Abstract

Background

Hospice provides integrative palliative care for advance-staged hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients, but hospice utilization in HCC patients in the United States is not clearly understood.

Aims

We examined hospice use and subsequent clinical course in advance-staged HCC patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study on a national, Veterans Affairs cohort with stage C or D HCC. We evaluated demographics, clinical factors, treatment, and clinical course in relation to hospice use.

Results

We identified 814 patients with advanced HCC, of whom 597 (73.3%) used hospice. Oncologist management consistently predicted hospice use, irrespective of HCC treatment (no treatment: OR = 2.25 (1.18–4.3), treatment: OR = 1.80 (1.10–2.95)). Among patients who received HCC treatment, hospice users were less likely to have insurance beyond VA benefits (47.2% vs. 60.0%, p = 0.01). Among patients without HCC treatment, hospice users were older (62.2 [17.2] vs. 60.2 [14.0] years, p = 0.05), white (62.1% vs. 52.9%, p = 0.01), resided in the southern United States (39.5% vs. 31.8%, p = 0.05), and had a performance score ≥ 3 (41.9% vs. 31.8%, p = 0.01). The median time from hospice entry to death or end of study was 1.05 [2.96] months for stage C and 0.53 [1.18] months for stage D patients.

Conclusions

26.7% advance-staged HCC patients never entered hospice, representing potential missed opportunities for improving end-of-life care. Age, race, location, performance, insurance, and managing specialty can predict hospice use. Differences in managing specialty and short-term hospice use suggest that interventions to optimize early palliative care are necessary.

Keywords: hospice, palliative care, hepatocellular carcinoma, veteran

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common cancers worldwide and the fastest-rising cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States [1–4]. Each year, approximately 20,000 new cases are diagnosed in the United States, with a five-year survival rate below 20%. Notably, approximately 60% of patients with HCC are diagnosed with advance-staged diseases (i.e., Barcelona clinic liver cancer staging (BCLC) stages C and D) [2], where the options of effective HCC-directed treatments are very limited.

Palliative care, defined as medical care that focuses on relieving mental distress and physical pain for patients who are not eligible or refuse cancer-directed treatment, is increasingly initiated at the diagnosis of advance-staged cancers to provide dynamic, patient-centered care throughout the course of disease. In the Veteran Affairs (VA) healthcare system, hospice is a service outside of the medical oncology specialty that can provide services beyond palliative clinical care for veterans who 1) are diagnosed with a life-limiting illness (defined as a disease or condition that is expected to significantly shorten life span); 2) have treatment goals focused on comfort rather than cure; 3) have a life expectancy, deemed by a VA physician, to be 6 months or less if the disease runs its normal course; and 4) accepts hospice care.

Previous studies in patients with non-HCC cancers have shown that early palliative care interventions, including hospice, in aggressive or late-staged cancers improve patient quality of life and reduce overall healthcare costs [5, 6]. Recent studies show that palliative care may be associated with lower healthcare costs in patients with end-stage liver disease and cirrhosis, although early and quality palliative intervention in these patients are still inadequate [7–9]. Further, few studies have examined the utilization and outcomes of hospice use in patients with advance-staged HCC.

We report our findings from a national, retrospective cohort of advance-staged HCC patients who were diagnosed in the national Veteran Affairs (VA) healthcare system. Our study aims were to examine the utilization of hospice, identify determinants of hospice use, and compare the clinical course between hospice and non-hospice users.

METHODS

Data Sources

We obtained data from VA administrative data files combined with manual review of electronic medical records (EMR). The administrative data included Vital Status File and the Medical SAS (MedSAS) Outpatient and Inpatient files. The MedSAS files contain patient demographic data, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses and Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. We determined the date of death from the Vital Status file, which uses information found in the VA MedSAS Inpatient file, Beneficiary Identification & Records Locator System Death File, Medicare Vital Status file, and Social Security Administration death file to select the most accurate date of death. For EMR reviews, we used the VA Compensation and Pension Records Interchange (CAPRI) and Veterans Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA) systems from nationwide VAs. Trained abstractors manually reviewed EMRs using a structured data abstraction, including HCC clinical characteristics, patient characteristics, treatment information, and hospice use.

