Abstract

This study was a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of ranitidine as an adjunct for antipsychotic-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia. RCTs reporting weight gain or metabolic side effects in patients with schizophrenia were included. Case reports/series, non-randomized or observational studies, reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded. The primary outcome measures were body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and body weight (kg). Four RCTs with five study arms were identified and analyzed. Compared with the control group, adjunctive ranitidine was associated with marginally significant reductions in BMI and body weight. After removing an outlier study for BMI, the effect of ranitidine remained significant. Adjunctive ranitidine outperformed the placebo in the negative symptom score of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale. Although ranitidine was associated with less frequent drowsiness, other adverse events were similar between the two groups. Adjunctive ranitidine appears to be an effective and safe option for reducing antipsychotic-induced weight gain and improving negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Larger RCTs are warranted to confirm these findings.

Trial registration

PROSPERO: CRD42016039735

Keywords: Schizophrenia, ranitidine, weight gain, negative symptom, meta-analysis, antipsychotics

Introduction

Antipsychotic (AP)-induced weight gain is common in patients with schizophrenia and has received increased attention in recent decades.1–7 In one study, up to 75% of patients with a first episode of schizophrenia receiving APs experienced weight gain of ≥7%.8 AP-induced weight gain not only increases the risk of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and mortality but also contributes to poor treatment adherence and low quality of life.2,3,9–11

Histamine H2 receptors play an important role in the mechanism of AP-induced weight gain, together with the serotonergic, noradrenergic, and histaminergic systems.12 Ranitidine, a non-imidazole H2 blocker, is an inexpensive medication with a low risk of adverse effects because of its negligible effects on muscarinic, nicotinic, adrenergic, and H1 receptors.13 Although several randomized controlled trials (RCTs)13–16 have examined the efficacy and safety of adjunctive ranitidine for AP-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia, the results were mixed.

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic reviews or meta-analyses on ranitidine as an adjunctive treatment for AP-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia have been published. Therefore, we performed the present meta-analysis of RCTs of adjunctive ranitidine for all AP-induced weight gain in patients with schizophrenia. We also included recent RCTs published in Chinese-language journals that may not be widely known on an international basis.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

Two reviewers independently and systematically searched the PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, Cochrane Library, Chinese Journal Net, WanFang, and China Biology Medicine databases for articles regarding adjunctive ranitidine for schizophrenia from inception of each database until 10 October 2016. The keywords used for the search were (zantic OR ranitidine OR zantic OR Zantac) AND (schizophrenic disorder OR disorder, schizophrenic OR schizophrenic disorders OR schizophrenia OR dementia praecox). We also hand-searched reference lists from relevant review articles for additional studies and contacted the authors for more information if necessary.

The following criteria were used according to the PICOS acronym. Participants (P): adult patients (≥18 years of age) with schizophrenia using any diagnostic criteria. Intervention (I): ranitidine plus APs. Comparison (C): APs plus placebo or AP monotherapy. Outcomes (O): efficacy and safety. Study design (S): RCT reporting body weight or metabolic adversities as primary or secondary outcomes. Case reports/series, non-randomized or observational studies, reviews, and meta-analyses were excluded.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) and body weight (kg). Key secondary outcomes were clinical improvement assessed by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)17 or the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale,18 discontinuation rate, and adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Data extraction

Data were identified, checked, extracted, and analyzed by two independent reviewers. Furthermore, outcomes based on intention-to-treat analysis, if available, were recorded. Any inconsistencies were discussed with and resolved by a third reviewer.

Statistical methods

According to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement,19 Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.3 (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman/) was used to perform the meta-analysis. For meta-analytic pooling of continuous and dichotomous outcomes, the inverse variance method and Mantel–Haenszel test were used to present weighted mean differences (WMDs) and risk ratios (RRs) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs), respectively. When the RR was significant, the number needed to treat or number needed to harm (NNH) was calculated by dividing 1 by the risk difference. Each missing standard deviation (SD) was replaced by the average SD from other RCTs that used the same medication.20 To compensate for study heterogeneity, a random-effects model was used in all meta-analyzable data.21 Both I2 and chi-square statistics were used to identify heterogeneity. When heterogeneity (chi-squared P < 0.1 and I2 > 50%) was present for BMI, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to examine the credibility of the BMI change by excluding one study16 with an outlying effect size (ES) of less than −1.5 (i.e. more than 1.5 SD superiority of ranitidine). In addition, one subgroup analysis was performed (Chinese versus non-Chinese patients). One study13 with three treatment arms compared the combination of ranitidine and two different doses of APs with a control group. Half of the patients were assigned to each ranitidine arm to avoid inflating the number of patients in the control group. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and Egger’s test.22 All analyses were two-tailed, with alpha set at 0.05.

