A transgenic mouse reveals real-time dynamics of transcription and transport of endogenous Arc mRNA in live neurons.

Abstract

Localized translation plays a crucial role in synaptic plasticity and memory consolidation. However, it has not been possible to follow the dynamics of memory-associated mRNAs in living neurons in response to neuronal activity in real time. We have generated a novel mouse model where the endogenous Arc/Arg3.1 gene is tagged in its 3′ untranslated region with stem-loops that bind a bacteriophage PP7 coat protein (PCP), allowing visualization of individual mRNAs in real time. The physiological response of the tagged gene to neuronal activity is identical to endogenous Arc and reports the true dynamics of Arc mRNA from transcription to degradation. The transcription dynamics of Arc in cultured hippocampal neurons revealed two novel results: (i) A robust transcriptional burst with prolonged ON state occurs after stimulation, and (ii) transcription cycles continue even after initial stimulation is removed. The correlation of stimulation with Arc transcription and mRNA transport in individual neurons revealed that stimulus-induced Ca2+ activity was necessary but not sufficient for triggering Arc transcription and that blocking neuronal activity did not affect the dendritic transport of newly synthesized Arc mRNAs. This mouse will provide an important reagent to investigate how individual neurons transduce activity into spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression at the synapse.

INTRODUCTION

A fundamental question in neuroscience is how neuronal stimulation is converted into a structural change to establish a stable connection. For this process to occur, activity-dependent transcription and local protein synthesis are critical events involved in the formation and alteration of neural circuits (1–5). However, it is unclear how specific genes can be activated in response to neuronal activity and how this genetic information can be transferred to a specific site where a connection is affected.

Activity-regulated cytoskeleton-associated protein (Arc; also known as Arg3.1) is an immediate early gene (IEG) that is rapidly induced in the brain by synaptic activity (6, 7). Arc is required for long-term memory formation (8, 9) and has a crucial function for sensitizing the synapse to activity [physiological responses known as long-term potentiation (LTP) (10, 11), long-term depression (LTD) (12, 13), and homeostatic plasticity (14)]. Besides neurons, Arc regulates actin dynamics and cytoskeletal rearrangements in various other cell types (15, 16). In neurons, Arc transcription sites appear in the nucleus within a few minutes after stimulation, and mRNAs are subsequently exported and localize to the activated region of dendrites (17, 18). Because Arc mRNA induction is sensitive to changes in behavioral tasks (9, 19), imaging of Arc expression is one of the most powerful approaches to identify activated neurons in response to various learning and memory paradigms. A technique, termed cellular compartment analysis of temporal activity by fluorescence in situ hybridization (catFISH) (9), has been widely used to identify activated neurons in fixed brain tissues. In attempts to image Arc expression in living animals, several mouse models have been generated: a knock-in mouse in which green fluorescent protein (GFP) replaces the Arc protein sequence (20), and a transgenic mouse expressing GFP or luciferase ectopically under the control of the Arc promoter (21–23). Mouse models that express tamoxifen-dependent recombinase CreERT2 upon Arc transcription have also been developed to identify neurons activated by defined stimuli (24, 25). However, all these mouse models rely on the expression of an Arc promoter–driven reporter protein as an indicator of neuronal activation but do not report the spatiotemporal distribution of the mRNA, which carries the information from the gene to a specific location in the dendrite. An animal model that allows direct visualization of endogenous Arc mRNA dynamics in vivo does not exist.

To address this experimental deficit, we developed a novel mouse model where a tandem array of PP7 binding sites (PBS) was inserted into the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the activity-inducible Arc gene, using a similar genetic approach that was used to detect the constitutively expressed β-actin mRNA (26, 27). In heterozygous mouse, the PBS-tagged Arc allele was activated similarly to the untagged wild-type (WT) allele, faithfully capturing the dynamics of endogenous Arc mRNA from activity-dependent transcription to degradation at single-molecule and single-cell resolution. Using cultured hippocampal neurons from homozygous Arc-PBS (ArcP/P) mouse, we characterized the temporal kinetics of transcriptional bursting of the Arc gene in response to neuronal activity. The correlation between neuronal activity and transcription dynamics was investigated using single-molecule FISH (smFISH) and by simultaneous imaging of Ca2+ transients and Arc transcription. In addition, we assessed the effect of neuronal activity on dendritic transport of Arc mRNA by tracking individual mRNAs in real time. The Arc-PBS mouse provides a unique model to investigate the temporal dynamics of transcription from each Arc allele and also of single Arc mRNAs in response to neuronal stimulation.

RESULTS

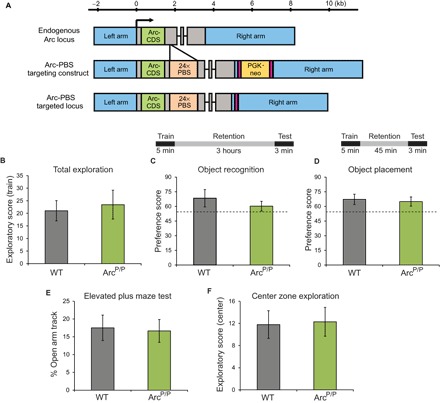

Generation of Arc-PBS knock-in mouse

The Arc gene consists of three exons spanning 3.5 kilo–base pairs (kbp) and encodes for the 396–amino acid Arc protein. To label full-length Arc mRNA, we inserted a 1.5-kbp cassette containing 24 repeats of the PBS stem-loop motif in the 3′UTR of the Arc gene (Fig. 1A). To avoid disruption of evolutionarily conserved cis-acting regulatory elements, we aligned the sequences of the Arc genes in chicken, mouse, rat, and human and 250 nucleotides after the stop codon was targeted for insertion in a nonconserved region. The knock-in of the PBS cassette was performed by homologous recombination, and the embryonic stem (ES) colonies were selected on the basis of neomycin resistance and polymerase chain reaction (PCR). ES cell clones screened for homologous recombination were microinjected into blastocysts, and chimeras were mated to FLPeR mice (ROSA26::FLP) to remove the FLP recombinase target (FRT)–flanked neomycin resistance cassette. Arc-PBS mouse pups without the neomycin cassette were used to backcross to a C57BL/6 background.

Fig. 1. Generation of Arc-PBS knock-in mouse model and behavior characterization.

(A) Schematic of the endogenous Arc locus, Arc-PBS targeting construct, and the final targeted locus. Blue boxes, homology arms for homologous recombination; gray boxes, UTR; green boxes, Arc coding sequence (Arc-CDS); orange boxes, 24× PBS cassette; black lines, introns; pink boxes, FRT sequences; yellow box, PGK-neomycin resistance gene cassette (PGK-neo). PBS cassette was inserted 250 nucleotides downstream of the stop codon of the Arc gene. (B) Exploratory behavior tested by placing animals in an enriched environment and scored during training. (C) Object recognition memory evaluated by training animals for 5 min and then testing after a long retention interval of 3 hours. Scores indicate preference for the novel object. (D) Spatial memory evaluated by training animals for 5 min and then testing after 45 min of retention. Scores indicate preference for the displaced object. Dashed line shows minimum score required to pass. (E and F) Anxiety-like behavior tested on an elevated plus maze test by scoring percentage of track length traversed in the open tracks (E) and time spent in the center zone in an open-field test (F). n = 8 WT and 10 ArcP/P animals.

Both heterozygous and homozygous Arc-PBS knock-in mice were bred and maintained, without any measurable effect on viability and fertility. A battery of behavioral tests was performed on homozygous ArcP/P mice, and they performed comparably to age-matched WT C57BL/6 mice on behaviors related to motor coordination and exploration (Fig. 1B). On hippocampal memory tasks like novel object recognition and spatial memory, they scored similarly to the WT animals (Fig. 1, C and D). Besides, the ArcP/P animals showed no signs of anxiety or stress, as tested from the elevated plus maze tests and center zone exploration [P > 0.05, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA); Fig. 1, E and F].

At the protein level, there were no distinguishable differences in the expression levels of Arc protein in the brains of WT (Arc+/+) and homozygous (ArcP/P) mice (fig. S1A). The stability of Arc mRNA with and without PBS tagging was determined by measuring mRNA lifetime in hippocampal neurons from WT and ArcP/P mice (fig. S1B). Arc mRNAs were induced by stimulating neurons with bicuculline, which blocks GABAA (γ-aminobutyric acid type A) receptors and thereby increases neuronal activity. By fitting mRNA levels to a single-exponential decay function, Arc mRNA had a t1/2 = 60 min for WT and t1/2 = 66 min for PBS-tagged mRNA, indicating that 24× stem-loop insertion did not render the mRNA either unstable or resistant to degradation.