Study Population

Using VA administrative databases, we identified a national cohort of veterans with HCC, newly diagnosed between October 1, 2004 and September 30, 2011. Only patients with an ICD-9 code 155.0 (malignant neoplasm of liver) in the absence of 155.1 (intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma) were selected. We manually reviewed EMRs for all cases to confirm HCC diagnosis and ascertain staging. Further details describing the study cohort were published previously [10]. For this study, we limited our cohort to patients with BCLC stage C or D at the time of diagnosis.

We collected information on patient performance status, Child-Pugh score, HCC tumor size and number, and portal vein involvement [11]. BCLC stage C was defined by large multinodular tumors with impaired ECOG performance status (PS = 1–2) or the presence of portal invasion and/or extrahepatic spread. BCLC stage D was defined by poor performing terminal illness (PS > 2) or Child-Pugh class C.

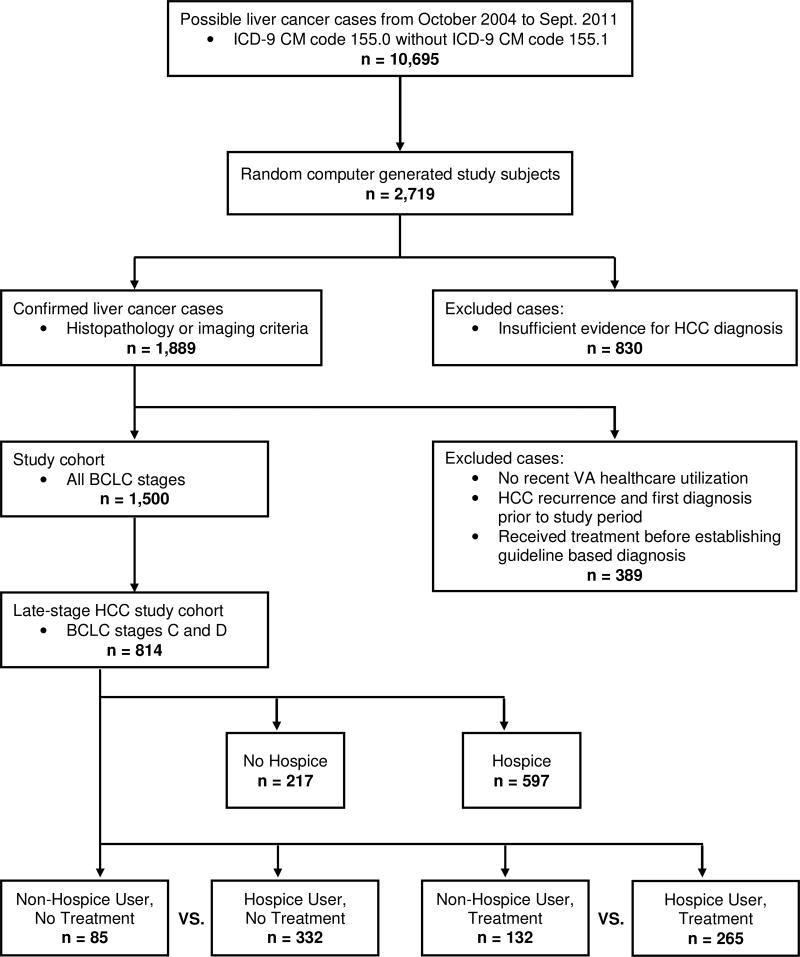

Hospice Utilization

We categorized patients as hospice or non-hospice users based on documented physician referral to hospice. Hospice is part of the VHA Standard Medical Benefits and a service provided by all VA’s Geriatrics and Extended Care Services department. VA’s alliance with the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization allows veteran’s access to 3526 nationwide hospice care facilities outside of the VA, ensuring all veterans who need hospice services can have access. We included all types of hospice care within the VA healthcare system, including inpatient and outpatient hospice care. Having only a clinic visit for palliative clinical care did not constitute hospice use. Hospice use had to be explicitly documented. Timing of hospice use may depend on receipt of HCC treatment; therefore, we examined hospice use stratified by HCC treatment status. Our final cohort was separated into four groups: 1) Non-Hospice Users, No HCC Treatment, 2) Hospice Users, No HCC Treatment, 3) Non-Hospice Users, HCC Treatment, or 4) Hospice Users, HCC Treatment. The Hospice Users, No HCC treatment group included patients who did not receive HCC treatment, and were referred to hospice within 30 days of HCC diagnosis, whereas the Hospice Users, Treatment group entered hospice only after completion or discontinuation of HCC treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data abstraction methods to arrive at study cohorts. Only late-staged (BCLC stage C and D) HCC patients were included.

