation (LORs) are an important part of applications for residency and fellowship programs. Despite anecdotal use of a “code” in LORs, research on program director (PD) perceptions of the value of these documents is sparse.

Objective

We analyzed PD interpretations of LOR components and discriminated between perceived levels of applicant recommendations.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, descriptive study of pediatrics residency and fellowship PDs. We developed a survey asking PDs to rate 3 aspects of LORs: 13 letter features, 10 applicant abilities, and 11 commonly used phrases, using a 5-point Likert scale. The 11 phrases were grouped using principal component analysis. Mean scores of components were analyzed with repeated-measures analysis of variance. Median Likert score differences between groups were analyzed with Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results

Our survey had a 43% response rate (468 of 1079). “I give my highest recommendation” was rated the most positive phrase, while “showed improvement” was rated the most negative. Principal component analysis generated 3 groups of phrases with moderate to strong correlation with each other. The mean Likert score for each group from the PD rating was calculated. Positive phrases had a mean (SD) of 4.4 (0.4), neutral phrases 3.4 (0.5), and negative phrases 2.6 (0.6). There was a significant difference among all 3 pairs of mean scores (all P < .001).

Conclusions

Commonly used phrases in LORs were interpreted consistently by PDs and influenced their impressions of candidates. Key elements of LORs include distinct phrases depicting different degrees of endorsement.

What was known and gap

Little is known on how program directors interpret commonly used phrases in letters of recommendation for residency and fellowship applicants.

What is new

A study of pediatrics and pediatrics subspecialty program directors found that phrases commonly used in letters influenced their perception of candidates.

Limitations

Low response rate, and a survey that lacked validity evidence may limit generalizability.

Bottom line

Common phrases and the overall quality of the letter writing influenced program directors' interpretation of positive and negative attributes of candidates.

Introduction

Letters of recommendation (LORs) are required for applications to residency and fellowship programs. The literature and the results of the 2016 National Resident Matching Program survey of program directors (PDs) indicated residency and fellowship PDs rated LORs as important when selecting applicants to interview and rank in their programs.1–7 Concerns regarding the LOR as an accurate assessment of applicants were raised as long as 35 years ago,8 with studies showing grade inflation in LORs.9–11 One study reported that less than 2% of candidates were rated using the lowest categories,9 while another demonstrated that 40% of candidates were rated in the top 10% on a global assessment.10

When faculty members write LORs, they walk the fine line between writing an honest letter supporting the applicant and diminishing the credibility of these letters by overselling an average candidate. Letters often are drafted with latent information that requires PDs to decode their meaning.12–14 An article in a previous issue of the Journal of Graduate Medical Education “Viewpoint From a Program Director: They Can't All Walk on Water” characterizes the current state of applications to residency programs as one in which applicants all look the same on paper, yet suggests that faculty with experience can “read between the lines” of LORs.15 Given the notion of the use of “code” in LORs, novice letter writers may not know the code. To date, there is limited research describing this code.

The objectives of this study were to identify (1) the relative importance of selected LOR features (eg, length of letter, academic rank of letter writer); (2) the relative importance of selected applicant attributes (such as work ethic and professionalism); and (3) the perceptions invoked in pediatrics residency and fellowship PDs by phrases commonly used in LORs (eg, “I give my highest recommendation” versus “I recommend”). We also identified areas of agreement or variation among residency and fellowship PDs to characterize the thought process of the reader of the LOR. One aim is to better guide writers to provide a more accurate description of the candidate.

Methods

We conducted a national cross-sectional survey of members of the Association of Pediatric Program Directors, which included 770 fellowship PDs, 198 residency PDs, and 111 associate PDs. We developed a survey instrument that asked respondents to rate the importance of LOR features, applicant abilities, and the magnitude of strength of commonly used LOR phrases.

Before we developed the survey, we reviewed the literature. While we did not find compendia of letter features, applicant attributes, or common phrases, we used the available concepts from the literature describing LORs.14,16–27 Six pediatrics residency and fellowship PDs and members of the intern and fellowship selection committees at 1 institution (each with 10 or more years of experience reviewing letters) created individual lists of specific letter features, applicant abilities, and commonly used phrases. We limited the number of features, abilities, and phrases to those that achieved consensus within the group. We presented the survey to the Association of Pediatric Program Directors Research and Scholarship Task Force, a national panel of experts, for review and further revisions. The final survey was approved by the Task Force in July 2016 and contained 13 letter features, 10 applicant abilities, and 11 phrases (provided as online supplemental material).