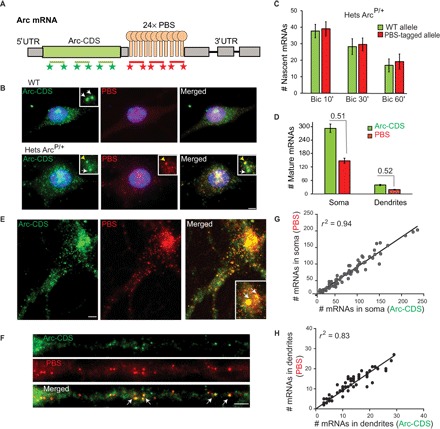

PBS tagging of Arc loci does not alter transcriptional output

A two-color smFISH approach was designed to simultaneously recognize the coding sequence (Arc-CDS) and 24× PBS tag (PBS) on individual Arc mRNAs (Fig. 2A). This approach distinguished mRNAs produced from the WT versus PBS-tagged allele in heterozygous (ArcP/+) mouse, where WT mRNAs were identified by only CDS probes, and PBS-tagged mRNAs had both CDS and PBS probes (Fig. 2B). Quantification of nascent Arc transcripts produced at the transcribing WT versus the PBS-tagged allele showed similar transcriptional output from either allele at different time points of stimulation (Fig. 2C). We also determined that the ratio of the PBS-tagged mRNAs to the total Arc mRNA population was approximately half, as expected, in both the soma and dendrites of heterozygous ArcP/+ mouse (Fig. 2D); no significant difference was observed from the expected value of 0.5 (P > 0.05). This suggested that PBS tagging did not alter the production and stability of Arc mRNA differently from the WT untagged allele at any given time after stimulation.

Fig. 2. PBS tagging does not affect Arc transcription and mRNA stability.

(A) smFISH probes against Arc-CDS and PBS linkers (PBS) to detect mature full-length PBS-tagged Arc mRNAs. (B) Detection of WT and PBS-tagged allele in WT mouse (top) and heterozygous ArcP/+ mouse (bottom) by smFISH with Arc-CDS and PBS probes in bicuculline (Bic)–stimulated neurons. Inset shows transcription sites. Arrows indicate untagged WT allele; yellow arrowhead indicates PBS-tagged allele. (C and D) Quantification of Arc transcripts produced from WT and PBS-tagged allele, as detected by smFISH in neurons from ArcP/+ mouse after bicuculline stimulation. Graphs represent (C) nascent Arc mRNAs produced at transcription sites at different time points after stimulation (n = 40 neurons for Bic 10′, n = 20 for Bic 30′, n = 15 for Bic 60′; no significant differences, P > 0.05 for all conditions) and (D) mature full-length mRNAs in soma and in dendritic segments (up to 100 μm from soma) in ArcP/+ mouse. Ratios of PBS-tagged mRNAs to total Arc mRNAs are shown in (D). Nonsignificant difference from expected 0.5 value (P = 0.60, n = 49 for soma; P = 0.37, n = 45 for dendrites). (E and F) Detection of full-length Arc mRNAs by two-color smFISH with Arc-CDS and PBS probes in ArcP/P mouse. White arrows indicate PBS-tagged Arc alleles in inset (E), and colocalization of CDS and PBS FISH spots in dendrites (F). (G and H) Correlation between the number of mature cytoplasmic mRNAs detected by Arc-CDS and PBS smFISH in the soma (G) and in the dendrites (H) of ArcP/P neurons, indicated by Pearson’s coefficient (r2) (n = 71 for soma, n = 39 for dendrites). Error bars represent SEM. Scale bars, 5 μm.

To further validate the integrity of PBS-tagged Arc transcripts (28), we performed two-color smFISH using Arc-CDS and PBS probes on stimulated neurons from ArcP/P mouse to detect full-length mRNAs (Fig. 2, E and F). The number of mRNAs detected by either probe (Arc-CDS or PBS) was quantified for individual neurons, and high correlations were observed across both soma (r2 = 0.94) and dendrites (r2 = 0.83) (Fig. 2, G and H), indicating that most PBS-tagged Arc mRNAs were intact full-length transcripts. This high correlation (r 2 = 0.91) was maintained following binding of multiple PCP (PP7 coat protein)–GFP molecules to the 24× PBS array on each mRNA (fig. S2, A and B) in PCP-GFP–infected neurons, indicating that no aberrant degradation products owing to the stem-loop–coat protein interactions were being formed. Moreover, neurons with and without PCP-GFP produced a similar number of Arc transcripts after stimulation, indicating that PCP expression and binding to PBS did not affect gene expression (fig. S2, A and C). Hence, PBS tagging and the binding of the PCP to PBS-tagged mRNA did not alter transcriptional output and stability of mRNAs. This is particularly important for Arc, because it is a short-lived mRNA with a tightly controlled degradation after induction. Therefore, PBS tagging can be used reliably to image spatiotemporal fluctuations of Arc mRNA levels.

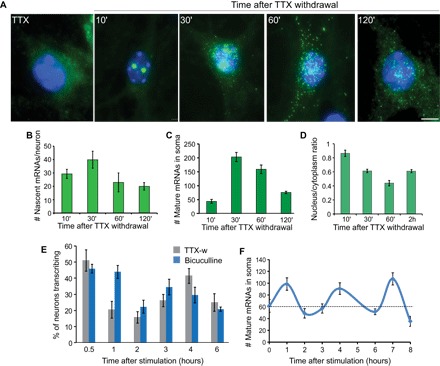

Immediate early activation of the PBS-tagged Arc gene in response to stimulation

Previous studies have reported rapid induction of Arc transcription in response to neuronal activity in neuronal cultures (29, 30). Silencing neuronal electrical activity for 12 to 16 hours using tetrodotoxin (TTX), a sodium channel blocker, followed by withdrawal of TTX induces synchronous neuronal activity. smFISH was performed using PBS probes to detect single Arc mRNAs in neurons from ArcP/P mouse (Fig. 3A). No Arc mRNAs were detected during TTX incubation. Within 10 min of TTX withdrawal, robust Arc induction with transcription from both alleles was observed, reaching maximal transcriptional output at 30 min after TTX withdrawal (Fig. 3, A to C and E). The number of Arc mRNAs in the cytoplasm was the highest at 30 min, followed by a decrease at 120 min after withdrawal (Fig. 3, A and C). These newly synthesized PBS-tagged Arc mRNAs were exported effectively out of the nucleus, as indicated by the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, which showed high levels of nuclear transcripts (high ratio) within the first 30 min, followed by transfer to the cytoplasm (lower ratio) at later times (Fig. 3D). Surprisingly, after the initial activation-decay cycle of 2 hours, the Arc genes in the culture demonstrated subsequent transcriptional activity without additional external stimulation. This phenomenon was also observed using a different stimulation paradigm of bicuculline (40 μM) treatment for 15 min and washout (Fig. 3E), indicating that the transcription continued after the stimulation, and possibly represents an inherent feature of the Arc gene or the activity of the network of cultured neurons. Thus, at this ensemble level, a pulsatile behavior of Arc mRNA production was observed with a periodicity of approximately 2 hours (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3. Time course of Arc transcription in ArcP/P mouse neurons after stimulation.

(A) Hippocampal neurons were treated with TTX (1.5 μM) for 12 to 16 hours, followed by release from TTX, and then fixed at different time points for smFISH using probes against the PBS linkers. Transcription from both alleles was observed. (B to D) Graphs representing the time course of average number of nascent transcripts produced at both transcribing alleles (B), average number of mature mRNAs in the soma (C), and the nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of mRNAs in soma (D). (E) Percentage of Arc-transcribing neurons at different time points following TTX withdrawal (TTX-w) and bicuculline treatment (n = 3 independent experiments, 70 to 80 neurons each time point). (F) Average number of Arc mRNAs in the soma after bicuculline stimulation. Black dashed line indicates average number of mRNAs in the basal condition (n = 40 to 50 neurons per time point). Error bars represent SEM. Scale bar, 5 μm.

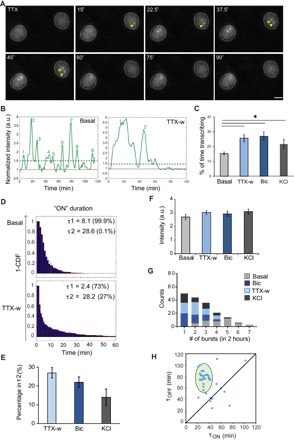

Transcriptional bursting of Arc in hippocampal neurons from ArcP/P mice

Imaging Arc transcription and mRNA dynamics in live neurons is the primary advantage of the Arc-PBS mouse. Cultured hippocampal neurons from ArcP/P mice were infected with lentivirus expressing stdPCP-stdGFP fusion protein with a nuclear localization signal (NLS). The freely diffusible stdPCP-stdGFP proteins are sequestered in the nucleus and bind to the newly transcribed PBS stem-loops with a high specificity and affinity (31, 32), enabling visualization of Arc mRNA synthesis at each active allele. Under basal (nonstimulated) conditions, Arc transcription was detected in a small percentage of neurons due to spontaneous activity in cultures, and this was completely eliminated by TTX incubation. Upon stimulation (TTX withdrawal), transcription from one or both Arc alleles was observed (Fig. 4A and movie S1).