Patient Characteristics

We ascertained demographic information (age, gender, race, insurance information, geographic location, rural residence, transplant center, total hospital beds, and year of HCC diagnosis) as well as clinical characteristics such as HCC stage (BCLC stage), etiology (HCV, HBV, alcoholic liver disease), severity of liver disease (Child-Pugh score, MELD score), performance score (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, ECOG score), co-morbidities (Deyo score), and HCC medical managing specialties (oncology, gastroenterology/hepatology, others) from reviews of EMR. Presence of cirrhosis was determined by suggestive liver biopsy findings any time prior to HCC diagnosis, radiographic imaging, or two of three abnormal laboratory values within the 6 months prior to or 4 weeks after HCC diagnosis was made (albumin <3.0 g/dL, platelets <200,000/mL, or INR >1.1). Patients with ECOG 0–2 were classified as having “good” performance status, whereas those with ECOG ≥ 3 had “poor” performance status. HCC characteristics such as multinodular or metastatic disease and size of largest tumor lesion were determined from liver imaging. We also extracted information on HCC managing specialties and year of HCC diagnosis. Survival time was defined as time from HCC diagnosis to death or end of study follow-up (June 1, 2013). The study protocol, including an informed consent given to all subjects, was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baylor College of Medicine (H-28264).

Statistical Analysis

Using Pearson’s chi-square test, we compared demographic and clinical factors between patients who used hospice and those who did not. The comparison of hospice groups was stratified by treatment status. We conducted multiple regression stratified by treatment status to identify factors that independently predicted hospice use. In these models, we adjusted for age, race, geographic region, stage, HBV status, MELD, ECOG PS, and managing specialty in the No HCC-Treatment groups; and for stage, insurance status, MELD, ECOG PS and managing specialty in the Yes HCC-Treatment group. These variables were selected either because of their importance in the disease course of HCC or based on significant results from Pearson’s chi-square analysis with respect to treatment status.

Kaplan-Meier analysis (log rank test) was used to compare the cumulative survival of HCC patients with and without hospice utilization stratified by HCC treatment. All statistical analyses were done using Statistical Analysis System (SAS, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In VA hospitals nationwide, 10,695 patients had a suspected diagnosis of HCC between October 1, 2004 to September 30, 2011 based on the presence of ICD-9 CM code 155.0 and in the absence of ICD-9 CM code 155.1 [10]. We reviewed EMR for a random sample of patients until we reach 1,500 patients with verified HCC [10]. For this analysis, the study cohort included 814 patients with BCLC stage C (n = 564, 69.3%) or D (n = 250, 30.7%) at the time of HCC diagnosis (Figure 1). The median age of the study cohort at time of HCC diagnosis was 61.2 [Interquartile range (IQR) 13.4] years. The majority were male and 59% were white. The overall survival during study period was 4.4% for stage C and 2.8% for stage D patients.

A total number of 597 (73.3%) of 814 patients used hospice; 405 (67.8%) of hospice users had stage C HCC and 192 (32.2%) had stage D HCC. Among those who used hospice, 332 (55.6%) did not receive any HCC targeted treatment (Table 2) and 265 (44.4%) received HCC treatment before entering hospice. HCC targeted, loco-regional therapies (n = 197 (59.6%)) and sorafenib (n = 184 (46.3%)) were the most common treatments received (Table 1). Many also received curative intent therapy, including transplant (n = 22 (5.5%)), surgical resection (n = 23 (5.8%)), or ablation (n = 53 (13.4%)) (Table 1). Of the 22 patients who underwent transplantation, tumors were discovered during transplant surgery in 4 patients; other transplanted patients received downstaging treatments before surgery. Among those who did not receive HCC treatments, 62.6% were not eligible for HCC treatments due to liver disease severity, poor performance status, or the presence of co-morbidities, 22.1% opted not to receive treatment, 5.9% died before scheduled treatment, 5.6% were due to other scheduling issues, and 3.8% left the VA system.