Respondents were asked to rate the lists of LOR features and applicant abilities on a 5-point Likert scale (1, not at all important, to 5, very important) and commonly used phrases on a 5-point Likert scale (1, very negative, to 5, very positive). The survey was sent electronically 3 times between July and August 2016. Items receiving a Likert scale rating of 4 or 5 were grouped together as important/positive, while items receiving a Likert scale rating of 1 or 2 were grouped together as not important/negative. For the open-ended question, “Are there other features you consider important in a well-regarded letter that we didn't include in the survey?” the study authors coded the responses into themes, aiming for consensus among the coders.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Mann-Whitney U tests were used to analyze the differences in letter features and abilities between residency and fellowship PDs. The 11 commonly used phrases were grouped using principal component analysis and Varimax rotation. Interitem reliability analysis was generated with Cronbach's alpha. The mean scores of the letter phrases were analyzed with repeated measures analysis of variance. Differences in ratings (of letter features and abilities) between residency and fellowship PDs were analyzed with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Analysis was generated with SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

Results

The survey was sent to 1079 pediatrics PDs and achieved a response rate of 43% (468). Of those who responded, 123 (26%) indicated that they primarily reviewed fellowship applications, 203 (43%) reviewed residency applications, and 141 (30%) reviewed both. For the question, “How important are an applicant's letters of recommendation to you in shaping your overall impression of the quality of the applicant?” 399 respondents (85%) rated them as important, while 418 respondents (89%) indicated they would consider a weaker candidate more favorably with a well-crafted LOR, and 296 (63%) indicated they would consider a strong candidate less favorably if the LOR was poorly crafted.

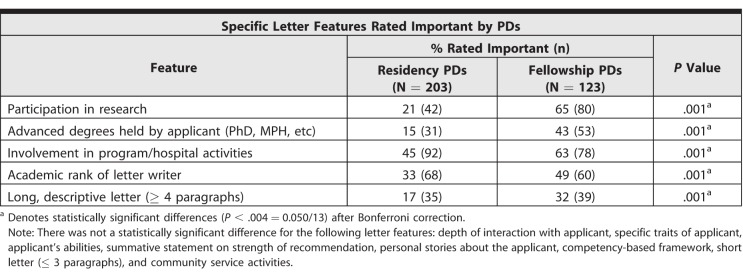

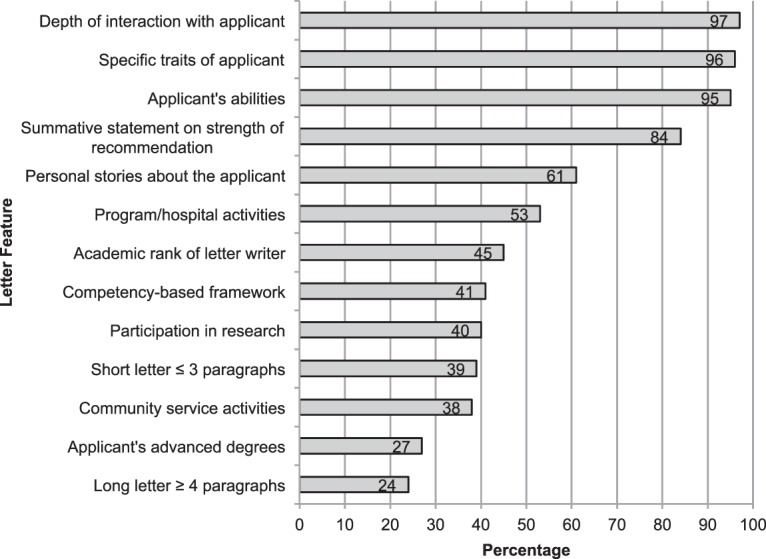

Figure 1 displays the 13 letter features in rank order from highest to lowest rating of importance. Important differences emerged between residency and fellowship PDs, which are reported in Table 1. Highlighting an applicant's participation in research, advanced degrees held by the applicant, his or her involvement in program/hospital activities, the academic rank of the letter writer, and a long letter (4 paragraphs or more) were rated significantly more important by fellowship PDs than they were by residency PDs (all P < .004).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Program Directors Rating Letter Feature Important

Table 1.