Assessment of reporting biases

According to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration, the Cochrane risk of bias was used to assess the methodological quality of RCTs (Supplementary Figure 1). Their domain was rated as “high risk,” “unclear risk,” or “low risk.”23

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was used to rate each study as “very low,” “low,” “moderate,” or “high” with respect to the quality of evidence of adjunctive ranitidine versus placebo. Furthermore, the Jadad scale (Table 1) ranging from 0 to 5 was used to judge the quality of each RCT.24

Table 1.

Study, patient, and treatment characteristics.

| Study | Number of patients | Blinding | Analyses | Trial duration, weeks | Setting, % | Diagnosis, % | Diagnostic criteria | Illness duration, years | Age at baseline, years (range) | Male sex, % | Control group: Dosage in mg/d, mean (range) | Intervention group: Dosage in mg/d, mean (range) | Jadad score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liang 2016 (China) | T: 120 M: 60 A: 60 | DB | ITT | 24 | Inpatients (100) | Sz (100) | CCMD-3 | <5.0 | 33.0 (18–45) | 52.5 | OLA: NR (5–30) | OLA: NR (5–30) | RAN: 150 (FD) | 4 |

| Mehta and Ram 2014 (India) | T: 75 M: 25 A: 50 | OL | ITT | 8 | Inpatients (100) | Sz (100) | ICD-10 | 5.0 | 31.2 (18–60) | 89.3 | OLA: 25.7 (10–30) | OLA: 24.6 (10–30) | RAN: 150 (FD) | 3 |

| OLA: 26.8(10–30) | RAN: 300 (FD) | |||||||||||||

| Ranjbar et al. 2013 (Iran) | T: 52 M: 27 A: 25 | DB | ITT | 16 | Inpatients (100) | Sz (NR) SzA (NR) SzD (NR) | DSM-IV | NR | 38.1 (NR) | 63.5 | OLA: NR (NR) | OLA: NR (NR) | RAN: 600 (FD) | 5 |

| Sun et al. 2007 (China) | T: 68 M: 33 A: 35 | DB | OC | 10 | Inpatients (100) | Sz (100) | CCMD-3 | 1.6 | 28.6 (19–48) | 56.9 | OLA: NR (10–20) | OLA: NR (10–20) | RAN: 300 (FD) | 4 |

A = augmentation; CCMD-3 = China’s Mental Disorder Classification and Diagnosis Standard, 3rd edition; DSM-IV = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; DB = double blind; FD = fixed dosage; ICD-10 = International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision; ITT = intention to treat; M = monotherapy; NR = not reported; OL = open label; OC = observed cases; OLA = olanzapine; RAN = ranitidine; Sz = schizophrenia; SzD = schizophreniform disorder; SzA = schizoaffective disorder; T = total.