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic and clinical characteristics among late stage HCC patients (BCLC stage C and D) who used hospice to those who did not, by receipt of treatment. (n = 814)

| Non-Hospice User, No Treatment n = 85 (%) |

Hospice User, No Treatment n = 332 (%) |

p | Non-Hospice User, Treatment n = 132 (%) |

Hospice User, Treatment n = 265 (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||||

| Age (median, IQR) | 60.2 (14.0) | 62.2 (17.2) | 0.05 | 61.2 (10.0) | 61.0 (12.0) | 0.6 |

| Gender: Male | 84 (98.8) | 331 (99.7) | 0.3 | 132 (100) | 265 (100) | |

| Race | 0.01 | 0.8 | ||||

| White | 45 (52.9) | 206 (62.1) | 77 (58.3) | 164 (61.9) | ||

| Black | 27 (31.8) | 91 (27.4) | 32 (24.2) | 62 (23.4) | ||

| Hispanic | 7 (8.2) | 31 (9.3) | 21 (15.9) | 34 (12.8) | ||

| Other | 6 (7.1) | 4 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) | 5 (1.9) | ||

| Additional Insurance | 44 (51.8) | 159 (47.9) | 0.5 | 80 (60.6) | 125 (47.2) | 0.01 |

| Geographic Region | 0.05 | 0.5 | ||||

| Central | 10 (11.8) | 65 (19.6) | 17 (12.9) | 47 (17.7) | ||

| East | 25 (29.4) | 81 (24.4) | 35 (26.5) | 59 (22.3) | ||

| South | 27 (31.8) | 131 (39.5) | 48 (36.4) | 88 (33.2) | ||

| West | 23 (27.1) | 55 (16.6) | 32 (24.2) | 71 (26.8) | ||

| Rural Residence | 0.5 | 0.9 | ||||

| No | 63 (74.1) | 257 (77.4) | 105 (79.6) | 212 (80.0) | ||

| Yes | 22 (25.9) | 75 (22.6) | 27 (20.5) | 53 (20.0) | ||

| Transplant Center | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||

| No | 74 (87.1) | 288 (87.0) | 116 (87.9) | 232 (87.9) | ||

| Yes | 11 (12.9) | 43 (13.0) | 16 (12.1) | 32 (12.1) | ||

| Total Hospital Beds (mean, SD) | 7971.3 (8329.0) | 8394.9 (8306.8) | 0.7 | 8900 (9496.6) | 7747.2 (7217.6) | 0.2 |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||||

| BLCL Stage | 0.9 | 0.5 | ||||

| Stage C | 51 (60.0) | 196 (59.0) | 108 (81.8) | 209 (78.9) | ||

| Stage D | 34 (40.0) | 136 (41.0) | 24 (18.2) | 56 (21.1) | ||

| HCC Etiology | ||||||

| HBV | 9 (10.6) | 14 (4.2) | 0.02 | 9 (6.8) | 11 (4.2) | 0.3 |

| HCV | 51 (60.0) | 197 (59.3) | 0.9 | 91 (68.9) | 177 (66.8) | 0.7 |

| Alcoholic Liver Dis. | 70 (82.4) | 251 (75.6) | 0.2 | 114 (86.4) | 213 (80.4) | 0.1 |

| MELD | 0.9 | 0.3 | ||||

| <10 | 28 (32.9) | 99 (29.8) | 54 (40.9) | 99 (37.4) | ||

| 10–19 | 44 (51.8) | 176 (53.0) | 58 (43.9) | 138 (52.1) | ||

| 20+ | 8 (9.4) | 38 (11.5) | 10 (7.6) | 11 (4.2) | ||

| Unknown | 5 (5.88) | 19 (5.7) | 10 (7.6) | 17 (6.4) | ||

| ECOG PS | 0.01 | 0.2 | ||||

| Poor (≥3) | 27 (31.8) | 137 (41.9) | 13 (10.1) | 37 (14.2) | ||

| Good (0–2) | 58 (68.2) | 190 (58.1) | 116 (89.9) | 223 (85.8) | ||

| Charlson/Deyo Score | 1.0 | 0.26 | ||||

| 0 | 23 (27.1) | 88 (26.5) | 25 (18.9) | 70 (26.4) | ||

| 1–2 | 27 (31.8) | 108 (32.5) | 38 (28.8) | 71 (26.8) | ||

| ≥3 | 35 (41.2) | 136 (41.0) | 69 (52.3) | 124 (46.8) | ||

| Managing Specialty | 0.009 | .0003 | ||||

| Oncology | 41 (50.6) | 223 (67.2) | 59 (44.7) | 167 (63.0) | ||

| Gastroenterology/Hepatology | 24 (28.2) | 52 (15.7) | 46 (34.9) | 75 (28.3) | ||

| Others* | 18 (21.2) | 57 (17.2) | 27 (20.5) | 23 (8.7) | ||

| Year of HCC Diagnosis | 0.7 | 0.9 | ||||

| 2004–2007 | 49 (57.7) | 185 (55.7) | 49 (37.1) | 96 (36.2) | ||

| 2008–2011 | 36 (42.4) | 147 (44.3) | 83 (62.9) | 169 (63.8) | ||

Others include tumor board, transplant, surgery, surgery, radiation oncology, primary care, and others

Table 1.