Fig. 4. Real-time measurements of activity-dependent transcription dynamics of Arc.

(A) Snapshots of Arc-transcribing alleles, before and after TTX withdrawal (time in minutes). Green and yellow arrowheads indicate transcription from a single and both Arc alleles, respectively. (B) Intensity profiles of transcription sites under basal and stimulated conditions. Solid line indicates the baseline normalized to the nuclear background. Dashed line indicates the threshold for transcriptional burst (ON state). Numbers indicate the count of transcriptional bursts. a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Percentage of time in the actively transcribing state within the 2-hour time window for basal and stimulated conditions (*P < 0.05, two-tailed t test). (D) Inverse cumulative probability distribution of active (ON) duration of Arc transcription fitted to a two-component model, showing two time constants: τ1 and τ2. Percentage of events belonging to either τ1 or τ2 is indicated. CDF, cumulative distribution function. (E) Percentage of events in τ2 duration using different stimulation paradigms. (F) Amplitude of transcriptional burst. (G) Frequency histogram of transcriptional bursts in 2-hour time window. (H) Graph representing the relationship of OFF duration (τOFF) following an ON duration (τON ≥ τ2) in neurons after stimulation. Shaded ellipse indicates means ± 2 SDs (n = 36 alleles). Error bars for all panels indicate SEM (n = 37 cells for basal, 41 for TTX-w, 30 for Bic, and 32 for KCl from three independent experiments). Scale bar, 10 μm.

As evident from the images and the representative transcription intensity traces, individual neurons after stimulation showed transcriptional activity, followed by periods of inactivity (Fig. 4, A and B). This phenomenon, referred to as transcriptional bursting, has been associated with many mammalian genes and contributes to stochasticity in gene expression (33). An example time series with the Arc gene switching between transcriptionally active (ON) and inactive (OFF) states is shown for basal and stimulated conditions (Fig. 4B). With stimulation, a twofold higher probability of transcriptional ON state was observed compared to the basal level (P < 0.05, t test; Fig. 4C). On the basis of the model of transcriptional bursting, the higher transcriptional output of the Arc gene can occur by (i) increasing the duration of active (ON) period, (ii) increasing the frequency of bursts, or (iii) up-regulating the amplitude of each burst. Each of these scenarios was evaluated on the basis of the bursting kinetics of the Arc gene. The duration of the ON states (τON) can be fitted to two components: τ1 (<10 min) and τ2 (≥20 min) (r2 > 0.94 for all conditions; Fig. 4D). Under basal conditions, most transcriptional bursts are short and have an average τON of 8.1 min corresponding to τ1. Following stimulation, a higher fraction of bursts corresponds to longer τ2 component (Fig. 4, D and E), likely resulting in increased transcriptional activity. Stimulation paradigms like TTX withdrawal and bicuculline were more effective in inducing τ2 burst than KCl depolarization (Fig. 4E). The average peak brightness or amplitude of each transcriptional burst remained unchanged after any mode of stimulation (P > 0.05, two-tailed t test; Fig. 4F), indicating that the maximum number of nascent mRNAs produced at the site of transcription is similar between basal and stimulated neurons. The frequency of these transcriptional bursts, however, was reduced after stimulation compared to basal conditions (Fig. 4G). On the basis of these findings, we postulated that the activity-regulated increase in transcriptional output of the Arc gene resulted from increased probability of transcription initiation and a longer transcriptional burst (ON duration), but not from an increase in amplitude or frequency of the active period. To further investigate the relationship between active and inactive periods of Arc transcription in stimulated neurons, the OFF durations (τOFF) immediately following an initial τON duration of τ2 or longer were plotted, and a clustering phenomenon (33) was observed, where an average τ ON of 32.86 ± 1.35 min was followed by τOFF of 78.56 ± 2.29 min (means ± SEM) (Fig. 4H). This highlighted an unknown feature of the Arc gene, whereby a prolonged immediate early active state is followed by long OFF periods. Network activity persists during these OFF periods, as shown by Ca2+ activity even after 60 min of bicuculline washout (fig. S3), but additional transcriptional bursts during this time are not observed.

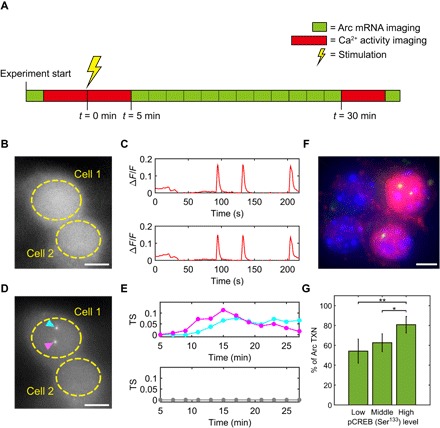

Dual-color imaging of Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription in live neurons

On the basis of real-time observation of Arc transcription following neuronal stimulation, the relationship between neuronal Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription in individual neurons was investigated. Somatic Ca2+ transients have been implicated in activating kinases and transcription factors necessary for inducing transcription (34, 35). We imaged both Ca2+ activity and Arc transcriptional activity from the same neuron before and after stimulation (Fig. 5A). Stimulation with bicuculline induced synchronized somatic Ca2+ spikes in neurons within the field of view (Fig. 5, B and C, and movie S2), with frequency ranging from 0.008 to 0.04 Hz (0.019 ± 0.009 Hz in average) and duration (full width at half maximum) ranging from 2 to 14 s (6.4 ± 3.2 s in average). Synchronous Ca2+ spiking was also confirmed by imaging ~20 neurons simultaneously at a lower magnification (fig. S4). Such synchronized Ca2+ activity is possibly due to the highly connected network within a culture dish. About 40% of neurons showed synchronized somatic Ca2+ activity even before the stimulation, but the frequency of basal Ca2+ activity was lower (<0.006 Hz in average) compared to that immediately after bicuculline treatment (0.02 Hz in average) (fig. S4E).

Fig. 5. Dual-color imaging of Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription in live neurons.

(A) Experimental scheme of measuring both Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription from the same neuron. One green block represents one z scan through the nucleus to detect Arc transcription sites in the green channel. One red block represents continuous imaging of Ca2+ activity at the mid-plane of the nucleus for ~5 min in the red channel. The same neuron was monitored before and after the stimulation by 50 μM bicuculline. (B) Representative Ca2+ image from the red channel. (C) Synchronized Ca2+ spikes measured from the soma (area within dashed line) of cell 1 (top) and cell 2 (bottom) 5 min after bicuculline stimulation. (D) Representative image of Arc transcription in the same neurons as shown in (B). Transcription from both alleles in cell 1 (cyan and magenta arrowheads) versus no transcription site in cell 2. (E) Time course plot of Arc transcription site (TS) intensity in cell 1 (top) and cell 2 (bottom). (F) Representative image of smFISH-IF showing Arc transcription (green) and pCREB (red) in the nucleus [4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), blue]. (G) Probability of Arc transcription (TXN) in neurons grouped by pCREB levels in the nucleus. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, two-tailed t test. A total of 203 neurons were imaged from four independent experiments. Error bars represent SEM. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Upon exposure to bicuculline, all neurons showed an immediate increase in the frequency of Ca2+ activity, but only 43% exhibited induction of Arc transcription within ~30 min of stimulation (Fig. 5, D and E, and movie S3). Transcriptional initiation time was also highly heterogeneous, ranging from a few minutes to longer than 20 min after stimulation, although Ca2+ activity persisted during the entire duration of bicuculline treatment (fig. S5). The burst width and frequency of Ca2+ activity were compared between neurons with and without Arc transcription within 30 min after bicuculline stimulation (fig. S6); no significant difference was observed (Pks > 0.05, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). These results indicate that although elevated Ca2+ activity is a prerequisite for Arc transcription, it is not sufficient in inducing an active transcriptional burst.

We next investigated a possible mechanism underlying the heterogeneity in Arc transcriptional response to stimulation. The transcription factor CREB (adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate response element–binding protein) has been shown to play a key role in IEG activation (36, 37). To evaluate the levels of nuclear phosphorylated CREB (pCREB; Ser133 residue) in Arc-transcribing cells, we performed immunofluorescence of pCREB along with smFISH for Arc (Fig. 5F). A correlation was apparent when comparing the levels of nuclear pCREB and Arc transcription: a higher probability of Arc transcription in neurons with higher pCREB expression (Fig. 5G). Our results support the idea that, in addition to Ca2+ spiking frequency, other factors such as the amplitude of nuclear Ca2+ signal (34), the absolute amount of CREB (37, 38), and the intrinsic noise in transcription machinery (39) may play important roles in determining the efficiency of transcriptional response to stimulation.