Differences Between Residency and Fellowship Program Directors (PDs)

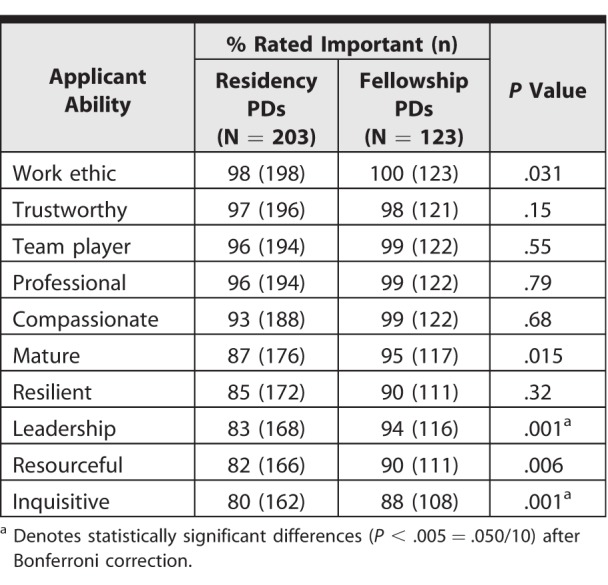

Table 2 reports the 10 applicant abilities and the percentage of residency and fellowship PDs who rated them important in response to the item, “Please rate how important the following abilities are to you in a letter of recommendation when describing an applicant.” Leadership and inquisitiveness were rated significantly more important by fellowship PDs than they were by residency PDs (all P < .005).

Table 2.

Residency and Fellowship Program Director (PD) Ratings of Applicant Abilities

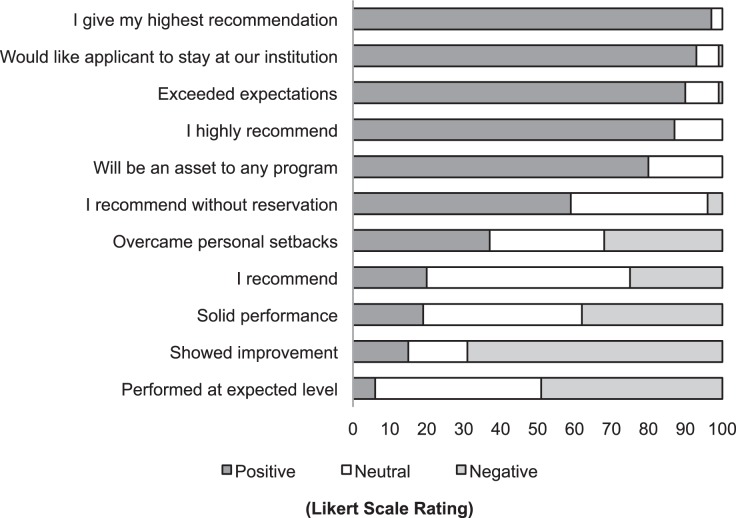

Figure 2 reports the 11 phrases and the percentage of PDs who rated them positive, neutral, or negative on the Likert scale ordered from most to least positive. The phrases “I give my highest recommendation,” “would like the applicant to stay at our institution,” and “exceeded expectations” were interpreted most positively by PDs. The phrases “overcame personal setbacks,” “solid performance,” and “I recommend” were rated more neutral by PDs and had a roughly equal number of respondents rate both positively and negatively. Lastly, the phrases “showed improvement” and “performed at expected level” were rated negatively by PDs.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Program Directors Rating Phrase Positive, Neutral, and Negative