Treatment received by advanced stage HCC patients (BCLC stage C and D) grouped by stage and hospice status#. (n = 397)

| Stage C | Stage D | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hospice User n = 108 (%) |

Hospice User n = 209 (%) |

Non-Hospice User n = 24 (%) |

Hospice User n = 56 (%) |

Total n = 397 (%) |

|

| Curative intent | |||||

| Transplant | 8 (7.4) | 1 (0.5) | 9 (37.5) | 4 (7.1) | 22 (5.5) |

| Surgery | 11 (10.2) | 11 (5.3) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 23 (5.8) |

| Ablation* | 26 (24.1) | 14 (12.0) | 5 (20.8) | 8 (14.3) | 53 (13.4) |

| Non-curative intent | |||||

| Liver directed** | 60 (55.6) | 98 (46.9) | 11 (45.8) | 28 (50.0) | 197 (49.6) |

| Systemic - Sorafenib | 33 (30.6) | 121 (57.9) | 3 (12.5) | 27 (48.2) | 184 (46.3) |

| Systemic - others*** | 10 (9.3) | 27 (13.0) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (3.6) | 42 (10.6) |

Patient may have received more than one treatment category; therefore, the total treatment count may exceed the cohort number.

Ablation: Radiofrequency ablation, Ethanol ablation, Microwave ablation

Liver directed therapy: Transarterial Embolization or Chemoembolization, Y-90, Radioembolization, Radioimmunotherapy, Cryotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy - others: Dexorubicin (Doxil, Adriamycin), Bevacizumab (Avastin), Capecitabine (Xeolda), Gemitabine (Gemzar), Other Chemo Agent, and Clinical Trials

The median duration from hospice entry to death or end of study period was 1.05 [IQR 2.96] months for stage C patients and 0.53 [IQR 1.18] months for stage D patients. Approximately 26.7% patients never used hospice during the study period, of whom 44.7% died before hospice was offered. Other reasons for not using hospice included leaving the VA healthcare system (18.4%), continuing to seek HCC treatment (16.0%), hospice not offered by providers (8.7%), hospice not wanted by patient or family (7.8%), and unknown (4.4%).

Determinants of Hospice Utilization

Among 417 patients who did not receive HCC treatment, patients who utilized hospice were older (median age 62.2 [IQR 17.2] years vs. 60.2 [IQR 14.0] years, p = 0.05), less likely to be HBV positive (4.2% vs. 10.6%, p = 0.02), and more likely to be white (62.1% vs. 52.9%, p = 0.01), with ECOG performance score ≥ 3 (41.9% vs. 31.8%, p = 0.01), residing in southern United States (39.5% vs. 31.8%, p = 0.05), and managed by an oncologist (67.2% vs. 50.7%, p = 0.009) than patients who did not utilize hospice (Table 2).

Among 397 patients who received HCC treatments before entering hospice, hospice use was more likely in the presence of management by an oncologist (63.0% vs. 44.7%, p < 0.0003) and absence of additional insurance outside of VA benefits (47.2% vs. 60.0%, p < 0.01) (Table 2). We did not observe significant changes in hospice use over the study period (2004–2011) regardless of stage or treatment status (Table 2).

Notably, important variables differentiating the VA institution such as rural residence (% patients residing in a rural area), transplant center (% patients being treated in a hospital with a transplant center), and total hospital beds (the number of hospital beds where patient is being treated) are not significantly different among hospice and non-hospice users.