Results

Results of the search

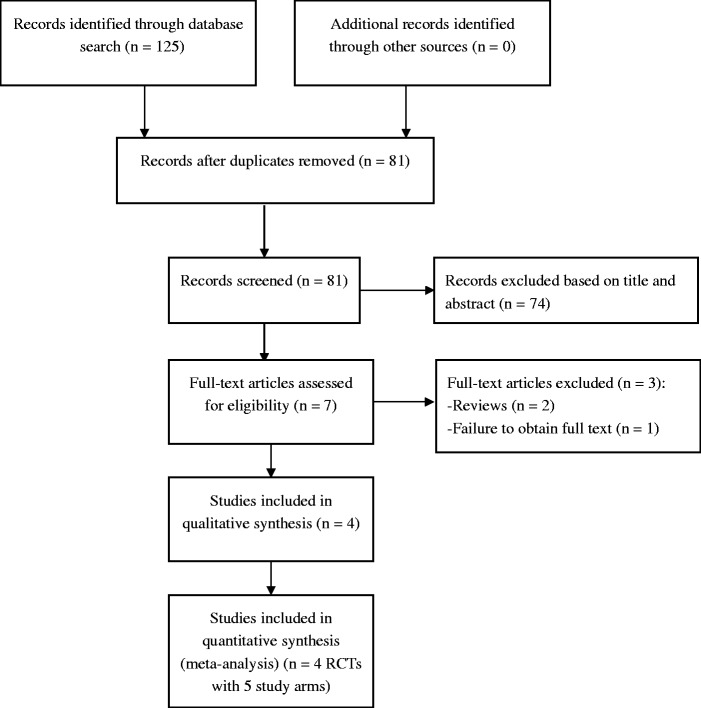

Figure 1 presents a flow chart of article selection from the English (n = 114) and Chinese databases (n = 11). The full text of one RCT25 published in Spanish could not be obtained. In total, four RCTs13–16 were eligible and included in this meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Study characteristics

The four RCTs13–16 with five study arms (n = 315) comprised three double-blinded trials (n = 240) and one open label study (n = 75) comparing an adjunctive ranitidine group (n = 170) and a control group (n = 145). The weighted mean treatment duration was 15.8 weeks (range = 8–24 weeks) (Table 1). Two RCTs were conducted in China (n = 188), one was conducted in India (n = 75), and one was conducted in Iran (n = 52).

Patient characteristics

The weighted mean age was 32.4 years (range = 28.6–38.1 years), the mean percentage of male patients was 64% (range = 52.5%–89.3%), and the weighted mean illness duration (according to the available data in two RCTs13,15) was 3.2 years (range = 1.6–5.0 years) (Table 1). All RCTs were conducted in inpatient settings.

Treatment characteristics

The weighted mean dosage of ranitidine was 339.5 mg/day (range = 150–600 mg/day). All included studies involved only patients who received olanzapine. The weighted mean dosage of olanzapine was 19.1 mg/day (range = 5–30 mg/day) according to the available data in three RCTs.13,15,16

Quality assessment

All four RCTs mentioned “randomized allocation” with a specific description, while the allocation concealment method was rated as “unclear” in one RCT and “high risk” in another RCT. Three RCTs were double-blinded trials, and one RCT was an open label study. Regarding incomplete outcome data, one RCT reported loss to follow-up but failed to use intention-to-treat analysis. Furthermore, two RCTs employed a protocol registration and were rated as “low risk” regarding selective reporting (Supplementary Figure 1). The quality of evidence presented for the primary and secondary outcomes using the GRADE approach ranged from “low” (86%) to “moderate” (14%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

GRADE analyses: Adjunctive ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain.

| Design | N (arms) | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Large effect | Overall quality of evidencea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight (kg) | 312 (5) | None | Seriousb | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 260 (4) | None | Seriousb | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| PANSS total score | 75 (2) | Seriousd | None | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| PANSS positive symptom score | 75 (2) | Seriousd | None | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| PANSS negative symptom score | 75 (2) | Seriousd | None | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| PANSS general symptom score | 75 (2) | Seriousd | None | None | None | Seriousc | None | +/+/−/−/; Low |

| Drowsiness | 165 (3) | None | None | None | None | Seriouse | None | +/+/+/−/; Moderate |

BMI = body mass index; GRADE = Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence: High quality = further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality = further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality = further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality = we are very uncertain about the estimate.

All studies that reported having a serious inconsistency had I2 > 50%.

For continuous outcomes, N < 400.

All studies that reported having a serious bias used a open label method and only mentioned random allocation without describing the method.

For dichotomous outcomes, N < 300.

The weighted mean total Jadad score of the four RCTs was 3.9 (range = 3–5), and all studies were rated as high-quality (Jaded score of ≥3) (Table 1).

