Abstract

Objective

Lung adenocarcinoma is a non-small cell lung cancer, a common cancer in both genders, and has poor clinical outcome. Our aim was to evaluate the role of epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domain multiple 6 (EGFL6) and its prognostic significance in lung adenocarcinoma.

Methods

EGFL6 expression was studied by immunohistochemical staining of specimens from 150 patients with lung adenocarcinoma. The correlation between clinicopathological features and EGFL6 expression was quantitatively analysed. We used Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazard models to examine the prognostic value of EGFL6 in terms of overall survival.

Results

No significant correlation was found between EGFL6 expression and clinical parameters. However, patients with high levels of EGFL6 expression showed a tendency towards poor prognosis, with borderline statistical significance. Grouping the patients according to a medium age value revealed a significant association between high EGFL6 expression and poor clinical outcome in young patients. This finding was further confirmed by grouping the patients into three groups according to age. HR in patients with high EGFL6 expression was higher in younger patients than in older patients.

Conclusion

High EGFL6 expression may serve as a marker for poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma, especially in younger patients.

Keywords: egf like domain multiple 6, egfl6, prognosis, non-small cell lung cancer, overall survival, lung adenocarcinoma;

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a retrospective study using specimens from 150 patients with lung adenocarcinoma.

Overall survival, not cancer-specific survival, was used in this study.

This study did not explore the clinical diversity of postoperative chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Considering the limited sample size, further study is necessary for clinical application.

No information on detailed molecular diversity was provided in the analysis.

Introduction

Lung adenocarcinoma, a non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), is a major public health problem worldwide, and NSCLC is a leading cause of cancer death in Taiwan.1 2 Whereas other types of cancer have shown steady increases in survival in recent years, NSCLC continues to have poor clinical outcome, with a 5-year survival of only 18%.3 Early detection of NSCLC might improve the clinical outcome; however, no suitable screening tools that are both cost-effective and efficient are available. NSCLC screening via a low-dose CT scan can provide early detection of lung lesions, such as ground glass opacity lesions.2 However, it does not discriminate benign lesions that may require no further intervention or surgical intervention. Therefore, the identification of specific biomarkers that indicate the malignant potential of NSCLC lesions would help in clinical decision making for cancer follow-up and the timing of surgical intervention.

The malignant potential of a tumour with metastatic behaviour is determined by complex processes, including tumour cell migration, invasion and angiogenesis to the target site.1 4–6 One group of proteins implicated in tumour malignancy is the epidermal growth factor (EGF) repeat superfamily, whose members have a conserved motif of cysteines and glycines positioned in a domain of 30–40 residues.7 8 These EGF-like proteins are characterised by their multiple EGF repeats9 and are secreted as cell surface molecules. The binding of EGF-like proteins to their receptors promotes tumour malignancy.8 10–12

One member of this family, EGF-like domain 6 (EGFL6), is a secreted protein involved in tissue development, promotion of tumour cell migration and angiogenesis.8 10–14 The role of EGFL6 in promoting tumour malignancy is indicated in several types of cancer; for example, patients with oral cancer show high plasma levels of EGFL6, and the plasma EGFL6 level is higher in patients with advanced stage disease than in patients with early-stage disease.10 In ovarian cancer, EGFL6 regulates cell migration and asymmetric division via the SHP2 (known as protein tyrosine phosphatase, non-receptor type 11, PTPN11) oncoprotein, with concomitant activation of extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK).11

Accumulating evidence indicates crucial roles of EGFL6 in promoting tumour malignancy. However, an association between EGFL6 expression and the prognosis of NSCLC remains to be established. Since there are types of pathology subgroups in NSCLC with different tumour behaviours, patients with lung adenocarcinoma were included for investigation. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the expression of EGFL6 and its clinical significance in lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

Patients

Our study examined 150 tumour samples from patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancers were staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual (7th edition). The clinicopathological features assessed in this study included histological type, differentiation, lymph node metastasis, tumour, node, metastases (TNM) stage, and tumour size. Histological diagnosis was confirmed by two pathologists, as described previously.15 Patients with primary lung adenocarcinoma and tissue available in the biobank were included in this survey. Those with missing data or tissue loss during the staining procedure were excluded from this study to avoid bias from missing data.