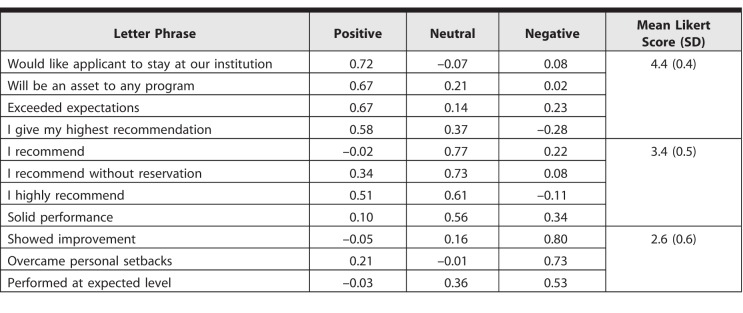

Table 3 reports the results of the principal component analysis, which generated 3 independent groups of phrases with moderate to strong correlation with each other. The phrases “would like the applicant to stay at our institution,” “will be an asset to any program,” “exceeded expectations,” and “I give my highest recommendation” grouped together as positive phrases. If PDs rated 1 of the phrases in this group as positive on the Likert scale, they were likely to rate the other phrases in that group positive as well. This grouping of items was also observed for the neutral and negative groups of phrases. After these groups were identified, we calculated the mean Likert score for each group from the PD rating. The positive phrases had a mean (SD) of 4.4 (0.4), or a positive rating on the Likert scale. The neutral phrases had a mean of 3.4 (0.5) or a near-neutral rating on the Likert scale, and the negative phrases had a mean of 2.6 (0.6) or a more negative rating on the Likert scale. There was a statistically significant difference among the 3 pairs of mean scores (all P < .001). The interitem reliability was alpha = 0.75. The interitem reliability of the positive letter phrases was alpha = 0.64, neutral letter phrases was alpha = 0.70, and negative letter phrases was alpha = 0.58.

Table 3.

Principal Components Analysis of Letter Phrases

For the open-ended question “Are there other features you consider important in a well-regarded letter that we didn't include in the survey?” comments were submitted by 103 of 486 (21%) of the respondents. Themes identified by residency PDs included writing a personal letter (23%, 15 of 66), indicating the tier of the applicant (15%, 10 of 66), commenting on the applicant's clinical reasoning abilities (12%, 8 of 66), commenting on the applicant's communication skills (11%, 7 of 66), the LOR writer's experience with learners (8%, 5 of 66), and the letter coming from a “reputable letter writer” (8%, 5 of 66). Themes identified for fellowship PDs included commenting on the applicant's motivation (16%, 6 of 37), indicating the tier of the applicant (14%, 5 of 37), and other abilities, such as receptive to feedback, adaptable (14%, 5 of 37), reputable letter writer (11%, 4 of 37), and commenting on the applicant's communication skills (8%, 3 of 37).

Discussion

In this national study of pediatrics residency and fellowship PD perceptions of LORs, we found that LORs shape PD impressions of candidates. The results may help identify what residency and fellowship PDs would like to see in LORs and suggest likely interpretations of commonly used phrases.

PDs consider the LOR important, and the quality of the letter influences readers' decisions about the applicant. Although an applicant's class rank, clerkship performance, and board scores are available through the Electronic Residency Application Service, the majority of PDs indicated that an LOR could shift their impression of a candidate, both positively and negatively. In the survey, we used the terms “well-crafted” and “poorly crafted” to acknowledge that an LOR is more than just a collection of letter features, phrases, and descriptions of an applicant's abilities. It is this artful construction of the document that contributes to high-stakes program decisions about the applicant.

The literature contains advice for letter writers, such as specific language and formatting to use in LORs, reviewing the applicant's academic performance, and meeting with them to learn more about them before writing the letter.12,14,16–18,20,24,25 While there were similarities among the perceptions of residency and fellowship PDs regarding LOR features, we also found differences. Writers might take these into account when composing LORs for residency or fellowships.

The results of this study underscore the need for faculty development in letter writing. A survey of internal medicine clerkship directors reported about half had received some guidance on preparing an LOR, and the majority had developed their own letter-writing guidelines.19 It is important for letter writers to be aware of interpretations of LOR phrases identified in this study that influence readers' perceptions. For example, only a minority of PDs rated the phrase “showed improvement” as positive when faculty, PDs, and accrediting bodies expect all residents to improve over the course of their training.

Limitations to this study include that the results may not reflect all pediatrics PD perceptions, with a response rate under 50%, and may not generalize to other specialties. The survey had no validity evidence, and questions may have been interpreted by respondents differently than intended. Further study is needed to understand whether LOR descriptions of candidates affect their ranking in the program. The responses to the open-ended question, “Are there other features you consider important in a well-regarded letter not included in this survey?” suggest that other attributes of LORs may be the focus of future surveys.