In multiple regression models examining determinants of hospice use, the managing specialty consistently predicted hospice use. Among patients who did not receive HCC treatments, the odds of using hospice were higher in patients managed by an oncologist than those who did not see an oncologist (OR = 2.28 (95% CI 1.21–4.67) and those with a poor ECOG performance score (OR = 2.04 (95% CI 1.02–4.06)) (Table 3). Among those who received HCC treatments, management by an oncologist was again associated with higher odds (OR = 2.12 (95% CI 1.27–3.54)) of hospice use, and having non-VA insurance was associated with lower odds (OR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.39–0.97)).

Table 3.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of the association of demographic and clinical characteristics and hospice use in late stage HCC patients (BCLC stage C and D), with respect to treatment.

| No Treatment | Treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)* |

Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)** |

||

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (0.99–1.04) | Additional Insurance | |

| Race | Yes | 0.62 (0.39–0.99) | |

| White | REF | No | REF |

| Other | 0.58 (0.33–1.04) | Geographic Region | |

| Geographic Region | Central | 1.54 (0.74–3.18) | |

| Central | 1.16 (0.49–2.72) | East | 1.21 (0.64–2.31) |

| East | 0.52 (0.26–1.04) | West | 1.28 (0.70–2.36) |

| West | 0.43 (0.21–0.90) | South | REF |

| South | REF | Rural Residence | |

| Rural Residence | No | 1.20 (0.66–2.18) | |

| No | 1.38 (0.73–2.61) | Yes | REF |

| Yes | REF | Transplant Center | |

| Transplant Center | No | REF | |

| No | REF | Yes | 1.09 (0.54–2.20) |

| Yes | 0.94 (0.43–2.03) | Total Hospital Beds | 1.08 (0.54–2.20) |

| Total Hospital Beds | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | BLCL Stage | |

| BLCL Stage | Stage C | 0.75 (0.37–1.54) | |

| Stage C | 1.39 (0.78–2.87) | Stage D | REF |

| Stage D | REF | MELD | |

| HCC Etiology: HBV | <10 | REF | |

| Yes | 0.49 (0.18–1.30) | 10–19 | 1.28 (0.76–2.15) |

| No | REF | 20+ | 0.61 (0.21–1.79) |

| MELD | Unknown | 1.22 (0.44–3.41) | |

| <10 | REF | ECOG PS | |

| 10–19 | 1.23 (0.66–2.31) | Poor (≥3) | 1.14 (0.50–2.62) |

| 20+ | 2.09 (0.68–6.43) | Good (0–2) | REF |

| Unknown | 0.88 (0.26–3.01) | Managing Specialty | |

| ECOG PS | Oncology | 2.12 (1.27–3.54) | |

| Poor (≥3) | 2.04 (1.02–4.06) | Gastroenterology/Hepatology | REF |

| Good (0–2) | REF | Others*** | 0.49 (0.23–1.04) |

| Managing Specialty | |||

| Oncology | 2.38 (1.21–4.67) | ||

| Gastroenterology/Hepatology | REF | ||

| Others*** | 1.39 (0.61–3.15) | ||

Odds ratio for the No-Treatment group adjusted for age, race, geographic region, rural residence, transplant center, stage, HBV status, MELD, ECOG PS, and referral specialty.

Odds ratio for the Yes-Treatment group adjusted for geographic region, rural residence, transplant center, stage, insurance status, MELD, ECOG PS and referral specialty.

Others include tumor board, transplant, surgery, surgery, radiation oncology, primary care, and others

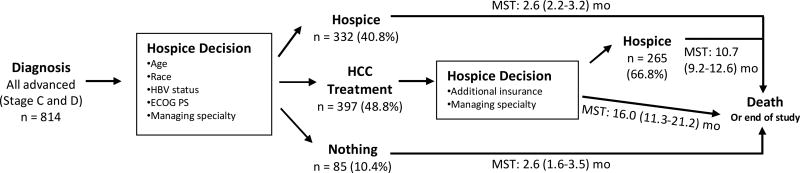

Clinical Course

After HCC diagnosis, 40.8% of patients entered hospice directly after HCC diagnosis and remained in hospice until death or end of study period. The median survival time of this group was 2.6 (95% CI 2.2–3.2) months after diagnosis. 10.4% of patients did not enter hospice nor receive HCC treatment; these patients also had median survival 2.6 (95% CI 1.6–3.5) months.