Immunohistochemical staining and evaluation of cytoplasmic EGFL6

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining was performed at the Department of Surgical Pathology, Changhua Christian Hospital, as previously described,15 16 using antihuman cytoplasmic EGFL6 antibody (EGFL6 antibody, 1:100 dilution; Abcam, ab140079). Immunoreactivity scores were analysed by three pathologists using a previously described scoring protocol.16 Liver tissue was reported to have EGFL6 expression and served as the positive control. IHC assay with a primary antibody in tandem with a specimen that is not exposed to the primary antibody served as the negative control (online supplementary figure 1). The pathologists were blinded to the prognostic data of the study. A final agreement was obtained for each score by having all three evaluators view the specimens simultaneously through a multiheaded microscope (Olympus BX51 10-headed microscope). Immunoreactivity scores were defined as the cell staining intensity (0–3) multiplied by the percentage of stained cells (0%–100%), leading to scores from 0 to 300.15 16

bmjopen-2017-021385supp001.jpg (717.1KB, jpg)

Patient and public involvement

This study analysed cancer tissues from de-linked database. Therefore, we did not inform or disseminate to patients the research question, the outcome measures and the results. Patients were not involved in the study, including in the design, recruitment and conduct of the study. No patient adviser was included in the contributorship statement.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was applied for continuous or discrete data analysis. The associations between cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression and patient survival were estimated using univariate analysis and the Kaplan-Meier method, and were further assessed using the log-rank test.1 Potential confounders including age, gender and stage were adjusted using Cox regression models of multivariate analysis, with the cytoplasmic EGFL6 expressions fitted as indicator variables. All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS V.15.0 statistical software. All statistical tests were two-sided, and p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cytoplasmic EGFL6 is expressed in the majority of lung adenocarcinoma specimens

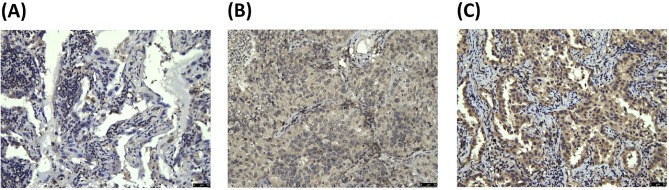

We verified the role of EGFL6 in the clinical outcome of lung adenocarcinoma by recruiting 150 patients. EGFL6 expression was detected with IHC staining, as shown in figure 1 (figure 1A–C). Of the 150 patients, only 6 (4%) showed no detectable cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression. Table 1 shows the relationships of cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression with clinicopathological characteristics. The mean patient age was 62.1±11.6 years (mean±SD). The cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression was not significantly associated with the clinicopathological characteristics of gender, grade, age or TNM stage.

Figure 1.

Representative immunostaining of EGFL6 in tissue arrays of lung adenocarcinoma specimens. EGFL6 expression levels were (A) 0, (B) 1+ and (C) 2+. EGFL6, epidermal growth factor-like domain 6.

Table 1.

Relationships of EGFL6 expression with clinical parameters in 150 patients with lung adenocarcinoma

| Cytoplasmic staining of EGFL6 | Total | P values | ||

| Low (0, 1+) | High (2+) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 24 (34.3) | 46 (65.7) | 70 | 0.817 |

| Male | 26 (32.5) | 54 (67.5) | 80 | |

| Grade | ||||

| Well | 8 (36.4) | 14 (63.6) | 22 | 0.744 |

| Moderate, poor | 42 (32.8) | 86 (67.2) | 128 | |

| Age | ||||

| ≤63 | 27 (35.5) | 49 (64.5) | 76 | 0.564 |

| >63 | 23 (31.1) | 51 (68.9) | 74 | |

| T status | ||||

| T1 | 19 (35.2) | 35 (64.8) | 54 | 0.718 |

| T2, T3, T4 | 31 (32.3) | 65 (67.7) | 96 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | 26 (29.9) | 61 (70.1) | 87 | 0.292 |

| Yes | 24 (38.1) | 39 (61.9) | 63 | |

| Stage | ||||

| I | 19 (30.6) | 43 (69.4) | 62 | 0.558 |

| II, III, IV | 31 (35.2) | 57 (64.8) | 88 | |

EGFL6, epidermal growth factor-like domain 6.

The prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinoma

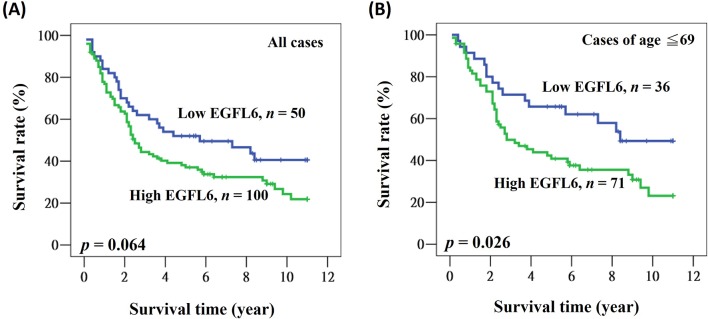

We further evaluated the prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Overall survival data were collected, and no data were missing from any of the 150 patients. The mean and median follow-up times after surgery were 5.2 and 3.2 years (range 0.1–11.0 years), respectively. The 5-year survival rate was 42.1%. During the survey, 99 (66.0%) patients died. In the univariate analysis, patients with advanced stage disease, aged >63 years old and male had significantly poorer clinical outcomes (table 2). These factors were still significantly associated with poor prognosis in the multivariate analysis (HR=2.241, 95% CI 1.443 to 3.481, p<0.001 for stage; HR=1.997, 95% CI 1.303 to 3.062, p=0.002 for age; HR=1.802, 95% CI 1.180 to 2.753, p=0.006 for gender; table 2). A prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 in lung adenocarcinoma was suggested by the finding that patients with high cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression had lower 5-year survival rates and shorter medium survival when compared with patients with low cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression (52.0% vs 37.0% for 5-year survival; 5.7 years vs 2.5 years for medium survival; figure 2A). The univariate and multivariate analyses revealed a borderline statistical significance for cytoplasmic EGFL6 (HR=1.519, 95% CI 0.980 to 2.355, p=0.061 for univariate analysis; HR=1.515, 95% CI 0.975 to 2.354, p=0.064 for multivariate analysis; table 2).

Table 2.

Influence of various parameters on overall survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P values | HR | 95% CI | P values |

| Expression of EGFL6 | ||||||

| Low | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| High | 1.519 | 0.980 to 2.355 | 0.061 | 1.515 | 0.975 to 2.354 | 0.064 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| Male | 2.184 | 1.450 to 3.290 | <0.001 | 1.802 | 1.180 to 2.753 | 0.006 |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤63 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| >63 | 1.808 | 1.214 to 2.691 | 0.004 | 1.997 | 1.303 to 3.062 | 0.002 |

| Stage | ||||||

| I | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

| II, III, IV | 1.871 | 1.232 to 2.840 | 0.003 | 2.241 | 1.443 to 3.481 | <0.001 |

EGFL6, epidermal growth factor-like domain 6.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier actuarial analysis of EGFL6 expression with respect to overall survival of (A) all patients and (B) patients younger than 69 years of age. EGFL6, epidermal growth factor-like domain 6.

Significant prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression in young patients with lung adenocarcinoma

We examined the potential prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 in patients with lung adenocarcinoma by analysing their clinical outcomes according to clinicopathological characteristics. We identified a significant association of cytoplasmic EGFL6 in patients with younger age. As shown in figure 2B, patients younger than 69 years of age who had high cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression also had a lower 5-year survival rate and shorter median survival time when compared with patients with low cytoplasmic EGFL6 expression (65.7% vs 40.9% for 5-year survival; 8.4 years vs 2.8 years for median survival; figure 2B). We confirmed this finding using different age cut-off points: the use of the median age as a cut-off point resulted in a significantly poorer prognosis for patients with high EGFL6 (HR: 2.118, 95% CI 1.082 to 4.145, p=0.029; table 3). The HR was also increased in patients of younger age (HR: 2.894, 95% CI 1.245 to 6.726, p=0.014 for age ≤59; HR: 2.104, 95% CI 1.184 to 3.739, p=0.011 for age ≤69; table 3).

Table 3.

Influence of EGFL6 on overall survival in patients with lung adenocarcinoma according to age

| Multivariate | ||||

| Subgroup | Case (n) | HR of EGFL6 expression* | 95% CI | P values |

| According to medium age | ||||

| ≤63 | 76 | 2.118 | 1.082 to 4.145 | 0.029 |

| >63 | 74 | 1.184 | 0.661 to 2.122 | 0.570 |

| According to grouped age | ||||

| ≤59 | 61 | 2.894 | 1.245 to 6.726 | 0.014 |

| ≤69 | 106 | 2.104 | 1.184 to 3.739 | 0.011 |

| All | 150 | 1.515 | 0.975 to 2.354 | 0.064 |

*Expression of EGFL6: high vs low.

EGFL6, epidermal growth factor-like domain 6.

Discussion

In this study, we identified a prognostic role of cytoplasmic EGFL6 in lung adenocarcinoma, especially in patients of younger age. This is the first study to provide clinical evidence of EGFL6 expression in lung adenocarcinoma. No association was noted between EGFL6 expression and clinical parameters, but the significantly poor clinical outcome of patients with high EGFL6 expression supports the findings of previous reports regarding EGFL6 expression in other types of cancer.10 12 17

The role of EGFLF6 in cell division and tissue development was first identified in a non-tumour model.12–14 18 In a bone remodelling model, EGFL6 induced angiogenesis via a paracrine mechanism that promoted angiogenesis and migration of endothelial cells.12 Inhibition of phosphorylated ERK in this model decreased the ability of the cells to migrate.12 In a zebrafish model, EGFL6 promoted angiogenesis via a mechanism that depended on the RGD domain (Arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid domain) and on the activation of the Akt and Erk pathways.18 Loss of EGFL6 decreased the number of endothelial cells and vessels, suggesting that EGFL6 acts as a positive regulator of functional vessel formation.18