Conclusion

Pediatrics residency and fellowship PDs report that LORs influence their impressions of candidates both positively and negatively. Key elements of LORs include distinct phrases depicting different degrees of endorsement of a candidate. There were some key differences between LOR preferences among residency and fellowship PDs.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Morgenstern BZ., Zalneraitis E., Slavin S. Improving the letter of recommendation for pediatric residency applicants: an idea whose time has come? J Pediatr. 2003; 143 2: 143– 144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeLisa JA., Jain SS., Campagnolo DI. Factors used by physical medicine and rehabilitation residency training directors to select their residents. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1994; 73 3: 152– 156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ross CA., Leichner P. Criteria for selecting residents: a reassessment. Can J Psychiatry. 1984; 29 8: 681– 686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Crane JT., Ferraro CM. Selection criteria for emergency medicine residency applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2000; 7 1: 54– 60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wagoner NE., Gray GT. Report on a survey of program directors regarding selection factors in graduate medical education. J Med Educ. 1979; 54 6: 445– 452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2016 main residency match. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Main-Match-Results-and-Data-2016.pdf. Accessed February 21, 2018.

- 7. National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2016 NRMP Program Director Survey Specialties Matching Service. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2016-PD-Survey-Report-SMS.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2018.

- 8. Friedman RB. Fantasy land. N Engl J Med. 1983; 308 11: 651– 653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grall KH., Hiller KM., Stoneking LR. Analysis of the evaluative components of the standard letter of recommendation (SLOR) in emergency medicine. West J Emerg Med. 2014; 15 4: 419– 423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hegarty CB., Lane DR., Love JN., et al. Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors standardized letter of recommendation writers' questionnaire. J Grad Med Educ. 2014; 6 2: 301– 306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Love JN., DeIorio NM., Ronan-Bentle S., et al. Characterization of the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors' standardized letter of recommendation in 2011–2012. Acad Emerg Med. 2013; 20 9: 926– 932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Larkin GL., Marco CA. Ethics seminars: beyond authorship requirements—ethical considerations in writing letters of recommendation. Acad Emerg Med. 2001; 8 1: 70– 73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Plumeri PA. The letter of recommendation. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985; 7 2: 183– 185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wright SM., Ziegelstein RC. Writing more informative letters of reference. J Gen Intern Med. 2004; 19(5, pt 2):588–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15. Puscas L. Viewpoint from a program director: they can't all walk on water. J Grad Med Educ. 2016; 8 3: 314– 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prager JD., Myer CM., Pensak ML. Improving the letter of recommendation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010; 143 3: 327– 330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McBride AB., Lovejoy KB. Requesting and writing effective letters of recommendation: some guidelines for candidates and sponsors. J Nurs Educ. 1995; 34 2: 95– 96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelley KW., Liles AM., Starr JA. Writing letters of recommendation: where should you start? Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2012; 69 7: 563– 565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. DeZee KJ., Thomas MR., Mintz M., et al. Letters of recommendation: rating, writing, and reading by clerkship directors of internal medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2009; 21 2: 153– 158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Layde JB. Writing effective letters of recommendation. : Roberts LW. The Academic Medicine Handbook: A Guide to Achievement and Fulfillment for Academic Faculty. New York, NY: Springer; 2013: 209– 216. [Google Scholar]

- 21. DeZee KJ., Magee CD., Rickards G., et al. What aspects of letters of recommendation predict performance in medical school? findings from one institution. Acad Med. 2014; 89 10: 1408– 1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Beskind DL., Hiller KM., Stolz U., et al. Does the experience of the writer affect the evaluative components on the standardized letter of recommendation in emergency medicine? J Emerg Med. 2014; 46 4: 544– 550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Holmes AV., Peltier CB., Hanson JL., et al. Writing medical student and resident performance evaluations: beyond “performed as expected.” Pediatr. 2014; 133 5: 766– 768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts LW., Termuehlen G. (Honest) letters of recommendation. Acad Psychiatr. 2013; 37 1: 55– 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fortune JB. The content and value of letters of recommendation in the resident candidate evaluative process. Curr Surg. 2002; 59 1: 79– 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pangaro L. A new vocabulary and other innovations for improving descriptive in-training evaluations. Acad Med. 1999; 74 11: 1203– 1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaffe S. Painlessly write the painful truth. Scientist. 2002; 16 4: 44– 45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.