Patients who received HCC-specific treatment had a longer median survival time, ranging from 10.7 to 16.0 months after diagnosis (Figure 2). Those who never entered hospice had a median survival of 16.0 (95% CI 11.3–21.2) months (Figure 2). Those who eventually entered hospice (n = 265 (66.8%)) following HCC-specific treatment had a median survival time of 10.7 (95% CI 9.2–12.6) months. However, with time, the overall survival of the hospice users post HCC treatment approached those who did not receive HCC treatment, and there was no statistically significant difference by approximately 48 months of follow up (Supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Clinical course of late stage HCC patients (stage C and D) in regards to hospice use.

*MST: Median Survival Time (95% CI)

DISCUSSION

In this national cohort of patients with newly diagnosed HCC, we found that only 40.8% of patients with advanced HCC (BCLC Stages C or D) entered hospice directly after diagnosis, and an additional 32.6% of patients entered hospice after receiving HCC directed therapy. Older, non-white patients, residing in the Southern United States with absence of non-VA healthcare insurance were most likely to use VA hospice. Patients managed by oncologists, compared to other specialists, were also significantly more likely to use hospice, regardless of HCC treatment status. Patients with better performance status were more likely to receive HCC treatments and less likely to enter hospice. Survival was similar between those who did or did not enter hospice without HCC treatment. Patients who received HCC treatment had a longer survival, but those who entered hospice after receiving HCC treatment deteriorated and approached the survival of patients who did not receive HCC treatment.

We observed that 217 (26.7%) of patients with advance-staged HCC never used hospice services; 194 (89.4%) of whom died without hospice. This finding suggests a potential underutilization of hospice and other palliative care and a missed opportunity for improving the quality of end-of-life care for a disease with poor survival [8, 12]. Among these patients, we found a relatively high percentage of patients (48.8%) received HCC treatment. This was especially more likely among patients with healthcare coverage outside of the VA. Current practice guidelines for patients with HCC treatment recommend sorafenib in Stage C and best supportive care in Stage D HCC. Treatment options, such as resection and ablation, are not recommended in these patients due to the unproven efficacy, negative impact on quality of life and high cost. In our analysis, 17.8% advanced HCC cohort received curative intent treatment (Table 1). Thus, considerations must be given to quality of life, patient discomfort, and the significant healthcare costs associated with unnecessary treatment.

We found a subgroup of patients with advanced HCC who received HCC treatment had relatively high median survival time. This group initially did well as evidenced by a high median survival time, but their condition rapidly declined and hospice was utilized. In this group, the duration of hospice use was very short (< one month). Therefore, it was likely that hospice was utilized in many patients only at the very end of life when all other options had been exhausted and death was imminent. Short-term hospice use does not allow the range of hospice services to be fully utilized. Previous studies showed that only early palliative intervention, including hospice, can improve patient comfort, lower healthcare costs, and increase survival [5–7]. Thus, at least in some patients, aggressive treatment may lead to a short-term improvement in survival but little long-term benefit.

The demographic determinants of hospice shown in this study are consistent with studies in other cancers that found race and social environment play an important role in choosing hospice care [13, 14]. Further, we suspect that significant barriers to use hospice and other palliative care for HCC still exist among providers of varying specialties [15, 16]. Further studies are needed to better understand obstacles facing providers. Identifying strategies for communicating with patients and their families about hospice services may also be beneficial. These interventions could improve quality of life and reduce unnecessary costs associated with aggressive but ineffective treatment.

This study was limited to those who received care at VA facilities. For patients who received treatment for HCC at the VA, we estimate that a small proportion of patients (less than 10%) sought subsequent treatment outside of the VA. It is possible that these patients also received hospice services that we could not capture. However, given the low proportion of patients in our cohort who received non-VA services, we do not believe that our findings would have been significantly impacted. In addition, previous studies have shown that military and non-military populations with cancer use hospice in a similar manner [17]. Our data show that additional insurance outside of VA benefits is an important determinant of hospice use but we did not have information on hospice outside of the VA system. We also identified a small number of patients in our cohort who received liver transplant or resection, which would not be appropriate for patients with advanced stage HCC. We re-reviewed these cases to confirm their stage at diagnosis and found that these cases were correctly staged and treatment was received. Receipt of liver transplant or resection resulted from two scenarios: 1) Patients who were initially diagnosed at stage C received non-curative intent therapies and then were re-staged to stage B after treatment. After restaging, they were eligible to receive transplant or resection; or 2) Patients with additional insurance went outside of the VA to receive more aggressive treatment. Although these cases were unusual, our data were accurate. Given the small number of patients who had these unusual circumstances, we do not think these patients significantly impacted our overall findings. Lastly, we obtained the information on hospice use from the VA EMR rather than directly from patients, families, or hospice programs, therefore having a possibility of misclassification.