Increasing evidence supports the role of EGFL6 in regulating tumour malignancy and shows the potential of EGFL6 to serve as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target. In ovarian cancer, EGFL6 expression is associated with poor clinical outcome, which is further explained by its role in promoting cancer cell proliferation and asymmetric division.11 A model using aldehyde dehydrogenase+ (ALDH+) ovarian cancer cells showed that EGFL6 signalling involves integrin, SHP2 and ERK.11 The results of a molecular analysis of ovarian tumour vascular cells obtained with IHC-guided laser-capture microdissection and genome-wide transcriptional profiling also supported this result.17 Patients with oral cancer also show high plasma EGFL6 levels and high tumour EGFL6 mRNA expression.10 The apparent association between plasma EGFL6 and the clinicopathological features in patients with oral cancer suggests a potential application of EGFL6 in monitoring tumour behaviour.10

There are some limitations to this study. The use of tissue arrays cannot represent the whole tumour and no duplicated array was investigated in this study. The limited sample size weakens the impact of our finding. Thus, more complete studies with a large sample size are still needed in the future. Also, only one clone of antibody was used, and the results should be further validated with different antibody clones.

In conclusion, our study findings demonstrated that cytoplasmic EGFL6 is specifically expressed in lung adenocarcinoma, and this increased expression is associated with poor clinical outcome. These results support the suggestion that cytoplasmic EGFL6 can serve as a valuable marker for the prediction of tumour malignancy and that it has therapeutic potential, although our findings need to be confirmed by further studies. Additional molecular studies are also needed to provide a more indepth picture regarding the function of cytoplasmic EGFL6 in lung adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

T-CL and K-TY contributed equally.

Contributors: Conception and design: T-CL, K-TY; acquisition of data: C-CC, H-TH, C-MY, C-HL, Y-LC; analysis and interpretation of data: C-CC, H-TH; drafting of the manuscript: C-CC, W-WS; critical revision of the manuscript: T-CL, K-TY; statistical analysis: W-WS; supervision: T-CL, K-TY.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and the Ethics Committee of the Changhua Christian Hospital, Changhua, Taiwan (CCH IRB 170511).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data.

References

- 1. Sung WW, Wang YC, Lin PL, et al. . IL-10 promotes tumor aggressiveness via upregulation of CIP2A transcription in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:4092–103. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang SC, Lai WW, Lin CC, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of implementing computed tomography screening for lung cancer in Taiwan. Lung Cancer 2017;108:183–91. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:7–30. 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:540–50. 10.1038/nrc1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sung WW, Wang YC, Cheng YW, et al. . A polymorphic -844T/C in fasl promoter predicts survival and relapse in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5991–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davis CG. The many faces of epidermal growth factor repeats. New Biol 1990;2:410–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yeung G, Mulero JJ, Berntsen RP, et al. . Cloning of a novel epidermal growth factor repeat containing gene EGFL6: expressed in tumor and fetal tissues. Genomics 1999;62:304–7. 10.1006/geno.1999.6011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh AB, Harris RC. Autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine signaling by EGFR ligands. Cell Signal 2005;17:1183–93. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chuang CY, Chen MK, Hsieh MJ, et al. . High level of plasma EGFL6 is associated with clinicopathological characteristics in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Med Sci 2017;14:419–24. 10.7150/ijms.18555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bai S, Ingram P, Chen YC, et al. . EGFL6 regulates the asymmetric division, maintenance, and metastasis of ALDH+ ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res 2016;76:6396–409. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chim SM, Qin A, Tickner J, et al. . EGFL6 promotes endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis through the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. J Biol Chem 2011;286:22035–46. 10.1074/jbc.M110.187633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chim SM, Tickner J, Chow ST, et al. . Angiogenic factors in bone local environment. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2013;24:297–310. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang X, Wang X, Yuan W, et al. . Egfl6 is involved in zebrafish notochord development. Fish Physiol Biochem 2015;41:961–9. 10.1007/s10695-015-0061-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hwang JC, Sung WW, Tu HP, et al. . The overexpression of FEN1 and RAD54B may act as independent prognostic factors of lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139435 10.1371/journal.pone.0139435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sung WW, Lin YM, Wu PR, et al. . High nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio of Cdk1 expression predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. BMC Cancer 2014;14:951 10.1186/1471-2407-14-951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buckanovich RJ, Sasaroli D, O’Brien-Jenkins A, et al. . Tumor vascular proteins as biomarkers in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:852–61. 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang X, Yuan W, Wang X, et al. . The somite-secreted factor maeg promotes zebrafish embryonic angiogenesis. Oncotarget 2016;7:77749–63. 10.18632/oncotarget.12793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-021385supp001.jpg (717.1KB, jpg)