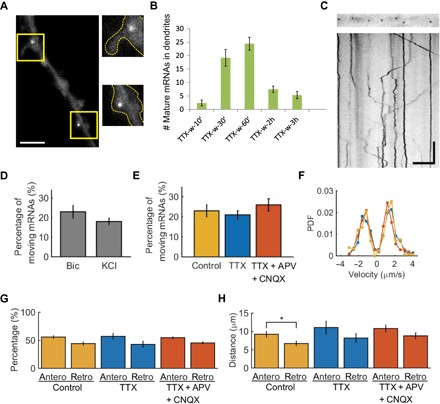

Localization and transport of Arc mRNA in dendrites

Once transcribed, Arc mRNAs are transported to the dendrites and localize at activated synapses (17). In ArcP/P neurons, PBS-tagged endogenous Arc mRNAs were targeted to the dendrites (Fig. 1F) and localized near dendritic spine necks and inside dendritic spines (Fig. 6A). Quantification of total Arc mRNAs within a dendritic segment 100 μm from the soma revealed maximum levels at 60 min, followed by a decrease at 2 hours after stimulation (Fig. 6B). This indicated that, soon after Arc mRNAs were produced, they were compartmentalized into dendrites, where they underwent degradation (40).

Fig. 6. Localization and transport dynamics of dendritic Arc mRNA.

(A) Representative image of Arc mRNAs localized at the neck of a dendritic spine (top right panel) and inside a spine (bottom right panel). (B) Quantification of the average number of mature mRNAs detected in the dendrites (within 100 μm of soma) after TTX withdrawal. (C) Kymograph showing both stationary and actively moving Arc mRNAs in a dendrite. (D) Fraction of mobile Arc mRNAs that moved more than 1.5 μm during 1 min of observation after bicuculline and KCl stimulation. n = 510 and 141 mRNAs for Bic and KCl conditions, respectively. (E) Fraction of mobile Arc mRNAs in the bicuculline washout (control), bicuculline washout + TTX (TTX), and bicuculline washout + TTX + APV + CNQX (TTX + APV + CNQX). n = 510, 427, and 549 mRNAs for control, TTX, and TTX + APV + CNQX conditions, respectively. (F) PDF of the run velocity in control (yellow), TTX (blue), and TTX + APV + CNQX (red) conditions. Velocity of active movement of Arc mRNA was similar among all conditions. (G) Percentage of anterograde (Antero) and retrograde (Retro) movements in all conditions. (H) Histogram of distance traveled by a single run in anterograde and retrograde directions for control, TTX, and TTX + APV + CNQX conditions. *P < 0.05, two-tailed t test. For (E) to (H), a total of 173, 146, and 212 active movements from five independent experiments were analyzed for control, TTX, and TTX + APV + CNQX conditions, respectively. Error bars represent SEM. Scale bars, 5 μm (horizontal) and 10 s (vertical).

We next performed single-particle tracking to follow the movement of individual Arc mRNAs. The directed transport of Arc mRNA occurred in both anterograde and retrograde directions and was often interrupted by pauses (Fig. 6C and movie S4), similar to the previously reported transport behavior of β-actin mRNA (26, 41) and Arc 3′UTR reporter mRNA (42). The fraction of mobile Arc mRNAs that moved longer than 1.5 μm during 1 min of observation was 23 ± 3% (means ± SEM) upon bicuculline stimulation and 18 ± 2% upon KCl depolarization, showing no significant difference between the two stimulation paradigms (P = 0.35, two-tailed t test; Fig. 6D).

Because neuronal activity is crucial for the induction of Arc mRNA, we assessed the effect of neuronal activity on transport dynamics of Arc mRNA. A cocktail of TTX, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist [d,l-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (APV)], and AMPA receptor antagonist [6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX)] was used to block both evoked and spontaneous activity. Dendritic transport of newly synthesized Arc mRNAs was imaged in the proximal dendrites 20 to 40 min after bicuculline treatment and washout (control), bicuculline washout and TTX treatment (TTX), and bicuculline washout followed by TTX, APV, and CNQX treatment (TTX + APV + CNQX). Surprisingly, there was no significant difference in the fraction of actively moving Arc mRNA among all conditions. The percentage of mobile Arc mRNA was 23 ± 3% (means ± SEM) in control condition, 21 ± 3% in TTX condition, and 26 ± 3% in TTX + APV + CNQX condition (Fig. 6E). The motion of Arc mRNA was further analyzed by segmenting the kymographs (Fig. 6C) into two states, run and rest/pause phases, where movement longer than 1.5 μm was defined as a run phase. The velocity probability density functions (PDFs) of run phases were also similar across the three conditions, suggesting that the run phase occurs independent of synaptic activity (Pks > 0.07 for all three pairs, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test; Fig. 6F). The speed of a single run was 1.5 ± 0.7 μm/s, 1.4 ± 0.7 μm/s, and 1.6 ± 0.7 μm/s (means ± SD) for each condition, respectively, which indicates that the active transport of Arc mRNAs on microtubules was not altered by inhibiting neuronal activity. This was irrespective of whether the runs were in anterograde or retrograde directions, because the percentage of run events in either direction was similar in all conditions (Fig. 6G). The average distance traveled by a single anterograde run (9.2 ± 0.8 μm) was significantly longer than that by a retrograde run (6.7 ± 0.6 μm) under stimulated conditions (P < 0.05, two-tailed t test; Fig. 6H). This result suggests that the slightly biased walk with a longer run phase to the anterograde direction possibly mediates the delivery of Arc mRNAs to the distal dendrites. However, neuronal activity did not play a significant role in the transport velocities of Arc mRNA.

DISCUSSION

Here, we have developed a knock-in mouse where the endogenous Arc locus has been labeled with a bacteriophage-derived PBS cassette, which offered unique capabilities for imaging single Arc mRNAs from transcription to dendritic localization. This labeling strategy, albeit with a different stem-loop cassette (MBS), has been used before for the constitutive gene β-actin, allowing visualization of β-actin mRNA dynamics in fibroblasts, neurons, and tissues (26, 27). The work here illustrates that the mRNA labeling strategy with an orthologous bacteriophage stem-loop (PP7) can be successfully applied in this case to an activity-related gene like Arc, which is tightly regulated with a short half-life mRNA. The expression of Arc is important in learning and memory, as Arc null mice show deficits in long-term memory (8). At the molecular level, localization and local translation of Arc mRNA influence LTP and spine remodeling by associating with F-actin, as well as LTD-like processes by regulating AMPA receptor endocytosis (43, 44). Therefore, understanding the life cycle of Arc mRNA from its production to decay with high temporal resolution is imperative for understanding the structural and functional changes associated with plasticity. The Arc-PBS knock-in mouse described here can faithfully capture all life cycle events, without altering the kinetics of production or degradation of the mRNAs. Our mRNA lifetime measurements, as well as dual-color smFISH, confirm that the PBS-tagged mRNAs behave similarly to WT endogenous Arc mRNAs. Furthermore, PBS tagging of both Arc alleles does not result in any behavioral deficits in ArcP/P mouse on hippocampal learning and memory tasks. Therefore, the ArcP/P mouse offers possibilities to investigate the regulation of Arc mRNA in the context of intracellular targeting and localized translation.

The PBS knock-in at the 3′UTR offers unique advantages; the gene is in its native chromosome locus, where its interaction with the cis-regulatory elements (promoters, terminators, enhancers, etc.) is maintained, and therefore, measurements of transcription dynamics by live imaging reflect the gene’s response to stimulation. We demonstrate that transcriptional responses in a neuronal population after global stimulation are heterogeneous and can most likely be attributed to differential levels of transcription factors in the nucleus. For example, the pCREB level in neurons is correlated with higher transcription efficiency, although to establish causality more detailed analysis of CREB regulation and upstream signals is required. Our results emphasize that visualizing an inducible transcriptional response in individual cells is an important complement to ensemble measurements that represent global aspects of gene expression with less precise time resolution. This is illustrated by the correlation between stimulus and gene expression made possible by detection of Ca2+ spikes and Arc transcription in the same neuron. We show that although Ca2+ activity is elevated in most neurons, only about half of the neurons induce Arc transcription. This result indicates that Ca2+ activity alone is not sufficient to induce Arc transcription in cultured hippocampal neurons. It is likely that a highly interconnected signaling network regulates Arc transcription in a tightly controlled manner (45).