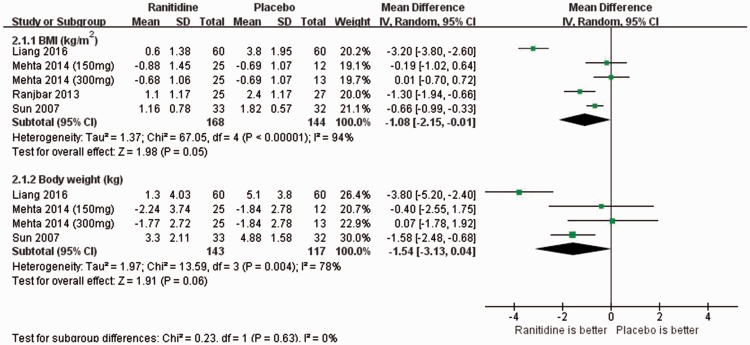

Primary outcomes

Compared with the control group, ranitidine was associated with a marginally significant decrease in the BMI (4 RCTs with 5 study arms, n = 312; WMD: −1.08 kg/m2; 95%CI: −2.15, −0.01; P = 0.05; I2 = 94%) (Figure 2). However, the BMI change was significant even after removing an outlier study16 (n = 120; ES < −1.5; WMD: −0.58 kg/m2; 95%CI: −1.08, −0.07; P = 0.02; I2 = 64%). Moreover, the subgroup analysis revealed that statistical significance was lost for studies of both non-Chinese patients (2 RCTs with 3 study arms, n = 127) and Chinese patients (2 RCTs, n = 185). Furthermore, patients taking ranitidine did not lose weight to a statistically significant degree but only showed a trend (3 RCTs with 4 study arms, n = 260; WMD: −1.54 kg; 95%CI: −3.13, 0.04; I2 = 78%) (Figure 2) compared with the control group. Because only four RCTs with five study arms were included for assessment of the primary outcomes, the presence of publication bias regarding weight change and BMI could not be determined by performing a funnel plot or Egger’s test (<10 trials).26

Figure 2.

Ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain: Forest plot for changes in body weight and body mass index. BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; IV, interval variance; CI, confidence interval.

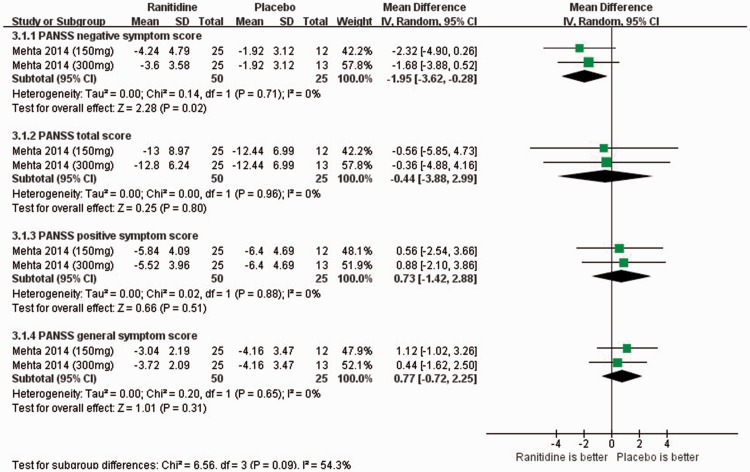

Secondary outcomes

With respect to clinical outcomes, only one RCT with two study arms used the PANSS. The adjunctive ranitidine group outperformed the control group in terms of PANSS negative symptom scores (1 RCT, n = 75; WMD: −1.95; 95%CI: −3.62, −0.28; P = 0.02; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3), but not in terms of PANSS total, positive, or general symptom scores (1 RCT, n = 75; WMD: −0.44 to 0.77; 95%CI: −3.88, 2.99; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain: Forest plot for clinical efficacy assessed by changes in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) score. SD, standard deviation; IV, interval variance; CI, confidence interval.