In conclusion, we found that 73.3% of patients with advanced HCC utilized hospice at some point following their HCC diagnosis. We identified age, race, geographic location, performance, insurance, and managing specialty as important determinants of hospice use in advance HCC patients. Many patients were not referred to hospice until late in their disease thereby providing little benefit to the patient. Oncologists were most likely to refer patients to hospice. We believe that further study and targeted interventions are required to improve the use and outcomes of hospice in HCC.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of late stage HCC patients (BCLC stage C and D) grouped by hospice use and treatment status.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA160738; PI, J. Davila), and the facilities and resources Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP

WY Zou designed the study, acquired, analyzed, and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. HB El-Serag and JA Davila conceptualized and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript. YH Sada, SL Temple, and S. Sansgiry acquired, analyzed and interpreted the data. F Kanwal analyzed and interpreted the data and provided critical revision for the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, Gores G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. Epub 2016/05/10. PubMed PMID: 27158749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet (London, England) 2015;385(9963):117–71. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61682-2. Epub 2014/12/23. PubMed PMID: 25530442; PMCID: PMC4340604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(12):1118–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. Epub 2011/10/14. PubMed PMID: 21992124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 1999;340(10):745–50. doi: 10.1056/nejm199903113401001. Epub 1999/03/11. PubMed PMID: 10072408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, Dahlin CM, Blinderman CD, Jacobsen J, Pirl WF, Billings JA, Lynch TJ. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2010;363(8):733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. Epub 2010/09/08. PubMed PMID: 20818875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, Moore M, Rydall A, Rodin G, Tannock I, Donner A, Lo C. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 2014;383(9930):1721–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62416-2. Epub 2014/02/25. PubMed PMID: 24559581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel AA, Walling AM, May FP, Saab S, Wenger N. Palliative Care and Health Care Utilization for Patients With End-Stage Liver Disease at the End of Life. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.01.030. Epub 2017/02/10. PubMed PMID: 28179192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, van Zanten SV, Tandon P, Meeberg G, Karvellas CJ. Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014;12(4):692–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.027. Epub 2013/08/28. PubMed PMID: 23978345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly SG, Campbell TC, Hillman L, Said A, Lucey MR, Agarwal PD. The Utilization of Palliative Care Services in Patients with Cirrhosis who have been Denied Liver Transplantation: A Single Center Retrospective Review. Annals of hepatology. 2017;16(3):395–401. doi: 10.5604/16652681.1235482. Epub 2017/04/21. PubMed PMID: 28425409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davila JA, Weston A, Smalley W, El-Serag HB. Utilization of screening for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2007;41(8):777–82. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180381560. Epub 2007/08/19. PubMed PMID: 17700427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet (London, England) 2012;379(9822):1245–55. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61347-0. Epub 2012/02/23. PubMed PMID: 22353262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathpalia P, Smith A, Lai JC. Underutilization of palliative care services in the liver transplant population. World journal of transplantation. 2016;6(3):594–8. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v6.i3.594. Epub 2016/09/30. PubMed PMID: 27683638; PMCID: PMC5036129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Payne R, Tulsky JA. Race and residence: intercounty variation in black-white differences in hospice use. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2013;46(5):681–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ngo-Metzger Q, McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Davis RB, Li FP, Phillips RS. Older Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders dying of cancer use hospice less frequently than older white patients. The American journal of medicine. 2003;115(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00258-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanders BS, Burkett TL, Dickinson GE, Tournier RE. Hospice referral decisions: The role of physicians. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2004;21(3):196–202. doi: 10.1177/104990910402100308. PubMed PMID: 15188919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spencer KL, Mrig EH, Matlock DD, Kessler ER. A Qualitative Investigation of Cross-domain Influences on Medical Decision Making and the Importance of Social Context for Understanding Barriers to Hospice Use. Journal of Applied Social Science. 2017;11(1):48–59. doi: 10.1177/1936724417692377. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wachterman MW, Lipsitz SR, Simon SR, Lorenz KA, Keating NL. Patterns of Hospice Care Among Military Veterans and Non-Veterans. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2014;48(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of late stage HCC patients (BCLC stage C and D) grouped by hospice use and treatment status.