Real-time transcription measurements indicate that a possible mechanism by which increased neuronal activity resulted in higher transcriptional output of the Arc gene could be due to induction of a prolonged ON state of transcriptional bursting without changing the amplitude of each burst. This suggests that once RNA Pol II that may have been stalled at the transcription start sites were released upon stimulation (30), they produced the same number of transcripts. Following the activity-induced ON state, we also identified a characteristically long OFF state of the Arc gene, which may have resulted from a closed chromatin conformation (46) and possibly indicates a refractory period of the gene. Similar mechanisms of regulating IEG expression by altering the burst parameters have been described in nonneuronal cells, for example, increased burst frequency of the c-fos gene by changing the levels of transcription factors and increased burst duration of the Ctgf gene in response to stimuli (47, 48). Our results from real-time imaging of Arc loci provide one of the first characterizations of transcriptional bursting in neurons in response to activity. Our smFISH data show that although Arc is an IEG, Arc mRNA levels cycle within the cultured network, suggesting that a feedback loop for reactivation may exist, similar to reports on other genes (49). The transcription dynamics in cultured hippocampal neurons may be relevant to the known physiology of memory formation in the hippocampus following a fear experience (50) or novel environment exploration (51). Toward this end, the Arc-PBS mouse offers possibilities of visualizing mRNAs in the native environment of tissue. Intracranial injection of viral vectors expressing the fluorescent PCP will be a useful strategy to label Arc mRNA in specific brain areas. Alternatively, similar to the approach of the MBS × MCP mouse, we are currently generating an Arc-PBS × PCP-GFP mouse line, where all Arc mRNAs will be fluorescently labeled, facilitating visualization of endogenous mRNAs in the entire neuronal population.

The Arc-PBS mouse also allowed tracking of single mRNAs to determine the route of localization, showing that Arc mRNA transport was bidirectional but biased toward the anterograde direction, possibly due to the slightly polarized orientation of microtubules in dendrites (52, 53). Previously, it has been shown that Arc mRNAs localize to activated synapses (18), and this anterograde bias may be important for localization to distal sites. We investigated whether the moving fraction of the mRNAs and their dynamics were altered by inhibiting neuronal activity. Blocking action potentials and glutamatergic currents for 20 to 40 min did not significantly change the moving fraction of Arc mRNAs or the speed and distance of a single run. This might be due to the effect from signaling cascades or synaptic tags that were activated during stimulation and were retained. Our results support the idea that NMDA receptor–dependent localization of Arc mRNA (18) may occur by docking and/or degradation of the mRNA (40) rather than by controlling the mRNA mobility. This temporal nature of Arc mRNA localization can be further investigated in tissue by stimulation or inhibition of synaptic pathways.

Therefore, the ArcP/P mouse offers possibilities to investigate the regulation of Arc mRNA in the context of intracellular targeting and localized translation in tissues and in the live animal as well. In light of the recent findings of Arc mRNA and proteins capable of forming Arc capsids and mediating intercellular transport across neurons (54, 55), the Arc-PBS–tagged mouse will allow visualization of such events during synaptic plasticity. We anticipate that the Arc-PBS mouse will be a powerful tool to bridge the gap between electrophysiology and spatiotemporal gene expression, by correlating behavior with the life cycle of Arc mRNA, under learning and behaving conditions in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Arc-PBS knock-in mouse

Animal care and experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Janelia Research Campus of Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI), and Seoul National University. Targeting construct for Arc allele was produced by using conventional cloning approaches with homology arms amplified from the C57BL/6J mouse bacterial artificial chromosome vector RPCI-23-81J22. After verification by sequencing, the targeting construct was electroporated into 129S6 × C57BL/6 F1 hybrid ES cell line. ES cell clones were screened for homologous recombination by PCR. Correctly targeted ES cells were microinjected into BL/6 blastocysts, and chimeras were mated to FLPeR mice (ROSA26::FLP) to remove the FRT-flanked neomycin resistance cassette in the offspring. Pups without the PGK-neo cassette were identified by PCR and used to backcross to a C57BL/6J background. Experiments were performed using either nonbackcrossed mouse line or seventh backcross generation line. We have not observed any qualitative difference between nonbackcrossed and seventh backcross generation mice.

Genotyping

To genotype Arc-PBS knock-in mice, we performed PCRs using the following primer sets. For the 5′ end, we used two forward primers, Arc-PBS gt 5F (5′-TGTCCAGCCAGACATCTACT-3′) and Arc-PBS gt 5R (5′-TAGCATCTGCCCTAGGATGT-3′), and one reverse primer, PBS scr R1 (5′-GTTTCTAGAGTCGACCTGCA-3′), yielding a 320-bp product for the WT allele and a 228-bp product for the PBS knock-in allele. For the 3′ end, we used a forward primer, Arc-PBS gt 3F (5′-GACCCATACTCATTTGGCTG-3′), and a reverse primer, Arc-PBS gt 3R (5′-GCCGAGGATTCTAGACTTAG-3′), yielding a 332-bp product for the WT allele and a 413-bp product for the PBS knock-in allele. PCR conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 35 cycles.

Hippocampal neuron preparation, viruses, and stimulation paradigms

Hippocampi were dissected out from postnatal day 1 (P1) pups from ArcP/P homozygous, ArcP/+ heterozygous, and C57BL/6 WT (Charles River Laboratories) mice. Hippocampal neurons were isolated as described before (56). Briefly, hippocampi were digested with 0.25% trypsin at 37°C for 15 min, followed by trituration and plating onto poly-d-lysine–coated MatTek dishes. For FISH and live experiments, 45,000 and 65,000 cells per dish, respectively, were plated. Neurons were plated and maintained in NGM (Neurobasal A medium supplemented with B-27, GlutaMAX, and primocin). All reagents were obtained from Life Technologies unless mentioned otherwise.

Coding sequences for NLS-stdPCP-stdGFP were cloned into lentiviral or adeno-associated virus (AAV) expression vectors. The synonymous versions of PCP (stdPCP) and GFP (stdGFP) were designed on the basis of previously described coat proteins and fluorescent proteins (32). Lentivirus was generated as described before using the plasmids for ENV (pMD2.VSVG), p/MDLG, Rev (pRSV-Rev), and pMDLg/pRRE along with the expression vector in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells by calcium phosphate method. Virus containing supernatant was concentrated using a Lenti-X concentrator (Clontech Laboratories), resuspended in Neurobasal A medium, and stored at −80°C. Dissociated hippocampal neurons were infected with NLS-stdPCP-stdGFP lentivirus (32) at 10 days in vitro (DIV 10) and imaged at DIV 16 and 17 for transcription sites and single mRNAs. Serotype 2/1 AAV vector for the expression of hSyn-NLS-stdPCP-stdGFP was generated using the AAV Helper-Free System (Agilent Technologies). The final concentration of AAV infection was ~109 genome copies per milliliter. After infection with either lentivirus or AAV, no medium change was performed, and NGM was added to the cultures every 3 days.

Three kinds of stimulation paradigms were used to study Arc induction in hippocampal cultures. Before any stimulation, 1 ml of conditioned medium (CM) was saved from each MatTek dish to be added back later after washout of the drug. For bicuculline stimulation, 50 μM bicuculline methiodide (Tocris Bioscience) was added for 15 min, followed by two washes with Neurobasal A medium and adding back CM along with NGM. For TTX withdrawal experiments, cultures were treated with 1.5 to 2 μM TTX (TTX citrate, Tocris Bioscience) overnight (14 to 16 hours), followed by two washes with Neurobasal A medium and adding back CM along with NGM. KCl stimulation was performed in Hepes-buffered saline (HBS) medium containing 60 mM KCl for 3 min, followed by three washes with HBS. All time points were measured after washout.

Behavioral experiments

Two-month-old animals from WT (n = 8) and ArcP/P (n = 10) were used for the study. All mice were subjected to a battery of tests on the behavioral spectrometer (Behavioral Instruments), which can automatically monitor different behavioral classes—general locomotion, grooming, orientation, exploratory behavior, and thigmotaxis (center versus peripheral exploration). The test is conducted for a total of 9 min. For object recognition and object placement tests, the mice were placed in an opaque arena with two identical objects for 5 min, after which they were returned to their home cages. For objection recognition, the animals were returned to the arena after a retention interval of 180 min, in which one of the familiar objects had been replaced with a novel object. For object placement, after a retention interval of 45 min, one of the identical objects was moved to a different location. For both conditions, the test period was for 3 min. A preference score was calculated on the basis of the time spent in exploring the novel object (object recognition) or the newly displaced object (object placement) divided by the total time spent exploring both objects. An exploratory preference score higher than 50% indicates intact recognition memory. A cutoff criterion for passing was empirically set at 55% preference. In elevated plus maze test, the animals were placed in the center of an elevated four-arm maze, having two open and two enclosed arms for 5 min. The activity was measured by total track length traversed in the entire arena. The percent of track spent in the open arms was calculated. Anxiety-like behavior was determined by reduced exploration of the open arms. For all the tests, one-way ANOVA was performed to determine the statistical significance in the performance score between WT and ArcP/P animals.