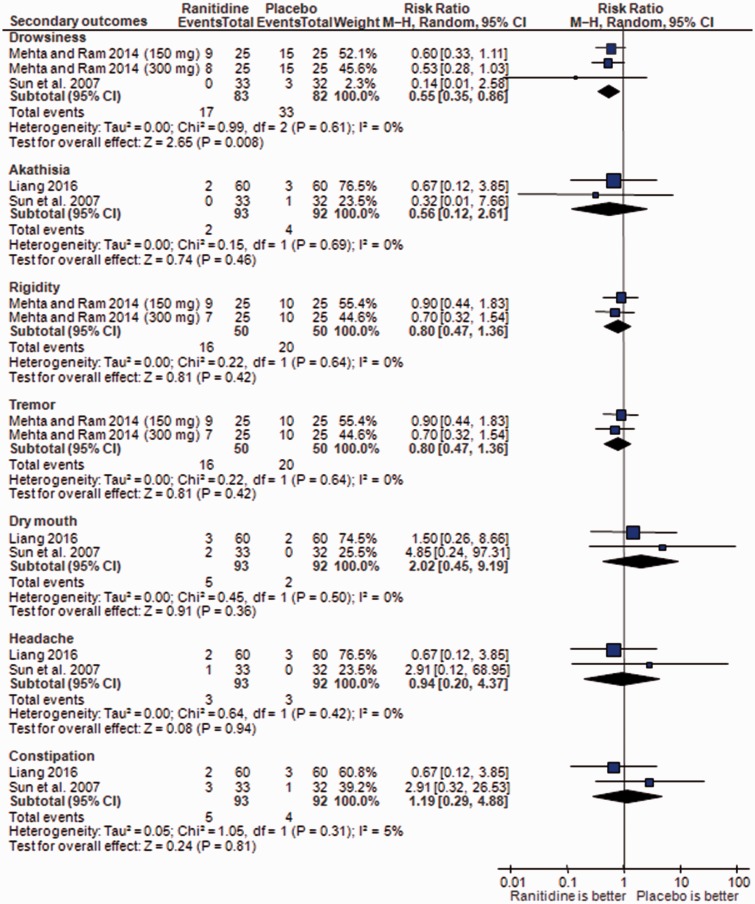

In terms of ADRs, adjunctive ranitidine was associated with less frequent drowsiness than in the control group (3 RCTs, n = 165; RR: 0.55; 95%CI: 0.35, 0.86; P = 0.008; I2 = 0%; NNH = 6; 95%CI = 3, 100) (Figure 4). Meta-analyses of akathisia, rigidity, tremor, dry mouth, headache, and constipation showed no significant group differences (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain: Forest plot for adverse drug reactions. MH, Mantel–Haenszel.

One RCT15 reported a discontinuation rate of 6% (2/35) in the ranitidine group versus 3% (1/33) in the control group. The remaining RCTs did not report the discontinuation rate.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine the effect of adjunctive ranitidine on AP-induced weight gain. The adjunctive ranitidine group outperformed the control group in terms of reductions in weight gain and improvements in negative symptoms. Furthermore, ranitidine was well tolerated. These positive effects of ranitidine support the hypothesis that the histamine H2 receptor is a possible mediator of eating behavior and weight regulation.27 Importantly, the significance the effect remained when the one outlier (ES < −1.5)16 was excluded from the analysis. The lack of significant results regarding Chinese and non-Chinese participants in the subgroup analysis could have been due to the small sample size, which reduced the power to detect statistically significant results.

In this study, the ranitidine group was superior to the control group with respect to improvements in negative symptoms (WMD = −1.95). This may have been due to the direct drug receptor activity of ranitidine itself.13 Ranitidine has been shown to be relatively safe and well tolerated in patients with schizophrenia. Drowsiness (NNH = 6) was less frequent in the ranitidine group than in the control group, and no group difference in other ADRs was evident. Topiramate and metformin may also improve AP-related metabolic ADRs.6 However, we could not locate any head-to-head trials comparing adjunctive ranitidine with topiramate/metformin in patients with schizophrenia.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, there was significant heterogeneity of the results in terms of the primary outcomes. However, a random-effects model was employed to provide a conservative estimate for all meta-analyzable outcomes. Second, only a few studies were available for the meta-analysis because the use of ranitidine for weight loss is off-label. The inclusion of only 4 RCTs involving 315 patients and the limited or incomplete information lessen the confidence of the results and limit more comprehensive data exploration, such as meta-regression analyses. Third, although all four RCTs were rated as high-quality using the Jadad scale,24 86% were rated as “low” using the GRADE approach, especially for BMI and weight change. Furthermore, publication bias for primary outcomes could not be examined because of the limited number of studies.28 Fourth, because the ranitidine dosages varied from 150 to 600 mg/day, the dose–response effect of ranitidine in weight loss could not be further evaluated. Fifth, all RCTs used olanzapine as the baseline AP; therefore, the results could not be generalized to other APs. Furthermore, the >24-week long-term effects of adjunctive ranitidine on body weight could not be investigated. Finally, other metabolic indices including the lipid profile, insulin resistance, and leptin concentration were not recorded in the included studies.