smFISH and smFISH-IF

Hippocampal neurons at DIV 16 to 18 were stimulated with bicuculline (40 μM for 15 min), followed by washout with Neurobasal medium three times, and incubated with a 1:1 ratio of previously stored CM and fresh NGM. In TTX withdrawal paradigm, neurons were incubated with 1.5 μM TTX for 12 hours (overnight), followed by withdrawal by washing twice with Neurobasal medium and adding NGM. The dishes were incubated for different time points after stimulation. Neurons were fixed with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and 4% sucrose containing phosphate-buffered saline supplemented with 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 mM CaCl2 (PBS-MC), as described before (57). Following permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS-MC for 15 min on ice, neurons were treated with a prehybrization buffer containing 12% formamide, 2× SSC in ribonuclease (RNase)–free water for 30 min. Hybridization was carried out at 37°C using a hybridization buffer [2× SSC, 10% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, bovine serum albumin (BSA) (20 mg/ml), Escherichia coli transfer RNA (1 mg/ml), 2 mM vanadyl ribonucleoside complex, SUPERase·In (10 U/ml; Ambion) in RNase-free water] for 4 hours, as described before (57), using 20-mer DNA probes. Probes were used against the PBS linker sequences (27) (a mix of three probes, dual end-labeled), called PBS, conjugated to Cy3 or Cy5 (Amersham Biosciences), and also against Arc-CDS conjugated to Quasar 570 (Biosearch) (table S1). The neurons were then washed with prehybridization buffer, followed by 2× SSC to remove excess unbound probes, counterstained with DAPI (0.5 μg/ml in phosphate-buffered saline), and mounted using the ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). Images were acquired using oil immersion 40× and 100× objectives on an epifluorescence Olympus BX83 microscope, with an X-Cite 120 PC lamp (EXFO) and an ORCA-R2 digital charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Hamamatsu). Z sections were acquired every 300 nm, and the entire volume of the neuron was imaged. FISH spots were analyzed by three-dimensional (3D) Gaussian fitting of spots using FISH-quant software (58) on MATLAB platform. The number of FISH spots varies depending on the probes used and the efficiency of hybridization. Therefore, using two different probe sets for the same mRNA may yield differences in the absolute mRNA counts.

For simultaneous detection of pCREB and Arc transcription, a combination of smFISH and immunofluorescence (smFISH-IF) was performed. AAV viral infection (AAV-hSyn-NLS-tdPCP-tdGFP) was done on DIV 6 and 7. After neurons were placed in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 20 min with 50 μM bicuculline, they were fixed for 20 min with cold 4% PFA and 4% sucrose in PBS-MC. Quenching was done for 15 min with 50 mM glycine in PBS-MC. Neurons were permeabilized for 15 min with cold 0.1% Triton X-100 and 0.5% BSA in PBS-MC. Blocking and prehybridization were performed for 30 min at room temperature with 10% formamide, 2× SSC, and 0.5% BSA in RNase-free water. Hybridization of FISH probes and primary antibody was done together. Neurons were incubated at 37°C for 3 hours with 10 ng of PBS probes (27) and primary antibody against Ser133 residue pCREB (06-519, Millipore) in hybridization buffer. Neurons were quickly washed twice with warm 10% formamide, 3% BSA in 2× SSC. Then, hybridization with the secondary antibody was performed twice with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated secondary antibody (A21245, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 10% formamide and 2× SSC in RNase-free water at 37°C for 20 min each. After cells were washed four times with 2× SSC, they were stained with DAPI (57).

Real-time imaging of transcription

Hippocampal neurons were plated at densities of 65,000 to 70,000 cells per MatTek dish and infected with lentivirus expressing stdPCP-stdGFP at DIV 10. Neurons were grown in NGM containing phenol-free Neurobasal A (Invitrogen) and imaged between DIV 16 and 19 in NGM on a heated chamber at 35°C, with flow of 5% CO2. For TTX withdrawal experiments, neurons were incubated with TTX (1.5 μM) for 12 to 16 hours. Live imaging was first done in TTX-containing medium, followed by washes with Neurobasal A and addition of fresh medium, and then imaged 10 min after washout. For bicuculline experiments, neurons were treated with 40 μM bicuculline for 15 min, washed twice with Neurobasal A, and imaged in fresh medium. For basal conditions, the neurons were imaged in NGM, without any treatment or washout. A wide-field fluorescence microscope equipped with iXon Ultra DU-897U electron-multiplying CCD (EMCCD) camera (Andor), 60× oil immersion objectives (Olympus), MS-2000-500 XYZ automated stage (ASI), and IX73 microscope body (Olympus) was used, as described before (56). Excitation was achieved using a 488-nm laser, and z sections of the nuclei were acquired every 500 nm. Maximal projection images were shown, with a filtering of Gaussian blur of 0.2, done on ImageJ. Time-lapse imaging of Arc transcription sites was performed in NGM for 2 to 3 hours, with an imaging interval of either 60 or 90 s.

Two-color imaging of Ca2+ and Arc transcriptional dynamics

Neurons were infected with AAV-hSyn-NLS-tdPCP-tdGFP on DIV 6 and 7. Live-cell imaging experiments were performed on DIV 14 to 17. Two microliters of 2 mM red-shifted Ca2+ indicator (Ca2+ Orange, Molecular Probes) was added to neurons in 2 ml of NGM, and neurons were incubated in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min. Then, cells were washed twice with warm HBS (119 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 30 mM d-glucose, 20 mM Hepes in deionized water at pH 7.4) and placed in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 30 min again.

After 30 min of incubation, neurons were imaged by using a wide-field fluorescence microscope equipped with an iXon Ultra DU-897U EMCCD camera (Andor), a UApo 150× oil immersion objective (Olympus), an MS-2000-500 XYZ automated stage (ASI), and an IX73 microscope body (Olympus). A CU-201 heating chamber (Live Cell Instrument) was used to maintain the temperature at 37°C. The Micro-Manager software was used for image acquisition. Fluorescence excitation source was SOLA SE white light-emitting diode (Lumencor), and appropriate filter sets were used for fluorescence observation [49002 ET-EGFP filter set (Chroma) for GFP-tagged Arc mRNA observation and 49004 ET-Cy3/TRITC filter set (Chroma) for Ca2+ activity observation]. Separate image acquisition schemes were used for imaging transcription and Ca2+ activity. To detect any transcription site in the whole nucleus, a z-section image of a neuron was taken in green fluorescence channel. Then, time-lapse images of baseline Ca2+ activity were acquired at 2 Hz for 4 to 6 min in red fluorescence channel at a single plane. After 50 μM bicuculline was added, induced Ca2+ activity was imaged for 4 to 5 min, followed by z-section images of Arc mRNA transcription every 2 min starting from 5 min until 27 min. Finally, Ca2+ activity was imaged again for 4 to 7 min.

Imaging dendritic transport of Arc mRNA

Neurons were infected with AAV-hSyn-NLS-stdPCP-stdGFP on DIV 11 to 13. Live-cell imaging experiments were performed on DIV 14 and 15. For bicuculline washout condition, neurons were stimulated with 50 μM bicuculline in NGM and placed in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 20 min. After washing with warmed HBS medium, neurons were brought to the wide-field fluorescence microscope described above and incubated at 37°C for 20 min until the microscope system became equilibrated. During equilibration, several fields of view that contained a few dendrites were selected. Then, each site was imaged at 5 Hz for 1 min during 40 to 60 min after the onset of bicuculline stimulation. To inhibit action potentials, the sodium channel blocker TTX was used. To inhibit NMDA and AMPA receptors, APV and CNQX were used, respectively. For bicuculline washout + TTX and bicuculline washout + TTX + APV + CNQX conditions, Arc transcription was also induced by 50 μM bicuculline for 20 min. Then, neurons were washed and incubated with 1.5 μM TTX or 1.5 μM TTX + 300 μM APV + 10 μM CNQX in HBS medium. All the following procedures and parameters for imaging of bicuculline washout + TTX condition and bicuculline washout + TTX + APV + CNQX condition were the same as those for bicuculline washout condition.

Image analysis

Transcription sites were analyzed on the basis of a custom script in MATLAB for particle tracking, as described before (59). Semiautomated tracking of transcription sites was performed based on the maximum intensity pixel. The intensity traces of transcription sites in the filtered images were normalized by the background signal of the nucleus. The value of normalization to 1 represents the basal signal when no transcription sites are detected. A rolling average of three frames was done for analysis of transcription sites and to rule out any artifacts in intensity fluctuations from imaging. An intensity threshold of 50% increase above baseline was used for detection of a transcription burst (“ON” state). On the basis of these averaged normalized traces, the ON durations were calculated and plotted as inverse cumulative frequency distributions. These distributions were then fitted to a double-exponential decay function to derive the two ON duration components: τ1 and τ2. The parameters were determined by a maximal likelihood analysis, and the goodness of fit (r2) was determined.

To analyze the data from simultaneous imaging of Arc transcription and Ca2+ activity, time-lapse Arc transcription activity plot was generated by using custom-made transcription analysis program using a part of u-track (60), which detected transcription sites and calculated the intensity amplitude from 2D Gaussian fitting. The average fluorescence intensities of pCREB in the nucleus and background were obtained using ImageJ. The background-subtracted value of pCREB intensity was considered as the pCREB level in the nucleus.

Movements of Arc mRNAs in dendrites were analyzed on the basis of kymographs generated by ImageJ. The run phase was defined as movement with displacement larger than 1.5 μm. The start point and the end point of run phase were annotated manually on kymographs and used to calculate the displacement and the velocity of each particle. The average and SEM were calculated from five independent experiments for each condition in Fig. 6 (E, G, and H). Two-tailed t test was used to determine the P values. For Fig. 6F, the PDFs of run velocity were also obtained from five independent experiments for each condition. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to measure the significance of difference between velocity PDFs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Guo and Janelia Gene Targeting and Transgenics Resources for cloning, electroporation, ES cell screening, and microinjection. We also thank A. Senecal for help with analysis of transcription sites from live imaging. For carrying out the behavioral experiments, we thank M. Gulinello from Behavioral Core, Albert Einstein College of Medicine (Bronx, NY). We thank C. Nwokafor and S. H. Kim for animal maintenance and M. L. Jones for genotyping. Funding: This research was supported by NIH grant NS083085 to R.H.S. and Samsung Science and Technology Foundation project number SSTF-BA1602-11 to H.Y.P. Author contributions: H.Y.P. designed and generated the Arc-PBS knock-in mouse model, done at the Janelia Research Campus of the HHMI. All the authors participated in the study design. S.D. performed all smFISH experiments and live-cell imaging experiments on transcriptional bursting and pulsing. H.C.M. performed experiments on dual-color imaging of Ca2+ activity and transcription, and mRNA transport in dendrites. All authors discussed the results and wrote the paper together. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/6/eaar3448/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

fig. S1. Comparison of homozygous Arc-PBS mouse to WT mouse.

fig. S2. PCP binding to PBS-tagged mRNAs does not alter mRNA integrity.

fig. S3. Persistent synchronized Ca2+ spikes after bicuculline washout.

fig. S4. Synchronized Ca2+ spikes during bicuculline incubation.

fig. S5. Plot of Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription dynamics.

fig. S6. Comparison of somatic Ca2+ spikes between neurons with and without Arc transcription within 30 min after bicuculline stimulation.

table S1. Sequence of the probes used for smFISH against the Arc-CDS and PBS linkers (PBS).

movie S1. Immediate early activation of transcription from PBS-tagged Arc allele.

movie S2. Ca2+ activity of neurons induced by bicuculline stimulation.

movie S3. Arc transcription dynamics induced by bicuculline stimulation.

movie S4. Dendritic transport of Arc mRNA.

Reference (61)