Conclusions

Adjunctive ranitidine appears to be an effective and safe option for treating weight gain and negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Because of the small number of studies available for this meta-analysis, the results should be regarded as preliminary. The long-term effects of ranitidine on weight change and negative symptoms need to be examined in further studies with improved methodology. In addition, the effect of ranitidine on weight gain in patients with other psychiatric disorders should be examined in systematic reviews.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material for Effect of adjunctive ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain: A systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials in Journal of International Medical Research

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the University of Macau (SRG2014-00019-FHS; MYRG2015-00230-FHS; MYRG2016-00005-FHS) and Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University (22016YFC0906302; 2014Y2-00105; 81671334). The University of Macau and Affiliated Brain Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University had no role in the study design, generation or interpretation of the results, or publication of the study. We wish to thank Prof. Phil Wiffen (Training Director of UK Cochrane Center) and Dr. Jun Xia (Cochrane Schizophrenia Group) for their systematic review courses.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Correll CU, Sikich L, Reeves G, et al. Metformin for antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: when, for whom, and for how long? Am J Psychiatry 2013; 170: 947–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maayan L, Vakhrusheva J, Correll CU. Effectiveness of medications used to attenuate antipsychotic-related weight gain and metabolic abnormalities: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35: 1520–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng W, Li XB, Tang YL, et al. Metformin for weight Gain and metabolic abnormalities associated with antipsychotic treatment: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015; 35: 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu RR, Zhang FY, Gao KM, et al. Metformin treatment of antipsychotic-induced dyslipidemia: an analysis of two randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Mol Psychiatry 2016; 21: 1537–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Zheng W, Gao S, et al. Metformin for treatment of clozapine-induced weight gain in adult patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2015; 27: 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng W, Xiang YT, Xiang YQ, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive topiramate for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016; 134: 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng W, Zheng YJ, Li XB, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016; 36: 628–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis J, Watkins A, Rosenbaum S, et al. Evaluating an individualized lifestyle and life skills intervention to prevent antipsychotic-induced weight gain in first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2016; 10: 267–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull 2014; 40: 1385–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poyurovsky M, Isaacs I, Fuchs C, et al. Attenuation of olanzapine-induced weight gain with reboxetine in patients with schizophrenia: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi YJ. Efficacy of adjunctive treatments added to olanzapine or clozapine for weight control in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. ScientificWorldJournal 2015; 2015: 970730–970730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baptista T, Kin NM, Beaulieu S, et al. Obesity and related metabolic abnormalities during antipsychotic drug administration: mechanisms, management and research perspectives. Pharmacopsychiatry 2002; 35: 205–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta VS, Ram D. Efficacy of ranitidine in olanzapine-induced weight gain: a dose-response study. Early Interv Psychiatry 2014; 10: 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranjbar F, Ghanepour A, Sadeghi-Bazargani H, et al. The effect of ranitidine on olanzapine-induced weight gain. Biomed Res Int 2013; 2013: 639391–639391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun J, Xi XD, Li Y, et al. The effect of ranitidine on olanzapine-induced weight gain and metabolic dysfunction [In Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases 2007; 33: 560–562. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang MJ. Effects of ranitidine on the glucose and lipid metabolism level and body mass of patients with olanzapine in treatment of schizophrenia [In Chinese]. Evaluation and Analysis of Drug-use in Hospitals of China 2016; 16: 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13: 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating-scale. Psychol Rep 1962; 10: 799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269, W264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leucht S, Komossa K, Rummel-Kluge C, et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2009; 166: 152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997; 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins J, Higgins J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; 17: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez-Mato A, Rovner J, Illa G, et al. [Randomized, open label study on the use of ranitidine at different doses for the management of weight gain associated with olanzapine administration]. Vertex 2003; 14: 85–96. [in Spanish, English Abstract]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d4002–d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doi T, Sakata T, Yoshimatsu H, et al. Hypothalamic neuronal histamine regulates feeding circadian rhythm in rats. Brain Res 1994; 641: 311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynolds GP, Kirk SL. Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic drug treatment–pharmacological mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther 2010; 125: 169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material for Effect of adjunctive ranitidine for antipsychotic-induced weight gain: A systematic review of randomized placebo-controlled trials in Journal of International Medical Research