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Buxbaum A. R., Yoon Y. J., Singer R. H., Park H. Y., Single-molecule insights into mRNA dynamics in neurons. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 468–475 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jung H., Gkogkas C. G., Sonenberg N., Holt C. E., Remote control of gene function by local translation. Cell 157, 26–40 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minatohara K., Akiyoshi M., Okuno H., Role of immediate-early genes in synaptic plasticity and neuronal ensembles underlying the memory trace. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 8, 78 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glock C., Heumüller M., Schuman E. M., mRNA transport & local translation in neurons. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 45, 169–177 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steward O., Farris S., Pirbhoy P. S., Darnell J., Van Driesche S. J., Localization and local translation of Arc/Arg3.1 mRNA at synapses: Some observations and paradoxes. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7, 101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Link W., Konietzko U., Kauselmann G., Krug M., Schwanke B., Frey U., Kuhl D., Somatodendritic expression of an immediate early gene is regulated by synaptic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 5734–5738 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyford G. L., Yamagata K., Kaufmann W. E., Barnes C. A., Sanders L. K., Copeland N. G., Gilbert D. J., Jenkins N. A., Lanahan A. A., Worley P. F., Arc, a growth factor and activity-regulated gene, encodes a novel cytoskeleton-associated protein that is enriched in neuronal dendrites. Neuron 14, 433–445 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plath N., Ohana O., Dammermann B., Errington M. L., Schmitz D., Gross C., Mao X., Engelsberg A., Mahlke C., Welzl H., Kobalz U., Stawrakakis A., Fernandez E., Waltereit R., Bick-Sander A., Therstappen E., Cooke S. F., Blanquet V., Wurst W., Salmen B., Bösl M. R., Lipp H.-P., Grant S. G. N., Bliss T. V. P., Wolfer D. P., Kuhl D., Arc/Arg3.1 is essential for the consolidation of synaptic plasticity and memories. Neuron 52, 437–444 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzowski J. F., McNaughton B. L., Barnes C. A., Worley P. F., Environment-specific expression of the immediate-early gene Arc in hippocampal neuronal ensembles. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 1120–1124 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guzowski J. F., Lyford G. L., Stevenson G. D., Houston F. P., McGaugh J. L., Worley P. F., Barnes C. A., Inhibition of activity-dependent Arc protein expression in the rat hippocampus impairs the maintenance of long-term potentiation and the consolidation of long-term memory. J. Neurosci. 20, 3993–4001 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messaoudi E., Kanhema T., Soulé J., Tiron A., Dagyte G., da Silva B., Bramham C. R., Sustained Arc/Arg3.1 synthesis controls long-term potentiation consolidation through regulation of local actin polymerization in the dentate gyrus in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 10445–10455 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park S., Park J. M., Kim S., Kim J.-a., Shepherd J. D., Smith-Hicks C. L., Chowdhury S. M., Kaufmann W. A., Kuhl D., Ryazanov A. G., Huganir R. L., Linden D. J., Worley P. F., Elongation factor 2 and fragile X mental retardation protein control the dynamic translation of Arc/Arg3.1 essential for mGluR-LTD. Neuron 59, 70–83 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waung M. W., Pfeiffer B. E., Nosyreva E. D., Ronesi J. A., Huber K. M., Rapid translation of Arc/Arg3.1 selectively mediates mGluR-dependent LTD through persistent increases in AMPAR endocytosis rate. Neuron 59, 84–97 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shepherd J. D., Rumbaugh G., Wu J., Chowdhury S. M., Plath N., Kuhl D., Huganir R. L., Worley P. F., Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron 52, 475–484 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ufer F., Vargas P., Engler J. B., Tintelnot J., Schattling B., Winkler H., Bauer S., Kursawe N., Willing A., Keminer O., Ohana O., Salinas-Riester G., Pless O., Kuhl D., Friese M. A., Arc/Arg3.1 governs inflammatory dendritic cell migration from the skin and thereby controls T cell activation. Sci. Immunol. 1, eaaf8665 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maier B., Medrano S., Sleight S. B., Visconti P. E., Scrable H., Developmental association of the synaptic activity-regulated protein arc with the mouse acrosomal organelle and the sperm tail. Biol. Reprod. 68, 67–76 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steward O., Wallace C. S., Lyford G. L., Worley P. F., Synaptic activation causes the mRNA for the IEG Arc to localize selectively near activated postsynaptic sites on dendrites. Neuron 21, 741–751 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steward O., Worley P. F., Selective targeting of newly synthesized Arc mRNA to active synapses requires NMDA receptor activation. Neuron 30, 227–240 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guzowski J. F., Setlow B., Wagner E. K., McGaugh J. L., Experience-dependent gene expression in the rat hippocampus after spatial learning: A comparison of the immediate-early genes Arc, c-fos, and zif268. J. Neurosci. 21, 5089–5098 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang K. H., Majewska A., Schummers J., Farley B., Hu C., Sur M., Tonegawa S., In vivo two-photon imaging reveals a role of Arc in enhancing orientation specificity in visual cortex. Cell 126, 389–402 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eguchi M., Yamaguchi S., In vivo and in vitro visualization of gene expression dynamics over extensive areas of the brain. Neuroimage 44, 1274–1283 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grinevich V., Kolleker A., Eliava M., Takada N., Takuma H., Fukazawa Y., Shigemoto R., Kuhl D., Waters J., Seeburg P. H., Osten P., Fluorescent Arc/Arg3.1 indicator mice: A versatile tool to study brain activity changes in vitro and in vivo. J. Neurosci. Methods 184, 25–36 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izumi H., Ishimoto T., Yamamoto H., Nishijo H., Mori H., Bioluminescence imaging of Arc expression enables detection of activity-dependent and plastic changes in the visual cortex of adult mice. Brain Struct. Funct. 216, 91–104 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denny C. A., Kheirbek M. A., Alba E. L., Tanaka K. F., Brachman R. A., Laughman K. B., Tomm N. K., Turi G. F., Losonczy A., Hen R., Hippocampal memory traces are differentially modulated by experience, time, and adult neurogenesis. Neuron 83, 189–201 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guenthner C. J., Miyamichi K., Yang H. H., Heller H. C., Luo L., Permanent genetic access to transiently active neurons via TRAP: Targeted recombination in active populations. Neuron 78, 773–784 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park H. Y., Lim H., Yoon Y. J., Follenzi A., Nwokafor C., Lopez-Jones M., Meng X., Singer R. H., Visualization of dynamics of single endogenous mRNA labeled in live mouse. Science 343, 422–424 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lionnet T., Czaplinski K., Darzacq X., Shav-Tal Y., Wells A. L., Chao J. A., Park H. Y., de Turris V., Lopez-Jones M., Singer R. H., A transgenic mouse for in vivo detection of endogenous labeled mRNA. Nat. Methods 8, 165–170 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tutucci E., Vera M., Biswas J., Garcia J., Parker R., Singer R. H., An improved MS2 system for accurate reporting of the mRNA life cycle. Nat. Methods 15, 81–89 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao V. R., Pintchovski S. A., Chin J., Peebles C. L., Mitra S., Finkbeiner S., AMPA receptors regulate transcription of the plasticity-related immediate-early gene Arc. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 887–895 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saha R. N., Wissink E. M., Bailey E. R., Zhao M., Fargo D. C., Hwang J.-Y., Daigle K. R., Fenn J. D., Adelman K., Dudek S. M., Rapid activity-induced transcription of Arc and other IEGs relies on poised RNA polymerase II. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 848–856 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chao J. A., Patskovsky Y., Almo S. C., Singer R. H., Structural basis for the coevolution of a viral RNA-protein complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 103–105 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu B., Miskolci V., Sato H., Tutucci E., Kenworthy C. A., Donnelly S. K., Yoon Y. J., Cox D., Singer R. H., Hodgson L., Synonymous modification results in high-fidelity gene expression of repetitive protein and nucleotide sequences. Genes Dev. 29, 876–886 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suter D. M., Molina N., Gatfield D., Schneider K., Schibler U., Naef F., Mammalian genes are transcribed with widely different bursting kinetics. Science 332, 472–474 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardingham G. E., Arnold F. J. L., Bading H., Nuclear calcium signaling controls CREB-mediated gene expression triggered by synaptic activity. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 261–267 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheng M., McFadden G., Greenberg M. E., Membrane depolarization and calcium induce c-fos transcription via phosphorylation of transcription factor CREB. Neuron 4, 571–582 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bito H., Deisseroth K., Tsien R. W., CREB phosphorylation and dephosphorylation: A Ca2+- and stimulus duration-dependent switch for hippocampal gene expression. Cell 87, 1203–1214 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han J.-H., Kushner S. A., Yiu A. P., Cole C. J., Matynia A., Brown R. A., Neve R. L., Guzowski J. F., Silva A. J., Josselyn S. A., Neuronal competition and selection during memory formation. Science 316, 457–460 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y., Won J., Karlsson M. G., Zhou M., Rogerson T., Balaji J., Neve R., Poirazi P., Silva A. J., CREB regulates excitability and the allocation of memory to subsets of neurons in the amygdala. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 1438–1443 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elowitz M. B., Levine A. J., Siggia E. D., Swain P. S., Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science 297, 1183–1186 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Farris S., Lewandowski G., Cox C. D., Steward O., Selective localization of Arc mRNA in dendrites involves activity- and translation-dependent mRNA degradation. J. Neurosci. 34, 4481–4493 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monnier N., Barry Z., Park H. Y., Su K.-C., Katz Z., English B. P., Dey A., Pan K., Cheeseman I. M., Singer R. H., Bathe M., Inferring transient particle transport dynamics in live cells. Nat. Methods 12, 838–840 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dynes J. L., Steward O., Dynamics of bidirectional transport of Arc mRNA in neuronal dendrites. J. Comp. Neurol. 500, 433–447 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bramham C. R., Alme M. N., Bittins M., Kuipers S. D., Nair R. R., Pai B., Panja D., Schubert M., Soule J., Tiron A., Wibrand K., The Arc of synaptic memory. Exp. Brain Res. 200, 125–140 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korb E., Finkbeiner S., Arc in synaptic plasticity: From gene to behavior. Trends Neurosci. 34, 591–598 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmichael R. E., Henley J. M., Transcriptional and post-translational regulation of Arc in synaptic plasticity. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 77, 3–9 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harper C. V., Finkenstädt B., Woodcock D. J., Friedrichsen S., Semprini S., Ashall L., Spiller D. G., Mullins J. J., Rand D. A., Davis J. R. E., White M. R. H., Dynamic analysis of stochastic transcription cycles. PLOS Biol. 9, e1000607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Senecal A., Munsky B., Proux F., Ly N., Braye F. E., Zimmer C., Mueller F., Darzacq X., Transcription factors modulate c-Fos transcriptional bursts. Cell Rep. 8, 75–83 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molina N., Suter D. M., Cannavo R., Zoller B., Gotic I., Naef F., Stimulus-induced modulation of transcriptional bursting in a single mammalian gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 20563–20568 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chubb J. R., Trcek T., Shenoy S. M., Singer R. H., Transcriptional pulsing of a developmental gene. Curr. Biol. 16, 1018–1025 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nakayama D., Iwata H., Teshirogi C., Ikegaya Y., Matsuki N., Nomura H., Long-delayed expression of the immediate early gene Arc/Arg3.1 refines neuronal circuits to perpetuate fear memory. J. Neurosci. 35, 819–830 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Penke Z., Chagneau C., Laroche S., Contribution of Egr1/zif268 to activity-dependent Arc/Arg3.1 transcription in the dentate gyrus and area CA1 of the hippocampus. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 5, 48 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baas P. W., Black M. M., Banker G. A., Changes in microtubule polarity orientation during the development of hippocampal neurons in culture. J. Cell Biol. 109, 3085–3094 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baas P. W., Deitch J. S., Black M. M., Banker G. A., Polarity orientation of microtubules in hippocampal neurons: Uniformity in the axon and nonuniformity in the dendrite. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 8335–8339 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pastuzyn E. D., Day C. E., Kearns R. B., Kyrke-Smith M., Taibi A. V., McCormick J., Yoder N., Belnap D. M., Erlendsson S., Morado D. R., Briggs J. A. G., Feschotte C., Shepherd J. D., The neuronal gene Arc encodes a repurposed retrotransposon Gag protein that mediates intercellular RNA transfer. Cell 172, 275–288.e18 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ashley J., Cordy B., Lucia D., Fradkin L. G., Budnik V., Thomson T., Retrovirus-like Gag protein Arc1 binds RNA and traffics across synaptic boutons. Cell 172, 262–274.e11 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoon Y. J., Wu B., Buxbaum A. R., Das S., Tsai A., English B. P., Grimm J. B., Lavis L. D., Singer R. H., Glutamate-induced RNA localization and translation in neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E6877–E6886 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eliscovich C., Shenoy S. M., Singer R. H., Imaging mRNA and protein interactions within neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E1875–E1884 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mueller F., Senecal A., Tantale K., Marie-Nelly H., Ly N., Collin O., Basyuk E., Bertrand E., Darzacq X., Zimmer C., FISH-quant: Automatic counting of transcripts in 3D FISH images. Nat. Methods 10, 277–278 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corrigan A. M., Chubb J. R., Quantitative measurement of transcription dynamics in living cells. Methods Cell Biol. 125, 29–41 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaqaman K., Loerke D., Mettlen M., Kuwata H., Grinstein S., Schmid S. L., Danuser G., Robust single-particle tracking in live-cell time-lapse sequences. Nat. Methods 5, 695–702 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patel T. P., Man K., Firestein B. L., Meaney D. F., Automated quantification of neuronal networks and single-cell calcium dynamics using calcium imaging. J. Neurosci. Methods 243, 26–38 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/6/eaar3448/DC1

Supplementary Materials and Methods

fig. S1. Comparison of homozygous Arc-PBS mouse to WT mouse.

fig. S2. PCP binding to PBS-tagged mRNAs does not alter mRNA integrity.

fig. S3. Persistent synchronized Ca2+ spikes after bicuculline washout.

fig. S4. Synchronized Ca2+ spikes during bicuculline incubation.

fig. S5. Plot of Ca2+ activity and Arc transcription dynamics.

fig. S6. Comparison of somatic Ca2+ spikes between neurons with and without Arc transcription within 30 min after bicuculline stimulation.

table S1. Sequence of the probes used for smFISH against the Arc-CDS and PBS linkers (PBS).

movie S1. Immediate early activation of transcription from PBS-tagged Arc allele.

movie S2. Ca2+ activity of neurons induced by bicuculline stimulation.

movie S3. Arc transcription dynamics induced by bicuculline stimulation.

movie S4. Dendritic transport of Arc mRNA.

Reference (61)